Fingal, A Place for Art

Fingal Artists’ Support Scheme 2023

Fingal County Council invites applications from artists for up to €5,000 of an award towards travel and professional development opportunities, a residency, or the development of work.

The award is open to practising artists at all stages in their professional careers working in music, visual art, drama, literature, film and dance.

To be eligible to apply, applicants must have been born, have studied, or currently reside in the Fingal administrative area.

The funding is for projects or initiatives which will take place between 1st May and 31st December 2023.

Closing date for receipt of applications: Friday 24th February, 2023 at 4.00pm

For further information and to apply please visit: www.fingalarts.ie or www.fingal.ie/arts

Alternatively, please contact Eoghan Finn at Fingal Arts Office by email at eoghan.finn@fingal.ie or by phone on 087 773 8427

www.fingalarts.ie

On The Cover

Isabel Nolan, Desert Mother (Saint Paula) and Lion, 2022, water-based oil on canvas; photograph by Lee Welch, courtesy the artist, Kerlin Gallery, and Void Gallery. 6. Roundup. Exhibitions and events from the past two months. 8. News. The latest developments in the arts sector.

First Pages

Columns

9. The Signature of All Things. Cornelius Browne discusses the origins of artistic anonymity. Mashq. Kip Alizadeh outlines their participation in ACNI’s Minority Ethnic Artists Mentoring and Residency programme.

10. Through Care, Towards Access. Iarlaith Ni Fheorais introduces the radical potential of access in the visual arts. Curating in a Negative Spectrum. Matt Packer discusses the history of international curatorial invitation in Ireland.

11. Practical Magic. Siobhán Mooney outlines the 12th iteration of Periodical Review at Pallas Projects/Studio. We Need to Talk About Painting. Karen Ebbs reports on a series of talks she recently organised at IMMA and The Complex. 12. The Kerr Shoe Collection. Eve Parnell considers a collection of twentieth-century Irish shoes housed in NIVAL. Direct Support. Elida Maiques outlines her participation in Mermaid Art Centre’s Transform Associate Artist Scheme.

Casa Dipinta. Brenda Moore-McCann discusses the Italian townhouse owned by Brian O’Doherty and Barbara Novack.

Organisation

14.

The Space to Grow. Members of TBG+S consider the organisation’s continued importance on its 40th anniversary.

Ireland’s St. Ives. Martina O’Byrne outlines the evolution of Artform School of Art in Dunmore East in Waterford.

20.

32.

22

19. Tinka Bechert, Handlanger, 2018, mixed media on raw canvas. Page

Editor: Joanne Laws Production/Design: Thomas Pool News/Opportunities: Thomas Pool Proofreading: Paul Dunne

Critique

‘UPHOLD: New Collections’ at 35DP

Grace Dyas ‘A Mary Magdalene Experience’ at Rua Red

‘In and of Itself – Abstraction in the age of images’ at The RHA

Kevin Mooney ‘Revenants’ at IMMA

Brian Fay ‘The Most Recent Forever’ at LCGA

Re_sett_ing_s. John Graham reviews a recent exhibition by Jaki Irvine and Locky Morris at The Complex, Dublin.

Corban-scale. Jennifer Redmond reviews Corban Walker’s solo show continuing at Crawford Art Gallery until 15 January.

Flotsam, jetsam, lagan and derelict. Kevin Burns reviews Isabel Nolan’s current solo exhibition at VOID Gallery, Derry.

Get Together 2022. Joanne Laws and Thomas Pool report on VAI’s annual networking event for visual artists.

The World Was All Before Them. Emma Campbell interviews Clare Gormley about her curatorial vision for TULCA 2022.

EVA International 2023. Thomas Pool interviews the EVA Platform Commission artists making new work for the festival.

Defining an Arena. Lucy and Robert Carter on Grilse Gallery. VAI Member Profile

The Man Who Sees Through Shadows. Mike Bunn.

Up in the Sky with the Swallows & Swifts. Gillian Deeny.

Oonagh Latchford. Catherine Marshall on Oonagh Latchford.

CEO/Director: Noel Kelly Office Manager: Grazyna Rzanek Advocacy & Advice: Elke Westen Membership & Projects: Siobhán Mooney Services Design & Delivery: Alf Desire News Provision: Thomas Pool Publications: Joanne Laws Accounts: Grazyna Rzanek

Board of Directors:

Michael Corrigan (Chair), Michael Fitzpatrick, Richard Forrest, Paul Moore, Mary-Ruth Walsh, Cliodhna Ní Anluain (Secretary), Ben Readman, Gaby Smyth, Gina O’Kelly, Maeve Jennings, Deirdre O’Mahony.

The Visual Artists' News Sheet: Visual Artists Ireland: Republic of Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland The Masonry 151, 156 Thomas Street Usher’s Island, Dublin 8

T: +353 (0)1 672 9488

E: info@visualartists.ie W: visualartists.ie

Northern Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland 109 Royal Avenue Belfast BT1 1FF

T: +44 (0)28 958 70361

E: info@visualartists-ni.org W: visualartists-ni.org

Exhibition Roundup

Dublin Copper House Gallery

Sean Fingleton’s exhibition ‘Musicians and Landscapes from Donegal to Clare’ ran from 17 to 24 November 2022. Fingleton says: “My drawings of the musicians originate from visits to the Willie Clancy Festival. They are developed through the medium of oil pastel with gestural expression and colour to the fore. The drawings are from recorded impressions of live musicians done in sketch books, executed in pencil, and later transposed into larger works in oil pastel and mixed media in the studio.”

thecopperhousegallery.com

LexIcon

‘Heirloom’ is an installation created by artist Rachel Doolin at the LexIcon in Dún Laoghaire. Doolin has been artist in residence for the last two years with the Irish Seed Savers Association, Ireland’s only public seed bank. As risks from the climate crisis and global conflicts escalate, seed banks are becoming an increasingly precious resource that could one day prevent a worldwide food crisis. The exhibition continues until 5 March.

dlrcoco.ie

NCAD Gallery

‘‘Why be an artist?’ (after Leigh Hobba and Noel Sheridan)’ is an exhibition and film project by Oisín Byrne and Vaari Claffey with Kevin Atherton, Isadora Epstein, Gary Farrelly, Leigh Hobba, Séamus Nolan, Grace Weir, and Noel Sheridan. The invited artists respond across a variety of registers, both paying homage to and challenging Sheridan’s narrative content and performative approach. The exhibition continues until 15 February.

ncad.gallery

Photo Museum Ireland

Photo Museum Ireland presents ‘The Light of Day’, the first major retrospective of Tony O’Shea, who is regarded as a legendary figure in documentary photography and one of Ireland’s most important contemporary photographic artists. Curated and produced by Photo Museum Ireland, this retrospective exhibition brings together for the first time his seminal bodies of work. The exhibition continues until 18 February.

ArtisAnn Gallery

Julie Corcoran’s recent solo exhibition, ‘Looking for Light – The Heroine’s Journey’, took viewers on an epic journey. The protagonist, in a beautiful dress, journeys deep within and is resurrected achieving divine unity of the feminine and masculine. Each of Julie’s images are born out of an emotion or concept. The artist combines digital photographs in layers to produce pieces that look like they were painted, rather than manipulated on screen. The exhibition ran at ArtisAnn Gallery from 30 November to 17 December 2022. artisann.org

Cultúrlann McAdam Ó Fiaich

After Brexit, under EU food safety rules, sausages are no longer allowed to enter Northern Ireland from Great Britain. Belfast-based, Japanese artist Shiro Masuyama has realised a new social intervention using sausages to highlight the Irish Sea Border (which was created after Brexit) in his exhibition ‘Brexit Sausages’. Following international residencies in the Irish Museum of Modern Art and Flax Art Studios, Masuyama (who was born in Tokyo) moved to Belfast, where he’s been based ever since. The exhibition continues until 26 January. culturlann.ie

Catalyst Arts

Catalyst Arts recently presented their first member’s show in their new space at 6 Joy’s Entry, near Cornmarket in Belfast city centre. The exhibition was titled ‘it feels hairy to start from nothing again’ – perceived as emphasising the precarious position of artist-led spaces in the city – and presented audio-visual work by four Catalyst members: Peter Glasgow and Sun Park, Niamh Seana Meehan, and Reuben Brown. ‘It feels hairy to start from nothing again’ was the final show of the year at Catalyst Arts and ran from 1 to 15 December 2022.

