38 minute read

Architecture

ARCT5502 INDEPENDENT DESIGN RESEARCH Unit coordinator: Dr Kate Hislop Supervisor: Dr Nigel Westbrook PETER MILLIGAN

The proposal uses primal forms and recognisable architectural language to construct an order that is both familiar and contradictory. This is intended to initiate a gap or slippage in understanding, encouraging the occupant to use their imagination to reconcile what is incoherent or unfamiliar. It seeks to open a dialogue between the inhabitant and the building, allowing them the opportunity to create their own meaning from their experience.

Image: Exterior perspective.

ARCT5101 ARCHITECTURE STUDIO Unit and Studio coordinator: Dr Nigel Westbrook ‘SOD II’

JESSICA LEIB

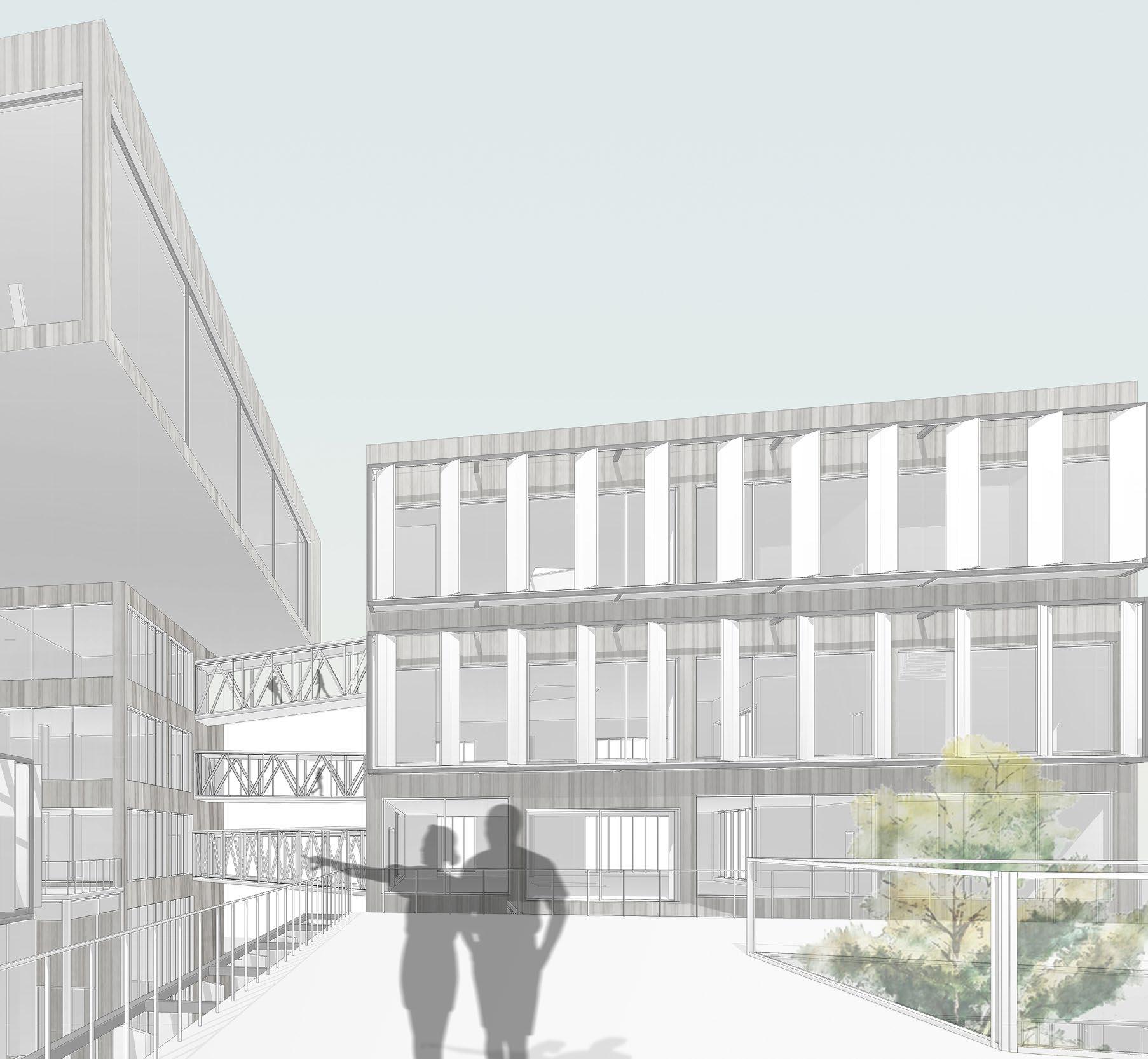

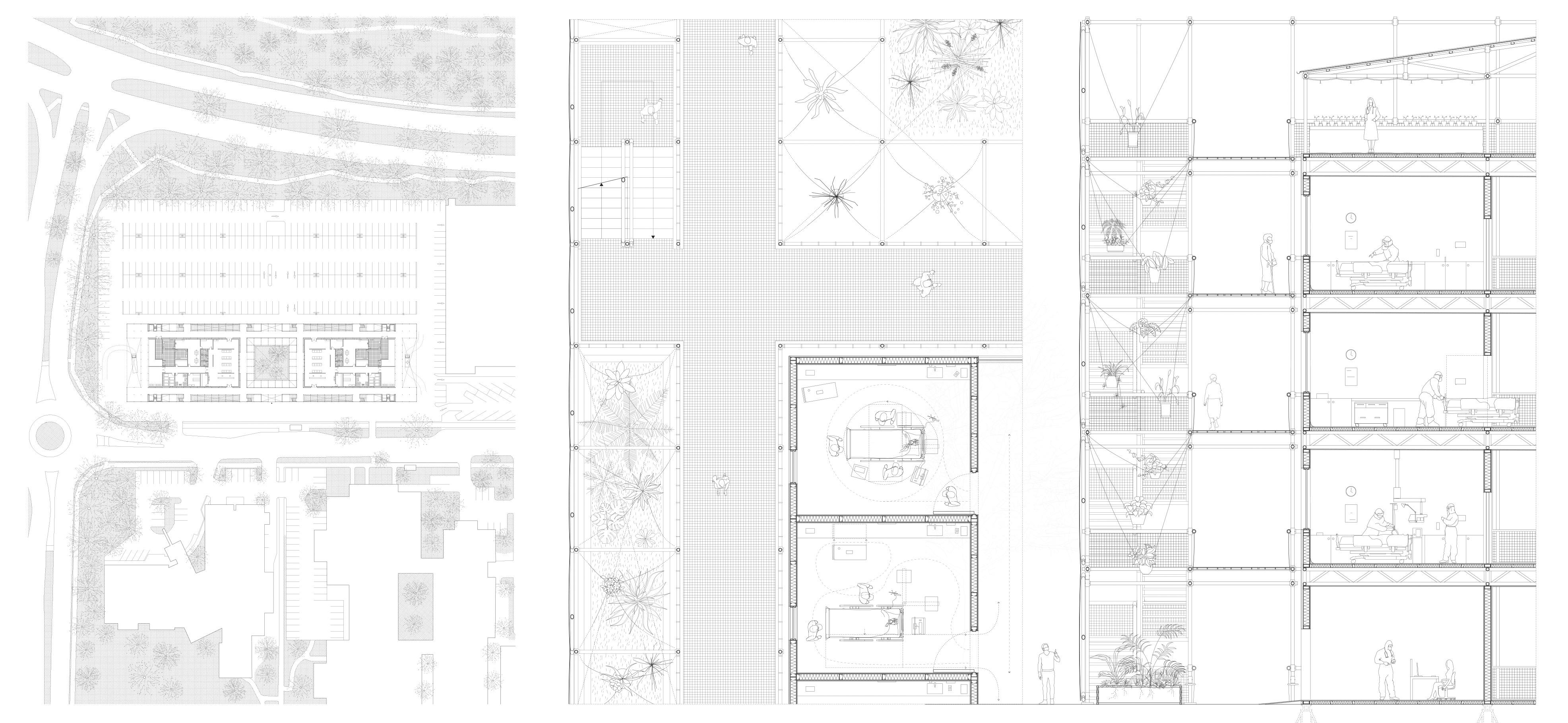

The brief for this project was to relocate the design school on to the main campus, finding a viable location that facilitates connections with the neighbouring disciplines, whilst fostering interactions of students from multiple areas of study.

Through a campus site analysis, the Reid Library car park proved to have the most potential to achieve the aims stated above, whilst also possessing the ability to create an iconic design school that redefines the image of UWA.

The design concept for the new school of design is to maintain the existing connections and circulation on site, whilst maximises the amount of possible connections within the buildings and to the surrounding disciplines. This concept is based off MATT Architecture.

In order to create the most connections possible, the school is isolated into buildings of specific programmatic space, and connected back together with the use of ramps, roof top spaces and bridges to achieve a hyper-connective school of design.

Image: Isometric section.

ARCT5101 ARCHITECTURE STUDIO Unit coordinator: Dr Nigel Westbrook Studio coordinator: Dr Daniel Grinceri ‘Intervention at the Border’ HAE YUN JUNG

