10 minute read

The Swiss Cheese Strategy By copying the aviation industry, you can make sure your marketing strategy will fly

By copying the aviation industry, you can make sure your marketing strategy will fly

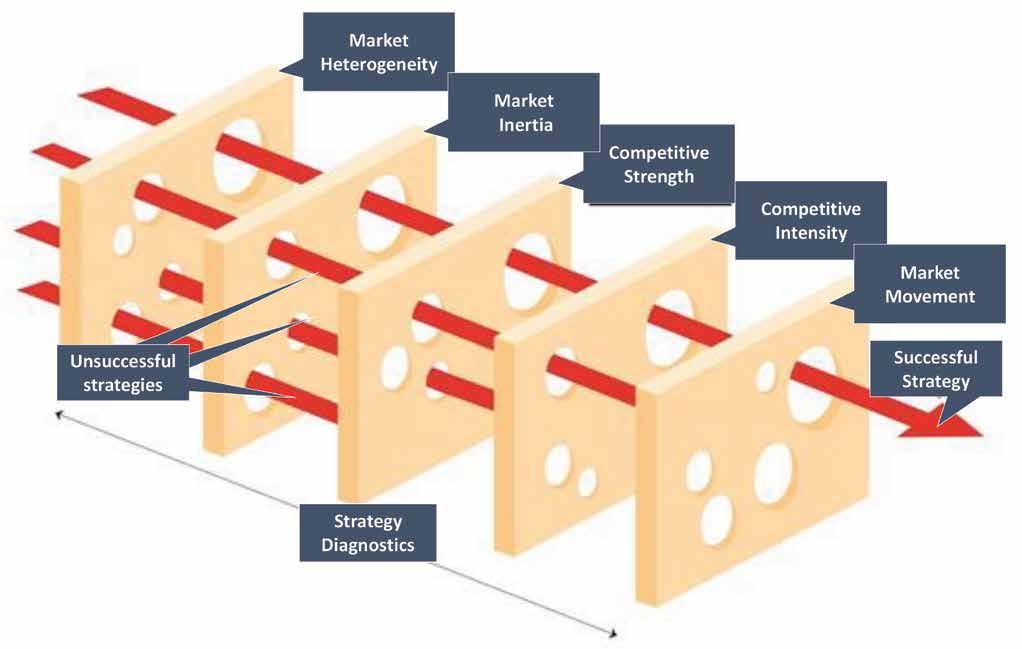

In life sciences, such as pharma and medtech, marketing strategies often fail to deliver on their promises. This is because, to work effectively, 5 critical factors must align perfectly. Researchers refer to this as the swiss cheese model because it is like seeing through a cheese when all the holes must align. In this article, Professor Smith describes those five factors and how to manage their alignment to ensure that your strategy delivers what it promises.

Advertisement

As you look at your newly-written marketing plan, you might want to reflect for a moment how much it resembles an airliner: it took a lot of effort to build, you want to be as sure as you can be that it will fly and not crash but once it takes off it is difficult to repair. The biggest difference between a marketing strategy and an airliner is that, whilst air crashes are extremely rare, research shows that the majority of marketing strategies crash, in the sense that they

do not deliver what they promise. How many marketing plans have you read that you would trust your life to?

It was these similarities and contrasts that led me to explore what lessons marketing strategists in the pharma, medtech and other life science industries could learn from the aviation industry. The exemplary safety of air travel is a triumph of rigour and professionalism that has arisen out of many tragedies. For decades, every disastrous air crash has initiated a thorough investigation. From this has emerged the science of accident prevention, built on the finding that the large majority of accidents arise from a very few causes. Armed with this knowledge, I began to research what the major causes of marketing strategy failure in life science markets were. My findings were clearer than I expected and they developed into a simple, practical process, analogous to the preflight checks performed before every flight, that pharma and medtech marketing professionals can and should use.

