THE ANGEL WOMAN

SARA BERTRAND+ALEJANDRA ACOSTA

Something like an icy bolt down my spine

Lydia Davis

Something like an icy bolt down my spine

Lydia Davis

In the long summer evenings,

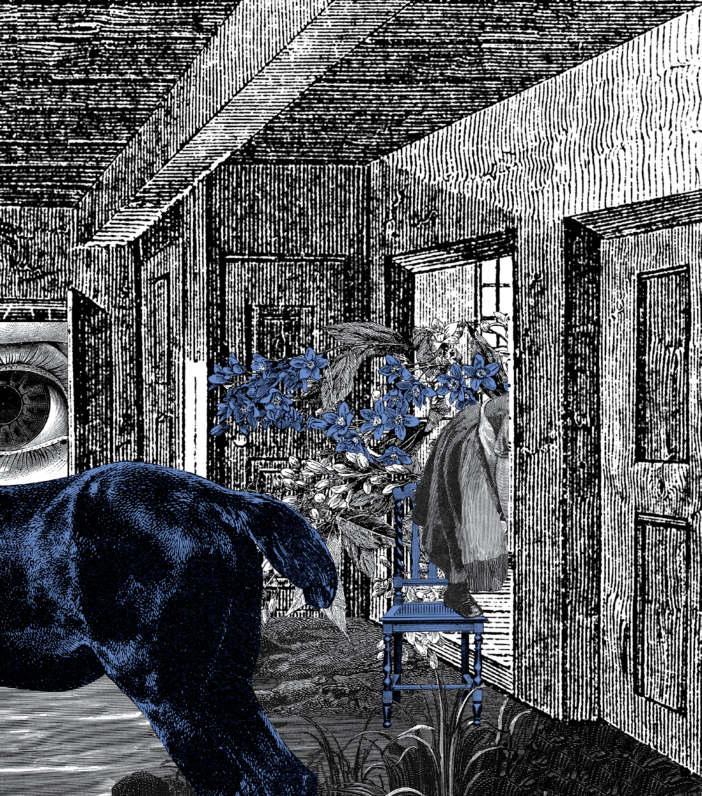

or even in the clear nights of a full moon, you can see the most beautiful woman in the world on top of her blue horse. That's what she told me. After just a few seconds, like a dream inside another, like the sky was cut in half by the breeze, a shooting star passed with its astral tail. And then: the cut out figure over a horse. Calculate that the woman has traveled more than a hundred thousand times the distance from the Kilimanjaro to Patagonia,

but she does not look tired. She is in a hurry, yes. She stops for a moment and she goes like a lightning bolt, maybe to another place that requires the eye she carries on her hand. Which eye? I asked.

—A magical one that sees all—she answered. One eye that does not sleep and points where to go and how fast. On the other hand, she said, she carries a golden bowl. Some think that the bowl has written a song that she repeats like a mantra while she travels from one place to another. But with emotion and surprise, she could not distinguish a thing with the golden glow. She was only 8when she saw her for the first time. Of course they said nothing. She did not even dare to ask for her name. She stayed like this: with her nightgown down her ankles and her bare feet, looking at her like one would look at a ghost. She was surprised by the blue of her horse, her golden tools, her

woven saddle in red, green, white and yellow colors, with pompoms hanging from its belly. Its hooves were almost as golden as its reins, and sharp eyes, almost impertinent. She had forgotten her bike outside her home and she encountered them when she went to gather it. The woman and the horse. Her first impulse, she said, was to scream, are screams even useful? However, the woman, with a calm gesture, put her index finger on her mouth and she exhaled:

—Shhh. She didn't even scream. She opened her mouth, yes, a little bit. An unconscious movement. And then she saw a man lying on the street, above the pavement. The woman leaned daintily. Was he dead? She didn't ask either. And she couldn't tell because she had never seen a dead person in real life. Which means, that when her mother passed away, some of her aunts claimed that she had gone to heaven, others whipped their arms in the air, saying that

she would never come back, and a few others pointed out that her soul will stay forever in the house. But she didn't touch her, neither embraced her or kissed her for the last time, instead she had a glimpse of her inside her coffin through the glass. She asked:

How can she breathe?