catalystarts.org.uk

Golden Thread Gallery

‘Hold on Tight’ is a provocative exhibition of corporeal artworks by four female artists working in performance and moving image: Sinéad O’Donnell, Katherine Nolan, Jayne Parker, and Hollie Miller. Each of these artists work in response to their bodies, questioning the vulnerability of human flesh through lived and sometimes violent experience. ‘Hold on Tight’ presents the different ways in which these artists use materials and how they can be manipulated by, or alongside the body. The exhibition continues until 14 January.

goldenthreadgallery.co.uk

SO Fine Art Editions

The group show, ‘Winter Exhibition’, presents new work by Yoko Akino, Emma Berkery, Cathy Burke, Niall Cullen, Niamh Flanagan, Mary A Fitzgerald, John Fitzsimons, Taffina Flood, Debbie Godsell, Sophie Gough, Alison Kay, Allan Kinsella, Richard Lawlor, Stephen Lawlor, Sarah Long, Bernadette Madden, Marie-Louise Martin, Eoin Francis McCormack, Matthew Mitchell, Mary O’Connor, Shane O’Driscoll, Sorca O’Farrell, Emma O Hara, Padraig Parle, Tom Phelan, Linda Plunkett, Luke Reidy & Colm Toolan (SEK2). The exhibition continues until 7 January. sofinearteditions.com

The LAB

‘The Swinging Pendulum’, by visual artist Joanna Kidney, brings the immediate language of mark-making and line into the complex language of painting. To this end, the malleable nature of encaustic paint (molten pigmented beeswax) enables both a distillation and a materiality in the work. The paintings enfold a lexicon, gathered continually from the everyday, and the sensory experiences of touch and proprioception – the sense of self-movement, force, and body position. On display from 18 November to 17 December 2022.

dublincityartsoffice.ie

The MAC

To mark the end of their 10th anniversary celebrations, The MAC presents a group exhibition of new work, titled ‘New Exits: 10 Years of Painting Shows’. Whilst set within the context of the many significant painting exhibitions The MAC has presented since its inception, the exhibition is primarily an opportunity to draw attention to and celebrate the painting practices that have emerged and continue to flourish through the work of graduates of the BA and MFA Fine Art courses at Belfast School of Art since 2012. The exhibition continues until 26 March.

themaclive.com

Ulster Museum

The 141st Annual Royal Ulster Academy exhibition was on display at the Ulster Museum from 14 October 2022 to 3 January 2023. The RUA is the most enduring body of practicing visual artists in Northern Ireland. The exhibition showcases work from established artists and new artists from all over the world, alongside work by RUA Academicians. Now in its 141st year, this exhibition continues to provide a relevant platform for contemporary painting, sculpture, film, printmaking, installations and photography.

ulstermuseum.orgRegional & International

CCA Derry~Londonderry

CCA Derry~Londonderry’s group exhibition, ‘Fugitive Seeds’, was curated by Borbála Soós and was on display from 19 October to 21 December 2022. ‘Fugitive Seeds’ considered how endemic, alien, and fugitive seeds connect to colonial histories, including those in Northern Ireland and more specifically Derry/Londonderry and its port. The presented works helped to unearth layered histories around plant and human migration and border ecologies.

ccadld.org

Chapel Hill School of Art

‘Technically Art’ was an exhibition of work by the technical support staff of the Crawford College of Art & Design in Cork. Spanning a variety of materials and concepts, traditional and contemporary, the exhibition reflected their own artistic ideals and expertise, practiced on a daily basis in college and in their own personal studios. It is clear from the presented work that the staff are invested in both art education and the vibrant, cultural community they contribute so much to. On display from 2 to 16 December 2022.

chapelhillschoolofart.ie

Galway Arts Centre

Reverberate is an oral history project devel- oped by Éireann and I, a black migrant community archive, in collaboration with members of Galway’s African diaspora. The project invited Black migrants settled in Galway to recount their journeys to Ireland, their relationship with the city, and to reflect on whether they have developed a sense of belonging. Reverberate documents the legacies of migration as they happen, giving narrative agency and equal centring to each perspective. On display from 3 to 22 December 2022.

galwayartscentre.ie

Highlanes Gallery

‘The Tyranny of Ambition’ is a group exhibition at Highlanes Gallery, curated by Graham Crowley, on display until 18 February. The idea and subsequently the title for the exhibition was inspired by the film Florence Foster Jenkins (Stephen Frears, 2016). One of the central characters declares that once he had faced up to what he called ‘the tyranny of ambition’, only then could he start to live and be happy. Crowley’s intention as a practicing painter and curator of this exhibition is to share with a wider audience some less well-known work.

highlanes.ie

KAVA

The annual postcard show by Kinvara Area Visual Arts (KAVA) ran from 2 to 11 December 2022. The artwork by KAVA members was anonymously displayed, and all works were for sale. When the artwork was collected, only then was the name of the artist revealed to the buyer. Having proven in previous years to be great fun, and an ideal way to shop locally to find a unique Christmas present for someone special, KAVA were delighted to be able to put on the show again this year.

kava.ie

Mermaid Arts Centre

‘Púca in The Machine’ is an exploratory collaboration between three artists, coordinated and organised by Shane Finan. The artists have worked on new interpretations, creating artworks that respond to the unique and unusual history, mythology and ecology of the Poulaphouca Reservoir. The artists are Alannah Robins, Niamh Fahy and Finan. First exhibited at Blessington Library in February 2022, the exhibition continues at Mermaid until 7 January.

mermaidartscentre.ieTriskel Arts Centre

Róisín O’Sullivan’s exhibition ‘I See Skies’ features a new series of paintings that began at the Tony O’Malley residency in Callan, County Kilkenny. There, the artist spent over a year immersed in nature, embracing each intimate surface in the studio as an emotional response to the complexities of life. O’Sullivan makes paintings and objects that reflect the natural world around her, taking a deep interest in collecting and responding to materials such as wood and leaves. The exhibition continues until 26 March.

triskelartscentre.ie

The Courthouse Gallery and Studios

‘Curdle’ by Kevin Gaffney, Bassam Al-Sabah and Jennifer Mehigan, was on display from 4 November to 3 December 2022. Each artist has a surreal approach to storytelling with images, texts and voice-overs bending reality to a breaking point, mirroring how trauma distorts, remakes and retells lived experience in its own image.

To curdle is to render something ‘wrong’ or ‘bad’, or ‘to spoil’. Curdling represents this condensing of a reality gone sour through the different image-making methods in the exhibition.

thecourthousegallery.com

The Model

The Model presents ‘Portrait Lab’, a thematic exhibition exploring representation through the expanded field of portraiture. The show questions how portraits function, who is reflected and who is overlooked.

‘Portrait Lab’ includes artworks by Irish and international artists and is presented on the occasion of ‘The Sunset Belongs to You’ – a major creative initiative that commissioned Geraldine O’Neill and Mick O’Dea to create oil portraits of 18 Sligo children for The Niland Collection. Exhibition continues until 21 January.

themodel.ie

glór

‘Abigail O’Brien Selects…’ was a group exhibition at glór in collaboration with the RHA. Abigail O’Brien, the first female president of the RHA in its 200-year history, selected an extraordinary line-up of artists from the RHA council, including: Una Sealy, James English, Vivienne Roche, James Hanley, Eithne Jordan, Colin Martin, Pat Harris, Alice Maher, Dorothy Smith, Mick O’Dea, and Abigail O’Brien. The exhibition continues at glór until 14 January.

Regional Cultural Centre

‘Swallowing Geography’ was an exhibition at the Regional Cultural Centre and Glebe House & Gallery in Donegal. The intent of the exhibition was to observe the dynamics between belonging and exclusion in response to the Donegal context. It presented the lived and imagined experiences of inhabiting space, and geographical, domestic, and digital worlds. It featured new work by Donegal artists Cara Donaghey, Laura McCafferty, Eoghan McIntyre and Jill Quigley. On display from 15 October to 17 December 2022.

regionalculturalcentre.com

The National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art

Daphne Wright’s sculpture, Primate (2009), is currently showing as part of the group exhibition ‘Hot Spot – Caring For a Burning World’, curated by Gerardo Mosquera at The National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome. Primate is a cast of a male rhesus monkey, dressed in a silk coat of blunt ended thread-hairs with its face painted. This artwork was originally supported by the Art Council Ireland and Carlow County Council. The exhibition continues until 26 February 2023.

