22 minute read

Destinations

Finding your way

by P

ili Handleman

When I learned to fly, satellite-based navigation in the form of the global positioning system was so many years away from realization that it was akin to science fiction. The airport and flight school denizens were still adjusting to the very high frequency omnidirectional range, with its network of ground-based antennas resembling upside-down ice cream cones.

If somebody had told us that before powered flight’s centennial year, many light planes would be guided with pinpoint accuracy by cost-effective handheld devices receiving signals from finely calibrated instruments orbiting in space, we simply would have dismissed him as a deluded knave.

Most of the nav and comm radios I used in those days were hardly worth their onboard weight. It wasn’t that the peripherals industry lacked the know-how; it was that the dominant attitude reckoned electronic gear to be exceedingly ancillary to the low-end of general aviation. The readily available products reflected the five-and-dime mindset. Weekend pilots back then tended to fly at the lower altitudes, which limited the utility of the line-of-sight VOR stations. Even if you were lucky enough to have an operable receiver, the course deviation indicator often hung limp until the inverted ice cream cone nearly came into view.

I don’t remember anyone bothering to wear the rinky-dink earphones of the time. Exchanges with air traffic control were comparatively infrequent, since the airspace enjoyed a dearth of encumbrances. You just hoped to interpret the occasional static-laden, marginally intelligible words emanating all aquiver from the bulkhead’s built-in speaker by the experience that comes from rote procedure. “Enter pattern. Report left downwind.” Got it. “Roger.”

Above: Ptolemy’s World Map was conceived in the 2nd century. When European cartographers finally received a Latin translation of Ptolemy’s work, the map that resulted in the 15th century, as seen here, represented a remarkably accurate depiction of the planet as it was then known. The New World was yet to be discovered. (Collection of National Digital Library Polona via Wikimedia. org/Wikipedia/commons)

Maps for aviators have come a long way from handwritten notes on strips of paper tucked inside a bulky set of flight coveralls. The older map is a Local Aeronautical map of the Chicago area, compete with radio beacon locations depicted.

The silver lining in all this was that you had to study and understand aeronautical charts. They were the tool to get you to your destination. Stuck in my old ways, I still carry paper charts for any airspace I traverse. When the flight covers a considerable distance, especially over unfamiliar terrain, I pull out my trusty plastic plotter and draw route lines.

In this era of little boxes that can adduce triangulations in microseconds and project your aircraft’s position on a multi-colored moving map display with an overlay of near real-time, radar-derived precipitation intensities, pencil and paper may seem old-fashioned. But if an electrical failure occurs, or the software packed into the little box’s innards has a gremlin pop up in the middle of the journey, then, literally, where are you?

The real navigational challenge was when I started flying open-cockpit. Retaining my grip on the folded chart in the persistent swirling dust devil above my lap was problem enough. If the route went farther than a single creased panel, such that you had to open, flip, and refold to an adjoining panel, the paper fluttered in the process as if it was in a frenzy of agitation. 16 AUGUST 2012

Trying to advance the chart to the right section necessitated both hands and both eyes. I would cup the control stick between my knees and a forearm, take a peek over the cockpit coaming to be sure I was straight and level with no traffic around and then, like a chicken on a June bug, grab the obstreperous paper and scrunch it into submission. Unavoidably, at flight’s end, I was left with a severely crumpled chart, the pre-scored crease lines barely discernible amid the wrinkles, rips, and dog-ears. It was a shame to blemish such a beautiful document, but at least I knew that I was getting my money’s worth.

The main objective was to hold on to that piece of paper. In a way, your life depended on it. If the wind, in all its fury, plucked the chart out of your hands, it would vanish in an instant, absorbed obliviously into the ocean of air around the plodding biplane, never to be seen again. Some of the old-timers who had that gut-wrenching experience said that they’d put down at the next airport if it was a short distance ahead or backtrack to the last airport so as not to tempt fate. Before resuming flight, they obtained a new aeronautical chart or at least a road map.

