“Tell the rabble my name is Cabell.” — James Branch Cabell to his editor, to help people learn how to pronounce his name. Cabell used the word derogatively but we are taking it back. These pages will showcase the writing and illustrations of our rabble— the ordinary students of VCU.

1 EDITOR IN CHIEF Halden Fraley ASSISTANT EDITOR IN CHIEF Noah Wilson ART DIRECTOR Kt Nowak COVER ART Jesse Beck ILLUSTRATORS Jesse Beck Loki FinnAveryReeseBischoffCilleyEckertPlotkin Jessica Soffian EDITORS Ally JesseFinnDavidAveryAwtryEckertSongPlotkinBeck Jessica Soffian Jordan McPherson Julia VivReeseLokiKristenMartinezSturgillBischoffCilleyRathfon Masthead

It’s a different book, but it’s a different time, and we feel this semester’s chapbook reflects that.

Thank you to the City of Richmond and Virginia Commonwealth University for giving us our little corner of space to do our thing in.

2

Putting Rabble together has been a pleasantly rewarding experience. Coming out of an incredibly difficult year for everyone, getting back into the typical Pwatem routine has been a refreshing adjustment.

Things are new, but also familiar at the same time. We wanted Rabble to be something unlike we had ever done before but still maintain the high level of presentation and quality of work that we are known for.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Jessica Clary, Dominique Lee, Owen Martin, and Mark Jeffries at the Student Media Center for your constant advice, support, suggestions, and insight. Thank you to all of the new staff members, who helped make this semester at Pwatem the rewarding and positive experience it is meant to be. Finally, thank you to all of the students who took time to submit their creative work in a strange and busy semester; we literally could not do this without you. Thank you. Thank you.

