32 minute read

VFX TRENDS: PRACTICAL EFFECTS

THE RESURGENCE AND REVITALIZATION OF PRACTICAL EFFECTS

By IAN FAILES

TOP: Legacy Effects crafted a robotic arm for the character George Willard (Paul Schneider) in Tales from the Loop. (Photo by Jan Thijs, courtesy of Amazon Prime Video)

BOTTOM: The Jakob robot was both a practical on-set puppet built by Legacy Effects and a digital creation made in VFX for Tales from the Loop. (Photo courtesy of Amazon Prime Video) You might be able to do anything in CG, but in recent times there has been a major resurgence in the audience and filmmaker demand for physical effects. VFX Voice looks at the state of play in this field of filmmaking with a range of creature and makeup effects practitioners, special effects supervisors and model and miniature makers.

THE STATE OF PLAY IN PRACTICAL EFFECTS

The diverse range of work covered by practical effects – animatronics, prosthetics, puppetry, mechanical effects, pyrotechnics and more – means that artists need to rely on a varied range of approaches to achieve them. Several innovations have led the charge in the past few years.

“3D printed clear materials are fantastic for visors and helmets, and sintered metals have now become cost-efficient,” identifies Legacy Effects Co-owner and Animatronics Effects Supervisor Alan Scott, whose recent experience includes overseeing robotic arms and robots for Tales from the Loop. “Also, new robotic servos have really transformed a lot of what we’re able to do with animatronics. We could have 12 of them working and moving for the robotic arm in Tales and it didn’t affect dialogue once.”

Weta Workshop Co-founder and Creative Director Richard Taylor concurs, stating that “over 60% of all that we make today utilizes robotic manufacturing technology.” The studio has had a hand in several practical robot and costume builds in recent films such as Ghost in the Shell, I Am Mother and The Wandering Earth.

Special Makeup Effects Artist and Supervisor Jason Hamer of Hamer FX, which delivered full-scale and miniature water creature builds for Wendy, also agrees. “I think the use of digital artwork and 3D printing has been the biggest game-changer. The level of detail and precision that can be achieved is astounding. Mechanical parts that used to take weeks to machine can be produced at a fraction of the time and labor cost.”

Silicones, a makeup effects material used for some time, have come a long way as another go-to material, adds Amalgamated Dynamics, Inc. (ADI) Co-founder and Character Effects Artist Alec Gillis, who counts Bright and It as the studio’s latest highlights. “For a while, there weren’t really paints that would stick to silicone, but now the quality has just skyrocketed.”

Gillis’ ADI partner, Tom Woodruff, Jr., offers up a slightly different change in the state of play in creature effects, where studios with extensive experience in the area have been called upon to tackle direct digital design work. “Director Michael Dougherty had us and other studios do just the designs for Godzilla: King of the Monsters, which started as clay sculpts and ended in ZBrush.”

What has changed, too, is the use of digital techniques to drive what gets built practically, as Creature and Special Makeup Effects Supervisor Neal Scanlan’s studio undertook for several recent Star Wars films. “I decided the thing to do was to flip it the other way around and to use digital technology as a huge assistance in the builds. It liberated us in a way that we could never have done during the ‘analog’ period.”

At KNB EFX Group, partners and Special Makeup Effects

Artists Greg Nicotero and Howard Berger have been busy with large projects like The Orville, The Walking Dead and Space Jam: A New Legacy, while also approaching the management side of the business in new ways. “I wanted to diversify a little bit about nine years ago,” says Berger, “so I started department heading, where I run the whole makeup and effects department. It’s been a great and new experience.”

A feature of the creature effects experience is being able to have

TOP: For Hitchcock, Howard Berger helped transform Sir Anthony Hopkins into the famous director. (Image courtesy of Howard Berger)

BOTTOM: Lead Application Artist Christopher Nelson, left, actor Joel Edgerton and Makeup Effects Artist Joe Badiali work on Edgerton’s orc makeup for Bright. (Image courtesy of Amalgamated Dynamics, Inc.)