A friend and fellow Stearman pilot had lost charts to the raging wind a couple of times. Out of frustration, he adopted dead-reckoning as his preferred navigational technique. His preflight planning involved a call to the local Flight Service Station for winds aloft at stations along the proposed route. Thusly informed, he took off and pointed his ship’s nose in a direction that, on good faith, presumed to compensate for the anticipated drift.

Juggling speed and distance in his head, he estimated his time en route. Glancing at his wristwatch periodically once airborne constituted the extent of his in-flight navigation, such as it was. As his precalculated mark approached, he looked ahead for any inkling of his destination. Whether it was brilliance or luck or some mixture of the two, my friend found his chosen landing site every time.

From my perspective his technique left too much to chance. What if the wind shifted or the mainspring in your wristwatch snapped? What, too, if your compass happened to be a few degrees off its recorded deviation or if you calculated magnetic variation improperly because in a fit of last-minute hurriedness you inadvertently reversed that helpful adage that “east is least and west is best”?

Pilotage made so much more sense. For a person like me, it was practically mandatory. I need to know where I’m at, what ground is underneath me, constantly throughout a flight.

The onrushing wind is still a problem when trying to read paper charts in the Stearman. However, there are tricks that partially mitigate the forces of nature, like stuffing the charts in my flight suit’s lower right pant pocket with each pre-folded to the relevant panel and

exposed face-up for sliding out just enough to get a visual reference and cross-check of the position on the GPS screen. Yes, there is a portable GPS mounted in the Stearman. As long as the gadget is thought of as nothing more than a supportive appurtenance, it’s worth having along.

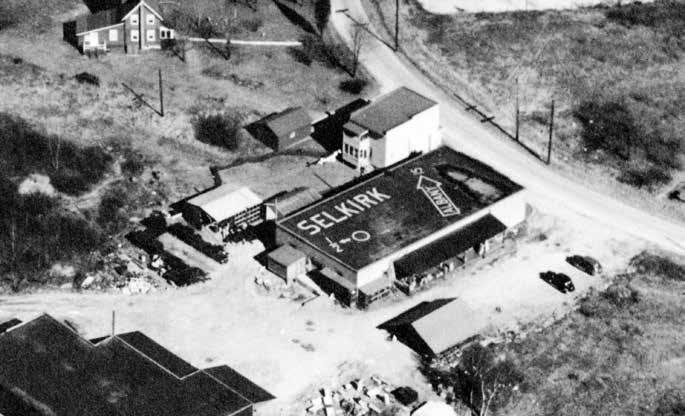

Adhering to the habit instilled at beginner’s ground school, to this day for my longer flights I actually circle landmarks with a pencil about every 10 to 15 miles of the route line etched on a chart. It can be a daunting task when the terrain consists of seemingly endless stretches of desert, forests or mountains, but there COURTESY FAA Air Markers like this one in upstate New York helped guide aviators in the is usually something distinguishable, days before widespread radio beacon use. In 1934, aviatrix Phoebe Faireven in monotonous landscapes. grave Omlie persuaded the Airport Marking and Mapping Section of the Sometimes just a bend in a narrow Bureau of Air Commerce to start the national air marking program. tributary, an intersection of roads, or a cluster of silos can serve as needed checkpoints. “Billy” Mitchell, the outspoken air power advocate.

Great strides have been made in cartographic symAgain, the railroads were the preferred navigational bology, yet misinterpretations still occur. An instructor guide; however, this time the route was a somewhat who mentored many student pilots told me about a straighter line from New York to San Francisco that particular young man under his tutelage. Before going covered 2,701 miles. As in the case with Rodgers’ flight, aloft, time was spent perusing the sectional aeronautithe railroad tracks provided not just a pathway above cal chart that covered the local area. When the student the most inviting terrain, but the capacity to resupply and instructor went up on the initial flight, the student the fliers by train. gazed at the ground below and wondered aloud where The Army’s test was in reality a race with 63 contesthe angled isogonic lines were that ran across the chart. tants. From its start on October 8 until its official closure

