VAN The Visual Artists’ News Sheet A Visual Artists Ireland PublicationIssue 6: November – December 2022 R E C O N S T R U C T I N G M O N D R I A N J O H N B E A T T I E 1 F E B R U A R Y 2 0 2 3 6 A U G U S T 2 0 2 3 Inside This Issue CHRONIC COLLECTIVE THE ECO SHOWBOAT RON MUECK AT THE MAC REGIONAL FOCUS: GALWAY

On The Cover

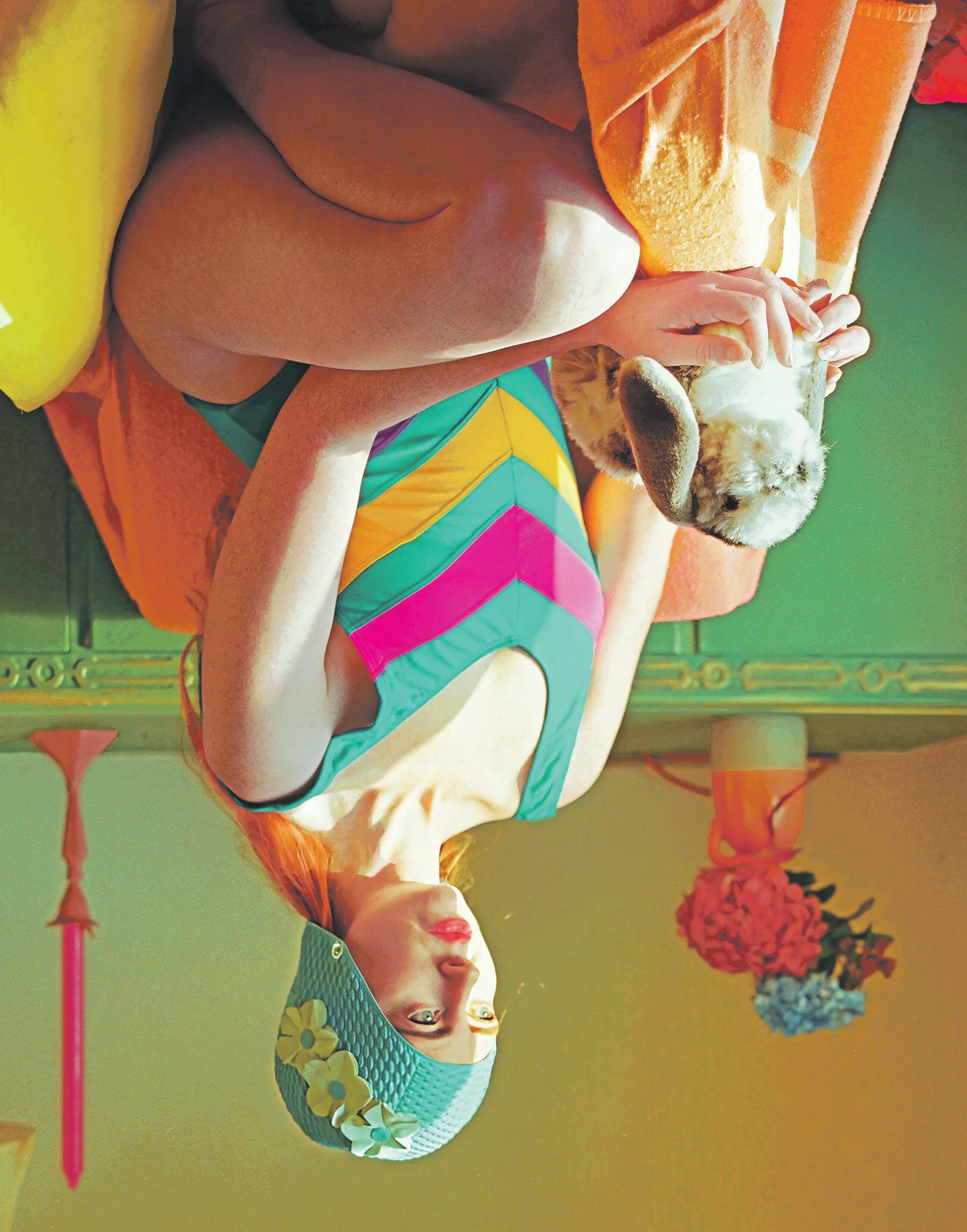

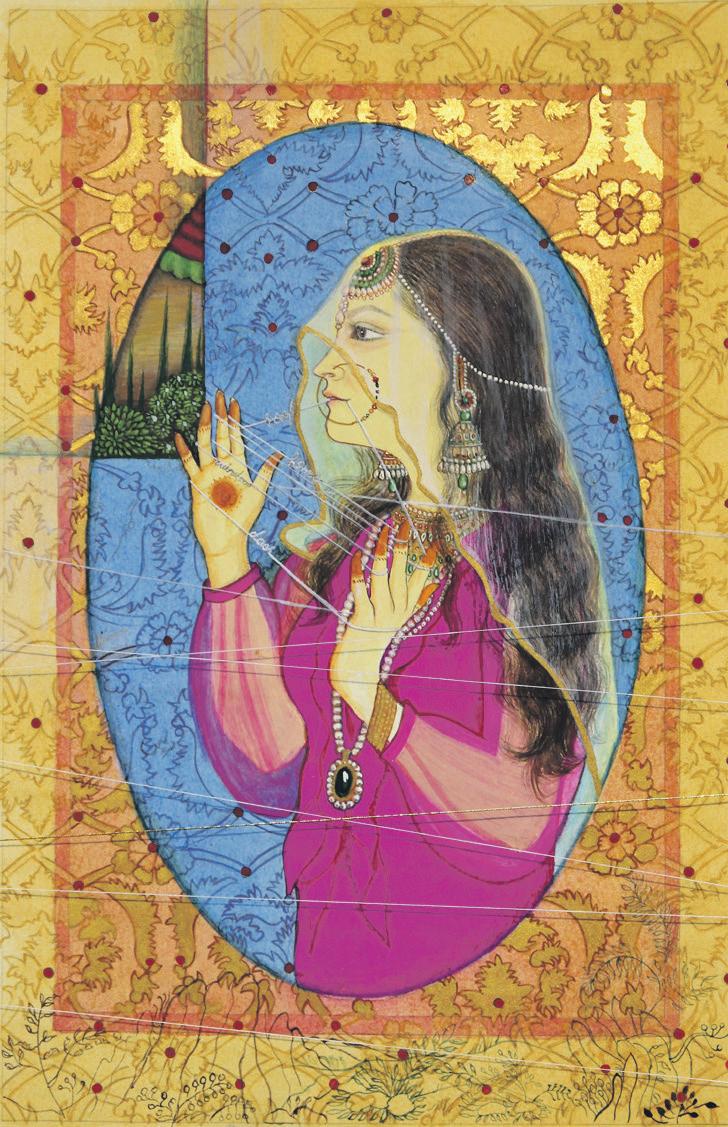

Enda Burke, Deirdre by the Window, 2021, photograph; image courtesy of the artist.

First Pages

6. Roundup. Exhibitions and events from the past two months.

8. News. The latest developments in the arts sector.

Columns

9. Sea Interludes. Cornelius Browne considers the sea as an omnipresent force in the work of Donegal painters. Reflections on a Radical Plot. Clodagh Emoe chronicles the evolution of a long-running ecological project at IMMA.

10. Chronic Collective. Tara Carroll and Áine O’Hara discuss the art collective and their advocacy for improved accessibility. Oh Infamy. Iarlaith Ni Fheorais discusses a new film.

11. Making Change Happen. The Arts Council’s EDI toolkit. Reflections on Making. Pauline Keena’s residency at BAG.

Regional Focus

12. Civic Contribution. Megs Morley, Director, GAC.

13. Engage Art Studios. Rita McMahon, Managing Director. Evolution of Artist-Run. Lindsay Merlihan, Director, 126.

14. New Directions. Kate Howard, Galway City Council. Full Steam Ahead. Anne Marie Deacy, Visual Artist.

15. Galway: A Suburban Perspective. Hilary Morley, Visual Artist. Rainy Metropolis of Ambition. Enda Burke, Visual Artist.

Ecologies

16. Eco Showboat. Cleary Connolly outline their recent tour of Irish waterways to raise awareness about climate change. Land-made. Padraig Cunningham outlines his contributions to the Eco Showboat Shannon expedition this summer.

17. Mesocosm. Christine Mackey assembles a glossary of key terms pertinent to her Eco Showboat research and project.

Art Publishing

18. The Story of Art Without Men. Varvara Keidan Shavrova reviews a new book, published by Hutchinson Heinemann.

Critique

19. Eleanor McCaughey, Learning to smell the smoke, 2022. 20. ‘Bones in the Attic’ at Hugh Lane Gallery.

21. Eithne Jordan at Highlanes Gallery. 22. Michelle Malone at The LAB.

23. Caoimhe McGuckin at Riverbank Arts Centre. 24. ‘Braid’ at Lord Mayors Pavilion.

Exhibition Profile

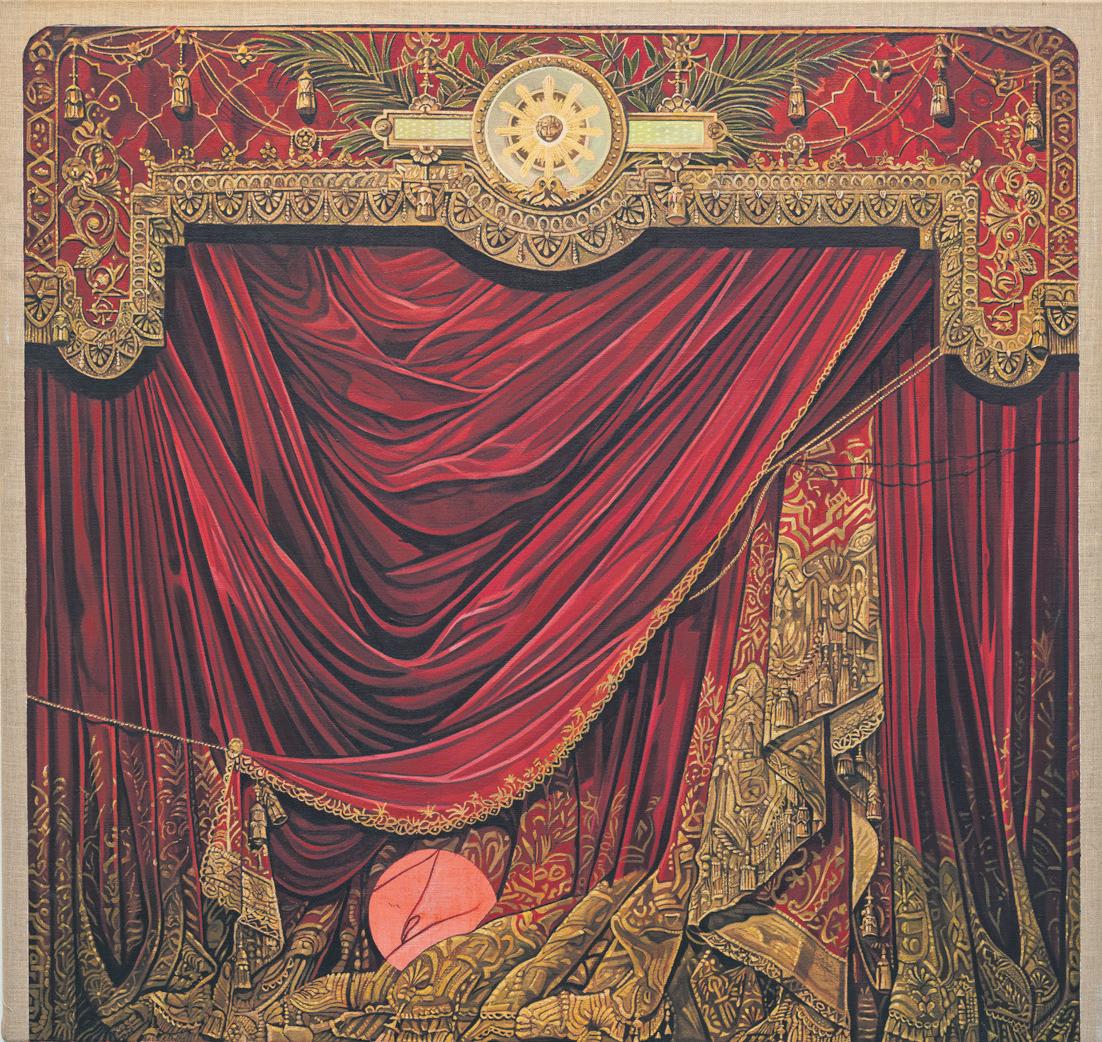

26. Unseen. Nick Miller interviews Philip Moss about his painting practice and recent exhibition at the RCC in Letterkenny. 28. To Ashes. Maximilian Le Cain reviews Evgeniya Martirosyan’s recent solo exhibition, ‘To Ashes’, at GOMA Waterford.

