MAKE YOURSELF AT HOME Design that nurtures conviviality and calm ISSUE 149 $13.95

Australian Residential Architecture and Design

A PROUD HISTORY OF QUALITY AND CUSTOM FABRICATION

For nearly 40 years, innovation and quality have been our driving passions. Rylock design and manufacture a range of high performance product solutions. AUSTRALIAN MADE AND OWNED.

Scan QR for project photos and article

Scan QR for project photos and article

rylock.com.au

Designed by Contech Architects Built by NRG Building Photograph by David Sievers

Designed by Contech Architects Built by NRG Building Photograph by David Sievers

For Ellul Architecture, designing Sandringham House required a compact plan with big ambitions. Beyond just looks alone, it had to feel like a dream modern home with maximum internal space for a young family to grow. The design sensibilities of Axon™ Cladding by James Hardie brought drama and detail without the durability worries of timber.

JAHAOS0095_Sand_HDL © 2022 James Hardie Australia Pty Ltd ABN 12 084 635 558. ™ and ® denote a trademark or registered mark owned by James Hardie Technology Ltd.

A home so perfectly executed, it runs rings around its timber counterparts.

Axon™ Cladding

Sandringham House by Ellul Architecture

Find your inspiration at

From the Editor 08

Musings

Contributors 10

Fresh finds 13 Products

Green scene 49

Sustainable products

New products that support an ethical and environmental agenda.

Bookshelf 53 Reading

Local design is championed in these new publications, which delve into residential design in Aotearoa New Zealand, Tasmania, Sydney and bayside Beaumaris.

Portrait of a House 130 Postscript

Louise Whelan’s photography and film project documents the craft, care and collaboration that underpins Peter Stutchbury’s Indian Heads House.

House for BEES Working with an Architect

42

44

80

Homeowner Sarah approached architecture firm Downie North with a brief for a sustainable and practical family home.

Foomann Architects One to Watch

This studio untangles constraints to yield quiet, environmentally responsive and thoughtfully detailed work.

Elliat Rich Studio

Often mythical, the work of this Alice Springs-based designer seeks to spark connection between all things.

82

Chinaman’s Beach House by Fox Johnston

First House

Conrad Johnston recalls his studio’s first residential commission, built on a precipitous Sydney site.

Steendijk In Profile

111

122

For two decades, this Brisbane studio has been crafting inventive, well-detailed houses underpinned by a passion for making.

Marie Short House by Glenn Murcutt

Revisited

This seminal work, designed by Glenn Murcutt and built in 1974, endures as a model for responsive, responsible design.

05 AT A GLANCE HOUSES 149

At a Glance

Adaptable and intuitive, these houses are attuned to evolving use, accommodating the ebb and flow of visitors and responding effectively and delightfully to seasonal change.

