BADGER INQUIRY ON SPORT BIOS

FOUR BIG IDEAS: VOLUME 1

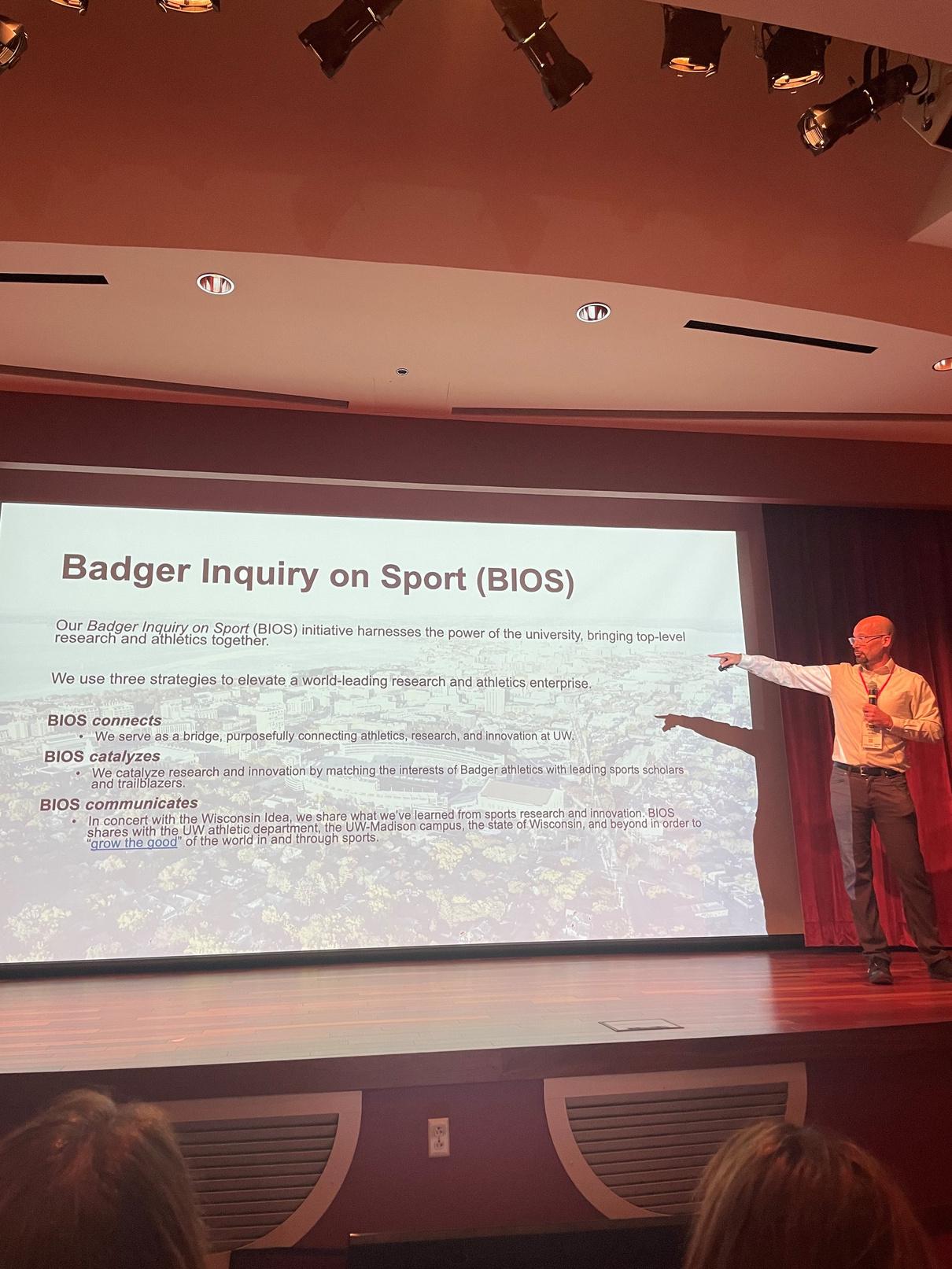

Badger Inquiry on Sport (BIOS) is an exciting research and innovation initiative based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. We bring together top-level research and athletics for the benefit of the Badgers and the broader state. We use three strategies to carry out our work:

BIOS connects. We serve as a bridge, purposefully connecting athletics, research, and innovation at UW. We’re building a robust sports research community in our beautiful Camp Randall Stadium lab! Relationships are at the heart of our work.

BIOS catalyzes. We initiate original research studies to improve the Badgers, the state of Wisconsin, and the field of athletics. Our research is led by some of the world’s top scholars. The BIOS-sponsored "How Coaches Connect" study, launched in 2022, is the first of many more empirical studies to come.

BIOS communicates. We share what we’ve learned. BIOS disseminates our learnings on campus and throughout the state to the student-athletes, coaches, administrators, staff, families, and communities that make Wisconsin sports so special. We’re excited to meet you, learn from you, and share with you.

BIOS is an action-packed lab. We hosted over 25 research seminars, poured over hundreds of research articles, explored cutting-edge sports innovations, initiated a statewide study of coaching, and picked the brains of leading athletics experts across multiple disciplines. In concert with our aims to improve athletics though research, we’ve synthesized some of the year's most important learnings into Four Big Ideas: Volume I.

