5 minute read

HOW TO

HOW TO MAKE SNOW

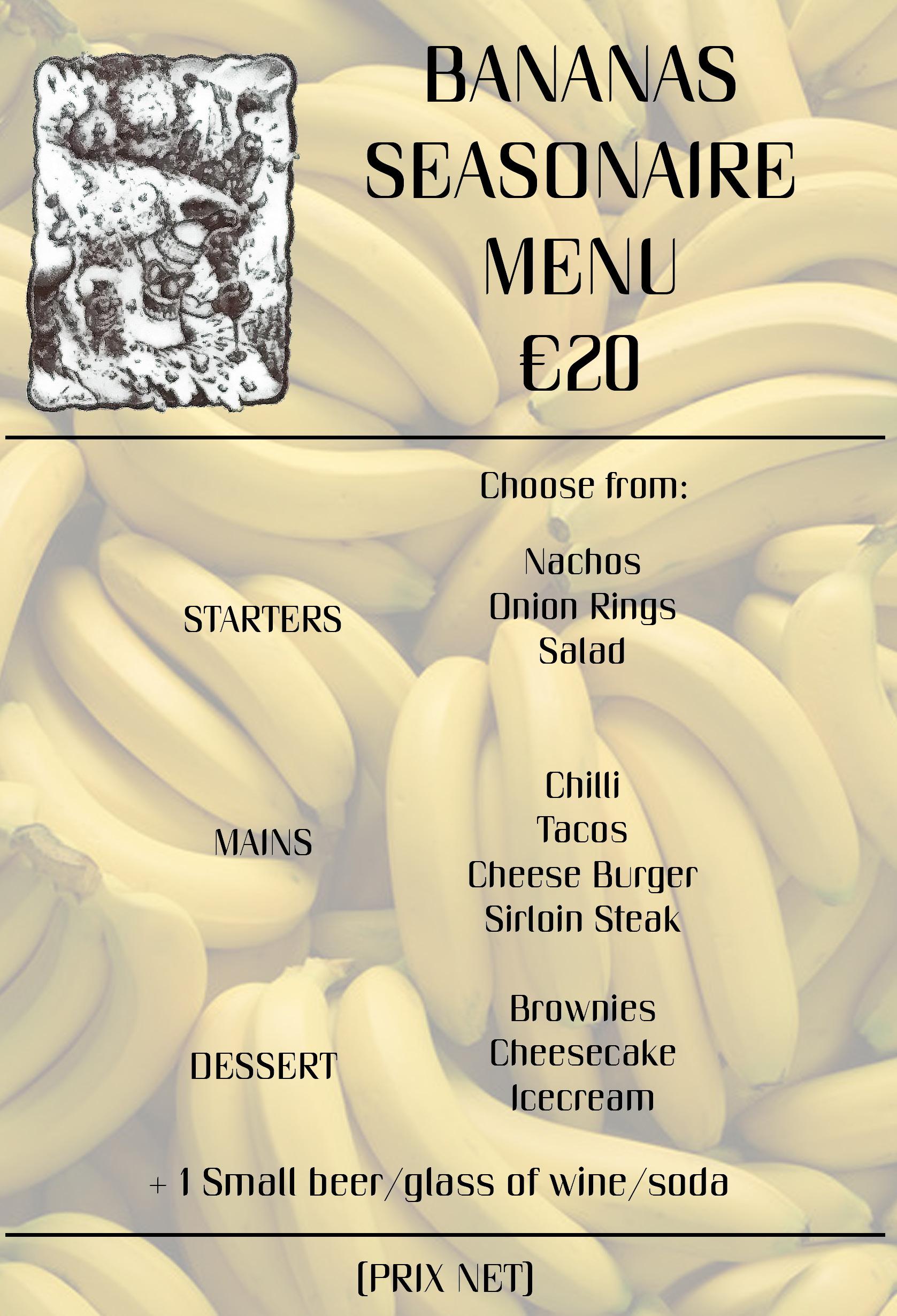

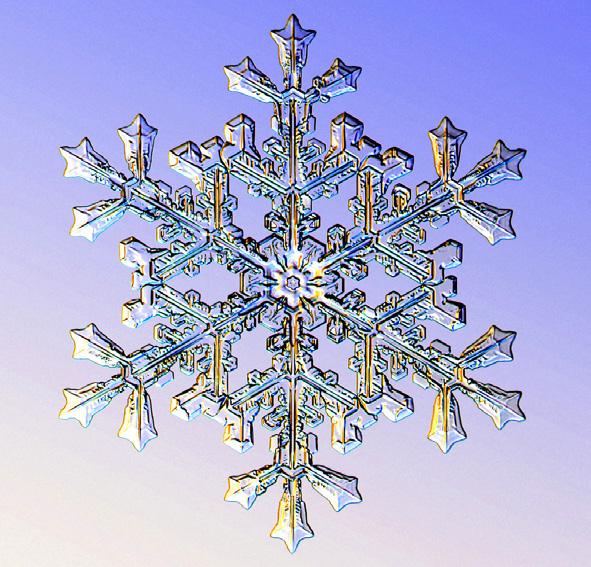

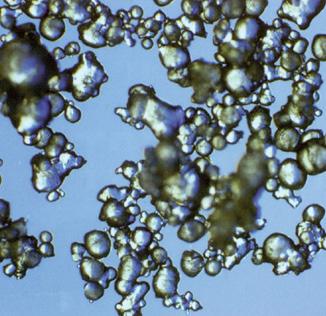

by comparing a microscopic image of a snowflake alongside a molecule of what is produced by the snow cannons. Essentially, the resulting substance is a globule of water encased in a sheath of ice. 19

