AHEAD OF THE GAME

UW Sports Medicine keeps student-athletes on the go

The real value of education

The UW leads national movement for broad-based support p28

Values are Our Currency

It’s a new world for studentathletes earning money p30

Knight Time

Doreen Alhadeff convinces Spain to welcome back Jews p32

Jetting Off

In 1966, Boeing signed a contract with Pan American World Airways to produce the world’s first jumbo jet.

The first 747 flew out of Paine Field in 1969. This past December, the last one, No. 1574, rolled out of the massive Everett assembly building, not yet dressed in its new owner’s livery.

While many UW alumni had their hands in the development and production of the 747, it was Joseph Sutter, ’43, who served as its chief engineer. He led a team of 4,500 workers bent on creating a plane that could carry more people and fly longer and farther than any other aircraft.

“If ever a program seemed set up for failure, it was mine,” he wrote in his autobiography. But his oversight and attention to detail helped turn 6 million parts and 150 miles of wiring into the world’s most recognized plane, and one that has dominated the skies for more than 50 years.

The 747 was created to meet booming air travel demand, and at 231 feet long, it could hold up to 360 passengers (later versions carried up to 500), cutting airfares in half and putting the rest of the world within reach. But it was also prized for its cargo capacity. Today, 450 are still in service. Because of the model’s longevity, it will continue to cross our skies for decades to come.

SPRING 2023 1 OF WASHINGTON PAINE FIELD, EVERETT

Photo by David Ryder

ENJOY MORE TRAINS BEGINNING MARCH 6 4 Daily trains between Seattle and Vancouver, BC 8 Daily trains between Seattle and Portland 4 Daily trains between Portland and Eugene Portland Vancouver, B.C. Seattle AmtrakCascades.com

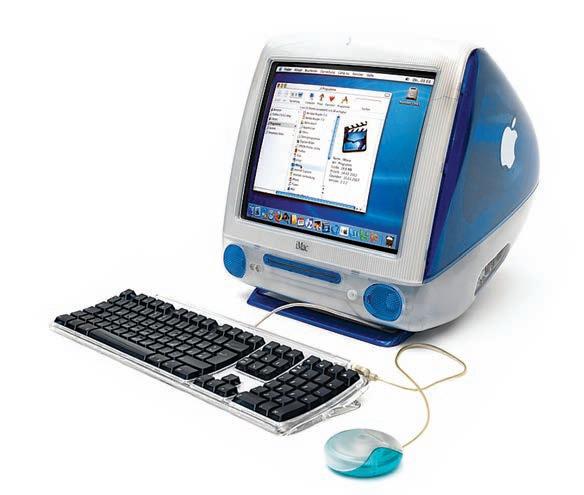

DARE TO DO

At the University of Washington, we dream up new possibilities and turn them into reality. But we don’t just lead the way — we prepare tomorrow’s leaders and visionaries to shape the future. Positive change starts with you.

uw.edu/boundless

Selena Prudente Rendon, ’21 B.A., American ethnic studies

Selena Prudente Rendon, ’21 B.A., American ethnic studies

VOLUME 34

NUMBER 1

SPRING 2023

ONLINE magazine.uw.edu

24 The Way Ahead

Schools nationwide are struggling with the decline of public support for higher education. Learn what the UW is doing about it.

By Hannelore Sudermann

26 Values Are Our Currency

A new twist to college sports is the world of NIL—name, image and likeness—which allows student-athletes to earn income.

By Jon Marmor

28 Knight Time

Doreen Alhadeff was honored by Spain for her quest to allow Sephardic Jews to regain their rightful Spanish citizenship.

By

David Volk

32 Ahead of the Game

After an injury, a star athlete turns to UW Medicine’s Sports Medicine Center for help getting back on the court.

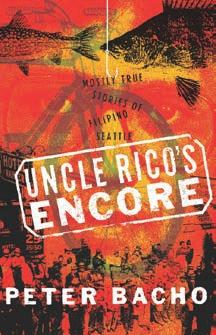

By Jamie Swenson

BOWLED OVER TEXAS

Led by defensive lineman Voi �unuufi (90), the Huskies smothered the �exas offense during their 27-20 Alamo Bowl victory. Story, Page 22.

MATCHA TO

So long to Jerry Thornton, a great ballplayer and family man.

DEEP MUD, BOTH FEET

UW student veterans visit Vietnam to explore the duality of war and find the path to peace.

by Mark Stone

ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS

4 UW MAGAZINE

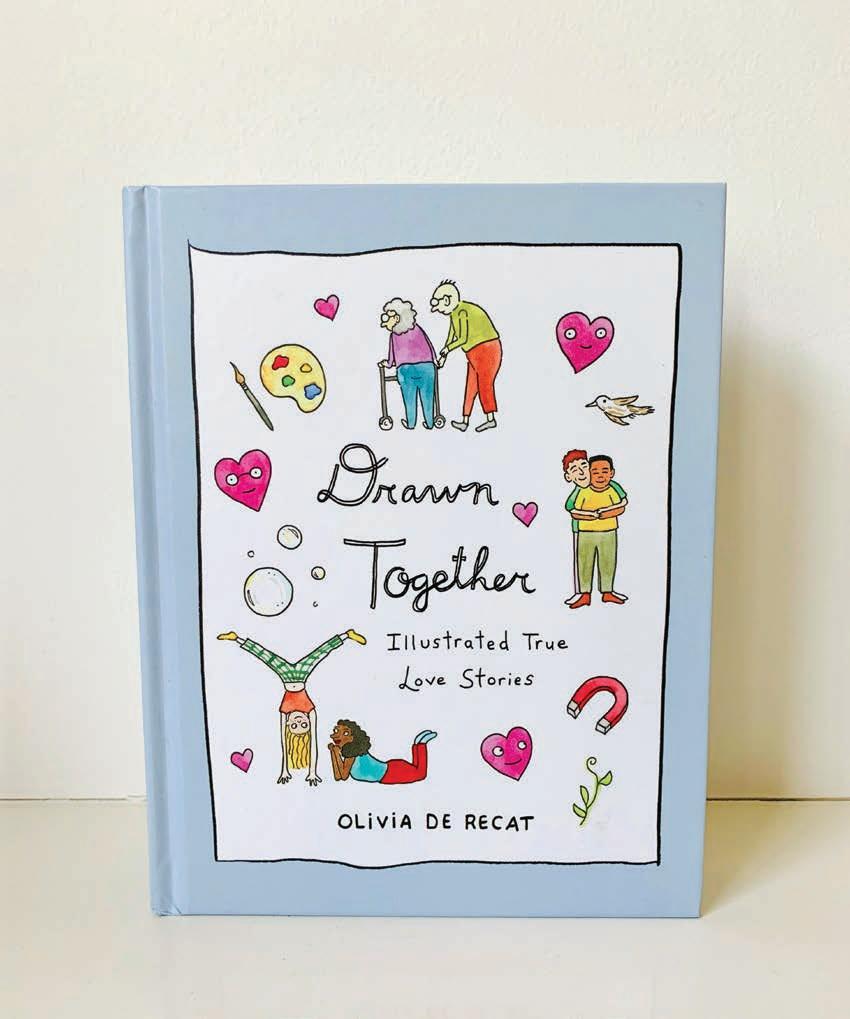

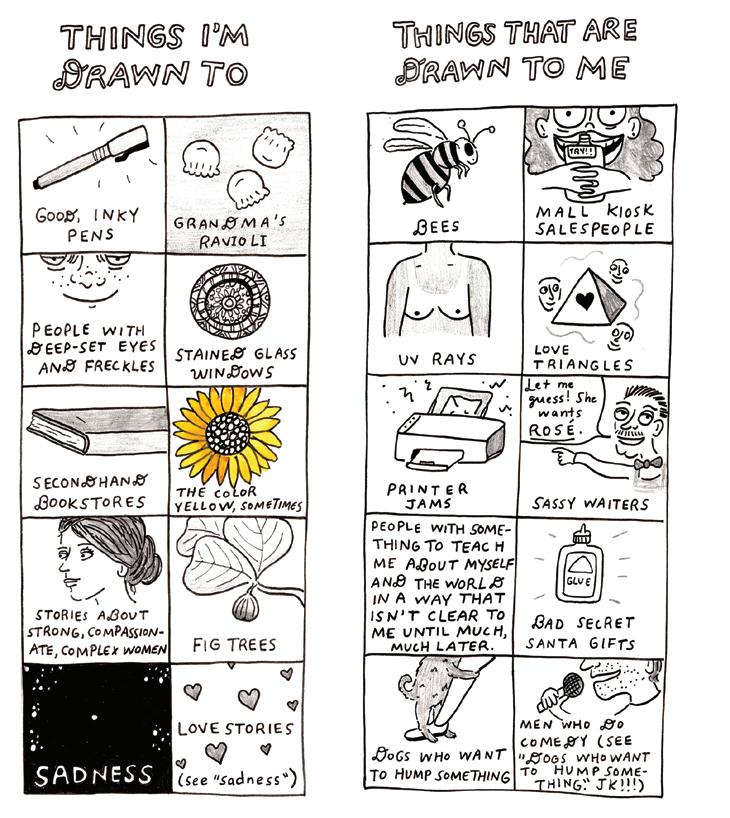

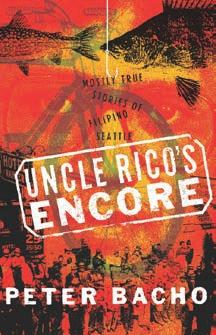

FORWARD 6 Youth Mental Health 8 Rural Service 10 Roar from the Crowd THE HUB 12 Rowing’s Cathedral 13 State of the Art 14 Research 22 Athletics COLUMNS 38 Peter Bacho 39 Sketches 41 Media 53 Tribute 54 In Memory IMPACT 44 Liftoff 46 Sense of Purpose 48 Plant Power UDUB 56 Sculpting Creativity

