The Visual Artists’ News Sheet

November – December 2024

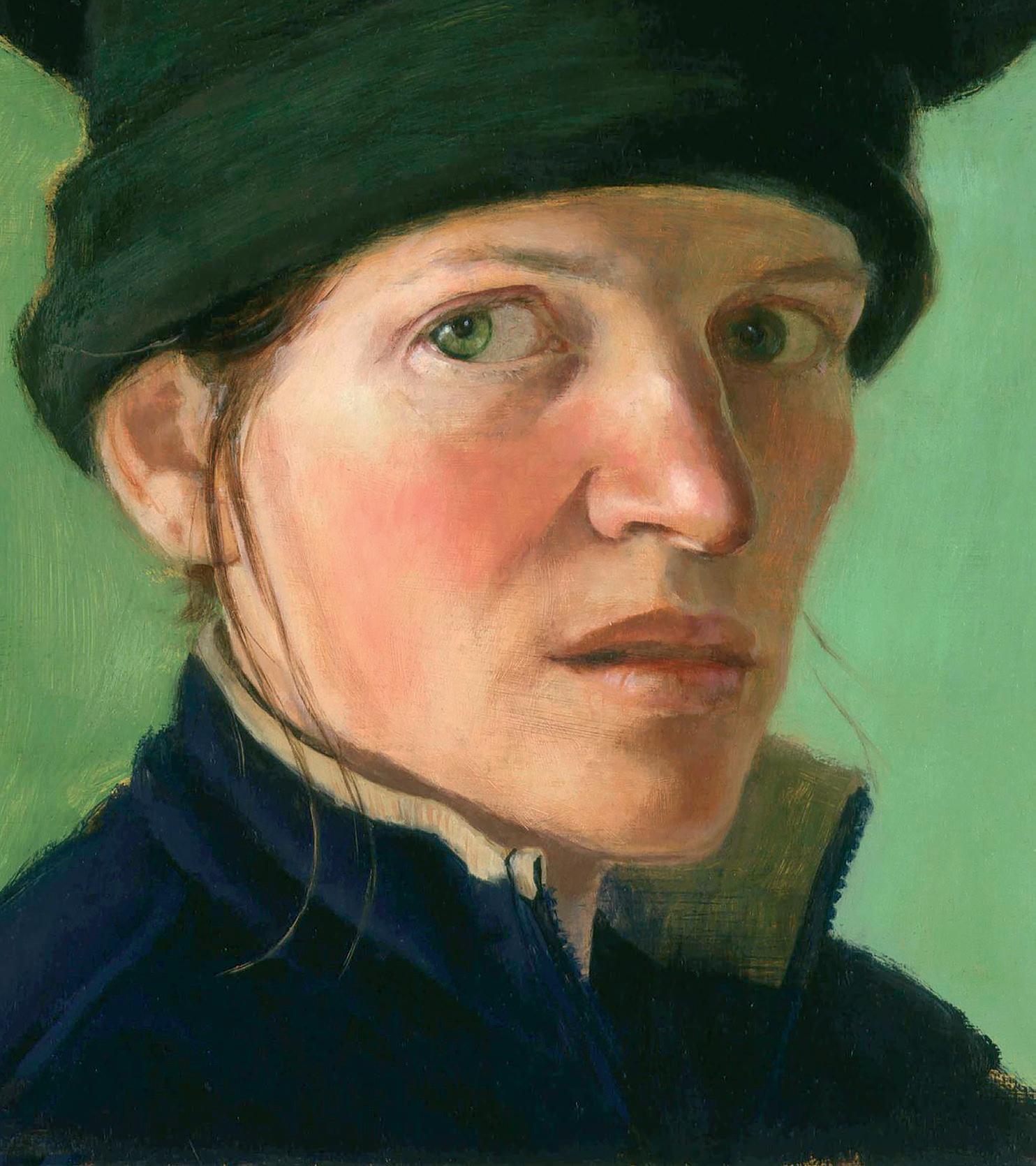

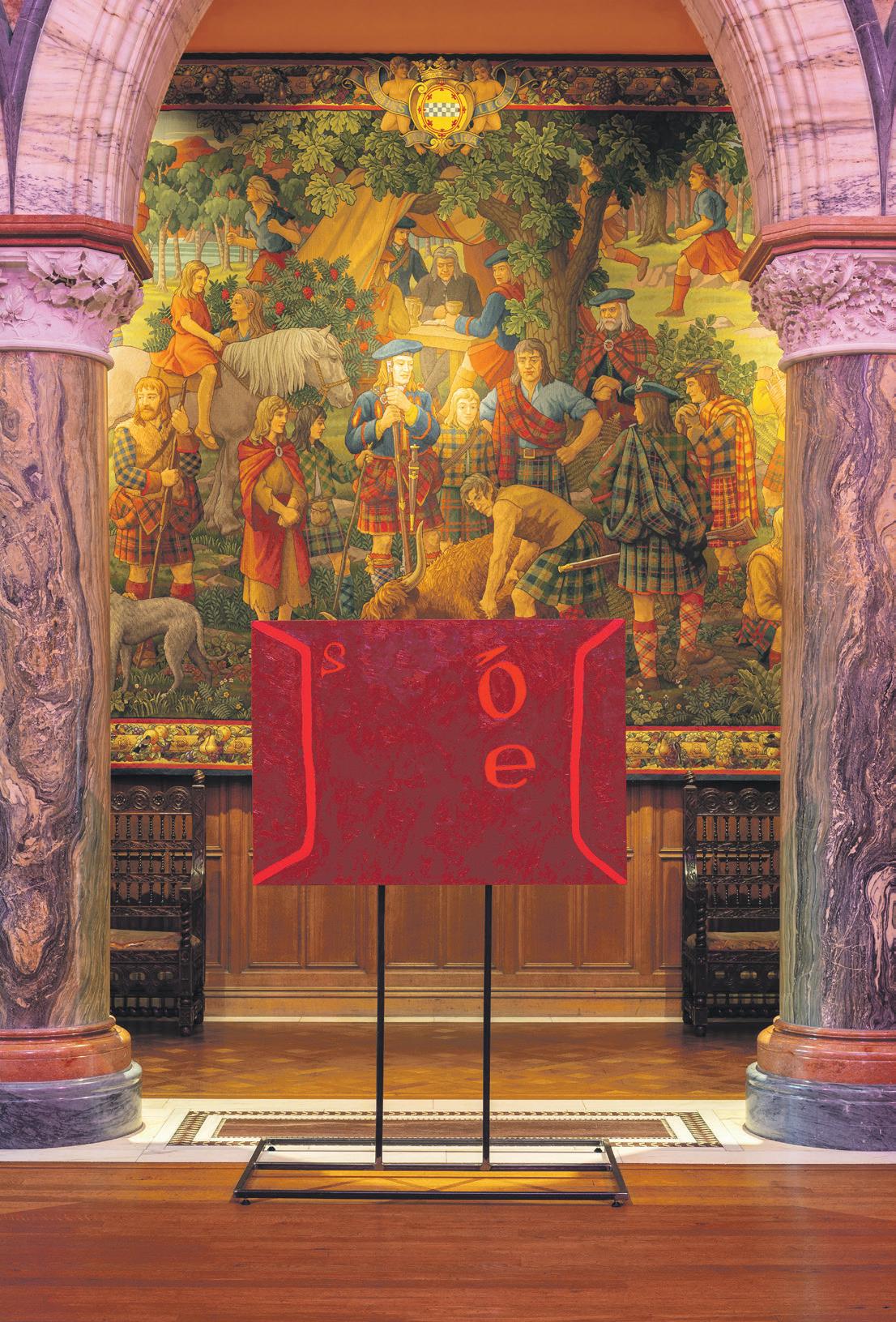

Oisín Byrne, ‘smell the book’, installation view, Mount Stuart, Isle of Bute, Scotland, August 2024; photograph by Keith Hunter, courtesy of the artist.

Infrastructure

6. Residency Roundup: Where Can I Find a Residency in Ireland?

8. Can You Advise on Establishing Communal Studios?

9. How Can Buildings Be Secured for Arts Organisations in Northern Ireland?

Art Work 10. How Can I Prevent Burn-out as an Artist? Access 11. How Can Irish Artists Pursue Opportunities Abroad? 12. How Can the Irish Diaspora Participate in Ireland’s Visual Art Scene?

In Focus: Funding Case Studies

What Kind of Funding Exists for Artist-led Projects?

13. Fiona Whelan and John Conway, Arts Council and 221+ Patient Support

14. LennonTaylor, Local Authority

15. Anthony Haughey, Decade of Centenaries

16. Vivienne Griffin, Culture Ireland

17. Frank Sweeney, Arts Council of Ireland: Project Award 18. Sharon Kelly, ACNI SIAP: Major Individual Award Critique

19. Emily Waszak, Bodies, Jomon time, 2021-23, installation view 20. Debbie Godsell at The Source Arts Centre 21. Alice Maher & Rachel Fallon at Irish Arts Center

