VLR

VIRGINIA LITERARY REVIEW

Spring 2024 / Volume 46 / Number 2

The Virginia Literary Review

Contact Us!

www.virginialiteraryreview.com

Spring 2024 Masthead

Editor-in-Chief

Isabel O’Connor

Production Manager

Miriella Jiffar

Poetry Editors

Mia Tan

Maria Rahmouni

Anastacia Reynolds

Amasa Maleski

Ebtesaam Abdul-Qudoos

Aoife Arras

Khadijah Aslam

Prose Editors

Sofia Heartney

Stasia Winslow

Audrey Cruey

Elizabeth Parsons

Kaitlyn Kuckinski

Portia Papagni

Chloe Ross

Peter McHugh

Art Editors

Katie Huffman

Alyssa Zhang

Founded in 1979, The Virginia Literary Review is the oldest undergraduate-run literary magazine at the University of Virginia. The editorial staff considers literary and visual art submissions from students across colleges and universities in the Commonwealth of Virginia during the first three-quarters of each term. The VLR is published twice a year in the fall and spring. For more information and to view past issues, please visit our website:

www.virginialiteraryreview.com

As of Fall 2023, the Virginia Literary Review is a formally Contracted Independent Organization (CIO) at the University of Virginia. The magazine is not, however, affiliated with the University or any of its departments, and is completely liable for itself, its members, and its activities.

Contents / Spring 2024

Poetry

January Thoroughfare

Cicada’s Requiem

Faces

The Moon’s Children

River Mouth

Bonsai Tree with a Single Fruit

Connie

Once more the rain, with a song

Prose

The Korean Label

Starving Hysterical Naked

Matryoshka Dolls

My Turn Stop, Go Slow

Shousang

Visual Art

The Mill (dedicated to Madison Hinton’s Grandomother)

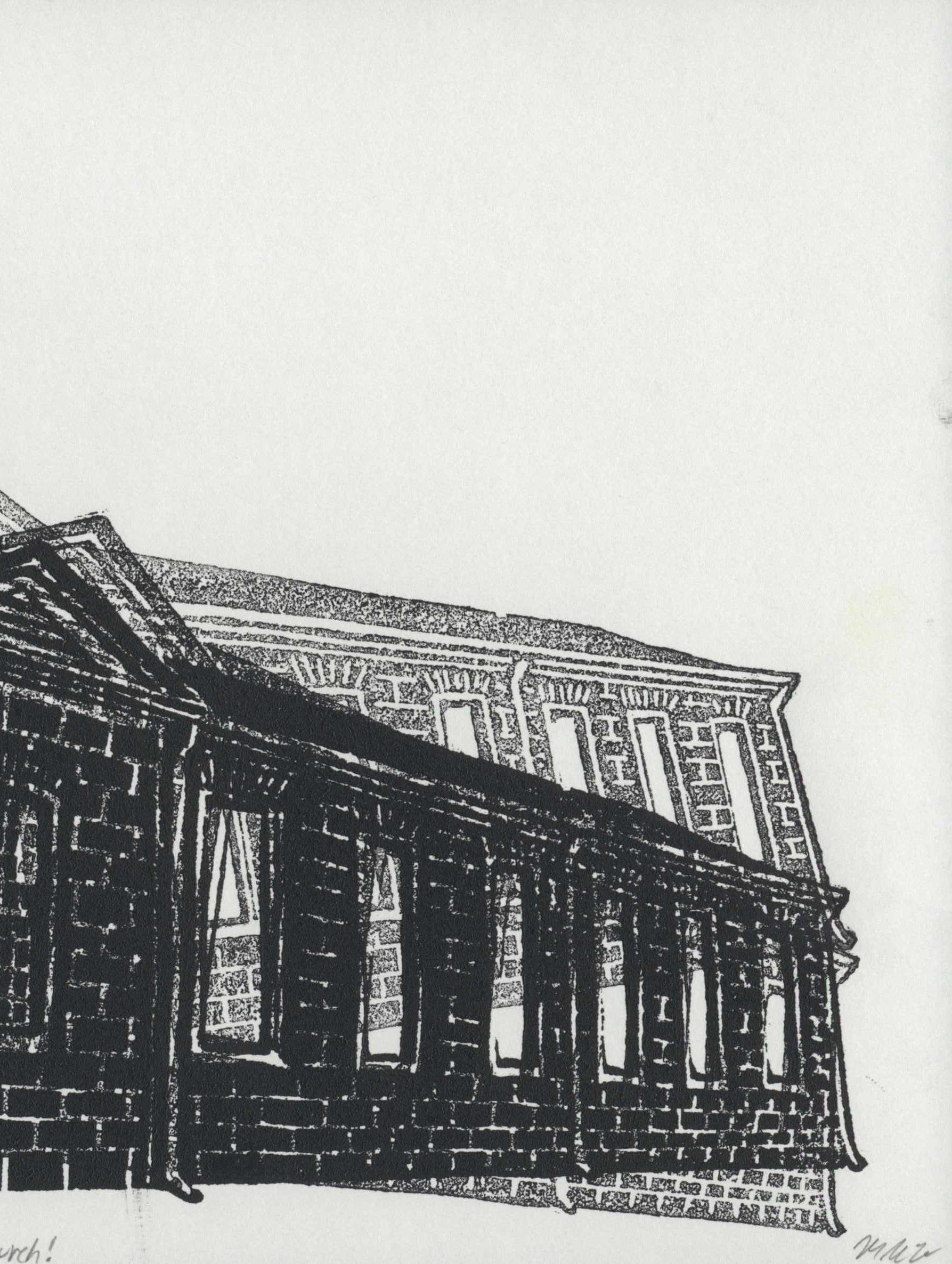

Headed to church

The sword in the stone

Disorder upon arrival

Artificial radiance

Valentine Cotton

Sophie Uy

Connor Smith

Alayda Flick

Alyssa Zhang

Reece Steidle

Oliver Meek

Pari Sabti

Samuel B. Kim

Zoey Young

Chloe Ross

Ariana Jobst

Emily Rooksby

Sophie Uy

Madison Hinton

Madison Hinton

Candyce Harrell

Alyssa Manalo

Alyssa Manalo

Copyright 2024. No material may be recorded or quoted, other than for review purposes, without the permission of the artists, to whom all rights revert after the first serial publication.