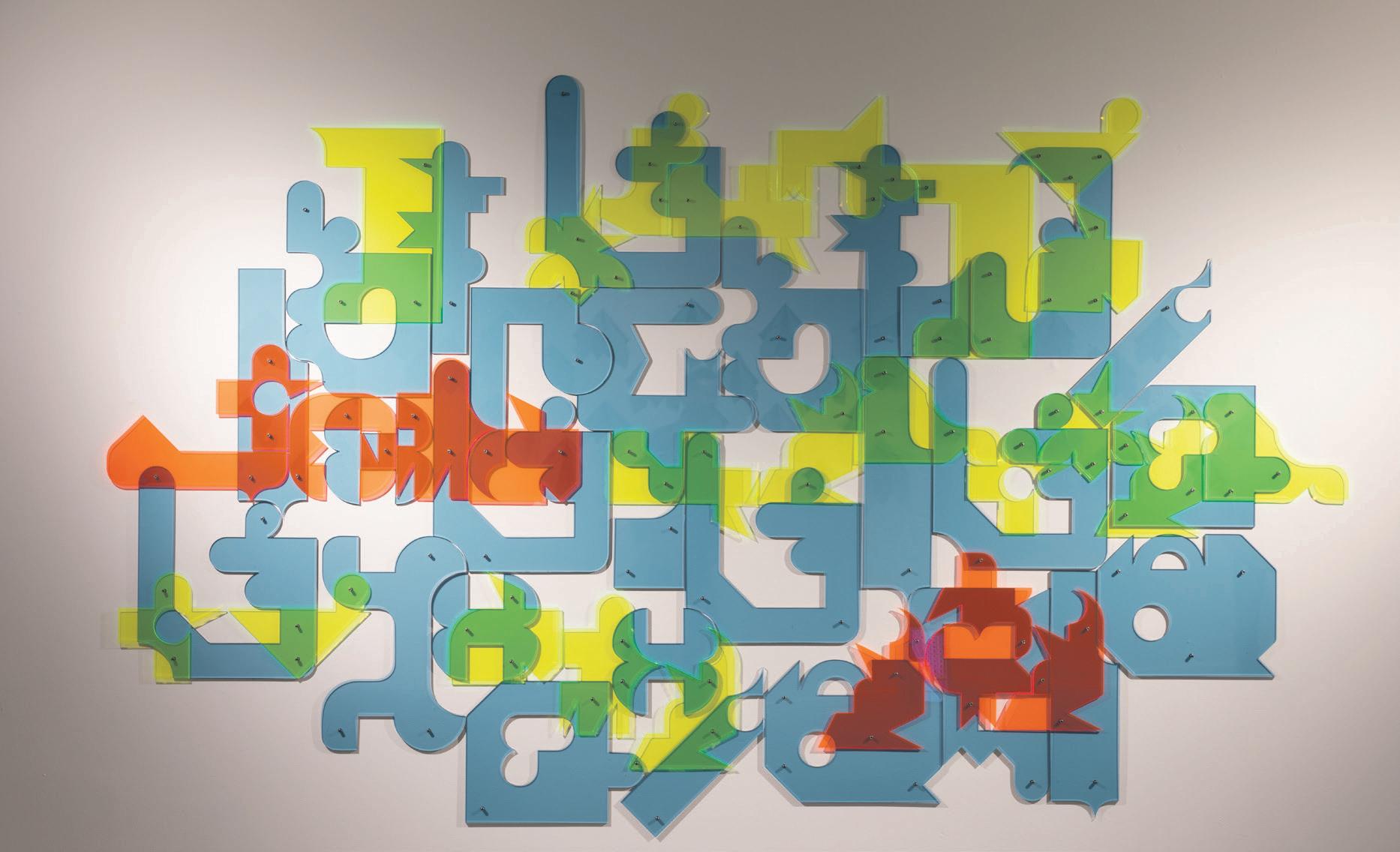

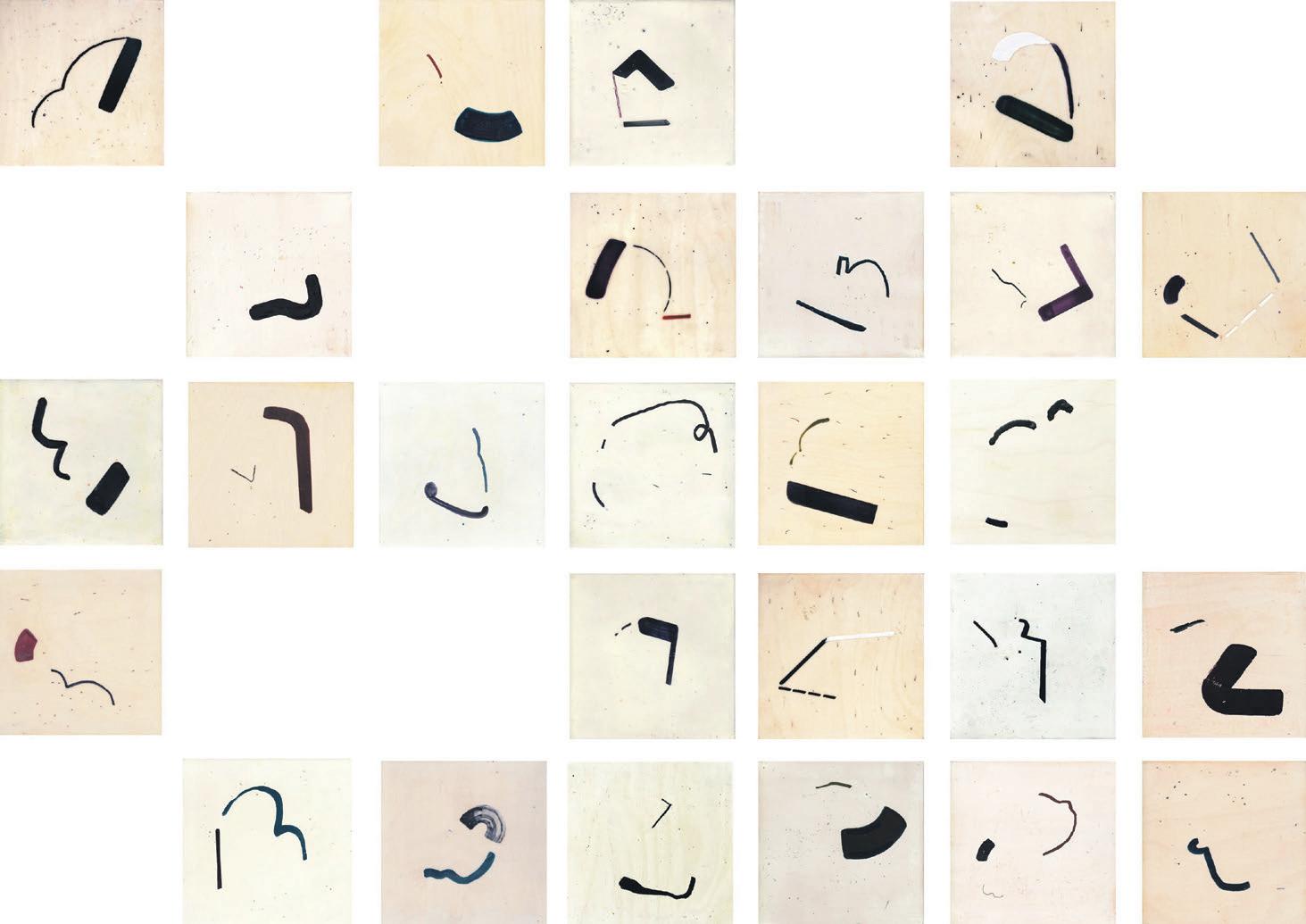

29. Kurnugia NOW! Celina Muldoon outlines her recent collaborative research project and current exhibition. 30. A Dormant Light. Aengus Woods reviews Lucy McKenna’s recent solo exhibition at Solstice Arts Centre in County Meath. 32. Staggering Verisimilitude. Jonathan Brennan reviews Ron Mueck’s ongoing solo exhibition at The MAC in Belfast.

Performance Art

34. Live Art Ireland. Deej Fabyc outlines the renovation of Milford House in Tipperary and the founding of Live Art Ireland. 36. Ritualistic Repair. Day Magee reflects on ‘Performance Ecologies’ at Interface in the Inagh Valley, Connemara.

Member Profile

37. Alive and Picking. Kathryn Crowley discusses her practice. Remotely Radical. Emma Campbell reflects on a recent exhibition by VAI members at Vault Studios in Belfast.

38. Augmented Auguries. Brenda Moore-McCann interviews artist and VAI member Claire Halpin.

Last Pages

39. Opportunities. Grants, awards, open calls and commissions.

Editor: Joanne Laws

Production/Design: Thomas Pool News/Opportunities: Thomas Pool Proofreading: Paul Dunne

CEO/Director: Noel Kelly Office Manager: Grazyna Rzanek

Advocacy & Advice: Elke Westen

Membership & Projects: Siobhán Mooney Services Design & Delivery: Alf Desire News Provision: Thomas Pool Publications: Joanne Laws Accounts: Grazyna Rzanek

Board of Directors:

Michael Corrigan (Chair), Michael Fitzpatrick, Richard Forrest, Paul Moore, Mary-Ruth Walsh, Cliodhna Ní Anluain (Secretary), Ben Readman, Gaby Smyth, Gina O’Kelly, Maeve Jennings, Deirdre O’Mahony.

The Visual Artists' News Sheet: Visual Artists Ireland: Republic of Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

The Masonry 151, 156 Thomas Street Usher’s Island, Dublin 8 T: +353 (0)1 672 9488

E: info@visualartists.ie W: visualartists.ie

Northern Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland 109 Royal Avenue Belfast BT1 1FF T: +44 (0)28 958 70361 E: info@visualartists-ni.org W: visualartists-ni.org

International MembershipsProject PartnersPrincipal Funders Project Funders Corporate Sponsors

The Visual Artists' News Sheet November – December 2022 Page 17 Page 23 Page 24 Page 33

Leigheas-Liminalis: antidotes for melancholic gestures Cecilia Bullo Hopefully Paul Hallahan Fragments & Fictions Siún Nic Suibhne 26 NOV 2022 - 28 JAN 2023 www.thedock.ie

The Most Recent Forever

Brian Fay

Limerick City Gallery of Art: 1.12.2022 – 12.02.2023

Uillinn / West Cork Arts Centre: 18.02.2023 – 25.03.2023

18 November – 28 January

In & of Itself, Abstraction in the age of images Austin Hearne Requiem for Raymo Gallery Press, Cover Versions Mark Joyce & Orla Whelan Ciara Roche, nightcall to 18 Dec

15 Ely Place, Dublin D02 A213 +353 1 661 2558 info@rhagallery.ie www.rhagallery.ie

H I B E R N I A N

Helen G Blake, Second sleep, 2022, Oil on linen, 40 x 50cm, Image courtesy of the artist.

