Lismore Castle Arts

MarchMay 2024

Exhibitions across 3 locations: St

Each now, is the time, the space

Leonor Antunes, Alexandre da Cunha, Rhea Dillon, Veronica Ryan

Curated by Habda Rashid 23 March27 October 2024

Lismore Castle Aleana Egan Second-hand 23 March19 May 2024

St Carthage Hall

Carolina Aguirre remember member ember 23 March19 May 2024

The Mill

Lismore Castle Lismore Co

VAN The Visual Artists’ News Sheet A Visual Artists Ireland Publication Issue 2: March – April 2024

Carthage

For opening times of each location www.lismorecastlearts.ie +353 (0)58 54061

Ballyin, Lismore Co Waterford, P51 A2R5

Hall Chapel Street, Lismore Co Waterford, P51 WV96

The Mill

P51 F859

Waterford,

Ryan, Infection I, 2021. Sculpey, found object, thread, metal locker shelf, cable ties, clay 67 x 25.5 x 44 cm.

Alison Jacques, London © Veronica

Veronica

Courtesy:

Ryan

Inside This Issue IRELAND AT VENICE IN FOCUS: COLLECTIVES COLUMN: ON CAPACITY FREELANDS PROGRAMME

Photo: Dawn Blackman

The Visual Artists’ News Sheet

March – April 2024

On The Cover

Eimear Walshe, ROMANTIC IRELAND, 2023; photo © Faolán Carey, courtesy of the Venice Biennale.

First Pages

6. Roundup. Exhibitions and events from the past two months.

8. News. The latest developments in the arts sector.

Columns

9. Wee Windows. Cornelius Browne considers apertures and vantage points onto the past.

Greetings from the Countryside (Strong Emotions). Laura Fitzgerald presents an excerpt from her new artist’s book.

10. On Capacity. Catherine Hemelryk shares some thoughts on delivering meaningful programmes with limited resources. Surface Tactics. For the first in a series of columns, Lian Bell considers the implications of slow travel.

11. Access Toolkits: A Living Tradition. Iarlaith Ní Fheorais outlines her recently published Access Toolkit for Artworkers. Responding to Sound. Catherine Marshall discusses the work of KCAT Studio artist Diana Chambers.

Exhibition Profile

12. An Ciúnas. Sarah Long interviews Marianne Keating about her latest film and touring exhibition.

14. Rehearsals. Ella de Búrca reviews Yvonne McGuiness’s recent solo exhibition at Butler Gallery.

In Focus: Collectives

15. The Material Body. Mná Rógaire, Artist Collective. A Tapestry of Talents. Everything But The Kitchen Sink.

16. Mutual Care. Kirkos, Experimental Music Ensemble.

17. What Makes A Club? Temporary Pleasure, Rave Architecture Collective.

18. Liberatory Practices. Éireann and I, Collaborative Community Archive.

Not About Horses . The Glue Factory.

Critique

19. Olivia O’Dwyer, Author of My Days, 2023, oil on canvas.

20. Olivia O’Dwyer at Kevin Kavanagh

21. Christine Mackey at glór

22. Laura Buckley at Galway Arts Centre

23. Venus Patel at Crawford Art Gallery

24. Kate Cooper at Project Arts Centre

Organisation Profile

26. Social Permaculture. Joanne Laws interviews Viviana Checchia about her plans and aspirations as Director of Void Arts Centre in Derry.

Festival / Biennale

28. Romantic Ireland. Joanne Laws interviews Eimear Walshe and Sara Greavu about the forthcoming representation of Ireland at the Venice Biennale.

