16 minute read

The Vintage Mechanic

BY ROBERT G. LOCK

Aircraft covering, Part 2

In part 1 of this subject we explored the beginnings of aircraft fabric covering dating back to the WW1 days. It seems like it took a world war to rapidly advance the Aeroplane and such was WW1. Speeds and maneuverability increased dramatically and government sponsored research made advances in design, materials and processes. It was now time to apply the Aeroplane to civilian aviation.

In the early 1920s, training and combat ships were occasionally seen flying about, particularly those machines used by the barnstormers. Curtiss Jenny and Standard J-1 were the favorite ships at the time, but covering materials remained the same as in WW1. There were no regulations or requirements for civilian aviators and their ships and, as we have seen, the covering cloth was not protected from damaging ultra violet radiation from the sun. With government taking control of civil aviation in 1927, new regulations were written, including the covering materials for ATC’s ships.

From Aeronautics Bulletin 7-A dated July 1, 1929, comes the following information on the properties of materials. “The materials used in aircraft structures must be of the best. Since it is impossible at the present time for the department to draft a complete set of specifications or to inspect and approve all materials to be used in aircraft, it is accepting those [materials], which conform to the specifications of the United States Army or Navy, the Society of Automotive Engineers, or other recognized standard. The use of materials of inferior quality or of those which experience has shown to lack uniformity of quality or strength will be regarded as sufficient cause for withholding approval of a new design or for canceling approved type certificates or licenses already granted.” Therefore the specifications for aircraft cotton cloth and dope remained the same after the end of WW1.

Aeronautics Bulletin 7-H was issued January 1, 1936 and contained data that could be applied for alterations and repairs to certificated aircraft. Illustration 1 is a direct copy from AB 7-H regarding aircraft fabric covering.

NOTE: For more detailed information relative to fabric covering and stitching, reference should be made to Army and Navy specifications on this subject.

When the Bureau of Air Commerce evolved into the CAA, Civil

Aeronautics Manuals (CAM) began to appear. Aeronautics Bulletin 7-H created in 1936 evolved into CAM-18, “Maintenance, Repair, and Alteration of Certificated Aircraft, Aircraft Engines, Propellers, and Instruments.” From a June 1, 1943, CAM 18, table 6 details standards for textile materials and supplies used in airplane covering. Airplane fabric specification is now AN-CCC-C-399-1, that specifies 80-84 threads per inch in both the warp (parallel to the selvage edge -length) and fill (90 degrees to the selvage edge) with a tensile strength of 80 pounds per inch warp and fill. This was Grade A cotton aircraft fabric. Specification for this cloth could also be found in CAM 04.415. Also detailed at this time was an intermediate airplane fabric cloth whose specification was contained in CAM 04-415-A3. The CAM specification for Grade A cotton fabric eventually gave way to a Technical Standard Order, which is a written specification published by the FAA as a minimum performance standard for specified materials, parts and appliances used in certificated aircraft. The TSO indicates to the purchaser or user that the material or part meets minimum quality standards. In later revisions of CAM-18, cotton aircraft fabric became known as TSO-C14 and TSO C-15, which specified (among other things), a minimum new tensile strength of 65 pounds per inch warp and fill for intermediate TSO-C-14 cotton fabric and 80 pounds per inch warp and fill for TSO-C-15 cotton fabric. However, the TSO also indicated the minimum tensile strength for deteriorated fabric-70% of the original new strength for each. Thus the minimum strength for C-14 fabric was 46 pounds per inch and for C-15 fabric it was 56 pounds per inch. This standard of deterioration is still valid today even with the advent of lighter and stronger synthetic Dacron material. Grade A TSO C-14 (SAE AMS 3804) intermediate cotton fabric was apILLUSTRATION 2

proved for light aircraft with wing loadings less than 9 pounds per square foot (PSF) and Vne (velocity never exceed) speeds of less than 160 mph. Its deteriorated strength was 70% of 65 pounds per inch, or 46 pounds per inch pull. Intermediate Grade A fabric was meant for the post WW2 light aircraft that were built in large numbers beginning 1946. Illustration 2 is my 1946 Aeronca 7AC in flight over the rice paddies near Merced, California in 1972.

Grade A TSO C-15 (SAE AMS 3806) cotton fabric was approved for use on all aircraft and required on ships with a wing loading greater than 9 pounds per square foot and a velocity never exceed of 160 mph. Its deteriorated strength was 70% of 80 pounds per inch, or 56 pounds per inch pull. Grade A C-15 fabric was used on all high speed and/or high wing loading aircraft, such as this Beechcraft D-17S ship shown in illustration 3.

