1 THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND BEYOND IDEOLOGY: (DE)CONSTRUCTING NOVEMBER 13, 2022 - MARCH 12, 2023

Copyright © 2022 by The Wende Museum of the Cold War (De)constructing Ideology: The Cultural Revolution and Beyond was organized by Jamie Kwan, with Joes Segal and Emma Diffley. Additional support from Anna Atkeson, Emma Balda, Anna Rose Canzano, Jane Friedman, and Mika Wang. Special thanks to Fiona Chalom. This exhibition is generously supported by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Catalogue design by Ananya Madiraju Photographs by Yosi Pozeilov and Ian Byers-Gamber

2

INTRODUCTION

The Cultural Revolution was a unique movement within China’s history: a period of social, economic, and cultural upheaval that would radically change the path of the nation. In the late 1940s, after the Sino-Japanese War, the nation underwent a civil war and an armed revolution resulting in the establishment of the People’s Republic of China under the leadership of Chairman Mao Zedong (18931976) and the Chinese Communist Party. Recognizing the critical role of the arts in forwarding the socialist cause, Mao announced another revolution in his later years—one within the cultural realm that officially began in 1966 and ended only with his death in 1976.

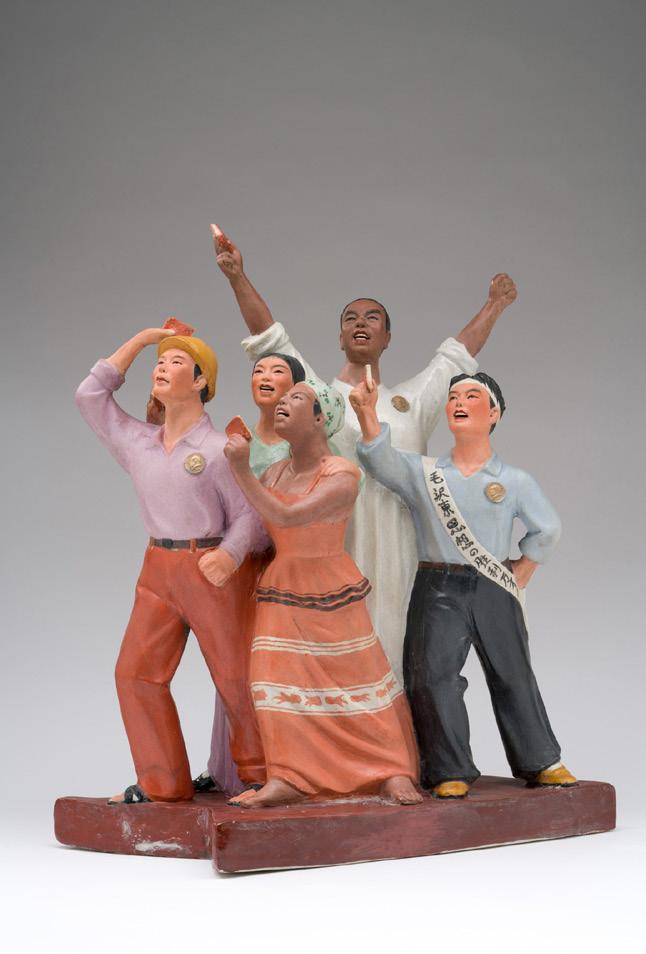

How did artists adapt to the dramatic changes in official art production that occurred during this period? What was the lived experience of Chinese citizens in relation to the arts? Focusing on ceramics made in Jingdezhen, the nation’s porcelain capital, this exhibition presents the visual culture of the period and examines the different facets of Maoist art theory. China has a history of porcelain production that dates back thousands of years, but the Cultural Revolution uprooted these traditions, catalyzing the creation of new forms and styles. Works from the period feature vessels or plaques painted with revolutionary subject matter, or sculptural tableaux, created from a series of molds. These ceramics, along with the examples of painting, printmaking, performing arts, textile, and ephemera, give us a glimpse into the distinct aesthetics of the period.

Imagery from the Cultural Revolution lives on today, especially in the realm of contemporary art. Artists have appropriated and reinterpreted the visual legacy of Maoism in order to highlight personal experiences, political ambiguities, or the tensions between remnants of the Mao cult on the one hand, and post-Maoist society on the other. Our opening section Mao Now provides a modern lens through which we currently experience the visual culture of the movement.

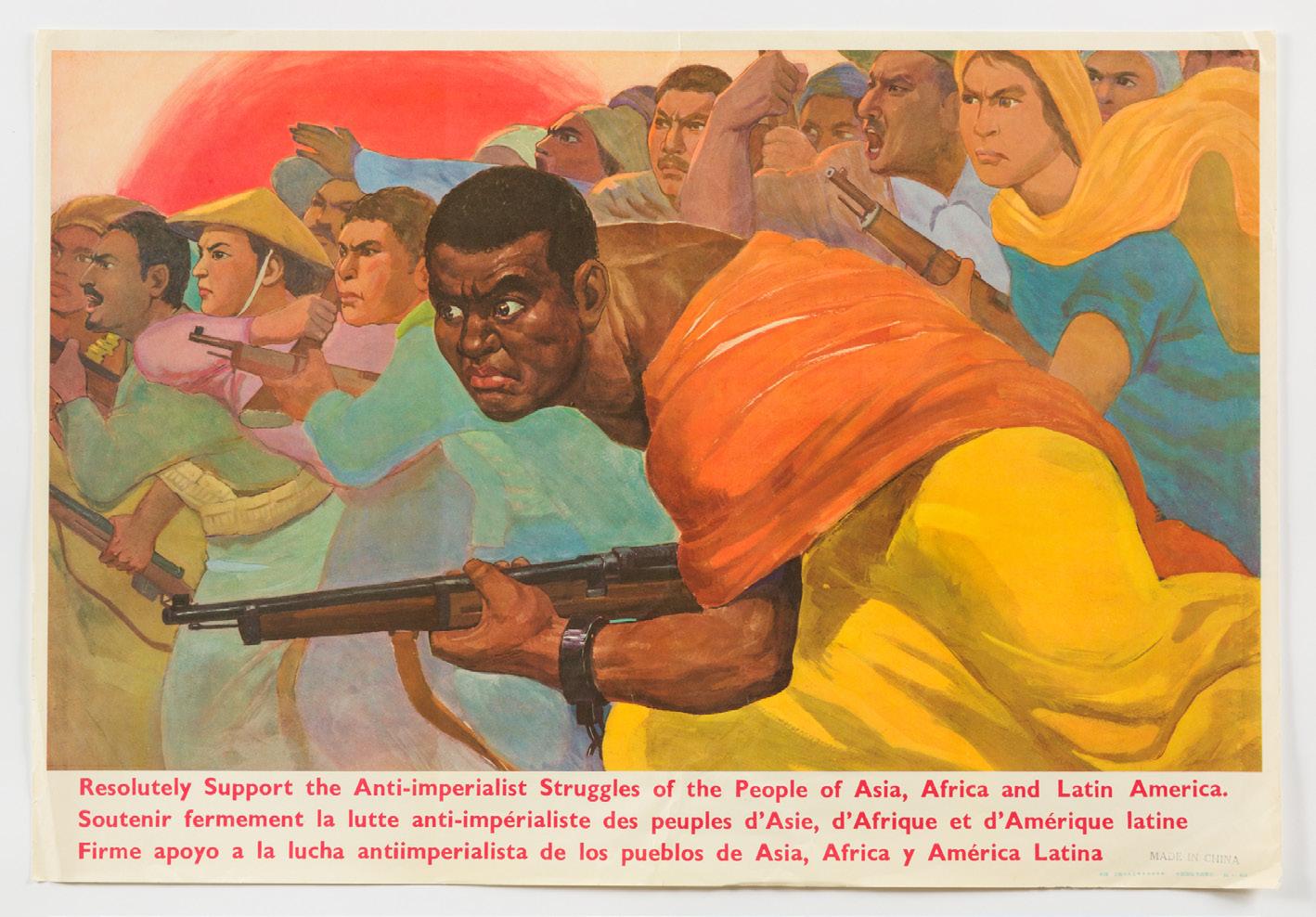

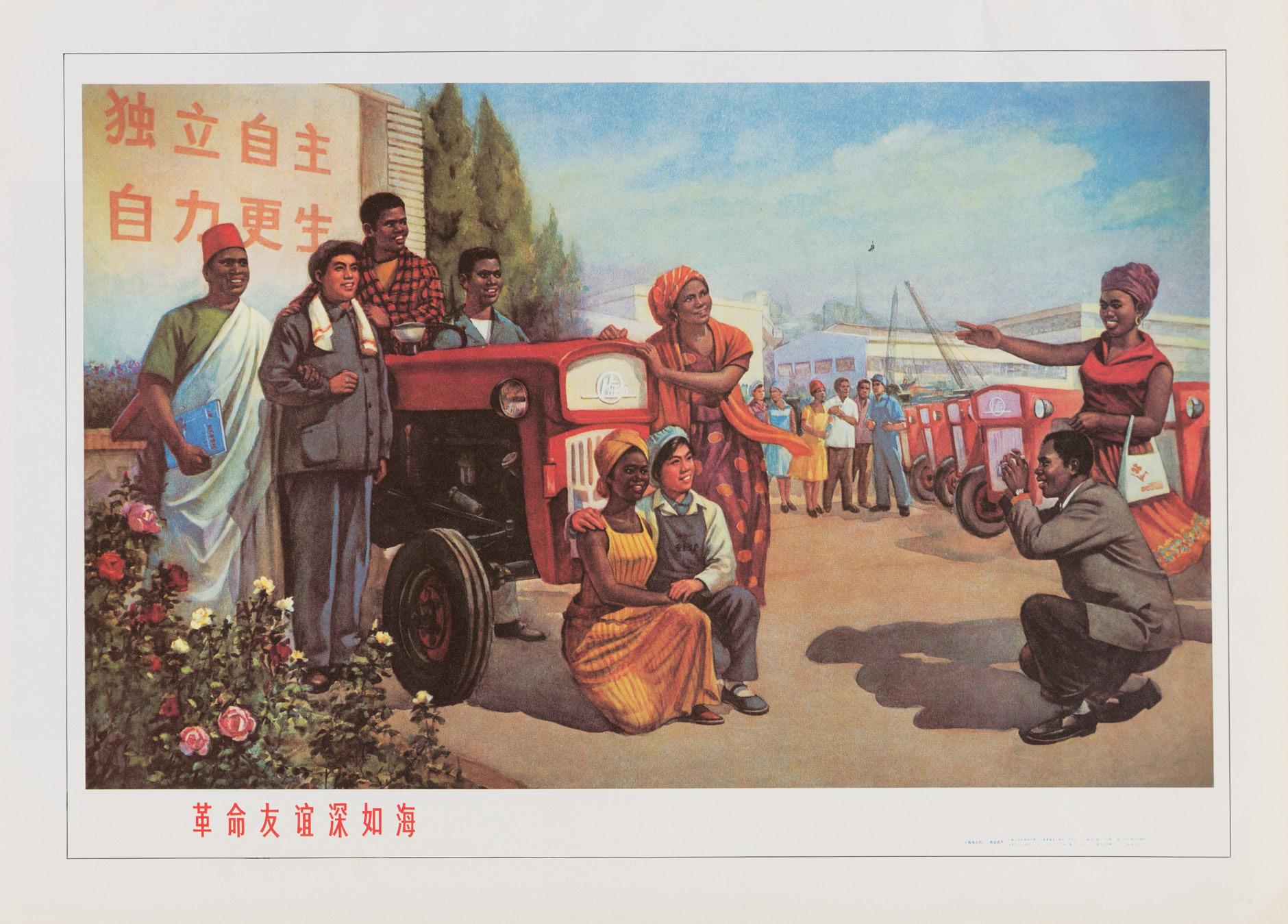

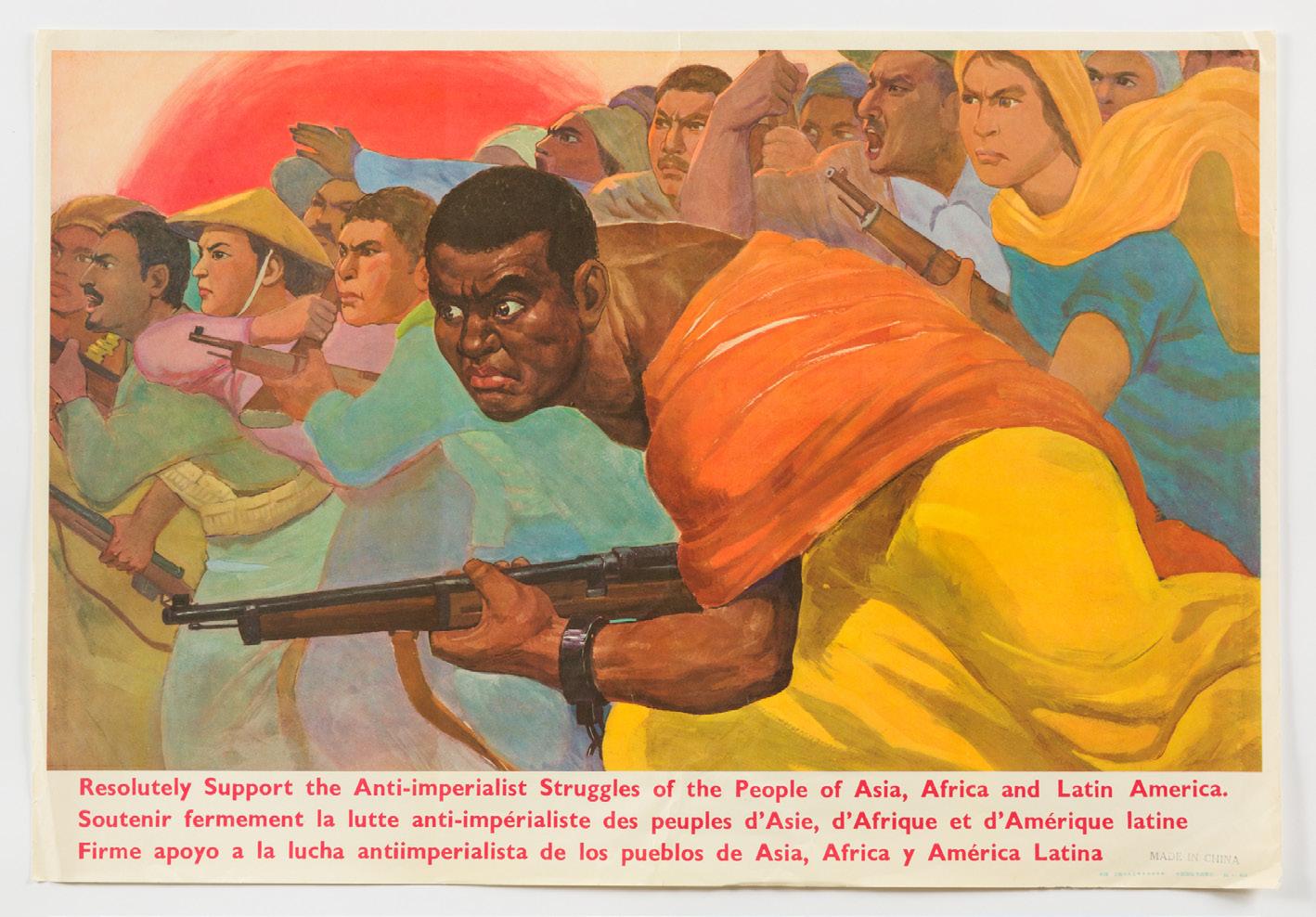

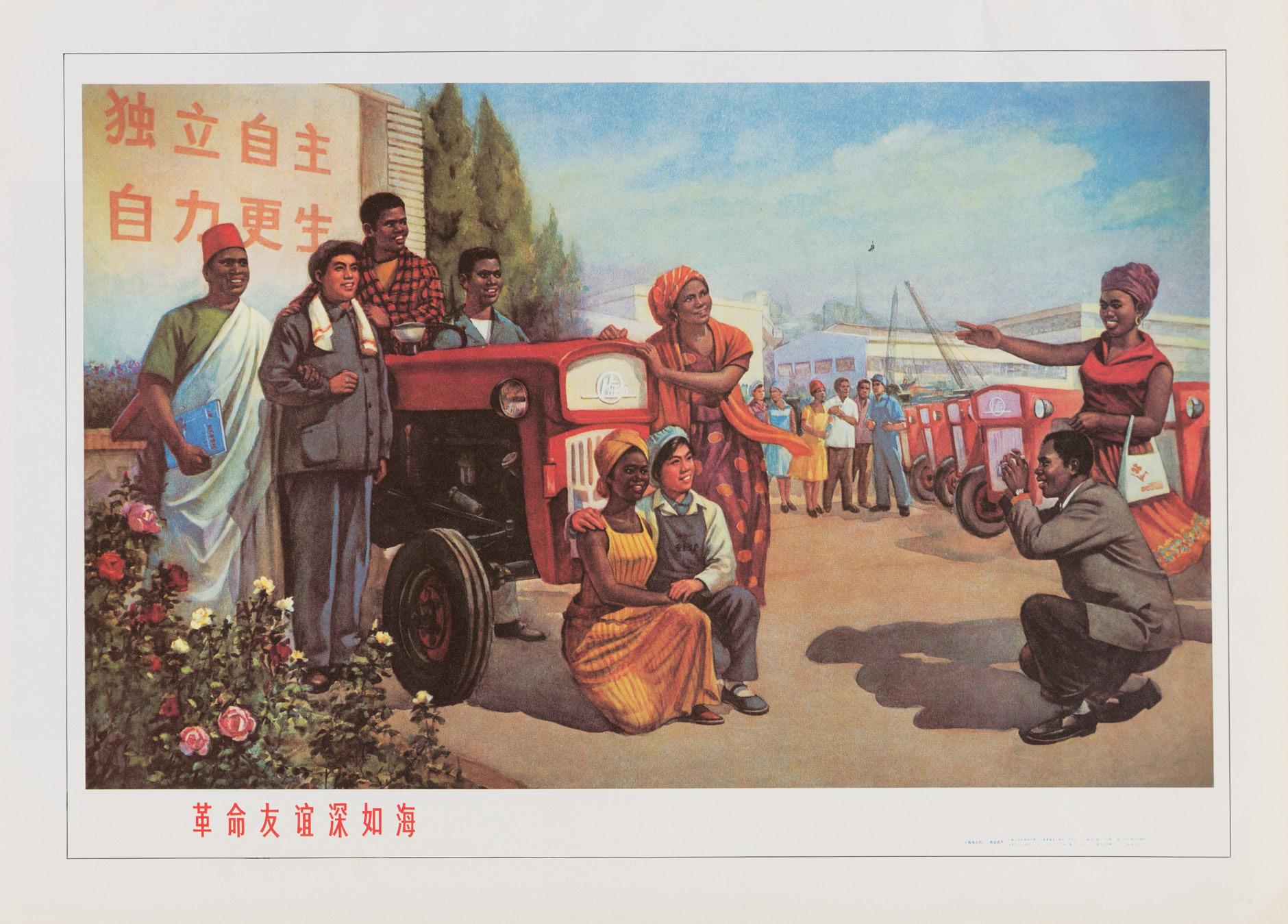

The Cult of the Chairman examines role of Chairman Mao Zedong as the uncontested leader of the People’s Republic of China and center of a national personality cult that fueled the movement. Ideology and Iconoclasm looks at the early years of the Cultural Revolution, which witnessed the rise of the Red Guards and mass iconoclasm. Workers, Peasants and Soldiers, The Model, and The Revolutionary Landscape examine different elements of Maoist art theory—how it shaped artistic creation but also how artists found agency to create works in spite of strict government guidelines. The final section, China and World, addresses Chinese international relations during the Cultural Revolution, tracing the nation’s ties with other Socialist countries as well as its changing attitudes towards the West.

By examining these objects, we explore how Mao’s policies shaped artistic creation—both during the Cultural Revolution and today—and how artists found agency in their craft to create works despite government censorship and ideological restrictions.

1

1

Chronology of Events Surrounding the Cultural Revolution

1911: The last Qing Emperor Puyi abdicates after a series of revolutions across the nation; revolutionaries led by Sun Yat-sen establish the Republic of China

1912: Sun Yat-sen becomes the first President of China

1921: Foundation of the Chinese Communist Party

1925: Sun Yat-sen dies; Chiang Kai-shek becomes leader of the Nationalist Party

1934: Long March begins as the Nationalists attempt to suppress the Chinese Communist Party

1935: Long March ends and the Chinese Communist Party establish their new headquarters in Yan’an

1937: Beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War; Chinese Communist Party and Nationalists form a united front against Japan

1945: Sino-Japanese War ends; beginning of Chinese Civil War between the Nationalists and Communists

1949: Chinese Communist Party wins the Civil War and establishes the People’s Republic of China with Mao Zedong as Chairman; Nationalists flee to Taiwan, where they establish the Republic of China

1958: Mao enacts the Great Leap Forward

1962: The Great Leap Forward officially ends

1966: Mao declares the start of the Cultural Revolution; formation of the Red Guards

1968: Mao recalls the Red Guards; students are sent en-masse to the countryside

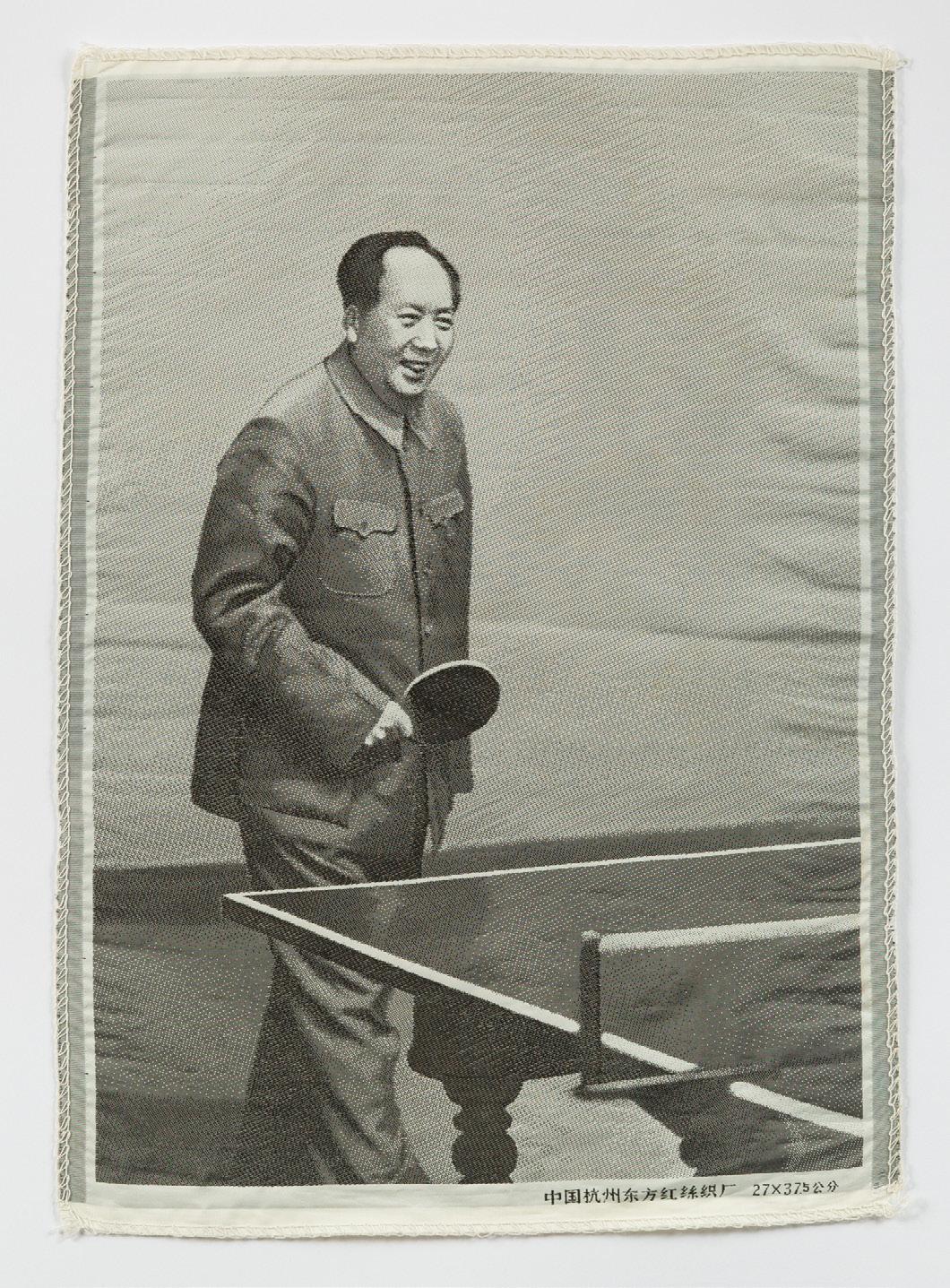

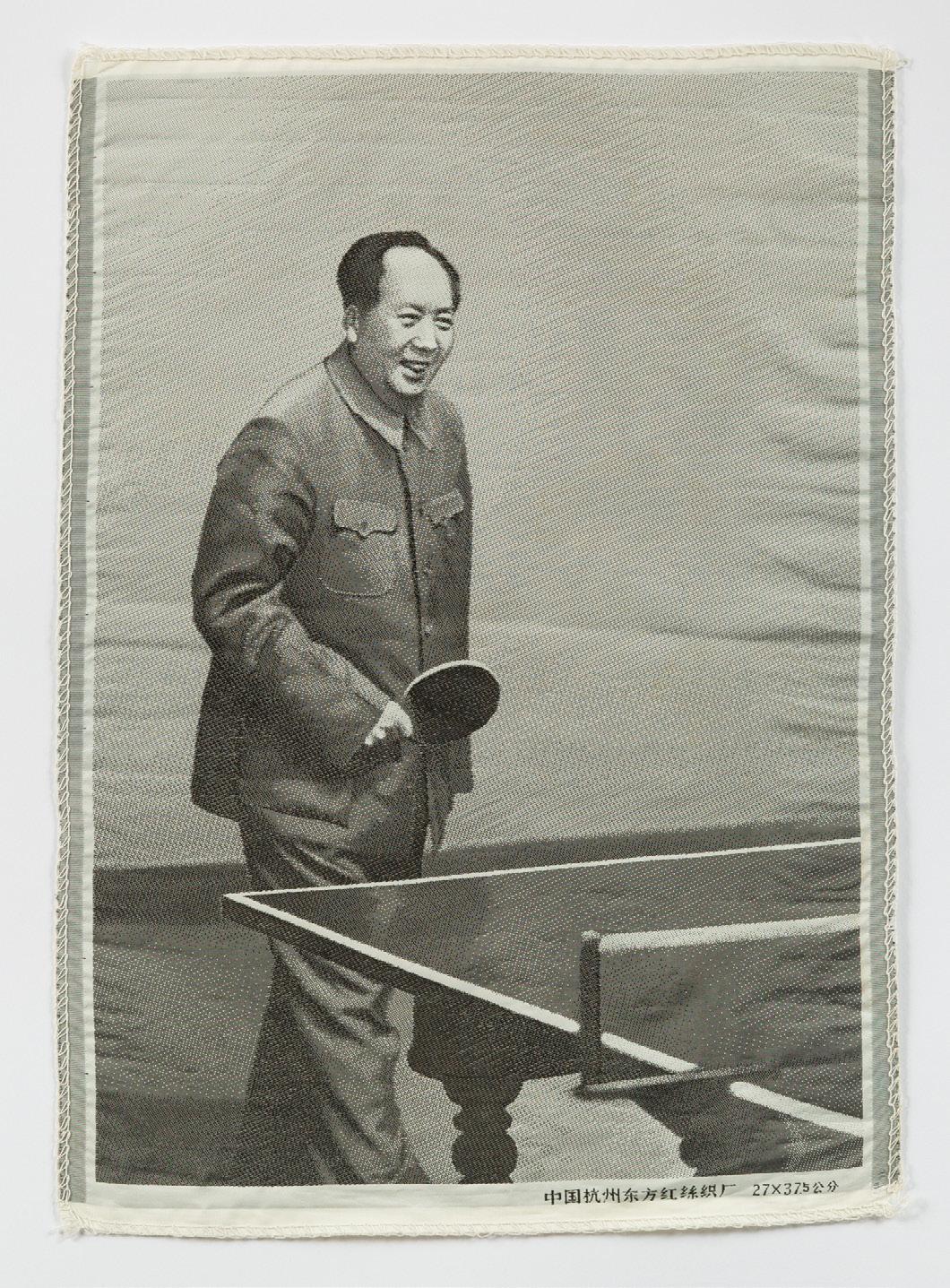

1971: Lin Biao dies; beginning of ping-pong diplomacy with the United States

1972: President Nixon visits China

1976: Zhou Enlai dies in January; Mao dies in September and the Cultural Revolution officially ends; Hua Guofeng becomes the Chairman of the Communist Party; the Gang of Four is arrested and officially tried

1978: Deng Xiaoping, who has ousted Hua Guofeng and serves as the de-facto leader of the nation, announces China’s new Open Door Policy to foreign business

1979: The People’s Republic of China and the United States establish the official diplomatic relations

1981: The Chinese Communist Party officially denounces the Cultural Revolution as a “mistake”

2

2

MAO NOW: CONTEMPORARY ART

Although the Cultural Revolution officially ended nearly fifty years ago, the imagery from the period—portraits of Mao, images of Red Guards, and scenes from the model performances (a set of operas, ballets, and a symphony sponsored by the government)—lives on. The government’s strict set of rules governing the arts resulted in the creation of a distinct, even iconic, aesthetic that would spread across China and outlast the end of the movement.

Contemporary artists from both China and abroad have appropriated and adapted these images for their own purposes. Zhang Hongtu, Vivienne Tam, Li Shan, and Sui Jianguo play with the famous portrait of the Chairman as commentary on Mao’s cult of personality, while artists such as Elizabeth Gill Lui, Li Tianbing, and Xing Danwen address lived experience as well as collective and personal memories from the period. Zhang Dali’s prints explore the power of mass media and photographic manipulation during the Cultural Revolution. On the other hand, works by Wang Guangyi and Hung Liu that reuse imagery from the model performances are more cryptic in their meaning— is their Mao-era imagery intended to critique Communist policy, a comment on Western culture, or maybe both?

Xing Danwen

Born with the Cultural Revolution

1995 Chromogenic print Courtesy of a private collection

Xing Danwen’s triptych features her pregnant friend juxtaposed with iconic portraits of Chairman Mao and the Chinese flag in the background. The work evokes the passing of time and the changes in China, from the Cultural Revolution to the nation’s transformation as a global, economic superpower. Xing herself was born in 1967; she lived through the Cultural Revolution as a child and experienced firsthand the fast-paced economic and social developments of the 1980s and 90s. Her triptych explores themes of personal and collective memory and questions the lasting impact of the Cultural Revolution.

3

3

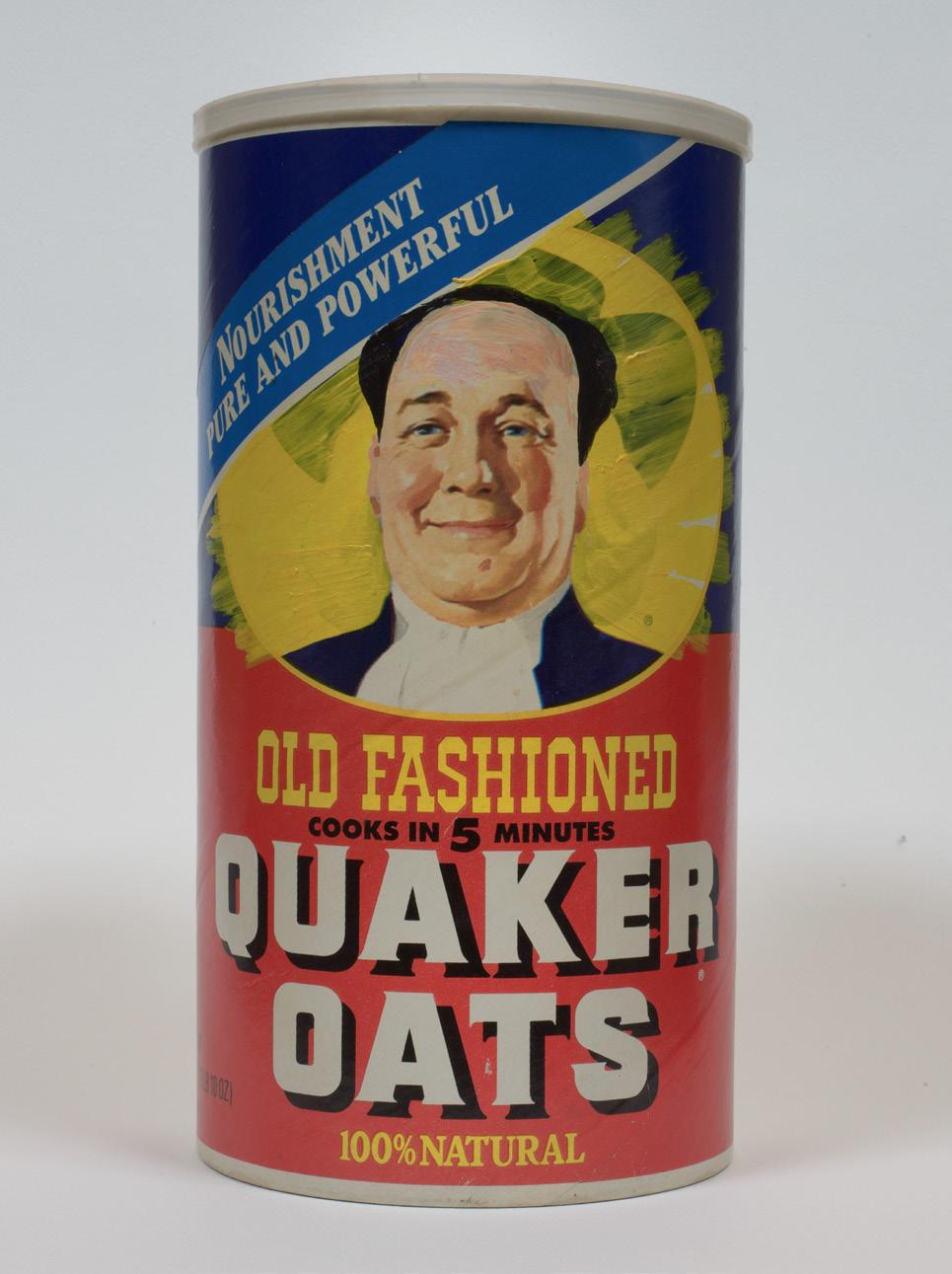

Zhang Hongtu

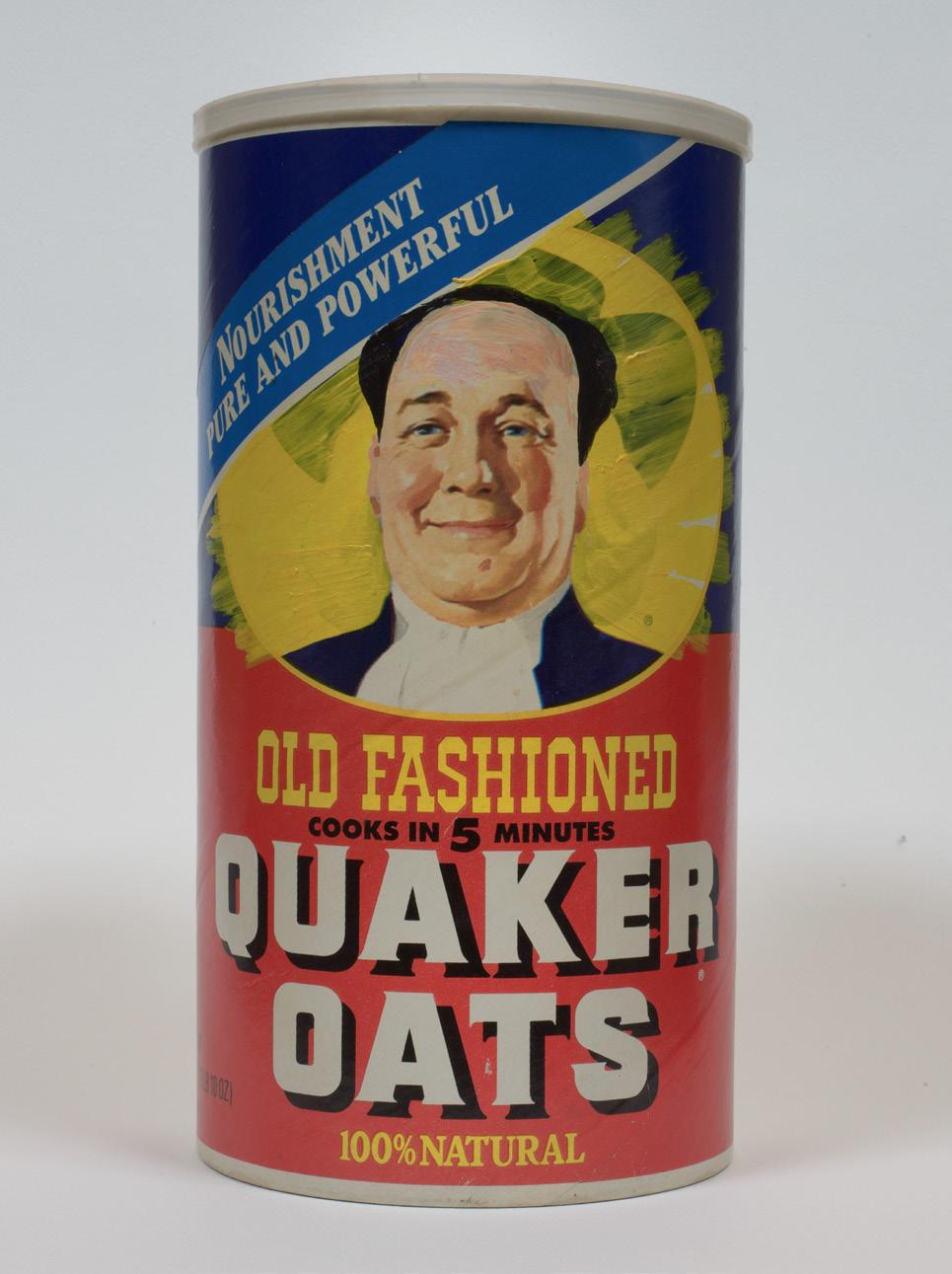

Quaker Oats Mao #2 1989

Acrylic on Quaker Oats box Courtesy of the artist and Jennifer Baahng Gallery

Zhang Hongtu lived through both the Chinese Civil War and the Cultural Revolution. As a young man, he embraced Mao’s teachings but later grew deeply disenchanted with the Chinese government and its censorship. After moving to New York in 1982, Zhang embarked on a series of satirical works that examined the power of imagery and Mao’s cult of personality, as well as their psychological effects—once one starts looking, it is possible to see Mao everywhere. As part of his “Long Live Chairman Mao” series, Zhang painted over the Puritan farmer on the Quaker Oats canister to make him resemble Mao. By conflating the image of the Quaker Oats mascot and the Chairman, Zhang’s work humorously explores the intersection of ideology, propaganda, and advertising.

Li Shan Untitled 2006

Acrylic and collage on canvas Courtesy of Opera Gallery

This painting is based on a famous propaganda portrait of the young Mao, taken at the end of the Long March (1934-1935)—a photograph heavily edited so that Mao, who originally looked haggard and tired, appeared fresh-faced and vigorous. Li himself grew up during the Cultural Revolution, and like other artists who came of age during the movement, had painted numerous portraits of the Chairman in his youth. His painting takes the conventions and practices of propaganda to an extreme; he has manipulated Mao’s face, giving it a highly sensual quality and adding floral motifs to his costume. By feminizing and eroticizing the image of the Chairman, Li ironically subverts the iconic portrait and renders Mao as an object of both desire and idolatry.

4

4

Hung Liu Light Source Study 2013 Mixed media Courtesy of Turner Carroll Gallery

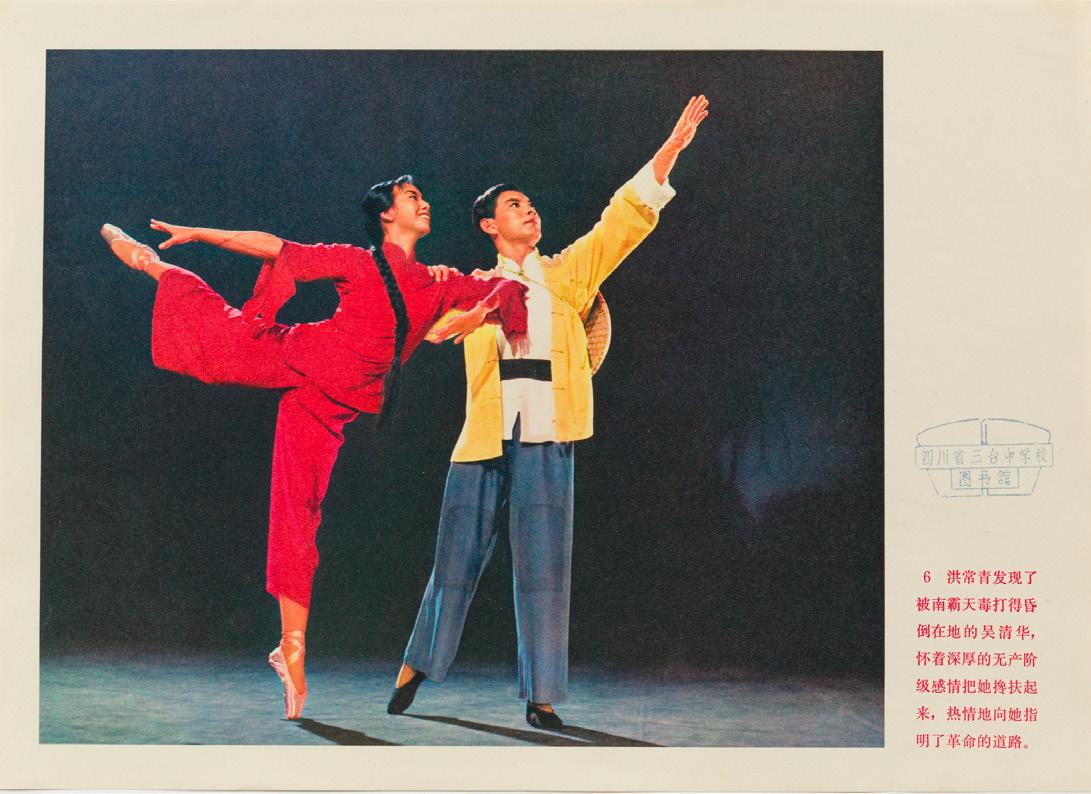

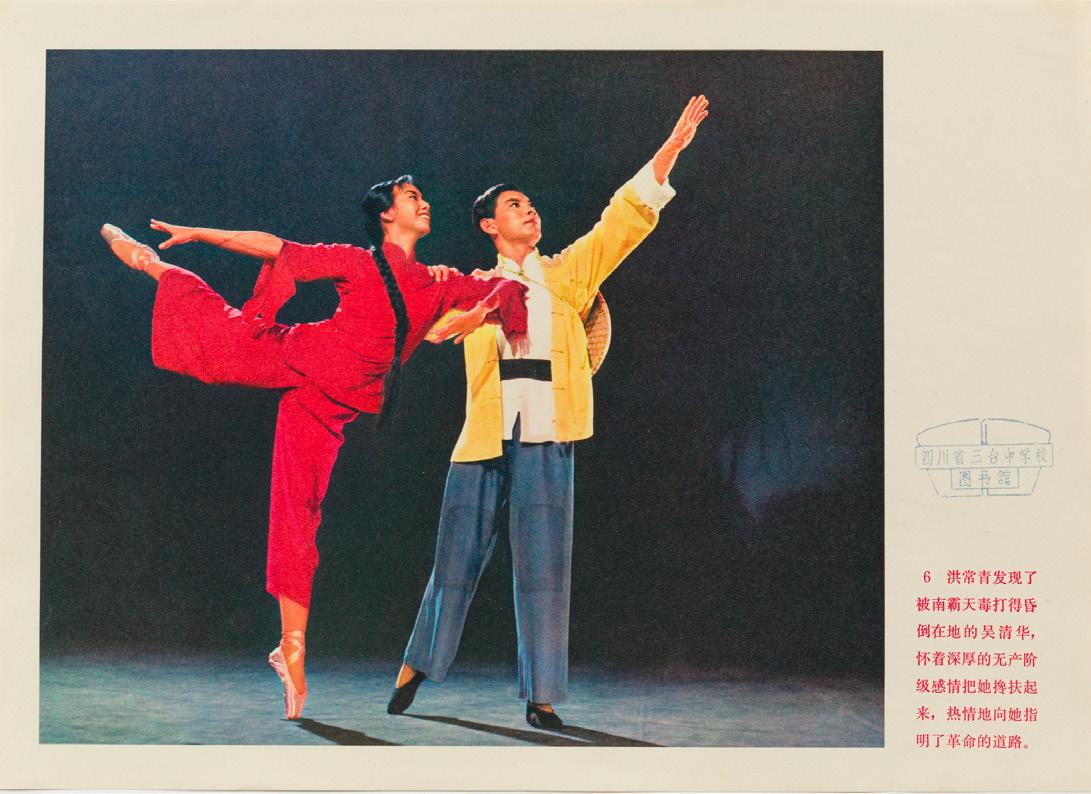

Hung Liu’s Light Source Study takes a film still from the Cultural Revolution-era model ballet, The Red Detachment of Women. Her work playfully comments on Maoist art theory for both the visual and performing arts, which decreed that all good characters had to be portrayed as “red, bright, and shining,” and maintained strict control over composition, staging, and lighting. The work is divided into two halves: the right side, where the characters stand against a dark background, and the left, which is brightly painted with gold leaf. The characters turn toward a sun in the upper left corner, which symbolizes Chairman Mao, who was called the “sun in the hearts of the Chinese people,” but also a citrus known as a Buddha’s hand that symbolizes good fortune and was often left as an offering at temples. The source of light in this work is unclear–are the characters illuminated by the sun, representing Mao and his teachings, or by the Buddha’s hand?

Li Tianbing In Front of the Propaganda 2011 Oil on canvas Courtesy of Opera Gallery

This work, made by manipulating photography with oil paint, features small children sitting in front of a large wall covered in propaganda slogans, the “Three Represents” that defined the role of the Chinese Communist Party. Although these were created by President Jiang Zemin in the early 2000s, the nature of the propaganda clearly draws from examples from the Mao-era. Without access to cameras, children in Li’s time grew up lacking any documentation of their childhood. Paintings such as this often focus on Li’s childhood memories of growing up in China’s politically charged atmosphere and the long legacy of the Cultural Revolution.

