120/140 CONVENTION PHOTOS

GERONIMO APACHE

CESSNA 150 FUN

JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2025

120/140 CONVENTION PHOTOS

GERONIMO APACHE

CESSNA 150 FUN

JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2025

VAA PRESIDENT JOHN HOFMANN

ON OCTOBER 18, I was elected to succeed Susan Dusenbury as president of the Vintage Aircraft Association upon her retirement date of January 1, 2025. I want to thank Susan for her leadership since becoming president in February 2017. Under her guidance, VAA has become financially stable, with infrastructure improvements around our Vintage Village at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh, including improvements in the VAA Red Barn, the Vintage Bookstore, and the Tall Pines Café. This culminated with the construction of the Charles W. Harris Youth Aviation Center, which opened during AirVenture 2024. Thank you, Susan, for all you have done.

My background is in aviation maintenance and restoration and the nonprofit association world. As a child in the 1970s, I started with plastic models and radio-controlled airplanes. I progressed to flying lessons in an Aeronca Champ and finished my private pilot certificate at age 18 in a Cessna 172. Along the way, I became an EAA member in 1982 and a VAA member in 1988.

I moved to Indiana in 1990 and sought an EAA chapter to join. I found EAA Chapter 226, from the Anderson and Muncie area. This group of enthusiasts was, and still is, active in building and restoring aircraft. I eventually became secretary and then president of this group. There, I started my first project, a Taylorcraft L-2, and went to A&P mechanic school in Indianapolis. When school was finished, I worked

as a technical writer for RollsRoyce Jet Engines (Allison Engine Co.). I mainly worked with T-56 engines and the V-22 Osprey, where I was responsible for the aircraft’s first engine operations manual.

The friendships fostered through these airplanes are invaluable, often more meaningful than the aircraft themselves. They serve as a common bond among great friends.

After moving to Milwaukee in 1997, I worked for Ken Cook Co. During this time, I wrote manuals and handled marketing for Beechcraft and several boat companies. I also enjoyed being on the editing team for Duane Cole’s final book, Airport Memories. Duane was a gentleman, and I treasured our conversations.

The year 2002 marked a career change when I transitioned from technical writing to association management. Over the next 20 years, I learned a great deal about nonprofit and membership association retention, governance, financial management, and executive

CONTINUED ON PAGE 64

January/February 2025

Publisher: Jack J. Pelton, EAA CEO and Chairman of the Board

Vice President of Publications, Membership Services, Retail, and Facilities/Editor in Chief: Jim Busha / jbusha@eaa.org

Senior Copy Editor: Colleen Walsh

Copy Editors: Tom Breuer, Jennifer Knaack

Proofreader: Tara Bann

Print Production Team Lead: Marie Rayome-Gill

Senior Sales and Advertising Executive: Sue Anderson / sanderson@eaa.org

Mailing Address: VAA, P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903

Website: EAAVintage.org

Email: vintageaircraft@eaa.org

Phone: 800-564-6322

Visit EAAVintage.org for the latest information and news.

Current EAA members may join the Vintage Aircraft Association and receive Vintage Airplane magazine for an additional $45/year.

EAA membership, Vintage Airplane magazine, and one-year membership in the EAA Vintage Aircraft Association are available for $55 per year (Sport Aviation magazine not included). (Add $7 for International Postage.)

Please submit your remittance with a check or draft drawn on a United States bank payable in United States dollars. Add required foreign postage amount for each membership.

Membership Service

P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903-3086 Monday–Friday, 8 AM—6 PM CST Join/Renew 800-564-6322 membership@eaa.org

EAA AirVenture Oshkosh www.EAA.org/AirVenture 888-322-4636

Nominate your favorite vintage aviator for the EAA Vintage Aircraft Association Hall of Fame. A great honor could be bestowed upon that man or woman working next to you on your airplane, sitting next to you in the chapter meeting, or walking next to you at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh. Think about the people in your circle of aviation friends: the mechanic, historian, photographer, or pilot who has shared innumerable tips with you and with many others. They could be the next VAA Hall of Fame inductee — but only if they are nominated. The person you nominate can be a citizen of any country and may be living or deceased; their involvement in vintage aviation must have occurred between 1950 and the present day. Their contribution can be in the areas of flying, design, mechanical or aerodynamic developments, administration, writing, some other vital and relevant field, or any combination of fields that support aviation. The person you nominate must be or have been a member of the Vintage Aircraft Association or the Antique/ Classic Division of EAA, and preference is given to those whose actions have contributed to the VAA in some way, perhaps as a volunteer, a restorer who shares his expertise with others, a writer, a photographer, or a pilot sharing stories, preserving aviation history, and encouraging new pilots and enthusiasts.

To nominate someone is easy. It just takes a little time and a little reminiscing on your part.

• Think of a person; think of their contributions to vintage aviation.

• Write those contributions in the various categories of the nomination form.

• Write a simple letter highlighting these attributes and contributions. Make copies of newspaper or magazine articles that may substantiate your view.

• If at all possible, have another individual (or more) complete a form or write a letter about this person, confirming why the person is a good candidate for induction.

We would like to take this opportunity to mention that if you have nominated someone for the VAA Hall of Fame, nominations for the honor are kept on file for three years, after which the nomination must be resubmitted.

Mail nominating materials to:

VAA Hall of Fame, c/o Amy Lemke

VAA

P.O. Box 3086

Oshkosh, WI 54903

Email: alemke@eaa.org

Find the nomination form at EAAVintage.org, or call the VAA office for a copy (920-426-6110), or on your own sheet of paper, simply include the following information:

• Date submitted.

• Name of person nominated.

• Address and phone number of nominee.

• Email address of nominee.

• Date of birth of nominee. If deceased, date of death.

• Name and relationship of nominee’s closest living relative.

• Address and phone of nominee’s closest living relative.

• VAA and EAA number, if known. (Nominee must have been or is a VAA member.)

• Time span (dates) of the nominee’s contributions to vintage aviation. (Must be between 1950 to present day.)

• Area(s) of contributions to aviation.

• Describe the event(s) or nature of activities the nominee has undertaken in aviation to be worthy of induction into the VAA Hall of Fame.

• Describe achievements the nominee has made in other related fields in aviation.

• Has the nominee already been honored for their involvement in aviation and/or the contribution you are stating in this petition? If yes, please explain the nature of the honor and/or award the nominee has received.

• Any additional supporting information.

• Submitter’s address and phone number, plus email address.

• Include any supporting material with your petition.

For one week every year a temporary city of about 50,000 people is created in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, on the grounds of Wittman Regional Airport. We call the temporary city EAA AirVenture Oshkosh. During this one week, EAA and our communities, including the Vintage Aircraft Association, host more than 600,000 pilots and aviation enthusiasts along with their families and friends.

As a dedicated member of the Vintage Aircraft Association, you most certainly understand the impact of the programs supported by Vintage and hosted at Vintage Village and along the Vintage flightline during EAA AirVenture Oshkosh every year. The Vintage flightline is 1.3 miles long and is annually filled with more than 1,100 magnificent vintage airplanes. At the very heart of the Vintage experience at AirVenture is Vintage Village and our flagship building, the Red Barn.

Vintage Village, and in particular the Red Barn, is a charming place at Wittman Regional Airport during AirVenture. It is a destination where friends old and new meet for those great times we are so familiar with in our close world of vintage aviation. It’s energizing and relaxing at the same time. It’s our own field of dreams!

The Vintage area is the fun place to be. There is no place like it at AirVenture. Where else could someone get such a close look at some of the most magnificent and rare vintage airplanes on Earth? That is

just astounding when you think about it. It is on the Vintage flightline where you can admire the one and only remaining low-wing Stinson TriMotor, the only two restored and flying Howard 500s, and one of the few airworthy Stinson SR-5s in existence. And then there is the “fun and affordable” aircraft display, not only in front of the Red Barn but along the entire Vintage flightline. Fun and affordable says it all. That’s where you can get the greatest “bang for your buck” in our world of vintage airplanes!

For us to continue to support this wonderful place, we ask you to assist us with a financial contribution to the Friends of the Red Barn. For the Vintage Aircraft Association, this is the only major annual fundraiser and it is vital to keeping the Vintage field of dreams alive and vibrant. We cannot do it without your support.

Your personal contribution plays an indispensable and significant role in providing the best experience possible for every visitor to Vintage during AirVenture.

Contribute online at EAAVintage.org. Or, you may make your check payable to the Friends of the Red Barn and mail to Friends of the Red Barn, P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903-3086.

Be a Friend of the Red Barn this year! The Vintage Aircraft Association is a nonprofit501(c)(3), so your contribution to this fund is tax deductible to the extent allowed by law.

Looking forward to a great AirVenture 2025!

ROBERT G. LOCK

BY ROBERT G. LOCK

A COMMON METHOD TO fair the leading edge of a wood wing is to nail aluminum that has been formed to wrap around the area. Many old airplanes used a soft aluminum, probably what is now 5052, but many restorers use heat-treated 2024-T3 for the leading edge. It is best to install aluminum in sections rather than in one piece because when rigging wings, particularly on a biplane, the wires will cause spars of upper wings to bend down slightly, and a one-piece leading edge will wrinkle. Installing sections allows the skin to telescope very slightly when the spar bends.