Zurich Portrait Prize 2022

David Booth has won the Zurich Portrait Prize 2022 for his painting, Salvatore (2021) – a portrait of fellow artist and friend, Salvatore of Lucan. Booth said of his winning artwork: “I spotted Sal one morning while in the studio. He was suited in a brilliant red Adidas one-piece tracksuit, his hair jet-black, and his pointed features solemn and reflective. I sat Sal down and took his picture. The life of an artist is characterised by intense ambitions and doubts. With this portrait I wanted to convey this, and the way in which Sal is resting into contemplation.”

The annual competition showcases contemporary portraiture and is open to artists from across the island of Ireland, and Irish artists living abroad. Booth received a cash prize of €15,000 and was commissioned

Graphic Studio Appoints Director

The board of Graphic Studio Dublin (GSD) announced the appointment of Laura Garbatavičiūtė as the new Executive Director. In her role, Laura will lead the organisation and assume the responsibility for the strategic vision, artistic development and operational management of the charity, comprising both the studio and gallery.

Laura is an award-winning entrepreneur, published author, mentor and multidisciplinary artist with a strong track record in cultural development, arts leadership and brand curation. Laura was most recently a Consultant at Design Skillnet and prior to that worked at the award-winning web agency Artizan Creative Ltd as a Mentor and Growth Consultant.

Her experience as a co-founder at Block T in Smithfield for over eight years prior to that will be extremely relevant to the Executive Director role at Graphic Studio Dublin. Block T was ground-breaking as a progressive arts organisation that subsidised a community of 120, supporting artists during the midst of a severe economic downturn. During her tenure there, Laura led the team that was responsible for producing over 500 projects, provided over 5000 mentorship hours to Block T members and students, won Cultural Attraction of the Year at the Dublin Living Awards (2011) and numerous other awards. Laura has a BA Hons Degree in Fine Art Media from NCAD.

Graphic Studio Dublin is Ireland’s oldest and largest printmaking studio with currently over 90 members. It was founded in 1960 to provide printmaking facilities to Irish artists and to facilitate the development of successful working practices for artists through all stages of their careers. Currently located on North Circular Road in Dublin 1, GSD offers printmaking facilities with technical and peer support to artists in etching, screen printing, photo intaglio, carborundum, linoprint, woodcut, Japanese woodblock, letterpress, mezzotint, and digital print. The gallery in Temple Bar was founded in 1988 and is an important unique selling point of the organisation, as no other Irish print studio has a professional stand-alone gallery space. GSD is the only gallery in Dublin dedicated solely

THE LATEST FROM THE ARTS SECTOR

to create a work for the National Portrait Collection, for which he will be awarded a further €5,000. Two additional awards of €1,500 were given to the highly commended works of Cara Rose and Gavin Leane.

The exhibition features the shortlisted artists: Rachel Ballagh, Zsolt Basti, Shane Blount, Patrick Bolger, Enda Burke, Aisling Coughlan, Catherine Creaney, David Creedon, Ian Cumberland, Barry Delaney, Aodán Feeney, Alexis Pearse Flynn, Vanessa Jones, Bernadette Kiely, Vera Klute, Emily McGardle, Fiach McGuinne, Tom McLean, Mick O’Dea, Liz Purtill, Sorcha Francis Ryder, Marie Smith and Marc O’Sullivan Vallig.

The exhibition will travel to the Regional Cultural Centre in Donegal from 3 June to 2 September 2023.

to the promotion of contemporary fine art print.

Creative Climate Action Fund

In late November 2022, Minister for Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, Catherine Martin, and Minister for the Environment, Climate, Communications and Transport, Eamon Ryan, launched a €3 million fund to support imaginative creative projects that build awareness around climate change and empower citizens to make meaningful behavioural changes.

Applications for the scheme opened in December 2022 at creativeireland.gov.ie. The successful teams will include experts from the climate science, community engagement, as well as the arts and culture sectors. The ‘Creative Climate Action II: Agents of Change’ programme is a joint initiative of the Creative Ireland Programme and the Department of Environment, Climate and Communications. The programme is calling for creative projects which address the following:

• Encourage everyone to rethink their lifestyles

• Connect with the biodiversity crisis

• Enable a fair and just transition in making lifestyle changes

• Assist citizens to understand the climate crisis

• Adapt to the effects of climate change

There are two funding strands:

1. Spark: This strand is for those looking to pilot a new idea, or who want to deliver a creative project at a local level. Organisations, community groups and creative groups who can inspire, build knowledge, skills and confidence are welcome to apply for grants between €20,000 and €50,000.

2. Ignite: This funding strand is suitable for those with experience in delivering public engagement projects at scale and are proposing durational projects with extensive public participation. Applicants may be eligible for grants between €50,000 and €250,000.

Minister Martin said: “In 2021 Ireland’s

Climate Action Plan outlined the steps that needed to be taken to create a more sustainable future for Ireland. That plan was ambitious and called on all sectors of society including the creative community to play their part in achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. I am proud that the Irish government has such an explicit link between national cultural policy and climate policy. The first Creative Climate Action projects have done much to capture the public imagination, mobilise communities and show how to make the changes needed. Climate change is humanity’s most important challenge, and we need creative projects such as these to galvanise positive action.”

Minister Ryan said: “Significant cultural and systemic change across all of society is needed to address the climate crisis. This change can only be achieved through fully exploring avenues for innovative and creative ways to inspire people to take action. The cultural sector has a unique part to play in this culture change and I look forward to seeing the exciting ways projects funded through the next phase of the Creative Climate Action Programme will engage people.”

Major Redevelopment at Crawford

The Minister for Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, Catherine Martin T.D. announced the planning application for a major redevelopment at Crawford Art Gallery. This is a flagship project in the Minister’s programme of investments under the National Development Plan, which will see many of our much-loved National Cultural Institutions restored, renewed and future-proofed for generations to come.

Commenting on the planning application in late November 2022, Minister Martin said: “Today is an extremely important day not just for the Crawford Art Gallery, but for our wider cultural ecology. Today we are submitting a planning application for an ambitious project which will transform the Gallery, will create new public spaces for cultural expression and civic discourse, and critically, will see this heritage building restored and renewed to the highest standards of sustainability.”

The project has been designed by an interdisciplinary design team, led by award-winning Grafton Architects, with funding provided by the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media. The design will provide significant new exhibition and public spaces, a new Learn and Explore facility to engage new audiences, and a new public gallery providing panoramic views of the city. The project will also address long-standing challenges with the fabric of the historic building, will create fit-for-purpose storage spaces for our invaluable National Collection, and will significantly enhance the sustainability of the building to support meeting our national emissions reduction targets. Critically, the project will create a new entrance onto Emmet Place, opening the Crawford onto a new urban plaza at the heart of the cultural life of the city.

The project is being delivered as part of the Minister’s National Cultural Institutions Investment Programme under the National Development Plan. Under the Public Spending Code, day-to-day delivery of the project is being led by the Crawford Art Gallery and the OPW.

Film Artist in Residence at UCC

The Arts Council and University College Cork welcome Maximilian Le Cain as the newly appointed Film Artist in Residence for 2023. This role, based in the School of Film, Music and Theatre, is jointly funded by the Arts Council and UCC. It is designed to provide a film artist of distinction with a unique opportunity to develop their practice in a university environment, while offering students and staff of Film & Screen Media the opportunity to engage with a practising artist in a meaningful way during the course of their studies and wider cultural involvement in campus life.

Maximilian Le Cain is the ninth film artist to be appointed to the role and follows Carmel Winters, Gerry Stembridge, Hugh Travers, Mark O’Halloran, Pat Murphy, Alan Gilsenan, Tadhg O’Sullivan and Yvonne McDevitt who have enjoyed successful residencies at UCC since 2014.

The Signature of All Things

CORNELIUS BROWNE DISCUSSES THE ORIGINS OF ARTISTIC ANONYMITY.

Angelica Mashq

KIP ALIZADEH OUTLINES THEIR PARTICIPATION IN THE ACNI’S MINORITY ETHNIC ARTISTS MENTORING PROGRAMME.

MASHQ IS A visual art project focusing on how my queerness and Persian heritage intersect and overlap, explored through the mediums of mark-making and experimental publishing. I developed Mashq (2022) with the support of the Arts Council of Northern Ireland’s Minority Ethnic Artists Mentoring and Residency Programme, and with extensive guidance from my mentor Emma Wolf-Haugh. In making final outcomes that involved textiles and Persian calligraphy, I sought the advice of textile artist Emily Waszak, as well as fellow queer Persian visual artist Sahar Saki.

up before doing final pieces. However, over time, these practice sheets evolved into an artform of their own. The sheets feature words and letter forms that are repeated regardless of meaning, purely for compositional and aesthetic value.

