38 minute read

History of Art

HART3276 PRINTS FROM DURER TO TOULOUSE-LAUTREC Unit coordinator: Dr Susanne Meurer BYRON ELLIS

The woodcut is the earliest form of print media present in Europe. The productive materials they require are abundant and inexpensive, while the printing process for each individual impression is as simple or as complicated as the artist wills it to be. This has resulted in the adoption of woodcuts in ‘high art’ practices as well as mass media. Félix Vallotton and Urs Graf are masters of the medium, albeit almost four centuries apart. Both professional artists from Switzerland, they lived and worked in different periods and their work reflects this. From the sophisticated designs of German Renaissance to the expressive turn towards abstraction pursued in late nineteenth century France, their use of the woodcut is both appropriate and interesting. This essay will compare Vallotton’s L’Exécution (1894) and Graf’s Standard Bearer of Schaffhausen (1521) on thematic, compositional and formal levels.

Woodcuts are examples of the relief printing process whereby sections of the matrix are cut away to leave the desired printed design in relief, to be inked and then impressed. Usually the impressed design has large portions of the block cut away leaving a web of thin, raised lines which give form and tone to the image. The two selected prints stand in contrast to most woodcuts as the artists leave a significant portion of the matrix uncut, resulting in an image dominated with black masses of ink surrounding small, incised sections highlighting the details of the figures. L’Exécution and the Standard Bearer are united in this stylistic choice, but differ as the lines which construct Graf’s image are incised into the matrix to produce a rare example of the ‘negative’ or ‘white-line’ woodcut as opposed to the modernist Vallotton’s more traditional approach.

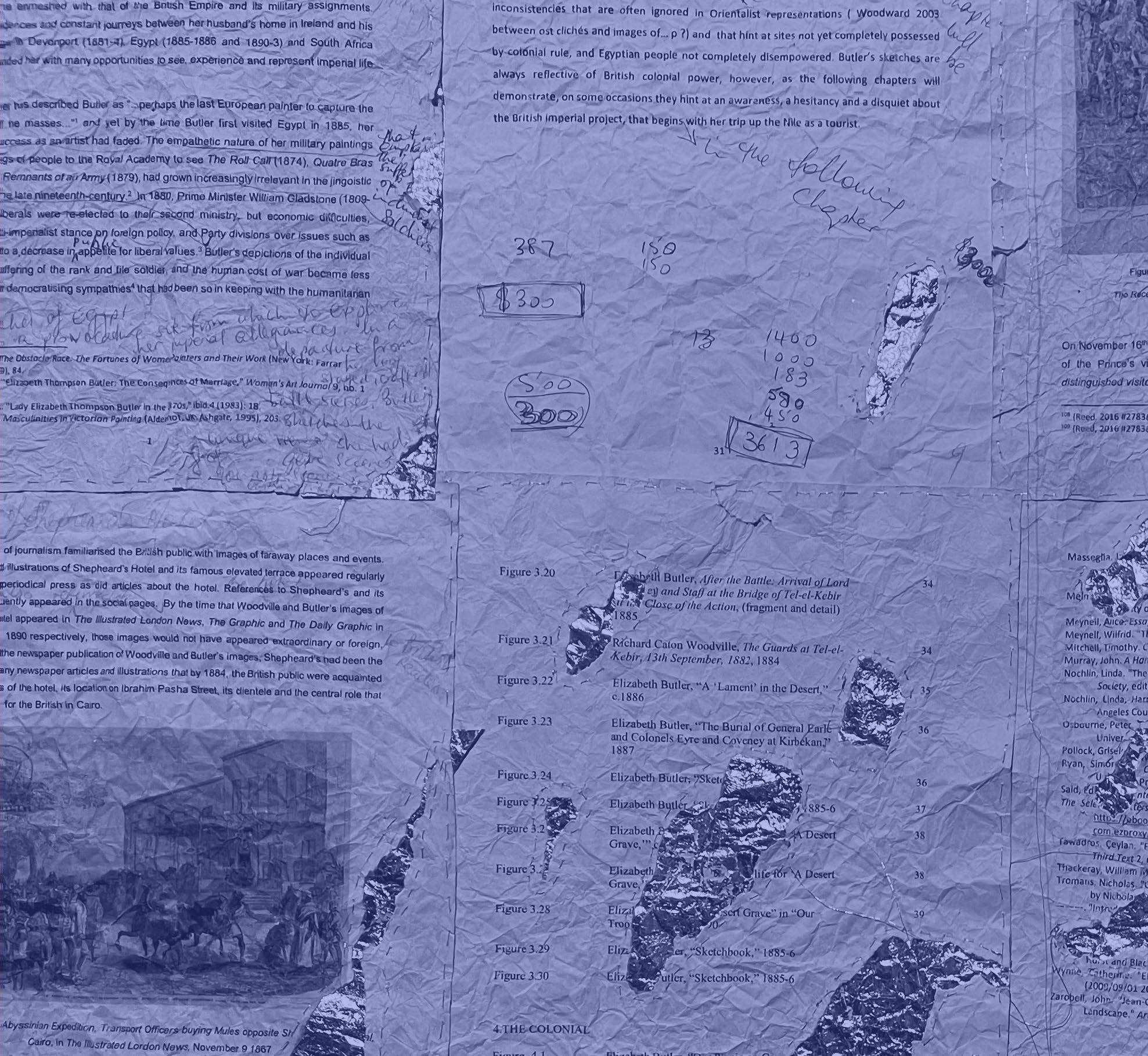

Vallotton’s predominately uncut matrix creates a dark, tense atmosphere for the defined figures to exist in. The background of the scene is cordoned off by a line of uniformed soldiers, each holding a thin sabre over their left shoulder and sporting a moustache and bicorne hat with a republican cockade attached. Repeated motifs, created by simple strokes of the cutting tool, establish aesthetic uniformity across all eight men. In front of the soldiers on the right of the scene are three bourgeois gentlemen, all anonymous, suited, and indifferent towards the unfolding scene. This reflects the artist’s desire to unmask bourgeois gentility for its vicious falseness1 by implicating them in acts of state violence though their proximity. These figures form the end point of a strong diagonal vector that leads the viewer’s eye from the arm of the executioner to the prisoner and eventually to these three men. The only figure to be defined by large amounts of white space in the print is the prisoner who is being thrust towards his fate by two top-hatted men. A movement heightened by the gradual right to left variation of dark to light formed by an increasing density of incised lines. The prisoner’s face and torso, closest to the unseen guillotine, are among the lightest areas of the print which lack definition, effectively obscuring his identity. In contrast, the hands of the men restraining the prisoner as well as those of the beckoning executioner are defined through dense and precise linework. The particular execution depicted was likely Sante Geronimo Caserio, the anarchist who assassinated President Carnot and was tried and executed in the same year the print was published, 1894.2 This print comes from a larger theme in the works of Vallotton (whose

Image: Félix Vallotton. L’Éxecution. Museum of Modern Art, NY. 1894.

initials F.V. are in the bottom right corner) depicting scenes associated with state violence before, during and after the fact – a theme that finds full expression in his later print works depicting the expressions of modern industrialised warfare which ravaged France in the Great War.