Coaches can best lead by cultivating meaningful connections. Youth sports can become healthier, more fun, and more accessible. Mental health must be proactively addressed in and through athletics. Collaboration is necessary in promoting brain health and concussion prevention.

1.

2.

3.

1.

2.

3.

COACHES CAN BEST LEAD BY CULTIVATING MEANINGFUL CONNECTIONS.

Sports coaches are among the most impactful leaders and educators in society. Nationally, 43 million youth participate in organized athletics. Thousands of college and professional athletes also compete each year. For good and for bad, coaches shape these multi-level sporting experiences. BIOS researchers are learning from hundreds of coaches in and beyond the Badger state. We launched the "Wisconsin Coaching Project,” a rigorous empirical study of how the best coaches go about their everyday work. Here, in BIOS Volume 1, we offer some initial findings. Our study aims to contribute to the improvement of coaching across sports and levels.

We found five key themes relative to how coaches connect.

A first and foundational finding of the WCP study is that coaches connect through authenticity. The 77 coaches that we interviewed described different ways of teaching, communicating, and running systems. Despite these differences, the participants consistently identified one of their earliest and ongoing leadership challenges as moving from “imitating what other coaches do” to “knowing and being my authentic self.”

Before meaningful connections can be forged with others, coaches reflected upon themselves as leaders (and encouraged other team members to do the same). They deepened their awareness of “what makes them tick."

Authenticity was commonly described by participants relating to personality (e.g., “don’t be a screamer if you’re not a screamer”). It was also described pertaining to strengths and weaknesses (e.g., “know what you’re good at. Know what you’re not good at”).

In a more complex way, authenticity was articulated as it played out at the blurred boundaries of authority and vulnerability. As leaders, coaches highlighted their accountabilities and the importance of “being in charge.” They also noted that a strength of leadership includes big doses of humility. Being vulnerable with teams is an act of authenticity. Some coaches described this vulnerability as owning up to mistakes. Others told stories of how they were straightforward with teams about uncertainty and doubt.

“You don’t always have to know the answers…or even to act like you know the answers."

Authenticity findings were also evident at the collective team level. Many of our study participants described how they connected with each other around their shared team identity. We learned from coaches whose teams had certain styles of play. The teams bought into the styles and bonded around taking that identity to every competition. “We are tough,” “We are resilient,” “We play fast.” These types of shared identities, rooted in the teams’ deepest characteristics, bonded teams.

Others noted authenticity as it played out in certain subgroups among the team. One high school football coach described the strong and enduring bonds of offensive linemen in his program. They build shared identity by “staying true to what we’re all about and have always been about in this position group.” Over the years, a tradition of linemen emerged as a visible and enduring source of bonding for all who were a part of that small group.

The key takeaways relating to authenticity?

• Be yourself.

• Be transparent.

• Hold yourself to high standards ...while finding spaces to be vulnerable with team members.

• As a group, stay true to the collective identity that you’ve built and sustained together.

Selected authenticity quotes from participants...

"You don't treat all the players the same because they're not the same."

"It takes five years to get comfortable."

"I bring all of who I am to the court."

“You can’t win with people you don’t know...If you’re doing it right, your kids should be connected to each other to the point where they can tell when someone’s going through something.”

“I am a teacher…I’ve always known that.”

“If you don’t give them the whys, then they’re going to create their own.”

“Kids see through you… you can only be honest if you’re going to be successful with them...The ability to lead is based solely on trust and trust can only occur if you’re truthful.”

“We're going to throw strikes. We’re going to make routine plays. And we're going to run the bases. I picked three things and we're going to do these three things. And if we do them well, we're successful.”

"You never want to go down to anybody else's standards. You want to set your standards and reach for them.”

The coaches we studied cultivated team bonds by sharing time and experiences with their teams outside of traditional team spaces. Coach Malik 1 highlighted his professional team’s “breaking bread” tradition of going out to eat after road games. Basketball discussion was prohibited at these meals. Rather, the players, coaches, and families talked about family and life in general. Coach Loraine similarly spent time in purposeful ways with her coaching staff. Away from practice, she invited her staff for regular Sunday meals at her home. She also pursued a Bible study course with interested coaches and staff members. Callie, a high school volleyball coach, organizes ongoing community service projects with her team. Volunteering each month with the Special Olympics organization, teammates came to develop appreciation for each other, the children they worked with, and their overall sporting experiences. Across the 77 coaches we studied, coaches’ commitments to getting away from the action with their teams to get to know each other beyond athletics was a critical aspect of their connectionmaking.

Not all shared experiences were outside of the teams’ athletics venues. Mike, a former coach turned professional team leader, told us about his philosophy of “managing by walking around.” He explained that “most people aren’t comfortable coming to the office to speak with the boss. I can learn more about them by making the rounds each day to say hello in their own spaces.” Mike shares in the everyday experiences of members of his organization in small, but very frequent ways. Everyone in his large team organization knows him and expects to see him most days as he walks the halls. Importantly, his daily walkabouts are not conducted in a surveillance mode, but in spirit of openness and trust-building. Members of Mike’s organization, including his team’s head coach and the general manager, told us that Mike’s sharing in daily experiences across the organization is contagious and builds a culture of inclusion and understanding.

1 Pseudonyms are used in this document to maintain coaches’ anonymity.

The team’s head coach, Randy, explained, “He’s led by example and that’s taken root throughout our organization.”