Poring over aeronautical charts or maps of any kind at sundown on October 31, the spectacle was marred by is like reading a good book. You have to pay attention, tragedy. Seven participants died in awful crashes. Many but you can immerse yourself in intriguing details and others were injured as the planes seemed no match for glean a plethora of information. Through simple colorthe vicissitudes of the cross-country route. The adverse coding, cartography reveals much about places and publicity didn’t help Mitchell’s cause. their populaces, like the extent of city sprawl, elevaWatching closely were officials of the post office who tion profiles, drainage patterns, and probable arability. had talked about adding a transcontinental component

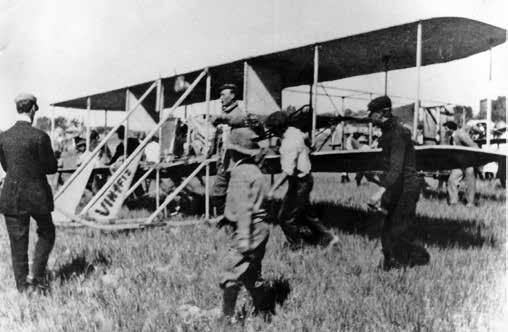

During powered flight’s early years, aviator ambito their nascent air mail service. Rather than allowing tions outpaced aeronautical charting. Indeed, the very the recent Army failure to deter them, plans were made first transcontinental flight from Sheepshead Bay, New to proceed with a transcontinental airway. Like the York, to Pasadena, California, relied primarily on the Army test route, it ran from New York to San Francisco. railways for direction. In the fall of 1911, Calbraith There were 13 interim depot and refueling stops. Using Perry Rodgers steered his Wright Model Ex, the Vin Fiz, American-built de Havilland DH-4s outfitted for hauling westward by almost hugging the tracks that had been the mail, the time to transit the route from start to finish laid to foster American expansion. From the great Midwas estimated to take 54 hours. On September 8, 1920, western metropolis of Chicago, he veered toward Texas the post office inaugurated the route, which prompted to straddle the western mountain ranges at the lowimmediate comparisons to the historic Pony Express. est possible altitudes. The 4,231-mile adventure was Augmenting the rails as a navigational aid, and a slapstick affair punctuated with 15 major accidents. sometimes supplanting them altogether, was the Somehow, cigar-chomping Cal made it to his destinapatchwork formed by section lines, the outgrowth of tion in 49 arduous days. Thomas Jefferson’s vision for cataloging the new na

The science of aeronautics advanced considerably tion’s immense surface area. As someone who believed during World War I, and the Army Air Service decided deeply in the values of the agrarian life, the principal to sponsor a “transcontinental reliability test” in 1919 author of the Declaration of Independence and the to showcase the viability of long-distance flying. The country’s third president wanted surveyors to map out project had the full backing of Brig. Gen. William the land not already settled in the vast open territoVINTAGE AIRPLANE

ries of the Midwest and the West as a way to identify a given tract. Each section consisted of 640 acres in a square shape and could be further divided into proportional squares known as quarter-sections of 160 acres.

The Jeffersonian system allowed for a simple and easily grasped organization of the land to assist farmers in their ownership and cultivation of agricultural homesteads. Over time the section lines tangibly delineated property boundaries through the installation of conspicuous posts, rock piles, fences, roads, etc. Little did the ingenious founding father know that more than a century after envisaging a deft matrix for the new nation’s great expanse, his foresight would have the benefit of empowering a new class of adventurous pioneers who peered earthward in search of direction from conveyances in the sky.

The post office issued a list of specially compiled instructions to its pilots on the transcontinental route. For the Illinois and Iowa legs, the instructions advised that the proper course involved “keeping on the section lines and flying directly west.” Over a designated spot in Nebraska, the instructions called for dropping south one section for every 25 that were flown west. That would usher the pilots right into North Platte, a regular fuel stop.