International

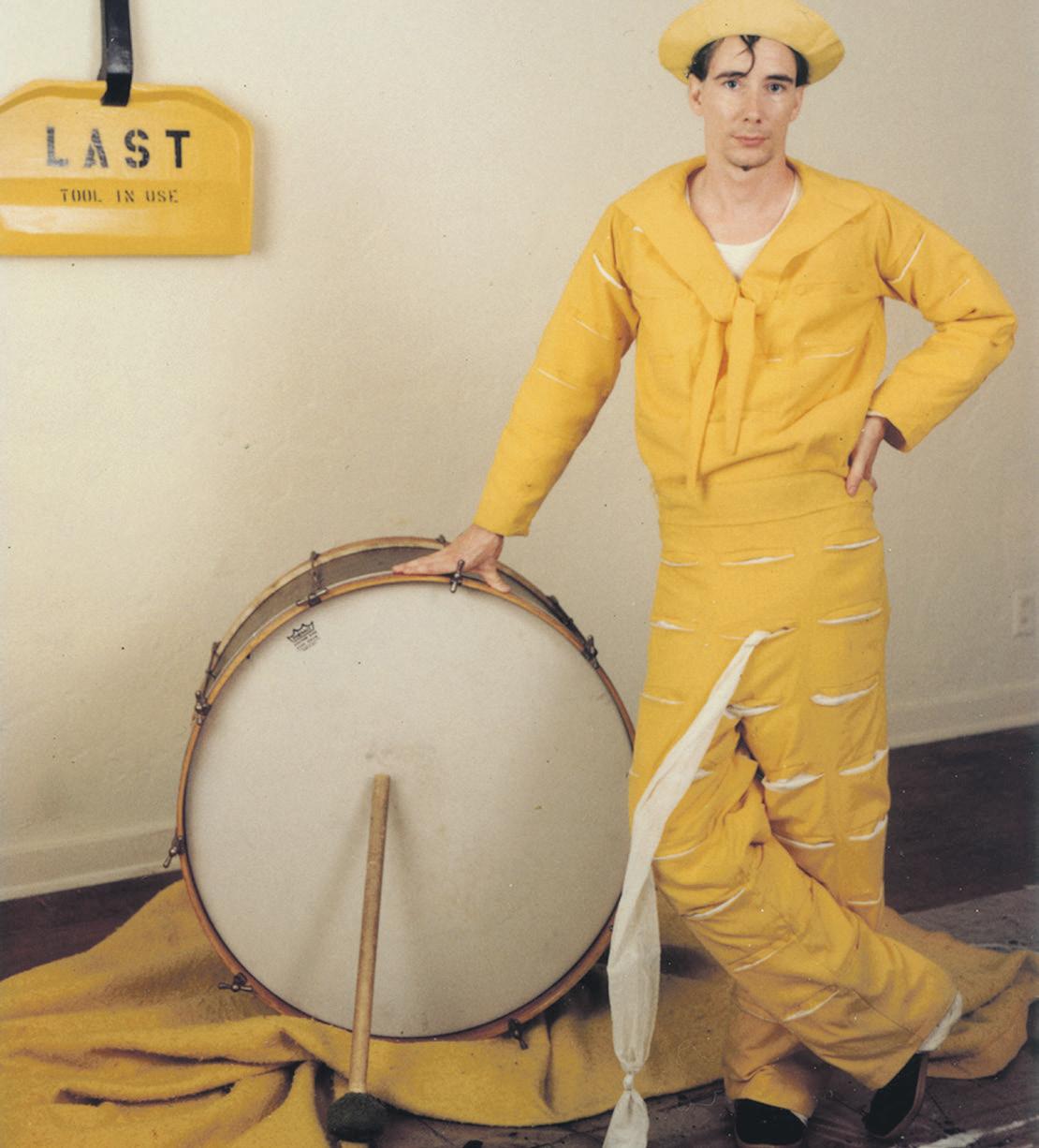

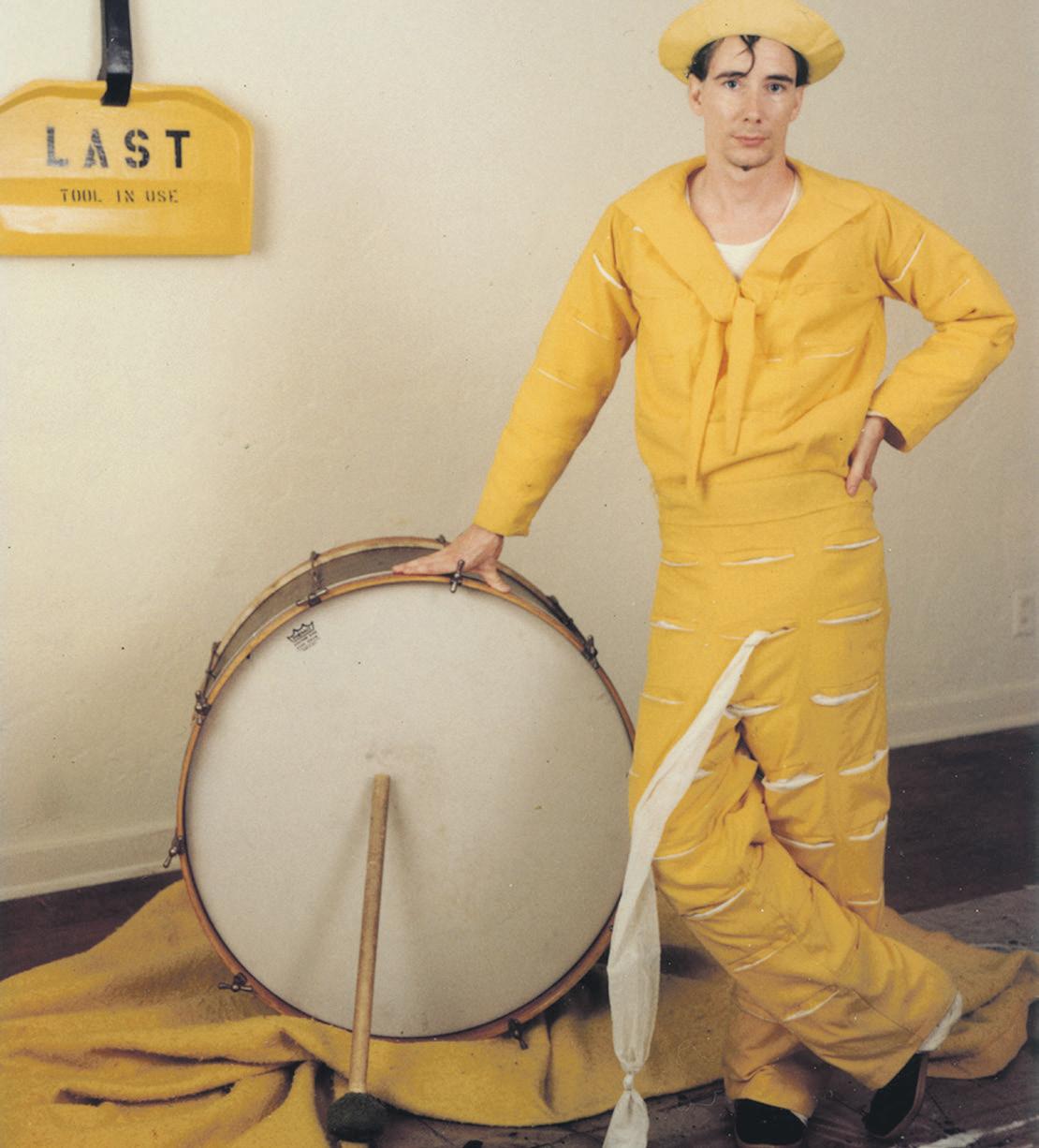

30. Memory Ware. Alan Phelan reviews Mike Kelley’s recent retrospective at The Bourse de Commerce Pinault Collection.

Project Profile

32. Freelands. Thomas Pool interviews the artists from the Freelands Artist Programme and The Freelands Studio Fellow.

Member Profile

35. Vanitas: New Old Paintings. Madeleine Shinnick reflects on the convergence of joy and sorrow in her painting practice. Colour Across the Continents . Shabnam Vasisht outlines the evolution of her practice to date.

Last Pages

36. VAI Lifelong Learning. Upcoming VAI helpdesks, cafés, and webinars.

The Visual Artists’ News Sheet:

Editor: Joanne Laws

Production/Design: Thomas Pool

News/Opportunities: Thomas Pool, Mary McGrath

Proofreading: Paul Dunne

Visual Artists Ireland:

CEO/Director: Noel Kelly

Office Manager: Grazyna Rzanek

Advocacy & Advice: Oona Hyland

Advocacy & Advice NI: Brian Kielt

Membership & Projects: Mary McGrath

Services Design & Delivery: Emer Ferran

News Provision: Thomas Pool

Publications: Joanne Laws

Accounts: Grazyna Rzanek

Board of Directors:

Michael Corrigan (Chair), Michael Fitzpatrick, Richard Forrest, Paul Moore, Mary-Ruth Walsh, Cliodhna Ní Anluain (Secretary), Ben Readman, Gaby Smyth, Gina O’Kelly, Maeve Jennings, Deirdre O’Mahony.

Republic of Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

First Floor

2 Curved Street

Temple Bar, Dublin 2

T: +353 (0)1 672 9488

E: info@visualartists.ie

W: visualartists.ie

Northern Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

109 Royal Avenue

Belfast

BT1 1FF

T: +44 (0)28 958 70361

E: info@visualartists-ni.org

W: visualartists-ni.org

International Memberships Principal Funders

Page 34

Page 31

Page 21

Page 17

Safe to Create Safe to Create is a Dignity at Work programme looking to impact change on the culture and practices of the Arts and Creative sectors. If you or someone you know is facing bullying or harrasment please visit safetocreate.ie

17 FEABHRA – 3 MEITHEAMH | 17 FEBRUARY – 3 JUNE DARREN ALMOND, KEVIN ATHERTON, SARA BAUME, CECILY BRENNAN, URSULA BURKE, ELAINE BYRNE, GARY COYLE, DOROTHY CROSS, JAMIE CROSS, MOLLIE DOUTHIT, AMANDA DUNSMORE, JOY GERRARD, RULA HALAWANI, REBECCA HORN, AUSTIN IVERS, NICK MILLER, BRIAN O’DOHERTY, KATHY PRENDERGAST, GAIL RITCHIE, PATRICK SCOTT, NAOMI SEX, YINKA SHONIBARE, NEDKO SOLAKOV, PHILLIP TOLEDANO, DAPHNE WRIGHT GAILEARAÍ EALAÍNE CRAWFORD PLÁS EMMET, CORCAIGH, TI2 TNE6, ÉIRE OSCAILTE GACH LÁ | IONTRÁIL SAOR IN AISCE CRAWFORDARTGALLERY.IE CRAWFORD ART GALLERY EMMETT PLACE, CORK, T12 TNE6, IRELAND OPEN DAILY | FREE ENTRY

Home, John’s Quay Kilkenny, R95 YX3F

+353 (0)56 7761106 Untitled, 2023. Resin, rubber, expanding foam, pigment, acrylic stand. 170 x 25 x 25 cm (Detail). Photo: Jason Clarke Helen Hughes finding the most forgiving element 06.04— 26.05.24

Evans’

butlergallery.ie

TADA! An exhibition for children by children A Kids’ Own Publishing Partnership Exhibition 17 February – 25 May 2024 www.femcwilliam.com F.E. MCWILLIAM GALLERY & STUDIO Applications are open for the Artist in the Community Scheme Awards 2024 (Round One); funding for collaborative artists and communities to research, develop and create exceptional art together. Closing Date: 25th March 2024. Read more about info sessions, supports and how to apply: www.create-ireland.ie “Cocconing: Catch a Breath” - Catarina Araújo and Mental Health Professionals community group Image credits: Seán Daly An AIC Scheme funded project (2022)

Wednesday

March-November 2024

Emily Waszak 28th March-13th April

Lee Welch 18th April-4th May

Namaco (Han Hogan & Donal Fullam) 9th-25th May

Karen Conway 6th-22nd June

Siobhán McGibbon 18th July-3rd August

Neva Elliott 12th-28th September

Luke van Gelderen 3rd-19th October

Conan McIvor 24th October-9th November

- Sunday,

- 17.00, Free Admission

Castle, Dublin rathfarnhamcastle.ie

29.03

10.30

Rathfarnharm

23.02 -

Elva Mulchrone | Brian Duggan

Dublin

Black Church Print Studio

Black Church Print Studio presented

‘Unlimiting the Edition’ from 12 to 30 January, curated by Ria Czerniak-LeBov, recipient of BCPS Emerging Curator Award 2024. Artists Ailbhe Barrett, Maya Brezing, Niamh Flanagan, Margot Galvin, Des Kenny, and Grace Ryan explored a diverse range of themes and contemporary phenomena, in an equally diverse range of traditional techniques including etching, screenprint, papermaking and carborundum.

blackchurchprint.ie

Kerlin Gallery

Kerlin Gallery presented ‘Them’, an exhibition of new painting, sculpture, and work on paper by Guggi, on display from 19 January to 24 February. Across paintings on canvas and paper, Guggi builds up fields of intense colour layered with the bold, curving outlines of simple vessels and smudgy, broken crosses. In the titular painting Them (2023), two linear forms ascend on the lefthand side of the picture plane – abstract and totem-like motifs that represent the artist’s late parents.

kerlingallery.com

Rua Red

‘A Good Night’s Sleep’ is a bold, colourful, immersive intervention created by artist Morag Myerscough with the community of Rua Red, on display from 1 December 2023 to 3 March 2024. Rua Red commissioned Morag to work with the Irish Refugee Council’s Youth Service, DoubleTake Studio, New Horizon HUB, and the Tallaght Ukrainian community to explore the multifaceted theme of ‘belonging’. Weaving together the diverse journeys and perspectives of all involved, Morag has designed a series of built enclosures that represent a safe, secure, and warm space.

ruared.ie

Douglas Hyde Gallery

The Douglas Hyde presents ‘Medici Lion’, a newly commissioned sculptural work and major solo exhibition by Irish-Parsee sculptor, Siobhán Hapaska, running until 10 March 2024. This is Hapaska’s first major solo presentation in an institution in Ireland. In this exhibition, Hapaska presents the figure of the lion to explore current crises, from the failures of democracy to ongoing conflict and wars, and the ever-present climate crisis. A persistent symbol of power, the lion has associations of justice, strength, courage, and military might.

thedouglashyde.ie

Belfast

RHA Ashford Gallery

John Graham’s exhibition ‘Hold to the now, the here, through which all future plunges to the past’ runs at The RHA Ashford Gallery until 24 March. In Graham’s words: “A drawing, for me, should be free of artifice, straightforwardly self-revealing. It should also be, somehow, unknowable. I make systems of opposing lines, the horizontal cancelling the vertical and vice-versa. A simple dichotomy. There’s no obvious skill involved. And no metaphors, no deliberate associations. ”

rhagallery.ie

SO Fine Art

‘Crosses, Salt Lamps and Fires for a God

That Might Exist’ is the latest solo exhibition by Niall KJ Cullen. The work is installed in harmony with the decorative architecture of the SO Fine Art gallery space, originally a ballroom dating back to 1744. The salt lamps and alterations to the Georgian windows blend the work and the environment with a wash of warm, comforting light that one might associate with a meditation space, a church, or a relaxing domestic setting. On display 8 February to 5 March.