TOP: The Rise of Skywalker character Babu Frik was a rod puppet operated on set by greenscreen-clad puppeteers, and also operated by its voice-over artist, Shirley Henderson. (Image copyright © 2019 Lucasfilm Ltd)

BOTTOM: Creature and Special Makeup Effects Supervisor Neal Scanlan, left, with Star Wars: Rise of Skywalker director J.J. Abrams discussing the mono-wheel droid D-O. (Image copyright © 2019 Lucasfilm Ltd) something on set during production, with DDT Efectos Especiales Co-owner and Special Effects Makeup Artist David Martí noting that directors have made a concerted effort to incorporate practical creations further into the actor experience. “On A Monster Calls, J.A. Bayona had the creature there and he would even do a special introduction to it for everyone. It wasn’t just another animatronic thing, it was another actor.”

Like the creature effects specialists, The Grand Budapest Hotel and Isle of Dogs modelmaker Simon Weisse has been utilizing 3D printing in his miniatures work, as well as 2D milling. “We are using 3D printing with liquid resin, and also doing 2D milling. You can very quickly cut shapes in metal, wood or whatever you need.” Weisse notes, however, that he uses 3D printing and 2D milling only as part of a wider range of available tools among other handcrafted techniques.

Fellow modelmaker Mike Tucker from The Model Unit, with credits on projects such as Good Omens, Doctor Who and Gerry Anderson’s Firestorm, identifies improvements in high-speed digital cameras as a major change, too. “We were constantly being pressured to move away from film, but the fact was that until ARRI came up with the Alexa, there was no camera that really did the job the way that my DP and I wanted. The Alexa was a game-changer.”

For special effects supervisors, leaps and bounds have come in areas such as computer control. “We use computers to control hydraulics, pneumatics, computerized winches – right across the board,” says Special Effects Supervisor Chris Corbould, who recently worked on No Time To Die, one of several James Bond

films on which he has overseen the special effects. “Computer control gives us consistency. Once you press the button, it’s going to do exactly the same thing every time.”

The use of a rotisserie rig on Terminator: Dark Fate by Special Effects Supervisor Neil Corbould, VES, exemplifies that same precision in engineering now common in practical effects. “A lot of those rigs just rotate on one axis, but I wanted to make it a little bit harder for myself and have it tilt in as well,” he says. “It took eight months to design and build and weighed upwards of 85 tons.”

Special Effects Supervisor Jeremy Hays even had to craft an actual flowing river for The Call of the Wild after he had previously supervised a raging storm on The Equalizer 2. “The river contained approximately 355,000 gallons of water,” he says, “and had a water circulation rate of approximately 75,000 to 80,000 gallons per minute.”

Water was also a requirement for Special Effects Supervisor Joel Whist on Bad Times at the El Royale. Here he was called upon to deliver a large indoor rain sequence. “We filled the entire soundstage with 42 rain heads. We were dropping 2,000 gallons a minute on the floor, and for all that water we had to design the set so it was sloped and [the water] re-circulated.”

WHERE DIGITAL AND PRACTICAL MEET

Certainly, digital visual effects have edged their way into being the predominant effects solution today. But that doesn’t mean practical has lost its place in filmmaking. Instead, the common theme noted by the experts VFX Voice talked to was that early

TOP: For The Call of the Wild, Jeremy Hays orchestrated the building of an actual flowing river set for shooting scenes involving panning for gold, swimming and canoeing. (Image courtesy of Jeremy Hays)

BOTTOM: Weta Workshop Co-founder and Creative Director Richard Taylor works on Geisha molds for Ghost in the Shell. (Image courtesy of Weta Workshop)

TOP: Special Effects Supervisor Chris Corbould on set during the making of Spectre. (Image courtesy of Chris Corbould)

MIDDLE: Mike Tucker’s The Model Unit provided a large-scale model of a missile silo, missile and a surface hatchway for Good Omens. (Image courtesy of Mike Tucker)

BOTTOM: For Bad Times at the El Royale, a completely interior stage was rigged with rain machines by Joel Whist’s team to provide continual on-set rain. (Image courtesy of Joel Whist) discussions between the visual effects and practical effects teams always lean towards simply what works best for the story and the shot.

Practical effects practitioners have also been conscious of a feeling out there that CG could accomplish the things that they had been doing for so many years, and cheaper. However, in the past few years it has become clearer that both approaches have different aesthetic and cost benefits.

