VLR

VIRGINIA LITERARY REVIEW

Spring 2025 / Volume 47 / Number 2

The Virginia Literary Review

Contact Us!

www.virginialiteraryreview.com

vlreditor@gmail.com

Spring 2025 Staff

Editor-in-Chief

Aoife Arras

Production Manager

Portia Papagni

Marketing Chair

Ebte Abdul-Qudoos

Financial Chair

Isabel O’Connor

Poetry Editors

Khadijah Aslam

Ganeev Kaur

Joshua James Althaus

Sydney McClellan

Jack Martinez

Julia Pieloch

Gabi D’Avanzo

Prose Editors

Chloe Ross

Elizabeth Parsons

Peter McHugh

Stasia Winslow

Miriella Jiffar

Aliza Susatijo

Sophie Hay

Riley MacKenzie

Robbie Brown

Art Editors

Khadijah Aslam

Gabi D’Avanzo

Riley MacKenzie

Robbie Brown

Founded in 1979, The Virginia Literary Review is the oldest undergraduate-run literary magazine at the University of Virginia. The editorial staff considers literary and visual art submissions from students across colleges and universities in the Commonwealth of Virginia during the first three-quarters of each term. The VLR is published twice a year in the fall and spring. For more information and to view past issues, please visit our website.

As of Spring 2025, the Virginia Literary Review is formally a Contracted Independent Organization (CIO) at the University of Virginia. The magazine is not, however, affiliated with the University or any of its departments, and is completely liable for itself, its members, and its activities.

Copyright 2025. No material may be recorded or quoted, other than for review purposes, without the permission of the artists, to whom all rights revert after the first serial publication.

Many thanks to UVA Arts & the Office of the Provost & the Vice Provost for the Arts for their financial support.

Contents / Spring 2025

Poetry

10 / A History of Cuban Poets

13 / Minnow Hunting at Napeague Point

22 / The Ringmaster’s Quiet

24 / Ballad for a FedEx Driver one

Tuesday Half-Past Noon

26 / Halloween, Two Years after My Grandmother Died and Avoided Any Diagnosis at All

34 / Raid

43 / Resurrectionist

Prose

6 / I Confess

15 / Disrememberment

18 / Devil’s Food Cake

28 / It Passes Me By

30 / I know your image of me is what I hope to be.