22. Dermot Seymour at Kevin Kavanagh

23. ‘Thresholds to the Unseen’ at Solstice Arts Centre

24. Liane Lang at Butler Gallery

Exhibitions

26. How Can I Get An Exhibition? Top Tips from the Sector Ecologies

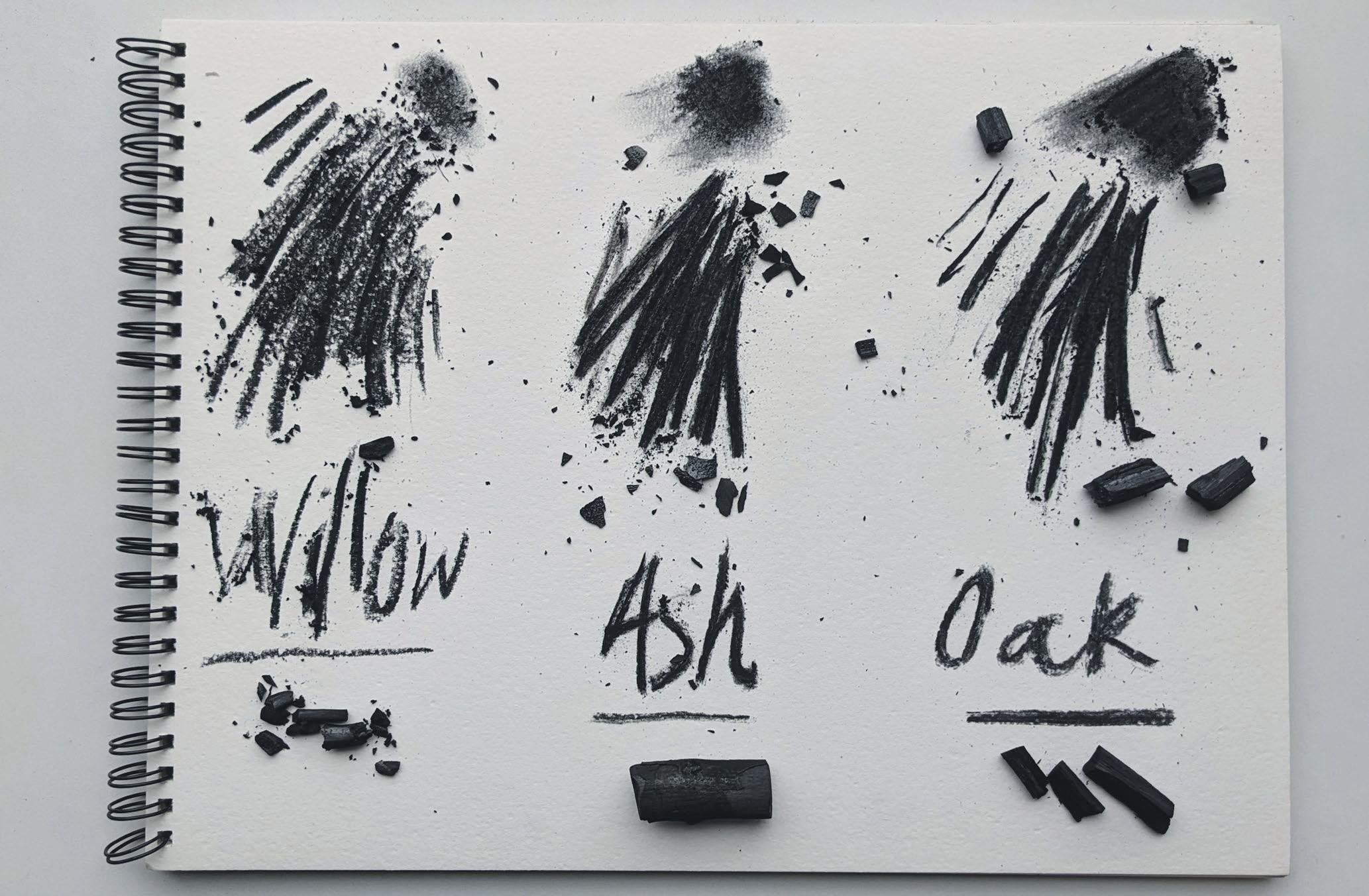

35. What Are My Options for Greener Art Materials? Sally O’Dowd, Making Charcoal from Ash Dieback Materials Matter, Recipes for Sustainable Art Materials

38. Where Can I Find Art and Ecology Resources? Deirdre O’Mahony, Feeder Bibliography VAI Resources to Support a Greener Approach

VAI News

41. Are Organisations Offering Artists Fair and Competitive Rates for Their Work?

Update on Payment Guidelines for Artists Call to Action: Artist’s Resale Rights

42. Where Can I Find Professional Development Resources? VAI Webinar Recordings Archive

43. Where Can I Find Professional Development Supports? Explained: VAI How To Manual Belfast Peer Support Programme

Last Pages

45. VAI Lifelong Learning. Upcoming VAI helpdesks, cafés, and webinars.

46. VAI Get Together 2024. Programme Details and Booking Information.

The Nov/Dec 2024 special issue of The Visual Artists’ News Sheet has been directly informed by an open call for members’ questions we ran during the summer. VAI members were invited to submit their questions for curators, gallerists, directors, critics, policymakers, funders, or fellow artists, which we subsequently posed to relevant arts professionals across the sector, whose responses are published in this issue as a series of specialist columns, interviews, policy updates, and case studies.

During our VAN Nov/Dec editorial meeting, a colleague described this issue as “taking the pulse of the sector”, given its timely reflection of artists’ concerns across a broad range of subjects, loosely categorised across themes of access, infrastructure, funding, exhibitions, and ecological concerns.

Such was the demand from artists for information on securing exhibitions, that we have devoted a whole section to this inquiry. This is also one of the most common queries received through the VAI Helpdesk. We consulted with curators and directors across a range of different institutions and have assembled their top tips in an extended feature article: How Can I Get an Exhibition?

Another recurrent question from members relates to funding strands available for artists wishing to develop projects in Ireland, Northern Ireland, and internationally. In response, In Focus: Funding Case Studies offers examples of projects variously funded by the Arts Council of Ireland, Local Authorities, Culture Ireland, Arts Council Northern Ireland, and the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media’s Decade of Centenaries programme.

The Visual Artists’ News Sheet:

Editor: Joanne Laws

Production/Design: Thomas Pool

News/Opportunities: Thomas Pool, Mary McGrath

Proofreading: Aifric Kyne

Visual Artists Ireland: Republic of Ireland Office

CEO/Director: Noel Kelly

Office Manager: Grazyna Rzanek

Advocacy & Advice: Oona Hyland

Advocacy & Advice NI: Brian Kielt

Membership & Projects: Mary McGrath

Services Design & Delivery: Emer Ferran

News Provision: Thomas Pool

Publications: Joanne Laws

Accounts: Grazyna Rzanek

Special Projects: Robert O’Neill

Board of Directors:

Michael Fitzpatrick (Chair), Lorelei Harris, Maeve Jennings, Gina O’Kelly, Deirdre O’Mahony (Secretary), Samir Mahmood, Ben Readman.

Visual Artists Ireland First Floor

2 Curved Street

Temple Bar, Dublin 2

T: +353 (0)1 672 9488

E: info@visualartists.ie W: visualartists.ie

Northern Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

109 Royal Avenue

Belfast

BT1 1FF

T: +44 (0)28 958 70361

E: info@visualartists-ni.org W: visualartists-ni.org

Ava

Fionn

Heather

Keara

Kyle

Sorcha Browning

Stella De Burca

featuring work by Aaron Dees

Eileen Fair

Matthew Gammon

Joanna Hopkins

Shelia Hough

Sarah Ellen Lundy

Kathryn Maguire

Susan Mannion

Margo McNulty

Ursula Meehan

Kathy Raftery

Gary Robinson

Curated by Eamonn Maxwell

Roscommon Arts Centre

1st November – 20th December, 2024

Opening 6pm Friday 1st November

All welcome

www.roscommonartscentre.ie

T: 090 662 5824 / 090 663 7320

Roscommon Arts Centre are delighted to present the HIVERNAL exhibition featuring work by Aaron Dees, Eileen Fair, Matthew Gammon, Joanna Hopkins, Shelia Hough, Sarah Ellen Lundy, Kathryn Maguire, Susan Mannion, Margo McNulty, Ursula Meehan, Kathy Raftery and Gary Robinson. The exhibition is curated by Eamonn Maxwell. The exhibition is result of an open call for artists living in Roscommon and its bordering counties – Galway, Leitrim, Longford, Mayo, Offaly, Sligo and Westmeath. The 12 artists in the exhibition were chosen after a rigorous selection process.

Hivernal is derived from hiver, the French word for Winter. Artists were invited to respond to the theme of the changing seasons – in particular the transition from Autumn (Lúnasa) into Winter (Samhain), the celebration of Halloween and the fading light at this time of year. Works in the show include audio, installation painting, performance, photography, sculpture and video. The artists responded to the theme in wonderfully evocative ways. Themes and approaches include soundscapes inspired by changing seasons, a portal to transport us to Winter, the crow as representation of Samhain, The Cailleach Béara as a symbol for the duration of Winter, the turning of life as bog painting, the natural world, changing seasons as alchemy, the shortening days, Edgar Allen Poe’s poem “The Raven”, the cycle of life, retirements as akin to the fading light of autumn and Oweynagat as the birthplace of the Samhain

Whilst we can see the change of seasons, and the fading of daylight, as something sombre this exhibition is uplifting, colourful and playful. In the darkest of times we can find joy to uplift our heart, helping us to be at one with the darkness.

Roscommon Arts Centre is open: Tuesday - Friday 10am - 5pm. Saturdays from 11am - 4pm. The gallery is also open on performance evenings.