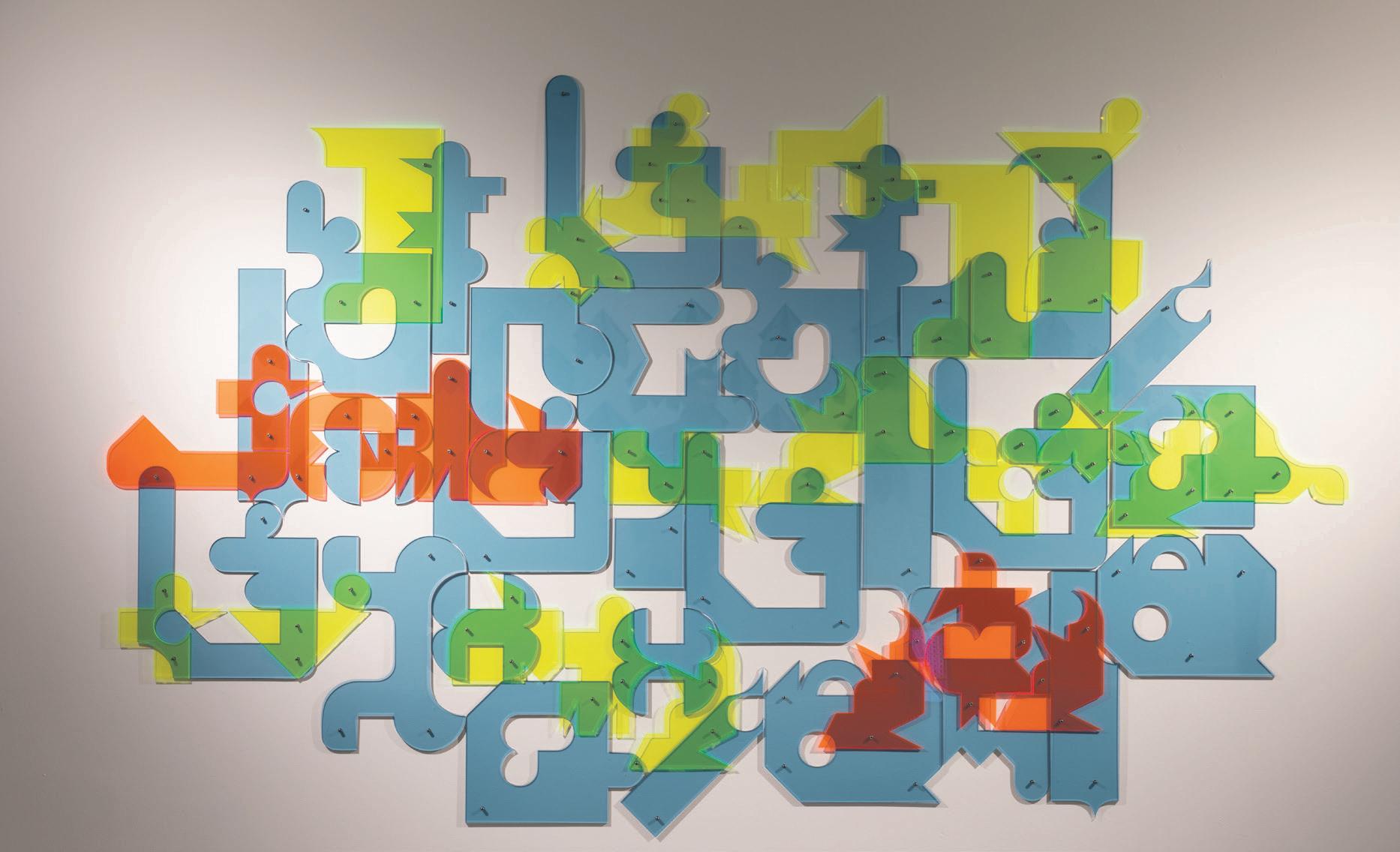

IMAGE: Kevin Mooney, Blighters, 2021 Photograph by Jed Niezgoda

IMAGE: Kevin Mooney, Blighters, 2021 Photograph by Jed Niezgoda

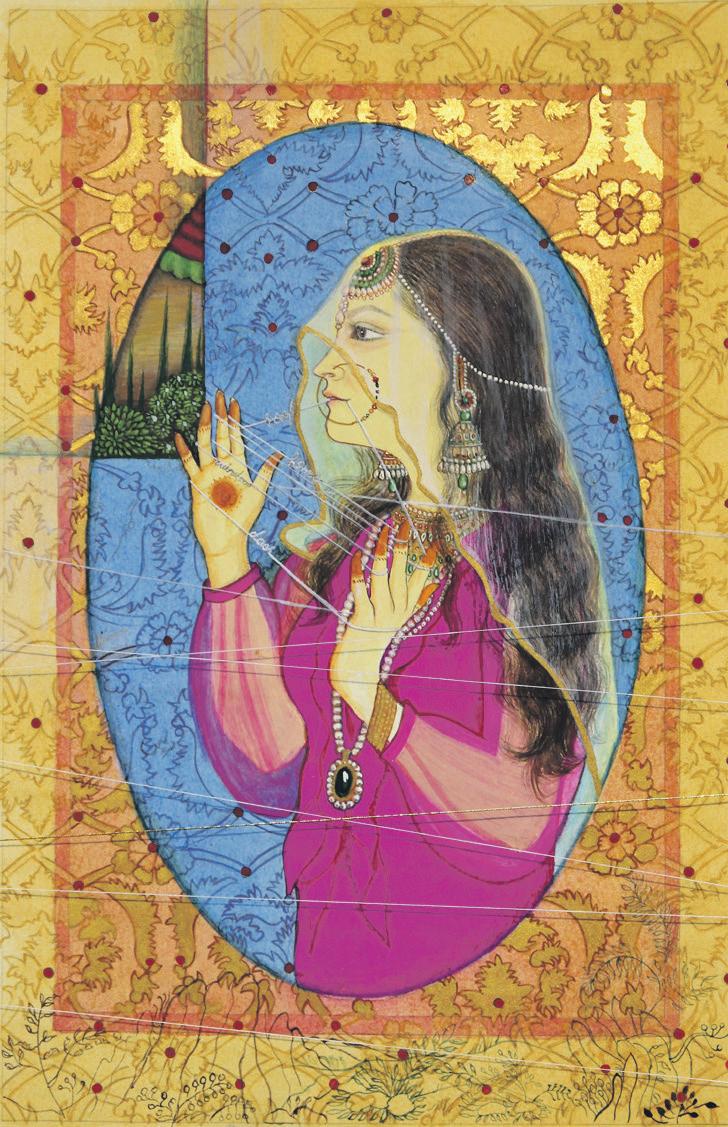

Kevin Mooney Revenants 1 December 2022 – 26 March 2023 Admission Free. Visit imma.ie +353 1 612 9900 imma.ie / info@imma.ie www.tulca.ie Anouk Kruithof Becca Albee Berte & Harmey Caroline Jane Harris Chloe Cooper Christopher Steenson Elise Rasmussen Emily Speed Esmeralda Conde Ruiz Judith Dean Kameelah Janan Rasheed Michael Hanna Nicoline van Harskamp Quentin Lacombe Tabitha Soren Tadhg Ó Cuirrín The Lifeboat curated by Clare Gormley 4 - 20 November 2022 Galway, Ireland The Exhibition 19.11.22 - 15.01.23 Butler Gallery | Evans’ Home | John’s Quay Kilkenny | R95 YX3F | butlergallery.ie Additional Funding Creative Ireland, The Broadcasting Authority of Ireland, Department of Arts, Kilkenny County Council and Ireland's Ancient East Image Cartoon Saloon, My Father’s Dragon 2022. Courtesy of Netflix

Exhibition Roundup

Dublin

Douglas Hyde Gallery

The Douglas Hyde presented the Irish pre miere of Arthur Jafa’s seminal work Love is the Message, The Message is Death. Jafa pres ents a poignant, visceral, and emotional reflection on African American life, identi ty, and history. Material largely taken from online sources, scenes of trauma, racism, and grief, such as routine police violence against Black people that is endemic to U.S. his tory, is presented alongside images of joy, defiance, and creativity. On display from 8 October to 6 November.

thedouglashyde.ie

Green on Red Green On Red Gallery presented Damien Flood’s exhibition ‘Dig’, in its Spencer Dock gallery, comprising new paintings, ceramics, and a new limited edition vinyl. Flood continues to make paintings and ceramic works that are seen separately and, in the case of Hanging Garden (2022), where one medium seems to grow out of or is enmeshed with the other. On display from 20 October to 27 November.

ArtisAnn Gallery

‘Time to Process’ was a joint exhibition by Gail Ritchie and Jennifer Trouton RUA. Though “time to process” is ostensibly a simple phrase, it can, like the works of both these artists, be interpreted in different and more complex ways. It has more than one meaning. Just as time need not be linear, nor process refer to a method or means of conducting an activity, so the works in this exhibition connect through commonality of approach. On display from 5 to 29 October.

Belfast Exposed

Mairéad McClean’s exhibition ‘HERE’ comments on the tension and anxiety felt by those living in Northern Ireland in the 1970s during “an explosive period of con flict and political unrest”; a time when the pressures of danger and threat – both invis ible and visible – permeated everyday life. McClean’s work unfolds the complexity of this experience through her memories. ‘HERE’ asks us to think about how politics and culture of a region are defined and how they define those who live here. On display from 6 October to 23 December.

MART Gallery

The MART Gallery presented ‘Mutators’, a solo exhibition by Kevin Mooney, in part nership with Sample Studios Cork and supported by The Arts Council of Ireland. Mooney is a Cork-based artist and member of Sample Studios. His work considers the voids which mark Irish visual culture, par ticularly related to Irish diasporic traditions and journeys. His paintings are inventions, tall stories which present as artefacts from a lost culture, and sometimes speculative imaginings of an alternative art history. On display from 1 to 21 October.

mart.ie

Pallas Projects/Studios

greenonredgallery.com

Pallas Projects/Studios presented the trans media installation ‘Interregnum’ by Rocío Romero Grau. Influenced by Bauman’s conceptualisation of a ‘Liquid Modernity’, Rocío interrogates our present as a liminal space, an interregnum between an unre liable past and an uncertain future. This liminal space has been mostly shown as an empty, desolated, non-place, but it could potentially be a vivid space of collision and chaos; the battlefield where the antagonis tic meet. On display from 13 to 29 October.

pallasprojects.org

Platform Arts

artisann.org

‘Hot glue’ was an exhibition of newly com missioned work by materialists Sophie Gough and Daire O’Shea, curated by Sara Muthi. The German word Material gerechtigkeit loosely translates to ‘material justice’. This principle holds that any mate rial should be used where it is most appro priate and that its nature should not be hidden. ‘Hot glue’ maintains that sculpture cannot be exhausted by perceptive experi ence nor reduced to any formal description of its constituent parts. On display from 5 to 21 October.

platformartsbelfast.com

QSS Artist Studios

belfastexposed.org

QSS hosted ‘Did That Really Happen?’, a two-person exhibition by QSS-based artist Dan Ferguson and Belfast-based artist Pat rick Colhoun. Both artists rely on memory to direct their work. With age and deeper personal introspection, it has become a pri mary feature in Colhoun’s sculptures and Ferguson’s paintings. The element which unifies the two artists’ practice is the accep tance that the broader concept of ‘memo ry’ that underpins their work is malleable, unreliable, inconsistent, and possibly even false. On display from 6 to 27 October.

queenstreetstudios.net

RDS

The RDS Visual Art Awards were held in the RDS Concert Hall, Ballsbridge, from 21 to 29 October. 13 graduate artists were exhibited after making it through a very selective two-round process out of 109 art ists who were longlisted. Each of the 13 artists has a chance to receive: The RDS Taylor Art Award (€10,000); R.C. Lew is-Crosby Award (€5,000); RDS Members’ Arts Fund Award (€5,000); RHA Gradu ate Studio Award (€7,500 value); and final ly the RDS Mason Hayes & Curran LLP Culturel Irlandais Residency Award, in Paris (€6,000 value).

rds.ie

SO Fine Art Editions

‘Thin places of escape and return’ featured colour etchings, monoprint and collage by Niamh Flanagan, and was the first major solo exhibition of her work since ‘An Else where Place’ in 2012. The motif of the house or dwelling space is central to Flana gan’s work, calling into question the notion of the house as a formative psychological structure, one that inhabits our dreams and our inner spaces, while also providing a physical barrier between the inside world and the outside. On display from 8 to 29 October.

sofinearteditions.com

RUA

The 141st RUA Annual Exhibition at the Royal Ulster Academy is one of the most eagerly anticipated exhibitions in the Northern Irish cultural calendar, providing a unique platform for acclaimed artists and emerging talent to showcase their artwork in the galleries at the Ulster Museum. It is also a chance for the public to engage with a fully democratic, free admission exhibition. The exhibition presents painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, video and more. On display from 14 October 2022 to 3 January 2023.