takes

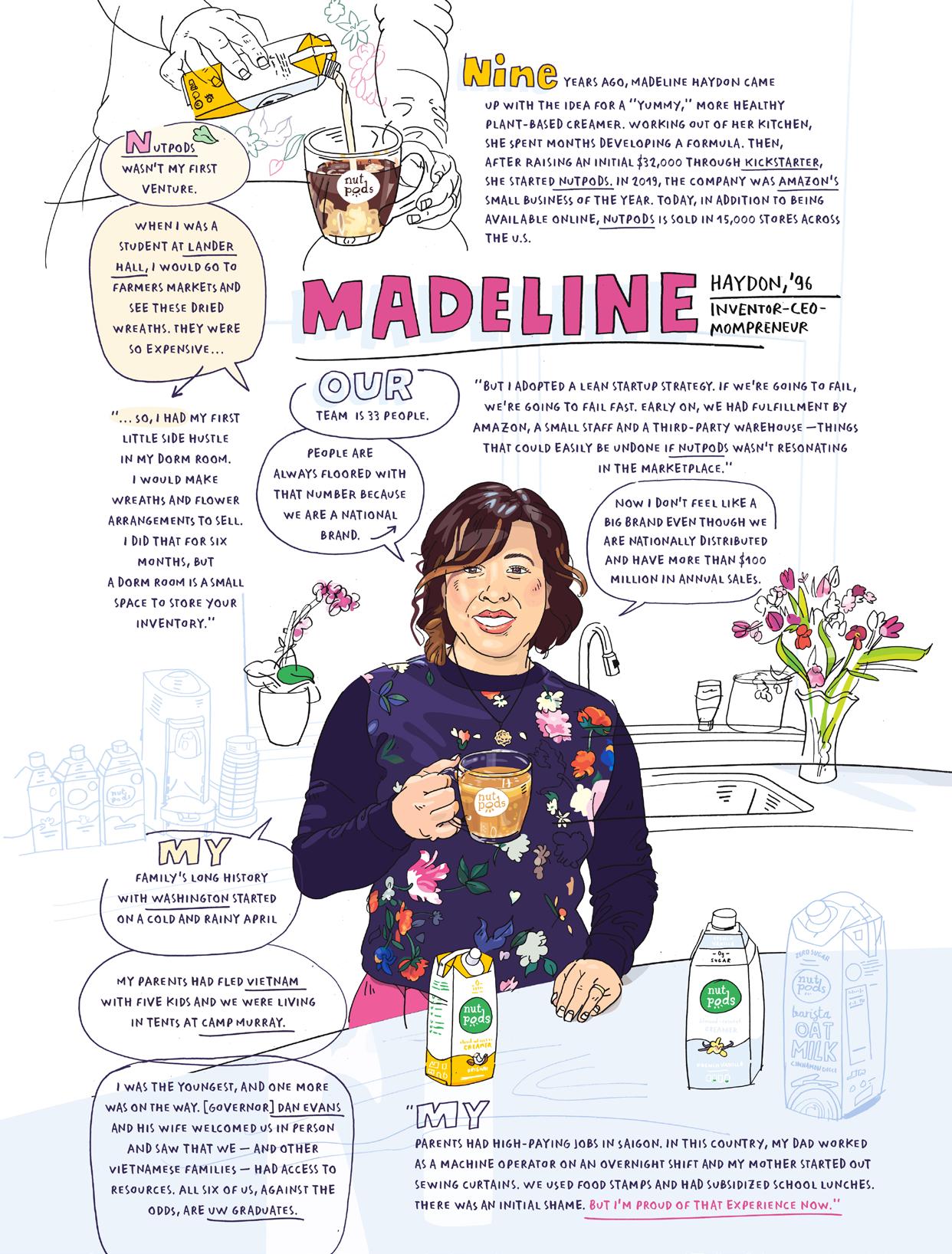

TALK ABOUT Entrepreneur and matcha enthusiast Rachel Barnecut, ’12, ’18,

her tasty tea to the next level at Matcha Magic.

CAPTAIN FANTASTIC

ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS

ON THE COVER Husky setter Ella May Powell goes up a for a block during a practice last fall.

Photo

SPRING 2023 5 ON APRIL 6, YOU’LL BE PART OF SOMETHING BIG HUSKY GIVING DAY IS APRIL 6! Let’s do BIG things, together. Join us and help build a better tomorrow. SCAN the QR code to see all participating programs GIVE at givingday.uw.edu SHARE your UW love on social media using #HuskyGivingDay > > >

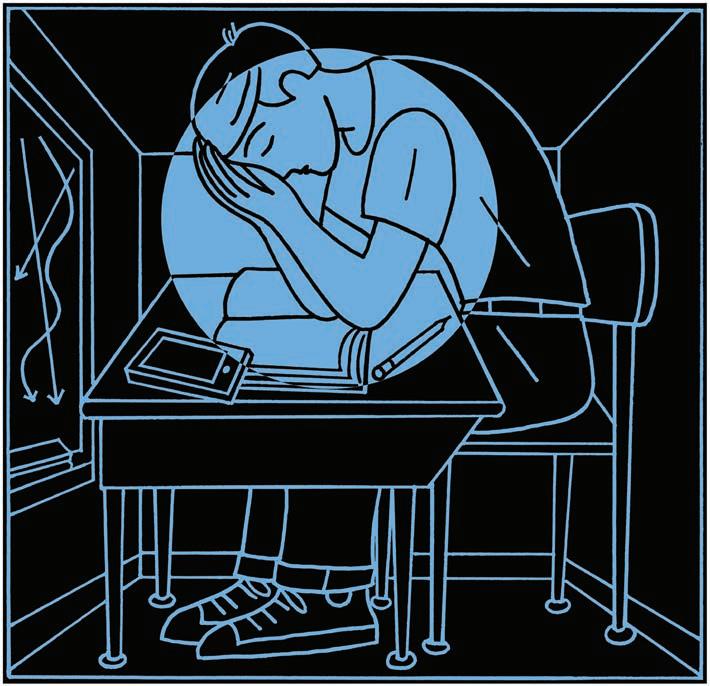

BY JENNIFER STUBER AND ERIC BRUNS

Helping Youth in Crisis

All across Washington state and the nation, our children and young people are feeling despair at levels never seen before. In 2021, 19% of eighth-grade students said they have seriously considered suicide in the last year, according to the Washington Healthy Youth Survey. This statistic is just a glimpse of the youth mental health crisis that was brewing before COVID and has now boiled over as students attempt to return to their in-person routines.

As parents of middle- and high-schoolaged children and as mental health professionals, we experience this crisis in youth mental health every day when we respond to desperate appeals for help from other parents. As faculty in a research and training center focused on school-based mental health, we also experience this crisis as we respond to requests for help from

schools across the state—schools that are weathering the anguish of multiple student deaths by suicide in a single year or the horror of one student shooting another student in their halls.

Although the crisis shows no signs of abating, there are indications of a proactive response. Schools are stepping further into their role in the prevention of mental health problems and suicide among their students. But they have so much to do already as they fulfill their educational mission. Schools need help if they are going to do more in the realm of youth mental health and suicide prevention.

One critical strategy is to invest in comprehensive youth mental health infrastructure in schools. Schools are where youth spend the majority of their waking hours and where they build relationships with

trusted adults and friends. School staff can provide instruction on positive relationships and coping with difficult emotions. They can connect with young people and take notice when they are struggling.

Schools are also the most common venue for young people to find mental health treatment. Recognizing this, the 2022 Washington Legislature increased funding for school mental health professionals. These professionals are critical resources for students who are struggling, providing them with group and individual treatment while also helping teachers and staff implement a comprehensive mental health strategy for the whole school.

Despite recent and proposed funding increases, schools are still woefully under-resourced. Staffing ratios for school social workers in Washington (one for every 14,391 students) are at one-fiftieth the level recommended by the National Association for School Social Workers (one for every 250).

But who will fill these positions so essential to our young people’s well-being? We’re working on it. Inspired by the Ballmer Group-funded Behavioral Health Workforce Development Initiative developed by UW Social Work Dean Eddie Uehara and Associate Dean Ben DeHaan, the U.S. Department of Education recently awarded our state $6 million to create a pipeline from Washington’s five Master’s of Social Work training programs to Washington state schools. Through this pilot program, 100 aspiring social workers will receive conditional scholarships based on their financial need. These conditional scholarships oblige recipients to work in a high-need district for at least two years after graduation. They will have pre-service training, be placed at schools in internships to support their future leadership roles in schools after graduation and have opportunities for continued connection with students across the state with whom they trained.

These and other strategies provide hope that we can collectively respond to the crisis by investing in school-based mental health. Our project is just getting off the ground. If you’d like to know more, email us at uwsmart@uw.edu.

Eric Bruns is a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences in the School of Medicine. Jennifer Stuber is an associate professor in the School of Social Work. �hey are core faculty at the UW’s School Mental Health Assessment, Research and �raining (SMAR�) Center.

6 UW MAGAZINE OPINION

ILLUSTRATION BY ANTHONY RUSSO

AND THOUGHT FROM THE UW FAMILY

Trust Your Heart to Us

UW Medicine Heart Institute is the only cardiovascular program in Washington directly connecting patient care with a top-rated medical school and research powerhouse. Our experts not only teach future cardiovascular specialists, but also continuously improve care for common to complex heart conditions. Benefit from our nationally recognized patient care at multiple locations across the Puget Sound region.

uwmedicine.org/heart

MESSAGE FROM THE EDITOR

Reaching Rural Communities

UW’s efforts to train dentists for non-urban, underserved populations proves a big hit

By Jon Marmor

By Jon Marmor

Bringing health care to rural and underserved populations in Washington and the region at large has long been a priority for the University of Washington. It started with the School of Medicine’s WWAMI program, which educates medical students to serve residents of rural communities in Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana and Idaho. And here’s another dynamite example of the UW’s impact outside of Seattle: the School of Dentistry’s Regional Initiatives in Dental Education program.

Known as RIDE, the program just marked its 15th anniversary. Operating in conjunction with Eastern Washington University as well as the WWAMI program, it trains up-and-coming dentists to meet the needs of people who live outside of large population centers. This initiative is so urgently needed that it has received invaluable support from dental associations, community health centers, Area Health Education Centers and other stakeholders.

The results are simply amazing. Since the program was funded by the Legislature in 2007 and produced its first graduates in 2012, more than 75% of its students have gone on to work at community clinics throughout Eastern Washington and other states’ rural and underserved areas. Many community health centers in Eastern Washington are completely run by RIDE students, too. That is the definition of impact.

Dr. Arley Medrano, ’18, ’22, is a prime example of what the UW has been seeking to accomplish. “I grew up in Okanogan, I grew up in the surrounding area, I know how important it is to have access to care,” he says. “It was very important for me to return to help a community that raised me and built me into the person I am today.”

Dr. Frank Roberts, the School of Dentistry’s associate dean for regional affairs and director of the RIDE program, perhaps summed it up best. “When you practice dentistry in an urban area, you make a big impact on your individual patients,” he explains. “But when you practice in a rural, underserved setting, you impact the whole community. That’s really special.”

And that is what the University of Washington is all about: serving the needs of citizens from the entire state and region, all of whom deserve the same kind of attention and care as those who live in the big cities. After all, the UW is the University for Washington.

STAFF

A publication of the UW Alumni Association and the University of Washington since 1908

PUBLISHER Paul Rucker, ’95, ’02

ASST. VICE PRESIDENT, UWAA MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS Terri Hiroshima

EDITOR Jon Marmor, ’94

MANAGING EDITOR Hannelore Sudermann, ’96

ART DIRECTOR Ken Shafer

DIGITAL EDITOR Caitlin Klask

CONTRIBUTING STAFF Ben Erickson, Karen Rippel Chilcote, Kerry MacDonald, ’04

UWAA BOARD OF TRUSTEES PUBLICATIONS

COMMITTEE CO-CHAIRS

Chair, Sabrina Taylor, ’13 Vice Chair, Roman Trujillo, ’95

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Rachel Gallaher, Hannah Hickey, David Silverberg, Chris Talbott, David Volk

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Matt Hagen, David Ryder, Mark Stone, Dennis Wise, Ron Wurzer

CONTRIBUTING ILLUSTRATORS

Joe Anderson, Olivier Kugler, David Plunkert, Anthony Russo

EDITORIAL OFFICES

Phone 206-543-0540

Email magazine@uw.edu

Fax 206-685-0611

4333 Brooklyn Ave. N.E.

UW Tower 01, Box 359559

Seattle, WA 98195-9559

ADVERTISING

SagaCity Media, Inc.

