He Can Dig It

Soil health, climate change and the effect on humans p24

Tribe and Timber

How a UW professor learned from the Yakama Nation p28

Making Waves

UW women’s crew has its own rich history p30

Spin Class

It’s 1988. Welcome to the future of industrial design

Bucking Tradition

Kittitas Valley, home to ranches, orchards and waving fields of Timothy hay, is every bit as bucolic as it was a century ago when, in 1923, the Ellensburg Rodeo first sprang from the gates. The area had long been a meeting place for Columbia Plateau tribes. Local bands of the Yakama relied on the valley for trade, pony racing and other competitions and celebrations. Ranchers first ran their cattle here in the 1850s, bringing roundups, fiestas and local ranch contests, all of which culminated in the town’s first rodeo. Professor Emeritus Mike Allen, ’85, is a founding member of the Ellensburg Rodeo Hall of Fame. While not the first in the state, Ellensburg’s rodeo was the first to gain national significance, he says: “By 1924, it was on the map and became one of the

most important rodeos in the Pacific Northwest.” Today, professional cowboys like Clay Stone, pictured here in 2022, come back to compete every September. But it has never lost that small-town feel, thanks to volunteers and organizers like Rick Cole, ’70, who serves on the rodeo’s board of directors, and former student Davis/Yellowash Washines, a Yakama elder as well as a member of the Native American Advisory Board at the Burke Museum. Tradition has it that the rodeo doesn’t start until several members of the Yakama Nation have ridden their horses down Craig’s Hill and into the arena. “That’s the moment you’ve got to be in the grandstands for,” Allen says. “Then the rodeo can begin.” Photo by Evan Abell/ Yakima Herald-Republic

OF WASHINGTON ELLENSBURG

RODEO

SAILGATING HUSKIES FOOTBALL. FIRST WEDNESDAY CONCERTS. SHOPPING AT U VILLAGE. Not an offer or solicitation to sell real property. Thomas James Homes is a registered trademark of Thomas James Homes, LLC. ©2023 Thomas James Homes. All rights reserved. Brokerage: TJH SEATTLE LLC. License #:2101251. General Contractor: SEA HOME BUILDERS LLC. License #: SEAHOHB806DO Discover the convenience, connectedness, and financial potential of a new TJH cottage-style home near University of Washington. From thoughtfully-designed plans to walkable, near-campus locations, our cottage-style homes offer a smart investment opportunity and one-of-a-kind university lifestyle. Find yours at tjh.com/cottages Southern California | Northern California | Pacific Northwest | Colorado | Arizona tjh.com | @ThomasJamesHomes | (877) 381-4092 Invest in the ultimate UW lifestyle with a new TJH cottage-style home. 2 UW MAGAZINE

At the University of Washington, our students and our community have a rich legacy of striving toward a common goal, and we don’t stop at the finish line. When we all combine our individual passions with a shared purpose, we go further, faster — together.

uw.edu/boundless

For pushing yourself. For pulling together. BE BOUNDLESS.

24 He Can Dig It

UW soil scientist David Montgomery shows how systems in nature and those created by humans affect us and the climate.

By Rachel Gallaher

28 Tribe and Timber

Forestry Professor Tom Hinckley learned from the Yakama Nation as they shared their approach to managing forests.

By Caitlin Klask

30 Making Waves

As the opening of “The Boys in the Boat” movie nears, we honor the dedication, hard work and success of UW women’s crew.

VOLUME 34

NUMBER 3

FALL 2023

ONLINE magazine.uw.edu

Coxwain Marilyn Goo, ’73, holds the trophy for the Lightweight 8 rowing team at the 1972 National Women’s Rowing Championships. �he UW women’s crew had formed just a few years earlier and their resources were so limited they had to buy their own uniforms.

EYE FOR POSITIVES

Author, film photographer, bus driver Nathan Vass, ’09, finds inspiration in the everyday. Meet the Husky behind the lens (and the wheel) at uwmag.online/vass.

FINE JEWELER

From a hobby jeweler to a full-time entrepreneur, Valerie Madison, ’09, champions representation in the fine-jewelry industry. Find out how she got started at uwmag.online/madison.

STORIES OF

We’ve rounded up our stories of UW alumni veterans. Be inspired by their bravery at uwmag.online/veterans.

By Hannelore Sudermann

By Hannelore Sudermann

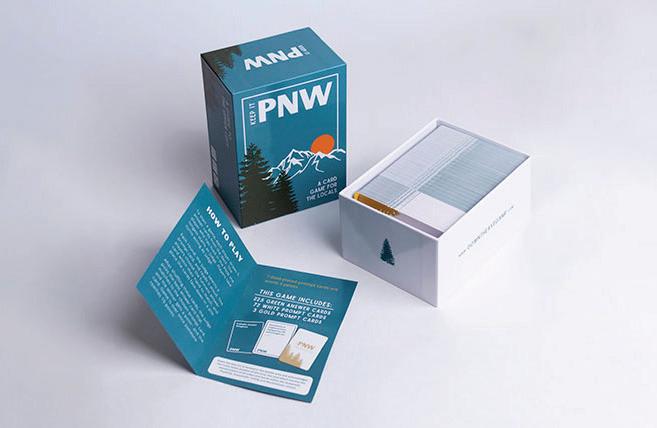

32 Dandy Design

The field of industrial design has grown thanks to the innovative students and faculty in the School of Art + Art History + Design.

By Steve Kaneko

ON THE COVER

The popular Precor 714/718 Low Impact Climber was designed by industrial designer David Smith, ’70, ’72.

4 UW MAGAZINE

6 Campus and Community 8 A Better Building Block 10 Roar of the Crowd THE HUB 12 Smart Tech 13 State of the Art 18 Research 22 Athletics COLUMNS 38 George Counts’ Legacy 39 Sketches 41 Media 50 New UWAA President 53 Tribute 54 In Memory IMPACT 44 Be REAL 46 Philanthropy’s Finest 48 Night Sky UDUB 56 Peace Corps Legend KIM ILINON

FORWARD

SERVICE

COURTESY NANCY NORDHOFF NATHAN VASS

COURTESY MARILYN GOO

IN WITH THE OLD

Husky fans, your retro favorites are back in style! Claim these special-edition Rivalry Low sneakers at adidas.com.

realdawgswearpurple wearpurple real_dawgs

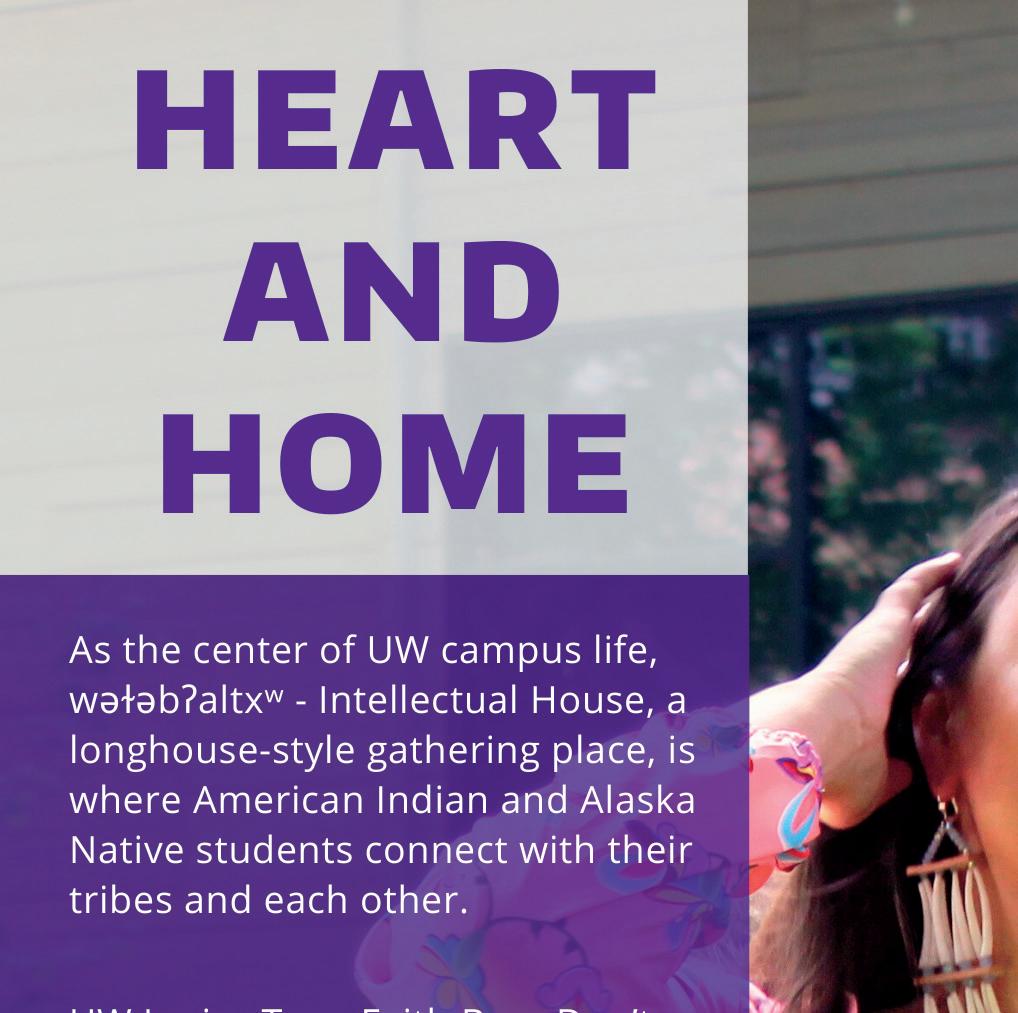

Creating a Campus That Welcomes the Future

By Ana Mari Cauce

When we talk about how the University of Washington can make a meaningful, positive impact in the world—the purest expression of our public mission—we often invoke the notion of our “power to convene.” But what do we mean by this? And how does it shape our role in the communities with which we are engaged?

Serving as a convener means that we can bring diverse stakeholders together in service of shared goals, like leading innovative collaborations that leverage the

strengths of community members, faculty, students and the public and private sectors. But it also means building community through shared experiences that spark joy and passion, like the annual Bothell Block Party sponsored by our UW Bothell campus in partnership with community leaders, and UW Tacoma’s long-standing collaboration with the local YMCA to create a recreation center that serves students and the public. And shared experiences happen when we come together to root for our

student-athletes and by restoring the historic ASUW Shell House—where the Boys in the Boat launched their 1936 Olympic bid—to host community gatherings.

To meet the needs of our community, including our neighbors, alumni, supporters and fans, we are working to create a truly welcoming campus where people live, play, work and learn. On our campus in Seattle, we are creating actual convening spaces to welcome new ideas and voices to our community.

Several years ago, the Seattle City Council approved the UW Seattle Campus Master Plan, a long-range vision that enables us to develop 3 million square feet west of the current campus from the U District to the waterfront, creating what will be known as Portage Bay Crossing. This area will be a mix of gathering spaces, academic and research facilities, affordable housing units and green space. There, students and faculty from disciplines including public health, clean energy, medicine, social work, public policy, the arts and humanities will be able to partner with business, government, nonprofits and the broader community to work on the big challenges we face.

In planning for the future, we know that our city urgently needs more affordable housing. That’s why the UW and the Seattle Housing Authority are developing a mixed-income high-rise of about 240 units west of campus. The building will provide childcare space as well as much-needed housing near the UW and transit options.

In tandem with Portage Bay Crossing, we are also developing a UW Welcome Center in the U District. It will be the outcome of an innovative partnership between the University Book Store, the UW Alumni Association and the University. We envision it as a front door to the UW—a place for new friends to learn about the University and for old friends to gather and connect.

This is all happening at a pivotal time, as we look forward to the release of the “Boys in the Boat” feature film this winter and prepare to join the Big Ten Conference in August 2024. Our vision of creating welcoming new spaces will help us make the most of these extraordinary opportunities. By cultivating an urban landscape in which the UW is a welcoming place for everyone, we will build on our commitment to collaboration and public service. We look forward to seeing you there.

6 UW MAGAZINE OPINION AND

ILLUSTRATION BY ANTHONY RUSSO

THOUGHT FROM THE UW FAMILY

MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT

A Better Building Block

By Jon Marmor

Founders Hall, the spectacular recent addition to the Michael G. Foster School of Business, is much more than a space for learning and community building. Forget for a moment that this year-old, privately funded, 85,000-square-foot facility provides some of the most state-of-the-art classrooms, conference rooms and social spaces on the campus in Seattle. It is the only University building fully constructed of mass timber. This sustainably sourced composite hardwood has the promise of reducing the costs of construction while increasing a building’s sustainability and reducing carbon in the atmosphere.

As the first UW building that meets the University’s Green Building Standards to reduce its carbon emissions by more than 90%, Founders Hall employs cross-laminated timber decking. The new technology means Founders Hall sequesters more than 1,000 tons of carbon.

It is a monument to innovative, lesscostly and healthier structures that could benefit the environment. And it shows how the UW is helping lead the way in making this innovation a regular part of our lives.

