JULY / AUGUST 2020

PIONEER PHOTOGRAPHERS TRAVELAIR WORKHORSE CUB PASSION

Twin CHAMPION

L I G H T N I N G

D O E S N ’ T

F RO M

T H E 2 0 2 1 F O R D M U S TA N G M A C H - E Preproduction vehicle image shown. Production models may differ. Available late 2021.

T H E

J U ST

S KY

CO M E

Message From the President

July/August 2020

SUSAN DUSENBURY, VAA PRESIDENT

STAFF Publisher: Jack J. Pelton, EAA CEO and Chairman of the Board Vice President of Publications, Marketing, and Membership: Jim Busha / jbusha@eaa.org Senior Copy Editor: Colleen Walsh

Holding Pattern Clearing the way for AirVenture 2021 ABOUT NOW IS THE TIME when so

many of us under normal circumstances would be making plans for a pilot’s most favorite time of the year — AirVenture. Ordinarily, we’d be washing our planes and maybe changing the oil. We’d be looking for that perfect pair of shoes to carry us comfortably through a week of yet again exploring the grounds at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh to see what treasures we could find. We’d be excited about visiting with all of our aviation family who we have missed seeing during the past year. But this is the most unusual of times. For those of us with a passion for airplanes, we’ll have to wait another year for aviation’s greatest show on earth. However, the planning for AirVenture 2021 has already begun. I recovered from the disappointment of the cancellation of AirVenture pretty quickly and started looking forward to AirVenture 2021. At Vintage we decided to take this “opportunity” (I’m trying to be positive here!) and run with it. At the time of this writing the EAA Aviation Museum and grounds are closed. That includes our office and all of the Vintage grounds. VAA Administrative Assistant Amy Lemke is working from home. The last that I heard was that she goes to work in her pajamas with her cat in tow. Not bad duty! Right now, all of the Vintage volunteer work parties are on indefinite hold. But in spite of it all we are managing to get things done.

Copy Editor: Tom Breuer Proofreader: Meghan Plummer Graphic Designer: Cordell Walker

ADVERTISING

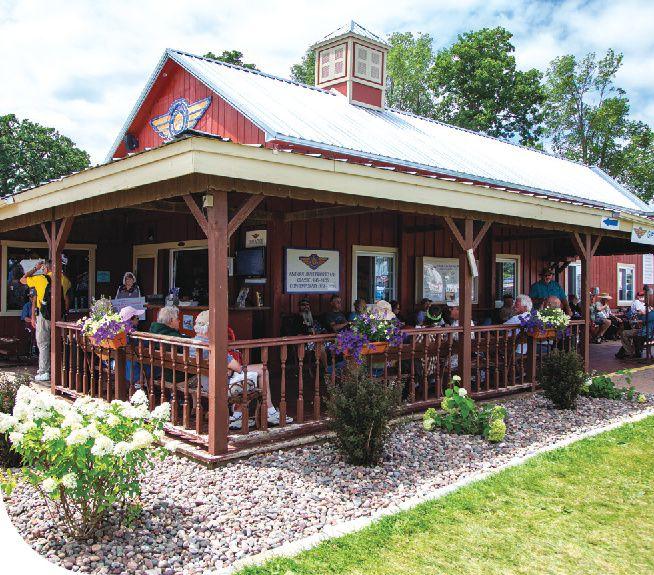

Contractors are allowed on the EAA grounds now, and Vintage has several crews working in Vintage Village and at the Tall Pines Café making some much needed repairs and upgrades. I think that you will all be pleased with what you see when you do fly into Wittman Regional Airport in July 2021. Just maybe I’ll get my airplane project finished and fly something other than my Cessna 180 up to Oshkosh. Trust me. It will be a slow trip if I do!

Advertising Manager: Sue Anderson / sanderson@eaa.org

All of the programs that Vintage had planned for AirVenture 2020 will be carried forward to AirVenture 2021 along with those programs that we had scheduled for AirVenture 2021.

Current EAA members may join the Vintage Aircraft

Mailing Address: VAA, PO Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903 Website: www.VintageAircraft.org Email: vintageaircraft@eaa.org

Visit www.VintageAircraft.org for the latest in information and news and for the electronic newsletter, Vintage AirMail.

Association and receive Vintage Airplane magazine for an additional $45/year. EAA membership, Vintage Airplane magazine, and one-year membership in the EAA Vintage Aircraft Association are available for $55 per year (Sport Aviation magazine not included). (Add $7 for International Postage.) Foreign Memberships Please submit your remittance with a check or draft drawn on a United States bank payable in United States dollars. Add required foreign postage amount for each membership. Membership Service P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903-3086 Monday–Friday, 8 AM—6 PM CST Join/Renew 800-564-6322 membership@eaa.org EAA AirVenture Oshkosh www.EAA.org/AirVenture

CONTINUED ON PAGE 64

PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY OF EAA ARCHIVES

888-322-4636

www.vintageaircraft.org

1

Contents FE AT UR E S

12 The 616 Aircraft Photographers Pioneers of aviation history By Brian R. Baker

24 Mini Multi Jason Somes and his Champion 402 Lancer By Hal Bryan

34 A 1929 Travel Air S-6000-B This memory maker exemplifies endurance flying! By Sparky Barnes

44 Are You Ready to Enjoy the Journey? A Piper Cub in every hangar By Harry Ballance

52 The Haggerty J-5A Piper Cruiser By Budd Davisson with Jack Haggerty

2

July/August 2020

QUESTIONS OR COMMENTS? Send your thoughts to the Vintage editor at jbusha@eaa.org. For missing or replacement magazines, or any other membership-related questions, please call EAA Member Services at 800-JOIN-EAA (564-6322).

PHOTOGRAPHY BY LYLE JANSMA

July/August 2020 / Vol. 48, No. 4

COLUM NS COV ER S Front Scott Slocum zeros in on Jason Somes and his Champion 402 Lancer.

01

Message From the President

By Susan Dusenbury

04

Friends of the Red Barn

06

Hall of Fame Inductee 2020

08

How To? Replace Streamline Wire Terminal Ends By Robert G. Lock

Back Connor Madison catches a 1929 Travel Air S-6000-B resting on the grass.

10

Good Old Days

60

The Vintage Mechanic Materials & Processes, Part I By Robert G. Lock

64

Flymart

www.vintageaircraft.org 3

Friends of the

RED BARN 2020-2021

DEAR FRIENDS,

For one week every year a temporary city of about 50,000 people is created in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, on the grounds of Wittman Regional Airport. We call the temporary city EAA AirVenture Oshkosh. During this one week, EAA and our communities, including the Vintage Aircraft Association, host more than 500,000 pilots and aviation enthusiasts along with their families and friends. With the support of the very capable VAA officers, directors, and more than 600 volunteers, the Vintage Aircraft Association annually welcomes more than 1,100 vintage showplanes throughout the week of AirVenture on our nearly 1.3-mile flightline. We continue to work to bring an array of valuable services and interesting programs to the VAA membership and to all of our Vintage Village visitors during this magical week. Across Wittman Road and in front of our flagship building, the VAA Red Barn, we will feature some really interesting airplanes, including the beautiful past Vintage Grand Champions, an array of fun and affordable aircraft, and some exciting rare and seldom-seen aircraft. In Vintage Village proper we have a hospitality service, a bookstore, a general store (the Red Barn Store), youth programs, educational forums, and much more. As you can imagine, creating the infrastructure to support these displays, as well as the programs offered during the week, is both time-consuming and costly, but they are made possible thanks to donations from our wonderful members.

4 July/August 2020

As your president, I am inviting you on behalf of the Vintage Aircraft Association to join our association’s once-a-year fundraising campaign — Friends of the Red Barn (FORB). The services and programs that we provide for our members and guests during AirVenture are made possible through our FORB fundraising efforts. A donation from you — no matter how large or small — supports the dream of aviation for aviators and aviation enthusiasts of all ages and levels of involvement. We invite you to join us in supporting this dream through the Friends of the Red Barn. I thank you in advance for your continued support of the Vintage Aircraft Association as we move this premier organization forward on behalf of our membership and the vintage aircraft movement. If you have already made a 2020-2021 FORB contribution, thank you for your dedication and support of the vintage aircraft movement. I look forward to seeing you all in Vintage Village at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh beginning July 26, 2021! SUSAN DUSENBURY, PRESIDENT VINTAGE AIRCRAFT ASSOCIATION

PHOTOGRAPHY BY LYLE JANSMA, CONNOR MADISON

C A L L F O R V I N TA G E A I R CR A F T A S S O CI AT I O N

Nominate your favorite vintage aviator for the EAA Vintage Aircraft Association Hall of Fame. A great honor could be bestowed upon that man or woman working next to you on your airplane, sitting next to you in the chapter meeting, or walking next to you at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh. Think about the people in your circle of aviation friends: the mechanic, historian, photographer, or pilot who has shared innumerable tips with you and with many others. They could be the next VAA Hall of Fame inductee — but only if they are nominated. The person you nominate can be a citizen of any country and may be living or deceased; his or her involvement in vintage aviation must have occurred between 1950 and

the present day. His or her contribution can be in the areas of flying, design, mechanical or aerodynamic developments, administration, writing, some other vital and relevant field, or any combination of fields that support aviation. The person you nominate must be or have been a member of the Vintage Aircraft Association or the Antique/Classic Division of EAA, and preference is given to those whose actions have contributed to the VAA in some way, perhaps as a volunteer, a restorer who shares his expertise with others, a writer, a photographer, or a pilot sharing stories, preserving aviation history, and encouraging new pilots and enthusiasts.