Under the subheading “General Rules for Pilots,” the instructions wove common sense into the flying protocol. In total, there were 16 of these rules, one of which stated: “Maps shall be carried, unless the pilots are absolutely certain of the routes.” Another prohibited performing “stunts.” When landing, the rules gave mail planes “the right of way.” On-time service was a priority so the rules stated: “[T]he motor must be pushed against a headwind.”

Night flight was deemed necessary to get the mail delivered timely and efficiently. To facilitate operations after dusk, high-candlepower beacons were spaced equidistantly along the main airway. This gave the brave fliers bundled up in their open cockpits an innovative means to reach their designated waypoints on schedule.

In 1927, the success of the post office in managing the transcontinental route and the prospect of government subsidies for commercial operators served as twin inducements for airline companies to take over the route. In the preceding five-and-a-half years, the pioneering air mail pilots had flown 14 million miles along the route and transported more than a quarter of a billion letters.

During the depths of the Great Depression, when the fledgling air transport industry paradoxically transitioned into a permanent and powerful fixture in American commerce, a national air marker program emerged. The idea was that airports and towns across the land would be made visually identifiable for the sake of pilots passing overhead. Participating communities offered passive navigational guidance by having their names emblazoned on the rooftops of prominent buildings.

In 1934, Phoebe Fairgrave Omlie persuaded the Air18 AUGUST 2012 To a great extent, Cal Rogers used the “iron compass,” the extensive railroad line network crossing the United States, to provide reliable direction for his epic journey across North America in 1911.

port Marking and Mapping Section of the Bureau of Air Commerce to start the national air marking program. As a technical liaison between the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics and the Bureau of Air Commerce, she and Amelia Earhart developed a grid system that divided the country into 15-mile squares. The concept called for the placement of a marker at each point where the lines formed by the squares happened to intersect.

By the time she joined the Roosevelt administration in 1933, Phoebe was one of the country’s most accomplished women fliers. Her career in aviation began when she was a mere 17 years of age and danced the Charleston on the wing of Vernon Omlie’s biplane in front of an air show audience. Vern taught Phoebe to fly, and the two were married.

Slight and round-faced, Phoebe exuded high energy. She became a flight instructor herself and earned a transport pilot’s certificate, the first woman in the country to do so. In her pre-government years, Phoebe’s greatest recognition stemmed from her first-place finishes in major air races.

From her Washington office, Phoebe invited her cohorts to participate in the air marker program. Some of the greatest women aviators of all time were drawn into the effort. Blanche Noyes, Helen Richey, Nancy Harkness, Louise Thaden, and Helen McCloskey were field representatives who flew across the country to promote the program.

The Works Progress Administration, an archetypical New Deal agency, provided the funds for the program through state grants. Reportedly, two years after the program’s initiation, 30 states were actively involved and a whopping 16,000 air markers were on the way to being installed. The navigational benefits took root right away.

However, when Pearl Harbor was attacked in 1941, the proliferation of air markers turned suddenly into a detriment. Worried that Japanese and German bombers might use the air markers as signposts to strategic

targets, the government stopped the program. Many air markers were painted over to preclude the enemy from taking advantage.

After the war, the air marker program went back into operation with Blanche Noyes in charge. Eventually, though, the program was defunded in view of the fact that electronic airways had, at least ostensibly, usurped visual aids. Blanche was so committed to spreading air markers that she continued to champion the cause. The leading women pilots’ group at the time, the NinetyNines, carried on the tradition by painting airport names as well as compass roses on vacant tarmac.

Remnants of this passionate handiwork were still in evidence when I started flying. Indeed, on one of my first flights, an instructor pointed out the name of a town painted in bright yellow letters atop a car dealership only a mile-and-a-half west of the airport. “That’s an air marker. Look for them. They’re good landmarks.”