5

5

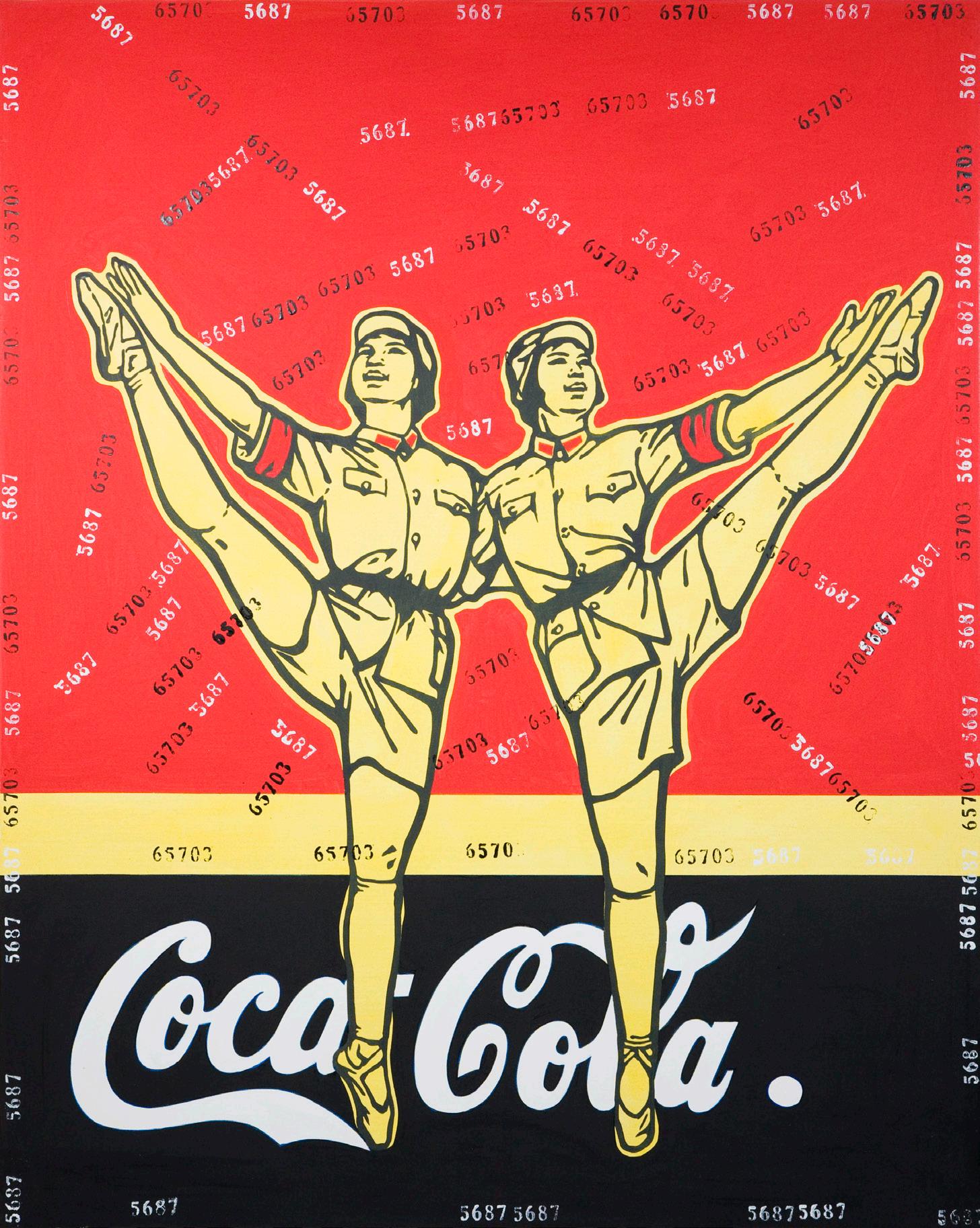

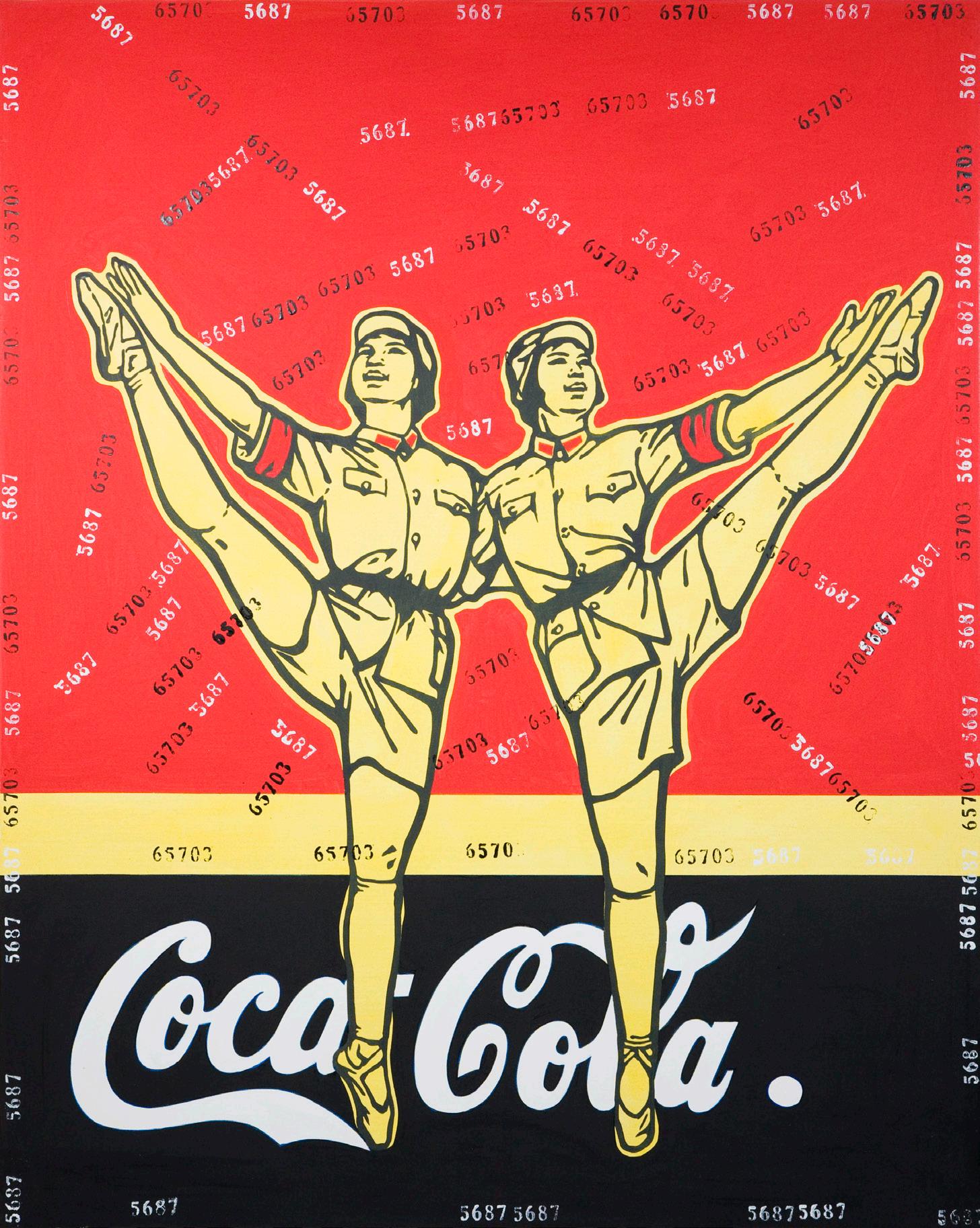

Wang Guangyi Great Criticism- Coca Cola 2005 Oil on canvas

Courtesy of Opera Gallery

Wang Guangyi’s paintings draw from the Pop Art aesthetic developed by Western artists such as Andy Warhol, while featuring the playful appropriation of Mao-era imagery. This particular example juxtaposes iconic figures from the Cultural Revolution-era model ballet, The Red Detachment of Women with the Coca-Cola logo, an international symbol of advertising, globalization, and consumption, while the numbers scattered across the canvas refer to Chinese barcodes. The meaning of Wang’s works, however, remains ambiguous: are they intended as a critique of socialist society or of capitalist consumer culture? Ultimately, his Great Criticism series ironically highlights the similarities between communist propaganda and capitalist advertising.

6

6

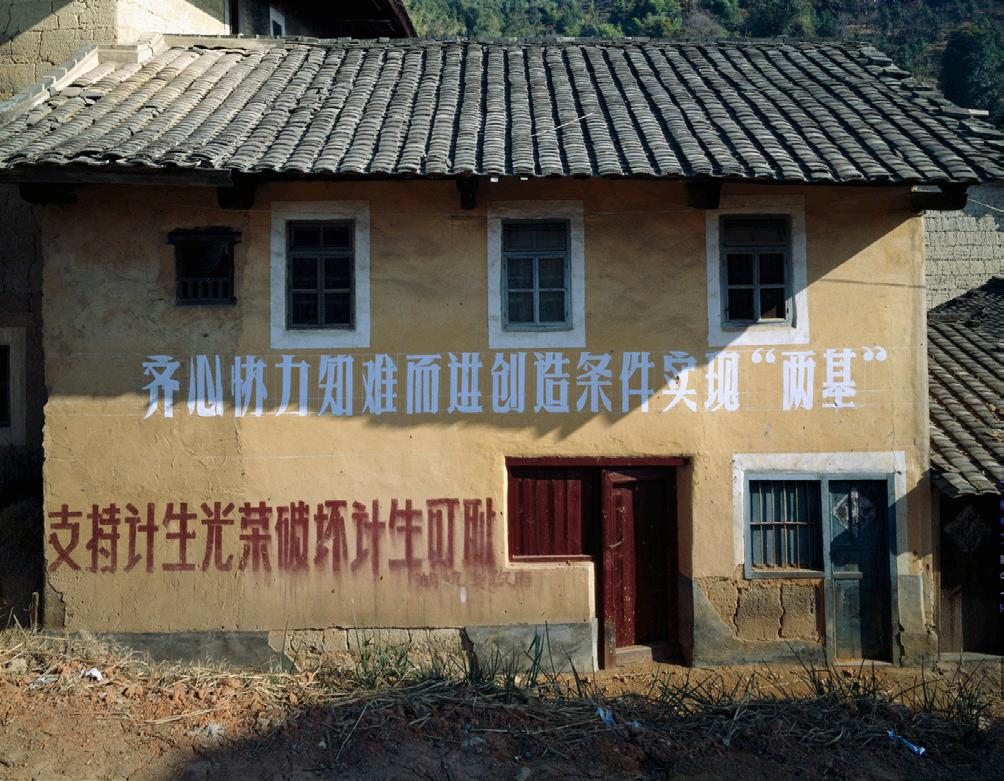

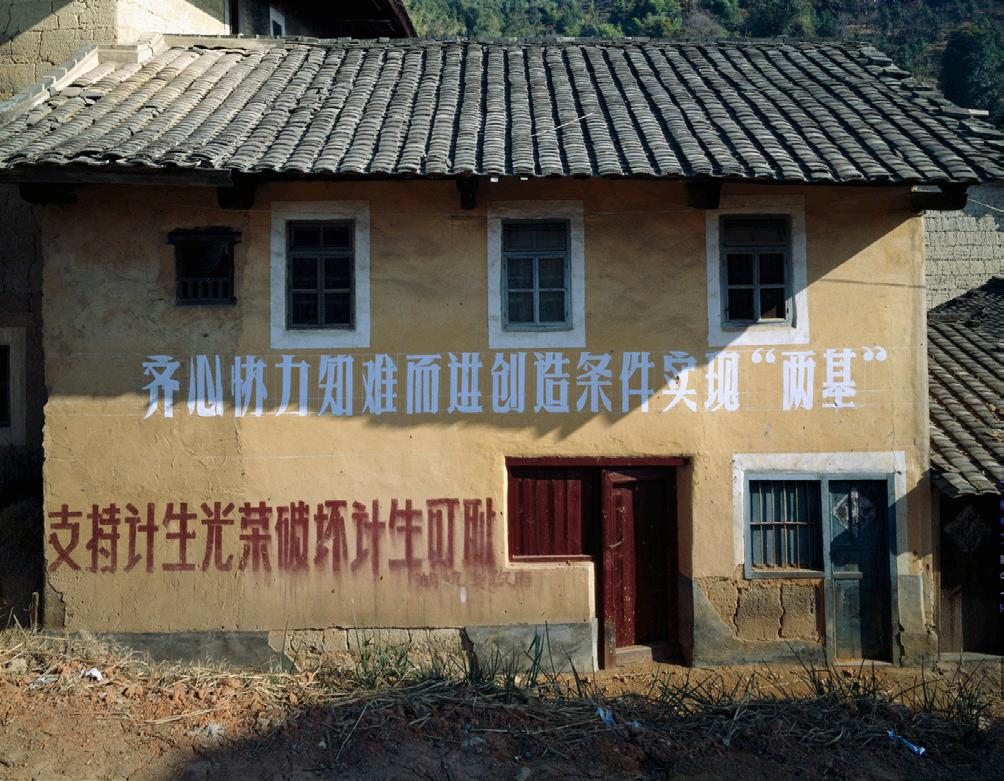

Elizabeth Gill Lui

Buildings with Mao-era Slogans 1997

Chromogenic print Courtesy of the USC Pacific Asia Museum

Elizabeth Gill Lui Home Altar Honoring Chairman Mao 2006

Chromogenic print Courtesy of the USC Pacific Asia Museum

Elizabeth Gill Lui’s two images capture the lasting legacy of the Cultural Revolution in China. The crumbling house in the Anhui province features government slogans that promote Chinese Communist Party policy from the 1980s, but are similar in rhetoric and appearance to those from the Mao-era. The top one urges viewers to “make concerted efforts to overcome difficulties and create conditions to realize the ‘two basics,’” which include universal enrollment among school-aged children and full literacy among those under the age of 20. The second slogan, painted in red, announces that “supporting family planning is glorious, destroying family planning is shameful.” Although much of China has modernized and globalized, this photograph captures the remnants of a former China.

The home altar with the brightly colored poster of the Chairman highlights the transformation of Cultural Revolution imagery in the 1990s. Disillusioned with the current government under Deng Xiaoping, citizens nostalgically looked back to Maoist rule as a period of greater social equality. In particular, the figure of Mao was transformed into a beneficent folk deity, such as the Kitchen God. Chinese citizens began to post his image not out of political respect, but to invoke good luck, wealth, and protection.

7

7

Many traditional portraits of Mao show him raising his right hand in a symbol of salute. Sui Jianguo’s sculpture deconstructs this iconic pose, featuring only the monumental right hand of the Chairman. However, the arm is disembodied and lifeless, removed from its original symbolic meaning. As Sui grew up during the Cultural Revolution under the shadow of Mao, Right Arm, plays on the artist’s personal memories, as well as the transformation of the Chairman’s status after his death. Several of Sui Jianguo’s works explore China’s complex political history and the intersection of ideology and the individual through sculptures featuring the body of Mao and his iconic, eponymous Mao Suit.

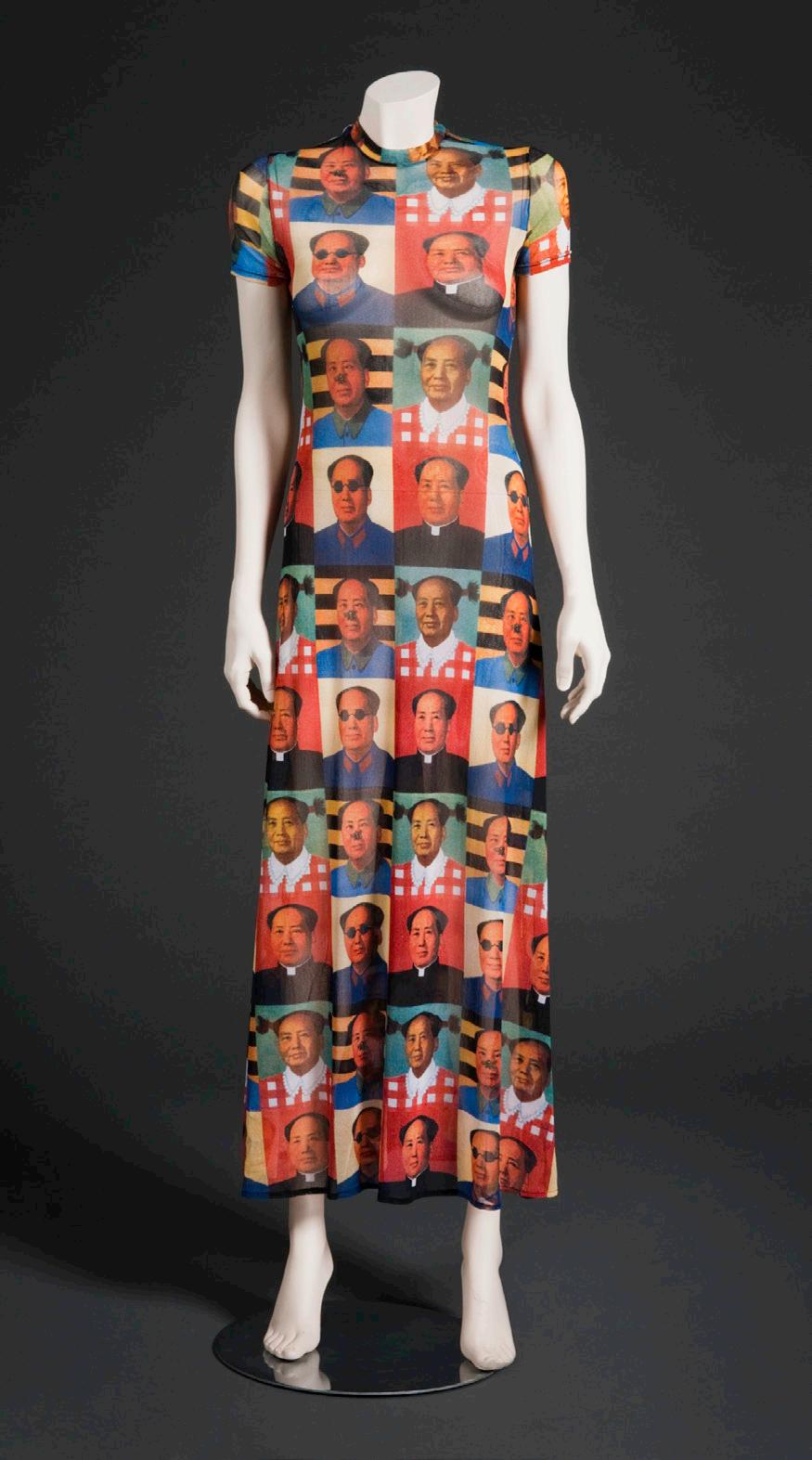

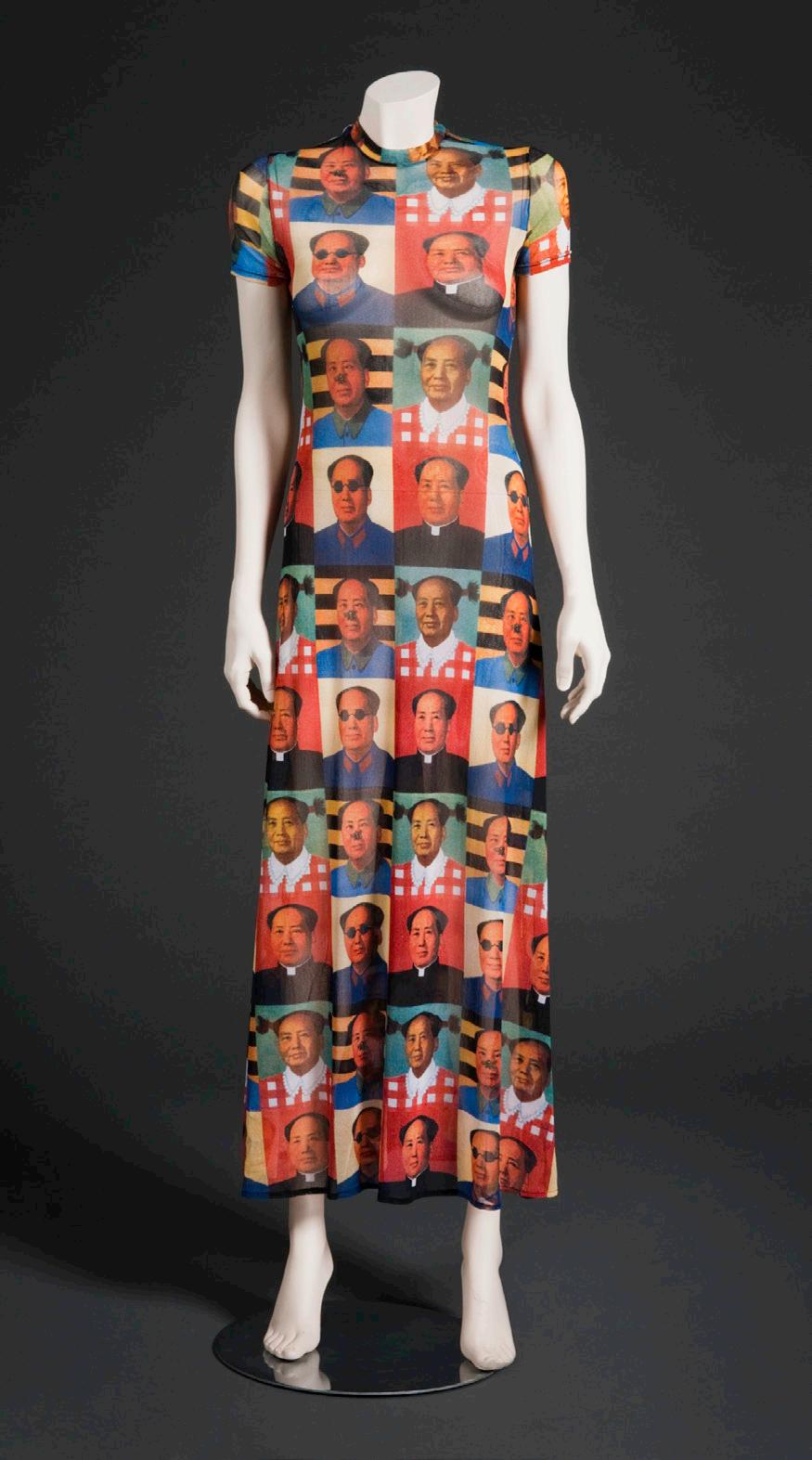

Vivienne Tam and Zhang Hongtu Mao Dress 1995 Nylon

Courtesy of FIDM Museum at the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising

This playful dress is a collaboration between the Hong Kong-based fashion designer Vivienne Tam and the artist Zhang Hongtu, whose work Quaker Oats Mao #2 is also featured in the exhibition. The dress appropriates the ubiquitous and iconic portrait of the Chairman, showing him in various humorous or satirical guises, such as “Mao so Young,” in pigtails and a gingham dress; “Ow Mao,” with a bee on his nose; “Holy Mao,” in the costume of a cleric; “Psycho Mao,” wearing dark glasses; “Miss Mao,” with lipstick; and “Nice day Mao,” where he is smiling. The portraits are arranged in a checkerboard pattern in order to reflect the changeable character of the Chairman. Although Mao fought against Western capitalism, by the 1990s, his image had become widely commodified, used to decorate a variety of goods including high fashion clothing.

8

Sui Jianguo

Right Arm 2003 Bronze Courtesy of James Kenyon and L.A. Louver

8

A Second History

prints

9

9

Zhang Dali

2022 Aluminum dibond artist

Courtesy of the artist and Ethan Cohen Gallery

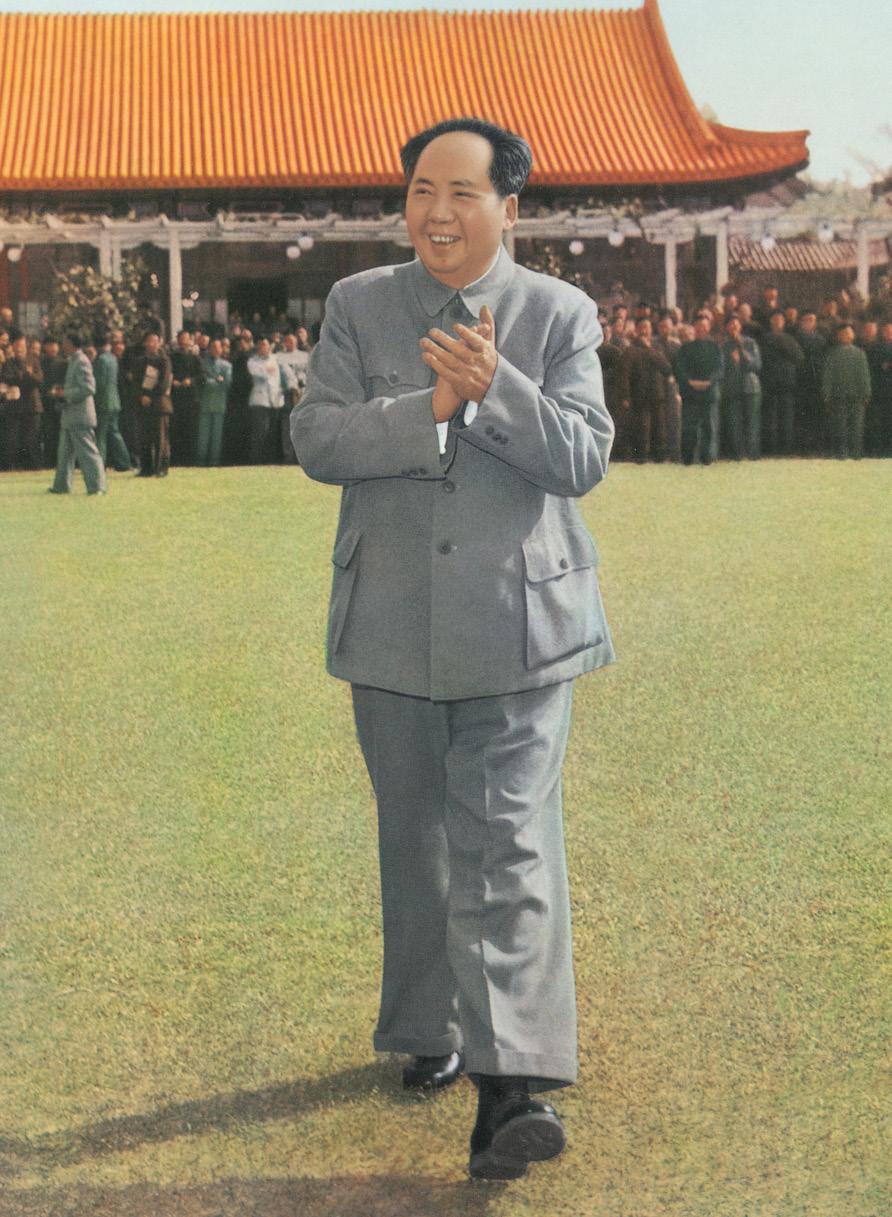

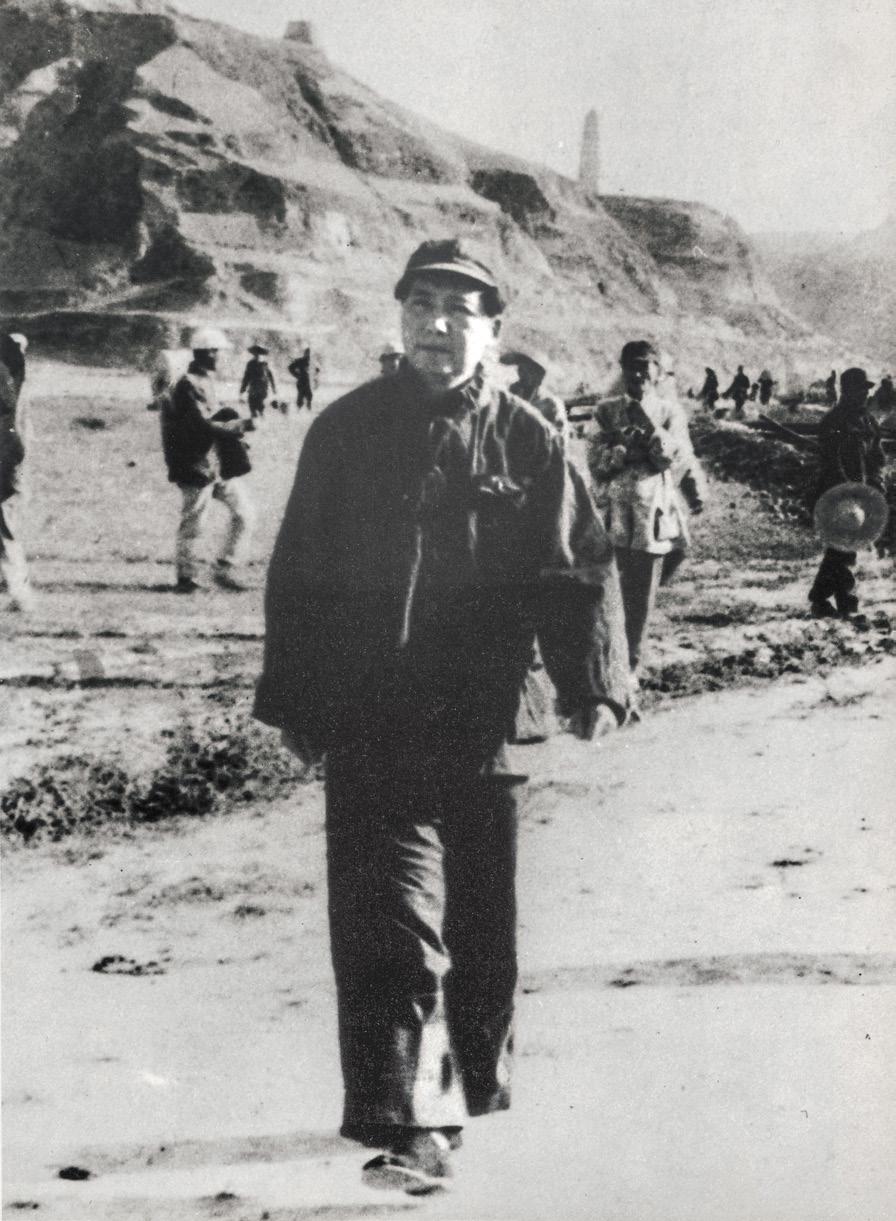

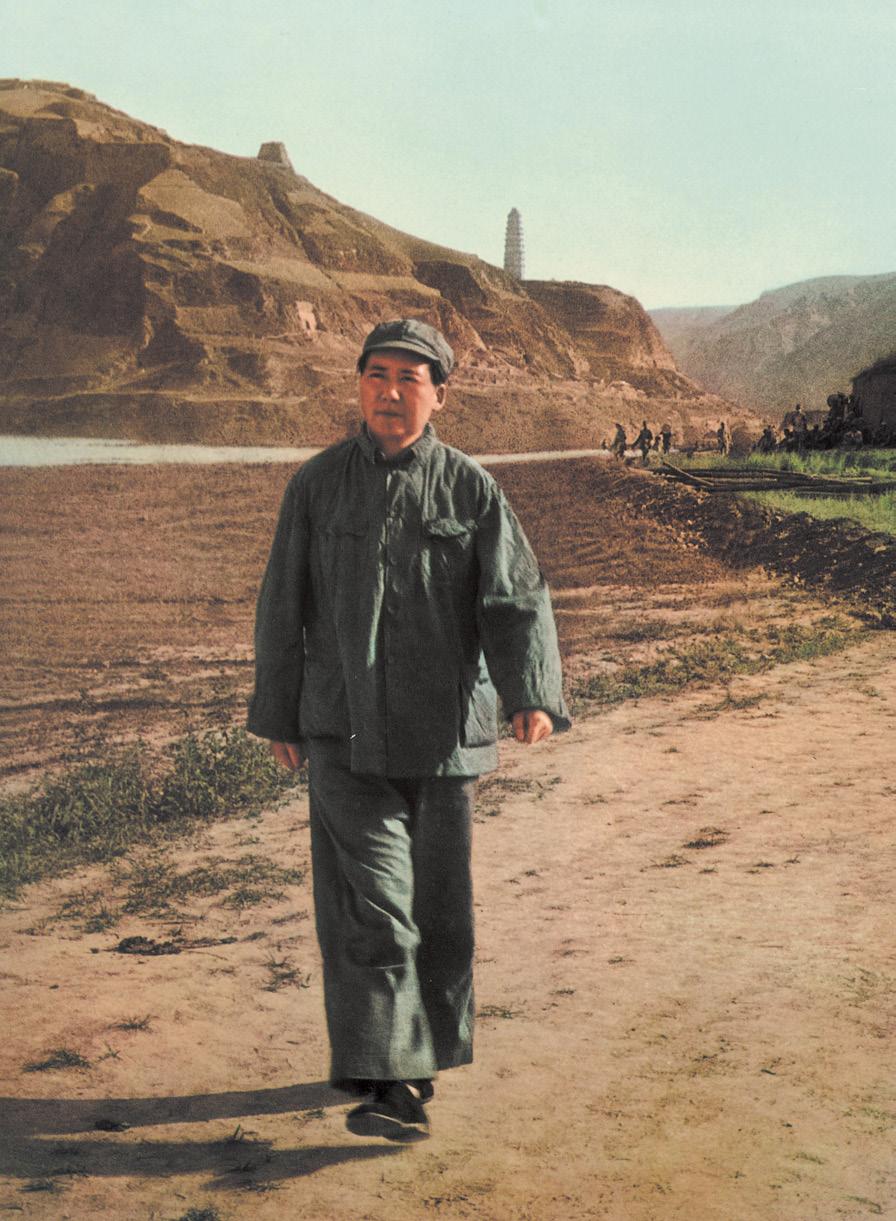

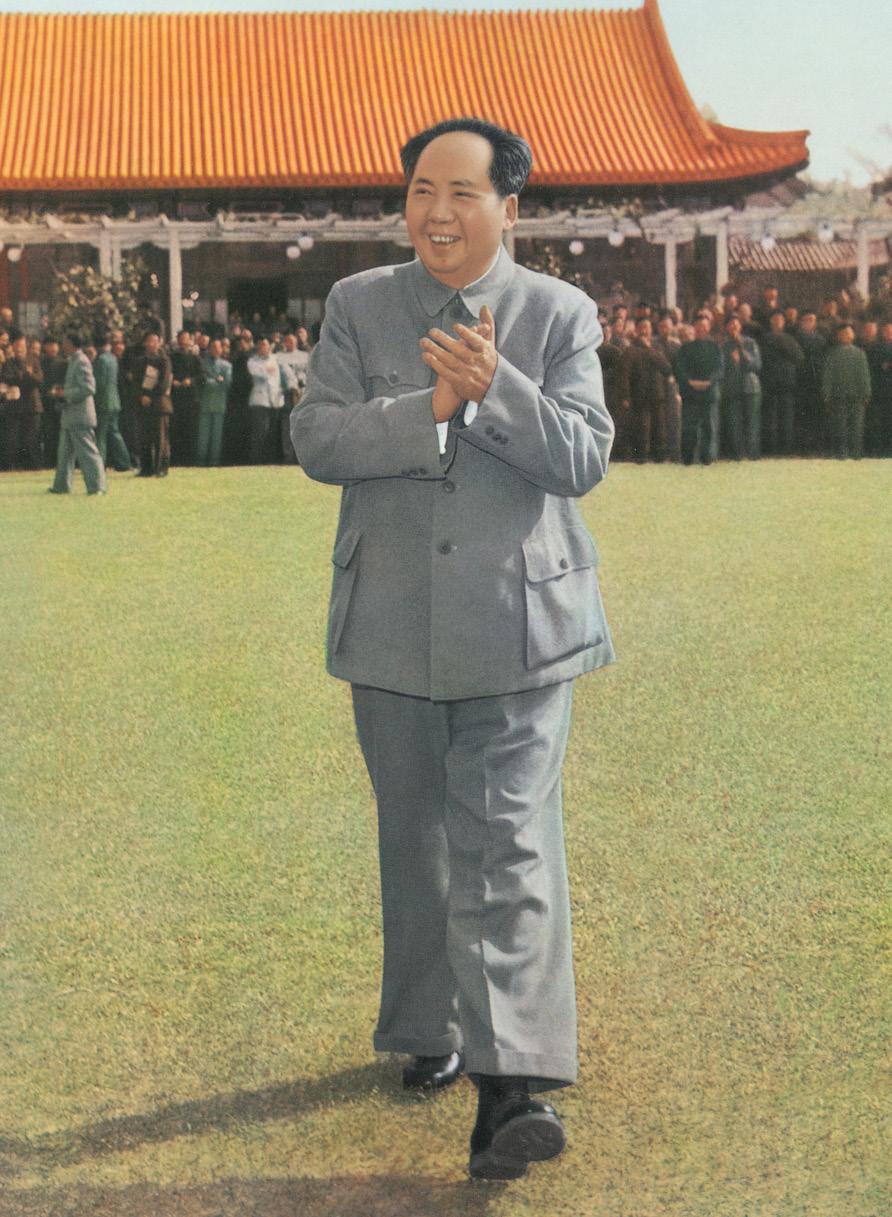

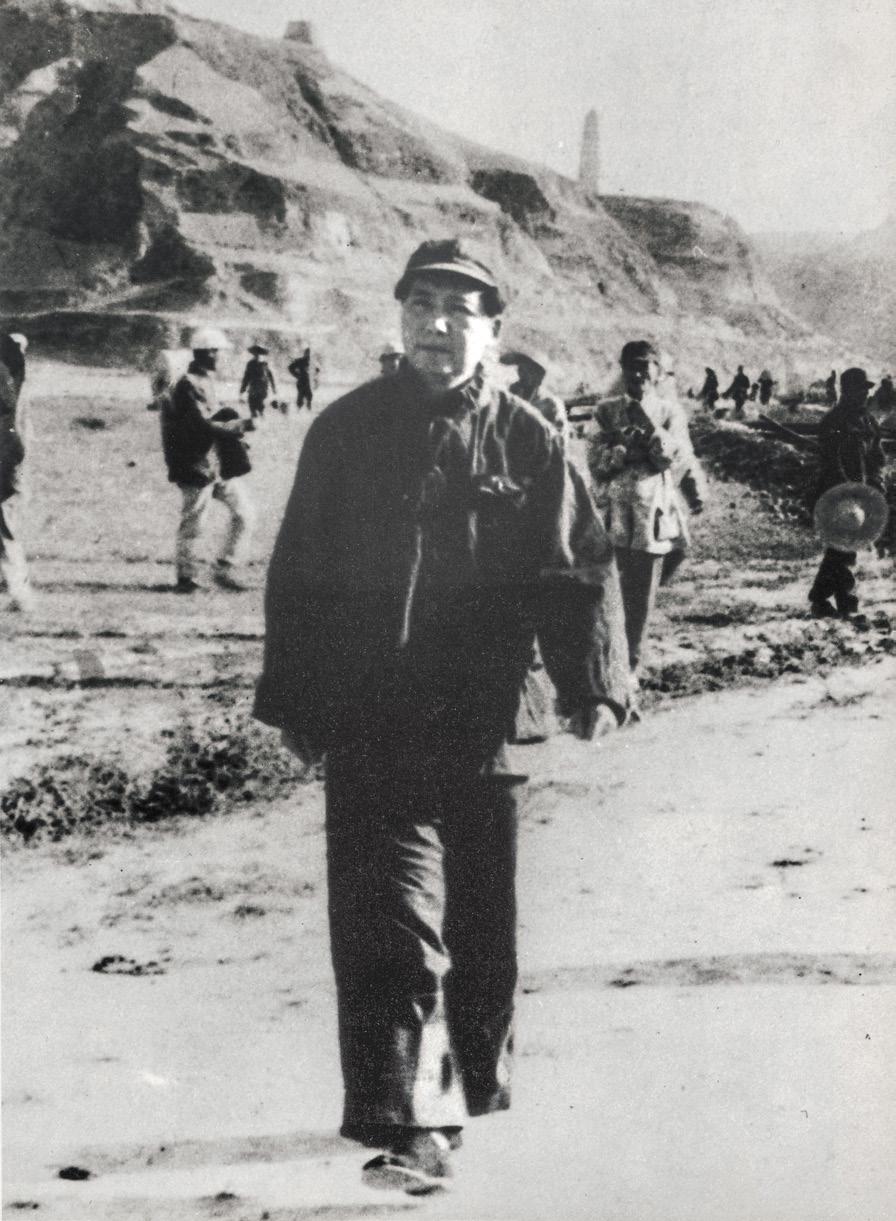

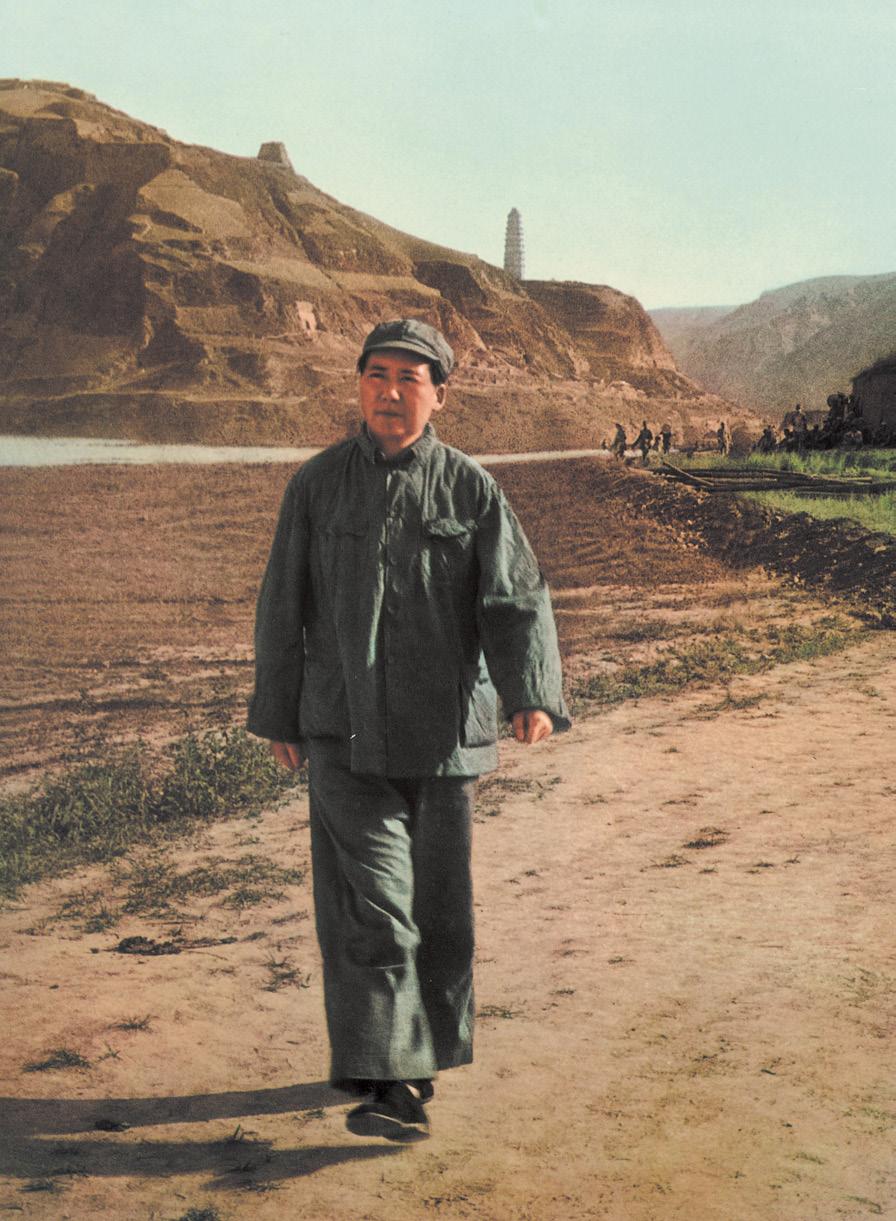

This set of four diptychs are taken from Zhang Dali’s photo series A Second History, which examines the Maoist propaganda images—especially photos of the Chairman— the artist grew up with in the 1960s and 70s. Over the course of seven years, Zhang researched state publication archives to look for negatives and collected thousands of publications dating from the 1950s to the 1980s to create this series. Juxtaposing the edited and unedited versions, his diptychs explore the widespread manipulation of photographs by the Chinese Communist Party to not only create images that fit with Mao’s artistic vision and political guidelines, but in some cases, to rewrite history.

10

10

THE CULT OF THE CHAIRMAN

As the founder of the People’s Republic of China and uncontested leader of the nation, Mao was constantly praised and quoted in newspapers, books, magazines, and even comics. Chinese citizens were not only expected to study the Chairman’s teachings from The Little Red Book, but also perform songs and dances dedicated to him. Men, women, and children wore Mao badges and dressed themselves in Mao suits in emulation. His image was everywhere—from posters to plates—while portrait sculptures, as busts or as full figures, allowed for the Chairman’s embodied presence in homes, institutions, factories, and public spaces. Ironically, Mao himself had initially warned against personality cults, but by the Cultural Revolution, he had realized its necessity to carry out his political agenda.

After the Chairman’s death, party leadership sought to suppress the cult. The Cultural Revolution was denounced as a mistake, and officials declared that Mao’s policies had been “70% right and 30% wrong.” But in spite of this pronouncement, the Chinese Communist Party still tolerates little criticism of the Chairman, especially since Mao and his legacy remains central to Party ideology to this day. In any case, the Chairman continues to be revered for his role liberating the country and establishing the modern Chinese nation.

The various objects in this section were made to celebrate or document the Chairman’s accomplishments, but more importantly, they illustrate the cult of Mao as a lived, multi-sensory experience that permeated the daily lives of Chinese citizens during the Cultural Revolution.