The College of Engineering, College

of Built Environments and the College of the Environment are some of the UW units currently exploring the possibilities for mass timber, to great result. Jeffrey Berman, professor of civil and environmental engineering, was the principal investigator on a project testing a 10-story mass-timber building designed to withstand Seattle-area earthquakes. Then there is the College of Built Environments’ Carbon Leadership Forum. The UW team works with architects, designers and industry to measure and reduce the carbon footprint of building materials. They are exploring how mass-timber buildings can have a positive impact on the environment. And a team from the School of Forest Resources developed regionally specific life-cycle assessment models to evaluate the environmental impact of potential cross-laminated timber production in the Olympic Peninsula—a region that lives by timber production.

The National Science Foundation recently awarded a $1 million grant to the UW, the University of Oregon and Oregon State University to explore expanding the use of mass timber. It looks to be a great building block for the future.

STAFF

A publication of the UW Alumni Association and the University of Washington since 1908

PUBLISHER Paul Rucker, ’95, ’02

ASST. VICE PRESIDENT, UWAA MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS Terri Hiroshima

EDITOR Jon Marmor, ’94

MANAGING EDITOR Hannelore Sudermann, ’96

ART DIRECTOR Ken Shafer

DIGITAL EDITOR Caitlin Klask

CONTRIBUTING STAFF Karen Rippel Chilcote, Kerry MacDonald, ’04

UWAA BOARD OF TRUSTEES PUBLICATIONS

COMMITTEE CO-CHAIRS

Chair, Sabrina Taylor, ’13 Vice Chair, Roman Trujillo, ’95

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Rachel Gallaher, Genevieve Haas, Steve Kaneko

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Matt Hagen, April Hong, Anil Kapahi, Kris Ladera, Meryl Schenker, Ron Wurzer

CONTRIBUTING ILLUSTRATORS

Joe Anderson, Olivier Kugler, David Plunkert, Anthony Russo

EDITORIAL OFFICES

Phone 206-543-0540

Email magazine@uw.edu

Fax 206-685-0611

4333 Brooklyn Ave. N.E.

UW Tower 01, Box 359559

Seattle, WA 98195-9559

ADVERTISING

SagaCity Media, Inc.

509 Olive Way, Suite 305, Seattle, WA 98101

Megan Holcombe mholcombe@sagacitymedia.com

703-638-9704

Carol Cummins ccummins@sagacitymedia.com

206-454-3058

Robert Page rpage@sagacitymedia.com

206-979-5821

University of Washington Magazine is published quarterly by the UW Alumni Association and UW for graduates and friends of the UW (ISSN 1047-8604; Canadian Publication Agreement #40845662). Opinions expressed are those of the signed contributors or the editors and do not necessarily represent the UW’s official position. �his magazine does not endorse, directly or by implication, any products or services advertised except those sponsored directly by the UWAA. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to: Station A, PO Box 54, Windsor, ON N9A 6J5 CANADA.

8 UW MAGAZINE

ILLUSTRATION

BY DAVID PLUNKERT

MESSAGE FROM THE EDITOR

Mirabella Seattle is a resident-centered, not-for-profit Pacific Retirement Services community and an equal housing opportunity. According to the data, Seattle is the most well-read city in the country. And, according to our residents, Mirabella is the most well-read senior community in Seattle. Professor? Scholar? Bookworm? You’ve found your place. Call today to schedule a tour. 116 Fairview Ave N • Seattle • 206.337.0443 www.mirabellaseattle.com It was soul mates at first simile. Find Your People in South Lake Union

Professor Frey’s Finest

I was saddened to read of the passing of Professor Charles Frey. I was in Professor Frey’s Shakespeare course in 1994. In a required seminar with 50 students, Professor Frey had the magical ability to transform the room into a creative and intimate space. The encouragement he gave me shaped my writing and teaching. He taught us that the study of literature makes us all better humans.

Alison E. Kreiss, ’97, Marion, Montana

A Sad Loss

Your “Pulling Together” and “Paint Ain’t Free” pieces (Summer 2023) reminded me of one the most famous and tragic rowers in Husky history, John Bracken. John never lost a race, freshman, JV or varsity, in his five-year career. Oddly, he never learned to swim. One day in 1942, while sailing on Lake Washington, he was knocked overboard by a swinging boom and drowned. Sad loss of a marvelous person.

Bill Galbraith, ’44, Fernandina Beach, Florida

Britain’s Glory

Please allow me to correct the record in the article “Pulling Together” (Summer 2023). The author is forgetting that Britain also won a gold medal at the 1936 Games. The great rower and Olympian Jack Beresford and Dick Southwood won the final in the double sculls. The U.S. took the gold in the eights, and Germany took gold in five other boat classes. One final was rowed on Aug. 13, the six other finals on Aug. 14.

Goran Buckhorn

Dr. Copass’ Contribution

In the article about Leonard Cobb (“Back From the Brink,” Summer 2023), I miss the mentioning of Dr. Michael Copass, who was very involved in the creation of MedicOne. Years ago, I volunteered with Dr. Cobb on a MedicOne Foundation project, remembering him telling me how much they all worked together to bring the organization to the highest standard and is recognized in many states. There are books written about their endless efforts. It would be great to remember the rule to recognize all creators or none.

Petra H. Walker, Mercer Island

Corrections

Arreguin’s Greatness

I was at the UW while Alfredo Arreguin (see page 54) was getting both of his degrees. I did not realize that our lives during that tumultuous time had several touchpoints. I too had Michael Spafford as a professor in a humanities class. Later, I was in a Seattle AAUW Spanish conversation group with Spafford’s mother-in-law, who had been the librarian at the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City while I was a student there. While I was student-teaching in my last quarter at the UW, Roberto Maestas taught Spanish, and I was privileged to observe him teaching. Maestas and the rest of us had an interesting spring. On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. A few days later, partly as a reaction to the tumultuous times, an activist who later became a politician led a group of about 100 students into the school. We were under lockdown that day, and the rest of the year there were plain-clothes police officers in the building. Two days before I graduated from the UW, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated. I ate lunch almost every day with Maestas, and you could see and hear his outrage growing, which led to his leadership that resulted in the creation of El Centro de la Raza. I wish I could have afforded to buy one of Arreguin’s paintings, and, as a Spanish teacher, I would have loved to have met him. What a loss his passing is.

Carolyn Edwards on Facebook

Missing Our Joe

Joe Jarzynka (“Small in Stature, Big in Our Memories,” Summer 2023) worked for us after college at UW in our parts department at Rood Nissan-Volvo in Lynnwood. He was a great worker (no surprise) and learned to love his enthusiasm. He was a great UW punt returner and will be sorely missed. Godspeed, Joe.

Marty Rood, ’57, Lake Forest Park, on Twitter

Great People

In response to a long-form UW Magazine Instagram post: “Love that you guys are highlighting stories of the outstanding alumni of the University of Washington … some of the greatest people you’ll find anywhere! Great work @uwalum.”

Ron Hoon, ’79, Mesa, Arizona, on Instagram

Joyce Gibbs was misidentified in our story about the Desert Scholarship Patron Committee in the Summer 2023 issue. The gallery in the School of Art + Art History + Design is the Jacob Lawrence Gallery. The museum is no longer referred to as The Jake.

ADVOCATE A program of the UW Alumni Association Become an advocate today HIGHER ED NEEDS YOUR VOICE UWIMPACT.ORG 10 UW MAGAZINE

JOIN THE CONVERSATION EMAIL YOUR COMMENTS TO: magazine@uw.edu (Letters may be edited for length or clarity.)

ROAR FROM THE CROWD

A FUTURE WHERE YOUR PAYCHECK DOESN’T IMPACT YOUR PREGNANCY.

People who can’t afford or access prenatal care are more likely to suffer pregnancy-related complications.

Healthier communities make healthier people. The University of Washington is leading the way in addressing the interconnected factors that influence how long and how well we live, from poverty and health care to systemic inequities and climate change. In partnership with community organizations, the UW transforms research into concrete actions that improve and save lives across the country — and around the world.

LEARN MORE

uw.edu/populationhealth

Smart Students, Clever Tech

Smartphones and fitness trackers record student behaviors to predict grades

By Hannelore Sudermann

Smartphones are amazing. Besides functioning as telephones, cameras and interactive maps, they can track a person’s exercise, monitor their sleep and discover their habits.

And as a new batch of students steps foot on campus this fall, the device will collect information that can be used to predict their grades.

Over the past few years, hundreds of UW students passively provided data from their smartphones and Fitbit trackers so researchers could study both their health and behavioral outcomes. “We collect information about where the students are, how they are sleeping, what apps they use, where

they go and who they communicate with,” says computer scientist Anind Dey. “With only the data from Week One of the quarter, we can accurately predict what their GPA will be on the 12th week and, in particular, whether the GPA will be above or below the University average.”

Dey, the dean of the Information School and an adjunct professor in the Department of Human-Centered Design and Engineering, works with an interdisciplinary team of students and colleagues. They are exploring ways to identify at-risk students in hopes of helping them navigate the challenges of their first months on campus.

Information collected by the smart

devices can contribute to an understanding of an individual’s mental well-being, substance use and even experiences of discrimination, Dey says. Starting with known scientific findings (for example, how poor sleep affects grades and is linked to substance abuse and mental-health issues) and pairing them with device data, the researchers can compute thousands of statistics to see what patterns emerge.

In addition to collecting data, the researchers survey the students in the study “sometimes monthly, sometimes weekly, sometimes even hourly to understand their grades, their demographics, how they’re feeling, their sense of anxiety and whether they are using illegal or legal substances at that very moment,” Dey says. They use the sensor and survey data to build behavioral images that allow them to describe, detect and predict.

It’s uncanny—and maybe a bit unsettling—just how much information a smartphone can track, Dey says. The accelerometer, for example, collects information about how you’re holding the phone and how you’re moving through space. The smartphone also records data about how often you’re on your phone, and whether you’re being physically or socially active. “Most of that information is thrown away,” Dey says. But there is a tremendous, mostly untapped, opportunity for data collected from the devices around us to help us. Time spent on your phone at night is time spent not studying or sleeping, for example, and will likely result in a lower GPA, Dey says. “Even a fleeting interaction like unlocking your phone can be a window into who you are and what your future might hold.”

Through the data collected—like heart rate and sleep patterns—the devices can also measure stress, Dey says. By collecting and modeling the data now, the team may someday build predictive models to help understand what will happen to a student—whether in the next few minutes or the next few months. “These predictive models can be very powerful, but what excites me the most is that they allow you to avoid a negative outcome through targeted interventions or directly support a positive outcome.”

Dey cautions that using these tools to collect data and make inferences also raises challenges around the users’ privacy. “Despite the challenges that exist with this kind of technology, the opportunities to do good in the world are huge,” he says.

NEWS AND RESEARCH FROM

12 UW MAGAZINE APRIL HONG

With data from smart devices, researchers are exploring ways to identify and help at-risk students.

THE UW

Salish Scene

Imagine a jellyfish as wide as Dubs, with tentacles as long as the bell tower atop Gerberding Hall . The lion’s mane jellyfish, one of the world’s longest creatures, is part of the rich marine life within the Salish Sea, along with two iconic, interdependent endangered species: Southern resident orcas and Chinook Salmon. The Burke Museum exhibit “We Are Puget Sound” aims to inspire its preservation. It runs through Dec. 31. Photo by Drew Collins.

STATE

THE ART CREATURES

OF

OF THE SEA

Happiness is Just One Bus Away

Two graduate students seeking a better transit experience invented an app that puts cities within easy reach

By Genevieve Haas

The OneBusAway icon is at the top of my screen. I can find it the instant I unlock my phone. The app, which uses GPS data to tell transit riders when a bus or train will arrive at any given stop, is an indispensable tool for Seattleites like me who rely on public transportation to get virtually everywhere.

OneBusAway is the brainchild of Brian Ferris, ’06, ’11, and Kari Watkins, ’11, who were pursuing their doctorates at the UW in the mid-aughts, Ferris in computer science and Watkins in civil engineering. Unknown to each other and working in

meet a friend for dinner, I opened OneBusAway and began to strategize. The restaurant was easy to access by bus, and in the transit-dense U District, there were actually three routes that would get me there. The 372 stopped closest to my office, but OneBusAway informed me that I had just missed it, and the next one wouldn’t arrive for 15 minutes. By walking a few blocks west, I could catch the 45, which the app told me was just five minutes away. If I missed that, I’d still have nine minutes to hoof it a few more blocks to catch the 67. I stepped up my pace, ar-

invisible to riders. “I [was able] to improve the utility of the existing tracking data and combine that with a free service that hooked up a telephone number to a textto-speech engine,” Ferris says. “I hacked together all this stuff into a demo where I could call in and enter a bus stop ID [number] and … it would read to you when the bus was coming.”

In those pre-smartphone days, Ferris’ tool connecting ordinary riders to transit data was novel, and as his side project gathered momentum, he started sharing it with colleagues and other transit enthusiasts. Eventually, a friend in the UW’s civil engineering department connected him with Watkins.

As the mother of two young children who needed a way to get around Seattle that minimized bus transfers, Watkins was already interested in a transit-data project of her own. “I wanted there to be a tool where I could literally plug in some type of place I wanted to go, like a park, and get a list of places that were just one bus ride away,” she says. When she met Ferris and they began exploring how to create better access to transit information, Watkins’ coinage of “One Bus Away” took hold.