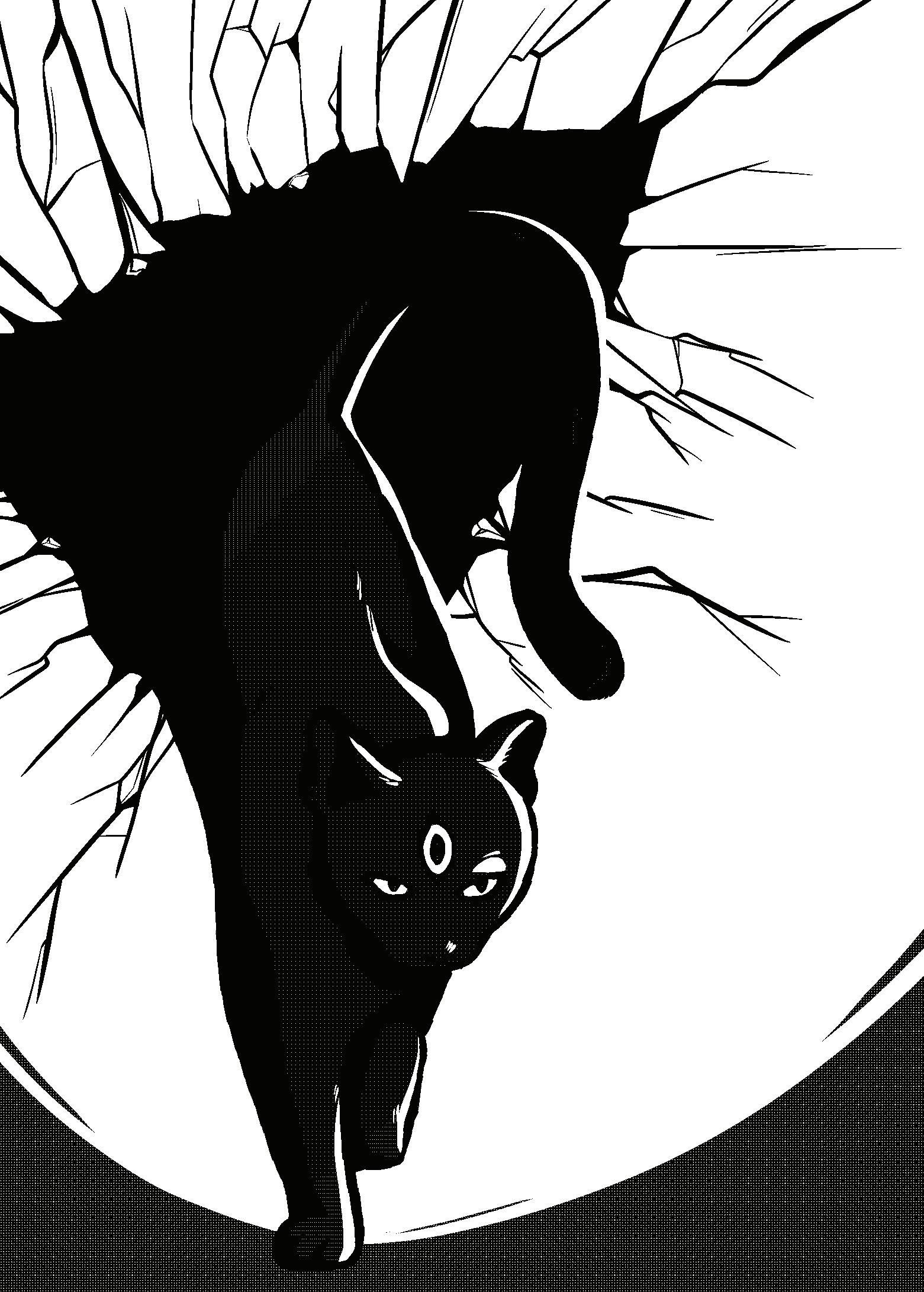

3 Contents The Cloneycavan Man by Nick Siviter ......................................... 5 Illustration by Avery Eckert The Things in the Woods by Jessica Soffian ................................. 11 Illustration by Jessica Soffian Family Man by Aly Awtry .......................................................... 14 Illustration by Loki Bischoff The Nothing by Jesse Beck ........................................................... 17 Illustration by Reese Cilley Maiden, Mother, Crone by Mary-Catherine Kain .......................18 Illustration by Finn Plotkin Familiar with Rejection/Familiar with You by Gabe Carlson....... 21 Illustration by Jesse Beck Rhetorical by Loki Bischoff ........................................................25 Illustration by Avery Eckert PWATEM

years ago while buying a new set of stockings, Finnley had met Cliodhna and she had shone in the light of day. During the nights, in the soupy warmth of peat-fueled fire, the light flickered over her freckles and the smoke clung to their sweat. In the mornings he walked in God’s forest with the healthy stride of a young man, and in the early light found the mausoleum sitting low to the ground.

Twenty-seven years ago Finnley built a small cottage by hand in the new village of Crathie. The village had grown around a rotten little monastery, which still squats atop a wide hillock. Outside the village the sweeping grass is pierced by an eruption of brilliant white stone. The fang of stone is pearly, as if freshly washed, and when the sun shines it’s brilliance becomes blinding. When a storm gathers it bites into the dark, juicy meat of clouds. The trees of the forest block any view of the fang, but Finnley is familiar with the forests, and is rarelyTwenty-fivelost.

Finnley hates the priest who is fucking his wife. He reviles the way his dark habits ride upon his towering and bony shoulders to his wife and describes in sickened detail the sunken hawkish look of the priest which churns his stomach. Finnley loves his wife, who is fucking the priest. He loves her for the skill of her hands, woven into woolen garments that are soft like a goose’s down, and the way those clothes accent the healthy curve of her figure. He often flatters his wife with praise of her skin, which is smooth, pale, and delicate like the contouring feathers of a swan’s belly. Finnley adores the forest which he is now hiking through. He often writes short amateurish verses extolling the forest’s lush greens, its swirling footpaths and bright clearings. He describes the invigoration he feels when the earthy aroma of mossy boulders fills his head and the nectar of the morning dew glosses his feet. Because Finnley loves his wife he is traversing the forest, carrying a ponderous burden, a large shoulder-slung package. And because he loves the forest he traverses it steadily, and because his pace is steady he nears his destination: a forgotten, overgrown mausoleum.