Her aunts answered: Don't be silly, go take care of your siblings. So she looked at the man lying on the pavement with the curiosity of those who look at a dead person. Later she said that she noticed a strange quiet from the animal, something that contrasted with the beautiful woman's movements: small and resolute, she stirred her bowl and waved her hands. She said the woman was only a few inches taller than her, who was around 4.3 at the time, and her delicate hands fell over the man

like musical notes and there was a flash in the bowl, like fireworks sparks, although I dare to say she wasn't lying— it looked like the sparks danced until they reached the mouth of the man on the ground. And she stood still, without daring to say anything, with her feet freezing while touching the hard and cold pavement, except for a strange noise, a mix of fear and awe that escaped from her mouth when she saw the man reacting:

Ahhh...

Was she dreaming? It wasn't an ordinary man. He was her father!

The most beautiful woman in the world approached her with small steps, as she was walking over a scaffold. Her fingertips were still shining when she took her cheeks and smiled. That was it. After that she got on her horse and rode away. She couldn't even protest because her father was moaning. Then she ran at his side.

Come on dad she asked affectionately while making a huge effort for her frame, and she managed to make him stand.

Grrmm, grrmm groaned her father, who was arguing against who-knows-who when they reached his bed and he lied down. She looked at him for a while, she said. She looked at her father until he fell asleep again. Only then she remembered that her bike was on the sidewalk, abandoned in the harshness of night, and she came running to pick it up. She left it in the backyard and she closed the door lock. Just like her father taught her: Jacinta lock the door, I'm gonna be late.

She didn't forget that night. It was engraved in her memory, maybe even more deeply in her young girl heart. Who was that mysterious woman? And especially

Who could she ask about it without making a fool of herself? She was afraid of what everyone would think. That her siblings, a set of twins younger than her that always asked her to carry them.

—One at a time— she answered and lifted them up. But the other stayed on the floor complaining: Up! Up! Up! No, definitely not them. So she spoke to Maria. The lady that waited for them when they arrived from school and gave them milk. To her and her brothers. The twins always spilled hot chocolate and they cleaned their mouths with their sweater sleeves. At the end of the day, they had to bathe because of all of the accumulated dirt they carried, but she was the one to do it because private parts shouldn't be shown to anyone, that's what her father taught her.

And can I see my brothers?

—Jacinta, that's different, you are their older sister.

So she put them on the bathtub, she scrubbed them with soap and a piece of towel and later, a lot later, when they were with their pajamas watching cartoons on tv, she bathed. Skinny, small, so different from her brothers. She didn't take long, as she just scrubbed her arms and legs, sometimes even her neck, and when she had time, her hair. So she entered the kitchen ready to find out.

Maria...

Do you know what hour your father said he will arrive today?

He said he was going to be late.

Ha! What a surprise! as he didn't know all the stuff I have to do at home, I told him...

I can take care of my brothers. The conversation was the same every afternoon.

—What a mess! If I didn't have so much to do I wouldn't mind staying to help you.

—Maria...

I gotta hurry.

Maria... she insisted. The woman turned around to look at her.

What?

And she, without letting her escape, told her about the woman she saw on a blue horse with a golden saddle, and also the golden hooves. She said that the woman carried a bowl in one hand and an eye in the other, and that she had saved her father from dying on the street. That's what she told her. Maria, who was plump and big, laughed from her belly. Touching her belly with both hands, up and down, she laughed loudly.

—You said she rode a blue horse?

Yes.

If it was dark, how do you know it was blue? she asked.

Because I saw it.

And the eye? Was it hers or someone else's? It was hers.

—How? Was she missing one? No, she had both of her eyes, and another one in her hand.