sofinearteditions.com

ACNI

The Arts Council of Northern Ireland presented a group exhibition from its permanent collection at 2 Royal Avenue in Belfast City Centre, bringing together the practices of Shiro Masuyama, Sally O’Dowd, Nina Oltarzewska, and Sinéad Bhreathnach-Cashell. The exhibition ran from 1 to 28 February and featured a selection of multidisciplinary and socially engaged works from the ACNI Collection, highlighting how the artists have used social intervention, materiality and performance in their practices.

artscouncil-ni.org

Catalyst Arts

‘Pond(er)’ was an exhibition exploring the gallery as a site for shared and intimate experiences, examining how an arts space can encourage communal experience and discourse through tactile and sonic interventions. This installation responded to the noted distance and oftentimes loneliness felt following a period of restricted human contact, and instead works to highlight the importance of togetherness, play and collective memory through soft installation and storytelling. ‘Pond(er)’ ran at Catalyst Arts from 1 February to 1 March.

catalystarts.org.uk

R-Space Gallery ‘Threads of Illusion: Dimensions of Space and Time’, by Dr Shelley James, runs at R-Space Gallery until 12 March. Dr James is a glass artist, an international expert on light and well-being, and Lecturer at the Royal College of Art. She is also a trained electrician. Her interdisciplinary practice creates immersive experiences that engage the public with scientific discoveries and their wider implications in fresh and memorable ways. Her clients include arts organisations, museums, global lighting, technology brands, healthcare and education trusts, universities, architects, and designers. rspacelisburn.com

Atypical Gallery

The group exhibition, ‘I Am?’, runs at Atypical Gallery until 15 March, presenting the work of artists Wendy Kelly, James Stewart, Stephen Gifford, Rene Boyd, Leah Batchelor, Lesley McClune, Kathryn Clarke, and Lisa Forsythe. The exhibition showcases each of the artists’ interpretations of “I am, I wonder, I see, I want, I pretend, I cry, I feel, I worry, I say, I try, I hope, and I dream.” Presented is a diverse range of materials and mediums, from drawing and painting to artworks with 3-dimensional elements.

universityofatypical.org

QSS Gallery

From 8 to 29 February, QSS hosted ‘Emergence VII’, a group show of selected artists from Belfast School of Art Degree Show 2023. A panel of four QSS studio holders (Alacoque Davey, Clare French, Gerry Devlin and Karl Hagan) and an independent curator (Francesca Biondi from Gallery 545) selected the participating artists. Now in its seventh, QSS’s annual ‘Emergence’ exhibition provides a valuable and professional platform for recent graduates at a transitional stage in their career.

queenstreetstudios.net

The MAC

Niamh McCann’s ‘someone decides, hawk or dove’ draws from territory borders, architecture, street names, flags, and ceremonies to convolute history and to allow for elucidated slippages and the emergence of complex, non-linear narratives. The title of the exhibition ‘someone decides, hawk or dove’ is a line from the poem Hairline Crack in Belfast poet Ciaran Carson’s 1989 collection, Belfast Confetti Hairline Crack is also the title of a film central to this exhibition, which comprises three acts with two musical interludes. The exhibition continues until 7 April 2024.

themaclive.com

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | March – April 2024

6 Exhibition Roundup

[L-R]: Nina Oltarzewska, Les Réseaux C’est Super Cool 2021, mixed-media sculpture; image courtesy of the artist and Arts Council Northern Ireland; John Graham, Readymade X 2023, acrylic, acrylic ink, and pencil on paper, 24 x 30cm; image © and courtesy of the artist; Niall KJ Cullen, xxiii - 002 - 6x 5y, 2023, acrylic and lacquer on linen, 50 x 40 cm; image © and courtesy of the artist.

Regional & International

An Gailearaí

‘Cré: Believing Earth’ was a group exhibition which ran from 15 January to 23 February. The exhibition draws attention to human interaction with the Irish boglands, focusing on the folklore, mythology, traditions, and the materiality associated with the bogs of Uíbh Ráthach. For this collaborative project, Karen Hendy brought artists and performers to work together, often outside the comfort zone of their familiar work environments and teams – a process that sparked creative dialogue across disciplines.

angailearai.com

Garter Lane Arts Centre

‘Cloud Control’ by Jo Howard is on display at Garter Lane until 18 May. The title for this show was inspired by a recent conversation about the multiple layers of meaning ascribed to clouds. Old phrases like ‘on cloud nine’ or ‘head in the clouds’ take on new layers of meaning these days. Increasingly, we have our head in ‘the cloud’ by way of our devices. The artist is interested in how Big-Tech has hijacked a word so intrinsic to the human experience and turned it into a data centre.

garterlane.ie

Naas Library and Cultural Centre

Inspired by St Brigid’s Well in Liscannor, County Clare, artists Mary Fahy and Frances Bermingham Berrow presented their exhibition, ‘Turas Bhríde – Well’, at Naas Library and Cultural Centre from 27 January to 10 February. The widely depicted religious statues are weighed down with a mantle of modern objects of remembrance: hair ties, rosaries, bracelets, memorial cards, children’s toys. These ritually deposited objects are emotionally charged, weaving layers of unspoken meaning into the site and topography of the well. kildarecoco.ie

Ards Arts Centre

‘Internal Space’ was a joint exhibition of sculptor Ned Jackson Smyth and painter Helen Bradbury. The artists came together in this exhibition at Ards Art Centre to share some of their work created over the past year, which links their personal thinking and perspective in response to the external physical world. The exhibition presented painting, sculpture, and film that give the viewer an insight into the thinking of both artists and the inspiration drawn from the world around them. On display from 1 to 24 February.

andculture.org.uk

LHQ Gallery

Evgeniya Martirosyan’s solo show ‘3+5’ continues until 22 March at LHQ Gallery in Cork’s County Library building. The exhibition was conceived in response to ongoing events in the artist’s home country, Russia, and presents artworks that look at knowledge manipulation and the re-framing of history. Coexisting and opposing versions of ‘truth’ become more apparent in times of conflict. Themes of censorship and contamination of information are explored by the artist, who uses books and other printed materials in the installation. corkcoco.ie

Nenagh Arts Centre

‘Vision, Frequency, Erosion, and Transformation’ by David Harte and Josh Brown was on display from 25 January to 23 February. The artworks of Harte and Brown share a commonality in that they are related to audio, sound and technology and its potential influence on human experience. However, the starting points and the trajectories of each of the artists is distinct, and the resultant works could be seen as being in opposition. Recognising these interesting contrasts and correlations, the artists decided to show their work together. nenagharts.com

CCA Derry~Londonderry

CCA Derry~Londonderry presents ‘Stones from a Gentle Place’, a solo exhibition by artist Susan Hughes. Susan’s practice combines video, audio, sculpture, and installation to examine the mechanics and significance of storytelling in Irish culture. The exhibition follows the artist’s encounter with bioluminescence while swimming in the sea at night, and her subsequent observation of how humans throughout history have made sense of natural phenomena. The exhibition continues until 28 March.

ccadld.org

Linenhall Arts Centre

‘All the Men (We ever loved) are dead or dying’ by Conor O’Grady was on display from 12 January to 24 February. The exhibition examined the complexity of contemporary masculinity though a series of multidisciplinary works that navigate statistical realities with the risk, danger and vulnerability that is inherent within the contemporary male experience. The artworks weaved a narrative documenting an interplay between strength and vulnerability within the re-presentation of certain male identities.

thelinenhall.com

South Tipperary Arts Centre

‘Threadsuns’ (13 January – 24 February) was a solo exhibition by Sophie Béhal, recipient of the Tipperary Artist Residency Award with STAC, supported by Tipperary Arts Office. The exhibited works came from a period of engagement with new materials in a new place. It searches for a new way of being and uses repetition, ritual, and process. The sun and circles are used as a rhythmic refrain and repeated throughout. The circle, and its transcendental properties associated with infinity and certainty, are questioned.

southtippartscentre.ie

Courthouse Gallery & Studios

Curated by Sara Foust, ‘Beyond Brushstrokes: Between Matter and Memory’ at the Courthouse Gallery in Ennistymon (26 January – 24 February) heralds an emerging movement of painters in rural County Clare. Featuring the work of Matthew Mitchell, Kaye Maahs, Sara Foust, Trudi Van Der Elsen, Marianne Potterton, Gerry O’Mahony, and Mary Fahy, this exhibition represents a pivotal moment in the evolving landscape of painting, where traditional techniques intersect with innovative expressions.

thecourthousegallery.com

Mermaid Arts Centre

In ‘World Without End’, 1iing heaney’s debut solo exhibition, explored themes of preservation, perpetual life, replication, and authenticity in the digital world. Researching Wicklow’s protected native oak forest at Tomnafinnoge Woods, heaney takes objects from nature and represents them as virtual and reimagined artefacts. Using a blend of digital imaging and scanning methods, she proposes a microcosmic exploration of technological integration in the natural world. On display from 15 December 2023 to 24 February 2024.

mermaidartscentre.ie

Wexford Arts Centre

The group exhibition ‘Edges’ explores ceramics and sound art practice through the work of artists from three nations at the western and eastern fringes of Europe: Ireland, UK and Estonia. The works were developed as part of artist residencies and international exchanges, creating collaborative encounters across the two disciplines. ‘Edges’ explores what it means to work at the edge of something and how we understand the concept of ‘outsider’. The exhibition continues at Wexford Arts Centre until 21 March.

wexfordartscentre.ie

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | March – April 2024 7

Exhibition Roundup

[L-R]: Katharine West, Suspended Matter #1, 2021, clay, 70 x 45 x 45 cm; image courtesy of the artist and Wexford Arts Centre; Conor O’Grady, Sundown Delirium (haply I think of thee) 2020, watercolour, ink, and water gathered where violence occurs; image courtesy of the artist and Linenhall Arts Centre; Susan Hughes, Portaferry Dusk Swim 2024, Perspex, wood, LED light; photograph by Paola Bernardelli, courtesy of the artist and CCA Derry~Londonderry.