Two other examples of connection-building that emerged within the shared experience theme add nuance to the strategy. First, Vince, a veteran high school basketball coach, invites parents to sit in on practice anytime they want. He tells parents, “Come and see how hard your son works.” Although many parents don’t take him up on the offer, his mere invitation to them to join the experience of daily practice creates a deeper sense of buy-in across the team.

And finally, we found that shared experiences can be meaningful even when they do not include the coach. That is, sometimes the best thing a coach can do to forge connections is to step back and allow others to form them on their own. One coach told us, “I have such a strong personality that I realized a long time ago that sometimes I don’t need to be around.” We learned of coaches who created regular time for just the players to have conversations. Others designed ways for pre-game locker room time to be players only – a special bonding time at peak points of vulnerability and competition. The key takeaways relating to shared experience?

• Find times and places away from your sport to get to know members of your team.

• Design times and places where team members can share experiences away from coaches and authorities.

• Consider inviting families and other stakeholders into selected team functions.

Selected shared experience examples from participants…

Take part in pre-practice warm-ups with the team

Work out with the players

“Side-by-side" conversations while walking, driving, flying Team community service projects

Shared faith or self-development experiences

Bowling, paint ball, and other “fun stuff”

Ropes courses and other formal team-building experiences

Attending players’ other sports competitions

Managing by walking around

Designing shared experiences for players without coaches present Inviting parents to practice

Destination retreats (mountains, lake, camping, etc.)

Our participants described adaptability as a critical aspect of their connection-making with teams. At a foundational level, the coaches described how maintaining dispositions of openness and curiosity in their leadership styles was at the root of their adaptability. Joanna, a longtime high school volleyball coach noted that even as she won many championships, she remained committed to personal growth as a coach. "I needed to continue to learn…I always wanted to know new things. I wanted to know how I can make my athletes better.” Her perspective contrasted those of some coaches who, after having been in the profession for years, assume they “know it all.” For many of the participants, openness and curiosity included not only their coaching beliefs in the technical domain (scheme, Xs and Os, strategy, etc.) but also in social/relational ones. For example, Mary, a former college basketball coach, noted that after 30+ years of coaching, she realized that her tone with players needed to change. She began purposefully integrating more encouragement and personal time with her players. She even began having her team managers video record her during practice so that she could analyze her body language and tone of voice with her team. She committed to engaging them in new ways – and the effects were deeper bonds with both players and coaches.

Coach Brett described a similar late-career change even more broadly. He re-focused on the “why” of coaching. "Young coaches look at the scoreboard...As I got older and more seasoned, looking back, as much as I took from wins and losses, I realized that, you know what, if I'm going to determine my success on the scoreboard, I'm never going to be good." Coach Brett came to view his work with high school students as an opportunity to develop young people for life.

Beyond a personal openness to learning and change, many of the coaches we interviewed described their teams as having “cultures of tweaking” in that they always sought little changes to freshen things up for their teams. One college wrestling coach changed practice time from 6:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m. A high school basketball coach retooled his offensive scheme to meet player strengths. A high school softball coach altered off-season training regimens to accommodate family schedules. Within her steady system of routines and principles, club soccer coach Jessica explained, "We're always kind of tweaking...the athletes were involved in this tweaking." The athlete participation in tweaks emerged as the key “connective” aspect here, as their empowerment in team processes instilled a stronger collective ethos among the teams. Some coaches’ perspectives on tweaking were unstructured, but others were purposeful. Joanna recalled, "I would ask them, ‘what do you think we need to work on?’ And I'd write it down and then I would incorporate that into my planning." Her regular seeking of and response to player feedback fostered a dynamic and connected team practice environment.

Farthest along the continuum of adaptability were the coaches who willingly and purposefully pursued larger-scale systemic change in their programs. Many of these changes were aimed at “keeping up with the world around us” and winning games. But by keeping current in the ways their teams played, coaches described their programs as becoming more vibrant and engaging environments for all. Players and coaches alike were drawn to new ideas. The most interesting example of systemic change that we learned about was from Coach Paul, a highly-acclaimed high school football coach. Amid

a string of multiple state championships, Coach Paul surmised a need to “stay ahead of the game” and overhaul his team’s entire scheme. He switched from a traditional power running game to a wide-open passing strategy. Coach Paul saw a competitive advantage in changing schemes “before everyone else did it” and, in his forward thinking, extended his program’s appeal to young people. He challenged his entire program – the coaching staff and players alike – to embrace change. They spent countless hours together learning the system. Their new way of play was fast-paced and high scoring. It was fun. Coach Harris took a significant risk in making the change. Not many coaches in the midst of a winning dynasty would likely made the same decision. The risk paid off with yet another championship the following year – and with a team culture that, through shared commitment and new learning –was more connected than ever before. The key takeaways relating to adaptability?

• Commit to ongoing learning and evolution relating to how and why you coach.

• Develop a culture of tweaking and innovation.

• Embrace systemic change periodically and invite others into the fold in making change happen.

A fourth theme that emerged indicates that what we refer to as “connecting tools” are specific, practical ways that coaches foster relationships on their teams. We synthesized our findings across several categories of connecting tools.

