The University of Vermont’s Environmental Publication Spring 2024

The University of Vermont’s Environmental Publication Spring 2024

Winter in Vermont: Changes in Climate and Culture

By Valentin Kostelnik | page 4

Watchful, Hopeful

By James Marino | page 8

The Restorative Art of Being Natural

By Devan Kajah | page 9

Native Fish of Vermont

By Avery Redfern | page 28

Tides of Change: Investigating Climate Change and Coastal Vulnerability on Human and Wildlife Communities in the Northeastern U.S.

By Casey Benderoth | page 29

Managing Editor

Anna Eldridge

Editors

Aiden Armstrong

Alma Smith

Anna Hoppe

Avery Redfern

Ben Mowery

Cole Barry

Greta Albrecht

Loden Croll

Myla van Lynde

Sarah O’Leary

Editor-in-Chief

Teresa Helms

Creative Director

Ella Weatherington

Social Media Manager

Emma Polhemus

Planning and Outreach

Adelyne Hayward

Treasurer Anna Hoppe

Find us @uvmheadwaters on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, and Twitter and online at headwatersmagazine.com

Copyright © 2024 Headwaters Magazine This magazine was printed on the traditional land of the Abenaki People

Managing Designer

Maya Kagan

Artists and Designers

Alexandra Sicat

Avery Redfern

Cali Wisnosky

Cameil Nelson

Casey Benderoth

Ella Weatherington

Emma Polhemus

Es Sweeney

James Marino

Lauren Manning

Liza Teleguine

Loden Croll

Luke Hoyes

Maya Kagan

Mia Weyant

Phoebe Swartz

Rachel Lamb

Sadie Holmes

Wylie Roberts

Welcome to the Spring 2024 edition of Headwaters Magazine! We finalized our 16th issue in the days after witnessing a total solar eclipse bring darkness and hoards of travelers to Burlington; an experience that brought us a shared and surprising sense of awe, of smallness and luckiness in witnessing this once-in-a-lifetime natural phenomenon. But more than that, we have been inspired by the feeling of connection–to our neighbors and the world around us–lingering in our community. This week, along with many of the pieces in our magazine this semester, has been a reminder of the essential joy and support found in cultivating our relationships with each other and with the land.

We hope that as you read about Vermont’s shifting climate, adapting coastal communities to new weather norms, and restorative landscape management, you are struck by the pertinence of this edition’s theme: embracing change. Now more than ever, strengthening relationships will be essential as we navigate “through the narrows”, or the uncertainty of the future. This will require adaptation, relinquishing long-held systems that maintain the status quo, and trusting that good and beautiful things will come as others are let go.

These ideas are also explored in the images and text on this issue’s cover, inspired by the insights we have gleaned from studying our watershed and acutely engaging with our place in it; lessons from the headwaters, so to speak. Leaning into change can be jarring, uncomfortable, even painful, akin to tearing off your clothes to plunge into a lake fresh with snow melt. Though it may seem trivial, we hope that you, like our team, find ways to practice leaving the path of least resistance and welcoming change into your life. We urge you to stand up for that which must change, wherever injustice is present.

This edition of Headwaters is longer than normal, filled with 50-plus wonderful pages of artwork, poetry, creative writing, games, and more! Enjoy the bounty of original student work in tandem with the bounty of spring–the return of the robins, purple crocuses, new beginnings, and everything in between.

With love,

Teresa Helms University of Vermont ‘24 Editor-in-Chief

Teresa Helms University of Vermont ‘24 Editor-in-Chief

Anna Eldridge University of Vermont ‘25 Managing-Editor

Anna Eldridge University of Vermont ‘25 Managing-Editor

When it snows these days, it seems as though more and more people are saying “At last! It’s good to know it still snows in Vermont.” I know the feeling, like winter is not what it used to be. Looking with trepidation at the next decades, wondering if Lake Champlain will ever freeze over again, if Vermont skiing will exist in 20 years, and listening to wistful Vermonters remembering when we had “real winters.”

In the 1800s, there were only three years where Lake Champlain didn’t completely freeze over. As of 2024, it has been ice-free for 16 of the past 24 winters. Average annual snowfall has decreased by 10 inches since 1960, and Vermont winters have warmed by 3.3˚F since 1900, well above the global average of about 1.9˚F. These statistics, as stunning as they are, can be hard to visualize, but there are countless localized impacts of climate change. Lilacs, a traditional herald of springtime, are now blooming several days earlier every decade. Gavin Sicard, a UVM senior from Colchester, can tell that “definitely we’ve had less snow in recent years…I remember as a kid you’d have decent snow coverage throughout the whole winter, which I feel is not how it is in Chittenden County now.” These changes are keenly felt, and are only predicted to intensify in our lifetimes.

Winter in Vermont is a special thing in the United States: like the winds in Chicago, it’s a defining characteristic. When I was accepted to UVM, the first thing my friends in California told me was “I hope you like the cold!” Winter and Vermont are closely intertwined in culture, image, economy, and even politics. Outdoor recreation brings in $1.9 billion annually to Vermont and makes up a greater percentage of state GDP than any other state except Hawai’i. Of that, winter recreation represents the largest portion, and the success of winter tourism is thanks in large part to the image of Vermont as a winter wonderland. One commentator even stated that snow has become “white gold…a commodity that can be enjoyed or sold to advantage”.

But as any Vermonter would tell you, winter is also a vital and unavoidable component of living here. Snowball fights, ski days with the family, cozy holidays, skat-

ing, sledding, hot chocolate on the slopes, walking out of sub-freezing temperatures into a warm home, shoveling the driveway; how important are these things to your life experience? This component is harder to put your finger on, and impossible to define by a dollar value or percentage of GDP. Climate change threatens to drastically change all of these experiences. What effect will that have on the psyche of Vermonters, and New Englanders as a whole?

First, we must ask how winter is experienced in Vermont currently, and how it molds the identity of people living here. Winter is a cold and dark time, but also a time for reflection, and has always been brightened by sparks of joy. For Gavin Sicard, snow has always been the best part of the winter. Gavin says, “I remember in highschool thinking, ‘the snow day is gonna save my mental sanity.’”

He recalls skiing every Friday night at Bolton with the neighborhood kids, or tying an ice-fishing sled to his dad’s ATV and being dragged wildly around his backyard. Apparently, snow is good to eat, too, as Gavin recalls filling bowls with snow as a snack. “You can’t call snow just cold water! Snow is delicious.” To an outsider like me, this seems quintessentially, perfectly, Vermont.

At least as early as the 1800s, Vermonters have been doing things much like Gavin and his family. Early 20th-century author Edward Crane affectionately describes the “three S’s - skating, sledding, and sleigh-riding,” and goes on to describe how the winter shapes the Vermont psyche, saying “When snow falls on Vermont, I like to think not only that it is remolding the landscape, but that it is also reshaping our character, to the extent at least that it renews our spunk.”

Part of this “reshaping” came from the isolation that winter brought, as heavy snow made travel nearly impossible. For your average farmer in 1900, the journey into Burlington in January was perilous, so you’d just stay near your farm. At the same time, winter’s slower pace made it a time for socializing and fun. Vermont author Blake Harrison writes about how “neighbors often came together on winter evenings for informal gath-

erings…guests would move furniture out of the host’s kitchen..to make way for music, dancing and socializing…Residents recall these parties happening just about every Saturday night.”

These evocations of joy, and Crane’s “reshaping our character,” seem somewhat idyllic, like something from a postcard, and indeed they seemed that way back then. A promoter in 1909 wrote, “To the weary people of crowded cities that would like…a genuine Vermont winter, a weekend visit to some comfortable village in the state will afford rare delights that maybe have only been read of in story books.”

A hundred years ago, just as today, winter was a formative piece of both the life experience of local Vermonters and how the rest of the nation thought of Vemont. Gradually, the image of Vermont’s winter became integral to the success of tourism here. The “story book” appeal was only heightened by Bing Crosby’s 1952 classic White Christmas, set in a cozy Vermont inn. One reporter argues that “Winter tourism’s success depended on the visitor’s ability to understand and embrace the very essence of winter in Vermont”.

While the image of winter was being constructed, skiing took over as the state’s most important recreational sector. For many people in Vermont, especially at UVM, skiing is the highlight of winter, but this is a relatively new phenomenon.