Áras Éanna

Áras Éanna Ionad Ealaíne is the most westerly arts centre in Europe. Located on the small Gaeltacht island of Inis Oírr in County Galway, the centre offers artists the opportunity to develop their practice in a unique environment rich in culture and natural beauty. Situated in a former weaving factory, Áras Éanna is a multi-functioning arts centre that includes an artist’s studio space, theatre, galleries, and various spaces for workshops and classes. Open calls for artists in residence are normally advertised each August for residencies the following year, which generally last from two weeks to one month. Successful applicants usually receive return ferry transport, accommodation, studio space, and a stipend, determined during the selection process. Artists at all career stages are encouraged to apply.

aras-eanna.ie

The Burren College of Art Artist Residency programme generally invites applications from artists at all career stages, offering dedicated studio space and access to campus facilities. BCA offers two specialised residency options: Residency + offers studio time over a four-week period during the academic year (September – April); while the Burren Immersion 12-week residency offers independent studio time, advisory sessions, and the option to take undergraduate courses (without credit) during the semester. All residents can participate in public discussions, artist lectures, seminars, and exhibitions throughout the year, fostering engagement with the college community. Residency applications are accepted on a rolling basis throughout the year, and places are offered based on the availability of space.

burrencollege.ie

Formed in 1992, Artlink is based at the historical and picturesque location of Fort Dunree Military Museum, Buncrana, County Donegal, where it looks for imaginative ways to link artists to the local community. Artlink offers several funded residencies each year for artists based in Ireland or internationally. Artlink is currently participating in The International Atlantic Art Exchange, hosted by O’Brien Farm in Newfoundland, for Irish visual artists from the northwest of Ireland to undertake a four-week paid residency between June and September. In addition, the Harry Kerr Bursary offers annual bursaries of €5,000, providing support to deserving artists while fostering creativity, technical skill and artistic excellence in photography.

artlink.ie

Building on the successful pilot programme, Cow House Studios, in collaboration with The Mothership Project and Wexford County Council, is offering an annual Parenting Artist Residency. This two-week residency, scheduled for April 2025, supports parenting artists with dependants aged two to 12, providing the opportunity to focus on their creative work. Selected artists will receive a stipend of €500, accommodation, meals, and childcare from 10am to 5pm on weekdays. The residency aims to address the cultural gap experienced by artists who often curtail their practice while raising children, fostering community and collaboration. Applications are open until 15 December 2024, with successful candidates notified by 13 January 2025.

cowhousestudios.com

The Ballinglen Arts Foundation, a registered Irish charity, offers a unique Fellowship Programme, inviting both Irish and international artists to work in rural Ireland. Since 1992, Ballinglen has hosted artists from the US, Europe, and Asia in the coastal village of Ballycastle, County Mayo. Situated along the Wild Atlantic Way, Ballycastle offers artists a scenic landscape with rich history and wildlife. Unlike many typical retreats, Ballinglen allows artists to bring family or companions and live in cottages with dedicated studios. The foundation encourages interaction with the local community, believing it enhances creativity and human connection. After delays due to COVID-19, the foundation is now accepting applications for its residency programme.

ballinglenartsfoundation.org

Cill Rialaig village, founded around 1790 in Ballinskelligs, County Kerry, Ireland, was revitalised as part of a plan to support the Gaeltacht area. Dr Noelle Campbell Sharp established the Cill Rialaig Project, which offers a retreat for national and international artists, writers, and filmmakers. Since 1991, over 4,900 artists have visited the retreat, which includes seven studios and a communal house. The project provides free accommodation in self-catering studios, fostering creativity in an isolated, inspirational setting. Numerous artworks, inspired by the region, have been exhibited worldwide. The project is partially funded by government grants, but relies heavily on patrons and fundraising. It operates year-round, and regularly welcomes applications from artists interested in residencies.

cillrialaigartscentre.com

Situated in the Shandon area of Cork City, the Guesthouse Project is an artist-led initiative offering one to three-month residencies for international and Irish artists, including collaborative groups. Open to various disciplines – including visual arts, experimental film, sound, performance, and more – the residency programme promotes cross-disciplinary, experimental practices. Artists are provided with free accommodation in a private loft apartment and access to shared facilities, including workspaces, a kitchen, and dining areas. Project-based residencies (without accommodation) are also allocated on an ongoing basis. The programme encourages artists to engage with Cork’s creative community and explore innovative uses of the Guesthouse space. Applicants are usually responsible for travel, materials, and living expenses, with optional workspace available for an additional fee. theguesthouse.ie

Leitrim Sculpture Centre (est. 1997) hosts an extensive residency programme across a range of disciplines. LSC’s facilities include equipment for working with stone, glass, metal, ceramics and digital media. Exhibition Residencies (eight weeks) offer a €4,000 artist fee, accommodation, and access to facilities to support the development of new work for an exhibition at LSC. Technical Development Residencies (four to six weeks) include a €2,000 stipend and allow artists to experiment with new materials without exhibition requirements. Professional Development Residencies provide a base for artists, curators, or writers to explore ideas and receive technical training. PDR residencies are funded directly by the artist or another funding body, such as Local Authorities or the Arts Council (Professional Development, Agility, Bursary, or other award).

leitrimsculpturecentre.ie

The Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) in Dublin has been supporting contemporary visual art practices through onsite residencies since 1994. Open to both emerging and established artists, from across Ireland and internationally, the programme fosters artistic development, research, and dialogue in a variety of formats. Residency participants benefit from IMMA’s collection, exhibitions, and educational programmes, as well as the historical setting of The Royal Hospital Kilmainham. The residency offers opportunities for collaboration with fellow residents and access to Dublin’s vibrant cultural scene. Residents stay in the large, shared Flanker house, or in one of three self-catering coach houses, which include workspaces. There are regular open-calls, so it is advisable to sign up to IMMA’s residency mailing list. imma.ie

Tony O’Malley Residency

Situated in Callan, County Kilkenny, the Tony O’Malley Residency is an annual opportunity for an artist focused on painting, which is administered by the RHA School. Established by Jane O’Malley in memory of her late husband, Irish artist Tony O’Malley, the residency aims to provide support to contemporary artists and a nurturing environment for artistic creation. During his lifetime, Tony O’Malley was the recipient of subsidised studios and accommodation in St. Ives, Cornwall, and the couple never forgot the privilege of those decades. Offered annually for one year from late September, the residency grants the selected artist exclusive use of a house and studio for a nominal fee of €300 per month, plus utilities. This full-time residency is specifically designed for painters, as the studio is unsuitable for sculptors.

rhagallery.ie

Founded by Alannah Robbins, Interface is a studio and residency programme located in an old salmon hatchery in the Inagh Valley in Connemara. Interface offers opportunities for artists to explore intersections between scientific research and art in an area of outstanding natural beauty. The programme prioritises proposals that explore the intersection of art and science or respond to the unique environment. Residencies generally last two to four weeks. Artists receive studio space and accommodation but are responsible for their travel to and from Connemara, materials, and transportation of artworks. A car is necessary for travel between the studio and accommodation. Interface helps artists connect with the local community through meetings and talks. This residency is not suitable for children.

interfaceinagh.com

Located at Annaghmakerrig, Newbliss, County Monaghan, the Tyrone Guthrie Centre (est. 1981) is a residential workplace for artists of all disciplines. The centre fosters excellence and innovation in the arts by providing workspaces for accomplished professionals, including writers, musicians, choreographers, and visual artists. The centre invites applications year-round, and practitioners of all artforms are welcome to apply. Applicants should be recognised by peers and have a proven track record, such as publication for authors, exhibition histories for visual artists, and significant professional experience for musicians, composers, and designers. This ensures a high standard of artistic engagement and collaboration within the centre. Many local authorities offer Tyrone Guthrie residency awards to individual artists.

tyroneguthrie.ie

DR MARIANNE O’KANE BOAL CONSULTS THE SECTOR AND OFFERS ADVICE TO ARTISTS ABOUT SETTING UP COMMUNAL WORKSPACES.

ADVICE ON ESTABLISHING a communal workspace should be centred on the experience of the sector. For this article, I’ve combined research conducted in 2017 in Belfast, with interviews that I have since undertaken with communal workspaces and studio groups. These include Sample Studios, Cork (established in 2011), Backwater Artists Group, Cork (established in 1990), BKB Visual Arts Studio, Dublin (established in 2019), and spacecraft, Limerick (established in 2017). While each of these studios have developed their own ways of working, their common experience is centred on creating a supportive environment for practicing artists, through a spirit of collaboration.

In 2017, I worked with Northern Visions Television (NVTV), Belfast’s local TV service, to curate a film project with artist studios in Belfast. I conducted an artists’ panel with collectives that was filmed and broadcast.1 Our starting point was the Footfall report, produced by Joanne Laws with 126 Artist-Run Gallery in Galway in 2015, which describes the artist-led scene as a “pragmatic, ambitious and agile sector, which is based on the social capital of cooperative networks and motivated by an unwavering fidelity to artistic practice.”2 My own research further reinforces the capacity of artists to nimbly find solutions to a range of urgent issues – from insufficient funding and eviction at short notice, to the deterioration or maintenance of premises, and other organisational challenges. In these cases, collectives are motivated by a shared sense of responsibility to

respond swiftly and effectively.

From speaking to Belfast artists running studios, the two primary issues that emerged are centred on precarity of space and availability of funding. These issues inform much of what occurs in communal workspaces and their trajectories.3 Jennifer Trouton has been a member of Queen Street Studios for 27 years. The studio group was established in 1984 and has recently celebrated its 40th anniversary. Jennifer observes that “the fundamental needs for a studio group are affordability and security of tenure, and they are like hen’s teeth.” Over the years, with funding and tenancy agreements, it was necessary for QSS to become more business-like. Most studio groups I have spoken to have emphasised the importance of their constitution or company status, but each workspace finds its own approach.

The macro-context is important when establishing a communal workspace, and Aoibhie McCarthy of Sample Studios in Cork has emphasised that this should be done in partnership with local and governmental organisations. Equally, the micro-context of the workspace itself is fundamental to its operational success. As Emily Brennan of BKB Visual Arts Studio points out, everyone must have realistic expectations and a clear understanding of the amount of work required in setting up a space. Their primary challenge has been securing a lease on a building in Glasnevin in Dublin, but she sees that challenge as universal for artist groups: “Anything truly suitable is too expensive for an arts organisation. You need to be prepared to take up

a space that needs a lot of work.” According to Carey Long of spacecraft in Limerick, practicalities are important, particularly documentation of working processes to enable consistency, should any of the core artists running the space leave in the future.

Considering the challenges involved in establishing a communal workspace, it is interesting to observe the continuing motivation of artists to work in this way. Democratic ways of working are evident among the advantages outlined by Emily: “Decisions are always finalised by majority rules and that works for us. The pros of working as a collective far outweigh the cons.” As noted by Carey, “the main advantage for all studio members is having artists to talk through their work and this leads to a cross pollination of skills between members.”