“I have always seen the strong want and desire to use practical effects in filmmaking and that the trend seems to swell and fade with the various styles and genre of movies that are being created at the time,” observes Hays. “With any creative, ever-evolving industry, fluctuations in the methods of telling the story are to be expected, and really should be welcomed.”

“Some areas have certainly changed over the years, such as miniatures,” acknowledges Taylor. “This was the largest department at the Workshop for the first 20 years of our company, but due to the versatility of digital solutions for architecture in film today our miniature department has become smaller, relative to our other departments. Thankfully, many directors continue to enjoy working with practical effects on set, and I believe that this will be an ongoing aspect of filmmaking for many years to come.”

“I think we’re probably stronger now than we have been in many years,” declares Neil Corbould, whose recent projects include the latest Mission: Impossible films. “To work on these films is a practical effects person’s dream; they want Tom Cruise to do as much in-camera as possible. There is a lot pushed into practical effects, and my input is greatly appreciated by them and the visual effects supervisor as well.”

“I’m excited anytime I hear somebody say that there is a resurgence in practical effects,” offers Woodruff, Jr. “Well, it’s not really a resurgence, some people say, it’s just a balancing out, but I think it is a resurgence.”

Scanlan is also adamant about the advent of a new wave of practical effects. “I was of the opinion that in so many ways practical effects had run their course. But then when I got that call from J.J. Abrams, it was clear to me that there was a way to make a number of magical ingredients come together for the new Star Wars films.”

In fact, the on-set collaboration between visual effects and practical effects is incredibly close, attests Chris Corbould, who has also recently been concentrating on second unit directing during production. “I always get together with the visual effects people and we discuss what the best way to do it is and what would look best rather than just, ‘Oh, it’s got to be CG.’”

Scott shares that belief, and Legacy Effects has certainly borne witness to that collaboration recently on projects such as The Mandalorian, where both a puppet version and digital version of baby Yoda were used, and on Tales from the Loop where the VFX team, says Scott, “embraced what we could provide knowing full well that there were going to be times where we’re not going to be able to do what is required.”

“You know,” shares Berger, “my first question is always, ‘Who’s your VFX supervisor?’ Sometimes they have to call the shots on everything, and I want them to. I might be on a project for six

months, but they’re often on for a lot longer and they have to live with the decisions that get made.”

Meanwhile, Whist sees practical work as being the source of authenticity in a scene, an approach he followed for the blood squib hits in season one of Altered Carbon. “There is just something about the weirdness of shooting on set that makes a blood hit look a bit more random, but of course they are often augmented as well.”

“My first job on any production is to point out what miniatures can offer that digital can’t, whether that be the quantity of shots that we can deliver, or just the raw, organic nature of a practically-achieved effects sequence,” outlines Tucker, saying his experience is that sometimes people see miniatures and just assume they’re digital, even when they’re not.

Hamer argues that a practical approach can also bring unexpected results, such as the solution found to illuminate an area of the ‘Mother’ creature in Wendy. “To do this we attached a series of LED panels on a fiberglass core and sealed in caulking. The wires were sealed in silicone tubes and ran up the control rods to the surface where they connect to a laptop running a lighting program.”

For Weisse, and several other modelmakers, his miniature work often has significant crossover with the physical production on a film, as it did on the stop-motion Isle of Dogs. “They built around 200 sets at seventh scale and then we had about 35 sets done at much smaller scale. They both worked in different ways.”

Martí’s experience on A Monster Calls was that an original push to construct things practically segued into a mostly CG solution. However, what had been built served as extensive practical reference for the actors. “It helped create the mood for the scenes, and it was great they could get in there and touch it. We were happy to be helping to make that magic on set, but it is the case that 95% of the shots in the film were CG.”

“Most people just want it to be awesome,” comments Gillis. “They want it to be big and cool. People do get really excited if you say, ‘We used practical,’ but then if you also say, ‘It’s embellished with digital,’ people also get very excited about that. I think the blend is really where everything elevates beyond the limitations of any one technique.”