Ferris and Watkins brought distinct and complementary skills to the project. Ferris knew how to write code and implement it, and Watkins had a deep understanding of riders’ transit behavior and transit agency operations. Soon, they were working with all of the major Puget Sound area transit agencies, which recognized the potential for a tool that would make their services more usable to the public.

However, as doctoral students, Ferris and Watkins weren’t just building a useful consumer application, they were also earning Ph.Ds, and both are quick to credit Alan Borning, now professor emeritus in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, for his mentorship and support not only in realizing OneBusAway, but in guiding their work within an academic framework.

different departments, they nevertheless shared a love of public transit and a desire to make it more usable, accessible and predictable.

They soon found each other and, to the benefit of millions of riders, created OneBusAway. Launched in 2008 and currently operated by the nonprofit Open Transit Software Foundation, the app now serves more than 100,000 riders a day in the Puget Sound region, and millions more worldwide. Transit agencies from New York to Buenos Aires have adopted the opensource code to deploy local versions.

Recently, as I was leaving campus to

riving in time to catch the 45, which—to my delight—pulled up exactly when OneBusAway had predicted.

Such a calculation would have been impossible in 2004, when Ferris came to the UW as a graduate student. He planned to study robotics, but as a frequent publictransit user, he couldn’t help but turn his problem-solving nature to reducing the time he spent waiting for a bus with little to no idea of when it might actually arrive. And so, a side project was born.

Ferris gained access to the existing—if rudimentary—bus-tracking data that was collected by transit agencies but was

Borning served as co-adviser on Ferris’ doctoral thesis and serves on the Open Transit Software Foundation Board of Directors, along with Watkins. From an academic perspective, the project presented a research opportunity to explore how transit behavior could be changed, and to apply the theory of value-sensitive design to this innovative technology, leading to a few unexpected discoveries. “[We learned that people] would walk more … sometimes because OneBusAway showed them a bus that would get them home sooner a few blocks away … or if the bus was going to be a while, they

Before white settlement, the land where the

14 UW MAGAZINE

As a frequent public-transit user, Brian Ferris couldn’t help but turn his problem-solving nature to reducing the time he spent waiting for a bus.

might walk upstream to the next stop.”

Today, Ferris and Watkins continue to improve transportation and urban mobility. Ferris joined Google, where he works on transportation and urban-mobility technology, and Watkins is an associate professor in civil and environmental engineering at the University of California, Davis, specializing in transit planning and behavior. Both say that their time at the UW and the development of OneBusAway did a lot to shape their lives and careers.

“I’m a transit nerd at heart,” Ferris says. OneBusAway “has definitely been one of the most impactful things that I’ve worked on, and I think most people would be lucky

to have anything like that in their lifetime. It has opened up a lot of doors for me career-wise, and it’s why I’m still in the transportation space.”

Since creating OneBusAway, “crazy things have happened to me,” Watkins says. She once met a mother and her teenage son from Seattle while on a wine tour in France. “So we’re chatting, and I tell them I’m a professor and I work in transit. And that I went to the University of Washington. The kid says, ‘Oh, there’s a really great transit app that I use in Seattle, have you heard of it?’ So then it comes out, and this kid is like, ‘Wait, you’re Kari Watkins?!’”

Within the small world of public-transit nerdery, Ferris and Watkins’ achievement as graduate students does confer a certain amount of cachet. But for millions more people who may never know their names, their influence is felt every time someone opens an app that tells them how long until the next bus or train takes them where they want to go.

FROM WASHINGTON TECH AND TRANSPORT

JOE ANDERSON

Seeing the World from a Remote Location

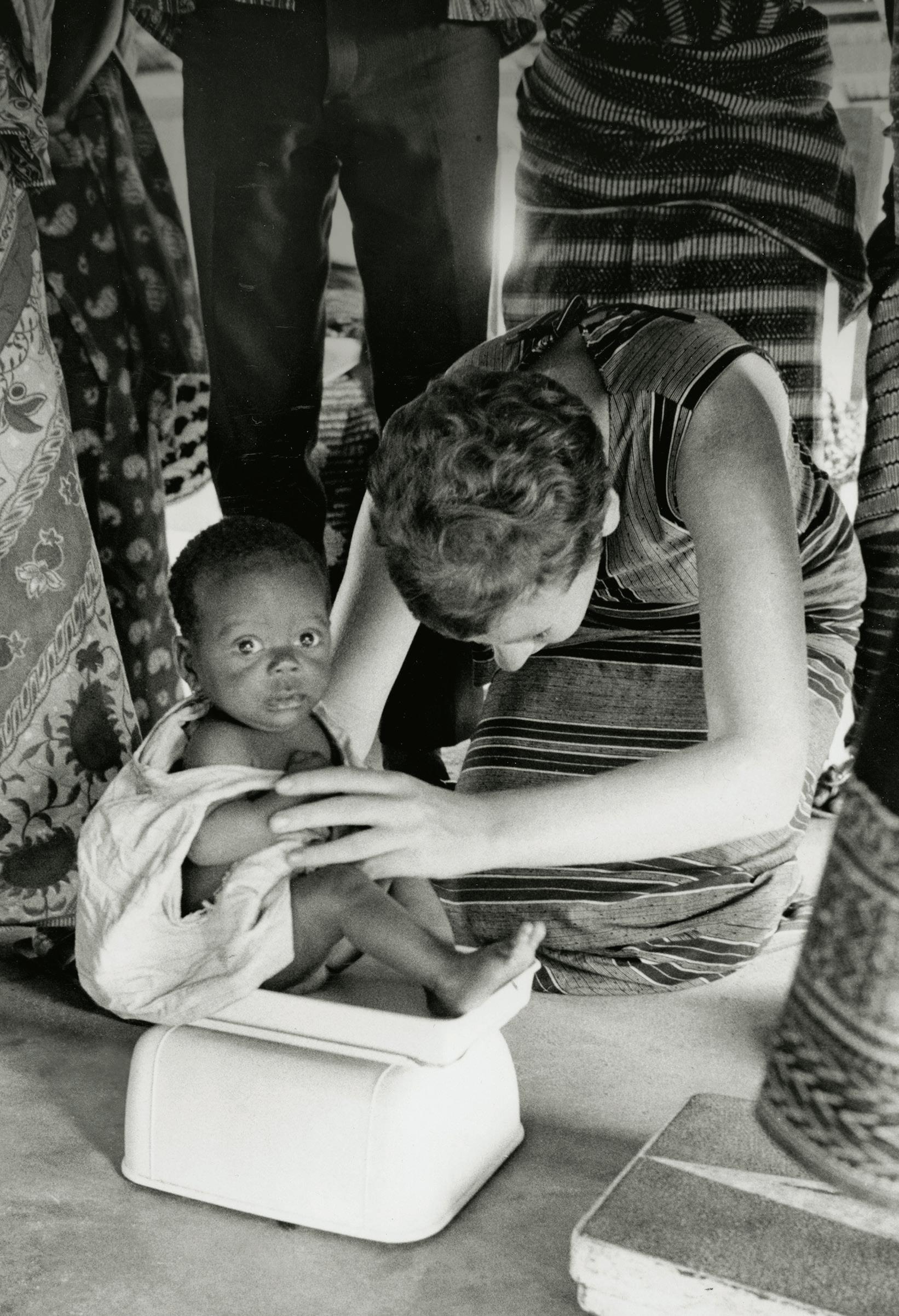

A UW Bothell global public health class visits villages in Guatemala

By Hannelore Sudermann

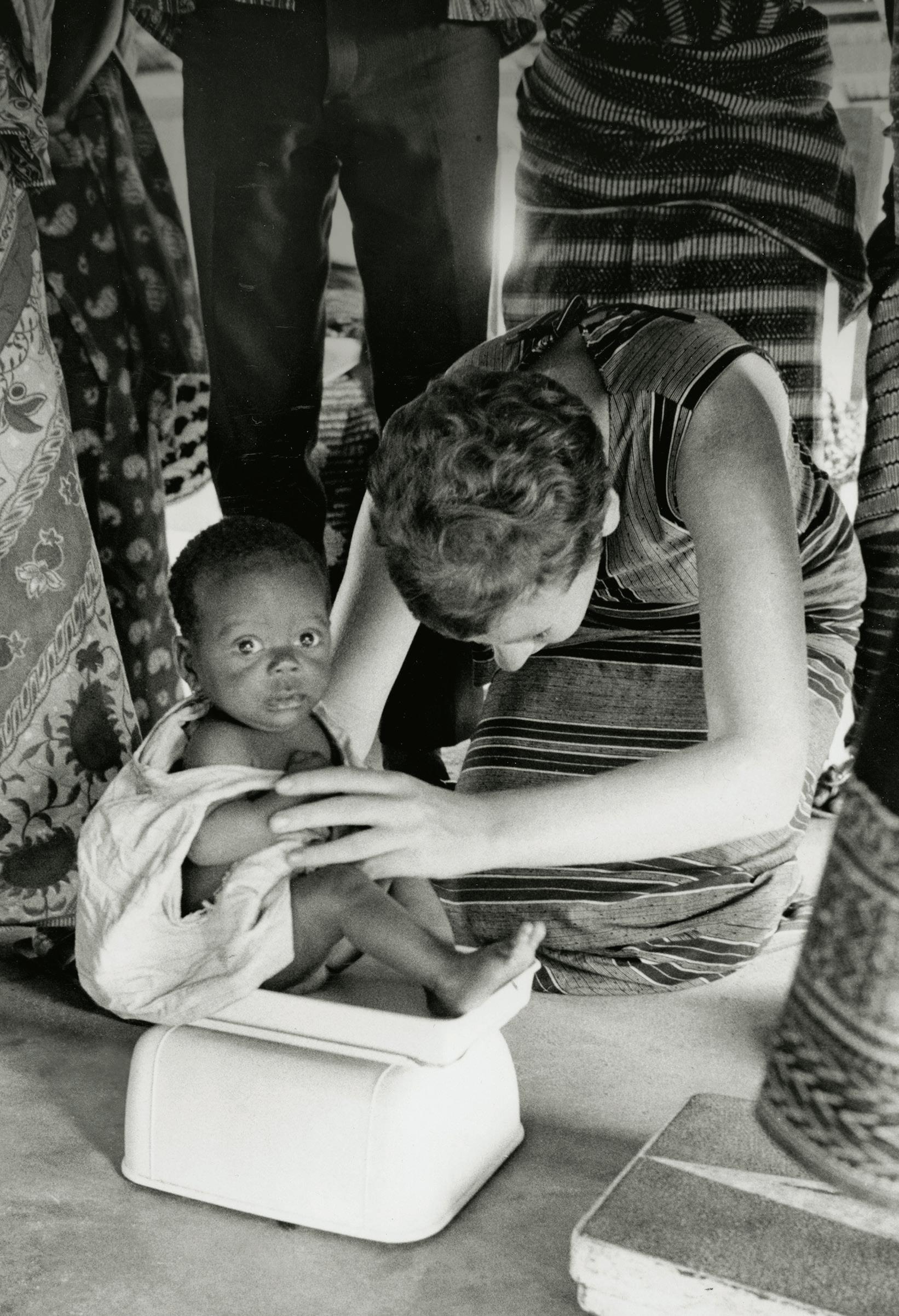

Student Leylani Blanco demonstrates how to take blood pressure measurements to health promoters and lay midwives. She was among 10 undergraduates and six master of nursing students who provided primary care and public health promotion in Guatemala this summer..

Outfitted with boxes of medical supplies and purple T-shirts, students from UW Bothell traveled through Guatemala this summer, popping up clinics in rural Mayan villages and providing medical care and education to nearly 400 Indigenous people. Spending a few weeks in the villages, this contingent from a global public health class gained a precious understanding of rural health care in the developing world.

Students trekked to mountain and coastal villages, places where months could pass between visits from medical professionals. Arriving in trucks and SUVs to find residents lined up and waiting, they toted tubs of supplies into schoolrooms where they

performed screenings and assessments and provided health education.

Guatemala has one of the world’s highest rates of child malnutrition, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund. Part of the UW group’s work centered on malnutrition assessments for babies and toddlers, providing nutritional supplements and health information to families.

“Clinic day is a bustling and dynamic environment, where patients receive personalized attention and care across a range of medical services,” says Leylani Blanco, a postpartum nurse who is completing her bachelor’s degree at UWB. While working with patients, Blanco gained insight into the health-care system of a different country

and how the conditions where people are born, live, work and play affect their well-being.

Mabel Ezeonwu, ’03, ’08, a nurse practitioner and professor of nursing at UW Bothell, developed the class and led the trip. “This intensive hands-on service-learning course is designed to expose students to the policy contexts in which health care is delivered in remote resource-limited environments,” she says. With the community as the classroom, the students are challenged “to view global health-care issues holistically in order to understand how in-country health policies are influenced by local and global determinants.”

At each site, the students are assigned to a team that includes a doctor, nurse practitioner and other nurses. Each station is well-prepared to educate patients about their health conditions, perform medical assessments and administer treatments. The collaboration between different health-care professionals allows for a comprehensive approach to patient care.