To nominate someone is easy. It just takes a little time and a little reminiscing on your part. •Think of a person; think of his or her contributions to vintage aviation. •Write those contributions in the various categories of the nomination form. •Write a simple letter highlighting these attributes and contributions. Make copies of newspaper or magazine articles that may substantiate your view. •If at all possible, have another individual (or more) complete a form or write a letter about this person, confirming why the person is a good candidate for induction. We would like to take this opportunity to mention that if you have nominated someone for the VAA Hall of Fame, nominations for the honor are kept on file for three years, after which the nomination must be resubmitted. Mail nominating materials to: VAA Hall of Fame, c/o Amy Lemke VAA PO Box 3086 Oshkosh, WI 54903 Email: alemke@eaa.org

Find the nomination form at www.VintageAircraft.org, or call the VAA office for a copy (920-426-6110), or on your own sheet of paper, simply include the following information: •Date submitted. •Name of person nominated. •Address and phone number of nominee. •Email address of nominee. •Date of birth of nominee. If deceased, date of death. •Name and relationship of nominee’s closest living relative. •Address and phone of nominee’s closest living relative. •VAA and EAA number, if known. (Nominee must have been or be a VAA member.) •Time span (dates) of the nominee’s contributions to vintage aviation. (Must be between 1950 to present day.) •Area(s) of contributions to aviation. •Describe the event(s) or nature of activities the nominee has undertaken in aviation to be worthy of induction into the VAA Hall of Fame. •Describe achievements the nominee has made in other related fields in aviation. •Has the nominee already been honored for his or her involvement in aviation and/or the contribution you are stating in this petition? If yes, please explain the nature of the honor and/or award the nominee has received. •Any additional supporting information. •Submitter’s address and phone number, plus email address. •Include any supporting material with your petition.

2020 Hall of Fame Inductee

Steve Dyer IT IS WITH THE GREATEST HONOR that the Vintage Aircraft Association has chosen Stephen Edward “Steve” Dyer as the EAA Vintage Aircraft Association Hall of Fame inductee for 2020. From 1976 until 2005 Steve was the president of Univair Aircraft Corp., a manufacturer and supplier of quality aircraft parts and supplies for general aviation. Steve has been an avid supporter of the vintage aircraft movement throughout his lifetime. He has been instrumental in developing replacement parts to keep our aging aircraft in the air while enjoying his passion for aviation through aircraft that he has restored and flown including his Oshkosh award-winning D-17S Staggerwing Beech, a Dyercraft (obviously, his own design!), and a Stinson 108-5 just to name a few. The Stinson 108-5 was developed by Univair as a new model on the type certificate. Only the prototype was built by Univair, but 18 or 19 conversion kits were sold in the late 1960s. Univair Aircraft Corp. was formed in the Denver, Colorado, area on February 25, 1946, by Army Air Corps veteran J.E. “Eddie” Dyer and fellow World War II veteran Don Vest. Originally formed as the Vest Aircraft Co., this new organization would later become the Univair Aircraft Corp. At its formation, the company was a full-service aircraft sales and repair facility with Don handling the sales and financing of airplanes while Eddie managed the aircraft repair part of the business. After the tragic death of Don in an aircraft accident, Eddie became the sole proprietor of Univair. This accident occurred at about the same time that the supply of used aircraft parts was rapidly evaporating.

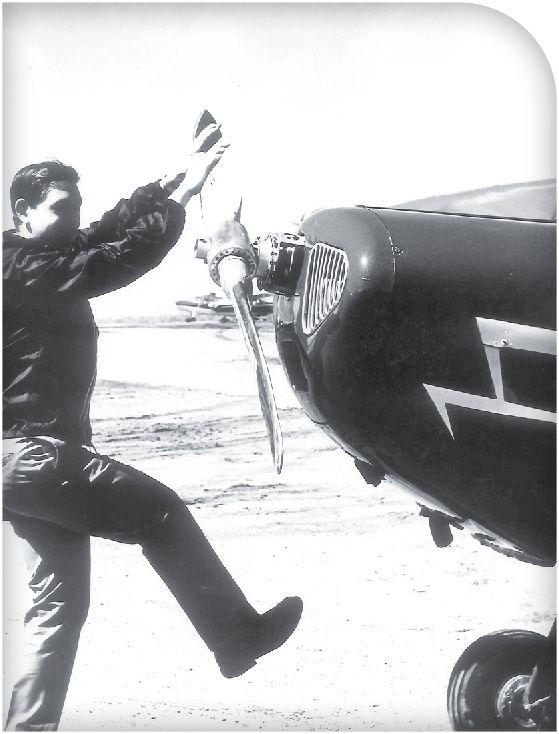

Steve always had a “leg up” when it came to flying the vintage aircraft in his life. Here he prepares to handprop one of the many aircraft he has flown.

He has been instrumental in Steve Dyer

developing replacement parts to keep our aging aircraft in the air while enjoying his passion for aviation through aircraft that he has restored and flown. Eddie became aware of the dwindling supply of airworthy aircraft parts and started manufacturing new replacement parts. Business continued along these lines until Eddie’s untimely death in 1963. It was then that Eddie’s very capable wife, Veda, took control of the company.

6 July/August 2020

PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY OF EAA ARCHIVES

Under Veda’s management the company thrived, and in 1976 Veda turned the company over to her 30-year-old son, Steve. It was under Steve’s leadership that the company added thousands of FAA-PMA approved parts. The result is that with the exception of the airline industry, Univair holds more FAA-PMA approvals than any other airframe parts manufacturer. When Piper closed its operations at the Lock Haven factory, wing ribs for the older Piper aircraft were going to be discontinued. Realizing the negative impact that this would have on general aviation, Steve then led the development of STC-approved stamped aluminum replacement ribs for most all of the older Piper aircraft that had been type certificated with the truss-type ribs. Steve had the foresight to purchase Piper’s entire inventory of available excess parts for fabric-covered airplanes. He purchased these parts for resale and for use in the development of patterns for future manufacturing. After an FAA airworthiness directive announced that “sealed” lift struts did not need the repetitive and time-consuming (costly!) inspections per the airworthiness directive, Steve saw this as an opportunity to serve the general aviation aircraft owners of strut-braced aircraft. Steve was instrumental in the development of and approval for lift struts for the entire line of Piper strut-braced aircraft. Besides supporting classic general aviation aircraft with FAA-PMA approved parts, his company also purchased the type certificates for the Ercoupe, the Stinson 108 series aircraft, and Swift aircraft as well as the Flottorp line of propellers. Without Steve’s foresight these aircraft would simply have no replacement parts support. The Swift type certificate was later sold to the Swift Museum Foundation located in Athens, Tennessee. In the early 1980s, Steve was highly involved in obtaining two STCs to replace the Franklin engine that was originally installed in the 108 series Stinsons. The STC called for use of either the Lycoming O-360 180-hp engine or the Lycoming IO-360 200-hp engine. At about the same time many of the fabric-covered airplanes of the ’50s and ’60s were developing airworthiness issues due to lack of replacement parts. In addition to the above-mentioned wing ribs, Univair manufactured and made available assembled and almost ready-to-cover FAA-PMA approved Piper aircraft wings for some of Piper’s most popular models. These models included the J-3, PA-11, PA-12, PA-14, PA-18, PA-20, and PA-22 aircraft. Also available for sale through Univair are FAA-PMA fuselages for the J-3, and PA-18 models. In addition to the foregoing, Univair developed control surfaces, landing gears, engine cowlings, and spinners. Fortunately for the vintage aircraft movement, approved replacement parts have also been developed by Univair for other aircraft manufacturers.

Steve and his mother Veda pose in front of his biplane.

Just one of the many awards Steve has received during his career.