Vault Artist Studios

‘Sense of Place’ was an exhibition of new work by Belfast-based artist, Jonathan Brennan. Featuring large works on canvas, drawings and experimental photos, from several evolving series, Brennan attempts to conjure feelings of intrigue, awe and mel ancholy with these atypical depictions of spaces, both real and imagined. ‘Sense of Place’ included new work created in 2022. This is Brennan’s first solo exhibition since 2019 and celebrates atypical landscapes, places teetering on the edge, real views and imagined scenarios of Belfast and its sur roundings. On display 14 to 30 October.

vaultartiststudios.com

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | November – December 20226

Arthur Jafa, Love is the Message, The Message is Death, 2016, video still; ©Arthur Jafa, courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

Jonathan Brennan, Hic Jacet MPW et al., 2022, acrylic on canvas; image © and courtesy the artist.

royalulsteracademy.org

Belfast

Exhibition

Regional & International

Ards Arts Centre

‘Beyond Edges’ was a group exhibition of paintings, glass artefacts, and sculptures crafted in wood and metal by Andrea Spen cer, Nicola Nemec, and Sharon Adams. This was an elegant and thought-provok ing exhibition in which three woman art ists investigate, interrogate and interpret their immediate locale and shared hinter land of open hills and dramatic coastlines in North Antrim. All three artists respond to the land and the impact of man’s inter vention on it. On display from 8 Septem ber to 22 October.

andculture.org.uk

Ballinglen Arts Foundation Gallery

‘Inherit’ was an exhibition by Place|Lab collective. The seeds of ‘Inherit’ were sown in Iceland in 2019 when the collective came together for a residency. The project then developed over time via Zoom , culminat ing in this diverse collection of thoughts and work. On display at Ballinglen Arts Foundation Gallery from 27 August to 27 September, the show will tour to Contem porary Art Space Chester (CASC) UK in November 2022, and to Springville Muse um, Utah and MCLA Gallery 51, Massa chusetts, USA, in 2023.

ballinglenartsfoundation.org

Coastal Wexford

‘Catch 22 /Art Tra’ took place during August and September on 22 beach loca tions around South Wexford. It featured the work of 15 Artists working in drawing, textile, painting, sculpture, photography and recycled materials. The coastal ven ues varied, depending on the tidal restric tions and weather. The project was funded through Wexford County Councils Arts Office – Small Arts Festival and Experi mental Events Scheme 2022.

sunmoonandstarspress.wixsite.com/catch-22-art-tra

Custom House Studios and Gallery

‘Imagine Life Without Art’ by Bernadette Kiely was on display from 29 September to 23 October. Kiely grew up on the banks of the River Suir and has lived and worked on the quayside of the River Nore since the 1980s. This exhibition was an exploratory journey around her primary themes of the effects of weather and changing climate on land, landscape and human lives over time. It featured paintings, drawings and moving image created over a 25-year period.

customhousestudios.ie

Garter Lane Arts Centre

‘A Way of Showing’ by John Conway, fea turing sculpture, installation, text-based work and moving image, is on display from 8 October to 12 November. Con way is a visual artist based in Rua Red in South Dublin. His work is characterised by innovative multi-disciplinary projects and sophisticated solo and participato ry artworks which are often produced in response to sensitive, challenging, or nov el contexts. He frequently commissions, curates, and collaborates with other spe cialists, and orchestrates complex projects. garterlane.ie

Solas Art Gallery

‘On Edge’ was a joint exhibition by Eileen Ferguson and Neal Greig, on display from 26 August to 17 September. This was their first exhibition together since 2010. They have their studios in Monaghan and on Coney Island, Sligo, where Eileen has her ancestral home. While Eileen and Neal’s paintings are thematically different, they are connected by a sense of colour, texture and an awareness of painterly tradition. The language of mark-making is explored and a sense of time and space conveyed.

solasart.ie

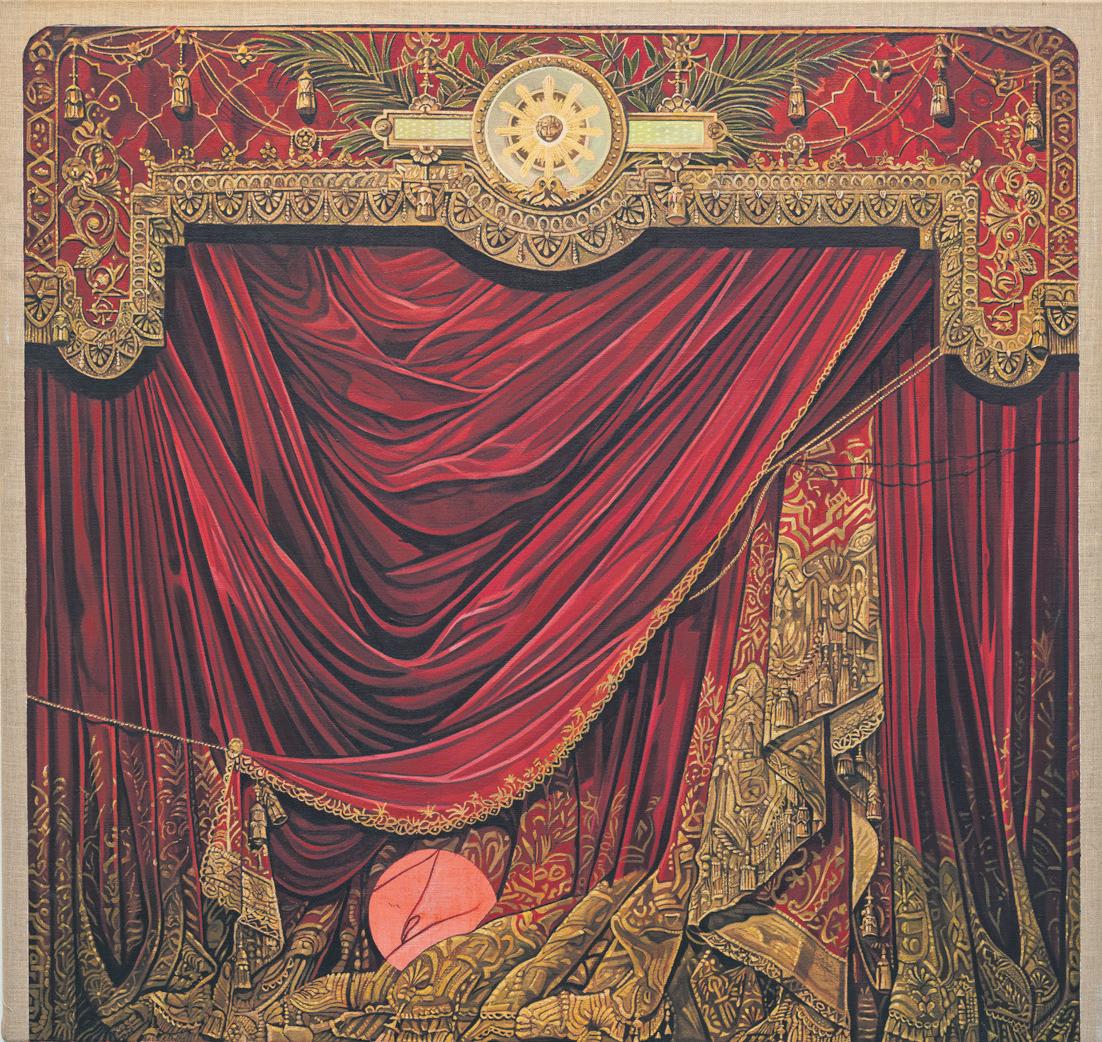

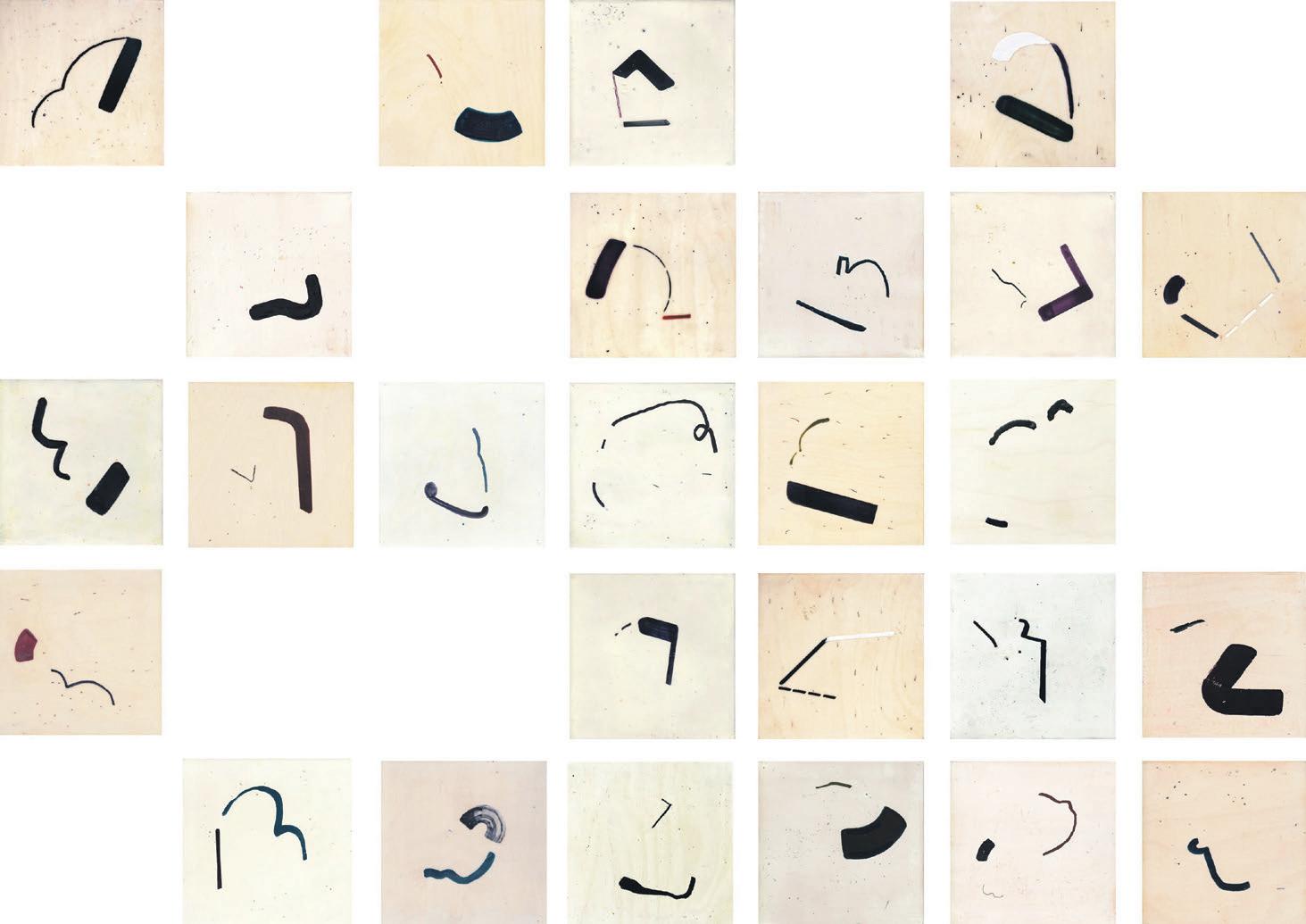

Highlanes Gallery

Brian Fay’s ‘The Most Recent Forever’, is a survey exhibition of the artist’s drawing practice, which was presented at Highlanes Gallery as a national tour in partnership with Limerick City Gallery of Art and Uil linn: West Cork Arts Centre. Fay’s practice uses different representational strategies of drawing to record, depict and present mod els of time and temporality using pre-exist ing artefacts, objects and artworks to stand in for our own experience of time. The exhi bition continues until 12 November.

highlanes.ie

KAVA

‘Awakening’ by Nicole O’Donnell was on display from 20 to 26 October. O’Donnell’s practice is influenced by the wilderness of the Irish landscape. Daily observations and the natural world are used to create imag inative landscape paintings that deal with themes of experience of place, memory. They are inspired by the endless complexity found in nature. This body of work focus es on what is both equally beautiful and degraded and is concerned with balancing both the abstract and realistic elements within.

kava.ie

Pigyard Gallery

The Pigyard Gallery in Wexford town presents a solo exhibition by artist Gillian Deeny from 15 October to 6 November. The exhibition, titled ‘Quest’, is delivered in partnership with Wexford County Council and Wex-Art, to coincide with Wexford Festival Opera 2022. As an artist, Deeny searches for meaning and beauty in the everyday, which includes detailed examina tions of the Irish landscape and the natural world, where she finds quiet moments that resonate across different strands of poetry, philosophy, and ecology.

facebook.com/PigyardGallery

Sonic Acts Biennial

Recently shown at Sonic Acts in Amster dam, ‘Gauge’ (2015), is an experimental film installation showing tidal movements of sea ice off Baffin Island in the Canadian Arc tic. Using time-lapse from cameras on the floating sea ice, painted sea ice cliffs appear to rise and fall. The work is a collaboration of Danny Osborne, Patrick Thompson, Alexa Hatanaka, Sarah McNair-Landry, Eric McNair-Landry, Erik Boomer and Raven Chacon. On display 30 September to 23 October.

sonicacts.com

St. Luke’s Crypt

The Project Twins’s exhibition ‘100 Sec onds to Midnight’ takes its name from The Doomsday Clock, a metaphorical sym bol that represents how close humanity is to self-destruction. In January 2020 the clock was set at 100 seconds to midnight. Employing minimal forms and graphic shapes, their work is rooted in the visual language of signs, symbols and pictograms which can be found in various systems of propaganda and control to communications and way-finding. On display from 1 to 24 September.

sample-studios.com

The Earth Vision

‘Augmented Body, Altered Mind’ wove a brain-computer interface with an audio visual environment on display at London’s The Earth Vision from 8 to 16 October. Created by Alan James Burns, the show celebrated different cognitive abilities used for creative problem-solving. ‘Augmented Body, Altered Mind’ explored the potential to collectively reshape the world towards a more diverse and sustainable future. It was initially conceived during Burns’s residency at the Science Gallery Dublin in 2020 and was presented at Carlow Arts Festival 2022. theearthvision.com

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | November – December 2022 7

Roundup

‘Catch 22 /Art Tra’, Baginbun Beach, Wexford, 19 September; photograph by Lisa Kinneen, courtesy Andi MacGarry. The Project Twins, ‘100 Seconds to Midnight’, 2022, installation view; image courtesy of the artists.