At a most basic level, several of our study participants described their sports/teams as themselves being fundamentally geared toward connecting. Coach Vincent started a highly successful AAU basketball program, not searching for wins, but for a hook, something that would keep the kids coming back each day. Coach Vincent wanted to be a positive influence on lives, and basketball brought boys together in a special, sustainable way that he alone could not. “I asked, ‘where is the passion of the

young people?’ and it was with basketball. And there was a court right down the street…I had to find a way, if I was going to make a difference, how can I get them to want to be with me every day? It wasn’t because I was a great guy. It was because of the basketball.” Basketball became a tool for social impact for Coach Vincent. He won many games and even helped produce some professional players – but the wins he sought were deeper, more meaningful advancement toward fulfilling lives.

Coach Jeff a high school football coach, embraced a similar “game as tool” philosophy as Coach Vincent and numerous other coaches. Keeping his eyes on the big picture in high school sports, explained his inclusive way of team-building: “There are some kids who need football more than football needs them.” Kids “need” football, Coach Jeff explained, because it connects them to trustworthy coaches, teammates, and behavioral norms.

Coach Ben, another football coach interview participant, added nuance to the game as tool philosophy, highlighting the importance of “being real” with kids –repeatedly emphasizing the broader connecting lessons of football rather than any farfetched dreams kids have of making it to the highest levels of the game. “Less than 1% of QBs will make it, so I keep it real with them and always let them know why we’re really here

it's bigger than just the game.”

Coach Latish, a college basketball coach, told us that her program’s foundational principles bind her team together at multiple levels. A large banner with the principles winning mindset, integrity, selflessness, communication, and legacy – hangs prominently in her team’s practice gym. She noted that she regularly refers to the principles in all facets of the team’s everyday time together. Similarly, at least ten other interview participants told us that their teams’ relationships flow in and through their shared principles (also referred to as values and/or pillars). Most of the coaches visualized their principles with banners like Coach Latish and/or in other ways such as on clothing and in team correspondence.

Many coaches integrated lessons about their principles and even used principles for assessing their shared successes and failures. Kenny, a retired college basketball coach, utilized the principles of unity, servanthood, humility, passion, and thankfulness to develop a beloved and admired program. The principles served as both rallying point and sensemaking framework for his teams over many years of impactful leadership. While Coach Kenny’s principles remained steady over the years, others allowed players to develop their own new ones each season. Whether holding constant over time or changing from year to year, the many coaches from whom we learned about principles as connecting tools showed that some of the most meaningful bonds on teams can be built around clear, shared ideas.

Coaches spoke about using technology to connect their teams. Some used simple strategies such as texting and social media to communicate with individuals and groups on their teams. Direct face-to-face communication is still the preferred mode of connecting for just about all the coaches we studied, but they largely, sometimes begrudgingly, accepted that the best way to efficiently communicate with their teams is, in many instances, to “connect using the ways the kids connect.” Some coaches highlighted creative ways of utilizing technology for reaching subgroups within and beyond their programs. Coach Antonio, a high school girls basketball coach, described a cross-generational connective strategy: "We have a group text where we actually still have former players who stay connected to the current players and help them through some of the adversity, stresses and pitfalls that they may have experienced when they were in high school."

Beyond simple texting and social media platforms, multiple coaches embraced advanced sport-specific technologies in order to engage the “gadget-captivated” generation of athletes on their teams. AAU basketball Coach Steve explained how he and his staff use “Shot Tacker,” a multi-layered software tool that allows teams to register every shot a player takes and where the shot is taken from in every practice and

game. Vast pools of data are analyzed and visualized in captivating ways that foster what Coach Steve described as “friendly competition and banter” among teammates. Each day’s team conversations are fresh and anchored to performance data. Players were, according to Coach Steve, both motivated and connected by Shot Tracker. Similar advanced technological tools were found to be used in volleyball, football, and soccer. We learned that some veteran coaches stepped out of their comfort zones in embracing the connective possibilities of technology. Longtime women’s college basketball Coach Mary told us that she resisted texting and social media for years. She sensed growing relational distance between herself and her young teams, so she started learning slowly about how to communicate in new ways, both directly and to a broad national audience. She viewed “texting and Twitter” as areas of substantive professional growth. Before long, the seasoned coach claimed to enjoy her new modes of engagement. Other veterans, like high school football coach Paul, were less personally adventurous with technology but hired new “techy young guys” to be parts of their coaching staffs. Distributing responsibilities across the whole coaching unit, new technologies could be used by even the least tech-savvy older coaches. Written documents as connective tools

Technology was not framed by most coaches as a replacement for some decidedly old-school ways of sharing ideas in written form for connection making on teams. Personal journals, team handbooks, multi-use binders, and staff policy guides were basic if not highly effective bonding tools used by many of the coaches we studied Philip, a college women’s volleyball coach, showed us an annual team handbook that he and his staff assemble which includes everything from the broadest of team principles to the very minute details of how they are to communicate with each other. The team deeply reads and re-doubles back to the handbook together throughout each season –to the point to which it has become a defining learning tool of their successful program.

Another fascinating written document was found in the work of college strength and conditioning Coach Brent. Coach Brent creates player binders that not only lay out

each day’s workout regimen, but also leave space for regular journaling and player reflection. Binders on players from past years can be found on the shelves of Brent’s office, allowing past players to check out both what past players did (how much weight they lifted, how fast they ran, how many repetitions they completed, etc.) and what they were thinking during and after they completed their exercises. Members of the program were connected across generations through the binders.