11

11

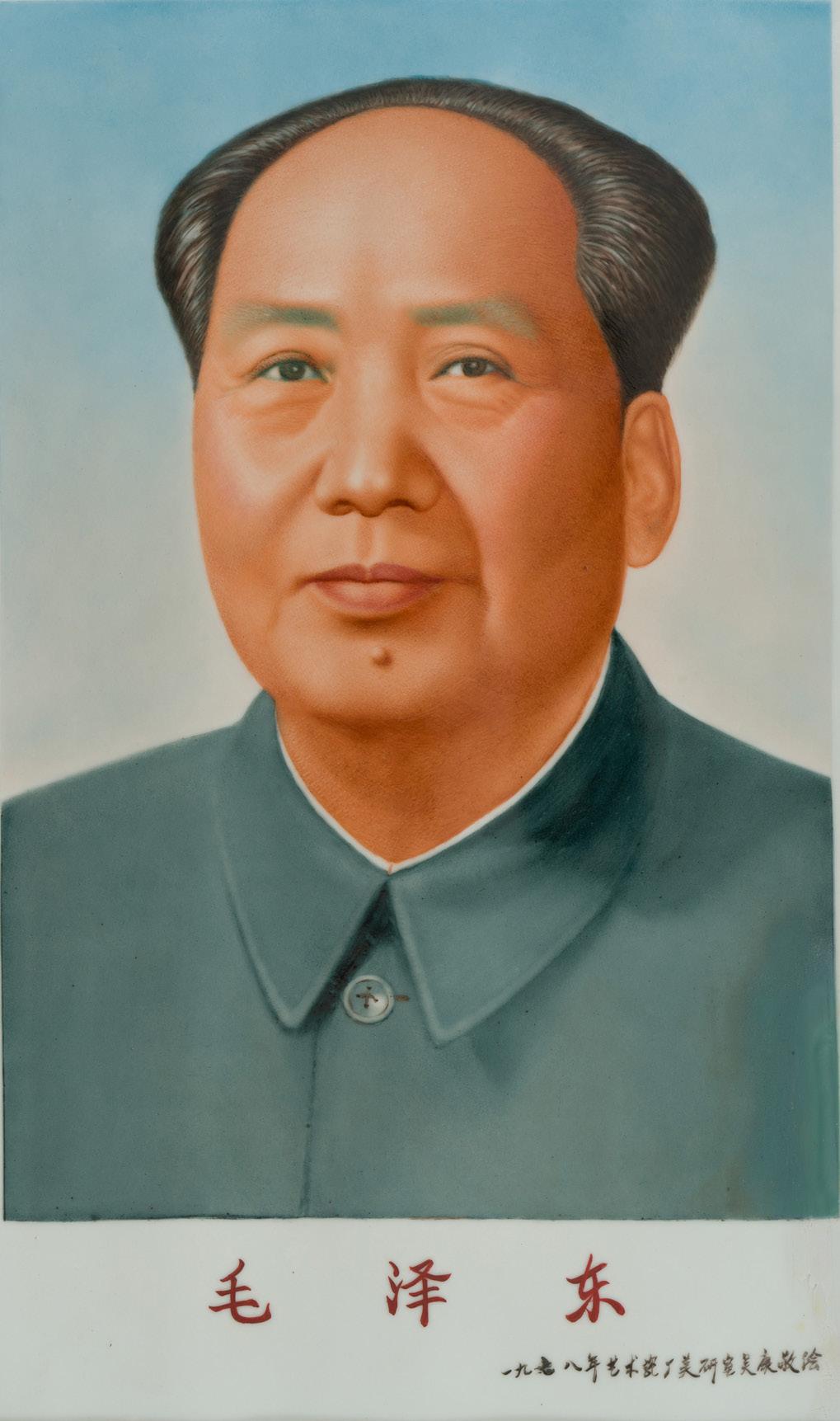

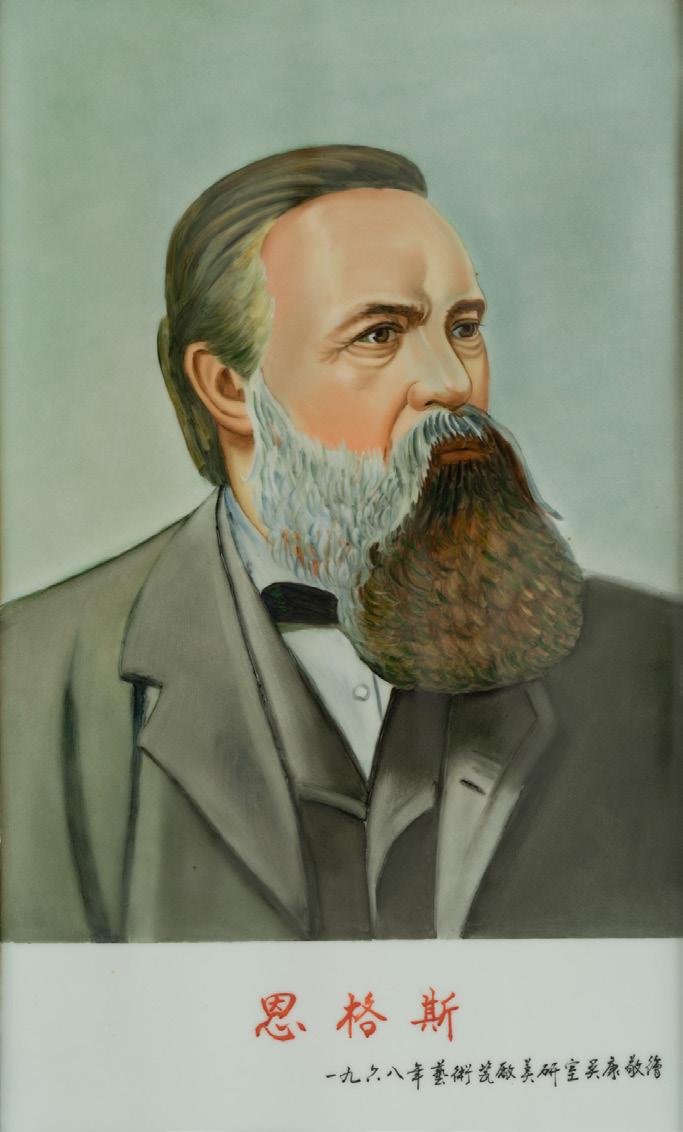

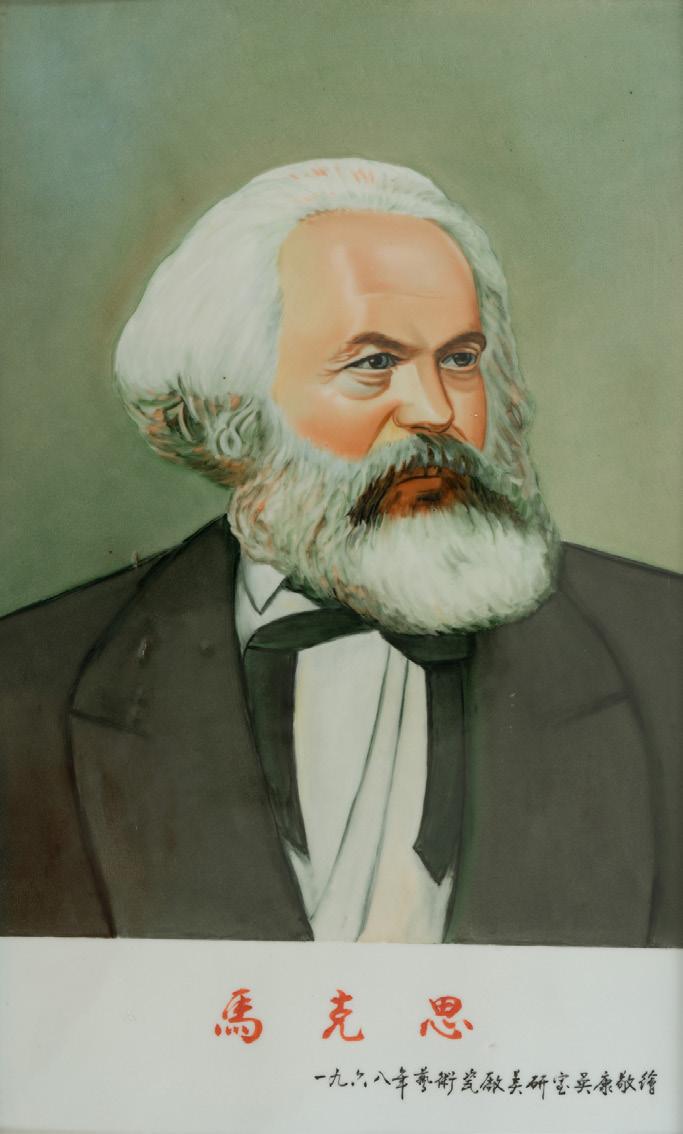

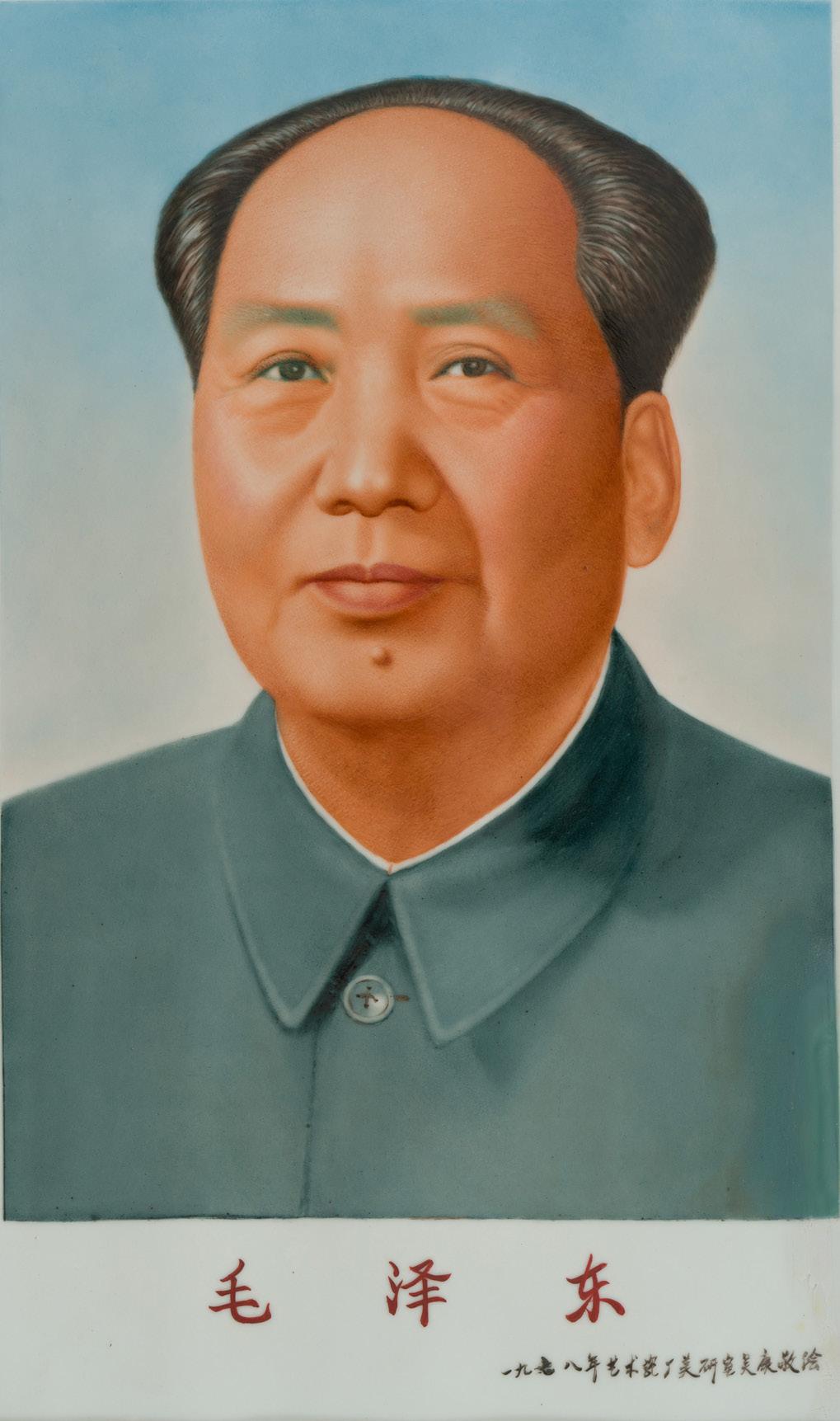

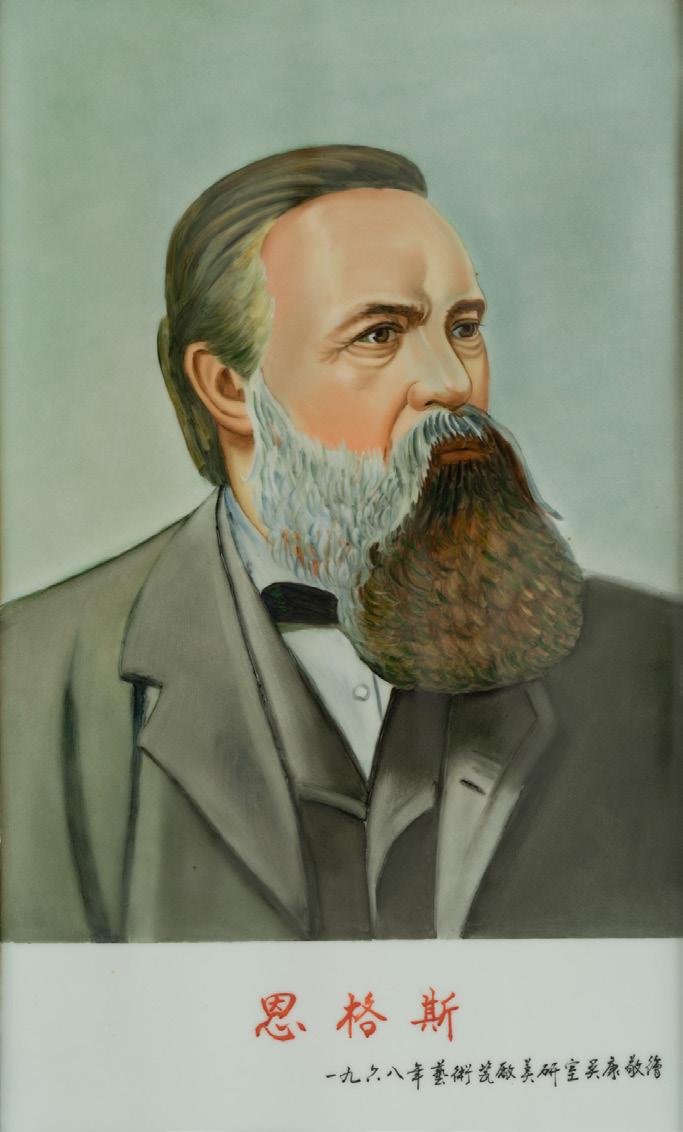

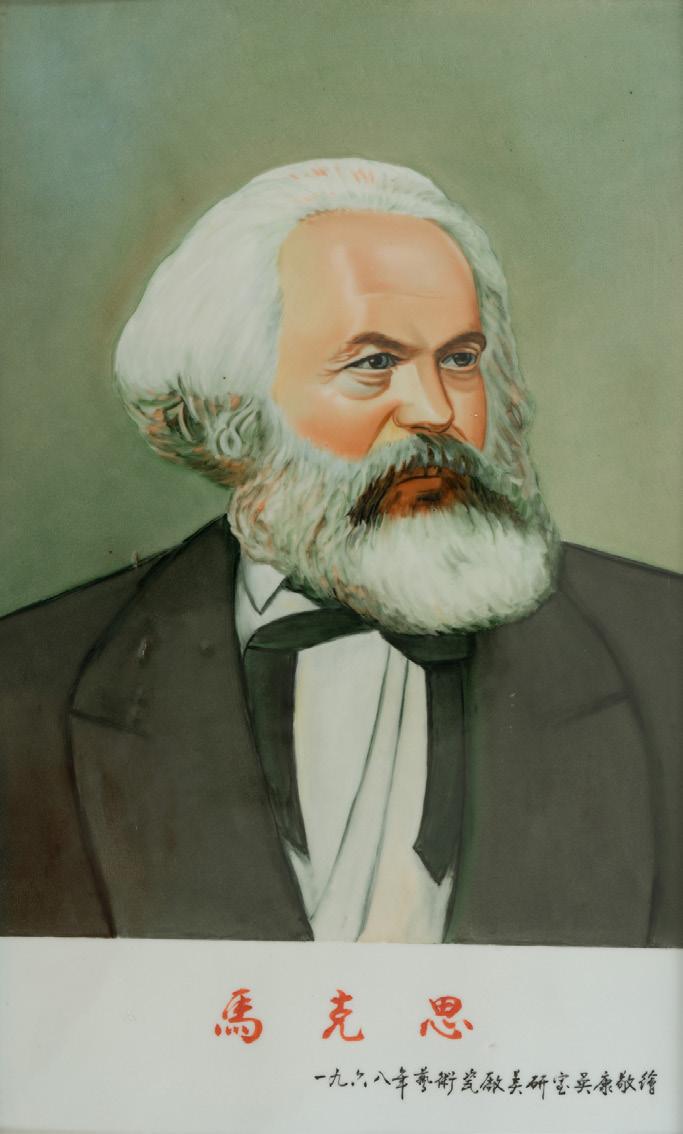

Wu Kang 吴康

Mao and Communist Leaders 毛主席和共产领袖

1966-1976 Porcelain Private Collection

During the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s portrait was often featured alongside the most important Socialist figures—the founders of Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and the Soviet leaders, Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin. After the failure of the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962), a campaign to industrialize the nation and to collectivize farming that resulted in mass famine and the death of millions of Chinese citizens, Mao worried about his political standing. He sought to ensure that after his death, he would be remembered as a leading socialist revolutionary and a major figure within the communist pantheon.

Mao Badges

毛主席像章

1960s-70s

Metal and plastic Collection Wende, donated by David E. James

Pins and badges with an image of the Chairman were ubiquitous throughout the People’s Republic of China; wearing one was a sign of one’s loyalty to the party and the revolution. Often featuring a red and white color scheme, these aluminum pins show Mao’s portrait against various backgrounds such as Tiananmen Square, flags, ships, plum blossoms, or sunflowers, which referre to various historical events, honorific titles for Mao, or quotations by the Chairman. Ironically, Mao badges were also often exchanged as a form of currency on the black market—the larger and rarer the badge, the more it was worth.

12

12

Bust of Mao 毛主席头像

1966-1976

Porcelain Private Collection

During the Cultural Revolution, images of the Chairman—in the form of posters, photographs, or in this case, ceramic busts—were ubiquitous. Portraits such as these would have been placed in prominent locations in homes, factories, and schools and demonstrated the owner’s devotion to the Chairman.

Woodblock of Mao’s Portrait 毛主席木板

1966-1976

Wood Private Collection

During the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s portrait was constantly reproduced across all media. Woodblock was one of the many ways Chinese citizens could quickly and easily replicate his image, either on paper to create posters, or on textiles to make flags and banners. Several examples of this distinctive portrait, with the Chairman depicted in profile and wearing the People’s Liberation Army uniform, can be seen in the posters and banners in this section and in the next, Ideology and Iconoclasm.

13

Jingdezhen Art Porcelain Factory 景德镇艺术瓷厂

13

Li Zhensheng

李振盛

Commemorating Mao’s Swim in the Yangzi 纪念毛主席游长江

1967

Inkjet print Private Collection

This photograph shows swimmers in the Songhua River, located in Northern China, holding aloft a large portrait of the Chairman, as well as signs wishing him good health and longevity. Mao first swam the Yangzi in 1956; however, in July of 1966, he went on another public swim to demonstrate his physical prowess at a time when Party members doubted his ability to lead the nation due to his advancing age and the failure of the Great Leap Forward. Mao’s swim in the Yangzi personified a man who was still strong, energetic, and ultimately capable of ruling China. Throughout his life, the Chairman promoted exercise and swimming as a way to build the physical strength required to be a good revolutionary; it was rumored that he swam in the Yangzi River 11 times between 1956 and 1962.

Jingdezhen

Sculpture Factory

景德镇雕塑瓷厂

Chairman Mao swims the Yangzi 毛主席游长江

1966-1976

Porcelain Private Collection

This sculpture commemorates the Chairman’s famous 1966 swim in the Yangzi River. Soon after the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, Mao appeared at an event in Wuhan celebrating the 10-year anniversary of his first swim in the river in 1956. Due to the failure of the Great Leap Forward and rumors of ailing health, many in the Chinese

Communist Party doubted Mao’s ability to continue ruling the nation. To quash these doubts, Mao publicly swam the Yangzi river yet again to demonstrate his physical strength, and thus, his capability to lead China. In this ceramic, Mao is dressed in a white bathrobe, ready to dive into the water. He is surrounded by children who will accompany him on his swim, as well as adoring citizens and People’s Liberation Army soldiers who play music to celebrate the occasion.

14

14

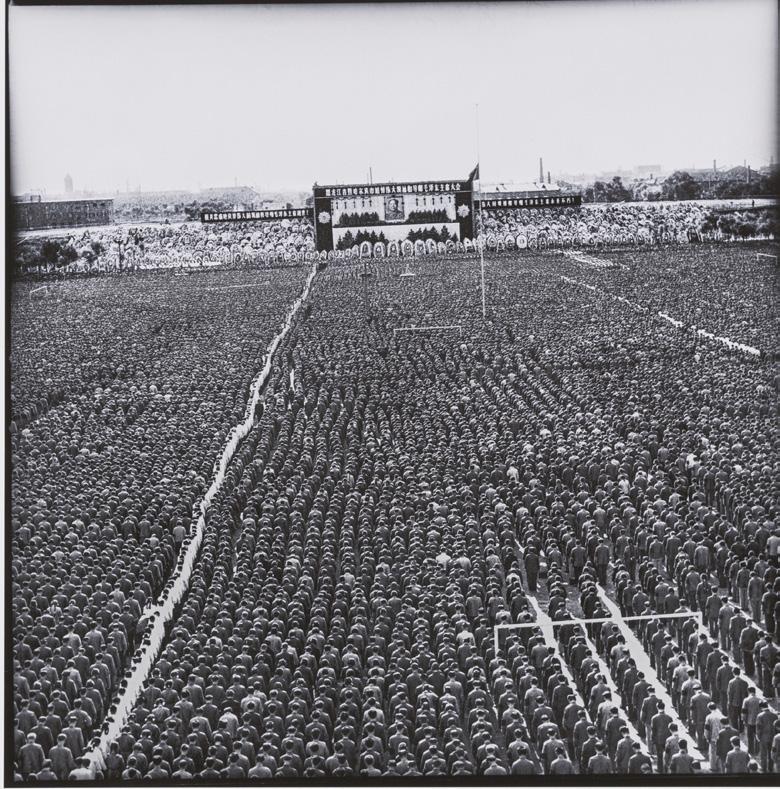

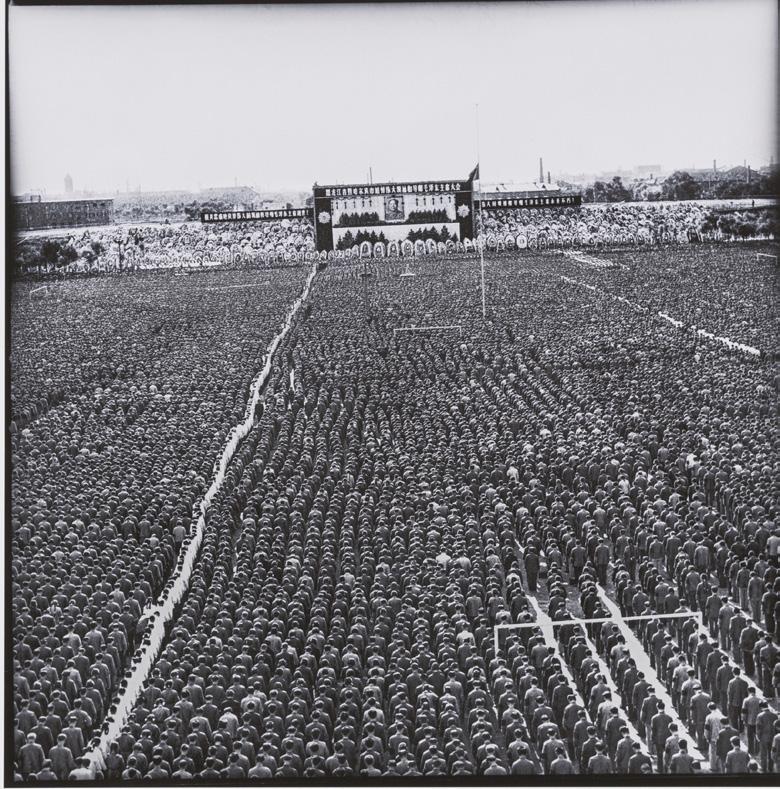

Li Zhensheng 李振盛

The Death of Chairman Mao 毛主席之逝世 1976 Inkjet print Private Collection

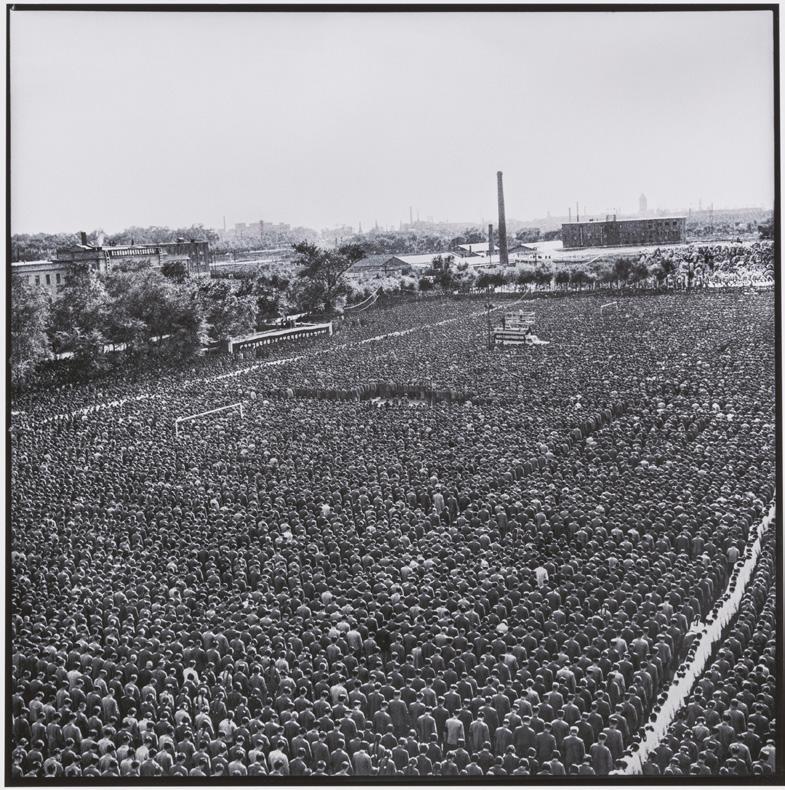

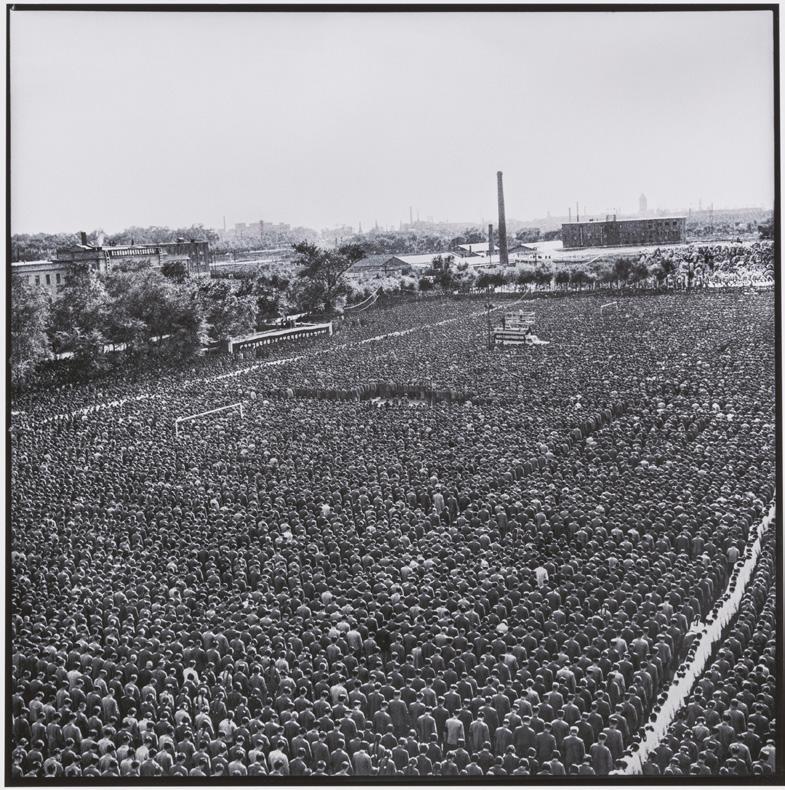

When Mao died on September 9, 1976, the nation immediately went into mass-mourning. Every citizen was expected to publicly mourn the death of the Chairman, regardless of their actual feelings. Li Zhensheng’s photograph depicts one of the official state funerals in Harbin, where hundreds of thousands gathered in the city’s People’s Stadium to mourn the Chairman on September 18. In Beijing, Mao’s body lay in state for a week in the Great Hall of the People, where over one million people paid their respects, before a public funeral in Tiananmen Square.

15

15

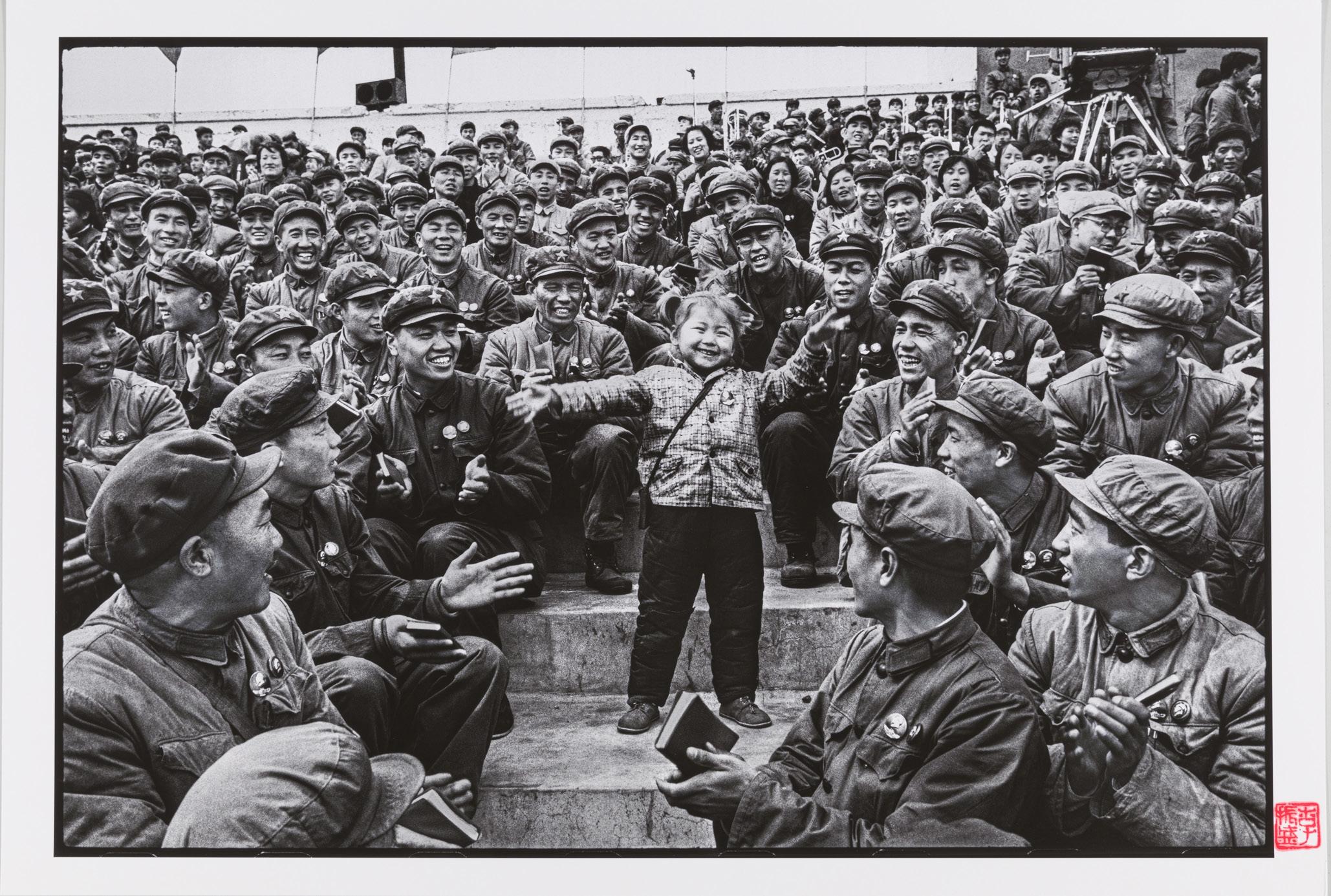

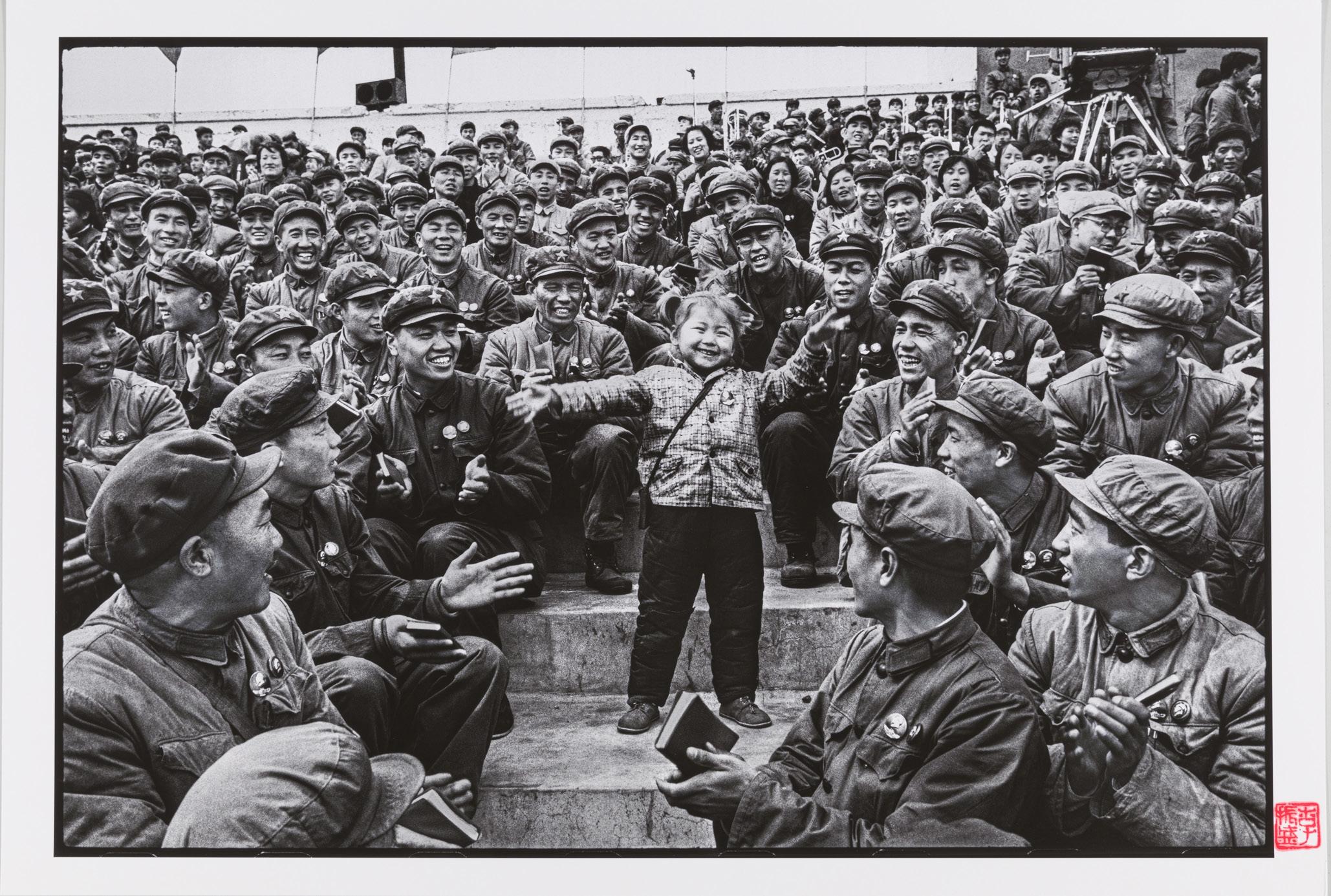

Li Zhensheng

李振盛

Kang Wenjie performing the Loyalty Dance 康文杰跳忠字舞 1968 Inkjet print Private Collection

Mao’s cult of personality reached its peak during the early years of the Cultural Revolution. Citizens both young and old were expected not only to study his writings and quote him, but also to perform a specific dance demonstrating loyalty and respect to the Chairman; this “loyalty dance” featured upward movements towards the sky in order to show the people’s admiration for him. This photograph by Li Zhensheng captures the smiling five-year-old Kang Wenjie performing the dance for thousands of attendees who gathered in Harbin’s Red Guard Square for a conference on Mao’s teachings.

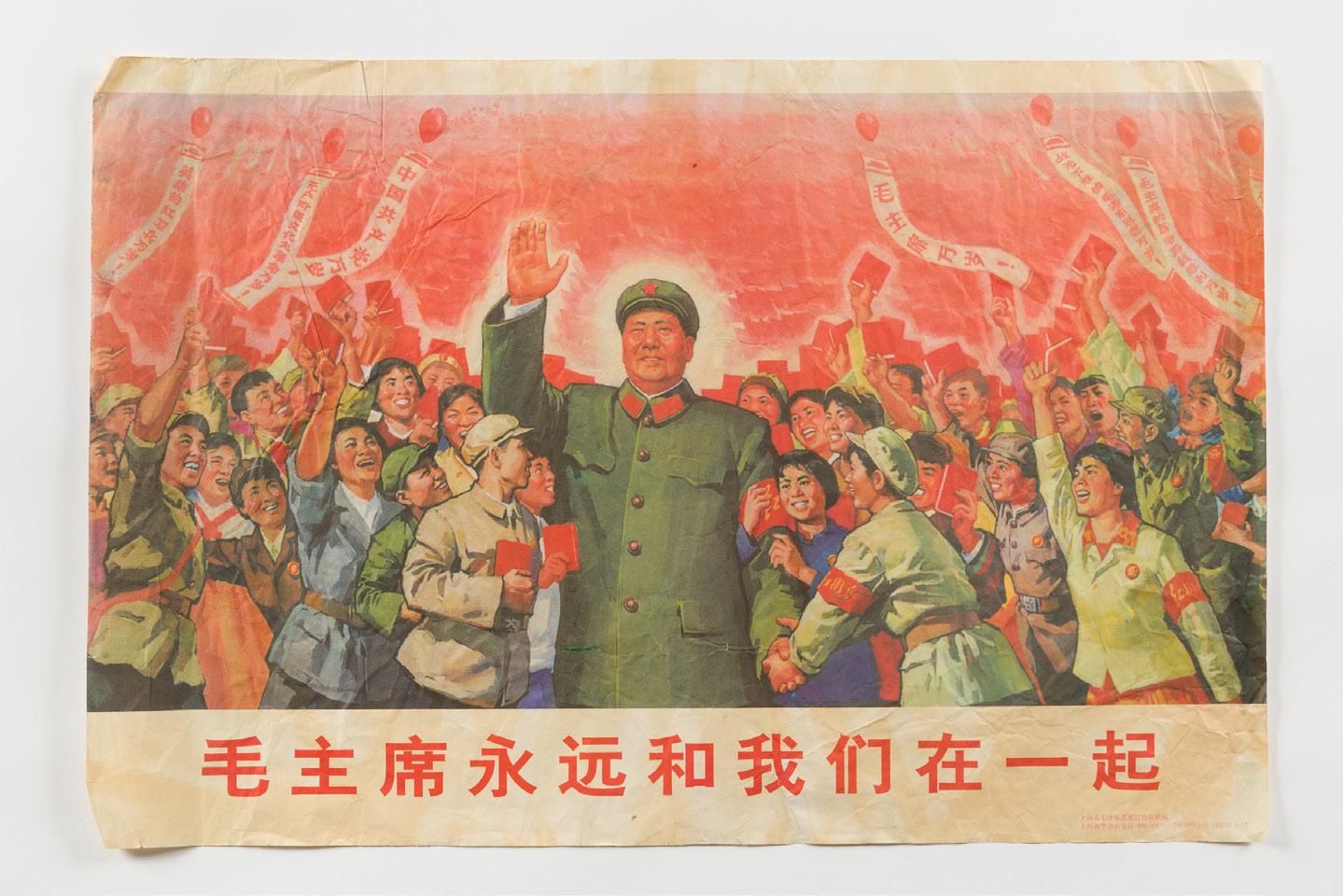

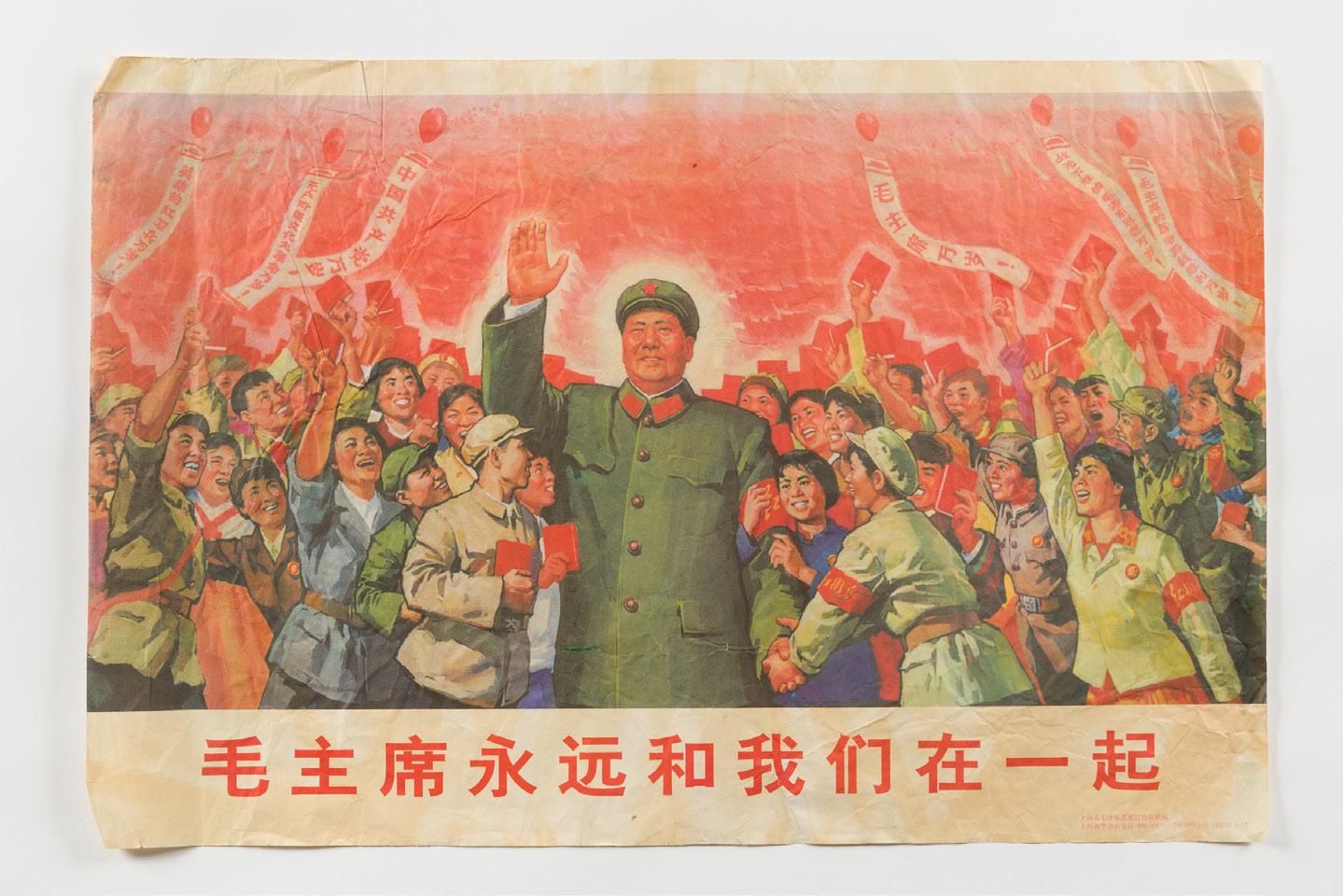

Shanghai Municipal Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Group 上海市毛主席思想宣传队

Chairman Mao will always be with Us 毛主席永远和我们在一起

1966-1976

Poster

Collection Wende Museum, donated by David E. James

The Chairman was often presented as the benevolent, much beloved father of the nation. In this poster, he is surrounded by young Red Guards and members of the People’s Liberation Army, who cheer and hold up Little Red Books. Streamers with balloons in the background wish him a long life and boundless longevity. Here, Mao is portrayed in a highly idealized fashion in accordance with government guidelines; he is the central figure—taller than all the others—and his face is “red, bright, and shining.”

16

16

1976 Porcelain Private Collection

Two men hold up portraits of Chairman Mao and Hua Guofeng, while a young child presents a bouquet as an offering. This sculpture celebrates Mao’s appointment of Hua as his immediate successor and the next chairman of the Chinese Communist Party. Hua was known for his loyalty to Mao—even changing his hairstyle to look more like him—and his adherence to the Chairman’s radical policies. However, he was an ineffectual leader and was soon ousted by other senior Party members just a couple of years after Mao’s death. Works such as this ceramic were made to reinforce Mao’s decision and to prepare citizens for the inevitable political transition.

Mao goes to Yan’an 毛泽东去延安 1966-1976

Porcelain Private Collection

This sculpture depicts the young Mao Zedong on the Long March, an arduous 6,000-mile trek carried out by the Communist Army (or Red Army) from October 1934 to October 1935. Due to encroaching hostile Nationalist forces, the Communist Party moved its base from Southeastern China to the remote desert city of Yan’an in the Northwest, which became the party’s headquarters until the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949. During the march, the Communists faced enormous casualties. The army began the march with approximately 86,000 troops and finally arrived in Yan’an with only 8,000. This work celebrates the heroism of the young Mao, who emerged from the Long March as the undisputed leader of the Party. Inscribed below is a quote from Mao’s poem, “The Long March,” which praises the fearlessness and determination of the army. The verse reads, “The Red Army fears not the trials of the Long March, holding light ten thousand crags and torrents.”

17

Celebrating Mao and Hua Guofeng 庆祝毛主席和华国锋

17

Jingdezhen

Art Porcelain Factory 景德镇艺术瓷厂

Yu Gong Moves the Mountain 愚公移山

1973

Porcelain Private Collection

This vase refers to an ancient Chinese fable titled “The Foolish Old Man Who Moved the Mountains,” (愚 公移山). An old man, Yu Gong, wanted to dig up two mountains that obstructed his path. Even though many people told him this task was impossible, he persisted, believing that his children and their descendants would eventually accomplish the task. The gods were moved by Yu Gong’s efforts and sent down two immortals, who carried away the mountains. This fable was later used by Mao in his 1945 speech at Yan’an, in which he spoke of the two big mountains that “lie like deadweight on the Chinese People”: imperialism and feudalism. Mao reinterpreted the Yu Gong fable as a collective call to action, inspiring the masses to persevere and work to create a new China.

18

18

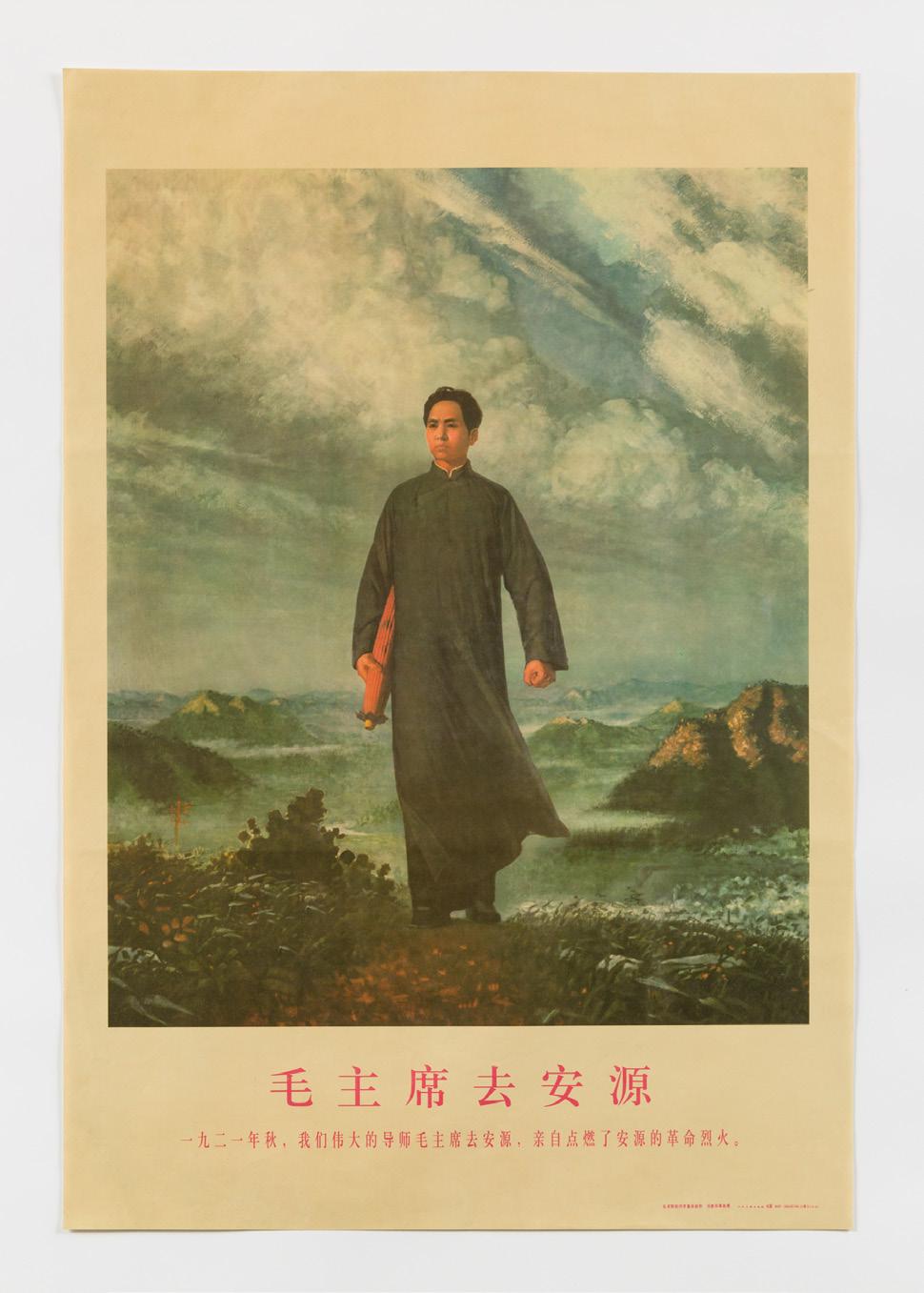

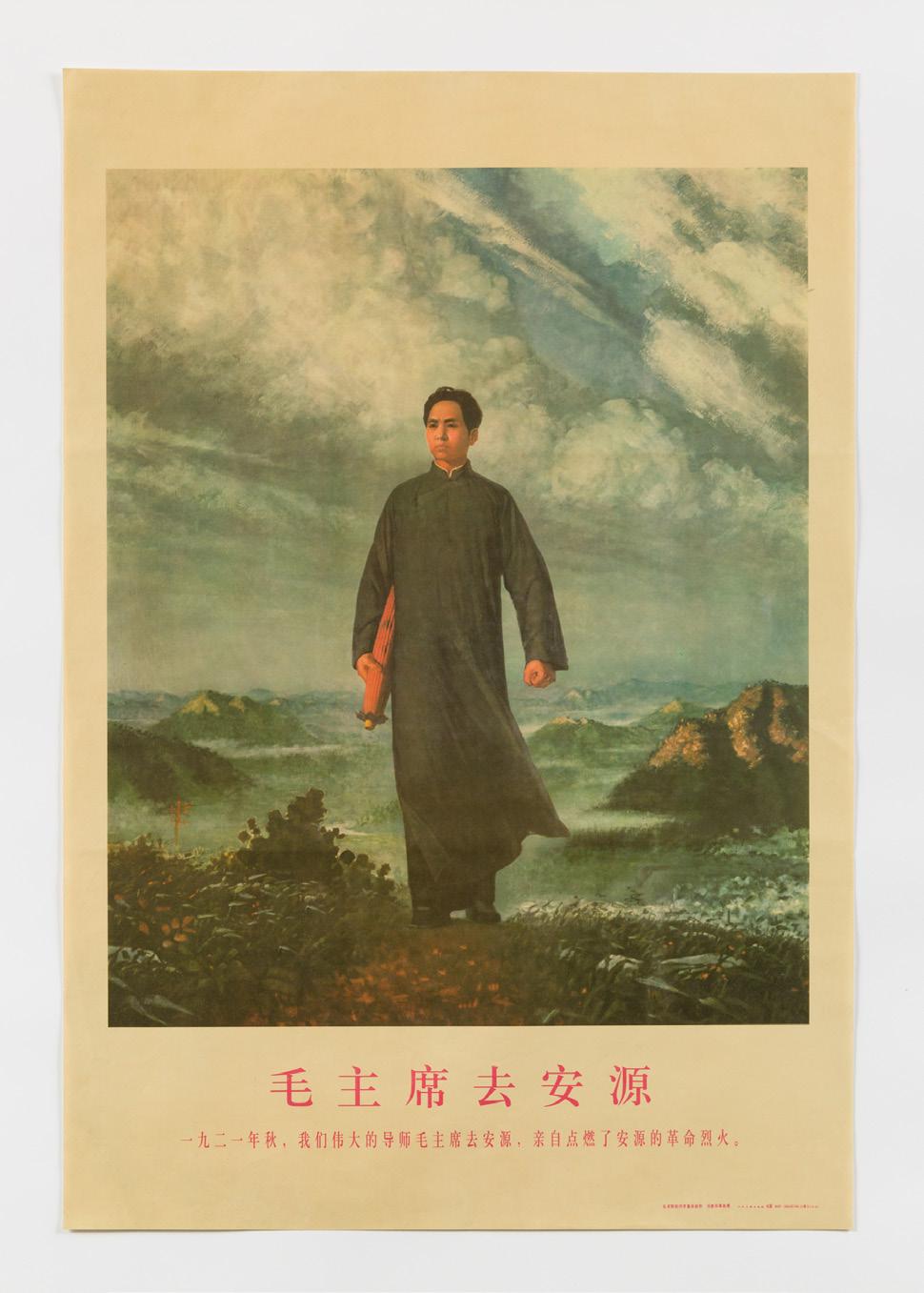

Liu Chunhua 刘春华

Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan

1968 Poster

Courtesy of Ethan Cohen

A young Mao, clad in traditional Chinese dress and holding an umbrella under his arm, strides purposefully across a romantic, cloudy landscape. The artist portrays the Chairman as a monumental, almost otherworldly figure, who towers over the distant mountains and whose head seems to touch the sky. The scene depicts the Chairman on his way to the city of Anyuan to help organize a miners’ strike, which took place in 1922 and was one of the critical events in the early history of the Chinese Communist Party. The larger writing on the poster announces the title, Chairman Mao goes to Anyuan; the smaller writing beneath describes how “in the fall of 1921, our great teacher Chairman Mao went to Anyuan, he personally ignited Anyuan’s revolutionary fire.” Liu Chunhua’s painting was designated as a revolutionary artistic model by Mao’s wife Jiang Qing and subsequently, was widely reproduced during the Cultural Revolution. Ironically, while many forms of Western painting had been banned during this period, Liu later admitted that the religious works of the Renaissance master Raphael had inspired his composition. Mao actually played a much smaller role in organizing the Anyuan miners’ strike than his colleague, Liu Shaoqi, who is featured as a main character in earlier depictions of the event. But after the growth of the Mao cult and purging of Liu Shaoqi, painters were called to reimagine the event and essentially, rewrite the narrative to glorify the Chairman.