A first step: Finding your aircraft

Just as an aircraft technician will first ask “Which aircraft am I testing?”, it’s important to be clear what level of marketing strategy we are testing. My work didn’t concern high level strategies, such as which industry to be in or which disease area to enter. Nor was it concerned with tactical programmes, such as how to promote the product. Instead it concentrated on what is correctly called the Marketing Strategy, meaning that set of resource allocation decisions about which market segments to compete for and what value propositions to offer each segment. Surprisingly, in many marketing plans this is not explicitly stated. You will get more value out of this article if you pause for a moment to write down what your own marketing strategy is in this what segment/what propositions format. It is this clear, succinct marketing strategy statement that you should test.

Failure Factor 1: Market heterogeneity

When I spoke to those marketers whose strategies had not delivered on their promises, the most common thing I heard was “It did work but only for a minority of prescribers, patients and payers”. What this revealed was that many target markets are heterogenous mixtures of different needs and wants. Successful strategies make sense of this heterogeneity and define their targets

as groups whose behaviour is homogenous, since it is shaped by the same motivations. For example, if you target a disease category, say “uncontrolled severe asthma”, then the huge variety of patient behaviours, prescriber preferences and payer constraints within that category makes it very heterogenous. Any single value proposition you make to that category may appeal to some of it but can never appeal to all of it. By contrast, if you target a segment defined as “adherent, motivated but uncontrolled severe asthma patients under innovative, engaged prescribers working in a permissive, value-oriented payer environment” then it is much more likely that the whole segment will behave and respond in the same way. Your marketing strategy will then have a much higher return on investment. In short, the reason many pharma marketing strategies fail is that their target is not a homogenous segment but rather a heterogenous category.

Failure Factor 2: Market inertia

The second theme to emerge from my interviews was “They liked what we offered, just not enough to change”. This exposed the simple fact that customers always have choice and compare your value proposition to their alternatives, including their current practice. And since, in medical settings, switching almost always has costs and risks, they will only adopt your offer if it is demonstrably better than that alternative. Successful strategies, therefore, offer a value proposition whose aggregate costs and benefits, be they clinical, economic or other, are clearly greater than the aggregate of the alternative. This may sound obvious, but recently published research shows that most pharma strategies make value propositions that are inferior or only marginally superior to the incumbent alternative. Offering little or no reason to change and faced with the sometimes-significant costs and risks of changing, it is unsurprising that many prescribers, payers or patients display apathy towards new products. This is even more true when

change is laborious, such as modifying existing care pathways. This embedded market inertia is a powerful force and many marketing strategies in life science markets fail because they simply do not offer enough value to overcome it.

Failure Factor 3: Competitive strength

After market heterogeneity and inertia, the third failure factor to emerge from my research was competitive intensity, otherwise known as the David and Goliath factor. In the words of one executive “The market leader was just too big. They overwhelmed us”. This comment reveals the issue of competitive intensity, when your competitor enjoys an insuperable resource superiority over you. My research revealed that, whilst this was a common cause of strategy failure, some “David” companies do find a way to kill their opposing “Goliath” in the same way as the biblical hero, by avoiding direct competition. By choosing to compete in a different segment and to compete with a different value proposition from their opponent, they largely nullify their opponent’s strength. These successful Davids focus on achieving a very high share of their target segment rather than a small share of their overall market. Almost always, this leads to a better return on investment than a lessfocussed, whole-market strategy. The lesson here is that marketing strategies fail when they compete head-on with larger rivals.