January Thoroughfare

The bright warm squeak, full, running like water over the tisk-tip-tack of the drums, distant doors, and voices, intermittent, like last Sunday night. Last Sunday night I took the skin of your shoulder between my teeth and held it there, tasting the nothing-taste of your skin. Tracks rolling by like boxcars. The wind tossing itself about harsh and selfassured. From nowhere a break for the solo, everything crashing and commencing together all at once.

Cymbals like the crunch of snow, a quick and frenzied sort of dance over stones and sticks. The river still rushing by, brassy and constant. Sunday to Sunday–tonight we listen to jazz and brave the cold in cheap mittens, cheaper joys, each brush of our hands like a telegraph in progress.

By Valentine Cotton, 2nd year undergraduate at the University of Mary WashingtonAuthor’s Note: “I wrote this sitting in a room with some of my favorite people in the world. This one’s for you, and you, and the fact that it’s not January anymore.”

Headed To Church by Madison Hinton, second year at University of Mary Washington

Artist’s Note: “Thank you to my professors, family, and friends for believing in me and supporting me.”

Cicada’s Requiem

Cicada’s Requiem

You will never know music like I did. Not sing or die, but sing & then die. Look, I’m not angry with you but the maple, how I watched a-chí inhale dew from its roots like she had no option—she had no plan B, only the plan A

given to us by a mother we never met. Only the plan A molded into our faces, white & innocent. Not like you, who

can shed your future like a second skin. I loathe you not for my failed life but because I don’t know if you’ll live yours.

I don’t have secrets. I am trying to say you won’t understand what you don’t listen to. You’ll block out our songs—

you’ve done it before. Walked past a-chí’s aria & asked the vendor, shūshu can I get the yú wán tang please With

extra là yóu too. Scraped loose chilis from your chopsticks while a-chí fell to the maple’s feet. Trampled over a-hia’s wings on your walk home while I flattened myself on the branch to niente. Dawn broke through crinkled leaves

& my dirge got lost in translation; my weeping, a war anthem.

In a way the maple was a mother without maternal instinct. It didn’t give, but we took— warbled gānbēi, licked sap from its roots. Our bodies, poor man’s huángjiǔ, heady

& brown in the moonlight. We were raising ourselves to die; I could only watch as a-chí & a-hia became professional alcoholics.

Then music: seventeen years old was my concert premiere. It was clinging to the maple like its leaves wouldn’t also wither

& knowing my life was fraught because I didn’t ask for it.

By Sophie Uy, 4th year undergraduate at James Madison UniversityAuthor’s Note: “This poem, written in the voice of a (rather angry) cicada, holds a special place in my heart. I wanted to capture how we (humans) are made for endless possibilities, through the lens of a cicada’s inevitable life-death cycle.”

Artist’s Note: “This work is one of many illustrations I’ve made and is inspired by a novel-in-progress that I’ve been working on for far too long. Meet Alek, the heroine of our journey.”

Faces

bare with me—take me literally for a moment— two worlds—yours and mine— I find them so similar—so familiar—let’s talk about yours—to me it is all surface—beautiful shining surface—what shine—reflection— burning—a film projector— flashing—catching sun—seems alright—doesn’t last—

in a flash it is all wrong—this frame I hold on to—wonderfully confused—never ever satisfied—you are not watching—surface refuses to be confused—preferring instead to shape—to shine—to die in front of me and shine again—to keep shape— indifferent to itself—to eye— to me

By Connor Ryan Smith, 4th year undergraduate at the University of VirginiaAuthor’s Note: “For my dachshund, Sullivan, who loves to lick people in the face.”

“starving, hysterical, naked”

After Allen Ginsberg and Zoe Leonard

I saw the best minds of my generation sucked into a stupor, suicidal, squandering their success, screaming for a second of selfhood, swallowing pills, turned to saints & sinners by the evening news, sacrificed at the altar of our great american bullshit, swallowed by the white whale of this loathlove spiraling newscycle, twentyfourhours trapped by the television-twitter-telephoto lens; fisheyed, feasting, frightened, festering wounds, wounded in the whitewashed wake of another shooting, another supreme ruling, another ranting raving ruthless speaker shouting for their heads & hearts, shunning them from public spaces, killing them at home. I saw candlelit vigils for companions & colleagues & comrades, for kids marching in streets, murdered in schools, martyred in speeches of grieving parents and peers, of distant peerers appalled-agonized-apathetic, of savvy politicians split-sidesing side-stepping so-soing saying what needs to be said & nothing at all, saying anything, saying–

I saw the glittering lights of a great city reflected in piss on the street, glowing neon mirrored in mcdonalds windows, shimmering sides of skyscrapers see-through as we watched another jumper, brilliance blinking out of my brother ’s eyes, remembering a friendsiblingclassmate teetering midair;

I ate that nasty hospital food dry & disgusting beside them, teary, tasteless, taking shallow breaths over paper plates,

saw them throwing up across linoleum halls, throwing chairs across cramped rooms, throwing back bland meal replacements & horse pills under the big brother eye of a stern nurse (“open up, stick your tongue out”) until they emerged rehabilitated, resigned, relapsing months later, finding themselves (back) in silent streets & small cities, sick & tired, saved & surrendered to stresses of life, down $7000 & 3 months & “good graces” of health insurance companies, down the trust of families, down school & social life, down to the last ounce of sanity

Millions of manic eyes fixed on monolithic megacorporations, meritocracy mythos, megalomaniacal millionaires made monarchic;

I saw sofa-sleeping savants, stranded & ashamed to be charity cases, crowdfunding food & community kitchens, kicked out, carrying selves across states, staking claim to spare beds & benches, begging brothers to ship belongings, broken cars, canceled cable, lives left to lovers– gay, genderfucked, going looney as bugs bunny, bereft, babbling sweet everythings in sick-spoiled ears, airing grievances like laundry in grimy low-rent living rooms, writing love letters in long-day lazes on post-it note pinboards, paying landlords late or begging for a bargain; bitter at former friends’ freedom, monied mothers lubing up life as it fucked them over, left laboring long hours ‘til their bodies gave out, discarded disabled disposed, disillusioned in desk jobs, desperately searching for a source of income, toiling & taxed, axed by spoiled daddys-money brats & productivity police (always a john and never a hooker), pissed & pleased to leave, longing for easy living–

I saw every-brilliant-body I knew born naked, now blastedbrokenbaked, beaten down & dying for contact, crashing cars, cracking apart, parting seas, seeing double, doubly troubled by the mess we call home.