37 / Madeline

40 / Transform

Visual Art

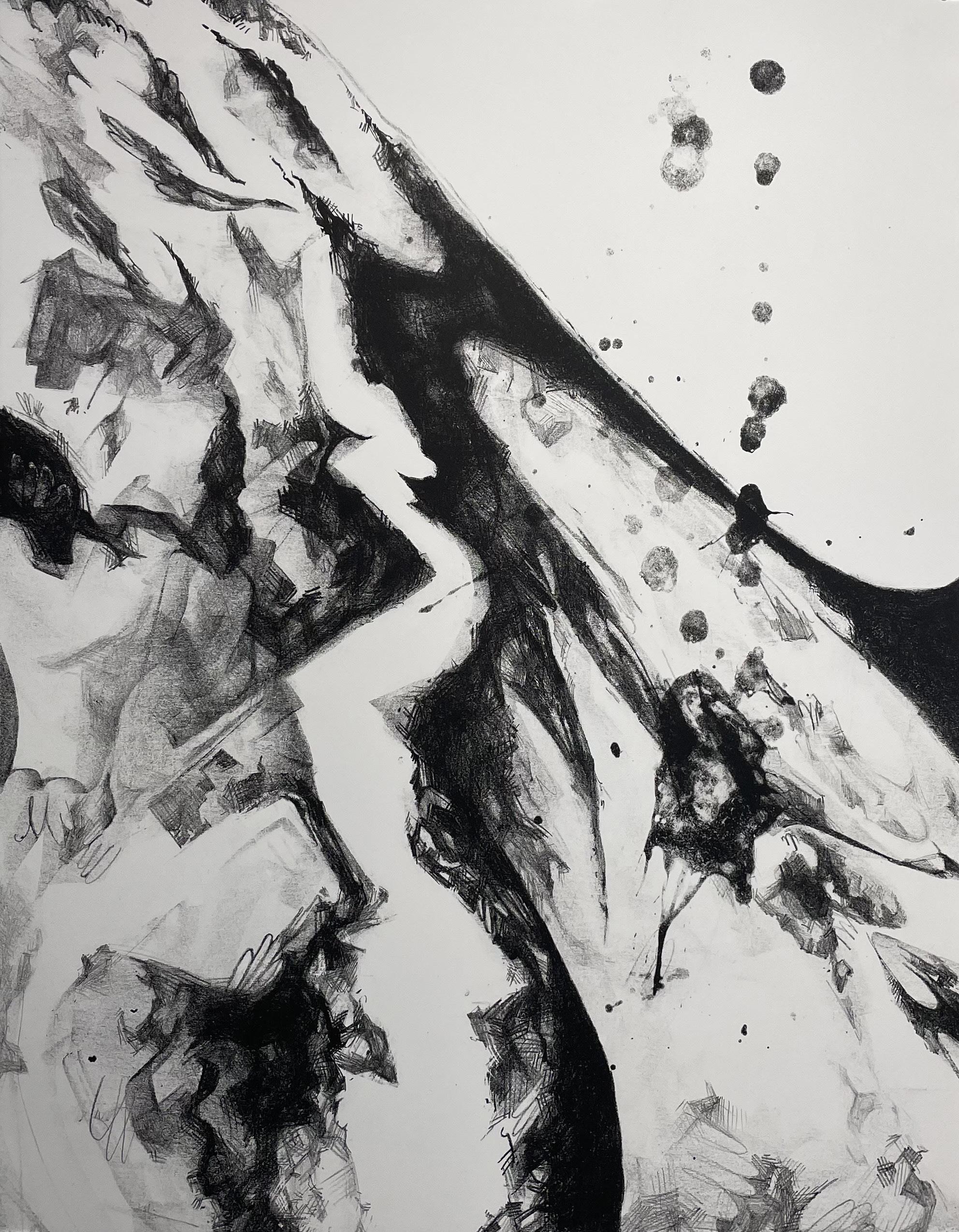

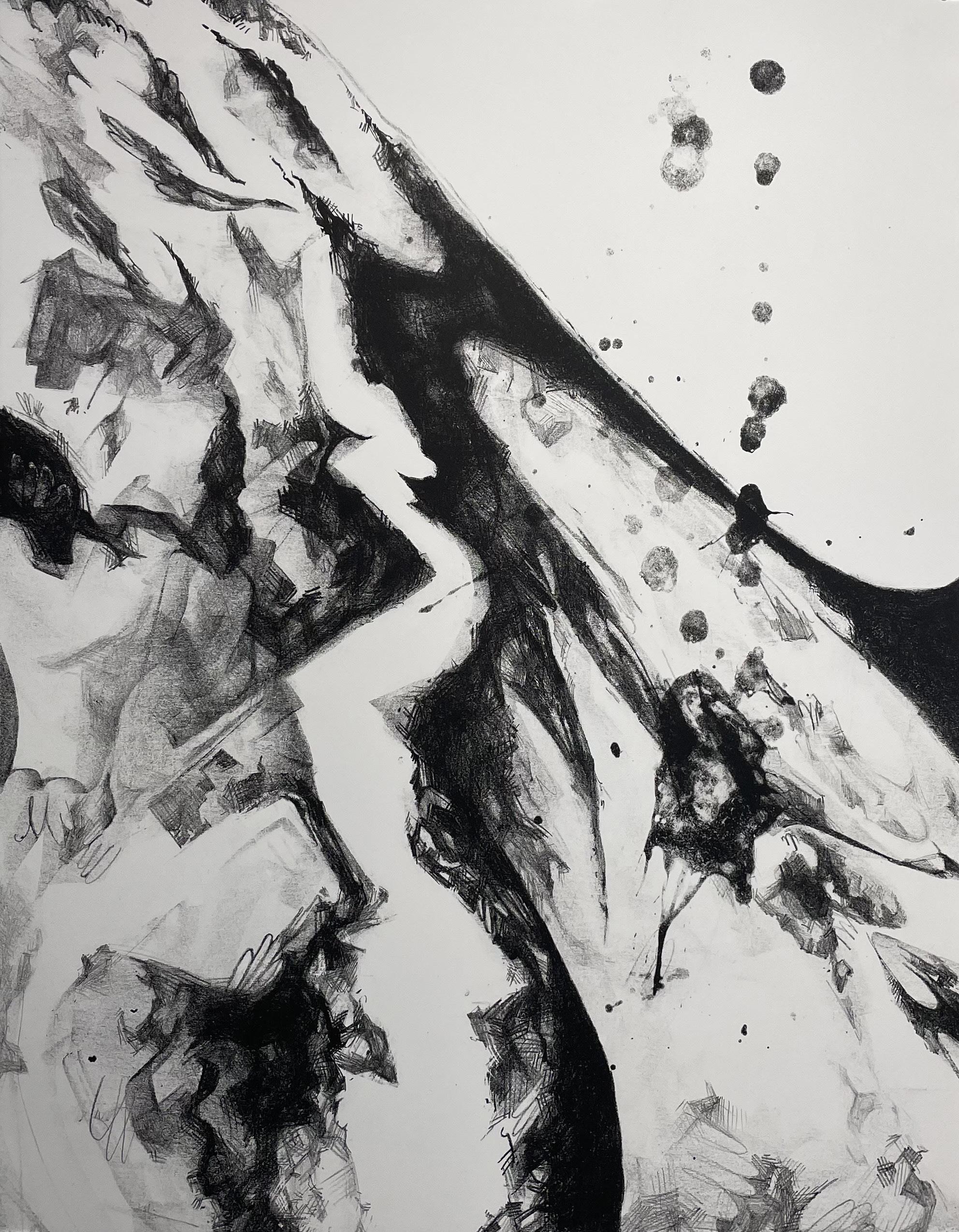

Cover / Spit Scape

12 / God Helps Those Who Help Themselves

17 / Blue Punk Teeth

23 / To Serve Man

25 / Untitled Red

29 / Spring Without Summer

36 / Hands of Desire

42 / Winter Parkway Botetourt

Elizabeth Mirabal (she/her)

Haylee Ressa (she/her)

Kate Killen (she/her)

Sterling Peterson (he/they)

Grace Whitaker (she/her)

Bella LoBue (she/her)

Grace Sawyer (she/her)

Miriella Jiffar* (she/her)

Emily Rose Allen (she/her)

Andrew Zhou (he/him)

Cristina Rodriguez Velez (she/her)

Chloe Cella (she/her)

Peter McHugh* (he/him)

Eli Hiscott (they/he)

Luke Logan (he/him)

Logan Singo (he/they)

Anthony del Grosso (he/him)

Jasmin Dockery (she/her)

Madison Hinton (she/they)

Elisa Slater (she/her)

Luke Logan (he/him)

David Bryant (he/him)

*Our evaluation process is anonymous to ensure equality between all applicants.

I Confess

I confess

When you read stories of prophets, priests and kings, the long-lived dust swirls amongst yellowed pages and makes you sneeze. You thumb through books of saints’ lives, wishing for the divine to also find favor with you, to call you by name. You listen to the scriptures, wishing for miracles to be performed from your praying hands, clasped the way your mother taught you.

I confess

You believe you are destined to behold the face of God, the shroud lifted from your face by his hand, your theophany fulfilled. You believe you can swear a new covenant with your right hand. Instead of burying yourself in the cleft of the rock, you will look your creator in the eye and bathe in light. For who has seen God face to face and lived?

I confess

You are afraid of the shadows, those ghosts of your former selves who remain there. The church of your youth is empty and quiet, but you manage to make out her form, still a child crouching in the crypt.

She’s seven, lost in the folds of somber velvet curtains, perched on the seat in a paneled confessional, puzzled about how to admit her sins. She feels something mortal and grave coiling around her heart.

She’s eight, kneeling in the pews and admitting to God that the holy host is dry on her tongue. Also, she needs a good score on her math test, please.

Elastic youth slips into the molting of puberty. Time stretches on, and she does too.

She’s thirteen, itching a forehead glistening with consecrated chrism. In class, they tell her this oil was made from myrrh, the very same myrrh presented to the Christ Child upon his birth. Newly anointed, she dares to fashion herself anew, to reach for revelation. Here I am, Lord. A green shoot growing from the stump of Jesse.

I confess

Your stomach churns all throughout lunch, as you half listen to your friends and

barely touch your plate. Fourteen years old and worrying about the state of your soul. You know your class is scheduled for confession today. And you keep obsessing over what you might say.

You watch as your friends pick lettuce out of their sandwiches, unbothered. Didn’t they know that the molten core of their hearts will be judged and placed on the scale against the feather of truth this afternoon? Yet, here they are, clandestinely whispering names of the eighth-grade boys they want to kiss. You banish these thoughts to a faraway corner of your mind and join in.

I confess

That when you go to confession after lunch, you lie to the priest.

We didn’t go to church on Sunday, you say. That part was true. Why, he asks. My mom was busy, you say. That was partly true. The priest gives you a routine absolution and lets you go.

PAUSE—was that a hint of reluctance in his blessing? Doubt gnaws. PLAY—you close the door softly and mutter a prayer in the hallway.

I confess

You don’t tell him you missed church last Sunday because you were traveling. You don’t tell him that you’ve been out of school for the past three weeks. You don’t tell him you went to Ethiopia for a funeral. You don’t tell him it was the first time you saw your mother cry and cry and cry and cry.

The day before you left, your mother showed you pictures of the time her brother visited D.C. for her wedding. You never knew your Uncle David, so on the flight to Addis you look at the clouds and pretend he’s still alive.