By some accounts, the first ski tow in the US was built in Woodstock in 1934, when the Royce family attached a rope to a Model-T engine and set the contraption up on a neighbor’s hill. Before the Royce tow, skinning and cross-country were the only forms of skiing in the state, and you had to hike hours through the forest for a single run. This slower, more traditional sport was rapidly transformed in postwar America. The first major breakthrough came in 1940, when the state’s first ski lift was built on Mount Mansfield, and automated lifts soon became the norm. They revolutionized skiing by opening the higher slopes of the Green Mountains, where the runs were steeper, the snow was deeper, and the season longer.

After that, skiing suddenly became easier and faster than ever. Whereas a backcountry skier could maybe get 3 runs in a day, people on the new lifts could get in a dozen or more runs. Skiing became a fast-paced sport. By 1949 there were 400,000 skiers in Vermont, and just ten years later the number exploded to 1,000,000. Vermont fixtures, such as Bromley, Sugarbush, Bolton, and Smuggler’s Notch, are all fairly young and were founded in the rapid growth of the 1950s and 1960s.

The towns close to the new resorts, especially in

the Mad River Valley, had mixed feelings about winter’s newest industry. While many residents embraced the new jobs and faster runs, the fast-paced, corporate, mechanized sport also had a negative impact on Vermonter’s image of themselves. It didn’t fit into the traditional winters of slow days, hard work, and community events. One resident observed, “You’ve gone from an independent, self-reliant community to a group of people who provide services to the out-of-state wealthy.”

Nonetheless, from its humble beginnings as a Model-T tow on the hills of Woodstock, the ski industry has become a linchpin of Vermont’s economy. It’s estimated that skiing attracts roughly $1.6 billion annually to Vermont, and at the same time has become entrenched in Vermont’s culture and winter lifestyle. Vermonters nostalgically recall past family ski days, and for some college students, skiing is all that gets them through a week. Skiing is also a defining aspect of UVM, such that Evan Coleman, a first-year at UVM, says “the Ski and Snowboard Club is so huge here and pretty much everyone I know at the school does skiing in some way or another.” And today, this vast industry is directly in the path of climate change.

Winter is the fastest warming season in Vermont, at 3.3˚F since 1900. These impacts are often easily seen or perceived during the winter months, which can be when climate change feels the most apparent. For example, since the 1970s, Vermont lakes and ponds have been going ice-free one to three days earlier every decade. This statistic is keenly felt where skating on the pond in the backyard is a common family tradition, and where many towns place bets on what day the ice will break on a local pond. In addition, average annual snowfall has decreased by 10 inches since 1960, and this is the shift that makes climate change the most painfully obvious. When asked about climate change, Evan Coleman said he thinks about it “every day when thinking about the lack of snow here … here it drives the recreation.”

Christmas, one of the most iconic winter scenes, is supposed to have snow. But with less snowfall and more rain, there’s a good chance of having mud on the ground rather than a soft white blanket. Gavin describes, “It’s very disappointing when there’s no snow on the ground … it doesn’t really feel like it’s a Christmas Day when it’s dirt.”

What impacts will this have on Vermont’s identity, culture, and psyche? For one thing, climate anxiety and related mental health impacts will intensify. As Yale researcher Sarah Lowe defines it, “Climate anxiety is fundamentally distress about climate change and its impacts on the landscape and human existence.”

Gavin describes a different feeling, though. Not climate anxiety, but rather “... climate sadness that I experience when it’s wintertime and this part of the culture is dying. This experience that something that was really important is starting to diminish.”

This sensation is called solastalgia, or the “gradual removal of solace from the present state of one’s home environment.” It’s the sense that the world we grew up in, with all its joyous sledding, white Christmasses, and community skiing, is fading, and the solace and familiarity of that environment are fading with it. The concerns about an earlier ice-out manifest themselves in all the people who grew up skating on a nearby pond but feel like they don’t do it as much anymore. The decreased snowfall is felt by the lack of snow days, the worse skiing conditions, and a muddy Christmas.

One of the hardest trials of the winter is seasonal depression, which is more related to the shorter days and lack of sunlight than the cold or the snow. Everyone can relate when Gavin says “It’s terrible when it’s 4 pm, you’re still at work, and it’s black outside. I don’t know why the sun decided to do that to us!” The days won’t get any longer with climate change, but the more positive aspects of winter such as skiing, sledding, and skating, might be lessened. In one view, the best parts of winter will be lost, while the worst parts will stick around. Gavin describes:

I think it’s gonna be dark, muddy, the leaves still won’t be here, and all in all it’ll be a more depressing

experience…If you see Vermont when there’s snow on the ground it’s all bright because it’s so reflective, but when the snow is gone only the darkness remains.

Solastalgia is all too easy to sink into these days. Climate anxiety is distinct from the other mental impacts of climate change, such as the stress caused by drought and famine, in that it is caused more by the specter of climate change than its physical impacts. While young people in high-income countries are sheltered from those physical stressors, research suggests they are the most vulnerable population to climate anxiety.

But it’s important to remember that winters are not everything, and they will not fade completely. Gavin’s favorite season is spring, and he says: “When I think of Vermont, I don’t think it’s synonymous with winter. I think the more classic Vermont season is autumn, with the leaves changing ... And a big part of my thinking of Vermont is Lake Champlain, which is more summer-coded.” Economically, outdoor recreation is based on more than just skiing, snow-making technology is developing rapidly, and Vermont is not likely to lose its appeal to tourists in the coming decades. And though average temperatures and snowfall will decrease there is large variability between years, so some individual winters will still have heavy snow and freezing temperatures.

Additionally, it is important to remember that drastic changes to our surroundings are hardly unique. Consider skiing before the 40s and 50s: it was not a significant part of people’s winter experience. Students at UVM couldn’t

Art by Sadie Holmesski mornings before classes, and in fact, some people thought large ski resorts ran against traditional winter activities. A few decades later, in 1972, a commentator wrote about the towns of Mad River: “The developments bring more jobs for slinging hash and plowing snow. But the identity of our towns is changing significantly in the process and it’s not changing for the better.”

This concept of change is key. The human experience of Vermont winter probably changed more in the 20th century than it will in the 21st century. In the mid-19th century, winter was a time of work the same as the other seasons.

Milk cows still needed to be milked daily, teams went out to cut blocks of ice for summer refrigeration, while loggers used the frozen ground to cut timber for sale. As Blake Harrison writes, “Many of us today could not even imagine waking up in a dark, poorly heated home on a sub-zero day to milk a herd of twenty cows before breakfast.”

Much has changed since then. The arrival of landlines, TVs, and snowplows lessened the sense of isolation; lifts transformed skiing into a fast-paced sport, while industrial agriculture and transportation now allow me to eat lettuce and tomatoes in February. One way of life ending does not mean the

world is ending. While climate change is unique, rapid changes to human experience are not. It’s crucial to keep the changes facing our generation in the context of the past, focus on the beautiful things that remain to us, and fight to keep the change as minimal as possible. H

a t c h f u l H o p e f u l

By James Marino

Digital Illustration

By James Marino

Digital Illustration

My piece is about the biodiversity crisis and shows the eyes of six endangered species. I wanted to illustrate the relationship between humans and other animals by making “contact” between the two—eye contact. Humans are unique because we are the only species that gets to choose what role we play in this world. I hope we will choose to play a role that allows nature on our planet to thrive. H

To ebb and flow and smooth the colorful, shifting stones that lay just beneath the dappled surface of the water, breathing in and out every shift in the environment. To carefully carve away at the loamy banks just enough to create a welcoming place for your kin. To create a place for Belted Kingfisher to form their intimate burrow and a space they deem safe enough to rear their young. A slithering body, twisting and writhing through the lush mountains and valleys speaking only loud enough for those who want to listen, protecting every whisper heard and every story that has danced through the reeds. Currents carry instinctively across the landscape, offering the ritualistic grounds for thousands of minnows, caddisflies, and mycelium to call their home.

But what happens when landscapes become restricted? When ungrateful machines gnaw at the forests, and dark calloused fingers dredge the fishes from the waters in a rough nylon embrace–what happens then? Damaged, degraded, and destroyed patches of land now make up the mosaic of most of our world and with little to even show for it. Hopelessness, anger, fear, eco-anxiety, solastalgia, and other emerging emotions of the Anthropocene that have yet to be labeled may deepen that sinking feeling in your gut when thinking about the current and future state of our climate. I try to be as optimistic as possible. I mend the ripped knee in my pants and compost my orange peels, yet it never quite feels tangible enough.

