Introduction

The stakes this year are as high as it gets for Ukraine, as challenges arise on the front, behind the front, and on the international arena as well as if it weren’t already enough. Needless to say, the current situation, on tactical, strategic, or political level is precarious, especially as they are all set for major changes that will inevitably influence the war and its outcomes greatly. These changes, events, and/ or actors, can be in large broken down to assess the wests current standing, and the possible outcomes from these future decisions.

Currently Ukraine is facing a rather tense situation as throughout this year major policy changes can be expected as the western political landscape is set to change drastically and rather unpredictably in cases, all the while Russian forces have continued to press on adamantly in the by now renowned Donbas region as Ukrainian forces face an ever more committed Russia both economically, and militarily, together with its allies and supporting partners.

In short, 2024 is going to be a decisive year by any measure, making it even more prudent now more than ever, to understand the key factors thro -

ughout the remainder of the year and the possible ramifications they can have in both and isolated and general scope. Whereby events such as the US election are sure to hold much of the headlines, nevertheless, the Hungarian EU presidency, the ongoing Russian offensive, German elections, British elections and many more are sure to have a profound impact on Kiev’s continued efforts to halt Russian forces militarily or internationally.

With all that in mind, this is not to say that the war and the greater geopolitical rift accompanying it is to end this year, rather, how as a direct or indirect consequence of the aforesaid key events, and in addition to many others, 2024 is definitely going to have a heavy impact on the timeframe of the war as well as the willingness by either the collective west or the eastern axis of resistance to follow through, and or, double down on their respective geopolitical objectives. Which in short would mean Russian objectives in Ukraine and accompanying international efforts for support, Western actions towards Russia in protection of Ukraine, and Western attitude towards the Russo-Chinese cooperation. These commitments are what are on the line this year.