—How do you know? Maybe you were confused. No, because she was this far from me and she showed her a part of her palm. Then Maria chewed a carrot. Apparently, the idea of an eye on a hand was shocking, because she was no longer laughing.

Mmmmh, I think it must have been a goblin. Goblins are male.

—How do you know? Because everybody knows. Fairies are female and goblins are male.

—Then, maybe it was a spirit. But her hands were warm while spirits are cold.

Well, miss know-it-all, what do you want me to tell you?

—I just want to know if you know her. No, she had no idea, that's what Maria told her. She didn't know any woman that rode a blue horse and she could even be a crazy woman with long hair and dressed in rags that believed she was miraculous.

Take care Jacinta warned Maria we don't want another tragedy in the family. Unfortunately she was talking about the fact that her mother passed away. It was a difficult topic for everyone. No one told her: I know that your mom died. No one hugged her either. That meant, it wasn't as if when the tragedy happened no one hugged her, everyone got closer to her or the twins and carried them, once, twice, even three times. But later, they seem to forget, and she missed her mother every day.

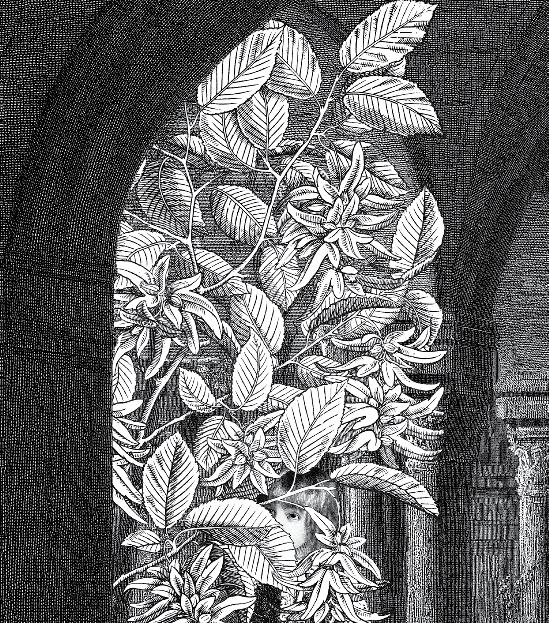

That's why she liked to imagine that if her mother were still alive, she would have known. She liked to think that moms knew everything. Even if her mom was just a memory

of an order: take care of your brothers. That's what she repeated the last time she saw her. It was a little before she met the most beautiful woman in the world. The boy of the house at the end of the block. The largest house in the neighborhood, the one with the high concrete walls. The house next door to hers shared a wall, it had two floors and a garden where it barely fit a pair of potted plants, it looked like a bunker. On the other hand, the boy in the house at the end of the block had a garden where he could get lost playing and trees like the ones that could be seen at the square, besides he had a bike that looked like a motorcycle. And she, who walked with the money her father left her to buy bread, stopped in her tracks before the fence. She thought that inside that house there wasn't a single family member missing, that the kid had only the newest toys, besides that

bike that looked like a motorcycle and who knows which other wonders. She imagined that the garden was hers, that the twins climbed that avocado tree that was on the side to build a secret hangout and that she was the one riding the bike that looked like a motorcycle. She was lost in her thoughts when a voice surprised her:

Hi, I'm Martin. Ashamed, she wanted to run away, but when she turned around she heard:

—Don't go, what's your name? Her father made her promise that she will never give her name to strangers, but the boy of the house, she didn't know why, made her think he wasn't like that.

My name is Jacinta she said without hesitation. Where are you going?

—To buy some bread. Where do you buy bread?

At the store around the corner she told him off Don't you know?

—I'm not allowed to go out alone. Me neither she shrugged. Did you escape?

—No, Maria sent me because she has no time. Is Maria your mom? My mom is dead. Dead? You mean she is in heaven? I don't know. What do you think?

—That heaven is big and it fits a lot of people. That afternoon he invited her to play in the garden, but she had to buy bread so she suggested:

—I can come tomorrow, do you like it? Of course he liked it. And he waited for her around the same time, riding his bike that looked like a motorcycle around.