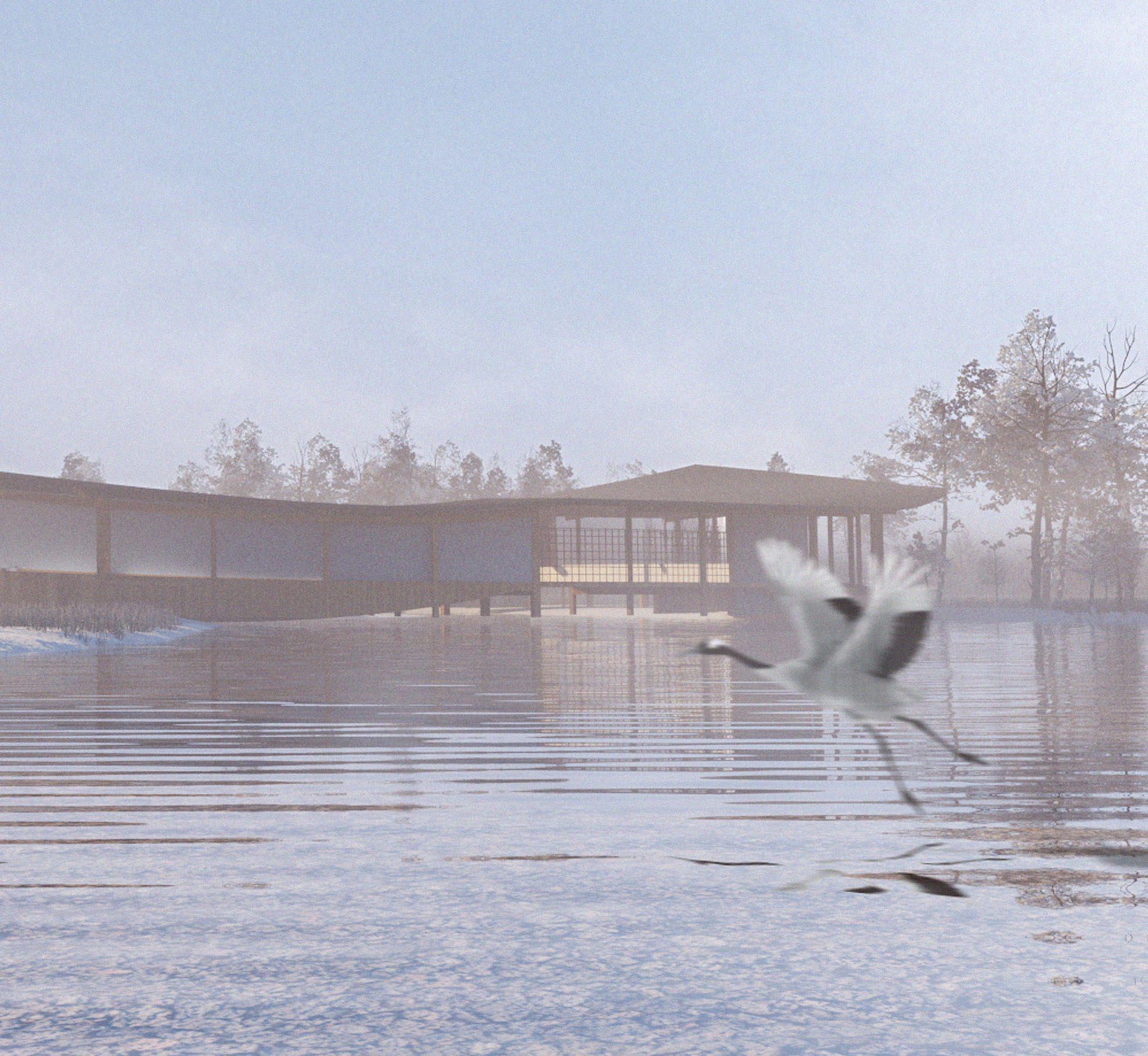

Since the beginning of the most recent century, Korea has not been unfamiliar to the dividing effects of war, international militia, and foreign occupation. A scar is found today in both North and South Korea marked by disagreements in ruling politics, which are further enhanced from a history of war. At the human level, this scar is formed from their separation of families, homes, culture, and the natural land with the hope that they may be united again. Although one form – a conservation centre – made present in the DMZ may not solve the divide caused from this deep and complex political, economical and social issues, it hopes to ask if there are possible connections between the two Koreas by some common traditional ideology that is rooted in their culture of balance in living, understanding, respecting, and thus connecting to their land, flora, and fauna that they have lived with for generations. For this project, all its intent may be summarised by the words of Hall Healy, the coordinator of International Crane Foundation:

“...the two Koreas to conserve the DMZ could improve prospects for reunification... it would help people to come to consensus on a mutually-advantageous project.”

The DMZ Conservation Centre will formally function as a crane conservation centre functional for eco-tourism and providing the first for of wildlife protection in Korea’s DMZ with expected military informants and security given its context. Furthermore, the building will function as an education centre for its visitors via an exhibit providing information on the significance of the cranes in nature, culture, their early life, mating rituals, diet, migration habits, and nesting. The building’s circular form also provides natural barriers from external elements allowing the space for an artificial feeding ground during sub-zero winters.

Image: North Korea’s Observation Deck.

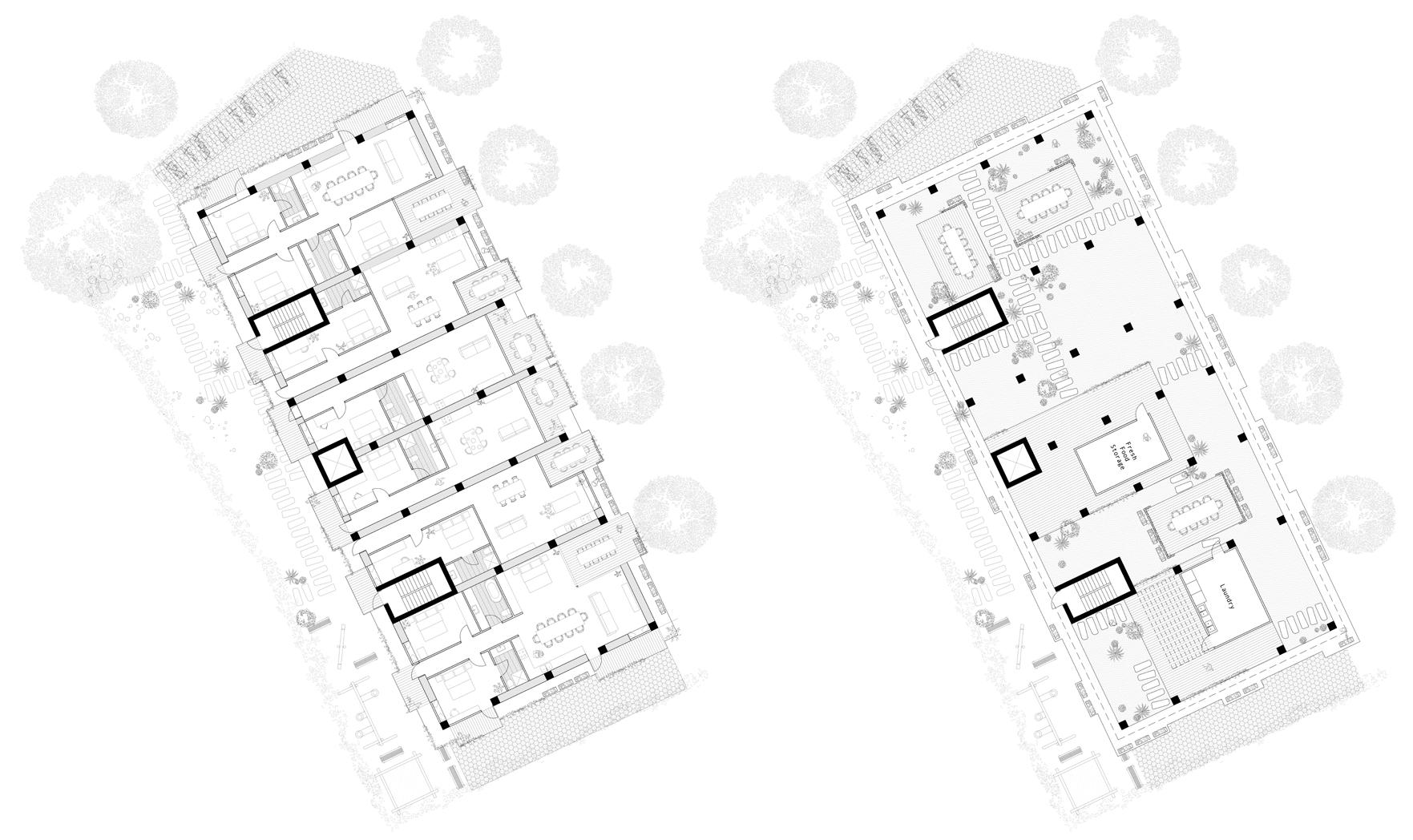

ARCT5102 ARCHITECTURE STUDIO 2 Unit coordinator: Dr Nigel Westbrook Studio coordinator: Dr Nicoletta Pizzuti ‘Adaptive Reuse’ PETER TIBBITT

The Terminus Hotel stands abandoned and unused on the corner of a quiet street in West End of Fremantle. Through detailed documentation and analysis of the existing building and its context this project aims to bring life back into not only the building itself but a part of Fremantle that has lost the vibrance and diversity that once kept the streets alive with activity. Today, Fremantle’s activity ebbs and flows as people emerge and retreat to the surrounding suburbs. To sustain life and vibrancy, further opportunities to reside within the bounds of the city centre are needed. This project proposes to sensitively restore and reuse the Terminus Hotel, which will house a combination of residential, commercial and retail. An underused carpark to the rear of the terminus provides opportunity for a new addition that responds to the existing building the side street and the potential for diversity and activity at the pedestrian scale.

Withdrawn from the street frontage, through a relatively transparent intervention that aims to carry some of the characteristics of a typical street elevation in Fremantle, the new addition is arranged around a central void that breaks down the solid nature of the city block providing relief from the current linear nature of movement and activity. Surrounding the courtyard, the new addition houses further residences, a café and a convenience store providing the necessary amenities for the increase in residential tenancies.

A muted material palette and a focus on quality of light, cross-ventilation and quality of space intends to create harmony between the old and the new without replicating tradition. The addition takes cues from, and responds to, the existing surrounding buildings helping to preserve, celebrate and revive the old while introducing a new language and use that intends to reactivate the West End.

Image: West elevation and courtyard section.

ARCT5101 ARCHITECTURE STUDIO 1 Unit coordinator: Dr Nigel Westbrook Studio coordinators: Kukame McPierzie & Kristen DiGregorio ‘Perth City Campus’ ELAINE ONG

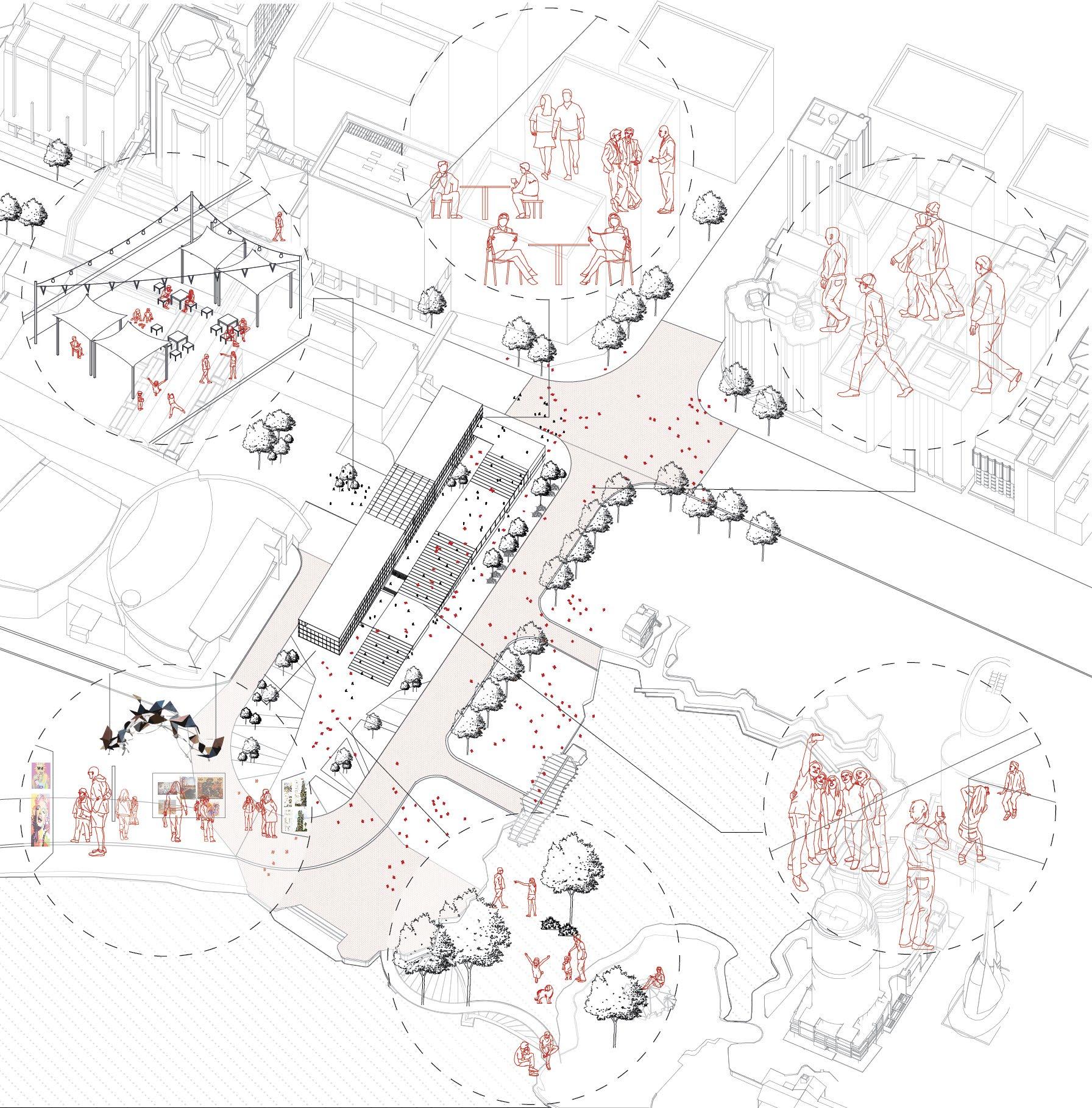

The PSODWA is a proposal that looks at developing a design school in the city with the emphasis of integrating separate functions to be housed under one roof. Located in a central area to the Perth CBD, and along the edge of Swan River across from Elizabeth Quay, the project is seen as a catalyst for the reinvigoration of Perth. The design proposal aims to integrate student collaboration, engage with the public, and connect to Elizabeth Quay and the surrounding streetscape.