TOP LEFT: Neil Corbould’s rotisserie rig designed for the aerial fight sequence in Terminator: Dark Fate. (Image courtesy of Neil Corbould)

TOP RIGHT: Modelmaker Simon Weisse in front of the 18th-scale hotel constructed for The Grand Budapest Hotel. (Image copyright © 2014 Fox Searchlight)

MIDDLE: Special Makeup Effects Artist and Supervisor Jason Hamer works on a makeup effects appliance for a Die Antwoord music video. (Image courtesy of Jason Hamer)

BOTTOM: DDT Efectos Especiales’ Montse Ribé and David Martí work on a character from Crimson Peak. (Image courtesy of David Marti)

DYNAMIC DUOS: DP AND VFX – CALEB DESCHANEL AND ROB LEGATO

By IAN FAILES

All images copyright © 2019 Disney Enterprises, Inc. On a traditional effects-driven film, a cinematographer and a visual effects supervisor might tend to collaborate predominantly on set on individual visual effects shots, and rarely into post-production.

This was the reverse on Jon Favreau’s The Lion King, a photorealistic, computer-generated re-imagining of the classic 2D-animated Disney feature, where Director of Photography Caleb Deschanel, ASC and Visual Effects Supervisor Rob Legato, ASC worked together on every single shot of the film.

Such a collaboration was possible owing to the virtual production nature of the shoot, in which virtual cameras and equipment (which matched real-world versions), real-time rendering, motion capture and virtual reality (VR) scouting and reviews became the filmmaking tools.

GOING VIRTUAL

Over several film experiences, including on Bad Boys II, The Aviator, Avatar, Hugo and The Jungle Book, Legato (a three-time Oscar winner and five-time nominee) has been a pioneer in the use of virtual production techniques. It was something he looked to take to a new level on The Lion King.

“I wanted to make sure,” says Legato, “that the working environment that we were in was collaborative enough that Caleb could say, I have this crazy idea, I want to do this, let’s go do that. As opposed to saying, ‘It can’t be done.’ All of a sudden, in my experience, you will find a shot that’s even better.”

“What made it really easy for me,” comments Deschanel (a six-time Academy Award-nominated cinematographer for films including The Right Stuff and The Natural)”, “was that Rob and the people at Magnopus [the studio behind the virtual production

“The big thing in making the movie was the fact that the tools were very familiar and were designed to mimic a hundred years of filmmaking and all the things that we’ve learned over that period of time to make movies. Beyond that it was up to your imagination to see how you could piece those things together in interesting ways to go beyond that and get out of your comfort zone and try different things. And if it failed it didn’t matter because you could press a button and start over again and try something else.” —Caleb Deschanel, ASC, Director of Photography

tools] designed things that were so much like what I’m used to. I didn’t need to reinvent things that I didn’t know. It was lenses, it was dollies, it was cranes. The two of us could then just concentrate on thinking, ‘How do we tell this story?’

“And the great thing about the world that we were in, this virtual world, was that, you could try infinite things,” continues Deschanel. “You didn’t have to wait for the wranglers to take the wildebeest back to the first position, because you just pressed the button and they were there. So this really gave us a lot of freedom that really made it much more exciting than I expected it to be.”

The intention of those tools was to replicate the kind of spontaneous filmmaking that occurs on a live-action set and ultimately produce a closely-followed template of action and lighting for editorial and for visual effects studio MPC to complete the final shots. The result was that The Lion King could be shot with all the principles – and restrictions – of live-action filmmaking in mind, but without having to train animals or film in challenging environments.

“It was quite a bit different than I expected it to be,” Deschanel

OPPOSITE TOP: The Lion King Director of Photography Caleb Deschanel, ASC, left, and Visual Effects Supervisor Robert Legato, ASC, right, during a reference photography trip in Africa.

TOP: Deschanel on location for the Africa shoot.

BOTTOM: The Lion King director Jon Favreau, Deschanel, Production Designer James Chinlund, Animation Supervisor Andy Jones and Legato discuss the film.

“I’ve been doing this for a long time, but I’m still learning from the masters how to light something, how to compose something, how to shoot something, how to operate something and how to create an emotional effect with cinematography. So with Caleb I could be a student, and I’m a collaborator at the same time and appreciate both spectrums. It was a perfect storm for me.” —Rob Legato, ASC, Visual Effects Supervisor

TOP: Young Simba, Timon and Pumbaa. Deschanel found new ways to film some of the scenes with these characters virtually.

