AWARD-WINNING 172 FOR THE LOVE OF A CUB VINTAGE

JUDGING

AWARD-WINNING 172 FOR THE LOVE OF A CUB VINTAGE

Praise for a dedicated volunteer

ONCE EVERY DECADE OR so someone who makes a big difference comes along. It’s someone who quietly and without great fanfare contributes their time and resources to make things a whole lot better for the rest of us. That could describe quite a few people. But in this instance, I am describing longtime VAA and EAA volunteer George Daubner. George began his volunteer “career” with Vintage in 1986 serving as an advisor to the Antique Classic Division of EAA from 1986 to 1988. In 1988 he accepted a position on the Antique Classic board of directors. (The Antique Classic Division of EAA had a name change and is now the EAA Vintage Aircraft Association.) After 38 years of board service, George has decided to retire at the end of his current term in office, which ends at EAA AirVenture this summer. Afterward he will be a VAA director emeritus, and the VAA board of directors will certainly seek George’s counsel. Heck, George knows where all of the bones are buried!

From 1986 to about 2000, George was VAA’s co-chair of aircraft parking and flightline safety. Upon joining the EAA B-17 program, he appointed a team to reorganize and further define the position that he held at Vintage. The team appointed by George included a whole lot of talent that went on to create workable and successful programs and areas of operation. The greater

After 38 years of board service, George has decided to retire at the end of his current term in office, which ends at EAA AirVenture this summer.

majority of those team members are still in those positions, by the way.

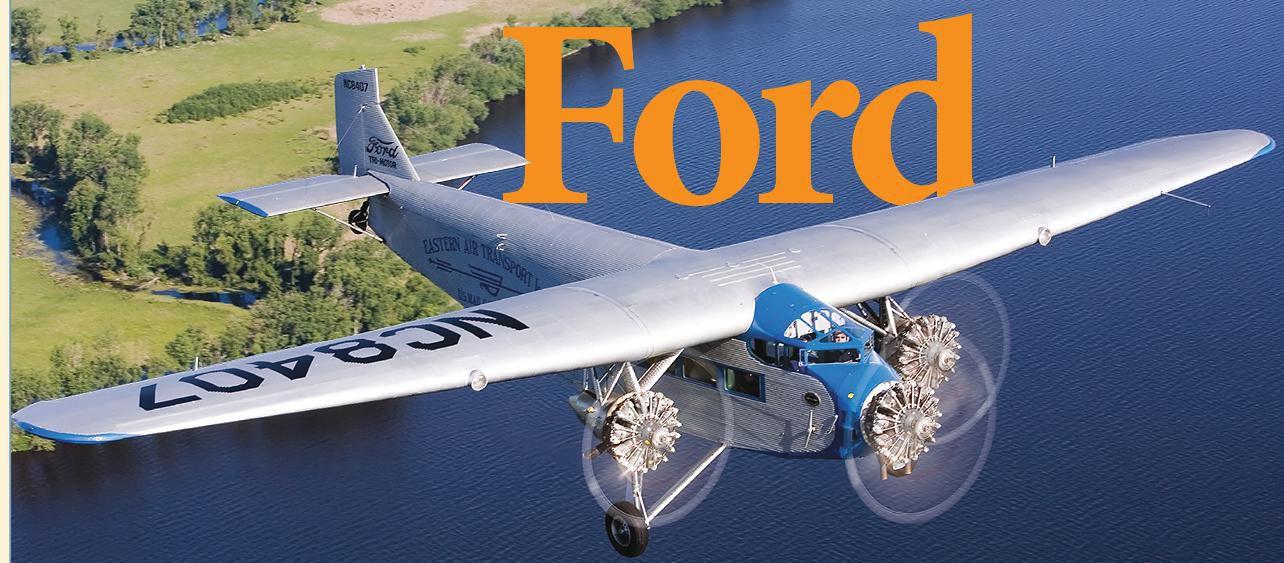

In the real world, George was a corporate pilot flying an Aero Commander 690. He accumulated just more than 17,000 flight hours in his long and successful career as a pilot. It’s really a remarkable accomplishment to go from a first solo in a Cessna 150 at a young age to flying captain on an Aero Commander 690. By the way, not all of those 17,000 hours were flown in his chosen career. George was also a volunteer pilot for EAA in the B-17 program where he accumulated 1,760 flight hours. He also volunteered at EAA’s Pioneer Airport operations and flew the Ford Tri-Motor, Waco YKS, and Travel Air 4000, where he logged more than 1,000 hours combined in those three aircraft.

May/June 2024

Publisher: Jack J. Pelton, EAA CEO and Chairman of the Board

Vice President of Publications, Marketing, Membership and Retail/Editor: Jim Busha / jbusha@eaa.org

Senior Copy Editor: Colleen Walsh

Copy Editors: Tom Breuer, Jennifer Knaack

Proofreader: Tara Bann

Print Production Team Lead: Marie Rayome-Gill

Senior Sales and Advertising Executive: Sue Anderson / sanderson@eaa.org

CONTACT US

Mailing Address: VAA, P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903

Website: EAAVintage.org

Email: vintageaircraft@eaa.org

Phone: 800-564-6322

Visit EAAVintage.org for the latest information and news.

Current EAA members may join the Vintage Aircraft Association and receive Vintage Airplane magazine for an additional $45/year.

EAA membership, Vintage Airplane magazine, and one-year membership in the EAA Vintage Aircraft Association are available for $55 per year (Sport Aviation magazine not included). (Add $7 for International Postage.)

Foreign Memberships

Please submit your remittance with a check or draft drawn on a United States bank payable in United States dollars. Add required foreign postage amount for each membership.

Membership Service

P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903-3086

Monday–Friday, 8 AM—6 PM CST Join/Renew 800-564-6322 membership@eaa.org

EAA AirVenture Oshkosh www.EAA.org/AirVenture 888-322-4636

12

Tall Pines Café

An AirVenture staple for more than 20 years

By Emme HornungGuidance from a Vintage Aircraft Association

judge

By Sparky Barnes26

Waco Fever Strikes ... Again. And Again. And …

Tony Caldwell and his pair of award-winning Waco F’s

By Budd DavissonPat Harker’s sparkling straight-tail Cessna 172

By Sparky Barnes50 Piedmont Airlines Began With a Cub?

Not really, but close!

By Budd Davisson

2024 / Vol. 52, No.

01 Letter From the President

of the Red Barn

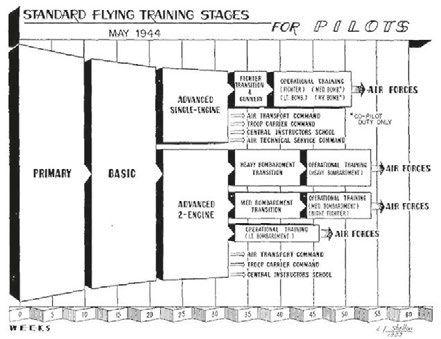

60 The Vintage Mechanic Teaching a Nation How to Fly –The Lon Cooper story, Part 5 By Robert G. Lock

Front

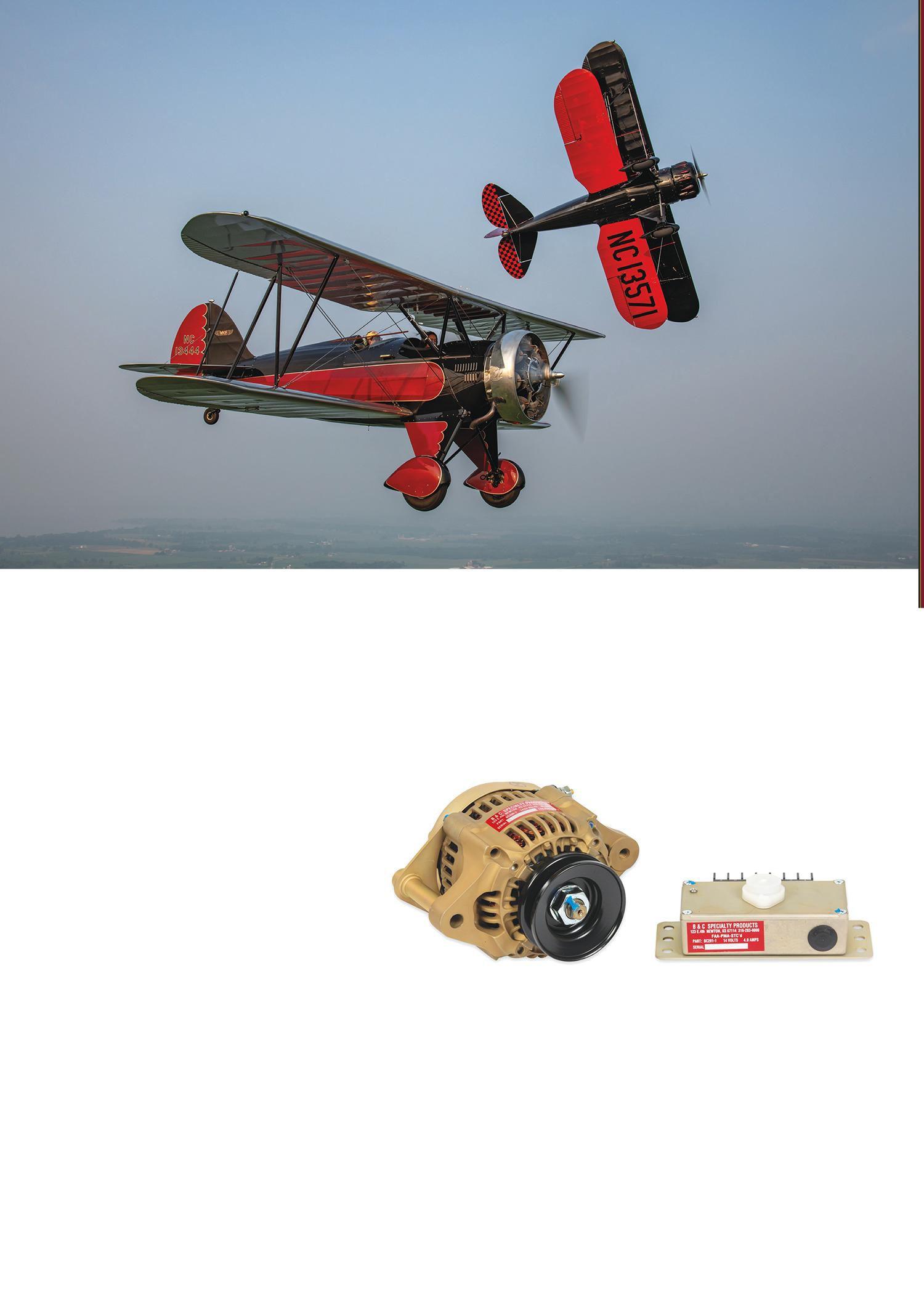

Jared Calvert (front Waco) and Clay Adams (rear Waco) fly Tony Caldwell’s award-winning Wacos near Oshkosh.

Photography by Connor Madison.

Back

Don Wade flies the award-winning Piper Cub he lovingly restored.

Photography by Andrew Zaback.

For missing or replacement magazines, or any other membership-related questions, please call EAA Member Services at 800-JOIN-EAA (564-6322).