THE LATEST FROM THE ARTS SECTOR

TBG+S Studio Awards

Temple Bar Gallery + Studios is pleased to announce the awarded artists from the open call for Three Year Membership Studios and Project Studios.

Three Year Membership Studios have been awarded to Rachel Fallon, Léann Herlihy, Atsushi Kaga, Barbara Knežević, Frank Sweeney, and Luke van Gelderen. Project Studios have been awarded to Ella Bertilsson, Jialin Long, Marie Farrington, and Áine O’Hara.

Three Year Membership Studios at Temple Bar Gallery + Studios offer a long-term tenure to artists who have developed an established, professional practice. Project Studios offer a one-year tenure to artists who are developing exciting emerging practices and demonstrate talent and

Hennessy Craig and Homan Potterton Awards 2024

The Royal Hibernian Academy of Arts is delighted to announce that artist Stephanie Deady has been awarded the Hennessy Craig Award 2024 and artist Fiach McGuinne as the recipient of the Homan Potterton Award 2024. Both awards, the largest awards for painters in Ireland, were announced at a ceremony held at the RHA Gallery, on Thursday 15 February.

The Hennessy Craig/Potterton jury selected five artists, from both the 2022 and 2023 Annual Exhibitions, who were invited to submit two new works, currently showing at the RHA until 31 March.

Since 2018, The Hennessy Craig Award has been awarded on a biennial basis and is open to any painter under the age of 35 exhibiting in the open submission section of the Academy’s Annual Exhibition, who has studied at a recognised art college on the island of Ireland. This year the RHA introduced the Homan Potterton Prize, created through a generous bequest left by the former Director of the National Gallery of Ireland and foremost scholar, Homan Potterton. This award is for a painter under 35 years of age whose style acknowledges the tradition of painting figurative or landscape subjects.

Each artist is invited to exhibit two new works and although considerate of the work submitted, the awards are based on the overall practice of the artist. This exhibition offers an unparalleled opportunity to view and for the discernible collector a chance to purchase, the very best work by some of Ireland’s most exciting young painters working today.

2024 Shortlisted artists: Daniel Coleman, Stephanie Deady, Isobel Mahon, Polly Maher, Fiach McGuinne, Manar Mervat Al Shouha, Tadhg Ó’Cuirrín, Niamh Porter, Ciara Roche, Casey Walshe.

NGI acquires Harry Clarke artwork

One of Irish artist Harry Clarke’s finest and rarest works of stained glass has become part of the national collection at the National Gallery of Ireland. Titania Enchanting Bottom, created over a century ago in 1922, now belongs to the Irish public and will be free for Gallery visitors to view in the new

potential.

The artists were awarded their studios by a selection panel following an open submission application process. The panel included current TBG+S Studio members and established curators based in Ireland and internationally. The selected artists are representative of the exceptionally high-quality and rigorous contemporary art practices in Ireland today. TBG+S provides excellent workspaces for over 30 artists to work in Dublin city centre. The artwork made in the studios is often exhibited in galleries across Ireland and internationally. As well as studio space, TBG+S offers the artists professional development opportunities such as studio visits from international visiting curators and artists.

year. The acquisition was supported by the Patrons of Irish Art of the National Gallery of Ireland, whose membership fees support acquisitions of Irish art.

Born in Dublin on St Patrick’s Day in 1889, Harry Clarke is one of Ireland’s best known and most beloved artists. He achieved significant acclaim in his short lifetime, working across different media including book illustration. His principal career was in the production of stained glass windows, mainly for churches and religious houses across Ireland, as well as in the UK, US and Australia. He also produced a small number of secular works in glass.

Titania Enchanting Bottom is the only glass work by Clarke that is inspired by Shakespeare. It depicts Act IV, Scene I, from Shakespeare’s comedy A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Featuring characters from the play including Bottom, Puck, Titania, Peaseblossom, Cobweb and Moth, the work is adorned with botanical elements – a detail typical of Clarke’s work. From 1917 to 1922, Clarke made a unique series of miniature panels inspired by literature –including this one – adapting his talent and passion for book illustration to the medium of stained glass. These panels were set into bespoke cabinets, of which several, including this example, were designed by Dublin-born furniture maker James Hicks (1866-1936). Titania Enchanting Bottom is one of just five panels that survive. At the National Gallery of Ireland, it joins The Song of the Mad Prince (1917) which is on display in Room 20 and was acquired by the Gallery in 1987. These panels are significant to the understanding of Harry Clarke as an artist. They are the forerunners to the The Eve of St Agnes (1924) and The Geneva Window (1930).

Dr Caroline Campbell, Director of the National Gallery of Ireland, said: “As we reach the end of a busy but brilliant year at the National Gallery of Ireland, it is wonderful to be able to give the nation this special Christmas present. Our stained glass room and works by Harry Clarke are some of the most popular objects in our collection, so we know that our visitors – from home and afar – will love Titania Enchanting Bottom. I’m delighted that we have been able to add a work of such rarity to the

national collection, and I thank our Patrons of Irish Art for their generous support of this new acquisition.”

Through new acquisitions and conservation, the National Gallery of Ireland develops and preserves the nation’s art collection. With extensive exhibitions, public programmes, community engagement, education and outreach work, the Gallery further commits to its role as a caretaker of creativity and imagination. The Gallery thanks and celebrates the role of its supporters, including the Patrons of Irish Art.

Titania Enchanting Bottom is undergoing Conservation treatment and will go on display to the public for free in Room 20 at the Gallery in the new year.

The Gallery would like to thank the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media for its ongoing support.

Ireland at the 2024 Venice Biennale Minister for Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, Catherine Martin TD, on Thursday 15 February, launched Ireland’s Representation at the 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia at the Mansion House. Artist Eimear Walshe, with curator Sara Greavu and Project Arts Centre, has been selected to represent Ireland at the prestigious event. The Department, through Culture Ireland, commissions Ireland’s representation in Venice in partnership with the Arts Council.

The Venice Art Biennale, which will run from 20 April to 24 November 2024, remains the most important global platform for the exhibition of visual arts involving the public, members of civil society, individuals and institutions. It offers a unique opportunity for Irish artists to engage with international audiences

Responding to this year’s theme, ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ – selected by curator of the Biennale, Adriano Pedrosa – the Irish Pavilion will present an exhibition entitled ‘ROMANTIC IRELAND’. It will comprise a multi-channel video installation and an operatic soundtrack housed in an immersive earth-built sculpture. Eimear Walshe’s project explores the complex politics of collective building through the Irish

tradition of meitheal: a group of workers, neighbours, kith and kin who come together to build.

New University of Atypical CEO Edel Murphy has been appointed CEO of Belfast-based University of Atypical, a disabled-led charity that develops and promotes the work of d/Deaf, disabled and neurodiverse artists and enhances access for audiences.

When she was diagnosed as a young child with Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 3, an extremely rare condition affecting around four people in Northern Ireland, doctors told her she would not live beyond the age of 12.

Having had 19 major operations and defied all medical expectations, the 45-yearold County Donegal woman is looking forward to her new role in her dream job.

She said: “Today is a humbling day for me. I first came into the University of Atypical as a visitor, a fan, a friend, a volunteer and then an employee. I came because I felt I belonged. I saw then how clearly this organisation empowered people to do great things and make this city and our region a better place for people like and unlike me to be.”

The University of Atypical, funded by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, supports and campaigns for disabled artists through a number of programmes. With its own Atypical Gallery and the Ledger Studio for Performing Arts, the organisation also runs the annual Bounce Arts Festival and many other programmes.

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | March – April 2024 8 News

Rachel Fallon, Jelen Vagyok - Red Apron, 2023, digital performance documentation for ‘Adsum / I Am Present / Jelen Vagyok’, Budapest, 2023; photograph by Gabriella Csoszó, courtesy of the artist and TBG+S.

Plein Air

The Rural

Wee Windows

CORNELIUS BROWNE CONSIDERS APERTURES AND VANTAGE POINTS ONTO THE PAST.

NOT A SPECK of notion did I have, picking up a sun-warmed hardback of poet William Soutar’s deathbed journal, Diaries of a Dying Man (Edinburgh: Canongate Press, 1954), from a stall near the River Clyde, that certain books could become old friends. From a vantage point of 35 years later, I have a gull’s-eye view of myself funnelling coins into the hand of the surly Glaswegian bookseller, who was never pleased to see this waifish pavement artist, pawing Scottish literature.

