AS YOU ARE READING THIS, EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2023 is in the history books. As I write this, AirVenture 2023 is in our future. Today we are all intoxicated by promise as we make our plans to attend aviation’s most enchanting event.

Upon arrival in the Vintage area during the fly-in, I think it’s safe to say the majority of our members and guests do not consider the behind-the-scenes work done by VAA volunteers to prepare for this one-week aviation extravaganza. Vintage has more than 600 volunteers, many of whom arrive months in advance to prepare the Vintage area for AirVenture arrivals. Whether the time contributed is one hour or a thousand hours, all of the time goes toward making the Vintage Aircraft Association the premier organization that it is. And some volunteer for an hour or two every year, while others volunteer for more than 1,000 hours annually.

Our grounds chairman, Dennis Lange, is one of our year-around 1,000-hour volunteers. The condensed description of his volunteer work would be this. Dennis will seed and fertilize the grounds around Vintage Village in the fall months following the fly-in as well as prepare all of our equipment for winter storage, which includes the removal and proper storage of batteries from the 28 vehicles (I could be a vehicle or two off here on that number!) that Vintage owns and operates. He monitors our buildings during the winter and will make minor repairs or make arrangements for repairs that require special skills or tools. In the spring he is back on the grounds mowing or going over the aircraft parking grounds with a roller. He’s also the guy who puts out the marker cones at the ends of the aircraft parking rows.

In fact, Vintage volunteers are putting out those cones as I write this letter. These cones, by the way, serve an important function. They are actually used as locators during an emergency. These cones will be removed by Dennis and other volunteers after the EAA AirVenture Oshkosh Notice ends.

Vintage has more than 600 volunteers, many of whom arrive months in advance to prepare the Vintage area for AirVenture arrivals. Whether the time contributed is one hour or a thousand hours, all of the time goes toward making the Vintage Aircraft Association the premier organization that it is.

About that same time, another group of Vintage volunteers will be removing everything that is left by fly-in attendees. That includes things like lawn chairs, coolers and even tents that either end up in the landfill or as a donation to a local charity. At the close of the fly-in all of our buildings and equipment are cleaned and prepared for winter. Any necessary repairs are made in the fall.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 64

September/October 2023

STAFF

Publisher: Jack J. Pelton, EAA CEO and Chairman of the Board

Vice President of Publications, Marketing, Membership

and Retail/Editor: Jim Busha / jbusha@eaa.org

Senior Copy Editor: Colleen Walsh

Copy Editors: Tom Breuer, Jennifer Knaack

Proofreader: Tara Bann

Print Production Team Lead: Marie Rayome-Gill

Advertising Manager: Sue Anderson / sanderson@eaa.org

Mailing Address: VAA, P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903

Website: EAAVintage.org

Email: vintageaircraft@eaa.org

Phone: 800-564-6322

Visit EAAVintage.org for the latest information and news.

Current EAA members may join the Vintage Aircraft Association and receive Vintage Airplane magazine for an additional $45/year.

EAA membership, Vintage Airplane magazine, and one-year membership in the EAA Vintage Aircraft Association are available for $55 per year (Sport Aviation magazine not included). (Add $7 for International Postage.)

Foreign Memberships

Please submit your remittance with a check or draft drawn on a United States bank payable in United States dollars. Add required foreign postage amount for each membership.

Membership Service

P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903-3086

Monday–Friday, 8 AM—6 PM CST Join/Renew 800-564-6322 membership@eaa.org

EAA AirVenture Oshkosh www.EAA.org/AirVenture 888-322-4636

Nominate your favorite vintage aviator for the EAA Vintage Aircraft Association Hall of Fame A great honor could be bestowed upon that man or woman working next to you on your airplane, sitting next to you in the chapter meeting, or walking next to you at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh. Think about the people in your circle of aviation friends: the mechanic, historian, photographer, or pilot who has shared innumerable tips with you and with many others. They could be the next VAA Hall of Fame inductee — but only if they are nominated.

The person you nominate can be a citizen of any country and may be living or deceased; his or her involvement in vintage aviation must have occurred

between 1950 and the present day. His or her contribution can be in the areas of flying, design, mechanical or aerodynamic developments, administration, writing, some other vital and relevant field, or any combination of fields that support aviation. The person you nominate must be or have been a member of the Vintage Aircraft Association or the Antique/Classic Division of EAA, and preference is given to those whose actions have contributed to the VAA in some way, perhaps as a volunteer, a restorer who shares his expertise with others, a writer, a photographer, or a pilot sharing stories, preserving aviation history, and encouraging new pilots and enthusiasts.

To nominate someone is easy. It just takes a little time and a little reminiscing on your part.

• Think of a person; think of his or her contributions to vintage aviation.

• Write those contributions in the various categories of the nomination form.

• Write a simple letter highlighting these attributes and contributions. Make copies of newspaper or magazine articles that may substantiate your view.

• If at all possible, have another individual (or more) complete a form or write a letter about this person, confirming why the person is a good candidate for induction.

We would like to take this opportunity to mention that if you have nominated someone for the VAA Hall of Fame, nominations for the honor are kept on file for three years, after which the nomination must be resubmitted. Mail nominating materials to: VAA Hall of Fame, c/o Amy Lemke VAA P.O. Box 3086 Oshkosh, WI 54903

Email: alemke@eaa.org

Find the nomination form at EAAVintage.org, or call the VAA office for a copy (920-426-6110), or on your own sheet of paper, simply include the following information:

• Date submitted.

• Name of person nominated.

• Address and phone number of nominee.

• Email address of nominee.

• Date of birth of nominee. If deceased, date of death.

• Name and relationship of nominee’s closest living relative.

• Address and phone of nominee’s closest living relative.

• VAA and EAA number, if known. (Nominee must have been or is a VAA member.)

• Time span (dates) of the nominee’s contributions to vintage aviation. (Must be between 1950 to present day.)

• Area(s) of contributions to aviation.

• Describe the event(s) or nature of activities the nominee has undertaken in aviation to be worthy of induction into the VAA Hall of Fame.

• Describe achievements the nominee has made in other related fields in aviation.

• Has the nominee already been honored for his or her involvement in aviation and/or the contribution you are stating in this petition? If yes, please explain the nature of the honor and/or award the nominee has received.

• Any additional supporting information.

• Submitter’s address and phone number, plus email address.

• Include any supporting material with your petition.

For one week every year a temporary city of about 50,000 people is created in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, on the grounds of Wittman Regional Airport. We call the temporary city EAA AirVenture Oshkosh. During this one week, EAA and our communities, including the Vintage Aircraft Association, host more than 600,000 pilots and aviation enthusiasts along with their families and friends.

As a dedicated member of the Vintage Aircraft Association, you most certainly understand the impact of the programs supported by Vintage and hosted at Vintage Village and along the Vintage flightline during EAA AirVenture Oshkosh every year. The Vintage flightline is 1.3 miles long and is annually filled with more than 1,100 magnificent vintage airplanes. At the very heart of the Vintage experience at AirVenture is Vintage Village and our flagship building, the Red Barn.

Vintage Village, and in particular the Red Barn, is a charming place at Wittman Regional Airport during AirVenture. It is a destination where friends old and new meet for those great times we are so familiar with in our close world of vintage aviation. It’s energizing and relaxing at the same time. It’s our own field of dreams!

The Vintage area is the fun place to be. There is no place like it at AirVenture. Where else could someone get such a close look at some of the most magnificent and rare vintage airplanes on Earth? That is just astounding when you think about it. It is on the Vintage flightline where you can admire the one and only remaining low-wing Stinson TriMotor, the only two restored and flying Howard 500s, and one of the few airworthy Stinson SR-5s in existence. And then there is the “fun and affordable” aircraft display, not only in front of the Red Barn but along the entire Vintage flightline. Fun and affordable says it all. That’s where you can get the greatest “bang for your buck” in our world of vintage airplanes!

For us to continue to support this wonderful place, we ask you to assist us with a financial contribution to the Friends of the Red Barn. For the Vintage Aircraft Association, this is the only major annual fundraiser and it is vital to keeping the Vintage field of dreams alive and vibrant. We cannot do it without your support.

Your personal contribution plays an indispensable and significant role in providing the best experience possible for every visitor to Vintage during AirVenture. Contribute online at EAAVintage.org. Or, you may make your check payable to the Friends of the Red Barn and mail to Friends of the Red Barn, P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903-3086.

Be a Friend of the Red Barn this year! The Vintage Aircraft Association is a nonprofit501(c)(3), so your contribution to this fund is tax deductible to the extent allowed by law.

Looking forward to a great AirVenture 2024!