In the late ’70s, Univair purchased and brought to market an STC’d kit to convert Piper’s PA-22 Tri-Pacer to a PA-22/20 Pacer. This conversion resulted in a better-performing and more aesthetically pleasing airplane. Many airplanes have been converted, and this kit is still available today. In 2005 the management of Univair was turned over to the third generation of the Dyer family, James E. “Jim” Dyer. That same year, Steve took over as chairman of the board for the company. Today, he still serves in that capacity. He and his wife, Susan, regularly commute between Colorado and Wyoming in the family Bonanza.

www.vintageaircraft.org

7

How To? ROBERT G. LOCK

REPLACE STREAMLINE WIRE TERMINAL ENDS

Photo 3

BY ROBERT G. LOCK

STREAMLINE WIRE TERMINAL ENDS are made of high-grade

steel and heat-treated for strength. After this process the ends are plated with cadmium for surface protection against corrosion we call rust. Cadmium is a sacrificial plating process, and corrosive elements will eventually eat away the plating, exposing terminal ends to the corrosive atmosphere. When this happens the ends must be removed, cleaned, and inspected, and the plating reapplied. Photo 1 shows the effects of corrosion on terminal ends. But when you remove these ends the rigging can be affected, causing the owner to have the airplane re-rigged. But now you can use my process of replacing terminal ends without having to re-rig the airplane. Here’s how. Photo 1

Photo 2

8 July/August 2020

First, check the wire tension of each wire before you loosen anything. This will assure the airplane will go back into rig when wires are replaced. I have a Pacific Scientific wire tensiometer that dates back to the Stearman days during World War II. It is very handy. Photo 2 shows the tensiometer in use. Record the tension of each flying wire and each landing wire; however, landing wire tension is determined by flying wire tension as they pull against each other. The Stearman maintenance manual gives recommended wire tensions; most other old aircraft have no such data. Loosen the flying wires, but don’t touch the landing wires because they set wing dihedral. Count the number of full turns when the flying wires are loosened, making the turns all the same for both sides of the airplane, and then mark the wires using masking tape and a pencil to reflect each wire’s location. Remove the flying wires from the airplane and unscrew both terminal ends and jam nuts. Now, support the lower wings at the strut point, raising both wingtips to loosen the tension on the landing wires. Loosen the jam nut but not the terminal ends and then remove each wire individually. Using a long 2-by-4, lay each landing wire on the 2-by-4 and drill holes through the terminal end, inserting a bolt to make sure alignment is correct. Photo 3 shows the wires on the 2-by-4. Carefully mark each wire and location (front landing left, aft landing left, etc.). Then remove all terminal ends and jam nuts and install the newly plated parts. I have the parts plated with Class I type plating that is silver in color, just like the original plating as in Photo 4. Begin by installing the landing wire terminal ends and jam nuts, putting the same number of turns in each end (I usually start with 20 complete turns) and then adjust later. Photo 4 shows the new ends just coming back from the plating shop. Once the exact length of each wire has been set, the landing

PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY OF EAA ARCHIVES

FREE SHIPPING From Univair Photo 4

Univair offers Free Ground Shipping on orders over $300.00 and Free Freight Shipping on orders over $3,000.00 to addresses in the lower 48 United States. Other conditions apply. See our website for full details on our free shipping promotion. We carry the largest inventory of parts in the world for: Piper • Cessna • Aeronca • Ercoupe • Taylorcraft • Stinson • Luscombe

wires are reinstalled in the proper location. Once again, do not alter the length of the landing wires. Do the same thing to each of the flying wires, screwing on each terminal end by about 20 turns and install these wires. Remove the lower wingtip supports so the wings hang on the landing wires. I install cotter pins in clevis pins and align with the wires, and then I tension all flying wires to the tension reading before removing. Photo 5 shows the reinstallation of flying wires but before the final tension is set. When tensioning the flying wires, work on both sides of the aircraft. I do not put all tension in one side because it puts a strain on the structure, and on some biplanes it can pull the wings off-center. Center section roll wires generally have two parallel diagonal wires that place the center section centerline directly above the longitudinal axis of the aircraft. If there are two wires, measure and record tension, then remove one wire from each side to replace the terminal ends and then tension until the reading is the same. Tension on parallel streamline wires should be within 100 pounds of each other. When tension is set, remove the remaining wires to replace the terminal ends. The center section should remain in its existing position. I have used this method successfully on my Command-Aire and on Stearman aircraft. It has worked well. Just remember that whatever length and tension you have before removing a wire, you should have the same length and tension after you reinstall it. Otherwise, rigging will be compromised.

Toll Free Sales: 1-888-433-5433 Shop Online: www.univair.com

AIRCRAFT CORPORATION

2500 Himalaya Road • Aurora, CO • 80011 Info Phone ....................... 303-375-8882 Fax ........800-457-7811 or 303-375-8888 Email ............................info@univair.com

ALL MERCHANDISE IS SOLD F.O.B., AURORA, CO • PRICE AND AVAILABILITY SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE • 04-24-20

Photo 5

www.vintageaircraft.org

9

Good Old Days

From the pages of what was ... Take a quick look through history by enjoying images pulled from publications past.

10 July/August 2020

www.vintageaircraft.org 11

PIONEERS OF AVIATION HISTORY BY BRIAN R. BAKER

IN THE LATE ’20S, following Charles Lindbergh’s

famous trans-Atlantic flight, the aviation industry began to rapidly expand in the United States and throughout the world. Aviation caught the public eye, and nearly everyone had at least some interest in it. As we all know, aviation is one of the most expensive avocations, and at the time few people could actually afford to fly or be personally involved at any level. Many people without the financial

CHECK OUT THE DIGITAL EDITION of Vintage for a photo gallery on the pioneers of aviation history.

12 July/August 2020

resources to participate directly chose a different route: aviation photography. Some people, mostly young men, began to hang around airports taking pictures of the airplanes that were in use at the time. In 1928, Ben Heinowitz, an enthusiast from Mountainside, New Jersey, began to wonder if perhaps other people throughout the country shared the same interest. In the August 1933 issue of Model Airplane News, he wrote:

“I started in a small way back in ’28 to take pictures of representative type aircraft which I found at the local fields I frequented and did some flying from (mere passenger). After a while, as this hobby became more absorbing, I wondered if there were others through the states engaged in the same hobby. With a bit of scouting around, I made contact with those interested in exchanging aircraft photos. Returns were so gratifying, the thought of forming a club came into mind and on airing said thought, to the fellows who I had started swapping shots with, the idea over first rate, which as a result, gave us the nucleus of a club, devoted to the exchanging of aircraft photos. The club was officially organized in May 1930, with members in Washington, California, Colorado, and New Jersey. “Since the birth of the club, we have expanded considerably, having accredited member collectors in all parts of the country and abroad.” The organization was officially named the International Amateur Aircraft Photo Exchange, and during the ’30s many new members were accepted into the club. Prospective members had to meet the following requirements: 1. A listing of at least 50 negatives of representative

type aircraft from which prints could be made. Foreign members were required to have only 25. 2. Members had to have a working knowledge of

photography as applied to aviation, taking photos that showed the complete plane, and giving the best detail of that particular plane. 3. Members were required to cooperate in mat-

ters related to the club and obey all rules and regulations. 4. Members were required to have a general knowl-

edge of the representative production type planes and engines and be able to provide the desired information along with photos of the planes.

Kodak 616 Camera

There doesn’t seem to be any documentary evidence to suggest that the 616 camera and film were standardized, but that is apparently what happened. At the same time, railroad photographers, who organized their activities along similar lines, used postcard cameras that shot 122-sized film, but postcard cameras were large and bulky even by 1920s standards, and the 616 camera became standard, mainly because it used the smallest-sized film that would produce an adequate-sized contact print, making enlarging unnecessary except in special situations. As most aircraft photographers during the Great Depression were operating on a financial shoestring, and nearly all did their own developing and printing, the 616 camera seemed ideal for this kind of photography. The IAAPE developed standards for photography of airplanes that bordered on the artistic. As this developed, photographers who contacted other members for trading frequently expressed their requirements. In a March 1938 letter from Bill Yeager, an established Cleveland aircraft photographer and IAAPE member, to the then-neophyte collector William T. Larkins, Yeager stated his standards: “As to what I can use, can most always use anything in the commercial, racing, and military line. So long as it fills the following restrictions. • Ailerons, rudder must be straight • No canvasses over cockpits, motors • No hangars or people around or in background • Doors closed in ships”

There were no dues or officers, but membership was divided into two classes: juniors and seniors. Junior members were “freelance members, corresponding and exchanging at their convenience,” while senior members were the “backbone members, active in club work right along.” The organization expanded and published its business in issues of Model Airplane News and Model Aircraft Engineer during the ’30s. The IAAPE lasted until the late ’30s, when an incident involving the publication of a photo of a Navy prototype fighter caused the club to disband.