Your mother doesn’t let you come to the burial, so you wait in the car. The windows are rolled down and humid air seeps into the seat peppered with small holes. In the heat and the haze, Uncle David’s blue wedding suit returns to you. He has a white calla lily pinned to his left lapel, as if it was plucked from the bouquet of lilies your mother holds in the photo. He smiles as if he has just done it himself.

Before she leaves, your mother asks a woman named Hewan to watch you in the car. You know enough about Ge’ez to understand that Hewan means life, and you almost

laugh at the irony.

Your mother didn’t have to take you to Ethiopia with her. It would make her parents happy, everyone said. So she did. You are finally going to visit the country that slumbers in her memories and comes alive in your imagination. Write about your trip to remember it later, everyone said. So you do.

Your new journal has owls on the cover. “Tomorrow, I’m flying halfway across the world,” you write. You had just learned about Greek mythology in school. Owls are Athena’s bird, you recall the teacher saying. You hope to be wise like the goddess, to find a way that will bring your grandparents out of a bottomless pit of grief.

But the bridge between languages and generations and oceans had never been built and none of us knew how to cross over.

The day you fly back to the States is a Sunday. The hotel has a balcony overlooking the streets of Addis, and the window is flung open. You can hear the call to prayer and the church bells and the synagogues, a dissonant symphony but comforting all the same. You can hear the city’s heart, your mother’s heart, broken but still beating.

This promised land your mother was cleaved from, this promised land that waits for her children to return. Long long ago, when the city was burning, your mother left and never looked back. If she did, would she have turned into a pillar of salt?

You watch the rising sun bounce off mismatched rooftops, bathing the merchants and children and cars and narrow streets in a golden splendor. Maybe God really is here, you think, and there’s no need to go to church today.

I confess

You are not sure if this memory is wholly true, or if it remains nestled in your mother’s stories of her childhood. Stories of growing up in a country where religion pulses like blood throughout its rugged highlands. Stories of practicing an imported Catholicism but celebrating with the dates of an Orthodox calendar. Stories of walking fifty kilometers in pilgrimage for the feast of Gabriel, to the rock-hewn church where her father prayed for a daughter and not a sixth son. Stories of fasting for Ramadan and Lent, feasting for Eid-al-Fitr and Easter, innocently trading faiths like playing cards with the neighbors next door. Stories of an idyll, a cocoon, a paradise.

I confess

You don’t tell the priest all of this. You sit there, taciturn. How would he possibly understand?

You don’t tell the priest all of this. You imagine yourself clothed in sackcloth on the walk back to homeroom. Isn’t that what the saints do in your books?

You don’t tell the priest all of this. Yes, he says you dishonored your God. But didn’t you find him, too?

Miriella Jiffar

A History of Cuban Poets

I.

Perhaps you’re no longer in that wild Key West grave, because the sea has taken you to the depths where you once dreamt of living.

Perhaps you’ll swim now in the warm currents of the Strait and maybe on your trips see us die: the ignored drownings of those who still attempt a crossing.

Showing off the wavy hair that you cut because you thought it was ruined by the fevers, you shy away from the weight of the tombstone that with grandeur proclaims you “Glory of Cuba.”

You didn’t want, I know, the shine of the relics of la patria, but rather the anonymity of jubilant ones.

Juana, I won’t be lucky enough to escape to the sea in a floating cemetery. My time is not one of marble monuments.

II.

Your first house had a living room, a main room, a dining room, a shed, a backyard, a well.

They say that going there is to receive “a lesson in Cubanness” and that alarms me.

I can’t distinguish you among the ferns nor in the corrosive humidity of the galleries. I don’t see you playing near the solid mahogany desk nor under the Mudejar arch. You don’t look like yourself in oil paintings, charcoals, watercolors. I can’t see your reflection in the opaline pink vase.

We celebrate the architecture and the “creole empire” furniture as if we wanted to exorcise chronic poverty, lost bodies, dead little children.

III.

Now your princely editions are quoted, the balustrades of your windows and the vessel found after archeological digs are valued.

Now your lost letters are searched in antiquarian societies and your young and melodious name is pronounced. Novels are written for you: speculations flourish. We call you.

But we didn’t know to be there earlier, in the dispersion of cold cities in the precariousness of dead children’s houses.

Some prefer to continue embodying the role of

the judges of history and reproach your letters of survival, as if you had to be forgiven, as if we disremembered the ancient rules of dangerous games.

Elizabeth Mirabal

Minnow Hunting at Napeague Point, August 2008

The bluefish come every August maliciously gnawing on our ankles sharpening their teeth on toddlers until bathwater steals the hue of smoldering sunsets

Red sky at night, sailor’s delight Red sky in the morning, sailors take warning

The blue flag alerts of their arrival blackened bare feet on asphalt melting tang of sunscreen and watermelon juice we turn our backs to the ocean face the humdrum stillness of the bayside

Fed up with being the prey we become three-foot-five hunters little kings with big fishermen nets snarling seaweed and crusted barnacles engulf pools of squirming minnows

Puckered lips tickle against thighs turquoise bikini bottoms sag with sand as Catherine teaches us to use our fists grab two at a time in pruned palms silent scales against beating flesh

I bet you didn’t know that the bikini got its name from the Pacific atoll where, four days earlier, the U.S. had exploded another A-bomb?

No one tells us our bikinis are explosive ticking bombs that go off in five, ten years suddenly we are prey again, permanently dodging bulging eyes and piercing teeth powerless where we once ruled

We retreat again, scramble to find a shore where we can still be kings in turquoise bikini bottoms but we walk until the enraged asphalt burns our soles and shamefully sulk under the red sky

Haylee Ressa

Disrememberment

I leave my baby teeth braided into the nylon net that stretches across the bow of the catamaran, where I lay with buttery banana bread crusts in my tiny fists. When I watch the sugar cane burn, black smoke casting my preschool in dusk, I imagine the sun-warmed net pressing against my cheeks.

A hot metal slide stings under my legs, sending me rushing towards roaring waves once my feet hit the sand. I gently slide open my face and remove the nasal cavity, tucking it in the shadowed gap between two concrete tetrapod sea barriers on Haeundae beach.

My left optic nerve stretches around a bird feeder in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, eye attached, my blue-flecked-with-gray meeting the gray-flecked-with-blue of the black-chinned hummingbird. My knees, patterned by the tile I had pressed them into and stained with melted popsicle, drift lazily in a Houston pool, moving only with the waves of someone cannonballing off the diving board. For Virginia, I unfold my chest, a not-quite-yet open-heart surgery, and pry one of my ribs free, burying it in a stream made of rainwater in a buzzing playground. It is the third one down, on the left, and the movement of my fingers finding leverage beneath it leaves my sternum cracked.

Because I am my father’s daughter, I slowly exhale the last lobe in my right lung and press it under the Puff the Magic Dragon CD about to start spinning in our radio. The sound chases me into the cold, where I inflate my two-thirds lung with smog and run my fingertips across snow-covered hydrangeas, bobbing bundles of cotton.