The tenth edition of the King Ping Pong tournament will take place on Monday 7 November at The Complex, Dublin. All are welcome, but partici pation in the tournament is only open to visual arts workers.

King Ping Pong started in Monster Truck in 2012 and was such a success, that Davey Moor and Monster Truck director Peter Prendergast decid ed to run it as a fun annual event for the sector. Over the years, many arts organisations in Dublin and beyond have fielded players. KPP does not receive any kind of funding or corpo rate sponsorship and depends on the generosity of the host organisations (which changes every two years).

This year, Paul McGrane, Visual Art Co-ordinator at The Complex, joined as a co-organiser.

Basic Income for the Arts

In early September, 2,000 Artists and Cre ative Arts Workers were granted Basic Income for the Arts. The historic, threeyear pilot scheme will give €325 per week to those selected for the experiment. A fur ther 1,000 people were chosen to be part of the control group who will be offered remu neration for their participation.

Over 9,000 applications were made under the scheme with over 8,200 assessed as eligible and included in a randomised anonymous selection process. Those select ed include 707 visual artists, 584 musicians, 204 artists working in film, 184 writers, 173 actors and artists working in theatre, 32 dancers and choreographers, 13 circus artists and 10 architects. 3%, or 54 of those selected, work through the Irish language.

Eligibility for the scheme was based on the definition of the arts as contained in the Arts Act 2003; “arts means any cre ative or interpretative expression (whether traditional or contemporary) in whatever form, and includes, in particular, visual arts, theatre, literature, music, dance, opera, film, circus and architecture, and includes any medium when used for those purposes.”

There were three categories under which applicants could apply as follows:

1. Practising artists;

2. Creative Arts Workers (defined as someone who has a creative practice or whose creative work makes a key contribution to the interpretation or exhibition of the arts);

3. Recently Trained i.e. graduated with a relevant qualification in the past 5 years.

84% of those selected identified as prac tising artists, 9% identified as Creative Arts Workers and 7% as Recently Trained Applicants.

In October, a further 27 artists were selected, through another lottery of non-ac cepted applicants, to replace declined offers.

VAI welcomed this significant event and recognised the widespread disappointment amongst those artists who did not receive positive news. With 2,000 artists, 707 visu al artists are to benefit directly from the scheme, with an unknown number of visual artists not in receipt of the payment being asked to participate as paid members of the

THE LATEST FROM THE ARTS SECTOR

Since 2016, a ‘krazy table’ has been commissioned to augment the visual experience. The first of these was by Prendergast & Moor, the curatori al duo that founded KPP. From 2017 onward, the hosts began inviting artists to make tables, which have amused and frustrated participants and spectators alike. Table makers to date: Ella Bertilsson (2022), Lil iane Puthod (2022), Conor O’Sullivan (2021), Dáire McEvoy (2019), Tanad Aaron (2018), David Lunney (2017), Prendergast & Moor (2016).

An exhibition of the seven krazy tables will be presented in the the atre space of The Complex on 6 and 7 November, ahead of this year’s tournament, which takes place on 7 November.

control group. The figure of 707 artists rep resents approximately 20% of the visual art ist population, and we look forward to the results as they are published, either during or after the pilot scheme, and the time when a permanent scheme is put in place to the benefit of all visual artists. We continue to be in dialogue with the Department.

The Arts Council Budget 2023

The Arts Council welcomed the September announcement of €130M funding as part of Budget 2023. This funding enables the Arts Council to continue and deepen its investment in the arts. The Arts Council recognised that Covid-19 continues to have an impact on audience engagement and that the sector faces further challenges with issues relating to cost of living. The funding announcement ensures that the Arts Coun cil can provide meaningful support to the sector in the coming year.

Arts Council Chair, Prof Kevin Raf ter said, “The decision to keep funding at €130M for a third consecutive year is wel come, and this money will allow the Coun cil to continue to help the arts sector recov er from the Covid-19 pandemic and to deal with significant cost of living increases. The Council will continue to make the case – as it has done over the last two years – for an annual budget of €150M to further develop the arts sector across the country.”

Arts Council Director, Maureen Ken nelly said, “The Arts Council is delighted to welcome today’s budget announcement. The work of the Arts Council invests in thousands of artists and hundreds of arts organisations across the country while providing long-term sector development. Today’s funding announcement ensures it can continue this vital work.”

The O’Malley Award for Visual Art 2022

The New Jersey-based Irish American Cul tural Institute announced that the 2022 O’Malley Award of €5,000 went to Vukašin Nedeljković for his ongoing project Asylum Archive

The O’Malley Visual Arts Award was inaugurated in 1989 and is given in mem ory of Ernie O’Malley and Helen Hooker O’Malley. Previous winners include Tony O’Malley, James Coleman, Dorothy Cross,

and Alice Maher. The Award is given for outstanding work created during the period since the previous award.

The judging panel for the O’Malley Visual Arts Award 2022 was made up of Sean Lynch (artist, curator and writer), Johanne Mullan (curator, Irish Museum of Modern Art), and Helena Tobin (curator and director, South Tipperary Arts Cen tre). The award was given to Vukašin Ned eljković for his ongoing work documenting the experience of people living in detention centres and “the architecture of confine ment, ghosts, traces, remnants – what is left after people have been transferred or deported.”

EVA International Biennial EVA International announced ‘Never Look Back’, a new initiative that revisits EVA’s 45+ year history of producing contempo rary art exhibitions and events in Limerick.

Originally founded by artists in 1977, EVA remains one of the longest running visual arts organisations in Ireland, working with some of the world’s most acclaimed artists and curators.

‘Never Look Back’ explores EVA’s histo ry in Limerick through the roster of tempo rary sites, spaces, and venues – from offices, shops, museums, ex-industrial units, and public spaces – used for the presentation of contemporary art in successive editions. Borrowing its title from Jakob Gautel and Jason Karaïndros’s street inscription – pre sented during EVA’s 20th edition, EV+A 96, curated by Guy Tortosa – ‘Never Look Back’ seeks to illuminate a rich history of contemporary art that intertwines with the urban evolutions of the city. Developed by EVA in partnership with a working group of architects and artists (Peter Carroll, Caelan Bristow and Fiona Woods) the initiative hopes to provide new access and understanding of Limerick’s unique story of contemporary art, while thinking crit ically about the ways that art takes place within the public realm, often through pro cesses of regeneration and redevelopment.

The inaugural projects of ‘Never Look Back’ in 2022 include a website and digital resource designed by An Endless Supply which will go live in November, and the first of a series of curatorial commissions

that respond to EVA’s history in Limerick – by RGKSKSRG (Kate Strain & Rachael Gilbourne) and Michele Horrigan (Askea ton Contemporary Art).

EVA Director Matt Packer says, “In its 45+ years of existence, EVA offers a unique and invaluable story of contemporary art in a city that has, itself, undergone con siderable change during this same period.

The ‘Never Look Back’ initiative not only provides an opportunity to tell this story through the sites and spaces that art has temporarily inhabited, it also provides a platform of critical and creative responses to ideas of art’s relationship to architecture, to people, and to place.”

‘Never Look Back’ is supported through the Arts Council’s Engaging with Archi tecture Scheme and Limerick City and County Council.

RDS Visual Art Awards

The winners of the RDS Visual Art Awards have been announced, at the launch of the annual exhibition that celebrates emerg ing Irish artists. The 2022 exhibition was curated by internationally acclaimed artist Aideen Barry and ran at the RDS Concert Hall from 21 to 29 October. This year’s awards were announced by Chair of the judging panel, Mary McCarthy (Director of the Crawford Gallery, Cork) and pre sented by the RDS President, Professor Owen Lewis.

Commenting on the talent this year, Mary McCarthy said: “We were enthralled by the work of the 13 shortlisted artists... We are also very impressed by the ability of this year’s RDS Taylor Art Award winner, Venus Patel to turn a transphobic attack into an incredibly beautiful artwork.”

• Venus Patel – RDS Taylor Art Award (€10,000)

• Sadhbh Mowlds – R.C. Lewis-Crosby Award (€5,000)

• Orla Comerford – RDS Members’ Art Fund Award (€5,000)

• Lucy Peters – RHA Graduate Studio Award (value €7,500)

• Myfanwy Frost-Jones – RDS Mason Hayes & Curran LLP Centre Cul turel Irlandais Residency Award (value €6,000)

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | November – December 20228 News

King Ping Pong

Paul McKinley and Vanessa Donoso López, King Ping Pong 2015 tournament at TBG+S; image courtesy the artists and Davey Moor.

Sea Interludes

CORNELIUS BROWNE CONSIDERS THE SEA AS AN OMNIPRESENT FORCE IN THE WORK OF DONEGAL PAINTERS.

Ecologies Reflections on a Radical Plot

CLODAGH EMOE CHRONICLES THE EVOLULTION OF A LONGRUNNING ECOLOGICAL PROJECT.

REFLECTIONS ON A Radical Plot is an eco logical archive of wild plants growing in the artwork Crocosmia × (2018), located on the margin of the front lawn of IMMA – a plot that was planted entirely of Crocos mia × crocosmiiflora in 2018. Crocosmia × is an outcome of my ongoing collaboration with individuals seeking asylum that began in 2015 in the garden of Spirasi (Spiritan Asylum Services Initiative) – the national centre for the rehabilitation of survivors of torture in Ireland. The garden set the foun dations for the project, giving us a shared sense of purpose and a physical space to connect with each other and the natural world, offering meaning, and inspiring our collaboration.

My residency in IMMA as part of ‘A Radical Plot’ (July 2021 – March 2022) allowed me to re-engage with Crocosmia ×, giving me time to observe and reflect on what we did not foresee – the quiet evolu tion of this artwork. Its status ensures that it has not been tampered with, allowing the natural process of self-seeding. Reflections on A Radical Plot witnesses the transforma tion of this artwork into a valuable ecosys tem of significant and distinct plant species, offering a further reminder that diversity is the natural state of being.

THROUGHOUT THIS YEAR, I’ve been paint ing extremely small pictures of an extraor dinarily vast subject. The pockets of my paint-spattered raincoat accommodate a dozen of these roughly cut boards. In the past, in a life conditioned by frugality, it pained me, after painting sessions, to scrape paint away. The boards give me a com pact stage upon which to perform encores. Instinctively, I also now reach for one when something catches the corner of my eye, and I’m perhaps painting in the opposite direction. I find myself dashing along the shore, clutching palette and brush, knowing I can use my hand as easel. The sea is omni present where I live and work, so although I have painted more than a hundred tiny boards so far this year, without exception they dance to a maritime tune.

An ocean of music has been shaping my paintings since I was a schoolboy. I first heard Benjamin Britten’s opera, Peter Grimes (1945), on wobbly cassette almost 40 years ago. To move listeners from one physical location to another, Britten wrote Sea Interludes (1945); short pieces of music that, despite their brevity, capture with alarming fullness the majestic force mould ing the lives of the townspeople in his iso lated little fishing village. I clearly recall my young self, rewinding or fast-forwarding the tape relentlessly to locate the high grace notes of flutes and violins that mimicked so closely the sea birds I could hear from our home. Light on water was already attract ing my attention as a juvenile painter, yet I felt no artist could better the shimmering arpeggios created by Britten’s harp, violas, and clarinets. In all likelihood, that cassette wore out on the Storm (1945) interlude – I remember the house empty one calm spring morning, giving me the opportunity to raise the volume. Within moments, our rickety dwelling was battered by thunderous waves. My own ‘sea interludes’ take about the same time to paint as it takes to listen to one of Britten’s pieces: just under five min utes. I’m already in the flow, geared up to catch the wave. The sight we see from the

shore is the same as it has ever been; the sea is a place where the boundaries between past and present are slender. I paint from the fields my great-great-grandparents and their neighbours tilled for crops or walled for cattle. My children, however, look towards the horizon and ponder microplas tics, extinction, and rising sea levels.

From the anonymous author of Navi gatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis in the ninth century, recounting St. Brendan’s westward journey in his medieval skin boat, to Doro thy Cross’s Ghost Ship (1999) in Scotsman’s Bay in Dún Laoghaire at the end of the twentieth century, the sea has been a perva sive presence in Irish art and literature. At 1,134 km, the Donegal mainland coastline is the longest in the country. Unsurpris ingly, generations of Donegal artists have wrestled with the Atlantic.

Recently, I spent the 22nd anniversary of Derek Hill’s death teaching a plein air workshop in the gardens of the English painter’s former home, Glebe House in Donegal. In the eighties, having seen some of my paintings made using household gloss, Hill gifted me a set of oil paints –my first ever. In the fifties, roughly a decade before I was born, Hill gifted paints to one of Donegal’s most astonishing paint ers. James Dixon was at the opposite end of his life to me when he received these paints. This was a man already in his sev enties, who observed Hill painting a large landscape outdoors one Sunday morning after mass on Tory Island, and remarked, “I think I could do better”. Dixon, at that moment, had hardly ever stepped foot off the small island where he was born, devot ing his life to fishing. Describing Dixon’s work, Hill reached for the language of the sea, observing that they had been “painted quickly and instinctively – unrestful and turbulent”. Furthermore, when recollecting the bundles of paintings sent by Dixon, Hill stated: “I imagine them thrown into the sea and washed ashore after a storm”. Cornelius Browne is a Donegal-based artist.