5 Avery Eckert The Clonycavan Man Nick Siviter

Thirteen years ago, in the monastery, a lanky young priest gave a sermon. For the first time, Father Deaglan stood at the pulpit of a chapel, newly built by the hands of the village. Now Finnley is standing before the mausoleum, built by hands long dead. His path through the forest wound in overgrown curves and the uneven ground jostled the package on his shoulders. His aged legs are stiff and his arms are burning, so he sets the package down in the living grass. There is a familiarity to the stonework of the mausoleum. The weight of the cyclopean construction is still apparent to him, twenty-five years of age passed over the granite like a breeze.

6

Finnley takes a moment, and a deep breath. On the air is a faint smell of bog coming from the area past the mausoleum. The earthy smell of peat makes him think of his wife, of cold nights spent in the cottage. On the ground is the package at rest, but in his mind thoughts are racing, he thinks of the priest and his skin crawls. In the vestry a man who isn’t Finnley once caught Father Deaglan and Cliodhna having a go at each other. He thinks of what the priest had done to him, and he thinks of what he has done to the priest. Finnley doesn’t like thinking about it, because he considers himself a pious man. He also considered the priest a pious man. Finnley feels sick when he thinks of his wife, but he does not blame her. He doesn’t like thinking of it, because he considered her a faithful woman. The holy man and his habits broke that faith, and the rules of their own. If Father Deaglan can break the rules Finnley decides so can he. So he braces himself and hoists the oblong package once again. The mausoleum is dark inside. Even feet past the entrance Finnley can barely see his own rough hands, but he can feel the clammy walls around him and slowly makes his way deeper. The flagstones of the floor are cracked by thirsty roots which make his pace unsteady. And from the ceiling vines hang and tickle his weathered face as if they’re trying to tempt him deeper. The light of the day continues to fade. A treacherous set of stairs leads him further down into the earth with slippery and uneven steps. At the bottom the narrow hall opens into

Finnley feels the weight of the package over his shoulder, he thinks about the mausoleum and feels apprehensive, feels scared. He has never entered it, but the entrance is clear of rubble, and at times Finnley feels drawn to it. The village of Crathie is northern, yet the summers are boggy, and on the hottest days his cottage steams him. On days like those, Finnley imagines it must be quite cool and pleasant in the moist bowels of the old structure, in fact he finds its damp entrance quite inviting, attractive even. But he remains repulsed by the remains which lay entombed beneath it.

a larger room where the rank moist air makes Finnley hack and cough hard enough to drop the package. Its weight falls to the ground with a dull thud and a wet smack and he leans against the wall to catch his breath.