The school aims to allow two separate functions to co-exist under one roof. This is done by integrating the public to interact and have a place in the building as part of a large urban dwelling. The roof of the building block is designed in such a way that allows the public to interact with the building and be a part of it. Retail shops, cafes and lounge areas are also part of the design to allow the general public to access and utilise these spaces.

Greenspaces are also integrated into the design to continue the green landscape from the busport and have a continued connection throughout the city all the way across to Kings Park on one end, and the Supreme Court Gardens on the other. The greenspace is also introduced as a part of reactivating the green space at the busport, which is connected to the building.

Connection is the main component of the design proposal. A pedestrian road system is introduced to propose a friendly and safe environment around the site, providing a connection to Elizabeth Quay. The second design intent for this project is collaboration. The design school is intended to house a living, breathing central collaboration space for its patrons. Lastly, the project also aims to play a large part of the city’s revitalisation process. In more ways than one, the proposal revolves around the idea of connection, and similarly also incites a process of revitalisation. Bringing forth a space that is beyond art and design, but also inviting the ideas of creating a new culture for society.

Image: Axonometric perspective.

ARCT5101 ARCHITECTURE STUDIO Unit coordinator: Dr Nigel Westbrook Studio coordinator: Dr Kate Hislop ‘Suburban Speculations’ BRADLEY MILLIS

Our city has a huge number of garages. This is a legacy of the 20th century technology of the private car, which helped produce the city of today where we rarely live and work in the same place and are heavily dependent on private vehicles to get around. 21st century tech is here in the form of digital communication, sharing economies, and technology that allows for mass communication. Now our digital neighbours can supply us with rideshare, shopping opportunities, and community, while digital communication allows us to work with ease while physically separate. This gives us an opportunity to transform the city from 20th century urbanism (discrete places for shopping, living, and work) to 21st century urbanism where technology allows the functions of the city to be decentralised. This creates the possibility of making the city different to how it was in the past – so it can work better for us.

Garages across Perth are a useful vehicle for this transition. As communication and transportation technologies (and the COVID catalyst) make cars less necessary, garages could be repurposed by residents to fulfil needs not currently being met in their suburbs, with varied possibilities: shared office spaces for workers who want in-person connection but a reduced commute, classrooms leased to schools or universities, self-contained dwellings for a renter or a family member, or commercial kitchens for new food businesses retrofitted into areas that currently contain residences only.

This form of ‘bottom-up’, fine-grained urbanism accelerates Perth’s evolution to a 21st century poly-nodal city, creating richer places and extending responsibility for building the city to its citizens.

Image: Map of potential redistribution of city functions through owner-generated garage adaptation.

ARCT5101 ARCHITECTURE STUDIO Unit coordinator: Dr Nigel Westbrook Studio coordinator: Shan He ‘SOD II’ CHENZI JI

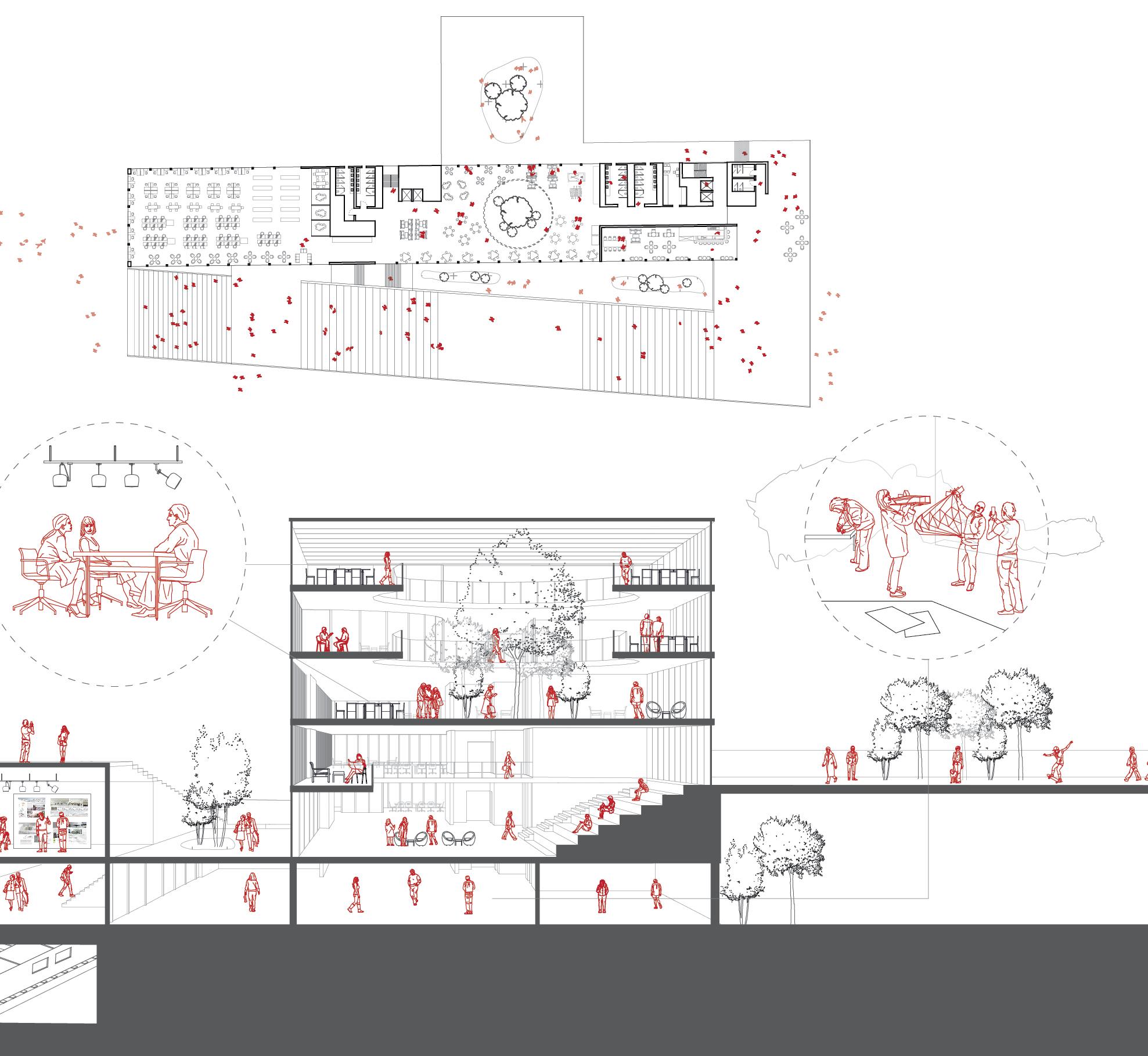

This project looks at developing a new building for the School of Design at UWA with an emphasis on sustainable and functional design strategies. The existing building was first constructed as the Nedlands Secondary Teachers’ College in 1969. The current facilities are not suited to the needs of the students and the staff, and lack connection to public areas. Therefore, this project aspires to create a desirable learning environment for the current and future needs of the design education.

SPACE DIVERSITY - The concept for this project was mainly driven by the desire to create a diversity of space, including varied teaching space, varied social space and different entrances. These diverse spaces achieve different scales through different column networks, which are independent of each other and have minimise impact on the existing structure.

SUSTAINABILITY - Retaining most of the existing space and structure, maximise existing resources and minimise the demolition costs. Combined with the use of double skin facade, the new School of Design aims to become the beacon of ecofriendly building in UWA.

SOCIAL INTERACTIONS - The current buildings do not encourage social interactions within the school. In this project the corridor is not only the connection of different spaces, but also the most important part of the social space. It’s also the missing part of the existing building. The corridor surrounds the courtyard, with an open environment and a wide view, where people can walk or stay and have a positive interaction space.

Image: Perspective.

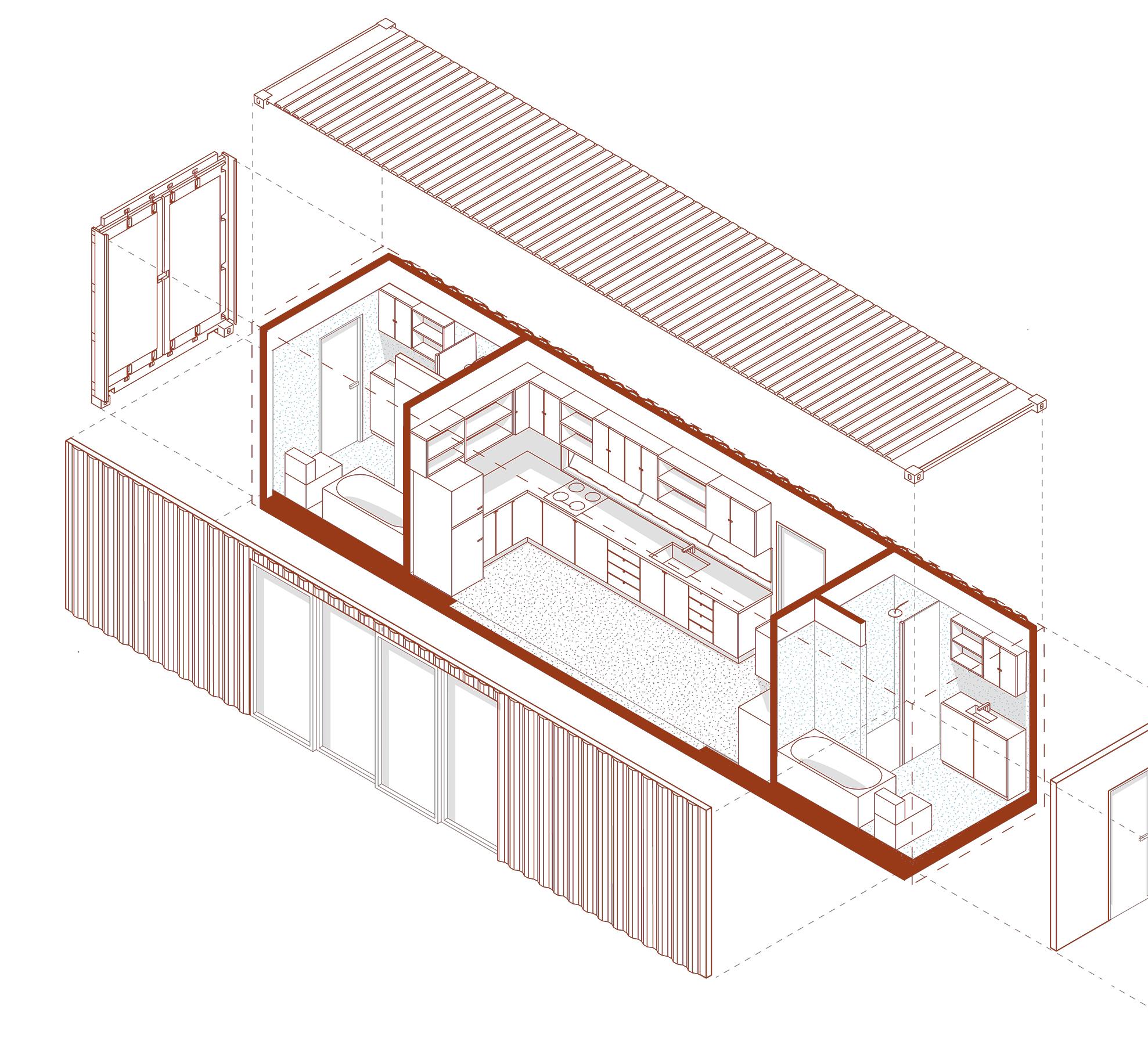

ARCT5201 DETAILED DESIGN STUDIO Unit coordinator: Dr Nigel Westbrook Studio coordinator: Richard Simpson ‘CORE’ NICHOLAS THUYS

Type A is intended as an initial starting point in developing a culturally & contextually sensitive housing typology for remote indigenous communities; striving to move away from established conventions or mainstream housing types. The design builds on the works of Glenn Murcutt and Troppo, specifically ideas around parasol rooves, internal pavilions unenclosed volumes, ventilation screening, operable wall panels and spatial conditioning.