The class works with Guatemala Village Health, a Seattle-based nonprofit cofounded by Dr. Jennifer Hoock, who completed her master’s in public health at the UW in 2008. The outreach organization has a mission to improve health in rural villages by providing access to medical care and health education, training health-care workers and implementing public health improvement projects. It brings teams of medical professionals from the U.S. to work with their local nursing team and train local health workers.

Community-based caregivers in southeastern and central Guatemala have long sought resources to train more health workers and midwives, but their local and regional governments haven’t come through. Through Guatemala Village Health, Hoock helped create a training program as well as the volunteer outreach health clinic that the UW students staffed.

“It is really a wonderful match,” says Ezeonwu of working with GVH. “The nonprofit gets engaged and experienced volunteers and the UW team gets community-centered experience and a chance to learn in another part of the world.”

“ This class and trip have been an incredibly meaningful and beautiful experience for me,” says Blanco . “ Collaborating with fellow nurses and individuals from various fields and backgrounds, each with unique values and interests has been eye-opening. Despite our differences, we came together as a team and forged genuine friendships.”

16 UW MAGAZINE

UW BOTHELL

REAL DAWGS WEAR PURPLE

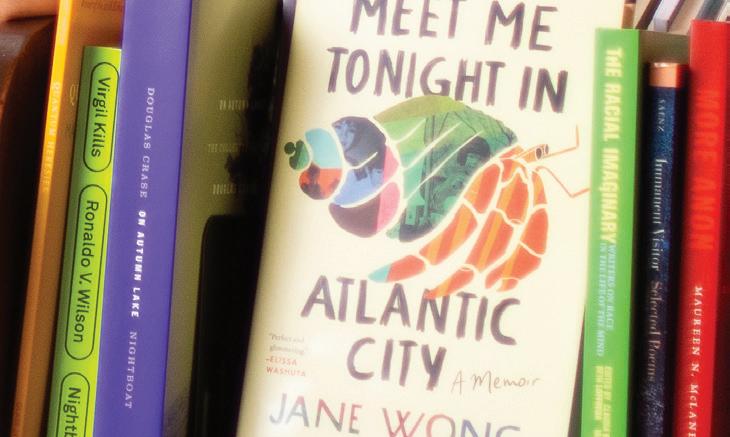

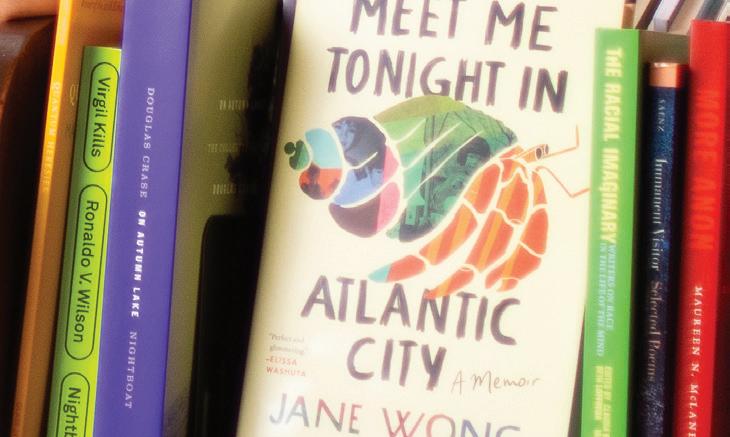

JANE WONG, ’16 POET AND MEMOIRIST

As a child, Jane Wong wrote alternate versions of her library books — an early sign of the writing career to come. In college, Wong was drawn to the freedom in poetry and pursued a Ph.D. in the subject at the UW. The proud Husky penned her debut poem collection, “Overpour,” while writing her dissertation on Asian American poets.

Wong’s award-winning poems weave through time and space, exploring themes of migration, ancestors, resistance and food. Food is also central to “Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City,” Wong’s recent memoir of growing up on the Jersey Shore in her family’s Chinese restaurant, and the aftermath of its loss. Now a creative writing professor as well, Wong credits her time at the UW for fueling her passion for teaching.

Jane Wong browses the shelves at Open Books: A Poem Emporium, a poetry bookstore in Seattle’s Pioneer Square neighborhood.

Jane Wong browses the shelves at Open Books: A Poem Emporium, a poetry bookstore in Seattle’s Pioneer Square neighborhood.

realdawgswearpurple wearpurple real_dawgs

Bioplastics to the Rescue

UW-created materials can degrade in a backyard compost bin

By Jon Marmor

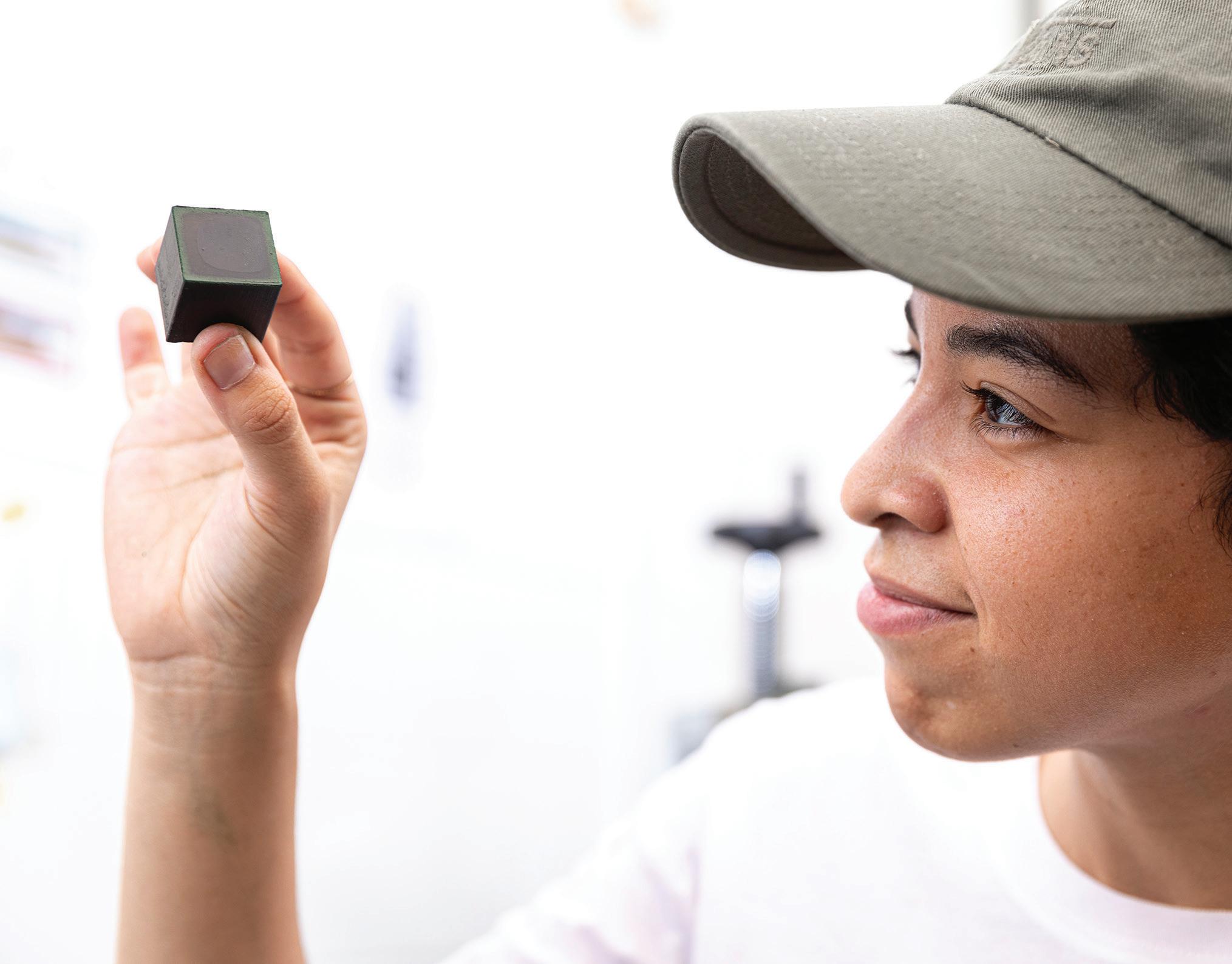

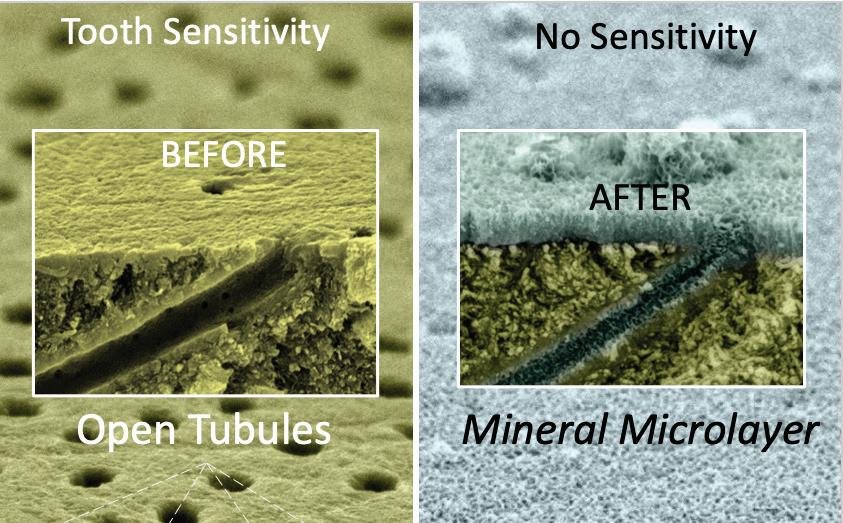

We smile when we remember the great line from the movie “The Graduate,” when Dustin Hoffman’s character is told that the best bet for the future was one word: “plastics.” Well, plastics have completely revolutionized our lives, being durable, inexpensive to make and incredibly stable. But we’ve also become all too aware that disposing of them isn’t easy. They persist in the environment for years. Over time, when they finally do begin to break down, the result isn’t good, either: smaller fragments called microplastics, which can pose significant environmental and health challenges. But leave it to a team of UW researchers to develop new bioplastics that degrade on the same timeline as a banana peel in a backyard compost bin. These innovative materials are created entirely from powdered blue-green cyanobacteria cells,

known as spirulina. The UW team’s bioplastics have mechanical properties that compare to single-use plastics derived from petroleum.

“We were motivated to create bioplastics that are both bio-derived and biodegradable in our backyards, while also being processable, scalable and recyclable,” says Eleftheria Roumeli, assistant professor of materials science and engineering. “The bioplastics we have developed, using only spirulina, not only have a degradation profile similar to organic waste, but also are on average 10 times stronger and stiffer than previously reported spirulina bioplastics. These properties open up new possibilities for the practical application of spirulina-based plastics in various industries, including disposable food packaging or household plastics, such as bottles or trays.”

COLD COMFORT

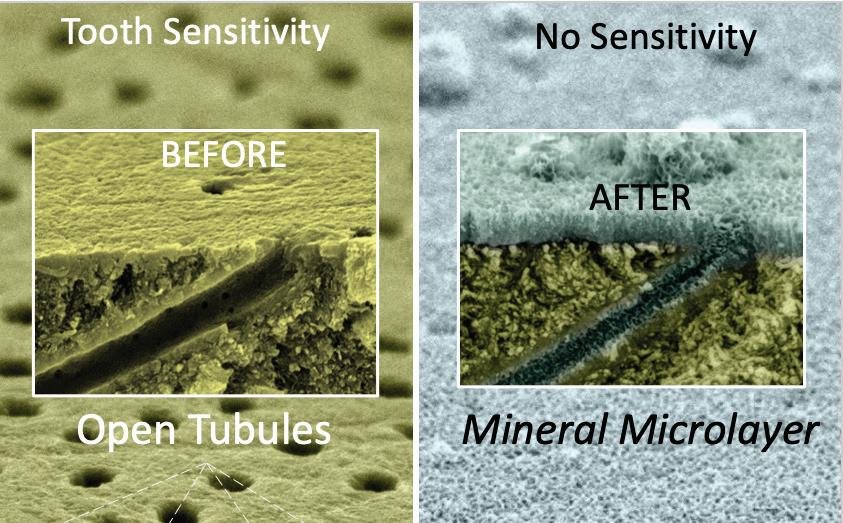

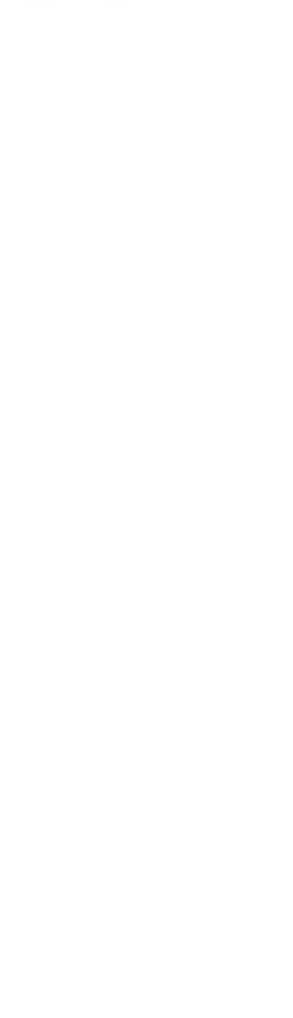

Tooth sensitivity to hot, cold or acidic food is no fun. And until now, dentists couldn’t do anything about it. The UW has come up with a dental lozenge that builds new mineral microlayers that penetrate deep into the tooth to create effective, long-lasting natural protection. The next time you bite into an ice cream cone and don’t wince, be sure to thank Sami Dogan, UW professor of restorative dentistry, and the team of UW materials engineers who devised the solution.