The Grade A cotton fabric process was used until synthetic fabric processes were introduced. But before we get into the synthetic processes, let’s step back to look at the cotton or linen process in some detail, since it is a dying art. I began

ILLUSTRATION 4

covering Stearman wings in 1956 when still in high school. All there was at that time was Grade A TSO C-15 cloth, which was manufactured by either Flightex or Reeves Brothers. Cloth came in widths of 36", 42", 60", 69" and 90". Pinked edge surface tape (which was the same grade as the fabric) came in widths of 3/4", 1", 1-1/2", 2", 3" , 4", 5" and 6”. Tapes could be purchased either raw or pre-doped (the pre-doped tapes were blue in color). All surface tapes had the standard 8-pinks per inch along the edge and were designed to keep the tape edges from unraveling. Tapes 34 SEPTEMBER 2012

came in 100-yard rolls, were called “pinked edge surface tape” and were to AN-C-121 specifications. Rib lacing cord was either cotton (natural color) or linen (grey color) and were classified at #6 (6-strands) or #9 (9-strands) and were coated with bees wax to prevent deterioration throughout the life of the fabric, which was 6-10 years depending on whether the ship was stored inside or outside. In some cases the fabric lasted past 10-years, particularly if the ship was painted a light color and stored inside a hangar.

Dope was still clear Nitrate (specification AN-TT-T-256) and could be purchased in 1-gallon, 5-gallon or 54-gallon containers. Butyrate (cellulose acetate) dope (Navy specification D-23) was packaged in the same size containers and was more expensive than nitrate. Appropriate thinners were either nitrate or butyrate and were packaged in quart, gallon, and 5-gallon or 54-gallon drums.

Pigmented dope came in butyrate with many standard and a few special colors. Here we find familiar names, such as Insignia Red, White and Blue, Piper Cub Yellow, A & N Orange Yellow, Waco Gunmetal Gray, International Orange, Stinson Red, Stearman Vermilion, Travel Air Blue, Fairchild Blue, etc. Illustration 4 is a duplication of the Berry Brothers color chip chart of the 1920s and 1930s.

Application of cotton fabric to wings was accomplished in one of two methods—blanket or envelope. Using the 69" or 90" wide cloth it was possible to blanket cover wings with a chord of 60" or greater. For attaching the fabric cloth to the structure, a lacquer base adhesive was used. One such adhesive was called “Airlaq” which was a brown color and smelled like lacquer and acetone. With an envelope, the covering was machine sewn then slipped over the structure. It was then either hand sewn or glued at the open end. Once the adhesive had dried the covering was wet down using a sponge and a bucket of tap water. When the water tautened the fabric it was almost as tight as if several coats of dope had been applied. The surface was wrinkle free and would sound like a base drum when tapped with a finger. In some cases, dope-proof paint was applied to the structure before installation of the cloth. The paint was generally white in color and was applied to the structure by brush or spray to those portions of the structure that would come in contact with dope, thus lifting the protective coating on wood parts.

Once the fabric had dried completely from the water shrink, the first coat of dope was brushed on