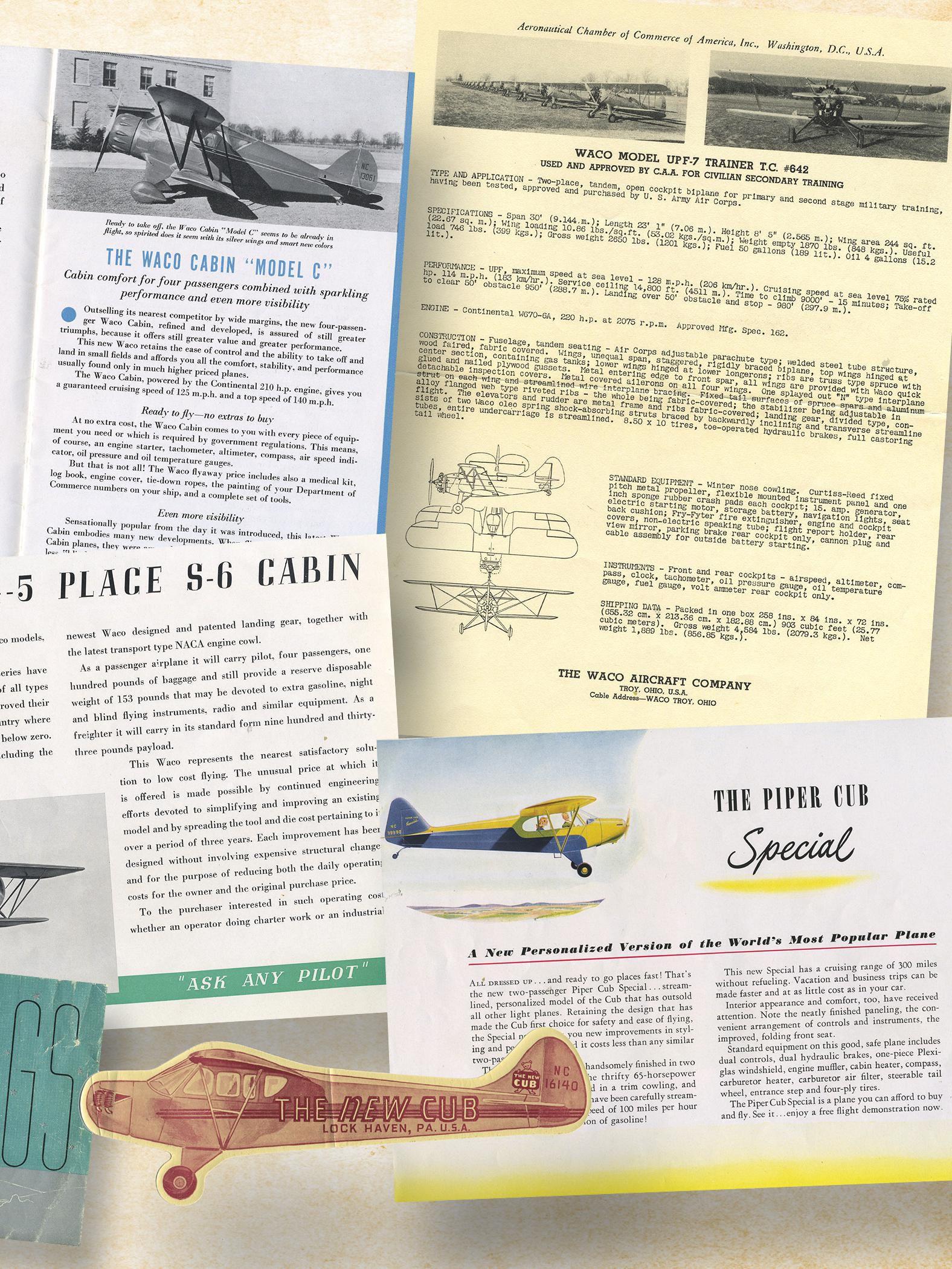

From the pages of what was ...

Take a quick look through history by enjoying images pulled from publications past.

SUSAN BEGAN FLYING AT the age of 15 on a private airport (Overton Field) located near her shared hometowns of Andrews and Pawleys Island, South Carolina. She earned her private pilot certificate during her senior year in high school and continued flying during her college years. Susan is a graduate of Francis Marion University with a Bachelor of Science in business administration and a graduate of FlorenceDarlington Tech with a degree in aviation maintenance technology. While in college, Susan earned her commercial, multiengine, instrument, and flight instructor certificates.

Susan is a longtime EAA and Vintage Aircraft Association volunteer and currently serves as the president of VAA Chapter 3. She is a director emeritus of the national EAA board of directors after serving 20 years in that position. Susan currently serves on the EAA board of directors as the current president of the Vintage Aircraft Association. She is a retired night freight pilot, having flown 25 years with ABX Air Inc. (formerly Airborne Freight Corp.).

KATHY WAS INTRODUCED TO aviation at age 3. Years later, she had her first ride in a Cessna 170, inspiring her lifelong passion for flying and vintage aircraft. Soon after, she purchased her own 1960 Cessna 150, which she flew to obtain her private pilot certificate. Kathy flew her C-150 to her first EAA convention in 1997, flying along with friends in a C-170 and a J-3 Cub. Camping in the Antique/Classic area, Kathy was parking airplanes the second day and has volunteered with Vintage every year since. Soon after receiving the Art Morgan Volunteer of the Year award, Kathy became a co-chairman of the Vintage Flightline Committee. Kathy works closely with Vintage and all other parking and leadership entities on the field every year to ensure safe and smooth operations throughout EAA AirVenture Oshkosh.

After attending board meetings during her time as chairman, Kathy was appointed as an adviser to the VAA board. Through the adviser position, with input from flightline chairmen, several key initiatives have been presented to the VAA board to improve flightline safety and membership parking during convention.

While managing her career in telecommunications, she completed her instrument rating and made many cross-country trips to Oshkosh, most recently with two other female pilots in her Navion L-17. She is working on her tailwheel endorsement in a recently acquired Piper PA-11.

Kathy’s and her husband’s love of flying has led to many adventures in their airplane.

Kathy still serves as vice chairman of Vintage Parking and Safety. Her passion for aviation has led to volunteer opportunities in the Denver area, at the Udvar-Hazy Center at the Smithsonian museum, and flying missions with her husband for Pilots N Paws. Kathy credits her love of aviation to the many Antique/Classic and Vintage members who came before her, and she strives to continue carrying this message to the next generation.

Susan owns and regularly flies a 1953 Cessna 180 from her home airport (Dusenbury Field), which is located on her farm in North Carolina, and is currently restoring a 1935 Stinson SR-6.STEVE WAS BORN IN ALBERT LEA, Minnesota, and grew up on a farm near there. Having a deep interest in aviation, he received his private pilot certificate in 1967. In 1975, he purchased a 1946 Navion from his father. After joining EAA in 1967 at Rockford, Illinois, Steve has attended 54 consecutive EAA conventions.

A charter member of VAA Chapter 13, Steve has served as vice president and president of that chapter. He served two years as an adviser to the Vintage board and later as a director. In 1991, he accepted the duties of secretary of the Vintage board of directors and served in that position for 29 years. He is now a director and is seeking another term. He recently retired from his position as chairman of the Tall Pines Café after more than 20 years of service.

In 2021, Steve had the honor of being named to the Vintage Aircraft Association Hall of Fame.

GROWING UP IN COLUMBUS, MISSISSIPPI, AC was eager to learn to fly from an early age. He financed his flying lessons by selling fireworks, driving a school bus (while still in high school!), and working at the local airport. While in college he earned his commercial, instrument, multiengine CFI and CFII certificates. He graduated from Mississippi State University with a degree in industrial arts education. After college, AC moved to Miami to fly Lockheed Electras and a Grumman G-1 before being hired by Delta Air Lines, where he enjoyed a 40-year career.

AC is a longtime EAA and VAA member and has restored a 1939 Taylorcraft, a 1946 Aeronca Champ, and a 1947 Stinson 108, as well as working on and owning several other vintage airplanes. He became an A&P mechanic in 1983 and later received his inspection authorization. The Hatz biplane he built won a Bronze Lindy in 2019.

It is important to AC to share the gift of aviation with young people. He was involved in the Candler Field Museum Youth Aviation Program (now known as the Ron Alexander Youth Aviation Program) as a mentor and flight instructor for

seven years. He and his wife, Sue, were the co-directors of that program for almost three of those years.

AC and Sue live on an airstrip near Griffin, Georgia, where he is restoring a Piper PA-15 Vagabond and has a 1945 Stinson L-5 project waiting for restoration.

GROWING UP IN A FLYING FAMILY at Sky Park Airpark in rural Jordan, Minnesota, Vaughn’s earliest memory as a child of 3 years old was a wing rib-stitching party hosted in his father’s restoration center in 1982. The project being rushed to make a fly-in was NC6906, a 1928 Laird LC-B200, aka the “Honeymoon Laird” that was once owned by Matty Laird himself, now owned and flown by Vaughn. Since then, he’s been hooked.

Vaughn is the third generation in the Lovley family with a pilot certificate, which he received in 1998. On the day he was born, his father, Forrest (VAA 2022 Hall of Fame inductee), purchased a Piper PA-11 (still in the family to date), which is the airplane Vaughn, his mother, younger brother, and numerous aviation friends have all learned to fly in. Since then, Vaughn has had the opportunity to solo 50 different vintage airplanes in type.

In addition to flying, Vaughn has also worked on many projects, including the restoration of a Mooney Mite with his father, which is still in the family; an Oshkosh award-winning Piper PA-15 Vagabond that he still owns; WACO Cabins; and currently a Luscombe 8A. In addition to the Laird and PA-15, Vaughn also owns a Waco Cabin that has been a yearly AirVenture gathering place for fellow antiquers, and an RV-8 that he uses to regularly travel to other fly-ins throughout the country. The airplanes are kept in his hangar at his home on the residential airport at Sky Harbor in Webster, Minnesota, and at his hangar at Le Sueur, Minnesota, where he helps host and coordinate Marginal Aviation’s annual First Ditch fly-in.

Over the years, Vaughn has worked in both the public and private sectors and thoroughly enjoys his employment and traveling as a director of sales and marketing at Lilja Corp., a general contractor based in California but working throughout North America. Ever the entrepreneur as well, Vaughn has been a successful nightclub DJ for going on 15 years, and

regularly fields phone calls from fellow enthusiasts looking for old airplanes or old airplane parts.

His experience in sales, branding, and marketing has carried over to many vintage aviation sectors to promote, fundraise, organize fly-ins, and grow interest with the younger generation. As one of the key members of Marginal Aviation, a stand-alone, independent, antique airplane organization in its own right based in Minnesota that was founded by friends and family in the 1970s, Vaughn has helped lead the charge in growth, serves as a trustee on the governing board, and has been instrumental in bringing it to its now status as a 501(c) (3) nonprofit with rapid national growth.

Vaughn wishes value, strength, and success across all aviation organizations and genres and is honored and excited to be a part of the VAA leadership. He looks forward to helping VAA and its members continue the heritage of vintage aviation, along with contributing to the growth of the organization.

For one week every year a temporary city of about 50,000 people is created in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, on the grounds of Wittman Regional Airport. We call the temporary city EAA AirVenture Oshkosh. During this one week, EAA and our communities, including the Vintage Aircraft Association, host more than 600,000 pilots and aviation enthusiasts along with their families and friends.

As a dedicated member of the Vintage Aircraft Association, you most certainly understand the impact of the programs supported by Vintage and hosted at Vintage Village and along the Vintage flightline during EAA AirVenture Oshkosh every year. The Vintage flightline is 1.3 miles long and is annually filled with more than 1,100 magnificent vintage airplanes. At the very heart of the Vintage experience at AirVenture is Vintage Village and our flagship building, the Red Barn.