Finnley is conflicted. In one thought he respects priests because they are holy men and educate his village on the words of God. They do important moral service and Finnley loves God and all his creations. In another thought he feels betrayed and confused. Finnley weighs the thoughts, like two jagged fragments of flint, they poke into his most sensitive areas. His emotions, his honor, his masculinity, his pride, anger, jealousy, resentment, regret, rustling—the package is wiggling against his foot—shock. Fear. Finnley’s breath is gone again and his chest feels like a boulder is sitting on it. Quickly he runs his hands over the uneven wall and the broken floor until he finds a loosened chunk of granite. Pressing his knee into the midsection of the package to hold it still, he puts the rest of his weight into one unwieldy bludgeon to the top of it. The force takes him to the floor and as he lays across the once again stilled cargo he gasps and wheezes for breath. His face is burning and he still feels lightheaded, regardless he shakily stands and weakly pulls the package out into the room. Further into the room the air only grows sourer and denser. A short distance in is enough for Finnley, in the darkness the package felt as hidden as it would eb beneath heavy earth. Finnley exhales. His body relaxes. But he can’t put his mind to rest, he needs to leave. So he carefully feels his way back retracing his steps to the wall. Which he now allows himself to feel in detail. It feels like a river stone in winter and Finnley finds the contact quickly growing uncomfortable as if the rock is trying to suck the life out of his own body. Finnley’s heart speeds up again, pounding a tight wad into his throat and hurrying him down the corridor and up the stairs. He doesn’t breathe or swallow properly until he emerges into the hot afternoon sun. Then he breathes deeply, relishing the warmth of life and tries to savor the songs of chaffinches and coal tits around, but their song is saccharine and makes his head hurt. The smell of bog is stronger, and more acrid now, has the wind changed? It’ll only get stronger, from here Finnley will need to traverse the bog for the shortest route back to Crathie, where he desperately wants to return.

A cool breeze licks Finnley’s back, sending a shiver through his body and sending him stumbling past the mausoleum. The direct sunlight is brutal compared to the clammy feeling of the mausoleum and Finnley is forced to squint while the heat beats down on him. The path towards the bog from the mausoleum is not one often traveled, and so the reassuring footpaths are absent.

7

But8

Finnley walks, and the smell of peat does not grow. Finlley’s worry grows. There should be a heavy smell of peat encompassing him by now, but the scent is as faint as it had been. He stops and turns around a few times, trying with growing worry to get his bearings in the forest. Finnley is struck hard by a realization: The forest is all trees. He’s surrounded by trees and they all look the same. Why had he never noticed? And how had he ever found his way before. The smell of peat is still as faint as eve and without a footpath there’s no direction for him. Finnley looks to the sun, keeping in mind that the bog lies west of his starting point, only to find that a thick layer of cloud lies across the sky. The diffuse glow provides no clue as to direction. So he chooses a direction, he turns right from where he is and walks. He walks until his feet hurt and until he can’t stand to see a single rotten stump or toadstool poking out of the soil. He stops walking when the sky grows dark. Time has stretched out indeterminably for Finnley, and the possibilities of an approaching storm and an approaching night seem to be equally possible to him. The Idea of traversing the forest at night brings a sour tang to Finnley’s

How long would it take, he wonders to himself? The body he left in the mausoleum, one day, would look like this wouldn’t it? If some poor unfortunate soul stumbled upon the mausoleum in, say, the next month, what would they find? Would it be a soaked bag full of maggots and a clean skeleton? Or a pile of slippery flesh? Or just a malformed corpse, bloated from gaseous rot. Finnley pushes onward, sickened and unable to clear himself of decay.

Finnley knows he can’t go to church anymore, He’s committed a mortal sin and his guilt is too great to bear entry a chapel. He doesn’t think himself to be a hypocrite. There’s too much noise in his head for him to form a coherent plan, but he decides that his life will never be quite the same. Deep in thought, he almost steps directly into the fetid maggot-filled remains of a hare. The stinking writhing meat repulses Finnley and he stumbles backwards onto the peaty soil, scrambling to distance himself from the foul scrambled matter in front of him. His brain is fried, scramble from the shock, and at this distance the smell curdles his stomach and makes him gag. He hunches over the forest floor, drool spilling from his mouth and heat growing in his throat, but he manages to choke it back and pinches his nose, taking care to move around the pile of decay.

Finnley, with his knowledge of the forests is confident. His feet move by their own will, stepping over rocks and roots and ditches, wandering towards the edge of the bog while his mind wanders to its own destinations.

By the time Finnley reaches the edge of the bog His clothes are damp, his feet are sore, his legs are shaking. The smell of peat is dizzying, his feet sink into the wet loam of the bog proper.

9 mouth and makes him swallow uncomfortably and brisken his pace in a new direction. The humid heat is growing and bathing him in slick sweat.