OVERWINTERING IN A log cabin, through which wind whistles, everything I’ve painted during 2022 becomes strange to me. As I check drying progress, my everyday self seems miles removed from the painter. Early one morning, just out of bed after a night of storm, I race to see if the leaky roof is still intact. Relieved that my cabin stands, I am visited by the oddest sensation as I pick up a crooked board, upon which wildflowers sway in a summer breeze. Who painted this?

Decades hence, should any of my paintings resurface towards a human eye, this same question may be asked. From the faces of my pictures my signature is absent, although it does always hide somewhere behind the scenes. The reasons for this are manifold; a feeling of inferiority, worn like a second skin throughout my life, is possibly the root. My cousin, Dr Margaret Rose Cunningham, on International Women’s Day 2019, publicly advocated taking a Dr Martens boot to barriers. Maggie is a Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of Strathclyde and Editor-in-Chief of Pharmacology Matters magazine. She is an elected member of the RSE Young Academy of Scotland, and as a research scientist has won many awards, including the prestigious Winston Churchill Memorial Fellowship.

Originally, however, Maggie was an artist. Her secondary school years were punctuated by art retreats, and she secured an interview for Glasgow School of Art, which she decided not to attend. The reason, she told me, was that coming from Govanhill in Glasgow, she felt like an imposter. This is a commonplace experience among artists from working-class backgrounds, and one I share. It is only in middle age that I have felt confident enough to put my feet into barrier-defying boots.

So, there is the earthliness of oppression; however, I like to think there are also higher, brighter stars influencing my signature shyness. Heretical mystic Jakob Böhme, a shoe-

that the whole outward visible world is a signature, or figure of the inward spiritual world. Always, as a painter, I’ve had the sense of trying to reach something beyond the appearance of nature. Painting outdoors, I submit to the elements, relinquishing control and knowledge to such extent that certain works more truthfully bear the signatures of wind and rain. At most, I am co-painting with nature, developing a signature style for which I am merely the outward representative.

Böhme

Prior to Mashq, I had solely been an illustrator, mainly working in publishing. I have been illustrating picture books for young children for nearly ten years. Recent titles include: What Will You Be? / ¿Qué Serás? (written by Yamile Saied Mendez), Plenty of Hugs (written by Fran Manushkin) and World So Wide (written by Alison McGhee). I make my illustrations using a combination of traditional and digital methods, for example, pencil line work with colour added in Photoshop. This process evolved out of the need for my work to be easier to edit, when working with art directors and publishing teams to create final illustrations for books.

I began this project by using Persian poetry to explore the intersection of my queer and Persian identities through an anti-colonial lens. Then, through the embodied practice of abstract, gestural, expressive mark-making that instrumentalised Persian cultural practices like siyah mashq, I started to explore the ambiguity of existing as a queer person in the Iranian diaspora. Finally through a dialectical relationship with my mentor Emma Wolf-Haugh, I have explored various queer alternative publishing practices, such as zine-making and stickering, which express the subversiveness and imaginative possibility of being a queer Iranian person. I have drawn on the work of José Esteban Muñoz in Cruising Utopia, and Adrian Piper, specifically the essay ‘The Triple Negation of Colored Women Artists’1 in order to expand my thinking and language around my practice.

In a similar vein, Bard of Orkney, George Mackay Brown, reportedly avowed that the greatest ever poet is anonymous. Brown’s own poetry frequently lowers a bucket into the well of medieval art, native to the northernmost Scottish islands. Anonymity came as naturally as drinking water to artists of earlier times. A sense of humility may have stayed the signing hand of medieval artists, most of whom wore the robes of monks. Their artworks would have been used for liturgical, contemplative, or devotional purposes, so likely it would have seemed wrong for the artist’s name to be included in the image.

Of the poems, ballads, and folk songs composed outside monastic walls, Virginia Woolf ventured to guess that Anon, who wrote so many verses without signing them, was often a woman. As a painter of weather pictures, all my life I have loved weather poems. How amazing that the four lines of Western Wind have made their way to us across at least six centuries, without a name attached. Echoing Woolf, in the last months of his life, critic and poet Clive James guessed that it was written by a woman. Furthermore, he hazarded that she wasn’t the lady of a grand house. This anonymous poet was out there in the weather.

Cornelius Browne is a Donegal-based artist.

When making books, I create backgrounds, textures, and abstract marks using ink and graphite. In the summer of 2021, I started to create abstract zines and experimental standalone pieces using these materials. I was in an illustration rut and feeling uninspired, so it was a welcome change. I enjoyed this experimentation and felt I would like to broaden my practice along the lines of abstract mark-making. Therefore, with some encouragement, I decided to apply for visual arts funding. This necessitated a contextualisation of my experimentation, and so Mashq was born.

The title Mashq is taken from the Persian calligraphy practice of siyah mashq, which means ‘black practice’ and refers to calligraphic practice sheets that were originally used by Persian calligraphers to warm

One of the final outcomes of Mashq I’ve made is a denim jacket, which I consider a garment that correlates with my queer butch identity, decorated with siyah mashq style calligraphy. I feel in the performance of wearing it in the street – and therefore publishing a queer Persian identity to the world – the jacket “demands from viewers… the possibility of critical thinking and intervention.”2 In the future I would like to continue to explore the expansiveness of mark-making and publishing beyond traditional methods, do more large-scale mark-making, and more collaborative work.

Kip Alizadeh is an illustrator and visual artist living in Belfast.

1 Originally published in Next Generation: Southern Black Aesthetic (University of North Carolina, 1990).

2 José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (NYU Press, 2009) p 195.

Curatorial

Through Care, Towards Access

Curating in a Negative Spectrum

IARLAITH

NI FHEORAISINTRODUCES A NEW COLUMN SERIES ADDRESSING THE RADICAL POTENTIAL OF ACCESS IN THE ARTS.

THE LAST FEW years have been a highly visible moment for disabled and chronically ill artists in Ireland. However, visibility is a double-edged sword: on one hand, it focuses attention on work that has been ignored; but on the other hand, it plays into a shallow identity politics that allows concerns around access and labour conditions to go unchallenged. In my first column in this new series, I argue that we must move on from the narratives of depoliticised ‘care’ (utilised by many institutions) towards the radical potential of ‘access’.

Disabled and chronically ill artists have created the groundwork for how to make and show work accessibly, but that responsibility must now be taken on by the sector so that more people can access, make, participate in, and witness art. Otherwise, showing work by disabled and chronically ill artists will be a tokenistic affair that ignores the conditions of the people it claims to speak for.

Much of the current critical discourse on care is largely inspired by Black feminist, trans, and disabled writers and activists, who historically, have been systemically neglected or actively harmed by family and state. Writer and civil rights activist Audre Lorde famously stated that: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” This sentiment acknowledges that care is essential in the act of liberation but is also an essential part of achieving liberation. Conversely, artist Johanna Hedva claims that “not caring anymore” is liberating, when engaging with institutions, for whom the promise of ‘care’ and the fantasy of ‘healing’ has become a form of virtuesignaling. Through this tension, we can acknowledge the legacy of care and respect its political contexts, whilst understanding that art institutions are not the place where care can or should occur – and that institutions should concern themselves with ‘access’ instead.

A central methodology in accessible practice is making through disability, rather than about disability. A recent example in the Irish context is Sarah Browne’s film, Echoes Bones (2022), which saw the artist worked collaboratively with a group of autistic young people in North Dublin, in response to the work of Samuel Beckett. At its heart, the film is a portrait of a place which asks questions about representation. The two-year collaborative project began with watching films made by neurodiverse artists, such as Mel Baggs’s In My Language (2007), Sharif Persaud’s The Mask (2019), and Jess Thom’s Me, My Mouth and I (2018). This resulted in a project with and by neurodiverse people, made from a neurodiverse position, but not just about neurodiversity. The film foregrounds accessible ways of working that sidestep the tokenistic and exploitive value systems often at the

core of how these projects function. Importantly, the premiere of Echoes Bones at the Lighthouse Cinema, Dublin, in October 2022 was captioned, audio described, sensory friendly, and wheelchair accessible.