Vintage Village, and in particular the Red Barn, is a charming place at Wittman Regional Airport during AirVenture. It is a destination where friends old and new meet for those great times we are so familiar with in our close world of vintage aviation. It’s energizing and relaxing at the same time. It’s our own field of dreams!

The Vintage area is the fun place to be. There is no place like it at AirVenture. Where else could someone get such a close look at some of the most magnificent and rare vintage airplanes on Earth? That is just astounding when you think about it. It is on the Vintage flightline where you can admire the one and only remaining low-wing Stinson Tri-Motor, the only two restored and flying Howard 500s, and one of the few airworthy Stinson SR-5s in existence. And then there is the “fun and affordable” aircraft display, not only in front of the Red Barn but along the entire Vintage flightline. Fun and

affordable says it all. That’s where you can get the greatest “bang for your buck” in our world of vintage airplanes!

For us to continue to support this wonderful place, we ask you to assist us with a financial contribution to the Friends of the Red Barn. For the Vintage Aircraft Association, this is the only major annual fundraiser and it is vital to keeping the Vintage field of dreams alive and vibrant. We cannot do it without your support.

Your personal contribution plays an indispensable and significant role in providing the best experience possible for every visitor to Vintage during AirVenture.

Contribute online at EAAVintage.org. Or, you may make your check payable to the Friends of the Red Barn and mail to Friends of the Red Barn, P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903-3086.

Be a Friend of the Red Barn this year! The Vintage Aircraft Association is a nonprofit501(c)(3), so your contribution to this fund is tax deductible to the extent allowed by law.

Looking forward to a great AirVenture 2024!

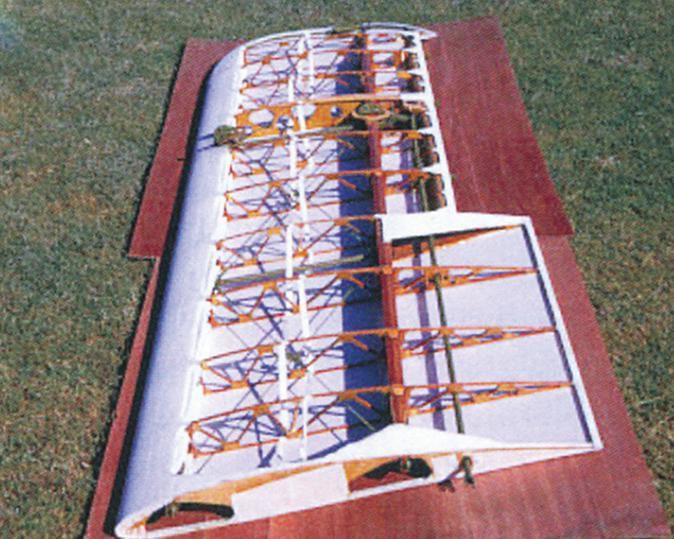

PREPARATION OF A STRUCTURE TO receive fabric covering requires some thought be given to sharp edges or overlaps that need to be covered with tape. And, depending on what type of fabric attachment is chosen, one may want to cover the leading edge metal with a polyester padding that will blend out surface irregularities such as skin overlaps.

I always cover any nail heads on the leading edge with a good grade tape — I particularly like to use “gaffer’s tape.” Gaffer’s tape has an adhesive that securely bonds it to an aluminum leading edge. Do that first before installing the polyester padding. Then inspect the rest of the structure, checking if there are any sharp edges that could penetrate and damage the fabric. I always put tape over trailing edge rivets. See Photo 1.

Polyester padding may then be installed on the leading edge of the wing by bonding it along upper and lower edges of spars. Do not attempt to bond the entire leading edge as the padding needs to be soft and pliable. Photo 1, gaffer’s tape covers sheet metal attaching screws on a leading edge, and a strip of polyester padding is ready to be bonded in place.

In Photo 2, the padding is bonded in place using manufacturer’s approved adhesive. The Champ wing chord is too wide to blanket cover the wing; therefore, three strips of fabric had to be sewn together so there was no need to glue fabric to the leading edge. Do not glue fabric to the padding; it won’t work.

Using this method of leading edge protection will lead to a very smooth covering job where skin overlaps and nail or screw heads cannot be seen. Whenever possible I always use padding on the leading edges and a few other places on occasion.

Photo 3 is a Bucker Bü-133 Jungmeister wing I covered many years ago for John Hickman. These wings were narrow chord, and the fabric could be blanketed in place and not require any machine sewing.

The upper Bucker Jungmeister wing was covered with the Ceconite process back in 1970. This wing is all wood construction, and the leading edge and other areas are covered

with padding. The fabric was installed around the leading edge and glued to the inside of the wing spar. A little preshrinking was done to tauten the leading edge and then it was coated with nitrate dope. Then the bottom of the fabric was bonded in place, wrapped all the way around the leading edge, and bonded to the area along the top of the spar.

What did the airplane look like when it was finished? Well, here it is in Photo 4.

Photo 2

Photo 3

Photo 4

Photo 2

Photo 3

Photo 4

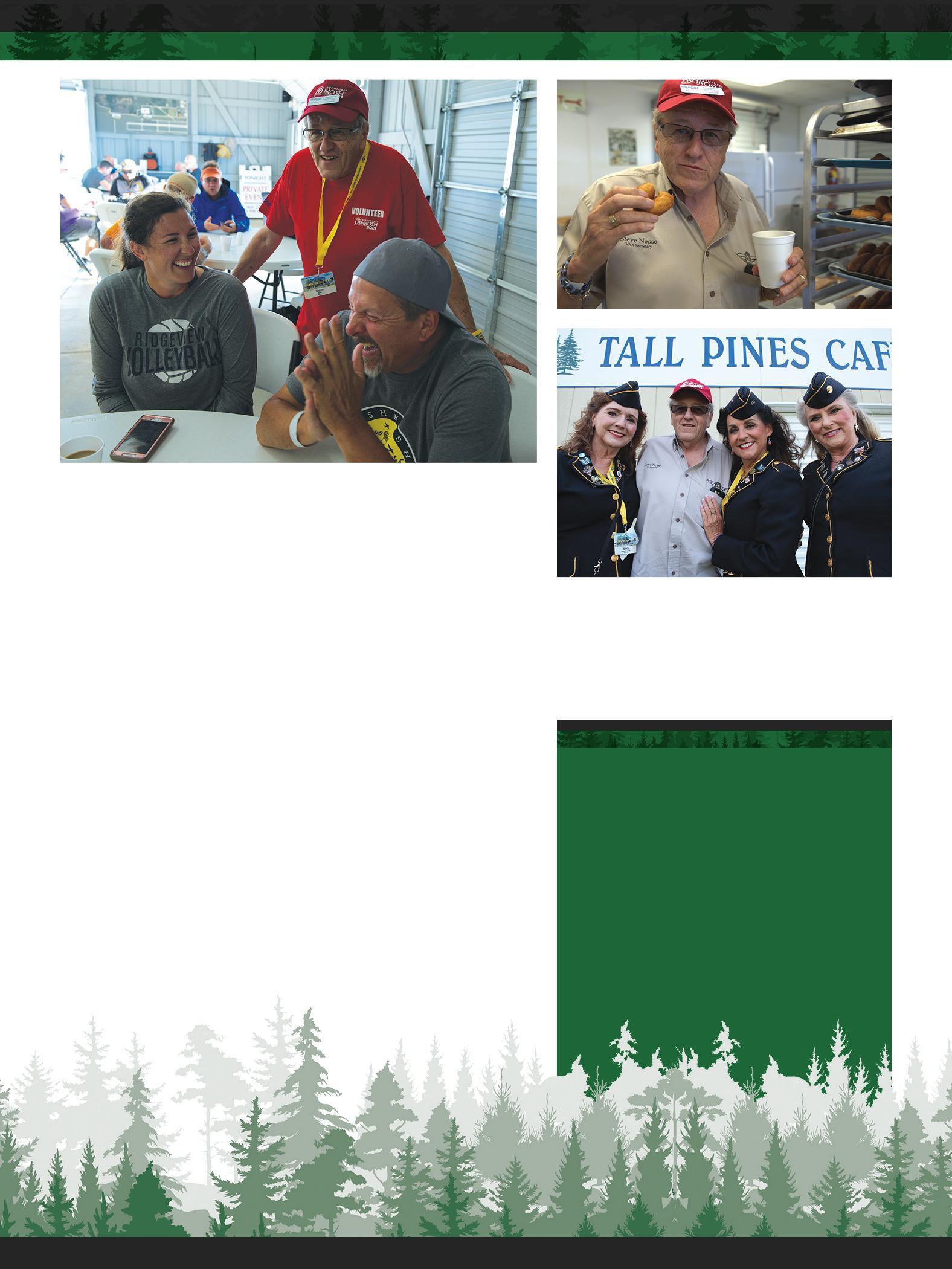

PICTURE THIS: THE ROAR of the morning P-51 formation just pulled you out of sleep. Usually, you hit snooze on your alarm, but there is no snooze button for the excitement of AirVenture. You unzip your tent, and the fresh smell of coffee and syrup calls your name.

Where is that heavenly smell coming from, you ask? The Tall Pines Café, of course! The breakfast café is operated entirely by EAA Vintage Aircraft Association volunteers, and all proceeds support VAA projects. So come on down and start your morning the right way: with hot food and good conversation with fellow aviation enthusiasts.

The Tall Pines Café got its start in 2002 when the south end of the AirVenture convention grounds was void of food vendors despite the growing camping population. The café started as just a tent pitched at the end of the Ultralight Runway along the tall pine trees — hence the name.

“Our goal for Tall Pines was to provide a food source for the people that were camping by their airplanes in the Vintage area,” explained Steve Nesse, Vintage 6490. “We had borrowed equipment when we started that first year, and we had about six picnic tables. We did the cooking and the serving in one small tent.”

Steve became the volunteer chairman for the Tall Pines Café in 2003 after John Berendt, the 2002 chairman, could no longer do so. This was meant to be a temporary arrangement, but Steve would carry the torch for 20 years. Another key figure since the first year is Sebastian Baumgardner, Vintage 717561, who is chairman of kitchen operations for the café.

Quickly, demand for breakfast grew, and the humble tent moved to its present-day location and turned into a permanent kitchen with outdoor seating in 2004. Further developments came just in time for AirVenture 2015 with a permanent concrete seating area covered by a

tent. So pleased with the new seating area, Vintage members and volunteers rallied together to fundraise and build a permanent dining pavilion.

Fast-forward to today, Wayne Wendorf, Vintage 719068, will be taking over the chairman administrative duties and is looking forward to serving even more guests with new hours and menu items for EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2024. “We chose to expand the hours because there’s people that are not early risers,” Wayne explained. The café opens bright and early at 6:30 a.m., and starting in 2024, will stay open and serve breakfast until 11 a.m.

“We do a lot more than pancakes, which is what we started out with,” Steve said. “We make our own doughnuts right on-site, probably in the neighborhood of 400-500 a day.” Also on the

Tall Pines Café is looking for volunteers who can spare two to three mornings during convention week to help prepare and serve meals, clean tables and dishes, and more. Email tallpines2023@gmail.com or inquire at the Volunteer Center outside the VAA Red Barn during AirVenture for more information.

menu are classic American favorites like biscuits and gravy, eggs and sausage, and French toast.

For those looking to cut back on carbs or just have a quick bite, new menu options are in the works for 2024. “We want to expand into some healthier choices and maybe some to-go choices so guests can grab what they want and go,” Wayne said.

