The New Age of Ag

Virginia companies increase productivity through innovative farming techniques

PERSPECTIVES FROM CEA LEADERS:

Arama Kukutai, Plenty Unlimited Inc.

Alexander Olesen, Babylon Micro-Farms | David Rosenberg, AeroFarms

Virginia companies increase productivity through innovative farming techniques

PERSPECTIVES FROM CEA LEADERS:

Arama Kukutai, Plenty Unlimited Inc.

Alexander Olesen, Babylon Micro-Farms | David Rosenberg, AeroFarms

Controlled environment agriculture (CEA) innovators are working to bypass the challenges of traditional agriculture and bring the food supply as close to the people as possible

Four centuries after the advent of the agriculture industry in Virginia, the Commonwealth is again at the forefront of agricultural innovation

Virginia universities and research institutions are leading the way to improve controlled environment agriculture in the Commonwealth and spur nationwide agricultural development

Aquaculture practitioners in Virginia are helping to create a sustainable food supply while improving the health of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries

Founded by a pair of teenage brothers from Roanoke, the Ice Cream Boat has sold sweet treats on the waters of Smith Mountain Lake since 2000. On days with no wind, customers say they can hear the boat’s music half an hour before they see the boat.

THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION estimates that more than 2 billion people experienced moderate or severe food insecurity in 2021. The United Nations projects the global population to grow to nearly 10 billion by the middle of the 21st century. Taken together, those numbers paint a depressing picture of our collective ability to feed the world’s population moving forward.

A growing industry of agricultural innovators are working on solving that problem. Controlled environment agriculture (CEA) is an umbrella term that encompasses a wide variety of agricultural approaches with the common thread of growing crops indoors. While the technique dates to antiquity, technological advances and research breakthroughs have the industry poised to make a dent in food insecurity — with Virginia at the forefront.

The world’s largest indoor vertical farming campus is under construction just outside Richmond in Chesterfield County, courtesy of California-based CEA company Plenty Unlimited Inc. That record is currently held by another Virginia farm — David Rosenberg, CEO of New Jersey-based AeroFarms, called his company’s Danville facility “the largest of its kind in the world” when it officially began operations in 2022. Those operations share the common thread of being located in population centers, away from the huge tracts of land

required for traditional outdoor farms. Their locations speak to the potential for CEA to transform food production by growing produce closer to consumers, enhancing freshness, nutrition, and most importantly, availability.

This issue of Virginia Economic Review takes a deep dive into the past, present, and potential of the CEA industry, along with highlights from more traditional agricultural operations in Virginia. Inside, we discuss the history and future of CEA, the companies pushing the industry forward in Virginia, and the research ecosystem that underpins the industry’s growth. We also go in depth on the Commonwealth’s thriving aquaculture and peanut industries and discuss the present and future of the CEA industry with CEOs from three leading companies: AeroFarms’ Rosenberg, Arama Kukutai of Plenty, and Alexander Olesen of Babylon Micro-Farms.

Best regards,

Jason El Koubi President and CEO, Virginia Economic Development Partnership

Jason El Koubi President and CEO, Virginia Economic Development Partnership

VIRGINIA’S AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION STATE RANKS

#3 #4 #6 #6 #6 #8 #9

Tobacco

Seafood Landings

Apples

Pumpkins

Turkeys

Peanuts

Broilers

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture

National Agricultural Statistics Service, Economic Research Service

2021

Source:

Source: Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services

SanMar® Corporation, a leading supplier of wholesale accessories and apparel, will invest at least $50 million to establish a distribution operation in the East Coast Commerce Center in Hanover County in the Greater Richmond region. The facility will be the company’s largest operation and the flagship center for its East Coast operations. Virginia successfully competed with North Carolina for the project, which will create up to 1,000 new jobs at full capacity. The company is eligible to receive benefits from the Port of Virginia Economic and Infrastructure Development Grant Program.

Based in Issaquah, Wash., and family owned and operated since its founding in 1972, SanMar is the largest supplier of wholesale imprintable clothing and accessories in the United States. The company operates eight additional distribution centers across the country. SanMar distributes apparel from more than 30 retail, private, and mill brands, including Nike, Eddie Bauer, The North Face, Carhartt, Champion, and Tommy Bahama.

JEREMY LOTT CEO, SanMar Corporation

Whenever we look at a facility, of course we’re looking at logistics and the labor market, but we’re also really looking at the community and the culture, and the people who will be working in the building. As we met and talked with people in the area, we knew this could be a great fit for us and for our future growth.

Central Virginia

AgroSpheres

Jobs: 50 New Jobs

CapEx: $25M

Locality: Albemarle County

Greater Richmond

Church & Dwight Co., Inc.

Jobs: 53 New Jobs

CapEx: $27M

Locality: Chesterfield County

Richmond National Group

Jobs: 100 New Jobs

CapEx: $350K

Locality: Henrico County

SanMar® Corporation

Jobs: Up to 1,000 New Jobs

CapEx: $50M

Locality: Hanover County

Weidmüller Group

Jobs: 100 New Jobs

CapEx: $16.4M

Locality: Chesterfield County

Hampton Roads

Advanced Integrated Technologies

Jobs: 76 New Jobs

CapEx: $500K

Locality: City of Norfolk

BAUER

COMPRESSORS, INC.

Jobs: 47 New Jobs

CapEx: $7.4M

Locality: City of Norfolk

Magazine Jukebox Inc.

Jobs: 20 New Jobs

CapEx: $1M

Locality: City of Norfolk

I81-I77 Crossroads

Wilderness Mountain Water Company™

Jobs: 55 New Jobs

Locality: Bland County

Lynchburg Region

Delta Star, Inc.

Jobs: 149 New Jobs

CapEx: $30.2M

Locality: City of Lynchburg

Northern Virginia Dev Technology Group

Jobs: 90 New Jobs

CapEx: $366K

Locality: Fairfax County

Zollner Elektronik AG

Jobs: 20 New Jobs

CapEx: $4M

Locality: Loudoun County

Roanoke Region

Altec Industries

Jobs: 150 New Jobs

CapEx: $1.4M

Locality: Botetourt County

Layman Distributing

Jobs: 42 New Jobs

CapEx: $6.8M

Locality: City of Salem

STS Group AG

Jobs: 119 New Jobs

CapEx: $32M

Locality: City of Salem

Shenandoah Valley

Bowman Andros Products

CapEx: $40M

Locality: Shenandoah County

Southern Virginia

Zollner Elektronik AG

Jobs: 80 New Jobs

CapEx: $14M

Locality: City of Danville

In addition to providing drinking water for the city of Roanoke, Carvins Cove Natural Reserve in Roanoke County is protected by the largest conservation easement in Virginia’s history, offering ample recreation opportunities on land and water.

ust outside the city of Danville, Virginia, sits a farm unlike any of its neighbors. Tucked into the tree line, it stands 50 feet high, sleek, and solid white, standing out from the long, thin rows of tilled fields that surround it.

Growth at AeroFarms happens entirely within this massive white warehouse. Inside, 48 growing towers glow with LED bulbs and reach as high as the five-story ceiling. Layer upon layer of vegetables mature under the targeted light spectrum. Their bare roots dangle, spritzed with precise amounts of water and nutrients for days or weeks, until they slide along a conveyor to be automatically harvested, packaged, and loaded onto a truck headed for Walmart, Amazon, or Whole Foods customers.

There are no seasons, no droughts, nor even any soil at AeroFarms. The company uses vertical farming — a combination

of aeroponics and LED lighting — to control every input each plant needs. AeroFarms is just one of many innovators using technology to bypass the challenges of traditional agriculture, part of a new generation of growers working to secure the food supply and bring it as close to the people as possible.

Controlled environment agriculture (CEA) dates at least as far back as the early years of the Roman Empire, when Emperor Tiberius demanded a more consistent supply of cucumbers. Moveable beds were placed outside in favorable weather and brought indoors in poor weather. Greenhouses have been used for millennia to nurture vulnerable plants. Even hoop houses, which use a simple plastic covering to protect plants and extend the growing season, are considered a type of CEA.