FEVER FIND

If you’ve ever wondered whether you were running a temperature but couldn’t find a thermometer, you aren’t alone. A fever is the most common symptom of COVID-19 and an early sign of many other viral infections. And a temperature check can be crucial for a quick diagnosis and to prevent viral spread. Enter a team of UW researchers, who created an app called FeverPhone, which transforms smartphones into thermometers.

HOT AND HAZARDOUS

Warmer oceans might be pleasant to swim in, but they are wreaking havoc on the lives of seabirds. Using data collected by coastal residents along beaches from Central California to Alaska, new UW research has confirmed that persistent marine heat waves lead to massive seabird die-offs months later. “This type of massive die-off can be compared to a catastrophic storm,” says lead author Timothy Jones, a UW research scientist in aquatic and fishery sciences.

RESEARCH COURTESY MEHMET SARIKAYA, UW SCHOOL OF DENTISTRY DENNIS WISE 18 UW MAGAZINE

Mallory Parker, a UW materials science and engineering doctoral student, holds a bioplastic cube made from spirulina.

MARK STONE ALEUT COMMUNITY OF ST. PAUL ISLAND

ECOSYSTEM CONSERVATION OFFICE

Meet the Nation’s New Top Infectious Disease Specialist

Dr. Jeanne Marrazzo succeeds Anthony Fauci

By Jon Marmor

Her mom was a nurse and her role model. That’s why Jeanne Marrazzo decided to go into medicine. After medical school in Philadelphia, she came to the University of Washington, where she earned a master’s degree in public health, and had a residency and a fellowship. After a successful career in academic medicine—including two decades on the UW faculty—she has become the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, succeeding Anthony Fauci, who retired after nearly five decades in December.

Marrazzo frequently appeared on television as an expert during the height of the COVID pandemic. She also made an impact during her time as a professor on the UW faculty from 1996 to 2015.

“She finds these ways to encourage and push and foster growth and development in people,” Jennifer Balkus, an epidemiologist with Public Health—Seattle & King County, told NPR recently. A former colleague from the University of Pittsburgh described Marrazzo as “an exquisite clinician and an exquisite teacher.”

Marrazzo will head an agency with a $6.3 billion budget that supports research to advance the understanding, diagnosis and treatment of infectious, immunologic and allergic diseases. Marrazzo is an expert in HIV and sexually transmitted diseases and is known for building relationships between basic and clinical scientists to find new methods for preventing and managing common diseases.

FALL 2023 19

UAB / LEXI COON

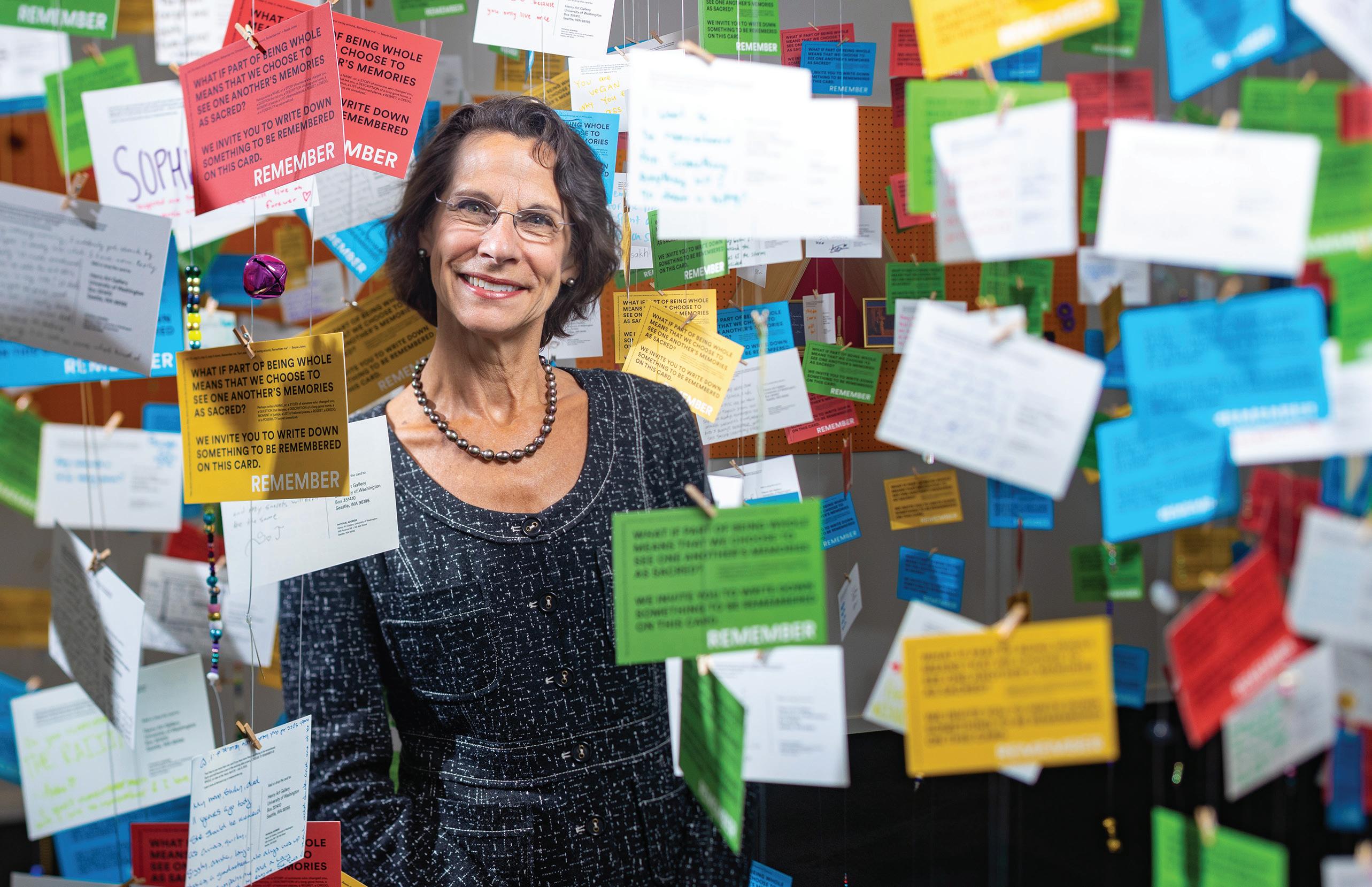

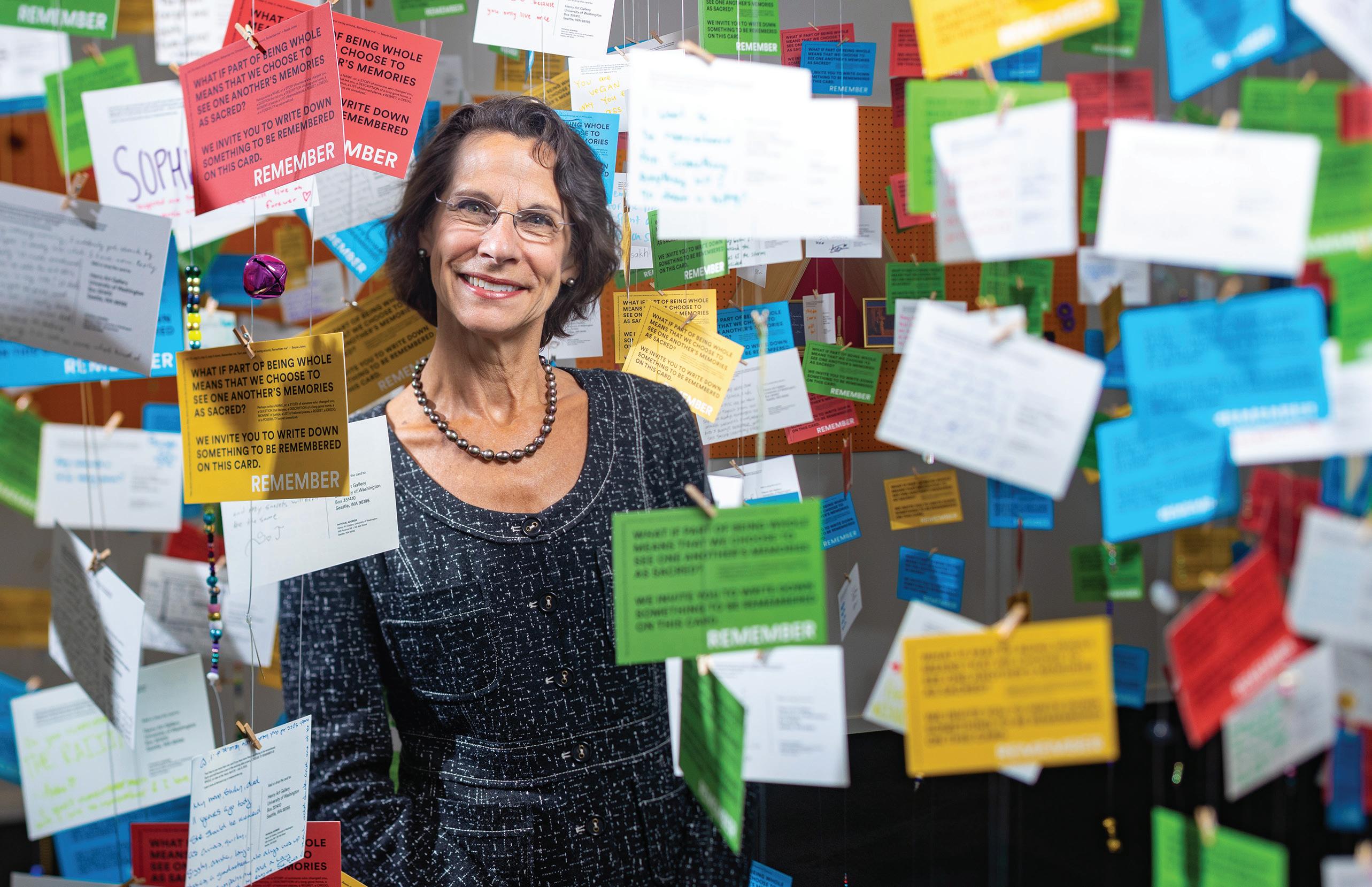

The Magic of Museums

Treasures and community await, says the Henry’s recently retired director

By Hannelore Sudermann

If there’s anything to know about art museums, says Sylvia Wolf, it’s that they’re good for us. They improve our sense of well-being, stimulate and inspire us, and strengthen our communities. The research backs it up, adds Wolf, who recently retired after 15 years as director of the Henry Art Gallery, Washington’s original art museum.

This summer, as Wolf packed up her office, the Henry was buzzing. On the floor above, MFA students were putting finishing touches on their thesis exhibitions. A story below, curation in action was on view in the largest exhibit space.

During her time as director of the UW’s fine arts museum, she oversaw more than 160 exhibits and an evolution of the Henry’s

nearly century-old mission of highlighting contemporary art. She shepherded the care and curation of the collection of more than 28,000 objects. Wolf took some time in her final hours on the job to offer thoughts about how crucial museums are for healthy, vibrant communities and how they’re easier to access than we might think.

Whether they are focused on history, art or artifact, museums do a wonderful job of connecting visitors to the humanities. Nonetheless, they are too often taken for granted and lose out in an ever-increasing whirl of distractions, Wolf says.

According to the American Association of Museums, more people visit museums, science centers, historic sites or aquariums than attend professional sporting events.

Yet art museum visits have declined over the past two decades. A recent survey by the National Endowment of the Arts found that only about 25% of adults visit a single museum in a year. That, Wolf says, is not nearly enough.

And now with so many demands for our attention, we are even less likely to devote an afternoon to wandering through a gallery, she says. Her advice is simple: You don’t need to dedicate a day—or even a couple of hours. You just need to step inside.

At the Henry, visitors can always find something new—whether it’s a single painting or a multi-room sculptural display. This fall, the exhibits include landscape photography of the American West, a trio of videos exploring the writing and rewriting of history, and sculptures focused on texture and touch. That’s in addition to talks, happenings and lectures that are built around the exhibits.

It is so easy to just swing through for 10 or 15 minutes, Wolf says. “Things here are changing all the time. Come often and come with an open mind. You can always expect the unexpected at the Henry.”

20 UW MAGAZINE

�he Henry Art Gallery, a division of the College of Arts & Sciences, features contemporary art and ideas, says Wolf, who stepped down this summer.

MATT HAGEN

UW Converge Returns to Asia

By Isaiah Brookshire

By Isaiah Brookshire

On a tropical morning in early August, more than 200 people gathered for the UW Converge summit in Jakarta, Indonesia. The audience was composed of UW alumni, Husky supporters and members of the public who were eager to gain expert knowledge and connect with one another.