The café is in a prime location for watching aircraft as you enjoy your food, and you can even catch a tram to take you there. Located on Wittman Road on the south end of the Vintage showplane area, combined with the open-air concept of the pavilion, you can enjoy watching aircraft arrive on the main runway and the morning activities on the Ultralight Runway.

In addition to the entertainment of aircraft activity, you’ll have a hard time leaving without seeing an old friend or finding a new one. “There’s always interaction at breakfast in the morning,” Wayne said. “[Seating] is first come, first served. I personally have sat down and met people from many different countries and many different walks of life. Aviation brings people together, but it’s really the people that make things work.”

Speaking of people making things work, the café continues to be operated entirely by volunteers as it has since 2002. If you want to further support VAA, consider spending a few extra hours at the café for a morning or three during convention week. “There are so many opportunities. Whatever somebody’s forte is, we can accommodate,” Wayne said. “None of [the work] is too difficult, and you can pick and choose your hours.”

“Tall Pines is really a close-knit group of volunteers, and everyone is very welcoming,” Wayne expressed. “Come and enjoy breakfast, watch what’s going on around, and meet new people!”

6:30 – 11 a.m. Monday through Friday (open Saturday depending on remaining supplies)

Biscuits and Sausage Gravy (includes eggs, fruit cup or applesauce, and beverage)

Pancakes or French Toast (includes eggs, sausage, fruit cup or applesauce, and beverage)

À la carte: Fresh doughnuts, granola bars, cereal, muffins, coffee, tea, hot chocolate, orange juice, and milk

Plus new items coming soon for AirVenture 2024!

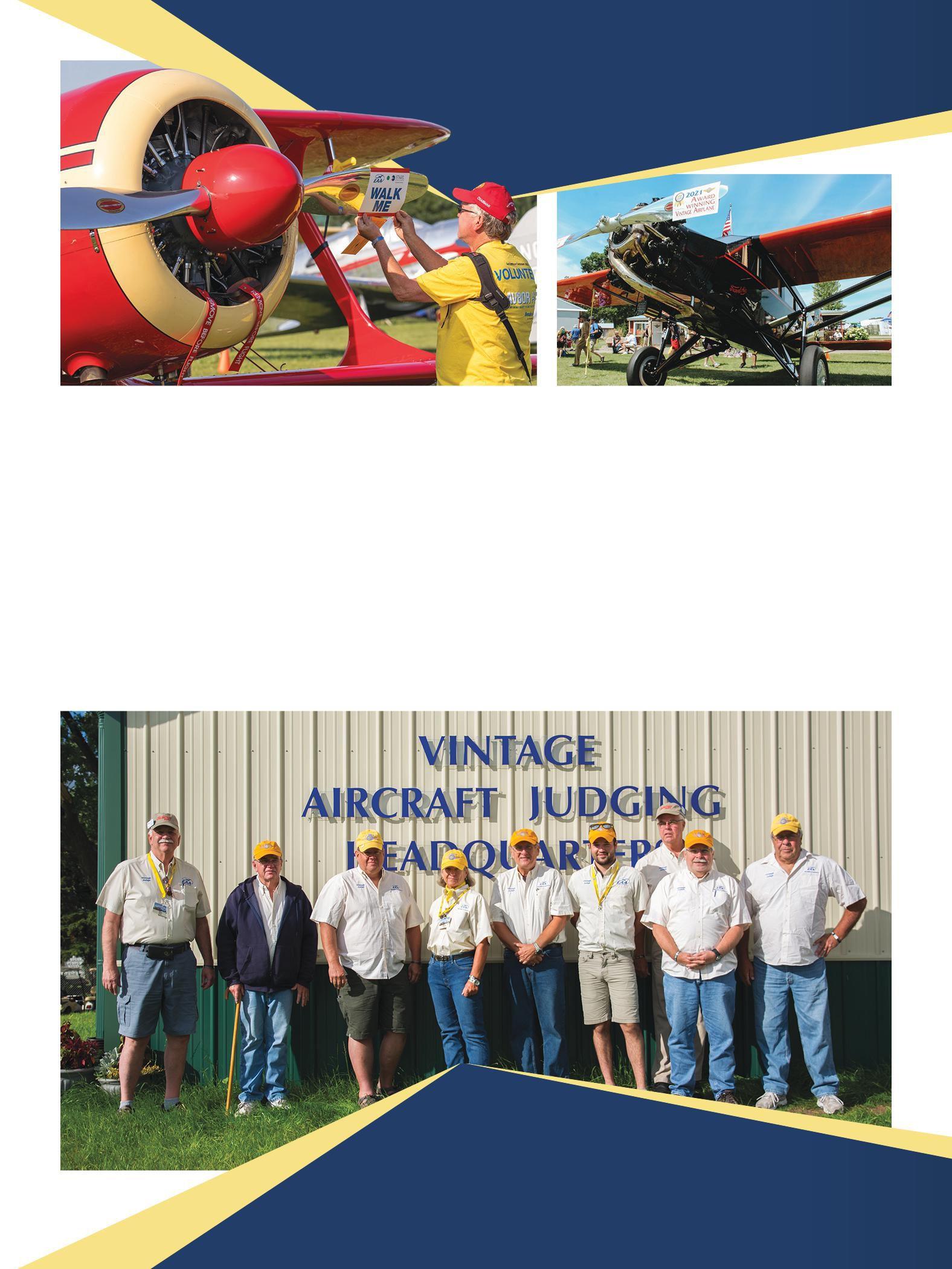

IF YOU’VE BEEN TO EAA AIRVENTURE OSHKOSH, no doubt you’ve noticed those folks who circle around an airplane, kneeling and peeking underneath the fuselage, pointing overhead at a wing, and musing among themselves and taking notes. They are the Vintage judges, and they’re easily identified by their collared shirts and gold-colored ball caps adorning their noggins. If you’ve wondered just what makes an award-winning aircraft, and how the judges go about the task of judging, then read on to discover the process, as shared and described by Vintage Aircraft Association Chief Judge Tim Popp.

But first, a few words about Tim, who hails from Sun City, Arizona. Tim started learning to fly in 1988, the same year he first experienced Oshkosh. He earned his private pilot certificate in 1989, and later added a tailwheel endorsement and an instrument rating.

“In 1994, I bought my first airplane — a 1958 straight-tail Cessna 172. I refurbished that and camped with it at Oshkosh for nearly 20 years,” Tim said. “I got into judging in the early 1990s when a friend of mine was judging. The judges needed a little bit of help with some computer work, and I started doing some of that. One thing rolled into another, and I’ve been judging for 25 years. I’m

going into my fourth year of being chief judge.”

We try to get the owners the best chance they can have at winning an award.

— Tim Popp

Tim’s allegiance to EAA and VAA has been virtually tangible through the decades. He previously served as president of EAA Chapter 221 (Kalamazoo, Michigan), has flown more than 500 Young Eagles, and finished building his RV-7 in 2012. That same year, he started serving on the VAA board of directors and is now a director emeritus.

It Isn’t ‘Who Dunnit’

Simply stated, it takes perseverance to restore an aircraft to judging standards. “Just about anybody who’s willing to learn how can do it,” Tim shared. “And then, it’s a matter of being willing to do the research and find out what the aircraft originally looked like. Bringing it back to that state may involve tracking down the right upholstery or matching the paint color to an area on the airplane that remained original. It involves walking down that pathway to uncover minor details.”

Notably, a passion for aviation and assiduous attention to detail play a tremendous role in most any restoration. “There are people who pay somebody to do the work because they don’t necessarily have the time or skills to do it. But they’re passionate about it, just as the people are who may not necessarily have the money to pay a restoration shop, but have the skills and enjoy the hands-on approach,” Tim said.

But judging isn’t about “who dunnit,” because the judging standards level the playing field. Hence, it makes no difference, in the judges’ eyes,

whether an individual or a professional shop did the restoration. It’s the authenticity of the aircraft restoration that’s being judged, not who did the work.

The judges look for aircraft that appear as though they’ve just come off the factory manufacturing line. Authenticity is essential, and points can be deducted for overdoing a restoration. For example, an owner may want a Cub to be finished with a glossy wet look, but if that’s not how the factory finished it, it will lose a few points. The same goes for modern instrumentation in place of the original; however, if the airplane is displayed with an authentic panel overlay concealing modern avionics, that won’t be a deduction.

“We’re looking for that pristine, factory-fresh authentic look, but we don’t deduct points for things that are safety related, such as changing old brakes to modern brakes. When an airplane is ‘over-restored,’ it may fall into a custom category. So the judges start with a score for the aircraft’s original details, and then the deduction points are subtracted from the total score,” Tim elaborated. “So if we see that an airplane does really good on our overall general judging, but then it has maybe 20 deduction points, we’ll take a look and see if it would do much better as a custom airplane. Then the deduction points don’t detract from the total. We try to

get the owners the best chance they can have at winning an award.”

When determining the authenticity of an aircraft restoration, the judges consult a variety of resources, which range from their own knowledge base to historical documentation provided by aircraft owners.

“Thankfully, our judges are of all ages now and certainly have a wide range of knowledge. A lot of times, we’ll have somebody that is kind of an expert on a type of airplane, and then we’ve got several reference books available from Cessna or Piper or Luscombe (or others) that we can consult,” Tim said. “We also rely a lot on the owners to document the originality and authenticity of their restoration by providing a presentation book and/or other types of documentation.”

Owners/restorers should document their restoration with images and notes, which can then be included in a presentation book. There isn’t a specific format for the book — it can be a three-ring binder or a digital document. Either way, it’s important to have the documentation available with the airplane during the convention. Images of the airplane before, during, and after restoration are helpful, along with a history of the airplane and/or previous owners, as well as copies of original sales brochures or aircraft/engine logbook pages with pertinent information. (Leave original documents at home, where they won’t be subjected to the weather!)

“It’s worth 5 points if you go to the trouble of making a presentation book,” Tim shared, “and those points can make all the difference in the world when it comes to receiving an award.” (For more details, see “The Judging Presentation Book” article by H.G. Frautschy at EAAVintage.org/ About-Us/Categories/Presentation.)

I think the VAA awards program encourages people to save these airplanes by restoring them as close to original as possible. If there were no awards, it would just be another fly-in.

— Tim Popp

Owners initiate the judging process when they register their airplane at either of the two camper registration locations in the Vintage area along Wittman Road and indicate they want their airplane to be judged. Hundreds of airplanes come and go throughout the week, and the judges diligently keep track of the airplanes that need to be judged via “vintage technology.”

“Believe it or not, we’re still using Palm Pilots for the judging program software. A couple of times a day, we’ll do a download from camper registration that populates our judging database and shows the airplanes we haven’t judged yet. Most of the judges will use a paper score sheet and then load the numbers in their Palm Pilots. That gets loaded into our database and gives us a total of every judge’s score so we can see which aircraft are at the top.”

Coming to EAA® AirVenture® Oshkosh™ 2024: Aeronca Nation, hosted by the Vintage Aircraft Association. Parking spaces are being reserved for Aeroncas and Champions, but spots MUST be occupied prior to Sunday night, July 21. After that empty spaces will be filled with other aircraft on a first come, first served basis with ABSOLUTELY NO EXCEPTIONS.

To park in one of these spots, you MUST BE PRE-REGISTERED. Parking volunteers will be checking the list and only parking those aircraft that have registered prior to arriving.

To register, email AERONCA.NATION.2024@gmail.com with the following information for each aircraft you plan to bring:

There are times when the judges know just by an airplane’s general appearance that it won’t be award worthy. But that doesn’t stop them from doing their job — in fact, it often becomes a learning opportunity.