Many household items were produced during the Cultural Revolution that celebrated Mao, the Red Guards, and the working classes. The face of this alarm clock features the Chairman, surrounded by Red Guards as they joyously wave their Little Red Books in the air.

19

毛主席去安源

Mao Alarm Clock 毛主席闹钟 1960s-70s Metal and glass Collection Wende Museum

19

Mao Jacket

中山服

20th century Cotton Courtesy of USC Pacific Asia Museum

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, male citizens and government leaders wore this style of suit—a military-inspired tunic suit with four pockets—as a symbol of proletarian unity and an alternative to the Western business suit. Although it was originally introduced by the revolutionary Sun Yat-sen (and named after him in Chinese), this garment became closely associated with Mao and an iconic part of the Chairman’s image. During the Cultural Revolution, it was worn widely by party officials as well as regular citizens, both male and female. Today, the Mao suit continues to be worn by Chinese Communist leaders for formal events, as a symbol of national pride.

Little Red Book 红宝书 1969

Paper and vinyl Collection Wende Museum

Quotations from Mao Tse-Tung, commonly called the Little Red Book due to its bright red cover and small size, is a collection of excerpts from speeches and writings by Mao. The work was initially compiled for military use by Lin Biao, head of the People’s Liberation Army, as part of a campaign for soldiers to study the Chairman’s political thought. However, the Little Red Book was widely distributed during the Cultural Revolution and by 1979, an estimated billion copies had been printed. The Little Red Book played a key role in promoting the cult of the Chairman, as Chinese citizens were expected to carry the book with them, study its content, and quote the Chairman.

20

20

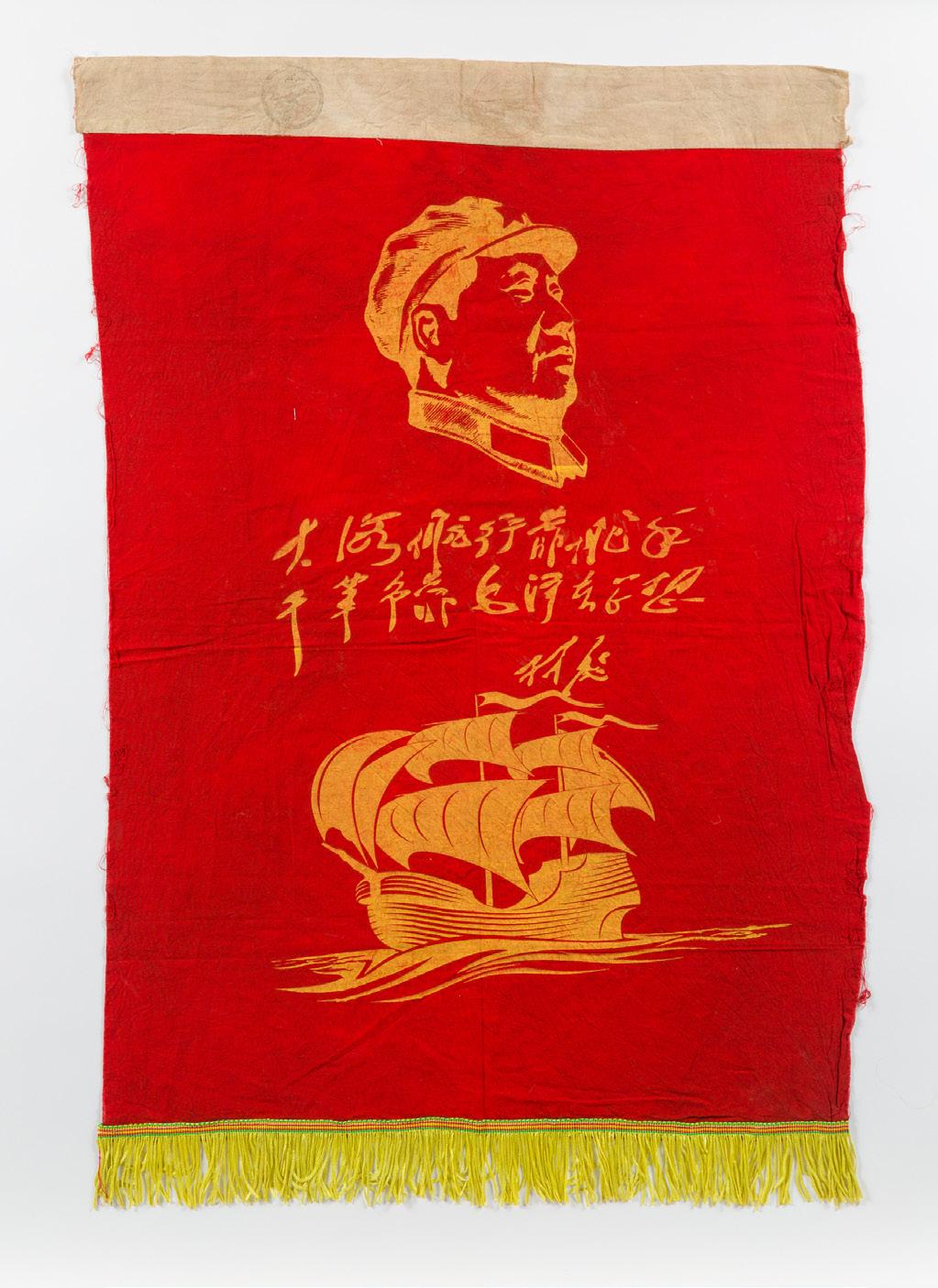

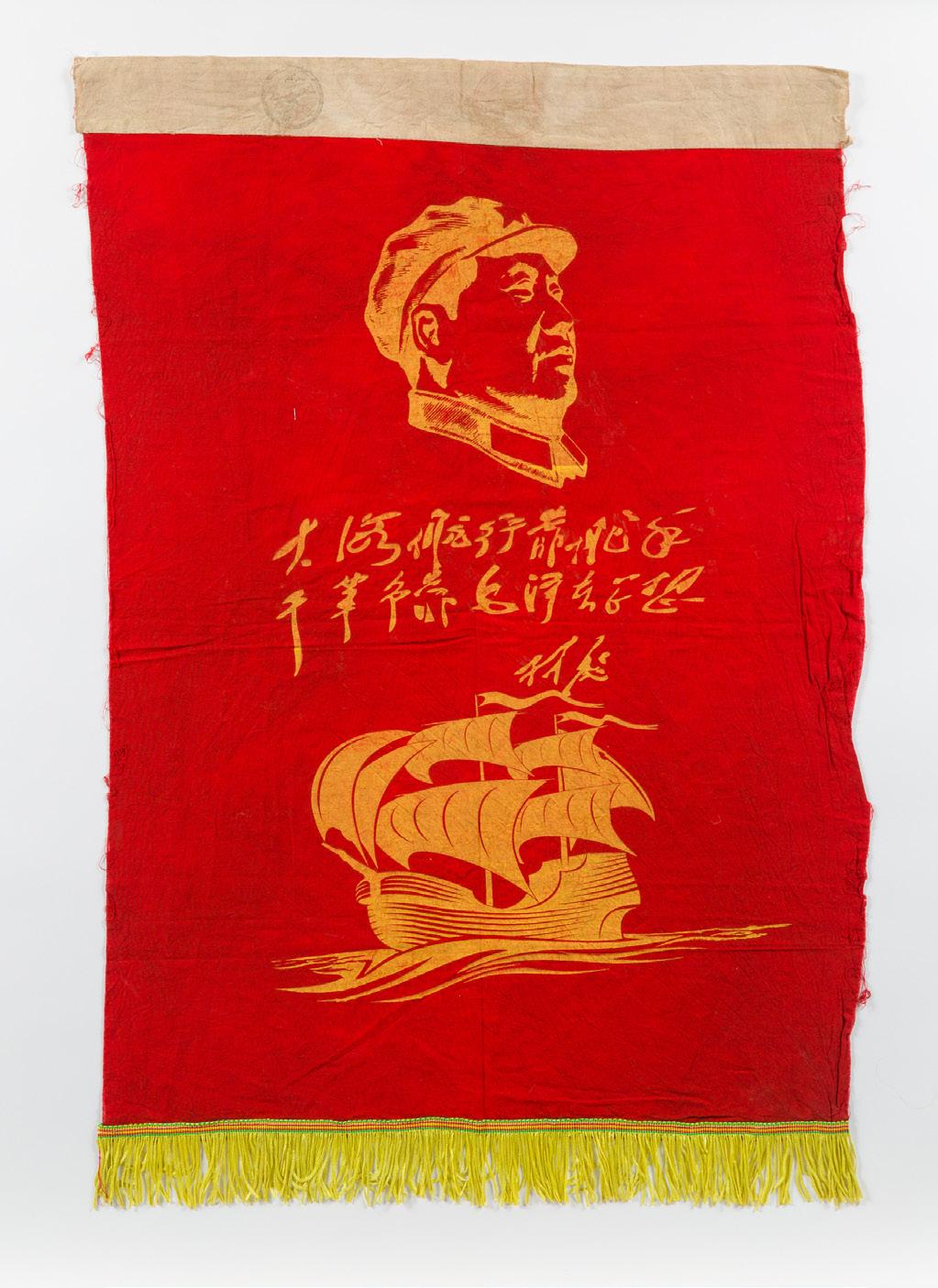

Mao Banner with Sunflowers

毛主席葵花旗

1960s

Textile Collection Wende Museum

The Great Helmsman 大舵手 1960s

Textile Collection Wende Museum

During the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards, work units, and other groups produced numerous banners and flags featuring portraits of the Chairman that were used to decorate public spaces. Both of these show Mao, wearing his People’s Liberation Army Uniform, with his face turned in three quarters. One is decorated in velvet, with a heart featuring the word zhong (忠) or loyalty. Sunflowers were closely associated with the Chairman, as Mao was often referred to as the “red sun” and the Chinese people as the sunflowers who turned towards him. The second flag features the ship of the famous Ming-dynasty explorer Zheng He. This image is paired with a quote from the revolutionary song praising Mao Zedong Thought, “Sailing the Sea Depends on the Helmsman.” The banner draws comparisons between Zheng He and the Chairman, who was also respectfully called the “Great Helmsman.”

21

21

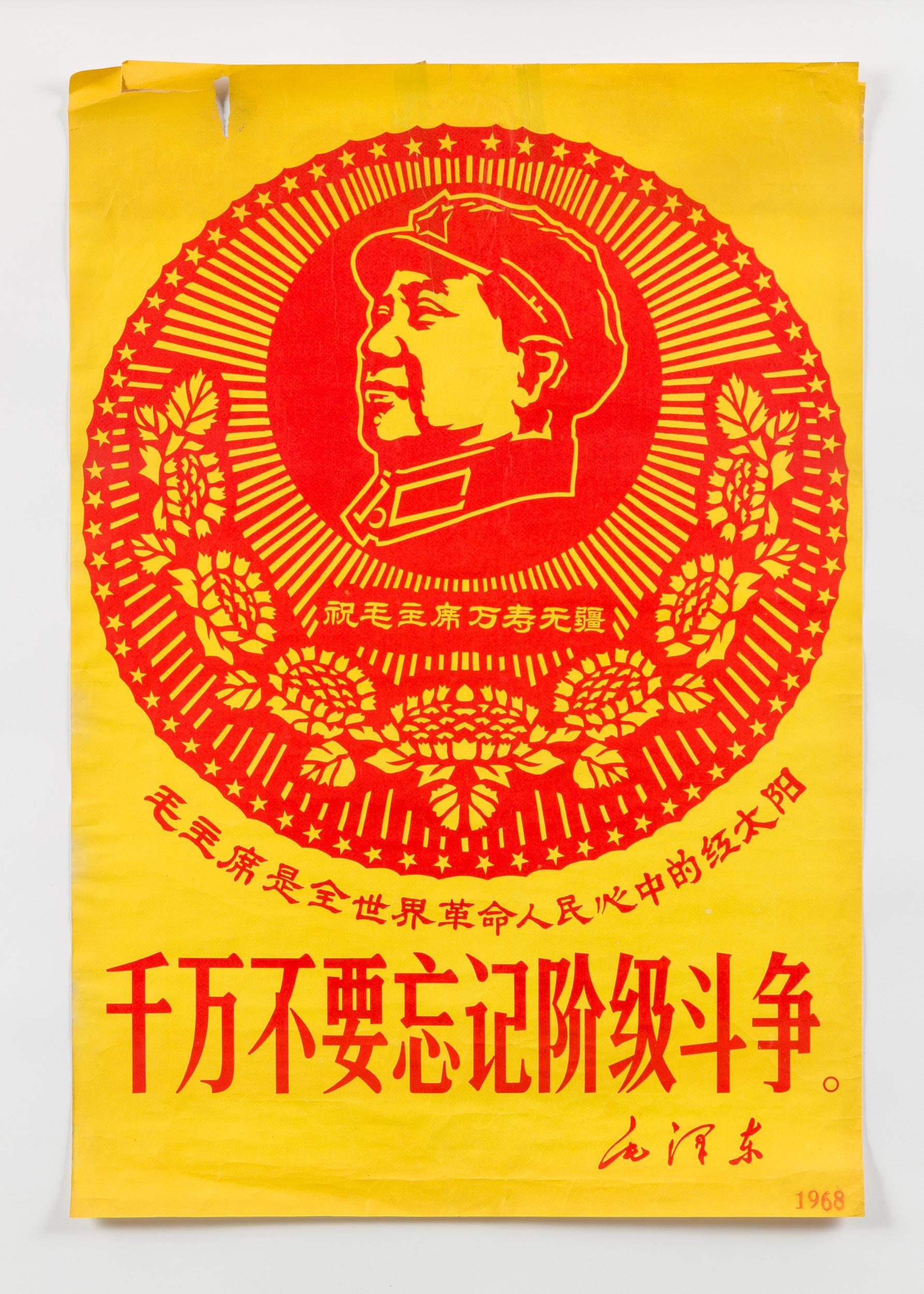

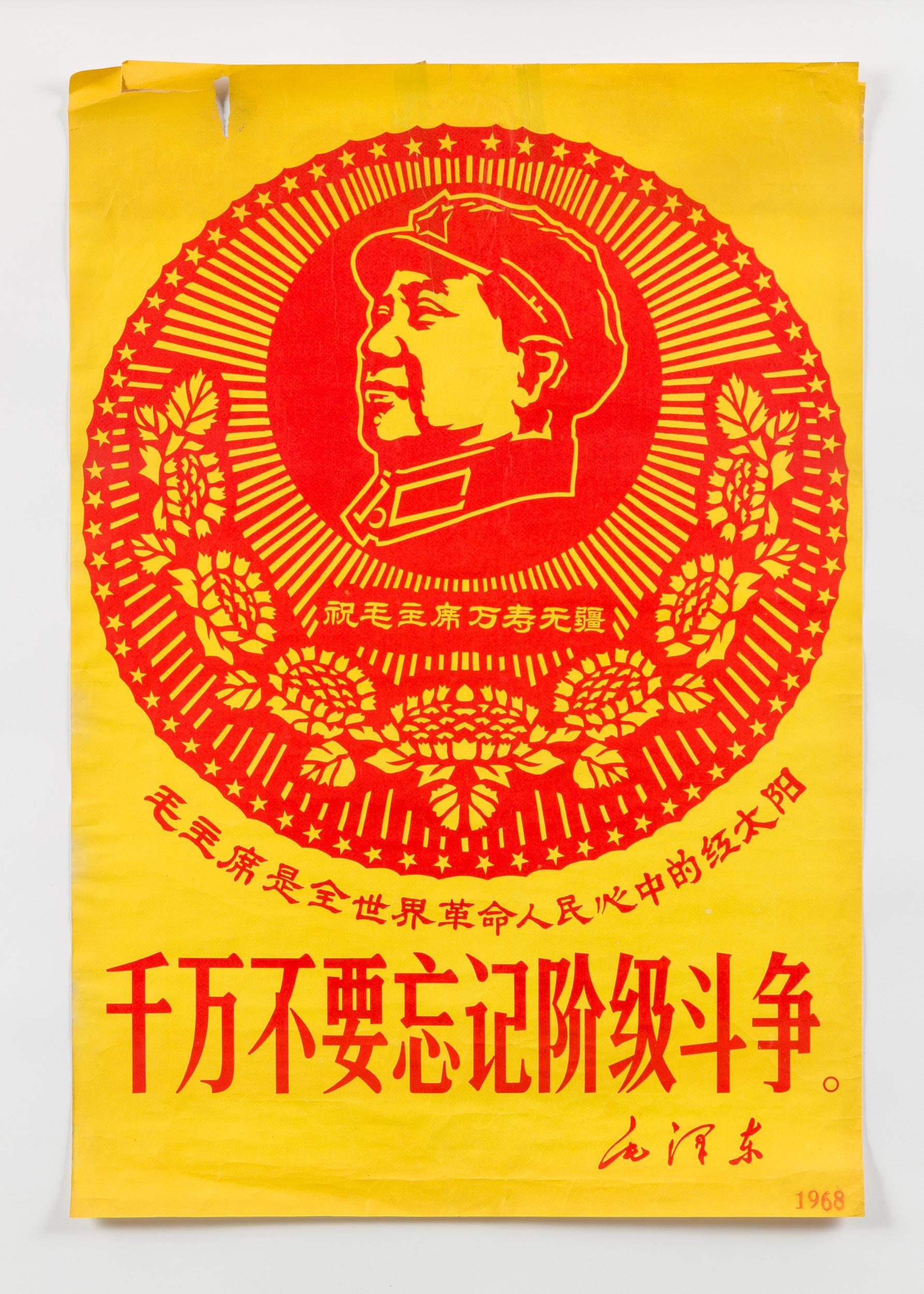

Never Forget Class Struggle

1968 Poster

This brightly colored poster features a portrait of the Chairman as the sun. He is surrounded by sunflowers, which represent the people of China, who turn toward their leader just as sunflowers turn toward the sun; this is reinforced by the inscription underneath the roundel, which reads “Chairman Mao is the red sun in the hearts of revolutionary people around the world.” The large writing on the bottom urges the viewer to “Never forget class struggle” while the text directly underneath Mao’s portrait wishes him “long life and boundless longevity.” The bold design of this poster—with a red cutout against a yellow background—draws from the traditional Chinese craft of papercut, one of the folk art styles that was promoted by Mao and the Chinese Communist Party.

22

千万不要忘记阶级斗争

Collection Wende Museum, donated by David E. James

22

IDEOLOGY AND ICONOCLASM:

THE RED GUARD MOVEMENT

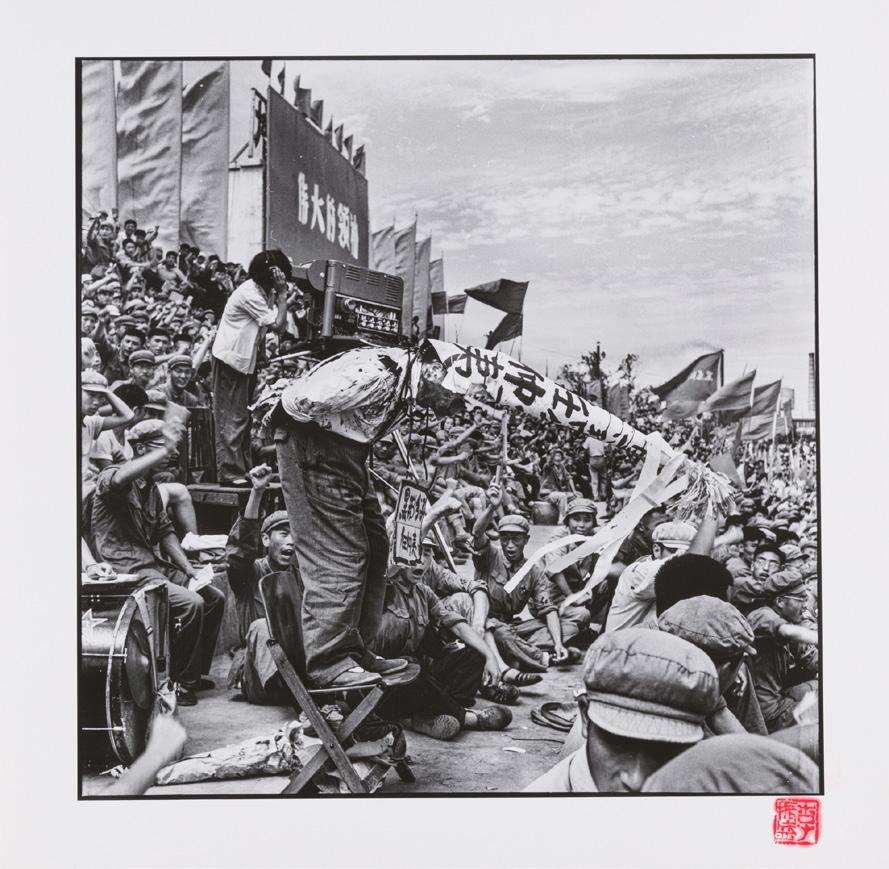

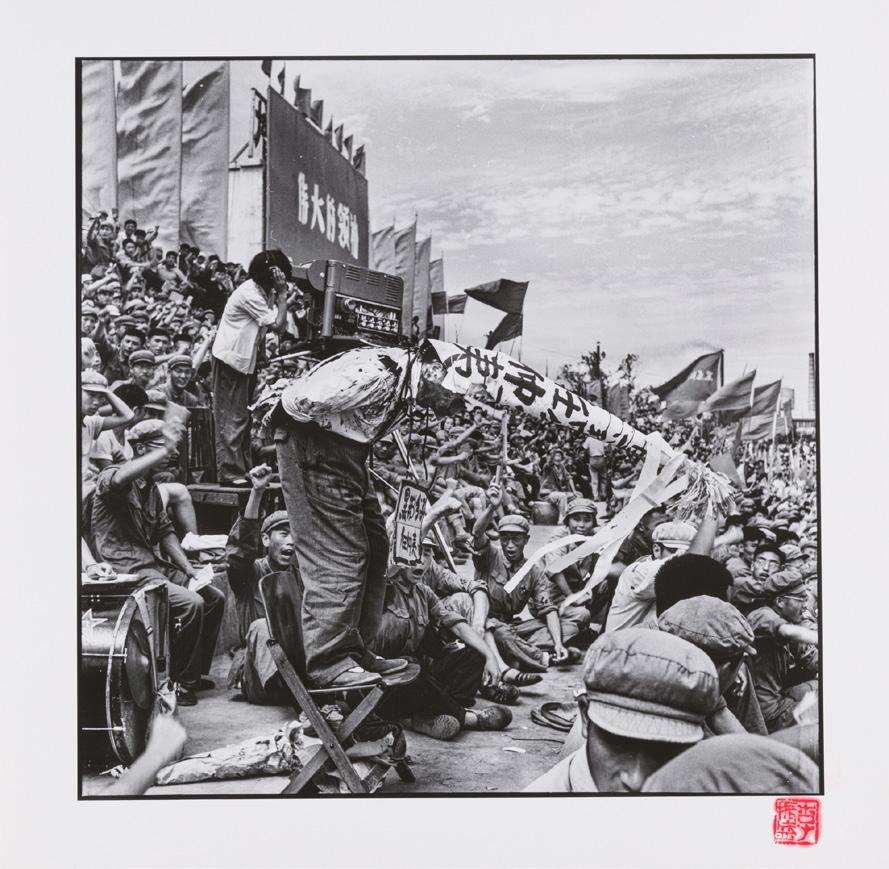

The first two years of the Cultural Revolution were a period of violence, with the rise of the Red Guards and the militarization of the cultural realm. Shortly after Mao announced the start of the movement on May 16th, 1966, students quickly formed into quasi-military groups called Red Guards, who pledged allegiance to the Chairman. With his approval, they overthrew the nation’s academic, governmental, and cultural institutions. People deemed as “black elements” were purged from their positions and subjected to struggle sessions, where they were publicly beaten and humiliated. Mao’s directive to “Smash the Four Olds”—old ideas, culture, habits and customs—also led to the mass destruction of cultural heritage and private property.

During these early years, ideology ran amok. China entered a period of near anarchy, as there were no government administrations to enforce laws or to oversee the “correct” way to carry out Mao’s policies. Rebel factions fought among themselves in armed battles over ideological disagreements and for control over territory; in Guangxi province, there were even incidents of ritual cannibalism practiced by Red Guard groups. Eventually, the chaos came to an end by 1969, after Mao ordered the Red Guards to disband and sent soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army to quell any resistance.

In spite of this destruction, the Red Guard years ironically produced some of the most iconic images and ephemera from the Cultural Revolution. These objects not only document the violence of the period, they also explore the distinct revolutionary aesthetic of the Red Guard movement, providing a glimpse into the militant, ideologically driven youth culture that turned the nation upside down.

Red Rebel Group

1966-1968

Textile Collection Wende Museum, donated by David E. James Banners and flags made by Red Guards highlighted their loyalty to the Chairman and helped differentiate themselves from other rebel groups. This particular banner, made by the “Red Rebel Group,” features a portrait of Mao as the sun. Its tattered, dirty appearance tells a story of how it might have been treated by the Red Guards.

23

红色造反团

23

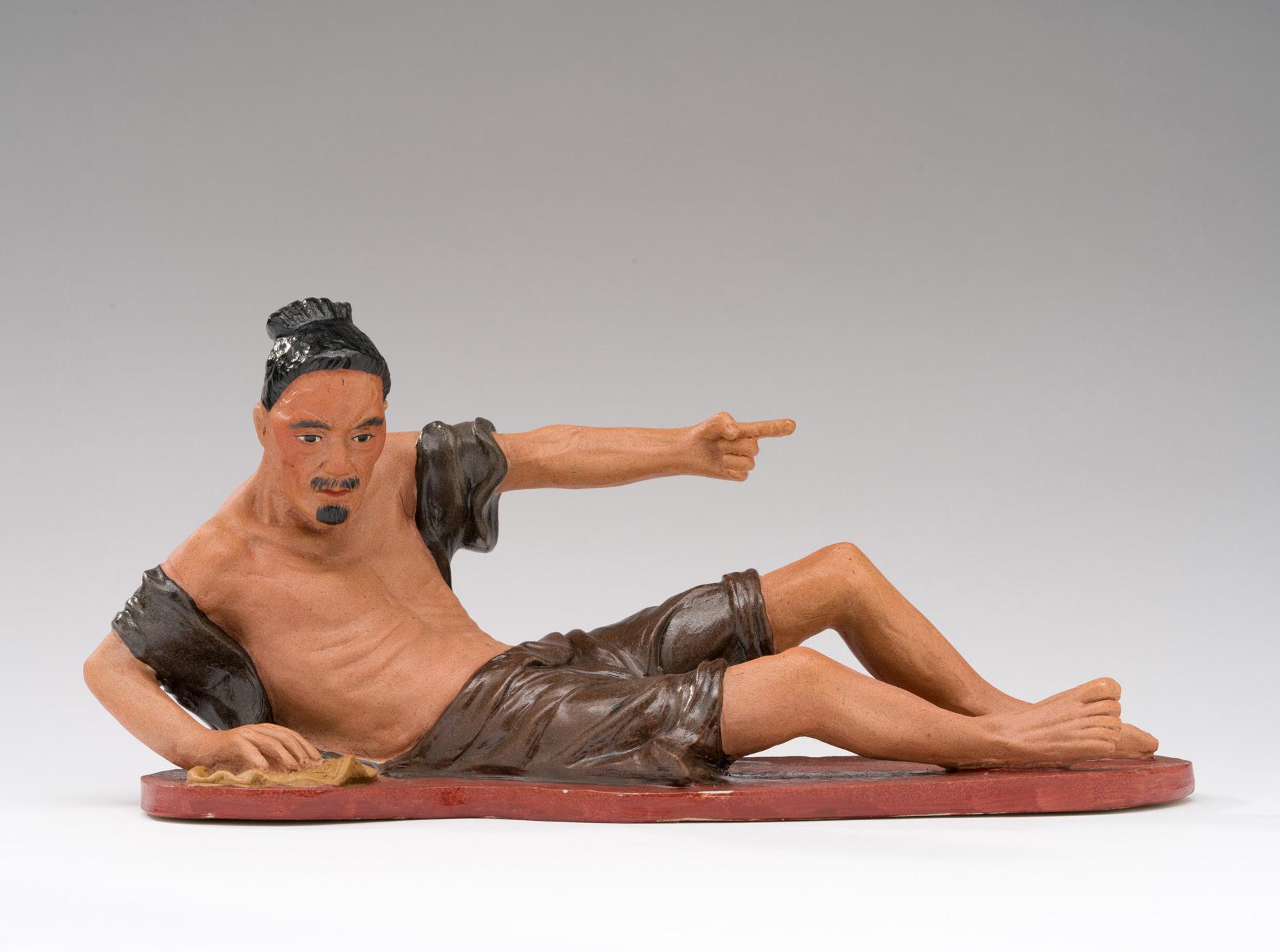

24 Criticize Reactionary Academic Authority 批判反动学术权威 1967 Porcelain Private Collection Down with Landowner Liu Wencai 打倒恶霸地主刘文彩 1966-1976 Porcelain Private Collection Jingdezhen Sculpture Factory 景德镇雕塑瓷厂 Use Words and Pens to Denounce Capitalists 口殊笔伐 1966-1976 Porcelain Private Collection 24

Down with Landowner Liu Wencai 打倒恶霸地主刘文彩 1966-1976

Porcelain Private Collection

Jingdezhen Sculpture Factory 景德镇雕塑瓷厂

Overthrow Reactionary Academic Authorities 打倒反动学术权威

1966-1976

Porcelain Private Collection

The struggle session—where alleged class enemies were publicly humiliated and beaten by Red Guards—is one of the most iconic and disturbing practices to emerge from the Cultural Revolution. After Mao’s call to revolution, Red Guards swiftly imprisoned those they believed to be bourgeois, capitalists, intellectuals, landlords, or revisionists. The early years of the movement bred a culture of fear, as neighbors, colleagues, and family members denounced one another for the most minor of crimes—such as being in possession of a “bourgeois” book by Charles Dickens or listening to Western music. Four ceramics in this case depict triumphant struggle sessions against Liu Wencai, a legendary evil landlord, and intellectuals—who are forced to kneel and wear dunce caps—and celebrate Red Guard ideological zeal. However, these works present a highly sanitized account, omitting the violence and suffering caused by the struggle sessions, as many victims died from the ordeal. Interestingly, one ceramic features the main character from the revolutionary ballet, The White-Haired Girl. In this story, the eponymous white-haired girl overcomes an evil landlord, Huang Shiren. This sculpture conflates the landlord Liu Wencai with his fictional counterpart. The fifth ceramic in this vitrine celebrates the Red Guards’ struggle against capitalist ideology through writing criticisms and denouncing those considered bourgeois or revisionist. The Red Guards are depicted holding a pen as a weapon and calligraphy banners, fighting anti-revolutionaries through their words rather than with guns.

25

25

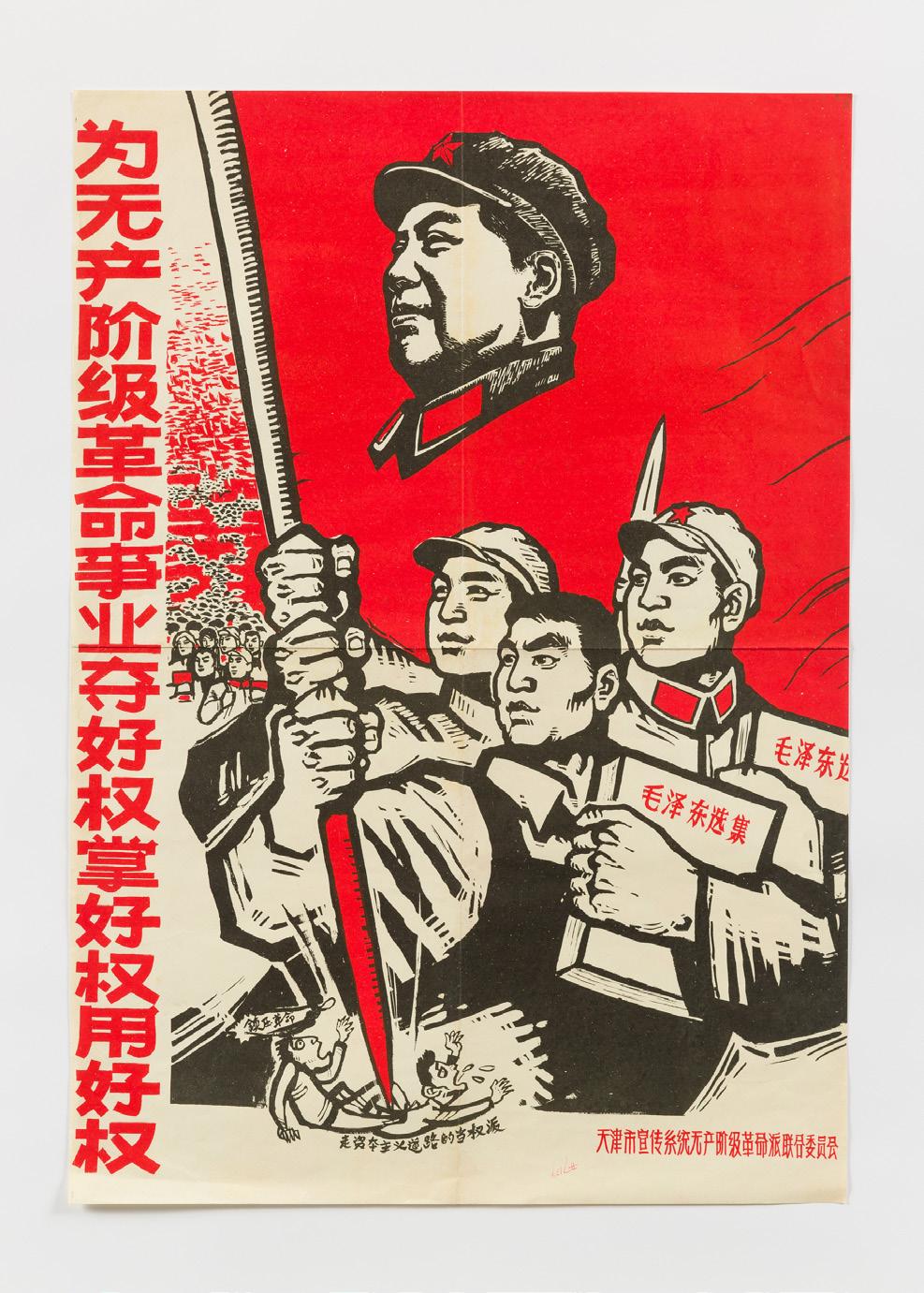

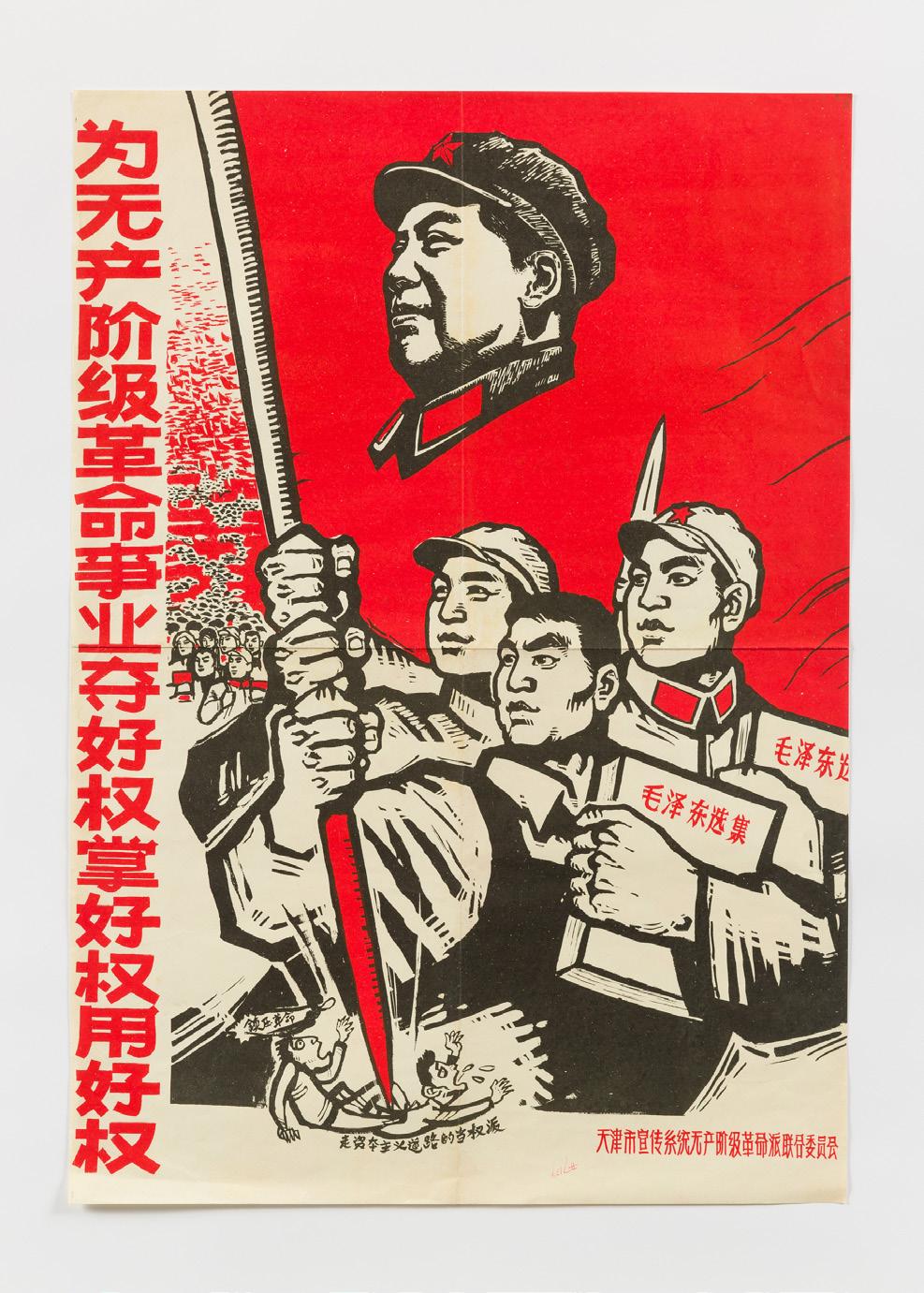

Tianjin Propaganda System and Proletarian Revolutionary Joint Committee 天津市宣传系统无产阶级革派联合委员会

Seize and Use Power Well for the Cause of the Proletarian Revolution 为无产阶级革命事业夺好权掌好权用好权 1968 Poster

Collection Wende, donated by David E. James

Capital Red Guard “Bayonet Sees Red” Editorial Office 首都红卫兵 “刺刀见红” 编辑部

Whoever Opposes Chairman Mao Will Have His Dog-Head Smashed!

谁反对毛主席就砸烂他的狗头! 1968

Poster

Courtesy of Ethan Cohen

Many Red Guard posters reflect the violent methods promoted by these groups to forward the revolution; the poster by the group called “The Bayonet Sees Red” features Mao as the sun, and to the right, a shouting Red Guard, arm raised, and brandishing a gun. It announces that “whoever opposes Chairman Mao will have their dog-head smashed!” Other revolutionary groups quickly adopted this Red Guard aesthetic. Another poster, made by Tianjin’s Propaganda System and Proletarian Revolutionary Joint Committee, exhorts the viewer to “seize and use power well for the cause of the proletarian revolution.” It features a portrait of the Chairman with two workers and a soldier, clutching copies of the Little Red Book and using a pen to spear two fallen enemies—”capitalist roaders,” or people who followed the path of capitalism instead of socialism. To demonstrate their revolutionary zeal and to spread their ideology, Red Guard groups across the nation produced numerous posters during the early years of the Cultural Revolution. These were often made with woodblock print, which was considered an appropriate revolutionary medium endorsed by the Chinese Communist Party, who had produced numerous woodcuts during the Sino-Japanese (1937-1945) and Civil Wars (1945-1949) for propaganda purposes. With their bold graphic design and color scheme, these posters are among the most recognizable images to emerge from the Cultural Revolution.

26

26

Little Red Soldier 小红兵 1969

Porcelain Private Collection

This cheerful, brightly colored vase depicts a grandmother tying a Red Guard band on the arm of a young boy. Nearby, his sister carries a bucket, ready to join the other children outside to work in the fields. While high school students formed into Red Guard groups, even young children were encouraged to join in political events. During the Cultural Revolution, all citizens both young and old were expected to actively participate in revolutionary activities.

Jingdezhen Art Porcelain Factory 景德镇艺术瓷厂

Long March Diary 长征日记 1962 Porcelain Private Collection

Based on a painting by Chen Yanning, this vase depicts a young soldier writing in her diary during the infamous Long March (1934-1935), when the Red Army, fleeing hostile Nationalist forces, marched over 6,000 miles to relocate their headquarters from Southeastern China to the city of Yan’an in the Northwest. The writing on the back of the vase urges the viewer to “retake the route of the Long March” and “vow to be a revolutionary person.” Works such as these glorified the early years of the Chinese Communist Party and helped establish the Long March as one of the legendary events in the Party’s history. During the Cultural Revolution, students were eager to revive the revolutionary fervor of previous decades and emulate old Party heroes. Many groups of Red Guards packed their bags and went on their own Long March, traveling across the nation on foot to pay pilgrimage to important cities in Communist history such as Yan’an, Shaoshan, Mao’s birthplace, and Jinggangshan, the site of the Chinese Communist Party’s first soviet, or elected government council.