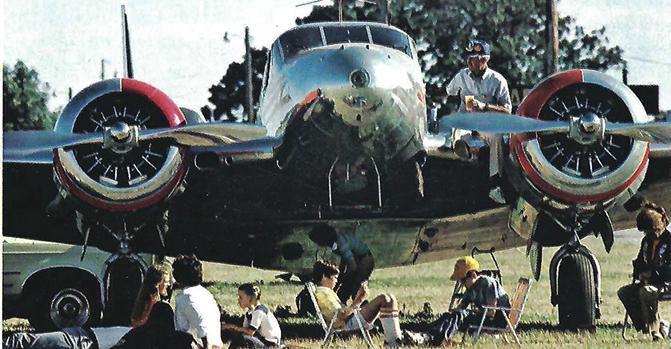

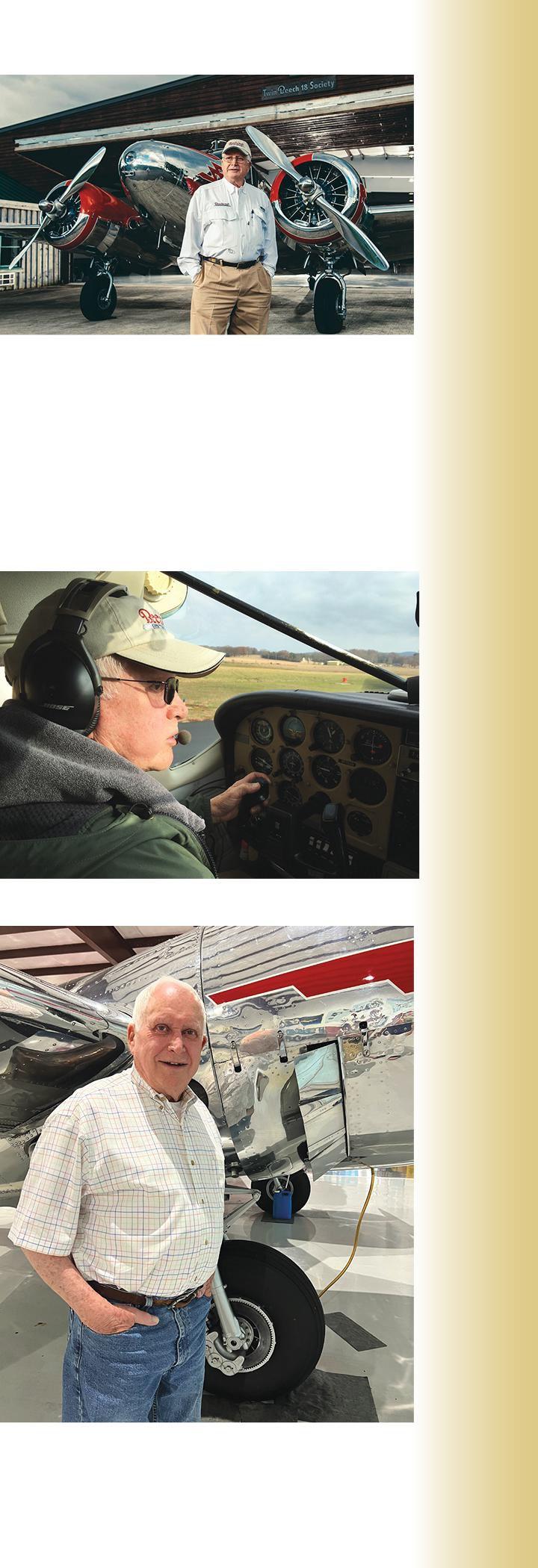

EAA BOARD MEMBER EMERITUS John Parish Sr., EAA 43943, grew up in Tullahoma, Tennessee, just a few short blocks from a World War II B-24 base, and he was enamored by the aviation activities there, which triggered him to start taking flight lessons when he was in high school and complete them while attending Vanderbilt University. In 1964, John bought his first airplane, a Cherokee 180. Two years later he replaced the Cherokee with a Comanche 260 and then a Twin Comanche.

John’s aviation interest flourished into a lifetime of aviation and a passion to preserve its history. He began attending fly-ins across the country including the Antique Airplane Association (AAA) gathering in Ottumwa, Iowa. It was at the AAA event that John fell in love with a

Beech Model 17 Staggerwing. He said it was the prettiest airplane he had ever seen, and his favorite color is red. The nickname for this G17S is Big Red, and John had the opportunity to purchase his dream airplane in 1970. His sons own it now.

The 1960s and ’70s were busy decades for John. Founder of the Parish Aerodrome with two grass strips adjacent to the Tullahoma Regional Airport, John, along with local aviation friends, hosted many fly-ins, calling them “happenings,” in Tullahoma. Pursuant to the many years of successful “happenings,” EAA partnered with John and his aviation colleagues to host an EAA regional fly-in that attracted as many as 35,000 people in 1979 and 1980.

Being a Staggerwing enthusiast, John became involved with the international Staggerwing Club. Every five years Beech Aircraft Corp. in Wichita would host the annual Staggerwing Fly-In. John made many aviation friends and had a great opportunity to become a friend of Mrs. O.A. Beech. In 1973 John’s vision to preserve the Staggerwing model came to fruition. His wife, Charlotte Parish, donated land to build and establish the Staggerwing Museum Foundation. John put his heart and soul into the project, and the museum that began as a two-room log cabin and hangar evolved into a 78,000-square-foot, fully

climate-controlled world-class general aviation museum. It now does business as the Beechcraft Heritage Museum, exhibiting 38 unique aircraft dating from 1924 to present and celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. Mrs. Beech’s family is still involved with the museum today.

John’s aircraft ownership has included a variety of aircraft: a Travel Air 4000; Travel Air Mystery Ship; Waco RNF; five Staggerwings; a Stearman; J-3 Cub; a Cessna 206 on floats; and a Beechcraft Duke, Baron, and Bonanza that was bought for his corporate travel and later replaced with a King Air C90 that the family continues to use today. His three sons, Charles, Robert, and John Jr., had the pleasure of flying his 1952 twinengine Beechcraft D18S to EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2023.

John’s leadership in the aviation community has included serving on the EAA board with specific interest in the VAA division for 30-plus years, and he had a leadership role as past director and vice president of the EAA Aviation Foundation. He was past president and vice president of the Tennessee Aeronautics Commission and a recipient of the Wright Brothers Master Pilot Award. John has contributed columns and has been recognized in many aviation publications such as Vintage Airplane and EAA Sport Aviation, Flying Magazine, National Geographic, AOPA, Barron’s, American Bonanza Society and King Air publications, Seaplane Pilots Association, General Aviation News, and the state of Tennessee and local media sources for his significant aviation contributions the past 60 years.

If you had the opportunity to come witness what John has built with his personal time, fundraising and generous donations, you would experience a first-class aviation museum and community in Tullahoma. A campus that welcomes visitors from all across the globe. A successful businessman and a Sporting

Goods Industry Hall of Fame inductee whose hobby turned out to be a lifetime achievement in aviation. John’s passion to bring people together and his legacy will be perpetuated throughout generations of his personal, museum, and aviation community friends and family.

In 1973 John’s vision to preserve the Staggerwing model came to fruition. … John put his heart and soul into the project, and the museum that began as a two-room log cabin and hangar evolved into a 78,000-square-foot, fully climate-controlled world-class general aviation museum.John and family featured in the Vol. 156, No. 3 September 1979 issue of National Geographic on page 366 in the “OSHKOSH: America’s Biggest Air Show” article written by Michael E. Long. John in front of his D18S in front of the Beechcraft Heritage Museum. John flying his Cessna 206. John with his D18S at the Beechcraft Heritage Museum in 2023. ROBERT G. LOCK

BY ROBERT G. LOCK

BY ROBERT G. LOCK

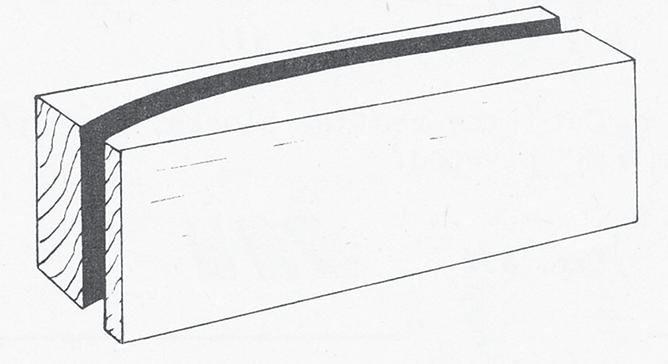

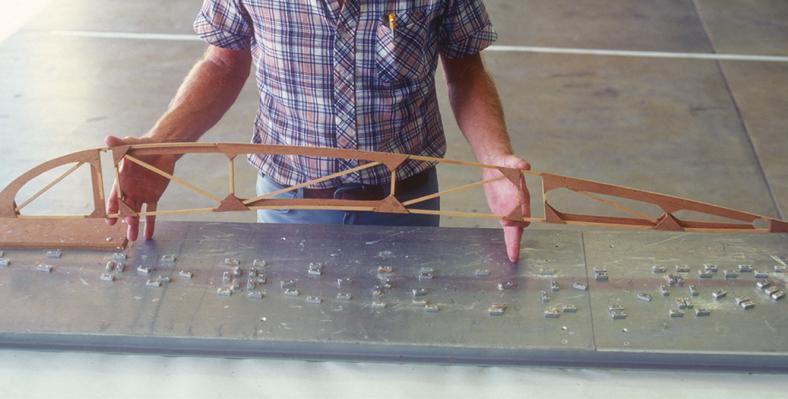

A CAP STRIP BENDING form is a fixture in which wing rib cap strips are bent to proper curvature. The cap strips will have their fibers softened in hot water and then are clamped in this fixture while still wet. When the moisture has dried they may be removed from the form and will retain their curvature.

To make the form it will be necessary to secure a large section of soft wood—I like to find a really good piece of fine-grained and knot-free redwood about 18 inches in length that measures at least 4 inches by 4 feet. Using an existing wing rib, trace the outline of the upper (and if necessary the lower) cap strip nose section where the bend is the most extreme.

Since the formed cap strips will tend to “spring back” somewhat after they are removed from the form, it is a good idea to saw the block with a slightly sharper curve than needed. Cut the form with a band saw and sand the cut smooth.

To soak the cap strips you will need to construct a tube capable of holding water. There is no need to soak the entire cap strip but rather the forward section only, about from the front spar forward. I use a section of 4-inch

diameter PVC pipe about 3 feet long and bond a cap on one end. When ready to soak I put enough hot water in the pipe to wet out the cap strips and then drop the strips into the water. Since wood likes to float, if needed add some weight to hold the cap strips down in the water. Let them soak for one to two hours. Remove and immediately place in the form block, clamp down using two C-clamps, and leave overnight to dry. The dry redwood form block will absorb most of the moisture of the cap strips.