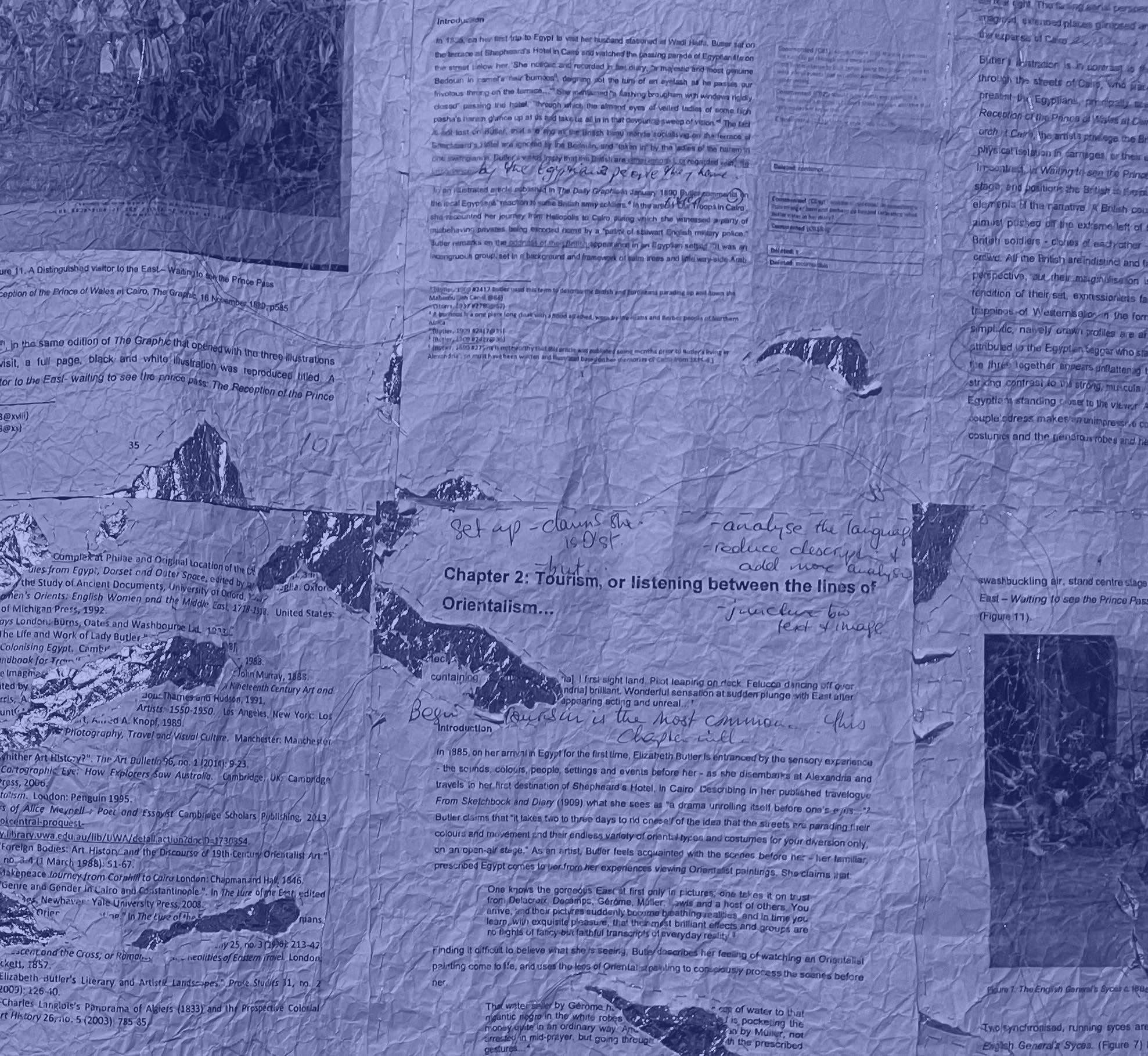

The period of time Urs Graf dealt with was likewise dominated by violence and warfare albeit on a much more local level. His design depicts a Swiss mercenary Keislaufer in a typical composition, similar to his fifteen other ‘whiteline’ woodblock prints in this series. The soldier’s identity, obscured by his head turned in profile, gives way to him acting as a representation for his class. The status of which is defined by his intricately patterned garments and muscular physique. In the left hand of the soldier is his town standard depicting the traditional heraldry of the city of Schaffhausen. In the canton of the standard is a haloed Mary, who kneels reverentially and maternally over a Christ-child stretching his arms out towards his mother, all of which is rendered minimally in an abstract style caused by the small scale of the image in the context of the whole. This restricts the amount of detail that can be rendered by the hand carving of the block. Dwarfing the Madonna and Child is a large, spiral-horned ram which gazes in the same direction as the soldier who stands directly beneath, aligning their strength and wilfulness. This visual metaphor is reflected in the coincident curves of the ram’s forelegs and the soldier’s left shoulder, and further heightened by the similarities in the representation of the ram’s horns and tail with the feathers in the soldier’s cap. The most immediately obvious impact of the ‘white-line’ design is the field of the standard which is indistinguishable by colour from the inked background of the rest of the print. The exception to this is the series of almost-parallel, curved incisions in the right corner of the standard framing

Image: Urs Graf. Standard Bearer of Schaffhausen. British Museum. 1521.

the image and suggesting movement. The lines which constitute the ram convincingly suggest the animal’s form, effected through the broken circular lines of its coat as well as the limited shading of its legs and head. The most visually striking area of the print is the mercenary’s richly decorated outfit. This area, densely populated with the incised, white lines, obscures the novelty of Graf’s printing technique. As the viewer moves beyond a first impression and comes to notice the white outline of the figure, the complexity of the composition is revealed and the relationship between black and white is complicated as both, in close proximity, act line and tone. The work is divided horizontally on its lower third by zweihänder sword which, along with the pole and standard, frames a two-thirds portrait of the soldier. Beneath this portrait on either side of his pantalooned legs inscribed is the name SCHAFHVSEN and date 1521 which places the work in the context of Graf’s series. The block was likely cut by Hans Lützelburger, the skilled artisan who also worked with Hans Holbein in Basel.3 The ‘white-line’ style of the print is rare for the period and is an interesting example of experimentation in a very popular medium.