27

27

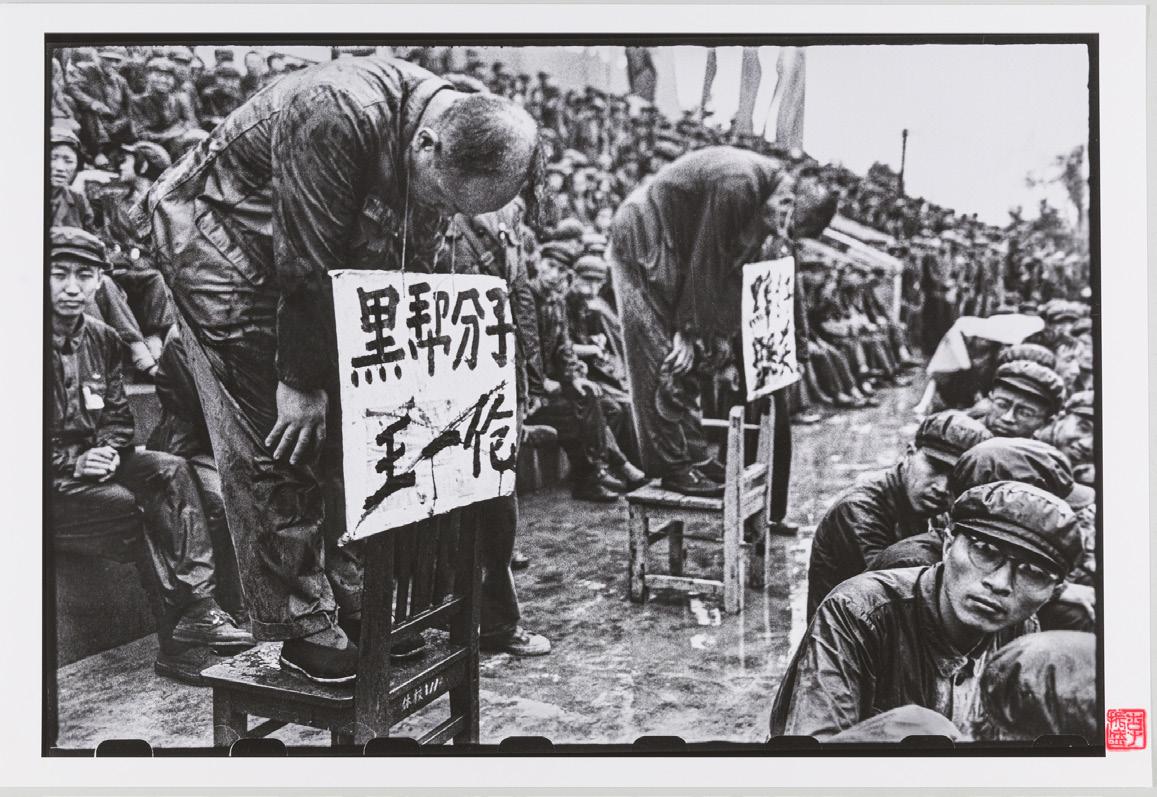

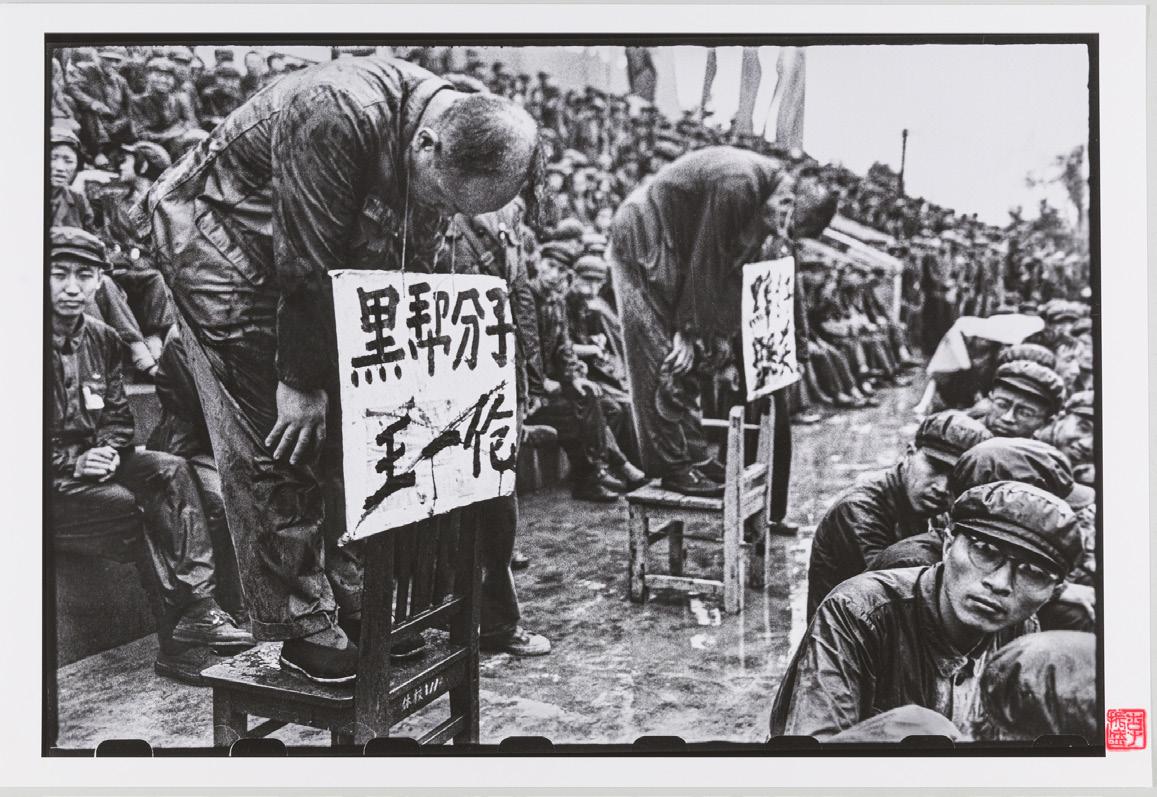

Li Zhensheng 李振盛 Struggle Session of Ren Zhongyi 任仲夷之批斗大会

1966

Inkjet print Private Collection

Li Zhensheng 李振盛

Top Party Officials Denounced During a Red Guard Rally 红卫兵批斗干部 1966 Inkjet print Private Collection

Li Zhensheng 李振盛 Library of the Harbin Construction Institute

1966

Inkjet print Private Collection

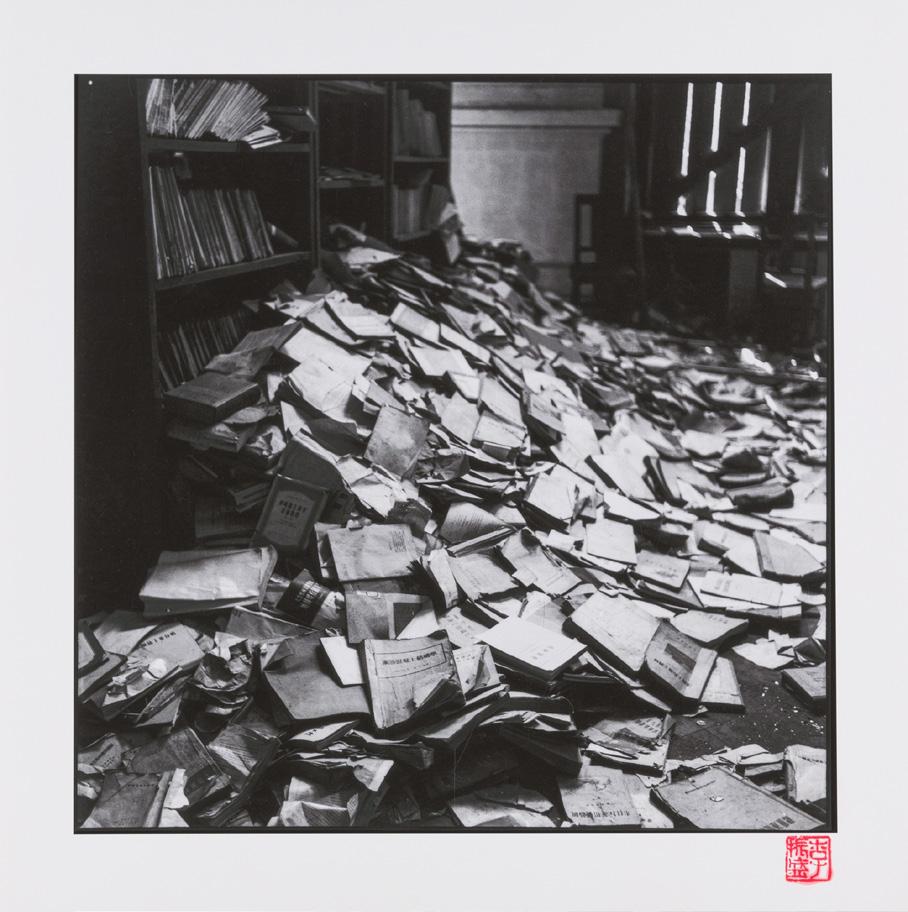

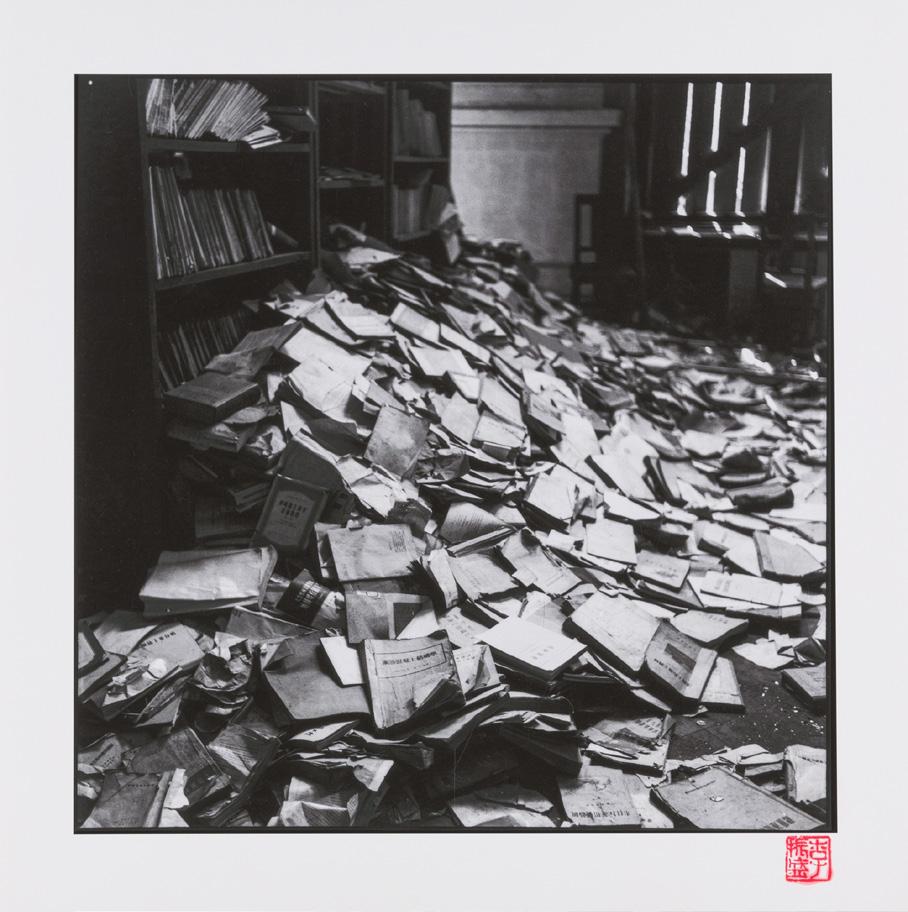

Li Zhensheng worked as a newspaper photographer in Harbin during the Cultural Revolution. In addition to taking propaganda shots for official publications, he secretly took many photographs that documented the darker side of the movement. Fearing political repercussions, he hid the negatives under the floorboards of his home in Harbin until 1988, when he first exhibited a set of twenty photographs at a competition in Beijing. These three photos by Li capture the violence of the Red Guard movement. Unlike the ceramic versions nearby, the two photographs fully illustrate the brutality of struggle sessions: one against the Communist Party secretary of Harbin, Ren Zhongyi, and the other against several disgraced party officials. The third photograph shows the destruction caused by physical fighting between rebel groups as they struggled against one another for control. The library at the Harbin Construction Institute was ransacked during a battle between two groups, as hardcover books were thrown as projectiles.

28

哈尔滨工业大学图书馆

28

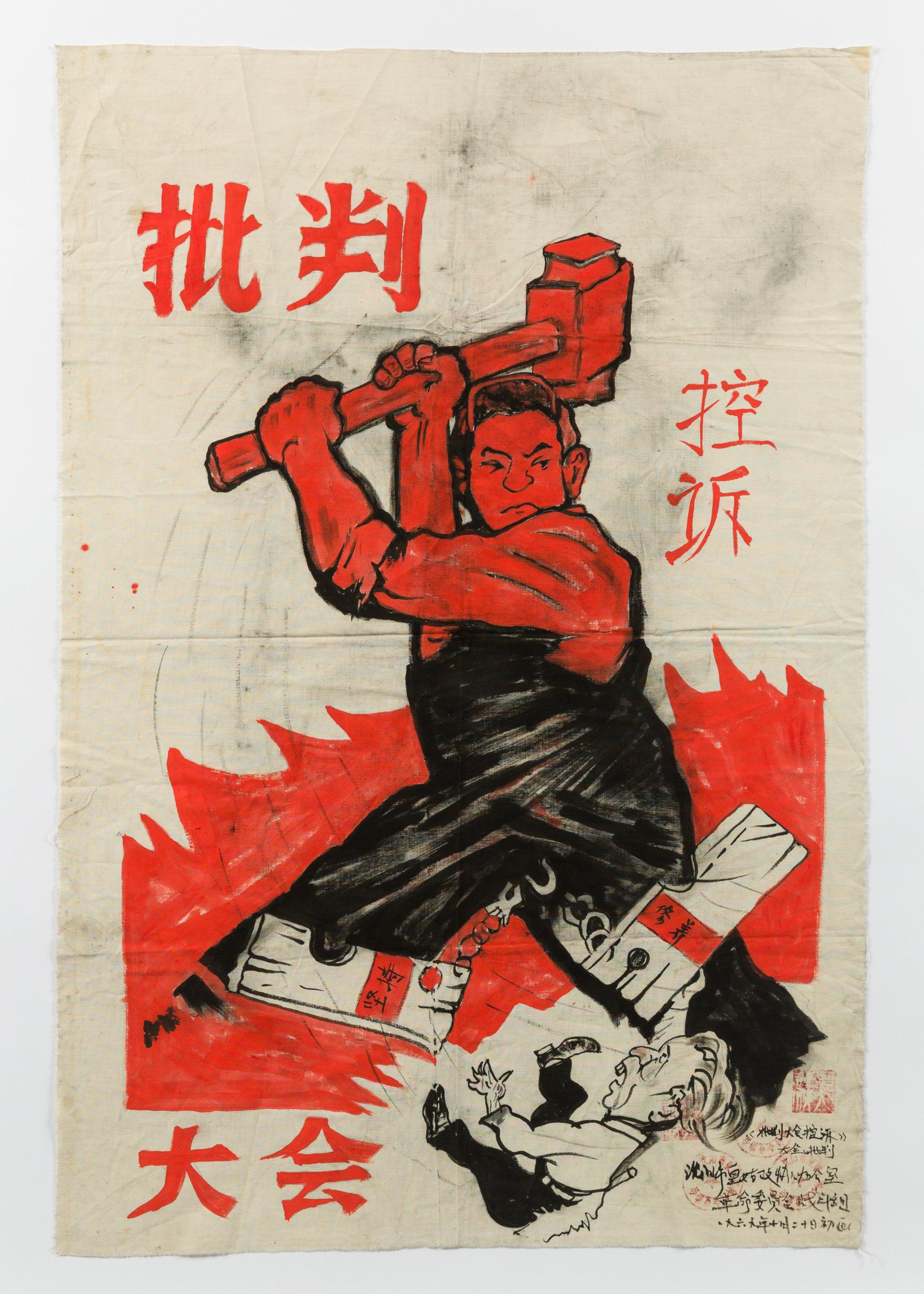

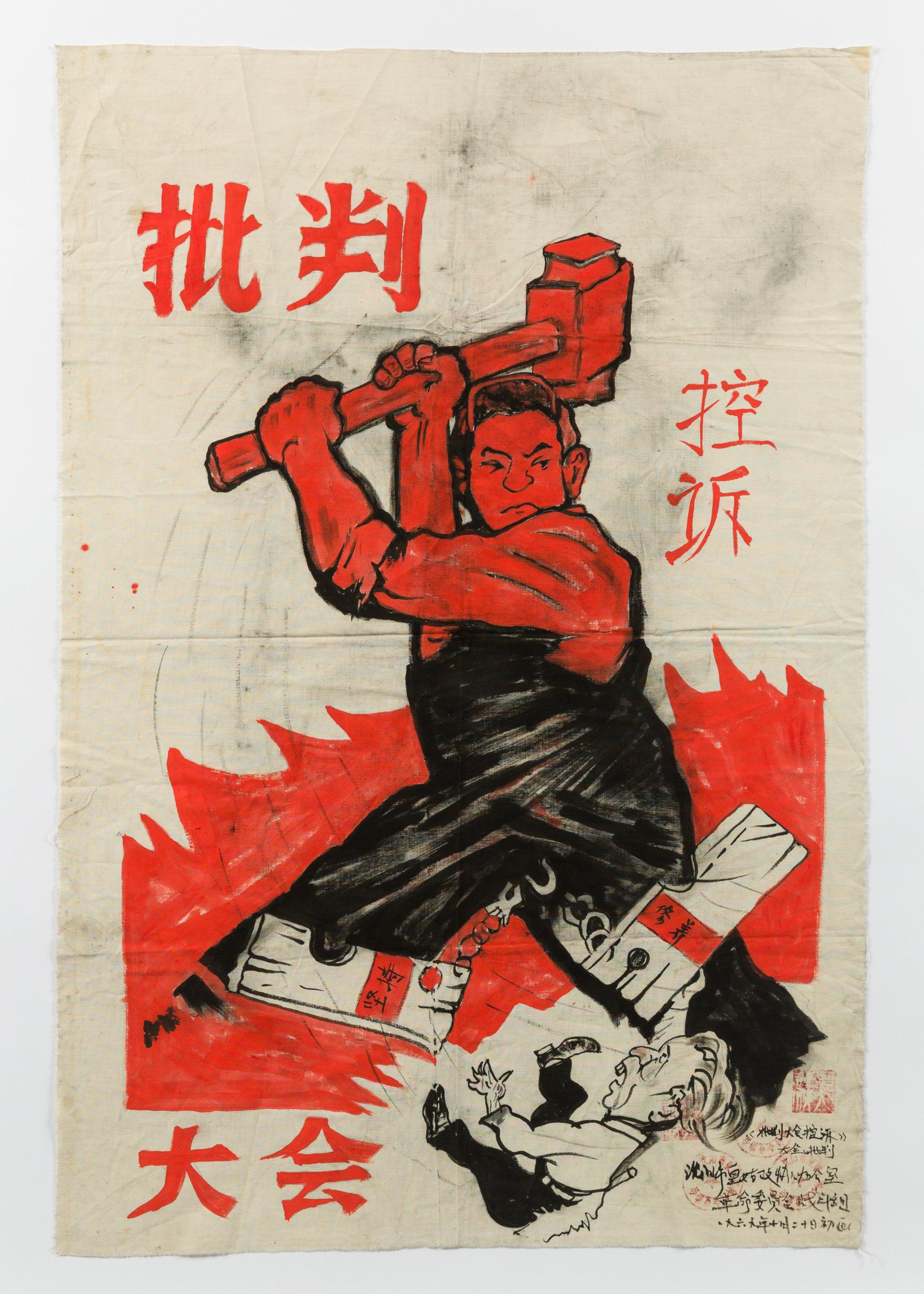

Shenyang Criticism Committee Meeting

1969

Textile Collection Wende Museum

A factory worker lifts a large hammer to smash a wooden stock used to hold the tiny caricature of Liu Shaoqi, a senior Party official and intended successor of Mao who was purged at the start of the Cultural Revolution. The banner, which advertises a Criticism Committee meeting, organized by the Revolutionary Battle Committee in the city of Shenyang, highlights the violent ideology promoted by rebel groups during the early years of the movement. The painting on the banner imitates the bold red and black graphic style of Red Guard posters, some of which are on display in this section, that were made from woodblock prints.

29

沈阳批判大会

29

WORKERS, PEASANTS, AND SOLDIERS: MAOIST

ART THEORY

After the chaos of the Red Guard years, official art production slowly resumed. According to Mao, art could never be separate from politics, as its purpose was to teach good revolutionary behavior and forward the Socialist cause. Many styles and topics were banned for being politically incorrect. The arts were to be made for the consumption of “the masses”—namely the workers, peasants, and soldiers, who were considered to be the backbone of the nation—as part of Mao’s greater plan to popularize the arts and to improve living conditions, especially in rural China. Many professional artists were purged or imprisoned. Simultaneously, the government encouraged workers, peasants, and soldiers to participate in Socialist art making and published their works to highlight the creativity of the masses. However, in many cases, these amateur artists received help from trained artists who were sent to the countryside.

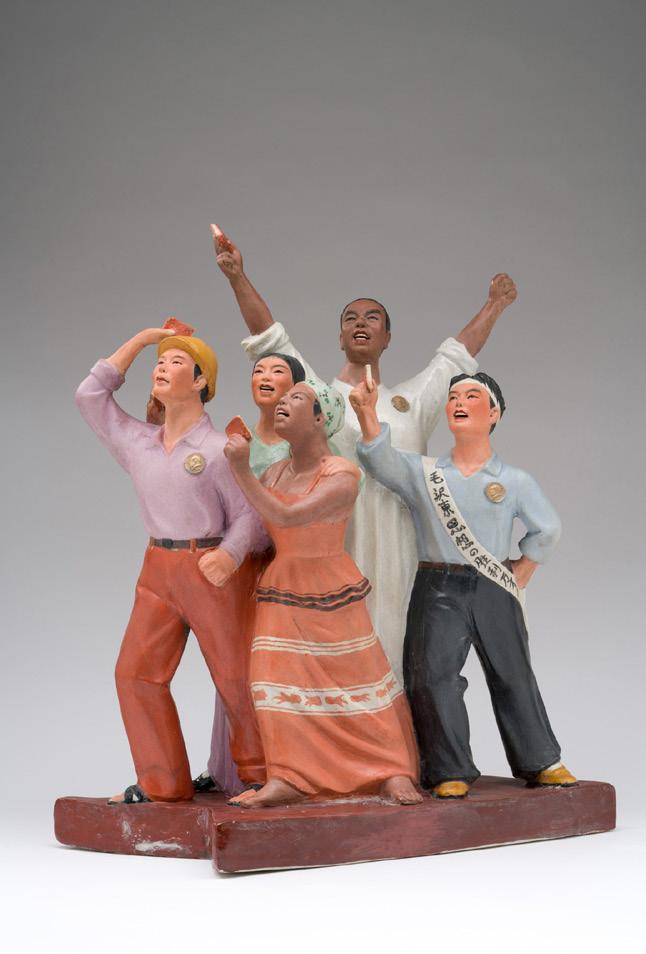

The objects in this section illustrate the different artistic styles inspired by Chinese folk art and Socialist Realism that were promoted by the government and depict positive scenes of agricultural, military and industrial work. Ultimately, during the Cultural Revolution, artistic creation became centered around the nation’s workers, peasants, and soldiers. However, these images—with their happy and healthy figures—may not represent the actual experience of the masses especially after the disaster of the Great Leap Forward, when millions died of starvation in the countryside.

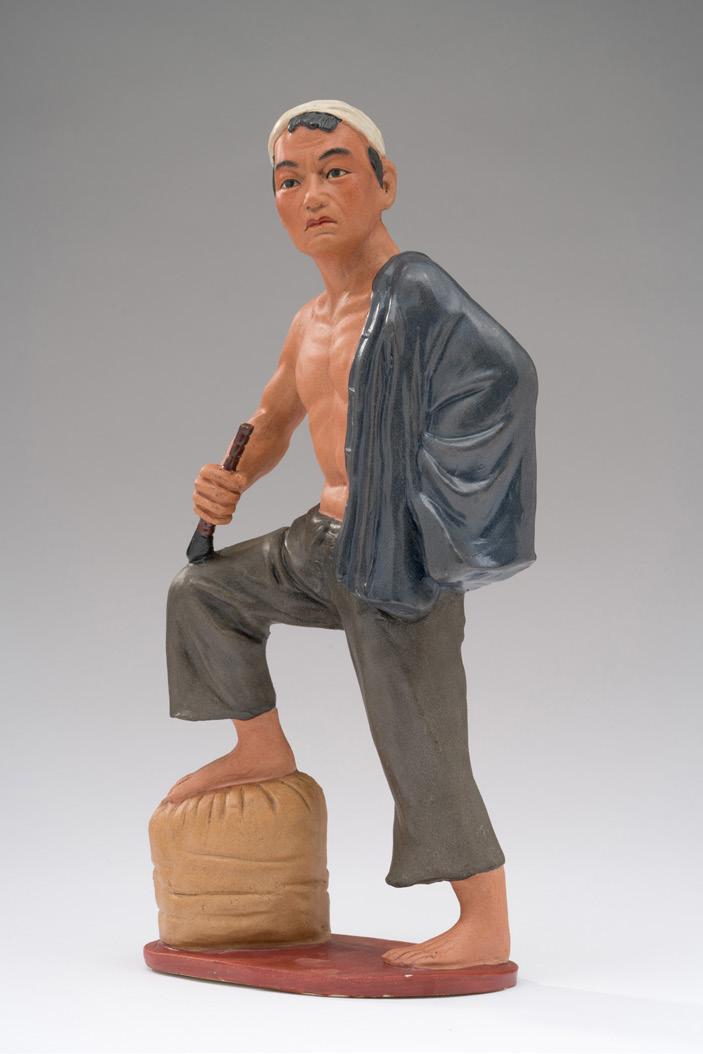

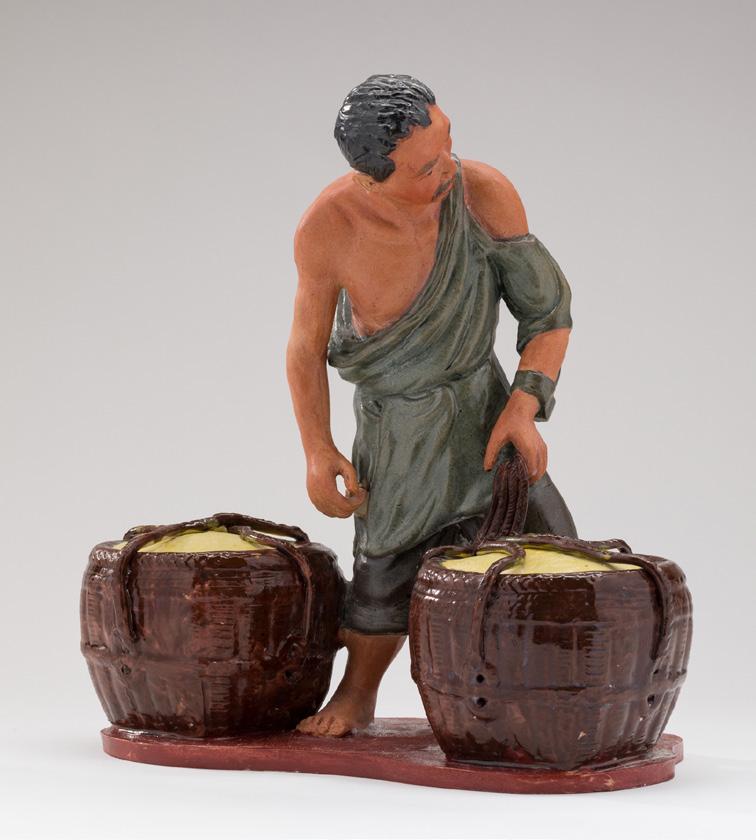

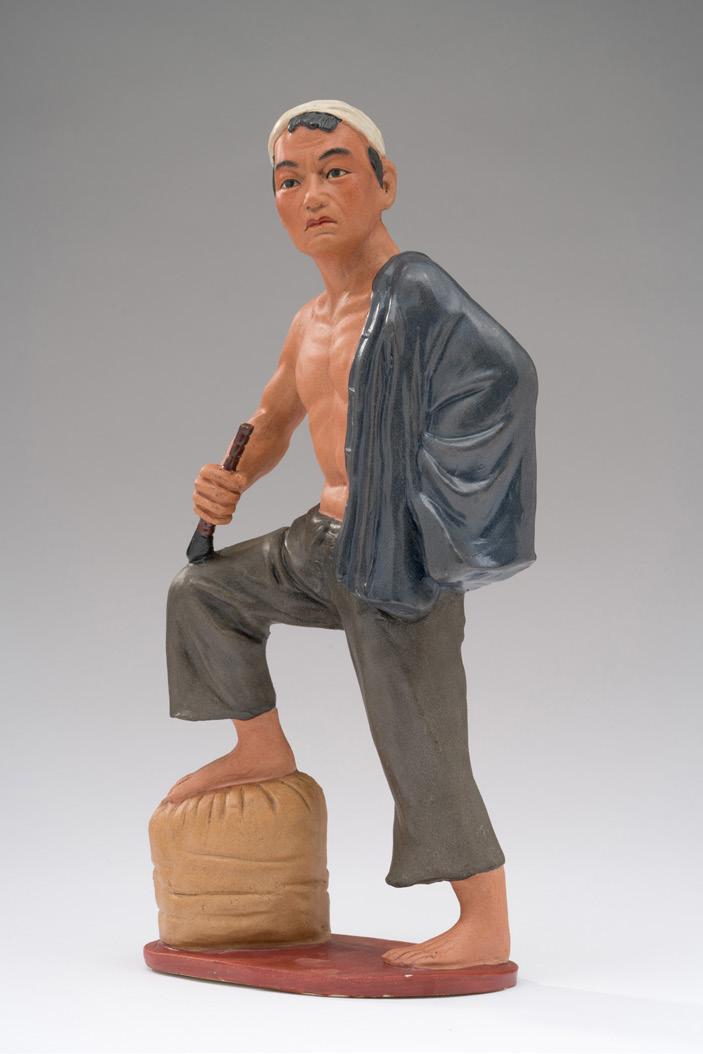

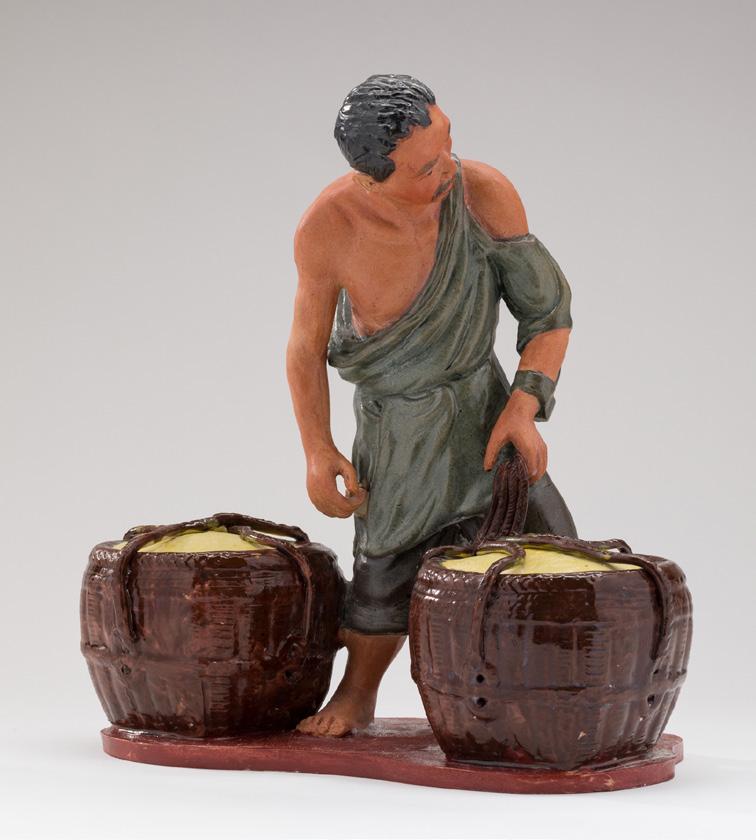

Jingdezhen Sculpture Factory 景德镇雕塑瓷厂

Worker, Peasant and Soldier 工农兵 1966-1976 Porcelain Private Collection

This sculpture, along with others in this vitrine, celebrates the nation’s “masses”: workers, peasants, and soldiers who made up the backbone of the nation, according to the Communist state. A soldier, dressed in his People’s Liberation Army uniform and holding a gun, is joined by a farmer, who holds a sheath of grain over her head, and a factory worker dressed in his uniform of overalls and cap.

30

30

Miner and Factory Workers

矿工和厂工

1966-1976

Porcelain Private Collection

This sculpture features a miner, wearing a hardhat and headlamp, a factory worker with goggles, and a textile worker holding spools of thread. The sculpture celebrates the workers of China and the different elements of Chinese industry, highlighting one of Mao’s main goals to transform the nation’s economy through industrialization.

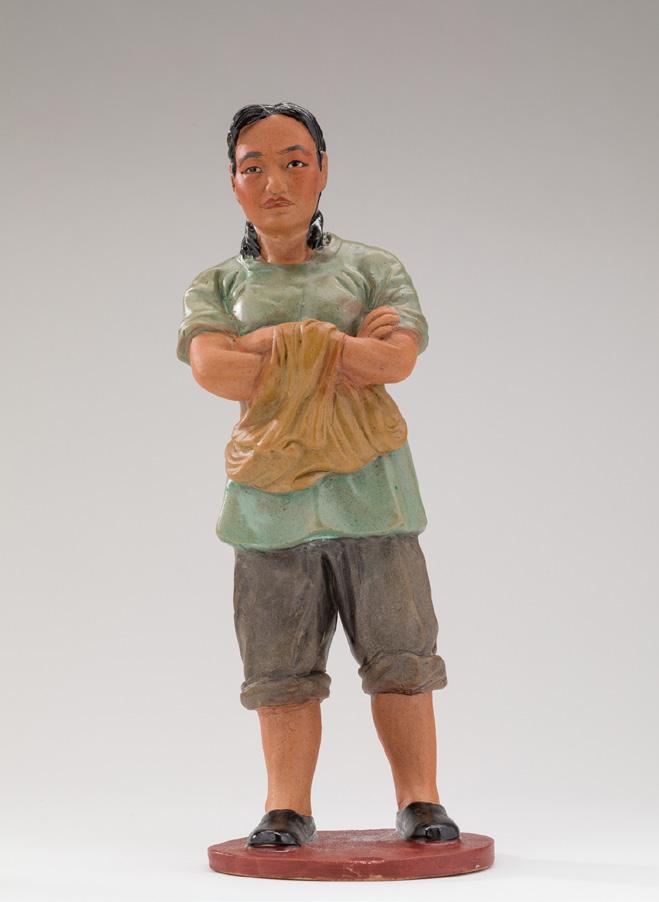

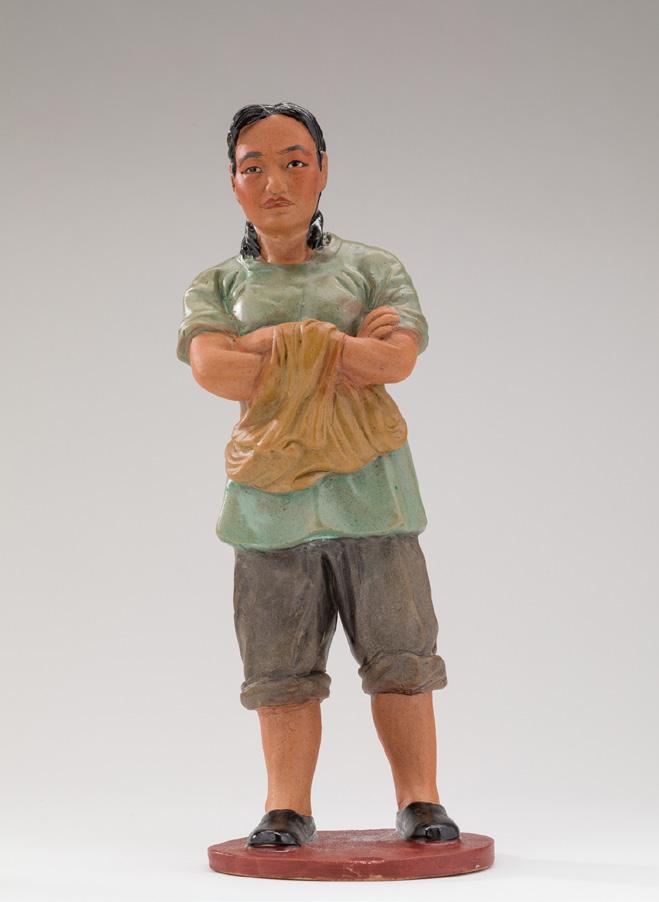

Textile Worker

纺织厂工人

1966-1976 Porcelain

Private Collection

This sculpture depicting a female textile worker clutching a bundle of cotton celebrates women’s contributions to the nation’s industry. The Chinese Communist Party sought to overturn the traditional gender roles of dynastic China, in which women were relegated to the home. They encouraged women to enter the workforce as equal members of society.

31

31

Jingdezhen Art Porcelain Factory

景德镇艺术瓷厂

The Postman Sent the Newspaper to the Fields 邮递送报到田

1974

Porcelain Private Collection

In 1968, Mao ordered the Red Guards to disband and relocated thousands of students from the cities to rural regions to learn from the peasants and participate in hard labor as part of the “Down to the Countryside” movement. This vase depicts a group of these rusticated or “sent down” youths who are taking a break from their work in the rice fields to read the national newspaper, The People’s Daily, which has just been delivered by the local postman. While rusticated youths were often depicted as healthy and happy in the art from the period, many of them grew homesick and faced extremely harsh living and working conditions. Because of the “Down to the Countryside” movement, many young people who came of age during the Cultural Revolution missed important educational opportunities, such as attending university, and are known today as China’s “lost generation.”

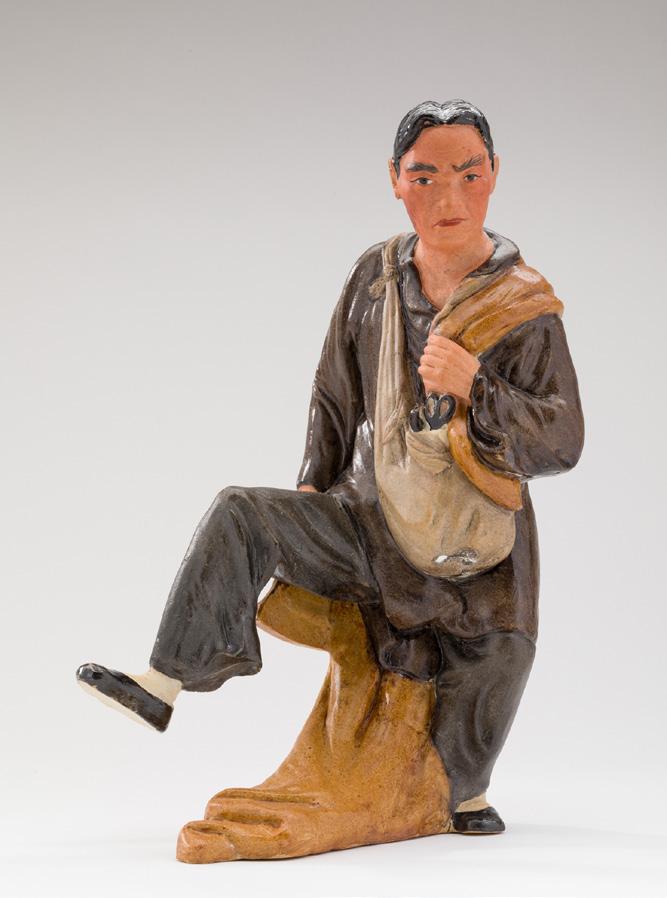

Jingdezhen Sculpture Factory

景德镇雕塑瓷厂

Daqing Oil Field Workers 大庆油田工人

1966-1976

Porcelain Private Collection

Four workers from the Daqing oil field wear heavy overcoats and warm hats as they stand proudly with their mining tools. The Daqing oil field, discovered in 1959, was the nation’s first major oil field and its most famous one. It was promoted as a model industrial enterprise during the Cultural Revolution due to its large production, while its workers were celebrated for their tireless work ethic and contribution to the nation’s industrialization. Until the early 1960s, China was dependent on the Soviet Union for its oil. However, the rupture in diplomatic relations between the two nations caused the People’s Republic of China to quickly develop its own oil industry with the hope of becoming self-reliant.

32

32

Ministry of Light Industry Ceramic Research Office 轻工业部陶瓷研究所

The Army Loves the People 军爱民

1974

Porcelain Private Collection

This vase illustrates the cooperation between the People’s Liberation Army and the nation’s farming communities. In this scene, an old man pours a drink of water for a soldier, who is taking a break from helping the farmer till the fields. The back of the vase reinforces the need for solidarity between the different social groups; it reads: “The army loves the people, the people support the army, the military and people are united as one; try to see who the enemies are in the world.”

Zhang Jian

章鉴

Educated Youth Projection Team 知青放映队 1969

Porcelain Private Collection

Many rusticated youths (known also as “educated youths”) participated in artistic pursuits in spite of their rigorous work schedules. Besides painting commune murals and performing in local theatrical productions, some students joined projection teams that brought films—often the model performances, or yangbanxi—out to the countryside. These projection teams played an important role in Mao’s goal of popularizing the arts and bringing modern technology to rural areas; oftentimes, the films screened by these projection teams were the only forms of modern entertainment available to villagers in rural China.

33

33

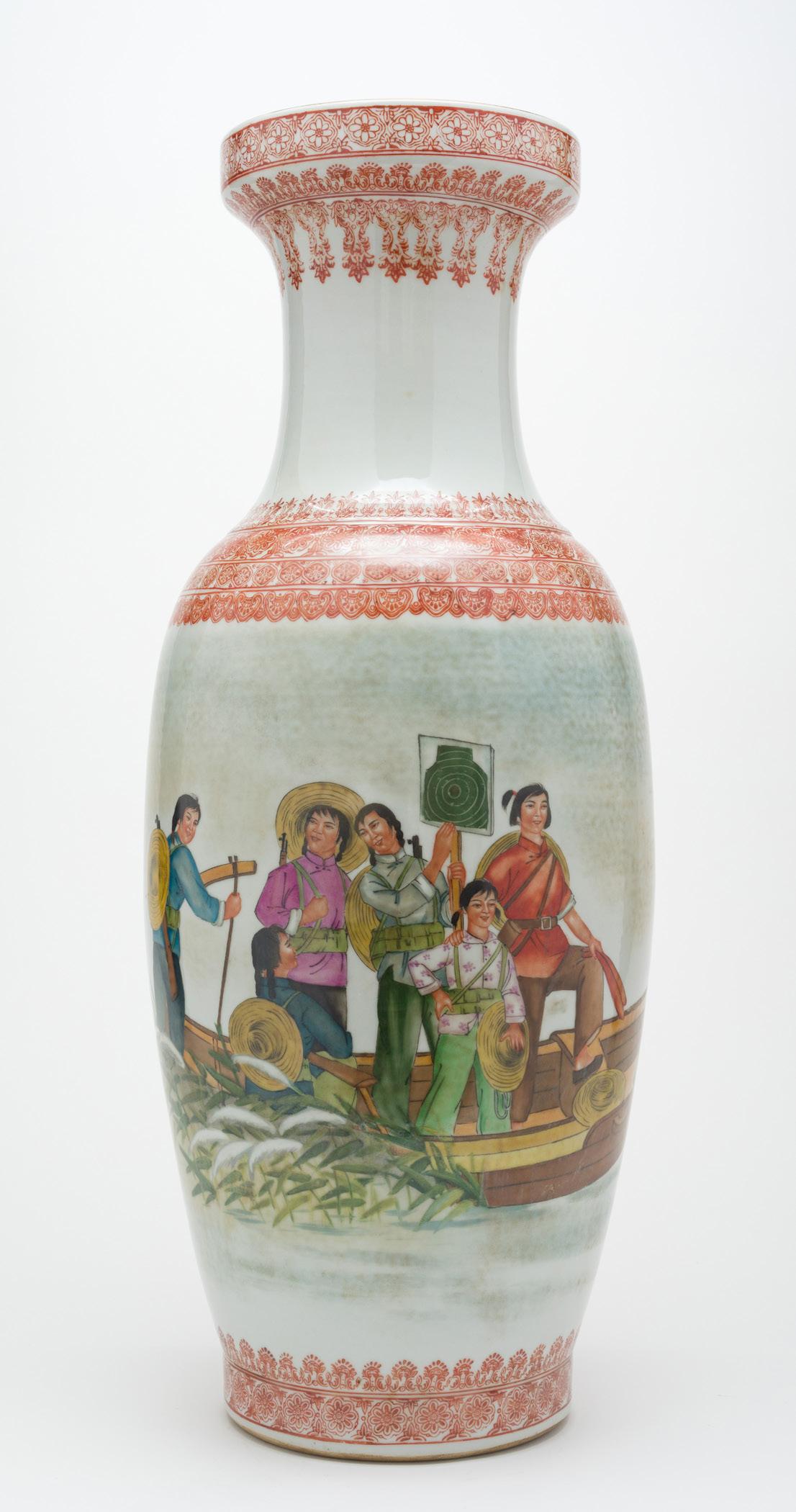

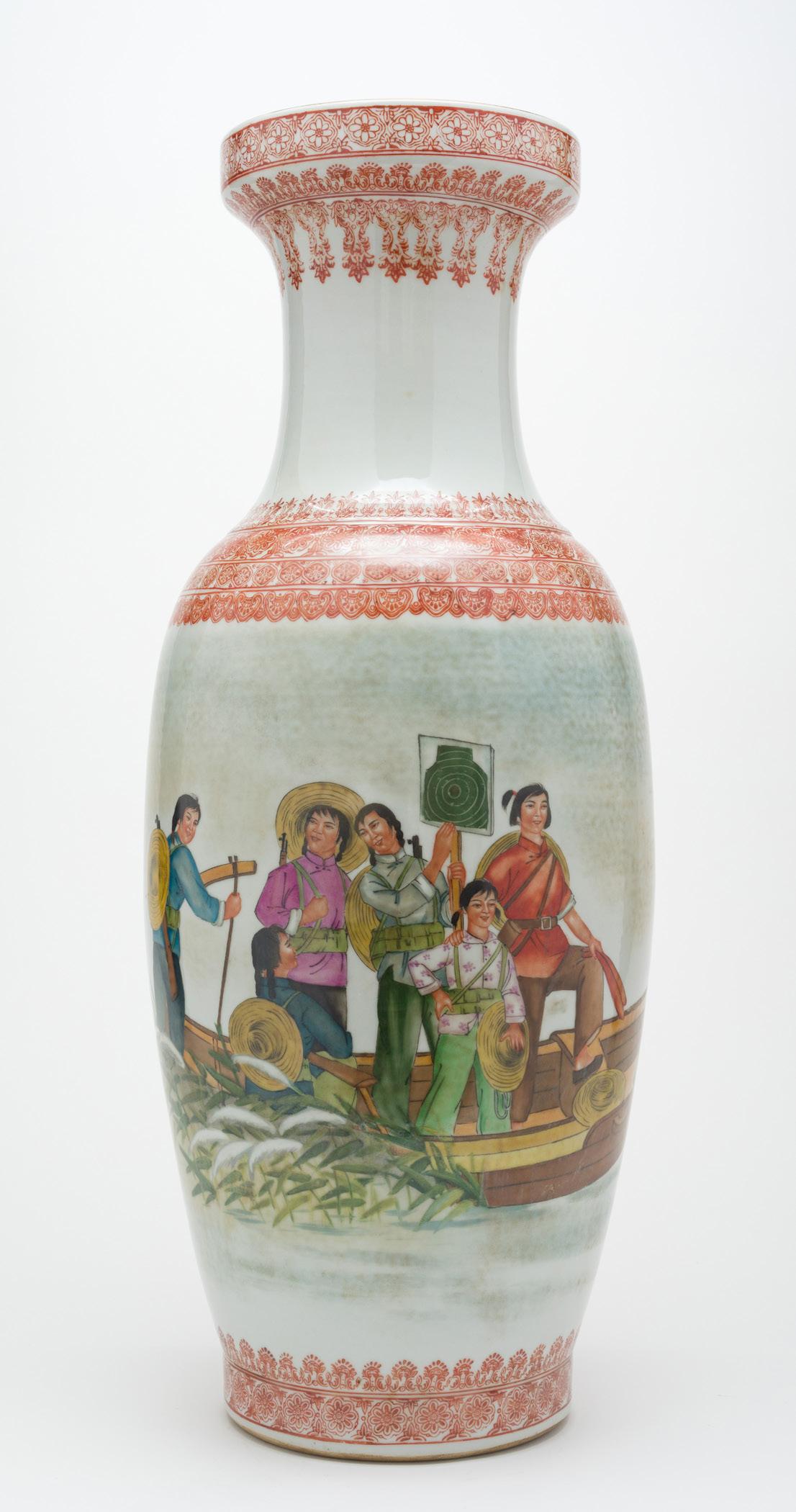

Zhang Wenchao 章文超

Returning from Target Practice 打靶归来

1969 Porcelain Private Collection

This ceramic not only celebrates the importance of military activity during the Cultural Revolution, but also foregrounds the new role of women in Communist society. Young peasant women, dressed in colorful local costume, travel on a small boat along a reedy riverbank. The happy scene contrasts with its military content, as the young women are all armed with rifles and one holds a target for shooting practice. The back of the vase is inscribed with a quote from Mao, which reads: “Chinese sons and daughters have great fighting will, they do not love fine clothes but love weapons.” After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Communist Party sought to overturn the patriarchal practices that were inherent in traditional Chinese society. Women, who had previously been relegated to the home, were actively encouraged to enter into public life, pursue careers, and even join the military.

Ministry of Light Industry Ceramic Research Office 轻工业部陶瓷研究所

Down with Factionalism and Strengthen Party Spirit 打倒派性增强党性

1969 Porcelain Private Collection

Two workers, to the left and right, and a People’s Liberation Army soldier, in the center, hold up copies of The Little Red Book. Originally published in 1959 for army use, this book of Mao’s quotations was widely disseminated during the Cultural Revolution; by 1979, over one billion official copies of the book had been printed. People from all walks of life were expected to know the Chairman’s writings by heart, as schools, factories, farming communes, and army units organized Mao Zedong Thought study groups. The back of the vase urges viewers to “beat down factionalism, strengthen party spirit,” and to “unite against the common enemy.”