Bass Coast Farmhouse by John Wardle Architects

16

26

Hopscotch House by John Ellway Architect

House for BEES by Downie North

New House Wonthaggi, Vic 54

Elsternwick Penthouse by Office Alex Nicholls

34

Alteration + Addition Sydney, NSW

62

Caringal Flat by Ellul Architecture

Apartment Melbourne, Vic 94

86

House in the Dry by MRTN Architects

New House Tamworth, NSW

Apartment Melbourne, Vic

Bedford by Milieu by DKO with Design Office

Apartment Melbourne, Vic

70

Alteration + Addition Brisbane, Qld 102

AB House by Office Mi–Ji

New House Barwon Heads, Vic

Grove House by Clayton Orszaczky

Alteration + Addition Sydney, NSW

CONTENTS 06

Musings

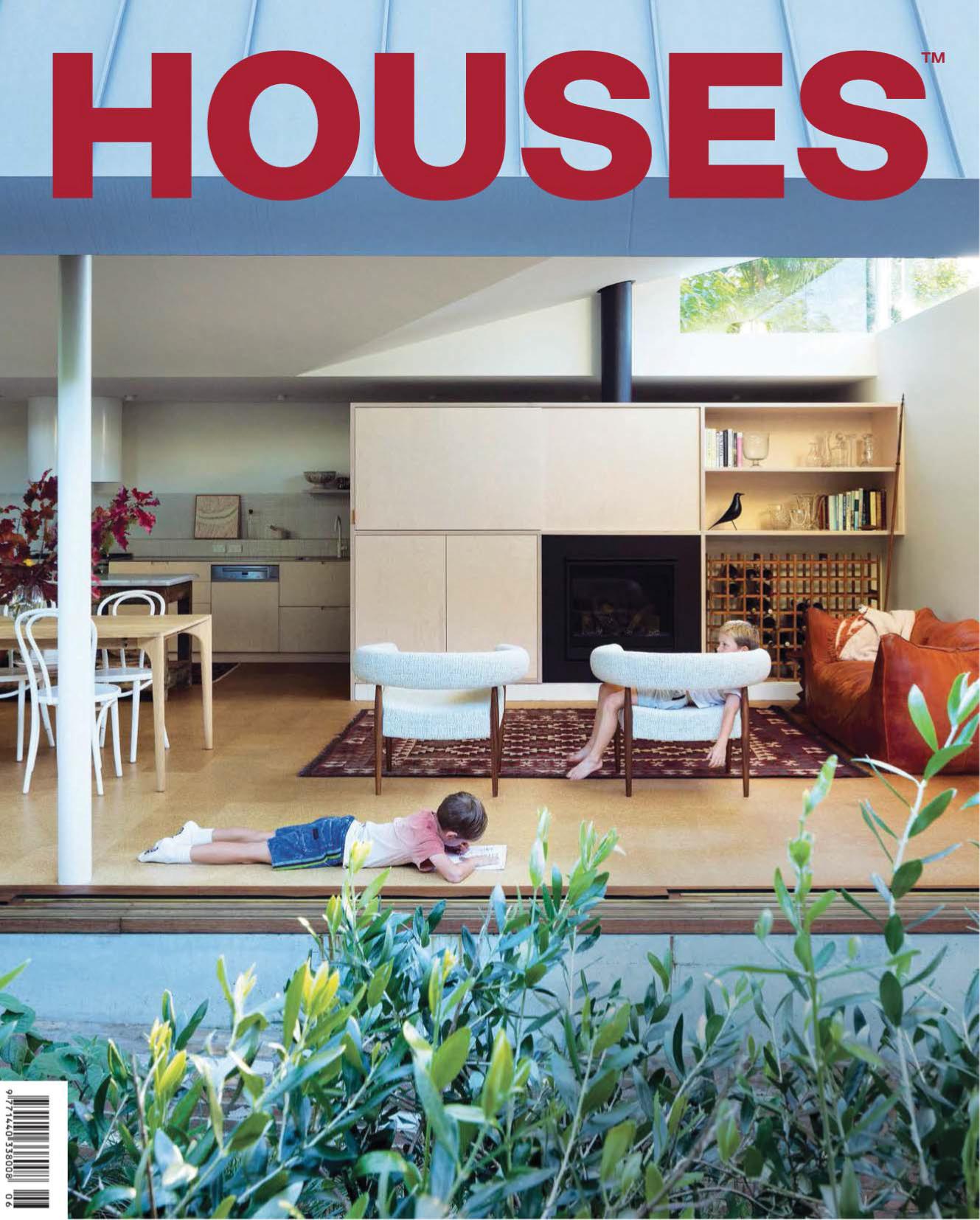

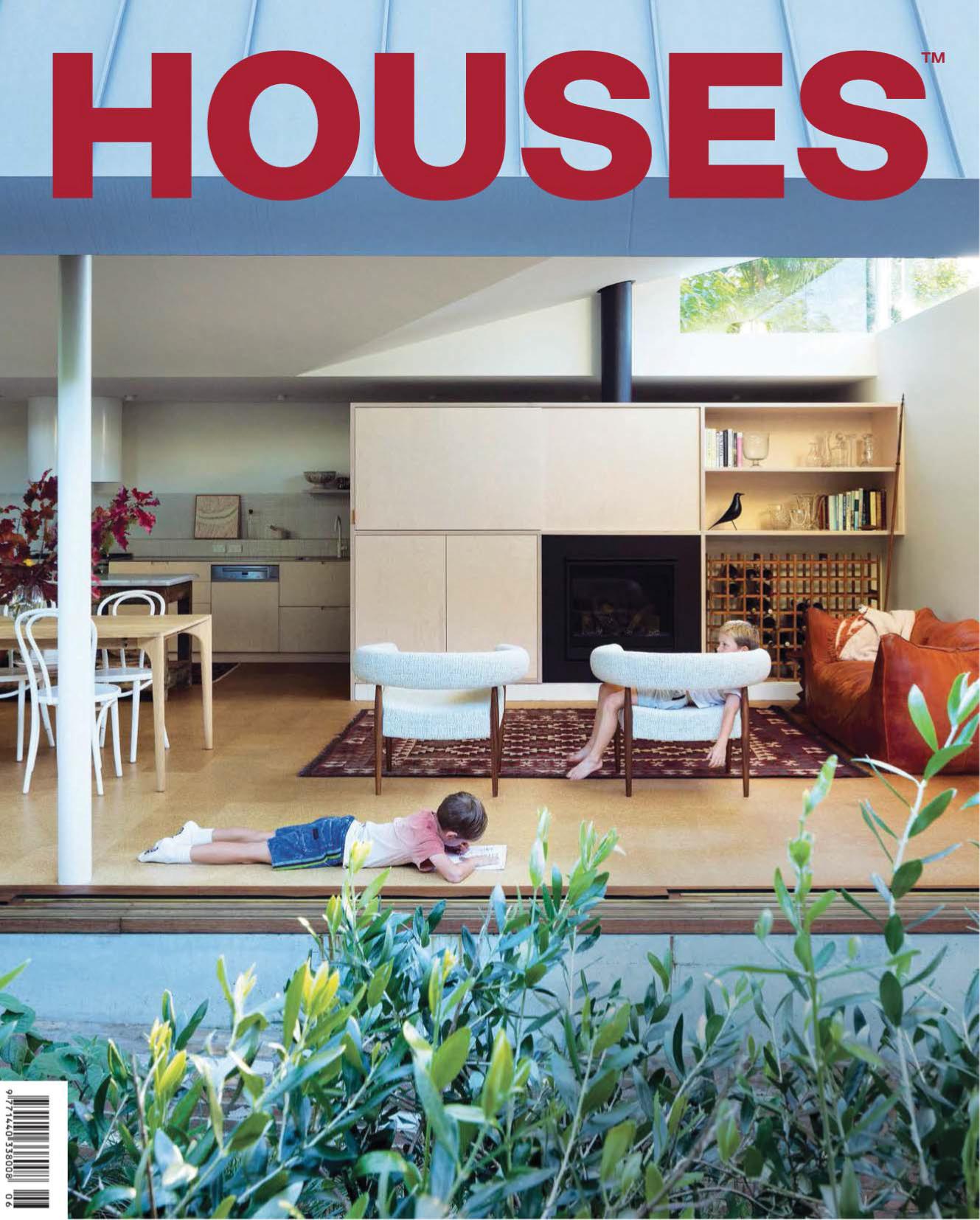

As summer begins and the end of the year approaches, many of you might be awaiting a change in pace and eager to assume a recumbent pose, like our cover stars. Flux is a recurrent thread in this issue of Houses, with homes that encourage their owners to delight in seasonal change, and the ebb and flow of friends and family. Office Mi–Ji’s AB House in Barwon Heads (page 94) employs layered rooms and twists in the plan to create an intriguing beach house that oscillates between privacy and connection. In Brisbane, John Ellway Architect’s Hopscotch House (page 26) registers daily and seasonal change like a sundial, spurring its occupants to move around the house depending on fluctuations in sun, breezes and seasons. The end result is, Dirk Yates writes, like choosing where to place a picnic rug, but in a house. Reflecting the different ways we choose to live in Australia, in this issue we also visit three apartments: a fastidiously reworked 1950s studio that revives the original architect’s vision for sociability in small-footprint living (Ellul Architecture, page 62); a new development that offers a customizable floor plan in anticipation of a diverse internal life (DKO with Design Office, page 70); and a multigenerational apartment that meets its owners current needs while anticipating future change (Office Alex Nicholls, page 54).

Put your feet up, find a comfy spot and enjoy reading this issue of Houses.

Alexa Kempton, editor

Write to us at houses@archmedia.com.au

Subscribe

Print: architecturemedia.com Newsletter: architectureau.com/ newsletters_list Find us @housesmagazine

01 Discover domestic life in rural South Australia through a photographic exhibition of two farmhouses at the State Library of South Australia. This photographic series by Alexandra McOrist offers glimpses into the histories of two now-empty farmhouses, formerly occupied by settler families. McOrist weaves details of archival magazines and newspaper articles into each photo, adding historical context but ultimately leaving the narrative up to the viewer’s imagination. Until 29 January 2023. Image: The best of times, the worst of times. Photograph: Alexandra McOrist. slsa.sa.gov.au

03 Celebrate the legacy of the anonymous maker in this ceramics exhibition. Artist Kristin Burgham moulds ceramic forms from discarded objects such as bottles and boxes, acknowledging the anonymous makers whose objects populate our homes. Legacy will be on show at Craft Victoria’s Vitrine Gallery from 31 January to 4 March 2023. Image: courtesy of the artist. craft.org.au

02 Explore a collection of architectural homes in Sydney’s picturesque suburb of Castlecrag. Led by local architect Ben Gerstel, the walking tour takes you down the streets of this historic garden suburb, which is scattered with architectural homes designed by Harry Seidler, Peter Muller, Hugh Buhrich and more. Tour runs 10 December. architecture.org.au/tours

04 Immerse yourself in modernist sculpture at the first Australian exhibition of the work of Barbara Hepworth. Developed in consultation with the Hepworth Estate, the exhibition charts the shift in Hepworth’s approach from figurative to abstract forms. See Barbara Hepworth: In Equilibrium at Melbourne’s Heide Museum of Modern Art from 5 November 2022 to 13 March 2023. Image: Sculpture with Colour and String, 1939, 1961, by Barbara Hepworth. courtesy of Heide Museum of Modern Art. heide.com.au

MUSINGS 08

01 03 04

Materially Different

Timber veneers to bring dimension to any space

Joinery & Walls Eveneer Almond by Elton Group Project Leichhardt House Interiors Porebski Architects Photographer Tom Ferguson

Contributors

Anthony’s work explores the quieter, experiential moments found in buildings. He is drawn to architecture that stirs emotion through scale, form, colour and texture. Anthony has developed a portfolio of projects that are not clean nor simple, but rather emotive, personal, layered and considered.

Chloe cut her teeth practising architecture in her North Queensland home town of Bowen. She has since lived and practised architecture in Brisbane and Lima, Peru. She is now based in Sydney, where she works for BVN across multiple typologies in both architecture and interiors.

Editor Alexa Kempton

Editorial enquiries Alexa Kempton T: +61 3 8699 1000 houses@archmedia.com.au

Editorial director Katelin Butler Editorial team Georgia Birks Nicci Dodanwela Jude Ellison Cassie Hansen Josh Harris Production Goran Rupena Design Janine Wurfel janine@studiometrik.com

Advertising enquiries All states advertising@ archmedia.com.au +61 3 8699 1000

Print management DAI Print Distribution Australia: Are Direct (newsagents) and International: Eight Point Distribution

CEO/Publisher

Jacinta Reedy Company secretary Ian Close General manager operations Jane Wheeler General manager digital publishing Mark Scruby General manager sales

Michael Pollard

Published by Architecture Media Pty Ltd

ACN 008 626 686

Level 6, 163 Eastern Road South Melbourne Vic 3205 Australia T: +61 3 8699 1000 F: +61 3 9696 2617 publisher@archmedia.com.au architecturemedia.com

Endorsed by The Australian Institute of Architects and the Design Institute of Australia.

Sheona Thomson Writer

Sheona is a Brisbane-based design educator and course coordinator in the School of Architecture and Built Environment at QUT. A regular contributor to Architecture Media titles, she values the opportunity to report on local designers’ inspiring work.

Anthony St John Parsons Writer

Anthony is an Australian architect who runs his own practice in Wangal Country, Sydney. His modest body of work has been repeatedly recognized by the Australian Institute of Architects.

Anthony is a frequent critic and guest tutor at the universities of Newcastle and New South Wales.

Cover: House for BEES by Downie North. Artwork: Margie Carew-Reid. Photograph: Clinton Weaver.

Member

Circulations Audit Board

Subscriptions architecturemedia.com/store subscribe@archmedia.com.au or contact the publisher above

ISSN 1440-3382

Copyright: HOUSES™ is a trademark of Architecture Media Pty Ltd. All designs and plans in this publication are copyright and are the property of the architects and designers concerned.

CONTRIBUTORS 10

Anthony Basheer Photographer

Chloe Naughton Writer

Fresh finds

From tactile cast metal handles to design classics in contemporary colourways, these new products will add a distinctive finishing touch to your home.

Find more residential products: selector.com and productnews.com.au

01 Dip Wall Hook

Crafted through slip casting, the Dip Wall Hook delights in the texture and natural colour variation achieved in the glazing process. Designed by Ashlee Hopkins and Thomas Parbs, the hooks feature a soft, concave form and fine edges. Available in six colours. j-a-m.com.au

04 Herman Miller x Hay

The Herman Miller x Hay collection comprises twenty-first century reinterpretations of eight mid-century Eames classics. Featuring considered new colour palettes and updated materials, this collection combines timeless design with a contemporary point of view. hermanmiller.com

02

Wästberg x John Pawson

Celebrated architect John Pawson’s first Wästberg lamp combines rectilinear and curved elements in one quietly monumental volume. Notched cut-outs contribute to the lamp’s distinctive profile and shape the way light is cast from the dimmable light. wastberg.com

05 Casts by Edition Office for Bankston Designed by architecture practice Edition Office, this limited edition collection of cast metal door hardware celebrates subtle, refined character and intuitive functionality. Elegant, minimal forms invite touch and, thanks to thoughtful design, are a joy to operate. bankstonarchitectural.com.au

03 Dulux connect Dulux’s Colour Forecast 2023 comprises three palettes that reflect our desire to bond with the people and places we love. The Connect palette gathers warm, earthy colours: think moss, wasabi and burnt charcoal. Styling by Bree Leech, photograph by Lisa Cohen. dulux.com.au

HOUSES 149 13 FRESH FINDS

01 03 05

04

02

06

Sundowner

by Jørn Utzon for Lyfa

Lyfa has relaunched Sundowner, an iconic pendant light first designed in 1948 by Jørn Utzon. A special edition has been added to the range, featuring a sandstone-inspired colour on two of the four shades that pays homage to Utzon’s house by the Mediterranean sea. fredinternational.com.au

09 Urania collection

A collaboration between Hegi Design House and New York- and Florence-based architect Pietro Franceschini, Urania features expressive sculptural forms. The eight furniture pieces are upholstered in velvet and boucle, yet their bulbous forms look as if they were cast in stone. hegidesignhouse.com

07 Coppibartali

Designed by Mario Nanni, the Coppibartali light comprises distinctive glass cylinders that allow the design to function as a wall, table and pendant light. The aluminum detailing –a patented Viabizzuno chain system – ensures the light is as elegant as it is versatile. viabizzuno.com

10 Surround by Laminex

Five new profiles have been added to the Surround by Laminex range, including a profile inspired by the Breton shirt, a classic staple in French fashion. All Surround panels are now certified as moisture resistant, making them suitable for laundries and bathrooms. laminex.com.au

08 Occhi Maxi wall sconce

Part of the Occhi collection, the Maxi wall sconce explores bold contrast through its pairing of circular and linear forms. A solid cast glass disc sits against a discreet backplate, creating a halo-like glow, while the gently tumbled satin frost face subtly refracts light. articololighting.com

14PRODUCTS

06 09 10 0708

Caesarstone Porcelain. A new point of view.