The project consists of a parasol roof flying over the raised floor platform. To one side are a series of bedrooms, also intended to house whole family units and contain their living functions. To the other side is the service core, consisting of a pre-fabricated unit built around a 40ft high cube shipping container. In between is a large, open multipurpose communal area, which can be inhabited as desired, or divided into further informal living areas.

Utilising timber and steel, the primary structure consists of a regular post and beam arrangement, with internal room divisions acting as separate ‘pods’ which do not extend to roof height, allowing cross ventilation and large overhead spaces above the inhabitable areas.

Spatial planning uses non-structural blade walls to divide internal volume. Responding to cultural requirements, space is divided into areas for discrete family groups as well as single-sex rooms, also functioning as spare rooms accommodating fluctuating inhabitants throughout the seasons. The core holds a central kitchen with gendered bathrooms at each end, screened by timber battens for shading and privacy. The container’s outer skin provides weatherproofing.

Overall planning is intended to be flexible and able to accommodate a range of uses. Robust materials are specified to reduce maintenance requirements and ensure the integrity of the core and structure during transport. The typology is intended to be repeatable, pre-fabricated, and mass-produced, and act as a basis for further development and distilling into a housing typology that is relevant to its inhabitants.

Image: Prefabricated services core + shipping container – exploded isometric.

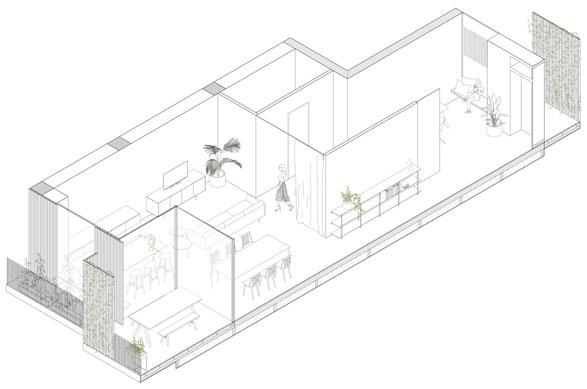

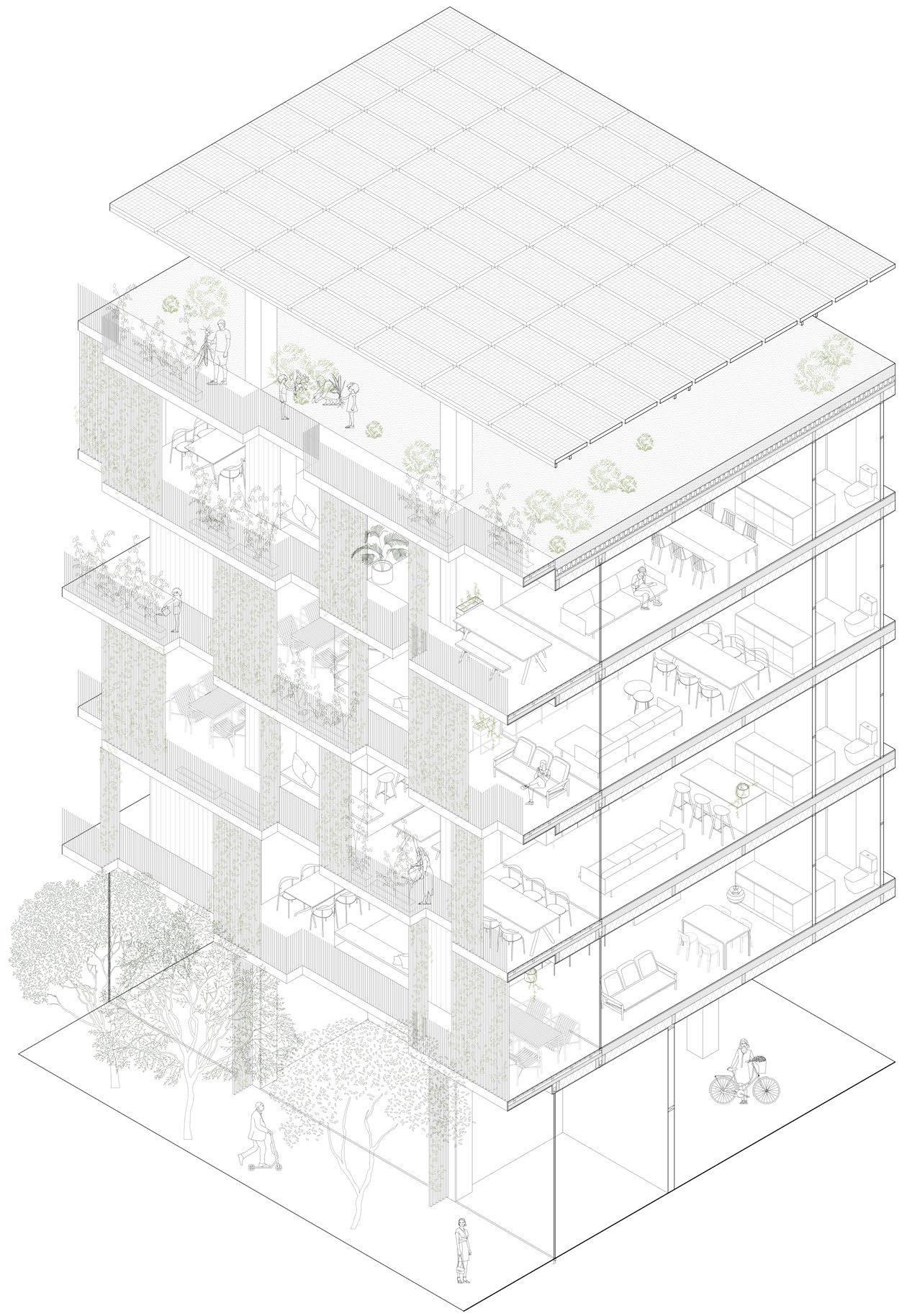

Tackling climate change requires urgent action if society hopes to reverse the current estimates of our world being capable of sustaining only 0.5–1 billion people, that is, around 7 billion people less than today. The building industry is responsible for 50% of fossil fuels used in the developed countries, consisting of both embodied and operational energy. This project studies the means of achieving a carbon positive design, meaning a building that produces more energy than it consumes during its lifetime.

Firstly, the embodied energy is minimised through the use of renewable materials that sequester carbon and reduce the size of foundations due to the lighter weight of the structure. Secondly, the operational energy is reduced by mainly focusing on the heating and cooling of the building. This is done through low form factor (minimising the surface area), high R-values for minimising conduction (heat gain/ loss), having dual-aspect apartments for cross-ventilation (natural cooling), multiple shading devices (less heat gain in summer), as well as having all communal, service and circulation areas outside, again reducing space conditioning, lighting requirements during daytime as well as mechanical ventilation. Lastly, the remaining emissions are then offset with an on-site energy production, generating around half of the energy for its occupants and returning half back to the grid. Further principles to aid the regenerative design include biophilic design, water harvesting, green roofs and gardens for improved biodiversity, space adaptability, maximising the plot ratio, having multiple spaces for food production, composting facilities as well as promoting the use of bicycles.

Image: Detailed isometric section.

b b

a a

a

b a

b

The West Australian Re-Constructivist (WARC) involves the application of constructivist design principles for the revival of ‘lost heritage’. With fated ever-growing urbanisation it is necessary to re-adapt and re-use pre-existing buildings to counter the waste generation that is today’s society. The climate crisis is at our door, the time to act is now. The WARC movement aims to reconstruct and re-use buildings (that are slowly vanishing to decay), designing in potential for future adaptation and change.

This project, a test case for WARC, focuses on the Fremantle Power Station as a source of materials and design language. Closely linked to the heart of the public, the deconstruction and re-siting of such a project would likely receive negative comments, however, the role of the WARC is to provide a revival of heritage in dialogue with an urgent need for a zero-carbon built environment, a controversial topic on anyone’s agenda. Through understanding the current climate crisis and the ability to re-construct and re-use existing buildings this project hopes to create a building that is permanent yet stagnant, mobile yet stationary, historic and also relevant to current and future needs.

To counter excessive amounts of embodied carbon this project heavily focuses on the recycling elements of the Fremantle Power Station, in particular the steel framework, and brickwork. New materials are used in the construction of prefabricated apartments placed into the steel framework providing the option of removal or addition according to the economic climate. Each apartment is wrapped in a plastic skin recycled from high-density polyethylene (HDPE – the most common recyclable plastic). The resulting effect is a translucent hazy skin that slows diffuse sunlight and silhouettes to seep into the interior. This project can be permanent until needed elsewhere.

Two ideals are embodied in this project: a new-found connection encompassing past, present, and future as one; and comment on the somewhat stagnant nature of architecture that goes unnoticed in such a fast-paced rapid society.

Image: Sectional perspective.