Russia on the battlefield and beyond

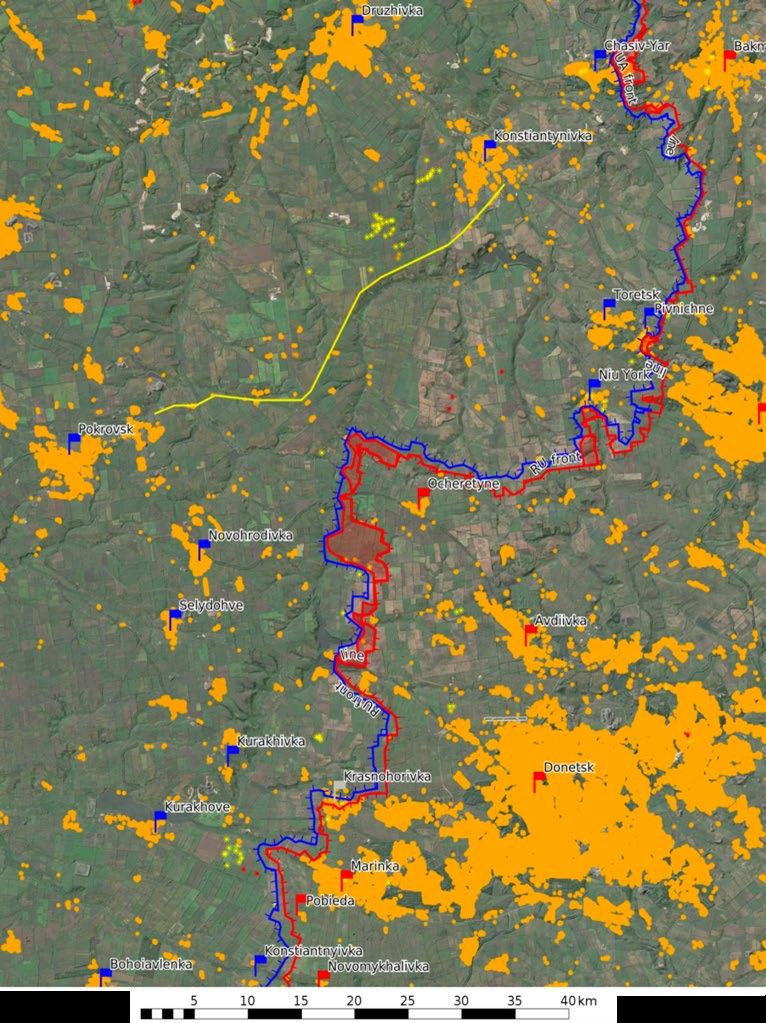

The war in Ukraine militarily speaking is a rather trepid situation as Russian forces continue to attack strategic infrastructure as well as consistently advance following the fall of Avdivka in the Donetsk sector.

The Russian advantage through numerical superiority in firepower and force multiplying assets has been a glaring issue for Ukraine, especially in the cases of aviation, artillery, surveillance, and manpower. Initially, Russian forces suffered

from a general lack of cohesion or understanding, resulting in their forces not being able to carry out doctrinal operations or maneuvers. However, since 2023’s Ukrainian summer offensive Russia has demonstrated a more reformed military posture which is more in line with reality. In turn, this has meant Russia had to constrain their appetite territorially, but instead Russian forces have greatly worked towards harmonizing combined arms warfare elements to be able to work together constructively. These efforts are most pronounced amongst the artillery and air forces (including tactical aviation assets), especially the latter, as command, control, and communication(C3) have become integrated more closely with other branches. This has resulted in shorter kill chains, from detection to destruction, as well as an increase in Russian aviation assets providing close or direct fire support for frontline units.

Russian progress has been costly but constant, as it seems currently the Kremlin is willing to settle for a more aggressive posture along this sector with higher losses. A key factor which has allowed for the Kremlin’s forces to adopt such an aggressive standing is that the skies above the battlefield and operational areas lie uncontested against Russian aviation. Who have plentifully seized the opportunity to rain down ordinance in support of their ground units. However, this issue while not new, is significantly more pronounced as Russian production of aerial standoff weapons, namely the FAB-500, 1000, and 1500 series munitions for which Russia has successfully adapted a makeshift glide kit which has allowed Russian air assets to avoid longer range medium and long-range air defenses.

Nevertheless, the Ukrainian army is making Russia pay dearly for its progress, however, Ukraine’s capacity to thwart Russian advances has become thinly stretched as the Russians have increased the number of sectors in which they are active. Namely, the re-opening of the Kharkiv front which temporarily re-focused

Ukraine’s elite formations and allowed Russian forces in other sectors to press on. However, the re-direction of Ukraine’s more offensive capable units to other sectors is nothing new, however with the manpower and force disparity is increasing between Russia and Ukraine, meaning the opportunity cost for each relocation grows exponentially.

Above all, Russia has greatly increased the degree to which they employ aerial reconnaissance assets, namely through drones such as the Orlan-10. This in turn has made it significantly more difficult for Ukraine to carry out any operation, whether that be as simple as the rotation of troops, or the deployment of strategic assets such as HIMARS. Russian penetration with reconnaissance assets into the deep operational rear, even at times the strategic centers like Odessa and Zaporizsia, has forced Ukraine to curb their general force posture to be more defensive as a whole.

What can be discerned from all the above is that Russia currently holds several advantages, and all of them together pose a precarious and awfully dangerous situation for Ukraine. The combined threats from Russian air and artillery forces have forced Kiev to a larger extent avoid larger grouping of force closer to the contact line, extending lines of logistics as well. This combined with Ukraine’s current inability to effectively counter these Russian advantages has been manifest in the frontline changes.

Additionally, the Russian economy, with significant support from China, has edged closer to a war economy which has meant the Russians have been able to cushion their losses to an extent. More importantly however, in the aforementioned areas of Russian advantages, their expanded military industry has become geared to maintaining these advantages, with a key area being strategic strike capable assets, namely their tactical ballistic missiles and cruise missiles. This in itself is a stand-alone capability of Russia in the war, one which Ukraine does not have a direct

https://usm.media/baza-cf-w-novorosijsjku-perepownena

response to as strikes with western weapons within Russia de jure is yet to be greenlighted, shielding Russian bases from these weapons.