Since 1987, Caesarstone has inspired design freedom in millions of homes worldwide. Now, we’re introducing new porcelain surfaces that expand our portfolio of premium colours, leveraging our legacy of craftsmanship and

innovation to give you even greater flexibility, indoors and outdoors.

Caesarstone Porcelain marks a leap in technology, functionality, and design with surfaces that deliver a new degree of durability, strength, and beauty in the heart of your home.

513 Striata™ caesarstone.com.au

BASS COAST FARMHOUSE

BY JOHN WARDLE ARCHITECTS

16

HOUSES 149 17 01

Words by Rachel Hurst Photography by Trevor Mein

When Gertrude Stein wrote “A rose is a rose is a rose,” it wasn’t because she’d mislaid her thesaurus. Stein’s work explored the conceptual power of poetry, and her message was that the name of a thing immediately summons the symbols and emotions we associate with it. If this review simply said “a house is a house is a house,” readers (and editors!) might feel a little cheated, but it would go to the heart of this conceptually rigorous work in regional Victoria by John Wardle Architects (JWA). With its instantly recognizable silhouette of wall-roof-chimney, Bass Coast Farmhouse is almost a cartoon of our collective image of “house.” But it joins a lineage of iconic houses that approach the Platonic ideal: from the classical typologies of Roman courtyard villas and Palladian palazzi, to more recent models such as Herzog and de Meuron’s House in Leymen (1997) and Glenn Murcutt et al’s evocations of Australian farm buildings.

In contrast to JWA’s normal additive design process, this house is exactly as it was proposed to be – from concept to detailed execution. The design is about the power of reduction and responds to another lineage: this is the clients’ third residential commission for the practice. The previous two, Fairhaven House (2012) and Freshwater Place Apartment (2016; see Houses 119), were designed to embrace panoramic views. Instead, Bass Coast Farmhouse turns inwards as a hollow square, almost perversely denying long landscape views in favour of a farmyard court complex. There is good sense to this tactic: it’s stark country. Close to a rocky shoreline, it’s a perfect retreat for the surfing client and family. Entirely off-grid with extensive solar and water collection, this is a place to hunker down and relish self-containment.

01 The farmhouse’s external form remains faithful to the building language of rural structures.

02 A courtyard plan provides enclosure and protection on an exposed coastal site.

BASS COAST FARMHOUSE 18

Composed and confident , this new residence in regional Victoria distils the fundamentals of the rural farmhouse into a richly detailed home that encourages its occupants to relish slowness and self-containment.

HOUSES 149NEW HOUSE 19 1 6 2 2 22 7 3 8 4 9 5 Ground floor 1:400 11 12 13 14 10 Lower floor 1:400 05 m 1 Main bedroom 2 Bedroom 3 Lounge 4 Kitchen 5 Dining 6 Living 7 External bridge 8 Courtyard 9 Void below 10 Cellar and storage 11 Laundry 12 Outdoor kitchen 13 Outdoor terrace 14 Water feature 02

4–14 5

Wonthaggi, Vic Site 660,975 m² Floor 374.5 m² Design 10 m Build 24 m Extended

Five rules govern the design, buttressing its ethos of empathy with this austere environment: constant enclosure; a single concrete floor; an undercroft defined by the rise and fall of the land; three types of windows; it is a farmhouse, pure and simple.

The plan is guided by the rules of enclosure and the fundamentals of the farmhouse (for example, orientation on the diagonal compass points, a kitchen overlooking the entry, double entry porches and no embedded garage). But the “ground rules” generate volumetric drama. Influenced by the work of architects Lina Bo Bardi and Paulo Mendes da Rocha in Sao Paolo, JWA has built down, not up, using the undercroft as a potent circulation experience. The floor plate follows the slope of natural ground level: while the house sits on terra firma on most of its four sides, the courtyard plunges toward an underbelly that “leaks out” below a double cantilever toward the ocean. Two stairs connect back to the main level. If that all sounds complicated (as it would have been to build), the result feels entirely resolved and thrilling in the experience.

The rules of reductionism and repetition discipline the building formally and economically. Extraneous elements like gutters are detailed into apparent oblivion, materials restricted to a tight palette of concrete, spotted gum and galvanized roofing; and “a window is a window is a window.” The result is a mute (but familiar) form in the landscape that opens to reveal a highly articulated interior.

Bass Coast Farmhouse is undeniably generous in scale, but intelligent handling controls its functionality around the courtyard. Embracing the symmetry of the square, the design clusters sleeping and living into wings that can be closed or opened to the inner or outer light as required. The contrast of dark, dappled or illuminated corridors makes a virtue of the longer journeys. A bridge allows the clients to cut between the living area and main bedroom and enjoy the spatial drama of the inside-outside void. There’s a wicked confusion of design references in the detailing – are we in an elevated sheep run or Scarpa’s Castelvecchio? – and a teasing visual proximity of main bathroom to lounge. It’s the one moment when the gabled roof is broken to flood the void with sunlight, and a large window alcove invites contemplation of this cultivated abyss.

Slowness is deliberately built into this house. Just opening it from its dormant state takes meditative (and physical!) effort. The shutters are operated by bespoke steampunkesque handwheels that mechanically generate electricity to open them: the slow exposé awakens the house and self to place. The living room is subtly attuned to temporal rhythms, seasonal and historic: fifteen metres long, with different furniture settings for a winter hearth or summer lounging space, it’s a latter-day Elizabethan Long Gallery. The house is an evolved vocabulary of design gestures: timber linings and joinery that blur into architectural intarsia; surprise practical wet areas; draped steel shelves and seamless cupboards. As ever in Wardle’s work, there’s a delight in the kinetics of daily life –from animating the exterior envelope, to the theatrical descent of a concealed television or the neat tuck of concertina flyscreens. Is God, or the Devil, in the detail? Certainly the practice is committed to this kind of dazzling resolution and has courted the best in the construction industry to achieve it.

Awaiting occupation by its owners, the farmhouse feels expectant, immaculate and archetypal, even as it begins to gently weather into its setting. This house sits confidently between past and future heritages in residential design. In John Wardle’s assessment, it is perhaps the acme of the practice’s domestic work. With such purity of concept and execution, it belongs in the lexicon of Australian architecture. But without doubt this memorable project demonstrates the essence of “house,” and that a paradigm is a paradigm is a paradigm …

03 Screens and shutters are moved by handwheels, turning their operation into theatre. Artwork: Timothy Cook.

04 A refined but restrained interior is wrapped in timber.

BASS COAST FARMHOUSE 20

3

New house

family (holiday house) + 1 powder room

Bass Coast Farmhouse is built on the land of the Boon Wurrung people of the Kulin nation.

HOUSES 149NEW HOUSE21 03 04

Five rules govern the design, buttressing its ethos of empathy with this austere environment: constant enclosure; a single concrete floor; an undercroft defined by the rise and fall of the land; three types of windows; it is a farmhouse, pure and simple.

BASS COAST FARMHOUSE 22

05

Section 1:400 05 m

07

05 The house is sited on a natural rise, creating a bunker-like undercroft.

06 A cutaway in the roof adds to the spatial drama of the undercroft.

07 A bridge across the void is a thrilling shortcut from the main bedroom to the living spaces.

HOUSES 149NEW HOUSE 23

06

Products

Roofing: Lysaght Custom Orb

External walls: Spotted gum tongue-and-groove cladding from Matthews Timber in WOCA exterior oil; concrete by Insitu in Class 2 off-form finish

Internal walls: Spotted gum timber veneers from Timberwood Panels in Osmo Polyx matt; plasterboard in Dulux ‘White Duck Quarter’; Inax Fuka and Yohen Border tiles from Artedomus

Windows: Custom solid spotted gum with fixed Viridian Energytech clear glazing by Overend Constructions and Pickering Joinery; Aneeta black anodized aluminium sashless windows with Viridian Lightbridge clear glazing; custom solid spotted gum timber shutters by Overend Constructions

Doors: Custom spotted gum timber (solid and veneer) by Overend Constructions

Flooring: Machine-burnished concrete topping screed slab; solid spotted gum tongue and groove from Matthews Timber; coir matting by Birrus Matting Systems

Lighting: Produzione Privata Aquatinta and IPY from Ornare; Lampada from Artedomus; various from Light Project Kitchen: Blanco Claron sink; Sussex mixer; Fisher and Paykel fridge/freezer and dishwasher; Condair rangehood; Lacanche oven and cooktop; custom shelves and concrete island by Overend Constructions; custom steel benchtop by Sharpline Bathroom: Sussex tapware; Concrete Nation bath; Agape wall basin; Set in Steel monolithic concrete vanity; Sepp concrete basin from Wood Melbourne; Overend Constructions basin frame and steel rod towel rail

