28 minute read

VI. Post-totalitarian authoritarianisms: developments, characteristics, and variants

For transformation research, the question regarding the point in time at which institutionalised political systems emerge is of particular importance. If the transformation of Soviet socialism into something else can be structured in the phases of existential systemic crisis, political upheaval, and the actual reforms, the emergence of new political systems do not fall into the same phase in all countries.

With the renunciation of totalitarian ideology, the already observable or in some countries even “exploding” pluralisation was stripped of its subversiveness. Thus, both totalitarianism and possible attempts to save it with the use of state violence were deprived of their legitimacy. This process contributed not least to the failure of the strangely indecisive coup that was carried out in the Soviet Union in August 1991. In a figurative sense, with the “writing off” of totalitarian ideology, “real reality” was finally politically accepted.

Advertisement

Although it could be assumed that in the peripheral countries of the communist empire at the end of the 1980s, tinkering with the communist system would no longer automatically provoke military intervention by the Soviet Union, the communist rulers had a violence apparatus that was still operational. Due to this reason, it was advisable, especially in the geopolitically important states of the Eastern Bloc, to persuade them to voluntarily abandon ideology and thus seal the institutionalisation of the system.

Even if the assertion is true that no post-communist democracy could be considered institutionalised before free and democratic elections are held, this does not mean, conversely, that it indicates the institutionalisation of democracy.

The establishment of post-communist democracy or post-communist authoritarianism took more time in some countries and less time in others because the historical and systemic

Transitional authoritarianism

Nationalist legitimacy preconditions for the system change were different in the respective societies (see Figure 1: Social preconditions of post-communist transformation in the appendix). Also, the political elites of respective countries acted differently. If one takes these factor complexes into account – the broad historical (pre-communist) heritage, the formative systemic heritage of the old regime, and the politics of system transformation – it becomes clear why one cannot easily name universal indicators of the institutionalisation of a new political system.

It is appropriate to take the status of the political opposition, rather than the elections, as an important indicator. If the opposition is so weak that it fulfils at best a function of criticism and has no chance of taking power in elections, authoritarianism must be considered institutionalised. This, of course, has consequences for elections: in institutionalised authoritarianism, elections are usually “won” by those in power even if they are unpopular.

Transitional authoritarianism existed in all post-communist countries in the period between the abandonment of totalitarian ideology and the institutionalisation of a new system. During this period, effective democratic legitimation was sought. However, another strand of legitimacy proved to be perhaps even more significant: the desire for political sovereignty for the nation, in other words, nationalism. Nationalist legitimacy helped to forge compromises between the political camps, which otherwise had little in common. In particular, the nationalism of the transitional system proved capable of improving the dreary reality by raising the hope for a better future in their own nation-state.

Nationalism can thus certainly be a constructive force for a promising political compromise. However, if such a consensus is not reached, nationalism represents a great danger. In countries such as the German Democratic Republic, where the political elites were too far removed from the national movement, the political process was shifted to the streets. The slogan “We are the people,” known from demonstrations in the GDR, was not unproblematic. As Ralf Dahrendorf warned: “’We are the people’ is afine slogan, however, as a constitutional maxim, it is a reflection of the total state that has just been eliminated. If the party’s monopoly is replaced only by the victory of the masses, everything will be lost in a short time, because the masses have neither structure nor duration.” It is difficult to believe, however, that

this was a movement that was more democratic than the country’s political elite with its few “democratic socialists” and the even rarer democrats. The democratic and nationalist politicians of the Federal Republic of Germany came at just the right time moment, in March 1990, when they gradually assumed de facto political responsibility for both the national movement (“We are one people”) and the orderly dissolution of the GDR. Whether the transitional authoritarianism in the GDR would have led to a democracy without this patronage of the Western part of Germany may at least be open to doubt, especially since Eastern Germany was economically ruined.

Where, in turn, nationalism could not be used to successfully legitimise the sovereign democratic state, the transitional system suffered from a serious lack of legitimacy. In Belarus, which was nationally largely indifferent, Aleksandr Lukashenka was able to gain autocratic power relatively easily, because his explicit distancing from the Belarusian National Front, which itself was only partially democratic, certainly did not harm him.