Leading edges are typically installed using nails; however, a few ships used countersunk brass screws. I hand bend the aluminum skin by rolling it over on itself and, using a padded 1-by-4-inch piece of wood, press down until the proper shape has been set. Then I scrub the aluminum with phosphoric acid and a scrubbing pad (such as Scotch-Brite) and rinse with tap water to remove all traces of acid. Then the aluminum is treated with chromic acid (Alodine) until the aluminum has a slightly yellow sheen, and then the aluminum skin is flushed with water. When the parts have sufficiently dried, I prime the aluminum with a good grade of epoxy primer. Now the skin is ready to install.

Wrap the skin around the leading edge and mark rib locations with a soft pencil or waterbased marking pen (don’t use red). Next, wrap the aluminum and hold it in place with rubber tension straps. The aluminum skin should fit tightly on the ribs with no gaps due to poor fit. The aluminum is simply an extension of the rib profile and is there to protect the leading edge wood against abrasion.

Figure 1 shows the installation of leading edge metal on a Hatz biplane wing. Note that the skin is nailed to filler blocks glued to the spar between ribs and is nailed to each rib. Use cement-coated barbed steel wire nails for this task, as barbless nails will tend to vibrate out during flight operations. When this job is finished, cover all nail heads with a good grade of tape. I like to use gaffer’s tape because it has good adhesion and is thinner than other types of tapes. Some mechanics use sports adhesive tape, and that too is okay. Just make sure that solvents from the covering material will not loosen the adhesion on the tape.

Figure 2 shows the repaired Hatz wing ready for taping using gaffer’s tape before covering begins. This wing was covered with the Poly

Fiber process. The large mahogany gussets on the upper and lower cap strips were necessary because of cap strip splices when all leading edge ribs were replaced.

Figure 3 shows the Hatz wing with the first coat of Poly-Brush applied, rib lacing completed, and surface tapes installed, with one brush coat on the tapes. Taping was done to match the right upper wing. After Poly-Brush and Poly-Spray buildup, the wing was top-coated with Aero-Thane polyurethane enamel paint.

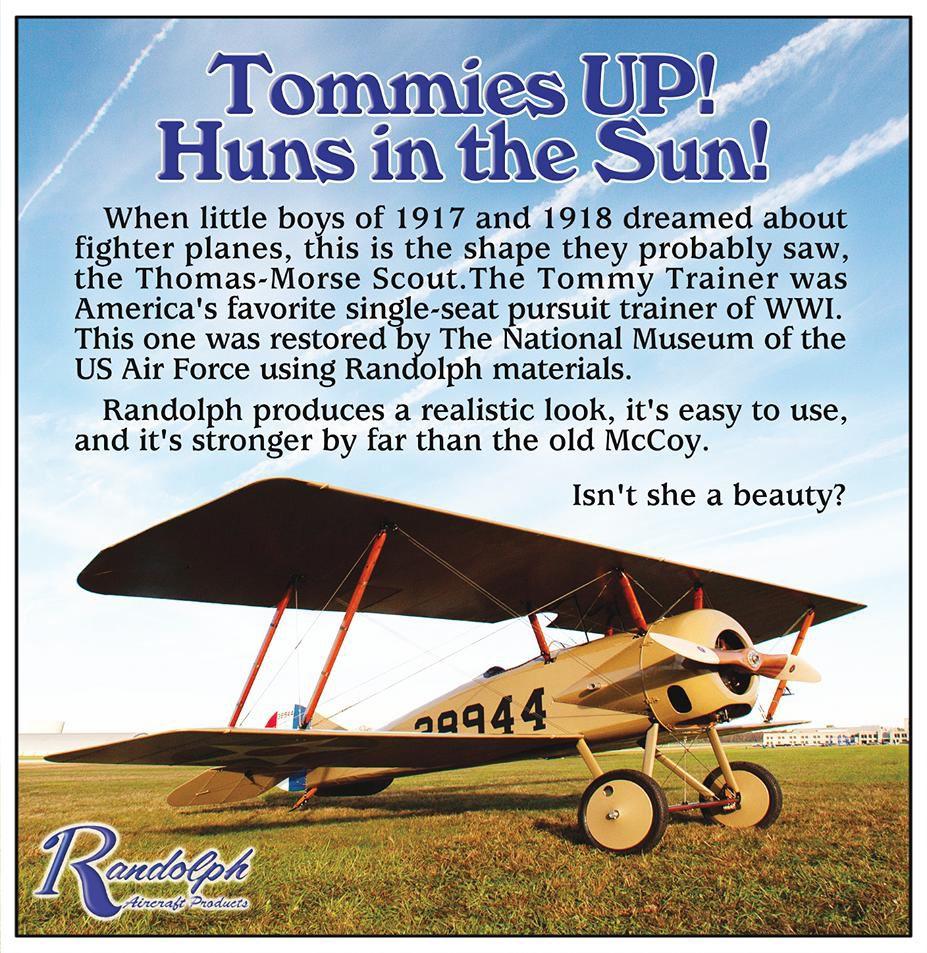

Take a quick look through history by enjoying images pulled from publications past.

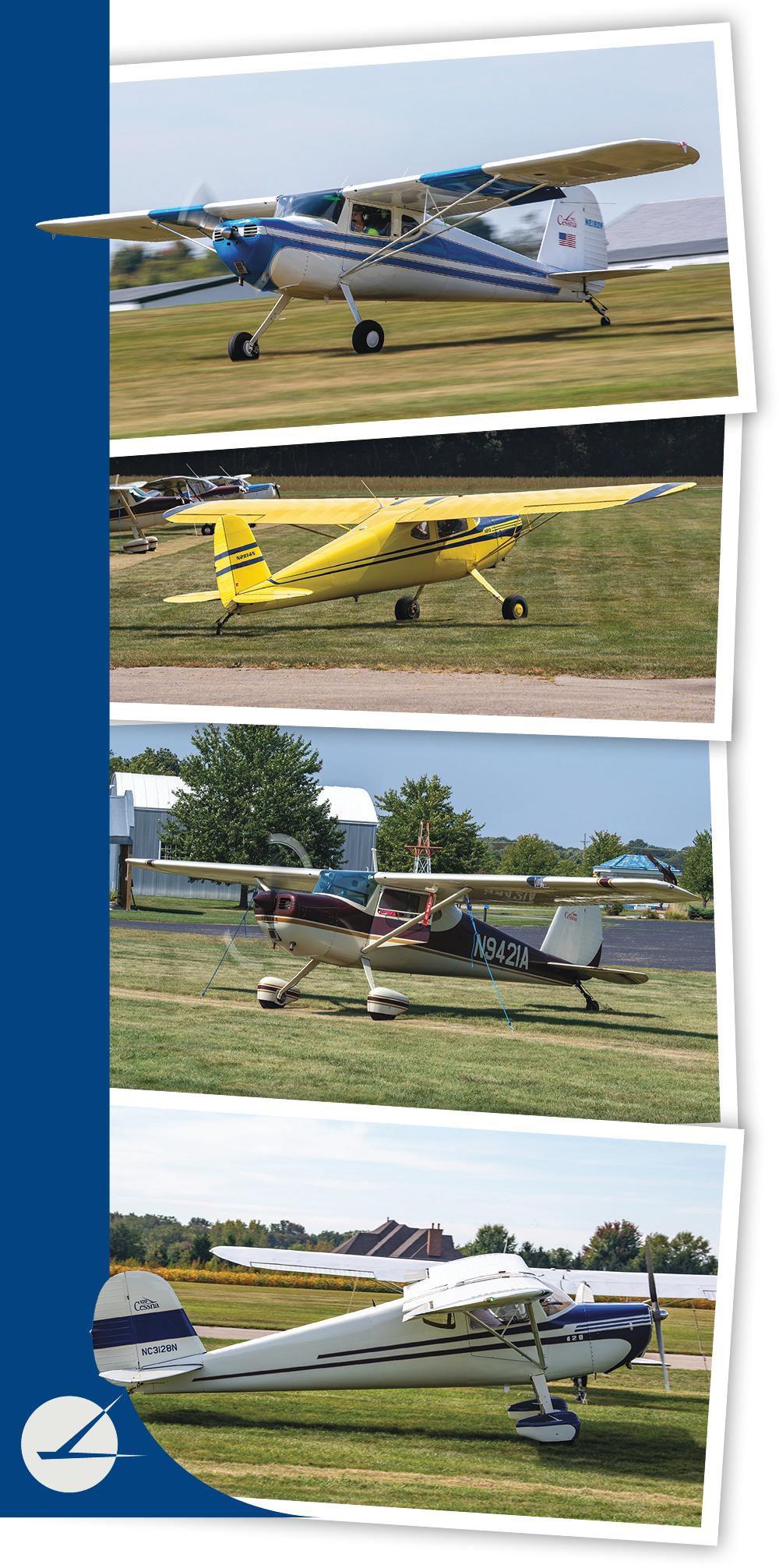

ON AN UNSEASONABLY WARM and sunny mid-September weekend at the general aviation paradise known as Poplar Grove Airport (C77) in northern Illinois, about 150 people and 60 airplanes gathered for the annual Cessna 120/140 Convention. Hosted by the Cessna 120-140 Association, the 2024 convention was largely organized by Ken Morris, EAA Lifetime 58044/Vintage 11423, and Lorraine Morris, EAA Lifetime 1136221, longtime figures and restorers in the vintage aircraft community and residents at Poplar Grove.