By Zoey Young, senior at the University of Mary WashingtonAuthor’s Note: “For my favorite languid lovers, my starry-eyed little brother, and the girl in my poetry class who told me this “really meant something“ to her.”

The Moon’s Children

They say beware the Moon’s aquatic kin whose maker opened gates to aliens, amused. If human action mints new sin, His children roast the blood of sapiens. So, humans, we, retreat from creature eyes; Attempts to dock my hungry store still failed. They warned me to only look to the skies, lest a stare’s siren caught and my soul jailed.

And yet, I looked down falling to the sea; when my ship wrecked, and I to start again, the trap laid brought a siren to save me. Claws edgeless repaired my heart and ship’s sprain, and if kind eyes commanded to kill free, I graciously accept the Moon’s sure pain.

By Alayda Flick. 3rd year undergraduate at GMU.Author’s Note: “I wrote this sonnet for a required English class unrelated to poetry, a story about a traveling shopkeeper miraculously and recklessly falling into a siren’s heart. Thank you, Kris, for sharing your ocean with me.”

Matryoshka dolls

In the room on the opposite corner from my childhood bedroom, inside a perpetually-open bookcase filled with high school yearbooks and dogeared novels, sitting on the second highest shelf is a matryoshka doll. Sometimes there is only one, and sometimes there are many. But they are always themselves.

It’s been a long time since I’ve played with the dolls in the same way that I did as a kid. Back then, I assigned each size a different familial role. Because that’s the only thing they could ever be to me: a family. The oldest was the great grandmother, of course, with her daughter and then her daughter and then her daughter; I’d throw in some sisters in there, as well, if my brain ever lost track of how many daughters a daughter of a great grandmother should have. I had never seemed to question why there were no men in this small little family of mine. Maybe because I was the daughter of a daughter of a daughter, it had never made any difference to me.

But, for some reason, now, as an adult in the room I’d only ever existed in as a child, I find myself looking up at the doll, singular this time. I no longer have to go fetch the step ladder to get it, or even reach up on the tips of my toes. In fact, I don’t even have to straighten my arm all the way before the doll is already wrapped within my greedy fingers. The dust comes away from its surface slowly, as if with every stroke of my sleeve I have to convince it to complete the transferral, implore it, beg it. But then it relents, and the doll from that bright childhood vision is there once more, its vibrant blues and blushes welcoming me back into my memories.

My eye catches along the seam of the doll, right around the widest part of its curving body. Around either side of it my hands grip the doll, and begin to slowly turn in opposite directions. But then, after a moment, I have to give that up, and a franticness takes over my movement. When I was younger a mother’s hands had always opened the doll for me; the daughter had never had to realize how much force it takes to reveal the family. When even that desperation does not work, I dig my fingernail into the crack, ignoring the blood that begins to trickle out from under my nail and travel in a thin trailing line down my wrist. But then I see it: raw, unpainted wood. And I have never been happier to see a sight.

When the first daughter is revealed, I meticulously put the mother back together so that the two sides of her seam line up perfectly, not wanting her to remain severed in half for too long. I stop for a moment to catch my breath, staring at this eldest daughter’s face. She looks nothing like me, and yet we are both elder daughters, as was my mother, and as was her mother before her. Besides the smear of my own blood across her face, she looks exactly like the mother I had just pulled her out of. Every exact feature is the same, except that, now that I am looking at her closer, maybe the lineart is slightly different around the edges of her flower. Is that what I look like, placed beside my mother? What does my mother think, placing herself beside her own mother? Her mother died at forty one; my mother is now exactly twenty years older than her. Would they have aged the same, with the same lines drawn upon their faces by a fine black brush? Will I look the same when I outlive my own mother?

When I can wait no longer, I repeat the process. I repeat it again and again, assisting in the births of countless daughters, my fingers shaking and stained red from the strain. I do not even notice when I have come to the last daughter. I almost break her apart, trying to find a seam that isn’t even there, until I realize that, unlike all those that came before her, she is whole. I stare, spellbound at this youngest daughter, who conceals from my sight only the smallest part of my palm. Why is it that, out of all of the broken daughters, all of the broken mothers and broken grandmothers and broken great grandmothers, only the youngest is unbroken? Only she is whole, still untouched by the dividing forces that are enacted upon us during the course of our life. I do not know why she is the only one that is able to remain whole. And, even with the bodies of all of the older daughters and mothers and grandmothers and great grandmothers scattered around me, I don’t think I ever will.

By Chloe Ross, 2nd year undergraduate at the University of VirginiaAuthor’s Note: “This piece is based off of an actual set of matryoshka nesting dolls that I’ve had since I was a child. As I grew up, my view of these dolls changed from simply seeing them as toys to seeing them as representative of my familial connections; it was those changing perspectives and emotions that I wanted to reflect within this piece. I hope you enjoy reading!”

CONNIE

Last December, flames crept up the walls of the house. They swallowed the attic and chewed on the kitchentwisting like fate.

I imagine the firemen came with hungry hoses, gunned down the flames and washed away the embers left mounds of sunken clutter wailing.

Come summer, the drywall is weak, the floors blackened, the windows boarded up, the stench of mold and dog swimming in the heat.

Connie watches daytime TV. Her husband brings a sandwich, and the missionaries work to patch the house’s dignity. They put new flooring in the bathroom with the balancing sink and siding on the front half of the house.

She’s on the couch. Her bad ankle resting on a pillow. She’s trapped but clinging onto home, like flowers to dirt or children to mothers.

She loves to chat, but you hear the pride crackle in her voice. It used to look like a palace in here, ya know.

She shares polaroids of Christmas, 2003. Four generations in this room. I feel the ghosts. Today this feels more like a tomb.

Connie talks about prayer, its power, even the weimaraners bark up to heaven but secretly I worry that the clouds are too thick for any noise to reach it.

By Oliver Meek, first year undergrad at UVAAuthor’s Note: “I dedicate this poem to the community of Point Pleasant, West Virginia. They will always hold a special place in my heart.”

Artist’s Note: “Some thoughts stay merely as thoughts, especially those that may cause pain or destruction. You may wonder what could result from your intrusive thoughts—perhaps a bus crash.”

River Mouth

A sister’s duty is harvest, to gather her hair in my hands, finer than mine, like ink on water. A sister’s duty is to be the boatman, so I steer the wooden comb down past the knots and split ends, a tangled watershed flowing far east and due west. Today she wants a waterfall, so I braid her a waterfall—I split the river, one stream into three. I twist every eddy into place and collect all the far-flung creeks. I tie the lace, I tell her you’re lovely, whisper it into the froth and hope she hears it, I watch her leave, river rushing to all the brighter places she has to be, current too strong for the soft words I can’t quite bring myself to speak. So I hold my breath. This too, a sister’s duty— to swim, lungs full. Hands empty.