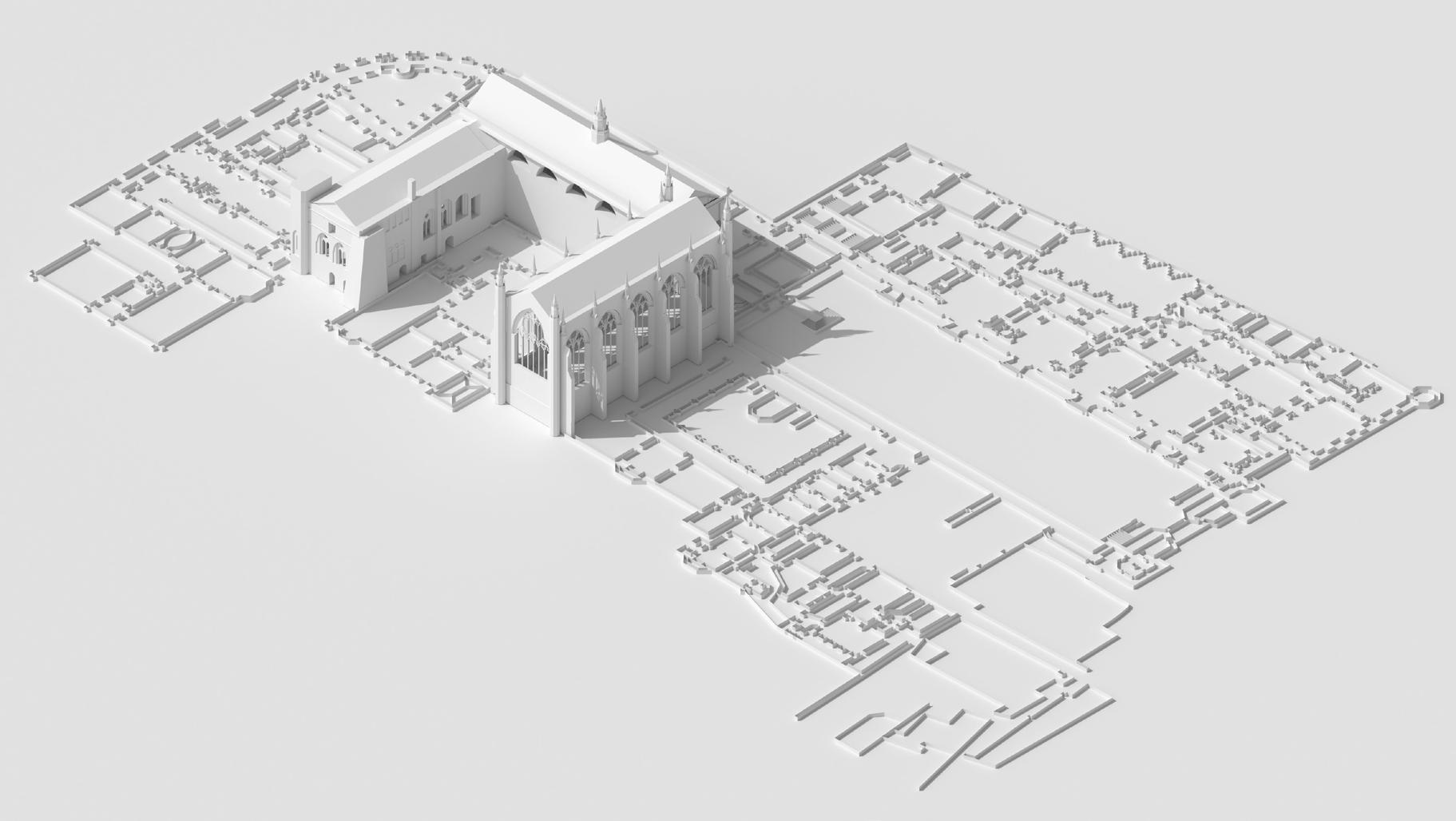

ARCT5529 FORENSIC ARCHITECTURE Unit coordinator: Dr Nigel Westbrook OLIVER HILL

The terrible fire which engulfed the old Palace of Westminster in 1834 was a turning point in the history of Parliament and of London. Until recently, however, it was a largely forgotten catastrophe. Over the years previous to the disaster, many designers expressed the potential dangers of fire within the palace as no fire stops or party walls were present in the building to slow the progress of a fire. One fateful day on October 16th 1834, the long overdue disaster occurred. The cause of the fire was due to the careless act and unsupervised task of the burning of tally sticks. This simple act caused one of the most significant blazes in centuries.

The three main structures lost in the fire consisted of the Painted Chamber, House of Lords and St Stephen’s Chapel. St Stephen’s Chapel was a gem that was lost, its ornamental beauty and intricate interior detail separates it from the chapels of its time. The Painted Chamber was a forgotten national treasure that was unveiled after the fire struck. Before the fire it was known as the King’s Chamber and was used as a private apartment. The fires blazed through and destroyed the walls that covered up what once was the painted chamber, leaving in its destruction the memories of the past - a chamber full of art. The House of Lords was a distinct element of parliament and was important in the establishment of the functionality of what we know parliament as today. Three distinctly different elements to what was once one unified structure. My aim is to reconstruct as much of these three structures as possible, exploring the different phases they passed through in time. I hope to give new life to lost memories of a historic structure and uncover forgotten moments of the past.

Image: Interior perspective of St Stephens Chapel.

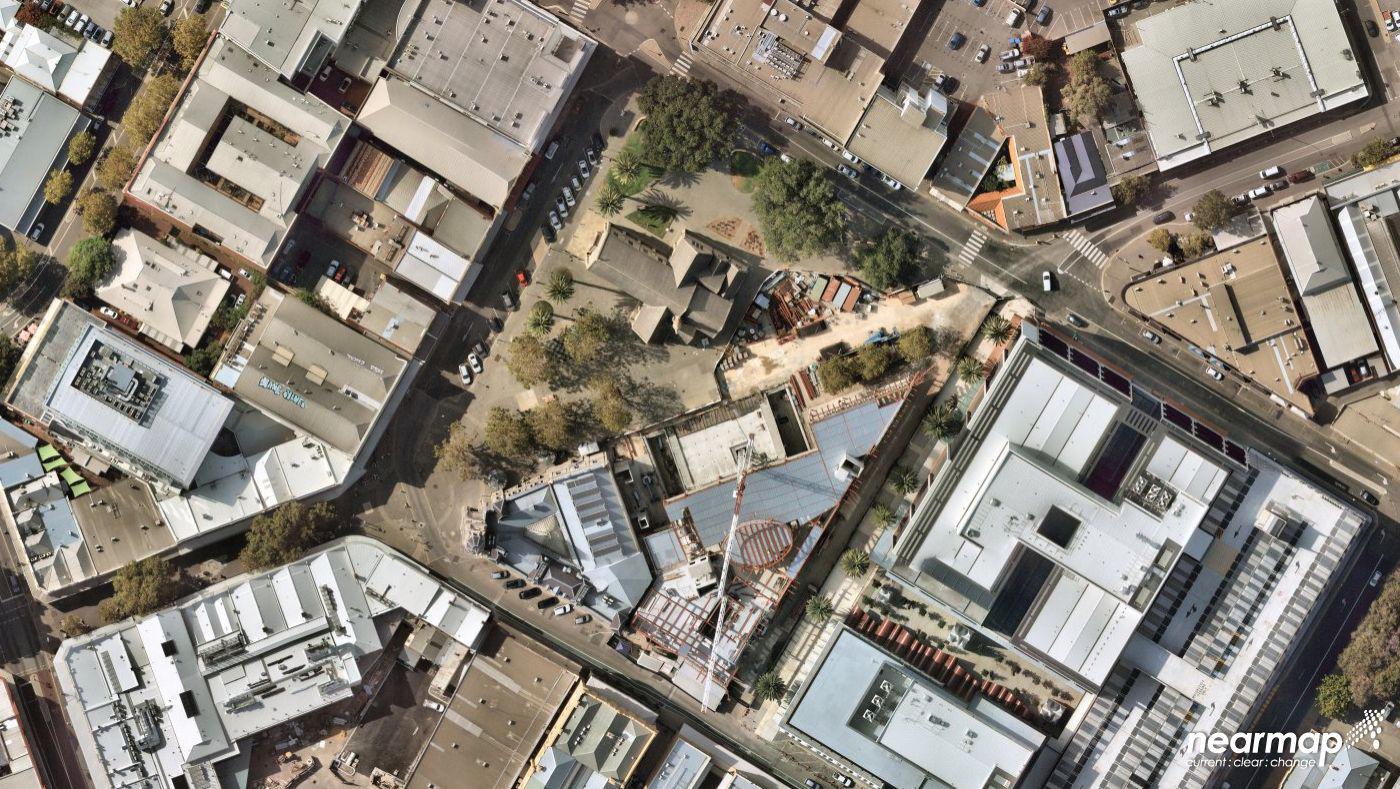

ARCT5505 CONSERVATION IN CULTURAL LANDSCAPES, HISTORIC TOWNS AND URBAN PRECINCTS Unit coordinator: Dr Ingrid van Bremen Teaching Assistant: Alana Jennings SAMANTHA DYE

REQUIREMENT 3.

Reconsider the new civic offices to better compliment the Town Hall; avoid new developments that overtake it.

REQUIREMENT 5.

Retain and enhance the defining townscape, in the Square and in the streets bordering the Square, especially Adelaide and William Streets, of two and three- storey to four-storey (not more) with shop fronts at ground level, consider only new buildings that fit with the High Street architectural character, pediments and parapet skylines. Prefer rounded or truncated corners to buildings, especially at street intersections. Avoid sharp or acute angle corners. As previously discussed in addressing preceding Requirements and elaborated in Significance of Conservation Plan 2020, the combination of townscape qualities of the buildings and landscape, the principal visual and planning of High Street, which are enhanced by the two historic buildings, and the architectural character of West End, all contributes to the cultural significance of Kings Square, a sense of place, and the Fremantle identity.1

The proposed new civic building and library does a poor job of complimenting the heritage Town Hall. Firstly, the perforated metal façade, which presumably is for the protection of the tremendous glass walls behind it from direct solar exposure, has a “pretend” continuation of the architectural language of the Town Hall as illustrated in Image 1. The visual horizontals are picked up in the metal façade in a disorderly manner, the expression of floor height does not compliment the Town Hall, and it has a ground-to-ceiling height that disregards the architectural character of the West End. For instance, as illustrated in Image 1, the entry opening of the Town Hall corner is the base height for the start of the metal façade, and the start of the second storey is in line with the bottom of the pediment that frames the main entrance of The Hall, not the sill level string course just below the arched window cases. Furthermore, as demonstrated in the diagram in red highlight, the entire civic development overwhelms the Town Hall with its excessive monotone metal façade, and the upper two storeys are excessive in height (even setback from the lower storeys), being half way up the Town Hall’s urban marker – the tower. Even without the screen facade, the architectural language and scale of the Town Hall are addressed in a weird and confusing way in the Proposal. It’s inexcusable for the Proposal to only “not obstruct” the Town Hall’s tower, and disregard the rest of the building.

Furthermore, as detailed in External Requirements2 of CP 2020, the maximum height limit outlined in the West End Conservation Area Policy D.G.F14, which includes Kings Square, is “14m in Adelaide Street (not higher than the Woolworths Building), and William Street (not higher than the Federal Hotel); 15.5m in Queen Street (including the corner of High Street); and 14m to 18m in Newman Street/Court.”3 Image 1 demonstrates, the Proposal at a total building height of 20m, exceeds the permitted height of 14m, even exceeding the higher allowable height of 17.5m subjected to the criteria of setting-back the upper two storeys from the street

façade outlined in the Client Requirement4 of CP 2020. If Kings Square was not removed from the West End Conservation Area Policy (to LPP 3.21),5 then the selected Proposal may not have been as overwhelming as it is, and the cultural values of the Square not so obviously affected.

Similarly, the Proposal does not complement the other significant building of Kings Square, St John’s Church, instead the Proposal completely overpowers it in scale: its fourth storey is almost taller than the bell turret of the Church. Additionally, the precinct-scale redevelopment, the two respective five-storey commercial buildings east of Newman Court are already looming uncomfortably at the east edge of Kings Square, and as demonstrated in Image 2, the height of the buildings overshadow Newman Court during the winter mornings while the new civic building would likely overshadow it in the afternoon. Ultimately, the scale, architectural and material languages of the Proposal do not

4.5m

4.5m 20m

17m

20m 12.7m

17m

12.7m 3.3m

3.3m

20m

17m

20m 12.7m

17m

12.7m 3.3m

3.3m

Image 1: The visual horizontals of the Town Hall that assist in breaking up the height of walls, and to express scale, are not continued in the Proposal in a cohesive manner; as highlighted with arrows, it is expressed with a ground-to-ceiling height that disregards the architectural character of the West End. Extracted from City of Fremantle, Agenda Attachments: Special Strategy and Project Development Committee, Kings Square Project – Civic Building Schematic Design (Fremantle, WA: City of Fremantle, 2017).

complement the Town Hall, St John’s Church, or the rest of the urban precinct of Kings Square, which essentially decreases the landmark quality of these two historic buildings, and like a domino effect, diminish the townscape quality that contributes to the aesthetic value of Kings Square.