As one of the more popular light general aviation aircraft that hit the market shortly after World War II, the Cessna 120 and 140 still have a strong following and dedicated group of pilots who enjoy the type for its simplicity, economy, and flying characteristics. Produced at the same time by Cessna, beginning in 1946 and lasting until 1951, the 120 and 140 are nearly identical. The 120 was designed as a more affordable version of the 140, with no flaps or rear cabin windows. The type kick-started Cessna’s transition postwar to its civil aviation product line and eventually led to the development of the tricycle-gear Cessna 150. Meet some of the pilots who brought their classic Cessnas to the Upper Midwest for socializing, camaraderie, and maybe to learn a thing or two about their airplane.

Ken’s 140A, N5669C, has been in the family since 1968, when his dad bought it. After Ken graduated college, his dad gave the airplane to him as a gift, and it’s served him well since, with his son, two nephews, and a couple of other student pilots learning to fly in it. In 1995, Ken restored the airplane. In 2023, after his father passed, Ken cleaned up the airplane, and Lorraine installed the original seats to bring it back to semioriginal condition. The airplane earned a Bronze Lindy at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2023.

“You’re not super fast, but you’re faster than a car, and it’s a great trainer.” — Lorraine Morris

“In 1968, I was 13. So I was chasing horses around past here with a bucket of oats,” Ken said. “Then I got a motorcycle, and I found out that I didn’t have to chase them around with a bucket of oats and discovered girls at the same time. So I didn’t really even know anything, or care about flying too much. My dad got the airplane and one thing led to another, and it became a passion later on because I found out I could do it.”

Lorraine took on the brunt of organizing the fly-in, from coordinating with Poplar Grove Airport to arranging a block of rooms at a hotel in nearby Rockford and everything in between. She’s been involved with the Cessna 120-140 Association since 1995.

“The nice thing about the 140 is it doesn’t do anything great, but does everything pretty well,” Lorraine said. “You can still go long distances in it in an enclosed cockpit. You look cool when you show up. You get pretty good gas mileage. You’re not super fast, but you’re faster than a car, and it’s a great trainer.”

With the type approaching its 80th birthday, Lorraine pointed out that she thinks the type club has certainly helped in maintaining a vibrant community and keeping 120s and 140s flying.

“This type club is one of the more active small airplane type clubs,” she said. “We have maintenance advisers that you can call up if you have a question. We have a whole online resource

area for people to get old newsletters where we have all this technical data. We have our own reference manual, how to rig a wing, how to do this, all the parts when an AD comes due, here’s what you do. We have a whole reference manual that we sell. So not only is it camaraderie in making sure everybody can get a lot of social stuff, but we make sure that the airplanes are maintained.”

Lorraine flies N5669C as well. With the airplane having been owned by the Morris family for nearly 60 years, it’s become more than just a vehicle.

“It’s part of the family,” she said. “It has a name; kind of uninspiring because it’s Charlie, because [the N-number] ends in C. … It’s basic VFR. You don’t have an attitude indicator; you don’t have a directional gyro. You have a wet compass, which is floaty and weird. So to be able to get a private license, you’re basically partial handling all the time. It’s pretty impressive. Just the fact that you’ve had it that long, it becomes personal.”

The current president of the Cessna 120-140 Association, Roy Aycock, EAA 582609/Vintage 728056, traces his involvement with the type club to his search for a 120 originally donated by Dwayne Wallace, Clyde Cessna’s nephew, to Cessna employees to form the Cessna Employee Flying Club in 1946. A friend of Roy contacted the widow of Mort Brown, a legendary Cessna test pilot, who posted in the association’s forum. Dennis Kelly of Creve Coeur Airport in Missouri posted in the forum that he owned one of the airplanes, and Roy soon struck up a relationship with Dennis.

“Eventually Dennis decided he wanted to sell it,” Roy explained. “A friend of mine and I argued over who was going to buy it, and then we finally

decided to start a partnership. But we definitely wanted to get this airplane back to Wichita [Kansas], and Dennis really wanted the Cessna guys to have the airplane back. We didn’t put it in the [employee flying] club because, as I say, it’s too old for young children. … Greg Anderson, my partner and I, that’s how we wound up with it.”

Roy’s day job is managing the Textron Employee Flying Club in Wichita. When the weather is good, he’ll sometimes fly his 120 to work from the grass strip on which he lives, southwest of Wichita.

“It be-bops around on the grass strips and the fly-ins close [by], but I haven’t had it this far from home in, well, forever,” Roy said. “I brought it up here to do some updates to the horizontal [stabilizer] and spend some time with Ken and Lorraine, and just tweak some stuff, because obviously they’re the gurus and they have the massive stash of parts up here. All those little things, if you don’t kind of take care of them as you go along, pretty soon your airplane’s, well, not in that great of shape. Right?”

Along those lines, Roy pointed to the value of not only the 120-140 Association for owners of those types, but type clubs in general for any airplane owner.

“You’ve got that community, and the people that really know the airplanes and have the stash of parts,” he said. “That’s what I tell everyone, regardless of what airplane you buy, you’ve got to get in the type club and generate those relationships. Or how are you going to afford to keep your airplane and keep it airworthy if you’re not working with the people that know so much more than you do, and have the old stash of parts that you’re not going to find anywhere?”

While Roy’s personal connection to N89777 is part of the draw for him, the

“The simple, intelligent design of these airplanes is wonderful, easy to work on, easy to maintain, just great.” — Roy Aycock

120 is the perfect airplane for him for many reasons.

“You never forget your first love,” Roy said. “A lot of people, they’re [120s and 140s] a starter airplane, honestly. I mean it’s so hard to afford so many things. But this, I think for years, has been an airplane that people can get into. Then once you just have an affection for that first airplane, and they’re simple and they’re easy to work on, and there’s lots of parts [available], and obviously there’s a great community. … When I worked on different airplanes and you look at different things, just the simple, intelligent design of these airplanes is wonderful, easy to work on, easy to maintain, just great.”

When Kaitlin Mroz began looking for an airplane of her own more than a decade ago, she was in her mid-20s and needed something that was reliable and inexpensive to operate. The Cessna 120 checked all of the boxes. Unfortunately, shortly after purchasing her airplane, she needed to perform more repairs than she was anticipating.

“I had a prebuy done, and apparently it wasn’t great,” she said. “I was working with Bill Goebel, and we found a couple loose rivets on the gearbox, so he took them off to replace them. It turns out the gearbox was cracked; turns out a number of other things were cracked. It ended up being five new skins. The engine wasn’t making power, so we ended up going with an O-200. Instrument panel had cracks in it and separation from the structure; that ended up getting replaced. Tail wheel had a broken spring at some point, and you could see damage on the other underside of the skin. … Just about everything.”

While performing the repairs, Kaitlin decided to modernize N72338 to make it more practical for today’s

flight environment, as she does a lot of introduction flights and flight instruction in the airplane. She estimates the project is about 70 percent complete. While Kaitlin didn’t expect some of the expenses associated with repairing and modernizing her 120, she was able to get her A&P mechanic certificate in the midst of everything, and in the end, the airplane is still an affordable way to fly.

“It’s cheap. It’s awesome,” she said. “You can load up; it’s a quick run-up. … You go up and fly. It’s about 20, 25 bucks an hour in gas, and anyone can buy it. It’s a perfect trainer. It’s like a 150. But it’s easy to pull it out of the hangar, and preflight doesn’t take as long as something complex.”

Keith Vanlierop, EAA 1009558/Vintage 732098, is relatively new to the 120/140 community, having purchased his 140 a little more than a year ago. As someone who flies for a living, Keith acquired his 140 to serve as a major change of pace.

“I’m an airline guy, and so I spend all week going all over the country. I kind of like being somewhere 500 feet or less off the ground,” Keith said. “I was looking for something twoseat, low and slow. The nice thing about these is you can actually get up and go someplace too because it’s got the endurance and fuel capacity. The 140 was kind of on my

short list, and this one came up for sale, a friend of a friend, and it was just too good of a deal to pass up because it’s in real nice shape.”

In his year-plus of ownership, Keith, who lives between Cincinnati and Louisville in Madison, Indiana, has definitely not regretted his decision to jump into buying an airplane, specifically his 1948 140, despite some initial reservations.

“I spent a lot of time renting and in flying clubs and stuff like that before this airplane came on the market, and I was like, ‘Well, I should buy that,’” he said. “I was like, ‘Man, aircraft ownership.

I don’t know what that’s going to be like. I don’t know if it’s going to be super expensive. I don’t know anything about this.’ This airplane is so simple, it’s actually really easy. It’s actually been really fun. Any time something came up [with the airplane], I’ve got a good group of people around, and everybody’s super helpful and it’s been really cool. It’s been really cool to have an airplane to go just around a local area. That’s pretty much my whole thing, is on a nice night in the summer, it’s just nice to get up and go do some landings at the grass strip 5 miles away and stuff like that.”

Like many of his fellow 120/140 comrades, Keith lauded the affordability of both flying and maintaining his airplane.

“I’m sure I burned less than 5 gallons an hour for three hours coming up here today,” he said. “So about 100 miles an hour on less than 5 gallons an hour. Pretty hard to beat that. Maintenance and stuff, it’s a C85 Continental [engine] and pretty easy to work on. The biggest thing this airplane needs right now is it needs fabric on the wings

On a nice night in the summer, it’s just nice to get up and go do some landings at the grass strip 5 miles away and stuff like that.

— Keith Vanlierop

eventually, but that kind of stuff, every airplane will have stuff like that that’ll come up. Everything on this airplane is just pretty inexpensive, and [if you] find a good mechanic, you wind up doing a lot of stuff under his supervision. Pretty affordable.”