Stricken by spondylitis while serving in the Atlantic with the Royal Navy in 1917, Soutar was bedridden from age 32 until his death, 13 years later. Only the window fed Soutar’s nature-craving eyes. With foresight and a hammer, once confinement embedded itself, the poet’s father enlarged this aperture in their stone cottage. For the remainder of his life, due to his position in bed, Soutar saw people only in part. The shining exception was Jenny, paid to clean the window every Friday morning. In his diary for 1939, Soutar reveals how he sets aside his writing and reading the moment she appears, as Jenny has come to embody the human form in action. Sometimes, if I’m painting near the house and in need of a breather, I take my old friend Soutar out to hear birdsong and feel the breeze against his pages. We sit for about as long as it took Jenny to sheen the glass.

On our Presbyterian side, a strain of immobility runs through my family, likely owing to multiple sclerosis and depression. The aunt with whom I lived the summer I encountered Soutar, diagnosed with MS in her twenties, was bedfast not long after my Impressionist chalks had washed from the streets of Glasgow. I began painting in the open, as a child, hoping to restore views to my outdoors-loving grandmother, in bed for the last decade of her life. As a family, we often visited the bedsides of pallid relatives. Daniel, my first cousin, once removed, took to his bed in his early twenties and remained there until the spring morning,

just days after his fiftieth birthday, when a coffin was squeezed into his bedroom. He once asked me to paint him a few places nearby that he had loved in his freedom. These landscapes he taped to his wall, calling them “wee windows.”

I only paint standing up, frequently after long walks along lanes and through fields, pushing my legs through sedge and bramble, climbing drystone walls and barbed-wire fences, yanking my feet from sinkholes, facing into wind and rain, and keeping on, season after season. My paintings are made by a human form in action. I pace to stay warm. Kickbox air to boost blood flow. Thoughts circulate as I walk and paint, a companionable traffic. Jim Ede, founder of Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, and friend to artists I revere, among them Alfred Wallis and the Nicholsons (Ben and Winifred), held windows on a par with the greatest works of art. Writing in the Listener magazine around the time Soutar began diary-keeping, Ede considered windows “an advantage in these days of financial depression, for whether it is wet or whether the sun shines, the content of that light, dazzling or subdued, is always beautiful. It is all the time changing, so that just about our window we have one of the most beautiful moving pictures we can have.”

From the windows of their cars, elderly locals remark that they often see me painting near ruins where my ancestors lived. Treading their ground, I’m filled with wonder. A feeling wells in my gut when I try to picture families of ten or more functioning in such two-roomed, one-chimney stone cottages. The windows are few and tiny, some blocked with stones. In brutal winds, I sometimes pitch my easel within these roofless walls. I might be standing where once a sleeper half-heard, half-dreamt the same Atlantic howls. I pick up my brush, and paint through windows, casting light onto the past.

Cornelius Browne is an artist based in County Donegal.

Greetings from the Countryside (Strong Emotions)

LAURA FITZGERALD PRESENTS AN EXCERPT FROM HER NEW ARTIST’S BOOK.

THE PRESSURE IS on for me to conform. There have been some things happening recently. Strange weather, weird vibes. Unsettling neighbourhood relations. An argument over a right-of-way. A tussle with a man and a gate. I’m not sure whether to salute anyone anymore.

A land grab.

The community knows something is afoot. Their hands are busy. They are out in force, cleaning the beach and each other’s kitchens. Scrubbing at grief. Pulling plastic out of dead sheep’s teeth. The sheep have come back in on the tide, washed up on the shore.

Say nothing.

Some people got bored of the beach cleanup, preferring to see what kind of messes are in other people’s homes. I followed the crowd into one of them and I found curses in the presses. I pocket them.

You mind your own business and I’ll mind mine.

Other members of the community are airing out bad relationships from the cupboards and murderous feelings from the bedclothes. I see them hanging these out, up on the clotheslines.

What’s the worst that can happen?

World War 3, famine, sickness, extinction. Slipping fan belts. Mortgages sliding into arrears. Solicitors’ letters, financial acrobatics, money turning somersaults in the bank. Someone stealing our road. Eventually, it might all end in tears, or worse, in court. My legs and arms are covered in bruises. I cannot walk.

A good run is better than a bad stand.

Which of the above did I do? I did both, I ran, and I stood, placing my body in the gap where they were closing over our road with the steel barricades. I had seen this deployed successfully by women in stop-

ping wars and saving trees. My body would stop the gap being filled and save our road.

What are your emotions? asks the CBT app. Certainty. Fear. Sadness. Pride. Foolishness. Despair. Trigger: My friends have… I type. Disappeared out the gate, like missing cattle. I was not able to stop them running past me, neither was I able to stop those men putting up those barricades. I put down the phone and stand out in the road and shout to all my lost friends:

HOW, HOW, HOW, HOW.

This is the same call Dad used to use – for the cattle. They would come running down the mountain to the hill gate when he called them, ready to be moved across the road.

Old friends are best.

How did we move the cows before in the old days? I ask myself this as the cars whizz by and as an articulated lorry overtaking a tour bus nearly takes me out. We used to flag down the cars with long bits of black water pipe, rewarding the drivers with jolly salutes as soon as the last cow’s arse disappeared safely through the gate.

Death trap. (Just saying).

The road was quieter then. Less traffic. From the hill gate, we moved the herd down the road, my Great-Grandfather’s Road. An historical road. The artery from the main road to the mountain. It’s blocked off now by six gates – six barricades. Three at the main road and three up the back behind our house. He put them there with the three men some weeks ago.

Laura Fitzgerald is an artist from rural County Kerry. This column is an excerpt from her artist’s book, published on the occasion of her exhibition, ‘Strange Weather’, curated by Niamh Brown, which continues at Ormston House until 20 April. laurafitzgerald.ie

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | March – April 2024 9 Columns

Cornelius Browne reading William Soutar, 2023; photograph by Paula Corcoran, courtesy of the artist.

Laura Fitzgerald, Left-Hand Finger Salute 2024, pen and Sharpie marker on archival paper; image © and courtesy of the artist.

Art Work On Capacity

CATHERINE HEMELRYK SHARES SOME THOUGHTS ON DELIVERING PROGRAMMES WITH LIMITED RESOURCES.

CAPACITY IS HOW much you can do with a set of resources. These resources include: people, money, materials, space, time, health, technology, environment, focus, and more. At CCA Derry~Londonderry, we aim to work smartly with what we have, to make the best programmes we can. Our resources include: a small but mighty team – one full time, three part-time; a small budget made up of restricted and unrestricted programme and core funding; gallery space / office / equipment; and an open approach to working. A list:

We want to avoid:

• Doing projects that don’t fulfil our mission just for the money.

• Burning out staff.

• Being miserable.

• Exploiting artists or anyone we work with.

• Being sloppy with the projects we make.

Some approaches we take:

• We know how much staffing our current funding covers and so we work in line with this capacity.

• We work our contracted hours and build in staffing and artist fees to project funding. If there is no budget for this, we won’t do a project. We are realistic with our own expectations on what can be achieved within budgets.

• We aim to work flexibly to accommodate the non-CCA work/life of parttime staff, and share managing the galleries.

• We work as a team to build in time for our full-time member of staff to take TOIL (Time Off In Lieu) after intensive periods.

• We are clear with artists and others at the start of projects about budgets, resources and timescales so everyone is on the same page. Whilst we cannot always control timescales set by funders, we can control what we apply for in the first place and find smart ways to work within limitations.

Some thoughts on working contracted hours:

• It is very tempting to work more than our contracted hours.

• If we work more hours than we are paid for, we are contributing to the shadow economy that perpetuates low pay as the real primary resource of a project, hiding the real cost and resources.

• A personal note: I get ill if I overwork. I have a compromised immune system, so have to be careful; however, no one should overwork, immune system shenanigans or not.

• We keep a TOIL log and plan PAL (Paid Annual Leave) in advance, to make sure that the gallery staffing is covered, and workloads managed, so we can enjoy our time off.

• Feeling guilty for taking time off is not

helpful.

• Feeling guilty for all the things we could be doing but aren’t, because there is no capacity, is not helpful.

• Underestimating how much resource something will take is easy to do.

• Not having work emails on personal phones helps with work/life balance.

• If something has a deadline, we flexi. But if that happens all the time, then we have a problem and need to do address why this is and make changes, so that it doesn’t happen continually.

• Some things are easy and fast; some things have to wait, whilst other urgent matters are tended to; and some things are really difficult and can’t be rushed. Feeling guilty for being slow isn’t helpful.

• We don’t always get this right; external factors will throw all sorts of curve balls, but we do our best and continually strive to do better.

Practical steps organisations can take:

• Do learn your organisation’s capacity and don’t over-promise what you can deliver.

• Don’t work more than your contracted hours. If everyone works extra, it contributes to sustained underinvestment in the arts and burnout.

• Do budget for paying artists and freelancers for their time.

• Don’t substitute staff with volunteers. Where you do work with volunteers, factor in training and volunteer management.

• Do keep a TOIL log. If you are continually going over hours, then you need to either: Increase the staffing and secure funding to pay for staff time..

• Don’t forget to budget for staff time for reporting, research, and fundraising.

• Do your best to ensure work stacks allow staff to take TOIL.

• Do respect staff time off.