In the ensuing years, mid-rise apartment buildings went up on either side of the dealership, which eclipsed it and made the air marker visible from the cockpit only if you stood the airplane up on its wingtip at exactly the right moment while flying directly above. I remember one day taking a friend to the open-air parking deck of one of the adjacent apartment buildings to overlook the air marker. Not long after, in a sign of the times, the automobile showroom was converted to a savings-and-loan at which point the roof was tarred over, consigning one of the dwindling number of air markers to the memory of aging pilots.

Envision a journey with no markers of any kind, a voyage into uncharted seas. Through the 15th century, world maps stopped at waters not far from the edge of the European coast and generally depicted the great Asian land mass as landlocked to the east. The reigning view came from the work of 2nd century Greco-Roman astronomer-mathematician-cartographer Claudius Ptolemaeus (better known as Ptolemy) who devised the geographical and mathematical underpinnings for a map of the world that credibly displayed the parts of the planet which discoverers had uncovered up to his time.

Not until the four expeditions of Christopher Columbus in the period from 1492 to 1502, and the two Atlantic crossings of Amerigo Vespucci, believed to have occurred in 1499 and 1501, did cartographers have the wherewithal to add the contours of the Western Hemisphere to their truncated maps. The long-rumored world, the great unknown to the west of European shores, had at last been found; cartographic depictions of it followed, expanding and completing prior maps.

Martin Waldseemuller published his breathtaking World Map in 1507, and it shows the world in rough form as it is depicted in modern maps. The New World was not simply revealed, but, for the first time, it was named America, in tribute to the Florentine explorer. A nagging void in human knowledge, in the understanding of the outer reaches of our very habitat, was answered by a handful of voyagers daring enough to sail beyond the margins of existing maps.

Half a millennium later, a similar blankness, reflected in an even grander map, variously frustrates and tantalizes the futurists of today. The Gott-Juric Map of the Universe, first published in 2003, shows Earth’s core at one end and a radiation formation known as the Cosmic Microwave Background, the most distant thing humans can “see” in the universe, at the other end. The map’s two extremes are separated by about 13.7 billion years, the timeline since the Big Bang gave birth to the universe.

In its latest iteration, this sumptuous map portrays the richness of the universe with imagery of our solar system, the Oort Cloud, the Milky Way, and the Great Sloan Wall, among other astronomical marvels. But, like Ptolemy’s map, which went only as far as humans could see, this imposing diagram of the cosmos also comes to an abrupt stop at the opposite margin. If only we could see a little farther. What, if anything, is on the other side of that curtain of radiation so many light years away?

It is stirring to consider that an explorer worthy of his antecedents may one day sail on another momentous voyage of discovery and consummate this most extravagant of maps. Darting across the intergalactic divide at breakneck speed, future rockets will perhaps mimic mail planes, the Pony Express of a far-off tomorrow. Stars might serve as air markers to exotic destinations.

Aircraft Finishing Products STC’d for Certified Aircraft

Safe for You, Safe for the World, Safe for Your Airplane

For Certifi ed Aircraft, Stewart Systems is FAA approved for use with any certifi ed fabric. Superfl ite, Ceconite or Polyfi ber EPA Compliant Non-Hazardous Non-Flammable Stewart Aircraft Finishing Systems 5500 Sullivan St., Cashmere, WA 98815 1-888-356-7659 • (1-888-EKO-POLY) www.stewartsystems.aero

On an earthly scale, my memorable destinations have included Chicago’s wonderful if ill-fated lakefront airport, Meigs Field, which was an air marker unto itself. On final approach, I glided alongside one of the most magnificent of urban skylines. Then I walked briskly through Grant Park to Marshall Field’s when the resplendent department store went by that name, bought a token of some kind to affirm the visit and, in advance of an approaching front, hightailed it back home in time for dinner.

Another time, on one of those gilded summer days that seem to run to eternity because the sun dallies above the usually impatient horizon, I landed at a grass strip sandwiched between two tiny farm communities where the local pilots were holding court. They quickly sized me up, and one of the old gents took pity on the greenhorn with tent and sleeping bag because, he said, the mosquitoes would be out in full force at night. He and his lovely wife boarded me in their guest room.