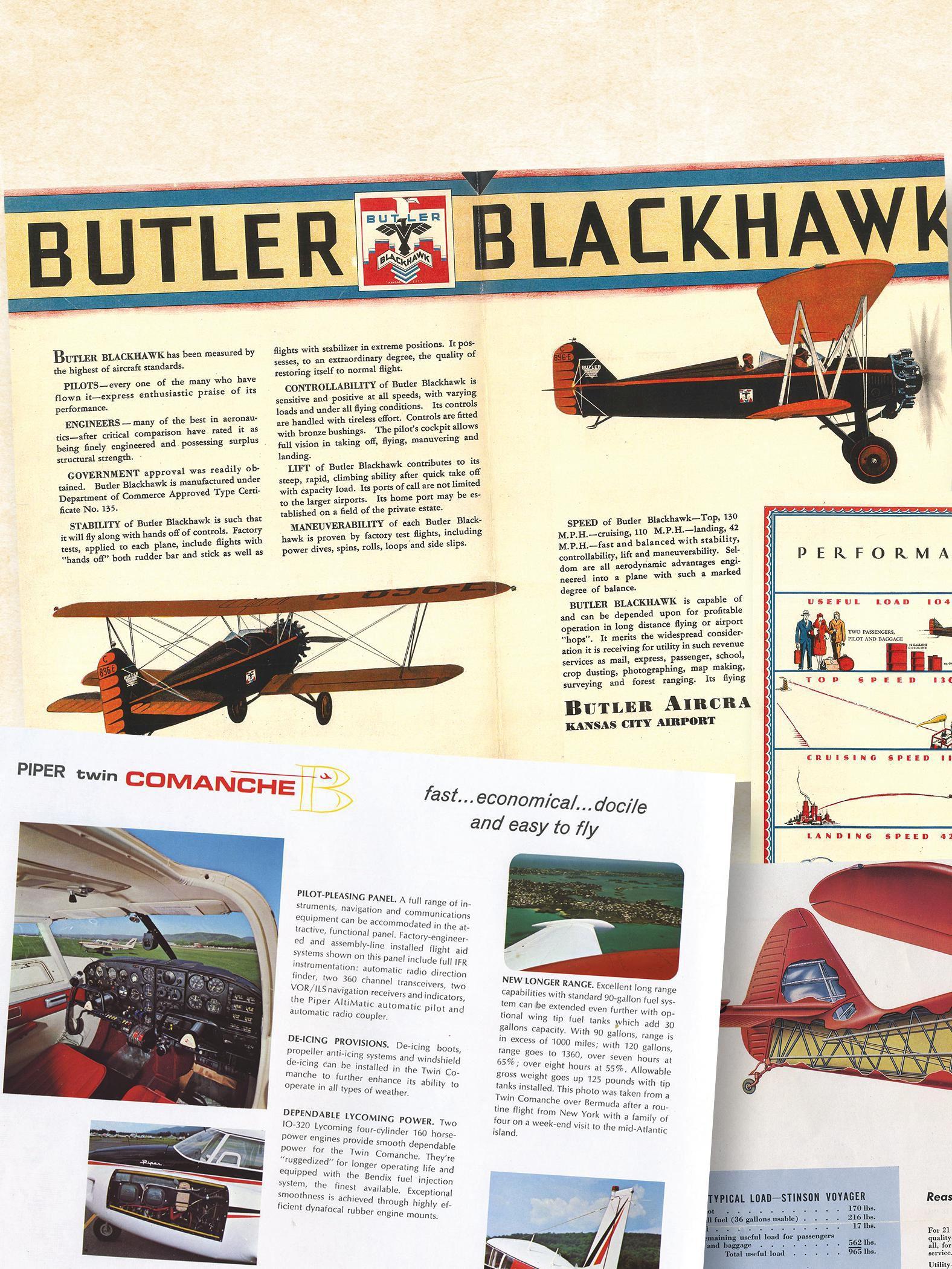

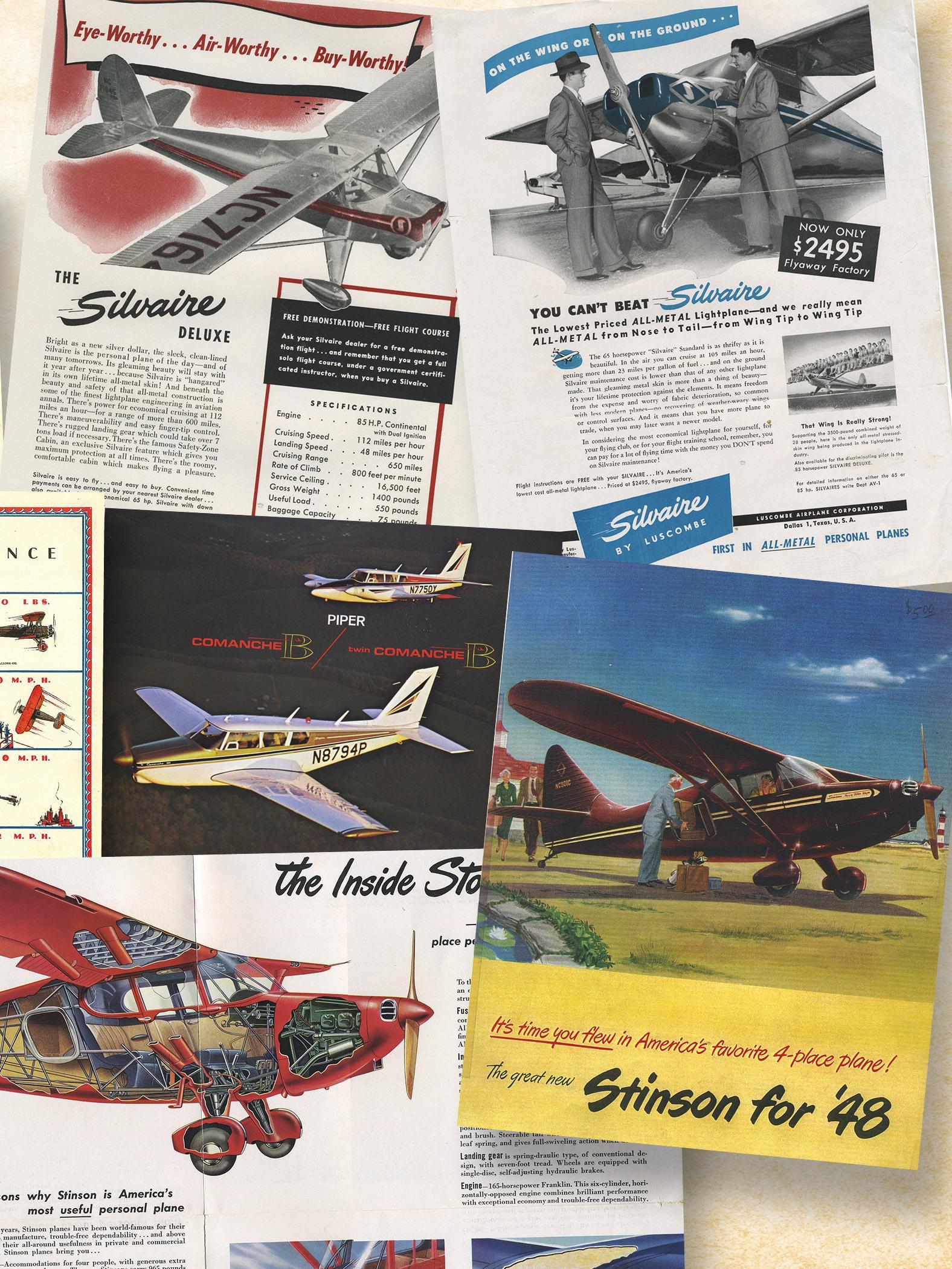

From the pages of what was ...

Take a quick look through history by enjoying images pulled from publications past.

STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY SPARKY BARNES

STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY SPARKY BARNES

WINGING THEIR WAY ACROSS the country, an eclectic and widely diverse array of antique and vintage airplanes arrived the first weekend of June at Le Sueur Municipal Airport (12Y) in Minnesota. They ranged from the small Culver Cadets to the behemoth Grumman Albatross. There were also Wacos, Swifts, and Staggerwings; and a Spartan Executive, Monocoupe, Ryan SCW, Howard, Mullicoupe, and Cessna Airmaster; and the roster goes on. A Champ with its original fabric, paint, and engine was on hand, and rarest of them all this year was a 1927 Avro Avian 7083. It was flown by Carlene Mendieta in 2001 on the “Amelia Earhart’s Flight Across America: Rediscovering a Legend” round-trip flight across the United States.

This aerial convergence was inspired not only by spring’s final melting of the Minnesota snowpack, but also by the heart-warming welcome that Marginal Aviation bestowed on its attendees. Upon arrival and often prior to even climbing out of their airplanes, pilots and passengers were greeted by members of the Marginal team with a hearty “thank you for coming!”

Revered by veteran fly-in attendees as a most hospitable fly-in, First Ditch is where the love and passion for antique and vintage airplanes pullulates, and aircraft knowledge and expertise are enthusiastically shared.

Marginal Aviation is a stand-alone, independent, antique airplane organization. Born and based in Minnesota, Marginal has members

throughout the country. Eighteen states were represented at this year’s fly-in, including the far reaches of Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, California, and Washington. Of the 111 airplanes flying during First Ditch, 91 were vintage/antique. The FBO sold 1,300 gallons of fuel during the event.

Marginal actively encourages young folks to be involved in aviation by engaging them in person and through social media channels, and by respecting them as peers. “As an organization, we don’t want cliques or generational gaps. At our fly-in this year, we had 40 airplanes flown by pilots who were 45 or younger,” said Vaughn Lovley, spokesman for the fly-in, “We’ve found that if you treat a few young people the right way, then they bring more young people around, and it becomes kind of viral, and most importantly, everybody gets along with each other.”

Marginal Aviation has been around for six decades as a nonprofit group. Its genesis was back in the 1970s, when Minnesotans Forrest Lovley (2022 VAA Hall of Fame inductee) and Gary Hanson were breathing new life into antique airplanes, and other folks started helping and following suit. Numerous award-winning aircraft were restored by these individuals through the years. More recently, thanks to legwork by members Jen Hanson (Gary’s daughter-in-law) and Linda Lovley (Forrest’s wife), the group recently acquired its official nonprofit 501(c)(3) status.

The affable group started hosting its fly-in gathering back in 1979. They called it “Last Ditch,” since it was the culmination of the antique airplane flying season in the Midwest. It was held for the first two years in October at Roy Redman’s farm outside Faribault, and only 11 airplanes attended. It outgrew that airport and was then moved to the Lovley’s new hangar at Sky Park Airport in Lydia. The previous record was 75 airplanes at Lydia in 1983, and then it outgrew that location and was held either at Le Sueur or Faribault.

By the late 1990s, those gatherings had gone by the wayside. Then in 2013, Toby Hanson and Vaughn Lovley, sons of the original co-founders, reenergized the group and decided to host a fly-in in the late spring of 2014. They named it “First Ditch,” since it would be the first antique fly-in of the year in the Midwest area.

The group’s successful momentum is fueled by a team of volunteers who pour their hearts into every aspect of the organization. Among the

volunteers is one who quietly devotes himself to helping others in myriad ways. Tim Verhoeven’s eagerness is evident; he recognizes what needs to be done and springs into action without fanfare. One of his missions this year was helping people stay hydrated by driving around the airport and handing out water bottles from a fully stocked cooler.

Another volunteer, Barb Frost, makes a significant contribution by opening her hangar during the fly-in; it’s where all the meals are served and where people are welcome to congregate. Poignantly tucked into the back corner of her hangar is the Fleet in which she and her husband Larry (now deceased), flew on their honeymoon. Their daughters are third-generation Marginal Aviation members; Debra Wilbright owns a Super Cub, and Shannon Frost printed all the attractive fly-in signs that were on the airport — some of which direct attendees to the Frosts’ food hangar.