The Proposal also did not take the opportunity to retain nor enhance the defining townscape, in or around the borders of Kings Square, instead as discussed in Requirement 1, the Proposal responded to the place by filling up the entire site. It does not fit with the architectural character of High Street, its language of pediments, parapet skylines, truncated corners, arcades or verandahs, turning-the-corner towers, nor the shopfront display windows seen prior to the 1960s civic additions east of the Town Hall, and et al;6 with the Town Hall being an exemplar of this character. The Proposal – as if imitating the hull of a ship – juts out sharply at the intersections of Queen and High Street, and this treatment of the corner is not made any more comfortable with the FOMO buildings and their sharp right-angled corners. Essentially, the combination of all these “little” details – like little holes puncturing a dinghy – adds up to degenerate the elements and qualities that contribute to the cultural significance of Kings Square.

In addition, the Proposal and the Public Realm Report does not directly address Requirement 8 for the Retention of Significance outlined in CP 2020, 7 which is the protection of the special urban townscape qualities in the visual and planning axis of High Street that connects the Town Hall with the Round House. However, the public realm proposal does have several positive enhancements of Kings Square.8 The tree strategy includes the planting of new street framing trees, likely jacaranda, along Newman Court, Queen, Adelaide and William Streets, which will soften the borders, screen inharmonious border buildings, and reinforce the enclosure quality and definition of the Square;9 thus enhancing its urban townscape qualities. Additionally, it proposes to enhance the perimeter streets into high quality pedestrian, cyclist, and vehicle ‘shared spaces’, and instalment of traffic

Image 2: Overshadowing of Newman Court in the mornings by FOMO (left), and in the afternoons by the Proposal (right), which would likely effect on the overall qualities that contributes to the cultural significance of Kings Square. It highlights the importance of height restrictions of development in the urban precinct of Kings Square. Nearmap, accessed Nov 2, 2020, http://maps.au.nearmap.com/.

control infrastructure that will enable the limited vehicle access to Newman Court and the closing of Newman Court, Adelaide and William Streets for vehicles for functions.10 This could enhance, and increase the social value of Kings Square and retain the cultural heritage of the place through supporting a pedestrian safe zone.

Subsequently, the protection of the urban townscape qualities in the principal visual and planning axis of High Street, the secondary visual and planning axes of William, Adelaide, and Queen Streets and its connections should be addressed by Public Realm Report; this is the maintenance and enhancement of the wider urban precinct of Kings Square.

Endnotes

1. Ingrid van Bremen, and Samantha Dye, King Square, In the West End Conservation Area, Fremantle: Preliminary Draft Outline for a Conservation Plan (Perth, WA: the University of Western Australia, 2020). 2. Fremantle City Council, Conservation Policy for the Fremantle West End Conservation Area D.G.F14, (Fremantle, WA: City of Fremantle, 1989). 3. Ibid. 4. City of Fremantle, Kings Square Redevelopment: Council

Offices, Library and Square – Design Brief, (Fremantle, WA: City of Fremantle, 2013). 5. City of Fremantle, Draft West End Heritage Area Policy and Potential Scheme Amendment: Information Pack (August 2020), 2020, accessed Nov 3, 2020, https://mysay.fremantle. wa.gov.au/57831/widgets/295646/documents/176450. 6. Ingrid van Bremen, An Architectural Language For Townscape in Fremantle (Perth, WA: the University of Western Australia, 2020). 7. van Bremen, King Square, In the West End Conservation Area, Fremantle: Preliminary Draft Outline for a Conservation Plan. 8. Ingrid van Bremen, “Lecture 10 Urban precincts: Kings Square” (Lecture, University of Western Australia, Crawely, WA, Oct 7, 2020). 9. Ibid. 10. City of Fremantle, Kings Square Public Realm Concept Design Report (Fremantle, WA: City of Fremantle, 2018).

ARCT5589 FURNITURE DESIGN Unit coordinators: Guy Eddington & Peter Kitely TAYLA RYAN

Few people respect design and the importance of quality. Is it worth the investment? Is it practical in this society? I design with the intention to say YES, good design IS worth the investment. Quality is underrated and should be respected and utilised. Smart, aesthetic and well-produced objects provide longevity and quality. With principles of sustainability and designing for disassembly, opportunities are created that massproduced objects work against.

My designs minimise the range of materials. With simplicity in form, the beauty of the chosen material can shine. The Exude Lamp highlighted the qualities of brass: its colour, its strength, its ability to be manipulated. Coloured reflections exude off the circular shade. This plain looks as if it is floating above the simple brass form. This concept inspired the need for an accompanying piece to hold the same design motives and forms. What object best suits this lamp, a lamp that expresses simplicity, fragility, femininity, beauty and individuality? Such a lamp creates a subtle and atmospheric light and would therefore suit a space that requires softness: a bedroom.

A bedside table is the chosen object and will be designed to be a platform for the lamp to shine.

My design should embody timelessness with the intention of longevity. This product will require high quality materiality so to allow a long life. Designing for disassembly allowing for ultimately recycling materials if it is required.

Image: Tayla Ryan. Exude Collection. 2020. Photography by Matt Biocich.

This project was an opportunity to envision myself as a client and to analyse what my own future needs and dreams may be if I was lucky enough to design my own retreat away from the hustle and bustle of city life in a remote location to host small groups of friends, family, and pets.

The core idea was to create a focal point or give the cabin a ‘heart’ that it was spatially organised around. The central outdoor fireplace achieves this and becomes a space of relaxation during the colder months while also letting light flow through all the main living spaces.

Various types of spaces were provided such as covered outdoor space, uncovered outdoor space and indoor space. This enables the retreat to be useable through most times of the year while giving each space an opportunity to allow different uses.

The materials used aimed to bring about a warm atmosphere and light into the spaces by using materials such as stone cladding, timber, and plywood joinery.

Image: Serpentine Retreat, bedroom view.

ARCT5536 PHOTO REAL RENDERING Unit coordinators: Craig McCormack & Rene Van Meeuwen Teaching Assistants: Joshua James Duncan & Chaz Sheldon Flint ‘Idyllic Cabin Getaway’ ETHAN ANTHONY

Grounded is a peaceful cabin serving as a retreat from the intensity of the city while still maintaining proximity to friends and family situated in Perth. Located in Ferguson Valley, the construction method was chosen to reflect the surrounding natural landscape. Timber screens and earth walls ground the cabin in its surroundings.

The space provides privacy, space for guests and ease of access for aging occupants. A key requirement being provision for off the grid living which is heavily reliant on sustainable design. The solar and water collection, operable solar shade facade and a focus on passive design principles have enabled a comfortable program while taking advantage of natural light and views over the water.

Image: Exterior view with the timber screen closed.

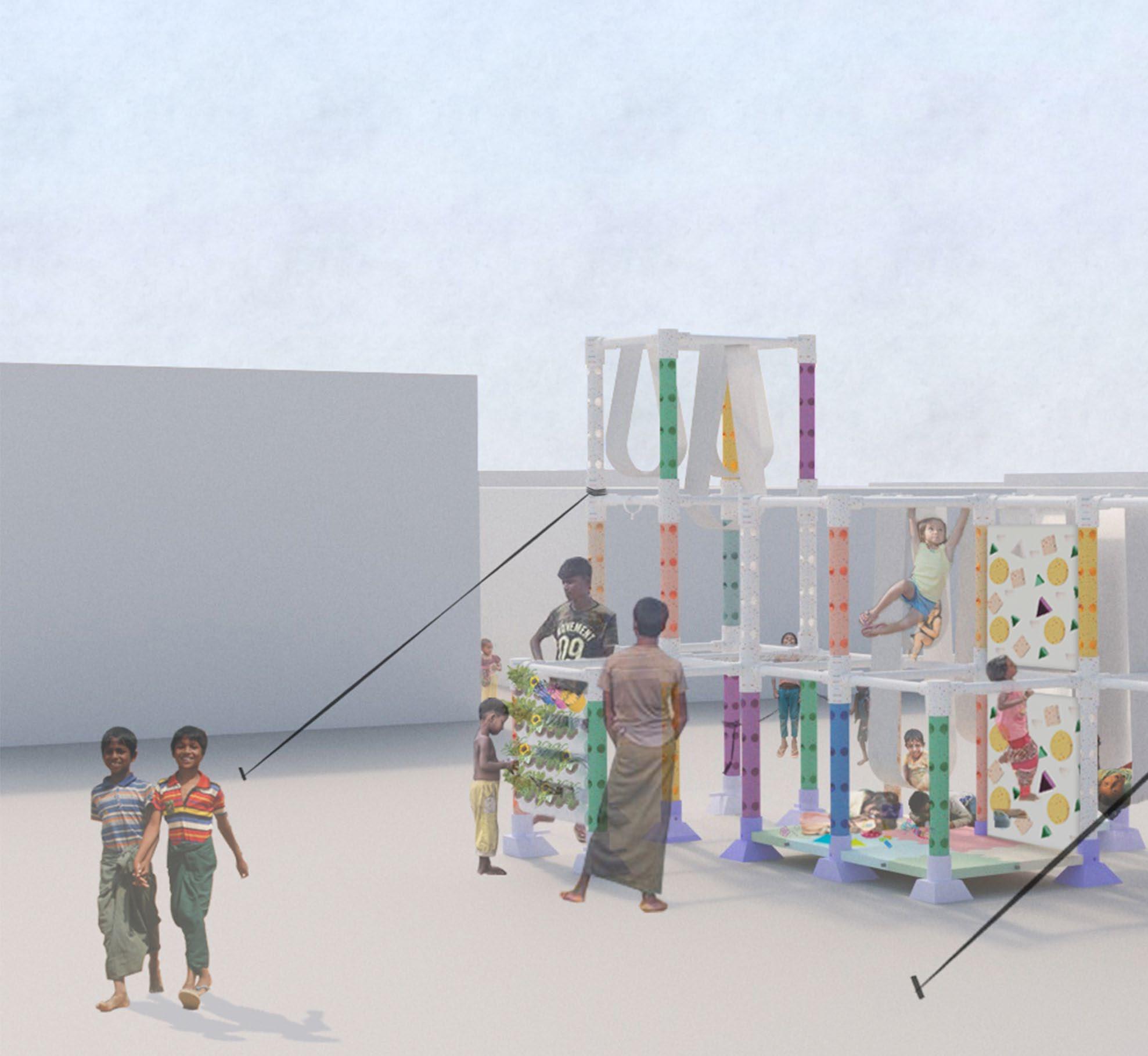

ARCT5585 BIO BASED MATERIALS Unit coordinator: Dr Rosangela Tenorio Teaching Assistants: Christian Wetjen, Jairo da Costa & Deepti Wetjen ‘Re-Imagining Play’ LYANA IBRAHIM, HAFIZAH MOHAMMAD, NURUL AZMAN & CALVIN THOO

Through the concept of self resilience, the process of re-imagining play has created a set of design principles that are explored through a series of modular typologies that are geared towards addressing the socio-cultural issues in the Kutupalong Refugee Camp. These design principles include the understanding of psychological aspects of the user group: they are children that have experienced displacement from their homes, trauma, and violence. The proposed modular typology can be explored as a base module that consists of a series of components created through the process of 3D printing. In analysing the social, environmental and economic aspects of the location, we concluded that plastic waste is the most sustainable option for the Refugee Camp as well as the Bangladeshi government. Additionally, this solution will help reduce the major waste and pollution issues present within the camp. The base module is centred around integrating the design response within a circular economy through which components can be assembled, disassembled, up-cycled or re-used, re-purposed and re-assembled. Play is a powerful medium where education and development can be cultured subconsciously. Therefore, four module variations are proposed with the integration of various components that serve as cognitive development. These variations are categorised as ‘active’, ‘rest’, ‘educational’, and a ‘mixed’ variation. The design of the Tool Kit allows it to be implemented in various other locations or contexts around the world, including material option of bio-based materials such as bamboo or timber.