While the most obvious shared feature of these works is the medium, there are thematic and stylistic similarities which frame the differences meaningfully. The dominance of the inked, uncut areas of the matrix in each impression is used effectively in both to assert the artists’ skill in the production of detailed designs which stand boldly in contrast against a darker mood. In both prints the artists draw an association of status and justified violence as the opulent dress of the Keislaufer reflect his success as a mercenary, the suits of the bourgeois reflect the respect for their civilian role meting out corporal punishment. The key difference between the artists is the mood of each print. While Graf depicts the standard bearer proudly and respectfully with intricate attention to detail, Vallotton shows his disdain for the executioners in their rough anonymity and the sympathetic ambiguity represented in the face of the prisoner. This difference has its roots in each artists’ context: Graf proudly recalled his own service in a mercenary company,4 while Vallotton was a critic of the bourgeois ideals of the French Third Republic.5 Furthermore, the nature of the representation is informed by each artists’ position within their stylistic movement. The realistic, proportional style of Graf is informed by his place in the artistic milieu of the German Renaissance inasmuch as Vallotton’s expressive turn to abstraction is informed by the modernist developments in France. In viewing these two works the viewer is meant to feel different emotions: sympathy in the patriotic sense or sympathy in the pathetic sense, respect and awe or fear and trembling. Their effectiveness and importance are reflected in their collection by some of the world’s most eminent institutions and the tacit acknowledgement that they are both worthy as ‘high art’.

Endnotes

1. Merel van Tilburg, “The Figure in/on the Carpet: Félix Vallotton and Decorative Narrativity,” Konsthistorisk tidskrift/

Journal of Art History 83 no. 3 (2014), 218. 2. Bridget Alsdorf, “Félix Vallotton’s Murderous Life,” The Art

Bulletin 97, no. 2 (2015), 216. 3. Giula Bartrum, “Switzerland,” in German Renaissance Art 1490-1550, British Museum (London: British Museum Press, 1995), 218. 4. Bartrum, “Switzerland,” 219. 5. Bridget Alsdorf, “Félix Vallotton’s Murderous Life,” 215.

HART3330 ART THEORY Unit coordinator: Arvi Wattel Teaching Assistant: Kelly Fliedner ISABEL DI LOLLO

Branding him “the father of art history,”1 Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists remains a distinguished art biography and foundational text for modern art history. First published in Florence in 1550, the text was revised and developed in 1568.2 Presenting the lives of great artists in three parts of relative chronology,3 Lives follows a progression from the ‘coarse’ age of Cimabue to the ‘complete perfection’ of modern artists – Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo.4 Closer resembling biography than contemporary historical texts, Vasari’s work aimed to identify causes distinguishing the best (artists and styles) from the better and those from the good, as well as acting as a commemorative piece. Lives had a profound impact, remaining an essential primary source in studies of Renaissance art and generating significant praise.5 However, there exists a substantial body of criticism questioning Vasari’s legitimacy and obsession with narrative. John Shearman epitomised these critiques with the comment, “I assume that Vasari reshaped history to fortify his own self-esteem and to compensate for a deep insecurity, if only as an artist.”6 Issues with Vasari’s Lives are centred around his mythologising of artists, use of rhetorical hyperbole and doubt about Vasari’s ability to act as an objective critic. In examining these controversial aspects through the analysis of Lives chapters ‘Preface to Part Three’ and ‘The Life of Leonardo da Vinci, Florentine Painter and Sculptor,’ it is clear that these aspects were,

largely, meticulously planned by Vasari himself and are still pertinent to the study of art history.7

As Vasari gives great importance to form – evidencing artistic ‘masters’ through rule, order, proportion, design, and style – it is clear that Lives remains pertinent to art history. However, Vasari relies predominantly on mythologising others in the writing of these biographies, believing external factors as consequential elements in artists’ success. Patricia Rubin addresses this idea that “artists become symbols and metaphors,” as Vasari twists events to create heroic narratives.8 Exampling the “obvious exaggeration of Leonardo’s gifts” as an indicator of Vasari’s fabrications, she regards his strategy as not untruthful but in effort to distinguish Leonardo and the importance of his art,9 his enduring fame a testament to Vasari’s technique. Writing that “the greatest gifts often rain down upon human bodies through celestial influences… each of his actions is so divine that he…clearly makes himself known as a genius endowed by God…”,10 Vasari establishes Leonardo as a character of supernatural perfection. This garnered sufficient criticism as the idea of creating a ‘myth’ appears to openly contradict Vasari’s position as a “self-designated… truthful historian.”11

Vasari furthers this view through regarding physical attributes as an essential part of praise. Describing Leonardo’s “great physical beauty,” and “splendidly handsome appearance,”12 raises issues due to the subjective nature of this judgement, although, the popular Renaissance proverb, “every painter paints himself,”13 appears to provide some explanation for this biographical inclusion. To associate Leonardo with perfection, he would also have to appear perfect. Yet, this creates a unique contradiction for Leonardo, as to Vasari he exists as both a symbol of perfection and bearer of substantial criticism, pertaining to unfinished work. This appeared not to trouble Vasari, possibly due to the chapter’s alleged allegorical meaning.14

Although including Leonardo in the realm of perfection, Vasari remains highly critical of him. This criticism centres around Leonardo’s inability to finish the things he started, declaring “he would have made great progress in his early studies of literature if he had not been so unpredictable and unstable. For he set about learning many things and, once begun, he would then abandon them.”15 These critiques are explained by Vasari, stating that Leonardo was hindered by his eagerness and search for excellence, feeling as though his “hand could not reach artistic perfection.”16 Rubin suggests such remarks were necessary to demonstrate the objectivity required of a historian.17 Though the text never really presents itself as wholly detached from its information – as is common in contemporary academia – as Vasari continuously references his own moral commentary and emotion. Rubin speaks kindly over Vasari’s situation, as other historians and writers show little time for his contradictions and self-imposed authority, especially pertaining to his Florentine biases and carelessness over details which fail to fit the intended narrative.18