Terri Hull, EAA 344822/Vintage 722983, has owned her Cessna 140, N77161, for more than half her life, purchasing the airplane back in November 1991. While Terri has flown the airplane all over the country, including to the Dakotas and Texas, she currently bases it at the Love’s Landing airpark in Florida.

Terri began flight instructing in 1990 at Lakefield Airport in Celina, Ohio. She had been looking specifically for a 140 to buy when one came up for sale, owned by the airport’s former manager, Terry Zimmerman. After coming to a deal, Terri made the promise she’d sell it back to him whenever she reaches that stage in her ownership.

“I said, ‘If you sell it to me, I’ll give you first dibs if I decide to sell it,’” she explained. “I bought it from him in November ’91 and have had it ever since. He’s still waiting for me to sell

it to him. We stay in touch; we’re good friends.”

In her 19th year flying professionally for NetJets, Terri, who also owns an RV-6, said her 140 holds a special place in her heart when it comes to just enjoying flying for the sake of flying, though it can get you places as well.

“This series of airplanes is just a wonderful low-and-slow airplane, but it’s not as slow as some; it’s not as slow as the Cubs and the Champs and things like that,” she said. “This thing kind of scoots along, relatively speaking, about 110, 115 miles an hour. It gets me where I want to go, but I have time to look around. I’m not in a rush. The RV is a wonderful machine. I can get up north and back down much more quickly, obviously. … I’ve got my slow one; I’ve got my fast one. Scratch both of those itches and stuff. This thing is economical, for one thing; this is as basic as you can get.”

“Let’s see if I hit Dayton about noon, then steer say 310, I should make Chicago at about two-thirty Plenty of time to take my nap and still take in the Cubs game.”

Early on, Ohio was a big aviation state: the Wright Brothers, John Glenn, Eddie Rickenbacker, Dominic Gentile, and of course General Barnett Overbite, USAF, Retired, shown here planning a cross country early in his career.

Very late in his illustrious career he wandered into the unattended cockpit of a Boeing 737, sat in the right seat, pushed the gear lever up, and proclaimed most assertively “Bombs away!” By design, only the nose gear came up, causing panic, screaming, and a mad scramble for the doors. General Overbite was then gently escorted to some nice new quarters.

Brett Willie, EAA 362666, learned to fly in a Cessna 140 a number of years ago. Flying his 1946 140 for a few years, Brett unfortunately needed a larger airplane once he had a family, so he sold it. But he never forgot how much he enjoyed it. Now he has another one, acquiring his 1949 140A in 2020.

“We had a growing family, so we needed a four-place; had that for 15 years,” he explained. “Then [I] turned around and bought this, because kids are grown up and needed something smaller just for the mission, for my missions for flying. I don’t go far distances, typical pancake breakfasts, and I just touch and go just within 100 miles of home 90 or 80 percent of the time. So that’s why we acquired this one. This is the last model. This is the A model. So it’s got the metal wing and [is] a little different [than my previous 140]. It’s got the 150 wing on it.”

With a mission of pleasure flying and hops around his local area, Brett

“[It’s a] good first airplane for a lot of people, if they want to get into flying and they don’t want to break the bank or pocket.”

— Brett Willie

said the affordability of flying something like a 140 is hard to beat.

“The [Cessna 175] Skylark we flew burnt 10 gallons an hour,” he said. “This thing burns 4.5 gallons an hour. I’m trading seats and I’m trading speed, but you can’t beat the economics of the airplane. I mean, 105 miles an hour, 4.5 gallons an hour. It’s easier on the pocketbook. Insurance is a little bit more because of the tail wheel … so I’m paying more for insurance, but my annual inspections are cheaper. That’s my mission with it. It’s just simpler flying. [It’s a] good first airplane for a lot of people, if they want to get into flying and they don’t want to break the bank or pocket.”

Brett also pointed out that a membership in the Cessna 120-140 Association is a must if you’re an owner of the type, as the support is invaluable.

“The takeaways I’ve had as a member is that if you had something that isn’t working right on your airplane, chances are one of the other pilots have had that same problem, or they’ve experienced it, or their buddies experienced it,” Brett said. “We have two tech counselors, two tech guys that are savvy with 140s inside and out.”

Aircraft: 1947 Cessna 120

Tail number: N2904N

Serial number: 13165

Aircraft total time: 5,607.81 hours

Time since major overhaul: 105.74 hours

Height: 6 feet, 3 inches

Wingspan: 33 feet, 4 inches

Length: 21 feet, 6 inches

Seats: 2

Empty weight: 890 pounds

Fuel capacity: 25 gallons

Engine: Rolls-Royce O-200

Horsepower: 100 at 2750 rpm

Electronics: Flightcom 403MC intercom, King KY-97A comm radio, Narco AT-150 transponder, ACK A-30 encoder, ACK E-01 emergency locator transmitter

The EAA Aviation Foundation will be offering a 1947 Cessna 120 as the grand prize in its 2025 Aircraft Raffle. The aircraft was donated by longtime EAA members David Stadt, EAA 489848, and Janet Stadt, EAA 757702. The Stadts fully restored the airplane in 1998, replacing the control cables, trim cables, and chains, as well as installing all new electrical wiring. Additional upgrades include circuit breakers on all primary breakers, new comfortable seating, and an improved exhaust system. New skins by Superflite products and Whelen wingtip strobes wrapped up the restoration. In 1999, this Cessna 120 received the Best of Class award at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh.

BY SPARKY BARNES

ARARE 1935 STINSON SR-6B Reliant assumed an imposing stance on the flightline during EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2023. Its grandeur easily captivated passersby, with its livery blushing cherry red under the summer sun. From its 300-hp Lycoming and wide-tread main gear to its amply curved empennage, NC15117 embodied the golden age of elegance in aviation. As for its rarity, there are only five of the SR-6 models currently listed on the FAA Registry, and NC15117 is thought to be the only one flying. There are two SR-6s (one of which is being restored by previous VAA President Susan Dusenbury), one SR-6A, and two SR-6Bs.

Owner Jim Sells of Peachtree City, Georgia, bought NC15117 in 2022. “I didn’t go looking for a Stinson, but I fell in love with this airplane very quickly,” Jim said. “It’s absolutely gorgeous — this was the epitome of quality in the 1930s. It flies very well, and it’s a very stable airplane. It has so many things I love — a big radial engine, leather seats, mahogany panel and steering wheels, and it’s a taildragger.”

Jim holds an airline transport pilot certificate (with multiple type ratings), a commercial glider rating, and a flight instructor and mechanic

certificate. He’s been flying since he was a teen, soloing a Cessna 150 in 1967. “The airplane rented for $10 wet, and the instructor was $5 an hour — but I was working at Jack in the Box for $1.75 hour! I got my private on my 17th birthday and my commercial the next year,” Jim said. “I was a reconnaissance pilot flying Bird Dogs in Vietnam, and then I crop-dusted for six years after that. I was flying everything from Pawnees to Ag Cats. Eventually I got hired by Delta and flew 26 years for them. I’ve always been fond of taildraggers; 10 years after I flew for Delta, I bought a Citabria and then a Starduster Too.”

In 1935, new Stinson Reliants were well received when they were showcased at the All-American Aircraft Show at Detroit. Stinson produced several SR-6 models: The SR-6 had a 245-hp Lycoming; the SR-6A had a 225-hp Lycoming; and the SR-6B had a 260-hp Lycoming. The SR-6 series was followed by production of the “gullwing” SR-7 Reliant. Aviation historian and author Joseph Juptner wrote this of the SR-6: “All models in the series were very stable, delightfully active when spurred, and exceptionally reliable.”

Era advertising by Stinson Aircraft Corp. touted: “Vacuum flaps allow plane to descend slower than a parachute” and highlighted the SR-6B’s features, including a 260-hp Lycoming, controllable-pitch propeller, auto dual controls, more speed, greater comfort, improved vision, and easier to fly. The company’s marketing focused on those vacuum flaps, stating: “Speed arresters between the ailerons and the wing roots permit the pilot to choose gliding angles ranging from the unusually long 10-1 descent to a steep descent, at decreased speed, enabling clearance of high obstacles at the edge of airports and allowing the ship to come to a complete stop in a short distance.

The speed arresters maintain lift during descent, contrary to the function of ‘air brakes,’ which merely offer increased resistance without providing the lift necessary to adequate control when landing at slow speeds.”

In the context of the 1930s, it’s interesting to note that the Bureau of Air Commerce reported, as of April 1, 1935, that a grand total of 13,886 pilot certificates and 6,855 aircraft licenses had been issued. That year, Stinson Aircraft Corp. initiated a Fly Safely campaign, with resounding success: “Private owners of Stinson Reliant planes, also Air Cab Operators using these planes, have flown approximately 7,000,000 miles in the first six months of 1936 without fatality to pilot or passengers, according to B.D. DeWeese, president of Stinson Aircraft Corp. This record is a continuation of the safety record of flyers of Stinson Reliants set in 1935.” (Aero Digest, 1936)

Perhaps because of its reputation for safety and reliability, the Stinson Reliant was quite popular with companies and private aviators, including the Union Oil, Texaco, and Richfield Oil companies; the Examiner Publishing Co. of San Francisco; Auburn Automobile Co.; Merrimac Aircraft Finishes; and notable individuals such as actress Ruth Chatterton. The Coast Guard operated a Stinson for radio research work, and Pollack Flying Service of Alaska had a Reliant. Braniff Airways flew Stinson Reliants between Waco and Galveston, and Dallas and Amarillo.