“Sometimes, those are the owners that have just bought an airplane they love and want to restore. That gives us a chance to talk with them, and if they’re interested, we can share a copy of the judging standards with them as well. We always have a bunch of copies at the judges’ headquarters building, and it’s also available online. It details what we look for in a restoration and includes the standardized judging form.” (For more details, download the Judging Standards book at https://EAAVintage.org/ wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2017-Judging-Standards-Book-nosignature-1.pdf.)

Part of the judging goal is to have at least three judges look at each airplane, and they do their best to see each one as quickly as possible. Yet some aircraft leave the show before that can happen, whether due to weather or other factors. “Sometimes we see a really good airplane the first of the week, and by the end of the week, it’s still near the top, but it’s gone,” Tim said. “That makes it a little more difficult, when we can’t get all of the judges to look at the top contenders.”

While owners may feel they have to stay with their airplane until it’s been judged, they needn’t be tied down. The judges don’t expect people to sit by their airplane throughout the convention, waiting for the judges to come by. “We try to be accommodating, and our judges will go judge

airplanes without the owner present,” Tim said. “If it’s an airplane that looks like it’s going to be a contender, we will get a hold of those owners so the judges can look into the cockpit or open the engine cowling, because that’s not something that we will do without the owner there. So we encourage people to leave a cellphone number at their airplane or with camper registration so we can call and schedule a time with them.”

There are three Vintage judging categories: Antique (on or before August 31, 1945), Classic (on or after September 1, 1945, up to and including December 31, 1955), and Contemporary (on or after January 1, 1956, up to and including December 31, 1970). (A detailed list of Vintage awards is in the aforementioned Judging Standards book.)

There are literally hundreds of vintage aircraft that are judged, and they aren’t all necessarily parked in the Vintage area, though that would facilitate the judges’ work. Some aircraft may be at a commercial exhibitor’s booth, while others may be farther afield in the South or North 40, and the judges will still go see them.

“There’s usually around 40 antique airplanes that get judged every year, 120 or so classic airplanes, and there were close to 200 contemporary airplanes last year. The judges start judging Monday morning and stop at noon on Friday,” Tim said.

Tim’s role as VAA chief judge is basically coordinating the judging teams for the Antique, Classic, and Contemporary categories. “Each of those groups have a chairman and a vice chairman or co-chairman who run their respective team of about 10 judges,” Tim said. “As chief judge, I don’t judge airplanes anymore, but I make sure the chairmen in each category have what they need to get the job done. I handle the logistics of having enough

judging books and score sheets available, and working with computer ops to have the computer database running well.”

Individuals may apply to become a judge (the form is in the Judging Standards book), and judges are selected based in part on their knowledge level and hands-on experiences that will aid their ability to comply with the judging standards. Some may have completed at least one aircraft restoration, but they needn’t be an A&P or IA mechanic. Judging requires integrity, fairness, and an eye for details, and it isn’t for the faint of heart — the judges voluntarily devote six to eight hours a day to judging airplanes, whether under the sweltering sun or in cool, rainy weather.

The difficulty factor is one of the most challenging elements in the judging process. The judging teams are encouraged to discuss the difficulty factor and how they’re going to use it, so they’ll be consistent.

“For example, let’s say somebody restored a Piper Cub. One way of looking at that is that it’s easier than restoring a Beech 18,” Tim said. “Another way of looking at the difficulty factor is how extensive a restoration was. Did they take it all the way down to the airframe and build it back up, or did they give it a new coat of paint and fresh upholstery?”

Tim has been in meetings with the judges when they’ve debated how they want to use the difficulty factor. “It gets very interesting, because the opposite argument sometimes is, ‘Well, if you have two top-scoring airplanes and they’re both award winners, and one’s a Beech 18 and one’s a Cub … just because the Beech 18 is bigger and harder to restore, does that mean it’s always going to beat out the Cub?’ My philosophy is there’s no reason that Cub can’t beat a Beech 18. So we try to iron those things out at the beginning of the convention. Usually it doesn’t come down to 2 points, but when we have top contenders and dissimilar airplanes like that, then that discussion comes up even more.”

Fortunately, that situation seldom arises. But if it does, a “golf cart parade” may commence from the judges’ headquarters to the subject aircraft. “There may be 10 judges going out on four or five golf carts to go look at those airplanes again, and go over them in nitpicky detail,” Tim shared. “That difficulty factor is worth 5 points, and it’s probably the most subjective thing on that score sheet. It gets discussed every year.”

The judges do look at aircraft hardware, but contrary to one popular myth, slotted screws on an aircraft don’t have to all be lined up in the same direction. “They never came out of the factory that way!” Tim said and smiled. “But if Phillips-head screws have been substituted for PK screws that were originally used, that would be a deduct.”

Another misconception is that one must be a VAA member to have an aircraft judged. “You must be an EAA member. You don’t have to be a Vintage member, but we do encourage that,” Tim said. “Also, an aircraft has to fly during the convention. Whether it flies in, or gets trailered in and assembled and flown, doesn’t matter, but it has to fly during the convention to be eligible for an award. We understand that if you flew your airplane to Oshkosh, it won’t be perfectly spotless. But if there’s evidence you haven’t made an attempt to wipe away the oil or bugs, we may do a deduct for general appearance.”

Some folks may assume that part of the judging role is to ascertain airworthiness, but that’s not the case. The judges are focusing on authenticity, per the judging standards — so just because they judge an airplane, it doesn’t mean it’s airworthy. With that said, if the judges see a safety concern, they’ll politely pull the owner aside and mention it. That doesn’t happen often, but when it does, said Tim, “most owners are appreciative.”

The judges are often asked whether an aircraft can be judged in more than one category, and the resounding answer is “no.”

If the aircraft in question is an amphib, the judges will ask the owner whether they want it

judged in the Vintage category or as a Seaplane. Likewise, if it’s a warbird. (Each group has its own specific judging standards and judges.)

An aircraft can’t win the same award twice. It can only win a greater award; ergo, when an aircraft attains Grand Champion status, it’s at its pinnacle. The only award that a previous Grand Champion can garner is the Preservation Award, for being continually maintained in award-winning condition for a number of years (generally speaking, at least five years or more).

In the case of a previous award winner being sold to another owner, Tim said, “The fact that it just has a new owner doesn’t make it eligible for an equal or lesser award. It’s the aircraft that is judged, not the owner, so it can’t win any equal or lesser award to what it previously won.”

Elaborating further, Tim said, “However, if the aircraft was restored again, maybe after a mishap or something, then based on the extent of the restoration, it could be just like starting over, and the aircraft could be eligible for any award, even a lesser one.”

Another question that the judges occasionally hear is, “If I have the only ‘XYZ’ rare airplane on the field during the show, does that mean it will at least win the best-of-type award?” The answer, said Tim, “is ‘no,’ because it’s not just about being rare and being there. It also has to be in a quality condition that’s deserving of an award.”

The final tally of the judges’ score sheets seldom culminates with a tie. More often than not, there will be two aircraft within a few points of the other. When this occurs, said Tim, “The chairman of that group will ask all the judges to go back out and look at the close contenders, without the chairman’s input,” Tim said. “The chairmen know that each judge has an area of expertise, and while we try to eliminate any bias, there’s always going to be some. A lot of times we’ll use that as a learning experience, because there will be judges who are very familiar with, for example, Pipers, and the others might know Cessnas better. So it’ll be a chance for the Piper guys to share their knowledge with the Cessna guys. By doing that, the judges become more knowledgeable over the years, and more capable of judging categories of airplanes outside of their normal expertise.”

Tim’s 25 years of volunteering as a judge has been rewarding on a personal level, and it all boils down to the people aspect.

“It’s really about meeting and talking to the owners, and hearing what they’ve done and how they’ve come about learning to restore their aircraft. That’s really the cool part to me, because everybody’s got a story,” he shared. “Some of these people are putting their blood, sweat, and tears into restoring an aircraft, and the detail, craftsmanship, and money that they’re willing to spend in order to do it is just remarkable. Then there’s the everyday guy that’s just wanting a good flying airplane, and kind of wants it to look like it originally did. Or maybe he is customizing it a bit, and it’s what he enjoys doing and making a practical airplane for his

purpose. We do have people that come back year after year, and keep asking, ‘What can I do to improve, or did I do this wrong?’ And we’ll try to help people out as much as we can!”

The annual awards program provides an energizing incentive for authentic restorations, facilitating the fulfillment of the motto “Preserving Aviation History for Future Generations.” Perhaps the most far-reaching perk of having a standardized judging procedure in place to bestow a wide variety of awards is that everyone benefits. Relics and basket cases are continually being transformed into glorious living history for literally thousands to see, up close and personal. (Visit EAAVintage.org, and scroll down to find the 2023 award winners.)

Tim surmised, “I think the VAA awards program encourages people to save these airplanes by restoring them as close to original as possible. If there were no awards, it would just be another fly-in. I think we truly get the ‘best of the best’ airplanes at AirVenture, and if we didn’t give those awards, some of those people wouldn’t fly their airplanes to Oshkosh. So if it wasn’t for the award program, I don’t think we would have the quality of airplanes that we have here.”

BY BUDD DAVISSON

BY BUDD DAVISSON

FIRST, LET’S GET ONE thing clear: Evidence has proven that to many pilots Wacos are an undesignated form of a Schedule 1 drug. Wiki’s definition of Schedule 1 drugs is, “Drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” If you don’t believe airplanes, especially those with two wings, are narcotics, let us introduce you to Tony Caldwell, EAA 1067987, from Oklahoma City. He could easily be the poster child for aviation junkies everywhere.

“Although my dad was a pilot and had a couple vintage airplanes, I didn’t start flying until fairly late in life,” Tony said. “I took lessons in 1983, but I was just starting a real estate business and later a family, so I had no time and even less money. Then in 2009, my 14-year-old son thought he might want to want to learn to fly, so we took a discovery flight together at the local airport, and it was amazing! For me, it was like giving crack to a recovering addict! I immediately started flying every chance I got!”

It didn’t take long for the airplanes to add up.

“I began looking for a Piper Dakota or Cessna 182 on Trade-A-Plane and Controller, believing, as I told my wife then, ‘I’d never

need another airplane.’ When I said that, I meant it. However, I had no idea how serious my addiction was to become,” Tony said. “That became abundantly clear when I flew a Bonanza for the first time. In almost nothing flat, an F33A was in my hangar. Then an A36 Bonanza, a new Cirrus SR22, and ultimately a TBM 850 followed by a Piaggio Avanti II.

“However, I didn’t know what aviation addiction was until I saw my first Waco at SUN ’n FUN in 2010,” he said. “That got me looking all over the country for one. Eventually, my friend and fellow addict Les Banta and I bought one. It was a 1989 Waco Classic YMF-5. Eventually the Waco Classic was replaced by a Decathlon as we continued to experiment with taildraggers. That, however, didn’t last long.

“In 2017, I found myself thinking about Wacos again and another ‘friend,’ Barry Branin, recognizing that I was losing my battle with aviation addiction again, sent me literally all over the country looking at antique Wacos. Eventually, he sent me a photo of a 1934 UMF-3 that had been restored by Dave Allen in Coronado, California. It was gorgeous!

“In some ways, my wife is responsible for that one,” Tony said. “She saw me fixated on the photo and said, ‘You’ve been in mourning since you sold your Waco. Buy it!’ That’s a little amusing because she never flies in open-cockpit planes with me — but she also didn’t need to tell me twice!”

About a week later, Tony was in Coronado, and the instant he saw the UMF-3 in Dave’s hangar, he knew he was going to buy it.