Aoibhie reinforces the importance of conversation at Sample Studios: “The heart of the space is actually the kitchen, where the magic of collaboration can occur while the kettle boils.” Similarly, Elaine Coakley from Backwater Artists Group in Cork notes that: “Collectively, we have a broad range of skills, knowledge and expertise, a stronger voice, an existing peer learning environment and our endeavours are amplified as a collective.” According to Helen Carey, Director of Fire Station Artists’ Studios in Dublin, collectivity offers “broader support to address challenges, greater imagination to find solutions, and wide enjoyment of communal effort. There is also scope to work creatively together.”

Some studios emphasised the need for advocacy and welcomed interest and fur-

ther research in this area. If artists’ workspaces are advocated for and their voices heard, particularly in terms of the challenges they face, this helps build a case for support. Jennifer explains that “artist-led activity happens in Belfast out of necessity, as there isn’t sufficient funding. There is an element of burnout among members, and we should recognise the wider community of collectives, with old guard and new guard, as the younger generation is essential to inject fresh energy into the sector.”

Within studio groups, the integration of past and present members in long-standing and emerging collectives has a wider importance for the building and retention of knowledge, skills and experience. If this understanding is shared, it can ensure the establishment and endurance of successful workspaces into the future.

Dr Marianne O’Kane Boal is an art critic and curator based in Donegal. She has a PhD in Social Research from ATU Sligo.

1 Artist Studios in Belfast (2017) [Film with curator Marianne O’Kane Boal and Lombard Studios, Queen Street Studios and B Beyond] Northern Visions Television (nvtv.co.uk)

2 Joanne Laws, FOOTFALL: Articulating the Value of Artist Led Organisations in Ireland (Galway: 126 Artist-Run Gallery, 2015) (archive.org)

3 Artist Studios in Belfast (nvtv.co.uk)

MORROW

I CURRENTLY SIT on a studio research and policy group, convened by Belfast City Council in response to the buildings crisis in our sub-sector. The Community Asset Transfer (CAT) process, and schemes such as Section 76 are often mentioned, but somewhat obliquely, since nobody really knows what they are or how to access them.1 To help demystify the process, I consulted Margaret Craig, Senior Programme Coordinator at Development Trusts Northern Ireland (DTNI), the organisation that supports the CAT process; and Alison Gordon, Co-founder of Open House Bangor and Development Director of The Court House, the first arts organisation to complete a CAT in Northern Ireland in 2022.

What is CAT?

Community Asset Transfer (CAT) is the process of transferring publicly-owned land and buildings from public authorities to community organisations. This process is managed by DTNI, who work with “local communities, government, and the voluntary sector to promote policy reform and innovative programmes that advance community ownership, participation, rights, and local economic development”(dtni.org.uk).

DTNI offers annual membership for £75, but joining their mailing list – which lists D1s (buildings and land available for disposal) – is open to everyone. Their website features an asset register, and membership facilitates networking among groups with similar goals.

CAT was established in 2014 but is still relatively untested across the arts sector in Northern Ireland. There are huge variances in the size, scale, remit, finances and location of arts organisations; so much of what made The Court House’s success isn’t applicable across artforms.2 DTNI is explicit about the challenges of CAT, including the fact that organisations need adequate financial resources, and that social finance, skills development, and legislative support would certainly help.

Once a public sector asset is added to the D1 list, third sector organisations can submit an Expression of Interest (EoI) to DTNI, thereby entering the internal public sector market. The D1 list is circulated to government departments, local authorities, and third sector entities, including NGOs, non-profit organisations, charities, voluntary groups, and cooperatives.

Each asset is assessed by Land and Property Services (LPS), which advises the disposing body on the appropriate capital receipt (the cost of the asset) to seek for the public purse. Interested parties must find ways to raise the necessary funds. If a group or consortium cannot secure the required amount and all options to retain the asset within the public estate have been explored, the disposing body may then market the asset to raise the capital receipt. As soon as a capital receipt has been set, those who can’t afford that price quickly fall out of the process. Any third sector organisation still in the mix now must get a sponsoring body on board with Compulsory Purchase Powers (CPP).3 By DTNI’s own admission, this is where things get a little complex for everyone and the process of acquisition slows down, or if a sponsoring body cannot be secured, the transfer cannot take place, and the asset now can go to the market.

DTNI have all sorts of networking capabilities. For example, if we identify an asset that looks promising, but we have no idea who owns it or how to reach them, they can try to find the owners, whether public or private. If public (such as a government department or a local authority), DTNI can open the conversation with the asset owner. The Department for Communities provides DTNI with a small budget to support community organisations who have expressed an interest in a D1 or who have a desire for ownership of an asset. The funding can be used to bring in, for example, quantity surveyors to do condition reports, for architect drawings, or to get the property independently valued. They can also advise on other funders who might be able to support capital costs or pre-capital feasibility investigations, such as the Architectural Heritage Fund (ahfund.org.uk).

CATs are not zero-cost. Assets are valued by LPS, and location and state of repair are factored into the valuation. However, to be called an asset at the time of transfer is arguable, as many are derelict or heritage buildings that require substantial investment and renovation. Margaret tells me that the nine-month CAT process outlined on the DTNI website is the exception, not the rule. Yet some organisations, with persistence, can find themselves in the right place at the right time.

Bring everyone you know together, especially, as Alison says, if you think they might be able to answer questions that you cannot. This includes, from an operational standpoint, board members, especially those with legal, financial, or property expertise. You should draw on your artistic community, from individual artists and peer organisations, to (in the case of Court House) a roster of artist booking agents and representatives, who can validate your ongoing programming plans. Also vital are local businesspeople who understand the value of the arts, not just in terms of tourism but who recognise the increased vibrancy of an area; the local community, who are personally engaged, who live or work in the area, and want greater cultural and/ or entertainment offerings in their localities; funders, who know and can speak to your track record; and civil servants and politicians, whose backing is crucial. It also helps if you can tie into a local authority strategy

around regeneration. All of this support is necessary to demonstrate that the community benefit of your plan outweighs the value of the asset.

Building on DTNI’s network support, Margaret tells me that collectives, umbrella organisations, or those with cooperative structures (and the robust partnership agreements that usually accompany them) can do better in the CAT process than those who go it alone, as the risk is spread. Gather all relevant data – audience figures, funder reports, box office statistics (if applicable), social media numbers, employment stats, programmes, memberships, risk assessments and health and safety experience. Alison advises not to start something new while finding a premises; only pursue a CAT if you are not changing your business model.

Within the aforementioned studio research and policy group, we are exploring a couple of avenues. Our first plan is to liaise between Belfast City Council’s Culture team and another council department – most likely within planning – who can help us navigate these policies and procedures. Whilst achievable, this process will undoubtedly be time-consuming, and more Belfast organisations stand to lose their current buildings in the meantime.

With thanks to Margaret Craig (Development Trusts Northern Ireland), Alison Gordon (Open House and Court House, Bangor), Irene Fitzgerald (QSS), Gail Prentice (Flax Art Studios), Brona Whittaker (Arts & Business NI), Shauna McGowan (Belfast City Council), and Joanne Laws (Visual Artists’ News Sheet) for their (directly and indirectly referenced) contributions to this article.

Jane Morrow is a curator, writer, researcher, advocate, and Co-Director of PS2. pssquared.org

1 Section 76 is a planning agreement which ringfences a proportion within new developments for model clauses, such as affordable housing and green travel measures (belfastcity.gov.uk)

2 Organisations like Derry’s Nerve Centre and In Your Space Circus have successfully secured permanent buildings, through either grant aid or Community Ownership. There are other examples in the Strategic Investment Board’s 2024 report, Adaptive Reuse of Existing Assets (dtni.org.uk)

3 Department of Finance’s description of how Land and Property Services provide valuation services (finance-ni.gov.uk)

AOIBHEANN GREENAN OUTLINES KEY PRINCIPLES TO HELP CULTIVATE A MORE JOYFUL AND SUSTAINABLE PRACTICE.

THROUGH MY CONVERSATIONS with artists and creative freelancers, I’ve observed that burnout is becoming an increasingly common experience. We face unique challenges, such as relentless pressure to innovate, meet client demands, and stay financially afloat in an unpredictable, competitive market. These factors often make burnout harder to recognise when we’re caught up in the daily grind. However, identifying the symptoms early is vital for safeguarding both your wellbeing and your creative spark.

One of the most telling signs of burnout is persistent exhaustion – the kind that no amount of sleep seems to cure. You wake up feeling physically and emotionally drained, and fatigue follows you throughout the day. Another key indicator is emotional numbness or detachment from your work. What once was a source of enjoyment now feels burdensome. For artists, whose work thrives on emotional engagement, this disconnect can be especially debilitating. Preventing burnout requires a holistic approach that addresses both the external pressures of freelance life and the internal forces pushing you toward exhaustion. I’d like to offer four simple principles that can help you cultivate a more joyful and sustainable creative practice.

1. Prioritise Rest: It may seem annoyingly obvious, but prioritising rest is often one of the most difficult and counterintuitive commitments to uphold – especially when deadlines are looming! However, intentionally incorporating downtime into your schedule is essential for maintaining longterm creativity and mental health. Deep rest extends beyond simply getting enough sleep; it involves giving yourself the space to completely unplug. Regularly scheduling 15-minute breaks for activities like aimless walking, daydreaming, or meditation, enables your nervous system to shift from the overstimulated ‘fight-or-flight’ mode (sympathetic) into the parasympathetic state, where true recovery can take place. By nurturing a relaxed, receptive state, you create the ideal conditions for inspiration and creativity to naturally reemerge. We’ve all experienced how stepping away for brief intervals allows us to return to our work with fresh perspectives and discover new connections. In this way, rest becomes the foundation for every aspect of your creative practice.

2. Examine Your Motivations: Creative burnout often stems from deep-rooted psychological patterns, particularly the need for external validation. Unfortunately, this dynamic can lead to an unconscious cycle of perfectionism and overwork. It’s essential to routinely examine your underlying motivations. Practices like journaling, coaching, or therapy can guide you in asking important questions: Why am I pushing myself so hard? What am I trying to prove, and to whom? This self-awareness enables you to

shift your practice from one driven by external validation to one fuelled by authentic curiosity and personal fulfilment. As you detach your self-worth from achievement and validation, new creative avenues will often emerge – ones that a narrow focus may have previously obscured.