But in the last 20 years, indoor growing has taken on a new level of sophistication. Two camps have emerged: high-tech greenhouses and vertical farms.

Greenhouses have evolved well beyond capturing sunlight and shielding against weather. New high-tech greenhouses use supplemental light when necessary, harvest using robotics, and collect enormous amounts of data at the plant level. Gotham Greens, a high-tech greenhouse grower with 13 urban locations, uses machine learning to monitor crop health.

Other companies, like Bowery Farms in New Jersey, don’t use sunlight at all. Like AeroFarms, they’re vertical farms using all LED light. They also don’t use soil. Bowery employs hydroponics, where plant roots rest in water, while at AeroFarms, the plants’ roots are misted with water and nutrients in a process known as aeroponics.

Regardless of method, CEA is poised to expand. According to Market.us research, the CEA market — from hoop houses to vertical farms — was valued at $74.4 billion in 2021 and is projected to more than triple by 2032. According to the report, areas like automation, lighting, and analytics hold the most opportunities for growth.

Success in the produce industry largely comes down to a grower’s ability to predict the future — an area where indoor growers have the upper hand. Traditional growers must anticipate loss due to inclement weather, pests, and food wasted in the field. The amount a grower plants doesn’t always translate perfectly to yield, and harvest timing can vary by weeks, depending on the weather.

Indoor growers, on the other hand, can predict the harvest window down to the day. And their percent yield is higher because they have more control over light and nutrients. At AeroFarms, leafy greens

that traditionally take 35 to 40 days to harvest can be grown in 12 to 14 days.

These companies can produce more food in a shorter window by circumventing the variability of nature — and they can do so with fewer inputs. Precise delivery of water, nutrients, and fertilizer means less is wasted.

“The UN thinks that by 2050, there will be nearly 10 billion people to feed. That’s 25% more food with fewer resources with more volatility,” said Kate Seawell, chief commercial officer at Bowery. Indoor methods offer an opportunity to meet the needs of this moment, she added.

Indoor growers also enjoy the ability to bring production closer to consumers. In 2020, 77% of the U.S.’s fresh fruit and vegetables came from Mexico. Mexican produce can take up to two weeks to arrive at grocers, while CEA farms, with smaller physical footprints, can be located closer to major population centers, reducing the time from harvest to shelf.

Because of their proximity to grocers and consumers, indoor growers can also focus on a virtue of vegetables that’s often deemphasized: taste.

Many vegetable varieties have been prioritized for their ability to withstand the long journey from harvest to shelf. Tomatoes and cucumbers are bred so they won’t wither or rot in the weeks required for harvest and travel to far-flung destinations. Growers then run into an unfortunate reality: If you’re breeding for hardiness, you’re breeding against taste.

Indoor growers able to locate in or near major cities and foodways aren’t so confined. With less distance to cover, these companies can afford to expand production to other crops, including varieties that are more delicate and others bred for optimal taste.

Indoor growing seems to offer the ideal scenario — higher yields of better-tasting foods, using fewer resources. But one factor stands in the way of faster expansion: cost.

Between land needs, building costs, extensive energy needs, and the use of cutting-edge technology, indoor growing is capital-intensive. One supplier quoted its vertical farming technology at $1,000 per square meter. That’s on top of research and development as companies work to develop their own proprietary growing methods for different plant varieties.

After a large initial round of CEA investment, focus has shifted to getting companies to scale to produce a profit. Lux Research analysts note that many

indoor growers “still [have] a long road ahead to matching the costs of produce grown outdoors as well as the crop diversity.” To get there, energy efficiency and a knowledgeable workforce are crucial, and growers are investing in programs and partnerships aimed at those goals (see page 48).

Climate change and geopolitical unrest have provided massive tailwinds for the CEA sector, Seawell explained. Moving forward, there’s room for a variety of innovations and indoor growing models. She said, ultimately, everyone is moving toward the same end, “working to crack the code on how to fortify and strengthen the food system.”

KATE SEAWELL Commercial Officer, Bowery FarmsChief

The UN thinks that by 2050, there will be nearly 10 billion people to feed. That’s 25% more food with fewer resources with more volatility.

Beanstalk Farms operates out of a former data center building in Fairfax County. The company uses soil and renewable energy in growing its crops.

Beanstalk Farms operates out of a former data center building in Fairfax County. The company uses soil and renewable energy in growing its crops.

AGRICULTURE IS VIRGINIA’S OLDEST, largest private industry. The farming of cash crops in the Commonwealth dates back to the early 17th century, when tobacco farming helped John Rolfe and his fellow settlers establish a stable colony at Jamestown and ultimately make Virginia the largest and richest of the initial 13 colonies.

Four centuries later, Virginia is again at the forefront of agricultural innovation. The Commonwealth has become a hotbed for operations capitalizing on the latest in food production technology. Virginia is drawing investment from companies producing fresh, sustainable, locally grown foods utilizing the latest, most advanced agricultural technology available, such as hydroponic, aeroponic, vertical, and other indoor systems, collectively known as controlled environment agriculture (CEA).

In addition to their investments in Virginia’s communities, CEA companies are working to advance sustainable production techniques by curbing energy consumption and resource use while providing fresher produce for communities both within the Commonwealth and beyond.

The latest major CEA operator to choose Virginia is California-based Plenty Unlimited Inc., currently in the process of building what will be the world’s largest indoor farming campus at Meadowville Technology Park in Chesterfield County, just outside Richmond. Plenty CEO Arama Kukutai said the facility will “raise the bar on what indoor vertical farming can deliver.”

The Virginia advantage for CEA companies starts with a favorable location within a two-day drive of three-quarters of the U.S. population — far closer than traditional American farming hotspots in the Midwest and California’s Central Valley. Along with that location, Virginia offers a business climate regularly ranked as one of the nation’s best, buoyed by strong

economic incentives and a tech-savvy talent pool graduating from the Commonwealth’s top-notch colleges and universities each year. That combination was enough to lure Plenty to Virginia, along with AeroFarms, another industry leader that had previously built a record-setting vertical farm in the Commonwealth.

Last year, New Jersey-based AeroFarms was listed among Fortune’s “Change the World” list of companies that have had a positive social impact through their core business activities. After an extensive site search along the East Coast, AeroFarms selected Cane Creek Industrial Park, jointly owned by the city of Danville and Pittsylvania County, to locate its largest, most sophisticated farm to date. Last year, the company announced an expansion to the facility that received a

ARAMA KUKUTAI CEO, Plenty Unlimited Inc.

The scale and sophistication of what we’re building here in Virginia will make it possible to economically grow a variety of produce with superior quality and flavor.

second round of support from Virginia’s Agriculture & Forestry Initiatives Development Fund (AFID), a 10-year-old program aimed at spurring growth in the Commonwealth’s agriculture and forestry sectors (see sidebar on page 21).

Virginia’s business friendliness played a major role in landing the facility. As AeroFarms Chief Marketing Officer Marc Oshima said, “The state and Southern Virginia’s commitment to our sector is also a contributing factor as we’re able to attract the talent and resources needed to operate our facilities...One of the main challenges with a capitalintensive business like vertical farming is the associated taxes assessed on tangible personal property. The abatements offered by the local jurisdiction provided the assurance that we were not going

to be taxed out of having a competitive project in Virginia.”

Virginia’s talent and research infrastructure is also attractive to CEA companies. AeroFarms CEO David Rosenberg cited the nearby Institute for Advanced Learning and Research (IALR) as a potential collaborator in the company’s efforts to use technology to solve supply chain issues in agriculture. In 2020, shortly after the announcement of the AeroFarms facility, IALR announced a partnership with Virginia Tech’s School of Plant and Environmental Sciences and Virginia Seafood Agricultural Research and Extension Center to launch the Controlled Environment Agriculture Innovation Center on its campus. (For more on CEA research in Virginia, see page 30.)