The airplane was favored abroad as well: “One of the leading newspapers of the Orient, Shimba Sha, has purchased a Stinson Reliant monoplane, Lycoming powered, for use in covering news stories in Japan. … It is understood that the cabin would be rebuilt into a portable photographic laboratory for use of news cameramen.” (Aero Digest, 1935)

The fortunate first owner of NC15117 was Charles J. Correll, who purchased it brand-spanking new on August 14, 1935. Though he owned it barely more than a year, he made sensational headlines wherever he appeared with the Stinson. Because of so many enthusiastic reports in the social media of the era, he inadvertently created a paper trail that has evolved through the passing of decades into a crown of provenance for this Stinson.

If you’re wondering just who Charles J. Correll was, here’s the answer: He was best known as Andy, of the highly successful Amos ’n’ Andy radio show, which was sponsored by such companies as Pepsodent and Campbell Soup. The comedy show aired from 1928 to 1960, and was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame in 1988.

In September 1935, The Indianapolis Times reported: “Charles J. Correll and Freeman Gosden, the ‘Amos and Andy’ of the air, have found a new pastime — flying. Each has bought a new Stinson plane. Andy’s Reliant cabin plane has already been delivered and both he and Mrs. Correll are flying it here at the Curtiss-Wright Airport. Amos has ordered an open cockpit Stinson [the parasol-wing Stinson Senior Trainer Model O]. … Both the boys have already soloed in their flying lessons. Mrs. Correll has also had eight and one-half hours in the air.”

They were taught to fly by C. “Slim” Freitag, who was well known and respected in his own right. Slim was a pilot and a trombonist for traveling bands. After teaching the Amos ’n’ Andy duo to fly, he became their personal pilot for seven years and described them as being wonderful to work for. Later, Slim worked as vice president in charge of sales at Howard Aircraft Corp.

An account published in the December 7, 1936, issue of Berwyn Life rendered an airy vignette of Charles Correll flying and “watching the panorama of life below him on its checkerboard canvas … destination, that pinnacle of popularity unapproached anywhere, any time, by any entertainer. … Correll is a licensed pilot with more than 300 hours in the air; spends

many of his week-ends at the Glenview airport, just flying around in his Stinson cabin plane … equipped with every conceivable safety device. … [Correll said]: ‘I’ve talked safety over the air for years … most accidents could have been avoided if proper precautions had been taken. … A good plane, kept in good condition and flown sanely, is much safer, in my opinion, than any other form of transportation.’”

It’s absolutely gorgeous — this was the epitome of quality in the 1930s.

In May 1937, less than a year after “Andy” sold the airplane back to Stinson Aircraft Corp., Roland Thomas and Gilbert Thomas (Thomas Brothers Flying Service) at Detroit acquired the Stinson. Ironically, the safety measures that Andy had promulgated seemed, unfortunately, to be lacking with NC15117’s new owners.

Though a full accident description wasn’t included in the airworthiness records, the repairs portrayed the damage incurred during an accident on July 1, 1937, at Detroit City Airport. Seven nose ribs and the leading edge of the left wing were replaced, and the wing was re-covered and repainted. The engine and propeller were returned to

the Aviation Manufacturing Corp. for major overhaul, and a new oil seal was also installed in the engine. A new left landing gear beam, fairing, and left wheelpant were installed. The left cabin step was repaired, and a new right front lift strut was installed. A new engine mount was installed, as well as a Smith controllable propeller and a new engine speed ring.

That accident, unfortunately, was somewhat of a prelude to a more egregious one.

A few years later, NC15117 would, a second time, illustrate the importance of “proper precautions” that Andy had emphasized. Stinson co-owner and pilot Gilbert Thomas, 32, encountered heavy snow and crashed in a wooded area of a farm. The Stinson suffered major damage, and the left wing was sheared off as it impacted trees.

The Air Safety Board of Washington, D.C., issued the aircraft accident report in June, which stated: “Engine failure forced the landing

of a Stinson airplane piloted by Gilbert E. Thomas near Lyndon, Kentucky, January 7, 1940, and injured four passengers en route from Detroit, Michigan, to Foley, Louisiana, the Air Safety Board recently reported to the Civil Aeronautics Authority. The pilot escaped injury, but the aircraft was virtually demolished. Investigation disclosed that Thomas failed to apply heat to the carburetor when he encountered a snow storm. Ice formed in the carburetor, gradually stopping the engine. The aircraft was ‘on instruments’ and without visual contact with the ground. By the time the plane had descended far enough for the pilot to see the ground, visibility and altitude were insufficient for him to avoid striking trees in his flight path. The aircraft, No. NC15117, was powered by a Lycoming engine.”

Despite the scope of the damage, the Thomas brothers evidently didn’t waste any time having the Stinson made airworthy again. By November 1940, the fuselage had undergone extensive structural repairs. Additionally, repairs were done to the landing gear and the hammock-style seats, and new left front and rear wing lift struts were installed. A new left wing panel was purchased, and on the right wing, some nose rib assemblies and a portion of the leading edge were replaced. The new/replacement parts were procured from Stinson Aircraft Corp. As for the engine, the bent crankshaft was replaced with a reconditioned one from Lycoming Division, and the factory also replaced the master rod bearing and assembled shaft. Shortly after the Stinson was made airworthy, it was sold.

NC15117 was shuffled from owner to owner in the 1940s and 1950s. Not much is readily known about its history during that time, except that it remained in Ohio from 1944 until 1957. The Thomas brothers sold it to W.B. Moore of Canton in December 1940. A month later, McKinley Flying Club of Canton bought it, and during its ownership, a Hamilton controllable propeller was installed in place of the Smith.

Thereafter, it was owned by Elsie and Rudy Van Devere of Akron. By October 1941, the aircraft hours were recorded as being 1,461:12 total time, and 272:59 since the last periodic endorsement in 1940.

The Stinson continued its journey through the hands of various owners, and for a portion of those years was owned by Arlo W. Mather of Cleveland (and/or his Air Transport Corp. at Mather Airport, and Mather Airpark Inc.). In the fall of 1945, repairs were made to the left landing gear leg, and the right wingtip bow was replaced.

Galon Williams, a veteran World War II B-17 pilot, acquired the Stinson and sold it to Edward Eckert in 1955. In 1957, Charles E. Woerner, a WWII veteran, OX-5 Club member, and charter member of EAA, owned NC15117 for a few months before selling it to a gentleman in Virginia. About nine years later, the Stinson migrated south to North Carolina, and then to various owners in Georgia. Current owner Jim Sells acquired the Stinson in November 2022.

“This airplane was crashed while World War II was going on, and it was dismantled and stuck in a warehouse for 60 years,” Jim said. “It was sent to Howard Kron, who has a reputation for museum-quality restorations. Howard spent eight years making this airplane what it is today; he did everything he could do to make it period-perfect.”

Howard Kron, of Clara City, Minnesota, penned his detailed account of the extensive restoration in “Radial Radio Star — Stinson SR-6 Time Machine,” in the February 2014 issue of EAA Sport Aviation. His article read, in part, “[The Stinson] crashed in November of 1945. It would remain flightless for the next 68 years. … This project was missing many parts, more than is typical of a restoration project.”

Obviously, a restoration of that magnitude was rife with challenges to be tackled. Ultimately, persistence, talent, and skills yielded a resounding success. According to the airworthiness records, a Lycoming R-680-E3A engine was installed using the original mount, exhaust, and cowling, and a Hamilton-Standard 2B20 propeller was installed. The airplane was re-covered with the Poly Fiber process and finished with Aero-Thane red, blue, and silver.

Howard wrote: “The aircraft was flown for the first time since 1945 on September 16, 2013,” and after being flown and checked out for a few hours, “owner Lee Watson and his friend Cliff Akin [flew] it back to Newnan, Georgia.”

Surprisingly pleased with the airplane’s handling characteristics, Jim shared: “The Stinson Reliant, in my opinion, has the best landing gear spacing, and it doesn’t have any air in the struts — it’s all oil, so it responds like you want. It has Cleveland wheels and brakes, and it’s very stable and doesn’t have any surprises on takeoff or landing. I almost always wheel-land it — that’s just what I do — and it wheel-lands beautifully. When you put it down, it just stays there. It’s very easy to stay on the centerline while you have the tail up going down the runway. We haven’t had any maintenance issues — we just check the oil and fly it.”

As of AirVenture 2023, Jim had put 30 hours on NC15117 since Thanksgiving 2022. Though he enjoys this elegant aerial steed, he admitted that he’s “a horse trader, and always [has] been. So I intended to immediately flip the Stinson when I bought it, but I like the airplane,” Jim said. “I love the attention it brings, but I don’t get

attached to airplanes, cars, or motorcycles. I move on — that’s just me.”

Speaking of AirVenture, Jim happily hasn’t missed attending the EAA convention since his schedule started allowing him free time, and he hasn’t missed one since 2014.

I love the people, the airplanes, the craftsmanship, the innovation — just everything here at Oshkosh.

—

“I mentor an 11-year-old boy and have brought him with me to Oshkosh for three years now. He’s flown in a C-47, Citabria, and this Stinson,” Jim said and smiled. “We love being here at Oshkosh, and he’s made buddies here. I love the people, the airplanes, the craftsmanship, the innovation — just everything here at Oshkosh. We are fortunate in America to have the number of blessings we have. You can’t do what we do here anywhere else in the world!”

Those fortunate enough to enjoy the vintage aviation world would, no doubt, heartily agree with that sentiment.

TC 580

Not eligible to be flown by a sport pilot.