MIDDLE: Scar gets a visit from Mufasa and Zazu. Key lighting decisions were made during the virtual cinematography stage.

BOTTOM: MPC’s final elephant graveyard shot. says of his The Lion King experience, which involved collaborating with Legato and the filmmaking team largely on a purpose-built capture stage in Playa Vista. “I guess I had really no idea what I was getting myself into. It turns out it was like making a regular movie in the most wonderful way, without the dangers of being attacked by lions or getting heat stroke or any of the other things that are the by-products of shooting out in the real African savanna.”

Legato notes that one of the key areas of collaboration came from being able to scout proxy landscapes and shots in VR. This could be done with multiple people donning VR goggles at the same time. “We could go into VR, take a quick peek at the environment, and then as we were operating the camera or making suggestions, we’d know where we were because we’d seen it.”

CINEMATIC SOLUTIONS, VIRTUALLY

The new virtual production paradigm gave Legato and Deschanel ample opportunity to make scenes that followed traditional cinematography techniques, or use them in different ways. One example was being able to experiment with virtual Steadicams, or even repurposing pre-animated characters in the scene as ‘cameras’ themselves.

“The big thing in making the movie was the fact that the tools were very familiar and were designed to mimic a hundred years of filmmaking and all the things that we’ve learned over that period of time to make movies,” outlines Deschanel. “Beyond that, it was up to your imagination to see how you could piece those things together in interesting ways to go beyond that and get out of your comfort zone and try different things. And if it failed, it didn’t matter because you could press a button and start over again and try something else.”

Another example was sun position, something that could have always been kept in a realistic spot between different shots. But, notes Deschanel, “we literally moved the sun in every shot. What I discovered was that if you just left the sun in the same place, you’d come around to a different angle and it would never feel right. So we would adjust the sun in every shot to feel like the other shot. It was never to destroy the sense of reality, but it was actually to enhance the sense of reality.”

A further discovery was the importance of realistic focus pulling

and dolly moving in the virtual cinematography. Although those kinds of things could be achieved ‘in the computer,’ Deschanel and Legato ultimately sought to have them done on the capture stage with trained focus pullers and dolly grips. It also ensured that seemingly simplistic filmmaking methods prevailed, despite the fact that the camera and characters could literally do anything in CG.

“For example,” describes Legato, “there’s an early introduction of Scar that I particularly liked where the staging is outrageously simple. It’s a mouse on a vine and Scar just walks forward. But what makes it magical – what makes it cinematic – is depth of field. Scar is merging from dark to light and the light hits him exactly right. The focus being pulled at exactly the right time creates this piece of cinema that belies the simplicity of the staging.

“Here, the operator is the audience, the focus puller is the audience, the grip is the audience,” attests Legato. “If the filmmaker is doing it correctly, you automatically look where you’re supposed to, even if it feels invisible. It’s an intangible thing that you see in good movies with good filmmakers.”

This also played into one of the duo’s goals for The Lion King – to try and avoid the perfection that could easily be achieved in a CG film. “In fact,” says Legato, “whenever you’re shooting something, you try for perfection and you can never get it. The sun might not behave or the actor might miss their mark or the dolly grip might be a little late. But that’s human and that’s life. In the computer, you get everything perfect, but you don’t want it.”

So, the idea of the virtual camera tools on the stage was, in part, to provide for the ‘happy accidents’ that happen on a real set. Even though the filmmakers could do multiple takes to try and get the best shot, they invariably would return to the take that felt the most natural.

“All those elements added to that feeling that the film was handmade,” suggests Deschanel, “that the focus was there and the decisions were made based on what you’re seeing on the screen and not just based on some computer deciding that, okay, now it’s time to switch to the next character.”

LEARNING FROM EACH OTHER

Both Deschanel and Legato say they were able to push each other further as filmmakers during the making of The Lion King, both in a technical and aesthetic sense.

“I’ve been doing this for a long time, but I’m still learning from the masters how to light something, how to compose something, how to shoot something, how to operate something and how to create an emotional effect with cinematography,” says Legato. “So with Caleb I could be a student, and I’m a collaborator at the same time and appreciate both spectrums. It was a perfect storm for me.”