This past summer I was introduced to the concept of ecological restoration. Ecological restoration is the act of bringing a damaged, degraded, or destroyed ecosystem back to a functioning state. This fall I also joined the Fellowship for Restoration Ecologies and Cultures, which focuses on designing and implementing landscape restoration projects in the Carse Natural Area in Hinesburg, Vermont. I have learned an incredible amount about the environments surrounding me and found my place within them through both experiences. I have learned to engage in reciprocity with the land in a way more meaningful and tangible to me, and discovered how to practice ecological and community restoration.

Additionally, I have learned so much from the act of restoration itself. How to guide my life and principles based on the restoration processes; how to navigate relationships within my life and model them after natural processes. In other words, how to be natural. Through building beaver dam analogs on the Upper Oregon Creek

in Montana to slow the movement of sediments, learning about process-based restoration, and removing buckthorn and honeysuckle in Carse to make way for native stem plantings, I have learned what being “natural” feels like.

The main goal of ecological restoration is to set the degraded landscape on a trajectory toward healthy ecosystem composition and structure. Because of this, restoration practitioners often have a difficult time defining what the end of the project will look like. Of course, you can define the end of the project by time, by what species reappear, or by measuring water quality, if that was the goal. But the great thing about restoration is that it recognizes ecosystems as dynamic and changing systems–exactly how we are, too. Our lives are dynamic, changing, and unpredictable. Just as a river meanders and shifts, our lives wander through different ways of being and knowing. Just as forests grow and change and will never look the same each year, our years may not see the same places or the same faces.

Here the aforementioned “process-based restoration” makes a return. Low-tech process-based restoration includes design principles mainly used in riverscape restoration. These principles are outlined in the Utah State University Restoration Consortium’s “Riverscape Design Principles’’ manual from 2019 which provides restoration practitioners with low-tech structures to implement in the restoration of impaired waterways. Lowtech structures are structures that are made from simple, cheap materials that often come from the surrounding landscape to add to waterways, similar to how beavers build their dams. In this case, “process-based” is referring to the desired end goal and leading actions of a restoration project that aims to restore the natural processes and systems of the landscape.

The restoration manual outlines several key riverscape principles including, “streams need space,” and, “inefficient conveyance of water is healthy.” Dynamic streams are healthy streams! Streams and rivers regularly shift and move along the landscape. I allow myself to do the same and welcome change within myself and in my surroundings. Knowing that I am just like a stream, changing and wandering, sometimes with an end goal, sometimes not, helps me remind myself that everything will work out. Similarly, the slow and inefficient movement of water in streams and rivers allows for groundwater and aquifers to replenish, reduces erosion,

and reduces flood potential– hence the stream’s need for freeflow movement. In the past, I have always rushed through things, but just as streams benefit from the slow and gradual meandering of water, we also benefit from slowing down and being present and intentional.

The low-tech riverscape design manual similarly illustrates several key restoration principles: 1) it’s okay to be messy, 2) there’s strength in numbers, and 3) let the system do the work. These three principles, integral components to consider for river restorations, can also be directly applied to our own lives.

The first principle expresses that the more woody debris, rocks, and plants that you add to a river system, the healthier it becomes. More nutrients are added to the system and habitats are created. A messy river also moves slowly, which as mentioned previously allows the water ample time to seep into the soils. I often find myself becoming overly tied to a good grade or making sure I hit the next milestone in my life that arbitrarily was assigned to me. Seeing how rivers benefit from slow movements that wind with no set path reminds me to do the same. It’s ok if I am not on the same path as those around me–no two rivers follow the same course. Being as intentional and slow as these riverscapes has enabled me to be more observant, attentive, present, and appreciative in all the moments of my life instead of constantly rushing to finish the next task.

Structures placed in a river restoration project illustrate the second principle–that there is strength in num bers. Whether it’s visible or not, every branch, stone, and piece of sod all work together for the desired outcome. I have found that it is far too easy to push myself to ac complish things on my own because of the pride that comes from that. And there’s absolutely no shame in feeling prideful and successful over something that you worked hard to accomplish, but two truths can be held at the same time and community is the glue that holds our individual lives together. A stone on its own can be gor geously marbled, but amongst others, a stunning mosaic of color can appear.

The third and final prin ciple states to allow the system to do the work. This means setting it up for success so that it can grow into some thing even healthier than it was

before. Ecological restoration is an art. As an artist, it can be difficult to declare the work finished and walk away. However, you cannot expect something that is coddled to succeed. This also means doing the best we can and knowing that it will work out. I’ve come to learn that there is never any use in stressing over something that is out of my hands and that all I can do is do my best, stay positive, and know that everything will work out just fine.

There is a lot to learn from restoration. We can learn how to slow down and be intentional in our actions, and understand that just as rivers are dynamic, we are too. Recognizing some of the principles of restoration has allowed me to see that we are inherently natural. Natural in the sense that we too have intricate lives that rely on this vast amalgamation of communities, experiences, pieces, and players that shape every one of us in our own sweet time. The way we guide our relationships, our families, and our daily patterns follow those of natural systems like rivers. Our lives will ebb and flow over the years, seeing different people and places and changing into something better with each new experience that crosses it. We often see ourselves as something other than or above the natural world. In reality, we are deeply part of it and always will be. Throughout history, we have forcefully removed ourselves from nature and removed the more-than-human world from us, harming both in the process. Once we recognize our ways as meandering, boundless, and parallel to those of natural systems, we can begin liv

The fond recollection of bare feet in the wet warm grass. Dirt-dusted hands and legs; scabby knees sporting striped capris; and a gummy, gap-toothed smile brighter and bigger than the sun. I was eight years old, wearing a stellar purple flower sundress, and my parents and I had gone down to Narragansett. The forty-minute drive felt like the excursion of a lifetime to me as we crossed gargantuan bridges over sheets of sparkling sea water. I loved how the floating boats looked like flocks of seagulls from that high up. At Point Judith, I stood in the clover-studded grass and imagined myself flying over the Atlantic surrounded by dozens of colorful kites. I visualized being the captain of a magnificent ship, arriving upon this peninsula in the depths of the night, guided only by the stars and the beams from the lighthouse.

It didn’t matter where we were: the park, the woods, the yard, the pond, a vacant parking lot with dandelions growing through the cracks. We could turn any outdoor terrain into an exploration of the unknown, a treacherous journey, or a whimsy-filled utopia. It was simple, natural, and exciting. As children, our wonder belonged to us, so tangible that we could conjure it, bottle it, and carry it with us all day. Nature provides children with endless tools of the imagination to construct their unique ideas of our world. Being outdoors facilitates unimaginable growth of knowledge and creativ-

ity that allows for a better understanding of what makes up our planet. The pure intentions and compassion of a child’s love for nature is something that, if carried into adulthood, could result in a major shift in worldwide affections for our environment.

Like many of my peers, my happiest childhood memories took place outdoors: riding my bike up and down my street, collecting pine cones, acorns, and pebbles in my basket to take back to my yard and build a fairy house; swimming in the ocean, pretending that I was a fish and could talk to all of the marine animals; fishing and catching frogs and bugs in nets in a murky pond, hoping to find as many different creatures as I could. As a kid, my imagination bloomed the moment I went outdoors. It is apparent today that children experience nature differently than I once did. With phones, tablets, and other devices being much more accessible to young kids, we have seen a decrease in interest in playing in nature or going outdoors at all. Research from the journal Frontiers and Public Health has shown that from 2019-2021, the proportion of kids who played outdoors for an hour or more a week decreased by 15%. Of course, this could be attributed to the uncertainties of the pandemic and the increase in screen time for school, but the harmful effects of this decrease in outdoor activity are extremely apparent. Children who

and education, and the natural world sur rounds my percep tion of myself, my community, and the world. We can all re visit the joy and whimsy of our child hood adven tures at any time if we just allow ourselves to go play out

Art by Alexandra Sicat

1. Intellectual Exploration

Intellectuals, politicians, and others begin to explore fascist ideas. Fascist movements often emerge in response to societal unrest, economic crises, or perceived threats to national identity.