In Russia, both Boris Yeltsin and Wladimir Putin were desperately trying to mix a legitimacy “mash,” using ingredients such as Alexander I., Nikolai I., the Soviet anthem, the Lenin mummy, the Red Flag and the Russian tricolour. Putin and his “political technologists” came up with the idea of adding to this the thought that the presidency of Boris Yeltsin, the period of the greatest freedom in Russian history, had actually been the “smuta” (“period of turmoil”) which has now been happily overcome.

As far as Czechoslovak transitional authoritarianism is concerned, it did not survive the probationary period because there simply could be no Czechoslovak nationalism.

Finally, in Ukraine, the different national identities have continued to hamper the legitimacy of the post-communist system, even as recently as the Russian aggression in Crimea and Donbass in 2014.

And yet it must be repeated: the fact that nationalism may serve democracy well does not mean that this ideology cannot be a good servant of authoritarianism.

Since transitional authoritarianism per se cannot be democratic, whether the election campaigns are conducted according to the standard norms is of particular importance. There is an insurmountable gap between the transitional authoritarianisms of

institutionalised authoritarianisms Lithuania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Slovakia, on the one hand, and Russia and Ukraine before the Orange Revolution in 2004 and Georgia before the Rose Revolution in 2003, on the other.

As far as institutionalised authoritarianisms are concerned, they hardly know a fair election process. The claim of a democratic ethos by those in power are merely feigned and democratic procedures degenerate into – admittedly – indispensable instruments for gaining legitimacy and securing power. Since the rulers themselves decisively determine the outcome of the elections, the democratic character of the elections is undermined, which is why the system merely deserves the predicate “quasi-democratic.”

Transitional authoritarianism could not be a democracy, but the elites in this system were in general able both to practise political competition and to act by the constitution and laws. Care should have been taken not to turn such competition into a power struggle that layers the political process, in order to be able to cautiously change the law that has its roots in the communist era and to adapt the behaviour of political actors to it. The golden formula said that the new constitutionalism should be strengthened at the expense of the new competition. This “optimal imbalance” for the transitional system could be brought about by a particular political constellation: the chances for democracy were quite good in situations where a national-democratic consensus prevailed within the political elite, renewed by the legalisation of political opposition. In Poland, Hungary and the GDR, the round tables served to limit political competition and strengthen the rules of the pluralist system. In Czechoslovakia, on the other hand, the non-institutionalised round table and, above all, informal agreements among the elites even decided to renounce competition by laying down the modalities for the smoothest possible transfer of power to the opposition. For in both (constituent) states of Czechoslovakia, the resignation of the communist government was considered necessary. Finally, in Lithuania, the almost untamed desire for a democratic nation-state united the rulers and the opposition and helped to restrict political competition in such a way that the open political struggle did not threaten the democratic system change.

In all these countries, a political consensus has contributed significantly to the fact that communist legal nihilists sought

protection from spontaneous punishment in a functioning constitutional state. From this perspective, constitutional democracy, whose procedures they were already able to try out in their negotiations with the opposition, now appeared to them to be an acceptable system. Remarkably, the convinced or cynical communist anti-democrats from very different countries showed the same attitude: in Poland, where there was a comparatively strong and very well organised opposition, in Lithuania with its large Sąjūdis movement and the threatening Kremlin, and in Hungary, with its ultimately very weak opposition that nevertheless was much stronger than the tiny “civic” forums in Czechoslovakia and the GDR.

The power vacuum created by the rapid collapse of totalitarianism cannot, of course, be measured. However, it must have resembled a black hole if small groups of the new opposition had to be accepted as negotiating partners – or even as new authorities – by the communists. The communists in Czechoslovakia, Russia, Ukraine, Georgia, and Belarus, for example, experienced just such an unexpectedly rapid and complete decline of their power.

Boris Yeltsin had the recalcitrant insubordinate Parliament bombarded during the crisis of September and October 1993, thus accepting responsibility for the deaths of several people, mainly members of Parliament. This prevented the development of a political consensus (which Yeltsin never sought anyway), which is why in December of the same year, the adoption of the constitution had to be pushed through. However, doubts as to whether the official results of the constitutional referendum reflected reality could never be completely dispelled. In November 1996, Aleksandr Lukashenka took action against the Belarusian Parliament, which he did not approve of, in a less brutal but by no means softer manner, and in an equally unconstitutional way.