On Yangmingshan, a banana spider’s web shivers from the burst of air as I open my door, longer and wider than I am. I part my hair and split my skull in two, gripping my hypothalamus between two fingers as it squirms, slicker than I expected. I thread it into the web, and the spider bobs its yellow abdomen, allowing me to duck underneath.

Under the shadow of a banyan tree, I cough out my larynx, the pink flesh landing with a dull thunk in my palms, dripping with saliva and blood. I carry it to Haifenglu, where I ease a yellow brick loose with the tip of my Converse. I press it into the sidewalk where sometimes it will sing, the shadows of skyscrapers listening.

I ride the U-Bahn from Dornbusch to Hauptwache, my back pressed against the scratchy polyester seats designed with waterboarded cheetah print. I undo the bottom buttons of my shirt and reach through layers of thick epidermis, gripping the squishy end of my large intestine and looping it around a column in the station. Quickly, I slip between the closing doors of a train going the opposite direction, my intestines unraveling behind me as I journey back.

My right femur lays in peace at the bottom of an alpine lake, its counterpart turning bonemeal, buried under a field of rocks in Maine. My scapula rests steady on the branches of a Southern Oak, gnawed on by gnatcatchers. I leave my hippocampus

on the banks of the English Bay and tuck my spleen between flaky layers of honeyglazed filo. Starting at the helix, I peel off my ears, feeding them gently to the blue tit that sings Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony from the top of a sprawling cypress.

I cannot eat or speak or breathe, but I stretch from Timor Leste to New Market. I cannot clap or knit, but if you find my hand stretching out of a tree’s hollow in the Occoneechee State Park, don’t be afraid to give it an affectionate squeeze.

I climb to the edge of a rocky outcrop, mountains unfolding around me like waves in a deep ocean, tinted with that same atmospheric blue. Trees swallow the mountainside. Ravens dance above me, playing as the wind flings their fragile bodies through the air. A sunset explodes to life on the horizon. There is only one piece of me left. Finally, with my home a smudge of gray in the green valley below, I leave my heart.

Emily Rose Allen

Devil’s Food Cake

She opened her eyes with a start, then slowly closed them. The sun was setting, but slowly as well. Warm orange light worked past the flimsy blinds and lit up the dust drifting in the still air of the bedroom. About an hour or so and the sun would be gone. The day was that much closer to ending. She usually liked to walk at this time. It felt nice to stretch her legs and feel the breeze after a long day of holing up, but today was not that day. She turned from the window and wrapped the blankets tighter around her and her old plushie. The room was stuffy and hot since it faced the sun, but the sweat soaking into the elastic of her clothes barely registered as she held her eyes shut.

She opened her eyes again, and the sun was still out, bathing the room in dim pink hues that seemed to make the walls bleed and her skin feverishly flush. There were only maybe twenty minutes of light left today. Might as well wait it out. She reached over to her nightstand and felt around for the rough cover of a book from her childhood, sticky at a corner where juice had spilled onto it. The ruddy light made it hard to read, but she didn’t mind. As the room grew redder and redder, her stomach burned more and more. She knew there was no use trying to read like this. Sighing, she disentangled herself from the blankets and stood up, her head swimming from the slight movement. She had never been athletic, but this was a new low. She sighed as she rubbed her eyes and padded past her dad’s room. A glance told her his luggage was missing, and the bed was neatly covered with an old sheet. She kept walking. Not even a note this time, and on today of all days too. Well, whatever the reason, the result was the same. She went downstairs to the kitchen.

She averted her gaze as bright white light poured out of the fridge. Adjusting to the cold fluorescents, she carefully dug around the remnants of the week’s takeout. Moldy. The mottled blacks and greens glistened like mucus in the harsh light. Grimacing, she unceremoniously dumped the containers into the bin and considered her options as she washed her hands. There was nothing else in the fridge except an assortment of half-empty condiments and some sad-looking lettuce, and in the pantry, there was nothing except some store-brand toaster strudels she had gotten on sale and ended up hating. Not much to sustain her Olympian physique. Her stomach growled again and threatened to burn a hole through her skin. She went back to the fridge for the takeout menus stuck to it and noticed something poking out from under an old calendar. A picture. She carefully slid it out from underneath the calendar, and smiled warmly as she took it in. It was faded where a corner had been exposed to the sun, but otherwise just as vivid and bright as she remembered, if not more. Suddenly, she knew what she wanted. She wanted cake. Rich chocolate cake covered in so much frosting, only a kid would dare take more than a bite. She had certainly taken more than one bite, and the frosting smeared over her mouth almost hid her huge grin. Her father grinned alongside her as her mother gave a weak smile.

On that day, she was the happiest, sickest girl on the whole planet, and she wouldn’t have changed a single thing. Not the cake, not the little party with dollar store streamers and paper plates, and not the people who were there. She should’ve wished for that when she blew out the candles. Hm. Maybe some fresh air would do her good after all.

She knew no one cared, but it still took longer than it should’ve to find clothes that she felt ok with. It took ages to flatten her cowlicked hair into something vaguely presentable, and longer still to even find her wallet. She had forgotten where it was, but even so that didn’t quite explain how much time she was wasting. She got to the front door and checked her pockets one more time. She had everything, now she just had to go. She reached for the handle with a shaking hand, and a heart beating like she was a coked-up rabbit. Her hand was on the handle, and instead of shaking, now it wouldn’t move. Was she going to go out for the first time in…a while…just for some cake? She dug her nails into the palm of her other hand and almost threw herself out the door.

Her stalling meant that the day had now well and truly ended, and no one was outside except for her and the moon, cracking a wide grin at a jaunty angle. The neighborhood was silent except for the occasional passing car or barking dog, and there was no one around to see her, or her carefully chosen sweatpants, as she passed under streetlights and windows. The night was clear and cool, and the world looked softer under the waning moon’s faint light. She felt herself calm down a bit at the sight and slowed down to a normal pace. After a bit longer, she reached a cul-de-sac with the woods she was looking for. Without hesitation, she walked right into the dark trees. The night should’ve made the trail into a death trap, but she had snuck through here too many times not to remember every odd bend and gnarled root. When you had a mom like hers, you found ways to get your fix. Sure, things had grown or been cut down over the years, but if she squinted, the darkness almost made it seem like nothing had changed at all. She cracked a small smile when she recognized the faint outline of her old rope swing, the big rock she would sit and read on. She should do this more often.