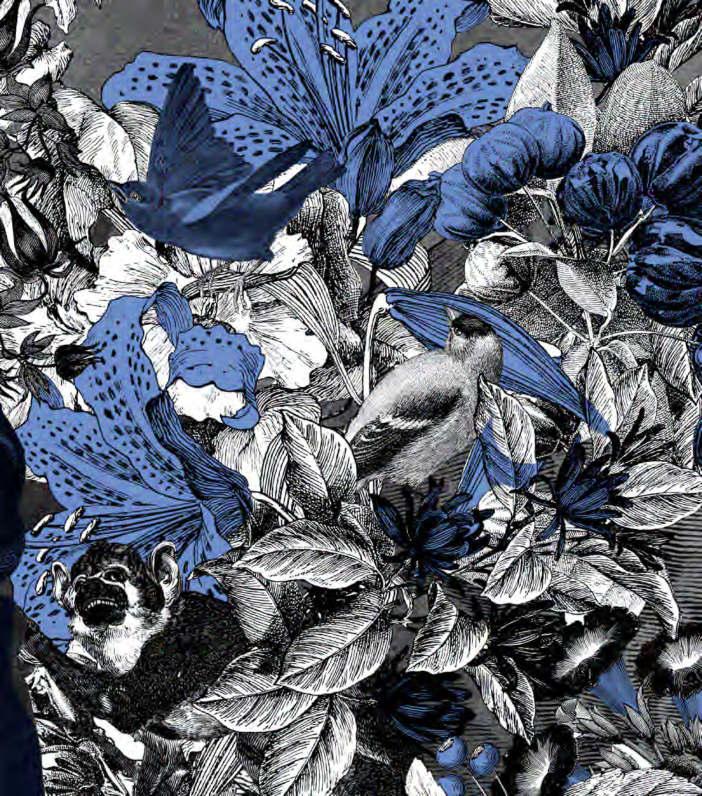

Since she saw the most beautiful woman in the world, she began to dream about her. Dreams of a girl, dreams like an animated short film where the horse appeared full of yarn hanging from its belly and as tame as a dog. In her dreams, she gave it an apple and the horse swished its tail, a mix of its mane and some pompoms, chewing the apple and making noise with its mouth. The woman laughed beside her.

She also dreamed of accompanying her in the evenings, when the sun was setting and Maria grumbled:

Ouch! It's late, what time did your father say he will come home?

Then she dreamed about her. The woman was around 4.3 of height, with sweet gaze and fingers like musical notes, singing a long and melodic song, a song that made her fall asleep and cooed the twins, without having to tell them a story. Because her father was late and Maria left them alone. Every day.

Sara Bertrand lives and works in Santiago, Chile. She studied history and journalism at Universidad Católica de Chile, where she teaches "Aesthetic Appreciation of Children 's Books". She has work on newspapers, magazines and radio. She won the literary creation scholarship from National Council of Culture and the Arts with Cuentos inoxidables and the scholarship from Fundación Nuevo Periodismo

Iberoamericano with "Los acordes del mandinga". Besides, she won the Alimón de Tragaluz Editores contest, along with Francisco Montaña with Nuestro gordo. She has published in France, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Mexico, Venezuela and Spain. Her novel Ejercicio de supervivencia was translated into french.

Alejandra Acosta is an editorial designer and an illustrator. She lives and works in Santiago, Chile. Besides working as an author, she teaches illustration at Universidad del Desarrollo and Universidad del Pacífico, and she teaches the certificate course of Management and Production of Illustrated Publications at Pontificia Universidad Católica. She won the Colibrí medal from IBBY Chile in the illustration category with Aventuras y orígenes de los pájaros (2012), El Árbol (2013) y Pajarario (2015). She has been a finalist in the illustrated album category at international contests from the Kalandraka and Nostra editorial and the Fondo de Cultura Económica.