If the power vacuum results from the conflict between the executive and the parliament, then the chances of victory for aparliamentary assembly, which has little opportunity to turn off electricity and water to the enemy, or to move in with tanks and deploy hundreds of police forces, are rather limited. And a victory of the executive over the parliament achieved by force, especially in a life-and-death struggle (even if deadly only for one of the conflict parties), always means a victory over the political

Ukraine’s transitional system opposition, political pluralism, and democracy. Political pluralism and the political opposition were objectively weak in both Russia and Belarus, but with their relatively long history at the end of the old system, they were better developed and organised than in the GDR or Czechoslovakia. However, since there was no national consensus, the gaining and securing of power almost exclusively constituted the content of the political process. Under such conditions, the rampant political competition could not be brought onto the constitutional track nor could it be controlled. This development, which in fact took on an anarchic character, was therefore prevented in a blatantly unconstitutional way by the post-communist leadership. The power vacuum, along with the prospect for democracy in the foreseeable future, thus disappeared.

The situation was different in Ukraine’s transitional system. There, too, the power vacuum and the difficulties of achieving a promising political consensus on a nation-state basis specific to post-totalitarianism were well known. There, too, the conflict between the presidentialchief executive and Parliament raged at times. The power vacuum was initially filled by the “technocratic” of the nomenklatura, who, with the explicit approval of President Leonid Kravtchuk, had taken root in the government executive. However, Kravtchuk, unlike Yeltsin and Lukashenka, did not necessarily want to prevent the constitutionalisation of the system. In view of his progressive loss of power, he indeed seized total executive power in September 1993 by decree. However, he then accepted the early presidential election the following year, in which he promptly lost against Leonid Kutchma. By resisting the temptation to defend his power by unconstitutional means, he earned the well-meant title of “almost a real democrat.”

Not all authoritarian leaders in the first post-communist period were so ready or willing to literally walk over dead bodies in the political struggle: Kravtchuk and Eduard Shevardnadze in Georgia were among them. They simply resigned after losing the political struggle. The pluralistic and democratic traits of the new systems could be institutionalised in their countries spontaneously, so to speak, when the authoritarian rulers succumbed. The pluralisation of the communist system could then take place “by default.”

On the other hand, flawless democrats who worked hard to build democracy and failed because their people were not prepared for democracy are virtually unknown.

Boris Yeltsin was not such an unfortunate democrat. He systematically subordinated the Presidential Administration, the government, the Security Council, the army and the secret services. The clientelism of the new system also helped him to secure – if and when necessary – support in parliament, in the courts, or of administrative authorities. President Putin, who had been declared a “flawless democrat” by German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, sought to strengthen the “power vertical” inherited from Yeltsin by means of the subjugation of regions, the mass media, and the party system (keyword: “controlled party pluralism”). Even Boris Yeltsin had eagerly pursued the parliamentarisation of the political system, with the obvious intention of strengthening the president’s position in a country where hardly any political party remained that had not already been more or less subordinated beneath him. He also ensured that the head of state’s influence – albeit limited – on the judiciary (Constitutional Court) was institutionally strengthened.

These examples confirm the assumption that authoritarianism has been built deliberately. It does not emerge by default, even if a bought German politician suggests the opposite.

During “difficult times,” an executive that is capable of taking action is of great benefit and need not be detrimental to democratic development, even if, when measured against the standards of Western democracies, it is given asymmetrical power. The same can confidently be said about the informal decision-making structures, which, also in the West, are not only a kind of inevitable supplement to the prescribed decision-making channels but can also take on quite repulsive forms in the long term; for example, in the elimination of inner-party democracy or the artificial marginalisation of the political opposition by permanent coalitions of the major parties, which merely pretend to compete with each other. However, when the institutional dominance of the executive and the non-transparent decision-making channels coincide with limiting restraint or persecution of the opposition by illegal uses of the state power apparatus, democratic legitimation is no longer sufficient to conceal the authoritarian character of the system.