Within his criticisms of Leonardo, Vasari establishes himself as a moralist. Although condemning his time wasting, Vasari applauds his generosity.19 Informed by the Ciceronian view of “the virtuous life,”20 Vasari presents himself as not only a judge of artistic style but lifestyle. This has proved controversial, with John Ruskin praising him for “his remarks and morals,”21 whilst others, particularly rivals Federico Zuccaro and Bartolommeo Bandinelli, dismiss his authority as the comments of “a pedantic dimwit (saccente).”22 Ultimately, Vasari’s critical legitimacy is forged through his strong authorial voice at the helm of Lives, a technique adapted and featured in most

Image: Giorgio Vasari. Frontispiece to Giorgio Vasari’s Life of Leonardo da Vinci, from a 1791 edition of Vasari’s Lives. Woodcut on laid paper. Royal Academy of Arts. canon art literature. However, this position is still retrospectively disputed, believed undermined by Vasari’s lack of, albeit modern, detachment.

To Vasari, “it was not worth his time, merely to state facts.”23 This is evidenced in Lives through fabrication of events and rhetorical hyperbole. Issues with the mythicising of artists, academic legitimacy, and the ‘forgetting’ of important factual information all engage with this notion of falsity. Vasari initially appears unreliable, Zuccaro claiming him “false and slanderous.”24 However, considering Renaissance writing styles, Vasari’s fables become tools in the preservation of great artists. Vasari aims to write the lives of the artists which pertain to art, in doing so he selects events which example virtuous morals and great talent.25 Paul Barolsky evokes conceptual discussion around ‘historical imagination,’ challenging art historians’ discomfort generated by fiction in history and highlighting the critical nature of Vasari’s fables in his work.26 Drawing upon Vasari’s tales, Barolsky illustrates connections between fiction and the history of art itself, identifying true reflections in the allegory of art.27 In this way, art history and the artist’s biography become almost inseparable, complimenting Vasari’s view of art as an fixed, abstract principle.

Vasari’s discussion of Leonardo and the third style in Lives is a quintessential example of the polarising nature of his work as a whole. Ruskin wrote, “it is modern fashion to despise Vasari;”28 however, its stoic position within art history discourse, as the first extensive biography, is undeniable. Vasari’s reliance on the narrative, whether to promote fictional fables, mythicise artists, or provide moral criticism, has proven controversial since its first publication. Assessing his legitimacy is a complex process; particularly due to conflicts perceptible in the text itself. Yet, the ongoing relevance of Vasari and enduring aspects of his writing, suggest the continuing importance of the Lives in historical art discourse.

Endnotes

1. Chris Murray, Key Writers on Art: from Antiquity to the

Nineteenth Century (Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Group, 2002), 66. 2. Paul Barolsky, “Vasari and the Historical Imagination,” Word &

Image 15, no. 3 (1999): 286; Murray, Key Writers on Art, 66. 3. Charles Hope has alleged that this partitioning may have instead been advised by members of Accademia Fiorentina rather than of his own volition. Matteo Burioni, “Vasari’s Rinascita: History, Anthropology or Art Criticism?” in

Renaissance? Perceptions of Continuity and Discontinuity in

Europe, c.1300–c.1550, ed. Alexander Lee, Pit Péporté and

Harry Schnitker (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2010), 115. 4. Amongst others. Patricia Rubin, “What Men Saw: Vasari’s Life of Leonardo da Vinci and the Image of the Renaissance Artist,” Art History 13, no. 1 (1990): 35. 5. Murray, Key Writers on Art, 69. 6. Philip Sohm, “Giving Vasari the Giorgio Treatment,” Itatti

Studies in the Italian Renaissance 18, no. 1 (2015): 66-67. 7. Exampled by the application of tripartite notions of history; has been attributed to Vasari by August Buck, amongst others. Alina Payne, “Vasari, Architecture, and the Origins of Historicizing Art,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 40 (2001): 51. 8. Rubin, “What Men Saw,” 34. 9. Ibid., 36. 10. Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists (New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 1998), 284. 11. Sohm, “Giving Vasari the Giorgio Treatment,” 70. 12. Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, 284+298. 13. Martin Kemp, “‘Equal excellences’: Lomazzo and the explanation of individual style in the visual arts,” Renaissance

Studies 1, no.1 (1987): 10. 14. As discussed later in essay. Rubin, “What Men Saw,” 43. 15. Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, 284. 16. Ibid., 286-287+293. 17. Rubin, “What Men Saw,” 37. 18. Ibid., 39. 19. Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, 298. 20. Burioni, “Vasari’s Rinascita: History, Anthropology or Art Criticism?” 121. 21. Jenny Graham, “‘An ass with precious things in his panniers’: John Ruskin’s reception of The Lives of the Most Excellent

Painters, Sculptors and Architects by Giorgio Vasari,” Journal of Art Historiography, no. 22 (2020): 31. 22. Sohm, “Giving Vasari the Giorgio Treatment,” 110. 23. Rubin, “What Men Saw,” 36. 24. Sohm, “Giving Vasari the Giorgio Treatment,” 110. 25. Burioni, “Vasari’s Rinascita: History, Anthropology or Art Criticism?” 118; Rubin, “What Men Saw,” 34. 26. Barolsky, “Vasari and the Historical Imagination,” 287+290. 27. Vasari also imputes moral values into said fable. Leonardo’s indifference to market value reveals his dedication to art, however also undermines him. Rubin, “What Men Saw,” 42; Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, 289; Barolsky, “Vasari and the Historical Imagination,” 287+290. 28. Graham, “‘An ass with precious things in his panniers,’ 29.