WINGSPAN: 41 feet

LENGTH: 27 feet

HEIGHT: 8 feet, 5 inches

EMPTY WEIGHT: 2,347 pounds

USEFUL LOAD: 1,203 pounds

GROSS WEIGHT: 3,550 pounds

PAYLOAD: with 50-gallons of fuel, 703 pounds (4 passengers and 23 pounds baggage)

PAYLOAD: with 75 gallons of fuel, 546 pounds (3 passengers and 36 pounds baggage)

ORIGINAL ENGINE: 260-hp Lycoming R-680-5

PROPELLER: Lycoming-Smith controllable

FUEL: max 75 gallons

OIL: 4-5 gallons

MAX SPEED: 142 mph

CRUISING SPEED: 130 mph

LANDING SPEED: 52 mph (with flaps)

RATE OF CLIMB: 800 fpm

SERVICE CEILING: 15,200 feet

CRUISING RANGE: 455-660 miles at 14 gph

BOLD AND BRILLIANT, this stunning 1938 cabin Waco was proudly poised in front of the VAA Red Barn all week during EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2024. Its blue and white livery glimmered under the summer sun, a radiant reflection of the golden age of aviation. Superb in detail from nose to tail and headliner to rudder pedals, the attention lavished on this restoration was readily apparent. This Silver Lindy winner is a sensational harbinger of a burgeoning younger generation who exudes a contagious enthusiasm for vintage aviation.

Spend just a few moments talking with Trevor Niemyjski by the wings of his gorgeous cabin Waco, and you’ll easily sense his genuine and deep-rooted passion for aviation. It becomes equally apparent that Trevor’s quietly confident ambition and talent is born of a strong family heritage. Just 31, he’s already completed five airplane restorations: an Aeronca Chief, clipped wing Taylorcraft, J-3 Cub, Waco UPF-7, and this cabin Waco.

Trevor’s dad, Justin, inherited his love for flying from his father, Roman. Justin took his first flying lesson at 23, and within a year, bought a Piper Pacer, passed his checkride, and acquired his tailwheel endorsement.

Trevor had his first airplane ride at age 5 in a Piper Clipper. He grew up around tailwheel airplanes operating from the family’s backyard airstrip in Wisconsin, and started taking flying lessons in his dad’s Pacer. Trevor soloed on his 16th birthday and worked a summer job so he could pay for his own fuel and flight instruction. Ever since, he’s worked diligently to afford the joy and privilege of flying and restoring airplanes.

Elaborating on his family background, Trevor said, “Grandpa [Roman Niemyjski] grew up in Hales Corner, Wisconsin, so he was part of the EAA group. He started flying back in the 1970s and was really into antique airplanes. He got into helicopters some, too. Grandpa bought an Aeronca Chief as a first anniversary present for my Grandma, even though she didn’t fly. Grandpa flew the Chief for about 10 years, and then it needed new fabric. So it got taken apart and was stored while Grandpa started his excavating business. Then when Dad started flying, Grandpa got back into flying. I’ve been around vintage antique aviation pretty heavy since I was about 6.”

Trevor has his own young family now. Notably, he has an admirable way of finding — or making — the time to restore vintage and antique airplanes, replete with the patience and understanding of his wife, Emily, and their four children: Kalina, 7; Eivin, 5; Adelyne, 3; and Elsie, 1.

At 15, Trevor purchased his first project, the Chief, from his grandfather. He completed the Chief restoration by the time he was 18. Trevor soon began garnering attention in the world of vintage restoration when he flew his restored Chief to Oshkosh in 2011. He was interviewed during the Vintage in Review session, and in 2016, Ron Alexander interviewed and quoted Trevor in his Youth in Action online column for EAA: “I personally like the challenge of a tailwheel airplane, and I think it is good for any pilot to learn in a tailwheel, if possible. Most important, find an instructor who will truly teach you to ‘fly’ the airplane. … Flying … brings a sense of being free, of relaxing, and of enjoying God’s creation.”

After he completed the Chief, Trevor sold his car and saved his money. “Then I was able to purchase a Monocoupe 90A with a Lambert engine — that’s where I got the antique bug,” Trevor said. “I ended up selling that to fund this cabin Waco project.”

Aviation author and historian Joseph Juptner described the 1938 S-model as having “all the nice habits of earlier versions of the S-type and none of the little annoying ones. … 1938 models introduced the new landing gear with 108-inch tread using oleospring shock struts of 8-inch travel, and hydraulic wheel brakes; foot-operated brake pedals were standard on all models now. ... [and] the landing gear was moved forward by 4 inches.” (U.S. Civil Aircraft)

Era advertising touted: “The Waco model ‘S’ offers every essential of comfortable, swift flight — at the lowest passenger-mile cost of any airplane! Low in price and operating cost, yet smartly and comfortably finished, the model ‘S’ has a unique appeal to private owners and commercial operators.”

This venerable cabin Waco changed hands well over a dozen times through the decades. Perhaps its most interesting history can be gleaned through various portals of time regarding the young man who acquired it in September 1938. According to aircraft records, William (Bill) Frederick Slaymaker of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, became NC19373’s first private owner. A chattel mortgage of $3,618.90 with

monthly installments of $301.50 was arranged, with the final payment due in September 1939.

“The history of the airplane was shared with me by Bill Batesole. Bill contacted me soon after I purchased the project. He asked my intention with the airplane, and when he knew I had a serious plan to restore it, he went on to tell me he was friends with the original owner, Bill Slaymaker,” Trevor recounted. “The airplane was gifted to Bill Slaymaker by his father as a graduation gift from Yale, and had the fitting Yale colors. Slaymaker’s dad had bought him a Fairchild 22 for his high school graduation. Bill Batesole then told me he had a couple original photos of Bill with the Waco, along with a wooden scale model that Slaymaker had given him. He kindly sent me the photos and model, and was able to make it to Oshkosh to see the Waco. I’m thankful to him for putting me in touch with the history.”

The Slaymaker family was prominent in the community (Bill’s father founded Slaymaker Locks), and local newspapers gave them quite a bit of ink. Apparently, Bill was a popular and busy student. He sang tenor and was manager of the Yale University Glee Club, and was a member of the Whiffenpoofs (an a cappella group), Delta Psi fraternity, and rugby football team. He was also president of the Yale Flying Club and the New England Intercollegiate Flying Club, as well as president of the Yale-Corinth Yacht Club.

Reportedly, Bill flew to Ohio in September 1938 for the National Air Races at Cleveland. In June 1939, he graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree. In early July, Bill flew in the annual air meet of the National Sportsmen Pilots Association at Alexandria

Bay in Thousand Islands, New York. He married in August 1939, and before a year had passed, his Waco had flown away to a new owner.

James McArthur Thomson of Connecticut bought the Waco from Bill Slaymaker in March 1940. In 1942, some wing and landing gear repairs were made. Ten years later, Winford Newton bought it, and in 1953, The Gopherbroke Inc. purchased it. While they owned it, the airframe was stripped of fabric and extensive cleaning and inspection commenced. Joints were reglued, steel was zinc-chromated, the cowling and fairings were stripped, and the airframe was re-covered with Flight-Tex Grade A fabric. Murphy and Titanine clear and pigmented dopes were applied.

in. The doors were held shut with a rope, and Jim managed to untie the knot enough to look inside. There it sat, disassembled and covered with dust — and the floats were still with it. Jim had recently rebuilt a Champ and traded it for the Waco in 1992. His intentions to restore NC19373 eventually faded when he realized the project would take more resources than he had at the time. He sold the YKS-7 to Ten Air Aircraft Corp. (William Bruggeman) of Blaine, Minnesota, in 1995.

“Most of the airplane was built after 10 o’clock at night.” — Trevor Niemyjski

In 1955, the cabin Waco was purchased by Ernest Kubicz of Massachusetts, and from that point, it changed hands at least eight more times, staying in the northern states, mostly in Minnesota. The Three Way Flying Club of Owasso, Minnesota, bought it in 1963. It had Edo 3000-series floats, dual water rudders, and Waco vertical seaplane surfaces installed. Apparently, that’s when the second door (left side) was added.

Minnesotan Thomas Orlowski bought the Waco in 1970 and based it at Lake Elmo Airport. It resided there for a couple of decades, until a local pilot/mechanic, Jim Anderson, heard about it. A cabin Waco was one of his dream airplanes, and he did some scouting around the airport to find the hangar it was

In 2016, the Bruggeman collection of about 20 airplanes went up for sale. “Forrest Lovley and I were sitting around the campfire at Brodhead, and he told me about the collection coming up for sale. He asked me if I knew anyone who wanted a flyable cabin Waco on floats, or a project cabin Waco,” Trevor said.

“I told him I’d love to buy the flying Waco, but I couldn’t afford that one — but I thought I could pull off the project. I talked to my wife, Emily, and we decided we could buy it. Our oldest daughter had just been born, and a family airplane fit the bill for us.”

Trevor bought the cabin project in 2016 and started working on it in 2018. Fortunately, NC19373’s fuselage had been rebuilt, and the wings were about three-quarters done. But there remained a mountain of work to be accomplished, and parts identification and acquisition evolved into a time-consuming task.

“I had to find a few large items, like wheelpants and a windshield. Luckily, I did locate a set of wheelpants. I was able to get a windshield from Jon Nace — it was from a different airplane, but it fit pretty decent. Addison Pemberton sent parts to me. There was a lot of little stuff I needed, and some of the landing gear fittings were missing. I called Jon Nace to see if he had any, but he didn’t. Jon said if I’d send him a drawing, he’d see what he could find,” Trevor recalled. “I didn’t hear from him for a couple of weeks. Then one day, a package shows up in the mail, with a note from Jon saying he had nothing else to do, so he made one for me!”