Virginia’s higher education system also played a key role in establishing Beanstalk Farms in Fairfax County — Chief Technology Officer Jack Ross is a Northern Virginia native who graduated from the University of Virginia (UVA). The Commonwealth’s economic infrastructure and the university-based, tech-forward talent pool played a major role in the company’s founding.

The company has a connection to another high-tech Virginia industry. Its Fairfax farm is housed in a former data center building in the town of Herndon. And like Plenty and AeroFarms, Beanstalk received an AFID grant to defray facilities costs.

“I knew that we would be able to tap into the state’s talented workforce, world-class universities, and supportive business environment to build something truly special,” Ross said.

Beanstalk carved out its niche in vertical soil-based production technology, rather than the soil-less aeroponic systems AeroFarms is known for. Research coming from UVA and Virginia’s other top universities helped the company fine-tune its technology.

“Virginia has a unique set of resources,” Ross said. “The support from research universities like the University of Virginia and Virginia Tech has helped us improve our soil-based growing method and enabled us to have the highest-quality heirloom produce.”

Like Beanstalk, Babylon Micro-Farms was founded by UVA graduates, and the company fine-tuned its products and techniques at the i.Lab incubator housed in the university’s Darden School of Business. Now based in Richmond, Babylon uses hydroponic techniques to grow nutritious produce, managed through cloud technology. The company’s miniature vertical hydroponic farms have been installed in hospitals, hotels, and senior communities to provide fresh produce for residents and restaurants. It’s a twist on one of the main selling points for vertical farming — vertical facilities can help bring fresh produce to a wide array of locations without the large physical footprint of a traditional farm.

In 2022, MSC Cruises installed a Babylon garden on its ship, the MSC World Europa, to provide herbs, greens, and garnishes for the Chef’s Garden Kitchen, a collaboration with Michelin-starred chef Niklas Ekstedt, billed as the world’s first at-sea hydroponic micro-farm. Babylon CEO Alexander Olesen said, “On-site micro-farms are going to be an important part of the supply chain for fresh ingredients, and it’s exciting to push the boundaries of local food production with this world-first installation on the high seas.”

Long before some of these companies were founded, one group set the pace for Virginia’s CEA industry: Soli Organic, formerly Shenandoah Growers. Under its former name, Soli was a classic outdoor agricultural field production business. Then, keeping up with industry trends, the company expanded into indoor farming and CEA.

Soli CEO Matthew Ryan cited Virginia’s location as a draw in establishing facilities in the Commonwealth, citing the ability to provide “efficient service to our growing customer base throughout the Mid-Atlantic region and beyond.”

Soli is the country’s leading grower of fresh organic culinary herbs. If you’ve seen potted herb plants for sale in your local grocery store, there’s a good chance they’re Soli products. The company’s 2021 rebranding reflects that market space and the techniques the company uses. “Soli” is derived from the Latin word for “soil,” which most indoor growers don’t use, relying instead on hydroponic methods. Soli’s use of soil allows for the shipment of living herbs to retailers, but its innovations go beyond growing techniques.

Soli runs its own refrigerated transportation service that enables the company to ship living plants across the

country. The company’s trucks enable herbs that require different temperatures to be shipped on the same truck, enhancing shelf life.

CEA practitioners are drawn to Virginia’s advantageous location, top-notch business climate and incentives, and the talent, research, and resources coming out of the Commonwealth’s colleges and universities. Virginia is poised to help companies like Plenty, AeroFarms, Beanstalk, Babylon Micro-Farms, and Soli Organics make vital advancements in feeding the United States and the world.

AeroFarms and Beanstalk aren’t the only Virginia CEA companies to take advantage of the Agriculture and Forestry Industries Development Fund (AFID). Plenty Unlimited Inc., Soli Organics (as Shenandoah Growers), Bright Farms in Culpeper County, Fresh Impact Farms in Arlington County, and Greenswell Growers in Goochland County (see page 48) are among the many CEA companies that have received money from the fund.

AFID was created in 2012 to help companies in the agriculture and forestry industries that were too small to qualify for traditional state incentives. As a former Virginia Secretary of Agriculture and Forestry told Cardinal News, “I figured if we could incentivize big, we should certainly figure out a way to incentivize small.”

AFID grants are apportioned to local governments for projects that fulfill the following conditions:

◾ The project is creating new capital investment and jobs in Virginia

◾ The project is a facility that produces “value-added agricultural or forestal products”

◾ At least 30% of the agricultural or forestry products to which the facility is adding value will be grown within Virginia

◾ The grant may not exceed $500,000 unless the project is deemed to have statewide or regional importance

Grants may be used for a variety of purposes, including extension or capacity development for public and private utilities, including high-speed or broadband internet access, road, rail, or other transportation access costs beyond the funding capability of existing programs, site acquisition, construction and activities required to prepare a site for construction, and training. AFID awards require a 100% local match.

The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, which administers AFID, has given out 128 grants since 2012. The projects helped by those grants have generated more than 4,000 new jobs and more than $1.4 billion in capital investment.

Soli Organic grows its plants in soil to allow for the shipping of living herbs to retailers. Like other CEA companies, Soli monitors temperatures, light levels, humidity, and water exposure to create the optimal conditions for healthy plants.

Soli Organic grows its plants in soil to allow for the shipping of living herbs to retailers. Like other CEA companies, Soli monitors temperatures, light levels, humidity, and water exposure to create the optimal conditions for healthy plants.

Controlled environment agriculture (CEA) describes a variety of systems that use technology to provide optimal growing conditions for crops, from simple hoop houses and traditional greenhouses to fully indoor vertical farms. The most advanced CEA operations are fully automated systems that deliver the exact environmental conditions required by specific plants, including the optimum temperature, humidity, and light levels. CEA operations can grow large amounts of produce while using significantly less water and land and eliminating the need for certain pesticides and fertilizers. VEDP spoke with CEOs from major CEA companies on how technological advancements will affect the future of the agriculture industry in Virginia and beyond.

Babylon Micro-Farms was founded in 2017 by University of Virginia (UVA) engineering students with the goal of empowering anyone to grow their own fresh, sustainable food. Initially, the founders wanted to design a low-cost micro-farm to provide nutritious produce for food-insecure refugees in the Middle East. Babylon’s modular, vertical micro-farms allow users to grow vegetables two to three times faster, using 90% less water than outdoor farming, powered by a proprietary remote management platform. The company’s clients include IKEA, LinkedIn, MSC Cruises, and Neiman Marcus. Alexander Olesen is a co-founder of Babylon Micro-Farms and has served as CEO since the company’s founding.

San Francisco-based Plenty Unlimited Inc. operates a technology platform that can grow fresh produce almost anywhere in the world year-round with peak-season quality and up to 350 times more yield per acre than conventional farms. Plenty’s proprietary approach is designed to preserve the world’s natural resources, make fresh produce available to all communities, and create resilience in our food systems against weather, pests, and climate impacts. Arama Kukutai was an early investor in Plenty, has been on the company’s Board of Directors since 2016, and was named CEO in 2022.

Since 2004, AeroFarms has been a leader in indoor vertical farming, using proprietary aeroponics to optimize growing while using up to 95% less water and zero pesticides. The company utilizes genetics, engineering, food safety, data science, and nutrition to understand plant biology in new ways. Its commercial farms are optimized for year-round production, no matter the season or weather, and grow more than 550 different varieties of leafy greens, berries, tomatoes, and more. David Rosenberg is a co-founder and CEO of AeroFarms.

We see next-generation crops like berries as the newest advancement in the CEA space. Berries are a beloved fruit across the globe, yet they are continuously cited as a pesticide-heavy crop within traditional field farming, landing on the Environmental Working Group’s Dirty Dozen list year after year. AeroFarms has grown numerous varieties of berries in our research and development farms, and we are scaling innovative commercial indoor vertical farming solutions to provide consumers with safe, pesticide-free berries at an excellent value proposition in the coming years.