Two other coaches, Kevin, a high school football coach and Joe, a retired college football coach, utilized weekly player writing activities to draw them into conversation with coaches and teammates around specific, meaningful content. Coach Kevin’s players completed “purpose statements” in notebooks that were shared with coaches. These purpose statements challenged players to discuss their deepest reasons for playing the sport with others. Coach Joe required players to submit weekly “truth statements,” which addressed team members’ efforts to be good students and good citizens away from the football field each week.

One final example of writing as a connective tool was seen in the work of Coach Joanna, who led her high school teams through guided journal writing throughout each season. Players were challenged to reflect upon their progress and how they were maximizing their potential. Their regular journal entries set the stage for rich, contentheavy conversations with her and the rest of the coaching staff.

Coaches used their teams’ physical spaces in a range of innovative connective fashions. Philip described such a commitment to strategic spatial design in relationship and culture building that, as he walked us though his team’s locker room, team room, playing arena, and even hallways, he became increasingly animated. Coach Philip accounts for the “tenor and feel” of each room – to the point where he played an active role in designing seating arrangements in the rooms and pays close attention to where various types of messages are delivered. In fact, Coach Philip even provides specific

details about how and where every member of the team is to be in huddles throughout different parts of games.

Similarly, many coaches took advantage of spatial design to motivate, inspire, and connect their teams. Meetings in offices take on a different feel than conversations over lunch. Positioning of chairs in a room, shift conversational dynamics. Locker room layouts shape who engages with who. A professional football coach, Marvin, showed us a regulation-size basketball hoop mounted on the wall of his team’s large meeting room. The hoop was placed there as a fun bonding outlet for the group, which was otherwise almost constantly locked into the grind of their everyday football preparation.

One coach, Randall, was even aware of the location, design, and contents of the school’s trophy case. Rather than displaying championship trophies, MVP awards and the other typical items found in school trophy cases, Coach Randall included only the award recognizing the player who most exemplified team culture in the case. The message sent by Coach Randall was clear to all who walked past – culture is more important than short-term wins and individual accomplishments.

A final interesting finding was seen in the office location of professional football coach David. He purposefully requested that his office be located next to the team locker room. This high traffic spot ensured that Coach David would be highly visible to his team. It made short everyday conversations almost unavoidable. Over time, these small interactions helped Coach David to cultivate a level of trust that fostered greater collective efficacy on the team. The key takeaways relating to connecting tools?

• Recognize that the game itself can be shaped as a connective tool.

• Seek deeper understanding of the everyday tools already in the lives of team members – and employ them for team purposes.

• Value both new technologies and old in everyday connecting.

• Consider how spatial design can be optimized to foster quality interactions.

Selected connective tools examples from participants…

Notebooks, journals

Handbooks

Technology (e.g., social media)

Shared language

Legacy connections (binders, jersey #s)

Spatial designs (locker rooms, meeting rooms, offices, etc.)

Metaphors (team flag, team coin, etc.)

Meals

Music

Humor

Finally, one of the more noteworthy WCP findings relates to what we refer to as “turning point action.” Numerous coaches described their everyday work as being marked by regular routines and consistency. But amid this larger normalcy, coaches identified certain points in their relationships with teams, players, and staff members that are especially high stakes turning points.

Coaches suggested that turning points can make or break connections. Coaches who purposefully look for and actively respond during turning points describe deepening relationships during and after these times.

We identified four main clusters of turning point action: 1) When members of the team (players and/or staff) are new to the group; 2) When players are injured; 3) When things “aren’t going well”; 4) When a critical incident occurs. Multi-level vulnerability and risk are present during these periods.

The same vulnerabilities and risks that bring feelings of stress and hardship can create conditions ripe for deepened connection. And, as much as opportunities for deepened connection are present during turning points, so are opportunities for relational breakdown and isolation. When team members are neglected or avoided during these periods of vulnerability, their likelihoods of connecting in deep, meaningful ways with the coach/team are diminished in the future. As such, we found these to be

“high stakes times” when connections will either rapidly accelerate or quickly break down. Coaches should be highly attuned to turning points with their players, staffs, and teams. These times can be leveraged for stronger connection and greater collective success.

The key takeaways relating to turning point action?

• Periods of vulnerability are turning points – when connections will deepen or fracture.

• Coaches must actively monitor their team environments for individual and collective vulnerability.

• Proactively engage vulnerable individuals in timely, formative, caring fashions.

Selected examples of connective coaching practices at turning points from participants…

Provide those who are new with: ongoing orientation, clear communication, clear information, and supportive mentors.

For those who are injured: monitor/prevent social isolation, design new roles with team, include them in travel and meetings. When things aren’t going well: Provide formative feedback, clarify routes forward, monitor and respond to player affects – offer encouragement amid dejection, embrace “in it together mentality.”

Amid/after critical incidents: Address incidents openly, create forums for respectful dialogue, consider whether group action is appropriate, build individuals’ capacities for engaging difficult issues.

YOUTH SPORTS CAN BECOME HEALTHIER, MORE FUN, AND MORE ACCESSIBLE.

The field of youth sports in America is at a critical juncture. A series of sport participation trends, in intersection with trailblazing research, reveal this period to be full of both promise and peril. Millions of children receive innumerable benefits from athletics, including physical, social, and psychological development. At the same time, increasing problems associated with uneven access to sports, injury, and burnout cannot be ignored. BIOS took a deep dive into Wisconsin youth sports. We learned from scholars, embedded in sports settings, and scoured the literature. Here, in BIOS Volume 1, we provide a brief consolidation of important trends and findings in youth sports.