Trevor had a couple of period-correct instruments but not all that he needed. He put the word out, and again, his cadre of Waco compatriots from across the country came to the rescue. “That was a big hunt, and Vaughn Lovley and his dad, Forrest, really came through for me, along with Ryan Harter and his son, Michael. And again, Jon Nace — I got the compass from him. The guys have just been great! I’ve called so many people with questions, including Andy Anderson and Neal Goodfriend, and have gotten answers. Nonexistent parts show up. Custommachined parts that were needed show up in the mail. The antique community is truly amazing!”

The instrument panel itself presented a challenge in particular, because Trevor couldn’t find any Waco

drawings for it. “So I used what was left of the original panel that I had and borrowed from what Vaughn had done to his panel. I also talked with cabin Waco owners/restorers Dave Allen and Roger James to see what was right for my panel — getting it right was a big job. I used the Grain-It Technologies kit to give the panel a nice [faux] wood finish.”

As is customary in restorations these days, Trevor included a few things for safety. He mounted a radio underneath the panel and an emergency locator transmitter in the fuselage. He also installed circuit breakers instead of fuses and concealed them from view.

Terry Bowden, of Certified Aeronautical Products LLC of Texas, assisted with several tasks. He approved the installation of a B&C alternator and voltage regulator. The old Jacobs L-4 engine was overhauled by Radial Engines Ltd. and converted to a 275-hp Jacobs R-755-B2.

The old Hayes hydraulic brakes and wheels were replaced with Cleveland wheels and hydraulic disc brakes. That necessitated removal of the original rudder pedals, which were replaced with Fairchild PT-19 rudder pedals.

Trevor found it difficult to locate someone who had the time and interest to do the upholstery. So he decided to try his hand at sewing. Emily encouraged him and went down to the basement and brought up her grandma’s vintage Singer sewing machine.

“It was a very early electric machine, without any bells and whistles at all. Trevor had never sewed a day in his life! I told him what I knew about sewing — which wasn’t much — and we made a couple calls to Grandma, and then he had it,” Emily said. “He did a beautiful job sewing the headliner on that machine, and then he got an industrial sewing machine so he could do the rest of the interior. It was so fun to watch him learn what he needed to know!”

Trevor chose a durable faux leather (vinyl) for the seat covers and side panels, which are patterned after the originals, and cut new foam for the existing seat frames. His prior restoration experience facilitated the requisite tasks he encountered — from working with wood and fabric to forming sheet metal.

“A project like this is attainable. You just have to want it and go after it!”

— Emily Niemyjski

We have hundreds of quality FAA-PMA approved parts specifically for the Luscombe 8 series aircraft, plus distributor parts such as tires, tailwheels, and more.

Call us or visit our website to request your free Univair catalog. Foreign orders pay postage.

Speaking of sheet metal, some of the Waco’s original color was revealed while

stripping paint. “It was a Berry Chrome Blue metallic, which is kind of rare,” Trevor said. “We couldn’t find the color chip on the Berryloid charts.”

Emily helped Trevor select the new colors: AirTech 336 Daytona Metallic Blue, 097 Standard White, and 657 Saddle Metallic. It’s a stunning combination, and appropriately reminiscent of the Waco’s original livery.

As for his choice of coatings, Trevor has developed a personal preference for the AirTech system. “I love the AirTech coatings; they shoot a little easier,” he said, “and the paint covers really nice with my HVLP [high volume, low pressure] spray gun.”

Emily is undoubtedly Trevor’s most cheerful and enthusiastic champion. “Trevor restored our family’s Waco in a shop we built in our backyard, and I had no idea what all it would entail when he started it four years ago. I love it, and it’s been really neat to watch him working on it! I got to help with different things like rib stitching, fabric taping, turning a wing over — just whatever he needed help with,” Emily said and smiled. “Our kids loved being out there whenever possible, and our daughter Kalina always wanted to be the one to roll the fabric out on the wing. I hope they all grow up to appreciate antique aviation.”

It’s also clear that Trevor cherishes Emily as well. “Emily doesn’t fly, but she loves flying with me. She’s very supportive, and there’s no way I’d have finished the Waco without her. She and our kids have been very understanding about allowing me the time to work on this during the last four years,” Trevor

said. “I do excavating and construction work full time, so most of the airplane was built after 10 o’clock at night. I worked on it usually one or two nights a week, and then Fridays were my nights to work out there from about 9 p.m. until 3 a.m. Then this past spring, Emily knew it was a push, because I wanted to get to Marginal Aviation’s First Ditch fly-in at Le Sueur, Minnesota. She was real forgiving of the time; almost every night of the week after work I was out there and on the weekends, too.”

Trevor’s dad, Justin, devoted quite a bit of time and energy during those last two months of the project, and Trevor was especially grateful for the extra help.

In May 2024, NC19373 rumbled down the runway, climbing skyward after decades of being tethered to terra firma. There is no feeling quite like flying an airplane that you have brought back to life with your own hands. After flying his cabin Waco, Trevor had a fulfilling sense of euphoria, combined with a deep appreciation of all those who spurred and supported him along the restoration pathway. He wowed the vintage/antique community when he touched down in his beautiful, brilliant blue Waco at First Ditch.

Trevor’s four-year restoration of NC19373 was met with resounding congratulations from family and

SPECIFICATIONS (AS ORIGINALLY POWERED)

SEATS: 5

LENGTH: 25 feet, 3 inches

HEIGHT: 8 feet, 6 inches

UPPER WINGSPAN: 33 feet, 3 inches

LOWER WINGSPAN: 28 feet, 3 inches

CHORD: 57 inches

AIRFOIL: Clark Y

EMPTY WEIGHT: 1,882 pounds

USEFUL LOAD: 1,368 pounds

BAGGAGE CAPACITY: 100 pounds

PAYLOAD WITH 70 GALLONS FUEL: 740 pounds

GROSS WEIGHT: 3,250 pounds

ENGINE: 225-hp Jacobs L-4

CRUISE: 130 mph

LANDING: 50 mph

CLIMB AT SEA LEVEL: 800 fpm

CEILING: 15,000 feet

GAS CAPACITY: 70 gallons

OIL CAPACITY: 5 gallons

CRUISING RANGE: 590 miles (at 15 gph)

DERIVED FROM JUPTNER’S U.S. CIVIL AIRCRAFT.

friends. Later, at AirVenture, he received more kudos — especially when the Vintage judges deemed his 1938 Waco YKS-7 as the 2024 Antique Reserve Grand Champion Silver Lindy winner.

Previous owner Jim Anderson said, “It’s nice to know that it’s been restored and it’s flying again. That’s pretty cool; it was an ambitious project!”

Trevor’s dad, Justin, shared the following during a Vintage in Review session: “I’m very proud of Trevor. A lot of times people will give me a hard time, saying, ‘What are you building all these airplanes for, and spending so much time doing that? You should be spending time with your family.’ To that, I quite often will say, ‘We’re not just building airplanes. We’re raising young boys to be men.’”

Justin’s reasoning brings to mind an apropos Zig Ziglar quote: “What you get by achieving your goals is not as important as what you become by achieving your goals.”

Emily has been continually amazed by her husband’s talented craftsmanship and persistent determination to succeed. “Trevor’s ingenuity and devotion are an inspiration to me and our kids,” she shared. “And I think it’s inspiring to other people, too, when they find out our ages and all the kids we have, to realize that a project like this is attainable. You just have to want it and go after it!”

THERE WAS ONE AIRPLANE at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2024 that was so heavily disguised through aerodynamic modifications, it’s likely that fewer than 10 percent of the flightline warriors recognized it for what it is. As far as that goes, what started out as a Piper PA-23 Apache probably wouldn’t have been regularly recognized even if it hadn’t been modified. Sadly, we don’t see many Apaches anymore. And we most definitely don’t often see many Apaches that look like this one. Sporting every modification in the Seguin Aviation Geronimo catalogue, what has often been described as a flying sweet potato had been turned into a hyper-svelte cross-country hustler. Owner Mike Haney, EAA Lifetime 1133354, Tehachapi, California, has a long history in aviation that has culminated in N400MJ. It’s possibly the most recent and most detailed Geronimo Apache in the country.

he added. ‘I started giving lessons and loved it. I bought a 160-hp Apache, in which I logged more than 1,500 hours of dual given.”

Mike’s career in aviation took him all over California.

“From that point on,” he said, “my life consisted of multiple moves up and down California, during which I became the youngest IA/A&P to taxi Boeing 727s and McDonnell Douglas DC-10s while doing maintenance for Continental Airlines. Then it was back up to Lancaster, where I had started

“I started learning to fly at about the same time, and by December of 1980 had my CFI,”

I’m as much a mechanic as I am a pilot, so the concept of restoring the Geronimo scratched a number of itches.

“I was bought up in Lancaster, California,” Mike said. “There was no aviation in the family, and I hadn’t given it much thought until I had to write a high school paper on trade colleges. At the time, I was always working on lawnmowers, motorcycles, go-karts, and minibikes. So when I ran across information on Northrop Institute of Technology A&P school, I started looking into it. This was 1975, and changes started happening quickly. That same year, I showed up at Northrop and stayed in their dorm. I took the written and oral exams in December of 1976, and almost immediately, I was a certified A&P working on Santa Monica Airport. I had never been in a general aviation airplane even once, and when my boss said, ‘Work on this,’ he teamed me up with one of his longtime A&Ps, and just like that I was a professional mechanic! I’d been out of high school less than three years!