The first time I saw an animal die, it was a deer. A sharp thud as it hit my mother’s car, and it was gone.

I stared, startled, at the broken leg in the rearview mirror. I was shaking, unable to move. A body, red with flesh and moving so slowly the liquid inside of me begged to come up. The car door clicked open and my mother threw her hands in the air. Fingers shocked with inconvenience, shaken out in motion as if to free the blood stained on them.

The body lay silent just off the road. I looked away, my breath as heavy as the car beneath me.

The tires spun off and I didn’t look back. Better the deer than the car, than you, than me. She tried to justify it in her own way, already ahead of her thoughts.

“I feel awful,” she threw out, stroking my hair and grinding her teeth. It weighed heavy but she’d already begun rationalizing it, driving off after calling authorities.

People like to believe that they are logical, consistent, and good at making decisions. When those beliefs are threatened by pressing sources, we do everything we can to prevent our thoughts from spiraling.

Cognitive dissonance theory, developed by sociologist Leon Festinger, suggests that people become psychologically discomforted by an opposing thought that is not consistent with their current belief. To quell this discomfort, we push the thoughts away, change the belief, or find something that makes us feel logical again.

On average, there are between 10,000 injuries and 175 to 200 fatalities every year caused by deer accidents. But those “injuries and fatalities” are reserved for humans. Over 1 million deer are hit by vehicles each year.

The message is clear, we’re alive! My mom’s mouth sunk into a Wendy’s burger that we stopped to grab just

down the road. I sucked down my vanilla milkshake, eyes glazed. A body mourned is reserved for only us humans. Celebrate.

In 1998, Robert O. Paxton defined five stages that a state takes while descending into fascism: intellectual exploration, rooting, arrival to power, exercise of power, and a descent into radicalization or entropy.

In the beginning, there is a sense of promise; a restored nation, united by people bleeding for a common cause.

I have found the descent into cognitive dissonance mirrors these same steps.

The knowing, the rejecting, the anything to make us feel as if we are just. We give into what people feed us every day; brush your teeth two times a day and if you don’t you’ll get cavities, work a job, get a car, but don’t waste gas or else you’ll be the one contributing to the biggest climate catastrophe of the human era.

And what do we do when faced with it? We continue to scroll and eat our burgers in ignorance, rejection, or both.

By this age, I am familiar with societal “shoulds” and “shouldn’ts.” I can play into the regime that wants me to feel guilty about not brushing my teeth, but it’s difficult when face to face with increasing temperatures, flooding or a dead deer on the side of the road.

How do I overcome the guilt of participating in systems that contribute to death and destruction? Is there any way to make myself feel better?

As fascist ideas gain traction, these movements aim to gain political power through democratic or revolutionary means. They may form political parties, engage in propaganda campaigns, or build paramilitary organizations to intimidate opponents and as sert control.

The case of climate change is something of a perplexity. For those residing in a resourced country, it often does not impact day-to-day livelihoods, though its effects are noticed. When presented with dire headlines we tend to turn our backs.

Let’s be honest, it is much more comfortable to sit on the couch than to take action. Four years of studying the environment and I still can’t bother to throw plastic into the bright blue bin.

It seems like the answer to this dissonance is found in our brains. Neurologists say that part of the reason humans are slow to act in regard to the future is that the human brain has spent nearly 200,000 years focused on

the present. “Find food. Make shelter. Survive.”

We have only just begun to contemplate time, and by extension the future, within the last few hundred years.

And it seems that making the future tangible is something that is only reserved for people who have the time to do it. Most of the working class around the world are plagued by what they will eat for dinner, when they will get their next food stamps, or when the next rent payment is due. Why should they care about which glacier will melt next?

Usually, the problem has rooted long before the dissonance arises. If lawmakers in the 1980s had taken warnings about pollution more seriously, I might not be facing the dissonance I feel around climate change today.

Fascism finds the people who are tired of blaming themselves, who want to learn how to feel better about the dissonance. People want something to believe in to get them to the next paycheck, and the government plays with us like puppets on strings. They know that if people only worry about survival, they can’t afford to care about climate change.

Where does that leave me? Spending the last few years learning about the future of our world, I am privileged to have the choice to consume or not consume.

I know the information, and I have the time, but I still waste too much water or buy petroleum products for my own short-term convenience. It’s comfortable. It’s addictive.

Then, Vermont towns flooded for the third time since July. The smog this summer from Canadian wildfires made it a hazard to recreate outside. Would it be better to live in ignorance? To tune out the dissonance, reject the rooting?

Sometimes, in shame late at night, I wish I could focus only on the next gas bill and not global catastrophe.

Once in power, fascists often use authoritarian tactics to consolidate their control over government institutions and suppress dissent.

We reject what makes us uncomfortable. We keep driving. The basics of evolutionary survival help us mask reality so we can enjoy our burger.

Psychologists have said people who feel uncomfortable with their moral actions tend to seek information that aligns with and supports current beliefs. This reduces the conflicting belief’s importance or changes their beliefs to reduce feelings of conflict.

There are probably other people recycling so why do

I need to?

Humans are the greatest species.

Animals are supposed to be eaten, it’s biological.

It’s a high, this dissonance. We are all addicted to pretending, to avoiding, to rejecting.

There is a story of a fisherman who refuses to accept climate change. The fisherman explains that he would accept the reality of climate change only if a 500-yearold scientist told him it was happening. By making this impossible claim, the fisherman has saved himself from moral action. I wish I were as lucky.

I take a shower and only hear the water rushing out onto the streets of Montpelier in the wake of a flood. The drug of denial is sometimes the only way I can go about my day.

With control over the state, fascists implement their agenda, which typically involves the centralization of power, the suppression of political opposition, and the promotion of nationalist and authoritarian policies.

Six years ago I watched the documentary Cowspiracy. My ecology teacher had recommended it, and I sat down on a Saturday to watch, pint of Ben and Jerry’s in hand. Images of deforestation, beaten cows, soil erosion, species extinction, and virtually every other environmental ill flicked by on my screen.

I continued to eat meat for a week after that. But I kept watching and reading more. The more this information screamed at me, the more my dissonance screamed back.

That summer, I took the step to become vegetarian. I began learning to cook with tofu, tried meatless chicken nuggets, and learned how a good salad could taste. For some time, the dissonance began to fade.

Although the looming threats of big agriculture and big oil were still ever-present, I was able to gain control over them. It had settled into a strong hate for the system other than myself. It was revolutionary.

In many ways, fascist regimes are revolutionary because they advocate the overthrow of the existing system of government and the persecution of political enemies. For example, the overthrow of oil and gas industries would bring about more rapid change to the climate change agenda. There are ways in which the existing systems of bureaucracy and government get in the way

of environmental goals if they were scrapped. Perhaps there is something to be said for revolution and the space for opportunity it creates.

I had overthrown the existing regime of complacency. I had taken the power back for myself by putting thoughts into action.

Yet, after the coup, after the revolution, the fascist regime takes on the guise it was intent on all along. When the regime gains power, most seek to push racism, xenophobia, and, most of all, obedience to authority.

We examine one limb, which, of course, can mislead us about the whole beast.

Going into freshman year of college, I was a hippie-loving vegetarian as good as they come. I vowed I was doing good for the planet, that I was somehow saving a cow from a horrible life and our atmosphere from its methane farts. I was zealous. Last fall, I tasted sausage again after four years without eating any meat. And it was good. Slowly, I began to eat my friends’ leftovers.

Now, I say I

won’t buy meat, but I’ll still eat it. The beast was

back.

Why, even when I tasted victory, did I accept defeat? I guess it tasted good, filled me up, and the jarring imagery of slaughtered cows no longer burned my vision after four years. Yet, it has to boil down to more than just what’s comfortable in the short term.

There’s also that smaller, anti-capitalist voice in my head telling me not to beat myself up about eating chicken once a month. Is there a way to take my power back?

5. Radicalization or Entropy

In this stage, the fascist regime may undergo radicalization as it seeks to further consolidate power and pursue its ideological goals. Alternatively, the regime may face internal divisions, resistance, or external pressures that lead to its decline and eventual collapse.

If it’s true that humans are hard-wired to be confronted with the dissonance of choice, how do we move forward? How do we cope

with catastrophe?