Therefore, an acceptable photo was one in which the airplane was posed in the open with no people or objects around it, nothing in the background, with all cowlings, canopies, panels, and doors closed, with control surfaces in a neutral position and, of course, with the sun in the proper position. This was a tall order in those days, and it must have been very time-consuming for the photographer to wait for those conditions. However, since there were relatively few aircraft available to photograph, most collectors went along with these standards, and a vast number of photographs were taken and exchanged. The 616 negative became standard, a type of currency used by airplane photographers for trading.

www.vintageaircraft.org 13

PRESERVATION OF PHOTOGRAPHS AND DOCUMENTATION

CLICK HER

E TO SEE A FLIC KR GALLERY ON THE PIONEERS OF AVIATION HIST ORY

At that time, most photographers viewed themselves as collectors rather than the historians they later became. The pictures were art forms, and the objective seemed to be to amass a large collection of 616 negatives and prints of aircraft in pristine conditions and locations. Prints were usually mounted in albums, although some collectors used 3-by-5-inch card file boxes to keep them in order as new additions were received. Negatives were filed in bank-style coin envelopes, usually about 3-by-5 inches in size, with the identification typed or printed on the envelope, although a few collectors printed the type and sometimes the engine and location on the clear edges of the negatives using a fountain pen and indelible ink. Information (which was sometimes, but not always, recorded) could include the manufacturer; model; registration or military serial number; markings; military service, unit, or owner/operator; special information, such as pilot in the case of a racing or record-breaking plane; and documentation on where and when the photo was taken. Occasionally, the name of the original photographer was also listed, but this was comparatively rare, and that still presents photo credit problems today. As negatives often changed hands several times, names of the original photographers were often lost, and photos usually get credited to the collection from which the photo was obtained. Since the specific identification of a particular airplane is important, many photographers made sure that the license, serial number, or other markings were visible in the photo, but this was not always the case, and most of us have many photos of aircraft for which we know the make and model but not the registration or serial number. Of the approximately 250 collectors believed to have been active in the hobby from the beginning through the ’70s, when 616 film went out of production, many did not stay active in the hobby for long, and their collections were eagerly bought up by other collectors who pulled out the material that did not duplicate what they already had. They then traded off or sold the rest to other collectors. This has extensively diffused the material, and a fortunate result of this has been the preservation of material in case a fire or other disaster causes the loss of a collection. This has happened to several collections, as has the disposal of material after the death of a collector by family members unaware of its historical value.

SECURITY TOP: North American P-51D Racer, probably Cleveland, about 1948. MIDDLE: Republic XF-12 Rainbow Experimental Recon plane. Probably New York, c. 1948. BOTTOM: Boeing F4B-4. 1930s photo by William T. Larkins, probably at NAS Oakland.

14 July/August 2020

As the world moved toward war in the late ’30s, a new problem emerged — security. Previously, military aircraft could easily be photographed, and new prototypes and service models were often photographed by collectors, mainly when these aircraft landed at civilian airfields, a common occurrence during the ’30s. Military aircraft became less accessible, and even airport police sought to prevent people from taking photos of military aircraft. Civilian airplanes were still available for photography, and as aviation expanded in the late ’30s, there was no shortage of types to photograph. Photographers also took advantage of the numerous air shows and displays, although access to flightline areas during times when good photos could be taken was sometimes difficult to get.

WORLD WAR II

A number of 616 aircraft photographers served in the military during the war, and their pictures form a priceless record of some of the aircraft used during this period. Although cameras and photography were officially prohibited on military flightlines, servicemen routinely ignored this regulation and created many valuable photos. In addition, color film, notably Kodachrome, made color slides possible, and some photographers, not all of them 616 collectors, created photos that are now prized by collectors and publishers alike, as 616 black-and-white photos do not provide the information that color photos do. A few photographers, including Bill Larkins, used 616 color film to some extent, but this seems to have been fairly rare, as color film was much more expensive than the traditional black-and-white variety. To add to the confusion, a few photographers used orthochromatic film, which causes distortion in color tones, with blacks and reds appearing similar and yellow appearing very dark. This causes untold confusion today among historians trying to determine the color of an aircraft based on black-and-white photos. Some of the more prolific photographers, including Howard Levy, Bill Larkins, Peter Bowers, Art Krieger, Bill Balogh, Merle Olmstead, and many others, created a priceless record of some of the military aircraft they encountered during the war. Their photos are often credited in publications, and the quality of their work remains unsurpassed. By this time, some photographers came to the realization that their primary role was to be historians rather than merely collectors. As a result, they became less concerned with the artistic setting of an “in the clear” photo and more concerned with preserving a photo of the airplane in its operational environment.

TOP: Northrop A-17 taken 1940-41. Possibly Krieger. MIDDLE: Republic P-47D South Pacific, c. 1945. BOTTOM: Hamilton Metalplane. Information unknown.

THE POSTWAR PERIOD

After World War II, many of the old-timers slowed down, while a new generation of aircraft photographers appeared on the scene. Those of us who began in the ’50s still had the expertise and guidance of the experts, and many of us received the opportunity to obtain prewar negatives still held as spares by older collectors. The 616 camera still reigned supreme, although some collectors were supplementing their work with 35 mm color slides. The large number of war surplus aircraft that populated American civilian airports in the early postwar period, along with the diversity of airliners and nonscheduled or supplemental air carriers, made aviation photography exciting. There was almost no security at civilian airports, allowing one to wander at will with no challenge. Military airfields were by and large off limits except during Armed Forces Day open houses, where carefully selected aircraft could be viewed and photographed by the public in less than ideal circumstances. To get decent photographs, you had to get on the line early and get your photos before the crowd arrived. Another advantage of that period was that the majority of light aircraft at airports were in open tiedowns, not individual hangars as they are today. A visit to the local airport would yield a large number of older and sometimes unusual types, whereas today these valuable airplanes are nearly always locked away in hangars. I recall visiting many airports and photographing such types as Waco biplanes, Travel Airs, and Stinson Reliants, not to mention the large number of fabric-covered lightplanes that were so common during that time.

www.vintageaircraft.org 15

MECHANICS OF THE HOBBY

As aircraft photography developed as an established avocation during the ’30s and ’40s, certain procedures became standard. We would make the rounds of the local airports on a regular basis, photographing anything we hadn’t seen before. Most photographers shot three, or sometimes five, views of an aircraft, unless there was a reason for better coverage. Most of us shot a one-half front, side, and one-half rear view, while others shot three-quarters front, one-quarter front, side, one-quarter rear, and three-quarter rear views, and occasionally a direct front and rear photo as well. We all shot extra negatives, which used up a lot of film but which also allowed us to accumulate a selection of spare negatives for trading purposes. Obviously, with a rarer or more unusual subject, a greater number of spares could be traded.

TRADING

Trading is what made the hobby really fun and fascinating. Although a few of us did a considerable amount of traveling, most photographers did most of their photography in their local areas. Frequent trips to the local airports would often provide an ample variety of aircraft to photograph, and with a collection of spare negatives accumulated, trading could diversify the collection. Especially prized were contacts in foreign countries or places where a lot of aviation activity occurred. Contact was made through credits stamped on the backs of prints, or sometimes through advertisements in aviation magazines, where a collector would state that he was looking for correspondents in specific places to trade 616 negatives. The respondent would send a sample of his work, describing the type of photography he did, the types of aircraft he photographed, and his overall access to local airports, and if conditions were acceptable, trading would begin. A batch of 10 to 20 negatives would be sent, and the receiver would accept the ones he wanted, returning the rest along with some of his own negatives, or those obtained from others, in trade. The system worked quite well, and most of us added some interesting and historic photos and negatives to our collections in this way. Some collectors traded prints, but most preferred negatives. A few collectors sold prints, but to the true collector, negatives were the preferred trade item. Some collectors are still involved in trading negatives — often original extra views from collections in trade for photos the collector especially wants to obtain. In addition, some collectors routinely photographed aircraft outside of their area of interest in order to obtain trading material for aircraft they were really interested in.

16 July/August 2020

TOP: Curtiss P-40N-5-CU Privately owned, Detroit Wayne Major Airport, (Now Metro) c1952. Brian Baker. MIDDLE: Hunting Percival Provost. Iraqi markings, London, early fifties. JMG Gradidge. BOTTOM: Curtiss P-40N. RAAF. South Pacific, c1944

THE PHOTOGRAPHER AS A HISTORIAN

TOP: Douglas B-23 Dragon U.S. Army bomber, probably Chicago area, c. 1940. Krieger. MIDDLE: Seversky SEV-2AP. Probably Cleveland, c. 1938-39. BOTTOM: Curtiss Kingbird. Data unknown.