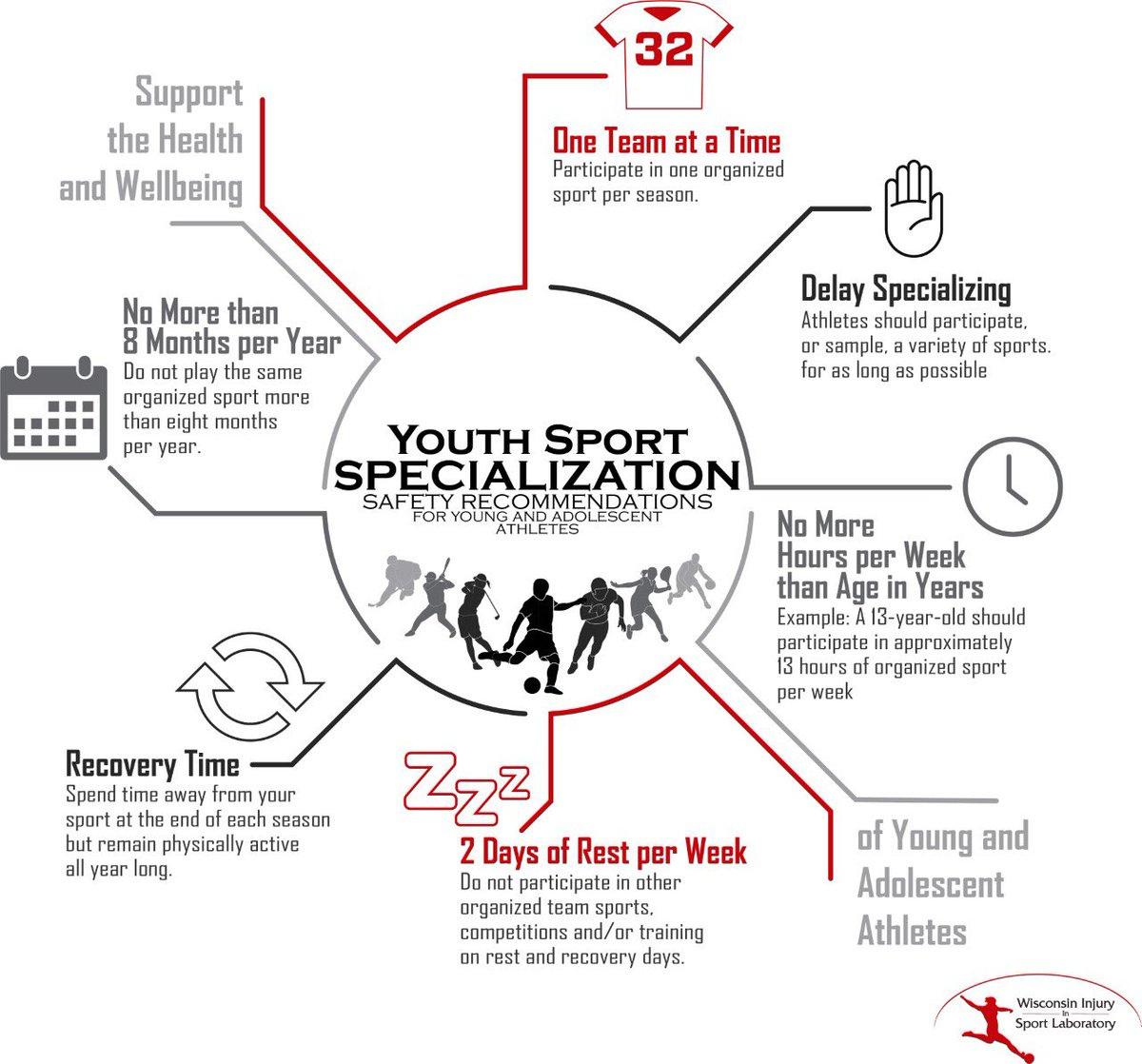

The“singlesportvs.multi-sport”debatemaybelessrelevantthan deeperunderstandingofbeing“highlyspecialized.”Highlyspecialized= 8+monthsperyearonasport.

Atleastninestudiesconductedsince2013havefoundthathighly specializedyouthathletesaremorelikelytoexperienceinjury(upto 5.49X).

Pastinjuryinyouthsportsheightensriskoffutureinjuryinsport.

Childrenshoulddelayspecializationaslongaspossible.

Childrenshouldnotspendmorehoursperweekonasportthantheir age.

Childrenshouldtakeatleastthreemonthsawayfromtheirsporteach year(inatleastonemonthintervals).

Thebiggestpredictorofyouthsportparticipationisparents'income.

Childrenfromlow-incomefamiliesarehalfaslikelytoplaysportsas kidsfromupper-incomeshomes.

Familieswithhigherincomesaremorelikelytohighlyspecialize.

Parentalattitudesandbehaviorsregardingyouthsportscantakeshape inthefirst18monthsoftheirchildren’sparticipation.

Over60%ofparentswillpaybetween$1,200to$6,000peryearon theirchild’ssports,withnearly20%ofparentspayingclose$12,000per year.

Parents who invest extensive time and money on youth sports commonly develop “return on investment” perspectives that endure beyond youth sport experiences.