In recent years, the approach was “bigger is better” with indoor farming. That is beginning to change. We are going to see a more balanced approach as businesses weigh factors like crop selection, output, price point, and sustainability/marketing goals. Greenhouses, large vertical farms, container farms, rooftop farms, and smaller on-site business-to-business farms like we’re building will play their respective parts.

The market is mature enough now that substantial growth is likely in the indoor-grown category. We’re seeing a desire for fresh products at an affordable price that are available all year round and indoor agriculture is well positioned to deliver that. We are insulated from the pressures that are impacting supply from the field, like increasingly challenging weather, the reliance on shipping product from one coast to the other, and the challenges over water and water access. By growing regionally, indoor farms can also address consumer and retailer demand to shorten supply chains to reduce food waste and improve food quality.

I think, also, what we are seeing is the beginning of more sophistication of diversity in the sector. Today, the biggest suppliers are all essentially using existing greenhouse technology, and they’re mainly growing tomatoes and leafy greens. There’s a whole portfolio of crops that consumers want that we can grow indoors to provide an increasingly resilient supply — and one that’s also differentiated in terms of quality, because the closer you are to the consumer, the fresher the product is, which is a proxy for nutrition and taste.

Our plant scientists monitor millions of data points every harvest. They are constantly reviewing, testing, and improving our growing system using predictive analytics to create a superior, consistent result. We utilize and have developed cutting-edge approaches to machine vision, machine learning, and IoT integration, bringing agriculture into the future at a rapid pace. Our digital controls include an integrated algorithm for every stage of growth as well as our proprietary agSTACK software, allowing for a smart, fully connected farm. We are also in a multi-year partnership with Nokia Bell Labs to expand our joint capabilities in innovative networking, autonomous systems, and integrated machine vision and machine learning technologies to identify and track plant interactions at the most advanced levels.

We have quite a different strategy compared to greenhouses and other vertical farming companies in that we started with a completely novel architecture. By designing an entirely new way to grow food, we believe we can improve the quality of product, the unit economics, and the overall experience for the consumer. Part of how we do that consistently is through access to real-time data in the farm. Because our plants are growing on an accelerated timeline compared to the field or even a greenhouse, change happens much quicker. Staying connected to what’s happening in our growing facility in real time means if we see plant health suffering for some reason, we can make an immediate intervention to adjust the plants’ environment.

We use internal research and real-time analytics of sensor data from our fleet of micro-farms to make decisions about the right growth recipe for each device. Our remotely managed BabylonIQ system uses an array of sensors to collect numerous data points to determine a farm’s health and safety at any given moment. Analysis of this data allows us to monitor and dose the proper amount of nutrients in a farm to create perfect growing conditions. We are currently teaching our cameras and software to determine plant health and, over time, create a dynamic feedback loop.

The average age of a farmer, according to the USDA, is nearly 60 years old. CEA, and especially vertical farming, attracts a much younger, often well-educated workforce. The style of farming in vertical farming is much less labor-intensive because there is a much higher degree of automation. Because CEA is still relatively new, there is a great deal of research and innovation. In the past, we were not able to control the weather, but in CEA, we can.

Beyond using data and data insight to create the perfect growing environment for our plants, we also use it for research and development. We have the ability to monitor very granular experiments, because we’re collecting large amounts of data as well as pictures of every plant through their growth cycle. That data accumulates and helps us make decisions on cultivars, the right nutrition, temperature, humidity, and so on. And because our plants grow so quickly, we can run many years’ worth of field experiments in a single year, accelerating our learning curve.

From a raw numbers perspective, we obviously have less staff than the number of people it would take to cover the hundreds and hundreds of field acres, equivalent to what we produce in a single city block. Beyond those efficiencies, we’re creating a new model of agricultural employment. We’re always looking for ways to take dangerous or back-breaking jobs out of the process, like using robots to harvest. We’re creating year-round, full-time jobs with benefits in an industry known for hourly, seasonal labor. And we’re creating the opportunity for our team to build careers — we have a sizable workforce need in areas like engineering, logistics, maintenance, and growing. These are knowledge-based jobs where it’s possible to come in at entry level and have an advancement path.

ALEXANDER OLESEN CEO, Babylon Micro-Farms

Encouraging investment in CEA automation, data sharing, and access to affordable electricity is critical to scaling the industry.

What workforce concerns are most pressing to CEA companies? How can states, regions, and localities work to address those issues?

There is more competition than ever for an entry-level workforce, and we need to be able to position our work as year-round opportunities to have a positive impact on our food systems. Support at the local level can be a resource with recruiting and basic job skill readiness. Longer-term, CEA companies are partnering with local governments and universities to create a pathway for students who want to go into careers in CEA.

To make sure that there are sufficient workers with the right technical and horticultural skills to help grow the industry. We are fortunate in that we have Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, UVA, and many more top schools.

CEA allows us to grow closer to consumers and disintermediate the supply chain by operating as both a grower and packer. Due to this vertical integration, AeroFarms can have a product with a longer shelf life that can travel greater distances and make an impact on the number of communities served.

The obvious benefit is being able to build the facilities closer to the consumer. In Virginia, we’ll have a one-day shipping radius that touches about 100 million consumers. I can’t speak for others, but for Plenty, we’re typically looking at sites where our produce can ship in no more than a day. That means the product arrives at the distribution center, then the store, in a fresher condition, with long shelf life. That also means, we hope, the consumer will have a better eating experience and there will be less waste.

Because the product is grown in trays, vertical farming allows for a high degree of automation in both washing and packaging. Hydroponically grown produce such as lettuce is sometimes packaged with the roots to preserve freshness. Building farms closer to the point of sale or the point of consumption reduces the need for long supply chains and refrigerated trucks.

Alongside that, we’re spending less road miles, less fuel, and less CO2 shipping product around. In Richmond, we can ship up and down the Eastern Seaboard 365 days a year with the same quality of product.

How do CEA techniques affect the scope and techniques of shipping produce to different states and regions?

ARAMA KUKUTAI CEO, Plenty Unlimited Inc.

Capital goes where it’s needed, but it stays and grows where it’s appreciated. We’ve seen a high degree of appreciation for what we’re trying to do.

What other opportunities exist for CEA companies aside from growing produce themselves?

Could proprietary technology be licensed to other companies to create an additional revenue stream?

I see opportunities whereby CEA is combined with education and hospitality — farms in food halls or greenhouse/ restaurant combinations like De Kas in Amsterdam. The remote management system that Babylon has developed certainly has applications in many other industries — for example, we can now predict when a pump is going to fail by a tell in our graphs, which means we can send a replacement to our customer before the pump stops working. That type of predictive information would be helpful in supporting many organizations and different kinds of on-site vertical farming solutions.

It depends on the business model of the company in question. Some of the opportunity is adding more production because there’s so much growth left ahead. This is still the early days for the industry. There are opportunities to explore growing other types of products — Plenty farms are highly controlled environments, so we’re doing some exploratory work around that.

Others who have more of a technology offering can look at licensing models. We certainly are, since we own the key parts of our technology stack. I also think there are opportunities to explore adjacent industry efficiencies. We’re really interested in renewable packaging and new types of renewable energy that can lower the carbon footprint of our production and make it more sustainable.

When you compare the CEA industry in the United States with other countries, where do we stand? What can we learn from foreign leaders in the field?

The United States is home to many of the world’s leading CEA companies that are pioneering new technologies and paving the way in this growing industry. Other countries around the world are increasingly interested in the expanding sector, especially those in desert and arid climates that are looking for food solutions that use less water and less arable land. AeroFarms recently opened the world’s largest indoor vertical farm dedicated to R&D in Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The UAE imports approximately 90% of its country’s food supply, and it has looked to companies like AeroFarms to create new, sustainable food solutions to grow delicious, nutrient-rich food within the country.