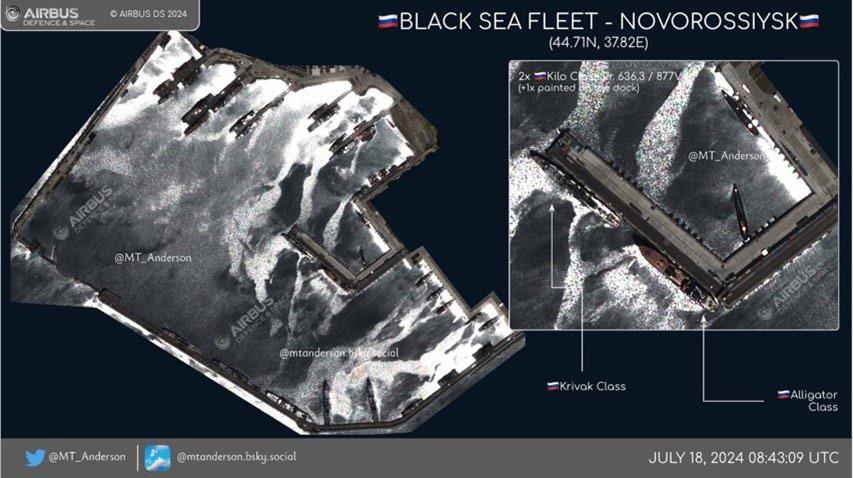

On an endnote, it must be stated how the most comprehensive failure so far for the Russian military since the war has started, was and is their astounding naval blunders. To the extent that by way of Ukraine forcing Russia’s strategic asset positioning, like naval vessels, to be untan-

nable. And to the Ukrainians credit, they have deprived the Russia black sea fleet of the utility of Sevastopol and Kerch as naval hubs. With Ukrainian force projection in the area effectively forcing Russia, for some time now, to use Novorossiysk, significantly adding to the distance Russia ships have to cover to execute black sea patrol operations

Ukraine on the front and beyond

Over May and June, following a green light from the US, Ukraine successfully neutralized droves of Russian air defense systems on the Crimean Peninsula effectively forcing the Kremlin to make compromises on Russian air defense system placements elsewhere. This demonstrates a rather complex situation, whereby it is self-evident that US weapons, and to a larger extent that of the western alliance, can effectively target high value theater defense installations. Moreover, it may

give a hint as to the purpose of the now long-awaited F-16’s as now certain batches in training are now nearing completion and preparations for deployment are underway.

However, Ukraine has been the victim of Russia’s systematic energy campaign seeking to destroy Ukrainian energy infrastructure. The consequences of are dire as Ukraine is set to face the summer, but even more critically, the winter a si-

July/02- July/14 overlay – structures overlay (orange) T0504

MSR (yellow) MODIS/ VIIRS overlay (red/yellow points)

gnificantly reduced power capacity. This is all to say that the situation for the civilian population this winter is definitely going to be challenging, if not the most challenging so far.

Munitions, vehicles, and manpower has been a persistent issue restraining Ukraine’s efforts in the liberation of its territories. However, unfortunately this issue in not limited in scope only to offensive operations as it deeply effects, and has

affected, Ukraine’s ability to hold their ground against the onslaught of Russian forces. While the degree to which they lack these cannot be disclosed or measured precisely, the consequences of it however can be mapped accurately.

This begs the obvious question, what can be done? The answer is as complicated as it is simple in a rather banal sense, Ukraine needs to play for time. What is evident is that Russia cannot sustain the same degree of losses it did in the first two years of the war, both in terms of manpower and equipment, but mainly the latter. Therefore, the only recourse for Ukraine is to demand as high a price for each foot of Russian progress as possible. Of course, this sounds rather simple, but the reality is that due to the previously discussed Russian advantages this task has become incredibly difficult.