One way psychologists suggest to cope with dissonance is to challenge our current beliefs. Is it on me to absorb the guilt of climate change? Is it my fault for throwing out the plastic food container that some turtle will choke on?

We must be able to self-reflect on our own thoughts. To notice the inconsistencies, the missteps where the dissonance begins, and where catastrophe follows.

While the intentions behind aligning myself to be a “good environmentalist” are certainly admirable, the ideals that are pushed on us societally don’t always let us be our own guides. Societal messages about recycling the right way are intended to make us feel like we are not doing enough. In this way, discomfort becomes our driving force.

Yet, is blaming the system a way for me to wiggle my way out? To put the blame on something or someone else? Or, is there a way I can do my part while also rallying against a power that tries to amplify my dissonance?

And I have to wonder if this dissonance between thoughts is all bad. I wouldn’t want to be human without the grief and the guilt that comes along with it.

It seems there’s no exact cure, but it’s still possible to heal. To enter into the entropy and pave the way towards my dissonance decline. The deer is in my headlights, do I keep driving? H

Crafted using graphite on paper and inspired from botanizing in the field and personal work in the Pringle Herbarium, this piece marries experiencing nature and categorizing it using human constructs to comment on how our scientific understanding of plant life can both communicate important information while failing to capture the gestalt of experiencing botanical life in the field. H

ACROSS

1. Another publication on campus

4. UVM’s environmental publication

6. Iconic mascot (rawr!)

8. See 2-down

9. Tree with “burnt potato chip” bark

10. Busy Burlington beach

11. ____ Day, est. in April 1970

12. Fire residue, or of the genus Fraxinus

14. Third-floor cafe

19. Small brown thrushes known for their spiraling song

20. Rubentstein’s new Inclusive “____s” Initiative

22. Caffeine with populari-tea

24. Fruiting fungus

DOWN

2. Local lake monster

3. “Why is it so ugly? Put it back in Marsh” (the best girl)

4. VT state bird, with 8-across

5. Comedic campus newspaper

7. Organism made of fungi and algae

13. VT winter weather

15. Dudley H. ___ Center

16. School based in the Aiken Center

17. Standing dead tree popular with woodpeckers

18. Amphibian friend of Toad

21. Forestry major’s favorite plant

23. Mornings

Created by Loden Croll and Avery Redfern Find answers at headwatersmagazine.com

Art by James Marino

Created by Loden Croll and Avery Redfern Find answers at headwatersmagazine.com

Art by James Marino

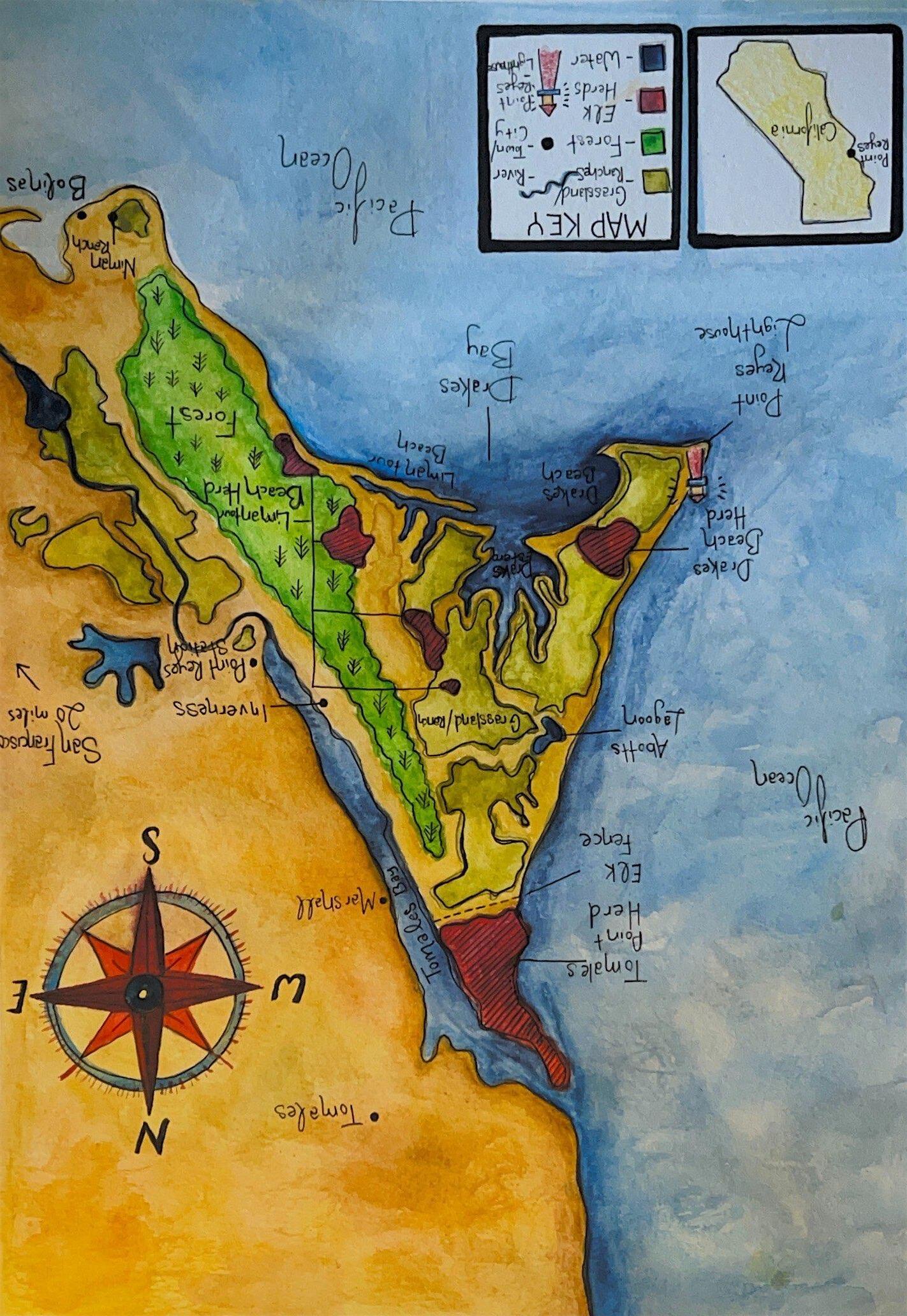

In the idyllic grasslands of Point Reyes National Seashore, an hour north of San Francisco, ranchers and environmentalists are battling over how best to use the public land. 28,000 of the Seashore’s total 71,028 acres are leased by cattle ranchers who specialize in fine dairy products and world-famous cheeses. The cattle thrive on the wind-swept grasslands of North Point Reyes, but the grasslands are also home to roughly 580 tule elk, an endangered species of elk endemic to California. During the 2010s, large-scale droughts caused mass die-offs of the tule elk, prompting the Seashore to adopt a policy of annually culling the population. This policy, combined with the die-offs, fanned the flames of a fierce controversy between pro-elk environmentalists and the ranching families leasing the grasslands. Currently, there are two lawsuits against the National Park Service, both seeking to remove the ranchers from Point Reyes and allow the elk populations to expand.

The ranchers claim they are preserving the rich agricultural heritage of the area, supporting sustainable agriculture, and building local food systems. Their opponents claim the ranchers are degrading the land for private profit while consigning the native species to a marginal existence. Both of these things are true. At the heart of this controversy is a question over land-use values: how do we weigh human use of the land against supporting native ecosystems?

The natural beauty of Point Reyes is an extraordinary resource, and anyone would consider themselves lucky to live near it. However, this natural beauty also attracts two groups currently threatening hundreds of rural communities across the US: tourists and vacation home buyers. The towns surrounding Point Reyes, all of which were once agricultural lands, have, in the past 20 years, become prohibitively expensive to live in, with houses regularly selling for seven million dollars or more. Families in these towns are being forced out, and most of the newcomers are extremely wealthy. Seen in this light, the ranching families of Point Reyes are a bastion against the gentrification brought on by the Seashore’s natural beauty.