509 Olive Way, Suite 305, Seattle, WA 98101

Megan Holcombe mholcombe@sagacitymedia.com

703-638-9704

Carol Cummins ccummins@sagacitymedia.com

206-454-3058

Robert Page rpage@sagacitymedia.com

206-979-5821

University of Washington Magazine is published quarterly by the UW Alumni Association and UW for graduates and friends of the UW (ISSN 1047-8604; Canadian Publication Agreement #40845662). Opinions expressed are those of the signed contributors or the editors and do not necessarily represent the UW’s official position. �his magazine does not endorse, directly or by implication, any products or services advertised except those sponsored directly by the UWAA. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to: Station A, PO Box 54, Windsor, ON N9A 6J5 CANADA.

8 UW MAGAZINE

ILLUSTRATION

BY DAVID PLUNKERT

Smart seniors love living at Mirabella.

In South Lake Union.

Mirabella Seattle is a resident-centered, not-for-profit Pacific Retirement Services community and an equal housing opportunity. Imagine a place where resident UW alums & retired professors discuss the issues of the day. And guest speakers educate as well as entertain. And everyone enjoys fun social events daily. And we haven’t even mentioned the impressive list of services and amenities, the beautiful living spaces, or the lifelong healthcare available. We invite you to come see Mirabella for yourself. It’s easy to find. In desirable South Lake Union and a few degrees above the rest. Please call today to schedule a tour. 116 Fairview Ave N • Seattle • 206.337.0443 www.mirabellaseattle.com Intellectually minded. Socially engaged. Hence, why we ran this ad in UW Magazine.

Black Doctors

Thank you for your fine article on Black doctors at the UW and in the Pacific Northwest (“A Medical Emergency,” Winter 2022). It shed much-needed light on the struggle at the UW to attract young doctors, and on the issue of health equity in general. I was particularly touched by your mention of several Black physicians and surgeons from my childhood in Seattle, including Alvin Thompson and the Lavizzos, Phillip and Blanche. Phillip and my father, John R. Henry, finished at Meharry Medical College at the same time and became the first Black surgeons in Seattle history when they settled there in 1957. I don’t know if you’re aware that Dr. Risa Lavizzo-Mourey, who you interviewed, was for many years the president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, one of the world’s largest and most influential health philanthropies. Our families—including Dr. Earl V. Miller, a urologist, and his wife, Rosalee Miller, a dentist who worked at the University for many years—were all close in those years, so your story brought back many warm memories of them from my childhood. There’s an old phrase about human progress that “we stand on the shoulders of giants.” That’s certainly how I view my parents’ generation of Black physicians and their spouses, who forged a path for themselves and their loved ones in Seattle in the 1950s and 1960s.

Neil Henry, Professor and Dean Emeritus, UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism

Black and White

I appreciate the well-written article “A Medical Emergency,” by Hannelore Sudermann. However, I don’t understand why every time the descriptive “Black” was used in the article, which was many, it was capitalized, and every time the descriptive “white” was used, it was not capitalized. Am I missing some grammar lesson or is the author revealing a prejudice in a subtle way?

Chris Jolley, ’92, Monument Valley, Utah

EDITOR’S NOTE:

University of Washington Magazine follows Associated Press style. In 2020, the AP decided to “capitalize Black in a racial, ethnic or cultural sense, conveying an essential and shared sense of history, identity and community among people who identify as Black, including those in the African diaspora and within Africa.”

Raft Hollingsworth

While I was pleased to see your obituary about the many contributions of Dorothy Hollingsworth in your Winter issue (“A Social Maverick,” Winter 2022), I was disappointed that there was no mention of her husband, Raft Hollingsworth. Mr. Hollingsworth, whom I first encountered as a terrified seventh-grader at Queen Anne High School in the fall of 1959, was one of the early African American teachers in Seattle Public Schools. He taught full time at Queen Anne beginning in 1957 and taught at Boren Middle School and Garfield High School. Although I am sure there were students at Queen Anne who resented his presence, I don’t remember anyone speaking of him with anything but respect. He was remembered for inventing games to help make learning math fun and wore his authority with grace and kindness. He, like his wife, Dorothy, contributed to making Seattle a better place.

Morgan Seeley, Quilcene

Astronaut Hero

The tribute to Michael Anderson (“Star Power,” Winter 2022) was excellent. It brought back memories of the privilege I had as Wing Chaplain at Fairchild AFB in 2003 to speak at Lt. Col. Anderson’s memorial service. The service was packed, with a considerable number of local clergy on the dais. He was beloved by the Spokane community. He set a fine example that I’m sure many young people, there and elsewhere, have sought to emulate. The Space Shuttle Columbia disaster remains seared into many of our memories, but it is comforting to know that the legacy of Anderson and his colleagues continues to inspire.

Robert C. Stroud, ’77, Seabeck

Valiant Volunteers

The story about the founding of the Harry Bridges Chair for Labor Studies (“Solidarity Forever,” Winter 2022) was great. I just want to point out that there is one other “formal reminder” of working-class people on campus and that is the memorial for the “premature anti-fascists” who fought to save the democratically elected government of Spain in the late 1930s. It is just off the path by the HUB on the way to Drumheller Fountain. In these perilous times, it is apropos to remember the brave men and women of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and all the other valiant volunteers from around the world who fought against the fascists in Spain.

Marion Wheeler Burns, ’71, Sequim

Speaking Up

How wonderful to read about “combining voices to make a difference” (“Higher Ed Can Be a Powerful Force for Good,” Winter 2022). Grassroots activism makes a difference, as my 30 years as a volunteer with RESULTS (results.org) has shown me. I am proud of the UW’s part in creating a better world and encourage all to speak up to support higher education on the state, national and global levels. Education leads to better health, more opportunity, and a brighter future for all. Together, we can use our voices to ensure everyone has this opportunity. Education equals hope and helps bring about solutions to the critical challenges we face today.

Willie Dickerson, ’73, ’94, Snohomish

UW PNW you 10 UW MAGAZINE

JOIN THE CONVERSATION EMAIL YOUR COMMENTS TO: magazine@uw.edu (Letters may be edited for length or clarity.)

ROAR FROM THE CROWD

SPRING 2023 11

The Aging Cathedral

Landmark status will aid the drive to restore the ASUW Shell House

By Hannelore Sudermann

�he historic ASUW Shell House on the Montlake Cut was built to be a training hangar for the Navy during World War I. It later became home to the UW rowing program and was recognized by the Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board in 2018.

It has been described as rickety. And some have called it a cathedral. Either way, more than a century after the last nail was pounded in, the ASUW Shell House, also known as the Canoe House, also known as the U.S. Naval Training Hangar, has become an official Seattle landmark.

The recognition took place in 2018 to subtle fanfare at a hearing of the Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board. The board determined that the structure—designed by the Navy during World War I and used for several decades as headquarters for the UW rowing teams—met multiple criteria for landmark status.

Susan Boyle, ’75, ’79, an architectural historian, made the case on behalf of the

UW. No stranger to the University, where she earned both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees, the alumna crafted a thorough report nominating the structure and noting how the campus has grown around it.

“It’s such an amazing place,” she says of the UW in Seattle. She points to the formal north campus where London plane trees line Memorial Drive as it rolls down between French Renaissance-style buildings. “Throughout campus there are just incredible gifts from prior generations of planners, designers and campus leaders,” she says. But the shell house was a humbler endeavor, she adds.

For thousands of years, the site was a crossing-over spot where Indigenous

people carried their canoes between what are now known as Lake Washington and Lake Union. And then military and aeronautic history “give the building another level of importance,” Boyle says. Built for the seaplanes of the time, it is a rare example of its style of architecture. The trusses and many small pieces of wood form a gaping enclosed space, says Boyle. “It’s like you are in the bones of the whale just looking up at it. It’s really a treat.”

But most people associate the building with rowing since it served as home to the men’s and women’s crews for several decades, says Boyle. That includes the famous Husky team that won gold in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin—the focus of the New York Times bestseller, “The Boys in the Boat,” and of an upcoming feature film directed by George Clooney.

On a recent visit to the shell house, Eric Cohen, ’82, pointed out the afternoon sunlight streaming through the windows. “You don’t see light like this anywhere today,” he says. A former UW coxswain, Cohen now serves as team historian. The shell house is often in his research because of the generations of UW rowers who used it. In the late 1920s, a mezzanine was added to make a workshop where boat-building genius George Pocock crafted racing shells.

When the crew moved to the Conibear Shellhouse in 1949, the old hangar was turned into a home for the sailing team and a site where people could rent canoes. Around that time, the structure was described in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer as “the rickety UW boathouse.”

At different points, it was nearly forgotten by the University, says Cohen. “But they never really got around to tearing it down.”

Though the shell house was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975, students like Cohen and his teammates didn’t know about their historical connection to the building. “But today it has a national presence,” he says.

While landmark status may affect what changes the University can make to the structure, it also may help with efforts to restore it. A campaign is underway to raise $18.5 million to preserve and update the structure as a student space for lectures and gatherings, a cultural center and a venue for meetings, conferences and special events.

Boyle has no doubt it will someday welcome thousands of visitors: “The building has many, many fans.”

NEWS AND RESEARCH FROM THE UW 12 UW MAGAZINE

MOHAI, PEMCO WEBSTER & STEVENS COLLECTION, 1983.10.1246

Body Language

The Burke Museum’s special exhibit gallery feels like an escape. The latest exhibition, “Body Language: Reawakening Cultural Tattooing of the Northwest,” submerses visitors in traditional tattooing practices and their modern expressions. The exhibit examines the rich history and artistry of Indigenous tattooing of the Northwest coast. Photographs, cultural belongings and contemporary art reveal how these previously disrupted and banned traditions have endured through artists' efforts. “Body Language” celebrates the resilience of Indigenous tattoo practitioners and those who wear the visual language of their ancestors on their bodies. The exhibit runs through April 16.

TheHub

STATE OF THE ART BURKE MUSEUM

Photo by Aaron Leon

Parasite Paradox

Using specimens from the Burke Museum, a research team finds a worrisome decline

By Hannah Hickey

�his copper rockfish (Sebastes caurinus) was collected in 1964 in Puget Sound. It was part of a new study that examined specimens of eight fish species and found a dramatic decline in the number of parasites over time.

A recent UW study examined more than a century of fish specimens from the Puget Sound and found that fish parasites are far less abundant now than they were in 1880.

The data, which was developed in large part from preserved fish in the UW Fish Collection at the Burke Museum, suggests that parasites may be especially vulnerable to a changing climate.