However, a point of relief is the west as a collective and their will to support Ukraine. Current levels of support to Ukraine are not enough to realize the objective of complete liberation of all territories in accordance with the 1991 borders. Instead, it is enough to execute a grinding war of attrition through defense in depth, although,

this strategy has its limits. Mainly due to the fact that behind the Donbass industrial region, which ends with the cities of Kramatorsk, Slovyansk, and Pokrovsk, after which there are mainly plains with a general absence of defensible terrain or infrastructure.

What this means is that the clocks ticking for in the Donbass region. Crucially, what is important to understand, and what came to be understood during WW2, is that the fall of either linchpins of the east, that being Kharkiv, or the Donbass would spell disaster. Importantly, this logic applies both ways, equally for the Russians as much as for the Ukrainians.

All in all, the chances of Ukraine to liberate its territories are at the behest of western support, until Ukraine has a foothold in the Donetsk industrial area. For Ukraine to have to abandon this area would spell disaster in its entirety, jeopardizing all major current fronts, all the way from the Kharkiv front to Zaporizsia. Having assessed the west to be in a monopoly situation to determine the outcome over the battle for Donetsk, what are the positions of the collective west and how are they set to change with respect to the war?

The United States

The dawning presidential elections in the US are sure to have changes ensue, especially as the two main candidates, Donald Trump (Republican) and Joe Biden (Democrat), are set to face off. The attempted assassination of Donald Trump has set the stage for a turbulent presidential election with heavy consequences for internal US security policy, but also foreign US security policy.

The US, if it wished to do so, could in theory provide all the necessary equipment from its arsenal to thwart any hopes of Russian success, however the considerations behind doing so, more

specifically not doing so, are extremely nuanced. The US as of now is in a situation where it has to balance its forces between the two main theatres of east and west, namely the pacific and Europe. In addition, the US has a long way to ramp up production of crucial war materials and linked manufacturing capabilities to be able to comfortably sustain involvement in the two theatres simultaneously or even in a theatre against a near peer adversary.

This issue is ever more pronounced as the cooperation between Russia and China only deepens,

however more on that later. This all means that this election has at its core the decision of future US security policy, more specifically the approach to it. Currently the US does not enjoy a unanimous sentiment of unilateral support for Ukraine as it is both divided on the degree to which they give weapons, as well as the extent to Ukraine can use them.

Considering all this in the backdrop of the lackluster re-arming and replenishment effort in the US has led to concerns around the available stockpile of equipment and munitions available for a possible future conflict. At its core, these arguments have their own justification as the US has ceased some major systems production lines or have operated at a reduced rate, warranting a degree of caution around available equipment levels to an extent albeit the numerical availability is not the whole problem. Rather the military industrial logistics of ramping up production is what’s problematic, it is an economic issue at heart.

To illustrate the issue at hand the case of artillery shells will be used to demonstrate it. Currently the US produces artillery shells under the Joint Munitions Command (JMC), where a number of facilities under this command are responsible for certain steps of the supply chain, such as, propellant charger, fuzees, machining, and final assembly in addition to any outsourced private contracts for these steps. Under this arrangement the current capacity to expand is limited due to the loss of skilled labor and capital as most of it now lost after the downsizing following the cold war.

Meaning, any meaningful change from the US towards its policy to Ukraine, military support wise, would have to address the underlying economic issue of creating the underlying industrial and intellectual base to increase production. These issues are more pronounced in cases where the given productions lines have seized to exist.

Therefore, the upcoming elections are set to change the outlook on the US economically, which in turn would greatly influence the US’s ability to influence the current events on the battlefield in Ukraine and elsewhere.

Specifically, Trump is renowned for his wish to return manufacturing jobs to America, such a plan would have far reaching effects as an economic plan that centers around rebuilding industrial output in the US will directly affect the to what extent the US can pursue rearmament efforts. Moreover, Trump’s hawkish policy towards China in conjunction with the war in Ukraine can set the stage for a return of manufacturing jobs in the US that would endow it with both the dual-use capital and educated manpower to follow through on a military buildup.