Notably, there isn’t a fly-in registration or camping fee, and the always plentiful supply of food is made available by a hardworking team led by LuVerne Verhoeven and Linda Lovley. Donations for meals are appreciated; in fact, the organization is funded by donations and apparel purchases. Marginal’s message of “buy a T-shirt and you’re a member” embodies their selfstyled philosophy.

“We’re not dictating what our organization is worth. We want to know what our membership thinks we are worth — that’s number one,” Vaughn said, “We have a solid group of people who show their appreciation by their donations, which are used for fly-in

expenses, building our apparel inventory, and keeping donated aircraft — such as Duane Duea’s historic Pietenpol — flying. Marginal has zero compensated people; we’re all volunteers.”

First Ditch 2023 was one of the highlights of Vaughn’s aviation career. “I really enjoy watching other people fly

airplanes and have fun, and the positive feedback we’ve received is very rewarding for all of us. For me, it’s really neat that my parents’ generation created something that had a little cult following for a long time, and had the cachet to have someone want to revive it,” Vaughn mused. “We’re reliving the old days in a new-school fashion, and it’s also our way of saying ‘thank you’ to the first generation of Marginal Aviation. We want to do everything we can to make people feel welcome. We don’t want cliques; we want a whole big group together celebrating the very same thing — vintage and antique aviation.”

On Saturday afternoon of the fly-in, an impromptu event introduced a local group to an amazing variety of aircraft. “A tractor came into the airport entrance, pulling a hay wagon with a graduation party on board, and they were all waving and happy. I saw the glow on their faces,” Vaughn said, “so I guided the farmer around for an airport tour. His farm was close to the airport, and he’d seen the airplanes flying and thought the kids would enjoy seeing them up close. That worked out great and was a very safe way for them to visit the fly-in.”

“It was an aviation experience I will cherish!”

— Hannah ShicklesMark Baker’s NC67555, a 1944 D17S Staggerwing. Steve Roth’s 1946 Globe GC-1B Swift flew in from Virginia. Vintage Luscombes, Swifts, and Cessnas on the flightline.

Lynn Towns, one of many veteran fly-in attendees, shared this: “I have never been thanked for attending a fly-in before, and I was thanked at least three or four times at First Ditch. It made me feel genuinely welcome. The ‘free’ entrance and food is a great move. I think it promotes a mindset that the fly-in is not being put on primarily as a money maker. When people are happy, I think they will tend to donate more than if they are charged. The on-airport meals provided a lot of opportunities to meet people. Overall, I would rate this as the best fly-in I have ever attended.”

Nineteen-year-old Hannah Shickles, curator for the Kelch Aviation Museum in Brodhead, Wisconsin, flew a 1938 Chief to First Ditch. It was her first time

flying to a fly-in, and she shared: “Flying in by myself, I was definitely out of my comfort zone. Although, as the weekend progressed, I made fast friends with the people camping next to me. We talked about airplanes,” Hannah shared, “and I participated in a three-ship photo shoot, flew dawn patrol, and made many wonderful connections with people from all around the country. I logged 10 flying hours over the weekend. It was an aviation experience I will cherish!”

Jim and Eileen Wilson decided to spend their 50th wedding anniversary with fellow Marginal Aviation friends, so they flew their Cabin Waco from South Carolina to Minnesota. Little did they know that Marginal had a surprise celebration planned for them, with a congratulatory banner proclaiming their special occasion. “What they did for us on our wedding anniversary was just over the top; it was the most memorable and heart-warming fly-in,” Jim said. “The whole fly-in was well executed and just plain fun!”

“We want to do everything we can to make people feel welcome.”

— Vaughn LovleyGlenn Larson enjoys flying his 1939 Cessna Airmaster on floats.NC1127E is a 1946 Aeronca 7AC Champ based in Iowa. Walt Bowe’s 1940 Spartan 7W Executive flew in from California. Debra Wilbright of Le Sueur owns this 1960 PA-18 Super Cub. The Rezich family’s Culver Cadets were flying frequently.

BY BUDD DAVISSON

BY BUDD DAVISSON

“I’M A FIRM BELIEVER that old airplanes have a way of finding us. We don’t find them,” said Ryan Sherwood, EAA 1007580/ VAA 729766, of Granger, Indiana.

That being said, what he doesn’t say is that for them to find us, they often have to make many stops along the way and make friends with more than a few owners and pilots. When it came to Stinson 108-1, N8502, the trail to Ryan’s hangar included nearly a dozen stops along the way. However, owner No. 11 proved to be vulnerable to Ryan’s persistence.

“In February of 2020, owner 11, Bill Plaster, started toying with the idea of selling the airplane and made a posting on the Stinson Facebook page, gauging interest,” Ryan said.

“Several others and I eagerly responded to the posting, but once Bill went out and flew the airplane ‘one last time,’ he decided it was too nice to let it go and kept the airplane. However, I wouldn’t give up.

“In July of 2020, during the midst of the COVID pandemic, I figured nothing would make things more bearable and interesting than getting the right airplane, and I reached out to Bill to see if he had sold the airplane or had any more thoughts of selling,” he said. “As fate would have it, Bill was open to the idea of my father and I coming down

to look at the airplane, but he was still unsure if he was ready to sell.”

Sometimes things just seem to fall into place, and this deal certainly was shaping up to be that way.

“Bill and I had a few mutual friends through the Waco community (as everyone knows, the aviation community is small, even smaller within the vintage side), despite the distance of 550 miles between us,” Ryan said. “Bill, being the meticulous caretaker that he is, had asked around about me and my father, Tim Sherwood, to ensure that we were the right people to potentially take over care duties for Stella , as we eventually called the airplane.

“When we arrived at his hangar, the doors hadn’t even fully opened and I knew right away, this was it! The airplane was glowing in the sunlight shining through the opening of the doors, and everything was clean, neat, and tidy,” he said. “There wasn’t a thing out of place nor a fault to be found! My dad, being an A&P, quickly went to work on looking the airplane and paperwork over, and I looked over every inch of the airplane, but there was simply nothing to be found. Could it really be the one?”

Ryan went prepared with a purchase agreement and cash in hand for a deposit, hoping that, if the airplane checked out, Bill would be ready to transfer its care over to him.

“After a brief conversation and a promise that if now wasn’t the right time, I’d be ready whenever he was, Bill decided I was the right one to take over custody of Stella,” Ryan said. “A dream was finally starting to come true for me, and I couldn’t wait to share the news with my family.”

Ryan got to know Stella on their flight home together.

“My first takeoff in the airplane was admittedly not attractive,” he said. “It was a very gusty crosswind takeoff, and I discovered quickly that I needed to keep my toes much farther away from the brakes than I was used to. I was glad we were at the far end of the runway, so Bill didn’t have to see my less-than-ideal technique! Luckily, I had my good buddy Bob Danielson there to laugh at me and calm my nerves and self-critiques of my poor performance, something great friends are always good for!

“The entire trip home was battling a 30-to-40mph headwind, so Stella and I had ample time to

get acquainted with one another,” he said. “I was simply amazed at how smooth the Franklin engine ran; it is hands-down the smoothest piston engine I had ever flown behind. The airplane is very honest and solid in its flying characteristics. There are advertisements for the airplane that reference it being the ‘Cadillac of the Skies,’ and I can attest to that accuracy.

“It was with great anticipation that I dialed in our home field [Elkhart Municipal Airport in Elkhart, Indiana] AWOS and

“As I turned onto the final taxiway, I could see my awaiting family and friends, ready to celebrate a new member of the family coming home to roost.”

— Ryan Sherwood

prepared for the conditions,” he said. “The winds were still howling, 230 at 17-25. However, the hardest part of that day was taxiing back to the hangar as the winds were really trying to get the airplane to swap ends. As I turned onto the final taxiway, I could see my awaiting family and friends, ready to celebrate a new member of the family coming home to roost.”

A crew had assembled with cameras, phones, and smiles to welcome Ryan and Stella home.

“When you’re pulling up to your hangar, and your wife, daughter, parents, and friends are all there, you can’t help but get smacked with a flood of emotions,” he said. “My wife, Angela, had pulled my daughter, Amelia, out of school for this occasion, but what made this even more exciting and special is that one of my best friends, Brandon Herzog, was in attendance, and he had no clue what I had done! You see, Brandon was always ribbing me about buying my own airplane and had convinced himself and vocalized it to others that I’d never do it as nothing was ever going to be good enough. It was a challenge to keep it a secret, but it was also fun as I knew it would be a big shock to him. I don’t think I can share all the words that were used to describe me and that moment, but it was a good laugh and memorable time for the both of us. I did have to promise to never do it again, though. That evening Paul Ditsler, Brandon, my dad, and myself enjoyed a celebratory beverage while giving the girl a good wipe-down from her 550-nm journey home.”

After he got the airplane home, Ryan realized he had a more personal connection to this Stinson.

“A good friend of mine who worked at Univair at the time, who has all the files and owns the type certificate to the airplane, sent me an email on my way home and asked me if I knew that I had relatives that worked for Stinson,” he said. “Attached to his email was a final delivery weight and balance inspection, and I saw one of the signatures had the same last name of Sherwood and thought, ‘Wow, that’s cool!’ but didn’t give it much more consideration as I looked at it on my phone and was busy with other duties. It wasn’t until I got home and looked at the email again, this time on my iPad, that I was able to discover that this was the original weight and balance signoff for my airplane! So, someone with the same last name as me signed off this airplane as airworthy when it left the factory 76 years ago!

“Another bit of interesting history comes from the name Stella,” Ryan said. “When the airplane was sold to its first owner, National Airmotive in Chicago, Illinois, the original bill of sale was signed by Estelle Stinson herself. With the discovery of that, we felt Stella was a perfect fit to give nod to that history and fit her well.”

And Ryan shared another interesting bit about Stella’s history.

“What few people know, and many don’t believe, is that although she is an absolutely perfect airplane, she isn’t a recent restoration,” he said. “In fact, as of this year, it has been an unbelievable 30 years since Dan Knutson and his dad, ‘Doc,’ finished it.”

Dan Knutson was owner No. 7 (out of 12 total), and certainly the most outstanding acknowledgement of what he and his dad created in N8502 was that the airplane received a Silver Lindy for owner No. 9, Bill Robicheau, in 2007 — 14

“It just proves that, with proper care, a good airplane can continue to connect us to our aviation roots for generations. In fact, that’s pretty much what the Vintage Airplane Association is all about, and I’m proud to be part of it.”