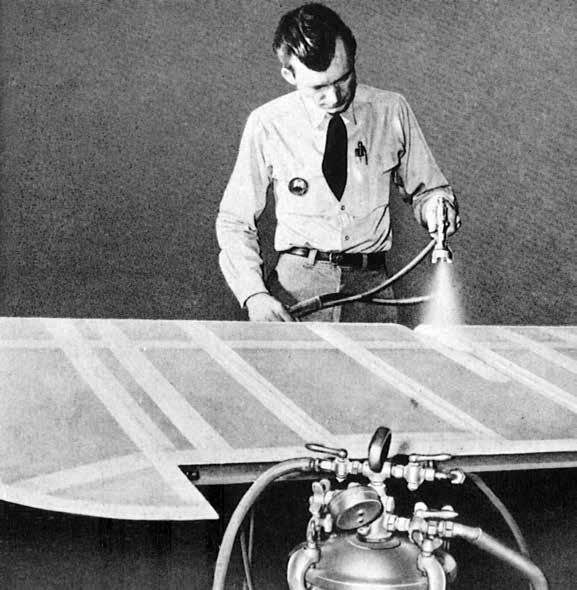

to thoroughly saturate the fabric on both the outside and inside and close the pores of the cloth. Berry Brothers recommended using full wet brush coats, well saturated with dope and applied evenly. If the fabric had tautened sufficiently, reinforcing tape was glued over rib capstrips and the wings were rib laced. Straight needles from 6" to 18" in length were commonly used, as were curved needles that ranged in size from 2-1/2" to 4". Once the rib lacing was completed, surface tapes were doped in place, 2" wide tape being commonly used over wing ribs. A total of 4-coats of clear nitrate dope was applied to early ships, 2-coats by brush and 2-coats by spray (a single coat of dope by spray consists of a cross-coat), with sanding in between coats. Illustration 5 shows an old photograph of a well-dressed craftsman spraying clear dope without the use of a respirator. Then the silver pigmented dope was applied to block the rays of the sun. Silver pigmented dope was mixed by adding 1-1/2 pounds of fine aluminum powder or a 1-pound can of silver paste to 5-gallons of clear dope (either nitrate or butyrate). Dope was thinned for spraying from 20% to 50% depending on whether it was high solids or medium solids. Proper spraying consistency came from

EAA Vintage Aircraft Association Cub Anniversary Merchandise

ILLUSTRATION 5

These Cub anniversary items were a huge hit at AirVenture 2012. For a short time we have a limited number of 75th Anniversary caps and duffles available. This duffle won’t get lost in your airplane, it’s beautiful color stands out. Embroidered logos on both sides of bag. Cap has three beautifully embroidered logos. Order yours now, don’t put it off. Call 800-564-6322 or online at www.shopeaa.com/vintage.aspx

CONTACT US TODAY!

TOLL FREE: 800.323.0611 TEL: 618.931.5080 FAX: 618.931.0613 SALES: sales@superflite.com WEB: www.superflite.com

Scan this QR code with your smartphone or tablet device to view our complete line of fabrics, tapes, and finishes.

experience in mixing—if the dope was too thick, orange peel was the result.

If the dope were too thin, not enough dope would be applied to the surface. Minimum number coats of silver dope was two, however I spray a minimum of 4-cross coats to the surfaces, and 5-cross coats if the final color was silver. With ni trate or butyrate dope there was a waiting time between coats of a minimum of 45 minutes and longer if the temperature was cool. Mini mum application temperature was about 70 degrees F and low humid ity was most desirable. High humidity would cause the dope to blush, which caused some painful prob lems as the blushed dope had to be sanded off or burnt off using butyl alcohol. The remedy to blushing was to not allow it to occur! Blushing (which is the combining of wet dope with water from rapid cooling wet air) causes a clear surface to turn to a “milky” color and for silver dope to turn to a “grey” color. Blush re tarder could be added to the dope to slow down the drying rate so the air just above the surface would not be cooled by rapidly evaporating thin ners, thus reducing the air temperature to the dew point.

Once the silver dope had dried thoroughly it was lightly wet sanded. Here a problem could oc cur if too much silver dope was sanded off. I always used more than the minimum number coats of sil ver dope recommended, either by the manufacturer of the dope or the CAA (now the FAA). The minimum number coats of dope on Grade A fabric is given in AC43.13-1A and is different than what I used as a guide.

Illustration 6 is from the 1946 Air Associates Aviation Supply Catalog No. 19 and details Berry Brothers recommendations for applying a pigmented dope finish with either nitrate or butyrate dope. The Grade A cotton and Irish Linen fabric processes are rarely used now, with most ships being covered where the owner wants complete authentic restoration or a museum quality job. In the very late 1950s were borne the synthetic fabric processes; the first being Ceconite using dope as a filler and pigmented butyrate dope as a finish. This process, while closely resembling cotton and linen, was easily adapted by those who

had many years of experience with the old covering methods. About 1960, Ray Stits introduced a process he called Poly Fiber. Both the Ceconite and Poly Fiber process used unshrunk woven Dacron material of various weights. Since these, and other processes, was a change to an aircraft’s Approved Type Certificate they required Supplemental Type Certificates (STC) and the first airplane of a particular type had to be FAA Field Approved because replacement of the fabric with other than original is a major alteration. Once the first airplane of a certain type was approved it was placed on the STC holders master list and all other recovering jobs could be approved on FAA Form 337 by the A&P with IA who was overseeing the work.

The synthetic covering processes (all of them) have a Procedure Man ual that must be followed closely. Only certain bits of information in the current AC43.13-1B can be used with these processes. The Procedure Manual will state which portions of the AC apply to the particular process.

Aircraft fabric covering has come a long way since the first days of linen cloth and nitrate dope with no protection from the ultravio let sun’s rays. Now there is lifetime covering process available to the owner. The only question is—Will the structure, (particularly wood) last as long as the fabric? Ah, that is the question that many mechanics and inspectors will deal with at ev ery Annual Inspection.