34

34

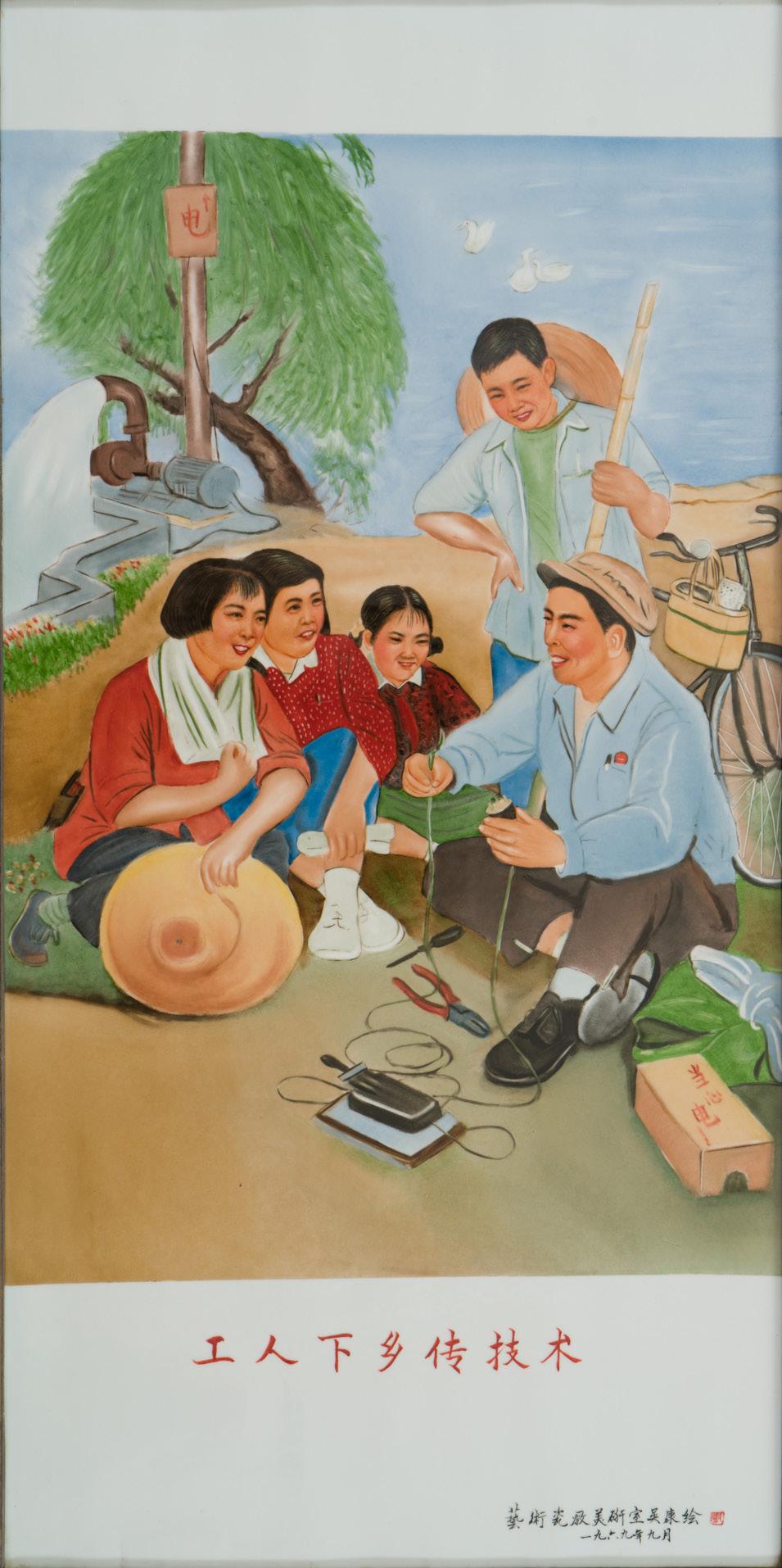

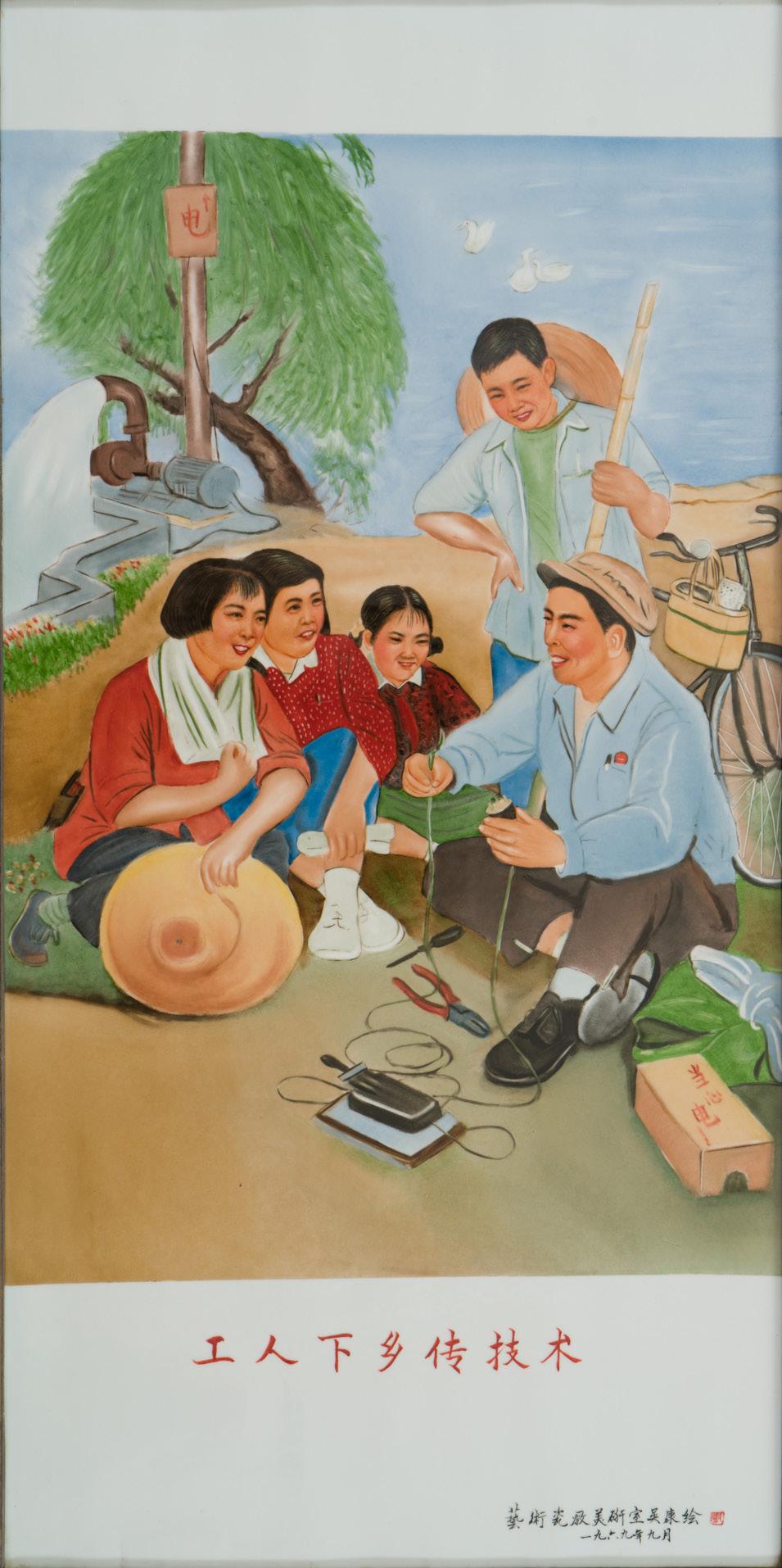

Wu Kang 吴康

Workers Go to the Countryside to Spread Technology 工人下乡传

技术 1969

Porcelain Private Collection

Wu Kang 吴康 Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the Founding of the People’s Republic of China 庆祝中华人民

Porcelain Private Collection

Wu Kang 吴康 Night Raid Reconnaissance 夜袭侦察 1966 Porcelain Private Collection

These works come from a set of plaques that celebrates the various contributions of the workers, peasants, and soldiers to Chinese society. The first features a scene of military life: soldiers wading in a pool of water as part of a night reconnaissance mission. The highly decorative nature of the plaque—with lush lotus leaves and delicate white flowers—contrasts with its subject matter and even romanticizes military life. The second depicts a worker installing electricity in a farming community. In this plaque, the peasants have both electricity and running water, modern conveniences that highlight the improved quality of life for rural communities under the Communist Party. The final plaque features a factory worker, a peasant, and a People’s Liberation Army soldier—citizens who were considered the backbone of the nation—celebrating the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

35

共和国成立二 十周年 1969

35

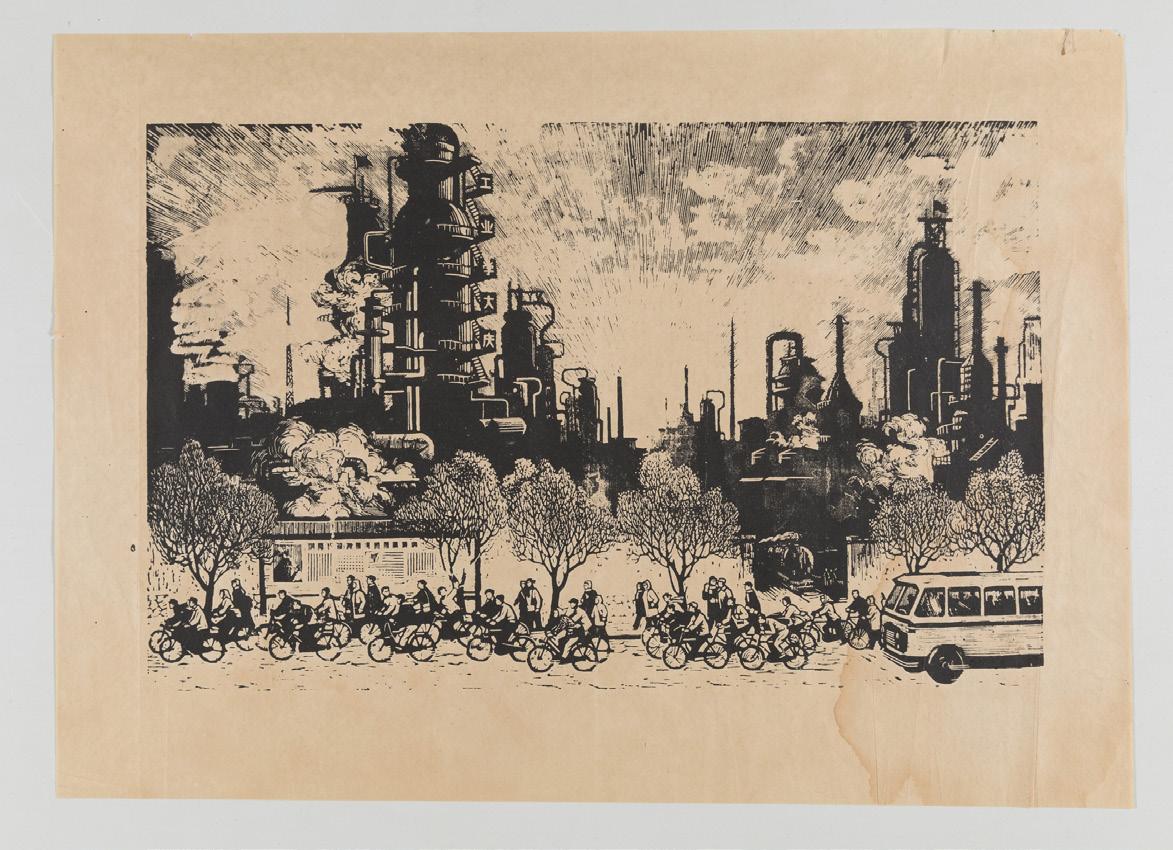

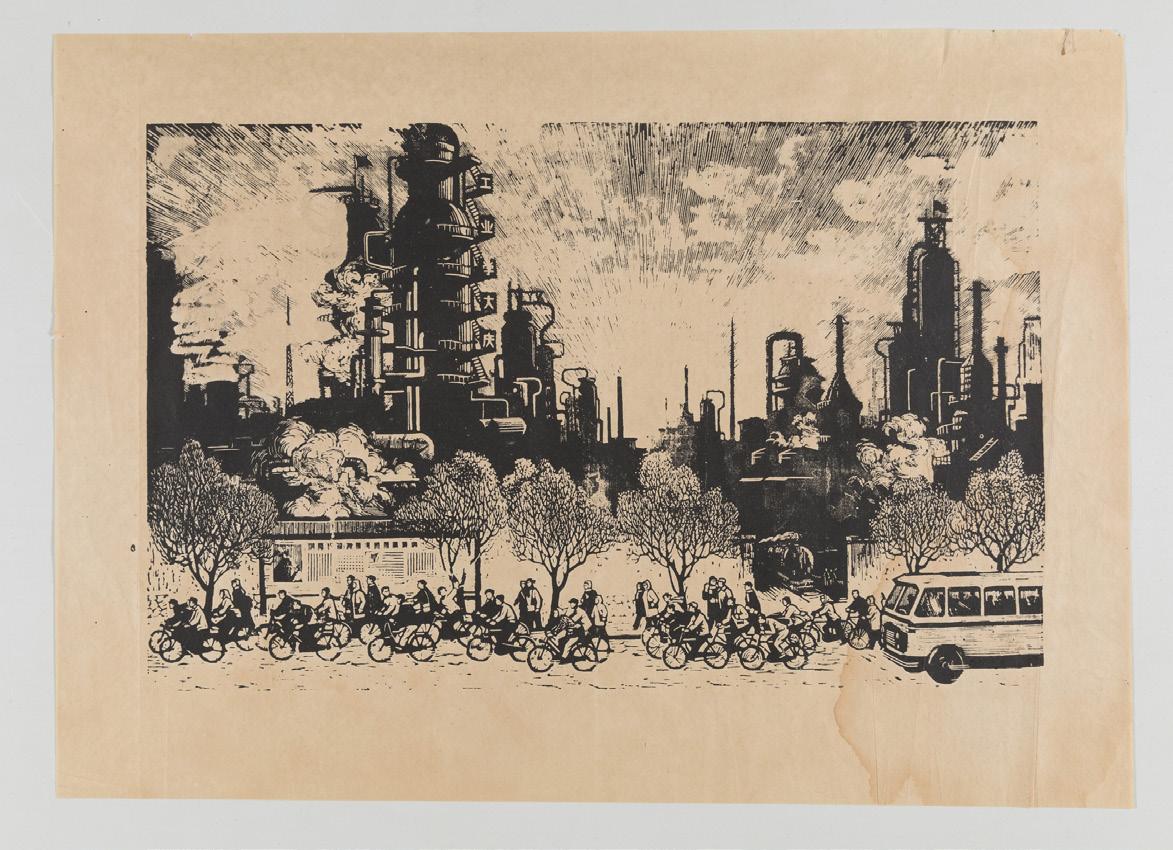

Sui Guimin 隋贵民 Industry Learns from Daqing 工业学大庆

1976

Woodblock print Private Collection

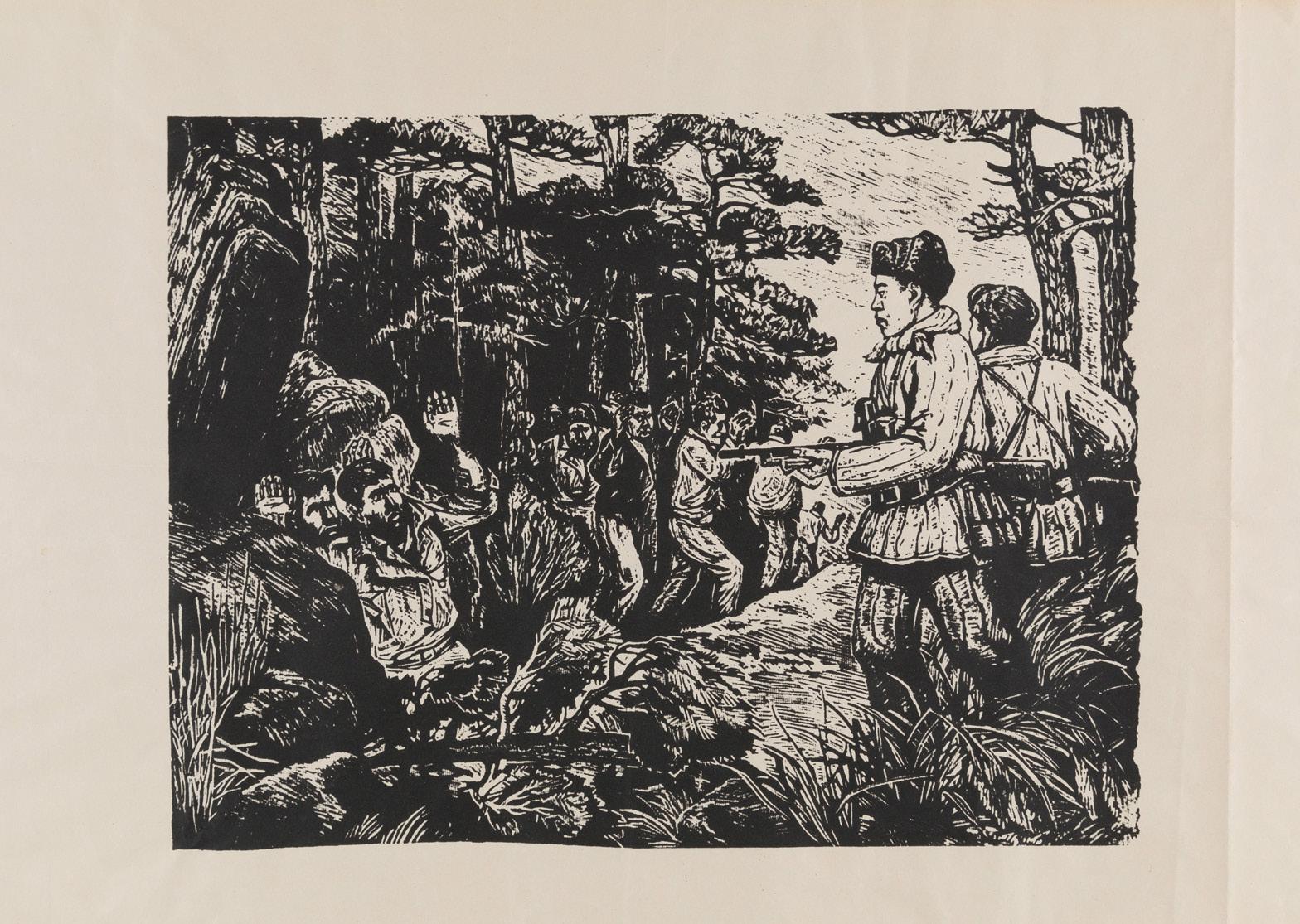

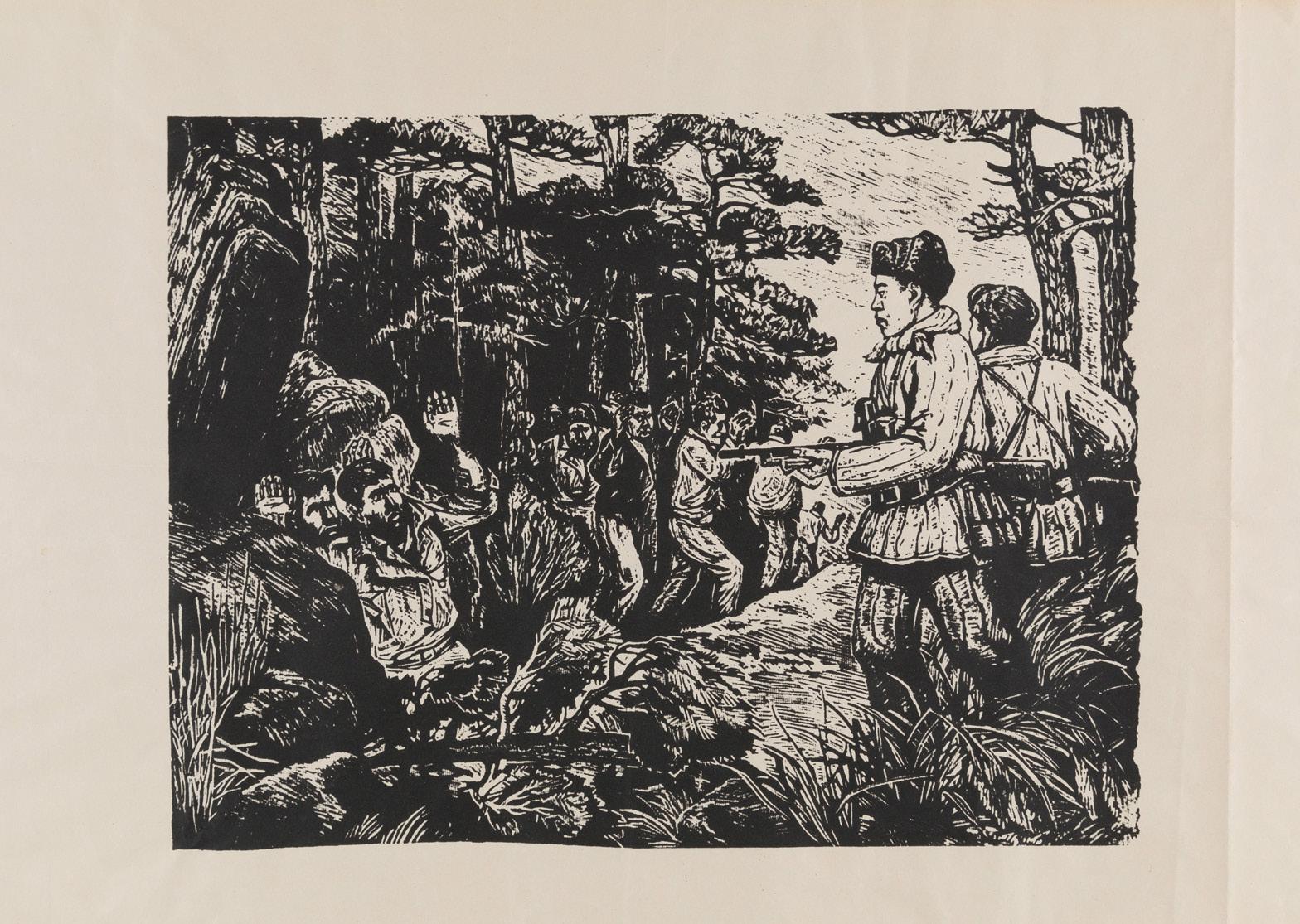

Zhao Yannian

赵延年

Chinese Volunteer Army 中国人民志愿军 1966-1976

Woodblock print Private Collection

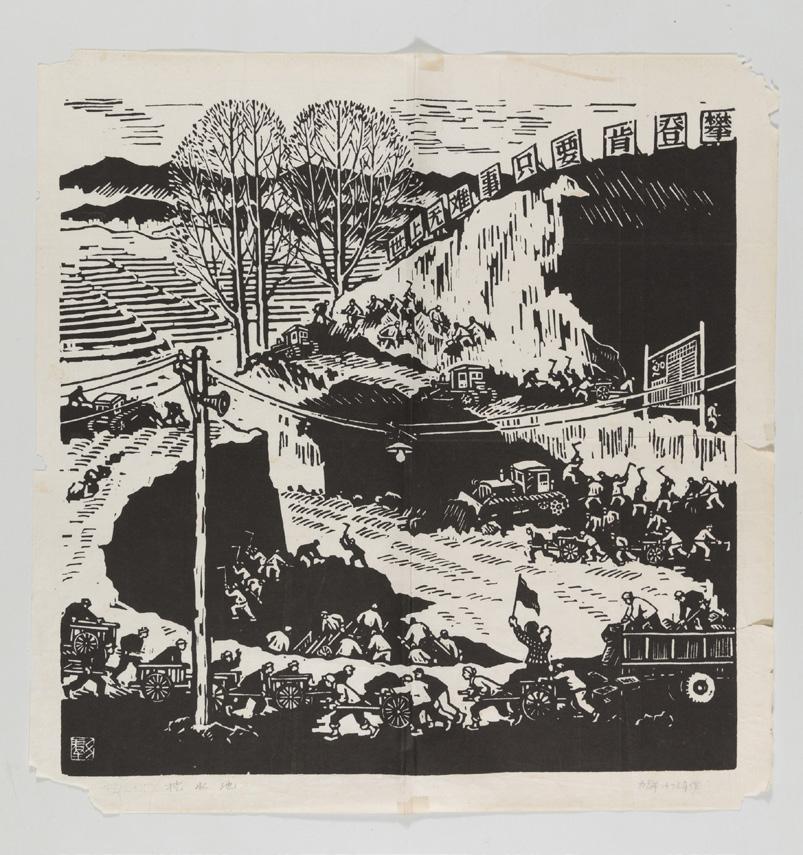

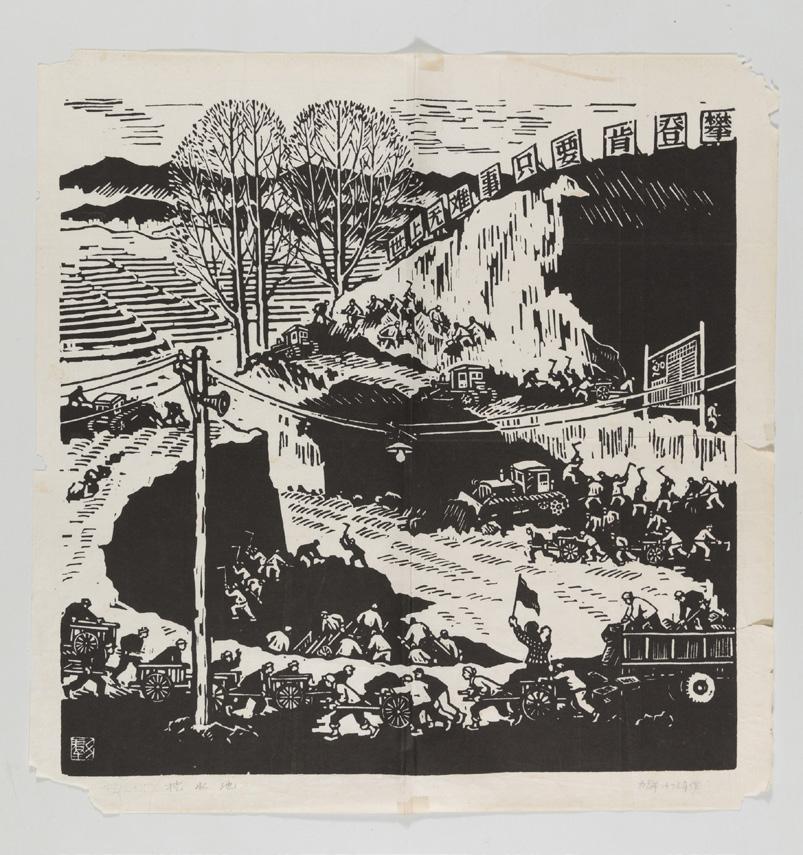

Li Qun 力群

Excavating a Pond 挖水池 1976

Woodblock print Private Collection

These woodblock prints celebrate the achievements of China’s workers and soldiers. The first, by the famous woodcut artist Li Qun, depicts a large construction scene with numerous workers and machines excavating the site. The sign mounted above reads: “Nothing in the world is hard if you dare to scale the heights,” a phrase taken from Mao’s 1965 poem “Reascending Jinggangshan.” The second depicts a large oil refinery, highlighting the nation’s industrial development, particularly its oil production. In the last print, soldiers from the People’s Volunteer Army capture enemy troops— possibly Americans—hiding in the forests; two of them stand at guard, with guns pointed at two men emerging from the underbrush. The People’s Volunteer Army was an offshoot of the People’s Liberation Army that was formed during the Korean War (1950-1958). To avoid entering into an open war with the United States and the United Nations, who aided South Korea, China sent soldiers supporting North Korea under this separate branch.

36

36

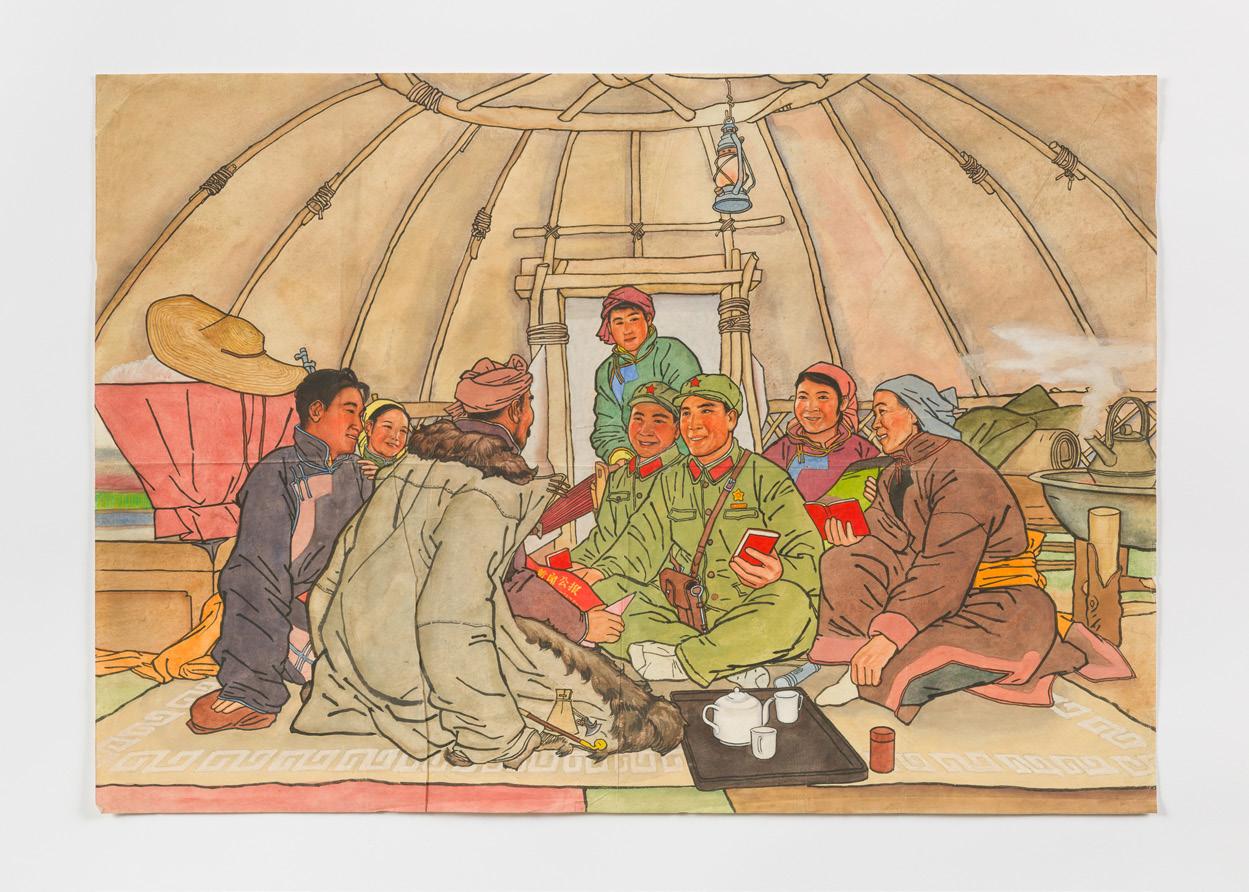

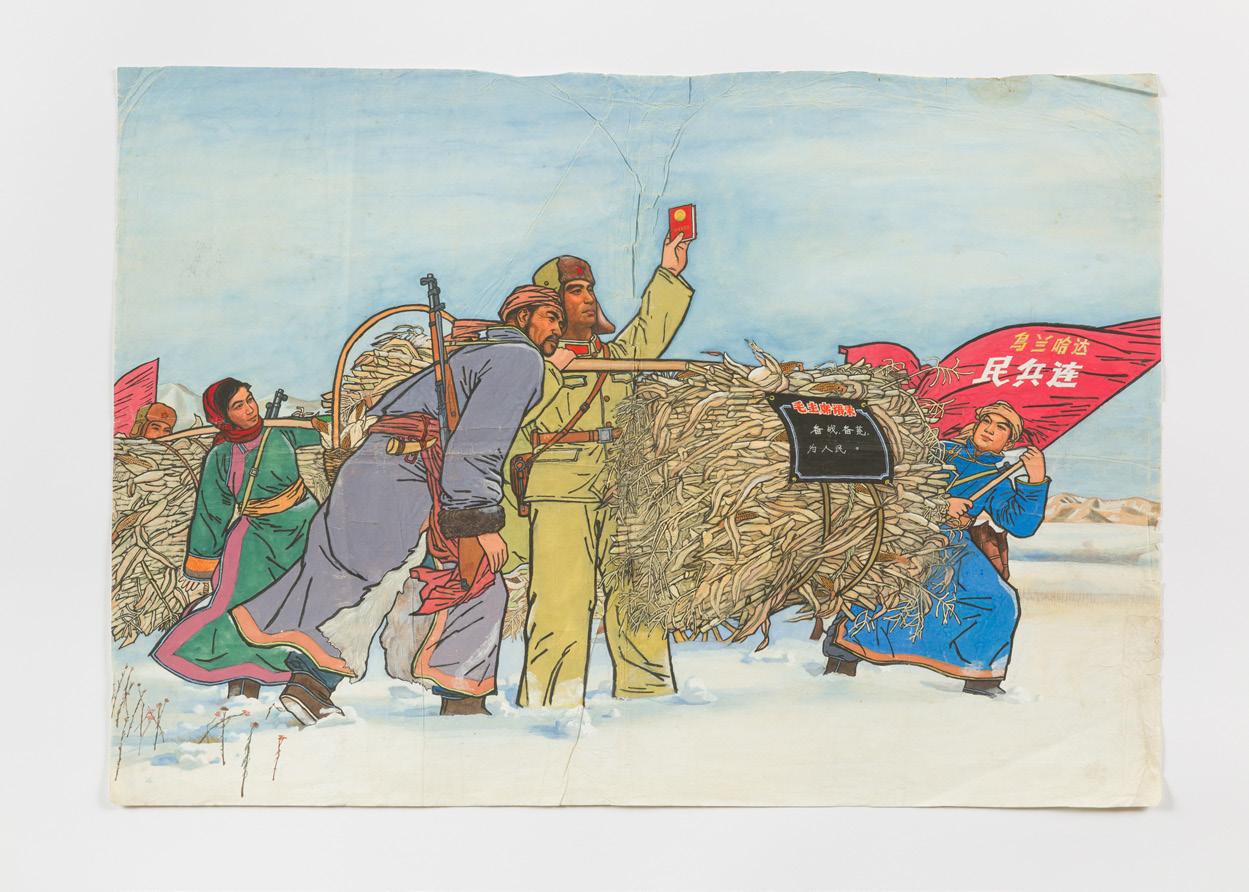

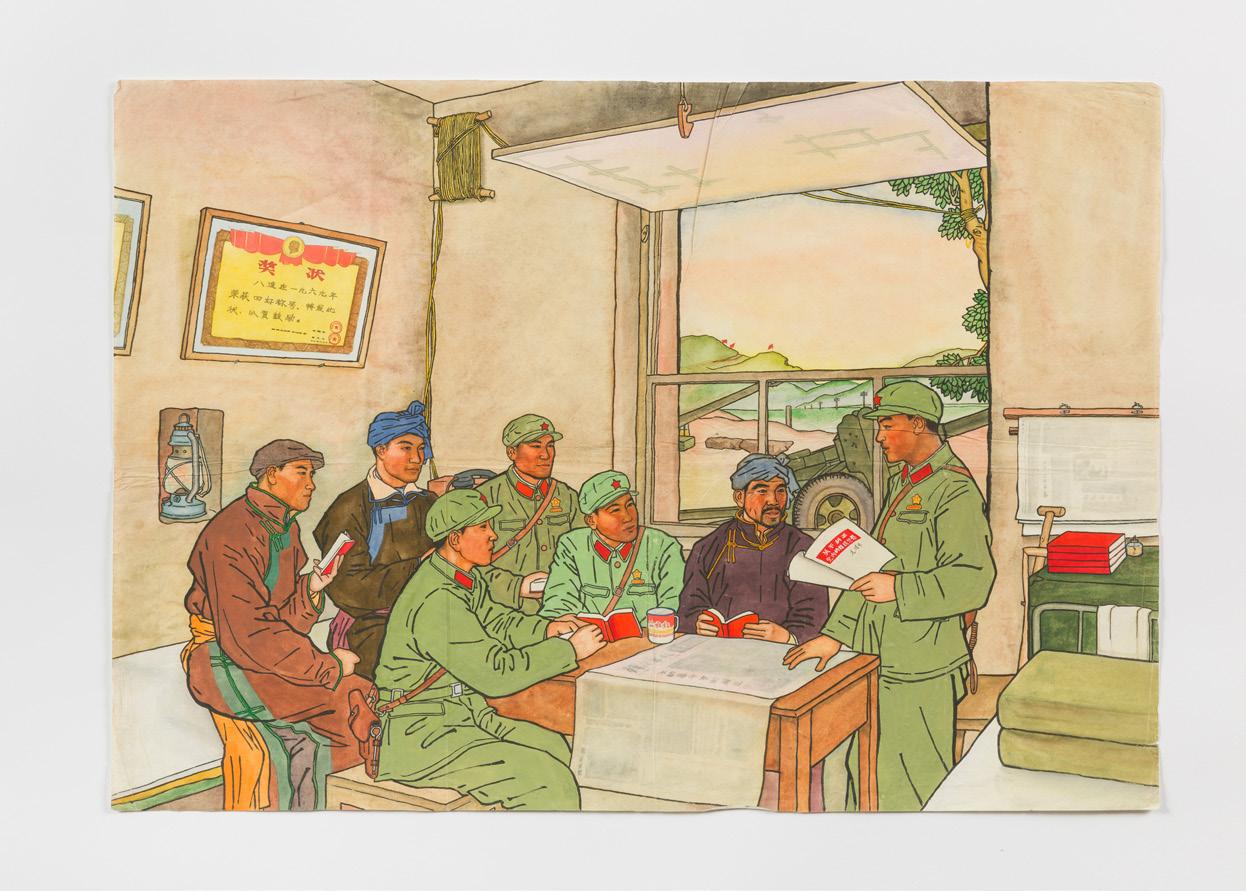

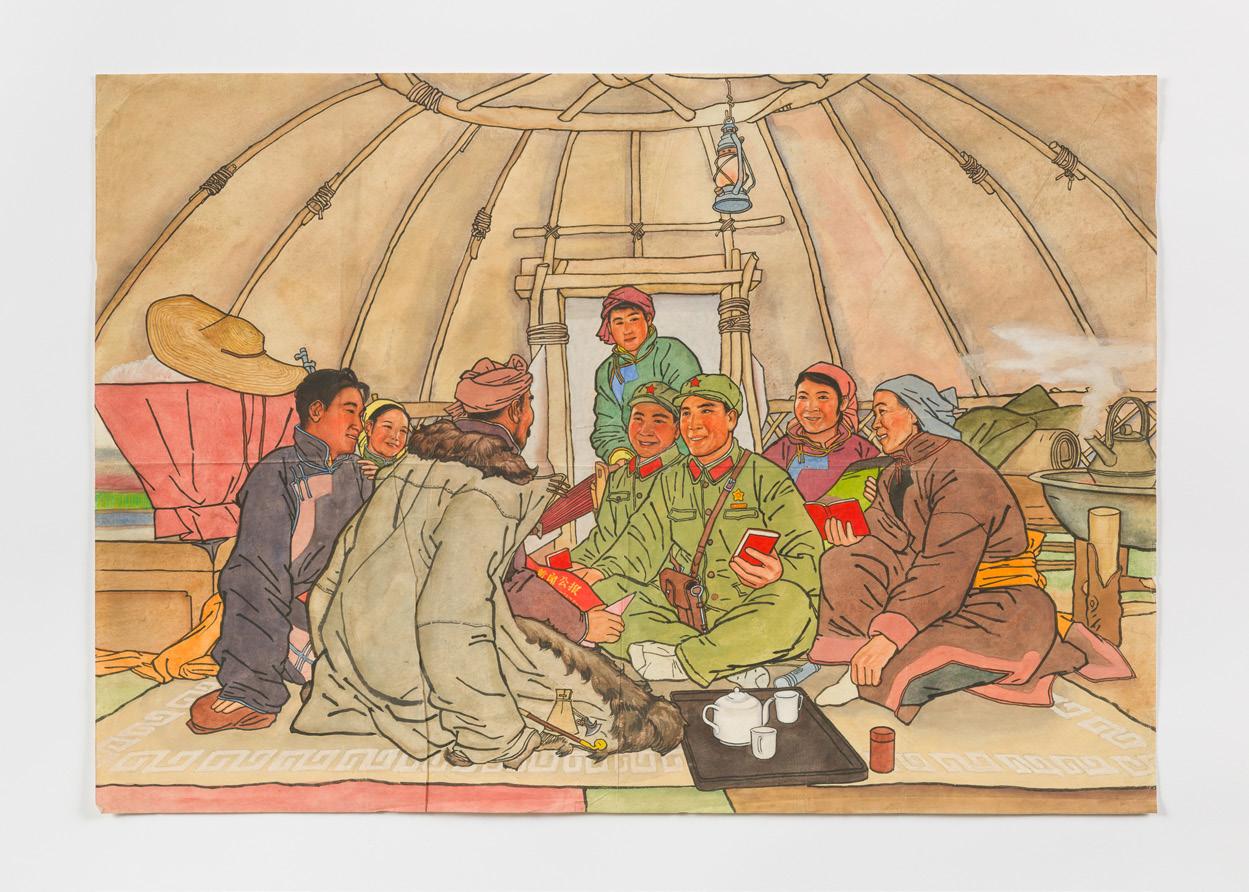

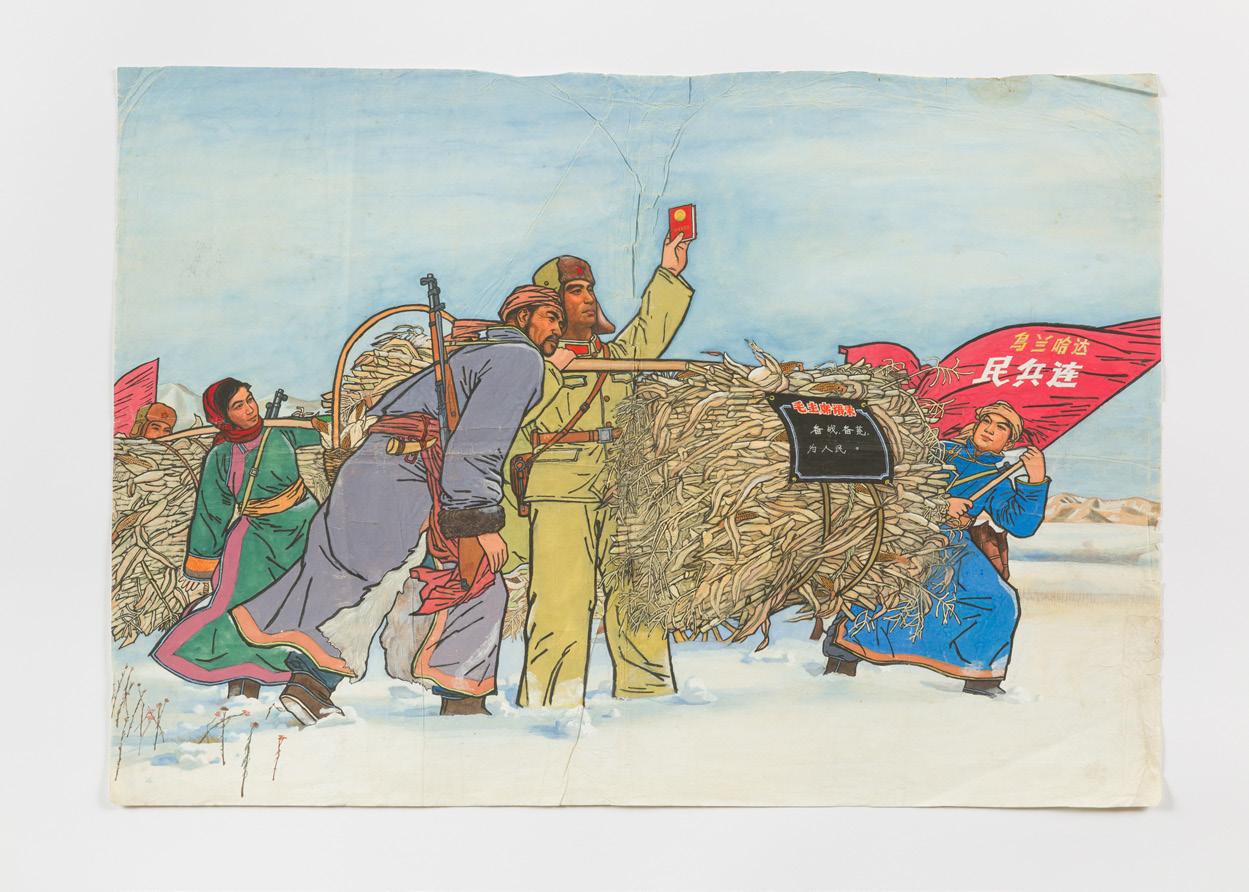

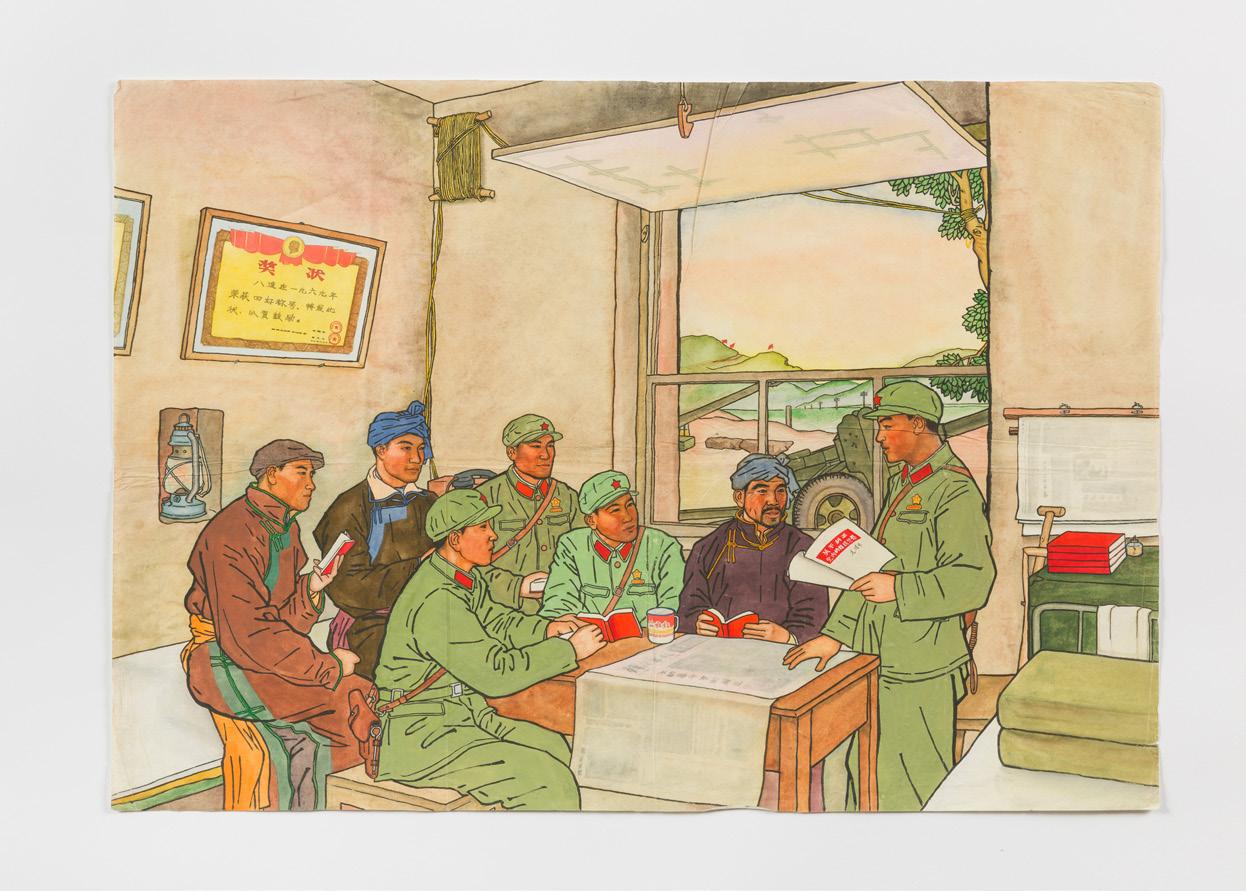

People’s Liberation Army Soldiers and Mongolian Farmers 中国人民解放军和蒙古农民

20th century Gouache on paper Courtesy

of Ethan Cohen

These gouaches—paintings made with opaque watercolor—are painted in a style that draws from traditional Chinese folk paintings and New Year’s prints (年 画), featuring bright colors and flattened shapes with simple black outlines. However, the faces of the figures are painted with detail and careful modeling to create a sense of realism and to highlight their expressions. Works such as these would have served as models for posters printed by government agencies; because of their fragile nature, very few of these original paintings remain. The set of gouaches depicts soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army working with Mongolian farmers in the Wulan Hada region of the autonomous province of Inner Mongolia. The first image features a soldier helping Mongolian farmers—recognizable by their ethnic dress—transport large bundles of corn across a snowy landscape. In the front of the group, a man carries a large flag from the Wulan Hada militia company. The second gouache shows a happy, convivial scene with soldiers sitting with Mongolian men and women inside a yurt, a traditional Mongolian dwelling. The soldiers teach the farmers political theory from Little Red Book, while the Mongolians welcome the soldiers by offering them tea. The last image on the right depicts soldiers teaching Mongolian men political theory in the interior of a militia office. A window looks out onto military equipment and powerlines in the distance; this official background—with its trappings of modernity, including newspapers—contrasts with the traditional domestic setting of the yurt in the previous painting.