The annual UW Converge event series has long been the place where the UW’s international alumni and friends gather to learn, network across borders and celebrate Husky Spirit. Since the inaugural Shanghai event in 2015, it has traveled across Asia.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic put a pause on those travels. After two virtual years and a homecoming event in Seattle, it finally returned to Asia for UW Converge Jakarta 2023.

The summit kicked o with a keynote from UW President Ana Mari Cauce, delivered from Seattle. She welcomed the audience and spoke about the positive

impacts the UW is creating through the University’s deep global connections. “Examples are everywhere across the world and throughout Asia,” she said. Among the projects highlighted by Cauce were the UW’s Global Innovation Exchange (GIX), which works closely with industry to push the boundaries of innovation, and the Ocean Nexus Center, which seeks to transform ocean governance for the benefit of everyone. She added that “universities like the University of Washington are especially well-suited to these endeavors, because innovation and discovery go hand in hand with exploring the ethical and human impact of our scientific advances.”

These advances and impacts were central to the theme of this year’s summit. It examined groundbreaking innovations in the world of finance, business and technology, but also looked closely at the impact these breakthroughs have on people. Sessions explored topics ranging from how to navigate investment in an uncertain world and the potential for upheaval posed by artificial intelligence to building personal resilience during times of rapid change.

The sessions o ered guests at the summit the chance to hear from leading experts at the UW and from the Husky alumni community. Campus leaders included Denzil Suite, vice president for student life; Ali Mokdad, chief strategy o cer for population health; and Frank Hodge, dean of the Foster

School of Business. There was a large contingent of alumni speakers such as Jerry Ng, ’86, the founder and chairman of Bank Jago, an institution leading a banking revolution in Indonesia, and Alvin Graylin, ’93, the president of HTC China. A number of dignitaries also spoke, including several ministers from the Indonesian government and the US ambassador to Indonesia, Sung Kim.

tingent of alumni speakers such as Jerry Jago, an institution leading a banking rev’93, the president of HTC China. A number and the US ambassador to Indonesia, Sung Kim.

For many, the summit was the highlight of this year’s gathering, but it wasn’t all immersive learning. Celebration and connection are also at the heart of the UW Converge experience. A tour of Jakarta o ered an opportunity to explore the rich culture and history of Indonesia. A gala following the summit added plenty of fun and spectacle to the day. Guests were treated to Indonesian hospitality at its best, enjoying fine dining and traditional performances of dance and music. After Jakarta, an optional extension to Bali o ered more opportunities to explore and a program that examined the future of philanthropy at the UW.

o ered an opportunity to explore the rich

The conclusion of another exciting UW Converge event was a reminder of the strength of the University’s global community of Huskies. With nine established alumni chapters and more than 25,000 alumni and friends around the world, there are Huskies in every corner of the globe making a positive impact.

UW Converge Jakarta was a perfect example of that impact. The event would not have been possible without the dedicated efforts of the Indonesia alumni chapter under the leadership of chapter president Aldrin Tando, ‘91. Their outstanding work brought together an amazing group of speakers for an event that sets a high bar for future hosts.

While the next UW Converge location has not been announced, its legacy of providing unrivaled access and connection to all Huskies who identify as part of the UW’s international community will continue.

To stay informed about future UW Converge events, visit our website and sign up for email updates.

uwalum.com/converge

FALL 2023 21

The premier gathering of the UW’s global community stepped back onto the world stage in Indonesia

Left, summit attendees in Jakarta gather for a group photo. Above, enjoying lunch during the Bali extension.

GIGI DO

Content provided by UW International Advancement

WIRA PHOTOGRAPHY

Sand Storm

Coach Derek Olson has built a fast-rising beach volleyball program in a short time

IN JUST TWO SEASONS, head coach Derek Olson has taken the Husky beach volleyball program to new heights. In 2023, the Huskies were ranked No. 12 in the nation, they had their first 20-win season, and seniors Chloe Loreen and Natalie Robinson became the first Huskies ever named AVCA Beach Volleyball Americans. The former beach volleyball touring pro has set his sights even higher. Interview by Jon Marmor

How did you get interested in volleyball?

I grew up in Eugene with a dad who played and coached volleyball. I was that annoying kid who interrupted his practices.

How did you get involved with beach volleyball?

What’s it like being the coach at UW?

Very few schools know how to balance academics and athletics to give student-athletes the best possible experience. Washington really supports its student-athletes. And the sport itself is exploding. One of the challenges in recruiting and playing, of course, is the weather. It will take patience and consistency to make beach volleyball more prominent at the UW, it won’t happen overnight. And it will take a lot of hard work. We need to create a strong culture for support.

Where does the team play its matches?

After guiding the Huskies to their first 20-win season last year, Coach Derek Olson doesn’t want the UW to take a back seat to anyone.

I started playing at 19 on an indoor club team in Oregon. But I knew that as soon as I graduated, I was heading south to San Diego for the lifestyle, the sunshine and the challenges of having to be an all-around athlete in a physically demanding sport.

What was it like playing professionally?

Surreal. Really stressful, really rewarding, but I got to visit a lot of places around the world.

How did you become a coach?

I started coaching high school athletes and found myself focusing more on developing them than my own game. That’s when it dawned on me that coaching was becoming my passion.

You coached at Cal and you coached the Moroccan National �eam. �ell us about it.

Morocco was quite the experience—a five-week stint leading up to the most important tournament of the year. It was the team’s shot to qualify for the Olympics.

Alki Beach. And we practice at Golden Gardens and sometimes on two courts on campus. There is a home-court advantage in beach volleyball, mainly depending on the different sand depths and the wind. Arizona State has deep sand. At Alki, the sand is shallow, and the weather is all over the place. But we draw big crowds if it isn’t raining or hailing.

Indoor volleyball,

beach volleyball. What’s the difference?

On the beach, players need all of the skills. Indoors, players have very specific skills for their roles. Middle blockers, for instance, might have a real challenge switching to beach ball. And it can take a while for a pair in beach ball to work great together.

What’s the outlook for next season?

We have 11 new student-athletes. We do return a couple of starters, but we have many new freshmen. In the first two years, we recruited a lot of transfer students but now we were able to bring in freshmen so we can really build the program. The Pac-12 is stronger than ever and is the toughest conference in the country. (Note: �his interview took place before it was announced that the Huskies would be joining the Big �en in 2024.)

ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS (2) 22 UW MAGAZINE

A New Day Dawns

UW’s move to the Big Ten brings stability and more national exposure

By Jon Marmor

It was bright and sunny the first Friday of August. Maybe it was a sign from above that the University of Washington’s monumental decision that day—leaving the Pac-12 Conference to join the Big Ten beginning in 2024—meant blue skies were ahead for the Huskies.

The decision made headlines for days. After all, the Huskies (who were joined in moving to the Big Ten by the University of Oregon) had been a founding member of what became the Pac-12 more than 108 years ago. But as the college sports landscape has evolved dramatically over the past couple of years, it became clear the Pac-12 fundamentally had changed to the point where it could not meet the UW’s needs.

“The Big Ten is a thriving conference with strong athletic and academic tradi-

tions and we are excited and confident about competing at the highest level on a national stage,” said UW President Ana Mari Cauce. “My top priority must be to do what is best for our student-athletes and our University, and this move will help ensure a strong future for our athletics program.”

The move by the UW and Oregon to the now 18-member Big Ten conference means there will be four former Pac-12 institutions in the Midwest-based league. Last year, USC and UCLA were the first Pac-12 schools to announce that they were making the move. The UW decided to join the Big Ten because that conference offers a more robust and stable media rights deal as well as the opportunity to compete on a national stage.

“We are proud of our rich history with the Pac-12 and for more than a year, have worked hard to find a viable path that

would keep it together,” Cauce explained. “I have tremendous admiration and respect for my Pac-12 colleagues. Ultimately, however, the opportunities and stability offered by the Big Ten are unmatched. Even with this move, we remain committed to the Apple Cup and competing with WSU across all of our sports.”

As of this writing, the Pac-12’s future is uncertain. In addition to Washington and Oregon leaving to join USC and UCLA in the Big Ten, four other Pac-12 schools (Arizona, Arizona State, Colorado and Utah) opted to join the Big-12 Conference.

The UW was one of four founding members of what started in December 1915 as the Pacific Coast Conference, which over the years grew to become the Pac-12. Joining the Big Ten means the UW will be a member of the Big Ten’s Academic Alliance. “Our dean of the College of Arts & Sciences (Diana Harris), who participated in it in one of her previous jobs, told me what a great network that is,” Cauce explained.

Added head football coach Kalen DeBoer: “The clarity associated with a stable home [in the Big Ten] really helps. I know that our guys are excited about the future.”

FALL 2023 23 UW+YOU GEAR UP FOR FALL WITH UNIVERSITY BOOK STOR E ubookstoreseattle ubookstoresea ubookstore.com

�ight end Jack Westover hurdles a defender in the Huskies’ 27-20 Alamo Bowl victory over �exas in a matchup of two high-profile programs.