Ranching has deep roots in Point Reyes, with some families tracing their lineage back to the first dairy ranches of the 1860s. They describe an intimate connection to the land, such as one man who grew up in the Seashore and said that “[you know] every nook and cranny of that place. You drive a tractor before you drive a truck… You’re one with the land…” These ranching families note their economic importance; food produced within the Seashore’s boundaries constitutes roughly 20% of the county’s agricultural output. Additionally, ranchers have consistently highlighted sustainability as a primary goal. All Seashore ranches are organic and have been willing to try methods such as rotational grazing or prescribed fire. Fourth-generation rancher David Evans states:

Today, my ranch provides habitat for several threat ened California native species, including the Califor nia Red Legged Frog, is home to several native grass es, and provides pastoral habitat for an extremely di verse ecosystem … We look forward to … securing at least 20-year leases after this planning phase, thereby confirming the critical role that ranching plays in maintaining our thriving and beautiful work ing landscape.

Currently, ranches are given five-year leases that have no guarantee of being renewed, and a major goal of the ranchers is to gain 20-year leases and the security they would provide.

On the other hand, because most of the pastoral land in Point Reyes is leased to private ranches, endangered tule elk populations are being killed. The story of tule elk in California is analogous to the story of bison in the Great Plains. Once, they were the primary grazers on most of California, with a population around 500,000, but overhunting and habitat destruction drove them to the brink of extinction. By the 1870s, this vital species was believed to be gone from this world. Then, miraculously, a cattle baron named Henry Miller found a dozen elk on his ranch in Southern California and decided to protect them. By 1914 the herd had grown to about 400,

large enough to cause $5,000-10,000 annually in damage to Miller’s cattle fences and irrigation works. Miller requested they be moved to a more suitable location, and relocation efforts led by the California Academy of Science established herds all across the state. Though there have been constant difficulties with overgrazing and conflict with ranchers ever since, the tule elk population has grown to about 5,700 statewide today.

However, continual relocation efforts were required, so, in 1978, the newly-created Point Reyes National Seashore was selected as a reserve. A suitable site was chosen, and a rancher in the far northern tip of Point Reyes was forced to give up his lease on 2,600 acres to make way for the elk. The peninsula, called Tomales Point, is covered in grassland and brush and slopes steeply on both sides down to the ocean. However, ranchers were concerned with the elk disturbing their operations, so an eightfoot high wire fence was built at the base of the peninsula, leaving the elk to their grassy finger of land.

Park scientists predicted the 2,600-acre reserve had a carrying capacity of 140 elk, and that the population would “naturally stabilize” around that number. But the herd grew explosively from 10 elk in 1978 to 550 in 1998, raising alarms for the managers. Following an environmental assessment in 1998, the park moved three dozen elk from the fenced Tomales herd to Limantour Beach, several miles south, in an area reserved for wilderness and absent of ranching. If all went smoothly, these free-ranging elk would spread out into the wilderness area, and the northern grasslands would be left to the ranchers. But, enterprising elk crossed an estuary separating the wilderness from the pastoral zone and started a third herd at Drake’s Beach, in the heart of ranching operations with no elk fences.

Just as they had with Henry Miller a century earlier, the elk quickly started causing problems for the ranchers. Elk broke through fragile cattle fences and grazed the forage meant for the cattle, forcing ranchers to buy hay and alfalfa. Cows also escaped

through the holes made by elk, mixing different cattle herds, breeding at the wrong times, and making precise management more difficult. On at least two occasions, bull elk gored cattle, killing them. Combined with damage to irrigation systems, these issues cost the most affected rancher $30,000.

The next 14 years were characterized by a Seashore paralyzed by bureaucracy. The 1998 plan that established the free-ranging Limantour herd did not plan for free-ranging elk in the ranchlands, and thus did not include that in their initial environmental assessment. If the Seashore made a new plan for the free-ranging elk, then it would be required to go through the long and costly process of completing a new environmental assessment. Instead, they employed such band-aid measures as “hazing,” which entails yelling at elk when they wander too near a ranch. It had no effect.

In 2014, the Seashore finally announced it was drafting a new Comprehensive Ranch Management Plan. It was largely a win for the ranchers because it extended their leases to 20 years, but it sparked the fiercest fight yet when it opened to public comment. To make matters worse, 2015 was one of the driest years in California history, and fenced-in elk at Tomales Point died by the hundreds. Dropping from 585 elk in 2007, only 283 elk remained on Tomales Point in 2015.

However, the free-ranging herds at Limantour and Drake’s Beach weathered the drought much better than the fenced-in herds. Proposals to build elk fences around the free-ranging herds and protect the ranches were therefore met with defiance by environmentalists, who still assert that fences kill elk in drought years.

Prompted by the die-offs and the new Ranch Plan, environmental organizations sued the Seashore in 2016, demanding that the Seashore update its 1988 General Management Plan and fully consider the environmental impact of ranching. In the settlement, the Ranch Plan was dismissed, the ranchers were given 5-year interim leases, and the Seashore was given 5 years to write a new Management Plan. That Management Plan opened to public comment in 2021, beginning the legal and cultural battle still raging today.

The 2021 Management Plan includes three alternative plans for this area, including one that fully removed ranching, and one that fully removed the elk. The park’s preferred plan, and the one they went forward with, extends the ranching leases to 20-year periods. To deal with overpopulation and overgrazing in the Tomales Point herd, the park plans to kill a number of elk every year to keep the population stable. Understandably, environmentalists were enraged.

First, a group of nearby residents sued, saying they were legally harmed by the sight of dead and dying tule elk in a place they visited for its natural beauty. They again cited the park’s failure to update their 1988 Plan, and demanded they include increased protection of tule elk. Inherent in this argument is the removal of the ranching operations. This lawsuit was dismissed by Judge Haywood Gilliam in March of 2023, who said, “The court is not indifferent to the conditions facing the Tule elk … but plaintiffs have not identified a viable legal basis that would entitle them, or the Court, to intervene in the Park Service’s wildlife management decisions.” The plaintiffs, supported by Harvard Law School’s Animal Law & Policy Clinic, appealed this decision, and it is currently still circulating through the California courts.

Meanwhile, a second case was brought against the park by three environmental organizations: the Center for Biological Diversity, the Resource Renewal Institute, and the Western Watersheds Project. In this case, the plaintiffs claim that by extending the leases to 20 years, the Park Service is failing to uphold laws to ensure maximum protection for natural resources. They also demand the ranching leases be terminated, so that tule elk could reclaim Point Reyes. This case hasn’t been decided yet and has the greatest potential consequences for the Point Reyes area.

While the district courts of California decide if the Park Service failed to uphold its directives, the public is left to decide what the Park Service’s land management goals should be. Does it allow for the preservation of a working landscape? Should human interaction with the land that harms that land be allowed? These questions are not merely theoretical, and the answers will determine the future of both ranching and tule elk in Point Reyes.

On the one hand, ranchers claim they are preserving the county’s working landscape and agricultural heritage while living “one with the land.” On the other, an endangered species is being culled because they cannot expand across Point Reyes’ best grazing land. If Point Reyes should be a purely natural ecosystem where native species can flourish, then ranching clearly must go. But if it should be a working landscape, where human practices like sustainable agriculture can operate alongside natural processes, then we must find a way for elk and ranchers to coexist. The controversy in Point Reyes is a particularly painful example of how these values clash, but similar disputes are being hashed out all across the country. For those studying the environment, deciding where to stand on these issues is difficult, but necessary to being good stewards of the land. H

Folded on the mossy carpet of the forest, I sense the lichens beneath my bare palms vibrating with life. My hearty kinfolk inhabiting the bodies of songbirds rejoice in musical blather. A blue heron moves gracefully over the creek, wading across her crystalline home with pride. The night renews once again over the green mountains, and I understand why I am here.

To bike in the blistering heat with gulls overhead, laughing until I reach the ocean, To eat homemade fruit and pound cake kabobs at the Iris Gardens picnic table, And hike the Grand Canyon and Mohonk Mountain in the chilly wintertime.

This world pumps love and energy into every being.

The sun warms the earth, extending growth and abundant creation of life across seasons. Flowers munch on the sugary rays as they unfold from a deep slumber in the early springtime. Squirrels scurry upon the branches of towering trees.

Spiders and ants meander into the crevices of grandfather logs.

To know I am one with these beautiful beings allows me to feel at peace. Every breath of fresh air gifts me a new reason to be.

I savor in the present moment, taking in every sense this generous world allows me to feel.