Image: Base Module of ‘Tool Kit’ of Self Resilience.

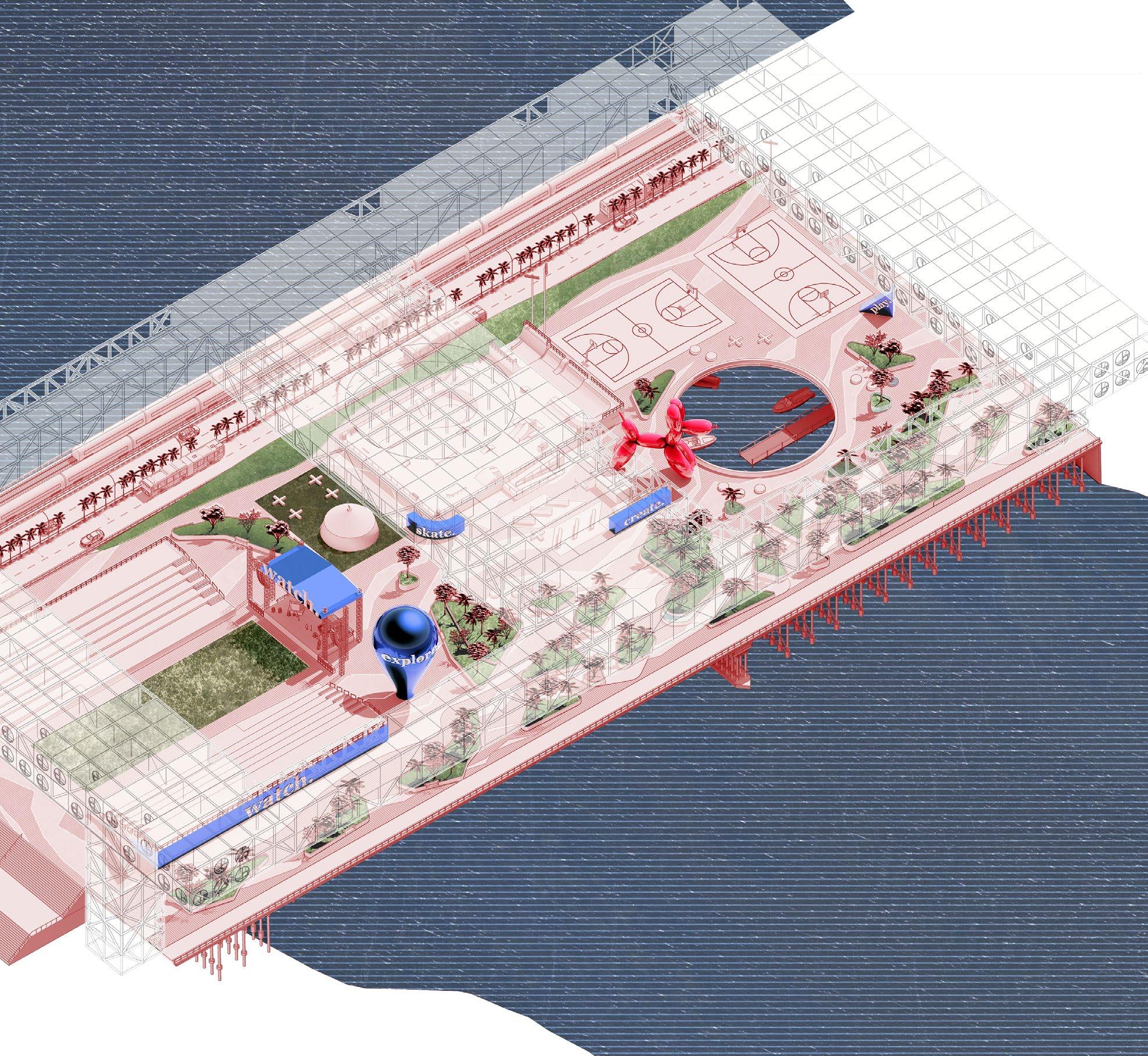

ARCT3001 ARCHITECTURE STUDIO 4 Unit and Studio coordinator: Lara Camilla Pinho Teaching Assistant: Stephen Thick ‘Second Wave - Designing spaces for infection control’ JUSTIN KATSUMATA YU

The COVID Recovery Centre explores a new condition for pandemic responsive architecture. The temporary nature of the design considers scaffolding in a building’s life cycle, integrating the structure as a skin that wraps around self-contained wards. Between the scaffolding lies both open-air circulation and vertical gardens which are grown from seedlings at the rooftop greenhouse, a breakout space for staff. Implementing this system for plants to grow reflects the healing and transitional state that architecture can assist in the wellbeing of its users. Vertical gardens are placed directly outside main viewing areas, continually growing, and changing over time for both patients and staff to experience.

The hospital program is split into three zones which are stackable and configurable in varying ways depending on the site. This allows for distinct separation in circulation and one floor or ward to be selfcontained if a breach were to occur. Designed as a lightweight modular steel structure, each zone is panelised into wall cassettes, which can be assembled off site and hoisted into place simplifying transportation and speed of construction. All materials are standard, recyclable, and globally available.

Image: Concept isometric.

ARCT3001 ARCHITECTURE STUDIO 4 Unit coordinator: Lara Camilla Pinho Studio coordinator: Jessica Mountain ‘The Freo Alternative’ CHARLOTTE MARTIN

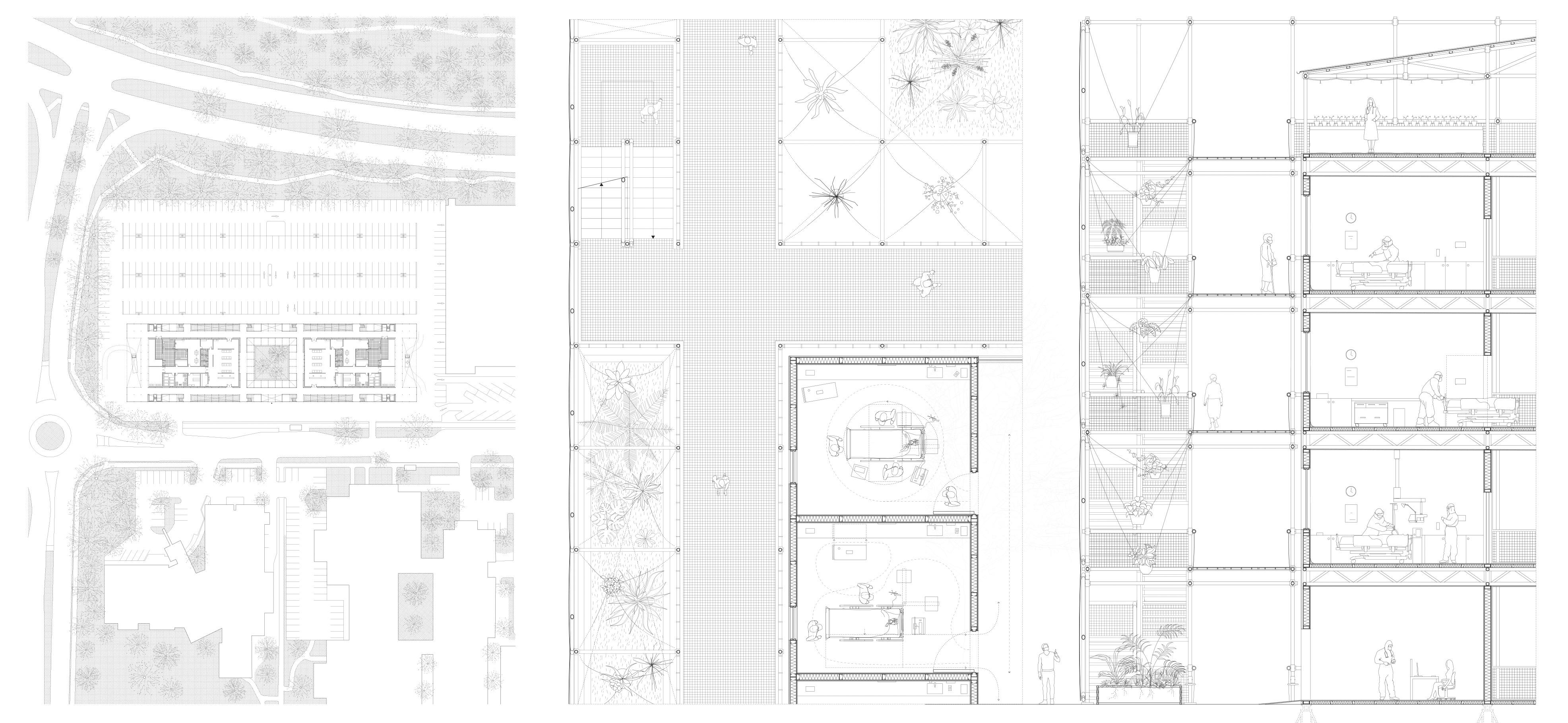

Using the city of Fremantle’s ‘Freo Alternative’ planning regulations and goals, the proposal for 60 Amherst Street in White Gum Valley focuses on providing small housing to fill the ‘missing middle’ gap in the current market. The Amherst Street proposal focuses on the concept of inter-generational living – it is designed to provide independent dwellings for both elderly residents and small families on the one block. Moving away from traditional suburban subdivisions, the bringing together of multiple generations in a union of young and old provides a way to aim to decrease loneliness and isolation in elderly people by immersing them in an environment where they are close to other people of the same age, and one that is also occupied by young people and children.

Image: Pivot Houses, section.