This time the smell of peat grows, it is sour and earthy, but not comforting like it once was. It smells like home, somewhere he can no longer feel comfortable, and heat, which is making him uncomfortable. When night falls the heat will go, but the darkness will bring his walking to a standstill, tripping him with invisible roots and rocks.

The bog was once a comforting place, full of life and movement, the smell of peat would fuel Finnley on his way home. Now the bog is disgusting to Finnley. It’s dead still and the sun is eclipsed by opaque rolls of cloud, making the rough, bristly undergrowth blend into the ground and catch at Finnley’s trousers. The smell reminds him of the decay that peat is born from, the acidic scent burns through his throat and makes him tear up. His vision blurs and smears the bog into a soup of browns and greens. The water sloshes in his ears while the birds mock his struggle from above. His senses melt together. The sucking mud pulls at his shoes and the wet air drips off his red, feverish skin. Tears run down his face and mix with the runnings from his nose. Finnley feels as though he’s liquefying into the putrefaction that he’s trudging through.

A root pulls his feet out from under him and he goes flying into the water of the bog. It’s hot and thick, full of dead vegetation and mud. Beneath him are roots which his feet become hooked in. His arms are weak from carrying the package and he can’t keep his head above water. So he sinks. The water at the bed of the bog is thicker, and much cooler, and it cradles him in loving arms.

You were amusing yourself with composing songs under your breath—rambling ditties with little form or direction to them, but entertaining for your young mind—when your distraction caused you to miss the gnarled root that rose from the snow before you. Your boot caught on it and you tripped and fell facefirst. Now all of you was wet and cold, even your hands in the new mittens your mother had knitted you. You started to cry, but when you looked up to call out to your father he was no longer there. But it was. Your cries stopped mid-breath at the sight of it, just inches away, watching you with horrible eyes like bottomless pools, ageless and deep and aching to swallow you up. Everything was frozen in that moment—even the snowflakes seemed to have stilled in the air—as you stared at it. As it stared at you. Mist formed around its muzzle from the wheezing huff of its breathing, and you knew just looking at it—at the gruesome crown of jagged bone-knives reaching from skull to sky, at the armored feet just the right size to crush your hand into nothing inside your new mittens—this monster could kill you. Easily. And looking into those ancient eyes you knew that it wouldn’t even care.

11

The Thing in the Woods

Jessica Soffian

You were out with your father in the wintertime, shivering in your hand-medown coat and your soaked-through boots. You did not want to be there; you wanted to be at home by the fire, curled up at your mother’s side and lulled to sleep by the gentle sussarus of her voice. But fire needs wood to burn, and according to your father you were a man now, and you wanted to prove it. So, into the woods you went, into the snow and the looming shadows of fir trees. Your lungs ached from the cold of the air and the ax you carried was too heavy for you, but if you stopped moving forward you might lose sight of your father and the dark branches overhead looked almost like claws, so you kept trekking.

Jessica Soffian

You were only eleven the first time you saw the thing in the woods.

Later, your father did not believe you. Your mother smiled gently and patted your head, but you could tell she did not believe you either. She bundled you up in blankets and handed you warm cider and rubbed your frozen toes until the color returned to them. Your father put the new logs on the fire and sighed as he looked at you.

“I guess you’re not quite ready yet,” he said, rubbing his beard. “We’ll try again when you’re older.”

And then, miraculously, by grace of God or luck or some mercy of sheer indifference, it turned and walked away, leaving you shivering in the snowdrifts.

And you knew: you were not quite a man after all.