37

37

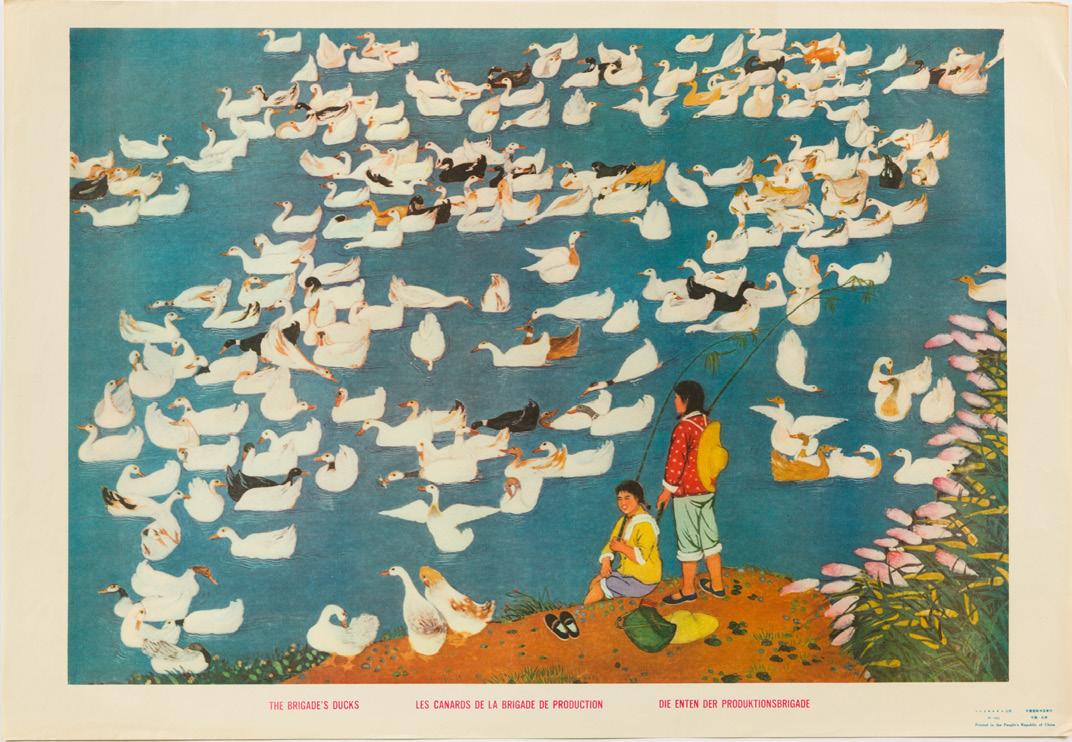

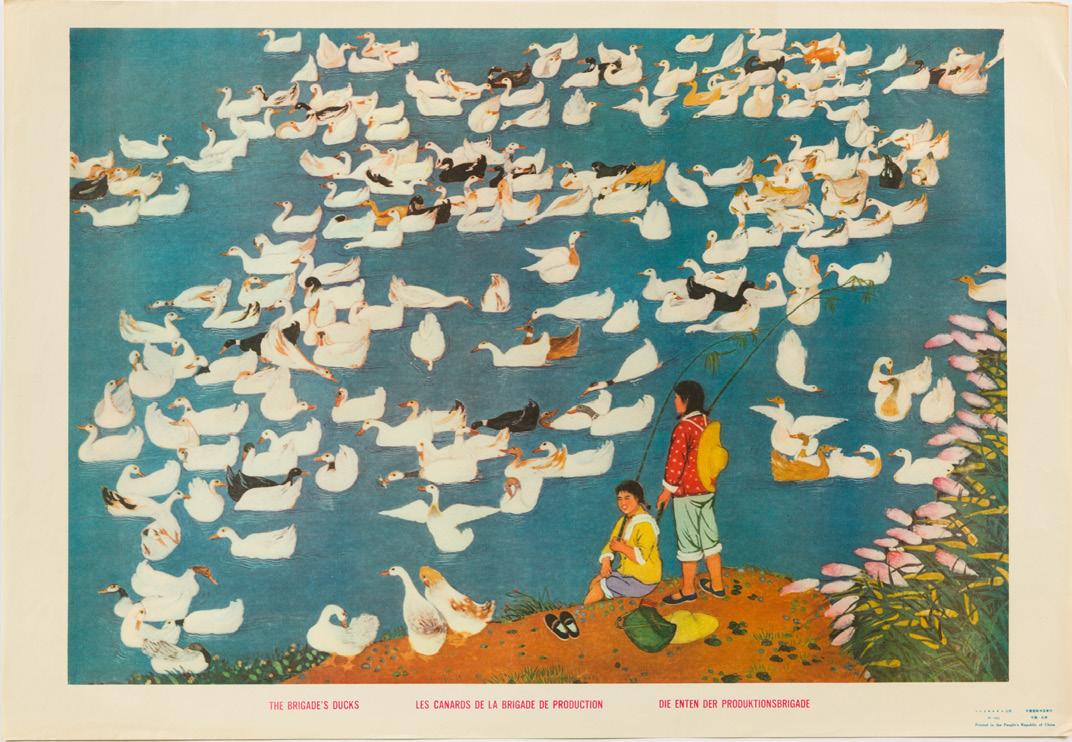

Li Zhenhua 李振华

The Brigade’s Ducks 大队鸭群场

1973 Poster

Collection Wende Museum, donated by David E. James

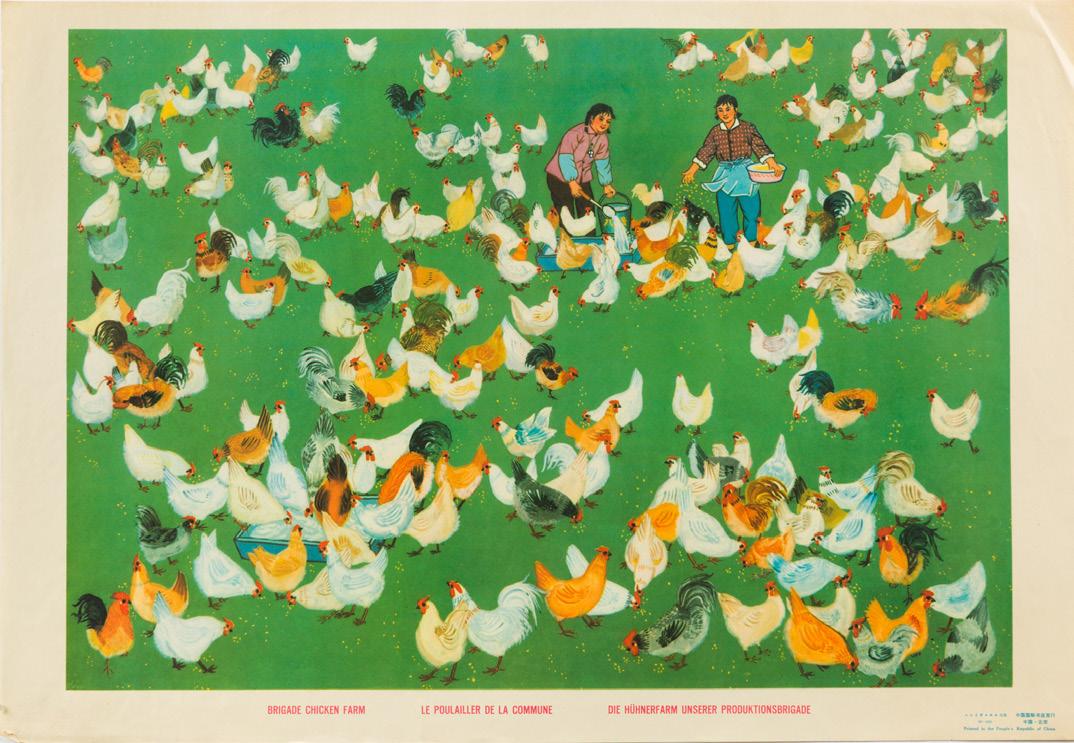

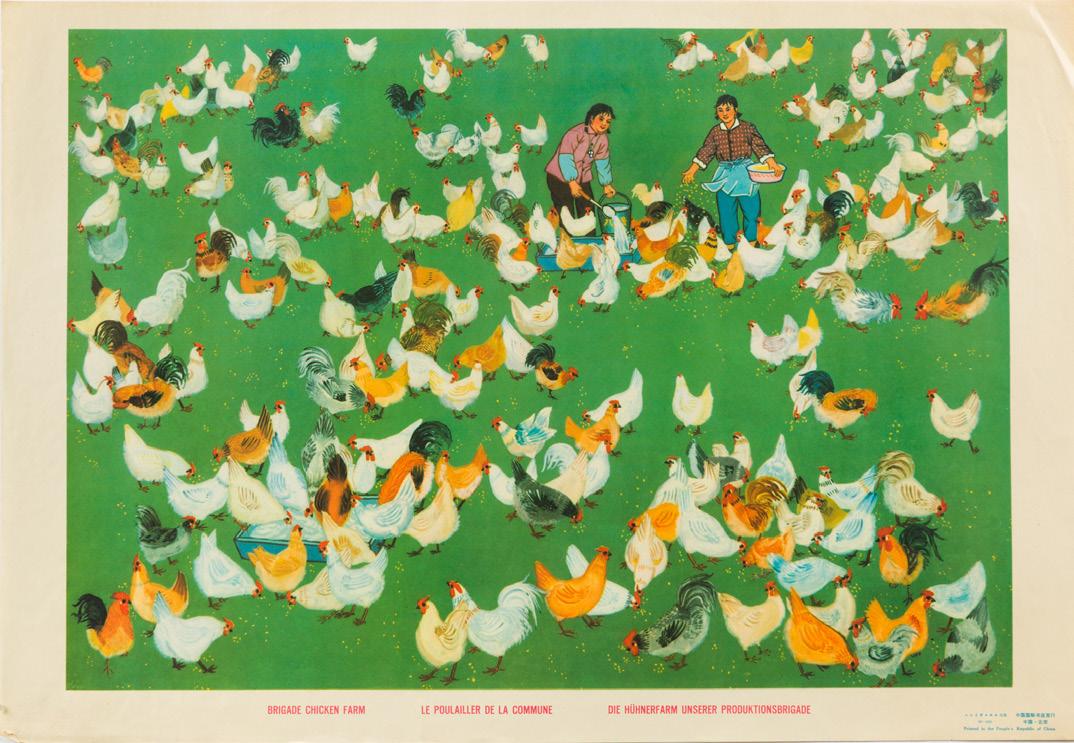

Ma Yali 马亚利 Brigade Chicken Farm 大队养鸡场 1973 Poster

Collection Wende Museum, donated by David E. James

These two posters by Li Zhenhua and Ma Yali are examples of peasant paintings from Huxian in the Shaanxi province, a region known for this type of artwork. They have all the characteristics of Huxian peasant painting: the naive style, happy agricultural subject matter, decorative use of patterns, and bright colors, all of which drew from local folk-art traditions. With their multitude of ducks and chickens, the posters highlight the bounty of the commune and the prosperous living conditions in the countryside provided by the Chinese Communist Party. As part of Mao’s policy to popularize the arts, peasants in rural areas across China were encouraged to create works of art, including murals or paintings that would be published as posters. Amateur painters were held up as national examples to illustrate the spirit and creative genius of the masses. However, in reality, most works by amateur artists were touched up or redrafted by professional artists who were sent to the countryside to teach their craft.

INTERVIEWS

Twelve Years in Heilongjiang and After: An Interview with Xu Shouhu 风风雨雨十二年:徐寿虎访谈录 2019 Film

Courtesy of Dartmouth University Library

My Life as a Rusticated Youth: An Interview with Zu Yinyou 我的知青岁月:祖印友访谈录

2018

Film

Courtesy of Dartmouth University Library

38

38

THE MODEL

In traditional Chinese culture, models—exemplars that could be imitated or replicated—had served as important pedagogical tools in both scholarship and artistic practice. Students were encouraged to follow the behavior of ancient sages, such as Confucius, while painters copied famous masterpieces to demonstrate artistic prowess and erudition. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the Chinese Communist Party adopted these pedagogical techniques, but replaced the ancient sages and classical painters with Communist figures that were to be emulated, such as the courageous oil field worker Wang Jinxi or the Red Guard martyr Jin Xunhua. These model figures were praised for their devotion to Socialism, tireless work ethic, and selflessness. During the Cultural Revolution, their images were everywhere—in posters, books, and ceramics—telling their stories, celebrating their actions, and urging viewers to imitate their exemplary lives.

Red Flag Canal 红旗渠 1966-1976

Porcelain

Private Collection

A musical ensemble, featuring drums, cymbals, and a trumpet, celebrates the completion of the Red Flag Canal, whose waters flow metaphorically in a brilliant white stream. The Red Flag Canal (1960 -1969) was a large-scale irrigation project in Henan Province to bring water to drought-prone farmland. After its completion, it was considered one of the great achievements of Chinese workers. Along with the model projects of the Daqing oilfield and Dazhai village, it served as an example of how the Chinese people, by using Mao Zedong Thought, could control nature and bend it to their will.

39

39

“Ironman” Wang Jinxi “铁人”王进喜 1966-1976

Porcelain Private Collection

Wang Jinxi, known as the “Iron Man” for his tireless work ethic and selfless dedication to promoting Chinese industry, strides resolutely forward against a strong wind. He was the leader of the No. 1205 drilling team at the Daqing oilfield, the first to strike oil, and he quickly rose through the ranks. By 1960, his reputation had spread nationally as Chinese citizens were urged to learn from the Iron Man’s exemplary behavior. However, at the start of the Cultural Revolution, he was branded as a follower of the purged Party leader Liu Shaoqi and persecuted. Wang was rehabilitated by Premier Zhou Enlai and in 1967 was made a national model worker.

Zhang Jian 章鉴

Immortal Hero Qiu Shaoyun in the Fire 烈火中永生的英雄邱少云 1965

Porcelain Private Collection

Qiu Shaoyun was a member of the People’s Liberation Army and later joined the Chinese Volunteer Army during the Korean War. The dramatic moment illustrated here commemorates his heroic sacrifice. In 1952, during the battle for Hill 391, Qiu and his unit mates used twigs and grass to camouflage themselves as they slowly moved toward the enemy. Qiu was caught in a brushfire after a bomb, dropped by an enemy plane, exploded nearby. Rather than escape and give away the position of his fellow soldiers, Qiu remained in place and burned to death. He was declared a hero, and throughout the Cultural Revolution, his image was used to encourage selfless behavior.

40

40

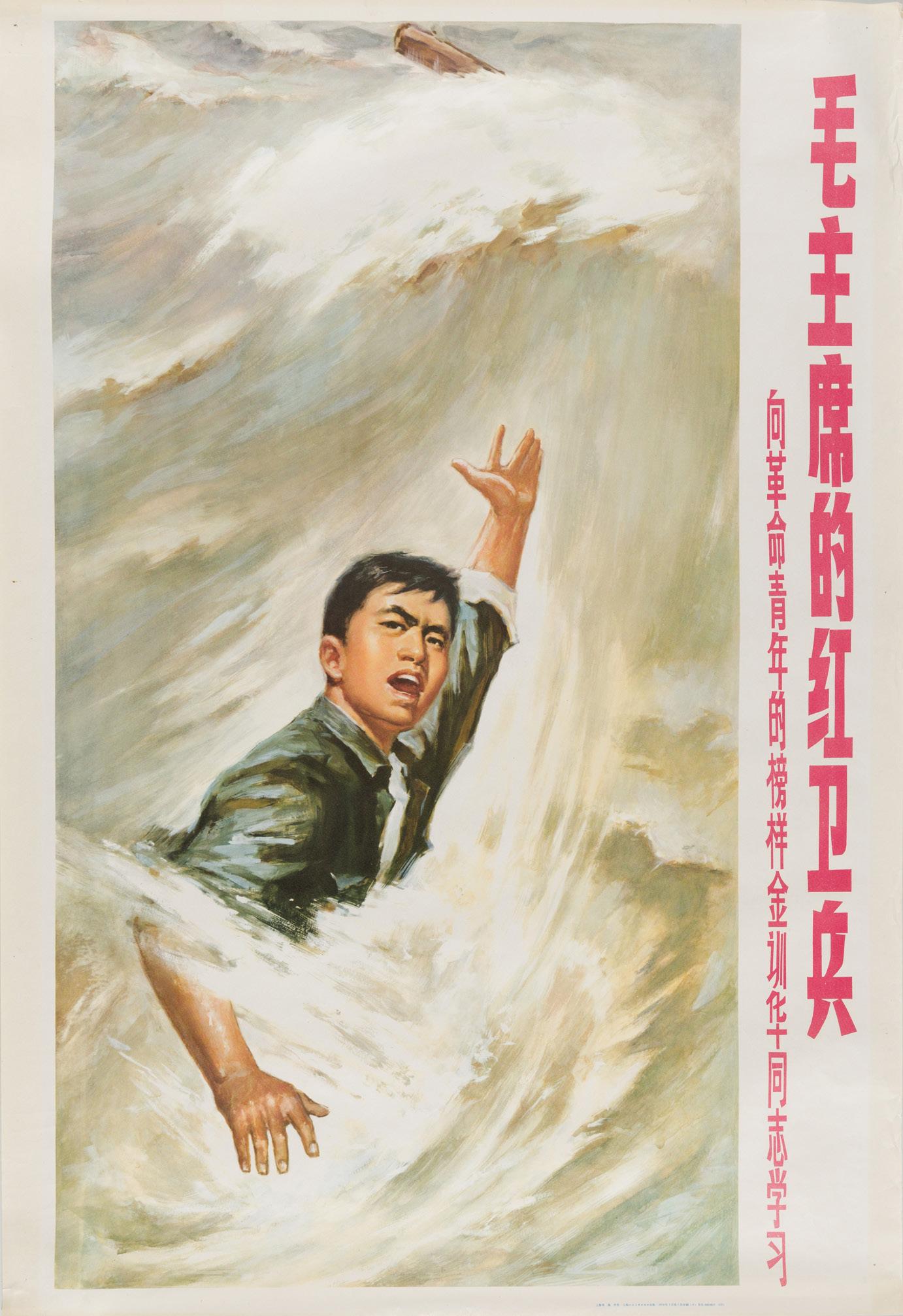

Xu Chunzhong and Chen Yifei 徐纯中 和 陈逸飞

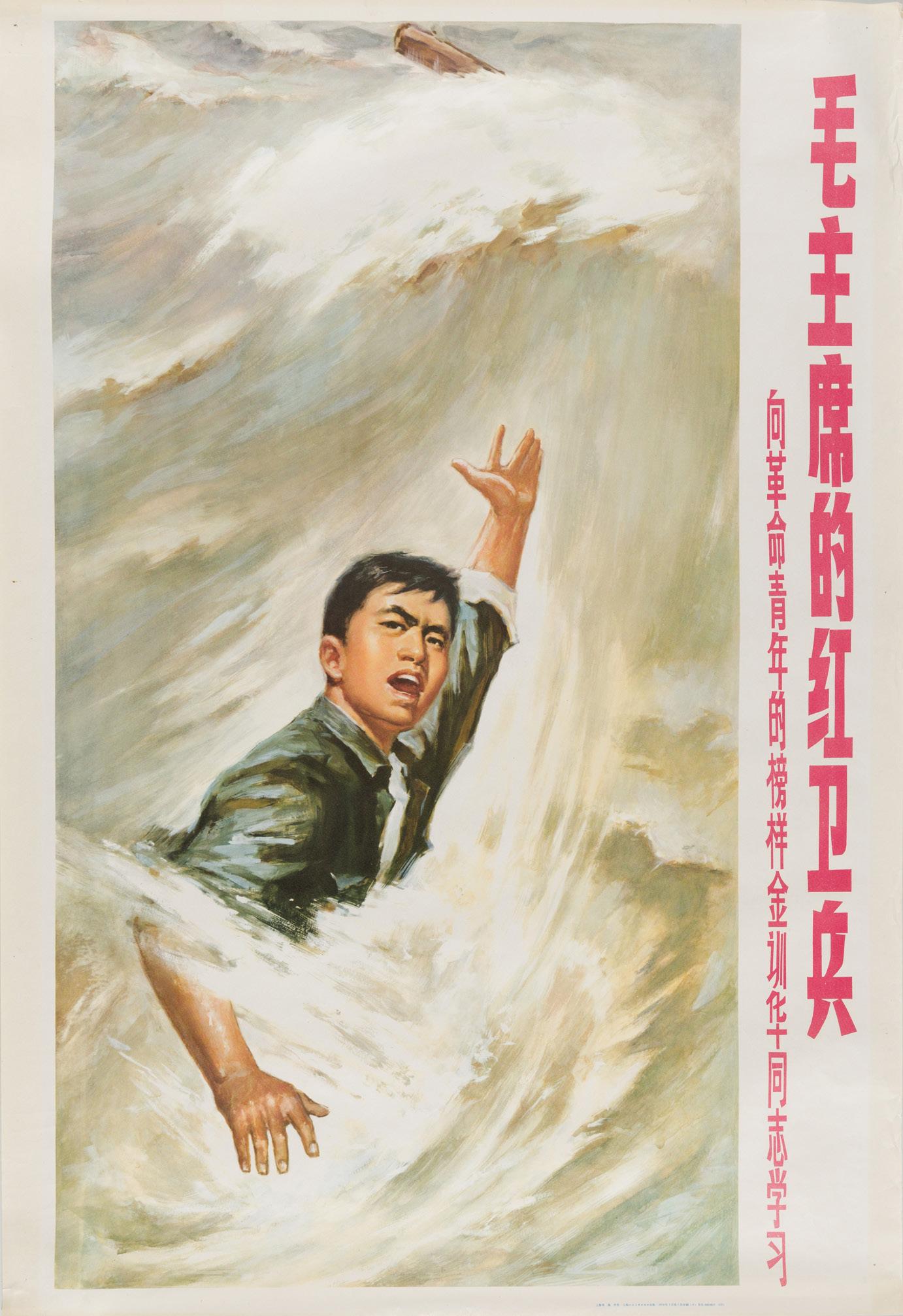

Chairman Mao’s Red Guard: Learn from the Example of the Revolutionary Youth Comrade Jin Xunhua 毛主席的红卫兵:向革命青年的榜样金训华 同志学习 1970 Poster Private Collection

Jingdezhen Art Porcelain Factory 景德镇艺术瓷厂

Learn from the Example of the Revolutionary Youth Comrade Jin Xunhua 向革命青年的榜样金训华同志学习 1972 Porcelain Private Collection

This poster and ceramic vase celebrate the contribution of the Red Guard martyr Jin Xunhua. In 1969, he was sent from his hometown of Shanghai to rural Heilongjiang as a rusticated youth. During a flood, Jin and two other young men jumped into the water to retrieve utility poles that had been swept away. These works show Jin, fearless and intent on completing his mission, engulfed in swirling waters. However, he drowned while trying to save the life of one of the other youths. After his death, Jin was held up by the government as a model of selflessness and was used to promote the “Down to the Countryside” movement, the Chinese Communist Party’s policy of sending students to rural areas to be educated by the peasants.

41

41

Wang Longfu 王隆夫

Grasp Revolution, Increase Production 抓革命促生产 1967 Porcelain Private Collection

Grasp Revolution, Increase Production 抓革命促生产 1960s Poster Private Collection

This poster and ceramic plaque celebrate the arts as part of the revolution. They offer a rare glimpse into the actual process of making art during the Cultural Revolution, albeit highly idealized. Here, we see a ceramic painter in her bright and airy studio; she works on a large, decorative urn painted with a landscape. Two young women, likely fellow artists, look on while a supervisor in uniform inspects the artist’s work. Some of the paintings on the finished ceramic pieces in the front of the composition are recognizable: one depicts peasants in the field, another features young children in a field of sunflowers, while a third shows a scene from the model ballet, The Red Detachment of Women. The ceramic plaque, which was made after the poster, illustrates the practice of copying models to create new works of art, especially in different media. These examples also illustrate the unique practice of placing recognizable images—such as the iconic scene from The Red Detachment of Women—within other images, that was especially prevalent during the Cultural Revolution.

42

42

Ministry of Light Industry Ceramic Research Office

Let’s Learn from Comrade Lei Feng 向雷锋同志学习

1966-1976

Porcelain Private Collection

A young People’s Liberation Army soldier helps a mother, accompanied by her elder child, who takes refuge under her raincoat, during a downpour, as they walk home from the railway station. He carries her younger child in one arm, and in the other, grasps a parcel. This helpful soldier is Lei Feng, who was known for his devotion to the revolutionary cause, selflessness, and good deeds for his fellow comrades. Although Lei Feng died very young at the age of 22, he left behind a diary that became the object of national study after the Chairman called on the Chinese public to learn from his example. The painting on this vase is directly based on a poster by Yang Shuntai and Wang Liyuan.

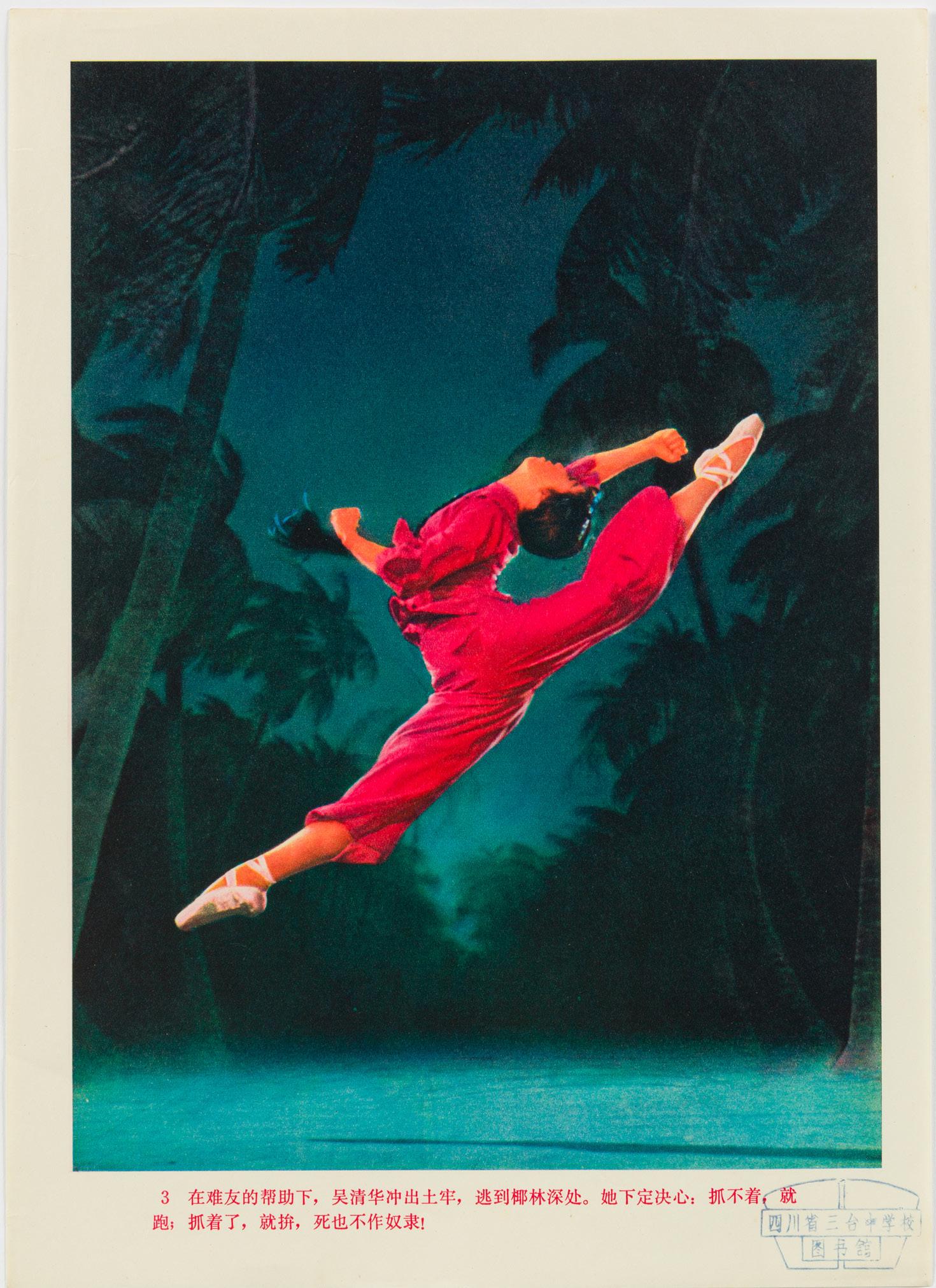

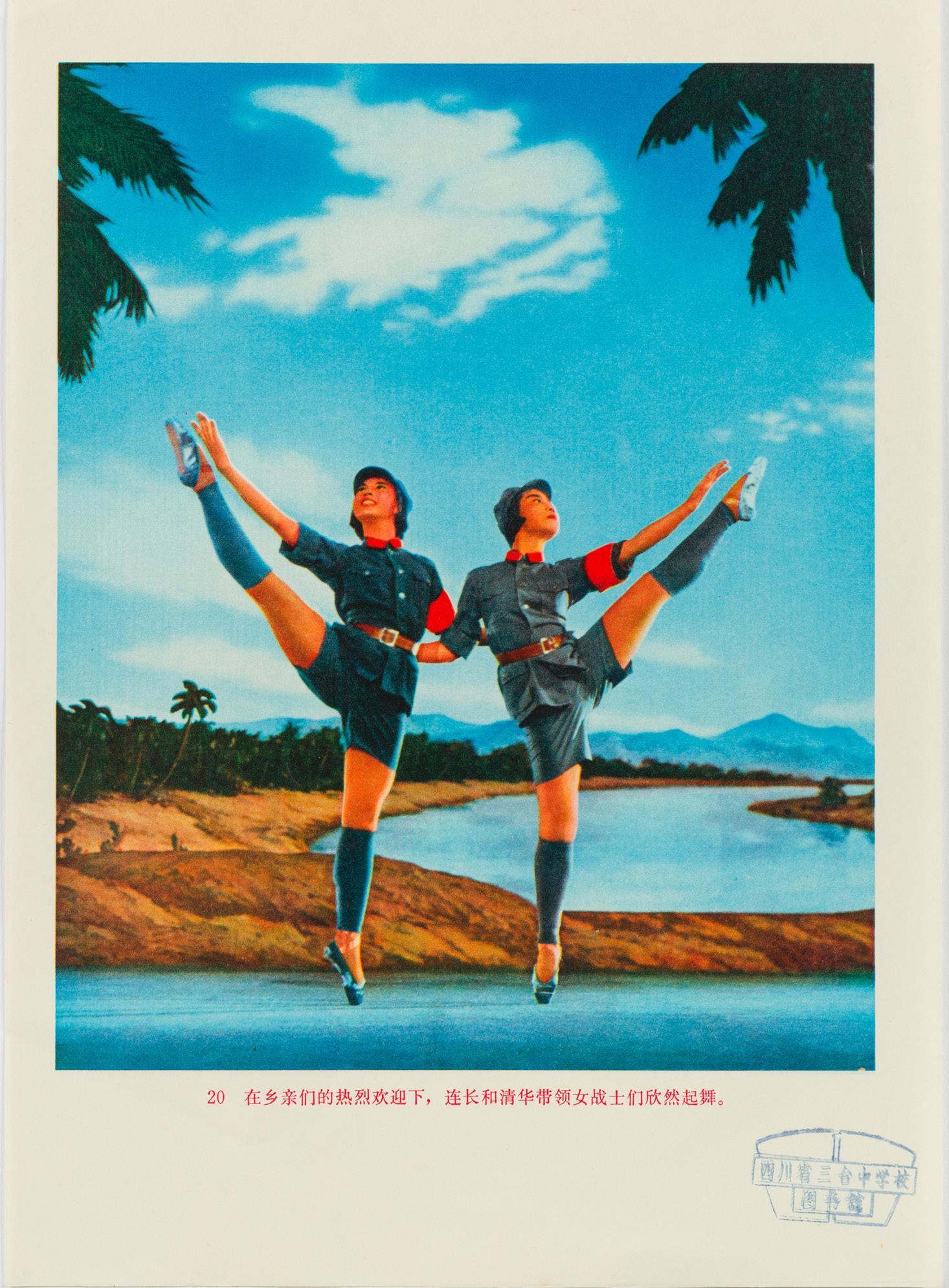

MODEL PERFORMANCES

In the performing arts, Mao’s fourth wife, Jiang Qing, was determined to reform Chinese opera and purge the arts of their feudal elements. In the 1930s, Jiang herself had been a starlet in the Shanghai film industry; although Western media was forbidden to the general populace, she loved Hollywood-style musical films, such as The Sound of Music, and understood the emotional power of these productions. In the 1960s, Jiang and a large team of directors, writers, composers, and choreographers created a set of “model performances” (yangbanxi or 样板戏), a group of operas, ballets, and symphonies with revolutionary themes. Fused with desirable elements from Western music and theater, the yangbanxi provided audiences with examples of good socialist behavior.

The model performances were codified and performed by theater troupes across the country, while their storylines and music were widely disseminated through film versions, literary adaptations, and the visual arts, including ceramics. The yangbanxi were an important shared cultural reference; not only were they known to all Chinese citizens, but oftentimes, they were the only form of entertainment available during the Cultural Revolution.

43

轻工业部陶瓷研究所

43

Wu Kang 吴康

Heroes from the Model Operas 样板戏英雄 1970s

Porcelain Private Collection

This set of plates painted by Wu Kang depicts the various heroes from model performances, with compositions drawn from film stills and posters. Each of the model performances emphasizes Maoist themes of selflessness, devotion to the collective good, and class struggle against anti-socialist figures. The first plate depicts the lead character from the opera On the Docks (海港), Fang Haichen, a Party Branch Secretary who organizes a shipment of grain to Africa. Over the course of the opera, she reveals and thwarts a plot to sabotage the shipment, and the dock workers successfully send off the grain before an impending typhoon. The second plate features Li Yuhe from the opera The Story of the Red Lantern (红灯记). Li Yuhe is a railroad worker involved in the communist underground. After he is arrested, his mother tells his daughter, Li Tiemei, about his sacrifice. In turn, Li Tiemei becomes inspired to follow a similar revolutionary path. The third plate shows the character Yang Zirong from the opera Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy (智取威虎山), which was based on true events. Yang Zirong, a soldier in the People’s Liberation Army, infiltrates and defeats a group of outlaws in Northeast China who are affiliated with the Chinese Nationalist Party. The final plate presents the heroine Jiang Shuiying from the opera Ode to Dragon River (龙江颂). Jiang Shiuying, a party secretary, leads her village in a fight against extreme drought and encourages the building of a dam to redirect water toward the dry land.

44

44

White-Haired Girl Lampstand 白毛女登台

1966-1976

Porcelain

Private Collection

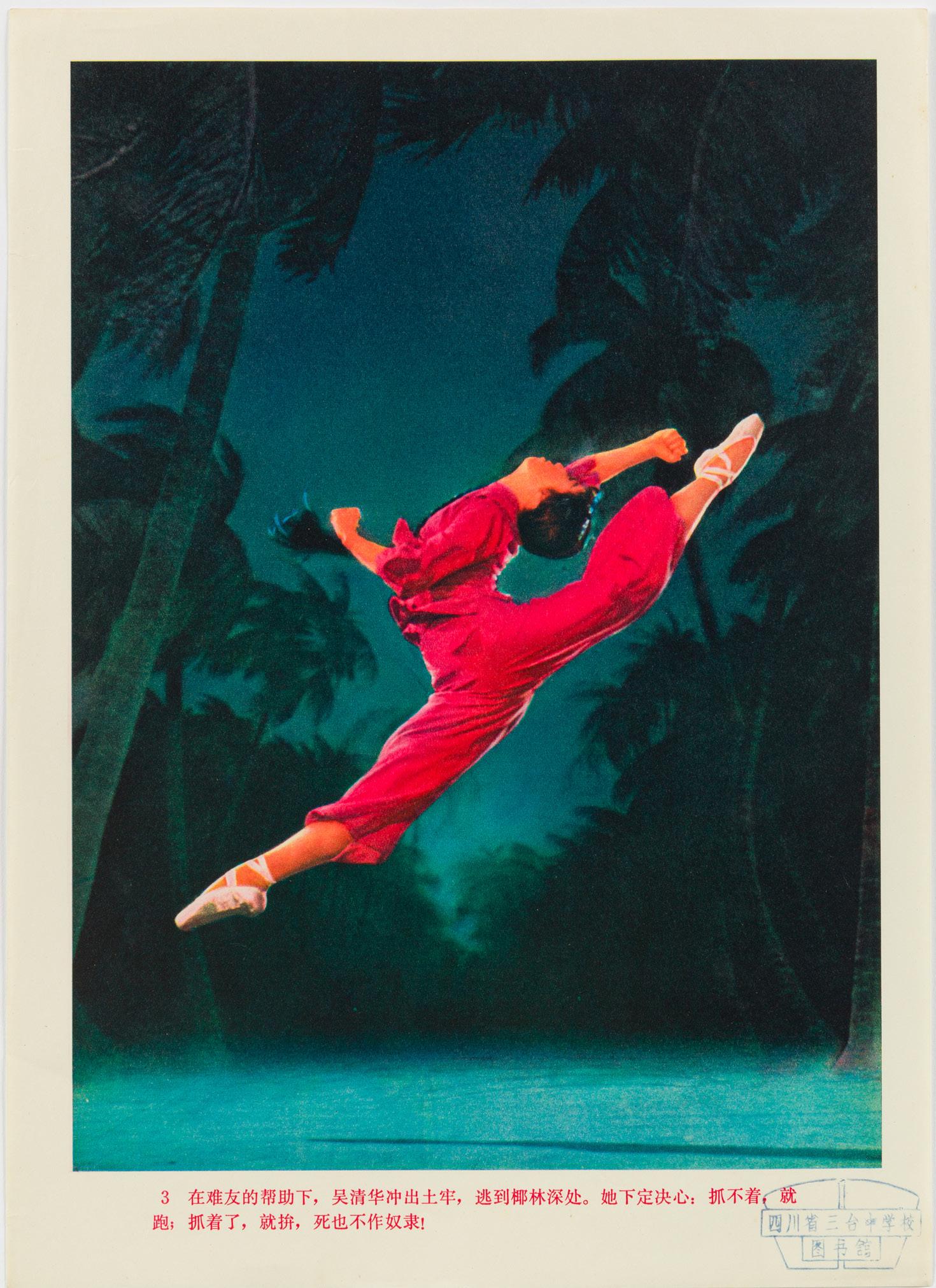

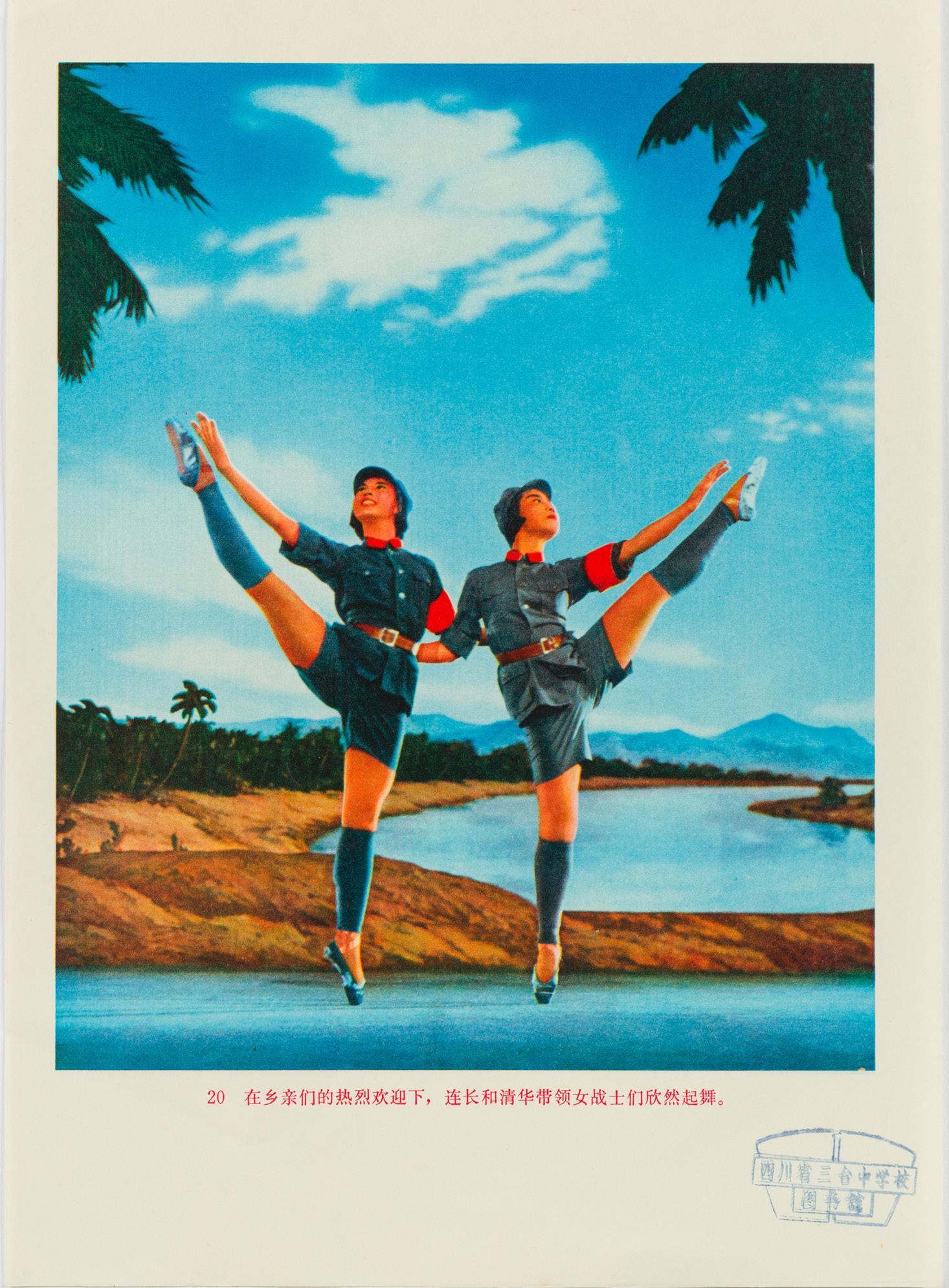

Based on a folktale, the ballet The White-Haired Girl (白毛女), tells a story of Yang Xi’er, a young peasant girl who is forced into slavery by the evil landlord Huang Shiren. Xi’er flees the village, her hair turning white as a result of her ordeal, but her tenacity helps her seek revenge against the landowner and free other peasants from his exploitation. Similar to The Red Detachment of Women, The White-Haired Girl highlights the poor conditions of the peasantry in pre-Liberation China and the tyranny of the upper-classes. This lampstand illustrates the popularity and ubiquity of the model performances, as their imagery was adapted for objects for daily use.