Heating and cooling: and Sanden Eco Plus hot water system; Daikin bulkhead split system from Griepink and Ward; Cheminees Philippe fire box from Wignells; in-slab heating by Nissle Eichert Heating

External elements: Overend Constructions custom steel and concrete features; The Pool Company custom pool with Sunbather automatic cover

Other: Bespoke timber elements by Overend Constructions and Charles Sandford Woodturning and Joinery; custom cushions by Martel Upholstery

BASS COAST FARMHOUSE 24

08 09

08 The main bedroom at the western corner of the house enjoys panoramic views of the landscape.

09 Bunkrooms accommodate extended family.

10 A generous entry is equipped for the removal of muddy shoes and coats.

Architect John Wardle Architects +61 3 8662 0400 enquiries@johnwardlearchitects.com johnwardlearchitects.com

Project team John Wardle, Diego Bekinschtein, Megan Fraser, Andy Wong, Luca Vezzosi, Adrian Bonaventura, Maya Borjesson Builder Overend Constructions Engineer OPS Engineers Landscaping Jo Henry Landscape Desigin Sustainability consultant Greensphere Mechanical services Griepink and Ward Electrical services and solar PV system Burra Electrical Geotechnical and bushfire consultant Ark Angel

HOUSES 149NEW HOUSE 25

10

HOPSCOTCH HOUSE

BY JOHN ELLWAY ARCHITECT

26

HOUSES 149 27 01

Words by Dirk Yates Photography by Toby Scott

John Ellway has a knack for naming things. The shorthand name for his practice, JEllway, offers a practical and playful nickname that brands the architect and the practice, and is easily transferrable to hashtags. This style of nomenclature – perhaps a conceptual residue from John’s time working in wayfinding and product communication before he became an architect – also extends to the labelling of projects. In the practice, there is no Indooroopilly House, Schulz Extension, or XX House – names fit for an office filing system with the sensibility of the White Pages. Instead, we get Terrarium House, Cascade House, Three House and Twin Houses – titles that evoke the design qualities that are particular to each project rather than the client’s driver’s license or the architect’s oeuvre.

So, we come to Hopscotch House, a name that conjures ideas of squares and numbers chalked on concrete, and giggling children hopping and twisting as they follow the arbitrary rules of the game. Looking at the plan of the house, you can see how the skip-hop of hopscotch has been instilled in built form: the arrangement of rooms and courtyards, which

extend from the existing timber worker’s cottage, is reminiscent of the children’s game, while also elucidating design principles that the architect has set for the project.

An unconventional design response can elicit a playful interaction between architect and client that is not dissimilar to children negotiating the rules of a new game. There is often a mix of earnestness and absurdity in this relationship that allows for revelry over the banal. One such project that comes to mind is House VI (1975) by US architect Peter Eisenman, in which the design concept, based on the interaction of voids and solids, necessitated that a non-structural column be inserted in the middle of the dining table without connecting to the floor. This provocative design, which intentionally ignored the specific requirements of the client or even the need to provide salubrious accommodation, is nevertheless playful in the ways it challenges those who live there. In both Hopscotch House and House VI, enjoyment can be found in perceiving and experiencing the spatial narrative negotiated by the architect with the owners.

01 Sliding, stacking doors and casement panels allow the house to be open to light and breezes.

02 New rooms are designed as garden pavilions that are pulled apart to enfold several courtyards.

HOPSCOTCH HOUSE 28

Inspired by the simple joy of a children’s game, this home’s stepped composition of rooms and garden courtyards creates an intuitive, flexible home that is readily connected to the outdoors.

HOUSES 149ALTERATION + ADDITION 29 Floor plan 1:400 05 m 1 Neighbourhood garden 2 Bikes 3 Parking 4 Open verandah 5 Bedroom 6 Hall 7 Laundry 8 Entry 9 Entry garden 10 Western garden 11 Dining 12 Kitchen 13 Secure garden 14 Driveway 15 Lounge 16 Kitchen garden 17 Grass 18 Carport 19 Shed 1 6 11 16 2 7 12 17 3 8 13 18 19 4 9 14 5 5 5 10 15 5 02

people.

Alteration + addition Brisbane, Qld

Site 405 m²

Per m² $4,900 Family

Unlike House IV, however, the principles of Hopscotch House are primarily social and environmental. Light and air flow freely and are easily modulated by the building (with sliding screens and opaque windows), the landscape (a vine grown across a gabled trellis for shade, and the shedding of leaves of a deciduous tree to admit winter sun), or the way the house is occupied (occupants moving along the couch to where the sunlight is or isn’t). There is a dynamism to the house that is compelling and delightful. The homeowners will want to spend more time in particular rooms depending on the time of year, and to move to certain areas of a room depending on the time of day. It’s all simple stuff and it relies on the owners embracing the changeable qualities of the sun, the breezes and the seasons. It feels a lot like choosing where to place your blanket for a picnic, but in a house. There is an old-fashioned quality in this house. It’s not the technological equivalent of the Gameboy; there is no PassivHaus certification or triple-glazed windows. It doesn’t need to be. This is subtropical design at its best: intuitive, flexible and readily connected to the outdoors. The house simply responds to Brisbane’s predominantly benign climate by controlling breezes, employing concrete floors for coolth, and drawing in winter daylight to warm interiors. There are solar panels and rainwater collection but, like the flushing toilet, they don’t get a special mention – they’re simply necessities. The

Floor 120 m² Carport/shed 28 m² Design 22 m Build 11 m

materials are modest – being primarily timber, corrugated metal sheet, brick and rendered concrete blocks – and are therefore relatively consistent with the existing building. The kit of doors and windows that repeats throughout the extension has an economy of construction comparable to the Queenslander vernacular that is pragmatic and economical rather than kitsch.

A unique aspect of the design is that, although the existing cottage is double-fronted, the new work is only one room deep. Rather than being one long, thin, north–south extrusion, the new rooms step from east to west and enfold several courtyards, each with distinctive plantings and uses depending on their solar orientation. There is a lush entry garden, a Mediterranean terrace adjacent the dining table, a greenhouse fernery, and a service court for propagating new plants and making your way to the shed. Consequently, the extension functions as a series of garden pavilions rather than a set of partitioned rooms in a house. While being relatively unique in plan, the design expresses fundamentals of architecture that are not new. Instead, it is a revival of sensibilities that were common before the intensive use of energy through heating and airconditioning. The design of Hopscotch House is driven by a simple shift in the way we understand housing, emphasizing not the rudiments of accommodation but rather the enjoyment of occupation. It’s as simple as child’s play. Delightful!

HOPSCOTCH HOUSE 30

2

44

Hopscotch House is built on the land of the Turrbal and Yuggera

There is a dynamism to the house that is compelling and delightful.

The homeowners will want to spend more time in particular rooms depending on the time of year, and to move to certain areas of a room depending on the time of day.

03 The house registers sunlight’s daily and seasonal movements.

04 Deciding whether to sit in the sun or the shade is like choosing where to place a picnic blanket, but in a house.

HOUSES 149ALTERATION + ADDITION 31

03 04

05 Mesh screens will support vines as they grow up and around the addition.

06 A new entry leads directly into the living spaces, preserving privacy for bedrooms.

07 A neighbourhood garden at the front of the house offers greenery to the street.

05 06

HOPSCOTCH HOUSE 32

Roofing: Corrugated Custom Orb by Lysaght in ‘Natural Zincalume’; clear toughened glass by Viridian

External walls: Handimesh by Earlybird Steel; fibre cement sheet by James Hardie; existing timber cladding in Dulux ‘Natural White’ Internal walls: Concrete block by National Masonry in ‘Grey’; cement render by Rockcote Render; blackbutt hardwood ceilings in Bona Natural finish

Windows: By Allkind in Dulux ‘Natural White’; Whitco awning locks in white powdercoat

Doors: Timber frames by Allkind in Dulux ‘Natural White’; Centor brass rollers and guides and white powdercoated drop-bolts

Flooring: Hamlet bricks by Austral Bowral; hardwood decking by Feast Watson finished with water-repellant decking oil; nilexposure matt-grind concrete

Lighting: Cesta wall, table and globe lamps by Santa and Cole; PH 5 pendant by Louis Poulsen

Kitchen: Stainless steel benchtops and integrated sink by Bridgeman Stainless in No. 4 finish; satin 2pac in Dulux ‘Natural White’; blackbutt island with Evolution Hardwax Oil by Whittle Waxes; Blum Tandembox drawers and hinges; Fisher and Paykel appliances; Grohe tapware; Inax Sugie tiles from Artedomus

Bathroom: Corian benchtops in ‘Cameo White’; Blum drawers and hinges; Grohe tapware; Argent and Grohe toilets; Duravit and Lindsey Wherrett basins; Linear Standard towel rails in matt white; Inax Sugie tiles from Artedomus Heating and cooling: and Ducted airconditioning by Daikin; 28-panel solar array with Enphase inverters

External elements: National Masonry grass pavers in grey; Hamlet bricks by Austral Bowral

Other: Wells dining table and Title bed and coffee table by Mast Furniture; custom lounge upholstery in Instyle Calibre ‘Aesthetic’ fabric; Jasny dining chairs by Nomi

HOUSES 149ALTERATION + ADDITION 33

Architect John Ellway Architect mail@jellway.com jellway.com

07

Project team John Ellway, Hannah Waring Builder Robson Constructions Engineer Ingineered Landscape architect Studio Terrain Landscaping Werner Weis Landscapes Building certifier Bartley Burns

Products

HOUSE FOR BEES BY DOWNIE NORTH

34

01

HOUSES 149 35 02

Words by Ben Peake Photography by Clinton Weaver

When designing a home, the architect-client relationship can be complex and delicate, but also immensely rewarding. Its success relies on an initial trust on both sides, a dedication from the architect to understanding the specific values of the client, and a collaborative process between both parties that identifies the shared values they wish to instil in the design. With no pre-defined or off-the-shelf outcome, a values-driven design process can make anything possible; therefore, that process is one of collectively finding the right thing to do, both for the client and for the site. By going on this journey together, the architect and the client have a shared responsibility for the outcome.