— Dan Knutson

— Dan Knutson

years after it was restored. Fourteen years! She got a Preservation Award at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2022.

Dan, who is currently vice president of the EAA Vintage Aircraft Association (EAA 402120), goes back a long way with 108 Stinsons.

“I suppose,” Dan said, “that it could be said that I was born to them inasmuch as Dad flew Mom to the hospital in his 108-2 so she could deliver me.

“I soloed a C-175A when I was 16 years old,” he added. “That was in 1973, which is 50 years ago and doesn’t seem possible.”

Dan said that although his dad was a chiropractor by trade, his life was rebuilding airplanes, and it was something they did as a team.

“We rebuilt or restored a total of 22 airplanes before I lost him a few years ago,” Dan said. “That included two J-3 Cubs; a PA-11; four PA-12 Cruisers, including one on which we installed flaps and a PA-18 Super Cub landing gear; a 170B; three 7ACs; and a Piper Colt converted to tailwheel. The Colt was super light and still had the original 108-hp engine and was a huge amount of fun. Today, our travel airplane is a 250 Comanche, and our fun airplane is a J-3 Cub.

“Right now,” he said, “I’m working on a 150 TriPacer that is something of a time capsule, as it is serial No. 4. It was ferried to Lodi, Wisconsin, where I live, in 1981, taken apart with every single part documented and tagged. It then sat in a hangar until I bought it. I have the production records on the airplane and the build card for the engine, and I’m taking it back to 100 percent factory original.”

Dan easily recalled their time with the aircraft.

“Stinson 108-1, N8502, came into our life in 1990,” Dan said. “A previous owner was injured in a car accident and kept thinking he’d eventually recover to the point that he could return to flying. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen, and it sat in a hangar for over 10 years.

“It wasn’t exactly a ‘barn find’ but was pretty close,” he said. “It only had 800 hours’ total time on it and basically was in really good condition but had never been rebuilt. It was a 43-year-old airplane and was a terrific starting point. So, Dad and I stripped it down to the tubing, sand blasted it, and brought it back up.”

And he still remembered all the details of the restoration.

“Starting at the front, we had to get a new spinner because the airplane was equipped with an Aeromatic prop,” Dan said. “Those were no longer being supported, so we replaced it with a Sensenich wooden one. Plus, it fit the looks of the airplane better.

“The majority of the sheet metal on the airplane, including the nose bowl, was in good shape, especially considering the age. It had a dent here and there that we had to iron out, but we didn’t use any filler. We

Univair is the Type Certificate holder for the Stinson 108 series. We have thousands of quality parts specifically for these airplanes. Many of our parts are made on the original tooling that was used when these great aircraft were first produced. We also have distributor parts such as tires, batteries, tailwheels, and much more. Call today for a free catalog (foreign orders pay postage).

did have to replace the metal on the landing gear legs, plus the wheelpants needed a little work, but not nearly as much as you run into on an airplane this old.

“When we stripped the wings, there was only a little repair work to be done and no corrosion at all, so they were a clean-up-and-cover situation,” he added. “The fuselage had zero corrosion, which is almost never the case. It was primered at the factory and it had held up, so we sandblasted it and painted it with Randolph Epibond primer.

“Only the rudder needed repair,” Dan said. “It looked as if the hangar had settled under a snow load or something, and came to rest on the top of it, and crushed it down a little.

“The structural part of the instrument panel was pretty much original, but the overlay had been

cut up, so we got a new one from Univair and went from there. One really unusual aspect of the airplane is that it came out of the factory with an ‘advanced blind panel,’ including a Hallicrafters radio, but we didn’t install a radio, using a handheld instead. However, we never installed a glove box door. I guess that’s where a later owner put an original Hallicrafters faceplate that hid modern radios. A good idea!”

Dan said they also took special care when it came to the finishing touches.

“When it came to the upholstery, we sourced original factory-style material through the famous antique auto upholstery supplier LeBaron Bonney, now defunct,” Dan said. “Then we took that to our friend Don Stretch at AirTex, and he stitched up what looked like a factory-original interior for us.

“One of the things that attracted us to this particular Stinson is that it was painted what was called Stinson Yellow right from the factory, and yellow Stinsons are extremely rare. In fact, only 125 of them are that way,” he added. “The color was pretty close to Cub Yellow but subtly

different. When we shot it, we used Randolph dope and enamel, and they matched so closely, it was hard to tell which was which.

“It was a really good airplane, and I’m pleased to see so many subsequent owners have enjoyed it and kept it in such good condition,” Dan said. “I know Dad would like that. It just proves that, with proper care, a good airplane can continue to connect us to our aviation roots for generations. In fact, that’s pretty much what the Vintage Airplane Association is all about, and I’m proud to be part of it.”

It might be overstating things to say that, given the right conditions, a vintage airplane can tell its tale forever, but N8502 certainly points to that possibility.

BY CONNOR MADISON AND AMI ECKARD-LEE

BY CONNOR MADISON AND AMI ECKARD-LEE

THE UNITED STATES, SUMMER OF 1927: Babe Ruth was breaking baseball records, Prohibition was in full contentious swing, war was over, and jazz was hot — and Lucky Lindy’s triumphant solo crossing of the Atlantic that May had tossed the world into a fevered aviation boom. It seemed like every company even marginally equipped to deal with aviation tried to cash in on the craze and start selling airplanes — and the majority of those companies were a flash in the pan, quickly rubbed out of existence by the stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression.

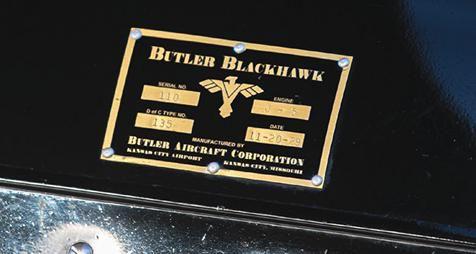

The Butler Manufacturing company of Kansas City, Missouri, dove into the fray in 1928 with a promising setup: in-house designer Waverly Stearman, the less-famous brother of aviation design legend Lloyd Stearman; an existing, successful, and wellknown business manufacturing steel grain bins and aircraft hangars; and a prime location in the 1920s aviation hotspot, Kansas City. Its plan: a sleek three-place biplane, large enough to carry passengers or mail, powered by the engine Lindy had made famous, the Wright J-5.

The company’s first prototype, named the Skyway, performed test flights in October 1928. After some design modifications and a new name, the factory line was ready to launch production of the Blackhawk. The new biplane was offered with only one engine option, the Wright J-5. Roaringly popular after Lindbergh’s famous use, this ninecylinder radial engine cost 10 times as much as a World War I surplus water-cooled engine

or other competing 1920s aviation engine. A great boon for boosting sales in the late 1920s — but a cost burden unable to survive the Great Depression. As 1929 drew to a grim close, Butler’s aircraft sales stopped almost before they began; records show the company set aside serial numbers for 11 airplanes, but no one knows how many truly made it to the end of the assembly line. It’s likely that as few as nine ever saw the light of day.

Against all odds, however, two of the original Butler Blackhawk aircraft still exist today. Serial No. 111, the Blackhawk Sport model and the last aircraft the company produced, now hangs on display in Science City at Union Station in its hometown of Kansas City.

Serial No. 110, the penultimate Butler Blackhawk, belongs to Kent E. McMakin of Illinois. Stunningly restored, with a star-studded provenance and inspiring family story, the biplane is based in Brodhead, Wisconsin, and on display at the Kelch Aviation Museum. And yes, thanks to a series of small miracles, this beauty still flies.

Blackhawk serial No. 110, registered as NC593H, rolled off the assembly line in November 1929. One has to wonder what the general spirit in the Butler workshops was; the economy was tanking and a bitter winter was setting in. Nevertheless, the airplane quickly sold to a gentleman in Chicago. During the two years of its first ownership, the aircraft suffered damage bad enough to necessitate a thorough rebuild. The oldest known photograph of NC593H shows the aircraft at Chicago Municipal Airport post-rebuild, the fresh repairs clearly visible.

Through the early 1930s, 593H changed hands a number of times, with a brief stop in 1933 in Chicago for more repairs, this time in the shop of famed aviator and designer E.M. “Matty” Laird. Perhaps due to the shaky economic climate and rapidly changing aviation world, “it went through so many owners,” current owner Kent McMakin said. “It’s hard to decipher the trail — it just got flipped all the time.”

The Blackhawk’s trail then meanders south, crossing paths with two more notable figures in aviation: a pit stop for maintenance at the legendary air racing shop of Wedell-Williams, and then a brief ownership by crop-dusting pioneer J.O. Dockery (records indicate 593H was never modified to crop-dust, although Dockery probably considered it).

Hopping from owner to owner and routinely ground-looping, the airplane flew through the decade and the Midwest, from Missouri to Iowa and eventually Wisconsin — first in Columbus, a short stint at the Portage airport with the Mael brothers, then on the lot for sale at McBoyle’s Piper Sales in Lake Delton, Wisconsin. And that’s when the Blackhawk finally landed with a stable owner, Don McMakin — a man who would eventually play a key role in saving the aircraft in the 1990s.

Born in Northern Illinois in 1918, Don started flying shortly after graduating high school in 1937. He built his hours in Cubs and Luscombes at the former South Beloit airport, a bustling place just across the state line from Wisconsin, before teaming up with longtime friend

“Every time he’d talk about it, he’d say, ‘It was a ground-looping son of a gun. We ground-looped it every other landing!’”

— Kent McMakinNC593H at Chicago Municipal Airport with visible repairs.

Don Keeney to buy an OX-5-powered Bird prototype.

In the early 1940s, the Spartan School of Aeronautics in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was launching civilian pilot training (CPT) programs around the country, aiming to provide comprehensive pre-military training to address the national lack of pilots available for entry into service. South Beloit airport’s manager, Pete Tummelson, heeded the call and told his friends back home that the program was keen to hire civilian flight instructors. Figuring that was a better option than being drafted, Don and four other airport guys agreed to give CPT flight instructing a shot. In order to qualify, each potential instructor was required to have at least 20 hours of time in 200-hp-plus aircraft. But at the time, there wasn’t a single aircraft at the South Beloit airport with more than 175 hp. The solution? Fly over to McBoyle’s Piper Sales and pick out a heftier airplane — the Butler Blackhawk, fresh on the lot and ready for action. The five young pilots pitched in and bought the airplane together, bringing it home to South Beloit to fulfill their CPT instructor requirements.