Alyssa Zhang, first year undergraduate at UVA

Author’s Note: “This poem is dedicated to my sister, who will never let me hear the end of it once she finds out.”

My Turn

When is it my turn?

I don’t know how to touch her. How am I supposed to touch her? Can she please tell me how I am supposed to react to her touch? Please? She touches me like she wants everything to touch, like it is just the two of us. She touches me like I am her girlfriend. She touches me like I am hers, which isn’t entirely untrue.

When is it my turn?

“Mom. I’m scared.”

Putting a tampon into a vagina is no easy feat at eleven years old. This foreign object. Do people really do this all the time? Are people walking around with this cotton swab up their body every day and I just never knew?

“I don’t think I can do it,” I call from behind the bathroom door. The applicator stares back at me. That is NOT going inside me.

“Sweetie, it’ll be okay! It doesn’t hurt!”

“IT DOES,” I cry, shoving things in places where they don’t belong. But there’s blood everywhere, and blood rims my nails in a way that makes me believe I will never be clean again.

When is it my turn?

I just need an instruction manual, and then I will be okay. Maybe I can write a computer science command, some kind of if (blank), then _. I want her to be something I can quantify, something that I can. I don’t know. Decipher? If (straight), then (don’t touch). Or if (questioning) then (tread careful). Can I unfold a meandering piece of paper full of meaningless information that tells me how to read her? Place hand on shoulder. Take hand away. Tuck hair behind ear. No, your hair. Not hers. If all else fails, just walk away.

When is it my turn?

“Sweetie…”The woman at the local bra store looks at me, as I’m covering my bare chest with a cloth.

“You’re a DD.”

Isn’t a double D really big boobs? My friends told me when they got their first bra they were a B. Or a C. Do I win because I have a DD, or is this a failing grade? I remember in the movies everyone always talks about how they wish they had DD boobs, so maybe that means this is a

good thing.

But I also remember that one Judy Blume book. Blubber. They make fun of the girl in 4th grade who has to wear a real, underwire bra. Am I that girl? I feel like no one can notice. How can you notice something that is underneath everything else?

I decide to try on the bra that she gives me, not sure exactly how it will fit. As soon as I put it on, I feel instant relief. The literal weight on my chest is lifted.

Fuck.

When is it my turn?

I do not know where friendship ends and love begins. Are the two of us having a movie night because we are friends? Why is she sitting so close to me, underneath this shared blanket? Do girls just like to snuggle with each other? When she falls asleep, she is breathing into my ear. Her breath tickles me, it being warm and constant. Her lips are at my ear lobe, touching, but barely. I’m transported to watching TV shows where girls would bite a guy’s ear, and it being a scandal. I always thought it was really gross, but now I just want her to do it to me.

When is it my turn?

“Why are we going to their house? I don’t think they actually want us there?” I call out to my friends as they bike ahead of me. We knew that the boys of our friend group were all hanging out because one of the moms told us. As soon as my friends found out, they immediately started biking over to them

“Come onnn, Bella. Let’s just go.”

If boys can just hang out within themselves, why can’t we do the same? Why do we have to chase them? I don’t want people who don’t want me.

When is it my turn?

I want someone who doesn’t want me. Or maybe they do. I am not entirely sure.

When is it my turn?

My mom cries when she asks me if it’s okay to divorce my dad. The weather outside churns wind and breathes rain. I feel like to be a woman is to ask permission for your happiness.

When is it my turn?

Whenever she’s drunk, she wants me. Are drunk words actually sober thoughts? Or do they just make you want to try things that you can ignore when you’re sober? We can sleep in the same bed and it can be less intimate than her looking at me and telling me I am pretty.

When is it my turn?

Someone’s girlfriend comes into our class and gives a presentation in order to help their boyfriend. I stare at the two of them– him falling more in love, and her already in so much love that she is willing to come into our class and give a presentation to help his grade.

I want a slow love, one that puddles into my heart like the drip of a leaky sink. A careful pour of water into a bucket. I want that heart swallowing feeling that is too large, like swallowing chalk because it is so extremely difficult to push down.

When is it my turn? I am not sure. My turn for love, my turn to be a woman? I fear that my turn has already passed.

Arianna Jobst, 3rd year at UVAAuthor’s Note: “This story is a shout out to my roommate, because if it wasn’t for us constantly saying “When is it My Turn?” after watching the most garbage rom coms, I wouldn’t have the inspiration for this piece.”

Bonsai Tree With A Single Apple

Circles— they’re all I see Circles clinging to branches of sunlight

Camera’s vision: aperture diminishes

I never take enough pictures

Never mind the negatives I’m left with Orange sky sans sunset

A green apple, clasped tightly in hand

And leaves stained red

By light bleeding

Circles splitting like everything

Like lives and overripe decisions

Forming into hearts in corners

Of playing cards boomeranging

Slicing fresh fruit and fingers

No Jack ever double-bluffed

Me out to pasture, picking apples

Circles falling from the sky

Freezing into geometric proofs

Spelling out my mixed signal sorrow

With the letters you sent me

From your home-away typewriter

I never felt so small

How can a bonsai grow an apple?

‘How does Atlas hold the world?’

I couldn’t answer you because My head was in the wisping clouds

Looking down on planets

Seeing only Circles

And while you said goodbye

Told me all the ways you’d keep me

I just stared at

A single keyboard key

Blooming into an apple

Bending a tiny tree under its weight

Under the weight of what I can no longer hold

Reece Steidle, First Year Undergraduate at University of RichmondAuthor’s Note: “Technically, “wisping” is not in the dictionary but Shakespeare invented words too, so take thst autocreect.”

Stop, Go Slow

Note to readers: This piece contains sensitive content regarding a road accident. Please be advised.

A single light bulb buzzed, violently, overhead me like a swarm of angry wasps. I wished the light wasps would sting me and put me to sleep. Endless drones of cars passed by and the chatter of people below overwhelmed me every hour of the day. No matter how I tried, the noise never quieted. There was always something to be done. Corpocracy clockwork. It wasn’t just the early mornings or the long hours, though those are bad enough - it was something more draining and exhaustive than that. It was the sense of crushing despair that haunted me. Depressive rain clouds I felt settle over me far too often when I appeared in the drab, black-walled office building. Pushing ahead into nothingness. Trudging along like a mindless soldier completing the tasks I did every day. The same tasks I had done every day for as long as I could remember. Completely alone, except for my one companion, Mr. Clock. Oh, how that clock ticked and tocked. Behind me every second, every minute, every hour of every horrifically similar day. Tick. Tock. Mr. Clock.