“People generally think that climate change will cause parasites to thrive, that we will see an increase in parasite outbreaks as the world warms,” says the study’s lead author, Chelsea Wood, associate professor of aquatic and fishery sciences. “For some parasite species that may be true, but parasites depend on hosts, and that makes them particularly

vulnerable in a changing world where the fate of hosts is being reshuffled.”

For parasites that rely on three or more host species during their lifecycle—including more than half the parasite species identified in the study’s fish—analysis of historic specimens showed an 11% average decline in abundance per decade. Of 10 parasite species that had disappeared completely by 1980, nine relied on three or more hosts.

“Our results show that parasites with one or two host species stayed pretty steady, but parasites with three or more hosts crashed,” Wood says. “The degree of decline was severe. It would trigger conservation action if it occurred in the types of species that people care about, like mammals or birds.”

And while parasites inspire fear or disgust—especially for people who associate them with illness in themselves, their kids or their pets—the result is worrying news for ecosystems, Wood says. “Parasite ecology is really in its infancy, but what we do know is that these complex-lifecycle parasites probably play an important role in pushing energy through food webs and in supporting top apex predators.”

SLEEP SOLUTION

A study measuring the sleep patterns of 500 UW students illustrates the importance of getting outside during the day, even when it’s cloudy. Published in the Journal of Pineal Research, the study found that the subjects fell asleep later in the evening and woke up later in the morning during winter. “Our bodies have a natural circadian clock that tells us when to go to sleep at night,” says biology professor Horacio de la Iglesia. “If you do not get enough exposure to light during the day when the sun is out, that ‘delays’ your clock and pushes back the onset of sleep at night.” In addition to noting that delayed timing of sleep was evident during the winter months, the study found that daily exposure to daylight is key to preventing a delayed phase of the circadian clock and the circadian disruption that is typically exacerbated in high-latitude winters like ours.

Virtual 3D tours on real-estate websites such as Zillow and Redfin allow viewers to explore homes without leaving the comfort of their couches. Sometimes the homes contain evidence of current residents’ lives. Curious about whether personal belongings visible in 3D tours could introduce privacy risks, UW researchers examined 44 tours. Each was for a home in a different state and had at least one personal detail—like a letter, a college diploma or photos—visible. The researchers concluded that the details left in these tours could expose residents to threats, including phishing attacks and credit card fraud. “With 3D tours, it is possible to see all rooms in a house and many more angles of a room than with photos,” says Rachel McAmis, ’22, a doctoral student in computer science and engineering and lead author on the study. The team published the findings in November and will present them at the USENIX Security Symposium in August.

RESEARCH APRIL HONG ISTOCK 14 UW MAGAZINE

SELLER BEWARE

NATALIE MASTICK/UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON

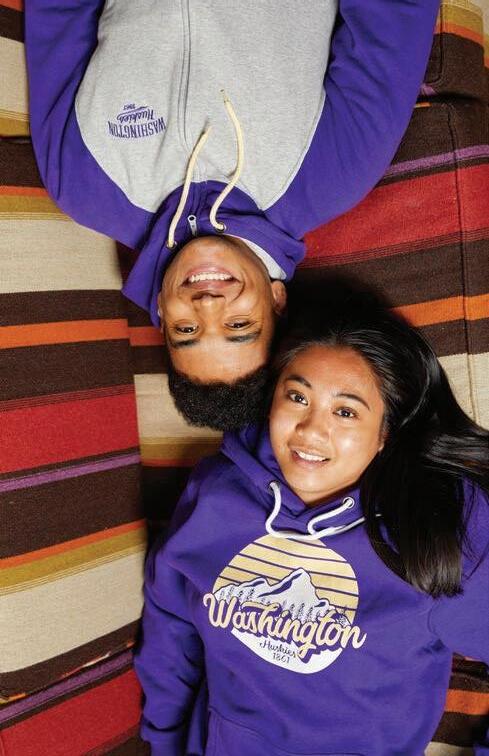

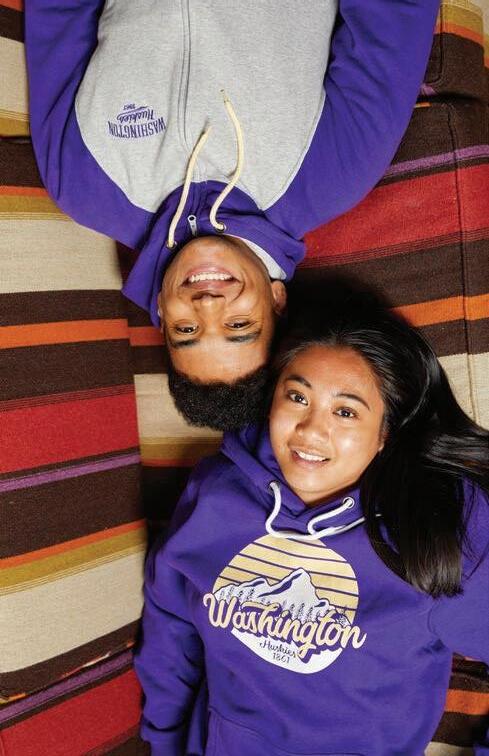

PLAY LIKE YOUR HUSKY HERO

On or off the court and fi eld, support your favorite UW athletes—like Husky volleyball’s All-American setter Ella May Powell. Customize a Washington Huskies jersey, hoodie or T-shirt with an athlete’s name and number. Visit the offi cial team store at shop.gohuskies.com for the complete selection of available UW men’s and women’s sports.

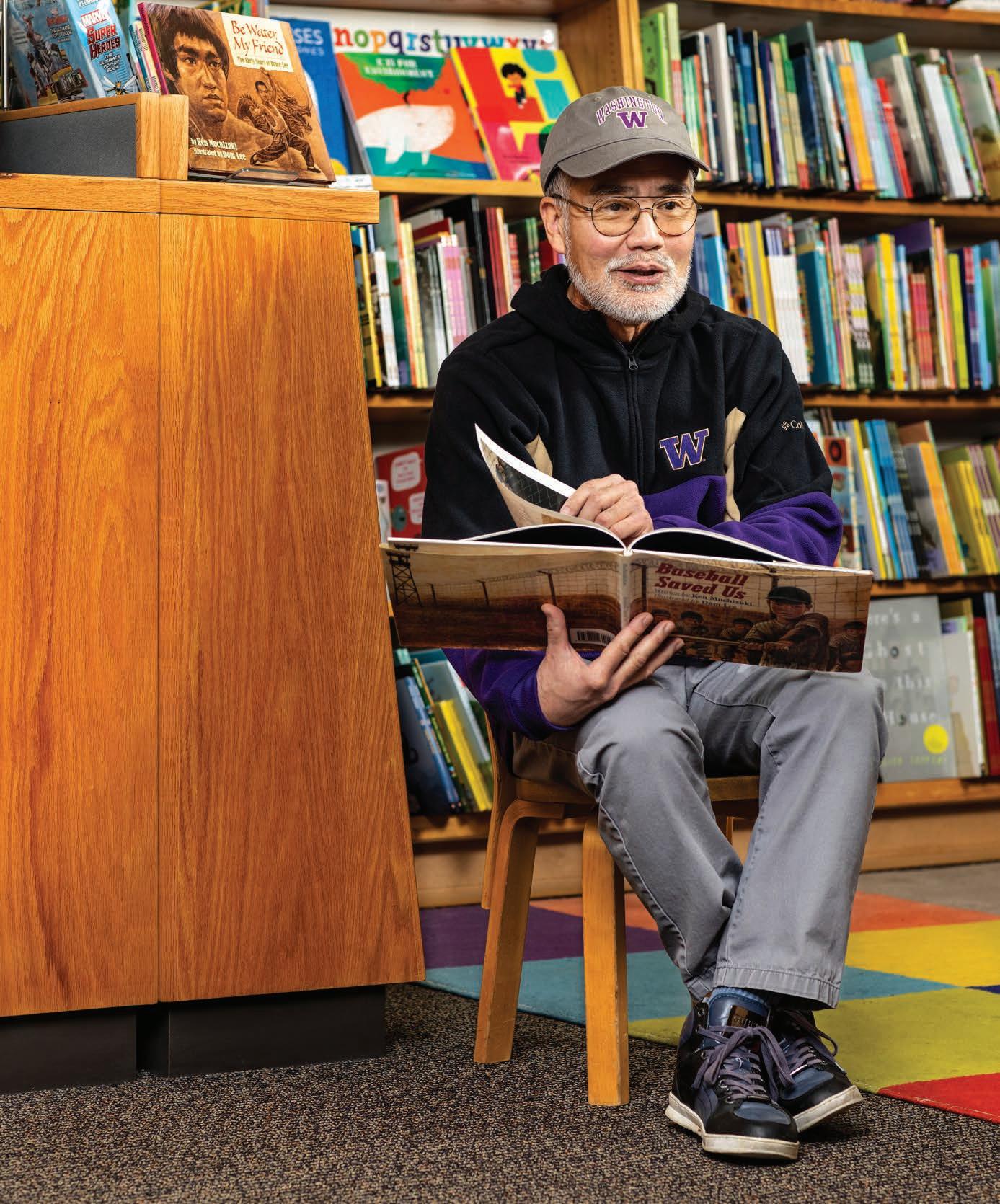

Back in Business to the 1990s

The Foster School library turns 25

By Hannelore Sudermann

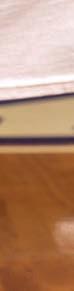

Synergy. Yes, that’s the word. Or should we say, that’s the corporate buzzword and one of the many hangovers from American business culture in the 1990s.

It was synergy at work when Jason Sokoloff, head librarian at the Foster School of Business, and his team decided to create something joyful and unconventional to welcome students back to campus last fall. At that point, they remembered their library was about to turn 25.

“The idea sort of dawned on us as we were getting ready to reopen,” Sokoloff says. “We had a small display case and we could exhibit something that had connection with business and industry.” They chose to tap into trappings from a quarter century ago and curate a pocket exhibit they call “It Came From the ’90s.”

“We pulled it together through our social connections,” Sokoloff says. After going through their own attics and sending emails to friends and colleagues, they came up with items including a Nintendo 64 (the last video game console that used cartridges), a Blockbuster card, a pile of Beanie Babies, a Tamagotchi, DVDs and other emphera.

The ’90s were the era of fax machines and Rolodexes and a heyday for buzzwords like “wheelhouse” and “bandwidth.” It was

the dawn of Zip drives and the decline of floppy disks. “We defined the exhibit as stuff people spent their money on: consumer and office products,” Sokoloff says. “The idea was to highlight consumer technology and pop culture.”