Advertisement

The Alps have seen an awful lot of crazy weather this season. There are waterfalls where there should be walls of ice and buds on trees that aren’t due to arrive until April. Maybe it’s a fluke season, but more than likely it’s a sign of things to come. Although we might not want to face the facts, rain and long periods of hot sunny weather in January are going to become frequent occurrences as strange weather becomes the new norm. Some resorts have already lost the fight. There’s an incredibly eerie photo series by Tomaso Clavarino of abandoned ski resorts in Europe and the States, which shows stationary ski lifts, still as a photograph, hotels gradually disintegrating into ruins and pistes being engulfed back by nature. Val d’Isère however, is ready. Obviously it already has a major advantage. Standing at 1850m elevation, the town and its ski area are far more likely to experience snow than its lower down counterparts. But as the average snow/rain limit for the season creeps up year on year, the powers that be have another trick up their sleeve that doesn’t require much input from Mother Nature. With a plentiful supply of water, a little air and a negative atmospheric temperature, Val d’Isère Télépheriques is doing what Science Fiction writers predicted back in the 70s: making their own weather. Although you’ll almost certainly have moaned over receiving a face-full of snow from the cannons, it probably hasn’t crossed your mind the amount of work that goes into producing “fake” snow. The word snow here is actually a misnomer as Pierre Mattis explained on a backstage visit to the snow-making facilities. Because what they are making is neither snow nor ice nor water, but a combination of the three. The easiest way of explaining this is Val d’Isère has one of the most extensive snow-making facilities in the world, with the ability to produce artificial snow on a staggering 40% of its 450 kilometres of pistes. This is achieved using 650 snow canons which are all controlled from a computerised central hub. It is this underground lair that we visit and through which the requisite water is pumped from surrounding lakes, rivers and reservoirs. According to Mattis, who is head of the

N E W F I N E F O O D S D E L I C A T E S S E N I N T H E T O U R I S T O F F I C E S Q U A R E . O R D E R O N L I N E A T l m d l m . c o m O R VISIT THE STORE Artificial snow Natural snowflake

Snow Workshop, the amount of water used each season is equivalent to 50cm of the depth of the Lac de Chevril reservoir. There are 9 smaller control centres across the ski area, some at the bottom of the mountains, some, like the one at the bottom of Fontaine Froid, operate further up. The impressive cavern we find ourselves in is buried in to the rocks underneath the Face de Bellevarde. Here, they pump water from the Isère river all the way up at the Pont St Charles beyond Le Fornet. This water is then filtered for impurities and particles, just like a swimming pool. It is vital that the water is as pure as possible to stop ice clogging up the pipes and sensitive nozzles. To form ice crystals, which would be detrimental to the whole operations’ functioning, water molecules require a nucleus on which to condense, a process that cannot happen if there are no foreign particles. 20

The aforementioned nozzles are in fact the only part to come from outside of the facility, being shipped from Canada. Everything else is manufactured in house. And this is what makes Val d’Isère’s artificial snow making facility so special. Initially conceptualised in the 80s, every incremental improvement has been achieved by Val d’Isère Télépherique’s own staff. What they have therefore created is a totally unique system that is minutely controllable, from the area covered, to the density of snow produced. This purportedly means that snow can be tailored made to specification. For example, for the Criterium de la Premier Neige World Cup races at the beginning of the season, more compact snow is produced. This runs faster, an ideal property for professional racing.

cannon can produce 100 cubic meters of snow. But whilst the raw materials to produce such a vast quantity of artificial snow may only be water and air, the energy cost of pumping them both out at pressure is large. Despite huge improvements to the devices’ efficiency in recent years, each still guzzles energy at a rate comparable to running a boiler for a family home for a year You might have noticed the cannons functioning through January and February. This didn’t used to be necessary but is becoming more and more commonplace. The snow-making facilities are in a constant uphill battle against the effects of warming winters; a fight that requires ever more sophisticated equipment at ever increasing quantities. And whilst Val d’Isère, one of the richest resorts in the world, is in a privileged position to be able to invest in this technology, other resorts await with baited breath to see what the future holds, hoping for a miracle or a breakthorugh to stave off the shrinking winters.

Mattis and his team meet with the Pisteurs once a week to establish which runs on the ski area are in need of top ups. This decision making process is now greatly aided by measuring devices on pistebashers that gauge the snow depth directly beneath them. If required, each