The Netherlands is the undisputed leader in the field of CEA, and they are very much involved in developing the industry in the United States and many other countries. Encouraging Dutch companies with this expertise to open subsidiaries in Virginia is a very effective way to speed up development in the United States. Encouraging investment in CEA automation, data sharing, and access to affordable electricity are critical to scaling the industry.

The Middle East is making large investments in CEA, as is Singapore. The countries that are investing most heavily in CEA are those that currently have to import almost all of their vegetables because of climate and the lack of arable land and fresh water.

With controlled environment agriculture, there are more options for site selection. The amount of sun depending on proximity to the equator is still a factor for high-tech greenhouses, but for indoor vertical farms like AeroFarms, we can place a farm anywhere, regardless of the season or weather conditions outside. At AeroFarms, our LED lights mimic the sun and our aeroponic technology acts as the soil and nutrients. We can grow our produce in any indoor space around the globe.

CEA should be considered as a toolkit that needs to be adapted to the specific market and climate of each region. CEA operations are typically located close to the customer base to minimize transportation. Urban farms are a good example of this. Babylon’s micro-farms engage people, educate, and promote sustainability and eating healthy, and therefore are very much front-facing and located where the food is consumed in lobbies, dining rooms, and cafeterias.

For one, Virginia is a hub for supply chain routes that connect the Mid-Atlantic region to the rest of the U.S. AeroFarms’s farm in Danville, Virginia, is capable of serving more than 50 million people within a day’s drive. Additionally, AeroFarms chose Virginia for our newest state-of-the-art vertical farm because of the support from local, regional, and state officials who want to see the CEA industry flourish in Virginia.

We chose Virginia after an extensive search of locations in part because it is in a great location to serve many, many consumers up and down the Eastern Seaboard. There are a lot of distribution centers in the area, including major retailers like our partners at Walmart, which we supply today on the West Coast and plan to supply on the East Coast.

Virginia has a long traditional farming heritage. The central location on the East Coast, close to large metropolitan areas, the pro-business government, and the number of CEA companies already present set Virginia up to become the leading CEA state.

Virginia also has some excellent infrastructure and a very business-friendly government. Capital goes where it’s needed, but it stays and grows where it’s appreciated. We’ve seen a high degree of appreciation for what we’re trying to do, not just commercially, but as an innovation sector. The support infrastructure is there, the educational institutions are there, the policy environment is there. Our decision to come to Virginia has already proven out and we can’t wait to get our first strawberry farm open there.

Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Gloucester County

Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Gloucester County

Consider the strawberry. Its skin, slightly glossy in a deep crimson hue, warmed by gentle light. A burst of sweet juice when first pierced by the teeth, giving way to tart flavors and a subtly gritty texture from dozens of tiny seeds. A survivor of climate conditions — drought or flood, cold snaps or intolerable heatwaves — and attacks by animals and insects. A warrior against fungal infestations and bacterial infections.

Now imagine that strawberry was not grown in soil. Instead, it grew from seed to fruit in a long, gutter-shaped vessel in water that has been engineered with all the nutrients, airflow, and light it could need to become an exemplar of its breed. Instead of a field, it was grown in a facility as sterile as a neurosurgery operating room. Instead of overalls and flannels, these farm workers wear sanitary coveralls, hair nets, and shoe coverings.

This strawberry is a product of controlled environment agriculture (CEA), the fastest-growing sector of agriculture in Virginia.

Most CEA facilities are indoor, completely enclosed buildings. Many rely on artificial light and vertical growing structures. Some are hybrid models, closer to greenhouses with glass roofs for natural light. In the case of aquaculture, shellfish are bred and raised to the larva stage in hatcheries that resemble laboratories, but the outcropping of shellfish to maturity happens in natural environments.

CEA tends to be more expensive than traditional agriculture, but has numerous benefits and advantages that make it worth the cost. It currently accounts for up to 2% of food production in Virginia.

Dr. Bill Walton, Acuff Professor of Marine Science at the College of William & Mary’s Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), described CEA as “mimicking what nature does, but limiting what nature throws at you.” This means reducing natural disease, increasing crop yields, creating healthier

food systems, growing food year-round in any part of the country, and growing crops as close to local markets as possible — an extension of the local food movement.

It also means augmenting the nutrient compounds introduced to growing practices for food that has greater health benefits for human consumption, shorter seed-to-harvest time, longer shelf life — because crops don’t require as much washing and can be immediately picked at a predictable harvest time — and ideal flavors.

“You can set certain conditions to ensure you can get the prime sweetness conditions every single time. It’s almost like cheating,” said Dr. Scott Lowman, vice president of applied research at the Institute for Advanced Learning and Research (IALR) in Danville and co-director of the Controlled Environment Agriculture Innovation Center (CEAIC), a partnership between IALR and Virginia Tech. Beyond taste, his team is researching ways to grow crops with higher levels of essential nutrients and biological compounds that can reduce disease or lessen the effects of preexisting conditions. Key demonstration crops at the CEAIC include strawberries, blackberries, lettuce, herbs, and hemp.

With the CEA industry still in relative infancy, extensive research is required and will be ongoing. Stakeholders like VIMS, IALR, Virginia Tech, and others are leading the way on CEA research in Virginia. The research conducted on CEA is shared widely with individual growers and harvesters throughout the state and across the country to spur on CEA development in America’s vast agricultural industry.

Water is a critical element to all agriculture, but is especially important for controlled environment agriculture. Since most crop production currently occurs in a hydroponic or aquaponic setting with water as the primary growing medium, being able to recirculate water is critical to the success of CEA.

Recirculating water creates a closed-loop system that reuses water existing in the CEA facility. This water has already been filtered to remove outside contaminants and engineered to include vital nutrients and biological compounds for a better crop.

Water recirculation is a core component of aquaponics, which is the combined production of vegetal and animal crops. Plants and animals in CEA share similar technologies and needs. Recirculating water helps maintain beneficial bacterial levels in the water, accelerating how plants and marine life absorb and introduce these elements in a symbiotic relationship.

Water reuse and recirculation is also critical to one of the main goals of CEA: growing food as near to local markets as possible. In drier locales, recirculation means less water is wasted than in traditional agriculture, and the growing process requires substantially less water overall. More food can be produced regardless of natural weather phenomena, closer to the intended market.

CEA researchers are looking for other ways to increase efficiency. Agriculture is a large consumer of energy, but an overall goal of CEA is to produce more food with less waste. Virginia researchers are investigating ways to incorporate

You can set certain conditions to ensure you can get the prime sweetness conditions every single time. It’s almost like cheating.

DR. SCOTT LOWMAN Co-Director, Controlled Environment Agriculture Innovation Center

alternative fuel sources, renewable energy, and sustainable building practices to improve CEA infrastructure.

Moving agriculture indoors is a solution to disease issues, but researchers continue to focus on the impact of disease and how to mitigate its spread. Hydroponics is a large focus area in disease research because growing items in water reduces the introduction of soil-borne disease, but issues like wilt still affect hydroponic crops. Biocontrols are introduced to the water source, which can reduce or eliminate the need for pesticides and other biochemicals that serve as a “cure” rather than prevention. Michael Schwarz, associate director of the CEAIC and director of the Virginia Seafood Agricultural Research and Extension Center (VSAREC) in Hampton, cited disease control as a key

advantage for CEA operations and stated that proper use of CEA techniques can help create zero-pesticide crops.

Water recirculation research parlays into disease management because filtering water allows for the removal of disease and infection. This research is useful to other industries because cleaning solutions introduced into CEA practices can be utilized elsewhere, Lowman said. Disease management research in CEA has the potential to shed new light on epidemiology in a post-COVID world.