HART2274 INTRODUCTION TO MUSEUM AND CURATORIAL STUDIES Unit coordinator: Dr Susanne Meurer HEYANG GUO

Reaching its peak as idyllic pastoral paintings during the Romanticism, the landscape has now entered more versatile realms of manifestation that mirror the increasingly protean nature of human existence. Traditionally, landscape paintings were relegated a subordinate position in the hierarchy of genres because no moral comment on human nature could be communicated via the depiction of an environment alone. The Petzel Gallery’s online exhibition, 21st Century Landscapes, subverts this archaic contention by raising ethical queries regarding the influence of the Anthropocene on human relationships with the environment through a compilation of insightful contemporary landscapes. 21st Century Landscapes addresses how the pervasiveness of technology and consumerism across all facets of contemporary life engender a pernicious effect on our connection to, and perception of, the environment. 21st Century Landscapes is an exhibition delivered in an online format as a scrollable website. The online exhibition commences with the title framed within the hole of an enlarged crop of the found painting and collage, Tears XI (2018), by John Stezaker. The name of the host gallery, Petzel, is located above the exhibition title. When you scroll down the page, you are greeted with a concise yet informative summary of the history of landscape painting and the purpose of the exhibition. The name of each featured artist is embedded within this introduction and listed in alphabetical order by surname – an overt acknowledgement of the contribution of each artist. The exhibition is interspersed with pertinent quotes by individuals with esteemed reputations in the field of art. These quotes provoke contemplation on various aspects of the exhibition by either stimulating thought in regard to the exhibition as a whole, or the artworks that the quote directly precedes or is adjacent to. For example, immediately after the introductory description, a quote by Hito Steyerl from her 2011 article, In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective, is used to underscore the premise of the exhibition: “With the twentieth century, the further dismantling of linear perspective in a variety of areas began to take hold… Time and space are reimagined through quantum physics and the theory of relativity, while perception is reorganized by warfare, advertisement, and the conveyor belt.”121st Century Landscapes has translated the white cube model to an online mode. By employing black and grey text on a white background with pale grey borders to frame individual artworks, distractions are removed to create a sense of minimalism and neutrality. All textual elements of the exhibition – titles, headings, details regarding artwork, etc. – are set in a trim sans serif font that reinforces the modern and topical focus of the featured artworks.

The construction of this online exhibition humbly simulates the space of a physical gallery exhibition. In a physical gallery, it is common for smaller subsets of artworks to be situated in the same viewing space or along the same wall to enhance the communication of a shared sub-theme within the overarching theme of the exhibition. 21st Century Landscapes mimics this arrangement by dividing the exhibition into three distinct sub-themes – Pastoral Landscapes, Psychological Landscapes, and Political Landscapes. The exhibition also bestows viewing agency upon the audience by

Image: John Stezaker. Tears XI. Found painting and collage, 45.3 x 50.5 cm. 2018.

providing the choice to observe works singly or as a group. This provision of option further emulates the experience of visiting a physical gallery space: one can view each painting individually or ‘step back’ (i.e. select gallery view) to observe the collection of paintings as a whole.

The first sub-theme, Pastoral Landscapes, is centred around the physical relationship between humans and the environment. The gallery view for the Pastoral Landscapes sub-theme features four of John Stezaker’s found object artworks and one abstract oil painting by Nicola Tyson. The Stezaker pieces are part of his Tears series in which each work portrays a different pastoral landscape with holes (or tears) located where the main subject matter of each painting should be. Tyson’s oil painting, Figure with Tree (2011), depicts a human figure performing a scissoring motion with their arms; this figure is located beside a tree that has a hole within its foliage. When viewed together, these works effectively supplant the purpose of traditional landscape paintings – to depict the environment in a highly idealised and contrived fashion. The damage that has been depicted in, and physically inflicted upon, the artworks of Pastoral Landscapes disrupts the viewer’s pre-conceived perceptions of the landscape genre and primes them for exposure to a more relevant and morally challenging portrayal of the environment.

As you scroll past the Pastoral Landscapes section, the entirety of your screen is filled by an image depicting chewed hamburgers, scattered French fries, ketchup packets, and pale chartreuse wrappers on a bitumen-coloured background. This is Budget Meal Pattern (2019) by Thomas Eggerer. This work signposts the Psychological Landscapes sub-theme which emphasises ideological and behavioural changes caused by the Anthropocene. 21st Century Landscapes addresses the internalisation of consumerist ideologies that are systematically espoused by the media. Our coveting of material possessions and our demands for instant gratification colour how we interact and perceive our surroundings. Budget Meal Pattern effectively reflects our dogmatic attitude toward the acquisition of products by positioning the subject matter to resemble a bird’s eye view of roads and blocks in a city. Consumerism is the updated street directory that guides and directs every aspect of our lives – it becomes the twenty-first century landscape rather than a mere feature of it.

The Psychological Landscapes section of the exhibition is intensely disturbing because it reveals truths about our dependency on technology that we do not consciously cognise. It prompts one to question the actuality of our experiences with the environment and whether or not those experiences hold any value. Corinne Wasmuht’s oil painting on wood, Nizza (2005/2018), depicts Nice as a semi-pixelated, distorted, and glitching image. This artwork perfectly encapsulates the exhibition’s intent to demonstrate how the perception of our surroundings is contingent on our addiction to digital technology. Landscapes have been transmuted from idyllic pastoral scenes to distorted pixelations that reflect the growing discord between humans and the natural environment.

The final section of the exhibition, Political Landscapes, is introduced by an emphatic quote from the abstract landscape painter, Julie Mehretu: “There is no such thing as just landscape. The actual landscape is politicized through the events that take place on it.”2 This quote steers the focus of the sub-theme toward the contemplation of power and its inextricable relationship to space and people. The artwork, True Finn (2014), is a 50-minute film by Yael Bartana that examines how individuals who reside in Finland interpret their identity and how they define belonging to a space. The topics of discussion within the film

include nationality, ethnicity, spirituality, and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. True Finn is a prudent inclusion to this exhibition because its medium allows for the generation of a human connection that cannot be achieved by a still image. The placement of this work toward the end of the exhibition allows the audiences to leave the exhibition feeling as if they have been included in a topical and progressive conversation.

Despite the earnest attempts to mimic a real gallery space, 21st Century Landscapes simply cannot substitute the experience of standing before a tangible object and allowing yourself to be confronted by the presence of the artwork itself. The Petzel Gallery has taken much care in translating a physical space onto a digital platform however there are certain elements of the construction of the online exhibition space that feel arbitrary and confusing. The exhibition chooses certain artworks to signpost each subtheme; generally, these ‘signpost artworks’ are enlarged to fill up the entire screen and precede the sub-theme from which it belongs. However, this formula is not applied consistently throughout the exhibition and causes unnecessary breaks and illogical demarcations within the exhibition. Compounding to the confusion is the inclusion of an aerial photograph with an overlay of the words “galesburg, illinois+”. This work is placed at the very end of the exhibition without a description to accompany it. Such choices seem superfluous, disruptive, and completely incongruous with the serious tone of the exhibition. 21st Century Landscapes has demonstrated innovation through the provision of a refreshingly unique assortment of artworks that are (mostly) mutually cohesive and congruent with the theme of the reassessment of contemporary perceptions of the landscape. Each artwork proffers a different lens through which audiences can deliberate on how we perceive, treat, and depict the surroundings in which we reside. The encompassing of a broad scope of issues reflect strong sensitivities to topicality that one would – and should – expect from a contemporary art gallery.