It’s clear that this is a process that Cat Downie and Dan North of Downie North have created with their client, Sarah, and her family when designing an extension to their home in Sydney’s Mosman. The modest addition creates a new area for living that is both comfortable and generous, and its title – House for BEES – is both a reference to the family’s names (Barney, Eddie, Evan and Sarah) as well as a tribute to the design intent of being focused on the garden and its hive for native bees.

The new extension’s angled roof is formed as a single, expressive plane that creates a generous volume, which drops down to reinforce a horizontal

view of the garden through two walls of sliding doors. A strategically placed north-facing clerestory window brings direct winter sun into the living room to fall across joinery, accentuating the space created between the old and new roofs.

Downie North has deployed a classic indoorsoutdoors design move that helps improve everyday activity by making the garden more visibly and physically connected to the home. Structural columns sit on the inside of the building line and allow its eastern and southern edges to disappear when the sliding doors are open. These operable facades combine with the composition of the angled roof to orientate you toward the existing vegetable garden. It’s a connection the clients are now enjoying more than before – Sarah describes how the new spaces encourage the kids to pick fresh herbs for dinner.

Within this threshold between inside and outside, the skill and thoughtfulness of the architects is evident. Large timber-framed glass doors slide away easily and completely to stack in the hallway, opening up the entire wall to the garden. The angle and geometry of the roof create a deep eave outside the building, providing weather protection to the windows and a place for operable louvres that ensure the home can breathe in all weather, even when the big doors are closed.

01 The south-facing addition steps up from the existing house and features an angled roof that draws in light and air.

02 Retractable doors on the southern and eastern edges peel open to unite house and garden.

03 A clerestory window admits warming winter sun from the north into the addition.

HOUSE FOR BEES 36

Compact in size yet richly rewarding to the lives of its occupants, this new living pavilion in Sydney’s Mosman employs porous edges to allow family life to unfurl into the garden.

HOUSES 149ALTERATION + ADDITION 37 Floor plan 1:400 05 m 1 6 11 2 7 12 3 8 13 13 4 9 555 10 1 Kitchen 2 Pantry 3 Dining 4 Family 5 Bedroom 6 Study 7 Laundry/ mud room 8 Living 9 Sun room 10 Terrace 11 Shed 12 Pergola 13 Vegetable garden 03

The overarching design move of the roof form and windows is supported by a subtle design that aims to complement daily life, not control it. A wall of joinery partially separates the kitchen and the living room, concealing the messy areas of food preparation and providing shelving and a screened ledge for the TV. An existing timber table is used as the kitchen island, providing texture and welcome contrast to the new joinery. Cork-tiled floors create a warm and gentle texture underfoot.

Cat and Dan have worked with their client to design a home that is responsive to the client’s brief, environment, and site context while also enhancing everyday living. And yet, this design was undertaken within the constraints of a Complying Development Code (CDC) application. The CDC process in New South Wales defines a permitted building envelope on existing sites – placing limits on size, volume, proximity to boundaries and overshadowing – that does not require separate council approval, avoiding lengthy negotiations with council and neighbouring residents. Consequently, it is often seen as a process of maximization: What is the largest volume of development that can be achieved on a particular site within a predetermined building envelope? Resulting developments often lack architectural ambition and nuance due to the absence of site-specific consideration in their design. But here, in the hands of skilled architects and an informed client, the team has balanced the restrictions of this type of planning application with a design that responds to the built environment context and the landscape opportunities of the garden. This, once again, is testament to a values-driven design approach that focuses on doing what is right, not just what is possible.

House for BEES embodies all the qualities you expect from Downie North. Cat, Dan and Sarah each added to the story of the home’s design, reinforcing the idea that good architecture comes from a collaborative process. Recognition of this collaboration can be found in the children’s bedroom, where a series of three timber sculptures depicts characters that represent the clients, the architects and the builders. Made by a First Nations artist, these sculptures are a tribute to the necessary trinity of skills required to achieve good design, and to a proudly shared ownership of the finished outcome.

Products

Roofing: PREFA Aluminium standing seam roof sheeting in ‘Patina Grey’; Colorbond Klip-Lok in ‘Windspray’

External walls: Dry-pressed bricks from Austral Bricks in Dulux ‘Natural White’; existing brickwork Flooring: Portugal Cork Traditional cork tiles; reclaimed kauri pine floorboards to match existing; solid blackbutt treads

Doors and windows: and Bespoke western red cedar windows and doors from Windoor; Brio brass flush bolts

Kitchen: Custom birch plywood joinery; six-millimetre stainless steel benchtops with integrated sinks; Minokoyo mosaic tiles from Academy Tiles; Wolf 91 cm freestanding dual fuel oven/stove, Qasair Albany Island rangehood, Fisher and Paykel refrigerator

Bathroom: Di Lorenzo Viola Oro mosaic floor tiles; Jatana Interiors Dark Camel wall tiles; vanity, toilet suite and tapware from Just Bathroomware

Heating and cooling: and Heat and Glo 5x fireplace from Jetmaster; ceiling fans

External elements: Site-reclaimed sandstone flagging for garden bed retaining walls; site-reclaimed brick for external paving

Other: Antique rug hanger for clothes drying; B&B Italia Le Bamboozle Sofa; Getama Ring Chairs from Great Dane Furniture; Flos Tab floor lamp, Thonet dining chairs

04 A partial wall of joinery provides practical separation between the kitchen and living areas.

HOUSE FOR BEES 38

2

43

Alteration + addition Sydney, NSW Site 666 m² Floor 210 m² Design 12 m Build 9 m Family+1 powder room

House for BEES is built on the land of the Borogegal and Cammeraygal people.

HOUSES 149ALTERATION + ADDITION39 04

05 Operable louvres tucked into the eaves of the folded roof provide ventilation in all weather.

Section 1:400 05 m

Architect Downie North +61 2 8386 2043 studio@downienorth.com downienorth.com

Project team Catherine Downie, Daniel North Builder Wrightson and Co Structural engineer SDA Structures Hydraulic engineer ADCAR Consulting

HOUSE FOR BEES 40

05

HOUSE FOR BEES MEET THE OWNERS

WORKING WITH AN ARCHITECT

01 In summer, when the doors are open, “the garden feels like it’s in the living room,” Sarah says.

02 The roof tilts up to scoop northern light into living spaces. Artwork: Margie Carew-Reid.

homeowners Sarah and Evan

architects Cat Downie and Dan North from Downie North with a brief for a sustainable home to suit their busy family life. Sarah talks to Alexa Kempton about the process of working with an architect.

Photography by Clinton Weaver

Alexa Kempton Can you start by telling me a bit about yourself?

Sarah I used to work in fashion. It was great, but very unsustainable, and over time I realized that being environmentally responsible was more important to me than looking good.

I love the idea of things being aesthetically pleasing, so then I studied interior design, and I now run a design and decoration business. I also love gardening – I always have loved it.

AK When did you decide to engage an architect?

S My husband Evan and I bought this place in 2014. It’s a Federation-era house, but it had all these strange add-ons at the back, and there was a big backyard that was completely disconnected from the house. We lived in it for a few years and then had children, so we needed to reconfigure the house to suit life with two small boys. We approached a few architects initially. We began working with one architect but, six months into that process, I wasn’t sure about the direction it was going in, and so we started talking to Cat and Dan from Downie North.

AK What made you change course?

S The fit with the first architect didn’t feel right. Cat and Dan understood family living and the need to have different zones within the house. They really got it. Their aesthetic was also more in keeping with my own. During the early stages, I talked a lot about recycling materials like the bricks, choosing environmentally sustainable materials such as cork flooring, and using passive design principles, and they really embraced that brief. Some of my ideas were a bit crazy at times, but they took them all on and then came back with ways to achieve them. They really listened, and they understood both Evan and me, although Evan’s taste is a bit more reserved than mine.

AK What else was in your brief?

S Evan and I both love to cook, but the kitchen that we had before was so tiny. We grow a lot of veggies in our garden. We wanted a big kitchen, and a strong connection to the garden and to the trees around us.

42HOUSE FOR BEES

Sydney

approached

01

AK You mentioned that sustainable design was a key component of your brief. To what extent did Downie North’s design surprise you?

S Enormously. I would never have imagined what we’ve got now. The glazing to the north is amazing, the roof scoops up to allow natural light in from all directions – there is so much going on to manage light and ventilation. The louvres under the eaves are my favourite part of the house. They’re so clever. I’d have them all through the house if I could. The way they passively cool the house when we have the doors shut is incredible. And it’s all hidden. I also love the way the glass doors slide back and disappear by tucking into the hallway. It’s beautiful, and it makes so much sense.