“All those guys just flew the heck out of it to get their 20 hours in,” said Kent, Don’s son. “That’s all they cared about — the ‘Blackhawk Club’ was for the sole purpose of putting in some time.” Unfortunately for Don, the 20

hours wouldn’t matter in the end. When it came time to take the physical exam for Spartan and the CPT, he was told he was “a little bit colorblind” and failed.

So instead of being a flight instructor, Don remained at his job with Fairbanks Morse Defense; due to the nature of the company’s work, he was offered a deferment. One by one, the other members of the Blackhawk Club went their separate ways; in 1942, Don was drafted into the Navy, leaving the Blackhawk in the care of the one remaining owner, Fred Leatherby. Fred operated a flight school at the old Brown County Airport in Green Bay, and that’s where the Blackhawk was based for the duration of the war.

After the war, Don left the Navy and bought Fred’s share of 593H, bringing it back to South Beloit for two years — but life and priorities had changed. In 1943, Don had married Ruth Henderson, an aviation-minded young woman he met at the airport. After some adventures together in the airplane — by all accounts, Ruth was the better pilot — the couple decided to sell the Blackhawk and move on from aviation.

At this time, the airplane was probably the most worthless it would ever be. People were concentrating on family life, no one had spare money for such expensive hobbies, and the airplane itself was outdated. After trying and failing to sell the airplane to various crop-dusting outfits, Don finally managed to “get rid of” it in 1947, selling to a man in Coldwater, Michigan, for just $350. That money and a stockpile of war bonds went to build the McMakins’ first house — the same house where an airplane-crazy kid named Kent McMakin would grow up hearing stories about flying biplanes in the “old days.”

Looking through 593H’s history there’s a noticeable trend: a series of ground loops, over and over, no matter the pilot or the circumstances (somehow this didn’t faze the young men of the Blackhawk Club at South Beloit back in the 1940s). Kent remembered his father talking about the airplane’s unfortunate tendency. “Every time he’d talk about it, he’d say, ‘It was a ground-looping son of a gun. We ground-looped it every other landing!’” But why? One of the main causes was a switcheroo on the wheels. Originally sporting large Bendix wheels and brakes, somewhere early on 593H had been outfitted with a pair of much smaller Goodyear air wheels. While the air wheels are better on pavement, the smaller brakes that accompany them aren’t helpful. As Kent put it, “The brakes were marginal at best.”

Add to that the “rather sneaky” pivoting tailskid on the airplane, equipped with bungees for shock absorption and to keep the skid centered. “That type of a tail skid is very problematic,” Kent said. “If the tail swings to the full 30 degrees, the bungee cords are not tight enough to correct it, and the skid digs into the ground. Once it starts, there’s not enough rudder to straighten out — and around you go.” All in all, the combination of pivoting tailskid and lackluster brakes, plus the main gear sitting fairly far forward, is likely why the aircraft was ground-looped and wrecked so many times.

“Part of the challenge (and fun) of a project like this is the detective work. With no manuals and minimal guidelines, we were on our own, tinkering and brainstorming to figure out how they did this or how we should do that.”

— Kent McMakin

Born in 1950, three years after his dad sold the Blackhawk, Kent McMakin had no idea about the special biplane as a kid. In fact, he had no idea of his parents’ connection to aviation at all until one afternoon when the young family stopped by the old South Beloit airport and went for a ride with Don’s old friend and instructor Russ “Van” Van Galder.

“It was a Piper PA-14 Family Cruiser. I was probably 5 years old, crammed in the back seat with my mom and brother, my dad and Van in the front,” Kent said. “Then I heard Van say to my dad, ‘You wanna fly it?’ And my dad said sure and took the stick. I was petrified — I had no idea my dad knew how to fly, and I thought we were going to die.” Once the shock wore off, Kent was hooked on aviation, and Don returned to it, too, teaming up with his old friend and former Bird partner Don Keeney to build a Baby Ace in 1960. By the time Kent wanted to get his certificate in 1970, his father was partners in a Bonanza with a flight instructor friend, Don Bissell (yes, all three of these pilots were named Don; one wonders how they kept track of each other). Don Bissell and Elif Alseth served as Kent’s instructors, and Van, the same pilot who’d terrified Kent on his first flight, flew his checkride.

Kent attended a two-year A&P mechanic program at Blackhawk Technical College in Janesville, Wisconsin, graduating in 1974. While in school, he purchased a Waco 10 project with a Continental 220, honing his skills after school by doing the entire project himself, including overhauling the engine. After graduating, Kent and Don McMakin bought a PT-22 project and spent two years restoring it together. Father and son talked about every aspect of national and personal aviation history over long hours in the shop, and that’s when stories of the Blackhawk started to come to light. In family photo albums from before the war, Kent found photographs of the Butler Blackhawk during his parents’ South Beloit days.

“I really liked the look of that thing,” Kent remembered. “I talked to my dad about it, but it was hard to get him to say much — he just told me the history behind it and why they bought it. He didn’t really have any big love affair with it or anything.” Still, it fascinated Kent, both the family connection and the story of the aircraft company itself, and “I casually started looking to see if it still existed.”

This was the late 1970s and early 1980s, the preinternet days where you had to do it the old-fashioned way. “I just started asking people. Since I knew it had gone to Michigan, I talked to Mike Kelly in Coldwater and asked him if he knew anything. Mike’s dad said that he remembered seeing an old biplane in the city dump that got trashed back in the day, and we all just assumed that

was the end of it.” But Kent never quite gave up. As the years went by and his aviation restoration career grew — including a seven-year stint working on warbirds at the Weeks Air Museum in Miami, Florida — Kent kept looking for the airplane. For over 20 years, every possibility led to a dead end.

By the ’90s, Kent had returned to the Midwest and established his own business restoring Ryans, Travel Airs, Stearman C3s, and other early aircraft in his shop on the Brodhead Airport. His parents lived in nearby Rockton, Illinois, and Don was one of the “usual suspects” around Brodhead, chatting with other old-timers and tinkering on his own projects.

In 1992, Bill Batesole, an antique airplane guy and friend of Kent, was hunting far and wide for Cub projects. Following a lead on a J-2 supposedly “stuffed in a barn” in southern Michigan, Bill traveled from Vermont to Blissfield, Michigan. The J-2 project was too far gone — but sitting beside it was the bare frame of an unfamiliar biplane fuselage. Bill asked, “What’s that?” And the owner replied, “You probably don’t know it — it’s a Butler Blackhawk.” Bill wasn’t interested in the J-2 Cub, but he bought the Blackhawk that very day. There was just a bare frame, the engine mount, and four old spars. The owner knew hardly anything about it; his father had been in the aviation parts business and “flipped” airplanes and had picked up the Blackhawk remains sometime in the 1950s. By the time Bill showed up and realized what it was, any history had been lost. The owner told him, “I don’t even know where it came from. I don’t have any paperwork. I have nothing for it but what you see here.”

Aware of the rarity of the aircraft, Bill did some research and requested the FAA records for the four Blackhawk biplanes that ended up in the Midwest. Deep in the paperwork, he came across a form 337 for the installation of a UPF-7 tail wheel assembly, the traces of which were still visible on the airframe he had just purchased. Further inspection of the specific aircraft’s paperwork revealed Don McMakin’s name in the ownership history. Against all odds, this was it, 593H, the very same airplane.

Kent happened to be visiting his folks the morning Bill called with the news. “Bill said, ‘Hey, I got one of your old man’s airplanes.’ I thought it was probably the J-5 Cruiser or something, so I said, ‘Which one?’ And he said, ‘The Blackhawk.’” Kent laughs at the memory. “I told Bill, ‘[BS], I’ve been looking for 20 years, and it doesn’t exist!’ and Bill said, ‘Yes, it does — and I just bought it.’”

Bill had tracked down the missing portion of its history. Apparently, after purchasing the airplane from Don in 1947, the new owner defaulted on his loan. The bank repossessed the aircraft and sold it to an aviation parts and airplane flipper — yes, the father of the man who sold it to Bill. The aviation flipper had never registered the airplane, however, and after 40 years the bank still had the registration! Amazingly, when Bill contacted the bank in 1992, there was someone on staff who had been there and still remembered the defaulted loan and repossessed airplane incident. After hearing the story from Bill, the bank had agreed to sign over a new bill of sale to him.

By the time Bill finished telling Kent the story that morning, Kent had already made up his mind. “I told Bill, ‘I’ve been looking for that airplane for 25 years. If you ever want to sell it, consider it sold.’” Bill agreed to sell it on the spot.

Bill hadn’t yet picked up the airplane, so Kent drove to Michigan to get it himself. Back in Brodhead, the first thing he did was park his truck in front of one of the Butler hangars on the field to take photos with the Blackhawk project.

“Dad wasn’t overly excited about it at first,” Kent remembered, chuckling. “He said, ‘You know, it wasn’t a very good airplane,’ but I said, ‘I don’t care — it’s a cool airplane.’” Unbeknownst to Kent, however, Don’s wife, Ruth, “chewed him out for being so indifferent, and he changed his mind.” The next day, Don told Kent he would love to partner on the rebuild.

There wasn’t much to pick up in Blissfield, Michigan: a stripped-down bare fuselage frame, an engine mount, and four old wing spars.

Right off the bat, we contacted the Butler Manufacturing company in Kansas City, Missouri. We knew that the Butler company still owned the single Blackhawk Sport model, previously owned by Leroy Brown in Florida, and we hoped to examine it for measurements and photos. We were fortunate to be helped by Barbara Fay from Butler. Barbara provided us with several of the remaining drawings and advertising brochures that the company still had. She also provided us with actual access to the existing Blackhawk Sport, and we eventually made three trips to Kansas City to get the valuable info we needed.

The rebuild — or “build,” since we had to create much of the airplane from scratch — was fairly routine for an early biplane basket case. We caught a few lucky breaks during the process. Shortly after we finished welding up a new set of tail surfaces, we got wind that EAA had a set of Blackhawk tail surfaces in their archives. I happened to have a set of Sauzedde wheels that EAA needed for the Consolidated PT-1 they were restoring, so we arranged a trade. When I set the tail surfaces on our fuselage, everything lined up perfectly, right down to the minor wear patterns. I’m convinced these surfaces were the originals on 593H, finally reunited.

We also got lucky with the acquisition of a Wright J-5 engine, finalizing the deal the day before its Trade-A-Plane ad was published, disappointing a few potential buyers.

Part of the challenge (and fun) of a project like this is the detective work. With no manuals and minimal guidelines, we were on our own, tinkering and brainstorming to figure out how they did this or how we should do that.