• Do create open lines of communication and structures so that anyone can ask for help if they are struggling; change can only happen if problems are known.

• Do ask if the project is right for your organisation: Is it in line with your mission? Can it function within your budget / timescale / resources? If no, can you increase any of these? And if still no, this really is not the right project for your organisation.

• Don’t be a perfectionist; life is too short.

• Do keep perspective.

• Above all, whether you are an organisation or an individual, be kind and remember that health is the most important thing.

Catherine Hemelryk is the Director of CCA Derry~Londonderry.

ccadld.org

Art Work

Surface Tactics

FOR THE FIRST IN A SERIES OF COLUMNS, LIAN BELL CONSIDERS THE IMPLICATIONS OF SLOW TRAVEL.

I’M STANDING ON the platform of a German railway station. There are two bags at my feet: a pink day pack, with such valuables as my laptop, passport, wallet, and chargers; and a larger blue backpack, filled mostly with dirty clothes. I realise I should probably have my valuables in the less easy to steal bag. When moving, I wear the blue backpack on my back, and my pink backpack on my front, usually hanging from one shoulder. I feel strong, and I can walk quickly and quietly. I’m happy not to be adding to the din of suitcase wheels pinging off pavements, off cobbles, off tiles: tactactactactactac

I’m travelling with an Interrail ticket as an experiment. I want to research how feasible it is to take fewer flights, while continuing (and expanding) my professional relationship with mainland Europe. As an artist and arts manager based on the island of Ireland, I’ve flown a lot for work over the years. I’m doing this research as an ethical experiment, but not just one to do with the pollution of aviation fuel. This journey is also about the ethics of deliberately going slower in an industry that increasingly values speed and productivity. I want to see what it does to my thinking, practice, experiences, and to my connections with other humans.

One morning, having boarded like a zombie at the crack of dawn, I sit in the nearly empty restaurant carriage drinking strong coffee and eating bread and jam while looking out at the morning sun on the beautiful Czech-German border, with a winding river, and green wooded hills, and a castle on a cliff. It is a perfect Interrail snapshot moment, with all the administration, awkwardness, confusion, sore muscles, perimenopause, dirty clothes, messiness, flatlands, self-doubt, grumpiness, and boredom not in the picture.

I try to find ways of advocating for slowing down and taking more time, particularly to people who work in arts organisations. To resist pressure from funders to forever do more with less. To reimagine ‘value for investment’. Yet here I am, thanks to a grant from one of those funders. To do this research, I’ve been given an Agility Award from the Arts Council. I design two threeweek periods of travel, knitting together some European work, attending festivals and exhibitions, online work from Ireland, and a networking event.

Throughout my travels, I send postcards to the Arts Council to thank them for their support and tell them what I’m up to. I imagine them giving one or two administrators a few moments of respite to remember what all the emails, spreadsheets and meetings are for, and what they mean to the people they are supporting. I have a lot of sympathy for the people working there, and other big arts institutions in Ireland. The systems they have to operate within

are extraordinarily badly designed, patched together with the kind of work practices that often lead to burnout.

I find support for my journeys in other ways too. I’ve asked some organisations employing me over the summer to spend a bit more on my travel, I’ve organised a house swap in Brussels, I’ve asked people I know in various cities to sleep on their sofas, and I’ve tried to add activities to each leg, to get the most out of it all.

When I come across other artists and arts workers who are also travelling long distances overland, I ask them to tell me about their experiences. Pippa Bailey is maintaining a European work life while based in Australia: “This time I travelled 6800km by rail and road to save a tonne of carbon. This is not a gimmick, it’s an ethical stance.” She and I cross paths at the Prague Quadrennial, where we have a beer in the June sun.

Pippa says: “I was deliberately rehearsing a future that I think is needed. I am tired of working in broken systems. I can imagine different ways of managing time and resources and understand how to hold the creative processes needed to allow new systems to flourish. However, the world of work I am in is desperately hanging onto old ways, almost aggressively defending them. Travelling slowly helped me have perspective on this, finding strength to go back in for another round of discussion. It also offers concrete examples of change and has provided more ideas about how to do better.”

I’ve noticed when I talk to people about this, they don’t believe they have the power to slow their work down. I can see they think I’m being naïve. I think many of us have more power than we give ourselves credit for. The more of us that can demonstrate the value of this way of working, the easier it will be to articulate it to organisations, and the more likely they will support us to do it. Right? And we can also advocate for the people running the organisations to slow down themselves and give their staff time to work at a more humane pace. Doing less, but better. Imagine.

Lian Bell is an artist and arts manager based in Dublin. This column is an extract from Lian’s longer essay, Surface Tactics, first published on her website in October 2023. lianbell.com

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | March – April 2024 10 Columns

Access Work in Focus

Access Toolkits: A Living Tradition

IARLAITH NÍ FHEORAIS OUTLINES HER RECENTLY PUBLISHED ACCESS TOOLKIT FOR ARTWORKERS.

“DEVELOPED BY QUEER and trans activists of color in the [San Francisco] Bay area, Disability Justice is the second wave of the disability rights movement, transforming it from a single issue approach to an intersectional, multisystemic way of looking at the world. Within this framework, disability is defined as an economic, cultural, and/or social exclusion based on a physical, psychological, sensory, or cognitive difference... Disability is structurally reinforced by ableism, a system rooted in the supremacy of non-disabled people and the disenfranchisement of disabled people through the denial of access.”1

Access Toolkit for Artworkers is a free online resource that contains practical information on how to reduce access barriers and combat ableism in the arts. The toolkit is intended for curators, producers, and arts administrators working independently or in arts organisations. This toolkit contains practical information on how to plan, produce, and exhibit accessible art projects, including information on access riders, financial planning, slow production, display, and creating an accessible workplace. This information is intended to address the access barriers faced by d/Deaf, neurodivergent, chronically ill and disabled artists, audiences and artworkers, as well as those who experience ableism. I developed the toolkit with a group of advisers – including Bridget O’Gorman, Hannah Wallis, Kat Hawkins, Jamila Prowse, Jo Verrent, Leah Clements, Linda Rocco, and Maggie Matić – and through my own experience as a disabled curator, to address the distinct lack of information in the sector on how to work with disabled artists and meet the diverse access needs of audiences. It is written through a Disability Justice framework and follows the examples of existing toolkits and resources variously created by artists, writers, producers, and disability activists, such as Carolyn Lazard (cited above), Sins Invalid, Unlimited, Leah Clements, Alice Hattrick, and Lizzy Rose.

Access Toolkit for Artworkers is broken into four key sections: Planning, Production, Workplace, and Audiences & Display. The planning section includes information on access riders, fundraising, managing access budgets, governance, and sharing opportunities accessibly. The Production section outlines how to reduce barriers for artists and teams when making work, with information on hiring support workers, slow production methodologies, and accessible communication. The Workplace section outlines how to create more antiableist workplaces from the perspectives of employees and employers. This includes information on reasonable adjustments, access check-ins, flexible working, special leave, unions, pay, conditions, and manageable workloads, as well as accessible recruitment to reduce barriers for disabled

applicants, from application through to interview. Audience & Display contains robust information on displaying art, hosting events, and reducing barriers for audiences though captioning, audio description, lighting, seating, and sign language interpretation. At the end, Other Resources links to a wealth of information on writing access statements, alt text, and further access suggestions for events.

It took almost three years to bring the toolkit to fruition, finally launching in January 2024. Access was central to how the project was made, particularly in terms of design, with the website working towards web accessibility standards through the rigorous work of web designer, Saerlaith Uaid Ní Dhuibhir, who navigated us through the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 3.0. This included a number of essential features such as screen reader compatibility, audio versions, word counts, and colour-blind friendly formats. Saerlaith also undertook essential accessibility testing to ensure the website was screen reader compatible across devices and platforms. Many of the accessibility features I could do myself, including the audio versions, which I recorded using a voice memo app on my phone.

Access also informed how we worked. We worked in a slow manner, taking regular breaks and extending deadlines to accommodate our needs and capacities. I found the project overwhelming at times, and it would have been difficult to manage this much information without the support of Hannah Willis as editor. In the future, I hope to build upon and deepen the knowledge of the toolkit in conversation with a wider set of practitioners to create further access points, most urgently British Sign Language and Irish Sign Language versions.

In the spirit of anti-ableism, Access Toolkit for Artworkers is in many ways a gesture of generosity – from the immense generosity of the advisors, in sharing their experiences and skills, to the ongoing generative generosity of those who engage with the toolkit and incorporate its principles into their practices. Above all, this toolkit was made possible through the generosity of the knowledge that has come before. The access toolkit format has become somewhat of a tradition now, with each new iteration building upon previous ones – a trajectory that I hope continues.

Iarlaith Ní Fheorais is a curator and writer based between Ireland and the UK. Access Toolkit for Artworkers was supported by the Arts Council England. accesstoolkit.art

1 Carolyn Lazard, Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and A Practice (Recess, 2019).

Responding to Sound

FOR THE SECOND KCAT COLUMN, CATHERINE MARSHALL DISCUSSES THE WORK OF ARTIST DIANA CHAMBERS.

DIANA CHAMBERS IS something of a phenomenon, capable of producing at least one finished painting a day, yet never missing the essential spark that drives her imaginative vision. An artist in the assisted studios at KCAT Arts Centre in Kilkenny, she works from other people’s photographs rather than from direct experience, but what she does with those sourced images is what makes her paintings stand out.