“Dave’s detail work and craftsmanship was incredible! It took three and a half hours for us to walk from one side of the airplane to

the other, admiring 27 coats of hand-rubbed dope finish and Dave’s meticulous attention to detail,” he said. “It had taken him seven years and 12,000 hours to finish it in 2009, and it had flown only 100 hours since then. It was nearly perfect. By then, Dave and I were friends, and he agreed to sell me this amazing labor of love. However, I had one condition, which was that when the day came for my stewardship to end, he’d have the right to buy it back.

“Another friend, Doug Durning, who has sadly gone west, ferried the UMF-3 to Oklahoma City from Los Angeles for me, and, when I flew it for the first time, I instantly saw why the F series Wacos were

As is so often the case, a shared passion for old airplanes was the basis for a strong friendship.

— Tony Caldwell

such favorites and deserved the slogan ‘Ask any Pilot’ in the 1930s,” Tony said. “Where my original 1989 Waco Classic had nice flying qualities, it had put on a lot of weight compared to the antiques, and the landing gear geometry was changed. The UMF-3’s handling and landing qualities were a revelation. The controls on the F-3 are lighter, and with less weight, it climbs faster and is more nimble. It is so well balanced you can actually

stick your arms outside the cockpit and steer the airplane with your hands.”

A few years later, Tony found himself spending several months each year in Northern California with its beautiful weather.

“I decided to look for another Waco to fly while out there,” he said. “Since I already had a UMF-3, I decided to look for a UPF-7 or a QCF-2. My friend Barry advised me to look for a UBF-2 instead of a QCF-2, because the UBF has bigger tail feathers and would come out of a spin easier. However, since only a few F-2s had been built, and fewer restored, I was looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack.

“Sometimes the fates step in, and I accidentally found an old email from a 1933 UBF-2 owner who had been willing to sell years earlier. Not expecting much, I recontacted him. I was amazed and delighted to find he still owned it and was still interested in selling. A quick trip to Virginia, and another Waco was on its way to Rob Lock for a light restoration to bring it back to its full glory.

“A few months before finding the UBF-2, I had driven down to Wichita Falls, Texas, to look at a Stearman, and the owner told me about Rob Lock and his Waldo Wright’s Flying

Service, which is based in Lakeland, Florida. Rob is well known as a barnstormer who used to give biplane rides in New Standards when he wasn’t restoring airplanes. On the way home from Texas, I called him to talk about the Stearman, and we visited for over an hour. He was very knowledgeable, and I enjoyed our conversation, though I didn’t buy that plane.”

After Tony bought the UBF-2 a couple of months later, he called Rob to see if he’d be willing to address some cosmetic issues, and Rob agreed.

“Over the ensuing months, we became friends, as he worked on first one, then two of my Wacos,” Tony said. “Ultimately, he helped me buy a 1929 Travel Air B-4000, which he is right now restoring for me. Biplanes easily become habits! We visit frequently about all kinds of things and people connected to antique aviation. As is so often the case, a shared passion for old airplanes was the basis for a strong friendship.”

Rob Lock has been around aviation all his life. “I was brought up around vintage airplanes because my dad, Bob Lock, who was a mechanic in the Air Force and wrote articles for EAA’s Vintage [Airplane] magazine, owned and restored a Stearman,” Rob said. “Eventually, we restored an E-4000 Travel Air and two D-25 New Standards, which are monstrous five-place, open-cockpit biplanes (four in front) and were the basis of our barnstorming business. However, I was slow getting into that, and, at 6-foot-10, I found even a Stearman to be a little tight. The height is also why I didn’t get into aviation right out of school because, for just short of 10 years, I was a professional basketball player. First, with the Clippers, then in Europe.

It was restored exactly how it had left the factory and just like one of its first owners, British movie actor Brian Aherne, had it when he was flying it back and forth from Hollywood to Broadway in the 1930s.

— Rob Lock

“COVID pretty much shut down the barnstorming-ride business, by which time I had a shop and was seriously restoring airplanes. That’s when Tony and I got together on the UBF-2 project.”

Rob shared the UBF-2’s restoration details.

“This airplane was originally restored by Joe Fleeman, Lawrenceburg, Tennessee, in 2014, and his airframe work was museum quality,” Rob said. “The airplane’s restoration began with Forrest Lovely, then the Woods brothers, and finally Woody Woodward, who sent it to Joe Fleeman. There was almost nothing left to be done on the airframe. However, the years had their effect on the outside, and we had to disassemble the airplane to do a lot of detail work. For instance, the fabric tapes were bubbled up because the gases trapped in the dope comes out and wrinkles the tapes, so we ironed them back flat. A small detail but very noticeable.

“The windscreens were also showing their age, so we built new ones,” he said. “Also, the rudder pedals had heel brakes, which are uncomfortable for most pilots, so we had Kevin Kimble rebuild the pedals for toe brakes. This meant raising the seat 3 inches.

“We went over the engine with a microscope, both to make it totally reliable but also to make it look more original. Anything that looked out of place or worn was replaced. Hoses, clamps, wiring, etc. Everything!

“The wing finish was one of the biggest, most noticeable improvements,” Rob said. “The fuselage had been done in Ranthane, which glosses up well, but the wings were done in Poly-Tone, which is naturally a little flat. The wings looked out of place next to the high-gloss fuselage so, we resprayed them.

“One of the bigger pieces of work was the ring cowl,” he added. “It had been installed too tight too many times and was cracked in a number of places. We had Vaughn Lovely make a new

In case readers haven’t figured it by now, Wacoites speak in a foreign tongue — a code understood only by the faithful. However, buried in it are the names/titles of the mechanical characters in the fabled Waco legend. Through Waco words, the entire personality, makeup, function, and mission of each can be deduced. The applicable dictionary follows.

Aerofiles painstakingly assembled this information sometime in the distant past. The world thanks it for this. Visit it at Aerofiles.com. It has more for-free aviation history information than we deserve. So, let’s support it.

Aerofiles.com: That Waco Coding System

Ever a subject of contention, confusion, speculation, and bar-room brawls, Waco’s system of codifying its airplanes gets somewhat clarified courtesy of Jack Wilhelm of the Waco Historical Society; Ray Brandly, author of the definitive Waco book; and Aerofiles’ own Lennart Johnsson.

First letter = powerplant (engine codes)

Second letter = airframe design

Indicated specific drawings or design changes, varying considerably within individual models. Third letter = series

Suffix = remarks Dash number generally indicated first year of production.

125 = 125-hp Siemens-Halske

A = 220-hp Wright J-5

B = 165-hp Wright J-6-5

C = 225-hp Wright J-6-7

D = 150/180-hp Hisso A/E

G = 115-hp Curtiss OX-5, 100-hp OXX-6, 115-hp Tank

J = 330-hp Wright R-975

A = 330-hp Jacobs L-6MB

B = 175-hp Wright R-540

C = 250-hp Wright R-760

D = 285-hp Wright R-760-E1

E = 350-hp Wright R-760-E2

H = 300-hp Lycoming R-680-E3

I = 125-hp Kinner B-5

J = 365-hp Wright R-975-E1

K = 100-hp Kinner K-5

M = 125-hp Menasco C-4

O = 210-hp Kinner C-5

P = 170-hp Jacobs LA-1

Q = 165-hp Continental A-70

R = 125-hp Warner Scarab

S = 420-450-hp P&W Wasp Junior

U = 210-hp Continental R-670, 225-hp W-670-K, 220-hp W-670-6

V = 240-hp Continental W-670-M

W = 450-hp Wright R-975-E3

Y = 225-hp Jacobs L-4MB

Z = 285-hp Jacobs L-5MB

Lycomings were not used until model E in 1940. Kinner C-5 was only on two airplanes, and the 160-hp R-5 was never used.

A = Primary glider

B = Open types, 1932 and 1933

C = 1931 open types with P and Q engines (LA-1 and A-70)

D = 1931 cabin types

E = 1932 cabin types

G = C series closed types as from 1937

H = All D series

I = 1933 cabin types

J = 1934 cabin model with Wright engine

K = 1934 cabin models with Continental and Jacobs engines and standard cabin models from 1935

L = 1933 (last) A series

M = 1934 open types

N = 1930 open types

O = 1935 custom cabin with Continental and Jacobs engines

P = All open types from 1936

Q = 1936 custom cabin types and 1930 National Air Tour Special

R = 1939 E series

S = Straight-wing variants of basic model 10

T = Taperwing variants of basic model 10

U = 1935 custom cabin with Wright engines

V = All N series

Y = Version of the Taperwing with Wright R-975

X = Variant of the basic model 10 with OX-5 or OXX-6

A = Two-place with side-by-side seating, 1932 and 1933

C = All cabin models 1931-1935, and custom cabin models from 1936

D = Military series 1934-1937

E = Variants of the basic model 10 with OX-5 or OXX-6 and Executive cabin models from 1939

F = Tandem cockpit two- and three-place open models, 1930-1937

G = 1930 National Air Tour Special; two CRGs only, c/n 3349/3350

M = See second letter Y

N = Tricycle-gear cabin series 1937-1938

O = Open models 1927-1929

S = Standard cabin models 1936-1937

T = Model RPT; one only, c/n 6000

W = Postwar Aristocraft; one only, c/n 9600

Z = Primary glider

A = Armed variants of the D series

S = Used in 1935 to differentiate between the current versions of the earlier (or standard) cabin series and the newly introduced custom cabin series. It became the third letter in 1936; i.e., model YKS, introduced in 1934, was YKC-S and YKS-6 in 1936 (all were built under the same ATC).

1, 2, 3 = Used in 1935 to identify higher-powered versions of the Wright R-760, Jacobs, and P&W Wasp Junior engines. See first letters C, S, Y, Z, and second designation of D and E (e.g., S3HD-A, CUC-1, YOC-1).

6, 7, 8 = Used to indicate models introduced in 1936 through 1938; e.g., models UPF-7 and VKS-7, introduced in 1937, remained in production until the early 1940s, with the largest annual production of the UPF-7 being achieved in 1941.

one, and Jamie Lyons spent about a week polishing it.”

Rob said while he was working on the UBF-2, Tony sent him photos of his UMF-3.

“I thought it was beautiful! It was restored exactly how it had left the factory and just like one of its first owners, British movie actor Brian Aherne, had it when he was flying it back and forth from Hollywood to Broadway in the 1930s. By then, Tony had decided to take the UBF-2 to AirVenture and I suggested that he take the UMF-3, too! He asked me if I’d help get it ready.