AK It sounds like a very practical family home.

S And in summer it’s just wonderful to be in. We entertain the whole time. When the doors are open and the kids are running from one end of the house to another, there’s a lovely warm feeling. The house has a real ambience. The garden feels like it’s in the living room.

AK Did you encounter any obstacles during construction?

S When the roof structure first went up, Evan worried that the room would be too dark, so we decided to put in a skylight above the

dining area. It does highlight the peach tree when it’s in full blossom, which is delightful. But in hindsight we didn’t need to do it. Cat, Dan, our builder Nathan Wrightson, my design mentor Helen Tunbridge – they all told us we didn’t need it, but we went ahead anyway. We should have trusted them wholeheartedly.

AK What challenged you during the process?

S Inevitably, the money was the biggest challenge. I spent more on variables than I needed to. I think you always get to the end and run out of money. The upshot was that, during the 2021 COVID-19 lockdown, we all got into the garden and did the landscaping ourselves.

AK How did you find and select your builder?

S The building team came to us through Downie North. They were amazing. We all shared the same sense of sustainability and care for the planet. I feel really blessed that we had Nathan on our side. He was calm and measured, and he was happy for me to be on site and to be involved. Eddie, our son, and I cleaned bricks during the summer while the house was being built. I paid Eddie a dollar a brick – and he spent his earnings almost entirely on lollies!

AK What do you think is the most important thing to consider when choosing an architect and a builder?

S It all comes down to personality. Find people you gel with. It’s a hard enough process already, without throwing difficult relationships into the mix. So many people asked me if we were still friends with our architects. Cat and Dan are absolutely still our friends.

AK What advice would you give to someone who is considering working with an architect?

S Do it. There are so many things that you won’t think of until you’re on site and you have to make decisions on the fly. The fundamentals are so important, and by working with an architect, most of those things are resolved before you even start building. It’s a financial hit initially, but it’s worth it. It makes the entire process cleaner and more considered, and the finished result is more rigorously thought through.

AK It’s a bit like a game of chess – thinking so many moves ahead.

S Exactly! They have the foresight to see what might be needed. And to know what won’t be.

AK Would you do it again?

S Definitely. Evan might not. But I would! For sure.

43 HOUSES 149WORKING WITH AN ARCHITECT

02

Foomann

ONE TO WATCH

Led by Jamie Sormann and Jo Foong, this studio untangles constraints to yield quiet, thoughtfully detailed and environmentally responsive homes that are finely tuned to the lives of their occupants.

Words by Peter Davies Photography by Willem-Dirk du Toit, Eve Wilson

“A union of utility and simplicity.” This is how Jamie Sormann, co-director of Melbourne architectural practice Foomann, describes the philosophy at the heart of the studio’s compact, hardworking residential projects.

“The result hopefully looks simple, but it’s hard to execute: accommodating a complex functional arrangement and having it feel neat and elegant,” adds co-director Jo Foong.

Foomann was established in 2008, when the former uni friends were several years into their early careers – Jo at B. E. Architecture, Jamie at Maddison Architects. In the years since, they’ve produced a collection of quiet, thoughtfully detailed residential and hospitality projects that are finely tuned to the lives of their eventual users.

When Jo and Jamie talk about their work, their enthusiasm is shared equally between describing the end result and discussing the array of constraints they navigated to get there. For them, defined constraints – whether physical, budgetary or material – usually yield a better outcome.

“There are a whole range of advantages for the city if we live in more compact homes,” Jamie says. “Yet living in small spaces is often seen as a sacrifice. The conventional idea is to take the biggest house you can afford in the suburb that you want. We don’t agree with that at all; we think smaller homes can feel a whole lot better to occupy.”

At a neat 100 square metres, Haines Street House is a good example. Originally designed by Morris and

Pirrotta in the early 1970s, it has particular significance for the practice – it is Jamie’s own home. Tall and narrow, the concrete-block house is arranged across split levels, with an open-tread stair zigzagging through the middle. An initial 2014 renovation reinvigorated the interiors, consolidating some spaces and making it liveable for the two-person, one-dog household.

A 2022 update, spurred by the arrival of Jamie and his partner’s two children, saw the addition of a timberwrapped box atop the roof, housing a third bedroom and second bathroom. The jewel in this latest renovation is the outdoor bath that sits up top, gazing up to the sky. It is whimsical yet practical and, as Jamie describes it, very much in demand. “The kids ask to use it every day – even in winter when it’s raining,” he laughs.

The same rigour is evident in Canning Street, where a new structure bookends an existing cottage. Under a swooping convex roof form, the long, lean new volume accommodates an open-plan living, dining and kitchen zone. The internal rhythm is determined not by enclosed rooms but by a set of bays along the eastern perimeter, each defined by function (desk, fireplace, record collection and so on). The interior experience is modulated by the curving of the ceiling above.

“We like to take natural materials and form them into one beautiful palette. We love the textures inherent in the base materials, rather than applied colours,” Jo says.

FOOMANN 44FOOMANN 44

01

02

01 Practice directors Jamie Sormann and Jo Foong.

02 At Haines Street House, a rooftop addition respects the scale of the existing 1970s house.

03 A private deck and outdoor bath are seen from the stair at Haines Street House.

Photographs 01–03: Willem-Dirk du Toit.

03

45 HOUSES 149ONE TO WATCH

“

The conventional idea is to take the biggest house you can afford in the suburb you want. We don’t agree with that at all; we think smaller homes can feel a whole lot better to occupy.”

– Jamie Sormann

“You don’t need typically luxurious materials to have a luxurious experience. You can achieve it through good design, through proportions and through craft,” Jamie adds.

These ideas thread through the team’s Ballantyne Street House in Melbourne’s inner north. Retaining the original dwelling as a zone for the kids, the team appended an airy, flat-roofed pavilion to the rear. Once again, constraints drove the solution: the clients sought only as much space as they needed and wanted to keep as much of the garden as possible.

Timber beams and pillars express the extension’s structure, framing windows, shelving and a linear study leading to the parents’ retreat at the rear of the new build. Expansive windows and doors connect to the garden beyond, with wide eaves to help keep the interior cool in summer months.

Sustainable thinking is embedded in Foomann’s work, thanks in no small part to Jo’s recent certification through the Passive House Institute. “It’s changed our approach a little – we have to push the thermal envelope further,” Jo says. “In Europe they’ve been doing Passive Houses for thirty years, but that approach is in its infancy here.”

Jo and Jamie are advocates for better quality design, both in their own practice and more broadly in the profession through their involvement with ArchiTeam, a co-operative of small practices from across Australia. “Whether sustainability is in the brief or not, there are always levels of efficiency we can provide to any client. That’s just what a good building is,” Jamie says. foomann.com.au

04 Canning Street is a compact, 110-square-metre home for a young family. Artworks, (L–R): Carley Bourne, Stanislas Piechaczek; (top): Ash Holmes.

05 A convex ceiling creates different spatial experiences within the smallfootprint home.

Photographs 04, 05: Eve Wilson.

FOOMANN 46

04 05

Green scene

From carbon offsets for bricks to chairs that repurpose plastic waste, this range of products supports a responsible way of life.

Find more residential products: selector.com and productnews.com.au

01 Stainless steel tapware

Stainless steel is an incredibly durable and corrosion-resistant material. Vola creates beautiful forms from stainless steel, with textures that echo those of the natural world and manufacturing methods that minimize environmental impact. en.vola.com

04 Responsibly sourced timber

Eco Timber Group is a source of locally manufactured, FSC-certified hardwoods, and it promotes the use of recycled timber and responsible forestry. Its products were used in Baker Boys Beach House by Refresh Design.

Photograph: Christopher Frederick Jones. ecotimbergroup.com.au

02 Sanctuary DC ceiling fan

The Sanctuary DC ceiling fan’s wide-reaching blade span and powerful airflow make it ideal for large, open living areas and covered outdoor spaces. Its three sculpted solid timber blades make it a stylish yet commanding feature that supports natural ventilation. universalfans.com.au

05 Eres collection by Paola Lenti Environmental sustainability, ecological balance and renewable materials are each central to Paola Lenti’s Eres (meaning “earth”) furniture collection, in which linen, hemp, bamboo, raffia, igusa and abacá are the eco-conscious materials of choice. dedece.com

03 Climate Active initiative

This opt-in program allows customers to specify and procure any clay brick made in Brickworks’ Australian facilities as a certified carbon-neutral product. An audit verified by Energetics enables Brickworks to undertake a lifecycle analysis and purchase carbon credits. brickworks.com.au

HOUSES 149 49 PRODUCTS

01

03

05

02

04

06 Aeron chair

Herman Miller’s iconic Aeron task chair has been re-engineered to repurpose oceanbound plastic. By redirecting and reforming this material, the company prevents an estimated 150 tonnes of plastic from entering and contaminating oceans each year. livingedge.com.au

09 Raw Earth collection by Bentu Nature is at the core of Nongzao’s Raw Earth lighting collection, and it inspired an innovative manufacturing method that combines soil with biodegradable plant fibres. The collection’s six lighting designs are cast from diatomaceous earth and metallic minerals. remodern.com.au

07 Paragon rug

Meticulously hand-knotted, the Paragon rug is reminiscent of a vintage rug, with a contemporary twist. The Armadillo collection embraces the principles of slow design, advocating for a gentler pace of life that is kinder to the community and the environment. armadillo-co.com

10 Grandeur Living

Grandeur Living is a luxurious, 100 percent wool loop pile carpet that provides natural insulation to keep you warm in winter and cool in summer. The biodegradable wool fibres combine comfort and sustainability to enrich any room. godfreyhirst.com

08 Duet tapware collection

Duet is inspired by the beauty of duality: two ideas collaborating to create something larger and better than themselves through mutual attraction. The collection’s elegantly oblong forms are versatile and functional. Sussex is a net zero carbon emissions company. sussextaps.com.au

50SUSTAINABLE PRODUCTS

06 07 08 09

10

High-tech ventilation with the Fanco Habitat Expert

As we build more low-energy homes that are tightly sealed, we need to consider how to provide adequate ventilation in order to ensure our homes are healthy and energy efficient. Opening windows can provide ventilation, but the energy that has been spent cooling or heating the internal air is lost.