Meanwhile, President Biden has also addressed issues in the military supply chain, with the most outstanding long-term strategic victory being the Chips Act, FABS act, and the infrastructure bill as it secures general national logistics capabilities as well as elements of the supply chain in precision guided weaponry, as well as bolstering the technically educated manpower in the US. However, the heavy industry aspect of the economy such as steel working or ship building has slowly been in a progressive decline, leading to the loss of educated manpower. However, heavy industry and environmental protection policies are inherently at crossroads with one another meaning that the industrial reconstruction of America would look drastically different under Biden than Trump.

Whether it is Trump or Biden that will be better for Ukraine is yet to be seen, however, a stronger US is advantageous for the collective west as a whole as well as for Ukraine. Importantly, the Biden administration allowed for Ukraine to use ATACAMS missiles on Crimean targets, which proved to be extremely effective, demonstrating the effectiveness of American weaponry. However, for Ukraine to be able to keep its foothold in the

Donbass industrial area Ukraine is going to need a lot more weapons.

Some key items Ukraine needs are artillery shells and systems, IFV’s, MBT’s, anti-air systems, counter battery systems, and electronic warfare equipment. Without any avail amongst these categories of weapons, Ukraine’s outlook is rather bleak. That is discounting the F-16’s. They can prove very effective in mitigating current Russian advantages, especially in breaking Russia’s

localized air superiority over the battlefield and operational areas.

Additionally, any serious commitment to bolstering Ukraine has to address Russian military industrial output, which by large is helped by China as engineering and industrial equipment from the west have been restricted due to sanctions. Meaning, if Russia is to be stopped on the battlefield, the larger military industrial supply chain has to be affected to a greater extent.

European Union and Europe

The EU, now under a Hungarian presidencies term, has ruffled the status quo of diplomatic isolation of European member states, in addition to the EU as a whole, from Russia. The Hungarian presidency, not long after assuming their mandate embarked on a ‘peace mission’ to Kyiv, which would be the first time for the Hungarian president since 2012, as well as to Moscow. Needless to say, this is quite the turnaround for the EU as an institution, nevertheless, not unexpected with the Hungarian presidency, to an extent.

On the diplomatic level, what can be expected from this? It gives the perception that the Hungarian presidency is seeking to instill a view that the EU can positively leverage Hungary’s duplicitous position regarding Russia in contrast to the rest of the EU member states. The extent to which this endeavor would succeed is rather limited, if anything due to the rightfully unwilling position of the Ukrainian government to yield to any concessions to Russia.

However, on a more individual basis across Europe and in the EU is that a more conservative sentiment is on the rise across Europe after years of the EU’s divisive migration policies, but how does this effect the war in Ukraine? Truth-

fully, the effects of the rise of right leaning parties in the EU and in member states effects internal policies between the collective west to a greater extent than any direct effect policy wise towards Ukraine regarding support. Alternatively, it may lead to a rise in a more skeptical view on cooperation with China and a more aggressive sanctions regime against proxies supporting Russia.

In addition, an EU and its member states which are more focused on domestic issues could lead to an increase in sentiments supporting rearmament. Examples of conservative governments increasing investments in the defense sector are already visible, as the general trend of increased defense spending has not lapsed since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine especially in eastern European countries where this trend is most precedented.

However, western Europe in comparison is yet to follow suit with this trend as the ramifications of the by now persistent economic slowdown following covid recession and the war are still being felt. Nevertheless, what is a trend as well in western Europe is that after the end of the cold war the current force posture is and untannable position in the long run, and their militaries and related industries require a massive overhaul.

Dong, J. (2023). A Cauldron of Anxiety: War or Peace?. w: Chinese Statecraft in a Changing World. Springer, Singapur. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-6453-6_7

Prime examples of the underlying issues in post-cold war military polices are evident in Britain and Germany rather acutely. With Britain being increasingly aware of its faltering military capabilities, in spite of boosted defense spending recently. However, as mentioned previously, the UK is in trouble with finding the funds to allocate for a renewed drive in military spending. Likewise, Germany under its new more conservatively dominated parliament looks for ways in which to reform its military and industry, and that effect has already increased defense spending to the highest amount since the end of the cold war.