She emerged from the trail and onto the sticky new asphalt of the grocery store. She grimaced at it briefly while walking briskly up to the brightly lit doors of the store. She averted her gaze as her dilated eyes adjusted to the blinding glare. She was surprised by the number of shoppers looking to grab some last-minute dinner ingredients or midnight snacks. A wave of nausea spread through her skull, her mouth filling with saliva and the taste of pennies. She probably shouldn’t have pushed herself so far in one night. The trail was fine, even pleasant, but this was too much. The tinny blare of the speakers, the stream of “Thank you” and “How are you” from cashiers and customers alike, burning fluorescents flickering furiously. She knew when she had bitten off more than she could chew, and this time it wasn’t chocolate cake. Moist, rich, devil’s food cake. Birthday cake and birthday wishes. She stood there, hands

balled into tight fists at her side, eyes fixed on the ground as shopping carts and people swerved to avoid her. She didn’t know when or how, but eventually she walked through the automatic doors and into the store.

Her heart bounced around in her chest as she beelined for the baked goods. She anxiously stood up on her toes and craned her neck to look through the shelves and shelves for a chocolate cake, but there was nothing fresh at this hour, and all that was left was bread. Shaking her head, she sped over to the refrigerated displays nearby. The lights for this section had fizzed out, but the cooling still worked. She felt a pleasant coolness envelop her hands as she plunged into the dark depths and retrieved her hard-earned treasure. A day-old grocery store chocolate cake. The list of preservatives and conditioners wrapped around the side of the flimsy plastic container and the slightly melted frosting and sloppy lettering were now plain as day, yet she handled it as if it were a child. She carefully brought it to the checkout and stared at the floor while the cashier gave a half-hearted greeting. As he scanned her one item, she fumbled with her wallet and swore under her breath when some loose coins tumbled out. But she didn’t care. She paid for her cake, and now it was hers. She stopped just outside of the store, light streaming from behind her. Her head blocked most of it, but she could still make out the sprinkles and piped frosting with the help of the moonlight. It was perfect. Somehow, this little stunt of hers had worked out. She walked carefully to the edge of the parking lot, but started to pick up her pace as she passed through the trail. She ignored the sights. Her walk turned into a jog as reached the cul-de-sac, the cake jostling in its container. She always got some sort of preemptive sugar rush when she finally got her hands on sweets, but her mother would still manage to catch her anyway. Her father would always make a stern expression and stand right alongside her mother as she lectured, but would inevitably sneak some to her with a jaunty wink when the coast was clear. These days she rarely saw his face at all, and when she did, it was always etched deeply with weariness. Of what, she couldn’t tell.

As she paused to catch her breath and fish out her keys, another smile found its way onto her face. She really should do this more often. Little trips like these made her happy, and at the very least got her out of the house and out of her head for a little while. Sure, it was later than usual, but she didn’t mind really. Maybe she’d get ice cream next time. She unlocked the door and pushed it open with her back. Of course she wouldn’t go for snacks daily, but it would be a nice change of pace once in a while. She set the cake down on the dining table and grabbed a fork. She could make a habit of going out to the store at least—get fresh food, see people. That would be nice. She lifted the top off the cake container and went straight for the—ah. Might as well. She got up and dug through the cabinets for a solid five minutes. She sat back down and carefully placed a stubby pink candle on the center of the cake.

The room was only lit by the moon peeking through the window over the sink, still with its bright little smile. She flicked the lighter and held it up to the wick,

feeling the warmth of its tiny flame. It danced and sputtered and made the shadows of the kitchen writhe like snakes. She closed her eyes and made a wish she should’ve made a long time ago. A simple wish. Her only wish. She blew, and she wiped her eyes as she took a big forkful of frosting. Things were gonna get better. They would. No matter how long it took or what she had to do, she would do it. She would do something for her father when he came back. He always liked garlic bread. She could make that. She braced herself for sweet, sugary goodness. She finally took a bite. It hurt her teeth. Tomorrow, she would call her moth-

She felt hot, sour bile hit the back of her throat and slammed a hand over her mouth as she ran to the sink. Her empty stomach cramped and flexed as it tried to empty itself of nothing at all. The kitchen was silent except for the sounds of her dry heaves, interspersed with choked sobs. After some time, her stomach finally gave up and she straightened up from over the sink, bracing herself against it with her arms. After rinsing her mouth out from under the faucet a good five times, she slowly padded back up the stairs, and gently closed the door behind her without a sound, leaving the cake on the table.

Only a single bite was missing from its frosting, barely exposing the cake underneath. The candle had burned down to a stub, and its low flame melted the frosting. It glistened like spilt blood, and the cake was black and craggy like old scabs. Some time later, the candle fell over, and went out. The kitchen was dark, except for the moon’s soft gaze.

Andrew Zhou

The Ringmaster’s Quiet

My workplace stands among thick, wet fog, past the grocery store, hospital, and Mexican cafe. Nailed to muddy, crooked poles on the verge of collapse are the yellows and marigolds of the great circus tent.

I sweat in summer heat, trapped under a sky of striped sheets, dodging candy wrappers caked in mud and coworkers already three swigs in, my senses overcome by crackling nerves warped in sour stenches of popcorn and beer.

And then, like always, at six o’clock sharp, I step onstage, and suddenly, I soak in Quiet.

My voice rings out, sure and crisp, clear as a wave washing through the crowd. My arms and feet sail upon instinct, like machines programmed just for this moment, and I am a dragon, gliding gracefully on ice, a shiny long ribbon curling with the wind, each motion timed perfectly with beating drums, all while wide eyes and ponytails stare back in wonder.

At last, I stand, center stage, bowing as a stream of applause flickers in, a burst of approval from those I’ve dedicated my life to please.

Then, as quick as the stroke of a brush, they gather their purses and coats, and head home, soft murmurs of work and school looming over them.

But me, I’ll be here, ‘til the harsh lights fade out, and the tent’s bright colors fade to gray, sweet with childish anticipation for all I’ve amounted to that Quiet, once again.

Kate Killen

Ballad for a FedEx Driver one

Tuesday Half-Past Noon

2-steps down, right foot on cracked Sidewalk to 4-steps to rusted fence

Gate unlocked to 6-steps to broken Doorbell and package placed To 6-steps 4-steps 2-steps up and again

Was written on his arms crossed On the idling steering wheel he Found too soft for a heavy midday head

Lost between packages and pizzas and this drizzling windshield

I saw him through, tracing his 4-steps on cracked sidewalk he walked So many times before And caught in the swirls of his thinning hair That delivered so much and found so little

ln the orbit of these worn orbs he Left in the depths of his crossed arms

That blurred the sound of suburban headlights That colored in the puddles he so effortlessly navigated and yet

Left to navigate the world

In 2-step 4-step 6-step

In stiff-legged gearshifts and packing peanuts In a million practiced steps in time

A waltz

Caught in this whirlwind Of forgotten addresses and faded doormats Of unkempt grass and garden damp kids’ toys

A ballad of unmentioned existence

In Liszt

Whose dream was it? I wonder

To run the world in steps

To subtly scan barcodes in E-minor

And dance these lonesome love songs As one

As I walk past I imagine him waking In a start, glancing surreptitiously at his monotonous metronome And shifting softly into drive, He disappears in a December drizzle unmissed

A trail of twisted nocturne begun.