The Fanco Habitat Expert is a decentralized heat recovery system that provides a constant source of fresh air to a home, maintaining indoor air quality while also retaining its existing heat.

The unit operates in cycles: First, it extracts air from within the home through the wall for 70 seconds. Then it switches to an intake mode, drawing external air into the unit. On each extraction cycle, the unit retains heat from the outgoing air stream. When it switches to an intake cycle, that heat is transferred to the incoming air. This heat transfer reduces the home’s overall energy consumption.

The Habitat Expert also has a ventilation mode that provides fresh and filtered outdoor air, bypassing the heat exchanger. This can be used to provide a cool breeze in summer time.

The Habitat Expert provides multiple benefits:

– One of the models comes with wi-fi and is compatible with SMART Technology, which allows homeowners to control the unit via smart phone and connect to additional units, including enabling multiple units to work in sync.

– The model with wi-fi connection does not need to be wired to a central point or to another unit, making it much easier to install than models that do. This is a unique feature in the Australian market.

– The system features a high-quality ceramic accumulator, which retains up to 93 percent of heat energy.

– A humidity sensor ensures adequate ventilation, preventing mould and mildew.

– The system has an antibacterial treatment that prevents bacteria generation inside the regenerator.

The Habitat Expert is one of the most sophisticated and energy-efficient solutions to living well and sustainably.

The system provides constant mechanical ventilation while maintaining the room temperature using minimal electricity.

The Habitat Expert includes a G3 filter and can be fitted with an F8 filter (PM2.5 99%) as an accessory. This filter can help to remove finer particles from the air, including smoke, car exhaust fumes and pollen fragments (Environment Protection Authority [EPA] Victoria, 2021).

These pollutants and allergens can lead to respiratory symptoms, particularly for those living with allergies, hay fever and asthma (EPA Victoria, 2018).

Prioritizing energy efficiency and healthy indoor air quality, this ventilation system provides a constant source of fresh, filtered air while also using a heat transfer to reduce a home’s energy consumption.

01 Hawk’s Nest Residence by Contech, with the Fanco InfinityID Ceiling Fan. Photograph: David Sievers.

02 The Fanco Habitat Expert heat recovery system.

National Distributor of:

For more information, visit fanco.com.au/fancohabitat-expert-wifi or universalfans.com.au

UNIVERSAL FANS SHOWCASE 52

UNIVERSAL FANS SHOWCASE

01 02

Words by Josh Harris

01 Beaumaris Modern 2 by Fiona Austin and Simon Reeves (Melbourne Books, 2022)

Melbourne’s bayside suburb of Beaumaris has changed a lot since the 1950s and ’60s, when dirt roads and sandy tracks weaved between untouched bush and the avant-garde homes of the architects and artists who flocked there in search of an alternative to the usual subdivision. Today, as land values have skyrocketed, many of the experimental, modernist homes that were built in the mid-twentieth century have been demolished, replaced by generic new builds. This followup to 2018’s Beaumaris Modern continues the work of documenting the homes that have survived the waves of development, acting as a pointed reminder of what first attracted people to the suburb. The new book brings 17 additional surviving houses “out from behind the trees,” including lovingly preserved homes by the likes of Peter McIntyre, Anatol Kagan and Geoffrey Woodfall as well as hidden gems by lesser-known architects such as Charles Bricknell and Judith Brine. A few of these homes have been in the same family for generations, but most others have been bought by new owners who appreciated their modernist design and relationship to the surrounding bush. We hope, as do the book’s authors, that Beaumaris Modern 2 inspires the suburb’s next generation to hang on to that modernist heritage.

02

Arent & Pyke: Interiors

Beyond the Primary Palette by Juliette Arent and Sarah-Jane Pyke (Thames and Hudson Australia, 2022)

Juliette Arent and Sarah-Jane Pyke of Sydney interiors practice

Arent and Pyke don’t do monochrome. Colour is integral to this, their first monograph, just as it is to their work – from the variegated greens that connect a house to its garden to the soft pink that gives a room a rosy glow. The book concentrates on the practice’s residential work, and it celebrates the ways that colour can create visceral joy. “For us, to talk about colour is to talk about memory, but also meaning, energy and emotion,” explain the authors. Each house is introduced with the expected data – floor area, number of bedrooms – as well as the number of colours used. There are 11 colours in the first project, an opulent home by the sea in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, where cream-and-grey marble sits alongside rich crimson fabrics. In the next – a renovated Federationera worker’s cottage – there are seven, including the mossy green of the living room sofa, which defines the house’s earthy palette. Juliette and Sarah-Jane, who provide insightful commentary on their design decisions throughout, explain that for them, colour is a continual source of inspiration that can evoke particular moods and shape the experience of a space. Above all, it can create joy.

03

Cape

to

Bluff: A

Survey of Residential Architecture from Aotearoa New Zealand by Simon Devitt, Andrea Stevens and Luke Scott (Independently published, 2022) This sprawling book takes us tramping across the full length of Aotearoa New Zealand, from Cape Reinga on the northenmost tip of Te Ika-a-Māui North Island to the town of Bluff in the deep south of Te Waipounamu South Island. It features 30 houses designed by New Zealand architects, each with a deep connection to the landscape around them. Mountain House by RTA Studio cuts an angular, sculptural figure against the craggy, snow-capped peaks of Kā Tiritiri o te Moana; Light Mine House by Crosson Architects appears as a ramshackle cluster of pods dotted across the rolling sand dunes of Kūaotunu; Reef House by Strachan Group Architects is a tidy nest perched on the clifftop overlooking Tīkapa Moana Hauraki Gulf; and Ophir House by Nott Architects is a modernist sci-fi retreat on the surreal, moonscape-like terrain of the Maniatoto. With photography by Simon Devitt, words by Andrea Stevens and layout by Luke Scott, this is a work of impressive scope that provides an extensive catalogue of Aotearoa New Zealand residential architecture. It is a celebration of place, and of architecture that embraces place. In that way, it is a success, inspiring awe and envy.

04 Tasmania Living: Quiet, Conscious Living in Australia’s South by Joan-Maree Hargreaves and Marita Bullock (Thames and Hudson Australia, 2022)

Tasmania, Joan-Maree Hargreaves and Marita Bullock write, is a place where nature looms large, where cities and towns are diminutive and the open sky “offers an encounter with the immense.” Against this dramatic backdrop, Tasmania Living takes us on a tour of a diverse group of homes, from a restored Greek Revival villa to a Farnsworth House-esque glass holiday home, and tells the stories of their occupants. The authors note that the houses highlight the “art of living quietly” in the natural environment, while demonstrating a sensitivity to Tasmania’s history. They reflect on the brutal realities of colonialism and consider how living consciously on lutruwita/ Tasmania today entails hearing and recognizing the Palawa as the ongoing owners of the land. However, given its focus on “asking bigger questions about our place and purpose,” the book is noticeably quiet on the housing affordability crisis battering the island – a crisis at least partially driven by a market that prioritizes prestige projects over affordable housing.

Despite this blind spot, this is a thoughtful work that encourages contemplation and reflection. It is also a handsome book filled with breathtaking scenery and exceptional architecture.

53 HOUSES 149READING

01

Bookshelf 04 02

03

54 01

PENTHOUSE BY OFFICE ALEX NICHOLLS

HOUSES 149 55

ELSTERNWICK

remarkable

Words by Sing d’Arcy Photography by Rory Gardiner

Starting with a blank canvas is confronting. Starting with one that is enormous and doesn’t even exist, even more so. But rather than being daunted by the task, Alex Nicholls was able to draw on his artistic and tectonic skills to design a multigenerational home on the rooftop of a new Elsternwick apartment building that is a play of composition, colour, materiality and light.

This rare commission for a 350-square-metre penthouse was a choice project for Office Alex Nicholls, especially for its first in Australia. Alex, who practised architecture in the UK and Europe before returning home to Sydney, had met the clients a few years earlier when he had designed a retail space in Tel Aviv for their son. So impressed were they with his work that, when it came time to building their own home in Melbourne, they approached Alex to take on the mammoth task. The first challenge was that the site didn’t even exist. The clients had bought off-the-plan and the building was under construction as Alex began working on the designs. The clients wanted the two top-floor apartments joined into one large, multigenerational home for the family, and part of the associated basement-level carpark space turned into a wellness area. Alex explains that they didn’t want a “typical commercial-developer interior” that comes with off-the-plan purchases.

The clients had specific requirements that needed to be addressed in the design, and the only way that these could be successfully accommodated was through a custom design. Firstly, the home had to be “completely flexible” to work as either a multigenerational home or, if the need arose, two independent units. Secondly, the home needed to be future-proof, allowing the clients to age in place – so accessibility and wellness were paramount. On top of the complex brief, the service stacks of the building were already in place, so Alex had limited ability to change the locations of bathrooms and kitchens. In lesser hands, this commission would have probably ended up being a big, bland box. Alex, however, approached it with far more artistic flair and precision.