In the ’50s, a number of collectors began recording more specific data with their photos. Many collectors listed the aircraft type, registration or serial number, and the place and date the photo was taken. At this time, definite identification of an aircraft was difficult unless the photographer was able to check the manufacturer’s data plate or aircraft registration, which was supposed to be displayed in the cockpit of a civilian airplane, but this was often not visible from the outside. There were no civil registers available to check an “NC” number for owner and serial number; these weren’t available from the FAA until the ’60s. Although civil registers of prewar American civilian aircraft have now been published on such websites as www.Aerofiles.com, there was and is a gap in coverage between the end of World War II and the ’60s, and even the FAA in Oklahoma City lacks accessible data on most of the aircraft sold surplus by the military after World War II. We are better served when it comes to military aircraft, as serial number identification listings are readily obtainable from numerous sources. Some collectors recorded the colors of the aircraft, but without federal standards, this information was not really very useful, and the use of color film made these records unnecessary. Leo J. Kohn of Milwaukee was the first collector I encountered who made extensive color notes, and he is the one who got me started recording this information. A change that showed the shift from collecting to recording history was the decline in the purist approach to in-the-clear photography. Backgrounds were now permissible, and even support equipment and people, such as flight or ground crews, were allowable. I recall being asked by one of the major collectors years ago to trade him a negative of a Navy plane taken at NAS Oakland in the late ’30s. He wanted to trade a shot of the same type “in the clear,” as my negative had in the background a picture of the old hangar on the field. He said that in all his years photographing aircraft at Oakland, he never took a picture showing the hangar in the background, and the hangar had by then been torn down. Another factor in aircraft photography was the recording of the condition of a particular airplane over a period of years. It was not uncommon to photograph an airplane several times during its career, with changes in paint scheme, airline markings, or actual configuration being recorded. These photos are especially useful to any researcher doing an in-depth study of a particular airplane or aircraft type. Occasionally, a photo would be taken of an aircraft immediately before the plane was destroyed in an accident or by a storm, and this increased the value of the photo. Although it wasn’t common during the 616 era, modern photographers, especially of military and airline aircraft, take at least one photo of each airplane in the unit so that they have a complete record of the unit or airline during its operations. Often, 616 collectors are approached by serious researchers and historians seeking information on specific aircraft or units that operated the type — the intent being the publication of a book or magazine article on that particular subject. Often the reward is merely a credit line in the book and, hopefully, a copy of the book after publication, but this is better than nothing, and sometimes it’s a welcome addition to an expanding library. Of course, the owner of a negative has publication rights, and in many cases the original photographer is impossible to determine.

www.vintageaircraft.org 17

THE 616 CAMERA

TOP: Lockheed Orion. Detroit News, Wayne County Airport, c. 1936-37. Bill Balogh. MIDDLE: Curtiss P0-1A. Hawk at Selfridge Field, Michigan, c. 1929 Ray H. Baker. BOTTOM: Thomas Morse S-4 flying in Milwaukee area, 1950s. Leo J. Kohn.

18 July/August 2020

Although there were a number of manufacturers of 616 cameras over the years, the Kodak Monitor Six-16 seemed to be the favorite of collectors. There was a Monitor Six-20, but it didn’t become standard. This was perhaps the top of the line for Kodak. It was a folding-bellows-type camera that shot an eight-exposure roll of film. The 616 film negative measured 2-3/4 by 4-1/2 inches. In the ’50s, Verichrome Panchromatic and Super XX were the common types of Kodak film, although there were other producers, especially in Europe. Super XX was a faster film than Verichrome, but it was also more expensive, so most of us used Verichrome, which sold for 50 cents to a dollar a roll in the ’50s. In addition, another film size, 116, also existed. It had the same dimensions, but the spool was slightly different. The 616 Monitor featured an anastigmat lens with a Supermatic shutter with speeds up to 1/400 of a second and f-stop openings from f-22 down to f-4.5. The lens rotated outward for focusing. A tripod mount was provided, but focusing was done by estimate only, and a light meter was necessary — although most of us shot so much film that we had a standard setting for bright sunlight and a standard focus setting for small or large airplanes. Sighting could be done using the reflective sight, for which the photographer looked down into the sight glass, or with a direct-view folding sight mounted on the top of the camera. There was an automatic film counter on the top of the camera that most of us never used, as we just shot eight shots or looked at the camera’s red glass indicator to check the number of exposures left in the camera. A trigger was mounted on the top of the camera, but there was a part of the trigger mechanism just below the lens that could be operated by the middle finger while using the direct sight, and this worked better and also reduced camera shake. A delayed-action shutter was also mounted on the lens, but I rarely saw this used in aircraft photography. The film-rolling handle was located on the left side of the top of the camera, but most of us removed it and remounted it inverted to create a better grip that allowed faster rolling, not to mention blackened fingers at the end of a long day’s shooting, as the metal on the handle tended to rub off with extended use. The camera had some problems that were never solved. The slightest jar could knock the camera lens out of line, resulting in out-of-focus pictures, and this would not be known until the film was developed, sometimes weeks later. Another problem was the bellows, which tended to dry out and develop light leaks over time. My solution was to leave the camera open all the time and cover the bellows with black electrical tape, which made the camera bulkier to handle. On the other hand, it probably still doesn’t leak today, 30 years after I stopped using it. These cameras were bulky, fragile, and awkward to use. No telephotos were available, and its eight-exposure limit required frequent reloading. But the 616 camera served us well, and I would suspect that most photos of airplanes taken from the late ’20s until at least the late ’60s were taken on 616 film. The 616 camera certainly has played a premier role in the preservation of aviation history.

THE DEMISE OF 616 PHOTOGRAPHY

In the mid-1970s, Kodak stopped the production of 616 film, long after it had manufactured its last 616 camera. This effectively ended 616 aircraft photography in the United States. A few collectors hoarded large quantities of the film, but it was used up rather quickly. I bought about 100 rolls in 1975 and ran out in 1976. Some photographers switched to 120/620 film, but it never replaced 616. Most of us switched to 35 mm color slides, and this is the most common medium for aircraft photography today, although many other formats are also in use. Now we trade 35 mm color slides instead of 616 negatives, but the process is still the same. The advantages of smaller, more technologically sophisticated cameras were significant. Modern cameras have automatic metering, computer chips to adjust light and speed settings, autowind systems, and adaptability for zoom lenses and telephotos, as well as built-in flash units. They are more robust and less easily damaged, and they’re certainly more useful in air-to-air photography. Modern 35 mm cameras are relatively inexpensive, but they are probably on their way out as digital photography takes over the market. Digital photography simplifies the process, and the new equipment available makes aircraft photography much easier and more economical.

TOP: Grumman F8F-1. French, probably Indo China, c. 1948. Unknown. MIDDLE: Northrop YRB-49A. Stored in desert near Muroc, California (now Edwards), early ‘50s. Doug Olson. BOTTOM: Boeibng B-50A at Boeing factory, late ‘40s. Probably Peter Bowers.

PRESERVATION OF THE COLLECTIONS

A major concern associated with 616 aircraft photograph collections involves their preservation and accessibility to future historians. Some negative collections have been donated to museums, historical societies, and university libraries, but most institutions do not have the resources to catalog and print the photos, much less make them available to researchers. A few collectors and their heirs have attempted to sell prints by mail or over the internet, with varying results. Most collections have been sold to other collectors over the years. It’s an old practice, but at least it keeps the material available in some cases. Probably the best place for the collections would be organizations like EAA, which is dedicated to the preservation of aviation history and will probably never go defunct. Another possibility would be a university with an established aviation history department that is heavily involved in research activity and can guarantee that its collections remain accessible to bona fide aviation historians and writers. Although aircraft photography today is highly sophisticated, the originators of the hobby — or art — began in the late ’20s, developed the skills and techniques, and set the standards for modern-day historical preservation. The old negatives are usually of very high quality, and prints can be made easily using a contact printer or digital scanner.

THE PHOTOGRAPHERS

Following is a list of individuals believed to have been active 616 photographers from the late ’20s until the mid-’70s. If anyone can provide more information on this subject, please contact the author through the editor at jbusha@eaa.org.

www.vintageaircraft.org 19

LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHERS BELIEVED TO HAVE BEEN 616 AIRCRAFT PHOTOGRAPHERS AND NEGATIVE TRADERS

Allison, R.H.

Jamestown, New York

Anderson, O.K.

Arlington, Texas

Deigan, Edgar

New York City

Collection to Bob Esposito

Andrews, Harold

Washington, D.C.

Active, 1975

DeMarchi, Italo

Venice, Italy

1950s

Apostolo, Georgio

Italy

1950s

Deschenes, Paul

Sgt. USAF

Dickey, Fred C.

Armstrong, Bob

Sold photos as Airphotos; 1950s

Davidson, Jesse

Later changes to Oakes, 1940-1941

Arnold, Henry

San Diego

1960s

Dickson, Robert L.

Artof, Henry

Brooklyn, New York

Later Los Angeles

Donawwto, Bude

Attwood, Bob

Seattle

Prewar; 1933 IAAPE

Duncan, L.M.

Auerbach, Will Dale

Oakland, California

Boeing School of Aeronautics

Durand, John

Bachmann, A.L.

Newark, New Jersey

Airline mechanic; Eastern?