Failure Factor 4: Competitive Intensity

The fourth failure factor described in my research interviews was when competitors had a particular strength that could not be overcome, such as brand loyalty, low cost or some clinical efficacy factor. “We couldn’t get past their argument” was a typical cry of executives in this case. Again, there was an interesting contrast with those companies that had overcome their competitors’ “unbeatable” strength. Using the market heterogeneity mentioned in failure factor 1, these successful companies focus their resources into a market segment where their own strengths – for example, ease of use or low side effect profile – are important and where their own weaknesses – for example, their cost or their brand reputation – are less relevant. At the same time, they withdraw resources from market segments where their strengths are not appreciated and their weaknesses are important to patients, payers or professionals. By aligning their marketing strategy (remember: choice of target and value proposition!) so as to leverage their strengths and mitigate their weaknesses, these companies chose to fight the battles they were most likely to win. By contrast, firms that did not seriously consider their own relative strengths and weaknesses inevitably found themselves fighting a battle in which they were at a disadvantage. Failure factor 4 therefore reveals that marketing strategies fail when they neglect to fully consider internal strengths and weaknesses.

Failure Factor 5: Market Movement The fifth finding of my research was perhaps the saddest. Some executives told me “We did everything right, but the market moved”. This of course reveals the obvious truth that pharma and medtech companies operate in a world of rapid social and technological

change. By contrast, regulation and technical complexity means that life sciences companies can rarely change quickly. This means that our marketing strategies cannot afford to wait, see and then react to market change. Instead, it means that marketers must anticipate where their market is headed and design strategies to fit with tomorrow’s market, not yesterday’s. Again, the contrast between firms that did this and those that did not anticipate market change was informative. The latter focused on the ‘near’ market environment of customers and competitors, identifying only narrow and short-term changes in both. The former, anticipatory firms who futureproofed their strategy, looked wider to consider the ‘far’ market environment that, over time, shapes the market. This works because the ‘far’ environment of sociological, political, economic and technological trends ultimately and inexorably shapes the changes in the ‘near’ market environment. Hence the final lesson of marketing strategy failure is that strategies must anticipate market change and cannot hope to react to it.

The Swiss Cheese strategy

In addition to identifying the five factors that account for most marketing strategy failures, my research also identified a vitally important reason why it is harder to make a marketing strategy failure-proof than it is to make an airliner safe. Earlier work by Reason and other safety researchers finds that for a crash to happen, multiple errors must align. For example, bad weather rarely causes an accident unless it is compounded by pilot error and mechanical failure. But the opposite is true in marketing strategy, which only succeeds if all five failure factors are avoided. In other words, for an air crash to happen usually needs multiple things to go wrong. For a marketing strategy to work, all five failure factors need to be understood and allowed for. This discovery leads to the Swiss Cheese model of marketing strategy effectiveness, as shown in figure 1.

From Research into Practice

As useful as it is to identify these five failure factors, the real value of my research can be found in its practical application to the marketing strategy process. The detailed findings of the research, which space does not permit here, have led to the creation of a practical tool that allows marketing strategists to evaluate their own marketing strategy, identify exactly where it is at risk of failure and to correct those weaknesses before implementation. Using this Strategy Diagnostic tool, the pharma and medtech marketers can focus their improvement efforts onto the small number of issues that make the most difference. This novel and practical tool for pharma and medtech marketers is detailed in my book ‘Brand Therapy’ and you can also find a 20-minute overview of it on my YouTube channel. When used by brand teams, it empowers them to objectively and systematically improve their marketing strategies and to evaluate competing strategy options.

Getting Professional

This research, and the Strategy Diagnostics tool that emerges from it, is a new and effective tool for marketing professionals in the life sciences industry. It gives marketing strategists an instrument for being more effective and more successful than their competitors. But in one sense the Strategy Diagnostics tool is old and established in our industry. As anyone who has worked in R&D, Clinical Trials or Manufacturing will tell you, professionals in those functions have used analogous tools for decades. By considering their own failures and mistakes, our colleagues in those functions have developed good practice tools and guidelines in such as GMP, GCP and GLP. Their highly-effective tools are one of the things that marks them out as professionals. It is a level of professionalism that their pharma and medtech marketing colleagues should aspire to and emulate.

AUTHOR BIO

Brian D Smith is a world-recognised authority on the evolution of the life sciences industry. He welcomes comments and questions at brian.smith@pragmedic.com