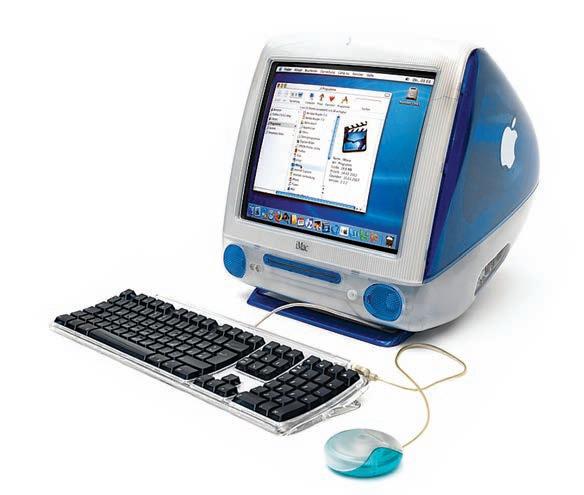

The exhibit’s pièce de résistance is a working iMac G3, borrowed from the Living Computers: Museum and Labs. It is stationed at the library entrance, where visitors can leave digital sticky notes.

The quarter-century-old library itself has the feel of an underground chapel. An 80-foot-long skylight brightens a central area packed with tables and chairs. Mornings there are quiet, but as the day progresses, students fill the seats. “We’re a big and popular study hall, arguably the busiest of the ‘branch’ libraries on the campus,” Sokoloff says.

The library serves more than 2,500 business students, most of whom have no memory of what it was like without computers in the house. For them, much of the exhibit—which runs through June 9— will seem novel and strange.

So much in the world of business is about looking forward, about finding the next new thing. Sokoloff and his team have found joy in looking back.

Find connection and joy IN EVERYDAY LIVING

Visit eraliving.com/joy to learn more. Locations in Wallingford and Issaquah. Ask about special benefits for members. UWRA-affiliated University House retirement communities feature intellectually rich activities, exquisite dining, a variety of exercise classes, and the supportive services you need to thrive in place as your circumstances change.

16 UW MAGAZINE

FELIX WINKELNKEMPER /WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

When the Foster library first opened, the iMac was changing desktop computing. Now one is part of a special exhibit celebrating the library’s birthday.

SPRING 2023 17

Opioid GameChanger

UW Medicine researchers zero in on a vaccine to prevent misuse and overdose of pain meds

By Chris Talbott

Drs. Jürgen Unützer and Marco Pravetoni are scientists and researchers whose professional lives are ruled by rigor, discipline and a passion for improving the lives of patients. At the same time, the Department of Psychiatry & Behaviorial Sciences colleagues are visionaries in the development vaccines and other novel treatments for opioid use disorders and overdose, among the deadliest of public health problems in the United States.

Pravetoni, a professor of psychiatry at the UW School of Medicine, has invested more than a decade of his career to pursuing the development and translation of vaccines and other antibody-based treatment strategies that have eluded scientists for more than half a century. He’s so close, he can see the outcome of these efforts: “I’m very excited about how far we have made it. I’m confident this will be a game-changer in the treatment of opioid use disorders.”

For Unützer, the psychiatry department chair and director of the Garvey Institute for Brain Health Solutions, the

but I think we’re validated in that.”

Monoclonal antibody-based treatments for substance use disorders and opioid use disorders could reach the market in five years, and vaccines for a multitude of addictive substances could be a decade away, Pravetoni predicts. That will require commercial investment, which will require more proof his methods can work. He and his colleagues have begun Phase One clinical trials of the first human oxycodone vaccine and are preparing to petition the U.S. Food & Drug Administration to allow human trials for vaccines targeting heroin, fentanyl, and their analogs or metabolites. His team also is seeking to initiate manufacturing of the monoclonal antibody treatments meant to complement Narcan, the only FDA-approved overdose reversal agent.

“These treatments would be incredibly powerful,” Unützer says. “They could help millions of people, and the work that he’s doing is at a fairly critical stage. He has proven in his laboratory that vaccines and antibodies can protect against some of the negative and dangerous effects associated with opioid misuse and overdose. The question now is: Can you do it in a human?”

monoclonal antibody could be administered alongside naloxone to save lives.

“This could really be a third pillar of treatment,” Pravetoni says. “Imagine antibodies as a sponge, and the sponge is going to mop up all the drug available. That will diminish the amount of drug that can actually get to the brain, which is a very different approach. We are not the first to come up with the idea of vaccines or monoclonal antibodies for addiction or overdose. But we are the first group to reach clinical trials with an opioid vaccine. And we are one of the very few groups in the U.S. that has funding to advance monoclonal antibodies for fentanyl overdose to clinical trials.”

The team advanced the understanding of the processes involved last fall when it released several papers identifying novel vaccines and monoclonal antibodies and their mechanism of action against fentanyl and other relevant target drugs. It hopes to start clinical trials for fentanyl and heroin vaccines in 2024. Pravetoni thinks it made perfect sense to bring his cross-disciplinary work to Seattle, where UW Medicine sits at the intersection of hightech and person-to-person approaches to modern medical problems.

Current treatments are not always sufficient for dealing with substance use disorders and preventing or reversing overdoses. But a growing body of research suggests that vaccines and monoclonal antibodies can be used.

Marco Pravetoni uses these novel strategies to develop new medical interventions and is among the first to test these new interventions in humans.

investment was the $2 million he staked for this vital work and the recruitment of Pravetoni away from Minneapolis in January 2022.

“Marco has raised about $20 million in federal funding to support translation of monoclonal antibodies against fentanyl overdose since he’s come here,” Unützer says. “What that says is there are very smart scientists now at the National Institutes of Health and at the National Institute on Drug Abuse who have recognized this really is a very promising approach. So we made a little bit of a gamble,

Addiction is one of America’s biggest public health problems, and there are few solutions to the crisis. The National Insitute on Drug Abuse says more than 100,000 people died from drug-induced overdose each year from 2020 to 2022. The psychiatry department’s Addictions, Drug & Alcohol Institute says overdose deaths in Washington state have increased 30% year over year from 2019 to 2020 and ’20 to ’21.

Although treatment and understanding have evolved quickly, there are really only two ways to treat addiction: drugs that block or replace the effects of misused substances, and psychotherapy and psychosocial approaches. These methods are imperfect and not widely used. A vaccine would allow psychiatrists to attack the problem in a different way, blocking the effects of opioids and other substances such as methamphetamine with drug-specific antibodies over a sustained period of time. In the context of overdoses, a

18 UW MAGAZINE

Become an advocate today Higher Education Needs Your Voice UWimpact.org

ADVOCATE

A program of the UW Alumni Association

These treatments would be incredibly powerful. They could help millions of people.

‘Revolution to Evolution’

The Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity tells its history in a new book

By Hannelore Sudermann

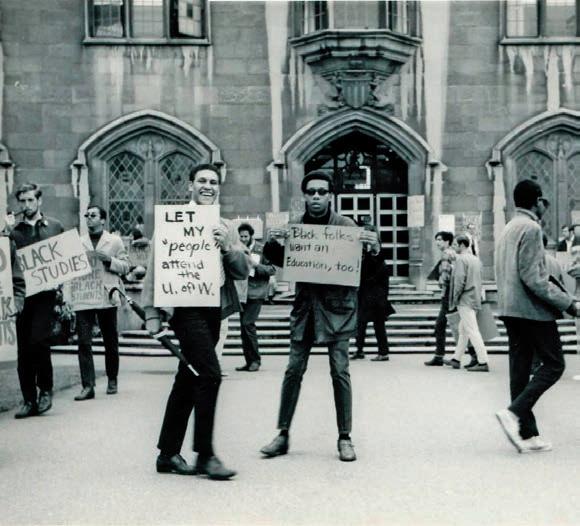

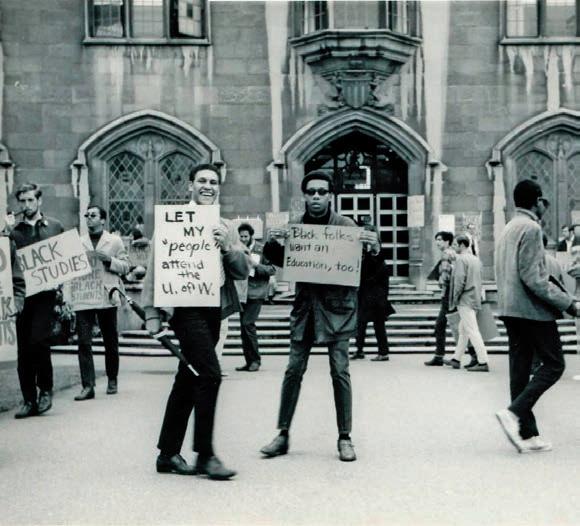

Above: Garry Owens, center, and Jesus Crowder, left, were among the activists who demanded the UW enroll and support a more diverse student body. �heir activism and input led to the formation of the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity and made the University more accessible to future generations of students.

Right: In 2013, students rallied for a requirement that all undergraduates must take at least one course that focuses on sociocultural, political and/or economic diversity.

Campus diversity is no longer a revolutionary idea. But it certainly was in the late 1960s and early ’70s when a small number of student activists and an even smaller number of faculty and staff pushed the University of Washington to serve all of the state’s potential college students.

With sit-ins, protests and a list of demands, the activists—led by the Black Student Union—insisted the UW recruit and support a multiracial, multicultural student body, hire faculty of color and expand the curriculum to be more culturally diverse. Through their activism, their vision and their continued engagement, they forged a new future for the UW and influenced the trajectories of generations of students.