3. Embrace Play: Freelancers often face an intense focus on outcomes, which can stifle the joy and creativity that originally drew you to your craft. A powerful way to prevent burnout is to reconnect with playfulness in your process. Set aside time for unstructured experimentation, free from deadlines and the expectations of others. Ask yourself: What materials, colours, motifs, sounds, or phrases naturally excite me? What activities did I love as a child? Start collecting items and ideas that spark your interest, using a simple filter: Does this make me feel contracted or expansive? Follow the path of expansion and pay attention to how seemingly unrelated elements begin to connect in unexpected ways. As you let go of rigid expectations, you may experience surprising breakthroughs. Neuroscience supports this idea; dopamine, the brain’s ‘reward’ neurotransmitter, is triggered by curiosity and play, helping you enter more relaxed, open states conducive to problem-solving and creative flow.

4. Set Boundaries: Freelancing often blurs the lines between work and personal life that can lead to overwork and emotional exhaustion. Therefore, setting clear boundaries is essential for protecting your mental and physical wellbeing. This requires being intentional about the projects you take on and ensuring they align with your energy levels and personal values. One effective tool I use with my coaching clients is a scoring system based on non-negotiable criteria that each project must meet. This approach helps to ensure that you’re only taking on work that resonates with you, thereby avoiding misaligned projects that could lead to burnout. Additionally, it’s crucial to establish firm work hours – easier said than done – and make time for activities and relationships that nurture you outside of work.

If you’re feeling burned out, view it as a signal that your creative practice needs to evolve. The phrase “work smarter, not harder” is especially relevant here. The key is to cultivate a practice that nurtures both your creativity and wellbeing. Remember, if you’re in this for the long haul, there’s no need to rush to the top. The quality of your work will always reflect the energy and intention behind it. By honouring your physical and emotional health, you set the stage for a more fulfilling and sustainable career.

Aoibheann Greenan is an Irish artist founder of Rodeo Oracle, a coaching and mentoring service for artists. rodeooracle.com

FOR HER FIFTH COLUMN IN THE SERIES, LIAN BELL SHOWS HOW TAKING A GAP DAY CAN CHANGE THE WORLD.

FOR THE PAST year, I have used this VAN column to unpick aspects of my interest in the labour of artmaking – from positioning walking as creative practice, or questioning the pace of how we work, to how coaching can strengthen artists’ agency, and the implications of travelling for work without flying. Pinpointing where this interest in artistic labour coalesced, it is probably with my experience of creating Gap Day.

Ten years ago, Mermaid Arts Centre in Bray asked me to invent an artist support programme. At the time, a relevant funding scheme was offered through the Arts Council’s Theatre silo, so our focus was freelance theatre artists. I began thinking of what I needed myself as an overworked freelancer whose ‘day jobs’ were leeching energy from my artistic practice. Not much, I thought. Just a day in a room on my own to go through old notebooks, pick up half-forgotten threads of thought, and remember why I wanted to make art to begin with.

My proposal was simple: pay artists for a day or two to do whatever it is they need to do and give them a room to do it in. With the input of Niamh O’Donnell (Mermaid’s then director, and a truly generous champion of artists) a plan formed. Remove the guilt of taking time ‘off’ to be creative by paying people properly. Find a room in an arts centre, local to wherever they live, so that rural artists are as supported as urban ones. Ask the centre’s director to meet them for a cup of tea, facilitating local informal connections. Provide a packed lunch for nourishment and hospitality. A pilot project ran in 2015 and was an instant success.

The application responses to that pilot shook me. Having previously been a reader for various open calls, I was habituated to the jazz-hands aspect of application-speak. I had written it many times myself. Look! I can do this! It’ll be great! I’ve done great stuff before! I can do it again! Gap Day applications were not that. The intentionally simple form asked why the artist needed a Gap Day, and the responses were painfully honest: Because I’m a full-time carer; I work multiple jobs; I’m a single parent; I have to wait until my housemates have gone to bed before I can use the kitchen table. It has become more common in recent years to hear about the working conditions of artists, but that was the first time I had seen it written so starkly. This was a narrative of people struggling against self-doubt, loneliness, overwork, and poverty.

As the world changed, and as my own interests in artistic labour evolved, we added more resources for participants. Funding to cover additional needs, including childcare, so people can get the full benefit of their Gap Days. Online group gatherings. One to one coaching sessions. Trips to national conferences and networking events. A little money for each participant to pay an ‘Artist Friend’ for a few hours of inspiring conver-

sation. Most recently we added facilitated walks that take place around the country to meet, think, and talk together. But all of these are optional; the anchor point of Gap Day continues to be paid time (currently €240 a day) in a room to do whatever the artist needs to do. Even just one Gap Day can mean a lot: a sense of validation; a foot in the door of an arts organisation; respite from creative loneliness; or simply a bit of money. Each artist themselves chooses where they want to take their Gap Days and we arrange it for them. Organisations have also grown to value the programme as hosts; it can be an introduction to people they may not know, or a progression of an existing relationship. And for those organisations without much direct contact with the artmaking process, having an artist working in the building can be a buzz.

However, Gap Day’s success is bittersweet. Its disproportionately positive impact is only due to the fact that artists are so under-served and under-appreciated. After ten years and having supported over 300 artists across the island, Gap Day has become a valued sticking plaster in what is a barely functioning system of subsidised theatre-making in Ireland. Though it offers a moment for artists to catch their breath and keep going, I sometimes fear we are giving false hope when the greater system may not prove able to support them. I can only trust that these small moments of respite may give artists the energy to confront these broken systems they have to work within.

I value the work that looks like nothing. The walking, the staring into space, the conversations that meander. The imperative to take time in my own practice, to rest, and turn away from digital devices is something I am still learning to do. By creating structures for others to do so, through interventions such as Gap Day, I offer the permission for all of us to approach our work differently. Through Gap Day, hundreds of moments of respite and collegiality are woven together with the aim of forming a new way of working, and a new template for our collective artistic labour.

Lian Bell is an artist and arts manager based in Dublin. lianbell.com

BASED BETWEEN BERLIN and Ireland for the last four years, curator and researcher Nóra Ó Murchú’s practice examines digital culture as well as the effects of technological developments on social systems. During her time as artistic director of transmediale festival in Berlin, Ó Murchú commissioned work from a number of international as well as Irish artists, including Bassam Issa Al-Sabah, Jennifer Mehigan, Jennifer Walshe, and Alan Butler, among many others. As the first female director in the festival’s 37-year history, Ó Murchú’s programming aimed to centre previously absent voices, specifically in relation to decoloniality. We spoke about building a career abroad, her curatorial practice, and her experience of engaging with the Irish art scene from Berlin.

Aoife Donnellan: Having worked extensively internationally, both as a curator and a researcher, what has your experience been in building your career abroad?

Nóra Ó Murchú: With the topics that I work on in my own research, it’s been primarily bigger countries that had a larger portion of people interested in tech, but I do think that’s really changed. I was based in Ireland until 2020, so had a few different things that I was doing. For example, when I was working on my PhD, I started a digital art festival in Ireland and was building up my network through inviting people and attending events. Then, as I began to have a larger network and meet different people, I started getting invited to curate different things. Simultaneously, I was also working as an academic at the University of Limerick. I was writing about digital art and technology, and I was publishing at the same time as attending conferences and art events. I have tried to grow my practice through those approaches.

AD: Your work examines how people engage with and build socio-technical systems. Does it benefit particularly from international collaboration?

NoM: Yes, of course, but that wasn’t the main priority. When I first started out, technology wasn’t something that a lot of artists in Ireland, or artists generally, were exploring. Over time, what we have seen is that more and more artists have started to occupy and work with the medium and format. I never studied art – I come from a technical engineering background. However, when I was in University of Limerick doing my Masters, I got very into research on digital art, and then realised it was something I wanted to investigate. I was always interested in curation, and my PhD looked at curatorial methods in the context of digital art.

AD: While you were artistic director at transmediale, you commissioned a number of Irish artists. How did you find the process of collaborating with Irish artists from abroad?

NoM: One of the main things I wanted to do, while I was there, was to highlight Irish artists who are working in this space. The previous directors were all male, and they were all either German or Swedish. The last director, for example, presented a lot of American and British artists and researchers at the festival. Going into transmediale, I knew I was really interested in decolonial practices; that was one of the things I was determined to show and exhibit, by inviting people from those contexts and with those types of practices into the festival. I also wanted to push away from the very screen-heavy, tech-heavy emphasis on what technical practices or digital art can and should be. I was very interested in the poetics of software, sculpture and materiality. It was really important that the artists I selected were also thinking through some of these lenses as well. Coming from an Irish context, I wanted to highlight that – it’s the place where a lot of my thinking originates, about what decolonial technology is and how it has been formulated. I’m a

by-product of a geographical space, of history, of memory and of lived experiences, and so I wanted to ensure that Irish artists were part of that discourse.

AD: What was your curatorial approach to these collaborations?

NoM: I had this unspoken agenda to include Irish artists while I was there, and then I also shared my research with them as I was progressing. For example, the work I was developing that resulted in a commission with Alan Butler in 2023 – I would share that research with him, and we would have many conversations back and forth about the same themes, ideas and topics. This dialogue would inform my writing or thinking and likewise his. I generally try to develop very reciprocal relationships with artists. When it comes to commissioning work, I have different relationships with different artists. My objective is to support artists in what they’re making, and then I would have as many conversations as they would like, in order to talk about the commission or the work.

AD: Finally, what are you working on at the minute?

NoM: Right now, I’m focused on a few dif-

ferent projects. I’m working with Aksioma Institute for Contemporary Art (aksioma. org) which is a project space in Lithuania, to look at my concept of unusable politics. I will be doing a piece of writing, defining what this is, and we’re going to build a small discursive and exhibition programme that will stem from this research. A lot of it is raising questions about what software is, how it has evolved, and the impedances to new collective forms of action at various levels in society. How do you reorganise or rethink what collective action is online, as increasingly, technology encroaches on your day-to-day? It’s thinking about those things.