The wings were the biggest challenge, since we only had four old spars (fortunately, both a pair of uppers and a pair of lowers). We received only a single rib drawing from Butler’s archives, but luckily it was the mother of all rib drawings: an assembly drawing of a lower rib showing the aileron bellcrank and aileron profile and hinges. We had the drawing blown up to a 52-inch chord for the bottom wing and a 62-inch chord for the upper, and then made all the jigs and ribs from those drawings. Looking closely at the old spars, you could see the rib spacing and imprints in the wood, showing the wing fitting profiles.

Like most projects of this magnitude, work was hit-and-miss but fairly steady overall. I kept working on professional restoration projects for clients throughout this time; I did two Stearman C3Bs, two Travel Airs, and a few other smaller projects, fitting in the Blackhawk after hours with my dad. And after nine long years, 593H finally received its airworthy certificate.

After nearly a decade of careful restoration work, 593H was ready for test flights in November 2004. Tom Hegy, notable Wisconsin pilot, antiquer, and Kent’s longtime friend, performed the first flights and logged a couple hours in the airplane. Equipped once more with the original large Bendix wheels, strong brakes, and a steerable tail wheel, there was never even a hint of the old ground-loop tendencies; with a little rigging, the airplane flew like a dream.

For both father and son, restoration was the real draw to aviation; flying came second. The beauty, family history, painstaking building process, and against-the-odds rediscovery of the Blackhawk was the highest success for both of them.

In 2012, Don McMakin passed away at the age of 93. Kent, now old enough to retire but “never going to,” as he said, remains the sole owner of the Butler Blackhawk 593H. In 2022 and 2023, Virginia pilot Andrew King performed a second set of test flights, breaking in the overhauled Wright J-5 and slowly building the airplane’s hours. “We’ve been battling with a stubborn brake cylinder, but other than that she’s as good as new,” Kent said.

When 593H isn’t flying, it’s on display at the historic Brodhead Airport in Wisconsin, at the Kelch Aviation Museum, a nonprofit dedicated to sharing golden age aviation history and science with folks of all ages and experience levels. N593H is a favorite with museum visitors, who enjoy both its majestic black-and-yellow art deco beauty and its meandering, miraculous story.

For those farther away, the Kelch Aviation Museum runs a video series online, one of which features 593H. The only other Butler Blackhawk in existence, the Sport model hanging in a static display at Science City museum in Kansas City, collaborated with the Kelch Aviation Museum and Kent to create a video about the Butler aviation venture, the Blackhawk airplane

design, and the two remaining aircraft. You can see that video on the recently launched Science City Union Station app, available for free on all app stores.

You can visit the Kelch Aviation Museum to see the airplane yourself — and you may well find it in action, rolling out over the grass taxiway to take to the skies once more. Listen to the sound of that J-5 radial and watch the sun glint over the striking black fuselage and bright yellow wings. This is a sight and a sound you cannot witness anywhere else in the world.

“Where are thosebums?”

Qantasairstewardesses

EthelBarlowandLouise Hankin,jiltedonthevery tarmacatBrisbaneby thephilanderingflight crewwhogotofftheplanebeforetheydidandranintothehangar toavoidthem.Theyhadnointentionofkeepingthosein-flight promisesgivensolelytomaketimewiththegirls.They’llbe backintheairinanhour,ontheirwaytoDarwinwithanother pairofstewardesses.

Sure,it’sanage-oldployandithurtonlythegirls’egos,right? Butthegirlsfiledacomplaint,andtheboysweresoonhauling sheepcarcassestoadisposalsite.Ofcoursethatdoesn’thappen nowadays…doesit?

BY BUDD DAVISSON

BY BUDD DAVISSON

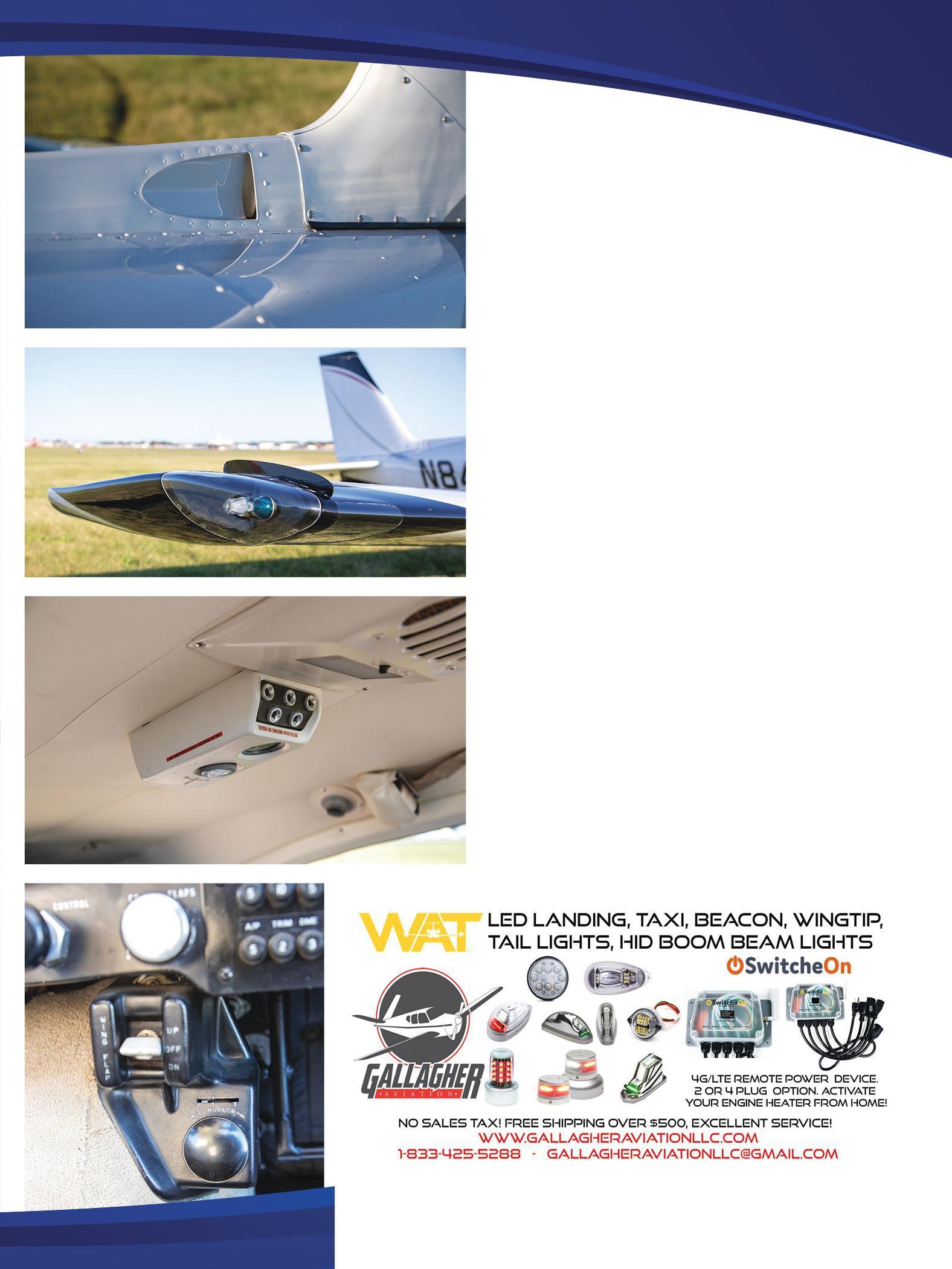

LEE HUSSEY, EAA 883721, of Martinsville, Virginia, might be mistaken for a pirate, but rather than having a parrot on his shoulder, an A&P/IA mechanic is almost always perched there because Lee is always doing something to his award-winning 250 Comanche. Except this time, it was the mechanic’s input that gave him a decisive push in a radical new direction.

“My mechanic, Brad Garber, and I were talking about speed mods for the 250,” Lee said, “and I remember him saying, ‘If you want more speed, you have to get more horsepower.’ However, when talking about speed and being an owner of a 250 Comanche since 1988, I, like most 250 owners, always had a desire for one of the legendary 400 Comanches. However, his comment, my financial condition at the time, combined with my desire to build a rare showplane all motivated me to make it happen.”

Lee is no stranger to building showplanes. His first award for his Comanche 250 was a third-place win in the Sun60 air race at SUN ’n FUN in 1994. The second was Outstanding in Type Contemporary at SUN ’n FUN 2008. Not satisfied with that, he came back to SUN ’n FUN in 2009 with a few improvements and was awarded Best Custom Contemporary. That started him looking for a new project. All he needed was the right airplane to start with.

As a point of information, one does not just bring up Amazon, eBay, or Craigslist expecting to find a 400 Comanche for sale. Only 148 of them were built, all of them in 1964. That’s when Piper decided to go for broke and stuff an eight-cylinder Lycoming IO-720 boosting 400 hp into a lightly modified version of the PA-24. The Comanche 180 and 250, combined with the Twin Comanche, were Piper’s first steps into the world of modern high-performance aluminum aircraft in 1956, the same year the C-172 debuted.

The Comanche production line was housed in Piper’s original location in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, near the confluence of the West Branch Susquehanna River and Bald Eagle Creek, and reportedly was profitable. However, the Comanche

line was not discontinued because of a lack of market acceptance. It was a victim of Hurricane Agnes in 1972. The rivers at Lock Haven crested at 31 feet, which greatly damaged almost all industrial plants in the area, including the Comanche production line and airframes in inventory. Piper was already building a new generation of aircraft in its Vero Beach plant, so production was shut down in Lock Haven, ending over three decades of aviation heritage in the area.

It has to be said that Lee Hussey was not destined to be your average Comanche buyer.

“I wanted something far beyond just being faster,” he said. “Yes, I was looking for speed, but my earlier 250 Comanche showplane project had clearly shown me that one of the things in my aviation life that makes me truly happy is elevating an airplane above just being a nice airplane to being an award-winning airplane. I know that makes me sound as if I’m driven by my ego, but that’s not it at all. I get great pleasure out of personally attending to the smallest details in an airplane that, when combined, make that airplane special. I do stuff like polish the heads of every exposed screw and bolt, and pull the rubber off of Adel clamps so I can polish the aluminum or steel clamp itself before installing it. I guess what I’m going for is a subtle sort of flashy perfection. And yes, I know, it’s also an obvious obsession. I guess my mother and father blessed or cursed me with a bit of perfectionism.