While gardening, we found a gnarled corm of a crocosmia × crocosmiiflora –more commonly known as Montbretia, and found along hedgerows in Ireland. Although many assume this to be a native plant, it is a hybrid from South Africa. This vibrant orange flower offered a symbol of hope for members of the group who had themselves been uprooted; forced to leave their homeland and create a new life in a foreign land. Crocosmia × became our met aphor that questioned received notions of what is ‘native’ and what is ‘foreign’. Their flourishing in Ireland champions our con ception of community, centring on relations formed across categories of nation, race and culture. Support from Janice Hough (Art ists’ Residency Programme Co-ordinator at IMMA) and Mary Condon (Head Gar dener at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham / IMMA) ensured our access to the nursery at RHK, to grow and nurture specimens for the artworks in IMMA and TU Dublin (commissioned as part of the Grangegor man public art programme, ‘…the lives we live’, curated by Jenny Haughton). This had an immense impact on the project and this beautiful outdoor workspace became our place.

The companion prints in the archive include nettle, forget me knot, primrose, herb Robert, plantain, nipplewort, prickly sow thistle, poppy, wild violet, and western willow herb. This ecological form of print making is not reliant on technical expertise but on the composition of the plant itself. This unpredictable process draws the nat ural essence from the plant and ‘saddens’ it onto paper. The resulting image is the trace of the plant. In archiving a continuously evolving artwork, Reflections on A Radical Plot acknowledges the potency and com plexity of both nature and art as entangled and un-ending processes.

Clodagh Emoe is an artist and parttime lecturer at IADT. Recent projects include Classroom in the Sun (2022), an inter-generational, collaborative, Arts Council-funded project that addresses urgent issues of our bio diversity crisis by supporting a com munity to connect with nature and realise their ambition to design and create an outdoor space for learning, exploration and connection. Clodagh is currently developing Seed STUDIO, an ecological studio space piloted by IMMA, that addresses an overwhelm ing need to explore, deepen and cele brate our connection with the natural world.

clodaghemoe.com

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | November – December 2022 9Columns

Plein Air

Cornelius Browne, Sea Interlude: Black Boat, 2022, oil on board; photograph by Paula Corcoran, courtesy of the artist.

Clodagh Emoe, Primrose (Primula vulgaris) 2022, ecological print on cotton paper; image courtesy of the artist.

Moving Image

Chronic Collective

TARA CARROLL AND ÁINE O’HARA DISCUSS THEIR MULTIDISCIPLINARY ART COLLECTIVE AND THEIR ADVOCACY FOR IMPROVED ACCESSIBILITY IN THE ARTS.

WE ARE TWO best friends, Tara Carroll and Áine O’Hara, who connected over our love of performance art more than ten years ago. Now our bond strengthens over our shared chronic illnesses and the immense care we provide each other, in order to survive. We’ve subconsciously created a care web. Explained by queer disabled femme writer and activist, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Sa marasinha, a care web is when a group of disabled people work together to provide care and access to resources to support each other.

The pandemic’s disruption of societal stasis and the barriers we and our peers collectively face in the arts more broadly, made it even more apparent that our col lective (previously called 4D Space) needed to evolve. We wanted to expand our care web in the best way we knew how, through art, knowledge sharing, creating spaces and nurturing relationships.

We are now known as Chronic Collec tive, a multidisciplinary curatorial art col lective with a strong focus on accessibility in the arts. As two queer and disabled/ chronically ill artists, we strive to create opportunities to platform disabled and/or chronically ill artists’ work in a supportive and care-focused environment, catering to individual needs with a view to alleviating some of the barriers faced when creating and exhibiting work.

This summer we curated a programme of events and workshops about the body, illness, and accessibility at Pallas Projects. All events were active sites of learning and practice about access. It was supported by the Capacity Building Award 2022 from the Arts Council. All events and workshops were designed to have a slower pace, flexible timing, and plenty of breaks. We provided a quiet low light rest area, comfortable seat ing, masks, ventilation and free snacks and water. Many of our events were hybrid with Irish Sign Language (ISL) and live cap tioning.

We designed a series of performance art workshops and events which supported the work of 15 disabled and/or chronically ill artists and nurtured connections within their community. We supported these art ists by asking them what their needs are – a question many told us they had never been asked before – which we accommodated to the best of our abilities. We did this because we saw a glaring gap in accessibility in the visual arts and the arts in Ireland generally. We wanted to give disabled, chronically ill and neurodiverse artists and audiences an accessible space that was made by us for us.

What does accessibility mean to us?

In Ireland conversations around accessi bility in the arts, and accessibility in gen eral, have been very limited. When asking about how accessible an event or venue is, we have often been simply told a space is

‘not accessible’. We assume when this is the answer that they mean a space is not wheelchair accessible. We cannot cater to every individual’s access needs at once, but access for us is a lot more than a ramp into a building, though we want those too!

Information is power for us. Is your event seated? What kind of seats? Will there be captioning or ISL? Is your event relaxed, can I leave and come back, can I make noise, can I be on my phone? Do you require masks? Will the event be available to watch online? If there are steps into the building, how many? On a good day I could climb a flight of stairs, on a bad day I might be able to do one step, but I can’t make an informed decision if you don’t give me the information.

Make your information available and easy to find on your website. We know that no space or event is fully accessible, so there is no need to shamefully shy away from highlighting what is and isn’t available. It is good practice to include access costs in your budget to develop your programmes with access in mind from the beginning.

In 2011, writer and disability justice activist Mia Mingus, in her blog Leaving Evidence, described “access intimacy” as an “elusive, hard to describe feeling when someone else gets your access needs” and a sense of “comfort that your disabled self feels” (leavingevidence.wordpress.com). This is what we are striving for in our work and in our personal lives. Access intimacy can be given or received by anyone, disabled or not.

Access intimacy builds connection; it often doesn’t mean that an event or exhi bition is 100% accessible but that everyone involved is trying as hard as possible to ensure accessibility for as many people as possible. We encourage you to work with us as a community when you are developing your access plans and creating events, exhi bitions and workshops. There are as many different access needs as there are artists or audience members. We will continue to create spaces for our community to take part in the arts.

Tara Carroll is a multidisciplinary artist, curator and facilitator and Áine O’Hara is a multidisciplinary artist, designer and theatre maker. @chronicartcollective chronicartcollective@gmail.com

Oh Infamy

IARLAITH NI FHEORAIS DISCUSSES A NEW FILM MADE IN COLLABORATION WITH EMMA WOLF-HAUGH.

OH INFAMY WE eat electric light (2022) is a new film by Emma Wolf-Haugh and I, which will be launched at Oonagh Young Gallery on 3 November. The film was co-commissioned by ANU, Landmark Productions, and the Museum of Litera ture (MoLI) in partnership with Arts and Disability Ireland (ADI). The commission forms part of Ulysses 2.2 – a year-long pro gramme marking the centenary of the pub lication of James Joyce’s Ulysses, through 18 multidisciplinary projects, including film, poetry, music, theatre, writing, archi tecture, and visual art, presented in various venues across Ireland throughout 2022.

Our fellow practitioners are Adrian Crowley, Anne Enright, Branar, David Bolger of CoisCéim, Emilie Pine, Emma Martin of United Fall, Evangelia Riga ki, Fehdah, Fintan O’Toole, God Knows, Harry Clifton, Louise Lowe, Marina Carr, Matthew Nolan, Molly Twomey, Nidhi Zak/Aria Eipe, Owen Boss, Paula Mee han, Sinéad Burke, The Domestic Godless, and Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Grafton Architects. Each practitioner was matched with one of the 18 episodes of Ulysses to respond to in their own way. Emma and I were given Episode 15, ‘Circe’, which follows the protagonist Bloom on a night-time hallucinatory adventure through Dublin’s Monto.

Emma has made critical and playful work inspecting the legacy of modernism in Ireland, most recently the legacy of Eileen Gray in the film Domestic Optimism (2021), shown at Project Arts Centre last year. Oh – Infamy – we eat eclectic light emerged from a series of conversations between Emma and I about how we wanted to treat this material that has come to be held in such high regard as an artefact of national signif icance and symbol of high Irish literature. Adopting a disobedient position, aimed at undoing the sanctity that’s been construct ed around the text, we proceeded with a close reading – a first for both of us. This revealed an unexpected tale of nocturnal lives, animism, justice, sex work, kink, and gender-swapping, raising new questions of this work’s relevance to contemporary Dub lin. This included a section, which came to be the central focus of the film, in which Bloom swaps gender with a dominatrix in a BDSM session. Alongside this unforeseen depiction of sexuality for the time, ‘Circe’ holds an image of the Monto and of Dub lin that many today would not recognise.

Reflecting the history of the Monto drew our attention to the ecstasy, chaos, mysticism, revelations, and the labour of the night. We considered how the liberato ry potential of some of these activities has been extinguished in Dublin over the last 15 years; how nightclubs and independent spaces, especially for queers, have given way to fancy restaurants and wine bars, thereby sanitising Dublin’s nocturnal streets. The

central scene of the film is a party set in basement, with friends as guests and Bé as DJ. Filmed in August by Helio León, the film also includes Emma and I as spectral visions of James Joyce and Nora Barnacles in drag, transformed with makeup by Lor can Devaney. Unseen by the partygoers, we perform mainly as a pair, acting in impro vised tableaux while moving slowly through the space, our mouths illuminated.

The film is overlaid with text, spoken by three object characters – an eye, a rubber fist, and a snake – holding a parallel conver sation alongside and against the words of Joyce. The script was largely based on ‘Circe’, redeveloped through a writing exercise. We focused on language describing liquids, and the quite ableist descriptions of nameless disabled characters in the beginning of the episode. Through this technique, it was pos sible to begin unpicking the troubling and slippery language.

Oh Infamy was made possible by a won derful team. Ulysses 2.2 Project Manager Gráinne Pollak worked with us through planning and production, supporting with finance, communications, building rela tionships, and even acting as bouncer on the door of the party! Ulysses 2.2 Produc tion Manager Stephen Bourke, substituted by Tomás Fitzgerald for filming, played an essential role, arranging equipment, supporting installation, and also acting as bouncer. Oonagh Young provided invalu able insight into ‘Circe’ and the history of the Monto, and graciously hosted a party, a film set, and an exhibition. ADI’s Access Services Coordinator, Aidan Gately, and Executive Director, Pádraig Naughton, worked closely with us in providing access and support through planning and produc tion. This included how to host an accessi ble party and film shoot, whilst supporting captioning and audio description work. We hope that the film is a generous ode to the Dublin night – to the people who find solace in it, the spaces we’ve lost, and those that made them.

Iarlaith Ni Fheorais (she/her) is a curator and writer based between Ireland and the UK.

@iarlaith_nifheorais

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | November – December 202210 Columns

Arts & Disability

Iarlaith Ni Fheorais and Emma Wolf-Haugh, Oh – Infamy – we eat electric light 2022; image courtesy the artists.

Making Change Happen

Policy Residency Reflections on Making

DR SUHA SHAKKOUR AND JENNIFER LAWLESS OUTLINE THE ARTS COUNCIL’S EQUALITY, DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION ( EDI ) TOOLKIT.

AT THE CENTRE of the Arts Council’s Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Policy and Strategy, launched in 2019, was the firm belief that everyone who lives in Ire land should have the opportunity to cre ate, engage with, enjoy and participate in the arts. In other words, that access to the arts is a basic human right, regardless of a person’s age, civil or family status, disability, gender, membership of the Traveller Com munity, race, religion, sexual orientation, or socio-economic background.

While the policy commits to ensuring the inclusion of all voices and cultures that make up Ireland today, it also acknowledges that barriers continue to exclude individu als and communities from full participation and representation in the arts. Additionally, in the almost four years since the policy was published, it has become increasingly clear that these barriers are further compound ed when considered from an intersectional perspective, where multiple factors combine to amplify exclusion from the arts.

The Arts Council is committed to con tinuing to identify and dismantle these bar riers, and to support organisations seeking to do the same, all of which will ultimately lead to a more diverse and inclusive arts sector for artists, arts workers, audiences, and participants. The Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) Toolkit, developed in consultation with the sector, was pub lished earlier this year (artscouncil.ie). It is a direct action of the EDI Policy’s Action Plan, intended to support organisations in addressing these barriers and in building policies and action plans of their own.