The keyboard lit up as I pushed down its keys. Colors flashed before me. Red. Yellow. Green. I glanced down at the intersection below me. Cars go flying by. Another button to press. Red this time. I imagine a world where I am a keyboard. I would not have to do much of anything, I suppose. Just sit there and be pushed. I would not mind. A nice life it would be. Instead, I am trapped. Shackled. In this dark and sometimes damp shell of a building. Involuntarily chained and forced to listen to the droning of cars. Aimlessly I sit. A day goes by, and then another. I feel I am nothing to the world, and it is nothing to me. I don’t remember how I got here, but I know what I’m doing. I know who I serve. I understand. I Stop, I go. There is nothing else. Corpocracy my cell and servitude my jailor.

Mr. Clock is behind me and I hear him whisper his tick and his tocks. I could not help but think he was mocking me with that unending noise. I tried not to listen, to block him out, but Mr. Clock was stuck in his own endless cycle. His hands moved in circles and his face was always plain. Forced to enunciate each second of his cycle in desperate pleas, monotonous cries. Tick. Tock. Poor clock.

The people outside I did envy. They made me jealous and bitter beyond belief. Outside my tiny yellow window, one of three, I watched them as they went by. I saw the same people and sometimes new faces. I always loved new faces. I looked down and wondered where they were off to. Maybe a wrong turn? Or that new restaurant that opened down the street? Maybe to see a relative just down the road? Maybe they’re just exploring the neighborhood. What freedom they have with their feets and their hands. Opportunity enveloped them and Fortune befriended them as she smiled upon their unknowing faces. Fortune never was my friend, but I had Mr. Clock. I gave names to all the faces I saw if I saw them often. I picked favorites but made enemies too.

Tom dressed sharply each day. Off to his own office, I assumed. I saw him almost every day in similar suits. He had a smooth voice, probably. He walked slowly, enjoying the day; even when it had been raining outside. Sometimes he had a walking partner, different each time. I watched, jealously, as they laughed. I liked Tom because he always smiled at me. If he actually saw me through my foggy little colored windows, I didn’t know, but it made me feel good so I pretended he could. Tom appreciated me, and I had always liked that about Tom.

Then there was Gretchen. I named her that because it sounded like a witch’s name. I did not know much about witches. Only what I had seen in passing bus ads or temporary bench posts. They always looked ugly and cruel, and that is what Gretchen was. She never looked happy to see me and often passed by with no acknowledgment. I didn’t like that. She would speed by me each morning and each night. She lived close to my office because I saw her regularly each day. She seemed sad, but I did not understand. How she could be so sad with all the freedom she had? She was free. She could go wherever she wanted, whenever she wanted. She never knew how much she had.

Lastly, there was Nora. I never minded Nora much. I honestly never noticed her. She seemed quiet, and she kept to herself. Occasionally, I would see her walk or drive by with a friend and sometimes her dog. I named her dog Target. Once, a large truck drove by with a dog on it. Next to the dog were the big bolded letters TARGET. I liked the name well enough. Nora and Target would not walk by every day. I would see her most often on sunny days, taking Target on longer walks on the nicer days. I never thought much of little Nora. Too consumed in my hatred for Gretchen or love of Tom to notice little Nora.

Now Nora’s name numbs my ears.

Poor Nora.

Poor Nora.

Tick. Tock.

It was too late.

Poor Nora.

Crushed by a semi.

Poor Nora.

She was going to be okay. She would pop right up, like a daisy. Then I saw her flattened body lying there. Still, unmoving. There’s screaming in the distance. It grew louder and louder until I felt the voice of the scream right below me. A truck? A hot truck with fiery red lights that poured into my sockets and made me feel warm. More screaming, more trucks, more cars. Nora’s body, covered by a white sheet. Minutes ago I watched her walk down the street, and now I watched her body as it was carried away. Her body seemed empty, like without a soul. Had her soul been extinguished? How could life be taken so quickly? How could life be taken?

I should have been focusing on what I was doing. I just wanted to take one small break. I never took breaks, I always did what I was supposed to. Every time. Not this time. God.

I’m so sorry Nora. Poor Nora. Tick. Tock

I spiraled. Pools inside of me like it had rained and I was a trash can left out uncovered, filling fast, about to spill over. The water couldn’t be drained, but I didn’t want it to be. My thoughts consumed me. I tried to press on, but each press on my keyboard put nasty knots in my stomach. Burnt rubber stung my nostrils and I felt queasy, and violent too. Mr. Clock whispered behind me every second, but I only felt it loud, like thunder as it pounded, pounded, inside my head. I thought only of little Nora. Of her accidental escape from this life. I thought of poor Target. I thought of her empty shell of a body. I thought of it as it was wheeled away in the screaming white truck. I could not stop. I thought of jumping. Jumping out of one of my little colored windows. I deserved to feel what Nora felt. Which window would I choose? Maybe the tallest one, the red one.

I’m sorry Nora.

The windows themselves had no locks, no handles. They were small, circular like a trio of eyes, and I often found them to be quite foggy. Each one was tinted with a different color, red, yellow, and green. I was not sure if I would be able to break one let alone fit through it to escape. I wondered

if I was low enough to the ground to jump and survive, but I was more than content to reach the same fate as Nora. I knew I could not and would not carry on in the way that I was. I had to try something. I needed to feel the warmth of something other than my screen or that beady bulb that glared down on me in the day and looked softly at me in the night. I wanted to feel the sun on my face or nothing at all. I got up and walked inanimately towards the middle window. It glowed yellow in front of me. My thoughts bubbled over, spilled over, like water in that trashcan, and I felt my fist slam into the yellow glass. Everything was dark. Tick. To-. Everything went black. Everything was silent. No more droning of cars or angry wasps buzzing overhead. No light from the lonely bulb that hung over me, and no clock whispering behind me. Was this it? Is it all over? Am I still alive?

I sat for a second, and then a few minutes, and then hours. I could tell little about the exact time without my Mr. Clock. I tried to move, but I was stuck and could no longer feel my body. And so I sat.