Aoife Donnellan is a researcher, art writer, and curator from Limerick, based between London and Berlin. @aoife_donnellan_

Nóra Ó Murchú is a curator and researcher who examines the intersections between fields of art, design, software studies, and politics. noraomurchu.com

THE DAY AFTER I completed my MFA exhibition at NCAD in Dublin in 2012, I left Ireland – and I haven’t lived there full-time since. It wasn’t a decision I made lightly. Dublin is in my bones, as I was born and raised in the Liberties. The laughter of my friends, the warmth of family, the mingling scents of fresh fish on Meath Street with the earthy tang of hops from the Guinness factory – all of it fills me with a nostalgia and affection unlike anything else I know.

But at that time, the Irish art scene was a very different landscape to today. Studio spaces were nearly impossible to find, my work wasn’t being embraced, there was limited funding opportunities, and almost everyone I knew was flat broke. I was barely scraping by myself. The idea of sustaining an artistic practice in Dublin, while juggling non-existent exhibition opportunities, felt like an impossibility. Many of my fellow artists and friends decided to tough it out and stay, but for me, leaving became not just an option – it felt absolutely necessary.

Every day, without fail, the artist Joseph Noonan-Ganley would call me, brimming with enthusiasm, eager to concoct a plan to lure me to London. He and another other good friend, Sam Keogh, both immersed in their MFAs at Goldsmiths (alongside Elaine Reynolds and Eoghan Ryan at the time), were relentless in their efforts to convince me to join them. Eventually, fate intervened: on the very same day, I landed work with the artist Tino Sehgal and secured a residency in the Tate learning department. Yet, despite juggling these two opportunities, which soon grew to eight different jobs, I could barely scrape by in London. It was only through the camaraderie of my Irish friends, living together in a cramped flat, that we managed to ‘make it work.’ This became my Irish arts scene.

In response to the question of how the Irish diaspora can participate in the Irish visual arts scene – a provocation implying that the Irish diaspora bears a certain responsibility to engage with the Irish art scene, without fully considering the reasons why an artist might find themselves part of that diaspora in the first place – Joseph sheds some light on the complexities of that time, offering a glimpse into the dynamic challenges we faced: “The Irish visual arts scene is wherever Irish artists are working. You do not lose your Irishness when stepping over a national boundary. When I moved to England, I became more Irish. I had to rely on friends more, who were mostly Irish, for support: making bunkbeds, sharing rooms in flats, cooking together, making shows and publications. This intensified our bonds, which to others was seen as an intensification of Irishness. We’d get English people calling us the ‘Irish Mafia’,

which is a symptom of colonialism, the conflation of being Irish with something to be scared of; something criminal and underhand – a threat to English control.”

Participation isn’t always something that can be seen or outwardly performed. Much of the support we, as artists, receive exists in the unseen – the quiet, unspoken gestures that often go unnoticed, yet are vital all the same. This kind of support operates beneath the surface, and it’s rarely recognised for what it truly is, though its impact is no less profound. Oisín Byrne, who also lives in London, told me: ‘I’m cautious of defining participation in any universal or goal-based way, or even in terms of visible outputs. It’s more intimate and developmental than that. We participate through late-night phone conversations, through copyediting each other’s texts, through travelling, when possible, to see each other’s shows – through friendship, support and interest in each other’s work. Participation is broad, fluid and indefinite, and sometimes less visible or public.”

Avril Coroon moved to London in 2017, also to attend the Goldsmiths MFA. Having just recently moved to Amsterdam to

attend the Rijksacademie programme she told me: “My inclusion, when it comes around, is possible by access to facilities and structures, jobs and housing abroad. I participate in an Irish art scene partly because I am away. Moreover, I think if an art scene refers to a community and collective environment, we create it by facilitating each other wherever. Attending friends’ exhibitions is one thing, but what feels more ‘Irish’ in terms of chance encounters in a widening and quality scene has been participating in Hmn – a quarterly, London-based performance event that facilitates live testing of ideas, co-organised since 2015 by Irish artist Anne Tallentire and art writer Chris Fite-Wassilak. Frequently, and thankfully not exclusively, Irish artists contribute, forming a significant part of the audience that shares feedback and experience post events. Similarly, this year on a residency at the Centre Culturel Irlandais in Paris, I engaged in a swell of exchanges with Irish artists of all disciplines. The Irish art scene doesn’t exist exclusively on physical land, struggling to make both work and rent, or within its galleries, but where there’s tables with good cheap wine and fresh bread.”

Leaving Ireland sharpened my awareness of the subtle class dynamics and broad assumptions about community within the Irish arts scene – forces that continue to unfold even now. At times, it seemed my practice was defined solely by the fact that I was in London, as if my geographic location mediated how I was perceived as an artist. Paradoxically, it was in London that I felt more connected to the Irish arts community than I ever did while living in Ireland. Yet, that sense of belonging didn’t stem from any shallow or sentimental nationalism. Instead, it emerged from relationships forged on much deeper, more resilient grounds – bonds built on shared values and experiences, far stronger than the flimsy foundations of national identity.

Dr Frank Wasser is an artist and writer based in Vienna and London. He teaches on the BA in Fine Art in Studio Practice and Critical Studies at Goldsmiths, University of London. Wasser completed his DPhil at the University of Oxford in June 2024. frankwasser.info

DR FIONA WHELAN AND JOHN CONWAY OUTLINE THEIR ONGOING COLLABORATION AND PUBLIC ARTWORK FUNDED BY THE ARTS COUNCIL AND 221+ PATIENT SUPPORT GROUP.

THE FOREST THAT won’t forget is a national public artwork, dedicated to women and families across Ireland affected by the failures of the CervicalCheck Screening Programme. A 16-acre site in County Clare, this artwork is presented as a living, breathing anti-monument that publicly acknowledges a major historic injustice in women’s healthcare. It emerges from our ongoing collaboration with 221+ Patient Support Group,1 and a further partnership with Hometree.2 To date, the project has been funded by 221+ and the Arts Council (via an Arts Participation Project Award) and supported by the National Museum of Ireland (NMI) and the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA), where it was launched in September 2024.

In 2021, we were approached separately by 221+ Manager, Ceara Martyn, regarding a commission to memorialise the various losses, experienced as a result of the CervicalCheck failure. While we hadn’t worked together before, we found a shared commitment to investing in relationships and processes that recognised the knowledge and lived experiences of 221+ members and positioned us as active listeners. As such, we both advocated for a process that valued ‘not knowing’ what would be created, nurturing a collective process of engagement and idea development.

From late 2021 to 2024, we developed a series of engagements with 221+ members at regional gatherings in the NMI at Collins Barracks in Dublin, The Model in Sligo, and conference venues in Cork, Athlone and Limerick. Our ambition was to nurture connectivity and solidarity between members, to explore and test appropriate art forms, and to create the conditions for listening to the complexity of lived experiences. As artists, we were listening out for, and co-developing ideas towards, the potential of suitable creative cultural responses.

Simultaneously, we worked with a core group of five 221+ members – Lyn Fenton, Elizabeth Byrne, Wendy Stringer, Nicola O’Sullivan, and Carla Duggan. We would meet regularly via Zoom to test and devise ideas, which were expanded and scaled to engage the wider membership at the in-person regional gatherings. This process was further supported by our busy WhatsApp group which became a repository for ideas and photographs. Keen not to be extractive in our approach, we regularly demonstrated our acts of listening by collating and presenting back to members the textual and visual material we were gathering. Emerging from this nationwide collaborative process, a range of artworks, artifacts, and artistic research emerged, intended to publicly mark and communicate this major injustice of our time.

Acutely conscious of the significance of this commission, from the outset we created a structure to invite numerous advisors to support us, including Create, the national development agency for collaborative arts. To coincide with 221+ regional gatherings, we also built connections to key cultural venues nationally to create diverse and memorable experiences. The immense contemporary and historical importance of the context of this project led us to approach IMMA and NMI, who agreed to be national supporters of the project. And most significantly, Hometree (and their Development Lead, Ray Ó Foghlú) became a vital partner as the project developed. The forest that won’t forget is intended to function as a physical and metaphorical place of unity, care and resistance – a place that recognises the truth and experiences of those affected and commits to never forgetting. We are now in the process of securing the land and working to source further financial support to develop infrastructure on the land to make it accessible to 221+ members, guests and publics into the future. Beyond that, we envision programming further artistic projects on the land at the intersection of arts, women’s healthcare, ecology and education. Our ambition is that The forest that won’t forget can be held in perpetuity as a place for remembering the past, a place for imagining the future, a place for current and future generations, and a place with an eternal legacy that will outlive us all.

John Conway is a visual artist working extensively in complex health and community contexts. Dr Fiona Whelan is an artist, writer and Programme Leader of the MA Art and Social Action at NCAD. The forest that won’t forget was launched on 11 September 2024 at IMMA. theforestthatwontforget.ie

1 The 221+ Patient Support Group was established in July 2018 to provide information, advice, and support to the women and families directly affected by failures in the CervicalCheck Screening Programme that came to light following Vicky Phelan’s court case in April 2018. (221plus.ie)

2 Hometree is a nature restoration charity, based in the west of Ireland, working to establish and restore resilient habitats, focusing on native temperate rainforests. (hometree.ie)

THE KINSHIP PROJECT, like the concept it honours, attempts to expand the bounds of social art practice beyond human relationships to include the wider community of life in reciprocal, ethical connections. This durational artwork is situated in Tramore Valley Park – a 170-acre plot of land that, from 1964 to 2009, was used as a municipal landfill for Cork city. The area first opened up as a city park in 2015 before fully opening to the public in 2019. It’s a rich and complex public site that, in its own way, archives the excess of human intervention and consumption. Older Cork residents, who used to send their waste to ‘de dump’, walk over their own refuse histories on a stroll through the park. Either subconsciously or consciously, being in the park, with its ghostly reminders of the past, prompts us to confront our own actions, biases, and role in damaging habitats.