Parent education in youth sports tends to address expectations around their interactions with the coaches and their children, but less frequently includes research on health and wellness.

Children who attend larger high schools are more likely to highly specialize.

Girls are more likely to highly specialize.

Club sports competitions commonly promote compressed schedules (e.g., “Your team is guaranteed to play at least five games before Sunday at noon!”).

Greater spending on youth sports was found to be associated with decreased enjoyment for children.

Noteworthy aspects of the competitive youth sport environment: early professionalization/messaging; detachment from school; travel; frequent transfers; parents as negotiators/managers.

70% of kids drop out of organized sports by age 13.

In 2018-19, high school sports participation in the US declined for the first time in recent memory.

The Midwest experienced the highest rates of decline in high school sports participation.

The proportion of student-athletes who are first-generation college students has decreased significantly since 2010 (including a 9% decrease in men’s basketball).

Broadly, the “effect lags” of the youth sports landscape will continue to shape the college and professional sports environments, perhaps with greater influence.

Children from low-income households are 6X more likely to drop out of sports in adolescence than children from middle and upper-income households.

Pandemic-era return to sport is lower for Black and Hispanic youth.

School-based sports tend to have broader benefits than club-based sports, but school-based participation numbers are dropping in some noteworthy areas. (For example, participation in girls high school basketball participants in Wisconsin drop by over 25% between 2002 and 2019.)

Percentages of children ages 13-17 participating in sports (2012 --> 2020):

Over $100k household income: 48% --> 50%.

White: 44% --> 44%.

Black: 51% --> 41%.

Low-income 38% --> 28%.

High school teams are composed at higher than ever proportions of “early specializers.”

This shrinking pool of recruitable student-athletes may already be evident at the highest levels of college sports. From the NCAA demographics database, note that between 2012 and 2020 the proportions of:

Student-athletes identifying as black in A5 football decreased 4%;

Student-athletes identifying as black in A5 WBB decreased 9%;

Student-athletes identifying as black in A5 MBB decreased 8%.

Primary sources:

David Bell, Associate Professor, UW-Madison Injury in Sports Laboratory

Travis Dorsch, Assistant Professor, Utah State Families in Sport Lab

Peter Miller, Professor, UW-Madison Educational Leadership and Policy

Aspen Institute, Project Play

NCAA GOALS study, 2015

MENTAL HEALTH MUST BE PROACTIVELY ADDRESSED IN AND THROUGH ATHLETICS.

BIOS focuses on a range of mental health trends and practices. We hosted numerous seminars to learn from campus researchers and specialists. We observed, participated in, and studied promising programs. Our areas of learning span a continuum from general research on mental wellness to specific insights in areas such as peak performance psychology and the research and practice on mindfulness/meditation in elite sport settings. Here, in BIOS Volume 1, we present some emergent findings to inform athletes, coaches, leaders, and other sport communities.

We’ve seen a steady increase in mental health concerns across broader youth and adolescent populations over the past 15 years. CDC trend data between 2009 and 2019 indicated:

A 40% increase in youth experiencing persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness (over 1 in 3 youth).

A 44% increase in youth reporting that they made a suicide plan in the past year (1 in 6 youth).

The students who will be arriving to universities in the next five years have experienced the problematic intersection of already escalating mental health concerns with Covid 19 and broader societal unrest. The lagging effects of their experiences will continue to unfold as they transition to college.

In 2021, more than a third (37%) of high school students reported they experienced poor mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic and 44% reported they persistently felt sad or hopeless during the past year (CDC, 2021).

Youth who felt connected to adults and peers at school were significantly less likely than those who did not to report: persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness (35% vs. 53%); that they seriously considered attempting suicide (14% vs. 26%); or attempted suicide (6% vs. 12%).

Fewer than half (47%) of youth reported feeling close to people at school during the pandemic.

School connectedness (in/post-Covid) is more important than ever in addressing youth adversities.

Participation in team sports may serve as a mental health protective factor through adolescent development phases and beyond. Those who discontinue team sport after adolescence report higher levels of stress and worse coping levels than those who continue sport participation into young adulthood (Murray, et al., 2021).

Trends among college students (Journal of Affective Disorders, 2022): In 2021, more than 60% of college students met the criteria for one or more mental health problems;

Mental health worsened for all racial and ethnic subgroups across the eight-year period;

Among all college students, between 2013 and 2021, researchers found:

134% increase of symptoms of depression;

110% increase in anxiety symptoms;

96% increase in eating disorders; and

64.0% increase in suicidal ideation.

In terms of service utilization, there was a 24% increase among all students in utilizing mental health supports from 2013 to 2021. Within this population:

Students of color had the lowest rates of mental health service utilization.

The highest levels of utilization among students of color subgroups were lower than the lowest rates of utilization among white subgroups.

Comparisons among college student-athletes and non-student-athletes (Kilcullen, et al., 2022):

Student-athletes consistently reported lower levels of distress than non-athletes across mental health subscales; Whereas student-athletes at Division 2 and 3 levels may utilize mental health services less frequently than non-athletes, athletes at Division 1 levels utilize the services at perhaps even greater levels than non-athletes.

All students demonstrated benefits from treatment. Across some domains of treatment, student-athletes demonstrated more change at the completion of treatment than non-athletes; College athletics programs may have unique opportunities for identifying risk and delivering prevention and intervention to students in need.