Before turning the lights out in the vintage clapboard farmhouse, my host walked me over to the barn. He cracked open the door and the shimmering incandescence of a rafter-mounted lamp cast a warm sheen over a stately cabin biplane. It was a Waco from the golden age that awaited restoration and a return to its intended realm of the sky. “Got a Pratt in it?” I asked. “Nope, a Jake,” he replied. Aviation’s linguistics has a way of cementing the bond among those who fly.

My new friend waved goodbye the following morning as I tipped my wing to him. A relationship was born between irremediable devotees of old flying machines. This constituted a movable marker, the kind that remains through all future travels for it is embedded everlastingly in one’s heart. From that time forward we stayed in touch, trading flying stories, hopes and frustrations as friends do. Years later my wife, Mary, and I had the privilege of reciprocating the hospitality that my friend and his wife had accorded me by putting him up as our guest during his visit to our grass strip.

When Mary and I established our airfield in the late 1980s, the few remaining air markers in southeast Michigan were precious vestiges of the era that spawned unremitting enthusiasm for aviation and that generated many classic designs like our Stearman. The closest air marker was painted atop a tin-roofed factory in a small town six miles to the north. I imagined passing pilots glancing below in an earlier time to get a fix on their position. Alas, just as we settled into our airfield the factory underwent a renovation and one day soon afterwards as I swung over the town those once durable and reassuring letters were no more, the roof having been transfigured into a blank slate undistinguishable from any of the other roofs in town.

Nevertheless, I fly up that way every chance I get, and when I’m over the factory I bank for an unobstructed view of the roof, hoping that the air marker will magically reappear. The roof has remained imper20 AUGUST 2012

vious to my admittedly improbable wish for more than two decades now, but I circle it anyway. It doesn’t hurt to dream; indeed, it keeps our faith alive.

As it happened, we found spare crimson-toned bricks in the aftermath of our construction. Mary asked a tilesavvy friend to help her lay those fortuitous leftovers on a pearly gravel base at the north end of the property in a sequence that would spell out our last name in block letters, just as it appears next to the magenta circle that denotes the airfield on the pertinent sectional aeronautical chart. Unless you know where to point your eyes, the letters arrayed on the ground are hard to spot from the cockpit, but if you fly low and slow, which are the natural parameters for antique aircraft, it’s possible to catch sight of and discern the name. I guess you can say we have an air marker.

To the west of the custom-crafted brickwork is a mixed stand of pine and apple trees and to the north and south are Mary’s wildflower beds in a checkerboard pattern that turn all aglow in early summer. To the east, prairie grasses sway in the gentle breeze. Something tells me that Phoebe, Blanche, and their coworkers would be pleased.

In a larger sense, the question of where we are going is predetermined. What really matters is how we get there, the air markers we choose to follow. For all our peregrinations, the scrambling to locate strange waypoints far from home or to retrace familiar routes over the same worn patches of the shrinking countryside, we remain occupants of what a favorite philosopher-pilot branded a big spaceship that hurtles through the universe on a steadfast course beyond our control. Despite periodic pretensions to the contrary, we all share a common trajectory. Our destinations are the same.

Sources and Further Reading Adams, Jean and Kimball, Margaret with Eaton, Jeanette. Heroines of the Sky. Garden City, New York:

Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1942. Gott, J. Richard and Vanderbei, Robert J. Sizing Up the Universe: The Cosmos in Perspective. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2011. Harwood, Jeremy. To the Ends of the Earth: 100

Maps that Changed the World. Cincinnati, Ohio: F +

W Publications Inc., 2006. Leary, William M. (Editor). Pilots’ Directions: The

Transcontinental Airway and Its History. Iowa City,

Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 1990. www.Ninety-Nines.org/airmark.html Planck, Charles E. Women with Wings. New York:

Harper & Brothers, 1942. Wilson, George Tipton. “The Flying Omlies.” Aviation

History, July 2002.