As a public space, Tramore Valley Park is managed by Cork City Council, who are engineering the substructure to support a new biodiverse habitat on top of three million tonnes of historical city waste. In her survey of ecological approaches to climate change and conservation, Emma Marris argues that many ecosystems are heavily altered by human activities and our approach to conservation should adapt to include concrete cities, brownfield, or toxic wastelands.1 For some, the involvement of artists commissioned to undertake a public art project which focuses on climate change in a remediated landfill site, may appear as greenwashing or ‘art washing’ damaged ecosystems. However, this view oversimplifies a highly complex situation that intersects a diverse array of interests, from local authorities to community leaders, multiple

life forms, scientists, and engineers, and from people who occupy the park on a daily basis to national policymakers.

At play in the heart of KinShip are processes of creative and dialogical enquiry, and a broad interdisciplinary and collaborative effort to reshape thinking and decolonise our relationship with nature. One of the calls to action Donna Haraway makes in her writing is “staying with the trouble.” She encourages us to resist the temptation to retreat or disengage in the face of environmental crises. Instead, she calls for active participation and collective efforts to mitigate the damage, restore ecological balance, and build sustainable futures.2 This means acknowledging the complexity of the issues at hand and working within that complexity.

In late 2021, in partnership with Cork City Council, we won funding to initiate the project through Creative Ireland’s first Creative Climate Action Fund open call. The project has since engaged with a combination of artists, community groups, engineers, scientists, ecologists, architects, and educational institutes amongst others to confront the legacy of this municipal landfill through overlapping strands of creative enquiry (creativeireland.gov.ie). At the outset, under the funding call, the preferred participation in the work was with the public, but this has proved to be an unhelpful silo.

Leading the process has meant holding continuous dialogue, working consistently with a core working group of representatives in the city, as well as others who enter for shorter periods, to create an emergent and generative public artwork that includes multiple voices, tests, and provocations.

To date, a diverse range of activities and events have taken place as part of the KinShip public programme, including: A talk by Cork Beekeepers Association about the importance of pollinators and their work as beekeepers; The (Waste) Fibre Flows Laboratory, an interdisciplinary space examining our complex relationships with waste material, led by artist Collette Lewis; ‘Laboratory of Land Flags’, an exhibition of co-created flags made by local communities during workshops with artist Chelsea Canavan; Eco-Kite Festival and kitemaking workshop, led by artists Amna Walayat and Kim-Ling Morris; and Staying With the Trouble – a one-day symposium to showcase the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and the input of diverse forms of knowledge in addressing rights of nature and climate action.

We undertook to archive and map all aspects of the KinShip project as this facet is often invisible to those who are outside of a social art process. This documentation, titled ‘The Midden Chronicles’, archives all meetings, conversations, agreements, contestations, small decisions, and larger initiatives. In 2023, drawing on this archive, we created an artefact, The Midden Chronicles Map – a five by eight-metre map highlighting a few short months of the archive. It acts as both an artwork and a momentary reflective snapshot of the multifaceted and complex inter-relational nature of social art practice. The map is an illustration and visual record of the collective and contributory nature of all aspects of the project, and the effort given by all contributors, collaborators, and partners (lennontaylor.ie).

While ‘The Midden Chronicles’ archive contains material and ephemera that doc-

ument the project, it also subtly reveals sets of values or assumptions, whether about the role of art, community involvement, or even practical discussions – for example, how much an artist or other should be paid. We may become aware through ongoing interactions that collaborators have brought different sets of values to the collaboration that weren’t initially obvious but could subsequently be addressed within the mechanisms of the project. These hidden economic, cultural, or ethical dynamics are revealed through the dialogical process, making the duration of the project not just about a specific context, but also about navigating the complexities of differing values, power relations, and goals within a collaborative framework.

The KinShip Art Project was initiated by LennonTaylor – a collaboration of Marilyn Lennon and Sean Taylor. The artists have worked together for over 15 years and were joint programme leaders of Ireland’s first MA programme in Social Practice and the Creative Environment (MA SPACE), which ran for ten years at Limerick School of Art and Design. In 2023 LennonTaylor received the Public Sector Award from Cork Environmental Forum for their work on the KinShip Project. lennontaylor.ie

1 Emma Marris, Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World (New York: Bloomsbury, 2011).

2 Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin In The Chthulucene (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016).

ANTHONY HAUGHEY OUTLINES HIS THREE-YEAR RESIDENCY AT THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF IRELAND AS PART OF THE GOVERNMENT’S DECADE OF CENTENARIES PROGRAMME.

I ARRIVED AT the National Museum of Ireland Collins Barracks in the summer of 2021, following a successful application to an open call for a socially engaged artist to engage with the museum collections and communities of interest. In the weeks before moving in, I was consulted on how a former military training building, designated as an artist studio, should be modified to suit my needs. I had conceived the studio as a learning lab where conversations, workshops, and durational art processes would lead to the co-creation of artworks with communities across Ireland, reflecting Joseph Beuys’ notion of ‘social sculpture’. A central proposition for my residency was to consider the National Museum of Ireland as a potential site of social transformation. The residency was an exciting opportunity to generate culturally diverse conversations resulting in artworks positioned within a historical-contemporary nexus, an intersection of colonial and postcolonial histories.

The museum contains seven million artefacts across four sites and repositories in Dublin, County Mayo, and elsewhere. This was an overwhelming and exciting prospect – but where to begin? One of the most important events in the early days of my residency was a filmed conversation with museum Director Lynn Scarff for Culture Night 2021, which set the tone for what would follow. Minutes into our conversation, it became clear that the museum was open to what artist and writer Gregory Sholette would later describe as ‘Troubling the Museum’ in his exhibition catalogue essay: “Who has access to the museum, who gets to control the narrative, all this must also be troubled.”1

The Museum’s collections reveal Ireland’s history, a colonised country entangled within the British Empire and its revolutionary struggle for independence, reflecting cultural identities and nationhood. Many museums are engaged in a slow process of mental decolonisation – the difficult task of evaluating collections, where many artefacts were inherited from colonial subjugation. During the residency, I attempted to work as closely as possible with the museums’ Keepers and Curators – though not always successfully, as there were many competing demands for museum staff. One of my most successful collaborations inside the museum was with the education department staff who became central in enabling me to navigate a complex web of museum departments and personalities. As an artist and non-staff member, I could mediate sensitive subjects difficult for a national museum, including tackling thorny issues such as the decolonisation of the collections.

My experience of working on earlier artist commissions reflecting the ‘Decade of Centenaries’ included a year-long residency at Limerick City Gallery in 2013, for a series of exhibitions commemorating the 1913 Lockout, as well as curating ‘Beyond the Pale: The Art of Revolution’, a major exhibition commemorating the 1916 Rising for Highlanes Gallery. These earlier projects revealed that acts of commemoration “tell us more about the society ‘remem-

bering’ than what is actually being remembered.”2 Excavating histories is a recurring motif in my practice. According to philosopher Walter Benjamin: “Articulating the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it was’ (Ranke). It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up in a moment of danger.”3 Our moment of danger in Ireland and elsewhere is populism and the rise of the far right.

Near the end of my residency, I was invited by Lynn Scarff and the museum team to produce an exhibition in the NMI Riding School, Collins Barracks, which was curated by Maolíosa Boyle and Jonathan Cummins. The outcome, ‘we make our own histories’, was a series of installations presenting artworks produced through durational, socially engaged art processes with more than five hundred collaborators and participants. Although we had significant resources for the exhibition, it was a huge challenge to produce a contemporary art installation in a historical heritage space. The exhibition invited visitors to speculate on a future egalitarian republic through: a young people’s assembly and manifesto; a dress designed to generate transcultural dialogical encounters between the museum collection and audiences; and a short film asserting postcolonial narratives entangled in the museum ethnographic collections. The culmination of my residency will be the accession of several co-produced artworks and archival material into the museum’s permanent collection. Having established an artist studio in the heart of the museum, it is my hope that the National Museum of Ireland will host further artist residencies.

Anthony Haughey is an artist and lecturer in TU Dublin, where he supervises practice-based PhDs. anthonyhaughey.com

Anthony Haughey’s residency was funded by the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Sport, and Media to mark the latter years of the Decade of Centenaries, in the context of a changing Ireland, 100 years after the formation of the state. ‘We make our own histories’ was presented from 28 February to 5 August 2024 at the National Museum of Ireland, Collins Barracks. museum.ie

1 Gregory Sholette interview with Anthony Haughey (12 December 2023) cited in Gregory Sholette, ‘Troubling the Museum: Anthony Haughey’s Archival Obstinacy,’ we make our own histories, (Dublin: National Museum of Ireland, 2024) p27.

2 Dominic Bryan, Mike Cronin, Tina O’Toole, and Catriona Pennell, ‘Ireland’s Decade of Commemorations: A Roundtable,’ New Hibernian Review / Iris Éireannach Nua, Vol. 17, No. 3, Autumn 2013, pp.6386.

3 Walter Benjamin, ‘Thesis on the Philosophy of History VI,’ in Walter Benjamin and Peter Demetz (Ed.), Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings (New York: Schocken, 1999; originally published by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978).

ROISIN AGNEW INTERVIEWS VIVIENNE GRIFFIN ABOUT THEIR RECENT EXHIBITION AT BUREAU GALLERY NEW YORK SUPPORTED BY CULTURE IRELAND.

FOR VIVIENNE GRIFFIN, Ireland’s susceptibility to extractivist uses of technology can be traced back to its Catholic roots. “I realise I’m sitting here wearing this giant fucking cross,” they laugh, “but I do believe that. Technology is entering the last frontier – our psyche, a colonisation of the mind, your spirit or your soul. I think in Ireland we’re vulnerable to these things.” The act of ‘profanation’ is one way to think through Griffin’s sprawling ‘anti-disciplinary’ practice, one that in recent years has gravitated towards sonic works that pair AI and coding with motorised harps and national-religious iconography. Central to it, is a movement between registers, a “passage from the sacred to the profane by means of an entirely inappropriate use (or, rather, reuse) of the sacred: namely play,” as Giorgio Agamben defines it. But when this passage from the sacred to the profane arguably involves the tools of your own self-dispossession, what then?