The EDI Toolkit is a practical, working resource that guides organisations through a series of questionnaires, in order to: • Take stock of where they are cur rently in relation to EDI practice • Identify what they want to achieve • Outline how they can reach their goals

In designing the templates and tools pro vided, we acknowledge that every organ isation is unique, and so these templates can be adapted according to each organi sation’s needs and the stage they are at in the journey to embed EDI in their work. The EDI Toolkit takes a reflective approach and encourages organisations to view policy development as a continuous practice, rath er than an end in itself.

The first step in the process asks organ isations to consider their strengths and areas for improvement. This helps to build a picture of what the organisation has achieved to date and identify any areas that require intervention. This could involve, for example, looking at an organisation’s staff, decision makers and board members, to determine if they are representative of Ire land’s diversity. A resulting action could be to update hiring and selection policies to ensure current practices are not intention

ally, or unintentionally, exclusionary.

The Toolkit’s Artist Engagement and Audience Engagement self-audit ques tionnaires ask organisations to consider the artists they employ or commission, as well as the audiences or participants they attract, and ask: Is our organisation welcoming and accessible to all? Do we have clear goals and a clear vision of how we can improve inclu sion and diversity for the artists we employ and the audiences or participants we pro gramme for?

Providing a platform for direct consul tation with the individuals and communi ties whose voices, experiences and needs are not being heard, is essential to creating real and lasting change through the policy and action plans developed.

The insights gathered from the evalua tion and consultation process will inform the policy development and associated action points. It will further enable organ isations to prioritise their objectives, out line the resources required, and identify the timeline for delivery of their goals. One of the key elements in achieving these objec tives is to adopt a process of continuous monitoring and evaluation with clear lines of accountability and ownership of tasks, in order to keep track of progress and adapt and respond to changing priorities.

The EDI Toolkit also features a number of case studies from organisations in the sector. Each case study shares the steps the organisations have taken and are planning to take. They highlight the difference this has made to the organisations to date, and the most important learnings they have encountered on their EDI journeys thus far.

A common thread running through all of the featured cases studies is an openness to challenging how things are currently done, and an understanding of the need for continuous and honest reflection, adap tion and change. We hope they will inspire and encourage you on your own path, and we invite you to collaborate and to share knowledge and good practice with each other as we work towards eliminating dis crimination in the arts.

When we make policies and develop action plans – when we curate, produce, commission, fund and programme, with and for the full diversity of Ireland – the arts reflected back at us are all the rich er and more vibrant for it. But we cannot expect change to happen organically and of its own accord. Inclusion is active and responsive and deliberate. We all play a role in making change happen.

Dr Suha Shakkour is Arts Council Head of Equality, Diversity and Inclu sion. Jennifer Lawless is Arts Council Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Proj ects Officer.

artscouncil.ie

PAULINE KEENA DISCUSSES HER RECENT RESIDENCY AT BACKWATER ARTISTS GROUP.

LIKE MOST ARTISTS during lockdown, I spent two years working in isolation. In winter, my rural studio is freezing and almost impossible to heat, so I was delight ed to be awarded a two-week research res idency in Studio 12 at the Backwater Art ists Group in Cork City. Backwater Artists Group was founded in 1990 and is a key fixture in Cork’s cultural landscape. It is one of the largest and longest running artist-led initiatives in the country, which currently provides access to facilities and develop mental support for 64 artists.

Positioned in the heart of the city, the mission of Backwater Artists Group is to support and advocate for visual artists, enabling them to thrive at all stages of their careers, and empowering them to foster a deep appreciation and enthusiasm for the visual arts within society. Facilities include 28 studio spaces, a fully functioning dark room, an exhibition/project space (Studio 12), a computer meeting room, and wood work facilities. The premises is shared with Cork Printmakers and The Lavit Gallery.

BAN (Backwater Artists Network) was set up in 2019 to create a shared city-centre focal point, as well as opportunities to con nect for professional artists working in iso lation in home studios, or in privately rent ed studios. I became a member of BAN just before lockdown, as I wanted to be part of a bigger network of professionals to exchange ideas and develop new work. BAN supports artists through the provision of opportuni ties to sustain and develop artistic practice, including networking, exhibition and resi dency opportunities, learning and discur sive events, peer to peer critique sessions, a visiting curator programme, and more.

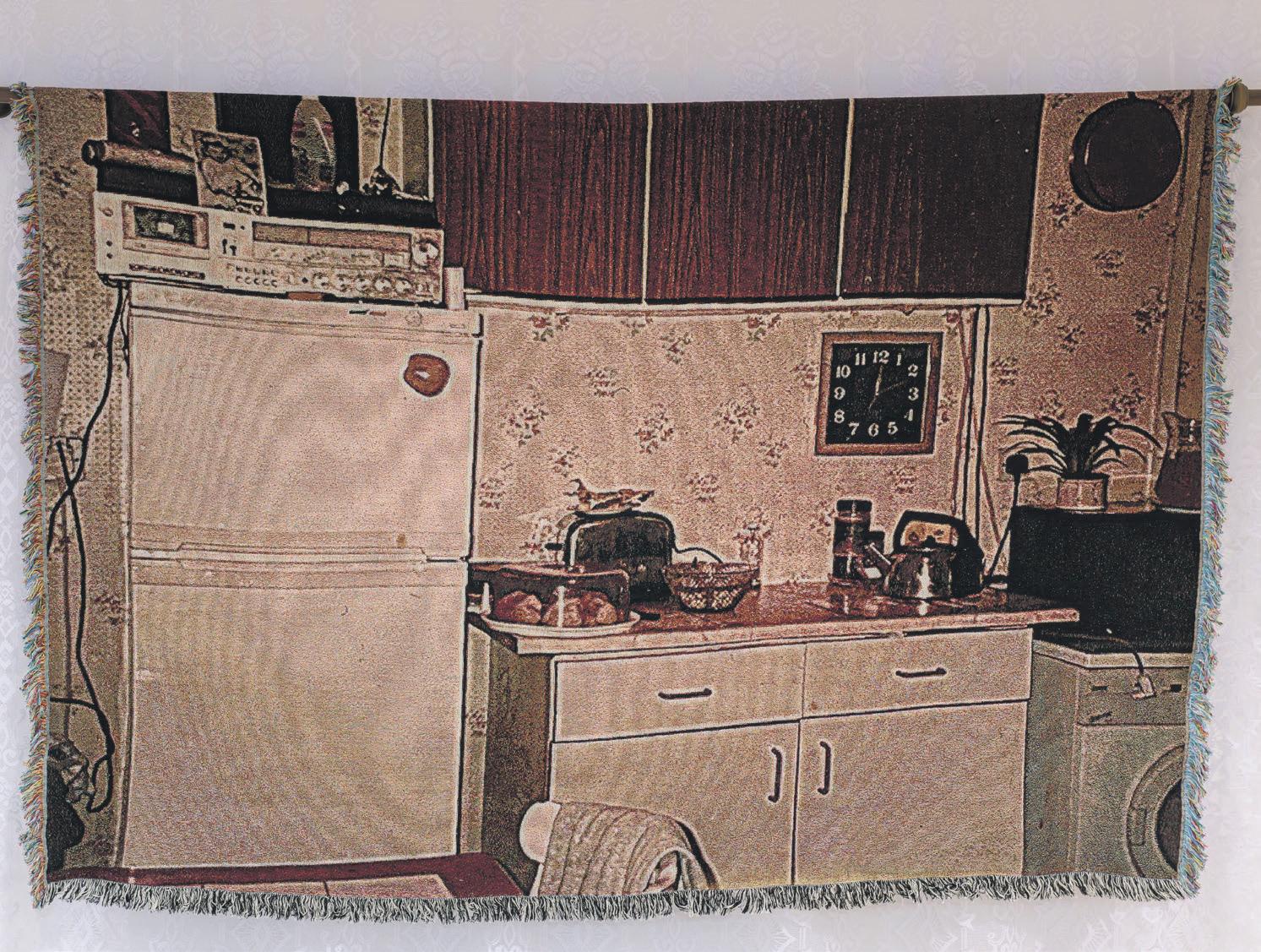

Studio 12 operates both as a site of exper imentation and exhibition, and as a public testing ground for new artworks and ideas. During my residency at Studio 12, I want ed to reengage with my drawing practice as part of a larger body of new work. Having spent a long period of time in my studio engaged in the painstaking task of stitch ing a large-scale and very heavy tapestry, my drawing practice had been neglected. So, I was delighted to have this large bright warm space on the first floor of the Back water building in which to start drawing again. Although the studio is very private, there are artists all over the building and we could meet during breaks in the communal kitchen area. It felt so strange and wonder ful to be meeting people in reality and not on Zoom.

I wanted to develop a series of new draw ings based on the failing body, by focusing on the skin as a porous boundary. Of course, drawing confronts me with many challeng es and questions, including: how do ideas manifest through the corporeal intimacy of materials? I wonder whether I draw because I find out something that isn’t available through other strands of artmaking. For

me, drawing is like a location; a commotion of place, where seeing becomes possible in a way that’s not available through other means. Drawing provides me with a very particular way of engaging with the work and seems to extend my knowledge by finding things out through the physicality of the process. This encompasses the fragil ity of the watercolours, the bold heavy lines, and coming to know something as I pro ceed – perhaps forgetting and remembering it again, when I observe what has happened in the process.

Connecting with other artists was a valu able part of the residency as well. One day there was a knock on my studio door and another artist was there wanting to visit and see what I was doing. Sean Hanrahan had recently finished a residency at IMMA in Dublin, where he created a project entitled ‘Flag Anthem’. We chatted about his work, the flag, what a flag may mean, what it rep resents, and what a country could be. We spoke about the importance of residencies for artists and the value of having space and time to think about the work. With a twoweek stay, there is no expectation to pro duce finished work; however, the value is in the space and time to think about it. I man aged to establish a new body of work that is at a reasonable stage and can be developed further in my own studio.

Finally, I had the opportunity to talk about the project. Several studio artists attended, and following my talk and film screening, a robust discussion took place, mostly focusing on our individual practic es, and the ways in which thinking devel ops through both making and reflection on making. I was very impacted by how art ists are truly valued in Backwater Studios and how the ongoing development of their work is central to the ethos of the organ isation – something that is largely due to the incredible work of the current director, Elaine Coakley.

Pauline Keena is an artist who is interested in the human form, in terms of its physicality, its power, its chaos and interiority. The Backwater Artists Group is funded by The Arts Council and Cork City Council.

backwaterartists.ie

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | November – December 2022 11Columns

Regional Focus

Galway City

Civic Contribution

Megs Morley Director, Galway Arts Centre

GALWAY IS ONE of the most vibrant cultural cities in Ireland, bustling with extraordinary talent, with artists from all over the world choosing to make this city at the utter most western edge of Europe their home. A highly internationalised city, it is also embedded in a region steeped in traditional culture and language. This unique context has nurtured an incredibly rich dynamic of creative practices, with Galway Arts Centre (GAC) playing a central role in the devel opment of this cultural ecology for over 40 years.

GAC was founded in 1981 by the Gal way Artists Group in a former Presbyterian church located in Nun’s Island, who initial ly renovated the church as a gallery space and theatre, the first of its kind in Gal way. In 1988, the former city residence of Lady Gregory on 47 Dominick Street was redeveloped by Galway City Council into a modern gallery for Galway Arts Centre. Since then, GAC has operated a cultural campus across these two venues as a mul tidisciplinary arts centre focusing on visual art, theatre, and literature.

Many of Galway’s most important cul tural organisations were initiated and devel oped by Galway Arts Centre, including TULCA Festival of Visual Arts, Galway Theatre Festival, Galway Youth Theatre, Cúirt International Festival of Literature, and many more. Along with this, former curators and directors such as Helen Car ey, Paul Fahy, Ger Ward, Michael Dempsey and Maeve Mulrennan to name but a few, developed important bodies of work that supported artists and played a central role in the cultural scene within the city.

As the new(ish) director and curator of GAC (since September 2021), I feel that this legacy is important for us to reflect on, as we embark on a new chapter in the development of GAC and the arts in Gal way. I believe the legacy of GAC extends far beyond its walls – it is more social, rhi zomatic, and radical. GAC is situated at the core of a delicate cultural ecology that has supported and nurtured so many artists and creative communities in the West of Ireland over the decades. This is a legacy that we are committed to continuing, growing, and expanding in the coming years.

This year has been challenging and exciting in equal measure for everyone in GAC, with the return to the first in-person Cúirt Festival in two years, as well as Gal way Youth Theatre’s return to the stage this summer, as part of Galway International Arts Festival. Opening the galleries again was a delight with Kevin Gaynor’s Currency Exchange (2022) last December, and with the 2022 visual art programme ‘Entangled Histories’ – which included artists Sarah Pierce, Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, Alice Rekab, Duncan Campbell, Denise Ferreira da Silva

and Arjuna Neuman – as well as solo exhi bitions by Declan Clarke and Sean Lynch. We have developed a new Artists-in-Resi dence scheme, through which we have supported the work of Éireann and I, Pavithra Kannan, and Rewind Fastforward Record.