Deschanel returns the sentiment. “Part of what makes Rob amazing, aside from his visual sense and wonderful sense of storytelling, is also his understanding of all the tools and all the things that we use to make movies. It just became this wonderful, embryonic fluid of creation. It was really amazing. It was really a lot of fun.”

TOP: At right, Deschanel and Legato review using Magnopus-built tools to capture a scene.

MIDDLE: The Lion King director Jon Favreau, right, with Director of Photography Deschanel.

BOTTOM: Deschanel grips a hand-held virtual camera on the shooting stage.

DYNAMIC DUOS: SFX AND VFX – DOMINIC TUOHY AND ROGER GUYETT

By IAN FAILES

All The Rise of Skywalker images copyright © 2019 Lucasfilm.

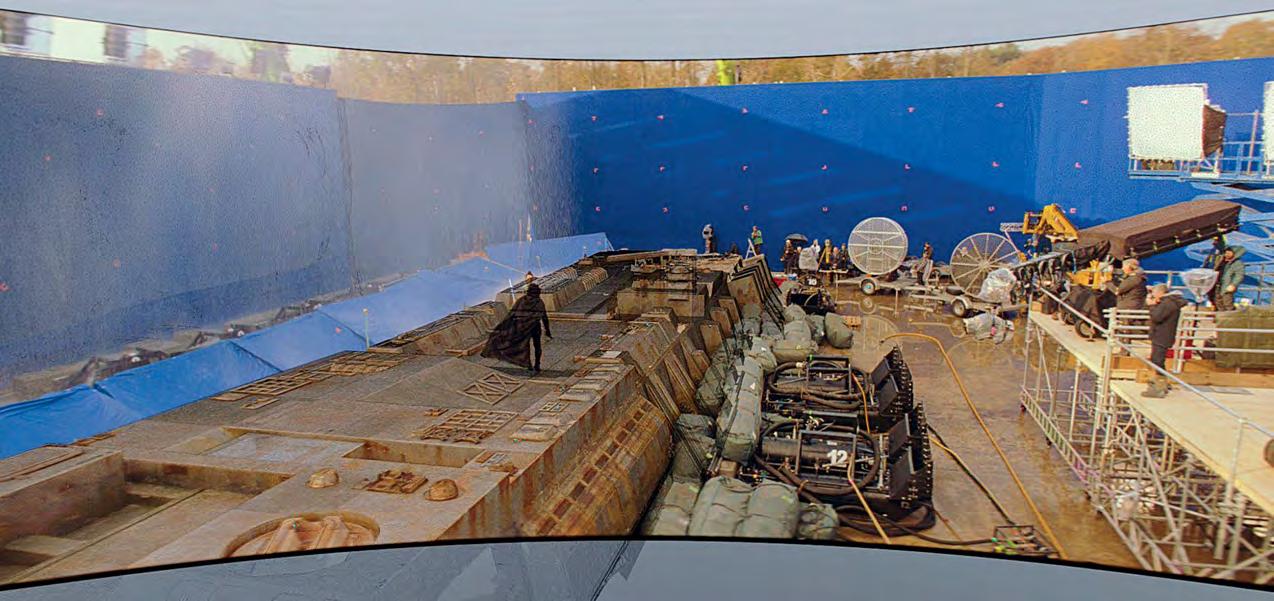

When Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker Visual Effects Supervisor Roger Guyett first sat down with Special Effects Supervisor Dominic Tuohy and director J.J. Abrams to discuss the centerpiece Rey and Kylo Ren lightsaber duel in the film – which happens on a section of the fallen Death Star in the middle of a raging ocean – they all had one common goal in mind.

This was, relates Tuohy, “trying to find something that lets the actors act as if they were in that environment,” with an added goal, says Guyett, of “convincing the audience that there is an integrity to whatever they’re seeing on the screen.”

The idea for the duel then was to supply as much ‘live’ effects interaction as possible during filming, covering the actors in sprays of water to replicate the waves that would be hitting the section they were on. That practical water was down to Tuohy, who won a VFX Academy Award this year for 1917 and has also been Oscar-nominated for two other films. Visual effects artists from Industrial Light & Magic (overseen by Guyett, himself a six-time Oscar nominee) then used that in-camera water as a starting point for their digital simulations.