A single light bulb buzzed, violently, overhead like a swarm of angry wasps. I wished the light wasps would sting me and put me to sleep.

Wait.

This is familiar. This has happened before. I look down and see my key board waiting for me on my all-too-familiar desk. Did I never leave? Mr. Clock’s whispers fill my head once more. Tick. Tock. He says, and so my brain tells me to move my hand to push one of my keys. But where are my hands? Had they gone out to dance? I glanced up for confirmation and I see my little windows. Thank god. Confident with the windows as reassurance, I glance back down, only now my keyboard is missing. Odd. I turn behind me in hopes of seeing Mr. Clock, but he was gone too. Tick. Tock. I still hear him. Inside me? Mr. Clock? I called, but I know nothing has come out because I have no mouth. How did I talk before? Stop. Have I ever talked before? I never had anyone to talk to, only my keyboard to press, but now there is no keyboard. Was there ever a keyboard? Where would it have sat since there is no desk for it to have been placed on? Go. I get up to look out my little windows to search for Tom or even Gretchen, but I am frozen. I don’t have legs. Where are my legs? Yet, I can see out of my windows perfectly fine. I look up in a last resort, hoping to see that familiar glowing bulb. Slow.

As I strain my eyes upward, I feel blinded by an extremely hot circle in the sky. The sun? What am I? Stop. Go. Slow.

Emily Rooksby, Senior at the University of Mary WashingtonAuthor’s Note: “For all the stoplights out there, I see you and appreciate you”

Artist’s Note: “What is beauty but the man-made lights outside of your apartment?”

Shousang

There are no words spoken at Xu Chenhua’s burial—only the wind, its incessant cry carrying the earthy scent of incense through the cemetery. It takes fifteen minutes to seal a burial vault, lower it into its grave & fill it with fresh soil. We weren’t obligated to stay, the funeral director had insisted. Watching a loved one being laid to rest is difficult. I couldn’t bear the guilt of walking away—not after failing to care for her.

The few acquaintances who’d shown up nodded understandingly; offered their sincerest condolences & Chenhua was so lovely, you cared for her well, & would I be joining them for tea later?

I shake my head. When I was seven & foolish I promised A-hua I’d never leave her, so I stay, watching motes of soil strike A-hua’s casket like a muffled waterfall. I drop to my knees & kowtow.

A-hua, can you see? my hands scream into the dirt. I couldn’t protect you, but I’m here now. I’m not going anywhere. I promised I wouldn’t.

I don’t move for the rest of the afternoon, only standing up to brush the soil from my palms & linens at the staff’s urging.

“Sir, night is falling. If you stay any longer, you’ll disturb the spirits of the deceased,” the groundskeeper says in gentle Mandarin. Your…”

“Mei mei.” I manage.

“You’re older, & you’re kowtowing to your younger—never mind. The grave has nowhere to go. It’s only the first day of mourning, right? There are still forty-eight more.”

Gege, listen. After I die—

You’re not dying, I had snarled. Don’t say that.

Hao-gege. We both know that’s not true, A-hua said sadly, & the exhaustion in her tone made me guilty for losing my temper. Just—when I’m gone, how will you bear it?

“I’ll be back,” I mumble, but the groundskeeper has already moved on. It’s only when I’m walking away that I notice the man who’d been standing beside me in tailored Armani.

“Zhiyong—er, xiansheng, night is falling,” they’re telling him. Distantly, I hear crickets singing. “You can pay your respects tomorrow.”

A-hua’s grave & a few others are tucked beneath the shade of an old pine tree, somewhat isolated in a back corner of the cemetery. It’s a less desirable location since it’s farther from the front entrance, but I couldn’t afford better & A-hua refused anything more lavish.

As long as you can hear the trees when you visit me. They overhear so many sad,

beautiful things in a cemetery, you know. But we never listen back.

The Armani-wearing man from yesterday—Zhiyong, I recall—is standing at a grave beside A-hua’s when I arrive the following afternoon. He can’t be older than thirty, but his angular features are set in a deep scowl that ages him by twenty years amidst the chrysanthemum bouquets, joss paper & candles. I follow his gaze to a grave, bare except for a name—A-ling—with no offerings save for a half-crushed cigarette.

Briefly, I wonder what could’ve passed between them. But the thought feels too intrusive, so I kneel in front of A-hua’s grave & let my memories wash over me like waves.

At some point, Zhiyong leaves. I continue my vigil until I hear the groundskeeper’s soft greeting while the sun makes way for the moon.

—

He’s at A-ling’s grave the next morning. Again, we pay our respects in silence. — Over the next three weeks, Zhiyong & his Armani wardrobe become as much of a fixture at the cemetery as the pine trees’ chorus.

“Don’t you have anywhere better to be,” Zhiyong asks gruffly.

“Not particularly,” I reply. I don’t tell him I don’t know how else to spend my forty-nine days of mourning. Zhiyong considers this, then nods, seeming satisfied with my answer. We stand beside each other, silent until the groundskeeper arrives at closing time.

—

Imagine this:

You’re born an only child. When you’re seven, your parents introduce you to your sickly younger sister, who you adore immediately. Later, your parents tire of helping another body, so the caring—the loving falls to you. When you & your sister are old enough, you leave.

By the time you’re twenty-five, your sister is dead. In your lifetime you’ve managed to be someone’s older brother & a sibling to no one at all.

On the forty-eighth day, Zhiyong tells me about his turbulent relationship with Líng—how they hated each other, loved each other, how they hurt each other because they loved each other so much. While walking home, I think about how Zhiyong couldn’t hide his lingering fondness for foolish A-ling & their youth, nor his bitterness at how everything fell apart.

—

“Were you & Xu Chenhua close,” Zhiyong asks me the next day.

“We immigrated from Hunan five years ago. Our parents…” Didn’t consider her their kid, I wanted to say, but another burden. Regretted adopting her. “She was only seventeen.”

“You’re not afraid of disturbing her spirit by visiting every day?”

“Somebody has to remember,” I protest. “I promised—” “That you wouldn’t leave? Or that you wouldn’t move on?”

“Why do you care so much?” I ask, ashamed at how the words tremble. “I can’t be angry like you are at your A-ling. It’d be unfair.”

“So? It’s your grief. Feel whatever you want.” Zhiyong shrugs. “There’s no good or right way to do it. I just can’t tell if kowtowing has helped you actually accept her death after forty-nine days, or if you’ve just been feeling sorry for yourself this whole time.”