I was privileged to work with KCAT as curator of ‘The Engagement Project’ from 2014 to 2020, which invited each studio artist to work in a creative partnership with artists from other contexts, making work that reflected their mutual exchanges. Diana joined a year into the programme in 2015. Her intense paintings of musical subjects fascinated and attracted fellow artist, Sinéad Keogh. One of their resulting works together was an installation with a painting by Diana, of the singer Bessie Smith, accompanied by a vinyl record for which Sinéad designed a label using a motif from the painting. It was a sincere homage from the artists to the singer, and to each other, as they pursued their very different practices.

Since then, Sinéad Keogh has included Chambers’s work in each of the annual Soul Noir Festivals, while Diana has gone on to produce increasingly lively and exotic images – mainly of musicians but also of animals. Movement attracts her, and is echoed in every stroke she applies to paper or card, even if that is only postcard-sized. Under the spell of her image, she swaps the brush from hand to hand, rather than taking a break from painting. She loves vibrant colours but uses them economically, perhaps only as carefully selected highlights. The energy, resulting from the fusion of active line and often acidic colours, bursts out of the painting with a charge that has

nothing to do with the size of the image. It is as if the spirit of the subject irradiates her imagination and her brush-holding hand.

For the ‘Women and War’ exhibition in the National Opera House during the 2023 Wexford Opera Festival, Diana painted a face that filled the picture plane with an open mouth, singing, wailing, exploring, communicating a sound, the more powerful because it was forever unheard. The rhythms are expressed instead through the extraordinary movement of her white, curly hair. This was accompanied by another of her Jazz musicians, this time a saxophone player whose rhythms so electrify him that his fingers detach from his hands to dance across the keyboard. Elsewhere, a group of musicians, instruments shining out of the darkness and clothes vibrating with the sound, sway in unison in their collective dream.

As one commentator on the Soul Noir website remarked last year: “It can seem as if she is trying to keep up with the pace of her thoughts and feelings as she paints, as though the process of painting is constantly trying to catch up with her. It can also seem that Diana feels there is so much in the world to be explored and painted that there is little time to procrastinate. The result is an ever-evolving body of deeply expressive and beautiful works.” Diana has an innate understanding of movement as an instinctive response to sound, whether that is from an animal at large, or a performer caught up in the magic of the performance.

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | March – April 2024 11 Columns

A member of the KCAT Curator’s Network, Catherine Marshall is an art historian, freelance curator, and member of Na Cailleacha. nacailleacha.weebly.com

Diana Chambers, Piano Man, 2019, acrylic on paper, 42 x 59 cm; photograph by Declan Kennedy, courtesy of the artist and Kilkenny Collective for Arts Talent (KCAT).

Sarah Long: An Ciúnas/The Silence (2023) builds on your body of films exploring Irish histories, particularly the diaspora. The work was recently presented as a three-channel installation at The Showroom in London (13 October 2023 – 13 January 2024) and will soon tour venues throughout Ireland. Can you talk about how this work fits your larger oeuvre and at what point these ideas around presentation began to develop?

An Ciúnas

Marianne Keating: Over the last decade, my practice has focused on tracing the legacy of the Irish diaspora in the Caribbean, examining Irish-Jamaican anti-colonial ties and both countries’ fight for self-determination through a series of film installations. With An Ciúnas/The Silence, I wanted to push my film production, integrating these complex intersecting narratives in one space. By allowing these histories to be complex, these lingering archival impulses give voice to these histories, returning a voice to what had once been rendered mute. I aimed to highlight how these movements and themes are interconnected and that nothing exists as a singular moment.

From the initial concept of An Ciúnas/The Silence, I wanted the screens to also have a role in the narrative, with no one screen holding dominance or hierarchy. The use of 5:1 sound design was also crucial in the space. For example, when the dialogue comes from the left screen, the left speaker becomes the active speaker, drawing the viewers to turn and interact with that screen, making them active rather than passive participants.

The three-channel installation allows me to highlight multiple legacies of colonialism and how, until those systems that are still in place are fully broken down, true decolonisation can never be achieved. As Audre Lorde states, and which is highlighted in the

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | March – April 2024 12 Exhibition Profile

SARAH LONG INTERVIEWS MARIANNE KEATING ABOUT HER LATEST FILM AND TOURING EXHIBITION.

Marianne Keating, An Ciúnas/The Silence, installation view, 2023, The Showroom, London; photograph by Dan Weill Photography, image courtesy of the artist.

work, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” This work allows the viewer to see how these threads intertwine and overlap.

SL: The work highlights how Empire’s power structures create dualisms that strengthen its position. Could you speak more about this idea, particularly your provocation, “How Free is Independence?”

MK: The work interrogates how far it may be possible to upend the loop of “unfree independence” that left countries tied to or subjugated by systems set up by the British Empire. Here we see how, after Independence in Ireland, the mechanism of oppression remained and passed to the Catholic Church, which, although a different power, was a power nonetheless that continued to control the population through oppression and subjugation. In the context of Jamaica, I examine the resulting impact of the Irish diaspora on contemporary politics. The work traces how men of Irish descent replaced the outgoing colonial body and that, although change was coming, it was to be based on the systems devised by the coloniser rather than a new, radical approach.

The legacy of colonialism can be seen in how borders were utilised in the 20th century in Ireland and Jamaica, as well as each country’s relationship with Britain today. The role of a border becomes interchangeable depending on the dominant countries’ economic needs. For those who emigrate, the reason has not really changed from that of the Famine years, with economic survival being predominant.

The work’s presentation as a continuous loop reflects that even though the viewer is witnessing historical moments of liberation, migration, and the fight for self-determination and independence, the topics, tensions, and troubles have remained the same throughout history in many ways – highlighting the seemingly endless loop of unfree ‘independence’.

SL: The work’s bilingual title, An Ciúnas/The Silence, is also striking because of its implied dualism: English and Gaeilge; Ireland and the diaspora; the archive and what is lost, censored, or otherwise hidden.

MK: The title of the exhibition can be read in many ways that examine the pervasive power of Empire and the intersecting erasures within Irish diasporic histories. ‘The Great Silence’ stemmed from the Famine, which reduced the passing down of lore between lost generations of Irish speakers in the Gaeltacht regions through death and migration. The silence equally refers to survivors of the Famine, “who would not talk of the past” and “would remain silent as to why and how they had survived.” More recently, ‘the silence’ refers to those who remained in Ireland and chose not to talk about the possibility of the failure of those who migrated. Materially, the silence references the near-total destruction of public records held at the Public Records Office of Ireland at the beginning of the Irish Civil War during the bombardment of the Four Courts in Dublin.

SL: The work is strikingly insightful, with a firm grounding in research, statistics, and archival sources. Can you describe your approach to working with these materials?

MK: Through my films I move forward and backwards in time, manipulating time, modes, and forms of production, and incorporating many sources and creating new, dense and complex narratives. My montage style allows me to incorporate many modes of production, from textual graphics to archival black and white photographs taken with traditional large format cameras or 35mm film reels, which invites the viewer to explore the historical past. Often, the viewer accepts these images as genuine, unedited, and natural without staging or bias, but this is often not the case.

Through the process, I digitally sample many sources (colour, black and white, still and moving images, as well as sound), recombining this visual and aural data

to share with the audience. In some films, I use this method to disrupt present-day footage filmed with a 4K camera by distressing the footage and reducing it to what Hito Steyerl describes as a ‘poor image’ – a substandard copy that is deficient and inferior to its higher quality original. It may no longer be the hierarchical premium quality original, but it is still an image, and in its lower resolution format concedes universal access, decolonial in its approach.

SL: The work has been exhibited in The Showroom in London and will soon tour Ireland. How do you envisage these different contexts and sites will impact the work’s reception?

MK: In one way, that is a tricky question; I left Ireland in September 2011 after the recession pushed me out. The story I am telling is so much a part of all of us, yet by leaving, you are no longer the same; you are different. You see Ireland through an outside lens because you no longer get to see the day-to-day changes, and you are othered by the process. In one way, I tell these histories to inform people of all nationalities who don’t know them. Still, many people in Ireland will speak to aspects of these histories better than I do, as I’m not a historian.

But from what I have found from those of all nationalities who have watched my films, the compassion, empathy and understanding for all countries that have shared similar histories – colonialism, migration, and the struggle for economic survival – unites us all together. Our continued solidarity is our strength. All we have to do is look through our eyes and see the same in others.

Sarah Long is an artist and writer based in Cork. In 2020, she created The Paper – an online forum for discussing and responding to the Cork art scene.

@thepapercork

Marianne Keating is an Irish artist and researcher based in London. The Irish tour of ‘An Ciúnas/ The Silence’ was initiated and organised by SIRIUS, and is curated by SIRIUS Director Miguel Amado, with Rayne Booth as Project Manager. mariannekeating.com

‘Áilleacht Uafásach /A Terrible Beauty’ runs at The Model in Sligo from 16 March to 19 May and includes a larger presentation of the artist’s work. Subsequent tour venues include Galway Arts Centre, Rua Red, Limerick City Gallery of Art, and Wexford Arts Centre. themodel.ie

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | March – April 2024 13 Exhibition Profi le

Marianne Keating, An Ciúnas/The Silence, 2023, film still (detail), 'Irish women protest in New York, while British officers await transportation to Jamaica'; photograph by Central News Photo Service, 1920, University College Dublin Archives, image courtesy of the artist.