It was just one of the many times during the making of Rise of Skywalker in which the duo had to closely collaborate, and where they were part of relying upon multiple effects methods for various final shots in the film – others included the dramatic Pasaana desert speeder chase and the moment the heroes sink into black desert sand.

AN OCEAN… IN A PADDOCK

The Death Star lightsaber duel is a demonstration of the power of Rey and Kylo Ren, as well as further insight into their deep

connection. For shooting, which took place on Pinewood Studio’s outdoor paddock lot surrounded by bluescreen in order to acquire the right quality of light, Tuohy’s team designed and built a system of water cannons to generate wave and spray effects, having sold Abrams earlier on the concept by showing the director some similar but smaller previous work and some early tests.

“The cannons would push the water out and vertically up in the air and then it would fall down in a straight line,” Tuohy explains. “We were pumping water nearly 40 or 50 feet up into the air. We had 14 water cannons on one side and eight on the other. They were timed with the amazing stunt choreography of the fight to match its ferocity.”

Originally the filming had been planned for the U.K. summer but had to be moved to late fall, and that meant extremely cold outdoor temperatures. This necessitated not covering the actors in as much water as originally planned. However, occasionally the wind would still get hold of the water spray and drift onto the performers.

“Daisy was there in an outfit with bare arms, and I must admit there were a few times when I heard her shout ‘Dominic!’” shares Tuohy. “The thing is, Daisy would physically flinch when that water hit her – you can see in the footage her tense up when the water is covering her. That’s what makes it feel real, because that’s exactly what you would do.

“Plus, every time a water cannon went off, there was a big roar of air,” continues Tuohy. “That almost always gives the actors something to react to, to remind them of where they are. We had big wind machines running at the same time. So the ambiance of noise that surrounded them is something that really made them feel that they were on the top of this Death Star piece.” “The [water] cannons [for the Death Star lightsaber duel in Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker] would push the water out and vertically up in the air and then it would fall down in a straight line. We were pumping water nearly 40 or 50 feet up into the air. We had 14 water cannons on one side and eight on the other. They were timed with the amazing stunt choreography of the fight to match its ferocity.” —Dominic Tuohy, Special Effects Supervisor

OPPOSITE LEFT: Dominic Tuohy, Special Effects Supervisor, The Rise of Skywalker. (Image courtesy of Dominic Tuohy)

OPPOSITE RIGHT: Roger Guyett, Visual Effects Supervisor, The Rise of Skywalker.

TOP: A view of the practical set at Pinewood Studios, where wave machines provided physical water splashes.

“If we hadn’t shot it the way that we had shot it, I just don’t believe it would have looked anywhere near as convincing. Because they wouldn’t actually be there. Daisy wouldn’t be cold. They wouldn’t be covered in spray. They wouldn’t be wet. A spray or splash is changing the lighting constantly. So all of that interactivity is adding in layers to help convince the audience.” —Roger Guyett, Visual Effects Supervisor

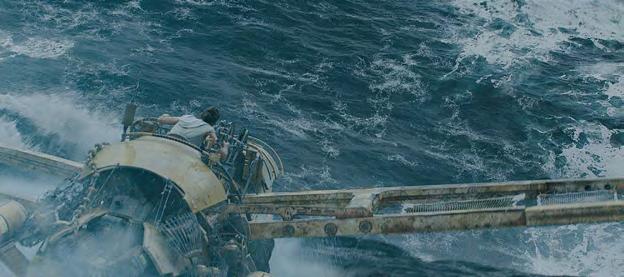

TOP TO BOTTOM: The scene in progress. ILM simulated waves and pieces of geometry to build out the environment.

The live-action actors composited into a wider digital ocean setting.

Kylo Ren and Rey duel on a section of the downed Death Star.

The scene, shot in the U.K. in late fall, was filmed with cold water, adding an extra layer of authenticity to the actor’s reactions when they would be hit with splashes.

TAKING IT FURTHER

“If we hadn’t shot it the way that we had shot it,” suggests Guyett, “I just don’t believe it would have looked anywhere near as convincing. Because they wouldn’t actually be there. Daisy wouldn’t be cold. They wouldn’t be covered in spray. They wouldn’t be wet. A spray or splash is changing the lighting constantly. So all of that interactivity is adding in layers to help convince the audience.”