For example, there can be no doubt about the non-legal character of Belarusian authoritarianism; it can also be highly repressive as it did not shy away even from political murder. Putin’s authoritarianism has similarly repressive traits, whereby the worst persecution offences occur selectively. In everyday life, however, the suppression of the opposition relies on the compliance of the executive, administration, and the judiciary. Under Yeltsin, the opposition found itself in better circumstances, which, according to Lilia Shevtsova, was in large part due to the character traits of the President:

Yeltsin showed a feeling for democracy. He understood the significance of basic civil liberties and did not attack them. He could tolerate criticism, albeit with difficulty, even when it was ruthless. For instance, he never touched journalists, even those who made it their business to attack him. He knew how to appeal directly to the people in his struggle with the state apparatus and his opponents, and he understood the power of the people.

Already in the nineties, the presidential centre of power was above the law in Russia. However, the enforced conformity of the party system, society (pluralism of associations and media), and the regions was ruled out by the President, which benefited the political scope of the opposition. It should also not be forgotten that under Yeltsin, the “parties of power” loyal to him could not be guaranteed any election victories. However, the presidential elections were far more important in the Russian system and Yeltsin used all available state means to guarantee the election outcome in 1996, and for a smooth transition to his successor. Asimilar situation occurred in Ukraine under early Kutchma and in Georgia under President Eduard Shevardnadze.

Political leadership in institutionalised authoritarianism is based on selective law enforcement and nihilistic legal culture. They correspond roughly to the nominalistic validity of the constitution, in the Karl Loewenstein sense. The authoritarian rulers in post-communism are interested in creating and maintaining the impression of the rule of law. For this purpose, it is necessary to have the infrastructure of a constitutional state – court buildings with equipment, judges, lawyers, legislative texts – which can function better or worse in the everyday life of the given legal culture. At the same time, attempts are made to

design the constitution and laws in such a way that they can be used against political opponents. From a political point of view, however, it is equally important that in the judiciary, certain decisions can be made according to political needs. Whether this involves the separation of powers, the independence of judges, the effective recognition of fundamental rights, the legality of the administration, legal security, or the guarantee of rights in criminal proceedings, these elements of the constitutional state can easily be overridden in institutionalized post-totalitarian authoritarianism.

In this system, the opposition does not need to make any major mistakes in order to provide advantages for those in power. The opposition is simply weak because it has emerged from a poorly organised and politically inactive society. The political leadership merely exploits the underdevelopment of pluralism. The few new actors from the society, who usually owe their political significance to wealth (“oligarchs”), usually come to terms with politics in order to run their business, often with the help of corrupt authorities. Despite this, those in power are afraid of the political opposition, which is why they set examples by repressing political opponents, rewriting electoral laws to the disadvantage of the opposition, and literally scattering demonstrations against the government.

Not least, the experience with Soviet socialism speaks for the fact that all power is transitory. The passivity and organisational weakness of society are not connected to the fundamental inability to mobilise it against the ruling class. Political mobilisation, which often seems astonishing in terms of its scale, can still be observed in authoritarianism. Even in the “classic” post-Soviet, non-civil-societies such as Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine, large crowds of people can sometimes be mobilised for political objectives. Authorities must, therefore, be able to win over the weakly organised and passive population. However, this requires at least a rudimentary level of efficiency on the part of the state.

Great hopes for the democratisation of post-communist authoritarianism are tied to the commitment of the West. The collaboration of the “international civil society” with the organised domestic opposition, such as what occurred in Ukraine during the “Orange Revolution” in 2003–2004 (and the Maidan movement in 2013–2014), as well as in Georgia during the “Rose Revolution,”

“international civil society”

has certainly had an effect. However, the precondition for this success was the mobilisation of the population, which can only be achieved by a sufficiently strong domestic opposition (including oligarchs).

Significantly, it is not possible to say clearly what the anti-systemic nature of the opposition responsible for the “revolutions” refers to. Quite a few of its actors ultimately understood their fight against “the Kutchma system” and “the Shevardnadze system” as a fight for “the system without Kutchma” or “without Shevardnadze.” This is not surprising since in both countries the opposition came out of the system, which broke the oligarchy. Also in both countries, the opposition was able to mobilise an astonishing number of people for, in both specific cases, greatly democratic popular movements. In both countries, this movement and the opposition that led it expressed the expectations of national independence in a very credible way, whereby pro-Western attitudes were not mere rhetoric. Ultimately, however, the hopes of people in both countries have gone unfulfilled. Have the democratic expectations associated with Ukraine and Georgia, as well as the main new hopes of democracy in the large geographical area of Eastern Europe, really been completely disappointed?