Earth wraps me in her brisk, sweet winds, Tracing my cheeks lovingly with crisp air, She wisps my brown curls into the breeze As I leap with my favorite people off of boulders, our bodies cascading into Lake Champlain.

Lightheaded with whimsy and love, she smiles down at me, lover of all beings, At you, a vibrant cranberry soul; At us, beautiful outlines of boisterous luminescence; Drowsy with her infinite epochs of wisdom and selflessness.

From Eagle Rock Reservation, To Forsythe National Wildlife Reserve, Held out are firm, protective hands over the Earth’s lands, Guarding the rich biodiversity that inhabits them, My truest friends.

The commons are not a tragedy, but a gift. A wondrous and awe-inspiring world I feel ever so lucky to live in reciprocity with.

Our Earth is not a resource to exploit, But a terrestrial and marine body pulsating with life, Asking to be cared for in her old age.

While there are still plants bursting through waves of photosynthetic joy, Manatees gliding through salty seas, Tigers moving stealthily across the savannah, Dung beetles, mosquitos, mole rats, and prokaryotes, Humans walking in parks, laughing over their lunches, and working to house their loved ones,

There is a world worth saving. H

If lichens aren’t mosses, what are they? Lichens are often mistaken for mosses; after all, these two groups grow in similar places, often side by side. Their names only add to the confusion—the term “moss” has been applied to many common names of lichens, such as reindeer moss.

The key difference between the two is that one is a plant, and one is not. Mosses are plants; they have stems and leaves that allow them to photosynthesize. Lichens, on the other hand, are composed of a symbiosis of fungus and photosynthetic algae. The fungus encases the algae, providing structure, protection, and moisture. In return, the algae feed the fungus photosynthesized sugars.

The fungus within lichen can reproduce via spores. However, the algae isn’t included in this reproduction, so the spores need to establish a relationship with an alga or it will die. Scientists aren’t entirely sure how the fungal-algae relationship is formed, but it is theorized that the algae could be transferred via mites or that some algae species can live freely for short amounts of time while they work to locate the fungal part of the lichen. More commonly, lichens reproduce vegetatively, meaning they can grow from a fragment of the parent lichen. They are also dispersed by other animals, such as squirrels or birds that use them in their nests.

Lichens come in all shapes, sizes, and colors. Some can live for centuries. They are often found as tufts on trees or crusty patches on rock. Inhabiting all areas of the world, from the Arctic to deserts, grasslands, tropical forests, and everything in between, these adaptable creatures have two main resiliency tactics. First, the fungus protects the algae inside from extreme conditions and from drying out. Second, lichens become dormant when growing conditions aren’t favorable. If the environment is too dry, they become brittle, less vibrant, and nearly inactive. When enough moisture comes along, they burst back to life, photosynthesizing and slowly but steadily growing. Lichens can go dormant for years, and have even survived journeys to outer space in dormancy!

Lichens can grow on just about any surface, natural or human-made. Commonly found on rock, bark, or soil, they are harmless to the surface on which they grow. Birds use them for nesting material, insects camouflage

against them, and they are a food source for many animals (although they’re not tasty to humans). Notably, they provide vital nutrition to reindeer and caribou during the long winter months around the North Pole. Covering about 7% of the Earth’s surface, these little organisms play an important role in their ecosystems at a much larger scale than individual relationships. Lichens benefit their environments by cycling carbon, fixing nitrogen, and retaining moisture. As some of the first species to appear on bare rock, lichens colonize environments and make way for soils to form so other species can grow. Despite their natural resiliency, lichens are vulnerable to atmospheric pollutants such as heavy metals, carbon, and sulfur. They need clean air to survive. Because of this sensitivity, very few are able to survive in polluted areas such as highways or cities and are thus threatened by urban sprawl and other development. Air pollution causes death in the algal component of lichens, similar to how corals expel their algae due to environmental stress and become bleached. Without the nutrients from pho tosynthesis, the rest of the lichen will die shortly after. Since each species of lichen has a unique pref erence for the quality of air in which they grow, they can be used as bio indicators to monitor air quality across America. A bioindi cator is a living organism that is used to evaluate the health of the envi ronment. Scientists use the USDA For est Service Nation al Lichens and Air Quality Database

and Clearinghouse to help land managers detect and evaluate trends to assess the impacts of air pollutants. The presence of pollutants in lichen samples is com pared to other air quality measurements to determine the health of the surrounding ecosystem. Since lichens are hypersensitive to changes in air quality, they are excep tional indicators of pollution levels. For example, if a sulfur-sensitive species begins to disappear in a region as a sulfur-loving lichen begins to thrive, scientists could infer that an atmospheric spike in sulfur occurred in that region and investigate further.

Like many species, lichens are also increasingly threatened by climate change. Their ability to survive in diverse and extreme environments means they’ve be come specialized to specific regional climates. Recent re search in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology that lichens are struggling to cope with rapidly shifting climates. According to Matthew Nelsen, scientist and lead author at the Field Museum of Natural History, “the predicted rate of modern climate change vastly exceeds the rate at which these algae have evolved in the past. This means that certain parts of their range are likely to become inhospitable to them.” The team of scientists found that lichens would need around one million years to adapt to a 1℃ temperature increase, which is less than the predicted rise in global temperatures expected by the end of the century. Rising global temperatures have also contributed to shifting patterns in forest fire frequency and intensity, another factor threatening lichen popula tions. Lichens are struggling to survive and recolonize after the heat, dryness, and smoke of unprecedentedly severe forest fires. However, lichens aren’t necessarily doomed to extinction. It is possible that some will adapt and others could redistribute to more suitable environ ments, though these shifts would result in compounding impacts throughout these ecosystems as their range ex-

However small or unsung lichens may be, their importance is undeniable. Aside from supporting entire ecosystems, not many species get a national database for their biomonitoring abilities. The next time you’re out and about, take a moment to inspect a nearby rock or tree and perhaps you will spot

Fruticose: 3D branched or “shrubby” structure

Without lichens, food chains would be significantly disrupted, particularly in extreme environments where they are depended upon, such as tundra ecosystems. Biodiversity across the landscape would deplete, impacting the food web more broadly, not to mention the habitat lichens provide for many creatures. Nutrient cycling and air quality would also be altered as these organisms’ ability to absorb nu-

The best time to observe lichens is right after (or during) a rainy period. Lichens will be active, vibrant, and colorful, making them wonderful to behold. They’ll be almost glowing green, yellow, or orange.

In the forest, most lichens will be found on bark/ wood. Many different types of lichen can often be found on the same surface.

Some common species of lichen you may find include monk’s hood lichen, reindeer moss, common greenshield, British soldier lichen, and beard lichen.

Field tip: If the weather’s been dry, hike with a spray bottle to dampen the lichens you find and watch them come to life!

A massive storm brought record flooding to Bar Harbor, Maine in early January of 2024, devastating local businesses and tearing down three iconic fishing shacks. These fishing shacks, which had weathered the brunt of Atlantic tempests for more than two centuries, now reside in the unforgiving ocean from a potent storm surge. Amidst the chaos, record floods breached town squares and interstate highways, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake. Susan McGee, a local of Bar Harbor, said, “I’ve seen a flood, but I’ve never seen anything like this, and I lived here for 35 years.”

Severe storms illuminate the vulnerability etched into coastal communities. How often must we confront these harrowing events, surpassing historical flood records with alarming frequency? This cataclysmic event not only highlights the immediate dangers posed by coastal storms, but also prompts deeper reflection of the urgent need to address the escalating threats of climate change to human livelihoods and fragile shoreline ecosystems.

Rising sea levels are a direct consequence of climate change, causing catastrophic damage to coastal communities. Warming oceans have set in motion a chain reaction of environmental upheaval, including increased frequency and severity of storms, rapid sea ice melt, and a substantial rise in seawater volume. Rising sea levels are encroaching upon global shores with relentless determination, leaving a trail of degradation in their wake. Natural barriers made to mitigate coastal threats are being pushed to their limits beyond a point of sustainable regeneration. With a diminishing availability of natural environmental defenses, communities around the globe are experiencing heightened vulnerability to natural disasters and climate-related hazards.