Undoubtedly one of the highlights of our year was bringing the Turner Prize-winning work The Druthaib’s Ball by Belfast-based collective, Array, to GAC in August. This immersive installation, which celebrates collectivity and activism and highlights human rights issues in Northern Ireland, was installed in our performance space in Nun’s Island Theatre, with a wider concur rent exhibition by Array in our galleries. To bring that work to Galway was a huge col lective venture in itself, involving extensive partnerships at local, national, and interna tional level. Opening the exhibition in part nership with Galway Community Pride was an incredible and joyous event, with Array and their peers from Northern Ire land marching with local Galway groups.

Our public engagement programme was hosted in the installation itself, which takes the form of an illegal bar, or sibín, and comprised over 25 performances, discus sions, talks, and workshops over the dura tion of six weeks. This opened the space for the public to engage in deeply reso nant, complex discussions and experiences that variously unearthed LGBTQ+ histo ries in Galway, explored the politics of the North, the social history of traditional song, the activism inherent in storytelling, the transgressive practices in Irish wakes, and the creative potential and joy of working together collectively.

We look forward to an exciting pro gramme next year at GAC, which includes a solo exhibition by The Otolith Group, a new open-call Artist-in-Residence pro gramme, an innovative sound project by Red Bird Youth Art Collective with artist Anne Marie Deacy, a contemporary choral theatre project by Galway Youth Theatre, the first edition of the Cúirt festival pro grammed by new festival director Manu ela Moser, and much more. We also very much look forward to our ongoing and long-term partnership with Galway City Council, which has resulted in a signifi cant capital development investment in our performance space in Nun’s Island. Works begin in 2023 and will redevelop the site to provide much needed rehearsal, production, and performance space in the city, as well as making a crucial contribution to civic space for public participation in the arts.

galwayartscentre.ie

galwayartscentre.ie

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | November – December 2022

Array collective participating in Galway Community Pride Parade, prior to the launch of The Druthaib’s Ball, 13 August; photograph by Tom Flanagan courtesy Array and Galway Arts Centre.

Array, The Druthaib’s Ball, 2021, installation view, Nun’s Island, Galway; photograph by Tom Flanagan, courtesy Array and Galway Arts Centre.

Array collective, first-floor gallery, Galway Arts Centre; photograph by Tom Flanagan, courtesy Array and Galway Arts Centre.

Engage Art Studios

Rita McMahon Managing Director

FOUNDED IN 2004, Engage Art Studios is dedicated to providing studios to profes sional visual artists and has become an inte gral part of the Galway visual arts scene. As an organisation, Engage has developed and grown a lot over the years, expanding and relocating in order to continue to provide support for professional visual artists in the development of their practices.

Our goal has always been to offer afford able, secure, well-lit, and private studios, as well as to foster an atmosphere of creativity, production, inspiration, and opportunity for working artists in the Galway area. Engage has created, and continues to maintain, a supportive environment of productivity and creativity. Engage has become a vital part of the Galway creative landscape.

In 2017, we opened a second premises with six studios on St. Francis Street in the city centre, in addition to the studios in The Cathedral Building on Middle Street. However, in 2019, Engage faced immense upheaval when we were forced to vacate the Cathedral Building studios due to an unaffordable and unsustainable rent hike. Thankfully, the move, while extremely chal lenging, had a prosperous outcome in the discovery of the new premises in Church fields, Salthill, where Engage Art Studios remain at present.

The new space in Salthill allowed us to increase the facilities available to our mem ber artists, and provided us the opportu nity to expand our exhibition and event programming, as well as our education programme. In Churchfields, we now have a gallery space, project workspace, seven single-occupancy studios, a hot desk area and digital suite, small library, storage and kitchen utilities, and space to expand into printmaking facilities and a darkroom.

We have been able to expand our educa tion programme in the form of weekly chil dren’s art classes, provided by our education co-ordinator, and adult workshops run by member artists and invited facilitators. This has allowed us to establish Engage as

a resource for the community as well as a creative hub.

With this dramatic increase in supports that we can offer, we have been able to sus tain over 30 artists working in the Galway area, providing 13 physical studio spaces, and Orbital Membership to over 20 art ists, allowing them to avail of all benefits of the studios common spaces and services, including professional practice opportuni ties, talks, exhibitions and peer-based cri tiques.

It is not only the physical facilities that we offer, but the secondary supports that make Engage a vital resource for visual artists in the region. As an organisation, we aim to continually develop and grow our model as the needs of artists working and living in Galway evolve. As a cultur al hub, Galway thrives; however, the visual arts in the region need to be nurtured and supported by organisations, community, and government funding bodies. I strongly believe in the power of partnership, partic ularly through the connection of artists and networks of organisations in a small city such as Galway.

One of my aims when I was appointed as director of Engage in 2021 was to maintain good relationships with like-minded spac es, both locally and nationally, to continue to foster partnerships. Thanks to the sta bility of securing a dedicated arts premises within the city, we can now further engage with the programming of exhibitions and events in our space and in collaboration with other organisations, the many festivals in Galway, national cultural programmes, exchanges and collaborations with other studios and galleries. The collaborations we have undertaken, along with our longstand ing dedication to providing workspaces for artists, have allowed Engage Art Studios to develop into a flagship visual art facility and an essential pillar of the cultural infrastruc ture of Galway.

engageartstudios.com

Evolution of Artist-Run

Lindsay Merlihan Director, 126 Artist-Run Gallery & Studios

THE SEASON AND the time of day are indis cernible within the misty wet of anoth er grey day in Salthill. The full moon has brought hightide and you’re feeling auda cious, looking down from Blackrock Diving Tower. The wind has howled a hundred “will I, won’t I’s” but you’ve just publicly emerged from the awkward towel chrysalis of a tog change and find yourself ready to spread those wings…LEAP! Mid-air thoughts go something like: “Weeee!” and “Fuuuck!” then “Sploosh!” into the deep end.

That’s what it’s like to join an artist-run space. There’s no preparation for the plunge that leads innocent creatives into the immersion of artist-run. It’s trial by fire and explosive creativity; it’s investing oneself by means of service to the arts. It’s teamwork, growth, compromise, firefighting; it’s doing tedious admin, and experiencing moments of awe, completion and success. It’s anx ious existentialism of funding applications, and sacrificing time from one’s personal arts practice, whilst gathering the experi ence and knowledge for its success. It’s a 24-hour Whatsapp group; it’s ambitiously bringing into focus the radical, emerging arts that lie on the fringes. It’s brilliant mayhem. You can learn all about it in our book, Artist-Run Democracy: Sustaining a Model (Onomatopee Projects, 2021) edited by Jim Ricks.

126 does not operate like a normal gal lery or museum. We rely on the support of our membership programme and the efforts of a voluntary board of directors, who each serve a two-year term. The organisation, at its very foundation, is always changing. For a brief period, I have the honour of stoking the 126 fire.

In 2013, the winds of Chicago blew me into Galway with a backpack and here I am nearly ten years later. Just another blow-in who chose to stay, contributing to the ever-changing landscape of Galway. My first years were spent adjusting to the wild west, making genuine connections to some whom have come and gone. But, like the tide, my relationship to Galway has changed. The ebb of life’s waters has since withdrawn me from the town centre, and poured me into the edges of Connemara, where my Michigan-born soul is soothed

by nature and where I can (just barely) afford the rent. Engaging with this spe cial place through a mixed-media practice, informed by studies in Depth Psychology and art therapy, has certainly impacted my contribution to 126.

I am one of six directors of the current, unintentional, all-female board. I suppose that for all the boards of men that we’ve seen administrate the world, a few months of women conjuring spells in 126 won’t hurt. It is up to every new wave of direc tors to determine their values. What is the role of the gallery? What is emerging in Irish culture that needs to be seen, heard, or experienced, and who is reflecting that in their practice? How might we ethically play the role of cultural producers while awkwardly navigating our own learning experience? What matters to us and why?

By a stroke of luck, our current board share a lot of the same values in cultur al programming. This is something that anchors us. While writing our 2023 pro gramme, we discussed how the land-based rituals of our Irish ancestors contributed a meaningful culture. We discussed how might we link the ancient past to practices relevant in the digital age. We spoke about ecological biodiversity, racial inequality, threats to marginalised communities, and consequentially, the loss of a soulful life. How can we connect again to this human spectrum through the multifaceted lens of immersive arts?

In extending our view to include art forms that stimulate a wider range of sen sory activation within singular exhibitions, we began to think of the gallery as a place where polarities meet. This alchemical function of the gallery is where we centre our 2023 programme. The current director ship of 126 is here, if only for a moment in time, as a vessel for transformation, and we thank Galway for engaging in this contin uous evolution.

Visual Artists’ News Sheet | November – December 2022 13Regional Focus

126gallery.com

Exterior of 126 Artist-Run Gallery and Studios; image courtesy of 126 Artist-run Gallery and Studios.

Exterior of Engage Art Studios, Galway; image courtesy of Engage Art Studios.

New Directions

Kate Howard Galway City Council Arts Officer (acting)

GALWAY CITY COUNCIL was one of the first local authorities in the country to establish an arts office and is the key agency for the development and support of the arts in the city. Galway City Arts Office has seen some changes and developments since the retire ment of Arts Officer James C. Harrold in 2021 – a position he had held for over 20 years. Gary McMahon took over the reins in the autumn of 2021 and I joined the Arts Office team in July 2022.

My connection with Galway spans over 20 years. I have worked with many of the city’s arts organisations and communities, as producer of TULCA Festival of Visual Arts; producer of Arts in Action – a pro gramme at NUI Galway led by the late Mary McPartlan; as National Campaign for the Arts (NCFA) constituency coor dinator and steering committee member; as arts representative for the Galway City Council Strategic Policy Committee; as Cultural Producer with Galway 2020; and as a founding director of Culture Works.

Galway is a proud city. Its people and culture are a central part of the city’s identity and one of its greatest strengths. Embedded in and enveloped by its county hinterland, Galway has a rich creative scene that provides a distinctive, welcoming, and inspiring environment. The city supports a diverse range of cultural activities with a highly capable and confident arts sector. This has grown over the years in ambition, capacity, and reach, supported by the desig nation of European Capital of Culture in 2020, which was also the impetus for cre ating one of the first cultural strategies in the country.

With my knowledge of the local cultural landscape, I am acutely aware of the chal lenges and the opportunities facing the arts in Galway City. These are clearly outlined in Galway City Council’s New Directions: Strategic Plan for the Arts 2021-2026, which was adopted by the Elected Members of City Council in May 2021. This policy document (itself informed by the Cultur

al Strategy Framework, Everybody Matters 2016-2025) forms the basis for the work of the Arts Officer and Arts Development Officer. It prioritises the engagement of children and young people and supports local communities to access and partici pate in arts and culture, while recognising and supporting the innovative, collabora tive, international and world-class artists, creative individuals, and arts and culture organisations and groups.

Galway City Arts Office engages with contemporary creativity in the art forms of architecture, circus, dance, film, litera ture, music, opera, street art and spectacle, theatre, traditional arts, and visual arts. We work in practices that cross art forms to encompass venues, young people, children, education, arts and health, arts and disabil ity, socially engaged art and artist’s support. The Arts Office is active in its support of engagement, production, and dissemina tion through the medium of the Irish lan guage, recognising that both contemporary and traditional arts are key elements in the diverse culture of our city. The programmes, projects and organisational supports for arts and culture are funded by Galway City Council from its annual budget, and through funding from The Arts Council, Creative Ireland, The Department of Tour ism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, as well as from other government departments and national agencies.

I feel honored to be working with and supporting the Galway City arts commu nity, the communities they work with, and my colleagues in Galway City Council on the implementation of the Cultural Strat egy, the Arts Plan, and the fostering of Galway’s character and culture through the City Development Plan. The Arts Office recognises and understands the principles crucial to its sustainability, and it promises to support its creative citizens and commu nities into the future.

galwaycity.ie

Full Steam Ahead

Anne Marie Deacy Visual Artist

I AM A Galway-based artist and field recordist with a background in music and experimental sound making, as well as in the collective DIY subcultures that are the soul of Galway City. Just before there was any talk of a pandemic, I was awarded a bursary as part of the Galway County Arts Office 2019 Support Scheme. This support was invaluable, and the funding was used to create a sound postcard. On one side, there was an embedded 90 second field recording of church bells; the card was to be posted and played like vinyl on a record player at 45rpm.

Sound as activism is a theme that per meates the work of many sound artists, and I am no different. This sound postcard was my response to the disappearance of regional bus routes, the closing of hun dreds of post offices, churches, and pubs that are a lifeline for so many, with nothing replacing these social hubs that are steeped in connection, community and ritual. The sound postcard has since travelled to differ ent continents and gone beyond anything I could have ever imagined. When played on art radio stations, it has popped up as a social commentary on a much broader scale.