One thing is certain: in these countries, it is no longer known before the elections who will win – so their political systems are undoubtedly now decisively different from their predecessor systems, as well as from Russia and Belarus. Moreover, there can be no doubt that Georgia and Ukraine have political and social pluralism that, although objectively weak, is still the best developed among the institutionalised post-Soviet authoritarian regimes. Its limitations are not necessarily due to politically intended violations of the constitutional state and the rule of law, although the condition of the legal system in the Ukraine is still miserable. Rather, the quality of political competition is the biggest problem for democracy in both countries.

In 1991, Adam Przeworski wrote in his highly acclaimed book about democracy and the market, that Spain – which in just 15years had achieved the “consolidation” of democratic institutions and left behind the economy, politics, and culture of “poor capitalism” – was a miracle.

In contrast, the systems in Ukraine and Georgia are certainly not “picture-book” democracies. However, one would have to look

for such democracies in the West with a magnifier, not to mention amongst post-communist EU members. Corruption, self-satisfied simplicity of the political elite, incompetence, and inefficiency of the administration, bad laws, judges and courts, lack of resources– it is by no means difficult to find numerous examples of these phenomena in Poland, the Czech Republic, or Bulgaria, for example. However, all these post-communist systems are democracies that by no means function satisfactorily. The fact that Georgia and Ukraine, after a long period of Russian rule and several decades of communist barbarism, have almost reached this point within twenty years is a true miracle.

It shows that it is apparently possible to achieve democracy without looking back upon a long tradition of a normative constitution. It seems sufficient for liberal constitutionalism to be practised at a fairly low level: with a constitutional state and rule of law that do not function satisfactorily, but with the constitution entirely accepted as the central rulebook of politics by political actors. The change in the mentality of the political elites is also very important. If in Eastern Europe, of all places, decision-makers are moving away from the mindset according to which the political opponent is an enemy and must be destroyed, the political culture will be revolutionised. There is no reason for historical fatalism. This applies even to Belarus and Russia if they succeed in getting rid of the respective fate of thoroughly undemocratic state leadership. In today’s (June 2020) Belarus, the hopes for such change are considerable.

External actors from the West can do more than usual for both countries in these difficult times, in which institutionalized democracy is nevertheless within reach in Georgia and Ukraine, especially since the Kremlin still leaves no doubt that Western democracy in its neighboring countries is a thorn in its side. Not only the European Union, but also the European nation-states, including the Federal Republic of Germany, which unfortunately has so far acted merely out of pecuniary motivation (keyword: Nord Stream) and apparently without any European vision in its “Ostpolitik,” could, through consistent political support of both states, make a significant contribution to ensuring that no new authoritarianism is established there and that democracies become institutionalised. The EU is still unable to show the Ukraine any prospect of accession because of its dividing nationalisms.

Things look a little better with Georgia, especially since the USA is also strongly involved there.

Post-totalitarian authoritarianisms have not yet stepped out of the shadow of the totalitarian system, nor out of the long shadow of the Tsarist Empire. On the other hand, some of them practise political pluralism in the only way possible for them to take into account all their unfavourable preconditions. They have opted for freedom so that with new pluralism, civic culture has also moved into Soviet towns, and free public discourse has flourished. Moreover, following the introduction of the market economy, outdated technologies are gradually being replaced by current ones.

Even if all of these processes pass off with difficulty and cause numerous conflicts, they are changing the social consciousness in such a way that more and more people recognize the problems to be solved. Against this background, in Georgia and Ukraine, not to mention the post-communist democracies, the totalitarian system has long since become a thing of the past, despite the communist legacy.