Marianne Keating, An Ciúnas/The Silence installation view, 2023, The Showroom, London; photograph by Dan Weill Photography, image courtesy of the artist.

Rehearsals

ELLA DE BÚRCA REVIEWS YVONNE MCGUINESS’S RECENT SOLO EXHIBITION AT BUTLER GALLERY.

UPON ENTERING YVONNE McGuinness’s exhibition at Butler Gallery, I am immediately immersed in a world where the past, present, and future enact various assemblies in a symphony of sight and sound. The exhibition, aptly titled ‘Rehearsals’, is a regional exploration of various themes, ranging from theatrical improvisation and play to political engagement and the fluidity of change in Ireland. These inquiries are encapsulated in two new video works: Priory and Schoolyard, both made in 2023.

The auditory experience is a standout feature, reminiscent of Brian Eno’s ambient compositions. A soundtrack – featuring a blend of organ tones, chirping birds, playing children, distant applause, and a muffled, prophesying orator – transports the viewer to a different realm. The audio is punctured by short mantras, each spoken three times – foreboding phrases that chronicle a lack of control, an imminent flood, and a fall.

Priory is a large-scale immersive video projection that plays with the senses. Overlapping visuals of fabric blowing in the wind create a sense of chaos and beauty. Members of the Equinox Theatre Company (an inclusive ensemble based in KCAT arts centre in Callan) gather in the ruins of Callan Augustinian Priory, setting up a mise-en-scène of chairs and a podium. As we draw nearer, the visuals become more layered, and we see the group perform as audience to a blurry speaker. The echo in the soundtrack is so potent that it obscures the narration. The audience becomes unruly, waving flags bearing images of rocks, and chanting phrases like “The water’s coming in.” The assembled performers break away individually, each enacting their own spirituality, as the power of the orator’s words dissolve.

Schoolyard presents a contrasting, yet complementary vision. Here, a multi-channel installation of different sized screens depicts a moving tableau of children at play. On the largest screen, we see them quickly constructing a ‘scene’, using sticks, ropes, plastic, and tarpaulin. Their creation is reminiscent of medieval scenes, carved into the cornices of cathedrals, with the children posing on tables, chairs, and ladders as saints and prophets. The piece is punctuated by close-ups of individual children on the smaller monitors, chanting

mantras such as “It’s out of control,” and “Careful, it’s going to fall.” Fluorescent colours – a kaleidoscope of vivid greens, pinks, blues, yellows, and oranges – reflect from the screens, creating a mesmerising effect.

While distinct, the two video works share thematic concerns. Both are parable-like, echoing ancient Ireland, while suggesting spiritual approaches to construction and holistic relationships with play. The sense of foreboding in both pieces conjures apocalyptic imagery of biblical floods or other climate related disasters. The older group in Priory resonates with a ghostly, communal aura, poetically alluding to the dwindling power of the church in Ireland. I was surprised by the religious potency of the younger group’s ad hoc creation, the residue of Ireland’s ascetic past still reverberating through new generations in layers and echoes. Both groups reference the structure of ritual.

A significant element in the exhibition is the use of green silk flags, which appear in both videos, while also being physically present in the exhibition, as part of a large-scale fabric assemblage, adding a tactile and grounding element. The flags bear images of rocks in various compositions; some floating singular on the green backgrounds, others assembled into arches, cloisters, and pillars. The vivid green not only roots the exhibition in Irish heritage but also serves as a metaphorical green screen, prompting considerations of Irish culture as something that can be superimposed onto. This feature is particularly poignant when considering the themes of religion and spirituality, exploring ideas of faith as both a grounding force and a framework for personal identity.

‘Rehearsals’ is a reflective journey, situated in the magical crossover between play, improvisation, legacy, and heritage. It encapsulates a sense of wistfulness, as if foregrounding parts of Irish culture that are disappearing, while simultaneously pushing the boundaries of artistic expression, interpretation, and collaboration.

Ella de Búrca is an Irish visual artist and lecturer at SETU Wexford College of Art. elladeburca.com

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | March – April 2024 14 Exhibition Profile

Above: Yvonne McGuinness, Frontier 2023, fabric assemblage; Below: Yvonne McGuinness, Schoolyard, 2023, multi-channel installation; photographs by Ros Kavanagh, courtesy of the artist and Butler Gallery.

In Focus : Collectives

The Material Body

Mná Rógaire

Interdisciplinary Artist Collective

MNÁ RÓGAIRE IS an emerging collective that fuses the interdisciplinary practices of Northwest-based recent graduates, Samantha O’Reilly, Laura Grisard, and Rebecca Christina Devins. Our name directly translates as ‘Rogue Women’. Our mother tongue, Gaeilge, resides within us as a tangible material; its resurrection is an act of instinctual resistance. The group’s origins are rooted in our experience of completing a BA (Hons.) in Fine Art at the Atlantic Technological University Sligo – a course that was re-imagined prior to our attendance to foster an open approach to student practices. A connection developed organically from there, through our mutual interests and understanding.

The challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic altered our learning processes and continues to influence our practices today. This experience simultaneously drove our independence whilst emphasising the importance of communal support and assistance. We rely on Zoom meetings to maintain communication and momentum within the group, as well as facilitating work.

Throughout our academic experience, collaboration was always prevalent. Participation in Celina Muldoon’s exhibition and performance, ‘Kurnugia NOW!’ at The Dock (10 September – 12 November 2022), solidified our friendship, and through Celina’s mentorship, we began to recognise the opportunities and potential in our group. Mná Rógaire will contribute to Celina Muldoon’s forthcoming exhibition, which opens at The RHA in March.

Events and workshops with art groups, such as Bbeyond in Belfast, and performance artists including Sinéad O’Donnell and Alastair MacLennan, introduced by our lecturer Hilary Gilligan, contributed to our self-determination and collective mindset. The artists we met were supportive and encouraging, which significantly impacted our final year in ATU Sligo.

Finishing our degree, we officially became Mná Rógaire and immediately felt the support of other performance artists. Sandra Corrigan Breathnach reached out to us and introduced us to Deej Fabyc

from Live Art Ireland – an artist residency programme in Milford House, North Tipperary. Our residency at Live Art Ireland resulted in a short film, Lingering Presence (2023), and the participation of Mná Rógaire in Culture Night in September 2023, as well as a screening during the performance showcase, ‘Alive and Kicking’ in November 2023.

This sense of community and agency helped us to evolve and gain exposure to the art world. Artist empowerment, co-operation, and inclusion are profound aspects of our work ethos. Inspired by DIY attitudes and activities that we observed elsewhere in the contemporary Irish art scene, we decided to establish Mná Rógaire in the Northwest. The region and landscape have been elemental in our growth, both individually and collectively.

In order to truly give meaning to our work, we employ intuitive methodologies, whilst reflecting on our observations within contemporary life, and concurrently highlighting socio-political injustices. We wish to ignite and contribute to emerging critical discourse around ideas of inclusion, diversity, unity, activism, oppression, and anarchism through movement.

The material body is an integral part of our work, engaging with physical objects, materials, and spaces within performance. Embodying spiritual exchanges and responses from the audience informs our process. Our fellowship allows us to be connected in the physical and mental state during live activations. We are currently conceptualising a video with performance-to-camera. Other forthcoming projects include a durational performative drawing installation at The Hyde Bridge Gallery in Sligo (28 May – 29 June) that will that will incorporate sculptural elements to further activate material and spatial concerns.

Mná Rógaire are an interdisciplinary artist collective based in the Northwest of Ireland.

@mna_rogaire

A Tapestry of Talents

Everything But The Kitchen Sink Multidisciplinary Art Collective

OUR IRELAND AND UK-based art collective, Everything But The Kitchen Sink (EBTKS), comprises five artists from diverse backgrounds: Keely McLavin, Ren Coffey, Shannon Eager, Niamh Cody, and Shannon McGovern. We each navigate a spectrum of materials and processes, bringing unique perspectives and skillsets to the collaboration. We thrive on the exchange of ideas, creating a vibrant community where mutual inspiration and learning drive our collective growth.

Through the mediums of text, video, sculpture, installation, AI, sound, and textiles, we each draw from eclectic themes in our individual practices, including identity politics, social justice, and the human condition. The collaborative environment fosters an atmosphere of artistic exploration that continuously pushes the boundaries of what is possible. The collective’s ethos is deeply informed by the DIY spirit of past art movements, mirroring historical formations and practices. This is not just a nod to history but a living principle guiding our collaborative projects. This commitment is evident in our research-based approaches, our historical grounding of contemporary issues, and our experimental use of various processes and materials.

Current EBTKS activities and themes resonate with the contemporary human experience, such as womanhood, queer identity, and social justice. We use our work to challenge societal norms, employing a language of subversion to address issues such as misogyny, queer existence, and the complexities of identity in a heteronormative society. Keely McLavin’s researchbased practice explores notions of womanhood in a patriarchal society. Grounded in historical research, her work uses language to subvert misogynistic ideals. Through a combination of text, video, and other visual responses, McLavin creates an empathetic protest, addressing contemporary issues while highlighting their historical roots.

Ren Coffey’s focus on sound, both as a medium and subject, is evident in their multidimensional practice. Working across sound, sculpture, and installation, Coffey brings experiential knowledge and an