While it important to note these developments will take time and significant political will, what is a noteworthy mention, however, is how the discussion around remilitarizing has changed especially in Germany. A country which after World War 2 was traumatized into pacifism

is now slowly again engaging the idea of being more forceful towards nefarious actors the like of Russia. This is possibly the biggest change in Europe since the start of the war as Germany with all its industrial might has ardently refused to engage any ideas of military reforms.

With the economic powers of Europe, France, Germany, the UK, and in a rising fashion Poland, edge towards and increasingly unified sentiment towards increasing European defense capabilities in aggregate. With the main countries lagging behind, in the sense of general spending and equipment acquisition, being Germany and the UK amongst others. So how does this translate into the larger geopolitical rift globally?

A more militarily capable EU and Europe would inherently have positive effects for Ukraine, however, more importantly it could lead to an increasingly ‘western’ security perception eco -

nomically. Whereby, in the long run the EU and Europe would seek security for its economy and military industries and supply chains from hostile powers. Naturally, the guns and butter argument applies, as such a course of actions would not come cheap by any means, however,

the rising prevailing sentiment, as visible in the discussions around increasing military spending, is that this opportunity cost is increasingly worth it in the face of the threat against the values of the collective west.

China

China in the recent decade has pursued and aggressive expansion of its military forces in all domains, extending to both conventional and nuclear forces. Aircraft, Ship, and land system procurements in China have kept up their pace, if not accelerated, and the surrounding and supporting industrial ecosystem enjoys ever increasing government investments. This has led to, most concerningly, the relatively rapid expansion of China’s nuclear forces amongst all parts of the nuclear triad. So, what conclusions can be extrapolated from China’s fast paced military expansion?

As is already well established in recent history, China’s near term geopolitical objective is the consolidation of its force projection capabilities within the first island chain, which are mainly concentrated around the south China sea and centered around Taiwan. The development of a capable blue water naval force, in addition to the illegal military bases in the area, to tangibly contest the region against the US. The reasoning behind such a commitment to the region both financially and politically can be explain rather simply, trade and vulnerability.

The vulnerability aspect has developed as a perception in China after the 1996 Taiwan strait crisis, whereby US forces were able to swiftly assert naval dominance over the region. This experience has aided in the development of China’s force posture with respect to the three

island chains, separating the Chinese mainland from the Hawaii. It is within this geostrategic reality that China has been pursuing their military buildup, although this way of perception extends to a Chinese national security element as well, as the island chains provide prime staging operations either way, east or west.

Trade wise however, the island chain perception also aided in the liability-based perception of south China transit trade, as China in spite of having sizeable oil reserves, imports oil from the middle east to a significant degree, which pass through to main straits, the strait of Hormuz and the straits of Malacca. This is a rather glaring strategic vulnerability for China and provides a follow up answer in the context of geopolitical rift discussed throughout the report. Influenced heavily by this vulnerability there is one other strategic partner available to China in an effort to satiate its energy demands, Russia.

Additionally, the fact that Russia is isolated and waging a war allows for China to exploit the situation due to Russia’s rather lacking list of willing economic partners amongst developed countries in its geographical vicinity. Meaning the relationship between Russia and China is inherently precarious for China as Russia’s diplomatic ‘gloves’ already came off since the onset of the war, nevertheless, China is still treading a thin line of balancing its relations with Russia and the collective West.

However, to explore the Russo-Chinese relations a little more, it has to be stated unequivocally, it is not a partnership of equals, not at all. Rather, China heavily dominates the relationship owing to its sheer economic might which holds China’s ambitions hostage as much as it does the collective West’s aims against either Russia or China. Although for Russia, such an exploitative demeaner in its relations with China to its own detriment would seem illogical, but the reality of the situation is that it is a matter of necessity.