All the more depressing, however, is the partial institutional and ideological continuity with totalitarianism, which Lukashenka and Putin are deliberately creating. This continuity not only clouds the joy of new freedom, because it cannot be expressed. Moreover, it makes it more difficult to modernise post-communist societies by at least partially preserving the pathological states that have emerged from the old system. For instance, market mechanisms are practiced without aiming at the autonomy of the economy from politics. Furthermore, the ultimately modern and educated societies cannot get rid of their political culture as subjects of the state; they also have to accept dramatic restrictions on freedom of expression.

It has been suggested several times that transitional authoritarianisms can in principle be divided into systems based on consensus and systems lacking consensus. Consensus contributes to a norm-oriented interaction between government and the opposition, thus strengthening the constitutional dimension of the system and increasing the chances of democracy. The example of Slovakia in the state-building phase under Mečiar showed that this consensus is fragile and can crumble, allowing transitional authoritarianism to “slip into” a less promising variant.

Authoritarianisms that lack consensus are dominated by arampant executive. This dominance can intensify political competition and cause a permanent conflict between the executive and the (parliamentary) opposition. If in this conflict, the executive weakens the opposition by unconstitutional means to such an extent that the latter becomes incapable of presenting an alternative to the government, authoritarianism is institutionalised.

The institutionalised post-totalitarian authoritarianisms

are all quasi-democratic and non-constitutional systems. As such they appear in a few variants or subtypes.

When creating variants of institutionalised authoritarianism, it is especially important to consider the role of the real opposition in the system. True (real) opposition is understood to be the force that actually strives for power, as opposed to the “controlled” or “virtual” opposition, which – possibly founded and always promoted by those in power – is used to prevent political pluralism. Of the systems examined here, Belarus after 1996, Russia after 2000, and Ukraine under the late President Kutchma, stand for such an “authoritarianism without alternatives,” in which the weak real opposition is marginalised by the state and, therefore, acts outside the system oligarchy (like in Russia and the Ukraine) or the autocratic networks (like in Belarus).

The political leadership in the “authoritarianisms without alternatives” may allow the controlled opposition to participate in the system by ensuring that only the “party of power” linked to the executive centre and the (virtual) parties of the controlled opposition are elected to parliament. This is also the situation in Central Asia, which could not be considered in this book. “Authoritarianisms without alternatives” (with a marginalized real opposition) bear most similarities to the totalitarian predecessor system and can, therefore, be described as genuinely post-totalitarian.

These systems are contrasted with the competitive authoritarianisms as in Georgia under Eduard Shevardnadze, Ukraine under the early Kutchma, and possibly Russia under Boris Yeltsin. The competitive authoritarianisms do not know the open outcome of (fair) elections, but they do know the real opposition in the system. They are very far removed from totalitarianism and are basically no different from similar authoritarianisms in other parts of the world.

quasi-democratic and non-constitutional systems

competitive authoritarianisms

In these systems, the opposition is striving for power, and can either be system-compliant or system-subversive. The latter wants system change, i.e. it aspires for power not exclusively for the sake of getting it. If this opposition comes to power in forcedly free, democratic, and fair elections, competitive authoritarianism can indeed be successfully put on the democratisation path (Georgia and Ukraine). If this scenario is unlikely, then – as in the transition from Yeltsin to Putin – a development towards genuinely post-totalitarian authoritarianism is also possible.

In both variants of quasi-democratic authoritarianism, the political process takes place out of public view, beneath the surface of formal institutions, including political parties. This is most clearly illustrated by the phenomenon of the “party of power.”

“Party of power” is understood to mean two things. On the one hand, it is the so-called hidden party of power, i.e. an informal network of relations between state institutions (media, business enterprises, secret services, the judicial system, and administration) and private business, which gather around the (usually presidential) executive branch. The people involved form the oligarchy of the authoritarian system. The oligarchy brands itself a face by formally founding a political party. The work of this “virtual” political party creation is supported by the resources of the “hidden party of power”: money from the private and state economy, state and private media, public authorities, secret services, the public prosecutor’s office, and the like. This party creation is also often called the “party of power,” although in this context the term “shield of the (hidden) party of power” would certainly be more appropriate.

The peculiarity of the authoritarian “parties of power” is that they can disregard the laws. Consequently, they do not act exclusively in those spaces that are destined for informal bargaining, but rather ensure that the boundaries between formal and informal decision-making channels are completely removed.