UW-Madison is engaged in mental health and wellness research on multiple levels. One noteworthy example includes UW's trailblazing work in performance and meditation training. The efforts are led by the country's only Division 1 Athletics Director of Meditation Training, Chad McGehee. Some notes about mediation training:

Meditation training can be viewed as strength and conditioning for the mind.

Meditation training gives individuals and teams the skills to 1) be aware of internal conditions, B.E.S.T.™ (Behaviors, Emotions, Senses, Thoughts) as well as external conditions with a sense of clarity and stability and 2) develop psychological and contemplative skills to navigate those conditions in the direction of greater performance and well-being.

The research on meditation in sports is just beginning, but there is evidence to suggest that the impacts include increased resilience, greater focus, reduced anxiety and depression, reduced perceived stress and improved sleep. This includes ongoing research being published on the meditation training happening at UW Athletics.

Collaboration with coaches and staff is essential; in particular the role of an internal champion on the team to facilitate implementation.

The personal practice of the meditation coach is critical and foundational to the impact of the training for athletes.

To stay updated on the work, you may be interested in following the Director of Meditation Training, Chad McGehee on Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn.

Primary sources:

Chad McGehee, Director of Meditation Training, Wisconsin Athletics

Lindsey Miller, Ph.D, UW-Madison Sports Leadership Faculty

Peter Miller, Professor, UW-Madison Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis

Kilcullen et al., 2022 Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology

COLLABORATION IS NECESSARY IN PROMOTING BRAIN HEALTH AND CONCUSSION PREVENTION.

Developments in the field of concussion research have spurred systemic changes at all levels of competitive sports. UW-Madison researchers are at the forefront of this work. BIOS learned from concussion scholars, pulling together insights for athletes and their support networks. We learned the science of brain health — including some socio-behavioral findings that contextualize advancements toward safer sports. Here, in BIOS Volume 1, we highlight several aspects of concussion research as well as the implications that these findings have for all who lead and compete in sports.

A player who experiences concussion symptoms should be removed from play immediately and should not return to play that day, even if their symptoms subside within 15 minutes.

You don’t have to lose consciousness to have a concussion. In fact, less than ten percent of concussions result in a loss of consciousness.

Concussions can happen even if you don’t hit your head. A blow to the body that causes the head and brain to move back and forth, like whiplash, can also cause a concussion.

Continuing to play after sustaining a concussion can lead to prolonged symptoms and delayed recovery from that concussion.

Returning to play too soon, before having recovered from a concussion, can increase the risk for sustaining a second concussion. It is important for athletes to be honest about their symptoms throughout the recovery process.

Children and adolescents are at greater risk of having a prolonged recovery and worse outcomes following a concussion compared to adults. It is important to manage concussions more conservatively and provide adequate time for their developing brain to heal.

Research suggests that children may be at higher risk of sustaining a concussion, even with lower-magnitude impacts.

It isn’t all about concussions. The repetitive “subconcussive” impacts that happen on nearly every play in some sports but don’t result in concussion symptoms also affect the brain. It is important to minimize these repetitive impacts to protect the brain.

Children sustain impacts that cause similar forces to their brain as those sustained by their high school and college peers. Although they tend to have a shorter season, youth football players also sustain a similar number of impacts, on average, per game and practice.

Repetitive subconcussive impacts have been linked to long-term difficulties with brain health, including the neurodegenerative disease Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. The risk seems to increase with a greater number of impacts sustained over a lifetime. Research shows that sustaining more of these repetitive impacts over a week or a season may increase the risk of sustaining a concussion.

You don’t have to hit hard or often in practice to be a successful athlete.

You don’t have to sustain what seems to be a high-force impact to sustain a concussion. There is no known threshold above which the force of an impact is certain to cause a concussion or below which is certain to be safe.

Limited light exercise can help concussion recovery. While we used to recommend staying in a dark room and limiting cognitive and physical exercise, we now know that short bouts of light exercise that does not worsen symptoms can help with recovery. This should be under the supervision of an experienced healthcare provider.

Brain imaging is not helpful for diagnosing a concussion. Clinical brain CTs and MRIs look normal with the vast majority of concussions. While having no findings on a brain scan likely means there is no bleeding in the brain, which is a good thing, it doesn’t mean that the individual doesn’t have a concussion.

Simply passing a computerized test, like the ImPACT test, does not mean that an athlete is ready to return to play. While these tests can provide useful information, they are only one piece of the puzzle, and clinicians should consider the entire clinical exam when making a return to play decision.

Female athletes also have higher concussion rates than males in equivalent sports. For example, female soccer players are at about double the risk of sustaining a concussion compared to male players.

Coaches play a central role in behavior change to better address brain injuries in sports.

Primary sources:

Julie Stamm, Clinical Professor, UW-Madison Kinesiology

Alison Brooks, Associate Professor, UW-Madison Department of Orthopedics, Division of Sports Medicine

In addition to all of the researchers who contributed to Volume 1, BIOS research team members Jose Montoya, Josephine Schaefer, Justin Kakuska, Landry Levinson, Maria Dehnert, Paris Echoles, Peter Miller, Sara Jimenez Soffa, and Wquinton Smith played active roles in assembling this volume.

School of Education

Maria Dehnert Associate Director, BIOS

School of Education

Maria Dehnert Associate Director, BIOS