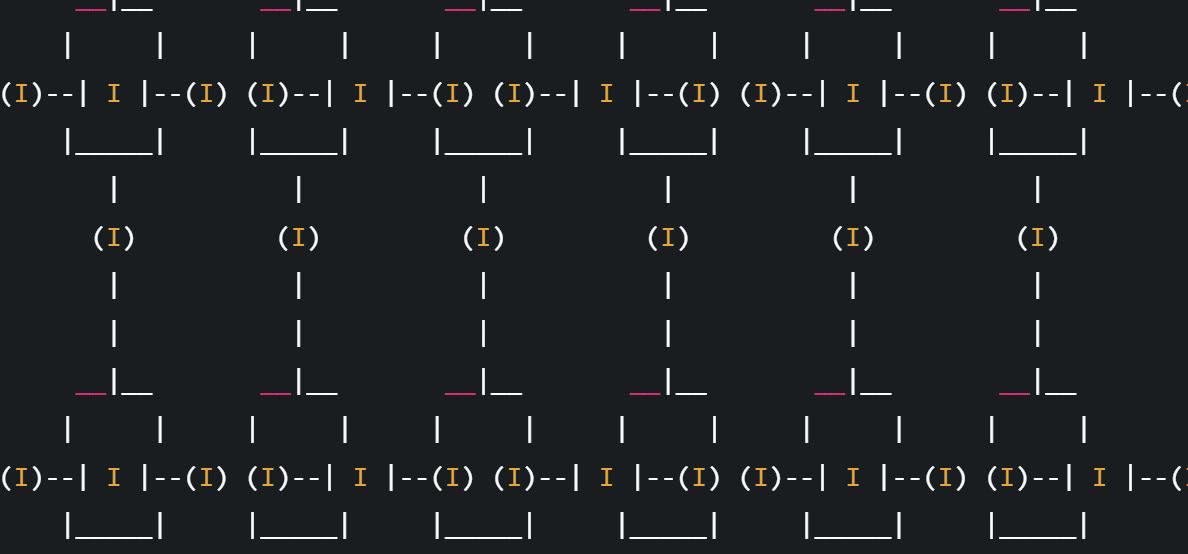

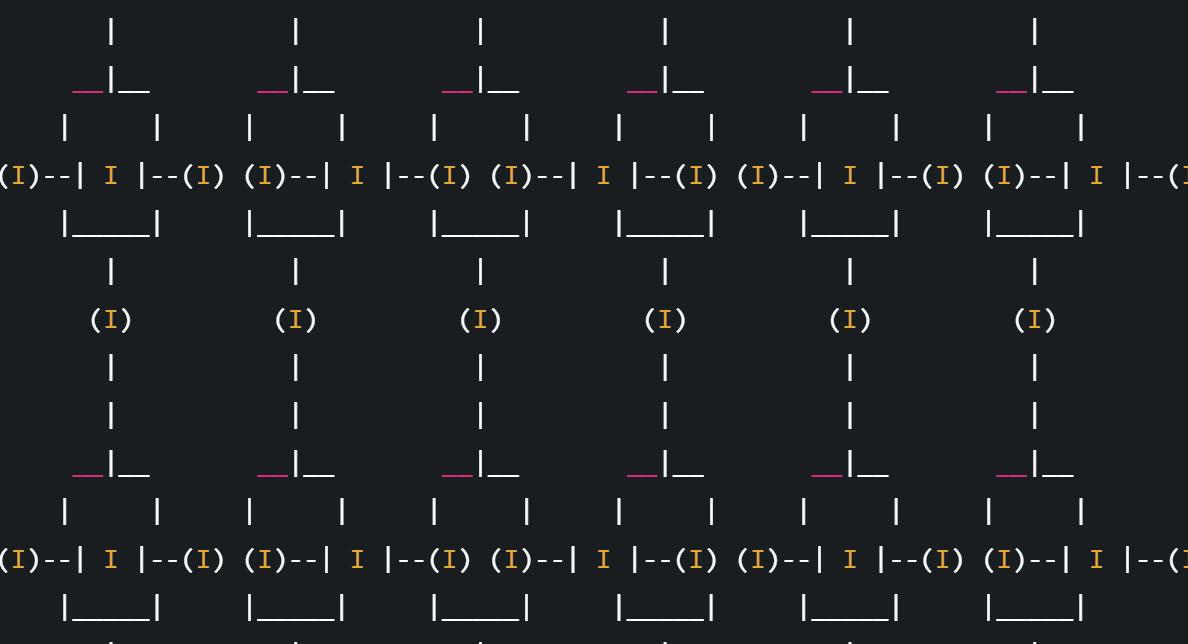

Play and its derivatives are conceived of by Griffin as part of the importance of the artist-as-beginner, pointing to Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind (a 1970 book of teachings by Sōtō Zen monk, Shunryu Suzuki) as a recurring influence. “The minute you start becoming an expert, you start narrowing and reducing the possibilities, whilst the beginner is always open,” Griffin says. It’s unsurprising, then, that when Griffin was offered the opportunity to collaborate with a researcher at the Turing Institute as part of their current residency at Somerset House Studios, they saw another opportunity to begin from the beginning. “I was learning about algorithmic processes, but I was really interested in them with regard interpersonal and social issues,” Griffin says. Collaborating with researcher Cari Hyde-Vaamonde, a former lawyer and current researcher in algorithmic governance

and the carceral system, Griffin began to “build a visual world and visual metaphors that [Hyde-Vaamonde] uses in judicial/ judge decision-making contexts.” The visualisation came out of Hyde-Vaamonde’s perceived need to make her research legible and counter a type of jadedness around algorithmic bias in relation to recidivism (the predicted likelihood of re-offending) and the main algorithm used for this calculation in the American carceral system, Compass. “I got stuck at one point; it’s not like my other work,” Griffin admits. “Direct political work – there’s no kind of other ‘read’ you can have on it.”

Understandably suspicious of politically frontal art-making, Griffin is nevertheless wrestling with some of the bigger dilemmas at the heart of contemporary art practice, as their recent show, ‘The Song of Lies’ at New York’s Bureau Gallery, makes clear. In the same video work that encompasses their collaboration with Hyde-Vaamonde, (aptly named MERCY) Griffin employs a techno-textual cut-up technique, suggestive of what they term ‘the collective unconscious nervous breakdown’. “I was writing from the perspective of lots of different voices and they all did merge into one, into this character – racing thoughts, fragmented sentences, spewing poetry, thoughts about the apocalypse,” they say.

But what are the origins of this nervous breakdown? This seems to be answered by Griffin’s other recent work that has seen them employ AI model Runway ML on datasets of their own drawings to create large-scale pieces. “I draw all the time, but I was experiencing burnout. I thought it would take [the AI] a long time, but it only took ten minutes” they say. “I felt defeated as an image-maker. I just thought, we’re done for. But then I went back to these images – they are so vacuous. A lot of my

drawings have text and political content, and the machine learning ones had done this thing, where they interpreted words as shapes.” The result is disorienting – a meditation on the post-post-post instability of contemporary (dis)reality and the role of language as a placeholder, a meaningless shape, emblematic of the disinformation age. “I was trying to mash together the man and the machine; it felt like a self-annihilating technology.”

But Griffin is no techno-pessimist. Their faith in art’s ability to adopt and adapt technology, and their determination to put themselves in the novice seat, has brought them to work increasingly with sound and coding in their capacity as an ‘antidisciplinary artist’. “I found the term in a job advertisement that went out from MIT. They were looking for people that could bring together disciplines that aren’t usually put together,” they say. “Others understand it as ‘anti-formal disciplines.’” Subsequently, during their PhD in Queen’s University Belfast’s Sonic Arts Research Centre (SARC), Griffin learned simultaneously to code and to gain more formal understanding of music that let them hear new sounds, learning to use Max MSP, with support from Pedro Rebelo. “I’ve tried to do a linear course with coding, but what you end up doing is being on YouTube a lot of the time, copying things other people have made and putting them together in lots of ways that you want.”

A bricolage-like methodology seems to steer Griffin towards materials and assembly, techniques of demystification where everything is ‘technology.’ “A lot of my work is around technology but a lot of it is also around old traditional ways of working with materials,” Griffin explains. This pull between the technics of the new with technology of tradition means they could be said

to be involved in a form of technological interpellation. In a recent collaboration at Somerset House with Belfast harpist Úna Monaghan, a motorised robot was placed on one harp, with the performance turning into a duet between robot and harpist. In another piece, A Heavy Metal Incense Burner (2024), a hand sandcast incense burner connected to a chain, whose every link was made by Griffin, is discovered to have been originally a product of a 3D file they bought online.

If profanation is play as method, then Griffin employs it as an act of enquiry and demystification – an encounter with breakdown and self-dispossession that is not without hope. One can always begin again from the beginning. They admit owing to the Arts Council of Ireland their ability to keep training and learning new skills. “The funding models provided by the Irish state are incredible and fantastic. It’s a model that other countries should be looking into.” What is next? A work on sixteenth-century ‘harp burnings’ that Queen Elizabeth carried out on Irish harpists, Griffin says. “I’m calling it ‘postcolonial psychosis’.” A perfect metaphor for one’s drive to self-destruct and start over.

Vivienne Griffin is a Dublin-born visual artist currently based between London and New York. Their solo exhibition, ‘The Song of Lies’, ran at New York’s Bureau Gallery from 11 July to 16 August 2024 and was supported in part by Culture Ireland. viviennegriffin.com

Roisin Agnew is an Italian-Irish filmmaker and researcher based in London. @roisin_agnew_