In addition to the shield of the party of power, numerous other “virtual parties” (“phantom parties”) are founded by those in power, especially during election periods. These can serve different purposes. For example, they can be used to ensure that an economic network (“clan”) is represented in parliament. Or they try to take away electoral votes of an opposing political party and

establish an “imitation” of this party, which is then lavishly provided with election campaign resources.

The programmes of phantom parties have nothing to do with the search for solutions to problems. They usually do not bother to bundle and articulate social interests at all and are almost afraid of the idea that their supporters and members could be socialised into politically active citizens. They rarely even fulfil the recruitment function, because party careers only play a minor role in the recruitment of political elites. Moreover, the names and political programmes of the parties usually say little or nothing about their actual ideological preferences, and it even happens that these are intended to be concealed. Even some party names – “Right Forces,” “Directors of Industrial Enterprises,” “Women,” and the like – are downright treacherous in this context, because they exclusively address certain social groups, which especially in election periods must feed the usually justified suspicion that they are supposed to collect votes for someone. Even the sometimes-noble titles that join the ranks of European party families have been given to party names – “liberal,” “national,” “Christian-democratic,” “conservative,” etc. – which often serve the purpose of concealing the powerful backers of the phantom party.

Finally, here are a few short theses on the variants and characteristics of the authoritarian systems in post-communism: All post-totalitarian societies had a transitional authoritarianism, which was either authoritarianism based on consensus or authoritarianism lacking consensus. The institutionalised, post-totalitarian authoritarianism develops from the consensus-free transitional authoritarianism. It is always quasi-democratic and non-constitutional. The first subtype of institutionalised post-totalitarian authoritarianism is competitive authoritarianism (with a real opposition). It appears as an oligarchic system (Yeltsin’s

Russia, Ukraine). Democracy can develop out of it if the system-subversive opposition wins power by legal means and constitutionalism is strengthened. The second subtype of institutionalised post-totalitarian authoritarianism is the authoritarianism without alternatives (without true opposition integrated into the system). It is extraordinarily strongly influenced by the totalitarian system (genuinely post-totalitarian). It appears as an autocratic

system (Putin’s Russia, Lukashenka’s Belarus). It can be externally supported (Belarus). Party systems in all post-communist authoritarianisms are extremely underdeveloped.

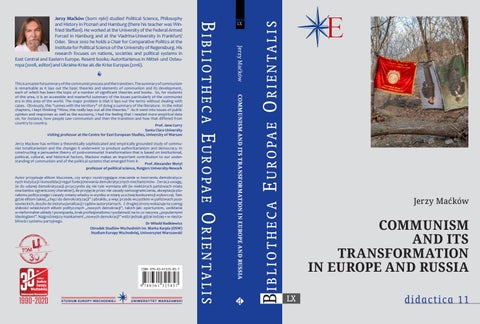

Both the types of post-totalitarian authoritarianism and the pathways of post-communist system change are illustrated in the Figure 2. The pillars indicate the direction of possible system change.

Figure 2: Developments and variants of post-totalitarian authoritarianism

communist totalitarianism

transitional authoritarianism

based on consensus

institutionalized democracy lacking consensus

institutionalized authoritarianism

competitive without alternatives (genuinely posttotalitarian)

institutionalized democracy

Recommended literature

Dahrendorf, Ralf, Reflections on the Revolution in Europe: In a letter intended to have been sent to a gentleman in Warsaw, New York 1990.

Levitsky, Steven/ Way, Lucan A., Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regime Change in Peru and Ukraine in Comparative Perspective, “Studies in Public Policy”, No. 355, Glasgow 2001.

Maćków, Jerzy (ed.), Autoritarismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa, Wiesbaden 2009.

Maćków, Jerzy, Russian legal Culture, Civil Society, and Chances for Westernization, in: Alexander J. Motyl / Blair A. Ruble / Lilia Shevtsova (ed.), Russia’s Engagement with the West. Transformation and Integration in the Twenty-First Century, New York/London 2004.

Way, Lucan A., Kuchma’s Failed Authoritarianism, in: “Journal of Democracy”, No. 2/2005, pp. 131-145.

Wilson, Andrew, Virtual Politics. Faking Democracy in the Post-Soviet World, New Haven / London 2005.