The big risk when working with the dimensions of a long and large floor plate and standard ceiling height is that the end result is a flat, pancake-like interior with large swathes of flooring and white ceiling. Alex addressed this issue by conceiving the perimeter

01 The commission was to adapt two apartments into a singular, flexible and future-proof home. Artwork: Ellie Malin. Sculptures: Bettina Willner.

02 Stairs connect the penthouse to two rooftop pavilions. Artwork: Kasper Raglus. Sculptures (L–R): James Lemon, Bettina Willner.

03 A colour-block drawing illustrates how colour has been used to distinguish between zones.

ELSTERNWICK PENTHOUSE 56

A

brief to reconfigure two top-floor apartments into an adaptable, multigenerational home is met with precision and artistic flair, combatting flat, rectilinear design with colour, composition and light.

HOUSES 149APARTMENT57 02 03

04 Half-moon skylights link the apartment and the sky, drawing the eye upward. Vase: Katarina Wells. 05 The apartment’s spatial sequence is gradually revealed, achieving a complex and engaging environment.

ELSTERNWICK PENTHOUSE 58

05 1 Library/lobby 2 Library 3 Mess

4 Dining 5 Living 6 Laundry 7 Bedroom 8 Music and art room 9 Study 10 Evening

11 Kitchenette 12 Outdoor pavilion 13 Outdoor kitchen 05 m

12 12 13 Penthouse

7 7 7 3 8 8 4 5 5 2 9 10 6 1 2 11 9

04

kitchen

garden

Rooftop plan 1:400

plan 1:400

walls as “the site” and then the elements of the interior as “buildings.” He therefore avoided the dominant tendency of flatness and made the different spaces read as three dimensional. Office Alex Nicholls works a lot in modelling and prototyping – the models are sculptural artworks in themselves – and this process is evident in the way in which joinery has been designed. Nothing in this apartment is just a box. Alex’s ambition was to create “a rich environment,” observing that “as you age, you want the experience to be complex and engaging.” The spatial sequence of the apartment is therefore gradually revealed, each room offering visual snippets of the adjoining one, carefully weaving connections between large-volume open spaces and smaller, discrete rooms. This idea of complexity and engagement is developed not only through the spatial configuration but also through the use of colour, materiality and detail. Alex used coloured drawings – themselves beautiful artworks – to illustrate how blocks of colour anchor the reading of the spaces, achieving a careful balance of neutral and bold. The neutrals are the floors, ceilings and walls, wrapped in Australian blackbutt, travertine and polished plaster; the bolds are the sculptural joinery elements and the reveals of bathrooms, and fireplaces that are like the silk linings of a fine item of clothing. The two anchor colours are a desert pink and a turquoise blue. Not easy colours to handle well, but once again Alex’s artistic experience in painting informs his approach to design. Floating above these are half-moon skylights that connect the apartment to the sky. These skylights also reduce the pancake feel by drawing the eye upwards rather than horizontally to the perimeter windows. Alex says that skylights were the clients’ idea and, as Elsternwick is noted for its Art Deco buildings, Alex suggested the curved shape. Once again, a complete control of compositional understanding is demonstrated through the dialogue between the void curves in the ceiling plan and the solid rectilinear elements of the floor zone.

This project is big, but it’s not brash. Office Alex Nicholls has tempered any risk of extravagance, allowing for the luxury of space to be the key experience. There is a sensitivity and assuredness in the use of colour, material, form and composition. Alex’s explorative, hands-on approach through painting, drawing and sculpting is a refreshing change from the image-driven flatness that tends to dominate much of contemporary residential design.

Floor 350 m² Spa 100 m² External 250 m² Design 12 m Build 18 m

Products

Internal walls: Polished plaster by Bishop Master Finishes in ‘Satin’

Windows: Exterior sliding doors with PPC aluminium frames from Schueco; internal pivot doors in PPC aluminium from Vitrosca

Doors: Pivot doors from Fritz Jurgens in ‘Satin’; door hardware from D Line in ‘Satin’

Flooring: Honed travertine from Signorino; blackbutt floorboards from Hurford; honed sandstone from Gosford Quarries

Lighting: Lighting from Viabizzuno Kitchen: Honed quartzite from Signorino; Vola tapware in ‘Satin’; 2-Pac joinery from Touchwood in ‘Persimmon,’ ‘Wild Clary’ and ‘Green Turquoise’; custom blackbutt sink designed by Alex Nicholls, made by Wood and Water; custom blackbutt handles from Touchwood Cabinetry

Bathroom: Honed quartzite from Signorino; tapware from Vola; blackbutt joinery from Touchwood; custom blackbutt bath designed by Alex Nicholls, made by Wood and Water

External elements: Honed travertine from Signorino Other: Custom entry bench, designed by Alex Nicholls and made by Touchwood; furniture and lamp from Viabizzuno, Modern Times and Stylecraft

HOUSES 149APARTMENT 59

4

Apartment Melbourne, Vic

2–4 3

Elsternwick Penthouse is built on the land of the Boon Wurrung people of the Kulin nation.

Multigenerational family

06

06 A library spine running east to west connects the two living zones of the expansive apartment.

Artwork: Ellie Malin.

Vase: Bettina Willner.

07 Distinctive colours define the kitchen areas, which can be concealed behind pivoting doors when not in use.

Vase: Bettina Willner. 07

ELSTERNWICK PENTHOUSE 60

08 A west-facing living space named the “evening garden” is designed for indoor-outdoor use. Vase: Kerryn Levy.

08

Designer Office Alex Nicholls +61 404 194 273 studio@officealexnicholls.com officealexnicholls.com

Project team Alex Nicholls Builder Cobild Architect (building) Ewert Leaf Styling Jess Kneebone

HOUSES 149APARTMENT 61

CARINGAL FLAT

BY ELLUL ARCHITECTURE

62

HOUSES 149 63 01

fastidious reworking

Words by Alexa Kempton Photography by Rory Gardiner

Words by Alexa Kempton Photography by Rory Gardiner

As anyone perusing one-bedroom apartment listings today will attest, it’s rare to find one with views in all four directions; near impossible, when you limit your search to those that are accessible to a first-home buyer. Yet that is what architect Ben Ellul found: a 58-square-metre studio apartment in the inner eastern Melbourne suburb of Toorak, in the state-heritage-listed Caringal Flats, originally built in 1951.

Caringal Flats was designed in an era of radical experimentation in urban living, and its concrete construction, cantilevered balconies and large panels of glazing signal it as an example of early modernism in Australia. Its architect, John W. Rivett, was likely influenced by the work of international modernists including Edwin Maxwell Fry, Serge Chermayeff and Erich Mendelsohn as well as Melbourne precedents such as Frederick Romberg, architect of the Newburn and Yarrabee flats (with Mary Shaw) and the Stanhill Flats. Caringal was, however, distinct from its local precursors in form: heritage architect Nigel Lewis describes the uncommon arrangement of the two principal buildings – one six-storey tower of studio apartments and one curving, three-storey building containing twelve two-bedroom apartments – as “without equal in Melbourne.” Of particular interest, Nigel notes, was the provision on top of the curved building of a recreational rooftop space, which served as a communal outdoor garden and children’s play area for residents (it has since been removed). The rooftop was accessed by a bridge from the tower, which, together with the cantilevered stairs and balconies and their tubular steel handrails, lend the building a confident, graphic sensibility. Ongoing work to preserve the state-heritagelisted building has recently restored its vivid coral pink walls and pale blue eaves, carefully matched to remnant paint scrapings taken under Nigel’s guidance. These distinctive hues honour the original intent of the architecture, celebrate it as a landmark and make it all the more extraordinary in a suburb otherwise dominated by sprawling mansions.

Ben’s apartment is one of six in the tower, each one occupying an entire floor. His objective was to strip back the dilapidated interior fitout and install in its place a functional and livable plan that would suit him, his partner Genevieve and their Italian greyhound Vincenzo.

In the reworked plan, the majority of the space is dedicated to a living and dining zone, which makes the most of a large wall of west-facing windows that frame views of the city. Flexibility is paramount in compact spaces, and it is evident here: Ben

01 Occupying an entire floor of Caringal’s six-storey tower, the studio frames an expansive view of the city.

02 The door between the lift lobby and the apartment has been removed to maximize light and views.

Artwork: Max Berry.

CARINGAL FLAT 64

This

of a studio apartment builds on the legacy of its 1950s heritage, finding opportunities for space and sociability in small-footprint living.

HOUSES 149APARTMENT 65 02

and Genevieve’s desire to be able to entertain has ensured the apartment can comfortably host 14 for dinner, thanks to an extendable dining table and a few extra benches (ordinarily used as side tables), all designed and made by Ben and his dad. A wall of freestanding joinery doubles as a divider between the social spaces and the east-facing bedroom.

Ben’s strategy was to “set a language” for the new work, ensuring it was easy to discern old from new. New elements are uniformly black and built from slender, angular steel, contrasting with the bulbous profile and white finish of the existing features. Two datums provide a continuous visual anchor: no built elements extend higher than the top edge of the window frames, while kitchen cabinets and the joinery wall sit above the skirting boards. This device creates continuity and lightness, enhancing the sense of spaciousness. As is often the case with small spaces, the inner workings are those that have required the greatest precision in planning: the bathroom, kitchen and laundry are stacked around a concealed service core, maximizing amenity without compromising aesthetics.