“Even though when I went into the process of locating a PA-24-400, I had a showplane mindset, I did so knowing a tremendous amount more about what that entailed than I did the first time around,” he said. “The 250 had given me a real education about what it took to produce a winning airplane.”

One of the most important things Lee learned is that there are Comanches and there are Comanches, and no two are identical.

“What I was looking for was an airplane that didn’t require going through and rebuilding every system and installing tens

Showplanes are only showplanes for a few years. Once all the hoorahs have been made and the trophies awarded, a showplane just becomes an airplane you’re going to live with and use.

— Lee Hussey

of thousands of dollars of equipment in the panel,” he said. “It’s really easy to get into an airplane restoration or rehabilitation project and not realize you’re descending into a bottomless financial black hole until it’s too late to crawl back out. So, when I went looking for a 400, it had to be one that someone else has already made the kinds of investments I would have to make to have the airplane be, basically, the airplane of my dreams. More than becoming a showplane, it had to be an airplane I could enjoy for the rest of my aviation days. Showplanes are only showplanes for a few years. Once all the hoorahs have been made and the trophies awarded, a showplane just becomes an airplane you’re going to live with and use. It’ll be an amazingly perfect airplane, and you’ll enjoy that, but it has to be an airplane that does exactly what you want it to do in the way you want it done.”

According to Lee, in 2007 FAA records showed that about 107 400s were still on the register.

“It’s not known how many are still flying, but it’s not a lot,” he said. “I did, however, find one that was going through annual in south Texas and was definitely worth looking at. I told my mechanic, ‘If it has chrome rocker arm covers and chrome intake tubes, I would probably buy it.’ It did, and I did. Those features told me someone was putting some pedigree into their airplane.

“They were still doing the annual when I got down there, which gave me a really good opportunity to see what the insides look like, and after a two-day study, I knew it was the one for me,” he said.

Lee noted that the engine is always one of the big questions when it comes to the 400 Comanche.

“The eight-cylinder IO-720s are not only a rare engine, but have a questionable reputation for being hard to start and expensive to overhaul,” he said. “One of the top companies dealing with them is Johnston Aircraft Services in Tulare, California. A lot of ag planes use that engine, and Johnston

has been their go-to company. This airplane had only 45 hours since major on a Johnston engine. That checked a very serious box. And the airplane’s total time was only 3,344 hours. The cooling baffles looked like they were going to take some work, but that’s one of the things I do fairly well myself.”

Avionics were the other question, and they had all been redone sometime in the early 2000s. According to Lee, that included a “Garmin 530/430, S-TEC 55X, lightning strike finder, Shadin fuel flow gauge, and the type of stuff which was pretty much what I would have put in it during that time period. It had an Arapaho windshield modification, Johnston wingtips, new push/pull cables, and wiring harness for the landing gear with a variety of speed mods. The owner was asking absolute top dollar for it; however, when I sat down and started adding up all the stuff that had already been done, all of which I was going to do, it became obvious that the amount he was asking over the average Comanche 400 was actually low. I’d spend much more getting the same stuff done on my own, with a lot more headaches.

“It sounds odd to say it,” Lee said, “but the fact that the paint wasn’t very good, because it was the original factory paint, was a selling point for me. Regardless of how good the paint would have been, I was going to repaint it to my personal scheme. So, I flew the airplane and then to the paint shop in North Carolina, and the project was on its way.”

From the outside, the 400 Comanche looks almost identical to a 250 Comanche, so it could be assumed that it would fly like one, but Lee said that’s not the case.

“For one thing,” he said, “getting it to slow down to come into the pattern takes a lot more planning ahead. Where I’d be cruising the 250 at around 185 mph, the 400 is running 220 mph without even trying.

“I came into the 250 Comanche out of a C-172, which was a pretty big jump,” he said. “The 400 is at least that much of a step up from my 1960 250. For one thing, the flaps on the

The 400 hp, fire breathing TSIO-720 has a reputation for hard hot starting and Lee says don’t even try.I told my mechanic, ‘If it has chrome rocker arm covers and chrome intake tubes, I would probably buy it.’ It did, and I did. Those features told me someone was putting some pedigree into their airplane.

— Lee Hussey

400 are electric Fowler flaps, where the 250’s are manual hinged flaps. That took some time getting used to. Plus, the 400 is a lot heavier. The 250 is around 1,690 pounds empty, where the 400 is 2,363 pounds empty, most of which is engine. My gross weight is 3,600 pounds, where the 250 is 2,800. One of the hints given me by the previous owner was to run the electric trim all the way back when beginning to flare, so you will get the nose up where it should be so you don’t wheelbarrow onto the runway. Trim it to fly final right to the numbers, trim it all the way up, and then be prepared to gently pull.

“One of the most common questions people have about the airplane is its reputation for hot start problems,” he said. “My cure for that is simple: Don’t try to start it when it’s hot. It isn’t impossible, but it’s easy to screw it up. There’s a reason Piper offered a kit that featured dual batteries to drive a 24-volt starter on the 400.”

One of Lee’s proudest improvements to the airplane is the way he sealed up the engine compartment so it would cool the engine better.

“When I first flew it, the cooling from front to back wasn’t good,” he said. “This is where a cylinder head temp gauge with all eight cylinders indicated proved to be a godsend. The

difference between the hottest and coolest cylinder was 124 degrees!

“The baffling on the engine was easily the worst part of the airplane when I bought it. Some of it was badly repaired factory baffles, some handmade; however, it was obvious that big, long motor wasn’t close to being sealed tight,” he explained. “So, with my A&P’s approval, I changed out the old baffles and installed all new 3-inch blue silicone baffle seals. I did a lot of adjustments, and after a bunch of test flights, found my efforts had worked!

“The cylinder temps are now only 35 degrees’ difference between the hottest and the coolest. The hottest cylinders were the two rear ones. Now the hottest one is the third one back on the right, and the coolest is the rear one on the left. This is unusual,” he added, “because it’s such a long engine, the back cylinders are usually the hottest.

“Another point of interest is that before the new baffling, I had to keep the fuel flow around 25 gph just to keep the hottest cylinder below 400 degrees,” he said. “Now, I’m burning 21 gph and my temps are 380 degrees or less. Something to think about when you’re paying $6 to $7 a gallon for fuel!”

On the outside, Lee said he detailed the airplane in many ways the same way he did the 250.

#1320 GROSS WEIGHT INCREASE BRAKE MASTER CYLINDER ...and much more!

STC/PMA/OEM/ MINOR CHANGE REPLACEMENT/UPGRADE 2pt and 3pt OPTIONS

3 and 8 TON OPTIONS

RANGES FROM 24” to 93”

“I polished everything that could be polished, and even stripped the landing gear legs down to the bare aluminum and polished them to where they look like chrome,” he said.

One thing Lee learned from the 400 project was how to pick paint shops.

“They vary wildly one to the other, not only in the quality of their work, but their ability to meet schedules,” he said. “A recommendation I make is to make sure you talk to some of their customers and examine two or three examples of their work. Or more. You can polish Adel clamps and bolts that most people will never see to your heart’s content. However, the paint is right there out in front of you every time you board the airplane, and if it isn’t as perfect as you think it should be, it’ll bug you every time you fly. We used Sherwin-Williams Acry Glo with clear on the final two coats. I now wax it with RejeX wax, which seems to last six months or so. Plus, it lets you clean the bugs off with just a wet cloth. By the way, one of the drawbacks to having an airplane that looks like this is that when I fly it for an hour, it usually takes me two hours to clean it. I think I mentioned that I’m a little obsessive in this area.”

When asked what he’ll do next to the airplane, Lee said a couple of things come to mind.

“I would like to replace the older analog engine analyzer with a new digital type, which would make it easier to retrieve the data,” he said. “The second thing, of course, would be mods that would make it go faster.”

So, did all of that time and effort pay off? It must have, because the Gold Lindy trophy for Grand Champion Vintage Contemporary, AirVenture 2013, along with the Bronze Lindy for Outstanding Contemporary Customized, AirVenture 2010, and the Preservation Award, AirVenture 2019, all sit on a shelf in Lee’s office next to all the trophies earned by his other Comanche.

He wanted a showplane. Looks as if he got one!

THERE, ON THE FLIGHTLINE at the SUN ’n FUN Aerospace Expo this past spring was one loyal Luscombe 8A. Born in 1939, it’s an old hand at helping pilots learn the nuances of flying an airplane with conventional gear. N25142 recently enrolled yet another student in its “Luscombe lessons” class. This time, it was a dauntless young lady who seems to have a pattern of tackling challenges head-on. The more difficult the task, the more appealing it is — perhaps almost irresistible — to 26-year-old Rachel King of Gainesville, Florida. Rachel simply doesn’t allow the vicissitudes of life, and flying in particular, dissuade her.

She was introduced to the world of general aviation just a couple of years ago. “I was in a relationship with a pilot who had an RV-8, and when we went upside down in it, I kind of just fell in love with flying. We would go flying all the time, and I would take the controls sometimes, and I loved it,” Rachel said. “That relationship didn’t work out, so I started looking for a plane.”

In a rather bold move, Rachel bought her own wings after taking only two flying lessons in a Piper Arrow. With her career firmly in place — she’s a nurse and studying to become a nurse practitioner — she’d already determined that she wanted to earn a sport pilot certificate.

Rachel’s rationale for buying an airplane, as opposed to renting, was simple. “If I’m going to spend thousands and thousands of dollars,” she posited, “why would I not just go ahead and invest that in my own plane? It’s going

to be more costly up front for sure, but in the long run, I know I want to fly for fun. So it just made sense.”

She knew that whatever type of airplane she bought, it had to be eligible to be flown by a sport pilot. It also had to be affordable, as well as economical to operate. Hence, a Luscombe started looming on her horizon, and it soon becamehertopchoice.Whilesomemay have been attracted to an airplane with an easy-to-fly reputation, Rachel wanted just the opposite — an airplane that was reportedly harder to fly.

“I guess it’s kind of like a trend in my life. I very much like a challenge, and I knew that if I learned in a taildragger, then I could probably fly anything I wanted to,” Rachel said. “I didn’t really know how dicey the Luscombe’s reputation was until people kept telling me, ‘You definitely don’t want a Luscombe;

“Whenever I’m flying around, it’s just so simple and really beautiful. That’s probably the best thing about it!”

— Rachel King

get a Champ or something else.’ They weren’t steering me away from a taildragger; they just tried to persuade me not to buy a Luscombe. So I was like, ‘You’re saying not to, so I’m definitely going to!’”