24 UW MAGAZINE

HE CAN DIG IT

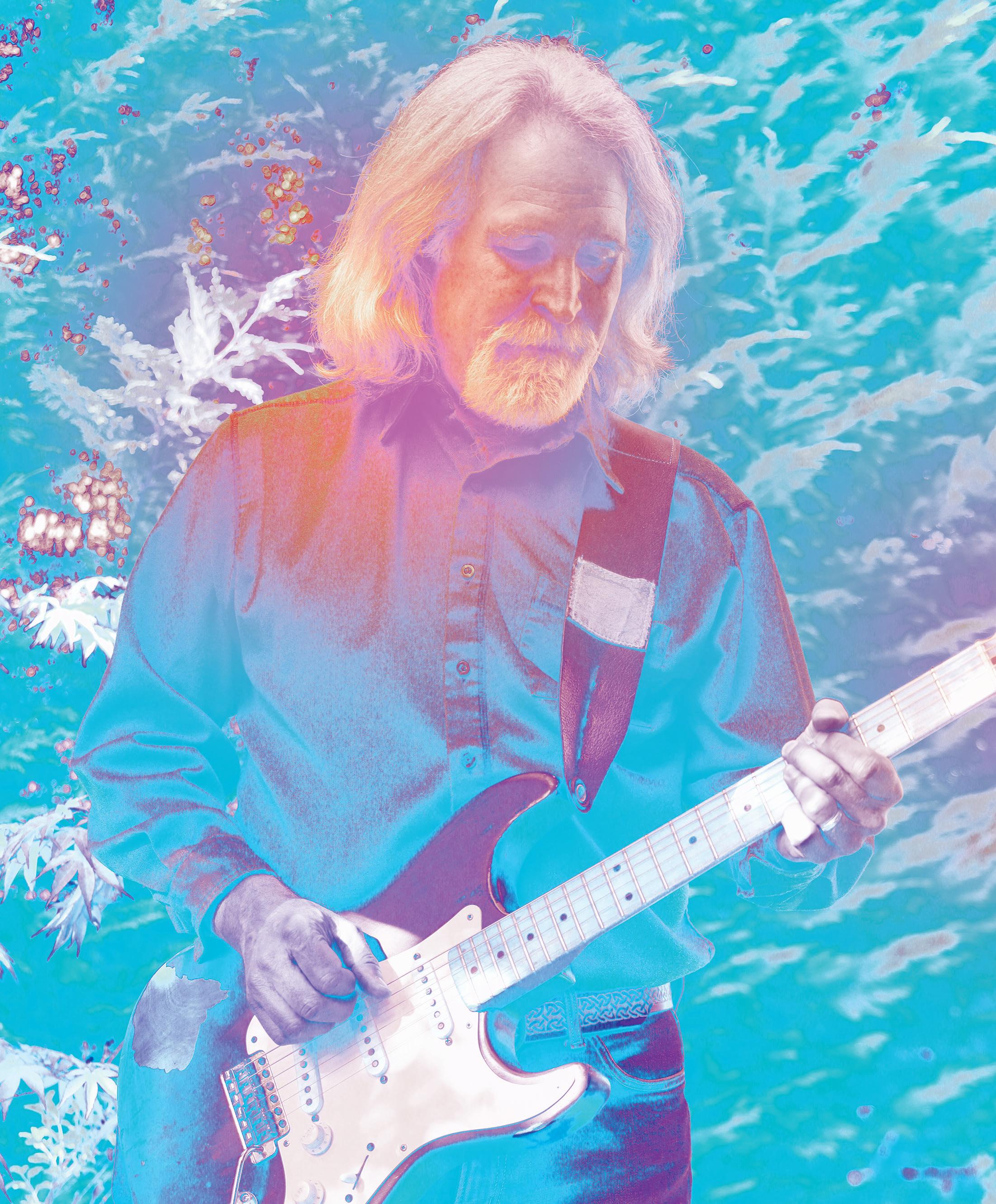

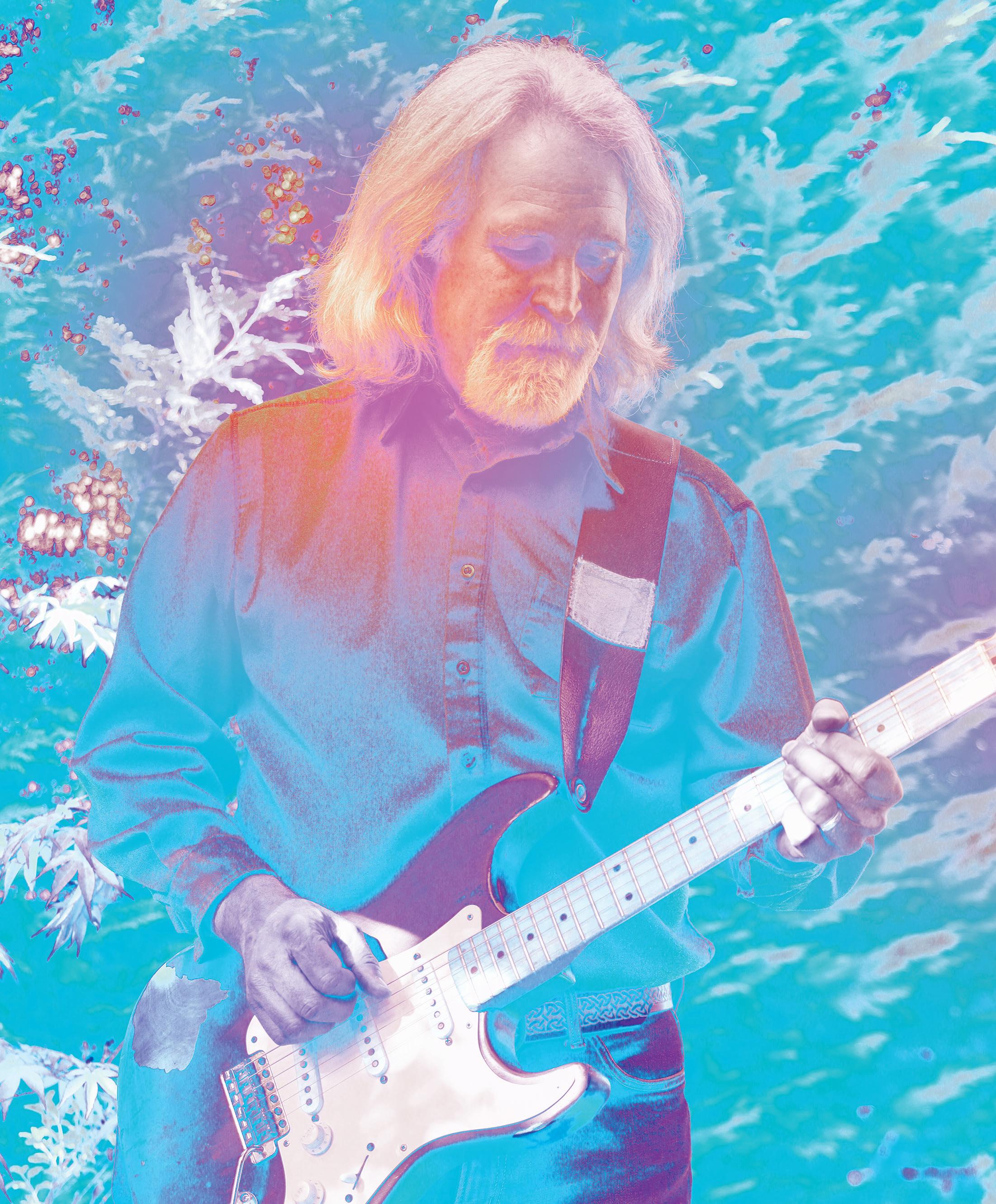

The Rock-Obsessed Rocker

With a MacArthur “genius grant,” a handful of popular science books, and six albums with the local band Big Dirt under his belt, geology professor David R. Montgomery brings balance to his life, and big ideas to the masses

BY RACHEL GALLAHER PHOTO BY ANIL KAPAHI

There’s a popular saying, repeated over dinner tables and latenight snack sessions, that humans are what they eat. Often uttered in jest, the ubiquitous idiom evolved from a line in the 1826 book by French lawyer, politician and noted epicure Anthelme BrillatSavarin that stated: “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.” If perhaps a bit reductive, it’s not altogether wrong. But when I pose the idea to award-winning author and University of Washington geomorphology professor David Montgomery, he pauses for a moment before declaring: “Actually, it turns out that it’s what your food ate that you’re made of.” Montgomery has done the research. Collected in his book, “What Your Food Ate: How to Restore Our Land and Reclaim

{

}

FALL 2023 25

Our Health”—released in 2022 by W.W. Norton & Company and co-written by biologist and environmental planner Anne Biklé (who happens to be Montgomery’s wife)—the findings look at ways in which soil-rebuilding practices affect food growth and in turn, our health. The couple’s second book (the first was 2015’s “The Hidden Half of Nature: The Microbial Roots of Life and Health”), “What Your Food Ate,” builds on the idea that there are relationships between systems in nature, systems created by humans and systems within the human body.

Montgomery isn’t a farmer, but he’s intimately acquainted with how humans grow food. Over his three-decade career, he has traveled the globe from equatorial Africa and Central America to locales closer to home, including the Dakotas, Pennsylvania and Ohio to study methods of farming from subsistence to conventional. Peel back the academic layers, and it makes sense. As a geomorphologist, Montgomery looks at the processes that shape the Earth’s surface and how those processes affect geological systems—and human societies.

“When I got my MacArthur, that’s one of the questions everyone asked,” Montgomery replies when I ask what a geomorphologist actually does. (In 2008, Montgomery received a prestigious MacArthur Fellowship—known as the “Genius Grant.” It came with an unrestricted $500,000 prize meted out over five years). “I’m a geologist who studies what shapes the surface of the Earth. For my academic career, I’ve focused on things like what controls the height of mountain ranges, what makes rivers so bendy and why do fish care about that?”

you’re studying shapes in topography.”

Since Montgomery’s father taught marketing at Stanford University, he grew up familiar with the rigors of academia. In 1979, Montgomery enrolled at Stanford to pursue a biology degree. But after two years, he felt disenchanted with the intense competition and the cut-throat nature of his peers.

“There were only two of us in a class of 400 who didn’t want to become medical doctors,” he recalls. “I burned out— students were sabotaging each other’s experiments in the lab to try and come out on top, and that wasn’t the kind of environment I wanted to be in. So I ended up taking a year off, moving to Australia and working in a series of mines.”

would

take a pessi- mistic outlook on the world,

Montgomery is laid-back and easy to talk to, even if you don’t have an advanced science degree. It’s not hard to imagine him in a classroom explaining complex ideas in a straightforward and engaging way. His late-career rocker look— flowing, shoulder-length hair and a salt-and-pepper beard—suits his other passion: He’s the guitarist, singer and songwriter in a local band, Big Dirt, which released its sixth album, “Trip Around the Sun,” earlier this year. Playing local and regional gigs for two decades, Big Dirt comprises a rotating group of musicians, including several UW faculty members. Their sound is a hybrid of folk, pop, rock and psychedelia wrapped in a feel-good, makeyou-want-to-get-up-and-dance veneer.

“In college, geology was my backup plan if my band didn’t make it big,” Montgomery says. Although he never played soldout stadiums or headed off on world tours (for music, that is), the rock-obsessed rocker found a balance between his academic and artistic lives—and has written a handful of popular science books along the way (three of which have won Washington State Book Awards in the General Nonfiction category).

“I first met David when I was a grad student at UW and he was a new faculty member,” says Eric Steig, ’92, ’96, a glaciologist and isotope geochemist who is also the chair of the UW’s Department of Earth and Space Sciences, where Montgomery works. “I remember thinking that he looked like a young Jerry Garcia. We used to play music together. I knew he was a bit of a genius from Day One.”

Before the music and the MacArthur, there were maps. Growing up in California, Montgomery spent time hiking in the Sierra Nevada mountain range with his Boy Scout troop, sharpening his map-reading skills and contemplating landforms and how they came to be.

“My love of maps and landscapes is probably the root of what got me into geomorphology,” Montgomery says. “I really liked maps, and I was always the navigator on family trips. I could easily relate to things spatially, which is a good skill to have if

easy

Before leaving the U.S., Montgomery took an intro-level geology class that would change the course of his academic career. “We went on field trips out in nature and cooperated with other students on homework,” he says. “The class was about learning things, not beating each other out. It showed me how I like to approach research problems, and I’ve mostly worked collaboratively since then.”

After a year in Australia, which he describes as both informative and fun, Montgomery returned to California determined to pursue a career in geology. But he quickly learned that there were limited job opportunities in the field for someone who has only taken one class on the subject. “It was a very motivating moment for me to go back to school,” he says.

In 1984, Montgomery graduated with a B.S. in geology from Stanford and started a job with a geotechnical engineering firm specializing in investigating the causes of landslides in Northern California. “I was the entry-level geological grunt who would go out and see what was happening at a site,” he says. “I learned a lot at that job, but after two years, it was clear that if I wanted to advance, I would have to go to grad school.”

Montgomery enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1985 with the intent of earning a master’s degree, but about a year and a half into the program, he decided to go for his doctorate. After writing a thesis about the problem of where stream channels start (a stream channel is essentially the path for water and sediment flowing within the stream banks), Montgomery was awarded his Ph.D. in geomorphology in 1991.

Later that year, Montgomery received a two-year appointment from the UW via a grant from the state—four years earlier, Washington had released the Timber/Fish/Wildlife Agreement: a document that “provides the framework, procedures and requirements for successfully managing our state’s forests so as to meet the needs of a viable timber industry and at the same time

26 UW MAGAZINE

It

be

to

provide protection for our public resources; fish, wildlife and water, as well as the cultural/archeological resources of Indian tribes within our state.”

In his role at the UW, Montgomery studied the effects of various forestry practices on streams and the salmon populations migrating through them—as well as the overall issue of diminishing salmon populations. In 1999, three years after receiving tenure, Montgomery was appointed to Washington state’s independent science panel on salmon recovery. Gary Locke, the governor at the time, assembled the panel to look into the health of the area’s salmon populations. Montgomery’s resulting work led to the 2004 publication of “King of Fish: The Thousand-Year Run of Salmon.” The book looks at natural and human forces that shape the rivers and mountains of the Pacific Northwest and how those forces have affected the evolution and near-extinction of regional salmon populations.

Montgomery laid out four arguments why salmon populations were drastically declining: overharvesting, habitat loss, migration blockage by man-made dams and the increase of fish hatcheries. The book, while popular, ruffled feathers across several sectors— political, economic and civic. As a result, Montgomery lost his state funding, but he stands behind his findings. “Unless you’re taking steps to address these four issues, you’re just managing the decline, not turning it around,” he says. “Sadly, ‘King of Fish’ is as relevant today as it was 20 years ago.”

After “King of Fish” was published, Montgomery realized that “I wasn’t going to be getting a renewal on my funding, so I asked myself, ‘OK, what else am I going to work on?’” That something else turned out to be his next book. Published in 2007, “Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations” explores the idea that humans are—and have long been—using up Earth’s soil and that history has seen many societal collapses created by the compound effects of erosion. It was Montgomery’s second book to win the Washington State Book Award. In 2008, he won the MacArthur, which he credits as giving him “the freedom to write books.”

Montgomery has found a niche for himself in the popular science field. His writing is open, accessible and funny at times, and he excels at explaining problems—and connecting dots—in an easy-to-understand manner. Whether describing the complexities of microbial biomass in soil or talking about the history of salmon in the Northwest, the narratives push us to grapple with issues they might otherwise be unaware of but in a way that makes us care—or at least think more deeply.

“David is one of the most creative thinkers I’ve ever met,” his colleague Steig says. “This comes across in his scientific work, in his popular books and in his teaching. His students rave about his classes.”

In 1997, Montgomery and Biklé bought a house in North Seattle, intending to grow a large garden.

“I was the chief gardener,” says Biklé, who studied biology and natural history during her undergrad years. “When we set about building this garden, neither one of us thought to look too much into the soil to see if it was good or bad.” But when Biklé and Montgomery started digging, they discovered a layer of variously sized rocks packed in hard clay—glacial till. “Our soil was like a lot of soil in the Seattle area, full of these weird jumbles of rocks that make it hard to garden,” Biklé says.

neighbors’ yards, coffee grounds from the local café, and the famed Zoo Doo (composted manure from grazing animals at the Woodland Park Zoo). She mixed everything together and layered it on top of the garden beds. She also created a homemade concoction called soil soup, which amounted to trillions of cultured microbes to improve soil fertility.

By the second summer, mushrooms, beetles and other insects appeared in the garden. Fat earthworms wriggled around between the roots of some of the plants, and eventually insect pollinators, then birds, arrived.

According to Montgomery, it took nearly half a decade for Biklé to restore the soil in their yard—a feat so impressive that three years into the project, the organizers of a North Seattle garden tour asked to include their house. Aside from healthy soil and a verdant garden, the project sparked the idea for the couple’s first book: “The Hidden Half of Nature: The Microbial Roots of Life and Health,” which hit shelves in 2016.

“I’ve had a lot of people say, ‘You guys are crazy!’” Biklé says when asked about the challenges of working and living together. “But we never said, ‘Hey, we should write a book together.’ We started talking about these ideas in 2012, and honestly, it just sort of happened.”