I can’t be angry, not at A-hua. But Zhiyong’s words seep into me like dirt under my fingernails, & I realize whatever ugly, metallic emotion I could wrestle out of my grief—whatever bitterness I held before these forty-nine days of mourning towards our parents, not-quite friends, doctors who wouldn’t listen—there was only the way I did it.

A-hua—my younger sister—is dead.

“She was only seventeen,” I repeat eventually. A ragged gasp escapes my throat, & I finally begin to cry.

By Sophie Uy, 4th year undergraduate student at James Madison UniversityAuthor’s Note: “This flash fiction piece was written as a meditation on grief: A powerful, universal, yet unique thing that those closest to your heart as well as strangers can share & understand.”

once more the rain, with a song

all day he slept and he woke and he slept and he woke and sometimes still he woke to the funeral home of his boyhood: the frenzied press of the gun to his palm the threat of its intrusion upon his mouth, his gut. and he slept dreaming of

the last summer, the one that came and stayed while ant hills caught fire around him, the ants scorching to their deaths scurrying desperate for someone to come end it all. he was watching the trees waiting for the frogs, the croaking of the daarvag. what was to come after their cry, he couldn’t quite recall.

Pari Sabti, 4th year BFA student at George Mason University

Author’s Note: “Daarvags are a type of tree frog found in the north of Iran. They’re said to signal oncoming rain.”

The Korean Label

I come alone in big city going Baltimore from Seoul down away South bring children education no good but is what is learn without America book: You understand?

Walking down dyed path smell of dampness the earth wet and hot for autumn footsteps echoing through misty air behind me coming the dull thud of my—full white or dotted? Which way to Vienna? Turn right at the fork in one hundred feet. Signal: click-tick, click tick.

A horn blared behind me. A large truck darted in front of me. I pulled my foot off the accelerator. The driver must have had his window open because I heard someone shout, “Stay in your lane!” I began feverishly checking my mirrors as I merged onto the exit.

The light threw a red smear on the wet asphalt as I waited at the intersection. It’d been a long time since I’d come out this way. Almost fifteen years ago, was it? I couldn’t remember much of it anyway, except for bits and pieces. I was only six at the time.

The only things from that time of childhood that stick out to me were the vacations we’d take at the beach. That and the dentist. I never liked going to the dentist. I was always uncomfortable—maybe it was the chairs. Like car seats but worse. And then, there were the dentists’ assistants. They were always nervous about something, so they were always talking.

“Hi! How’re you?” she asked me.

“Fine,” I answered.

“Good, good, well let me see here. Open for me. Wider. A little wider. Bit more. There: hold it like that.”

I stared upwards blankly at the light fixtures. They hummed dimly, like angry mosquitoes. The light was cool, white, and blinding on my face; but I tried to ignore it as best I could. The ceiling was made up of individual white squares. One, two, three, four, five—

“What are you anyway?” she asked, holding some dental instrument over my head. “Native American or something?”

“No, Korean.”

“Really? Both parents?” she set something down on the tray nearby.

“No, just my father.”

“North or South?” I didn’t know what she wanted to hear, so I guessed.

“South?” I answered tentatively. She nodded approvingly.

“And your mother?”

“Hispanic.”

“Wow,” she said, reaching for some other tool and beginning again. “That explains why I couldn’t tell. Actually, back when I was in college, there was a group of students I knew through my friends. And I couldn’t tell what they were, because they had a darkness to them but also looked more Caucasian. Come to find out they were actually Irish and Italian.”

“That’s a very interesting combination,” I said politely, opening my mouth wide once more.

“It is interesting, isn’t it?” she said thoughtfully, forcing a cool, metal instrument into the corner of my mouth. “But, you’ve got even more diversity in your family. I bet people get confused a lot.” She began pulling off her gloves: they were smooth and white. “I get it: I’m something of a mutt myself. Oh, Doctor, could you come here a second? I think he’s ready for a treatment with the—”

I pulled into the parking lot in front of the entrance to the garden, my hands resting on the wheel. The rain was letting up a little bit, but a cloudy mist still hung on the sky. I listened to the sound of the rain pattering down on the windshield.

I was pretty sure I had signaled. It wasn’t some kind of last minute thing: he should have seen it coming. My seatbelt hissed as it flung itself backward. Besides, what business did he have to shout at me like that. “Eight dollars,” said the woman at the check-in. I took a five and three ones out of my wallet, handing them across the counter. I always remembered it being free admittance to the public. Maybe it was because I was younger.

Stepping out of the visitor center, the air fell on me, thick with water. Each breath caught thickly with the smell of damp earth. Everything seemed to drip with moisture. The rain had dyed the path with a dull gray, and dew clung to the grass. Mist gathered along the horizons, blurring the forms of pines into outlines. Gray veiled the sky and clung to the park, threatening and ominous. I stirred my shoe in a puddle and glanced behind me

Hobbling down the path towards me, arms firmly folded behind his back, was my grandfather.

Wisps of hair clung to the sides of his otherwise bald head. His face was collected in a near perpetual frown, and his features were gnarled like old tree bark. His eyes were failing him. Whenever he looked at something, he would lean forward slightly and furrow his brow. Despite the oppressive heat, he was bundled up to his neck in a long, dull sweater and a green-black scarf. A conspicuous white tag written in Korean clung to the scarf’s pattern.

“What’re you doing? Why’d you pull the tag off?” my mother said. She wasn’t angry, just exasperated. “We need that to pay—honey, go put that back where you found it. Hurry.” I wriggled through the line of carts, mumbling excuses as I had been taught. I trotted down the aisles, past a colorful array of dried pastes and spices whose names were written in a language I couldn’t understand. The smell of rotted fish drifted over from the seafood section.

The older women stared at me over their cat-eye glasses, muttering in a language I could not understand. They laughed and tittered as I tried to figure out which bag of onions weren’t rotten. I ran all the back to the kiosk, my shoes squeaking merrily on the polished floor.

My mother was paying. Her hair was long and curly then and stood on end no matter what she did. In the harsh store light, it glowed a reddish-brown color: the light gathering in it. As fast as I could, I squirmed through the line. “These, too!” I said, tossing the onions onto the belt.

After we had finished paying, I began packing the groceries into the bags. Carefully, I stacked the eggs on the rice and then the onions on the eggs. The clerk smiled while my mother fished the eggs out from the bottom of the bag. I glanced back at the queue that had formed behind us. The two women from before were there. They stared at my mother over their cat-eye glasses and muttered as they checked out behind us.