Fulfilling that potential requires intensive crop monitoring, and CEAIC researchers are working internally and with corporate partners like Canon Virginia, Inc., to develop technology that allows for constant photo imaging of crops to monitor to-the-moment growth patterns and problems or other issues. In the future, these imaging systems will work in concert

There is a lot of sharing research information by talking over the back of a pickup truck.DR. BILL WALTON Acuff Professor of Marine Science, Virginia Institute of Marine Science

with water, air, light, and disease sensors to quickly find and rectify problems with a growing condition or an individual plant or animal, whether by robotic removal of the plant in question or by adjusting the amount of light, a certain nutrient, or airflow patterns, either manually or through digital automation.

That kind of granular light adjustment is available to CEA operations through use of LED lights. While some CEA facilities operate as a glass-roofed greenhouse, most rely on a hybrid model that incorporates LED grow lights to generate photosynthesis in plants. LED lights compensate for a lack of natural light in short-day seasons (like winter), allowing for year-round growth and production.

IALR’s LED light quality research focuses on how crops respond to changes in light and how increased availability of light (and different spectrums of light and radiation) can affect the growing process.

IALR is also home to the Plant Endophyte Research Center, which studies the use of symbiotic endophytes — beneficial microorganisms that live between living cells — to enhance crop yield through stronger root systems. Potential benefits of

advancements in endophyte use include chemical fertilizer reduction and soil quality improvements.

While technological advancements are the main focus of entities in Virginia’s CEA research ecosystem, workforce development is another major priority. As Schwarz put it, “We are behind the 8-ball and there is a labor shortage.”

CEA is a highly technical field requiring workers with advanced knowledge of technology, robotics, and microbiology. Virginia’s research centers are developing programs — some starting as early as middle school — to foster a skilled CEA workforce, while entities as large and established as the U.S. Department of Agriculture offer funding to train workers on CEA-specific topics.

All this research is shared in a variety of ways. Virginia’s cooperative extension centers (including VSAREC) are a partnership between Virginia Tech and Virginia State University. Researchers from both universities, along with others in Virginia’s CEA industry, regularly publish

findings in peer-reviewed research studies, allowing Virginia insights to reach all corners of the agriculture industry.

IALR and CEAIC also partner with the organizers of Indoor Ag-Con, one of the largest indoor farming events in the country, to host CEA Summit East, an in-person conference that brings growers, educators, scientists, engineers, technology specialists, and other industry personnel together to discuss new findings and the latest ideas in CEA research. “Everyone is doing something a little different,” said Lowman, and CEA Summit East is a chance to share and discuss information for the benefit of the industry.

At VIMS, Walton said that while his team engages in published studies and conferences, the best way to get information directly to the growers is to be a presence at their farm or growing facility and share insights face to face.

“When we pull up, they know who we are,” he said. “There is a lot of sharing research information by talking over the back of a pickup truck.”

Rappahannock Oyster Co., Middlesex County

Rappahannock Oyster Co., Middlesex County

AQUACULTURE COMPANIES SEEK PROFITABILITY THROUGH

In 2001, when cousins Ryan and Travis Croxton took over their family’s 100-year-old oyster bed leases on Virginia’s Middle Peninsula, the Commonwealth’s oyster industry was on life support. The traditional harvest method of dredging the floors of bays and estuaries had left waterways oxygen-poor and clogged with silt, and the region’s native oyster, the Eastern oyster, seemed bound for the endangered species list. Contemporary estimates placed the species at barely 1% of its historic population.

The Croxton family business was in a similar state. The family’s leases were about to expire, and previous generations, wanting to encourage their descendants to enter less labor-intensive industries, had sold off property and equipment to prepare to wind the business down. The leases were all that was left.

That lack of resources would prove crucial to the company and the Chesapeake Bay alike. Without the fleet of boats that helped the business boom in the previous century, Ryan and Travis were forced to investigate alternative

harvesting techniques, eventually settling on “off bottom aquaculture,” in which the oysters are kept in cages that float on the water’s surface, away from the silty, nutrient-deprived seafloor.

“We were able to forego traditional methods of harvesting, which were very detrimental to the health and condition of the Chesapeake Bay,” Travis Croxton said. “We instead focused on helping to introduce aquaculture to the region — not only as a sustainable, but also a restorative approach” in which the company’s oyster spawns help the species re-establish itself in the wild. Today, his company, Rappahannock Oyster Co., ships to top restaurants nationwide and operates five restaurants across the country.

The Croxtons are continuing to fine-tune their methods — their cages now sit on legs near the seafloor, minimizing visual disruption at the surface while helping to re-establish better growing conditions. Meanwhile, the rebounding oyster population continues to perform its crucial role of filtering excess nitrogen and phosphorus from the bay’s waters.

In its most basic form, aquaculture is simply raising fish or shellfish in captivity for harvest. An aquaculturist builds a tank, holding pond, or lagoon to house the fish or shellfish, either temporarily or for the animal’s entire life cycle, before harvesting the fish for consumption or sale.

Aquaculture systems range from simple freshwater ponds and saltwater lagoons to carefully monitored manmade tanks. Systems for shellfish make use of cages or pens positioned in lagoons or bays. This arrangement takes advantage of tidal movement and natural aeration while shielding shellfish from predators.

Many aquaculture operations rely on specialized hatcheries and/or nurseries to ensure healthy conditions for the full life cycle. Freshwater systems feature ponds or tanks of varying size and depth. The most carefully regulated freshwater systems are housed indoors under computerized temperature, light, and water quality conditions.

Indoor aquaculture allows practitioners to optimize for fish health while enabling

While some aquaculture practitioners grow their specimens in controlled environments, Cherrystone Aqua-Farms in Northampton County grows its clams and oysters in the same open water as their wild counterparts.

10,000+ miles

of coastline in Virginia

40 million

oysters harvested in 2018 in Virginia

We recognize that any shellfish grower out there has seen more of their environment than I have…They can bring their expertise and we can bring our science to work together.

TRAVIS CROXTON Co-Owner, Rappahannock Oyster Co.

TRAVIS CROXTON Co-Owner, Rappahannock Oyster Co.

production in inland localities far away from any natural bodies of water. Blue Ridge Aquaculture (BRA) in Henry County, a four-plus-hour drive from the Atlantic Ocean, has become the world’s largest producer of tilapia, shipping up to 20,000 pounds of live fish each day, raised without the use of antibiotics or hormones.

BRA uses recirculating aquaculture systems to create a carefully monitored habitat optimized for the health of the fish. The company continually filters waste from its water while re-oxygenating it, preventing problems with one fish from spreading to the rest of the crop.

“You can’t optimize the system when you have known sick animals in your system,” said BRA President Martin Gardner. “It’s much more efficient to keep disease out than to treat for it.”

Virginia was the fourth-largest state for aquaculture sales in 2018, the date of

the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s most recent Census of Aquaculture. The Commonwealth’s aquaculture farms totaled a combined $112 million in sales that year, trailing only Mississippi, Washington, and Louisiana.

Virginia’s advantages to seafood producers start with the Chesapeake Bay, which makes up the majority of the Commonwealth’s more than 10,000 miles of coastline. The bay and its tributaries provide a habitat that produced more than 40 million oysters in 2018. That’s a fivefold increase since 2005, making Virginia the leading state for mollusk sales in 2018, with its $94.3 million in sales nearly tripling second-place California.

In addition to oysters, that figure includes clams, which the Commonwealth leads the country in producing each year, with more than 200 million individual hard clams harvested from Virginia waters annually.

Like Rappahannock, Cherrystone Aqua-Farms, in Northampton County

on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, has been in the same family for several generations. The company made a proactive switch to aquaculture about 40 years ago and now counts 150 full-time employees who help sell oysters and clams through retail and wholesale outlets, including a burgeoning e-commerce business that started during the COVID-19 pandemic to make up for the loss of sales to restaurants.

“With restaurants closing, we had little to no market for oysters,” said Tim Rapine, Cherrystone’s managing director of operations. “That was a huge impact on growers we worked with, as well as the employees we needed to pay. It took a couple of months to work through that. Then grocery stores took on a role they hadn’t filled before, such as clams and oysters. Groceries became a big sales point for us and turned into some of the best sales we’ve seen during the company’s history.”