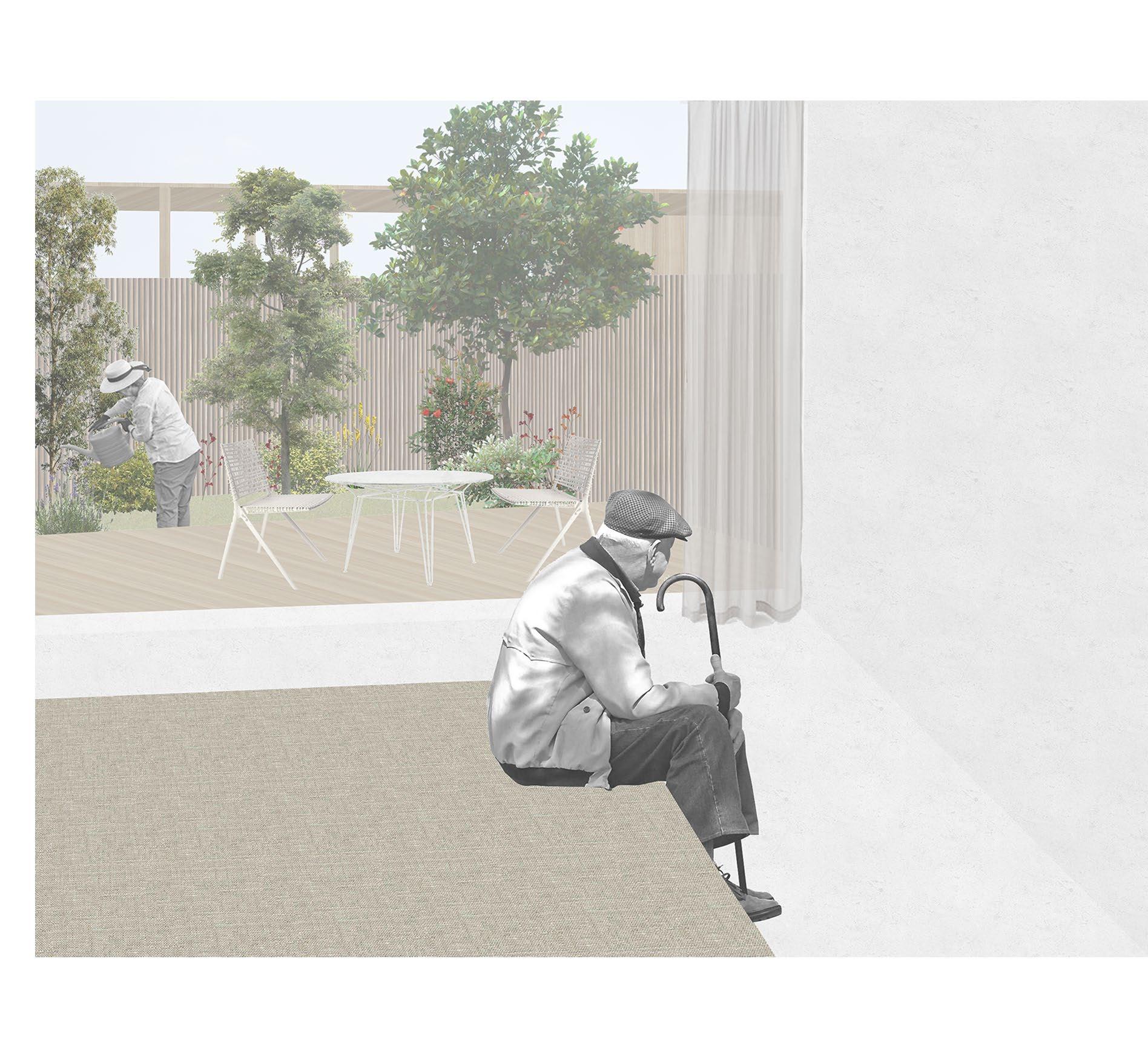

ARCT3001 ARCHITECTURE STUDIO 4 Unit coordinator: Lara Camilla Pinho Studio coordinators: Julia Kaptein & Lucy Mayne Dennis ‘Infrastructure Becomes Lived Environment - Bridge as framework for occupation’ BEAU ROBINSON

2032 will be a monumental period of change for Fremantle. The port from which its modern identity is formed will be replaced. This change is controversial and divides opinions, but could this be a necessary disruption that creates an immense opportunity to move forward?

This sacred site is one of the two main river crossing points for one of the oldest continuing nations of the Whadjuk Noongar. Bridges are transient in nature, and their utilitarian construction is focused on getting from one side to the other efficiently. Little attention is afforded to the experience one may get in the transition between the land void. A proposal on the site of the Fremantle Traffic Bridge has both the privilege and duty of being more than a traditional crossing: it should engage and create a dialogue with the community, proudly representing an area with such a wealth of stories to tell.

Exposition Universelle in 1889 gave birth to the iconic Eiffel tower, originally intended to be a temporary structure, and the proposal of a new infrastructure in Fremantle is inspired by the celebration of world expos and their associated iconic structures. The bones of the infrastructure and the proposed train station would remain fixed elements, remaining long after the expo is dismantled, continuing to provide a greater community benefit. An ode to the former gantry structures core to the modern day identity of the iconic port.

The expo celebrates the dawn of a new era for Fremantle, with the structure challenging the perception of the bridge as solely infrastructure. The proposed programme will focus on cultural and ritual exchange. No longer will the journey across the traffic bridge be a regimented and unremarkable routine, but one that attracts people to want to stay immersed in what it has to offer to the community.

To borrow a term from the vernacular, this new gateway will be quite uniquely ‘Freo’.

Image: Isometric projection.

ARCT3030 CONSTRUCTION Unit coordinator: Andrea Quagliola Teaching Associate: Mark Jecks MICHAELA SAVAGE

Bound by natural cliffs and man-made bastions, the famous fortress of Valletta claims the title of Europe’s first planned city. With such a long history to consider for the new Parliament House, Renzo Piano’s Building Workshop has crafted a design that inserts itself seamlessly into its local Mediterranean context. They managed to balance the need for contemporary public amenities with the desire to preserve the site’s significant heritage.

Fashioned from local coral limestone, the ‘eroded’ façade mirrors the weathering patterns of the city’s fortification walls. While its sculptural-relief texture seems random and natural, the façade cleverly consists of a system of repeated stone modules. With the danger of earthquakes making a load-bearing stone structure impossible, these elements are mounted on a steel frame structure.

This restrained tectonic intervention beautifully contributes to the larger aim to reinvigorating the public realm at the heart of Valletta through the broader City Gate redevelopment.

Image: Renzo Piano’s Valletta Parliament 2D Analysis.

ARCT3040 ADVANCED DESIGN THINKING Unit coordinator: Kirill de Lancastre Jedenov Studio coordinators: Kirill de Lancastre Jedenov & Amber Martin ‘Ideas for a Post Pandemic Perth’ KATHY CHAPMAN

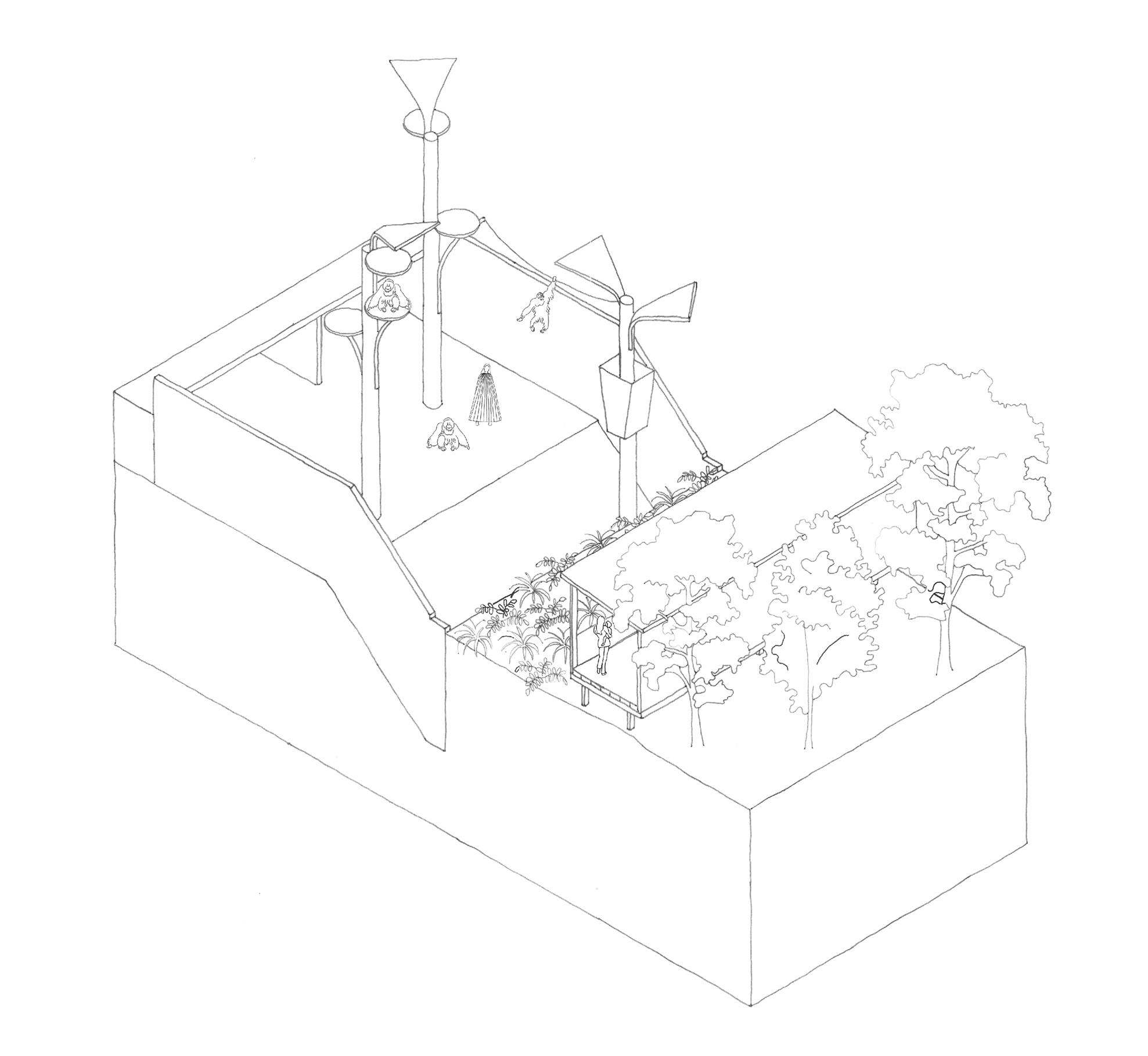

Orangutans are social creatures and have some cognitive awareness, akin to a six-year-old human, therefore when COVID-19 struck they were conscious of the lack of visitors. Combined with the enforced PPE and distance the zookeepers had to maintain while in the orangutan enclosure to prevent crossspecies contamination, the orangutans’ mental health began to decline.

Monkeying Around aims to combat the orangutans’ feelings of isolation and loneliness by enabling zookeepers to interact with the orangutans while also creating a piece of public performance art. Monkeying Around consists of a long dress-like form that covers the entire human body from the neck down. The alternating coloured stripes provide visual enrichment for the orangutans through contrasting patterns and bright colours, which are similar to fruit orangutans enjoy eating. The zookeepers would not be able to use their arms which eliminates the risk of cross-species contamination and allows the keepers to interact with the animals through conversation.

The public performance aspect of Monkeying Around utilises the abstract shape and movement of the garment to engage with the zoo’s visitors. The zookeeper’s form will change through environmental conditions such as wind, or by physical movement such as walking, running, jumping or spinning. When the zookeeper is spinning, the brightly coloured stripes (in this example the pink and blue stripes) blur together creating a different colour, thus adding to the public spectacle. In addition to this illusion being carried out, the dress also fans out to have a 1500mm radius, enforcing social distancing.

Monkeying Around is intentionally easy to make and therefore can have multiple variations, simply by changing the colours of the stripes or by changing the pattern of the dress. This ensures that the orangutans do not become uninterested in the outfit, guaranteeing visual enrichment throughout the foreseeable future.

Image: Monkeying Around Prototype - Abstract Shapes Caused by Spinning.

A

B

B

A ARCT1001 ARCHITECTURE STUDIO 1 Unit and Studio coordinator: Dr Philip Goldswain Teaching Assistant: Samantha Dye ‘Fire! Civic Architecture in the Age of the Pyrocene’ TAN KAI YANG

Margaret River Fire Station required the design of a project that was a recognisable facility that expressed its function as a fire and emergency services building. The station also had to have a presence within the landscape and encourage community engagement. The studio investigated a number different generic typological forms, examples like ‘E’, ‘Additive’ and ‘Cluster’ to develop the specific architectural forms for the fire station. Each typological form was tested with a number of factors: how the building reacted to site topography, opportunities for passive daylighting and ventilation as well as community accessibility. After selection of the final typology, the architectural form of the building was then further developed based on the functional necessities of the fire station, with highly specific ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ zoning for different spaces as well as a number of quantitative and qualitative requirements.

Image: Margaret River Fire Station, building plan.