For years, you feared the woods. You refused to enter them alone, staying only on the outskirts and sneaking anxious glances into the mess of gnarled branches. The memory of it plagued you; every gust of wind was the horrible rasp of its breath, every dark branch moving on the outskirts of your vision was the tip of its bony crown. For years your sleep was restless, and you often woke up sobbing from fear of the dreadful beast you had seen. The specifics of the memory faded over time, leaving only the afterimage of terror, and you found yourself resenting your younger self for being so afraid of what you grew more and more certain was just an ordinary deer or an oddly-shaped tree. Eventually, you started to wonder if you hadn’t just made the whole thing up entirely; if you’d ever actually seen anything at all. Until the second time.

You12 willed yourself to reach for the ax where it had fallen, thinking desperately that perhaps you could at least scare it off, but you found you were paralyzed by sheer terror of the thing before you. You simply could not will yourself to move. You could barely breathe. You were certain, suddenly, that this is where you would die, eleven years old and soaked through and alone.

You were seventeen then, older and more mature. Your voice had recently dropped several octaves and the acne on your chin had started to look more like stubble, and so you thought yourself a man. You went into the woods alone for the first time since the encounter to prove this manhood to yourself and to the world and to anyone who scoffed at you for your childish fears. You walked among the dark branches and looming firs, and the crunch of your boots in the snow and the pulse of your own breath seemed so loud to you, but you told

Alone in the forest, you looked at it: the thing from your nightmares, the thing that you knew in the pit of your stomach could so easily be your death. It wasn’t a deer like you’d hoped—you’d seen deer, and felt chills down your spine at their almost-resemblance—and this wasn’t that. Deer are slender and graceful; the fur on this thing hung off it like moss from trees, and its chest was thick and muscular like the trunk of some great oak. Deer were also docile creatures, skittish and easily frightened, but this thing—whatever it was—stood still and strong and stared you down without a hint of fear in its horrible, horrible eyes. There were stains of rust flaking away on the sharp points of its bone-crown and you knew: this thing had killed. As that thought came to you, the creature lifted its head up towards the grey sky and cried a high, haunting bugle, and the sound of it rose every hair on your body and chilled you down to the bone.

And then you saw it again, there in the glade. Again, time froze, and it looked at you. It loomed before you and it was just as your nightmares recalled it: its eyes were black as depthless pools, just as you remembered, and just as you remembered its crown of bone stretched up and up, branching into sharp points, perfect for goring. Its legs were as you remembered them as well; long and knobby, too spindly to hold such a massive creature, and yet there it was, standing atop the snow which somehow did not give under its weight.

It looked at you, with those horrible eyes, and it finished its battle cry. And it took a step forward. You were not a man, after all. You were the same little boy you’d been before, alone in the woods with this ghastly, wretched thing. So you did the only thing you could do: you turned, and you ran.

13 yourself you were not afraid.

In striking the match head against the side of the box, in relishing in the comforting, grating, whispered purr of the promise of destruction and redemption, and in realizing that to burn it all to the ground and watch until even the smoldering ashes winked out, drained of life and purpose as he had felt all these long years of masquerading as the smiling, go-get-em-sport married father of two who was more than content with his crippling day job breathed one final sigh of relief and bliss and winked out of existence, he — for the first time since his high school sweetheart got down on one knee and opened up Pandora’s box and ruined his entire life, bore the two screeching devils that shredded his independence and sucked away at his youth until he started graying at 25, and dared to whisper those three cursed words so seductively into his ear each night, “I love you” — knew he would feel alive; the possibility of living again sent a thrill through his spine in a way the airy, lotion-smothered touch of his wife and vice-like full-body hugs of his more-monkey-than-human children never could because he realized he loved life more than he loved them, and this — setting fire to the home they slept in so peacefully, so stupidly unaware — was the only way he could ever set himself free and finally, finally be capable of living, and loving, again.