Bagoff, David

Brooklyn, New York

Prewar

Baker, Brian

Michigan, Arizona (your author)

1951-1976

Eckert, Howard D.

New York City

Prewar; IAAPE

Balogh, William J.

Detroit

WWII pilot; my mentor

Ederr, Bern

Baltimore

Prewar

Bamberger, Fred

New York City

Prewar; IAAPE

Engelhardt, Dean

St. Louis

Banfield, Greg

Sydney, Australia

1960s

Enich, Lee

Los Angeles

Prewar

Esposito, Robert

Somerdale, New Jersey

Works for FAA

Bates, Corbett K.

Oakland, California

Collection to Larkins and Geen, 1940

Asheville, North Carolina

Prewar

Durrenberger, Justin

Brooklyn, New York

Prewar; IAAPE

Dyson, James

Australia

Beer, Art C.

Australia

IAAPE; 1930s

Feist, William R.

Boston

Prewar

Beeukes, L.B.

Baltimore

Prewar

Flax, Eli

New York City

Prewar

Benner, Norman

Philadelphia

Prewar

Franforter, An Freeman, Fred G.

New York City

1940s to 1960s

Brinati, Vincent

New York City

Prewar; known as “Beans”

Fahey, James C.

New York City and Washington, D.C.

Author; prewar

Berlepsch, Lewis E.

New Haven, Connecticut

Fleming, William N.

New Jersey

Prewar

Berry, Peter

England-Scotland

Bennis, Steve

Galloway, Cedric

California

Prewar

Besecker, Roger

Gann, Harry

Phoenix, Los Angeles

Douglas Aircraft Co.

Blanchard, Fred

Geen, Harold

Oakland, California

Collection sold to Olson, 1952

Gelbudas, Anthony

Milwaukee

1950s and 1960s

Bodie, Warren

Haynesville, North Carolina

Border, Marvin J.

Buffalo, New York

Prewar

Goldsmith, Julian R.

Oak Park, Illinois

Prewar

Bowers, Peter M.

Seattle

Author, pilot, designer; EAA, AAHS

Goodhead, George

Tulsa, Oklahoma

Pilot; prewar

Branam, Curtiss

Los Angeles

Prewar

Gradidge, Michael

London

1950s and 1960s; later name change

Brashear, A. Ray

Los Angeles

Prewar

Green, Arthur

Brinsley, Harold(?)

Bronx, New York

Brodsky

Brooklyn, New York

Brown, Ralph I.

Decatur, Illinois

Budoff, Norman

Brooklyn, New York

Bulban, Erwin

New York, Dallas

Prewar

Hamilton, Charles, V.

Miami, Oklahoma

Prewar

Burgess, Bob

St. Louis

1950s and 1960s

Haney, E.C. “Handy”

Dallas, Fort Worth

1950s and 1960s

Prewar

Hardesty, Bergan

Los Angeles

Prewar; IAAPE had World War I photos

Burke, R.S.

Gresham, Deward B.

Alameda, California

1950s

Groffman, Norman

Brooklyn, New York

Prewar

1950s and 1960s

Hafter, Abbott

Brooklyn, New York

Prewar

Hagedorn, Danial

1 Shot with Hiller

Caler, John W.

California?

Restored ME-109G?

Hardman, Joe

Canary, Jack

Oak Park, Illinois

Prewar

Hare, Bob

Carter, Anthony

Australia?

Hasse, J.M.F.

Carter, Dustin

California

Hay, John

Casker, Johnny

New York City

Prewar

Hawkins, Jim

Brooklyn, New York

Prewar; IAAPE

Chvala, J.V.

Chicago

IAAPE; prewar

Heinowitz, Ben H.

Mountainside, New Jersey

Prewar; IAAPE, founder

Clark, Henry

New York and New Jersey

Prewar; flew J-3 on floats

Hiller

Brooklyn, New York

Prewar

Coats, Ed

Tasmania, Raleigh, North Carolina

1950s and 1960s; originally English

Holmquist, Earl

Oakland, California (SFO)

1950s; aircraft mechanic

Cole, Ron

England

Hosley, Mac

New York City

Collins, John

Dallas

Cooke, David

New York City

Hunt, M.C.

La Grange, Illinois

Prewar

Coombs, Logan

Minneapolis

Illing, Richard J.

Lake Mahopac, New York

Prewar

Cooper, Kipp

Los Angeles

Prewar

Irons, Gordon

Vancouver, British Columbia

Prewar

D’Appuzo, Nick

New York City

Homebuilt designer

Jackson, Wally “Tex”

Elizabeth, New Jersey

Prewar

Darby, E.C. “Bunny”

New Zealand

Jacobson, Vernon

Chicago

Prewar

20 July/August 2020

Prewar

1931; prewar; may be Navy Harrison, New York

Huefner, Jack

Jameson, Bud

Los Angeles

Jansson, Clayton

San Francisco

Prewar

Joerns, B.

New York City

Johnson, Chalmers A.

San Francisco

Johnson, David

Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia

1950s and 1960s

Moore, R.O.

Johnson, Gene (R.R.)

Franklin, Pennsylvania

Prewar; also Glendale, California

Morrison, Robert C.

California

Nawrot, R.I.

California

Prewar

Kasulka, Duane

Millerin, Roy

Elyria, Ohio

Prewar

Mitchell, John C.

Los Angeles

Prewar

Modlin, C.T. Jr.

Houston

Moore, E.R./R.R. Ned

Ysleta, Texas

Prewar

Kaczanowicz, John

Massachusetts

Prewar; signed prints “Katzy”

Nieto, Joe

Texas Prewar

Kauer, Donald F.

New York City

Prewar

Niffenegger, Fred Jr.

St. Petersburg, Florida

Prewar

Kaufman, H.C. “Clif”

Baltimore

Prewar

Nolen, Harold

Oakland, California

Prewar

Kelman, Morton B.

New York City

Oakes, Paul*

Salem, Massachusetts

Prewar; was Paul Duschenes

Kemp, Burton

Chicago

1950s

O’Dell, Robert T.

New Jersey

Sold collection to Challenge Publications

King, Phillip C.

Long Beach, California

Prewar

Olmstead Merle

Paradise, California

Master Sgt., 8th AF World War II; author

Prewar

Olson, Douglas D.

San Francisco

Luscombe pilot; 1950s on

Koch, Charles Kohn, Gregory C.

Milwaukee

Leo’s brother

Ostrowski, David

St. Louis

Now in Fairfax, Virginia; used Dave Oster

Kohn, Leo J.

Milwaukee

Gregory’s brother

Palmer, Williams

Los Angeles

Prewar

Parnell, Neville

Sydney, Australia

1960s

Charlotte, North Carolina

Prewar

Kopitzke, Bob Kossack, Charles W.

Chicago

Prewar; IAAPE

Patterson, Reid

Krieger, Adolf “Art”

Chicago

World War II B-24 gunner; later California

Paul, Lionel

Kuhn, Gary

Minneapolis

Shot 620, traded 616; Latin American

Pegdan, Al

Pittsburgh

Prewar; IAAPE

Prewar; killed in World War II

Peltz, Steve

London

1950s and 1960s

Kulick, Harold W. Kuster, Mike

Brooklyn, New York

Prewar; IAAPE

Phillips, Art

Seattle

Prewar

Larkins, William T.

San Francisco

Prewar; founder, AAHS; author

Phillips, Chester W.

Moorehead, Minnesota

Prewar

Phillips, Oliver R.

Seattle

Prewar; IAAPE

Prewar

Pinnell, Bill

Brooklyn, New York

Prewar; IAAPE

Larson, Jim Lavelle, Don

New York City

Leavitt, Robert

Georgia

Shot a few 616s, some color 616s

Pleakis, Dominick

Levy, Howard

Brooklyn, New York

Prewar; shot during World War II

Polk, Irwin

Lippencott, Harvey

Connecticut

Lougheed, Jack

Detroit

Lucabaugh, David W.

Annapolis, Maryland

Prewar Newark, New Jersey

Prewar; IAAPE

Rankin, David A.

Malden, Massachusetts

1950s; MASS-ANG for many years

Ranson, Wilford

Los Angeles

Prewar

Reed, Boardman C.

Pasadena, Chico, California

Prewar

Reisonger, Homer

Cleveland

Prewar Prewar

Price, Arthur Prewar

Lundahl, Eric MacSorley, Frank

D.C. area

Malone, Al

New York City

Air Force

Rice, E.J.

Detroit

Malone, Pete

New York City

Prewar

Ronald, A.M.

Minesing, Ontario

Maloney, Edward

Chino, California

Founder, Planes of Fame Museum

Russell, Dave

New York City

Hartin, Harold G.

New York, Miami

Prewar; Grumman photographer

Salo, Mauno

Martin, R.R.

Sanford, F. Kenneth

Prewar, 1934 Prewar?