Sterling Peterson

Halloween, Two Years after My Grandmother Died and Avoided Any Diagnosis at All

After Erika Goodrich

The leaves disintegrate as they fall They are gone before they hit the ground. Pollen rises up, a last rebellion, And fills my lungs with poison. I cough up leaves. Trees are planted Wherever I go.

I do not understand the world. For two years, it has darkened And widened and warped. I can’t see properly, So I go to the eye doctor, Who gleefully declares My vision perfect. Liar. I beg him for glasses, For a headlamp, for a cane. He has a hyena’s laugh.

I have kept pace with a ghost For two years. She doesn’t understand The world either. She yells That she understands perfectly. She yells in one year, then the other, And I stumble as I walk From the weight of her voice.

Once, I decide to run. I wait until I’m at the top Of the steepest hill I know. I take off, letting the decline Take me faster. The ghost Lags behind. I feel myself Lighten, and I am two degrees Warmer. Suddenly, I fall.

A sharp pain in my hip I should have replaced it years ago

A ringing in my ears, Declaring dead batteries, My hands start to wither like the leaves, I dissolve into the ground.

When I awake, it is November. In twenty minutes, I will sit up, Put on a pair of jeans, and Arrive to therapy on time. After that, I will eat a meal, And maybe I will call my father. All that remains of my grandmother Is the vampiric scar on my forearm She left when she was alive and By some accounts—well.

Grace Whitaker

It Passes Me By

Things I have not started:

three discussion posts reflecting on towers of text constructed by theories on media literacy

two replies per post on the posts of others reflecting on towers of text constructed by theories on media literacy one five-page rough draft on a novel that impales me in the chest on every read one handwritten paper on something we’re not even learning in class one article for the newspaper on book banning that I still have to finish transcribing the interview for two articles for the magazine that must be cute and fun and not full of the impending doom that clouds my generation’s future three articles to edit that are cute and fun and do nothing for the impending doom that clouds my generation’s future one call to Abuela to ensure she is well even though I know she is well (but I don’t) one call to Papi because he started calling me too. one mother to call because I miss her one friend who needs attention because something else happened on social media that has nothing to do with me two friends who want to do brunch when I don’t have the time or money.

The blanket is wrapped around me and my thumb is robotic and dutiful as it scrolls, perfectly catered to my attention span for each post in the endless rope of sixteensecond videos. Numbers and obligations and dates and people bob around in my head like buoys in a vast ocean, except they are pulsating and wrapping around my chest, holding my delicate heart and screaming at me because they are easy. So easy, so doable, and yet I cannot move my body apart from my thumb. My laptop is on my desk, just out of reach, but even if it was within the span of my arm from the dent I’ve put into the mattress, I am not sure that I would be able to reach out and grab it with my stiff fingers. I can move but I will not, and I cannot tell the difference.

I am a good daughter. I am the daughter that went to college and had all the encouragement in the world. The reading and the honor roll and the big dreams and the tidiness and the plans and the future and the desires and the writing—they convinced them that I would do it. The editor. The journalist. They want it for me, and I have every tool in the world to succeed if I just try.

The aforementioned buoys that pulsate do so in time with the beat of my heart and they thump to the tempo of my pulse. I forget nothing, but I am paranoid I will forget

everything. With an agenda, sticky notes, an iCloud calendar, Google Calendar, phone reminders, alarms, and trackers, how could I? How could I, I ask, as these things gather dust on my desk and rot in the digital ether. Nothing binds me, and yet I am always bound, helpless to do anything except remain acutely aware of each thing that sits idly, awaiting the attention I cannot seem to give it.

I keep scrolling.

Cristina Rodriguez Velez

I know your image of me is what I hope to be.

You can see everything from Margaux’s third story window. We sit in her single dorm room together, myself in the window seat adjacent to her unmade twin bed and her laying upside-down off the side—copper hair dangling off of the edge. Her arms are folded across her stomach, her long lean legs extended against the wall while she stares intently at the ceiling. This tends to be the configuration of Margaux and I when we find ourselves in her room. The room is small, much smaller than my own, but I have the luxury of sharing a room, while Margaux is one of the few students who gets her own dorm room.

“I’m not gonna be in French tomorrow,” Margaux says.

“You didn’t go to French on Wednesday, either,” I acknowledge.

“I know. It’s not like I need to go.”

The truth is, Margaux and I would have never become friends if it hadn’t been for French. Margaux walked into school last fall, a five-foot-ten figure of confidence and remarkable beauty. Her hair was light brown then, but I think the red suits her much better. Her eyes are vivid, green, and intense, and her face is almost perfectly symmetrical, covered in freckles from a summer spent tanning at her home in the Hamptons. Above all else, Margaux is fierce. Most of her friends would say she is much nicer once you get to know her. I know better. I know Margaux is just a bitch. When she found out I, too, have spoken French for most of my life, French became her outlet for the real feelings she held for our peers.

“When do you leave?” I ask.

“Tomorrow morning.”

“Is your mom picking you up?”

“No. I’m taking the train.”

“How are you getting to the train station?”

“Ally’s gonna take me.”

“Ally Crane?”

Margaux nods her head.

“I thought you said she’s annoying and you guys aren’t really friends anymore.”

“She is annoying, and we aren’t.”

“Then why is she taking you to the train station?”

“I needed a ride.”

“Does she know why you’re going to the train station?”

She laughs. “No.”

In one motion, Margaux sits upright on her bed and crosses her legs.

“Is your mom gonna get you from the station tonight?”

“My mom doesn’t know I’m going to New York.”

“Oh.”

“Are you scared?”

“No. I just need to get it over with already.”

“I would be scared.”

“I know.”

I watch Margaux tear a piece of skin from her fingernail with her teeth.

“What would you do if you were me?”

“I don’t know. I would tell my mom.”

“I know. I can’t do that.”

“Are you just gonna stay in a hotel?

“No, I’m staying at Jack’s.”

“You need to tell your mom.”

“I won’t tell my mom.”

“You can’t stay at Jack’s.”

Margaux tugs out a strand of hair.

“I don’t feel bad about it.”

“Not at all?”

“I mean a little. I might feel differently after it’s over with.”

“Like guilty? Do you think you’ll feel guilty after?”

“No. I won’t feel guilty.”

“I don’t know. They say a lot of people feel regret after.”

“Won’t be me.”

Margaux’s bed has a poster of Amy Winehouse above it. She has a small bedside table with a pink Tiffany lamp that looks like a dying rose. Her pen is upright and in arm’s reach of her pillow, so that the oil is concentrated at the bottom for when she takes a hit. Margaux has smoked since she was thirteen. There’s a lighter too, one of the cheap ones you get at a gas station. There’s a pill bottle with an emptying Prozac prescription, a Poland Springs water bottle—half empty, and her retainer, which I have never seen Margaux wear, but her teeth remain as perfectly straight as the day I met her. Finally, she has a small figurine of an angel playing the violin. You would never think Margaux is a particularly religious girl when you meet her, but she prays more than anyone I’ve ever known. Sometimes, she offers to pray for me, and despite the fact that I myself don’t believe in any sort of God, I always find myself at ease when

she does.