Also like Rappahannock, Cherrystone benefits from a thriving Virginia aquaculture research sector (see page 30). The College of William & Mary’s Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) in Gloucester County works closely with aquaculture producers to help solve problems, boost production, and streamline operations, while Virginia Tech and Virginia State University run the new Virginia Seafood Agricultural Research and Extension Center in the city of Hampton. Together, Virginia’s universities provide research opportunities and guidance to stakeholders at every level of the seafood supply chain that are appropriate to each entity’s resources and techniques.

“We recognize that any shellfish grower out there has seen more of their environment than I have,” said Dr. Bill Walton, Acuff Professor of Marine Science and shellfish aquaculture program coordinator at VIMS. “Then we try to solve problems from there. Let’s say it’s an established grower coming to us with, ‘Why are my shellfish dying?’ or ‘What is this I’m seeing?’ They can bring

There’s tremendous opportunity in working with our natural resources if done in a restorative and sustainable manner. It’s also incumbent on farmers like us to ensure we are treating the waterways with respect and working in concert with the localities and neighbors to share the natural resources that our rivers and bay provide.

their expertise and we can bring our science to work together.”

VIMS also serves as a testing ground for new technology and methods. Recently, that has included potential advancements in the use of radio-frequency identification and artificial intelligence in inventory management. As Walton put it, “We’re not advocating that we have a better way, but rather exploring things and putting things out there as opportunities that they can take advantage of.”

According to Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) data, aquaculture production passed wild fish catch in 2013 and has widened its margin since then. The United States produced $1.5 billion worth of aquaculture seafood in 2018 in a market currently dominated by Asian producers.

Saltwater and estuary species represent the top sales volumes, but freshwater fish are increasingly being raised via aquaculture as well at companies like Blue Ridge Aquaculture, with top species including catfish, striped bass, trout, and perch in addition to tilapia. Some systems raise fish in captivity for eventual release in the wild, while other systems keep the fish contained in water pens for their entire life cycle.

These production numbers are happening alongside a global increase in seafood consumption. According to FAO data, global fish consumption has more than doubled since the 1960s, with the increase largely supported by aquaculture operations, where production has increased more than 50-fold during the same period. Aquaculture companies are looking to the future to see how the industry can continue to aid in the Chesapeake Bay’s recovery while providing economic opportunity for Virginians.

“Most oyster farms are in economically depressed rural areas. We are no exception to that with our three farm locations,” Travis Croxton said. “Our

goal is to work with local and state governments to really emphasize the opportunities that aquaculture and leveraging our waterways can provide to our communities.

“There’s tremendous opportunity in working with our natural resources if done in a restorative and sustainable manner. It’s also incumbent on farmers

like us to ensure we are treating the waterways with respect and working in concert with the localities and neighbors to share the natural resources that our rivers and bay provide…The economic engine that Virginia has in its waterways is virtually untapped. It can power a lot of opportunity for a lot of our citizens.”

The

first known commercial peanut crop in the United States was harvested in Sussex County. Today, the water tower in the town of Wakefield pays tribute to one of the area’s leading industries.

first known commercial peanut crop in the United States was harvested in Sussex County. Today, the water tower in the town of Wakefield pays tribute to one of the area’s leading industries.

Any discussion about Virginia peanuts needs to start with a clarification between Virginia peanuts and Virginia Peanuts. The lowercase former refers to peanuts grown in the Commonwealth; the capitalized latter is one of four peanut cultivars grown in the United States. If you’ve ever cracked a peanut out of a shell at a baseball game, that was a Virginia Peanut. Virginia Peanuts can be peanuts from Virginia, of course, but they’re also grown across the Southeast.

While Virginia Peanuts make up just 15% of total American peanut production, they’re known across the industry as the gold standard for size and quality. The vast majority of American-grown peanuts are the cultivar known as Runner Peanuts, often used in peanut butter and confections.

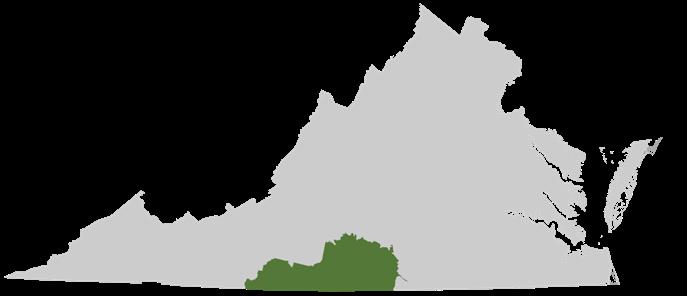

Virginia ranks eighth in the country for peanut production, with Commonwealth growers planting approximately 28,000 acres of peanuts in 2022, according to the Virginia Peanut Growers Association (VPGA). Nearly all of them are Virginia Peanuts, with some Runner Peanuts mixed in, and the vast majority are grown in a group of nine cities and counties in the southeastern part of the Commonwealth. Virginia is the northernmost peanut-growing state and among the most efficient, producing 4,500 pounds of nuts per acre in 2022, trailing only Arkansas, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture data.

Virginia Peanuts are often sold in premium packaging, at premium prices, in gift baskets and tins. Hubbard Peanut Company’s Hubs peanuts are one of the most prominent premium varieties, and founder Dot Hubbard pioneered the production of gourmet peanuts in the 1950s through a process that started with blanching the nuts in water before cooking.

It didn’t take long for business to take off. Word of the delicious nuts began to spread and a mail-order business took shape, with the nuts sold in gift shops, clubs, hotels, and restaurants across the country. Food writers as prominent as legendary critic Craig Claiborne of The New York Times took notice, and an industry was born.

In 2020, Hubbard expanded into a 58,000-sq.-ft. manufacturing, shipping, and retail space in the city of Franklin with about 70 permanent employees — not including the seasonal workers the company takes on to fulfill the Christmas rush, when its products are in high demand as gifts.

“Virginia is to peanuts what the Napa Valley is to wine,” Hubbard Co-Owner Marshall Rabil said. “Our nuts may not be as sexy as wine, but we’re part of every party.”

The Mr. Peanut statue in Suffolk pays tribute to the iconic Planters mascot, created by a local child. Planters has operated its Suffolk facility since 1913.Native to South America, peanuts were grown only on a small scale until the mid-19 th century. That’s when Dr. Matthew Harris cultivated the country’s first known commercial peanut crop in Sussex County, near the town of Waverly. The area’s warm climate and sandy, loamy soil proved to be an ideal environment for the plant, and Virginia quickly took the lead in American peanut production.

The Commonwealth’s enduring contributions to the industry didn’t end there. In 1902, Southampton County farmer Benjamin Hicks received a patent for the first gas-powered peanut picker, which revolutionized production by stemming and cleaning the nuts.

The biggest, most familiar name in American peanuts entered the Virginia peanut industry not long after that. In 1913, Planters Nut and Chocolate Company moved to the city of Suffolk, known as “The Peanut Capital of the World.” The company’s iconic Mr. Peanut mascot was created by a local child, Antonio Gentile, and a statue of the mascot has stood in downtown Suffolk since 1991.

Now owned by Hormel Foods, Planters employs approximately 400 people at its Suffolk facility. “When I interview people for jobs, they often tell me they want to work here because their grandfather or their grandmother worked here,” said Cara Dunfee, human relations manager at Hormel in Suffolk. The plant produces 126 nut-based products, ranging from trail mix to deluxe cashews.

The Virginia Diner began its peanut journey a few years later. The company started out in a railroad car in the Sussex County town of Wakefield, just a few miles down U.S. 460 from Waverly. At the time, founder D’Earcy Davis was focused on fried chicken, hot biscuits, and vegetable soup.