Los Angeles

Prewar

Mathews, Leslie

England

Prewar

Roos, Fred

Mayborn, Mitch

Dallas, Fort Worth

Airline pilot?

Sarkis, Pete

New York City

Prewar

Schuler, Charles

Dallas

Prewar

McCallum, LeRoy McCash, Don

Palo Alto, California

Prewar; IAAPE

McCormick, Harold

Detroit, California

USAF; collection to Krieger?

Selikoff, Joe

Brooklyn, New York

Prewar

McClenney, Ferrill

Dallas

Prewar

Shalvoy, C.E.

Los Angeles

Prewar; IAAPE

McCullon, Ed

Long Beach, California

Prewar

Sharp, Walter/Wallace

Oakland, California

Prewar; IAAPE

McLarren, Robert

Los Angeles

Prewar

Sheetz, Charles

McNulty, Jack

Toronto

Prewar

Shertzer, Frank

Oakland, California

Prewar

McRae, Jack

New York City

Prewar; aeronautical engineer

Schmidt, A.U. (Al)

Kansas City, Missouri

Prewar; IAAPE

Meehan, Kenneth

Australia or New Zealand

Scott, Clark

Glendale, California

Prewar; IAAPE

Meese, Edwin

Baltimore

Seeley, R.C. “Carson”

Linthicum, Maryland

1960s

Menard, David W.

Lombard, Illinois

Shipp, Warren D.

New York City

Prewar

Mesko, Jim

Shyrock, E.L. “Ed”

Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania

Prewar; IAAPE

Meyer, D.

Smalley, Lawrence

San Francisco

1950s

USAF; later at AFM; writer

Schureman

www.vintageaircraft.org 21

Smith, George Milton

Florida

Prewar

Sommerich, E.M.

St. Louis

Prewar; career USAF; postwar

Soumouile(?)

Paris

Postwar unknown

Stainer, Brian

England

Postwar

Staines, G.E. “Ed”

Australia

Prewar; IAAPE

Steeneck, William

New York City

Postwar; airline mechanic

Stevens, R.W. “Bob”

Baltimore

Prewar; IAAPE

Stollar, Leonel

Oakland, California

Strasser, Emil

Akron, Ohio

Strnad, Frank

Long Island, New York

Stuart, Cliff

Toronto

Aeroplane Photo Supply

Stuckey, Robert

Minneapolis

Commercial pilot

Sullivan, Jim

East Coast?

Sumney, Kenneth M.

Pittsburgh

Prewar

Sutter, Art

Oakland, California

Prewar

Swanborough, Gordon

England

Swisher, William

Los Angeles

Prewar

Tabio, Ernesto

Havana, Cuba

Prewar; IAAPE

Taylor, Robert L.

Ottumwa, Iowa

Founder, AAA; now Blakesburg, Iowa?

Tenety, James Jr.

Corona, New York

Prewar

Thorell, Henry

Bridgeport, Connecticut

Prewar

Trask, Charles N.

New York City

Career Army

Troop, Peter

Toronto

Collection sold to Olson, 1956

Ulrich, L. Russell

Washington (D.C.?)

Flew LTA in World War II

Underwood, John

Los Angeles

Author, historian; may have shot 616

Van Sickle, B.

Hamilton, Ontario

Prewar; IAAPE

Walker, P.T.

Ashford, Kent, U.K.

Prewar; IAAPE

Walsh, Don

Oakland, California

Prewar; IAAPE

Weaver, Truman Whitmer, Arthur L.

Oakland, California

Prewar; IAAPE

Williams, Gordon S.

Seattle

Prewar; IAAPE; well-known photographer

Williams, Joe

New York City

Prewar

Wilkie, J.S.

Plandome, New York

Prewar

Wiltshire, Norman

Australia

Sydney or Melbourne; 1950s and 1960s

Winkler, Gilbert

Brooklyn, New York

Prewar

Winstead, George

Prewar

Wommack, Jim

North Carolina

Wischnowski, Edgar

Washington, D.C.

Yeager, William F.

Cleveland

Young, Hugh J.T.

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Prewar

Prewar; IAAPE

BRIAN R. BAKER is a retired high school and college history and English instructor. He has a master’s degree in history and started photographing airplanes with a 616 camera in 1951 when he was in junior high school. His has more than 30,000 616 negatives, not to mention a larger collection of color slides and digital photos, all of aircraft. He is also a commercial pilot with instrument and instructor ratings and does tailwheel conversion training. He owned a classic Luscombe 8A Silvaire but recently passed it on to his son, who is an airline pilot. He currently lives in Sun City, Arizona. He is interested in contacting anyone who has any information about the 616 collectors listed in the article, as this project is far from finished.

Note: The photographs that will illustrate this article consist of several black-and-white photos of groups of collectors, a photo of a Kodak Six-16 Monitor camera, and examples of some of the negatives I have in my collection, illustrating the formats required by collectors in the ’30s and ’40s.

22 July/August 2020

TOP: Group of airplane photographers, probably at Dayton, Ohio, Air show, in early ‘50s.Photo from William T. Larkins. MIDDLE: Group of airplane photographers, NSAS Oakland, 1956 (I was there). People are (L-R) W.T. Larkins, Frank Strnad, Dou Olson, Brian Baker, Chalmers Johnson. Unknown. 616 photo sent to me by William T. Larkins. BOTTOM: William T. Larkins, about 25 years ago, taking a photo from the back seat of a Stinson L-5.

C H A R G E D T H E

A L L- E L E C T R I C

F O R F O R D

R E S E R V E N O W AT F O R D . C O M Terms and conditions apply. Preproduction vehicle images simulated. Production models may differ. Available late 2021.

TA K E O F F M U STA N G

M AC H - E

JASON SOMES AND HIS CHAMPION 402 LANCER BY HAL BRYAN

t just looked fun,” said Jason Somes, EAA Lifetime 623505, of Santa Rosa Valley, California, describing his first reaction to seeing a 1963 Champion Lancer 402 for sale on Barnstormers.com. “I mean, it’s just a neat airplane. What can I say?” The Champion Lancer, which was built and sold as an inexpensive multiengine trainer, traces its roots back to Aeronca, manufacturer of classics like the 7-series Champion — always just the Champ to most of us. Aeronca — from Aeronautical Corporation of America — was founded in Ohio in 1928 and started producing the C-2 the following year. During World War II, the company produced a tandem trainer called the Defender, the three-seat TG-5 glider, and the L-3, a light liaison airplane. As the war wound down, the company focused on the civilian market, introducing the

24 July/August 2020

PHOTOGRAPHY BY SCOTT SLOCUM

Champ and the 11-series Chief, which shared a name but little else with one of the company’s prewar designs. The four-seat Sedan came around in 1947. In 1951, after 23 years of producing more than 50 different types, Aeronca got out of the aircraft business and switched its focus to building components for a number of other companies, eventually becoming a division of Magellan Aerospace. That may have been the end, of sorts, for the Aeronca Aircraft Corp., but it wasn’t the end of Aeronca’s aircraft. In 1954, a man named Robert Brown purchased the type certificate for Aeronca’s last Champ, the 7EC, and formed a company called Champion Aircraft Corp. in Osceola, Wisconsin. Champion Aircraft produced a range of aircraft for the next 15 years or so, all of them based to one degree or another on the 7-series, including the Citabria and its derivative, the 8-series Decathlon. Champion was acquired by Bellanca in 1970, and its assets were sold to the American Champion Aircraft Corp. in 1988. www.vintageaircraft.org 25

The front cockpit is equipped with a yoke, while the rear cockpit holds with tandem Aeronca tradition and is equipped with a stick. Also of interest is the “phantom” landing gear switch that does nothing but change the color of the three lights next to it, but added to the airplane’s short-lived utility as a multiengine trainer.

JASON’S JOURNEY

“I started building plastic models as a young child, as most do,” Jason said. “I started building planes probably aged 7 or something — plastic models. And then I started finding a way to put motors in them — power-driven, World War II fighters — and putting motors in the propellers, which were [only] moderately successful but gave me something to do.” When he was a teenager, he started flying radio-controlled models, and that led him to a fateful encounter. “I met a guy at the model field at age 16; he was a United Airlines pilot,” Jason said. “And he took me under his wing to come out to his hangar, clean airplanes, do odd projects in trade for learning to fly. He offered me either money, which I … didn’t really need … or to learn to fly. So I think I worked like 16 hours for every hour of flying time.” Jason’s first 25 hours or so of dual with that pilot, whose name is Dan Gray, were in an airplane that most people wouldn’t think of as a primary trainer — a Pitts S-2B. “Yeah, it was the first airplane I took off [in], the first airplane I landed,” he said. “On my first flight I did a roll, my second flight I did a loop. … There was no ball in the Pitts, so you just get your body used to what feels right and what doesn’t feel right.” When it came time to solo, and then finish his private, he transitioned to a much more traditional trainer, a Cessna 150. You would think that the transition from a hot rod like the Pitts to the gentle and forgiving 150 would have been easy, but it wasn’t at first.