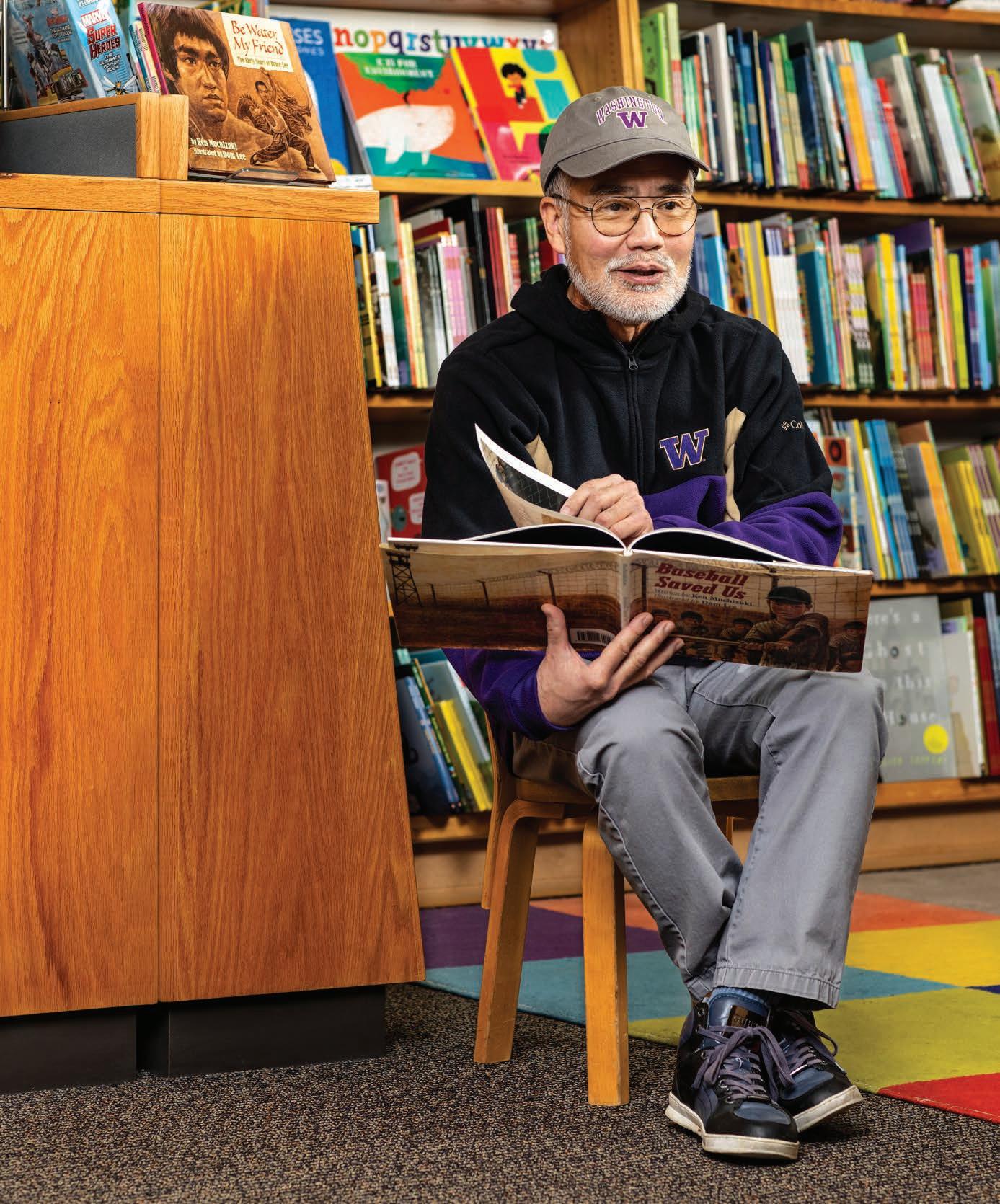

Now, Emile Pitre, ’69, one of those early student activists and a longtime member of the UW staff, has captured the story of the decades of work in his new book, “Revolution to Evolution: The Story of the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity at

the University of Washington.” He blends research and interviews with his own insights and memories to offer a comprehensive chronicle of one of the first diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programs in the country.

After describing the formative years of diversity work at the UW, Pitre fills in the eras, capturing the turbulence of the late 1970s and 1980s when administrators tinkered with admissions practices which led to protests, arrests and staff resignations. The 1990s brought state-mandated changes to enrollment policy that prohibited the consideration of race or gender in admissions. Instead of allowing the rule to thwart their efforts, the staff adapted, “and we kept moving,” Pitre says.

He also shines a light on colleagues who were driven to support students and undo structural and cultural racism across campus. Their efforts resulted in thousands of student successes. Erasmo Gamboa, ’70, ’73, ’84, for example, was one of the first to be recruited to the UW in late summer 1968. He remembers when a group of Black UW students drove into the city of Toppenish to find prospects for the new program. “They told us if we were interested, they would help us get in,” says Gamboa, who hadn’t imagined attending the UW.

Gamboa arrived on campus to join what was then called the Special Education Program and is today known as the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP). While he wasn’t high-achieving in high school, Gamboa graduated from the UW

with honors. He stayed to get his Ph.D. in history and, as a member of the faculty, became a leading scholar of Latino history.

In the book, Pitre calls out many more alumni successes including the current U.S. Poet Laureate, Ada Limón and Anisa Ibrahim, director of the Harborview Pediatrics Clinic. “It was an EOP counselor who truly believed in my dream to become a doctor and gave me practical steps to ensure my success,” says Ibrahim, whose family fled the civil war in Somalia and settled in Seattle when she was just 6. “I would not be where I am today without the [OMA&D] Instructional Center. I have never seen a more dedicated group of educators. They not only cared about our success as students but also cared about us as individuals. After a long day roaming campus, many of us referred to going to the IC as going home.”

“This is a significant book because it speaks to what is possible when programs and services are designed withunderrepresented and underserved students in mind,” says Rickey Hall, vice president for Minority Affairs & Diversity at the UW. As one of the first DEI offices in the country, it has an important story to share, he adds. “Hopefully other institutions will see what’s possible with intentionality and investment.”

“Revolution to Evolution: The Story of the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity at the University of Washington,” is published by the UW Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity and available through the UW Press for $29.99.

20

EMILE

UW MAGAZINE

PITRE COURTESY STEVE LUDWIG II

Some discounts, coverages, payment plans, and features are not available in all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. GEICO contracts with various membership entities and other organizations, but these entities do not underwrite the offered insurance products. Discount amount varies in some states. One group discount applicable per policy. Coverage is individual. In New York a premium reduction may be available. GEICO may not be involved in a formal relationship with each organization; however, you still may qualify for a special discount based on your membership, employment or affiliation with those organizations. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, DC 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2022 GEICO. THE PERFECT FIT. The partnership with University of Washington and GEICO.

A Very Confetti Ending

New coach Kalen DeBoer leads the Huskies to a resounding Alamo Bowl victory over Texas to put a bow on a terrific Husky season

By Jon Marmor

By Jon Marmor

Under the steady hand of Kalen DeBoer (hoisting trophy), the Huskies made an incredible turnaround from a disappointing 2021 to finish 2022 with an 11-2 record and a No. 8 national ranking. With quarterback Michael Penix Jr. and other key players coming back next year, sights are set on a Pac-12 title.

When Kalen DeBoer was named the head coach of the Huskies just after Thanksgiving 2021, it didn’t take him long to say the Dawgs would give opponents headaches on both offense and defense. He then went out and led the Huskies to an 11-2 record and a convincing 27-20 victory over Texas and former Husky head coach Steve Sarkisian in the Alamo Bowl in San Antonio. Oh yeah, the game wasn’t nearly as close as the score might lead you to believe. In the postgame celebration, DeBoer honored his players and staff, who in one short season rebuilt the Dawgs after a 4-8 season and made the Huskies a Pac-12 powerhouse and a national story. “Tonight

was a culmination, I think, of everything that we’ve worked on, the things that we’ve tried to improve,” he said. “You saw our physicality, I think, take that next step, and finding a way to win is something that I think we’ve really emphasized. … We’re going to find a way to win. That refuse-to-lose mantra has been a piece of what we’ve talked about.”

Led by transfer quarterback Michael Penix Jr. (a school-record 4,641 yards passing, 31 touchdowns, 151.3 rating), the Huskies’ relentless offense averaged just shy of 40 points per game (second only to USC) and a league-leading 515 yards per game. These figures certainly aren’t

surprising, given DeBoer’s history creating offenses that can’t be stopped. On defense, the Huskies were nearly as solid, ranking third in scoring defense (26 points per game). Put those two sides together, and you can see why this team came within one victory of going to the Rose Bowl. Not a bad turnaround from 4-8 in such short time.

The Huskies’ hard work translated into something larger—a re-energized fan base that can’t wait for fall 2023.

Penix announced at the team banquet that he would return for 2023 instead of turning pro. That was followed by a number of the talented receivers saying they would join Penix back in Husky Stadium.

When you combine that with the seven-game winning streak the Huskies closed 2022 with, you can understand why Husky Stadium will definitely be the place to be next season.

22 UW MAGAZINE

ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS

GROWING TOGETHER

Each day is a chance to grow. BECU celebrates the opportunity to continue our partnership with the University of Washington and its Alumni Association. Together we spring into action to support and uplift communities across the Pacific Northwest.

Federally insured by NCUA. becu.org

The Way Ahead for Higher Ed

Facing an alarming decline in public confidence, colleges and universities are working together to restore trust

BY HANNELORE SUDERMANN ILLUSTRATION BY JOE ANDERSON

Higher education is in trouble. Colleges and universities across the country are facing a worrisome decline in public confidence. And that drop in trust can affect funding, community interactions and college enrollment.

A recent survey by New America, a left-leaning think tank, found that only about half of Americans believe colleges and universities are leading the country in a positive direction. Those who feel positively about the impact of the institutions dropped from 69% in 2020 to 55% in 2022. The survey also showed a strong partisan divide. Nearly three-quarters of the Democratic respondents said they believed colleges and universities have a positive effect, just 37% of the Republicans did. With both parties, though, the decline is significant.

According to the Gallup Organization, Americans are in a time of record low confidence across all institutions including all three branches of federal government, the media, the police, organized religion and the medical system. But over the decades, higher education has fared better than most.

Now news about topics like the high price of tuition, high student debt and legacy admissions at private schools are eroding public confidence. So have scandals like “Operation Varsity Blues,” a college admissions bribery scheme. And just last fall, college rankings came into question when the U.S. News & World Report was criticized for using faulty data and accused of prizing wealthier, private colleges and not performing objective evaluations. Now many schools, including the UW School of Law and the UW School of Medicine, have stopped participating in the magazine’s rankings program.

Education leaders around the country are working together to figure out what to do.

Over the years, the University of Washington has found ways to show how it benefits individual lives, communities and society as a whole while deepening its connections with its alumni and the communities of Washington.

In February, at a Council for Advancement and Support of

Education conference in Bellevue, UW President Ana Mari Cauce took the stage to discuss the issue. She was joined by Teresa Hutson, Microsoft’s corporate vice president for the Technology and Corporate Responsibility Group, and Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education and a former U.S. undersecretary of education.

Mitchell said he was already talking about the troubling trend of declining public trust five years ago. Today, the situation is worse. “The meter is going the wrong way,” he told the audience of higher education workers. “The American public has lost a lot of confidence over time.” In addition to a partisan split, focus groups are showing that political independents, a growing category, are also trending down, he added.

He pointed to a robust narrative feeding the unpopularity. People are saying that you don’t need to go to college anymore, and if you do, it will not pay off, he said. The narrative also suggests that college won’t help you do better at your job, and the kicker: “You’ll be brainwashed,” he said. “In a lot of ways, the problem with that narrative isn’t that it’s false. In each of those bits of the narrative, there’s a nugget of truth.”

Five years ago, the UW joined forces with Washington State University in a public campaign to reach families about the possibility and affordability of college. They called it “Yes, It’s Possible.” “The goal was to make it clear that you can attend college and you can graduate without a lot of debt,” said Cauce. The program’s site states that “no student should have their dreams denied because of their background and financial circumstances” and directs potential students and families to explore financial aid and grant opportunities at the state’s public colleges and universities and community and technical colleges.

Another of the UW’s pathways to raise public awareness and boost support for education came about in 2019, when UW and other Washington state colleges and universities worked alongside the business community to increase state support for scholarships. The resulting Washington College Grant has been the state’s

24 UW MAGAZINE

most significant investment in higher education in a decade.

The businesses, which included Microsoft and Amazon, asked the state to tax them for the purposes of developing a larger workforce and a stronger community in which to operate. Businesses need predictability, said Hutson of Microsoft. There is predictability in knowing this state is investing in the people who live here, who go to college here, she added.