Before long, customers became so enamored with the free peanut snacks Davis handed out to guests that the company began to switch gears. In the late 1940s, it started to pack and sell peanuts from the restaurant. That ultimately evolved into Virginia Diner, the peanut manufacturer (and restaurant, although it operates out of a traditional building instead of a rail car). Instead of

Virginia is to peanuts what the Napa Valley is to wine. Our nuts may not be as sexy as wine, but we’re part of every party.

MARSHALL RABIL Co-Owner, Hubbard Peanut Company

dry roasting, Virginia Diner peanuts are blister roasted, or soaked in warm water before roasting, giving the finished product a unique texture and crunch.

Andrew Whisler, chief operating officer of Virginia Diner, says the company does most of its sales via mail order — like Hubs, mostly between October and December as holiday gifts to customers around the world. Around mid-October, when the company’s holiday sales reach their peak, even Whisler will join the front lines and help pack peanut orders.

“Come holiday time, no one has a job title around here,” he said. “We all share in the work together, wearing multiple hats to ensure shipments get out on time and every customer leaves completely satisfied with their experience.”

Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood has been a center for Black commerce and entertainment since the early 20th century, earning the nickname “Black Wall Street” for its concentration of Black-owned businesses, including the historic Hippodrome Theater.

Growers is using innovative partnerships to develop a future workforce at its high-tech facility in

One current

Greenswell

Goochland County.

intern is Wilson Venable (right), a student at Douglas Freeman High School in Henrico County, shown here with Greenswell Sales & Marketing Manager Caroline Ogilvie (left) and President Carl Gupton.

Greenswell

Goochland County.

intern is Wilson Venable (right), a student at Douglas Freeman High School in Henrico County, shown here with Greenswell Sales & Marketing Manager Caroline Ogilvie (left) and President Carl Gupton.

Labor shortages have long been a challenge in agricultural operations, spurring innovative new ways of operating. Today’s farms rely as much on GPS-guided technology and artificial intelligence-driven automation as they do on manual labor. However, these changes have created their own hurdles by demanding new skills of today’s agricultural workforce.

For colleges, universities, and high schools across Virginia, that means expanding agricultural programs to encompass all aspects of the science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) curriculum.

“There’s a common misconception that agriculture is just working with animals, driving tractors, and playing in the dirt. But it’s not. It’s all that plus biology and chemistry and, even more now, it’s technology,” said Mallory White, Ph.D., assistant professor of biology and program head of agriculture in the School of STEM at Virginia Western Community College in Roanoke.

To prepare the Virginia workforce for this shift, institutions like Virginia Western are expanding education for agricultural technicians to include pathways into agriculture through mechatronics. Skillsets in robotics, automations, and computer coding are increasingly in demand across Virginia’s more than 41,500 farms.

It’s finding employees that have a passion for both coding and “playing in the dirt” that can prove difficult, as Carl Gupton, president of Greenswell Growers, has found. His company launched its controlled environment agriculture (CEA) operation in Goochland County near Richmond in 2020 with the goal of producing 28 times more leafy greens per acre than a traditional operation despite minimal human contact. Gupton says that the cultivation process is essentially hands-free from seed to fridge due to the use of automation.

At the time of its launch, this hydroponic greenhouse was only the eighth of its kind in the United States, meaning its niche technology requires specific technical expertise to maintain. “As a closed-environment growing system, if one thing breaks down, the whole system slows down,” Gupton says.

Knowing the small company needed a workforce with a unique range of skills, Greenswell worked with Goochland County Economic Development and reached out to local schools before its operations were up and running. It has since sourced interns from Virginia Tech and the local campus of J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College.

The company also formed partnerships with career and training programs in the school systems in Goochland County and neighboring Henrico County. By connecting with youth who didn’t fit the traditional post-high school path, the company aimed to mold a workforce with the crossfunctional skills needed to support a modern CEA operation.

The framework Greenswell provided the schools for its internship needs includes a diverse range of skill sets: marketing, operations and logistics, mechatronics, and culinary arts. Gupton has found interns tend to lean more heavily on either mechanical or science skills, but Greenswell provides training to mitigate expertise gaps. Ultimately, he says, it’s less about what the students know than their desire to learn. “We can train them to turn a wrench. We’re looking for a willingness to do multiple tasks,” he said.

As agricultural programs open the door to more technically minded students, it may in fact become easier to find that willingness.

“I had a student last semester who is a programmer,” Mallory White said. “He needed a science elective and [my class] was on his list. He’s actually gone on to take more agricultural classes this semester.”

“Everybody is starting to hear about the changes in agriculture,” added Amy White, dean of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics at Virginia Western.

Tech support, robotics, and data analysis are just some examples of the skills needed to run a modern CEA facility. To successfully develop an industry heavily laden with technology, engineers, plant scientists, and computer scientists have to be trained to work together.

“I think for the technologically inclined, it piques their interest. So, we show them that there is a career pathway, it’s growing, and we want them to grow in the Commonwealth.”

Educational institutions are hardly alone in this endeavor. “We understand how important finding and keeping workers are to businesses,” said Sara Worley, director of economic development for Goochland County. The department works with the public school system to match curriculum to support industry needs.

“In addition, Goochland County operates an Agricultural Center where the County and Economic Development office hosts local agricultural events that help get the next generation of workers more excited about a potential career in agriculture,” Worley said. “Goochland has a deep

agricultural history, and we think it is important to honor those roots by providing support to our ag businesses.”

Amy White agrees, adding that the approach Virginia Western takes supports industry innovators like Greenswell as well as more traditional family-owned farms. “At the last Census of Agriculture, we had about 3,000 working farms in our service area, so there is a need,” she said. “If students wanted to go straight to a four-year program to pursue any aspect of agriculture, that path was pretty clear. But there was not a path for students who wanted to get some training and go back to work on their farms.”

Virginia Western is betting that its two-year Associate of Science degrees can help cover those knowledge gaps. By allowing students

the flexibility to gain broad science and mechanical skill sets, these programs are bringing even smaller farms up to speed on emerging technological innovation.

These types of classes are becoming more common. As Worley notes, Reynolds Community College also offers an Associate in Applied Science in Horticulture Technology and a certificate in Sustainable Agriculture at its Goochland campus. In addition to its industry partners, Virginia Tech has partnered with the Institute for Advanced Learning and Research (IALR) to research and develop educational programming to further advance CEA operations like Greenswell’s.

“Modern farming, especially indoors, requires a workforce with training similar to high-tech manufacturing,” said Dr. Scott Lowman, vice president of applied research at IALR and co-director of the organization’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Innovation Center (see page 30).

He added, “Tech support, robotics, and data analysis are just some examples of the skills needed to run a modern CEA facility. To successfully develop an industry heavily laden with technology, engineers, plant scientists, and computer scientists have to be trained to work together. This is happening at Virginia Tech and other universities across the state.”

Encouraged by investments in K-12 and higher education, today’s youth are discovering that there are more paths than they may have imagined to a successful future in agriculture. And these investments are paying off for students and farmers.

“The kids have been impressive,” Gupton said, speaking of the youngest interns that have helped his company every semester for the last two years. He admits that the company still uses spreadsheets developed by one high school student. He adds, “I’d hire every single one of these kids that have done this internship program in a heartbeat.”

When The Turman Group began focusing on exporting nearly 20 years ago, company executives had goals and anxieties that are likely familiar to businesses that have taken similar steps. Leadership at the Galax-based wood products company saw the potential for new markets, increased sales, and improved resiliency with domestic economic issues. They also saw the potential downsides that come with opening up to new clients.

“In the wood business, 95% of the cargo that’s put in a container at the port is shipped unsecured. There’s nothing backing it other than the history between you and a particular customer, and maybe a deposit that’s been paid,” said Wil Brush, leader of export sales at The Turman Group. “How do you navigate those waters? That’s the biggest challenge any wood exporter faces. If you want to export in a container, there’s risk

Those risks led The Turman Group to work with VEDP when the company hired Brush to oversee exports in 2006 with an eye on the Chinese market. One of his first major projects after starting at the company was a VEDP trade mission