With Russia’s economy focusing heavily on supporting the war effort, the commercial market for general goods and services has been filled to extent by Chinese companies, deepening Russia’s dependence on China. However, from China’s perspective this is an advantage, as were the aforementioned trade routes for oil become interrupted, Russian oil is a comfortable alternative, especially, as Russia has no other option available to them in terms of customers for their oil.

With everything said, one’s impression might be that China is withering through the war in Ukraine with relative comfort, as well as benefits mainly through their revised relations with Russia. However, that is not the whole picture, and is only a half truth. The reality is China’s

willing cooperation with Russia has exposed its Achillies heel, trade, albeit its one for China as much as it is for the collective West, to an extent.

Importantly though, the extent of this disparity in vulnerability between China and the collective west is that while the later can seek to repatriate a more automated manufacturing industry, although with very significant costs, there will still be consumers for the products that are manufactured in the collective west. Meanwhile, in China the towering trade surplus it has would mean any isolation from western markets would force China to seriously reconsider its economic strategy, as domestic Chinese consumerism cannot abate the surplus consumer goods that China would be left with, even if Russia’s consumer goods demand is included.

This exposes the underlying risks of the current global dynamic, whereby, Russia and its war effort via its economy is in an absolute sense greatly subservient to China and its economic lifeline. However, that economic lifeline exposes the collective west to increased scrutiny for its double standards, as well as the simple fact that trading with China could very well aid Russia in its war effort.

Summary

Therefore, the collective west is at a crossroad, where the decision has to be made down the road whether China and Russia can be treated as a separate issue or has to be treated as a one. This is the question that that western countries lack a unified position on, with the US having a more China hawkish policy while the EU as a collective is more hesitant on addressing the issue as it is more or less kicking the can down the road for now.

A noteworthy mention is how the US’s balance of trade with China, and the EU’s balance of trade, are relatively equal in proportion, complicating the rational reasoning behind the difference in policy positions. But can be more easily be explained with economics, whereby the US it seems has the societal willingness to suffer the consequences of engaging China more forcefully at the cost of short-term, albeit significant, economic fallout.

Meanwhile, the same cannot be said for the EU, which has already been forced to make fundamental changes to its economic structures following covid and the Russo-Ukrainian war, with the emphasis on the latter and the subsequent rearrangement of the EU’s energy market at a heavy cost.

Therefore, the issue boils down to a fundamental global difference in perception, whereby the benefits of globalization are becoming more limited, while strategic cooperation within one’s economic or political entity becomes more favorable. Therefore, how does this all effect the main and current issue, the war in Ukraine?

Well, a commitment to a more fragmented global economy based on strategic and geopolitical interests, as would be the case if the collective west is to in a unified manner treat Russia and China as one issue. As opposed to the indivi-

dual rapprochement towards China in order to separate the Russo-Chinese partnership wherein there would be no major fragmentation of international supply chains and markets. From Ukraine’s view, naturally the former is better, due to the inherently more aggressive foreign policy it stands for, contrary to one that solves the issue individually.

The strategic outlook globally, is one where the decision to embrace multipolarity or to attempt the saving of globalism has not yet come about. Until then, large proactive actions from both sides cannot be expected, however, once the more globalist countries, currently the collective west, embrace a more proactive diplomacy and policy, contrary to the current reactive setting. Although, it is my humble opinion that the collective west has no other choice, either now or later, to act in a decisive proactive manner, as the only thing that will change, is the cost of persevering.

Author:

Benjamin Bardos is the lead author of the Transatlantic Perspectives journal at European Horizons, focusing on transatlantic security and defense issues. In addition, he is currently doing an LLM in Global Law at Tilburg University. He is also a member of the Hungarian Atlantic Youth Association, focusing on NATO military policy and European security architecture.

© COPYRIGHT 2023 Warsaw Institute

The opinions given and the positions held in materials in the Special Report solely reflect the views of authors.

Warsaw Institute Wilcza St. 9, 00-538 Warsaw, Poland +48 22 417 63 15 office@warsawinstitute.org