“When do you think you’ll be back?”

“Sunday.”

“I’m gonna be so bored without you here.”

“Don’t you have a game this weekend?”

“I’m gonna watch a game from the bench this weekend.”

She laughs. “At least I won’t have to watch you watch a game from the bench this weekend.”

“I should just quit already, right? I literally hate going to practice.”

“You know what I think.”

“Yeah. I don’t know, though.”

She pulls out another strand of hair.

“You should really tell your mom, Margaux.”

“You don’t know my mom.”

“I don’t want you to be alone.”

“I won’t be. Jack will be there.”

“I’d rather you be alone than with Jack.”

“Do you want me to come with you?”

“No.”

Margaux rises and grabs her pen off her bedside table. Her hand shakes while she holds it.

“You know my mom had one once.”

“Lots of people do.” She shrugs.

“It seems like this big scary thing the way people talk about it, but it’s really not. I don’t think my mom ever really thinks about it anymore.”

“Well, it was probably a really long time ago. I would hope she doesn’t think about it anymore.”

“You’ll get there at some point. Maybe not Sunday, but someday.”

“Would you?” She says.

“Get over it?”

“No. Come with me.”

“I’m not staying with Jack,” I say firmly. She turns away from me and takes another hit from her pen.

“I love you, Margaux. I would do anything to make this go away for you.”

“I know.”

We sit in silence for a while. Margaux glides across the room and sets down next to me in the window seat. It’s not really a seat for two people. She rests her chin in her palms and looks away from me, directly out of her third-story window. Her nail beds are raw. Sitting there, she looks small. Younger than she has ever looked before. She looks her age. She looks fifteen.

“I want to come with you,” I whisper.

Margaux’s eyes are fixed out the window.

“We can stay with my sister instead. The one that lives in Brooklyn.”

There is no need to respond. I know that she would never swallow her pride and tell me she needs me.

“I can get a ticket right now?”

I pull out my phone. Margaux is perfectly still looking out the window. Her eyes are like glass. She blinks quickly.

“If you don’t want me to go, tell me now.”

She doesn’t.

Margaux has a Stick-n-Poke on her left hand. It’s hidden on her middle finger, just below her knuckle. It looks like it’s just a circle but I know it’s an O. For Ophelia. Her younger sister. She rubs her thumb against the O when she’s nervous.

“You’re gonna be okay. I promise.” I tell her.

“I hope so.”

She looks at me.

“I don’t know.”

Chloe Cella

Raid

After

Edvard Munch’s Anxiety

I.

I am drawn into the ant man. Pressed in periphery, he long-face glares into something outside himself. I am spun on the rim of his bowl eyes, then slipped down into the hollowness. I return dry oil drenched.

I know I don’t have the words. I know I was fifteen, suburban, shoulder to shoulder with a weird boy, mostly a loser, looking down a drainage tunnel for frogs.

I spend time, sometimes, in the abandoned construction site he showed me that day, after tripping across logs and barely swimming streams.

Red rasped thistles, southern dewberry before its time. I step on what I can trample, and bear what cuts me.

Sobered, I stand overlooking the dam he said he used to walk down and back and wish he wouldn’t make it.

I see the hillside slope into the orange purple water. I am something unnatural in this forest cut-out.

II.

It comes to me when I bamboo-brush my hair: your hands teasing through it, looking for lines to break it into three strands. I want you to french braid my hair, want it to be long enough to make two hanging

braids. In this, you would slump in the green velvet chair, straddling my neck, hair in your mildew hands, tugging me back as the walls stain with weed

I would sit where you could reach.

I wonder who is going to sweep the ant man up. Print and pin him to cork.

From the wall of my childhood bedroom, He watched me.

I was strung out to Richmond. On the James, holding its indigo ripples, I know I will never harness this love for you again, know it will flow in and out of me on some other accord. Know it will kick.

Know the grainy bedroom rug my face will grind into. Stoned beyond affection, lying in swirling purple, I drink the fluorescent mirage of you in my well-upholstered chair.

Alone there now, the cats come claw at my door. Sometimes they slip in when I leave and get stuck pawing, yelling out from sunken throats.

Bella LoBue

Madeline

Madeline, her only son, called them close to midnight.

The television spit blue shadows across their wallpaper and each waited for the other to answer, waited for the other to give in. Between every ring, the pauses grew thicker. When she wouldn’t flinch, Frank, her husband, pulled aside the sheets and groaned his way to the kitchen. She turned down the program and tried to listen. After a few minutes, his voice started to rise and she straightened her neck against the freezing headboard. But soon she didn’t have to strain anymore because Frank stood in the doorframe, gripping the jamb.

“Molly,” he said, “you need to get this phone away from me.”

She did not wear her slippers and the linoleum bit up into the soles of her feet. The room carried a draft but when she traced her eyes across the countertops, the cabinets and window panes, everything looked sealed. The phone lay at the end of its tangled cord, waiting in a puddle of tap water for her fingers.

“Hello?” she asked the line.

“Dad’s still there,” Madeline said.

“He’s gone now. Back to bed.”

“I can hear him breathing.” Madeline wasn’t doing the voice this time. Each vowel caught a low notch in the throat, kept itself in balance.

“That’s only me,” she told her son.

In the dining room, the dog scratched at its cage. Branches clawed against the kitchen window. They took turns, the dog then the trees, repeating the same sound. Finally, she started with the words, “How have you—” but Madeline cut her off with a parallel mumble.

“Sorry,” Madeline said, “you go.”

“No, no. Please.”

She could hear another voice on the line. Maybe the television.

“I want to talk about Hansen,” Madeline said.

“Alright.”

“Because Hansen and I are married now.”

She traced a finger across the countertop. Dipping her prints in sink water, she pulled lines out from the puddle until they dried. Then she glanced out of the window and felt glad her reflection looked blurred. “Married,” was all she said.

“Yes. I wanted to let you know.”

“And this happened already?”

“About a month ago.”

Her molars felt loose, like baby teeth draining their roots.

“I would have liked to be there,” she allowed.

“I think you know that’s not true.”

“Well, it’s your choice.”

“Why say it like that?” Madeline asked.

“I don’t know.”

“Are you sorry you said it?”

“No.”

Now she twisted and righted her face in the window. She dreamed it was a mirror and thought about turning out the light.

“I just wish you could have told me,” she said again.

“Are you going to tell Dad?”

“If you want me to.”

“I want you to.”

“Okay then.”

Madeline drew a slow breath through the receiver. The other voice inside the telephone whispered again, closer now. “So now you know,” Madeline said, “yeah.”

She could feel her heart climb up and down her neck. Every grain in the linoleum seemed fused to the skin on her feet. “Hey Matthew?” She said. But the line was already dead.