From a programming perspective, Chronic Collective at Pallas Projects, curated by Tara Carroll and Áine O’Hara, showed us how to centre disabled and chronically ill people in a learning environment. Their programme included workshops on performance, sickness and art, access riders, sound, and access in an artist-run organisation. As a programme that centred disabled and chronically ill audiences, access was at the core. This included everything from ISL interpretation of events, large print access statements, asking participants to wear a mask, and fostering a relaxed environment, which included a slow and flexible approach, allowing participants to move around, come and go, and make noise. Chronic Collective also asked attendees to fill out an access form beforehand, so they could try to accommodate a broad range of access needs. I would argue that such accessible programmes shouldn’t be the sole responsibility of disabled and chronically ill artists, but if we want to take care and access seriously, this is exactly how it should be done.

We also need to consider access in relation to the production of art. Some artists have access needs in making their work, which can include working with assistants or support workers. The Berlin-based Mexican artist, Manuel Solano, lost their sight in 2014 and has since worked with assistants to map out paint using pins and pipe cleaners, which they then paint over, using their fingers. This highlights the fact that questions of access arise long before the work arrives in a gallery, and that when planning an exhibition, curators must also consider the unique production needs of artists.

Many curators and organisations are eager to support disabled artists, audiences, and staff through access, but feel challenged by the limitations of funding, and the difficulty in finding the right advice. Through this new column series, I will detail how I work through access across various projects and contexts, including performances, exhibitions, festivals, learning programmes, and toolkits. I will expand upon ideas of working through disability, providing practical accounts of producing projects in accessible ways. These artists have shown us the way; it’s time to make access central in our work as curators, producers, organisations, and funders.

Iarlaith Ni Fheorais (she/her) is a curator and writer based between Ireland and the UK.

@iarlaith_nifheorais

MATT PACKER DISCUSSES THE HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL CURATORIAL INVITATION WITHIN IRELAND’S VISUAL ART SECTOR.

THE CELEBRATED CURATOR Germano Celant was one of several people who were bemused by, if not openly critical of, the invitation to adjudicate EVA in its early years. In his interview for the accompanying EVA ‘91 catalogue he described how he received EVA’s invitation by unsolicited fax; how he admired the invitation for being ‘very naive’, and how he accepted the decision as a ‘political gesture’ in favour of a poor country in Europe, rather than as an opportunity that would necessarily develop his curatorial profile. One of his initiatives that year was to reallocate funds for the restoration of an eighteenth-century painting by Richard Carver that was languishing in the Limerick City Gallery of Art collection.

Given the population of the country and the modest scale of its resources, Ireland has been a remarkably gregarious host to international curators since the 1960s. Some of the most significant large-scale visual arts events in its history – the ROSC exhibitions from 1967 to 1988, successive editions of EVA International (formerly ev+a) from 1979 to the present day, and major one-off projects such as Cork Caucus (2005) and Dublin Contemporary (2011) – have been led by a strategy of international curatorial appointment.

The reasons why might be located somewhere between Ireland’s ancient flair for hospitality, its open-spirited ambition for the visual arts to engage itself internationally, and the self-acknowledged limits of being able to achieve this in any structurally sustainable way. That, and Ireland’s deep love of curators, of course. Perhaps it was (and still is) simpler and more graspable to invite successive international curators to Ireland, than to conjure the new institutions and resource frameworks required to foster the same desired levels of internationalisation on home soil.

It is significant that Ireland’s hosting of international curators has operated from a legacy of underdevelopment in its visual arts infrastructure. Of the examples of large-scale visual arts events cited above, all were founded with a diagnosis of gaps and deficiencies in Ireland’s resources and reputation, to which the appointment of an international curator came to represent a temporary reprieve.

The architect Michael Scott, who founded the seminal ROSC exhibitions, famously deplored “the absence of an enlightened museum of modern art in Ireland” before appointing a jury of three international curators (James Johnson Sweeney, Jean Leymarie, and Willem Sandberg) to select artworks for its inaugural edition. Scott went on to say that “[u]ntil such an institution was established, there was a need to periodically bring developments in the visual arts in the wider world to the attention of the Irish public and the artistic community.”

In Cork, several decades later, Tara Byrne (then Director of The National Sculpture Factory) introduced her vision for Cork Caucus – perhaps one of the most important infrastructural experiments to take place within an Irish visual arts context this side of the millennium. The event had the explicit aim to “improve and develop the conditions of critical artmaking in Cork.” Charles Esche (Director, Van Abbemuseum) and Annie Fletcher (then a freelance curator based in the Netherlands) were invited to devise its programme, together with local curatorial partners, Art / not Art (David Dobz O’Brien and Fergal Gaynor).

In 2010, ill-fatedly announcing itself on e-flux, Dublin Contemporary described its ambition of “putting Dublin on the map as an international art destination… drawing on the expertise” of high-profile international curators appointed to the advisory committee, from Hans Ulrich Obrist to Okwui Enwezor. Today, EVA International – the organisation of which I am the Director – continues to operate from its founding statement to “provide the public with an opportunity to visit and experience an exhibition not normally available in the region and […] to stimulate an awareness of the visual arts here”, that has been co-extensive within an almost unbroken history of inviting international curators to adjudicate or curate successive editions.

Across a span of 50 years, the terms of invitation to international curators have been predicated on a negative spectrum of opportunity – whether addressing the absence of an enlightened museum (ROSC), or the need to improve and develop the conditions of critical artmaking (Cork Caucus), or to direct an awareness that was apparently lacking (Dublin Contemporary / EVA). While some of the inflammatory emphasis in the founding language of these events was undoubtably shaped by funding mandates and levelling up-style policy agendas, it carries the consequential risk of establishing a thought pattern of how we imagine future development for the visual arts and the role of curating within it.

Firstly, it risks disincentivising structural change by reinforcing and reproducing our sense of negative capability, plastering over the gaps with curatorial and programmatic outputs. Secondly, it risks creating a positivist and interventionist imperative upon curatorial practice. None of this is inevitable. Nor was it ever. We can either look back at a history of international curatorship in Ireland and see a shadow history of Ireland’s disadvantage and deficit; or we can look forward to ways of working with curators, in and out of Ireland, that are predicated on wants rather than needs

Matt Packer is Director of EVA International eva.ie

Curatorial Seminar We Need to Talk About Painting

Practical Magic

‘PRACTICAL MAGIC’ IS the 12th iteration of Pallas Project/Studios’ annual exhibition, ‘Periodical Review’. Each year, Pallas directors, Gavin Murphy and Mark Cullen, invite two peers to consider the artworks, practices, exhibitions, projects, events, artistic and community initiatives, collaborations, publications and performances encountered in the previous 12 months. The four selectors then nominate the works that stood out for them during the year, and these are whittled down via an editorial process to five selections each, giving a total of 20 artworks. This process of four selectors with subjective viewpoints and positions, choosing work independently of each other, can lead to a show with a feeling of the ‘exquisite corpse’ about it. This format has its challenges but also allows for instinctive and surprisingly rich narrative connections to develop between the work, without the pressure of having to conform to a strict overarching curatorial theme. ‘Periodical Review’ is loosely designed to suggest a magazine-like layout, and in this sense, the spaces between works and the edits are clear.

After an intense period of inaction and online interaction, 2022 saw an overdue abundance of exhibitions and events happening throughout the country. So, when Basic Space were asked to co-select this year’s ‘Periodical Review’, we approached this artistic bounty with a renewed intensity. For a few years, our lives shrank right down to the essential and the local, and since then, an increase in artistic practices focusing on the internal have flourished. The domestic and the corporal weave their way through the show, from soft pastels to shiny entrails. The multitude of crises that are at the forefront of the current global condition are also tackled head on. A selection of photographs from the now destroyed city of Mariupol in Ukraine, from the group TU Platform, is a particularly harrowing point in the show. In separate pieces, Cold War-era radios broadcast an imagined, but very likely climate catastrophe, and a cocoon of old family photos and sounds draw the viewer in, with nostalgia

being felt, both physically and spectrally throughout the gallery.

Striking palettes, aesthetics and ideas that lean towards the gothic enliven the space and lend a sense of unease: a punk Sheela na Gig and a silver tipped bean chaointe (or keening woman) sit across from each other; leather clad hands perform an unboxing video with feelings of the burlesque and the absurd, as box after surprising box are unveiled on a loop. Time and space are traversed in multicolour, from explorations of the conditions of Indian textile workers, to the recounting of past personal traumas. The walls are postered with monthly newsletters from an active community brimming with self-organised movement, ensuring the show is not without hope or humour – the essential strands that unify us and which we will need in abundance to survive and organise in the years ahead.