“In truth, even though I spent months on the F-3, which was all minor nitpicking stuff, Tony knows when something is right and when it isn’t, so I spent a lot of time detailing things,” Rob said. “The bump cowl, for instance, was built up out of carbon fiber, and you could see the fiber weave through the paint. That took away from the perfection of the airplane, so we built up the coatings and made it look like an original aluminum

1923 = 6

1924 = 7; 8

1925 = 9

1926 = 9

1927 = 10; 125; 10-W/ASO; BSO; DSO

1928 = 10/GXE; 125; ASO; 10-T/ATO; BSO; CSO; CTO; DSO

1929 = ASO; ATO; BSO; CSO; CTO; DSO; GXE; JTO; JWM; JYM; KSO; LAJ; NAZ; RSO

1930 = BSO; CSO; CRG; CTO; HSO; HTO; INF; KNF; MNF; LAJ; NAZ; PSO; QSO; RNF

1931 = BSO; CSO; CTO; PCF-2; KNF; MNF; ODC; OSO; PDC; QDC; QCF; QCF-2; RNF

1932 = BBA; BDC; BEC; CSO; CTO; ENF; IBA; KBA; OBF; OEC; PBA; PCA; PBF; RBA; RCA; TBA; TBF; UBA; UBF; UBF-2; UEC

1933 = CHD; CMD; CSO; CTO; FGH*; JYO; PBF-2; PLA; UBF-2; UIC; ULA

1934 = CJC; S3HD; UKC; UMF-3; WHD-A; YKC; YKC-S; YKS-6; YMF-3; ZKS

1935 = CPF; CPF-6; CJC-S; CUC; CUC-1; CUC-2; S2HD; S3HD-A; UKC-S; UOC; UMF-5; YKC-S; YMF-5; YOC; YOC-1

1936 = AQC-6; CPF-6; CQC-6; DJC-S; DKS-6; DPF-6; DPF-7; DQC-6; EPF-6; EQC-6; SQC-6; UKS-6; UPF-6; VPF-6; YKC-6; YKS-6; YPF-6; YQC-6; ZKS-6; ZPF-6; ZQC-6

1937 = AGC-7; DGC-7; EGC-7; JHD-6; LPF-7; UGC-7; UKS-7; UQC-6; VGC-7; VKS-7; VPF-7; VQC-6; YGC-7; YGC-8; YKS-7; YPF-7; ZGC-7, ZKS-7

1938 = AGC-8; AVN-8/N; EGC-8; JHD; UPF-7; VKS-7; VPF-7; WHD; YKS-7; YPF-7; YVN-8/N; ZGC-8; ZKS-7; ZPF-7; ZVN-7/N; ZVN-8/N

1939 = AGC-8; AVN-8/N; EGC-8; JHD; UPF-7; VKS-7; VPF-7; WHD; YKS-7; YPF-7; ZGC-8; ZKS-7; ZVN-8

1940 = ARE; HRE; RPT; SRE; UPF-7; VKS-7; WRE; YKS-7; ZKS-7

1941 = ARE; HRE; SRE; UPF-7; VKS-7; YKS-7; ZKS-7

1942 = SRE; UPF-7; VKS-7F

1947 = W

Unknown/unspecified years = ICA; KCA; QNF; SFB; TCA; UCA; UCF; UDC

cowl. Then we had a local sign painter come in and hand-paint the pinstripes. A lot of work for a small detail.

“All the streamline fairings on the F-3 are aluminum, including the wheelpants and cuffs, as per original,” Rob added. “No fiberglass or plastic on this ship. We took all the instruments out and had them refaced to match the 1934 Pioneer instrument catalog. Tony gave me a three-page ‘punch list’ of items that he wanted addressed on the F-3. This was detailed down to the point where he wanted the orange silicone baffle material in the engine compartment changed to black. He also wanted all the external hardware on both Wacos replated to silver (cad 1) so they weren’t gold (cad 2). No gold hardware existed in 1934. Minor details, yes, but not to Tony.”

Dave Allen’s restoration of the 1934 UMF-3, which is the only UMF-3 flying, and which was gone through carefully and detailed by Rob Lock, won the Customized Aircraft Champion Bronze Lindy at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2023. The 1933 UBF-2 won Silver Age Champion Antique at SUN ’n FUN Aerospace Expo 2023 and Outstanding Open Cockpit Biplane at AirVenture 2023.

It’s worth noting that Tony Caldwell demonstrated how serious his Waco addiction had become at AirVenture 2023.

“By AirVenture ’23, I’d decided I’d like to try to collect the entire F series of Wacos,” Tony said. “Barry had helped me find a 1935 YMF-5 project, and so I knew I would need to eventually find a UPF-7 and an RNF. In the Waco line in Vintage at AirVenture, Ben Redmond was displaying an incredible UPF-7 that the Redmond company Rare Aircraft had restored. It was parked in line with us and was for sale by one of his clients. Another friend, Jared Calvert, finally convinced me to buy it. So, four down and one to go! I ended up with three out of 25 Wacos at AirVenture last year. I doubt I’ll ever do that again! However, I think I now view Wacos the same way you look at dirt. They aren’t making any more, so …

Some photos you just have to love! UMF-3 WACOs have no bad angles.

“Living part time in Calistoga, California, the last few years is what led to the purchase of the UBF-2. That meant I needed to find a hangar for it,” he said. “While looking for that, I saw about 5 feet of wing through a partially open hangar door at an airport in Sonoma. It belonged to a beautiful red 1936 YKS-6 Cabin Waco owned by John Reed. John and I became friends, and when he mentioned he’d like to sell it, I had a hard time saying no. It wasn’t an F, and I wasn’t looking for a Cabin. But John’s plane was a time capsule, and eventually I bought that, too. Luckily, Walt Bowe offered to sell me his hangar at Sonoma Skypark so I’d have a place to keep them. I’ve made a lot of wonderful friends in the California antique airplane community as a result of these beautiful planes and a shared passion for them.”

Tony added a note here about the help he had getting his Wacos to AirVenture.

“It takes a village to take two airplanes to Oshkosh,” he said. “Rob, Rob’s wife, Jill, took care of lots of coordination. Jared Calvert, who ferried planes from Virginia to Florida and Michigan, Oklahoma, and California. Clay Adams, who flew the F-2 in and out of Oshkosh so I could fly the F-3, and cleaned and prepped. Steve and Tina Thomas put us up at Poplar Grove while we got ready for Oshkosh. Jim Busha took deliveries at his house. Clay and Jared, who flew the planes for the photo shoot, etc. We’re grateful for all the help!”

The only question left to be answered in the Tony Caldwell Waco saga is which airplane(s) will he bring to Oshkosh next year? Inquiring minds want to know.

“Let’ssee…ifIhit Daytonaboutnoon, thensteersay310,I shouldmakeChicago atabouttwo-thirty. Plentyoftimetotake mynapandstilltake intheCubsgame.”

Earlyon,Ohiowasa

bigaviationstate:theWrightBrothers,JohnGlenn, EddieRickenbacker,DominicGentile,andofcourse GeneralBarnettOverbite,USAF,Retired,shown hereplanningacrosscountryearlyinhiscareer.

Very late inhisillustriouscareerhewanderedintothe unattendedcockpitofaBoeing737,satintheright seat,pushedthegearleverup,andproclaimedmost assertively “Bombsaway!” Bydesign,onlythenose gearcameup,causingpanic,screaming,andamad scrambleforthedoors.General Overbitewasthengentlyescorted tosomenicenewquarters.

BY SPARKY BARNES

BY SPARKY BARNES

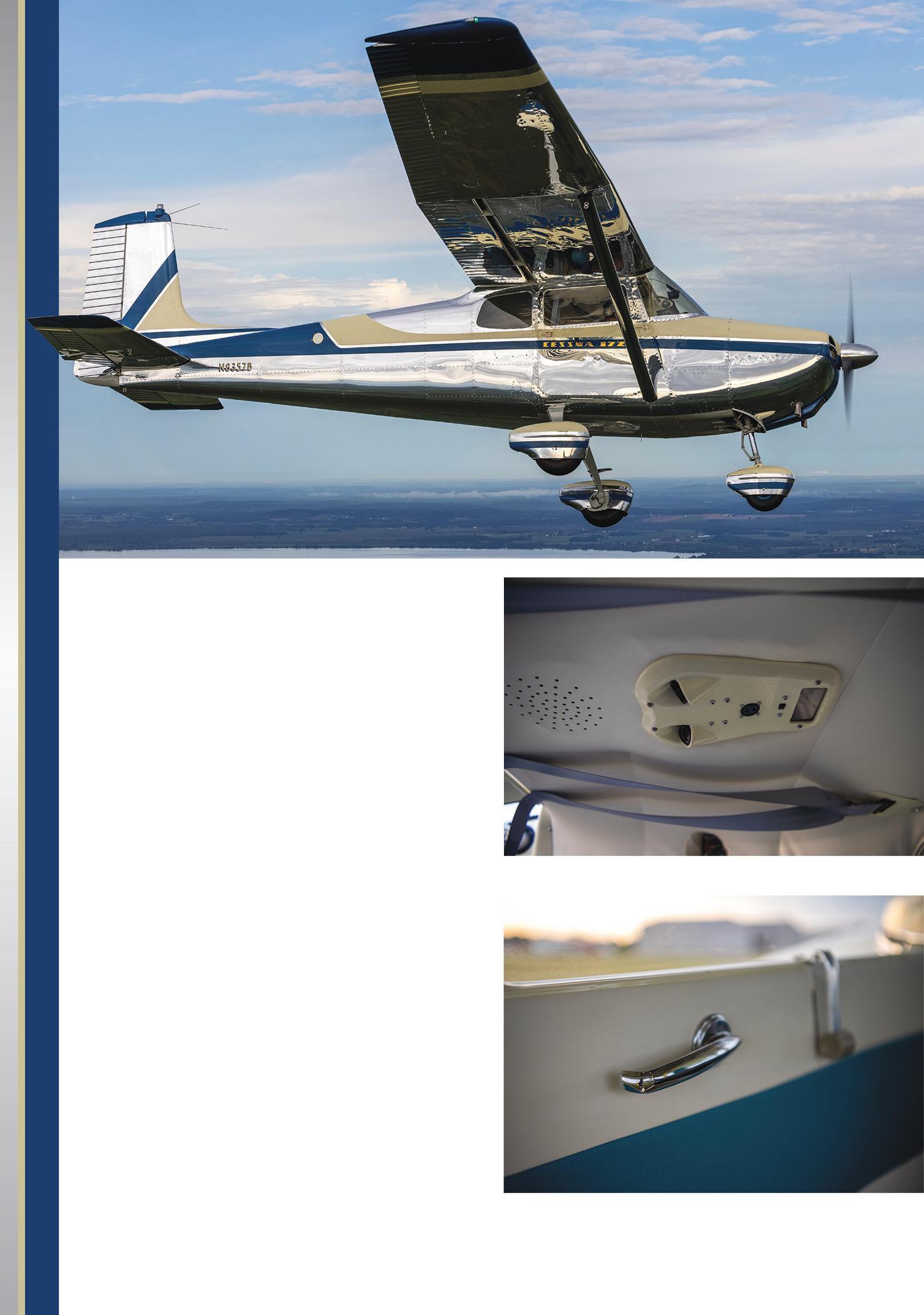

PAT HARKER OF FOREST LAKE, MINNESOTA, and his warbirds are a familiar sight at Oshkosh — among his fleet are a B-25 and a handful of L-birds. When he arrived in the Vintage area last summer with his gorgeous 1957 Cessna 172, it was a departure from his norm. His 172 wound up being a shiny showstopper and was crowned the Contemporary Grand Champion with a Gold Lindy. Pat relished every moment of relaxing with N8357B in the Vintage area and talking with admirers as they peppered him with questions about the restoration.

The nose-wheel-equipped 172 followed the tailwheel-equipped 170 in the Cessna family lineage and made its first flight in 1955. To date, there have been more 172s manufactured than any other airplane. In the late 1950s, the 172 gained fame and recognition when it achieved a remarkable historical milestone, thanks to a couple of young and resilient pilots. According to Guinness World Records, Robert Timm and John Cooke set an endurance record in their Cessna 172 (dubbed Hacienda). They departed from McCarran Field, Las Vegas, and landed there 64 days, 22 hours, 19 minutes, and 5 seconds later, “after covering a distance equivalent to six times round the world,” with groundto-air refueling.

Pat was mechanically inclined from an early age and has been around aviation since he was a youth building and flying models. “My dad had a Bellanca Viking, and he and my stepdad got along really well. They conspired to get into more aviation, and my stepfather bought a BT-13 project. I was 15 when I started working on it,” Pat said and chuckled. “I had no clue what I was doing!”