Family Man Ally Awtry

Loki Bischoff

14

The Nothing Jesse Beck

The dirt that Mel had piled back over the grave still looked a bit odd — a little too freshly dug— but it would suffice. Warm autumn wind rattled through her muscles, ricocheted off her bones, through her intestines, and escaped back out into the night air, washing her of sin. She was properly hollow on the inside, like a jack-o’-lantern filled with remnants of hardened candle wax. This is at least what people told her, always likening her to a shell of a human in their morbid torments. She decided to embrace her hollowness out of spite. Mel considered this another good day, but her routine was joined by a pit in her stomach. This is not to say Mel was ever bothered by empty space, but this was not the type of nothingness she had grown accustomed to. She tried to ignore her guts growing heavier as she trekked back home, but it was hard not to feel the extra weight in every footstep. Her thoughts began to amass as she hypothesized a plethora of ways where something went wrong, where something made her insides feel this way— but none of them were right. Today was just another good day. Mel chalked it up to a stomach bug and continued her trudge back.

Oh. Nevermind. The nothing was definitely something.

Time began to muddle together and she was halfway home, at her door, undressing, falling into bed. She managed to suppress the feeling and conk out for six shitty hours of sleep. When she woke, her sheets were soaked with sweat and her clammy body was radiating a feverish heat— this was most definitely not a cold; the pit inside her stomach felt more akin to hunger, eating all her pumpkin flesh and threatening to turn her inside out. Mel dragged her burning limbs into the bathroom and collapsed onto the frosty-cold tiles, her cheek treating the floor like hallowed ground, like an ice pack, like her cemetery plot. She was expecting her normal hollowness to have returned by now, or for the new type of empty to have at least subsided a bit, but she was granted no such reprieve. The vacancy inside her was burgeoning faster than she could process, the emptiness turning into nothing short of a black hole, an accumulation of everything and nothing all at once. She was trembling on the floor of her bathroom, her body completely emaciated, but she felt so. incredibly. full. All the symptoms were there— this was guilt. Her years of executions had finally caught up to her, a propane tank of remorse filling up her hot air balloon stomach. She knew now that she must repent, she must pay for what she did in order to make that pit inside of her become whole again, she must— The nothingness erupted and cascaded out of Mel, tumultuously ripping through her flesh and bubbling down onto the floor in a heap of black sludge.

Reese Cilley

17

18 Maiden, Mother, Crone Mary-Catherine Kain Is this real Is this real, I asked You graced my shore as your destiny instructed You pulled my waves forward and through I ate at the shore until the shore was no more She stood with her feet in my stir waiting until the substance beneath her was mine Is this real Is this real, she asked She raised a hand to shield your light And the answer was in the sky She walked into my depths proud and true And for once, a smile gleamed your face Is this real Is this real No, you reply. This is a promise. Finn Plotkin

I’ve told you multiple times that I love you. Every time I have I’ve meant it, but recently, I’ve stopped knowing how I’ve meant it. I've stopped knowing where that line is; I haven’t even noticed it was blurred until now. I’m selfish. I’ve picked you apart to learn everything about you; your interests, your hobbies, your life. You’ve told me so many things. You’re happy to just have someone to listen. You think it’s been an equal exchange. We trade jabs at each other and you think I’ve told you just as much about me as you’ve told me about yourself. But there’s more to it. You don’t know how ugly I can become, how awful I can be, how mean. You barely know who I am. You’ve only seen me when I’m enamored with you. I’m scared. I’ve thought about telling you more times than I can count. I may be familiar Jesse Beck

Familiar with Rejection/Familiar with You Gabe Carlson I want to say that I’m familiar with rejection.

21

I’m familiar with rejection the same way I’m familiar with you. Familiar with the way your eyes aren’t quite green but aren’t quite yellow. Familiar with your hands and the way they move when you’re telling me about something. Familiar with your sturdying presence when I can barely find my own footing.

I’m familiar with that awful feeling, the one that starts tight in my chest and twists, the one that wets my eyes and parches my throat, makes my jaw clench and shake with the effort of keeping composure, the one that makes my voice waver. That heart-sinking, cold, empty feeling. I’m more than familiar.