The contributors and artworks for ‘Periodical Review 12’ are: Kevin Atherton, Cecilia Bullo, Myrid Carten, Ruth Clinton & Niamh Moriarty, Tom dePaor, The Ecliptic Newsletter, Eireann and I, Patrick Graham, Aoibheann Greenan, Kerry Guinan & Anthony O’Connor, Camilla Hanney, Léann Herlihy, Gillian Lawler, Michelle Malone, Thais Muniz, Ciarán Ó Dochartaigh, Venus Patel, Claire Prouvost, Christopher Steenson, and TU Platform.

The invited selector’s this year were Julia Moustacchi and myself as co-directors of Basic Space – an independent voluntary art organisation founded in 2010, which has programmed educational events, residencies, events and exhibitions, primarily working with emerging and early-career practitioners. The majority of projects are hosted or organised in collaboration with external institutions, where Basic Space acts as a critical force, challenging attitudes and policy and promoting a representative and inclusive framework.

Siobhán Mooney is an independent curator and co-director at Basic Space. basicspace.ie

KAREN EBBS REPORTS ON A SERIES OF TALKS THAT SHE RECENTLY ORGANISED AND CO-HOSTED AT IMMA AND THE COMPLEX.

LAST JUNE I began to explore the possibility of initiating and organising a talk series dedicated to painting. My idea was enthusiastically received, and, in the literal sense, doors opened when Lisa Moran (Curator of Engagements and Learning at IMMA) granted the use of IMMA’s Lecture Room. A series of educational talks, titled ‘We Need to Talk About Painting’, was supported by NCAD’s Painting Department and was hosted by myself and fellow MFA painting students, Cian McLoughlin and Caitlyn Rooke.

The purpose of these discursive events was to illuminate debate and new thinking surrounding painting practice, its educational context, its relation to the broader spheres of art, and its contemporary theoretical development. There was huge public interest, with each talk fully booked out within a week of being advertised. These invigorating and critical discussions attracted a far-reaching audience, with many attendees requesting that these talks be held on a regular basis. It is very clear that there is a community of critically minded artists, educators, curators, and art lovers, who have an appetite for live, open conversation and debate.

The talks were held on 27 October, 3 November, and 24 November 2022. The invited speakers were Mark O’Kelly (artist and Head of the Painting Department at NCAD), Colin Martin (artist, Head of the RHA School, and Lecturer at NCAD), Christina Kennedy (Senior Curator at IMMA), Beth O’Halloran (artist, Head of MFA Programme at NCAD), Mark Garry (artist, Lecturer TU Dublin), Donal Moloney (artist, Lecturer at MTU Crawford), and artists Isabel Nolan and Dominique Crowley.

At the invitation stage, I presented each speaker with a brief, which set out the talking points (listed below), which were explored and expanded upon throughout the events, elucidating core contemporary areas of inquiry from their informed perspectives, while simultaneously illuminating historical, contextual links. Each person spoke for 20 minutes, followed by a discussion, prompted by questions from myself, Caitlyn Rooke, Cian McLoughlin, and audience members.

Talking Points:

1.

Painting is not currently buckling under the weight of historical reference, nor is it bucking trends in an effort to create a ‘new movement’. So, what is painting’s current position in a contemporary context? What actually constitutes painting, which can be regarded as an action, an object and medium of consideration? Is there a revival of interest in and a revisiting of some of the ‘healthier’ concerns of modernism such as, for example, the formal elements in painting?

2. The importance of research in painting. Research has many categories, from academic and specialised areas of interest, to observational, material, process-based, and experiential examinations of the lived experience. What does research mean, how can it add layers of interest for the viewer, and how can it nourish an art practice?

3. When it comes to how painting is taught, teaching practices vary, with colleges and institutions adopting a breadth or depth of approach to facilitate specialist or non-specialist focus. The focus shifts along a scale from skills-based/technical accomplishment, to open interest-driven approaches with broad exposure to a variety of media. Could worldviews on diversity be driving a growing demand for agency and autonomy where painting is concerned? Shifting perceptions in colleges and institutions – regarding skills-acquisition and observational practices – are already paving a less prescriptive, middle path, to work in tandem with contemporary approaches to painting. Where this is the case, is it even possible to teach painting? If painting is recognised as an evolving overarching means of exploration and inquiry, does the question of how it is taught become a completely separate issue, guided by the needs of the artist/student?

4. In contemporary life, we are bombarded by a tsunami of technologically mediated imagery. Apart from painting’s own specificity, it has the capacity to absorb a digitally mediated world, the proliferation of images, and our increasingly virtual existence. Painting is resilient, adaptable and versatile and we believe that the current challenging environment presents huge opportunities in the evolution of painting. As embodied beings, we humans need physical interaction. Could painting’s continued allure be its directness, its accessible and unmediated relationship to the physical body, to materiality and to sense perception?

‘We Need to Talk About Painting’ served to highlight an appetite for discourse and debate on the subject of painting. These talks will be disseminated as online recordings and as a form of publication.

@karen.ebbsSIOBHÁN MOONEY OUTLINES THE 12TH ITERATION OF PERIODICAL REVIEW AT PALLAS PROJECT/STUDIOS.Karen Ebbs is a Dublin-based painter who is currently studying for an MFA at NCAD. Venus Patel, Eggshells 2022, experimental short film; image courtesy the artist and Pallas Projects/ Studios.

The Kerr Shoe Collection

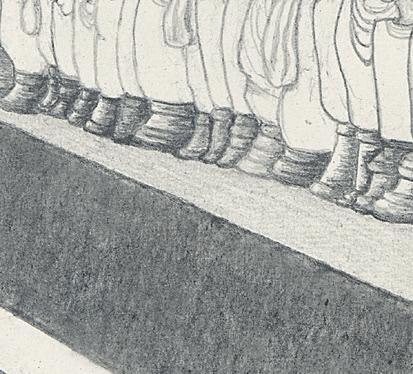

WHILE THE NATIONAL Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) is predominately paper based, you might be surprised to learn that we have approximately 1,300 pairs of shoes! You may agree the staff in NIVAL are a fashion-conscious lot; however, these are not our shoes.

Housed in a room to themselves, these shoes are stacked on shelves from floor to ceiling. They are all stored in their original, individual boxes, which in turn provide fascinating examples of design, advertising trends, and styles. There is a feeling of time travel as NIVAL staff linger in the quiet space, peeping into the shoeboxes. Sensible school shoes, remembered from childhood, contrast with the vibrantly coloured, polyester, faux fur trimmed slippers, so popular in the 1980s. From pumps to iconic platforms, these once common examples of footwear are now rare historical artefacts. High heels, wingtips, and sandals demonstrate in a very real and tangible way, the myriad of talent and graft of the skilled practitioners.

Donated to the archive by artist Dr Helen McAllister and textile artist Millie Cullivan ANCAD, this collection originated from the Kerr Family shoe shop business, based in Mohill, County Leitrim. The shop was opened in 1956 and closed in the mid-90s, retaining shoes from across this 40-year time span. Not only is this an extensive collection but significantly, the vast majority of the shoes are Irish made, with a substantial amount manufactured in Leitrim and the surrounding counties. This is testament to the flourishing industry of shoe and shoe-related products that have since, essentially, disappeared in Ireland. The Kerr Shoe Collection is an important record of an indigenous manufacturing industry, which included shoe designers, networks for production, marketing, distribution, and graphic designers to create

attractive packaging and logos. Put simply, this archive reflects a vital social record, showing Irish fashion trends and societal norms over four decades.

Supporting this collection are a number of related articles and books kept in NIVAL. Visitors are welcome to book an appointment to study these books, files, and ephemera in our Reading Room, while books from the Edward Murphy Library are available for loan to members of the library.

One example is David Shaw-Smith’s 1979 documentary, Tutty’s Shoes, focusing on the famous artisan shoemaker, Tutty’s of Naas, who made hand-lasted shoes by measuring the foot, building up the wooden last, and completing the shoe. Other resources include Shaw-Smith’s book, Traditional Crafts of Ireland (Thames and Hudson, 1984), and a chapter titled ‘Shoemakers’ in Kevin Corrigan Kearns’s book, Dublin’s Vanishing Craftsmen (Appletree Press, 1986).

The Kerr Family was keen to find a future role for the shop’s contents. With the help of Mervyn Kerr, Helen McAllister, and Millie Cullivan, they catalogued, photographed, and created an archive of approximately 1,300 shoe models. Where possible, two of each shoe styles were taken, with one set going to NIVAL. The Kerr Shoe Collection was deposited to NIVAL by Helen McAllister in 2017.