As soon as she snapped the phone into its wall socket, Frank crept back toward the bedroom. He tried to be quiet but, at sixty-nine years old, his steps pulled heavy creaks out of the hardwood. She stopped in the middle of the kitchen and gave him enough time to retreat. One Mississippi...five Mississippi. When she peeked back into their bedroom, the TV still blinked across the sheets and he hid there, balled around the comforter, with his face beneath a pillow.

She walked back into the kitchen and pretended it was already morning. She poured a bowl of cereal and a glass of milk, deciding to enjoy them both on their own. With half the bowl ignored, she went to the dining room and sought out the dog. An old Pomeranian with black, crusted rivers pooling around one eye. The dog snipped out quick, feminine yelps, scratching at its cage. She gathered it in her arms, bending over the gate, and recoiled at a new smell. On three of the training pads, it had made a mess.

She carried the dog down to the basement. Past photographs and a wallpaper called eggshell, not white. Madeline’s things still waited in their proper places: the made bed, the posters, a self portrait her son had drawn in the second grade. She drifted over to the sliding glass doors and stepped out onto the patio.

The wind worked its way around her breath. Out here, the pines bent. They took turns, sanding their bark together, and she thought they might rub fast enough to start a fire. The dog writhed underneath her armpit, flailing little paws against her robe. She moved to put it down, then stopped herself. In her fears: hawk talons, mutilators, the yellow fangs of a coyote. She walked out onto the grass and braced herself. Giving in, she placed the dog on the ground.

Married, the phone had said.

She whispered for the dog to stay, and it did for a moment. Then it twitched its nostrils around the clean, cold grass, and circled a mulch bed, urinating near the garden hose. In the dark, it slipped into a bramble of hydrangea stalks. She dug her toes through the dirt, waiting. The dog made these little rustlings. Then it didn’t. After a minute, she stooped low and rooted through the bushes, but only found knots and dry leaves.

The wind cried louder—she tried calling through it. Nothing. Maybe the thing had crawled back inside. With her chin to the ground, she whistled. But that fell flat too.

Peter McHugh

Transform

I wake up early for the doctor’s appointment. I’ve been waiting for this morning for years. On the walk there, the weather is warm for September and my chest is tense, but the voice in my head sings, Today, today, today, finally.

Testosterone.

Harvard Health says, “Testosterone is the major sex hormone in males. It is essential to the development of male growth and masculine characteristics.” The development in question is not standardized, especially when it’s synthetic and late. Charts show ranges and estimates and risks and benefits. Expect your voice to drop around six to twelve months in. Watch your cholesterol levels, and keep an eye on whether your hairline recedes. Some people grow a full beard, others don’t. It comes down to the sheer luck of genetics, so I will wake up every morning to rub the clear testosterone gel on my shoulders, and I will have to wait and see what my body wants.

I’m older, more prepared than when I first went through puberty, and this time it’s my choice. Before, I was ten years old and voiceless and armed only with the American Girl’s Guide to Growing Up. Being a girl had always been fraught: I was perpetually on a fierce defensive against derision, knowing I had to be proud and run fast and be smart or any failures would be attributed to my gender. All this pressure to perform, even knowing that a girl could be endlessly multifaceted, could be dirty knees and climbing trees and engineering, because my sisters were those girls. But as my shape plumpened, blood started to flow, hips rounded, I realized that growing up meant becoming a woman—and that was crossing into territory I didn’t want to enter.

I was fascinated by the growth of hairs, trailing across my body in different shades: pale blonde on my thighs, tan on my arms, dark around my ankles, even darker under my armpits. My fingers missed the youthful smoothness but studied the texture, realized these follicles were patterning my doom, my puberty. I remember late at night pressing my blooming chest to my sides, wishing that it could stay flat like that forever.

Soon, an itch will flare up in my throat, like sharp ants rasping paths up and down my vocal cords. My voice will start to crack, like old floorboards—I will learn the patterns, learn how to step carefully, but inevitably, when I’m not careful, I will squeak. My jaw might square out. I worry I’ll look like a pitbull, but I remind myself that many people think pitbulls are endearing. The acne that has just settled down from its teenage angst will tear across my face, invigorated. These hips will flatten, arms will strengthen, hair will coarsen paths across me. I want to lose my body in a forest of fresh, dark hair, precious freckled skin sheltered in shooting brambles. I want the patches on my legs where friction wears away hair to thicken.

I must remember that I act for my own reflection. I cannot fight for other people to see me in some way: I am not reshaping my body for the strangers at CVS. To attempt to curry favor will only lead me to scrutinize myself, to feel that I will never be good enough.

If I could, I would trap this body in the midst of metamorphosis, the land of the perpetual traveler. The animation plays; I leap to press pause at the transitioning frame, where the body has yet to become, is becoming. I don’t long to bathe in a fountain like Salmacis’s, but to splash water on my face, rinse my hands, taste a little of its sweetness.

They draw my blood at the end of my appointment, to ensure my various hormones and levels are as expected so they can proceed safely. Afterwards, a BandAid creases at the inner crevice of my elbow, beneath it a small scab forming where the adhesive is too strong. I run my finger against the uncomfortable fabric and think of the growing pains awaiting me, soreness as parts shift and swell and deepen. The caterpillar liquifies itself to become a butterfly, but I am not asking for my bones to be dissolved and remade. I am simply asking to take a step to the side, to be put through the first funhouse mirror, the one where you’re just beginning to see how you’re being changed.

I am light-headed all day. I am giddy, nervous, working out how I’ll put this into words when I tell—not ask, but tell—my parents how I am choosing to transform. I am choosing this: I will transform. I will transform.

Eli Hiscott

Resurrectionist

Bind my wrists behind my back

Place the noose around my neck

Call me body snatcher, grave robber, ghoul.

I do not fear these epithets as

I till the soil of paupers’ graves

And pull the reaper’s firstfruits from the earth.

The mourner, the parson, and the sexton

Are no more intimate with the dead than I.

Do they admire the moonlit gleam

Of pale skin set against dark soil?

Cold and perfect as the Elgin Marbles

If only for a night

Before the blood pools and skin sags

The flesh festers and bowels distend.

This treasure, ephemeral as frost,

Belongs to no one, alive or dead

I merely recover this buried asset

For the physicians or the anatomists

As they yearn for finer specimens

Than a paltry portion of the hanged.

Yet, here I stand, on the scaffold

For taking the silver ring of a serving girl.

The law had precious little objection

To her golden hair going to the perruquier

Or her mouth’s pearls adorning fine ladies

Who indulged in an excess of delicate confections.

Yet a ring, hardly worth ten pounds to the pawnbroker

Has turned a petty criminal into a man condemned.

Come morning, I will adorn an anatomist’s table

Perhaps he will weep as he takes scalpel to skin

Remembering the nights I returned from the graveyard

Leaving my cursed bounty at his backdoor

When he sees that breath no longer stirs my frame

Perhaps he will mourn an old acquaintance

And find solace in this truth:

Resurrectionist that I am

My cold body will go on to bless the living.

Grace Sawyer