One final thought regarding synthetic covering processes—the application of UV blocking material is just as important as Grade A. We’ll have more on that next issue.

RGL, April 2009

REFERENCES: AIR ASSOCIATES SUPPLY CATA

LOG NO. 19, dated 1946 AERONAUTICS BULLETIN 7-H, dated January 1, 1936 CIVIL AERONAUTICS MANUAL 18, dated June 1, 1943 AC43.13-1B, Change 1, dated 9-9-98

NEWS

continued from page 3

factured blades available is an important part of keeping the world’s fleet of vintage aircraft in the air and flying safely.”

The new hubs and blades are useful on a wide variety of radial engine powered aircraft including many famous names such as Boeing, Ford, Stearman, Travel Air and WACO. The new hubs and blades carry FAA Type Certificate Number P32BO.

For information contact:

MT-Propeller USA, Inc. 1180 Airport Terminal Drive

DeLand, FL 32724 ph. 386-736-7762 http://www.mt-propellerUSA.com e-mail: info@mt-propellerUSA.com

Grass Runway at AirVenture

In a year full of new features and attractions at EAA AirVenture, thanks to the efforts of VAA and EAA staff, we were able to offer a grass landing strip during the convention, making landings safer and more efficient. The grass landing strip is perfect for aircraft with a tailwheel or tailskid and is located southwest of the approach end of runway 36L.

Because of the configuration of the airport and obstructions near the runway, only landings to the north are allowed while the airport is using a 36L-36R configuration; no landings to the south are permitted. To gain permission to land on the strip, pilots must first obtain a copy of the special approach procedure. As next year’s convention nears, we’ll publish details on how you can use the grass strip.

Here it is in a nutshell; pilots wishing to land on the strip must communicate with the Oshkosh tower via two-way radio. On the day of arrival, a telephone call must be placed to the tower within about one hour’s flying time from Oshkosh to obtain permission to use the approach and land on the strip. To keep the possibility of the wind or traffic conditions impacting the ability of the tower to issue a clearance, we’d suggest an early morning arrival (per the NOTAM, the airport opens to ar rivals at 0700). Pilots must also be familiar with the EAA AirVen ture NOTAM, in case the landing clearance must be canceled and a landing on the paved runways is required. The approval by the FAA and airport management came very late in the planning for the 2012 event, so it was difficult to get the word out so that more pilots could use the strip, but we look forward to working with the Agency and airport authorities to work out an acceptable opera tional plan for the 2012 fly-in.

Cubs 2 Oshkosh

What a great week! Thank you to the Piper Cub owners who flew to AirVenture Oshkosh 2012. The flightline was just what we hoped for--a “field of yellow” as aviators celebrated the iconic aircraft’s 75th anniversary at Wittman Regional Airport. Our thanks to all of you who helped make this a wonderful week by flying your Cubs to Hartford, Wisconsin and Oshkosh. We also want to thank our sponsors, Piper Aircraft and Univair for their invaluable support, which made it possible for the commemorative hats and barrel bags presented to the pilots, as well as support for our annual picnic and dinner, plus signage and the presentation of the historical artifacts displayed by the Piper Historical Museum and Harry Mutter.

We want to recognize the city of Hartford for their incredible “welcome!” as well as Steve Krog, Dana Osmanski and the 85 hard working volunteers who worked all weekend in Hartford to make the gathering so special. Rick Rademacher got the ball rolling early and then kept it going us ing the Chapter website page EAA created for Cubs 2 Oshkosh, and here in Oshkosh VAA direc tor Dan Knutson, his wife Mary, along with Jess Krall and Leroy Brandt stepped up to help orga nize and welcome the pilots as they arrived in Oshkosh. Ron Alexander put together a ter rific evening program at Theater in the Wood featuring two of Cub world’s brightest starts, Piper historian Roger Pepperell and Cub restoration expert, the “Cub Doctor”, Clyde Smith Jr. (Who also is this year’s VAA Hall of Fame inductee).

We’ll have more on the Cubs 2 Oshkosh celebration in an upcoming issue, so until then, please accept our simple “Thanks!”

VAA Election Results

During the general membership meeting held the morning of July 31, 2012, the following were elected by the EAA Vintage Air craft Association members: President, Geoff Robison; Secretary, Steve Nesse; Directors, Ron Alex ander, Steve Bender, Dave Clark, Steven L. Krog, Jeannie Lehman Hill, Robert D. “Bob” Lumley, Joe Norris, Tim Popp. VINTAGE AIRPLANE