But the secret ingredient in the legislative recipe was the alumni voice. More than 2,000 people, many of them Huskies, wrote to their legislators in favor of the new tax. Olympia heard from constituents in 48 of the state’s 49 legislative districts.

The Workforce Education Investment Act created the Washington College Grant to increase state grants for low- and middle-income families. Now members of families making $64,500 or less can get full tuition at any eligible in-state public college or university or comparable support at approved private college or technical training programs. In the last academic year, the grant has paid some or all of the tuition for more than 94,000

While polls show the public still sees college as a pathway to a better life, confidence in higher education has dipped in recent years. It could affect enrollment and public funds for research and student support. �he UW is working with other schools and the business community to communicate higher education’s value to the general public.

students—more than 14,000 of them at the UW. “We are so lucky in this state,” said Cauce. “We are one of the most affordable states in the country for students who want to go to private or public colleges and universities.”

Now all colleges and universities need to do more to communicate their value, said Cauce. “Kids start deciding that they’re not going to make it to college when they are in middle school.” Those in higher education need to reach them and their families with stories about the student experience and about the good work the schools are doing in their communities.

The UW and other schools are teaming up with institutions, businesses and key stakeholders through Discover the Next, an initiative funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and a joint project of the Council for Advancement and Support of Education, the American Council on Education and the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges. “We take for granted that higher education in this form will always be around,” said Cauce. “If we don’t change, we could disappear.”

SPRING 2023 25

Values are Our Currency

New NCAA rules mean student-athletes can benefit from revenue generated by use of their name, image and likeness. How the UW does it differently than the rest

BY JON MARMOR

�wo years ago, college sports were forever changed when the NCAA changed its policy prohibiting student-athletes from earning money for the use of their name, image and likeness (NIL). This opened a new world for the University of Washington’s student-athletes, coaches and administrators. The UW and Montlake Futures, the primary collective handling NIL deals for Husky student-athletes, have used the University’s values as the guiding light to deal with this new world of opportunities.

Under the NCAA’s new rules, student-athletes can be paid by third parties but not by universities, who are also restricted by NCAA rules from arranging and facilitating deals for student-athletes. These rule changes led to the creation of “collectives,” small organizations that are not officially affiliated with universities but deal directly with student-athletes and NIL activities. “We are building the plane while we fly it,” says Jamaal Walton, the UW’s senior associate athletic director in charge of sports administration and strategic initiatives.

While there have been stories of high-profile athletes (mostly football or men’s basketball players) jumping from one school to another because of a multimillion-dollar NIL deal, in reality that’s rare, UW athletics officials say. Also rare is the way the UW has undertaken NIL efforts in a direction different from most schools.

Montlake Futures is the primary NIL source for UW student-athletes. It is a lean-staffed, 501(c)(3) organization that seeks out and develops NIL opportunities. To date, it has funded nearly 200 deals and facilitated (that is, consulted on, for no charge) nearly 100 additional deals.

What differentiates Montlake Futures from many other collectives is that it is a nonprofit and does not receive a cut from the fundraising opportunities provided to Husky student-athletes. While individuals can reach out directly to student-athletes for NIL deals without the help of a collective, working with Montlake Futures gives them an advantage “because we can develop NIL opportunities that benefit our community,” says Emmy Armintrout, executive director of Montlake Futures.

Collectives such as Montlake Futures are not officially connected to the UW. “Our role is to provide a structure for the UW community to support NIL. We do so by raising tax-deductible donations and paying student-athletes to do NIL work for nonprofit organizations,” Armintrout explains. Studentathletes are not required to work with collectives; they can

find and develop their own deals through opendorse.com or serve as ambassadors for such brands as adidas, an official partner of the UW athletic department.

“I think it can be difficult for some people to wrap their heads around NIL and how it has (and will) change the landscape of college athletics,” says Patrick Crumb, ’88, a founding adviser to Montlake Futures and former board president of the UW Alumni Association. He is president of regional sports networks at Warner Bros. Discovery, AT&T SportsNet and ROOT Sports Networks. “But NIL is here to stay and in order for the UW to remain competitive, there must be NIL opportunities available for our student-athletes. That’s why we formed Montlake Futures—to provide UW student-athletes with the opportunity to receive compensation for their time and the value of their name, image and likeness. That having been said, it was always important to those of us in the founding group that we go about it the right way, in a way consistent with UW values.”

Montlake Futures has raised money or built awareness of such organizations as Seattle Children’s, Project Dawghouse (student-athlete housing subsidies near the UW campus), the Humane Society and the Hunger Intervention Program.

While the UW is not involved in creating or administering the deals with the student-athletes, it does play a critical role in providing education for student-athletes as well as support and mentoring from coaches and administrators. For instance, UW athletics administrators have met with players and coaches from all 22 sports programs to go over such topics as what they are interested in and what they value. Another area where the UW stands out is a partnership between the athletic department and the Foster School of Business. UW athletics and the Foster School announced a for-credit course—one of the first of its kind—dedicated to educating students on key name, image and license topics such as personal brand development and strategy, business and entrepreneurship, and opportunity evaluation. The goal of the course is not only to allow student-athletes to successfully navigate NIL but also to provide broader business education to any student interested in a sports or sports-adjacent career.

The information and education the UW provides is absolutely invaluable, given that Washington state has no state NIL law. “There is a lot of complexity to this,” Walton says. “What we can do is provide student-athletes the information and education so they can be successful in the deals they do decide to accept.”

Football players Devin Culp, Kristopher Moll, Giles Jackson and Alphonzo �uputala work at an event for the Hunger Intervention Program.

Women’s basketball players �rinity Oliver (left) and Hannah Stines enjoy some puppy love while lending a helping hand at the Seattle Humane Society.

Nineteen football players take part in an awareness campaign for the American Heart Association, “Go Red for Women.” Later, all 19 shared photos and information about women’s heart health with their social media audiences.

26 UW MAGAZINE

NIL AT A GLANCE

Student-athletes deal primarily with “collectives,” small organizations set up to connect them to fundraising opportunities. Montlake Futures is the primary collective for the UW, but other local collectives work with Husky student-athletes. The world of NIL is continually evolving. This is the most current information as University of Washington Magazine went to press in late February.

■ How can student-athletes cash in on NIL?

• Social media promotions and influencer activities

• Sale of autographs

• Starting their own business

• Appearance in TV or print advertisements

• Other endorsements of a third party

• Providing private sport lessons or running a camp or clinic

• Personal appearances

■ What makes the UW’s NIL efforts unique? The UW athletic department’s arrangement with the Foster School of Business to provide financial and business education to student-athletes

■ Can universities use NIL in recruiting prospective student-athletes?

The NCAA prohibits the use of NIL in recruiting

■ What makes Montlake Futures different than other collectives?

It is a nonprofit organization that does not take a cut of payments to student-athletes or charitable organizations

It raises money to fund NIL deals that benefit charitable organizations

■ Types of opportunities Montlake Futures has funded and the organization that benefitted:

Camps: ReJoyce Academy, Boys and Girls Club, Richmond Youth Football

Fundraiser Appearances: Seattle Children’s, Hunger Intervention Program, Treehouse, Make-a-Wish Foundation

Good will and Awareness-Generation

Appearances: Forgotten Children’s Fund, 4C Coalition

Marketing: Humane Society, American Heart Association, Big Brothers Big Sisters

More information: Gohuskies.com Montlakefutures.com

/

EMMA OTTOSEN / MONTLAKE

EMMA OTTOSEN / MONTLAKE

EVAN MORUD

MONTLAKE FUTURES

FUTURES

FUTURES

SPRING 2023 27

EMMA OTTOSEN / MONTLAKE FUTURES

Doreen Alhadeff shows off an antique key, which symbolizes the intention of Sephardic Jews to return to their native homeland of Spain. For 500 years, Sephardic Jews were banished from Spain. Alhadeff, who led the successful effort to have that policy overturned, became the first American Sephardic Jew to gain Spanish citizenship.

Knight Time

For five centuries, Sephardic Jews were kicked out of Spain—until Doreen Alhadeff of Seattle persuaded Spain to reverse course

BY DAVID VOLK PHOTOS BY RON WURZER

If Doreen Alhadeff

is any indication, you don’t have to wear armor, rescue damsels in distress or even slay dragons to be a knight. In fact, the 70-something Realtor from Seattle, who just became the most recent knight of the Order of Queen Isabella the Catholic, wasn’t alive in the Middle Ages, never jousted and probably never engaged in any crusades. Like many knights of yore, though, she has helped plenty of people in their quest to reclaim something that was stolen from them.

Their Spanish citizenship.

The crime may have occurred more than five centuries ago, when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella issued the Alhambra Decree, which led to the expulsion of thousands of Jews from Spain in 1492, but when Alhadeff and Jennifer McCullum talk about it, the incident sounds much more recent.

“When you grow up as a generation of a diasporic people or culture, the grief of the homeland you’ve lost gets passed down [along] with the beautiful traditions of your family,” says McCullum, the assistant director of the UW’s Sephardic Studies program.

The 500-year-old tragedy became more of a current news story when the Spanish Parliament passed a repatriation law in 2015, giving Alhadeff, McCullum and thousands of Sephardic Jews the world over a chance to regain their citizenship. Both women jumped at the chance. “I felt it was very important. I’ve always had a strong affinity to Spain; it seemed more than just a great place. I knew what it meant to me. It was something that had been taken away, and I wanted to take it back,” says Alhadeff, ’72, who holds a bachelor’s degree in Spanish from the UW. In 2016, she became the first American Sephardic Jew to gain Spanish citizenship after the country passed the law allowing repatriation.

The accomplishment was no small feat. In addition to meeting the requirements other applicants faced, Alhadeff also had to provide proof of her ancestral ties to the country and certification of those claims by a recognized Jewish community organization where she lived. Once her documents were in order, she had to have them translated into Spanish and travel to Spain to have them notarized. She also had a limited time

to do it. The law was initially set to expire in three years. After learning firsthand how involved the process was, Alhadeff decided to assist others who were following in her footsteps.

“I knew what it meant to me. I felt like I was this one person at the time who could help people get through the process,” she says. McCullum was one of many to benefit from Alhadeff’s expertise.

Not knowing where to turn, McCullum, a then-newcomer to Seattle, sought advice from Sephardic Studies Chair Devin Naar, who was able to provide evidence of her ancestry. He also told her, “The first call you have to make is to Doreen,” McCullum recalls. “She has truly been a confidante and a cheerleader. This process would not have been possible without her.”

To understand why Spanish citizenship is so important, a little explanation is in order. Jewish communities have existed across the globe. Often they are divided into two broad cultural and geographic groups. Ashkenazic Jews lived in Eastern and Central Europe and used Germanic-based Yiddish as a language that transcended borders. Sephardic Jews settled in southern Mediterranean countries like Spain, Portugal and later Turkey and Greece, and spoke Spanish-influenced Ladino.