The phrase “coastal vulnerability” constitutes the susceptibility of coastal environments and communities to adverse impacts arising from the climate crisis. The interconnected chain reaction of climate change exac-

erbates the risks that coastal communities face, thereby increasing risks of flooding, erosion, and habitat destruction. These challenges extend far beyond immediate coastal areas, causing global environmental degradation, infrastructure damage, disruptions to recreation and local economies, and the loss of social and cultural connections. It is evident that coastal vulnerability is a complex and far-reaching problem that demands urgent attention and action, but where do we start? Though climate change is a worldwide issue, identifying regional differences can aid in tackling problems. Universal problem-solving can promote collaborative and international solutions, but place-based approaches better account for the distinct habitats and inhabitants of a small area. As of 2024, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reports that 127 million people live in coastal counties in the U.S., and more than 55 million of those reside in coastal communities in the Northeast. Identifying this region, with its massive density of humans and diverse wildlife habitats, provides a microcosm of the broader challenges faced by coastal communities worldwide, thus offering a localized approach and making possible solutions more applicable and tangible. Considering the unique environmental, socioeconomic, and cultural characteristics of the Northeast region

can facilitate the development of targeted strategies that address specific challenges faced by coastal communities in this area.

Sadia Crosby, owner of OsytHERS Sea Farm, operates a shellfish farm on the rapidly warming Gulf of Maine and experiences climate-related challenges. When asked what some of the ways a vulnerable coast has been impacting her business, Crosby notes the record-high storm surges and high winds that cause damage to the coast and make it unsafe for her to work on the farm, as it is only accessible by boat and has “little protection from the elements.” Additionally, the delicate balance of the ecosystem directly affects the health and productivity of the shellfish that grow on the farm. Oysters are extremely sensitive to changes in salinity and temperature, becoming ill and unproductive in the face of a changing ecosystem on the Gulf. This not only presents challenges for Crosby’s business and income, but also reflects the broader implications for the resilience of marine life, underscoring the intricate link between human livelihoods and the wellbeing of coastal environments.

Coastal changes are also associated with human health risks. Damage to infrastructure and roads can pose physical threats to people, potentially resulting in injury or death. Exposure to infectious waterborne diseases is expected to increase as a result of climate change-induced coastal changes like sewage overflow and runoff, carrying substantial threats to coastal Northeasterners’ health and development. Regarding emotional health, sea level rise is linked to increased psychological distress in individuals. In addition to finding solutions to combat climate change along coasts, services to support people experiencing loss and pain are necessary. The ramifications of climate change on coastal regions encompass a spectrum of health hazards, highlighting the urgent need for holistic approaches toward resilience and adaptation.

Many cities in the Northeast, like Boston and New York City, were established along coasts as hubs for international commerce. A large proportion of the Northeast’s residents reside in these coastal cities, presenting serious potential for environmental injustices. US Geological Survey data identify that more than 67,000 people along the Eastern Seaboard are at risk of displacement due to changes in coastal conditions. According to author Jake Bittle, “The Great Displacement,” or the next American migration, will be caused by climate change throughout the country, and it has already begun. As climate-related displacement intensifies, communities with limited access to critical resources—including BIPOC and lower-income—are disproportionately affected. Barriers to secure resources and opportunities demonstrate the importance of equitable, safe, and affordable access to housing in the face of climate-induced displacement.

Just as humans will be displaced from their homes, wildlife are being displaced from their natural environments. Atlantic marsh fiddler crabs inhabit salt marshes along the Atlantic coast, serving as important keystone species to the region. Rising sea levels and changes in temperatures have led to fiddler crab displacement and habitat loss. These crabs are an important food source for shorebirds and fishes; they are ecosystem engineers, influencing nutrient cycling, coastal vegetation, and sediment dynamics. The displacement of fiddler crabs affects species distributions and trophic interactions within their ecosystems, leading to shifts in the community structure of coastal environments. According to wildlife researchers Raymond Pierotti and Daniel Wildcat, traditional ecological knowledge posits that no single organism can exist without the web of life forms around it. This highlights the interconnectedness of all species, demonstrating how a shift in fiddler crab range can, in turn, prompt unintended victims of coastal threats.

Habitat loss is the number one threat to wildlife around the world. As coasts become increasingly fragile, species within these areas experience habitat loss and fragmentation. Carolyn Mostello, a coastal waterbird biologist at MassWildlife, has been studying the interactions between terns and coastal threats on Bird Island in Marion, Massachusetts. Coastal habitats serve as crucial breeding grounds, feeding areas, and refuges for a diverse array of plant and animal species. Sea birds dynamically inhabit marine and terrestrial habitats, making them extremely vulnerable to climate change. The nesting grounds of roseate terns on Bird Island now confront the peril of sea level rise and storm destruction, resulting in habitat loss and diminished breeding opportunities. According to Mostello, “Oceans bordering New England are warming faster than most areas of the world.” Mostello also mentioned a subsequent decrease in the abundance of roseate tern prey due to rising temperatures, thus heightening the terns’ vulnerability to habitat changes. In a parallel struggle, common terns, which share similar nesting areas with roseate terns, face habitat alterations due to sea level rise, which has transformed their traditional beach habitats into unsuitable salt marshes. Consequently, common terns have encroached upon and displaced roseate terns. Mostello recognizes the importance of protecting both species, stating, “If we weren’t out here working every summer and didn’t intensively manage the island, you would again see the [tern populations] decline very quickly.” Habitat restoration efforts on the island are successful in their results of increasing respective roseate and common tern populations. Increasing resiliency of coastlines to storms and sea level rise will enact and highlight potential solutions for better coexistence between these critical species. Urgent awareness and action are necessary to protect the human and non-human communities who are affected by increasingly vulnerable coasts, before it becomes too late. When considering actions to fight climate

Art by Casey Benderoth

change, a question naturally arises: how do we address this multifaceted and complex challenge? It is best to begin by identifying and implementing localized adaptation strategies. One approach can involve policy interventions and collaborative governance techniques. This broad application looks at the issue from a top-down perspective, commencing change from a federal, state, or municipal level and involving a fostered collaboration among all stakeholders. Measures may include ecosystem restoration, investment in infrastructure, coastal zone management, or risk assessment and planning. The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection contains a Bureau of Climate Resilience Planning. Nick Angarone, the manager of this bureau and New Jersey’s Chief Resilience Officer, recognizes the importance of political collaboration and teamwork in addressing coastal vulnerability. “[We work] with local governments and residents to communicate the risk of climate change, plan its impacts, and implement resilience solutions that benefit both our communities and our natural environments,” Angarone said.

The question of adaptation or mitigation when adressing coastal vulnerability revolves around determining the most effective strategies to cope with and combat the impacts of a changing environment. Adaptation involves adjusting to the existing or anticipated impacts of climate change by adhering to existing societal frameworks. On the other hand, mitigation focuses on reducing causes of climate change before they become too severe, or creating new societal systems that are aligned with the goal of environmental stability and resilience. Ultimately, the choice between adaptation and mitigation depends on resource availability, severity of impact within a given location, and the level of tangibility. By implementing localized adaptation strategies and integrative policy interventions, coastal communities in the Northeast can enhance their resilience to environmental challenges and safeguard interconnected ecological systems.

Community and nature-based approaches can also be used to address coastal vulnerability in the form of bottom-up action. Implementing living shorelines, dune restoration, and wetland protection provides natural buffers to coastal hazards, not only enhancing resilience but also providing multiple co-benefits for all biotic and abiotic beings. When New York City was hit by Hurricane Sandy in 2012, damage to the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge’s coast and the mixing of seawater with freshwater resulted in the formation of brackish ponds, harming wildlife and recreationists. To buffer flooding, purify water, and better protect the coast from erosion, a living shoreline project was proposed with the help of local community members and dedicated volunteers. A living shoreline is a protected and stabilized shoreline that is made of natural materials, according to NOAA. This shoreline required 2,600 feet of recycled Christmas trees, coconut fibers, native grasses and shrubs, and more than 5,000 oyster shells to be used for shoreline restoration. Jennifer Nersesian, the superintendent of Gateway National Park where the living shoreline was implemented, states that “The Living Shoreline Project shows that rather than trying to fight nature, we’re learning to embrace it.”

Off Long Island Sound in Connecticut, the Stratford Point Living Shoreline consists of a shellfish reef out of cement “reef balls” to establish natural protections against wave energy and disrupt coastal