It was raining when we left the store. The red of the storefront mixed on the surface of the wet asphalt. I was so busy trying not to step on cracks on the sidewalk that I didn’t notice the glasses women talking to my mother.

“Pretty girl,” I heard one say in clipped, heavily accented English. “Korean?” the other asked.

“Yes,” my mother replied smiling, holding my hand.

“You take care?” one of them asked. I sat down by the cart to look at the red reflection in a nearby puddle, pulling my mother off-kilter.

“Oh, yes, all the time,” my mother said, regaining her balance.

“For how much?” I held my hand just above the puddle. I could almost feel the puddle.

“Excuse me?” She tightened her hand on mine. I tried to pull away, but she wouldn’t let me.

“How much you paid to take care of her?” I managed to twist my hand out. My fell into the puddle, sending ripples through the red of the H.

He could barely walk anymore—it was more of a hobble than anything. Sometimes he would stumble, but he always refused any help I would offer him. He kept his arms folded behind him and tottered along, straining his neck to see the edges of the path. Always punctual, he didn’t want to waste any time until got to see the bell. Apparently, it’s the only one of its kind on the East Coast.

Eventually, we came to a squat brick wall with a gate in the center of it. Four black, Korean characters stood in proud relief from orange of the brickwork. Patches of pink spider lilies adorned the path to the gate. Their brilliant color made a vivid contrast to the jet-green grass nearby. Just before the threshold was a bush. On the bush were dainty, pink flowers, pearlescent beads of dew hanging on their tips.

“Know what this?” my grandfather asked in his clipped, heavily accented English. “Korea flower? You don’t know about this? Aren’t you Korean?” I could hear the professor chatting with several students in another, larger group about the assignment.

“I don’t know much about the Fifties, even less Korean history,” I said. “I can’t even speak.”

“But, don’t you—I don’t know—feel like you should go and rediscover your roots,” my other groupmate said. “It could be cool if we did something like that.”

“I’m really more interested in doing something in American history—Civil Rights or something.”

“But isn’t it your heritage?”

In front of me was a row of pine trees. They grew straight out of the ground with their familiar triangular branches. To my right, hunched just behind the gate, was another pine tree. Its trunk bent and writhed strangely. Along the ground, a strange ink-green grass was planted in patches, standing in stark relief to the rest of the green.

With a twitch of his chin, my grandfather continued marching up the path. I let my eyes drift down to the path. Beneath me, the stone path and grass blended seamlessly into one another and seemed to be one continuous surface. I took a deep breath, the air nearly stifling me. A little further down the hill, I noticed another brick wall. I could just barely make out a pond beyond it.

Suddenly, my grandfather halted, and I looked up. We had come to a hill overlooking the garden. The hill sloped gently down to the left, leading to the glassy surface of a nearby lake. Somewhere beneath the water were koi. I remember feeding them bread the last time my grandfather came to visit—when he came to paint the fence?” my mother asked, stopping as she fed my brother. “You want to paint the fence?”

“I do this for you,” he said gesturing wildly. He was younger then, his back straight without the help of his arms—his eyes not yet tired with seeing.

“Why?” my mother asked.

“Stop rot. Keep out other.” My mother tried to talk him out of it—convince him that she’d just pay someone else—but he was adamant. That afternoon my mother went and bought him brushes and sealant.

In front of me towered a large pavilion. It was built without screws, glue, or any other kind of traditional fastener—the whole pavilion. Like a massive jigsaw puzzle—each piece had been hand-carved to fit together in perfect unity. The weight of the materials kept everything in place.

He stayed out there all day painting that fence even though it was in the middle of July.

Underneath the curled eaves of the pavilion hung a massive bell. It floated several inches off the floor, suspended by a massive cable running to a huge pine beam in the roof. A dragon with its claws dug into the metal snarled as it held the bell aloft.

By the time he was done, it was the afternoon and the air shimmered with an orange glow.

The bell was massive. A person standing behind the bell on one side would be invisible from the other. Worked into the surface of the bell’s iron were rocks, water, the sun, pine trees, turtles, deer, cranes, bamboo, and even mushrooms. On opposite sides of one another, written in both Korean and English, were the words “peace and harmony.”

After dinner, he went and swept the stoop, contrary to my mother’s assurances that no one would notice.

My grandfather stood in front of the bell for several minutes, and finally he turned toward me. “This bell important,” he barked at me. “Know what is?” I shook my head. “This bell mean equal. Mean Korean equal with American. Given peace and harmony.”

He sat out there till night fell and the frogs began to call. Overhead, the bats went wheeling about in the sky, chittering loudly at one another.

“Korean War in books?” he asked. I nodded. “I come here,” he said angrily pointing at the ground, “during war. Bring family later. My life difficult. Yours better.”

It took him three more days and several more coats for the fence to be sealed completely. By that time, the wood had turned a sickly olive color.

“American not interested, so Korea not in books. Not good, but is what is. You learn Korea without American book.”

My grandfather left about a week later. He kept talking about that fence for years.

“But Korean in American books will be you. You American. You Korean. You be in books.”

Eventually, though, we had to replace it.

“You have opportunity: you understand?”

So, we tore it all up and built a new one.

Regret to tell you not doing so well nearly full diabetic retinopathy have to move him into a retirement can’t take care of any more will you be able to come to see I understand all that you and your family are going a bowl of rice he’s just not getting any better he sat there at the table filling it up over and over kids, I just want to tell you that your grandpa’s just he liked to us eat the travel ban makes it difficult to fly in for the funeral maybe it made him feel better about never visiting didn’t notice for three days a nurse smelled died alone.

I sat on the cold stone stairs of the pavilion for a long time. The weather had cleared now. Strewn about the pavilion were leaves—their dull browns, brilliant crimsons, and blithe yellows forming a pattern like a rug. They’d stayed dry during the storm. Occasionally, a gust of wind jostled the pattern and sent some leaves scurrying into the garden. I bundled myself further in my green-black scarf. I remember tearing the label off as soon as I got it.

The wind whistled as it passed through the eaves of the pavilion. Eventually, I stood and started walking back down the path. I fingered the patch where the tag used to be and stopped. I held it up to my face to take a better look at it. There was no indication of the tear—not even a trace of the label. Then I remember what I had forgotten: There never was a label.

By Samuel Beckett Kim, second-year at George Mason UniversityAuthor’s Note: “For my grandfather: They endured.”