During the Middle Ages, the Iberian Peninsula was a center for Jewish thought and culture under Muslim rule. For a brief period, it was also home to Europe’s largest Jewish population. Conditions changed as the Christians conquered what is now Spain. Jews were given an ultimatum in 1492: convert to Christianity or be expelled from Spain.

Many fled to other Mediterranean countries, including the Ottoman Empire (present-day Greece and Turkey). One of the next great migrations came 400 years later, as the Ottoman Empire collapsed in the early 20th century and many headed to the U.S. McCullum’s great-grandmother emigrated in 1915 to New York from Salonica, Greece, once home to the largest Sephardic community in the Mediterranean and the subject of a 2016 book by Naar. Alhadeff’s grandmother became the first Sephardic Jewish woman in Seattle in 1906 after leaving Istanbul.

In the years since, Seattle has become home to the country’s third-largest Sephardic population.

SPRING 2023 29

Jennifer McCullum, who works in the UW’s Sephardic Studies program, was told to seek Doreen Alhadeff for help when she wanted to apply for her own Spanish citizenship. After weathering some handwringing obstacles and then the pandemic, she finally got her paperwork approved. She is now waiting for her Spanish passport.

T he PATH to KNIGHTHOOD

If someone had told 19-year-old international student Alhadeff that she would be knighted for her efforts to help Sephardic Jews regain their Spanish citizenship, she says she never would have believed them. It’s not just the unlikelihood of the idea, it’s also because there was no evidence of Sephardic culture when she arrived in Madrid in 1969.

“The knowledge of Sephardic heritage at that time was not at all present. People weren’t aware of it at all,” she said in a 2021 episode of the podcast “Power of Place.” Even so, Alhadeff said she felt an immediate connection to the culture and the language. It was the first of many trips to a country where she feels increasingly at home. Of course, it helps that she has also worked to forge bonds between Seattle and the international Sephardic community. After helping Madrid hold Erensya, an international Sephardic heritage conference, she persuaded the organization to hold a meeting in Seattle. She co-founded the Seattle Sephardic Network, which helps people find cultural resources in the Pacific Northwest. She was also named U.S. ambassador to Red de Juderias of Spain, which supports and publicizes a group of cities within Spain with Sephardic heritage.

She was in Madrid when Spain’s Parliament took up the issue of Sephardic repatriation. She wasn’t in the country when it came up for a vote, but she got up early just to watch its passage and started her application shortly after. She became a citizen within a year.

Once she dedicated herself to helping other applicants, she did more than answer queries from all over the world. She also helped make the process easier by lobbying for changes. For example, she pointed to the law’s requirement that all applicants take a language test and a cultural test, both written in modern Spanish, which is much different than Ladino.

“There were a few of us that said, ‘Nobody’s going to go learn a language at this point, and for many of those over 65, the language that they knew, that they grew up with, wasn’t current-day Spanish, it was Ladino.’ So, it was a little bit of a problem,” she says.

The government changed the rule, limiting the requirement to those over 18 and under 70, which also allowed Alhadeff to secure citizenship for her three grandchildren. In addition, applicants were also required to get a Sephardic authority in the country. Alhadeff helped her local synagogue, Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, get recognition from Spain to be an official signatory on such letters.

In McCullum’s case, Alhadeff’s advice made the biggest difference. “At every step, whether it was pointing me in the right direction, commiserating with me over three years without a word, text messages saying ‘Have you heard anything?’ her encouragement and faith in me meant everything,” McCullum recalls.

Like Alhadeff, McCullum was excited about the law. “I think it’s an incredible opportunity to offer repatriation for a 500-yearold injustice. How could I not pursue this as a way to return home to a place that my family had been told, ‘You can no longer be here’ 500 years ago?” McCullum says.

Unlike Alhadeff, McCullum faced a rockier road. She loved the part of the process where she learned more about her family and her grandmother, but she was not thrilled about being a victim of unfortunate timing. She began the process in 2016 and flew to Malaga in May 2018 to have her documents notarized and submitted. She was told that the Ministry of Justice would make a decision within a year. But then the COVID-19 pandemic shut everything down. Her application was rejected three years later.

“It was devastating,” she says. “It feels like the wound is still fresh. It was the closest I have come in this process to feel what my ancestors must have felt in being told you are no longer welcome in a place that is your home, in a place you know is your birthright.” She was rejected because she was missing a document that became a requirement after she applied. She was able to resubmit, but worried time would run out before her application would be reconsidered. So she sued the Spanish government. She got her citizenship the weekend of July 2, 2021. “I’m not sure it will feel really real until I have that passport in my hand,” McCullum says.

Now that they are Spanish citizens, they are eligible for free health care in Spain, they can vote in elections, apply for jobs throughout the European Union and even open a bank account. It also provides an escape should the political situation in the U.S. worsen.

“Years ago,” Alhadeff says, “when I was working in Madrid, a French gentleman who was getting his citizenship said something to my husband that sort of struck us. … Every Jew should have another place to go. They just never know.”

Alhadeff didn’t seek out knighthood. Instead, she was nominated by Luis Fernando Esteban Bernáldez, the honorary consul for Spain from Washington and Oregon, in honor of her “demonstrated loyalty in furthering Spain’s relations with the Americas.” He did so in recognition of her efforts to help Sephardic Jews in Seattle and throughout the U.S. acquire Spanish citizenship.

The knighthood did not come with a suit of armor, family seal or coat of arms, but it did come with a lapel pin and small medal. It may have also come with a bit of baggage, because the order is named for Queen Isabella, one of the rulers who ordered the Jews expelled from Spain.

But instead of being bothered, Alhadeff said she is encouraged by the name. “I think that’s the most important part of this because this is obviously centuries and centuries, and people still relate to her as being one of the responsible parties. I just think it shows unbelievable change with people working at it and wanting it, that change can come about,” she says. “I think that’s huge and if I can represent that, then that kind of change is possible.” As an example, she pointed to the change in attitude between her first trip to Madrid in 1969 and today.

“I see the difference from when I was there [first], because there was no awareness of the heritage of the Sephardic history. They didn’t talk about it. It wasn’t discussed, it wasn’t taught. Now organizations are speaking out about Sephardic heritage, restoring Sephardic sites, as well as teaching it in school. Things have progressed. It’s been very, very exciting, actually.

“That’s been quite a journey for me, but it’s also been quite a journey for Spain. It’s the odd occasion that I go [there] now that somebody doesn’t want to talk about it, they want to know what’s going on. Oftentimes they are convinced, or they think that they probably have some Sephardic heritage in their background.”

Now that the repatriation window has closed, Alhadeff still gets questions, but they are about her knighthood. Some people have asked what she gets for being a knight, others asked if a sword was used in her ceremony. Perhaps the most frequent question is about its significance.

Since it’s an honorary title, the knighthood doesn’t come with any privileges. Not even free admission to heritage sites or a discount at the Spanish equivalent of Denny’s. No actual swords were used in her October knighting ceremony at the Meydenbauer Center in downtown Bellevue. Instead, there were speeches and a musical performance by noted Spanish musician Paco Diez, who sang in Ladino and Castilian.

As for the significance of the honor, she says, “It just means that I’ve been recognized for the work that I’ve done. I still see it as ongoing. I hope I’m not done.”

SPRING 2023 31

When you grow up as a generation of a diasporic people or culture, the grief of the homeland you’ve lost gets passed down.

AHEAD OF THE GAME

ONE ATHLETE JOURNEYS FROM INJURY TO RECOVERY WITH THE HELP OF SPORTS MEDICINE EXPERTS AT THE UW

By JAMIE SWENSON Photos by MARK STONE

Ella May Powell was running drills with her teammates when something popped in her left knee—a different sensation than any injury she’d experienced before. Panic set in.

It was early in the fall of 2020, and the UW volleyball setter had been practicing with her teammates. The familiar thuds of volleyballs and squeaks of shoes echoed throughout the otherwise empty Alaska Airlines Arena.

The team hadn’t practiced much over the spring and summer because of the COVID-19 pandemic and they were thrilled to finally be back on the court together. In Powell’s freshman season, the Huskies had made it to the Sweet Sixteen round of the NCAA tournament. In her sophomore year, they advanced to the Elite Eight. Powell, at the time a junior and one of the best setters in the country, had high hopes for the season ahead.

But on a routine play that day, she backpedaled and twisted to her right to set the ball for a teammate and then came the alarming pop. She hopped awkwardly to the side of the court, tried to take a couple of steps and then sat down, stunned. Tears welled in her eyes. Jennifer Stueckle, the team’s athletic trainer, rushed to her side.

“I wasn’t crying because it hurt,” says Powell. “I was terrified because I knew something was wrong.” An MRI would confirm her worst fears: She had torn her medial meniscus. It would

32 UW MAGAZINE

Ella May Powell, star setter for the Husky volleyball team, nearly missed her junior season because of a knee injury. With the help of UW Medicine doctors in the Sports Medicine Center and a months-long recovery program, she wrapped up her record-setting college career this winter.

SPRING 2023 33

require surgery, and she wasn’t sure when she would play again.

Luckily for Powell, her treatment and recovery were in the hands of a tight-knit team—including UW Medicine’s Dr. John O’Kane, UW Athletics medical director and head team physician; Dr. Mia Hagen, UW Athletics team physician, orthopedic surgeon and surgical director of UW Medicine’s Sports Medicine Center at Husky Stadium; and Stueckle, an associate athletic trainer for volleyball and beach volleyball.

As a field, sports medicine focuses on treating activity-related injuries. And the Seattle area—with one of the most physically active populations in the U.S.—boasts a wealth of resources for those seeking treatment. Among them is the Sports Medicine Center at Husky Stadium, which benefits from what O’Kane calls a triple threat of clinicians: those who serve patients, teach at the UW School of Medicine, and do research to keep athletes safe and healthy—now, and far beyond any amateur or professional career they may have.

UW Medicine’s sports medicine team serves people of all ages and abilities at several locations around Seattle, but UW athletes are most familiar with the Sports Medicine Center, a 30,000-square-foot facility that opened in 2013. Some of the staff also work as team physicians for the Huskies, Seattle Seahawks, OL Reign (the city’s professional women’s soccer club) and Seattle Seawolves (Seattle’s professional men’s rugby team), as well as the Seattle Marathon and several public high schools. The center and its staff also serve tens of thousands of members of the community every year.

O’Kane came to the UW in 1993 for his medical residency, followed by a fellowship. He is now a UW School of Medicine professor and head team physician for the Huskies. He says one of the center’s strengths is its location in Husky Stadium. “We have a world-class medical center literally across the street,” he says, referring to UW Medical Center’s Montlake location. “We have top-quality X-ray, ultrasound and MRI. It doesn’t matter what you need medically. It’s right here because of that co-location.”

Another of the sports center’s strengths, says O’Kane, is how the hospital extends into the training room—every day, a sports medicine physician visits the training room, which is connected to Alaska Airlines Arena and Husky Stadium by hallways and tunnels. After her injury, Powell was evaluated by the on-call physician. A few days later, she returned for an MRI.