He started flying lessons at 17 and soloed in just eight hours’ time in a Cessna 152. But he took the

GENERAL SPECIFICATIONS

NOT ELIGIBLE TO BE FLOWN BY A SPORT PILOT.

WINGSPAN: 36 feet

LENGTH: 27 feet, 2 inches

HEIGHT: 8 feet, 11 inches

SEATS: 4

EMPTY WEIGHT: 1,260 pounds

GROSS WEIGHT: 2,200 pounds

ENGINE: 145-hp Continental O-300

TOTAL FUEL CAPACITY: 42 gallons (37 usable)

FUEL BURN: 8 gph

OIL: 8 quarts

MAX STRUCTURAL CRUISING SPEED: 140 mph

CRUISING SPEED: 118 mph

LANDING SPEED: 49 mph (with flaps)

CLIMB AT SEA LEVEL: 645 fpm

SERVICE CEILING: 13,100 feet

BAGGAGE CAPACITY: 120 pounds

winters off, so by the time he took his checkride, he’d logged 76 hours in a three-year span. Then he went off to study aerospace engineering at the University of Colorado at Boulder, but said he soon realized it was “too much space and not enough aero for my taste. It was engineering, and I think I’m more like an artist, because I’m good at visualizing what I want. I’ve got to go and get my hands dirty, which hurts me sometimes, but that’s just how I work.”

After a couple years of college, he left and attended Hennepin Tech in Minnesota, where he acquired his A&P certificate. He found his niche and loves it. Pat continually enhances his knowledge base by working hard and gleaning information from old books and visiting with other mechanics.

I already felt pretty good about it, but it’s awesome when you bring it here and get all that other feedback. It feels good; it really does!

— Pat Harker

His enthusiasm for flying and fixing airplanes is virtually tangible and has evolved significantly through the years. Devoted to the business he co-owns, C&P Aviation Services, Pat said, “We have eight full-time people in our hangar shop. I have two guys that are just maintenance, and the rest of us are more in restoration. I’m kind of a floater. I used to

be the paint shop, but that was a big bottleneck, so I finally hired a guy that paints. I’ve got one machinist, and he does all the CAD work and runs the CNC.”

In fact, their business location at Anoka County/ Blaine Airport (KANE) led Pat along the pathway to the Cessna project. Initially, Pat just wanted to buy the hangar right across the ramp from C&P, but it was home to the old 172. So the airplane became part of the purchase, replete with its decades-thick coating of dust and accumulated effluvium.

“Bert Marske had owned that hangar and 172 for a long time, and he’d passed away,” Pat said. “In January 2020, I connected with his daughter, who was willing to sell it all. The airplane had been sitting there for like 35 years, and the mildew and mold was unbelievable — it’d make your eyes water. It still had its original paint and interior, and when we started pulling panels off and looking inside the wings and fuselage, it was pristine. And it only had 2,100 hours on its original engine.”

As it turned out, the 172 was a hidden treasure, just begging to be restored. At first, Pat thought he’d just clean up the airplane a little bit and get it flying. But his

typical methodology got the better of him, and as soon as he polished a small section of the aluminum skin and saw how nicely it turned out, he was off and running on a full-scale restoration. He took the engine across the airport to Bolduc Aviation, and it brought the Continental back to airworthy condition. Meanwhile, Pat managed his regular maintenance work in addition to various phases of the Cessna’s airframe restoration.

He and his team completely disassembled the 172; fortunately, not much of the airframe needed to be reskinned. “We replaced the rudder skin, and there’s one strip on the belly between the lift struts that was caved in from sitting on something like a bucket of sealcoat — the little tangs had imprinted on the bottom of the airplane,” Pat recounted. “I had to replace that skin.”

Pat was able to dolly most of the other small dents and dings, with the exception of the left chin cowling. “You could see that someone had started it with the tow bar still attached — it had wrapped around and smashed the cowling, so we replaced one piece there. Otherwise, it is all original metal. Then of course, once we got it all painted,” Pat said and chuckled, “I could see I missed a couple of dings!”

The trim was painted with UNO (a BASF polyurethane coating), which Pat has been using successfully for years.

Get your EAA® AirVenture® Oshkosh™ wristbands and credentials mailed to you in advance with our Express Arrival program!

We’re committed to getting you onto the grounds as quickly and smoothly as possible.

Express Arrival is an exclusive benefit for EAA members, and tickets for AirVenture 2024 are on sale now!

Sponsored by

Purchase your tickets today at EAA.org/TICKETS

The 172 was sans wheelpants, but Pat finally located and acquired a new old stock pair for the main gear from Mark Holliday at a neighboring airport. The nose wheelpant was more elusive. Undeterred, Pat decided to make his own. He worked with the CAD member of his team to shrink the profile of a main wheelpant and make it fit the nose wheel fork and smaller tire. They paid particular attention to keeping some curve to it (as opposed to flat sides), in order to make it strong enough to prevent oil canning.

“He cut a tool out of a polyurethane foundry tooling board that had a density grade of 45 pounds per cubic foot,” Pat elaborated. “It’s just awesome for making this kind of tooling, because it machines really nice, and I can sand it if I want to slightly modify the shape of the tool. We made a male tool because it just used less material; otherwise, the tool is enormous.”

If you’re going to polish, you need to commit to it!— Pat Harker

To shrink the metal, Pat used an Eckold power shrinking tool, which has no-mar fiberglass jaws. “The jaws don’t chew up the metal at all; they leave it pretty smooth, so you can work pretty fast with it. When you lay that flat aluminum on the tool, the center of it is the highest point,” Pat explained. “That metal isn’t going to get moved, but you have to shrink the rest of the metal down around your tool.”

Bear in mind that Pat’s shop is rather uniquely equipped and has a 400-ton hydraulic press, which he used for the initial forming. “I’ll lay a box with polyurethane rubber inside the press, and as it comes down it will press and form around that part. When you’re using a male tool, you’ll end up getting all these wrinkles, and if they buckle on you, then you’re done, and you have to start over. Where the wrinkles appear is where I have to start shrinking it down until I get it real close,” Pat said. “Then I finish up with a body hammer and

hammer it all down. The wheelpants only make the airplane fly about 3 mph faster, but it looks like it’s going a lot faster!”

The question du jour for Pat, after people noticed that even the aluminum seams and rivet edges were gleaming, was, “How did you get it so clean and polished?”

Sharing the details of his own process, Pat said, “I start going over it with an airway buff, which is a big, pleated cotton wheel. I use a 4.5-hp DeWalt 7-1/2-inch grinder that turns about 5000 rpm — it’s an animal, and you really have to hang on to it. That’s how I can get it so clean; if you hit it with a dualaction sander, you’ll never get it all cleaned out. I use an untreated wheel so I don’t get too aggressive, and a Tripoli round wax bar. I’ve learned there are a lot of different grades of Tripoli bars; some are drier and more waxy, and some are more aggressive. Physically, that’s the hardest part of the polish job; it’s just exhausting. If you’re going to polish, you need to commit to it!”

He’d learned that it’s best to start with the coarse grit, as opposed to skipping that step and starting with medium or fine grit. “Then you work your way up. Otherwise, you won’t see the spot you missed until you get to that final polish, and then you’ll have to start over. I’ve learned that discipline the hard way, when working on the L-13. I polished that thing four times over,” Pat said and chuckled. “I had a lot of time to think about better ways to polish while working on it, so I’d get to the end and decide to try another method!”

Highlighting a few of his favored techniques, Pat elaborated that after using the Tripoli with a long-stroke automotive dual-action sander — which can leave little scratches if one isn’t careful — he can switch over to a rouge using a softer pad on that same machine. “I figured out that I want a longer stroke with the coarser grits; it’s just more aggressive and works faster. Then I switch over to using a synthetic wool pad, like a 6-inch buffing pad on that machine with Nuvite F7,” Pat shared. “The real trick for me was using a little spritzer of mineral oil, which keeps it all wet. It makes an ungodly mess, because you just get this oily stuff and black grunge everywhere! But it kind of lubricates everything, so it polishes much faster and more uniformly without all the swirl marks. Otherwise, if you just put a little polish on the pad and go until it’s dry, sometimes you’ll get a little dry nugget of polish that scratches everything back up again. So now I use the mineral oil and Nuvite F7, then a Nuvite FC dry, and then I do Nuvite C and switch to a different pad.”

Pat stressed the importance of segregating the polishing rags and pads in order to keep everything clean while working up through the various grades of polish. He finishes the job with Flitz, which is a creamy polish that wipes off easily. “I call it ‘fault finder,’ because you don’t see all the stuff you miss until you get to that final step.”

But wait, there’s more! After all that intensive labor to give the 172 its coruscating brilliance, Pat wanted to make sure it would stay that way as long as possible. He uses the John’s

360° ceramic two-part coating system. “It’s kind of a particular process to install that ceramic, but I think it’s worth it. You can feel it when you put it on; all of a sudden where it was kind of sticky, it feels slick like glass. It’s incredible, and of course the funny thing is, once you put that ceramic on, if you think you’re going to get tape or paint to stick to it, it won’t! The tape or paint will just fall on the floor,” Pat said and chuckled. “I learned that the hard way!”

Pat and his team retained the original doors and seats when they disassembled the airplane, and created a custom interior that is an artful expression of form and function. Designed with comfort in mind, the new upholstery complements the exterior finish. The gold vinyl accent trim was a finishing touch to gild the cream and blue original-style paint scheme.

The seats are upholstered in gray with a decorative blue pattern, and the safety belt system features B.A.S. shoulder harnesses and buckles.

Pat consulted with the upholsterer for guidance on the fabric, design, and colors. “He has the expertise in that area, and he had a lot of input on which materials to use and how it looks,” Pat said. “I’ve had a lot of luck collaborating with people on projects, within reason. I try not to get hung up on too many

details that have to be done ‘my’ way; I can just stick with a few of those and be flexible about the other parts of the airplane. You don’t have to have it all your way, as long as you get a little bit, right? In the end, you get a really nice product.”

Speaking of the interior, the airframe has been painted inside (wherever possible) to protect it from corrosion. “That airplane’s going to stay nice for a long time now,” Pat said. “Essentially, for me, it wasn’t about being totally original. It was about building a really nice airplane.”

Pat is an old-school type who prefers round gauges in his panel, partly because he finds it easier to quickly scan analog indicators than decipher numbers displayed on digital gauges. Then he discovered the Garmin GI 275, which depicts both graphical and digital electronic displays, and can be flush mounted in a standard 3-1/8-inch round opening. Voilà ! Here, he thought, was an aesthetically pleasing and practical way to blend vintage and contemporary instruments while giving the panel an impressive upgrade.

“I was always one of those guys who thought, ‘Why do people always spend all that money on their panels?’ Well, I finally figured that out — since I was restoring the airplane, I wanted it to be usable for a long time. I kind of threw the book at it, as much as you could with a 172,” Pat said and chuckled. “I got the GI 275s and EIS engine monitor — which is really overkill on a Continental O-300, but why not? The Aera 660 is in the center of the panel, and I have two comm radios.

It’s good to have that in case we do some training in it, and it’s got a nice audio panel with Bluetooth so I can listen to my music.”

Pat’s overarching goal with the restoration was to make a reliable airplane that he could enjoy sharing with his family, since some of his warbirds aren’t especially “family friendly” for youngsters. Surprising himself a bit, he discovered that he just loves flying the 172. Since it’s an early model, the flaps are operated with a Johnson bar, and when fully extended to 40 degrees, they’re highly effective.