Eve Parnell is Artists Database Editor/ Library Assistant at NIVAL. nival.ieArtist Supports

Direct Support

ELIDA MAIQUES OUTLINES HER PARTICIPATION IN MERMAID ART CENTRE’S TRANSFORM ASSOCIATE ARTIST SCHEME.

THE FOUR TRANSFORM Associate Artists 2022/23 at the Mermaid Arts Centre in Bray are writer and printmaker Shiva R. Joyce, theatre director and writer Chris Moran, actor and playwright Emmet Kirwan, and I. Three of us are Wicklow-based, while Shiva is resolutely nomadic, sometimes based in Cork. Funded by the Arts Council, TRANSFORM is a direct support scheme for artists. Each artist is hired to work on a part-time basis, 20 hours per week for one year. What we are required to do is simply to work in a self-directed way on our current art practice.

Care and thought have been put into hiring a group of artists from different disciplines, cultures, age groups, social conditions, and backgrounds. Everybody is busy, but we try to meet weekly or biweekly with artistic director Julie Kelleher or curator Anne Mullee. Our conversations include banter, troubleshooting, peer support, housekeeping, and a reading club. They seem to be pollen-rich: fresh projects are coming out of this already. The emphasis on collective wellbeing, while delivering a strong arts programme for Wicklow, is real and authentic.

To the scheme I bring my art practice, which in the last decade has expanded from drawing. Exploring the boundaries of drawing and comics, I have initiated collaborations with dancers and musicians. In 2015, a series of botanical drawings evolved into a long-term project, I Am a Forest, which includes seed-gathering, tree propagation, and wildlife art workshops with community groups such as local schools and the community planting project, Edible Bray.

TRANSFORM has supported me to pursue film festival distribution of the

short, I Am a Forest (2022). A direct result is its premiere in the Official Selection of the Morelia Film Festival in Mexico, one of the most important film festivals in Latin America.

Since 1999 I have run informal drawing and comics sessions; its current iteration is called ‘Fridayfest’, a drop-in drawing and writing session at the Mermaid. It is open to all, from the seasoned to the pencil-fearing. This relaxed session weaves conversation, drawing, writing, thought, and giggles. Drawing in company is one of the pleasures of life.

‘The Community Seed Ark’ is another project I am involved in. When the project’s initiator, artist Aga Kowalska, moved overseas, Bray Library invited me to become their Seed Librarian. Increasingly methodical about seed-saving, I am curating and keeping a community seed ark (vegetables, wildflowers, and garden flowers). People borrow seeds from Bray Library, grow plants and collect their seeds, returning some of them to the library.

The use of the word ‘transform’ for this Mermaid Ars Centre funding scheme is intentional and meaningful. It is transformative by supporting collaborations, research, travel, workshops, study time, and in generating opportunities for artists through direct economic support and trust. I find it also supports the communities around the artist, as we have the time and headspace to dedicate to them. The impact of art making cannot be underestimated, but it can be funded and carefully supported.

Elida Maiques is a Spanish-born (Guatemalan-Valencian) visual artist residing in Wicklow.

Casa Dipinta

BRENDA MOORE-MCCANN DISCUSSES THE ITALIAN TOWNHOUSE OWNED BY BARBARA NOVAK AND BRIAN O’DOHERTY.THE RECENT DEATH of renowned artist Brian O’Doherty (1928-2022) (a.k.a. Patrick Ireland 1972-2008) will inevitably lead to more in-depth assessments of his spectacular range of work as an artist, critic, arts administrator, editor, and writer, which contributed so much to Irish and international contemporary art. While Portrait of Marcel Duchamp (1967) and conceptual exhibition Aspen 5+6 (1967), as well as Patrick Ireland’s Name Change performance (1972) and environmental Rope Drawing installations are very well known, an evolving artwork in Italy for the past fifty years, is less so. Casa Dipinta (meaning ‘painted house’) is an eighteenth-century house, tucked away in the medieval town of Todi, Umbria, which the artist and his wife, art historian and painter, Barbara Novak, have owned since the mid-1970s. Over succeeding decades, O’Doherty/ Ireland gradually transformed the house into a unique artwork. Opened to the public as a museum a few years ago, it now ranks as one of Todi’s most popular sites with locals and tourists.

I first stayed in Casa Dipinta at the invitation of the artist and his wife in 1998, while on a research trip about O’Doherty/Ireland’s art. Many engaging conversations took place over breakfast of toast and truffle paste. This was followed since then by many other visits, which allowed first-hand observation of the organic way in which the house changed, as a new wall was painted, repainted or, sometimes, obliterated. While Novak initially wanted to keep the “white, silent, walls” she eventually relented. Beginning in 1977, O’Doherty/Ireland began to paint the house in a dazzling array of colours and linear configurations, all of which related, I discovered, to abiding concerns within his art.

In the late 1960s, language, specifically the extinct Celtic language of Ogham (c. 2nd, 3rd -7th A.D.) dominated O’Doherty’s conceptual art, and sometimes Ireland’s signature three-dimensional Rope Drawing installations. Both are found at different levels of Casa Dipinta. In the context of his Minimalist-Conceptual background, the artist reduced his artistic vocabulary to Ogham vowels – “the horizon of language” – and the triad of Ogham-translated words ONE, HERE, NOW. These dominate the ground floor alongside another constant concern, that of the self and other. This is found in painted panels of Ogham lines that address the viewer with ‘I’(IIIII) and ‘U’/You’(III). In others, the vowel ‘I’ alone dances across a gridded blue panel or in Dictionary of I in which it is depicted in a variety of configurations with the visual symbol of identity, the hand. Gradually, pristine white walls were replaced by walls that whispered vowels and the words ONE, HERE, NOW on separate panels throughout the first and second floors.

Importantly, as each level of the three-storey house was transformed into an artwork, daily life continued within. Simple, modest furniture, in stark contrast to the vibrantly coloured walls, clearly removed this house/ museum from that which O’Doherty had so cogently critiqued in the acclaimed essays, ‘Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space’ around the same time. Instead of the white cube’s quasi-religious, transcendental space, this was a lived-in space accompanied by the constant sounds of the surrounding city. The presence of the artist and his wife is strongly felt, not least by half-finished and full-length portraits in different parts of the house. Like Schwitters’ Merzbau (c. 1923-37), the house became altered from within. But in contrast to Merzbau’s ever changing collage of found objects, Casa Dipinta was transformed using house paint that became part of the architecture itself.

Yet, like Merzbau, it also became a non-static, living environment that constantly changed.

Barbara Novak insisted, since a large part of his work was ephemeral, that Casa Dipinta would be a place where key works of O’Doherty/Ireland’s art would eventually be on permanent display. The mural, One, Here, Now: The Ogham Cycle (1996, restored 2018) at Sirius Arts Centre in Cobh, County Cork, is the only other permanent work open to the public (and dedicated to the Irish people in 1996). While important for this reason, Casa Dipinta does not, however, represent the full range of O’Doherty’s art, such as the large series of Ogham drawings on paper, Ogham wall sculptures, objects, chess-works, artist’s books, language plays, and labyrinths.

The art and culture of Italy informs the first-floor living room in the form of a single rope drawing, Trecento. Its painted triangular shape, a secular echo of the numerous pedimented roadside altars dotted around Umbria, is accompanied by rope lines that stretch out into the room where the viewer can find the spot where rope and painted configuration align momentarily. There are also Ogham NOW and HERE paintings on this floor that incorporate anomalies of architecture (seen in many Italian frescos), such as for example, in the NOW panel where a pre-existing oculus in the

wall becomes part of the work, while the HERE panel incorporates the entrance to a deep stairwell leading to the kitchen below. An Ogham Song of the Vowels painting lies opposite the stairwell.

There is no Ogham on the upper bedroom floor. This calm predominantly blue room is dominated by the theme of inside and outside with its painted shuttered windows revealing an Italianate cycle of the times of day. In a corner, the theme is carried further with a double door rope drawing, a contemporary nod to Duchamp’s 11, Rue Larrey (1927).

The next phase of this unique museum, with its rich library of art books donated by the artist and his wife, will be an artist’s retreat and a valuable resource for artists and scholars in the future. Thus, this anti-white cube museum will allow art and life to continue to live side-by-side as intended by O’Doherty and Novak. The house was recently given to the people of Todi by the couple.