I fear that my feelings will drive you away from me, that you can’t see me in that light and things will never be the same. I may be familiar with rejection, but the thought of losing you scares me. I want to think that you’re too good to leave me, that even though you can’t love me the same way, you’d never push me away. I want to believe that you’d let me stay by your side, even if it might kill me slowly within. Even so, I don’t want to risk it.

Your nickname in my phone becomes the inspiration for the stuffed animal on my bed, the same one I slide over to you when you come down to watch movies. The sensation of your hand brushing mine is seared into my memory, and so is the feeling of your fingers through my hair. Your voice has a permanent place in my head; I can hear your texts in my mind when I read them now. You’re too nice, too understanding, too bright; you’re better than me in every sense. I don’t deserve your kindness.

with22 rejection, but it still scares the hell out of me. So, I do something awful. I feel like it’s the only thing I can do.

You’ve wound your way into my existence the same way I’ve wound myself into yours. You’re a staple in my routine.

I remind you of my existence every day. I’ve said enough times that you keep walking right past me on the street, the same day, the same time, so now you’re looking for me in the crowd, searching for my presence the same way I crave yours. I’m a coward.

You think nothing of it. You think it’s just me being nice. You don’t notice it, but that’s the point. You won’t know. You might, eventually. You’re oblivious to the way I’ve wound my existence into yours. My gifts are just material things, but they’ve become staples in your life. You can’t open your door without thinking of me; the pink reminder of mine hanging from your keyring. Your work may be lines of data stored on USBs, but you can’t get to them without going through me; the fabric of the pouch encasing your files further etches my existence into your routine. You may have had your laptop for years now, but now it serves as another reminder; my stickers sit on its case, the same one you want to keep in the future.

23

You may be dense but I can’t hide forever. Not from you. I won’t. I do something awful instead. I make it so you’ll hurt just as much as I will. I’ll further wind my existence into yours, so much so that you couldn’t possibly fill the gaps I would leave behind. Maybe then we would both feel the same way.

Of the first holy conception?

25

To know the difference between good and evil means We know we have a choice between them But a fruit’s taste cannot be forgotten when Its flesh has already been broken by Eve’s mistake

RHETORICAL Loki Bischoff

What do you think the second coming of Christ will be like?

As a perfect repeat?

Do you think it will happen the same way as before When he came down as cells in a human And grew up with us Unlearning innocence while learning the ways of the world

Or do you think it will happen violently, For with experience comes expectations And perhaps He will tear heaven apart To match the shattered pieces that are already here As above, so below The roof of earth may crumble as he Rips away the foundations that gave us the chance To hurt him at all

Can you imagine Our own flesh dissolving In the radiance of the reckoning? Did we deserve it? Avery Eckert

Will there be an echo

With grace turned into footwork instead of forgiveness will we ignore every step of his descension?

Or

Do26 you think the rapture is real? Do you think that the Trinity will unite in Rending our senses and our souls? Do you think he will fall? Not like Lucifer But like a cat with intent To land with purpose, without stumbling To be light on his feet without a single fault To dance on this mortal surface

And

Is

Do we

Maybe we have been given signs for centuries we have missed countless warnings this is what we get for not knowing what to look for. there enough faithful left to be saved? their numbers dwindle, there not still something sacred in our sin of unbelief? believe he will come at all? there really something to wait for? God exist? want it to?

Maybe

Are

Though

Do you

Is

Does

27

Colophon The cover of this publication is printed on Petallics Digital Pure Silver Cover and the interior pages are printed on 70# text, Terra Green. Printed by Allegra, Marketing, Print, Mail. The headlines and credit lines are set in Avenir Next Condensed, regular and bold. The text is set in Adobe Caslon Pro.

"Sinister" was produced by Pwatem Literary and Art Jounal at the Virginia Commonwealth University Student Media Center, 817 W. Broad St., P.O. Box 842010, Richmond, VA 23284-2010.