Those ideas, which focus on communities of beneficial microbes (bacteria, fungi, viruses, etc.) in soil and humans were on full display as Biklé transformed her garden. When she was diagnosed with cervical cancer part way through writing “The Hidden Half of Nature,” it led her to ask questions about sources of health. Part of the answer emerged from finding that the microbiomes perform similar functions in soil and our digestive systems—and may hold the key to improving both human health and soil health.

“Geology and biology are closely enough related that there is a lot of overlap and connectedness,” Biklé notes. “I would say that neither Dave nor I knew what we were getting into with ‘The Hidden Half,’ but we had the right foundation and added to it when we wrote ‘What Your Food Ate.’”

For Montgomery, it all goes back to the interconnectedness of, well, everything. With extensive studies on soil degradation,

but copsMontgomery to the exact opposite.

landslides (after the tragic landslide in Oso in 2014, Montgomery appeared on various news segments to discuss the science behind landslides), desertification and salmon population degradation, it would be easy to take a pessimistic outlook on the world, but Montgomery cops to the exact opposite.

Without the budget to bring in the truckloads of compost needed to make the garden more hospitable for plants, Biklé started a years-long crusade to transform the soil. First, she collected materials to make mulch. She called arborists asking for wood chips they didn’t want to pay to dispose of. Then she started gathering other organic matter: dead leaves from

“I’ve become an optimist through writing these books,” he says. “There are ways to turn things around, to stop soil degradation and restore it, to increase salmon populations. Habit tends to be the biggest problem standing in the way—from what people are taught to people’s perceptions of how things work. I hope my work helps open some people’s minds and bring about change.”

FALL 2023 27

TRIBE AND TIMBER

BY CAITLIN KLASK

Tom Hinckley learned to see the forest for the trees

PHOTO BY RON WURZER

BY CAITLIN KLASK

Tom Hinckley learned to see the forest for the trees

PHOTO BY RON WURZER

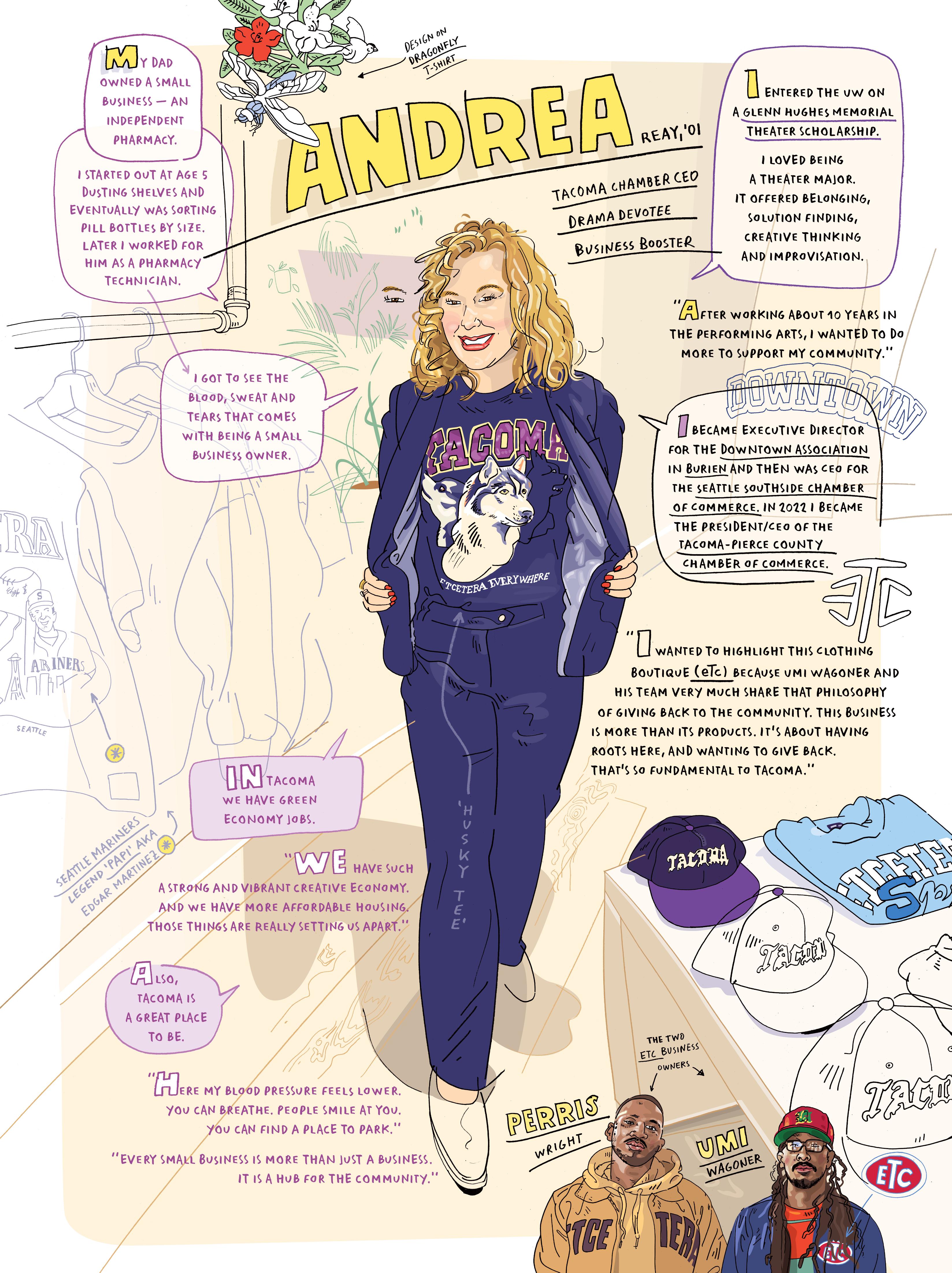

For his work with the Yakama Nation, �om Hinckley received the Golden Graduate Distinguished Alumnus Award for sustained, long-term and meaningful engagement with the UW. With the help of Polly Olsen, ’94, left, and other Yakama members, he taught his students to broaden their understanding of natural resource stewardship.

Anyone who keeps up with their grade-school science lessons knows that a forest ecosystem is a complex balance between living organisms and their environment. When we alter that balance, whether through harvesting timber or camping in the backcountry, we may (or, more often, may not) feel a responsibility to cover our footsteps—to leave no trace, to plant a tree for every tree harvested—so that the ecosystem continues.

But what if we considered ourselves as an integral part of that ecosystem? What if our culture, our families, and our economy connected us more intimately and personally with the land we occupy?

The Yakama Nation reservation consists of 1.6 million acres in south central Washington state. Approximately two-thirds of these acres are forested, and three UW School of Environmental and Forest Sciences (SEFS) alumni hold deep passions for that land: Phil Rigdon, ’96, deputy director of natural resources for the Yakama Nation; Everett Isaac, ’96, ’99, Yakama Nation assistant superintendent of natural resources; and Steve Rigdon, ’02, general manager of Yakama Forest Products. When they invited faculty at the UW—including Professor Emeritus Tom Hinckley, ’71—to learn about their forests and their approach to its stewardship, Hinckley and others eagerly accepted their invitation.

In early October 2003, 62 UW undergraduate students and four faculty visited the Yakama Nation for two days, hosted by Yakama elder Arlen Washines and other tribal members, to share stories and cultural practices. This October will be the 21st consecutive visit.

“They had an approach that was strongly based on tradition but was also a merging of modern technological tools and traditional knowledge,” says Hinckley. “It was this braiding of two ways of knowing about a forest, a forest that has been part of their history since time immemorial, to which they felt our students should be exposed. As a student, you need to know that there are other ways of knowing and practices associated with landscapes and places.”

Hinckley and the Rigdons initiated a formal partnership between the SEFS and the Yakama Nation that included many shared responsibilities, of which the tribal-hosted field trip to the Yakama reservation was central. On the field trip, students and faculty heard and witnessed how tribal members embody cultural, social, ecological and economic values for the purpose of sustaining their people and their land. The visitors witnessed the harvesting and preparation of culturally significant plants for meals and food ceremonies. Similarly, they saw the full spectrum of forest stewardship, including the use of prescribed fire and the transformation of a log into lumber. “Most students at the UW don’t have these kinds of experiences when you go and talk to Weyerhaeuser or the U.S. Forest Service about a forest,” says Hinckley.

The class, titled “Role of Culture and Place in Natural Resource Stewardship: The Yakama Nation Experience,” touches on environmental and social injustices, like federal laws that conflict with cultural practices, or the prioritization of saving second homes versus saving reservation forests during wildfires.

“When part of the Department of Natural Resources state-managed land burns, they have other lands in other parts of the state that they can use to extract wood to meet trust obligations,” says Hinckley. “Whereas with tribal lands, that’s their only land,

which is a very small part of their original homeland.”

More than 800 students have visited the Yakama Nation lands as part of these UW field trips. For the past decade, Hinckley— who retired in 2012—has sustained the course as an unpaid volunteer. The reins are now in the hands of former co-instructors Ernesto Alvarado, a SEFS faculty member and fire ecologist from Mexico, and Polly (Rigdon) Olsen, ’94. Olsen has assumed a critical instructional role over the last three years, including guiding students and tribal participants.

Olsen, who came to the UW in the late ’80s, followed by her brothers—Phil and Steve Rigdon—took the course to the next level. “We’ll keep the basic framework,” she told Hinckley, “but I’m going to add some other voices to it.”

Hinckley speaks passionately about Olsen’s changes to the class. “You hear from a very broad cross-section of the tribal leadership and elders involved in all sorts of social and environmental and health-related issues with the Tribe, integrating that into our understanding of how Native people think about their culture and their homeland—where they’ve been, where they are and where they’re going.”

Before the three siblings invited Hinckley to think differently about teaching forestry, he taught from his own perspective, that of a white researcher from Pennsylvania who loved the outdoors. “My brothers just called him in,” says Olsen. “They said, ‘You’re talking about traditional knowledge, and you’re not talking to the people who know the most about it.’” She tells a story of Hinckley on the first field trip: He arrived on Yakama Nation lands, hopped out of the bus and immediately began teaching—both to his own students and the Yakama people. “He starts telling Yakama people and guests the importance of this land, and he caught himself! Because everybody was looking at him, especially the Natives. So, with that, he started his own journey of looking at whose voices are being heard, whose stories are being told.

“He’s always listened to the trees and the forests and the plants, but he started listening differently,” says Olsen.

Olsen and her brothers admit it was a risk to bring Hinckley and his field-trip participants to their ancestral lands. But all three of them agree on one thing: He kept showing up. “Tom just stayed in the journey, and he didn’t get distracted,” says Olsen.

“It gets back to the saying that you have two eyes, two ears and one mouth, and you strive to use them in that proportion. Because you listen and because you witness, you become much more sensitive,” says Hinckley. “Being persistent. Showing up. Being the consistent face that people saw.” Hinckley showed up by sponsoring a campus gathering for a relative, and a UW student, who died in a car accident. He showed up by prioritizing the recruitment of Native students to the UW. He showed up by creating a support fund for students who need money to support their lives and learning at the UW, enabling them to honor the deep familial ties in Native and BIPOC families.

“The important part is the scholars that we touch and impact,” says Olsen, adding that “education is always going to be worth it. The hope for the future is that more instructors will teach as Tom has learned—to value other innovations, other contributions, to give credit where credit is due.”

When he taught forestry during his 43-year career at the UW from his own perspective, Hinckley didn’t see the forest for the trees. By listening to the original stewards of the land, adding their voices to the course and eventually handing over the reins, he became a true part of the forest ecosystem.

FALL 2023 29

The

tough, turbulent and victorious story

of uw women ’ s rowing

MAKING WAVES

B y H annelore s udermann

As excitement grows for the new major motion picture featuring the men’s crew of 1936, it’s time to acknowledge the “girls in the boat.”

30 UW MAGAZINE

Almost as soon as UW men started rowing, women did, too. Here, women’s crew members from the early 1900s join coach Hiram Conibear in front of the boathouse on Lake Washington.

Despite pressure from the UW’s academic leaders, Conibear supported the women students’ efforts.

What couldn’t women do?

At the turn of the last century, that was the big question. Shaking off Victorian strictures, young women were challenging gender roles, demanding the right to vote, climbing mountains and attending college.

Why shouldn’t they, then, partake of one of the most popular sports at the University of Washington?

Despite resistance from campus leaders, they did. The sweet-scented pages of an old Tyee yearbook reveal that in 1903—one year after the men’s crew was formed—a women’s rowing team was out on Lake Washington in four-oared barges. The entry names 10 students “in training” and describes them as rising early to be at the dock by 6 a.m. and using “the same boat as the boys and under the same conditions.” To do this, the women hiked down muddy, wooded trails in their woolen exercise uniforms to learn and master a sport that was just catching hold on the West Coast. The story of women’s rowing at the UW—rife with hardship, gumption and elite athleticism—is every bit the classic Northwest tale as the men’s.

Former men’s coxswain, Eric Cohen, ’82, has spent the past two decades chronicling the history of rowing at the UW. He was at first challenged by the paucity of details about the early years of women’s crew at the UW. In addition to relying on the research of only a few other historians, he dug into old yearbooks and newspapers to find details of the early efforts.