For ILM, of course, the approach to shooting the sequence meant that VFX artists had an authentic base to start with, even if it did end up replacing much of the spray and generating the undulating ocean.

“A tremendous amount of the work that Dominic did was very atmospheric,” observes Guyett, “in that it wasn’t actually exactly what a wave would do when it hit a surface like that Death Star section. But what it did do was create atmosphere, which was amazing for the actors to imagine that these explosive waves were going off all around them. They didn’t have to imagine that because it was really happening and they really were getting wet.”

Guyett notes that ILM re-wrote its water simulation pipeline as part of the challenging Rise of Skywalker sequence. It allowed artists to lay out and control large blocks of waves to iterate on, and also to treat the water as more of a character in that sequence.

The studio also had to deal with the extraction of the actors and partial set from that bluescreen Pinewood set – always an intricate task – but it’s one, again, that Guyett says benefited from the practical water interaction.

“You’re replacing the dynamics of a real water splash with the dynamics of a digital water splash, but they’re occupying the same kind of area in the screen. The level of realism that all of that adds is well worth the headache in terms of the extraction. I’m just always thinking, ‘What is the best version of this that’s going to end up on the screen?’”

Guyett marvels, in particular, at Tuohy’s efforts in conjuring the wave and spray arch that Kylo Ren emerges from at one point in the duel. “That was almost working in-camera,” he states. Adds Tuohy, “We did that several times to get it right with Adam who just got drenched time after time, and he never complained once.”

SELLING THE REALISM

Although for editorial reasons they did not appear for as long as originally intended in the film, earlier scenes of Rey heading to the downed Death Star on a sea skiff were planned and shot. Again, the moment was imagined as a combination of both practical and digital effects to tell the story of Rey having to struggle across the rough water.

“We thought there should be a skiff on a motion base that allowed us to closely read the movements to see Rey fight and hold onto this ship,” details Tuohy. “We built a hydraulic platform that was computer-controlled in that same outdoor paddock lot environment with smaller water cannons, and the entire skiff. Even one of the outriggers was made to swing completely out over the top while we made it rock and roll.”

ILM was intricately involved in the operation of the skiff gimbal, too, with Animation Supervisor Paul Kavanagh pre-animating specific behaviors on rough water geometry, which would be matched by Tuohy’s operation on set. Overall, the physical structure and the water interaction was aimed at helping to sell [Daisy] Ridley’s performance.

“What you’re trying to do is convince the actor that whatever is happening is actually happening,” attests Guyett. “It’s not just a greenscreen and her sitting on a plank of wood with us saying, ‘Well, you’re on a raging ocean. Just imagine it’s freezing cold and you’re wet and you’re trying to steer this thing to the Death Star.’ We weren’t doing that.

“Instead, Daisy’s actually on a real skiff. The special effects guys could talk to her about pulling the levers or the handles and operating this thing. So now she’s not having to work so hard as an actor because she’s actually on the skiff, and now you’re hitting her with water. So her performance elevates because she’s really on that machine and it’s really moving. She doesn’t have to pretend she’s cold because she’s actually freezing! All of those things I think give this a better sense of realism.”

THE EFFECTS RELATIONSHIP

Both Guyett and Tuohy are at pains to point out their work for Rise of Skywalker was of course carried out in collaboration with scores of other practitioners (the duo ultimately received a visual effects Oscar nomination for the film, alongside Special Creature Effects Supervisor Neal Scanlan and ILM Visual Effects Supervisor Patrick Tubach).

Importantly, they say, no one single effects approach was ever pushed in favor of another during production.

“The trick is getting that balance right,” points out Tuohy. “And when you get that combination of special and visual effects right, you believe it.”

“We’re all pragmatic about what we think we can achieve,” adds Guyett. “It’s about the collaboration and what’s on-screen. It’s not about me just trying to use a piece of technology for its own sake. You’ve always got that shot in mind. And I think that’s what we did for every aspect of the process.”

TOP TO BOTTOM: ILM’s simulation artists had to deal with many different types of water in the scene.

The behavior of the waves often echoes the intensity of the duel.

The skiff navigates the treacherous waves as Rey pilots it toward the Death Star.

A wide shot of the skiff entering the Death Star area.