The Space to Grow

FOR 40 YEARS, Temple Bar Gallery + Studios (TBG+S) has been a bedrock for artists in Dublin. In this article, we hear from five of our current studio artists, who consider what TBG+S means to them personally. We praise all who made TBG+S happen in the first instance and wish to thank all who have contributed to the organisation over its 40-year history to make it such a special place – this includes over 500 Irish and international artists, as well as everyone who has worked here, every board member, all funders, and audiences.

It has meant a great deal to me to be a part of Temple Bar Gallery + Studios over the past few years. Being here has given me the security, freedom, continuous support, and attention that an artist requires to sustain their practice. This has had a significant and positive impact on my work. The appeal of a secluded artist residency is the opportunity to escape everyday life and focus on making. Outside of this context, I never would have thought it possible to find the optimum artmaking conditions of tranquillity, peace, and pragmatic focus. TBG+S provides all of this, not only in the midst of everyday life, but right in the bustling heart of Dublin, near many other major cultural institutions and organisations. TBG+S facilitates a community of artist peers to share ideas and inspire each other. One of the most unique experiences in a residency is watching projects by other artists develop over the same timeframe as your own. As spectators, we normally experience artworks in their final state of completion. Yet there is something inspiring about stepping into an artist’s studio and contemplating

their work unfolding. My favourite part of artmaking is seeing uncertainty fade as ideas begin to solidify. It is a privilege to share this process as a member of one of Ireland’s major artist studios.

Atoosa Pour Hosseini is a Three-Year Membership Studio artist at TBG+S and will present a solo exhibition in the gallery in October 2023.

Being the recipient of the TBG+S Recent Graduate Award has been transformative. Sharing a space with a strong community of artists has given me confidence and a sense of solidarity – as well as confirmation that the path I’ve chosen to take is the right one. Learning through studio visits and informal conversations in the corridors, I benefit enormously from the support and feedback of other members. It has helped me re-imagine how I see my practice. It has encouraged the expansion of my work – off the screen onto the walls, in the form of large-scale images – which I hope will help to sustain my practice into the future. Having studied in IADT and living in the suburbs, a studio space in Dublin’s city centre connects me to the heart of the city and its artistic energy for the first time. Despite the noise from buskers and tourists, I enjoy the immediacy and vibrancy. As an emerging, working-class artist, I am very aware of the critical lack of affordable studio space and its impact on emerging and established artists. In this climate, the continuance of established, resourced, purpose-built studios like TBG+S is all the more important. Happy Birthday!

Every morning I leave the street and enter a lift which floats me up to an enchanted greenhouse that is the top floor of Temple Bar Gallery + Studios. Pushing back any giant leaves guarding my door, I feel as lucky as Jack in the fairy tale, when he finds the giant’s castle at the top of the beanstalk. TBG+S is unique because of the people who make it so. The team work incredibly hard to create a dynamic exhibition programme, while also providing immeasurable studio support to artist members. It is not just a material resource but an imaginative enterprise that expands on contemporary art themes of social engagement and community. They do this both inside and outside the gallery space. TBG+S was founded in the 1980s and unfortunately there has been nothing quite like it built in Dublin since. Purpose-built studios for artists in Ireland are in extremely short in supply. I have been exceptionally lucky to have a space in TBG+S. Artists need publicly funded spaces to allow them to rise above the constraints and grinding costs of living. I really hope the government’s promised plans for more studio spaces will build the magic castles that artists need right now.

Painting is a mostly solitary activity, and the necessary solitude and constancy to undertake this form of practice can be found in a studio. The messy materials and processes of painting can be left to stew there, and the changes, experiments and transformations can be observed – brought to boil or cool off – over daily visits to the studio. The process of blending liquid substances into solid form, while attending to the meaning of images in a changing world, is enough to drive one crazy, but the solidarity of knowing that others are engaged in similar pursuits in adjacent studios might be enough to keep one sane. I have had a studio in Temple Bar Gallery + Studios since it was established as a workspace for artists by Jenny Haughton in 1983. Previously, I had a studio on Ormond Quay, where I lived at the time. As a committed city dweller, the move across the river was very convenient and the advantage of joining

a community of artists was as much about opening up to new horizons, as about nourishing an existing practice. TBG+S has survived many trials over its 40-year existence and succeeds in consistently allowing artists the space to grow.

Robert Armstrong is a founder member at TBG+S.

I worked in a small, converted shed for eight years. It was useful because as an artist, part-time lecturer, and parent of a young child, I was able to snatch studio time at night and during short school hours. The space was tiny with very low ceilings; I longed for a room that didn’t also have the washing in it. When I moved back into TBG+S (I’d had a stint here 2009-12) it coincided with a career break from TU Dublin. Newly isolated from my academic colleagues, I was so grateful to be working again in a community, alongside other artists. This is a strange life to choose, and it helps to have companionship along the way. My practice shifted again, almost immediately. I have been able to expand my materials, experiment with scale and form, and allow for compositions of objects to shift, reconfigure and evolve. In the depths of the pandemic, for the Ireland at Venice project, Clíodhna Shaffrey, Michael Hill and I considered the nature of the studio. It is a space that is more important to some artists than others –but in pitching to show work in Venice, we wanted to highlight the role of TBG+S, of all ‘good studios’, in cultivating and facilitating practices that necessitate a fashioning of forms, a thinking through making. I will miss my beautiful, life-changing room so much.

Niamh O’Malley is a Three-Year Membership Studio artist at TBG+S. She represented Ireland at the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022, with a solo exhibition titled ‘Gather’, which was curated by the TBG+S Curatorial Team.

Established by artists in 1983, Temple Bar Gallery + Studios was one of the first DIY artist-led initiatives in Ireland. TBG+S was founded by Jenny Haughton (Founding Director) and a group of artists, who occupied and rented a disused shirt factory from Córas Iompair Éireann (CIE). As well as studios, the building housed an exhibition space, cafe, sculptor’s annex, and a print studio, influencing the atmosphere of Temple Bar in the 1980s and establishing the area’s reputation as a cultural hub. It was one of the first cultural organisations rehoused by the Temple Bar Cultural Quarter regeneration.

templebargallery.com

Ireland’s St. Ives

MARTINA O’BYRNE OUTLINES THE EVOLUTION AND ASPIRATIONS OF ARTFORM SCHOOL OF ART IN DUNMORE EAST IN WATERFORD.

OVER THE LAST few years, the unique character of the seaside village of Dunmore East in County Waterford – with its red cliffs, strands, and coves – has been enhanced further by the creative presence of Artform School of Art. On a visit, you might find plein air artists, led by Dave West, working on Lawlor’s Strand; or a group of watercolourists having a lunch with John Short on the terrace of The Strand Inn overlooking Hook Lighthouse, in lively conversation with the inn’s owner and co-founder of Artform, Clifden Foyle. Around the corner at Artform, in a modern, spacious, lightfilled studio, Bridget Flannery could be showing artists her summer sketchbooks; Michael Wann could be introducing the medium of charcoal through some drawing exercises; or indeed Eamon Colman could be reading a poem to the artists before they experiment with pigment during his masterclass on colour.

Following a very successful pop-up art exhibition in December 2017, in a beautiful historical building at 44 The Quay, Waterford, Clifden Foyle and I established Artform School of Art. While the Annual 44 exhibition went on to become an important yearly event, the art school project, under the corporate governance of Clifden’s family hospitality business, brought together the Foyle family’s passion for art and long-standing support for artists, with our unique artistic, technical, and organisational skillset.

When Artform studio doors reopened after the pandemic, we ran several vibrant seasons with courses hosted by many excellent artists mentors. This included P.J. Lynch (still life, portrait and figure drawing, and painting in charcoal and oils); Tony Robinson (plein air in oils, portrait in oils alla prima); Julie Cusack, Bridget Flannery (abstracting the landscape in mixed media); Maurice Quillinan (sampling in international painting); Mary O’Connor (abstraction; silk screen printing); Aidan Crotty (painting from observation); Gabhann Dunne (painting between representation and abstraction); Shevaun Doherty (botanical painting in watercolours); Steve Browning (plein air in acrylics); Sheila Naughton (experimental drawing); Daniel Lipstein (traditional printmaking techniques); Neal Greig (landscape in oils and charcoal); Zsolt Basti and Salvatore of Lucan (combined course on double portraits, composition and painting); Brian Smyth (copying old masters); Mick O’Dea (working from life in any medium), and others.