— Mike Haney

If you didn’t know it was a Geronimo Apache, it would be easy to misidentify it as an Aztec.

working on GA aircraft at Fox field. From there, I worked for GE at Edwards AFB, building engines for advanced military aircraft. I later set up a flight school and FBO at Fox in my own building. After a number of years, I sold that business but kept the three 172s I was operating on a traffic-watch contract that I had in the Los Angeles area.

“I flew Sabreliners and Learjets for corporations and Part 135 operators for years,” he added, ‘and then started another FBO that my son, Jeffrey, and his wife bought from me three years ago and own today at our same location on Fox field, Lancaster, California. Jeffrey is why we bought another Apache. He needed it to build time to move up the corporate pilot ladder and is now flying a Gulfstream 600 in a 135 operation in Van Nuys and [is] now

rated in the new G700. Because Jeff is a captain in the G600, it only took him five days to get typed in the new G700.”

They got the aircraft for a steal because of its condition.

“The Apache we bought was a very tired and ugly PA-23 that had been given all of the Seguin Aviation Geronimo modifications,” Mike said. “No corners were cut, but the airplane had been flown hard and put away wet far too often and for far too long, which is why it was priced at only $16,000! We put many times that amount in it to bring it up to the state it is in today, and did so gladly.”

First some Apache and Geronimo history. The original Piper PA-23 Apache was neither a Piper nor an Apache. It was a Twin Stinson. At that time, Piper had a long history in building rag and tube airplanes, from Cubs to the short-wing series. When Piper bought the Stinson division of Consolidated Vultee in 1952, its competition was building monocoque aluminum airplanes, including the first light twin, the Cessna 310. Included in the Stinson acquisition was a new light twin prototype. Stinson was also a rag and tube company, and its twin was a taildragger that featured a fabric-covered tubing fuselage with fat wings, a twin tail, and 125-hp Lycomings. Piper put a nose wheel on it, upped the power to 150-hp O-320s per side, shortened the tubing to just aft of the baggage door on the new aluminum fuselage (the aft section is monocoque), and replaced the twin tail with a traditional single unit. The decision to maintain wing-to-wing steel tubing and tubing from the firewall to behind the cabin was a good one. It is one reason why, as long as the tubing isn’t allowed to rust (the bottom longerons are fairly easy to splice in repairs), Apaches seem to last

forever. Steel can be designed to never fatigue. Aluminum can’t. Apaches with well over 30,000 hours (!) are still reportedly being used in specialized flight schools. The actual performance of the original post-1957 160-hp Apaches is actually similar to modern multiengine trainers. Its performance is not spectacular, but it fits the training role well.

One notable flight characteristic of the Apache is that it is possibly the most benign twin-engine airplane in the universe in that losing an engine is easily managed. However, with the original 150/160-hp engines, if one quits, the airplane is under control but the single-engine performance is marginal.

Enter Seguin Aviation in Seguin, Texas. Discontinued in 1965 and

The airplane is amazingly comfortable to fly, and we intended on taking a lot of long trips, so we didn’t cut any corners in doing the seats and upholstery.

— Mike Haney

superseded by the follow-on Aztec, the prices on the Apache dropped quickly, making it a highly affordable starting place for a company like Seguin to modify. When modified, it may not have been as fast as its competitor, the Cessna 310, but it was much more comfortable. Additionally, it was easier to fly, and its pilot-friendly single-engine characteristics made it much safer for the average pilot. It did all of this on much less fuel.

Seguin was the most successful of the Apache modification companies. The original airplane was often called the flying sweet potato. Its blunt nose beat its way through the air, and once the air was forced aside, it had to climb over a less-than-streamlined windshield. To make matters worse, the

main gear protruded partway out the bottom of the wings, and the hard-to-remove engine cowls were almost as blunt as the nose. Seguin had modifications for each of the airplane’s shortcomings.

A single-sentence description of the original Apache could be, “It was

a massive, tremendously comfortable cockpit surrounded by an array of easily improvable appendages.” Six inches wider than a Baron, there are few if any light airplane cockpits that can challenge an Apache for pure comfort and size.

Mike explained why they picked the Apache.

“If someone is trying to build twin time, which Jeffrey was, an original Apache is hard to beat from operating cost and safety points of view,” he said. “However, it’s slow and not very pretty. And then we ran across the abused Geronimo N400MJ. Being an old Apache guy, I had always admired the Geronimo conversions, so we couldn’t let that one get away. I’m as much a mechanic as I am a pilot, so the concept of restoring the Geronimo scratched a number of itches.”

The aircraft needed a lot of work, according to Mike, starting with the fuel tanks.

“To give an idea of what kind of airplane N400MJ was when we found it, we drained close to 5 gallons of water out of the fuel tanks,” he said. “There are four of them, and they’re bladders, which we replaced. The squared-off Hoerner tips are also tanks and hold 24 gallons apiece for over 200 pounds of fuel total. However, we’d never use them because the normal tanks hold 108 gallons. With the tips, the airplane could carry 156 gallons! Even if burning 11 gallons a side, we have a solid five hours of fuel without the tips. No one wants to sit in an airplane longer than that.

“Basically, we took the airplane completely apart and, starting at the long 31-inch Seguin nose, began inspecting and replacing everything we found,” he said. “The Seguin nose is Fiberglas, and it was in decent condition. A little sanding and filling to get it ready for paint was all it needed. However, that’s also where we mounted the fluxgate for the Garmin G500 flight display and the GPS antenna. We can also put 25 pounds of baggage up there.”

Next, they tackled the engines.

“The 180-hp O-360 Lycomings got us home on the two-hour ferry flight from the Monterey Bay area to Fox field, but they’d been sitting for a long time and were past due for overhaul,” Mike said. “They went to Ly-Con, where they worked their usual magic and not only brought everything up to spec, but, in so doing, used first-run cylinders from one

of my 172s. They flowed those, and the engines wound up putting out 205 hp on the dyno. That’s a good thing!

“The cowlings that Seguin put on their Geronimos were real works of aeronautical art,” he added. “It has been proven that their cowling design, besides making checking oil and everything else much easier, makes a huge contribution to the speed. More so than even the nose, which is counterintuitive.”

The windshield and panel were next.

“The single-piece Seguin windshield needed to be replaced, along with all the other glass, and the instrument panel was basically made new,” Mike said. “The instrument panel is all Garmin glass to include a G500 flight display, GMA 340 audio panel, GTN 750/650 navigators, GTX 327 transponder, GDL 88 ADS-B In/Out, and a totally overhauled Century III autopilot system. I am waiting for Garmin to certify the GFC 500 autopilot for the PA-23, the greatest autopilot ever. (Hint hint.)”

Mike said the landing gear worked, but since they had the oleos on the bench, it made sense to replace all the bushings and overhaul everything. That included replacing every hydraulic line they could find. Also, the airplane had the early four-rib flaps, which are only good for an operating speed of 100 mph, so they took those apart and rebuilt them with seven ribs that moves the flap speed up to 125 mph.

Finally, they focused on updating the interior.

“The interior looked as you’d expect it to look,” he said. “Worn and dirty and as if ugly things were living just under the upholstery. One of the problems with airplanes like these is that if there were leaks anywhere, the soundproofing foam inside the aluminum skin soaks up the moisture, which goes to work on rusting the tubing. We stripped the upholstery out and totally gutted the fuselage. This completely exposed the tubing, which fortunately was in good shape. In fact, the insides of the wings and the tubing were in such good condition because all the parts were coated with the old-style zinc chromate. That stuff is better than powder coating and is nearly indestructible.

“The airplane is amazingly comfortable to fly, and we intended on taking a lot of long trips, so we didn’t cut any corners in doing the seats and upholstery,” he said. “We had everything done in leather and installed a suede headliner. All of that is backed with modern soundproofing materials. The Seguin baggage compartment is 15 inches longer than the stock Apache one, so we detailed that area, too. Ditto for the motor mounts and about a thousand other things that needed updating. When you have an airplane as far apart as this one was, and you make one part look new, that makes everything around it look old, so it just makes sense to do all the details.”

Mike is happy with the work they put into the airplane and how well it flies.

“The hardest part of the project, which my son and I did together, was getting him to relax and just keep working until the part we were doing at the time was finished,” he said. “Don’t rush anything. I’ve always been a nitpicking mechanical type, and this was frustrating him.

I was visualizing this airplane as a keeper, the last airplane I’d ever buy for my personal use. So essentially, I looked at the airplane as if we were remanufacturing it to new.

“Now that we’ve been flying the airplane for a few years, I’m so pleased with it, that every dollar and hour we put into it was worth it,” he said. “I flight-plan 180 mph at 8,500 feet, so lots of airplanes are faster, but at 66 percent power, I’m only burning about 22 gallons total. So as with the jets, I can just sit there — it’s more comfortable than you’d expect — and fly four-hour, 700-mile legs with an hour reserve, in almost any kind of weather. My home field is 4,000 feet MSL, and at full gross, I’m still getting 1,100-feet-per-minute climb, and my single-engine ceiling is 12,000 feet. To get twin-engine performance better than that, you’d be burning a lot more gas and be flying a far more expensive airplane. Also, my VMC is 72 mph, but we also installed the Micro AeroDynamics VGs, and at 3,500 feet MSL, it stalls (54 mph) before it loses directional control. How many twins can say that?