Endnotes

1. “21st Century Landscapes,” Petzel Gallery, accessed August 27, 2020, https://www.petzel.com/viewing-room/21st-centurylandscapes. 2. “21st Century Landscapes,” Petzel Gallery, accessed August 27, 2020, https://www.petzel.com/viewing-room/21st-centurylandscapes.

HART2275 ITALIAN RENAISSANCE ART NOW Unit coordinator: Arvi Wattel Teaching Assistant: Michelle Rankine DANIELLE BROOKS

‘La Fornarina will see you now’

The male gaze has played an influential role in the way that women are perceived and portrayed in art. Through the centuries, women have been objectified and sexualised for the benefit of privileged men in an industry of artists that was predominantly male-dominated. Today, these individuals are recognised as the Old Master due to their extensive artistic career and welldocumented writings by the early art historian Giorgio Vasari in his book titled The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. 1 To highlight the role of the male gaze this essay will demonstrate how Italian renaissance art has influenced the contemporary art world by examining American artist Cindy Sherman’s, Untitled #205 (1989) and comparing the work alongside Raphael’s, La Fornarina (c.1518).

The portrait titled La Fornarina (1518-1519) was created during the period known as the High Renaissance by artist and Master Raphael.2 The painting uses oil paints on a panel with the central subject matter being that of a beautiful young woman that is posing nude only covered from her waist down. The use of chiaroscuro is used to illuminates the entire female figure from La Fornarina’s righthand side while the darkened landscape background frames the young woman. The portrait provokes a naturalistic style that accentuates the beauty of the woman’s appearance harmoniously and perfectly. Raphael has portrayed La Fornarina’s soft femininity by his use of a soothing colour palette, selecting light

Image: Raphael. La Fornarina. Oil on panel, 85 x 60 cm. Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome. C.1518-19

pinks to emphasise the flushness of her cheeks, and his handling of the paintbrush to creates delicate shadowing brushstrokes that give her figure form and the impression of smoothness. No detail is lost when looking at the soft folds made by the sheer white fabric that acts as a veil while the woman suggestively lifts the cloth to cup her left breast in what can be described as an erotic and intimate moment. La Fornarina is also covered by a pink sheet that rests on her lap and drapes into the lower picture pane, entering the space of the audience. Due to the coy expression and gaze from the young lady, a fair assumption could suggest that she is quite comfortable posing for her portrait and that she may be intimate with the artist or welcomes the attention of her viewers. Other features observed on La Fornarina is her perfectly positioned hair with her neatly wrapped dark blue and gold woven turban that is adorned with a small intricate brooch. Raphael has asserted ownership of his artwork by including his name written in gold script within La Fornarina’s armband. The inclusion and placement of the artist’s signature could suggest that the artist is laying claim to the young woman in the portrait.

From 1988 through to 1990, Cindy Sherman produced a photographic series that was titled ‘History Portraits’ . 3 Sherman worked on her History Portraits collection during a two-month stay in Rome where she resided at a studio in Trastevere. 4 Sherman chose not to see the works in person but preferred to study the portraits of Italian and French artists from either reproductions or books.5 Arthur Danto has stated that Sherman had not visited the Palazzo Barbarini where La Fornarina was displayed and therefore had worked exclusively from copies of Raphael’s work.6 The iconic resemblance to Raphael’s painting is observed in Sherman’s Untitled #205, where she depicts her version of a portrait containing a young woman titled La Fornarina. Sherman has chosen photography to capture her image, followed by photographic printing techniques to create a chromogenic colour Kodak C-print of the portrait Untitled #205 (1989). 7 The process involves the colour negatives to be exposed to chromogenic colour paper before they are submerged in a chemical bath to create the final colour image.8

The image is visually reconstructed by Sherman, where she places herself as the central character. Sherman has re-created an elaborately staged scene where she has transformed herself with her hair neatly pulled back into a loosely wrapped turban, wearing only a purple armband and what looks like a somewhat grotesque prosthetic bust with a pregnant stomach. The woman sits on a chair, loosely draped with a lace cloth that covers her lower body as the folds of lace curtaining enter the lower picture pane into the viewers’ space. Sherman has utilised chiaroscuro to emphasise the contrast between the dark floral brocade cloth background and light to highlight the female prosthetic figure that acts as body armour. The use of light not only highlights the female form but also emphasises how disturbingly false and imperfect the woman is in comparison to classical works from history. The strangeness of the created image makes the onlooker feel like they are intruding in a private moment. The emotive feeling is reinforced by the intentional and challenging harsh gaze of Sherman in response to the viewer’s gaze; Sherman attempts to reclaim the woman’s female identity during the captured moment. An amplified feeling of annoyance is expressed by Sherman by the woman’s facial expression as seen by the tightening of her mouth and what appears to be exhaustion produced by the darkening around her eyes. The fully reconstructed portrait emphasises

how the female form can be imperfect, false, less desirable, and deliberately unwelcoming to the attention of unwanted gazes.

In contrast, the two portraits reflect the same young woman La Fornarina, but they both have apparent differences in their portrayal. One such comparison involves the scale of the image that reflects the purpose of the artwork. Raphael’s portrait measures 85 x 60cm and is relatively small; one assumption is that the painting was being created for a private collection for display in a home due to the sensual nature of the image. Sherman’s Untitled #205 is substantially larger measuring at 135.89 x 102.87cm and was designed to be viewed by the public as part of her exhibition. Sherman’s image was produced on a much grander scale; Untitled #205 appears to be life-sized and designed to be confronting to the viewers by stresses the exploitation of the female body. In respect to the work named Untitled #205, the constructed image can be described as a performance piece where Sherman personifies the central female character that ultimately demands an audience and highlights how the Old Masters have portrayed women as objects throughout the centuries. Untitled #205 applies techniques inspired by renaissance artists specifically the use of composition, light, positioning of the body and gaze while questioning the standards of sexuality and female ownership. Sherman’s ability to reconstruct Raphael’s artworks not only emphasises the rights of females to reclaim ownership of their body but also how they engage with the viewer. Sherman highlights how Raphael has utilised his male gaze as an aspect of privilege and sexualisation over the female form within his artwork. Sherman chooses to reclaim that same gaze in an authoritative or challenging manner, as observed in Untitled #205. Through the study of Raphael’s La Fornarina, Sherman has mastered

how modern technology, such as photography can capture a moment. Sherman is questioning the potential for fallacies within art as stressed by the prosthetic body part that is grotesquely beautiful in comparison to Italian renaissance artists who have strived for perfection and the beautiful.