26 July/August 2020

“As I was going down the runway in this 150 my first time, the nose was darting back and forth,” he said. “In the Pitts I would always dance on the rudder pedals, right? But keep it straight. … Dan says [to] stop the airplane. He goes, ‘Now put your feet on the floor and push the throttle forward.’ I’m like, ‘You’re kidding me.’ He says, ‘No, just do it.’ And we locked heads a little bit, but basically he said, ‘Look, you don’t need to be working the rudder like you do on the Pitts.’” Jason has fond memories of those early days. “Dan was a good instructor, a lot of aircraft experience, a lot of teaching in Pitts,” he said. “He was just a great mentor of mine growing up, and he just retired out of United actually three or four months ago as a 787 captain.” When Jason told Dan that he wanted to be a pilot, Dan’s advice was as insightful and unconventional as the idea of giving Jason his first dual in the Pitts. “He goes, ‘Look, everyone wants to be a pilot,’” Jason said. “He goes, ‘Here’s what I suggest you do. Go get your maintenance, go get your A&P. Because you can always get your further ratings.’ And I did that, and it wound up being probably the best career advice ever for me.” By the time he turned 20, Jason had finished his A&P mechanic certificate and gotten a job at a corporate flight department working on a Falcon 50 and a Gulfstream III in Venice, California. That same year, while many of his peers would have been studying in college and racking up student loan debt, Jason bought a house — not an easy thing to afford in Southern California. He rented rooms out to some local flight instructors who were doing their best to build time.

PHOTOGRAPHY PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY BY SCOTT OF RON SLOCUM PRICE

“It’s funny, those original few guys that were renting from me are still my friends, and they chose airline careers, and I’ve been watching their struggles and furloughs and whatnot through the years,” he said. “They’re all doing very well, don’t get me wrong. But at age 20, I was doing I’d say fairly well as a mechanic, and they were struggling trying to cut their teeth in aviation as far as the flying side goes.” Over the years, Jason continued to build up his certificates and ratings on his own timetable, and then he got the chance to transition from the maintenance side of corporate aviation to the pilot side. “And now I’m just doing the corporate flying thing,” he said. “I fly a Gulfstream 650 for a very prominent Southern California-based company, and it gives me a lot of free time to do my hobbies and activities. … It’s a nice, challenging airplane to fly, and I work with some great people and fly some great people around. So I’m very fortunate.” Obviously, Jason flies for fun, too.

“If I’m going to go on a trip, and if I know I’m going to be away for a week or two, I try to fly all my airplanes before I go. And then when I get home, I do it again,” he said. “I actually fly less when I’m working than when I’m at home.” All of his airplanes? Yes, Jason has an interesting and enviable fleet. He owns, either outright or as part of a partnership, a Pitts S-2C, a Cessna 150, an A36 Bonanza, an L-29 Delfin, a MiG-17, and a WWII-era Schweizer TG-2 that’s currently on loan to a museum. Speaking of museums, Jason also flies as a wing leader for the Southern California Wing of the Commemorative Air Force and its associated WWII Aviation Museum. The organization has 13 flyable airplanes, and Jason gets to fly all of them. His pilot certificate is sprinkled with authorizations to fly Bearcats, Zeros, Mustangs, Spitfires, you name it. But the airplane that most recently captured his attention was the Lancer.

“I pulled the airplane out to fly it one day and my airplanes were all stacked in my hangar, and everything I own is single-engine other than the Lancer. And this gentleman comes up to me and says, ‘You know, that airplane won’t maintain altitude … if you lose an engine.’ I turned to him and said, ‘Nor will anything else in my hangar.’”

www.vintageaircraft.org 27

ATTENTION-GETTER

The Lancer was arguably the second-most unusual airplane produced by Champion Aircraft during its heyday (see the sidebar for the aircraft that gets the first-place nod.) The prototype, which first flew in 1961, was an outgrowth of the company’s 7FC Tri-Traveler, essentially a tricycle-gear version of the Champ. While the prototype used two Continental C95s, the production versions were equipped with a pair of 100-hp O-200s mounted in nacelles on the upper surface of the wing. The main gear is mounted directly under the nacelles, making the airplane look a bit like a baby Britten-Norman Islander. The Lancer was built using traditional steel tube and fabric construction, and when it was introduced in 1963, the retail price was $12,500. That works out to a bit more than $100,000 today, which seems like a huge number until you remember that it’s equivalent to the price of an upper-midrange LSA. The Lancer was targeted at flight schools that were looking to help train a generation of airline pilots, and its major competitor at the time was the more complex — and, yes, more capable — Piper Apache. The Apache was also more expensive by far, selling new in 1962 for $45,000, or more than $385,000 in today’s dollars. One of the most interesting things about the airplane aside from its overall rarity is what you find in the cockpit. To make the airplane more valuable as a trainer, Champion introduced what Budd Davisson aptly referred to, in a piece about the type he wrote for EAA almost a quarter century ago, as “phantom controls.” (“Champion Lancer,” EAA Sport Aviation, November 1995.)

The first of these is a gear switch. That’s not normally an odd thing to find in a light twin, but in the case of the fixed-gear Lancer, it does absolutely nothing. Well, almost nothing. “You take the switch and put it up, and the lights go out; put the switch down, the lights come on,” Jason said. “It’s a complete training aid.” As quirky as it seems, it would certainly build up some muscle memory, and it’s arguably no weirder than airline pilots practicing their flow using laminated posters of their instrument and control panels. While Jason’s doesn’t, some Lancers also included dummy prop levers for the same reason, even though all of them use fixed-pitch propellers. Even the flight controls themselves are unusual. “It’s a unique airplane in that the rear seat has a stick like the Citabria or Champ or Decathlon would,” he said. “[But] the front seat has a yoke.” There is some debate when it comes to the total number of Lancers built, but many sources suggest that the final number was 26. Of these, nine are still registered in the United States, and Jason knows of maybe three that are flyable. It’s likely that Champion had higher expectations for the airplane, but in spite of the “phantom controls,” the FAA eventually frowned on the airplane’s limitations. In the year and a half or so that he’s owned the airplane, Jason has met several people who got their multiengine rating in Lancers, but that all happened in a fairly narrow period of time. According to Jason, the large exhausts on the upper surface of the wing make the O-200s sound like IO-550s.

28 July/August 2020

PHOTOGRAPHY BY SCOTT SLOCUM

“Then the FAA … said, ‘Wait a second, you’re giving a multiengine rating to a guy, you can’t feather the engines, you can’t raise the landing gear, yeah. Maybe not,’” Jason said. “Because the guy is going to go out on a 421 or a King Air and go hurt himself.” It wasn’t long before the FAA put a limitation on the airplane that effectively killed its viability as a multiengine trainer. “If you get your rating in a Lancer,” Jason said, “it’s only good for the Lancer. … Not a single flight school wanted it after that, so I assume they sold off to personal collections and that’s it.” Jason’s airplane ended up in the collection of the Mid America Flight Museum in Mount Pleasant, Texas, and he bought it from the organization about 18 months ago. “When I bought the airplane from the museum, they go, ‘Yeah, this airplane gets more attention than our P-51 Mustang does,’” he said. “And I’ll tell you it’s true, because I fly our P-51 and our other fighters here at the museum. When you fly that airplane, the Lancer, the curiosity is huge. And when you land at airports, like these where we’re fuel-stopping and coming back, you get the most interesting people coming out. … It’s interesting, most people that come up that don’t know what it is think it’s a seaplane. I get that all the time. They all think it’s amphibious. I think the only way to make that airplane perform worse would be to make it amphibious.”

PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY OF HAL BRYAN

The Champion 7JC Tri-Con

ANOTHER RARITY While working on this story, we came across another uncommon descendant of the Champ: the 7JC Tri-Con. Overall, the airplane looks like a typical 7-series Champ until you get to the landing gear. It’s a sort of reverse tricycle configuration, as if you took a Tri-Traveler and started nudging the nose wheel back toward the tail, then changed your mind and stopped halfway. Twenty-five of them were reportedly built, and the type certificate specifically spells out that the airplane could be converted to a 7EC taildragger. There are two currently listed in the FAA database, one in Texas and one in Illinois, both registered to corporate entities. A third one, described as complete but not legally airworthy, sold at auction in 2017, but it was deregistered in 2018, as was, coincidentally, the example in the photo above. If anyone out there knows more about any surviving 7JCs, we’d love to hear from you. Drop us a line at editorial@eaa.org.

www.vintageaircraft.org 29

Like its more traditional predecessors, the Lancer was a simple and straightforward design, built as a creative alternative to more costly multiengine trainers.

JUST FLYING AROUND