Sherman’s theatrical performance in front of the camera lens is an original take on Raphael’s La Fornarina. Sherman chooses to push the boundaries not only as a female artist but also as a woman within the artwork as she questions the truth behind the images. While using photography Sherman has displayed techniques present in renaissance art to provoke and highlight how the male gaze was used during the Italian renaissance and in this instance by Raphael. Untitled #205, successfully creates a tension that puts the viewer and the woman in a very uncomfortable position that questions who has the authority to look; is it the viewer, the artist, or the woman. Ultimately, Sherman has giving La Fornarina a voice and the opportunity to reclaim herself in a modern world and society where women are more than just an object.

Bibliography

Biow, Douglass. Vasari’s Words: The Lives of the Artists as a History of Ideas in the Italian Renaissance. In Vasari’s Words:

The ‘Lives of the Artists’ as a History of Ideas in the Italian

Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press., 2018. Danto, Arthur C. Cindy Sherman History Portraits. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1991. Gombrich, E.H. The Story of Art. Oxford: Phaidon Press Limited, Littlegate House, 1984. Krauss, Rosalind. Cindy Sherman 1975-1993. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1993. TATE. “Art Term: C-Print.” Accessed September 9, 2020. https:// www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/c/c-print.

Endnotes

1. Douglass Biow. Vasari’s Words: The Lives of the Artists as a History of Ideas in the Italian Renaissance. In Vasari’s Words:

The ‘Lives of the Artists’ as a History of Ideas in the Italian

Renaissance. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press., 2018), i-ii. 2. E.H. Gombrich, The Story of Art. (Oxford: Phaidon Press Limited, Littlegate House, 1984), 218. 3. Rosalind Krauss, Cindy Sherman 1975-1993. (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1993), 166. 4. Arthur C. Danto, Cindy Sherman History Portraits. (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1991),11. 5. Ibid. 6. Ibid. 7. Ibid., 62. 8. “Art Term: C-Print,” TATE, accessed September 9, 2020, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/c/c-print.

Image: Cindy Sherman. Untitled #205. Chromogenic colour print, 135.89 x 102.87 cm. The Broad, Los Angeles, CA. 1989.

HART2043 ZEN GARDENS TO MANGA MANIA: A SURVEY OF JAPANESE ART Unit coordinator: Dr Emily Eastgate Brink AVA CADEE

“Time is floating in space; once a human interacts with it, it becomes a visual manifestation.” - Tatsuo Miyajima, 2000 Japanese understandings of time tend towards a non-linear, transient and circular temporality. Just as time itself is non-linear, so is history. The proposed exhibition centres around the central theme of the conception of time in Japanese history. Time in Japanese art can be explored from the emergence of Buddhism, towards the contemporary and digital mediums of the future in a non-linear and immersive and expansive tracing of temporality. Traditional historical retrospectives present us with a strictly linear idealisation of history, whereas this exhibition will focus on a more conceptual, experimental display of history. This exhibition seeks to present history, not as a timeline, but rather as a tree with various interconnected branches that both simultaneously inform and resist each other. This can be best articulated through a study of Japanese objects and how they interpolate this understanding of time.

The exhibition begins in a meticulous and meditative zen garden. Situated within the garden is a display of Takuro Kuwata’s abstracted Japanese pottery from the collection ‘Stone Garden, Heaven’. This series establishes the tracing of time through Japanese art. The viewer is able to draw connections between the contemporary abstractions of Kuwata’s pieces and the aesthetic imperfections and fluctuations of traditional raku ware that is housed within the teahouse. Raku pottery is a physical embodiment of the Japanese aesthetic concept of wabi, the beauty in imperfection.1 This concept is closely tied to ideas of temporality as it relates to the fleeting beauty and transience created through the natural forces of time. This is manifested in the hand moulded organic shapes or cracks on the pottery glazes. Early Buddhist works, such as the ink paintings presented within the tea house, utilise this aesthetic to appreciate the fluctuating temporality that arises within natural imperfections.2

Born in Hiroshima in the aftermath of the atomic bombs, Kuwata’s works are influenced by the hybrid mutations of traditional tea ware that became transfigured as collateral from the nuclear bomb.3 The sense of temporality emerges within Kuwata’s works through his use of traditional Japanese techniques such as ishi-haze, the use of placing stones into the glaze that erupt into explosive forms, and kairagi, the manipulation of glaze to create shrinkages and cracks.4 These techniques create an uncertain organicism to the pieces, leaving the materials to interact and disfigure under heat, time and natural processes. The beauty of Kuwata’s relinquished control harks back to the temporal wabi aesthetics of raku pottery that is displayed further along in the exhibition. This invites the viewer to consider the links between these two items, yet displaying them in an anachronistic order positions visitors to consider the pieces in a thematic linkage of temporality that fractures and deviates, just like the imperfections within the pieces of pottery on display.

Time is suspended, warped and intensified in the emerging Ukiyo-e art movement. During the Edo period, the Tokugawa shogunate established particular areas for entertainment, teahouses, theatre and prostitution.5 This allowed art and

entertainment to flourish amongst the emerging merchant classes, with innovations in printmaking leading to the mass proliferation of Ukiyo-e artworks.6 Ukiyo-e, or pictures of the floating world, explore temporality through the woodblock print. The intricate and fantastical floating world was derived from the Buddhist concept of ukiyo, the suffering caused from worldly attachment.7 The reading of the Buddhist term ukiyo (憂き世) is homonymous with the reading of ukiyo (浮世) as the floating or transient world.8 This wordplay signifies a slippage between pleasure and suffering that is embodied within the ukiyo-e artworks. Within the bright colours and bold lines of ukiyo-e are references to circles of birth, death and rebirth within Buddhist thought.9

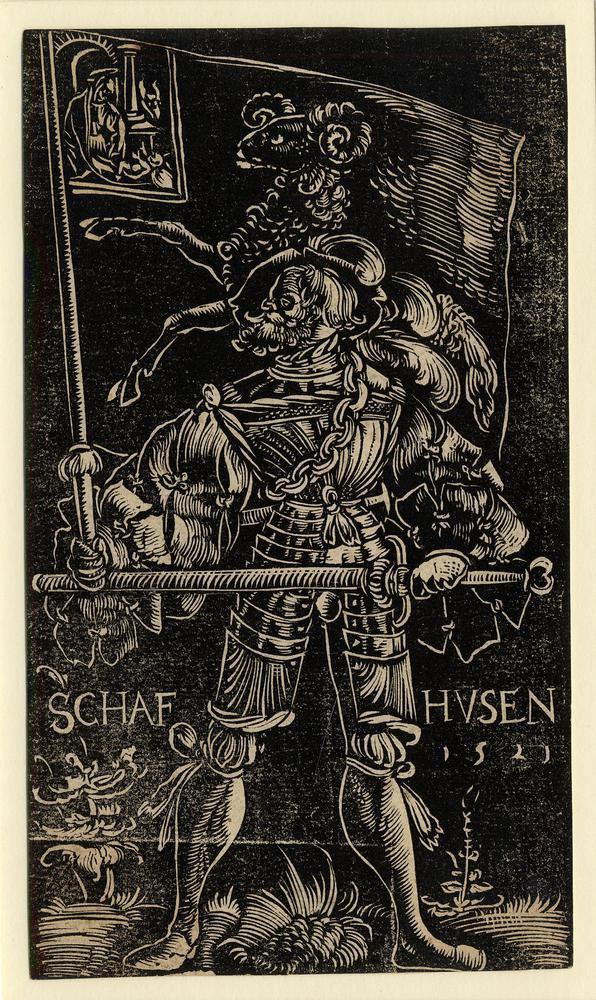

The print of Nihonbashi, from Utagagawa Hiroshige’s collection “The Fifty-Three Stages of the Tokaido” draws the viewer into the floating world. Nihonbashi represents a crossing of the bridge between worlds. The bridge is an important symbol within in Japanese mythology as it suggests the connection between the human world and more esoteric spaces.10 A close analysis of this print reveals fine details that place the viewer at the beginning of a journey and invite careful contemplation. The cartouches title the piece and situate the viewer within a real place.11 Nihonbashi begun the journey from the Edo capital to Kyoto along the Tokaido road.12 In the foreground of the image, a group of fishmongers set out across the bridge, followed by an orderly feudal procession.13 The juxtaposition between these figures creates a sense of bustling energy that draws the viewer further into the floating world. Moreover, Hiroshige’s use of colour and composition creates an other-worldly atmosphere that detaches from the mimetic view of a bridge. Situating the viewer on one end of the bridge within the picture’s perspective, washes of red over the cityscape evoke a warm and hazy atmosphere.

Image: Utagawa Hiroshige. Woodblock print; ink and colour on paper, 24.1 cm x 35.2 cm. 1833.

There is an uncanny sense of temporal suspension created through the contrast of the deep blues and red tones in the sky. The introduction of Prussian blue pigments in Japan allowed for innovations in Ukiyo-e prints and their representations of temporality. The use of Prussian blue is deepened through the use of the Ukiyo-e technique ichimohi-bokashi (straight line graduation) across the top of the picture.14 This technique creates a gradient across the sky that adds a sense of depth and frames the image in a floating, temporal suspension. This deep and inviting blue foreshadows the blue diodes in Tatsuo Miyajima’s installation that appears at the end of the exhibit. Similar to how Prussian blue changed the landscape of Hiroshige and Hokusai’s iconic works, the development of blue LED lights into Japan allowed Miyajima to innovate with blue throughout his oeuvre. These links across each object seek to reinforce the viewers ability to trace the themes of the exhibition throughout each work as they trace Japanese history through the passage of time.

The significance of this piece within the overall exhibition points towards the various border crossings between worlds, history, time and art. The bridge transports the viewer into the floating world of pleasure and delight. Amongst other ukiyo-e prints such as the whimsical bubble-blowing goldfish and otherworldly moon pine, a sense of transient temporality envelops the viewer.

Endnotes

1. Morgan Pitelka, Handmade Culture: Raku Potters, Patrons, and Tea Practitioners in Japan, University of Hawai’i Press, 2005. Accessed October 19, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/j.ctt6wr385. 2. Yuriko Saito, “The Japanese Aesthetics of Imperfection and Insufficiency,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art

Criticism 55, no. 4 (October 1, 1997): 377–85. https://doi. org/10.2307/430925, 382. 3. Anna Sansom, “Last Chance to See Takuro Kuwata’s ‘From Tea Bowl’, Damn Magazine, November 2016, https:// www.damnmagazine.net/2016/11/04/last-chance-to-seetakuro-kuwatas-from-tea-bowl/. 4. Eva Masterman, ‘Are you going out, Teabowl?’ by Takuro Kuwata at Galeria Mascota’, Cfile, April 3, 2019, https:// cfileonline.org/feature-are-you-going-out-teabowl-bytakuro-kuwata-at-galeria-mascota/. 5. Department of Asian Art, “Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http:// www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/plea/hd_plea.htm (October 2004). 6. Frederick Harris, Ukiyo-e The Art of the Japanese Print, North Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing, 2012, 11. 7. Steven Heine, “Tragedy and Salvation in the Floating World: Chikamatsu’s Double Suicide Drama as Millenarian Discourse,” The Journal of Asian Studies 53, no. 2 (1994): 367-93. Accessed October 19, 2020. doi:10.2307/2059839. 8. D, Keene. (1996). Japanese life in the Edo Period as Reflected Department of Asian Art, “Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style.” in Literature. Estudos

Japoneses, (16), 11-26. p14. 9. Bell, D. (2004). Explaining Ukiyo-e (Thesis, Doctor of Philosophy). University of Otago. Retrieved from http://hdl. handle.net/10523/598, p114. 10. Michael Lazarn. “Phenomenology of Japanese Architecture: En (edge, Connection, Destiny).” Studia Phaenomenologica 14 (2014): 133–59. https://doi.org/10.5840/ studphaen2014148., p137. 11. Emily Brink, “Ukiyo-e: Japan in Print” (lecture, University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA August 26, 2020). 12. Cat Jensen, “Nihonbashi and the Floating World: Hiroshige’s First Stage of the Tōkaidō”, Medium, June 6, 2018, https:// medium.com/@jensen.ca88/nihonbashi-and-the-floatingworld-hiroshiges-first-stage-of-the- t%C5%8Dkaid%C5%8Dc1dce0c0407c. 13. Ibid. 14. G Hickey, “The ukiyo-e blues: an analysis of the influence of Prussian blue on ukiyo-e in the 1830s,” Masters Research thesis, Arts, The University of Melbourne (1994), 28.