Female Soldier from the Red Detachment of Women 红色娘子军女兵

1966-1976

Porcelain Private Collection

This ceramic sculpture depicts a soldier from the all-female specialized division of the Red Army featured in the model ballet The Red Detachment of Women (红色娘子军). Rifle in hand and clad in military uniform, she is portrayed as a strong and powerful woman. The ballet tells the story of the peasant girl Wu Qinghua, who escapes the tyranny of a local landlord and joins the Women’s Detachment of the Communist Army. Over the course of the ballet, Qinghua helps lead a successful revolt against the landlord and eventually becomes the commissar of the detachment. The Red Detachment of Women was one of the most popular model performances and sent a message of women’s liberation

45

45

46 Film stills from The Red Detachment of Women 红色娘子军 1970 Poster Collection Wende Museum 46

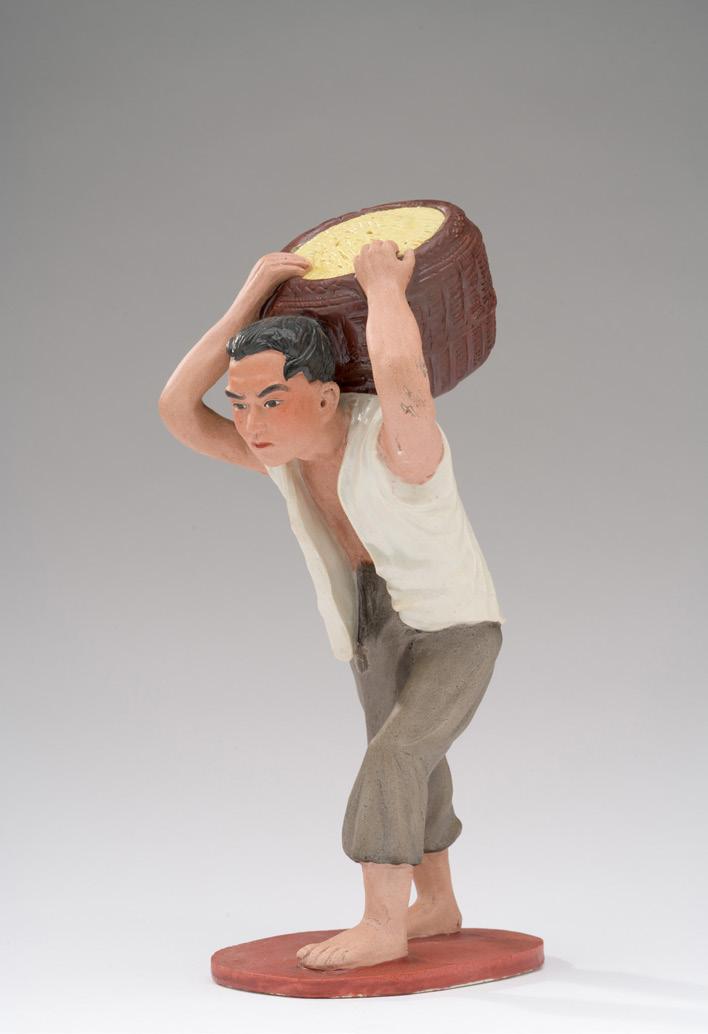

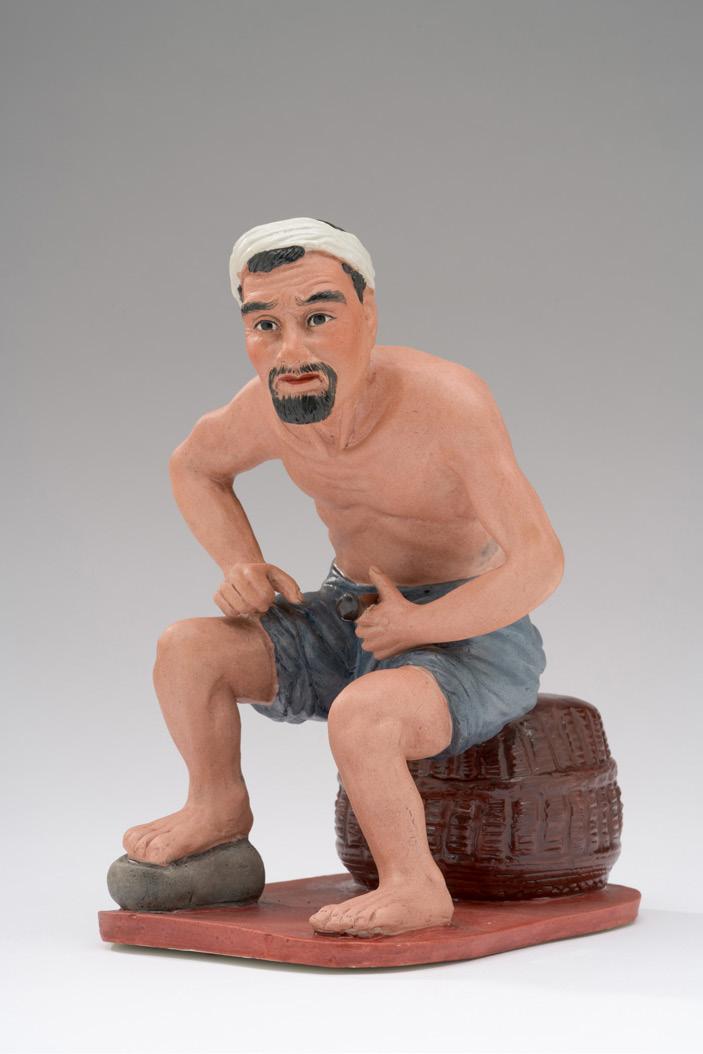

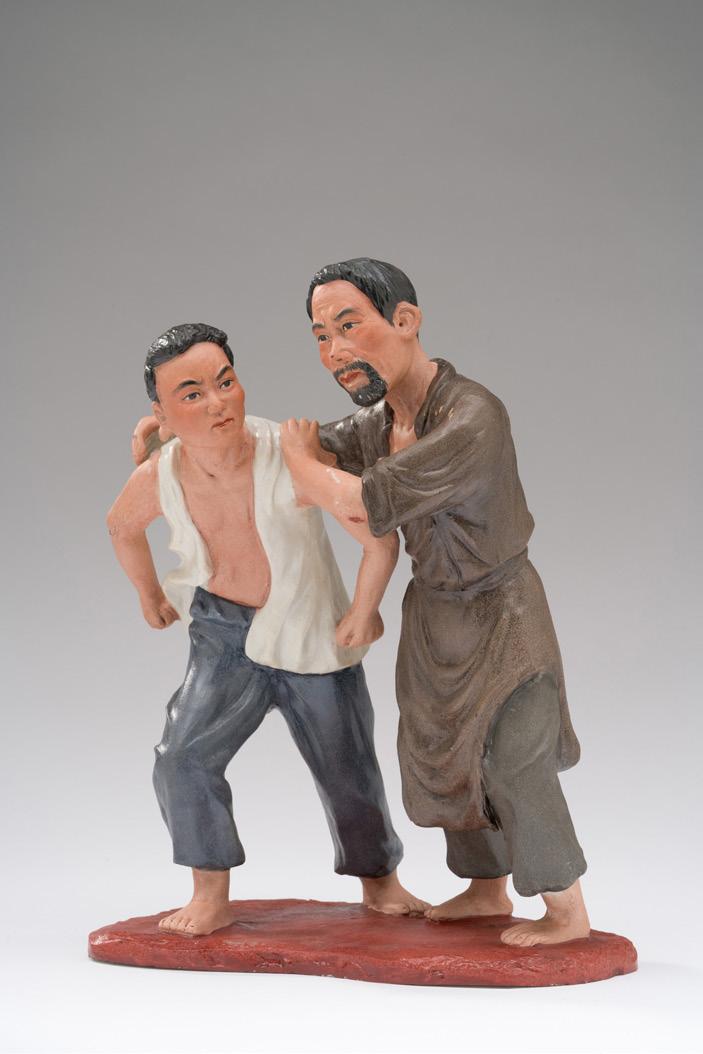

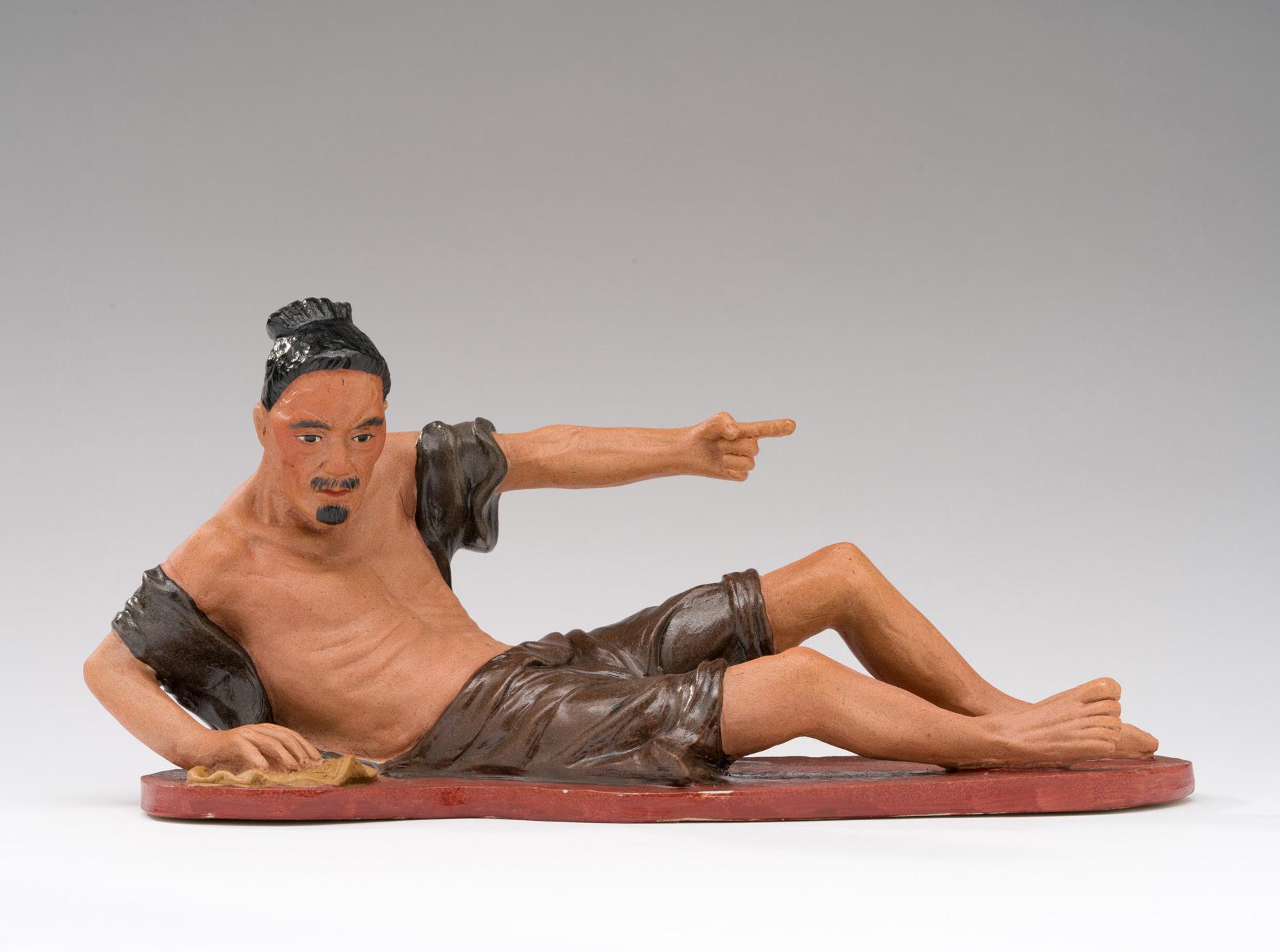

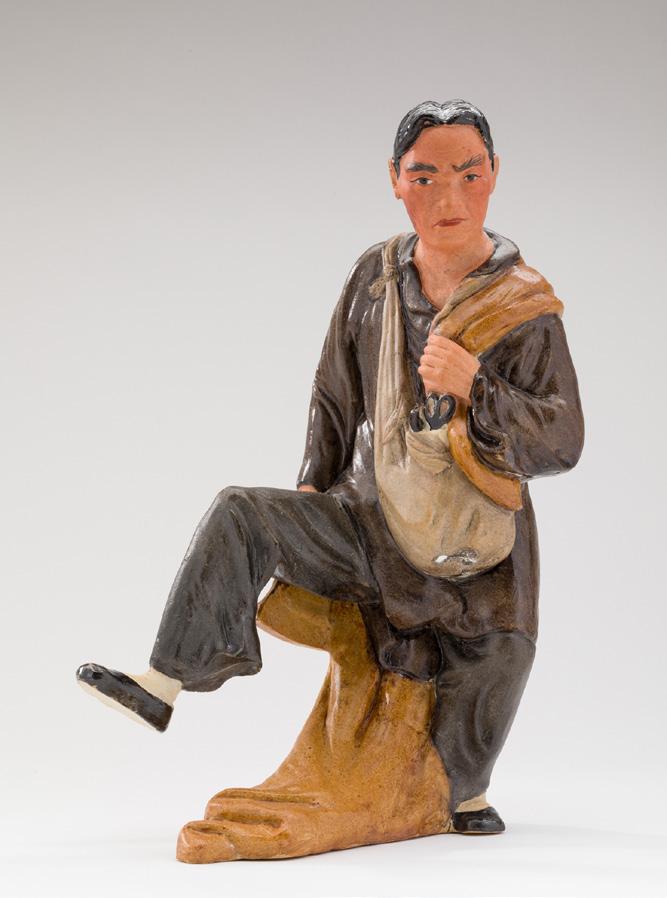

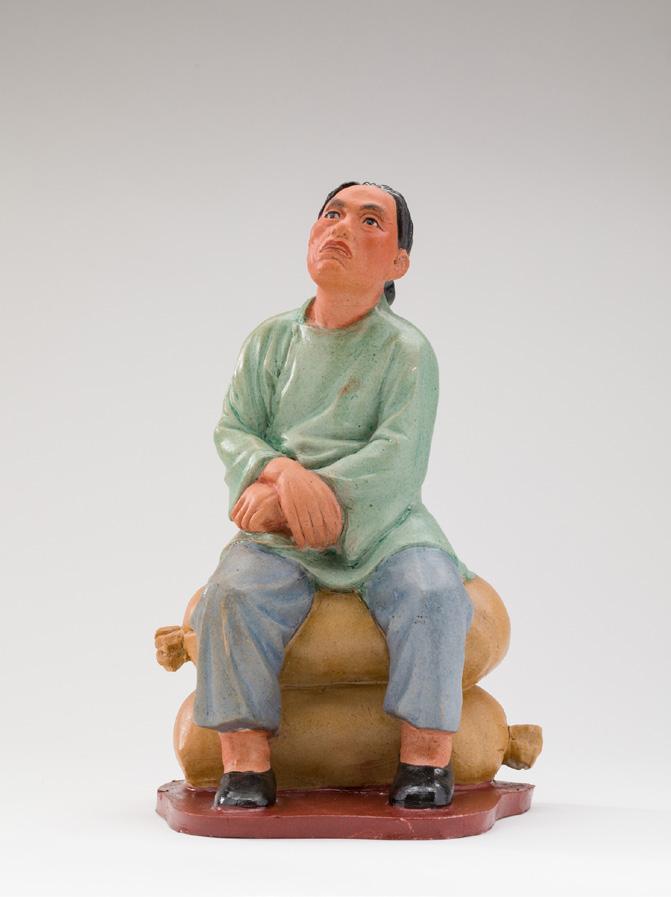

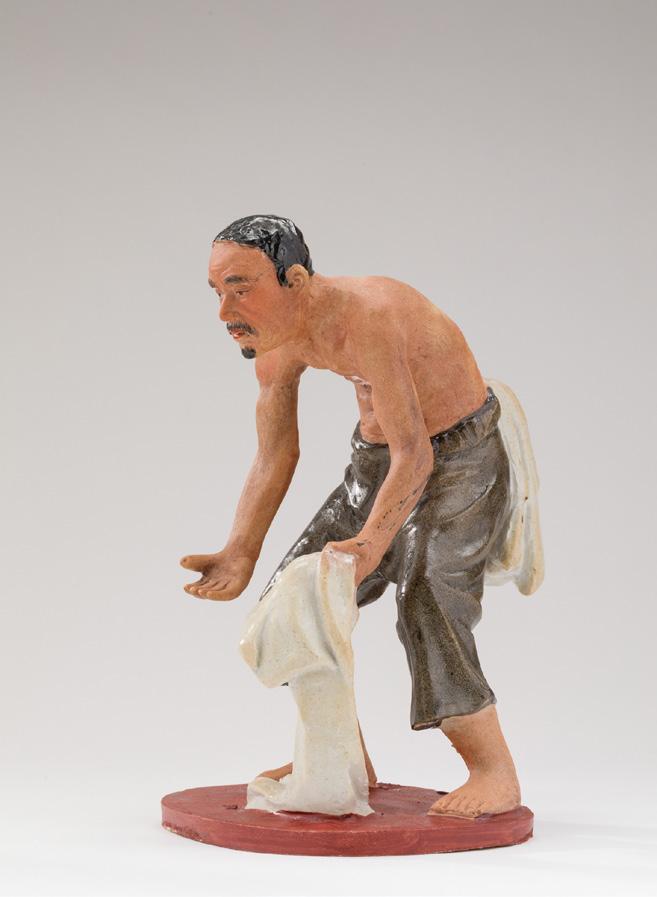

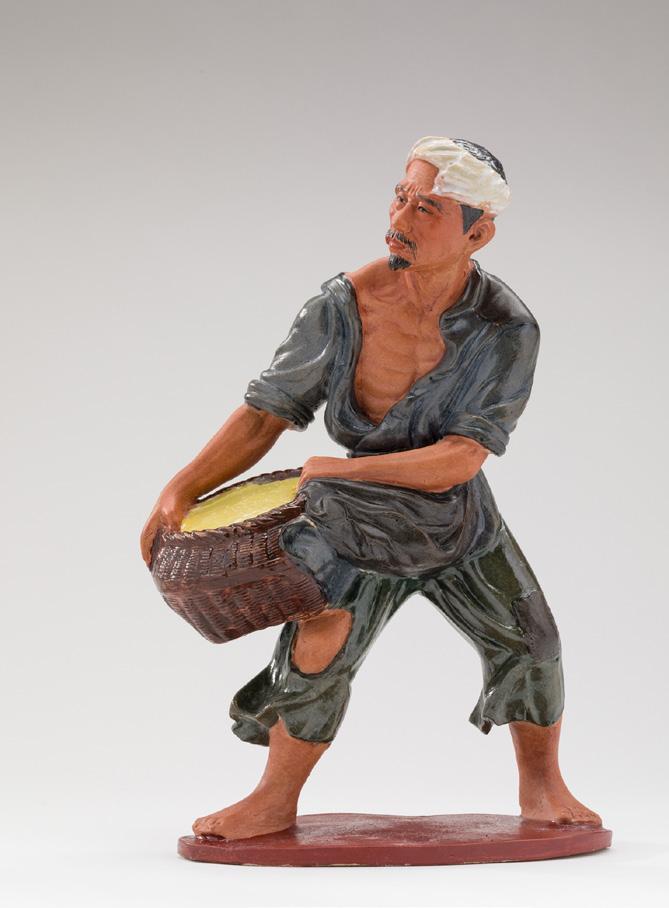

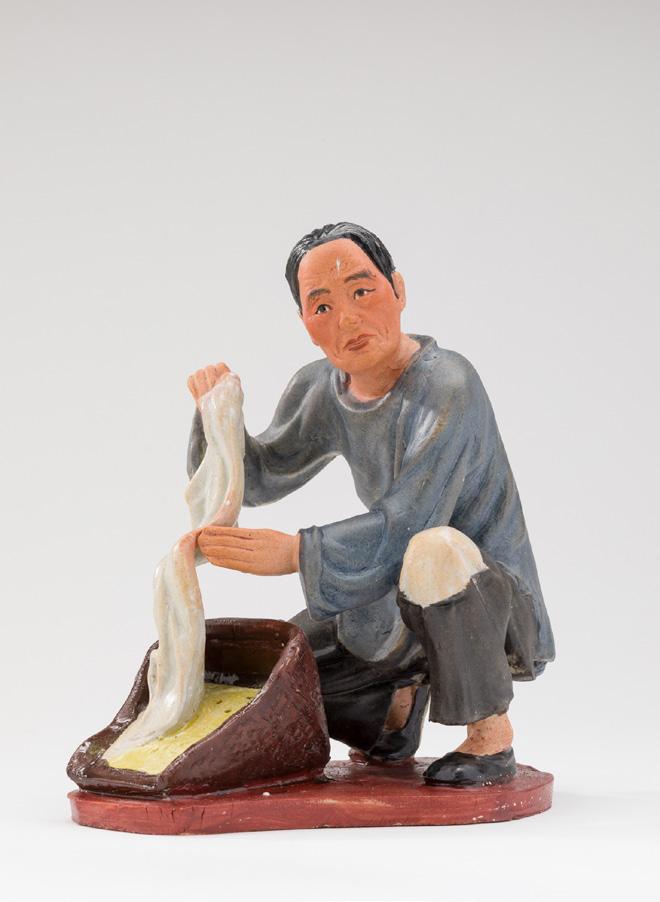

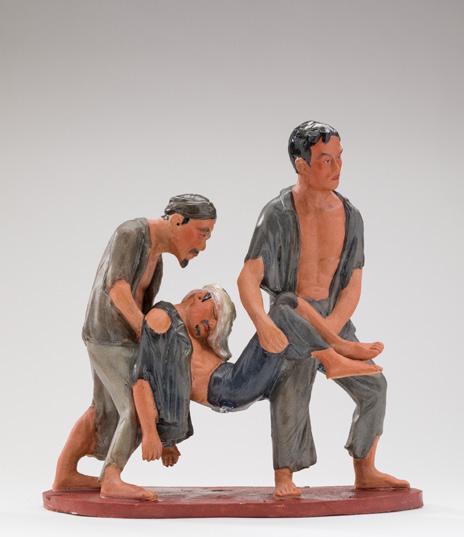

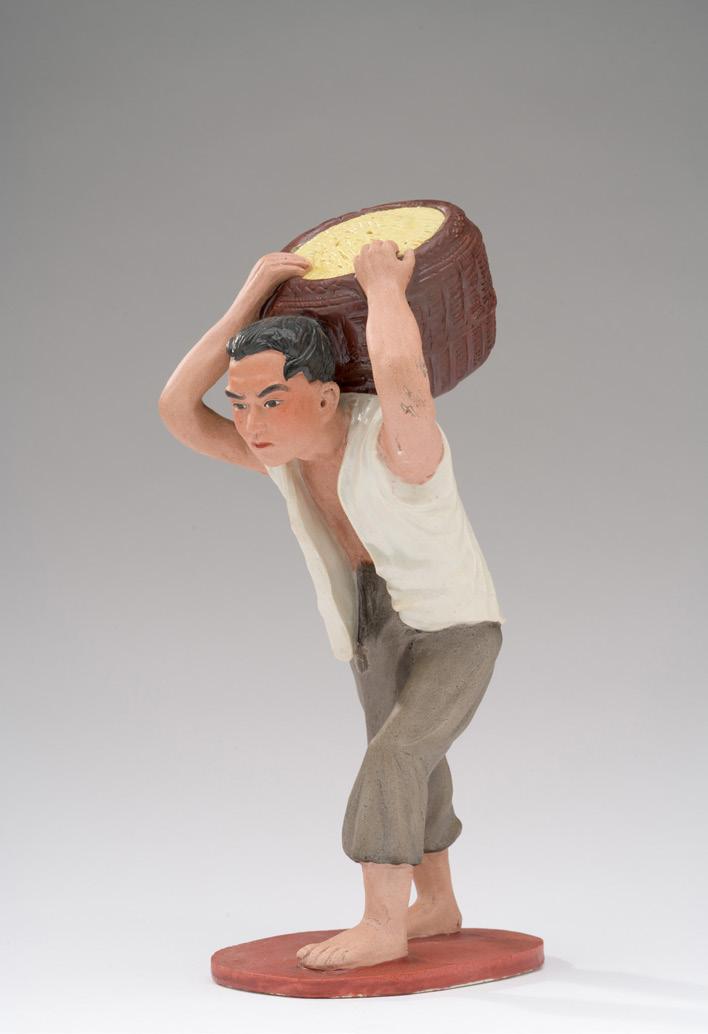

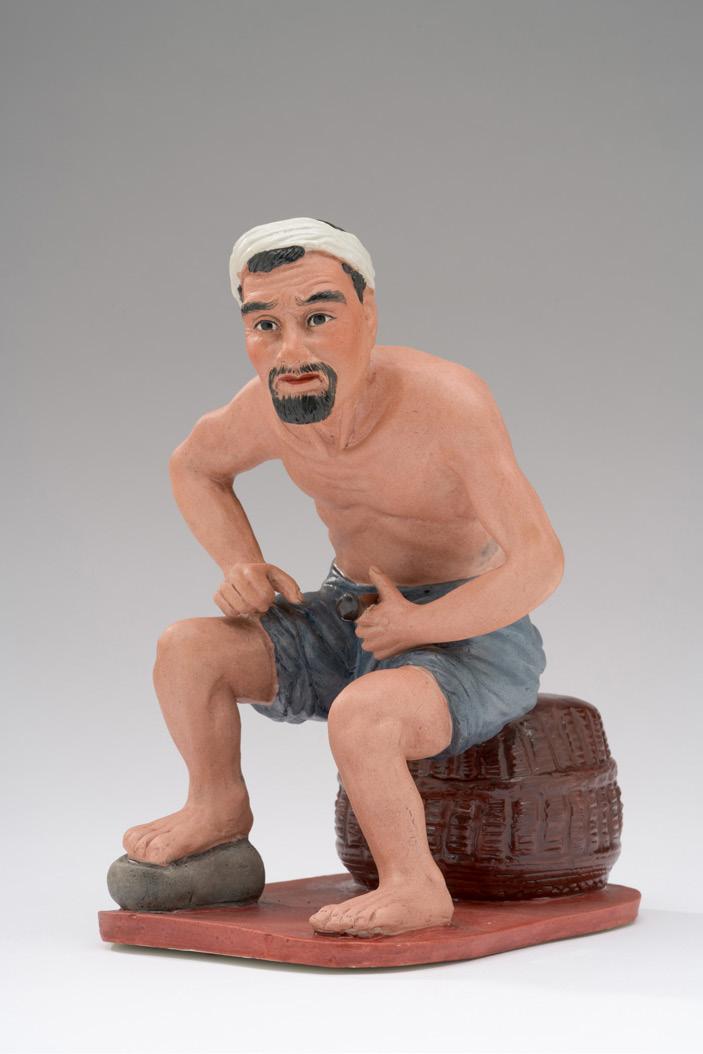

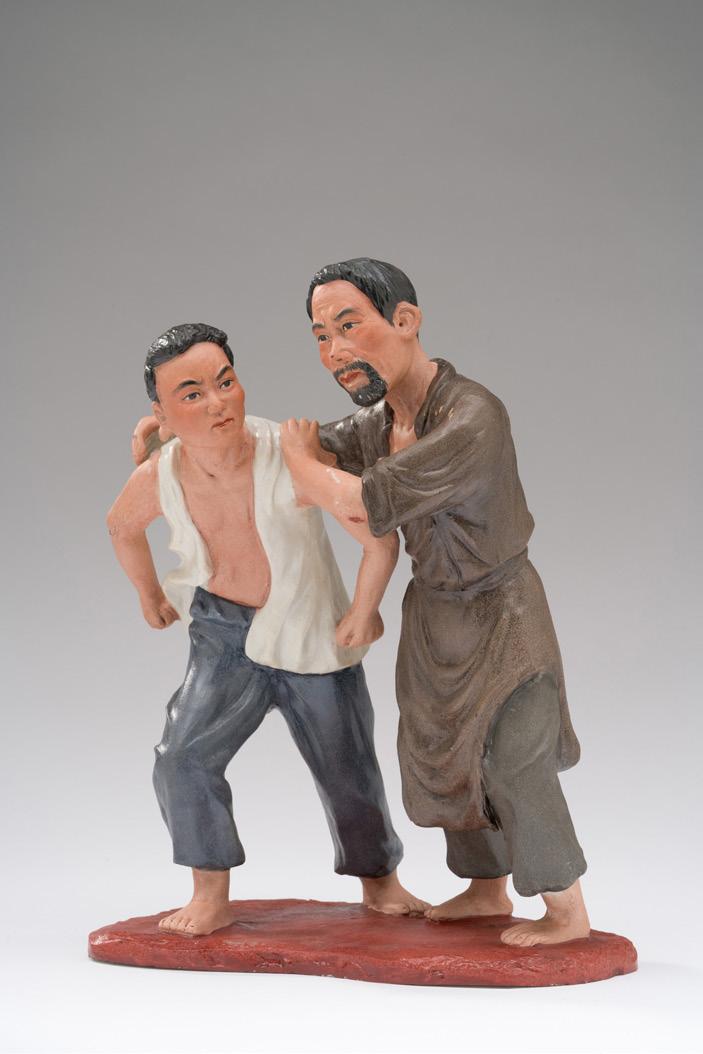

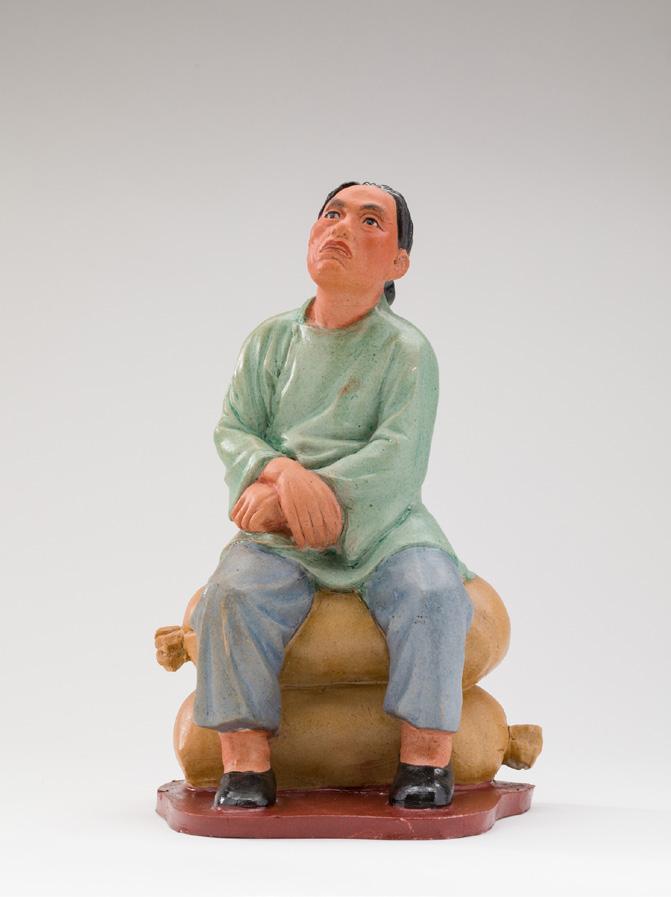

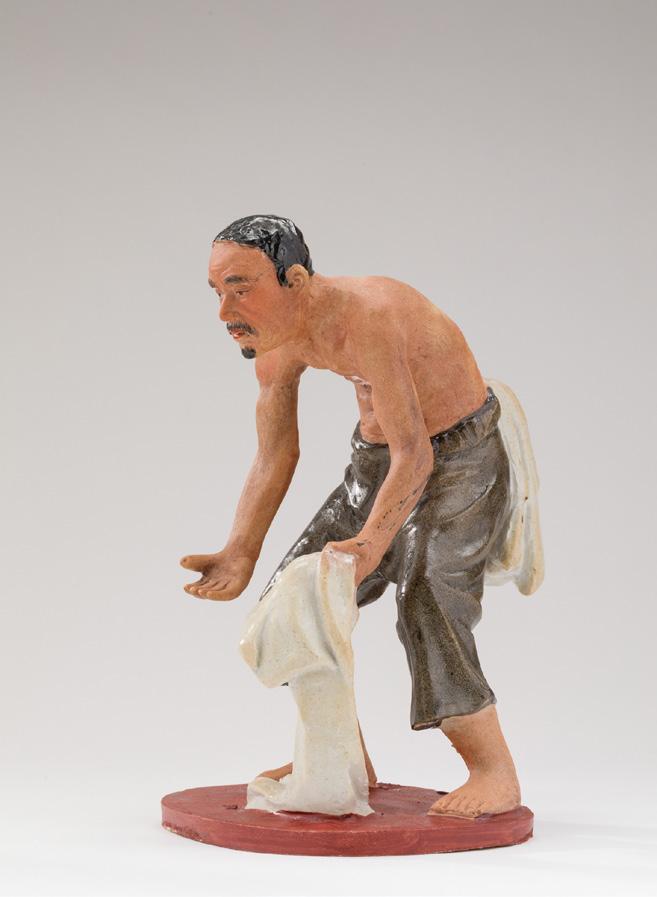

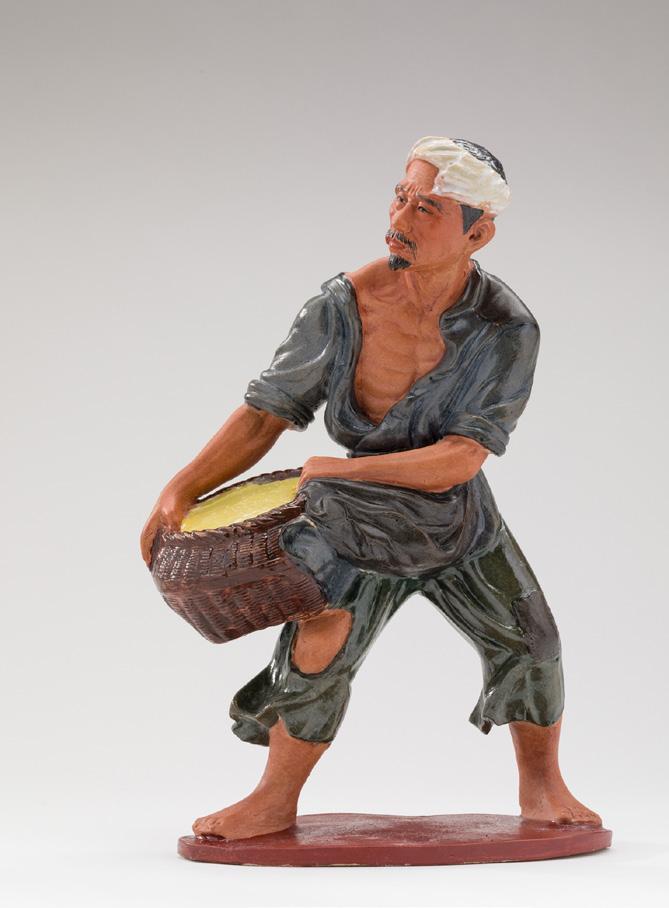

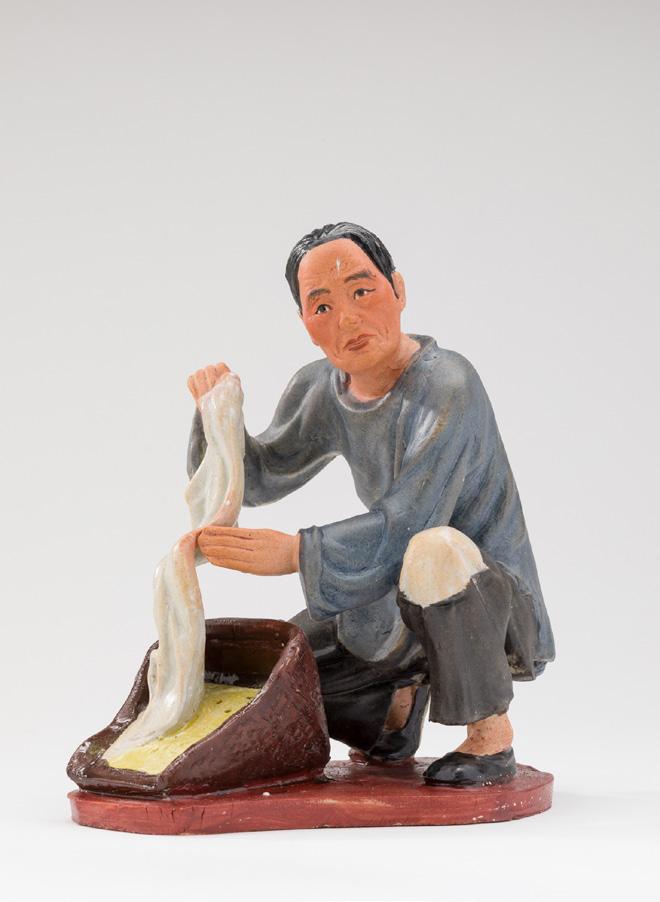

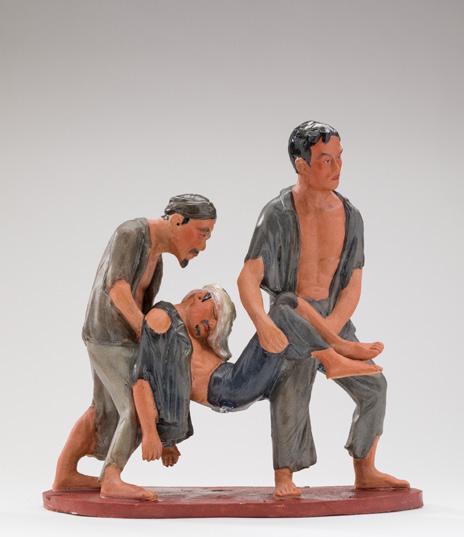

In 1965, a team of sculptors from the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts created a massive installation of 114 life-size terracotta figures that were installed in the former courtyard home of the landlord, Liu Wencai. This massive display—depicting the suffering of poor tenant farmers paying their annual rent in grain to a greedy landlord—was intended to illustrate the harsh conditions of the peasantry and tyranny of the upper classes before the liberation of the nation by the Chinese Communist Party in 1949. After several revisions, which were made in order to emphasize its educational content and class struggle, Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, declared the installation a model work of art. Life-size copies of the Rent Collection Courtyard were quickly erected in provinces across the nation. At Jingdezhen, sculptors created small-scale versions in porcelain that could be arranged into different tableaux, as demonstrated by the two examples in this vitrine.

47 RENT COLLECTION COURTYARD SERIES I AND II

Rent Collection Courtyard I 收租院 1966-1976 Porcelain Private Collection 47

48 48

49 Rent Collection Courtyard II 收租院 1966-1976 Porcelain Private Collection 49

50 50

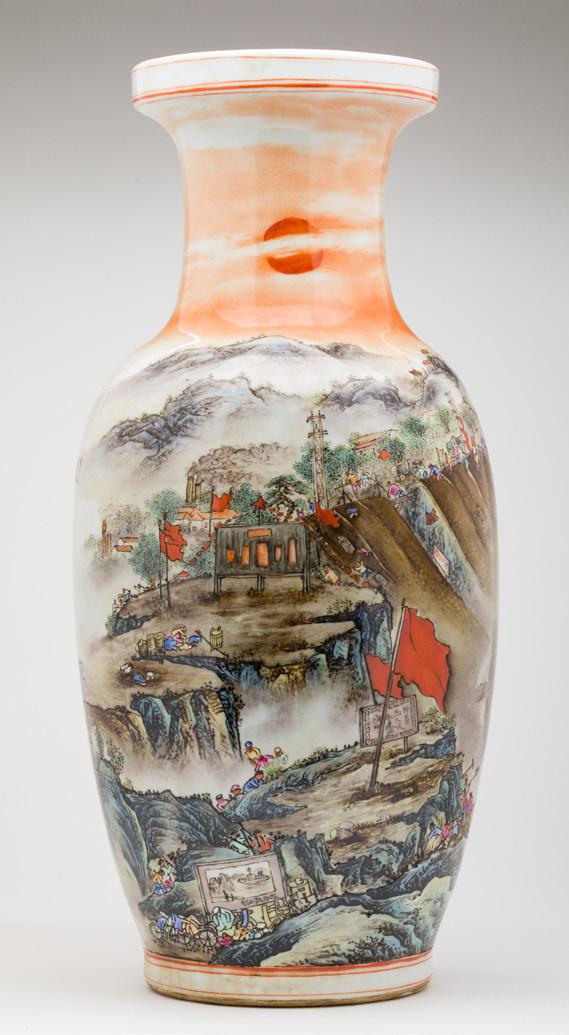

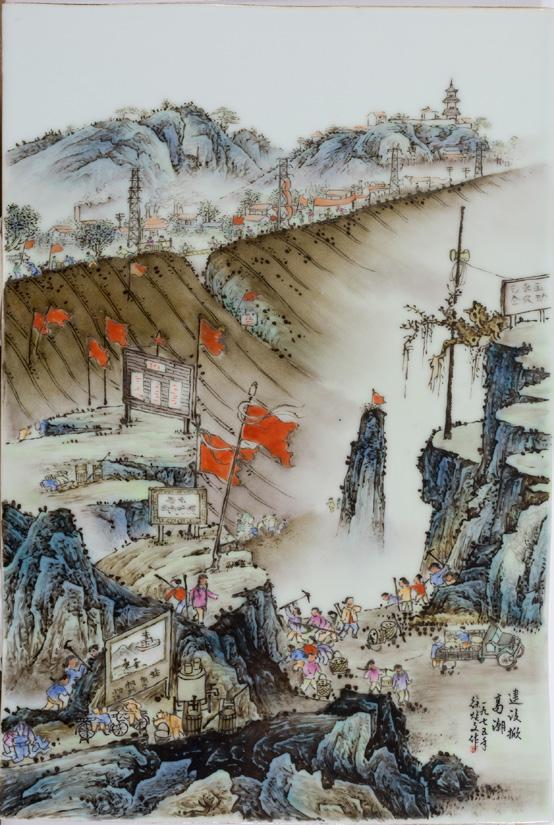

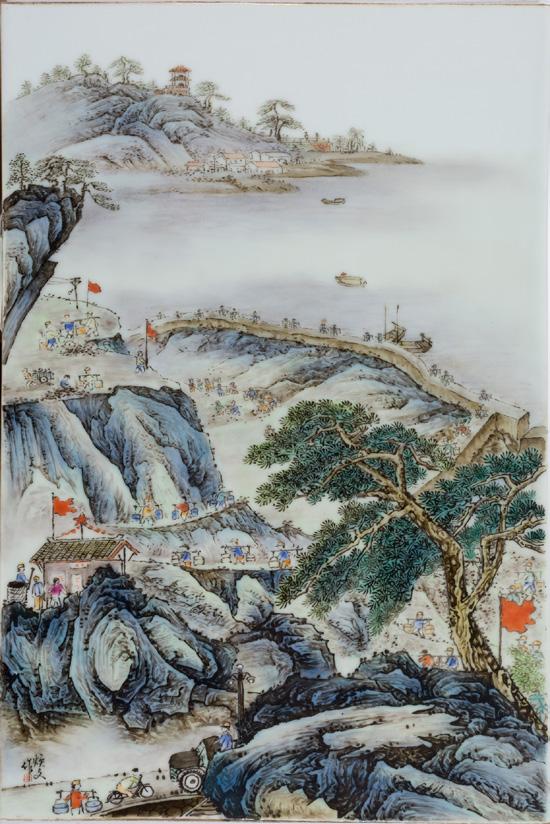

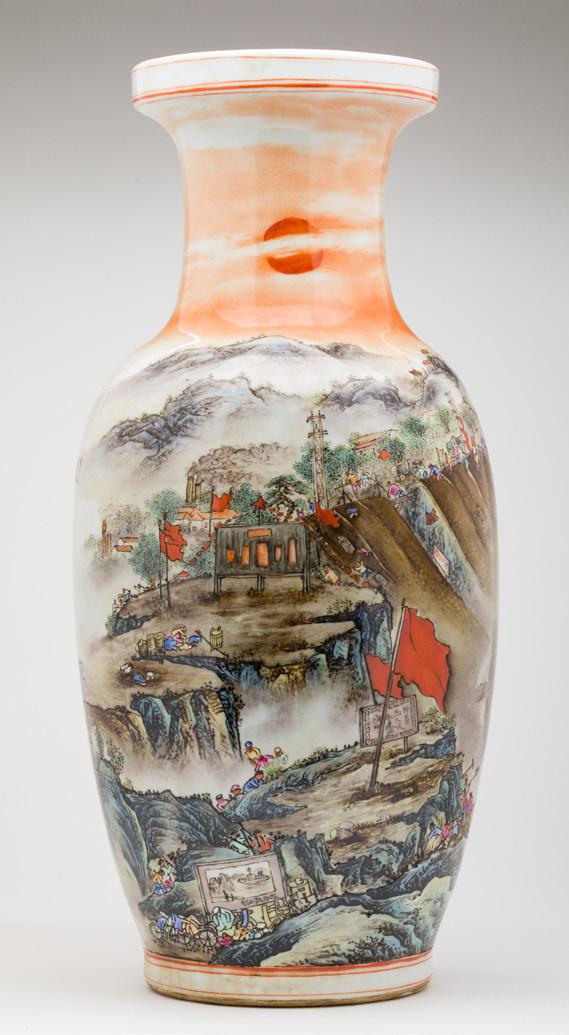

THE REVOLUTIONARY LANDSCAPE

If the purpose of Mao’s movement was to remake the cultural realm according to his new, Socialist vision, what happened to traditional art forms? Chinese culture has long been associated with guohua (国画), traditional ink painting. However, during the Cultural Revolution, this art form had a fraught status. The subject matter of guohua, which primarily depicted scenic landscapes, was apolitical and consequently deemed unacceptable. Additionally, the origins of the art were feudal: in dynastic China, such works were made by the literati or scholar officials—members of the upper-class.

Painters thus turned to new subject matter, such as industrial scenes, cityscapes, and figural compositions featuring peasants, workers, soldiers, and revolutionary leaders. Ceramicists at Jingdezhen had started imitating guohua in the twentieth century, using glazes to paint landscapes decorating vessels and plaques. But during the Cultural Revolution, artists were forced to adapt; they created landscapes depicting traditional scenery, but ones that included agricultural machinery, power lines, coal mines, and factories—signifiers of the nation’s industrial growth and prosperity—to give their compositions a politically correct message. While many ceramic artists had been incarcerated during the early years of the Cultural Revolution, most were rehabilitated after 1969, as it became apparent that their artistic skills were irreplaceable. Moreover, Jingdezhen’s remote location and distance from the capital allowed ceramicists somewhat greater artistic freedoms.

The objects in this section not only highlight the high level of skill required to create guohua, but also attest to the resilience of these painters, who adapted to rigid restrictions and navigated a changing political climate to ensure the survival of the traditional arts.

Zou Guojun 邹国钧

Beat the Gongs and Drums to Deliver Good News 敲锣打鼓送喜报,传送毛主席最高指示

1972 Porcelain Private Collection

The painting on the vase depicts a traditional landscape of misty, green-blue mountains, lush foliage, and a peaceful lake that would not be out of place in a Ming-dynasty (1368-1644) ink painting. However, to add political content, the artist has dotted the landscape with small red flags and included a scene of local peasants entering the village schoolhouse, presumably to study the Chairman’s teachings together. The slogan on the wall reads, “Promote the traditions of the revolution.” The inscription on the vase further gives the otherwise apolitical scene a revolutionary bent; it reads “Beat the gongs and drums to deliver the good news and Chairman Mao’s highest instructions.”

51

51

Xu Huanwen

徐焕文

Beautiful Spring in Jiangnan 江南春秀 1973

Porcelain Private Collection

Xu Huanwen (b. 1932) was a well-known porcelain painter based in Jingdezhen who served as the director of the Jingdezhen Art Porcelain Factory. His vase depicts a peaceful spring scene at a village commune located on the banks of the Yangzi river in the Jiangnan region. In the foreground, one sees the commune’s buildings, topped with red flags. A group of children play in a field underneath a massive weeping willow. In the distance are green mountains with reservoirs and terraced rice paddies. The inclusion of trucks, tractors, and power lines within the composition highlight the modernization of the countryside under the Chinese Communist Party.

Chen Yaoxing 陈耀星 Building Beautiful Rivers and Mountains 建设秀美河山 1968

Porcelain Private Collection

Chen Yaoxing was a porcelain artist who also trained in traditional Chinese ink painting. His familiarity with works from the Song (960-1279), Yuan (1271-1368), Ming (1368-1644), and Qing (16361911) dynasties is evident in this vase, with its beautiful lake, peaceful village, and mountain range—only the military guard towers suggest that this scene takes place in post-Liberation China, rather than in the past. Chen uses varying shades of green to create nuance in the foliage and carefully applies glaze to suggest the atmospheric mist floating above the lake and mountain peaks in the distance. The white and green landscape, which wraps around the vessel horizontally and reads like a handscroll, contrasts with the bright blue of the vase.

52

52

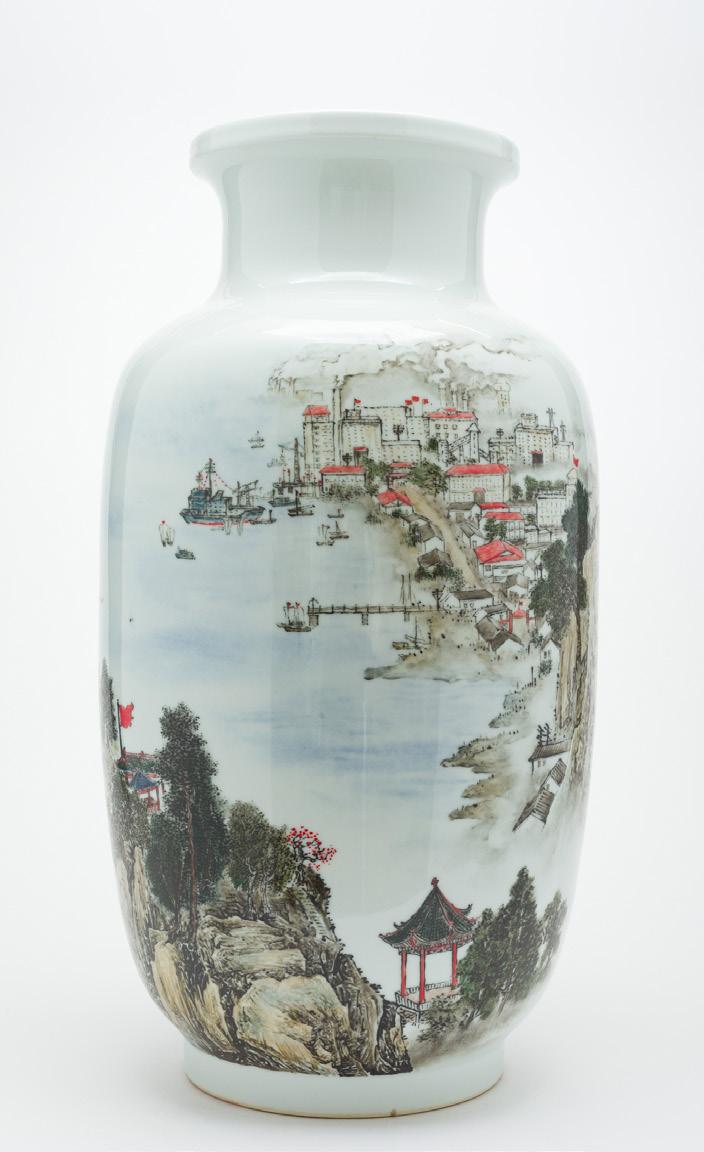

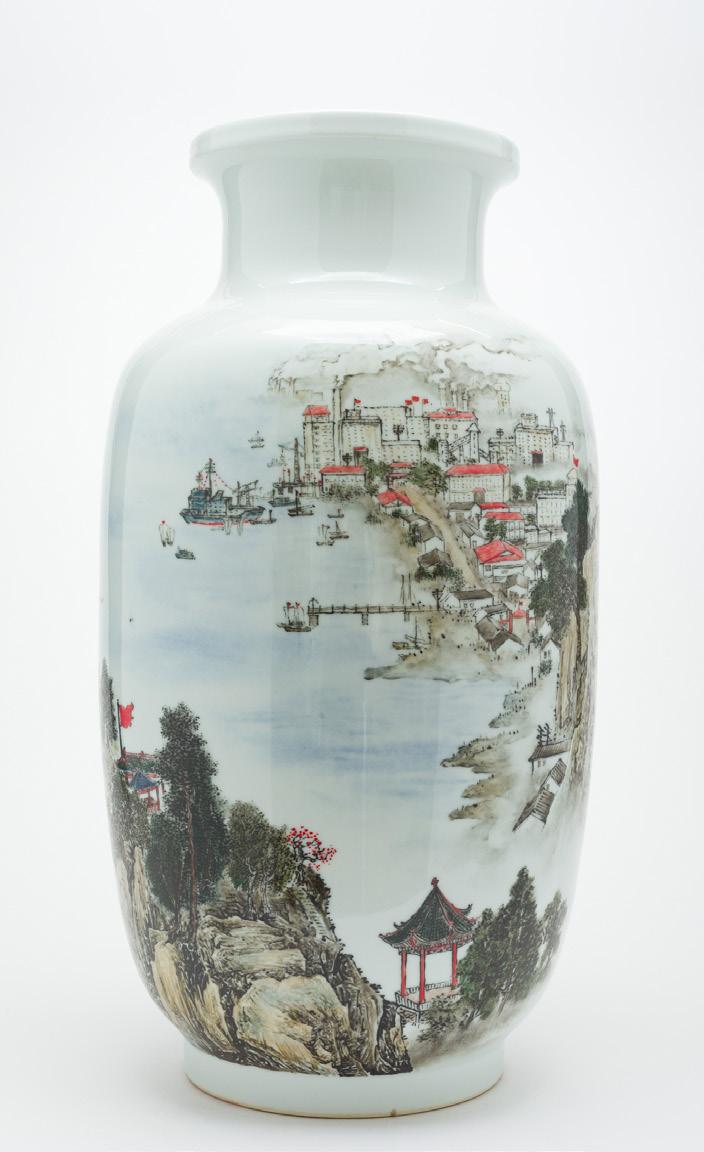

Xu Huanwen

徐焕文

Thousands of Boats Sailing on the Yangzi River

扬子江上帆千行

1976

Porcelain Private Collection

This vase features a busy riverscape on the Yangzi, China’s longest river. The artist has combined the beauty of the local scenery—imposing, rocky cliffs, white-sailed boats, and blue waters—with a scene of a riverside city and its port. The prominent mountains, combined with the river, illustrate the two main elements of traditional Chinese landscape, or shanshui (山水, which literally means “mountains and water”). However, the modern, multi-story buildings and factories on the shore, which contrast with the scenic traditional-style pavilions perched in the mountains, render the scene politically correct. These, along with the many boats floating on the water, allude to thriving trade and economic prosperity in the countryside.

Xu Huanwen

Xu Huanwen

徐焕文

Great Leap Forward in Agriculture

农业大跃进

It Is Glorious to Work Hard 劳动光荣

1974

Porcelain Private Collection

This pair of brightly colored vases features an interesting mix of old and new traditions in these idealized scenes of industrious labor in the countryside. One vase depicts peasants working on a hillside field while the other shows laborers busily loading trucks. Both scenes are set within a landscape featuring romantic, craggy bluffs and cliffs, gnarled trees, and misty mountains. In the distance are examples of traditional architecture, including pagodas and pavilions, which are paired with red flags, electrical towers, and power lines— signs of modernization in the countryside. The glowing red sun seen in both vases is probably an allusion to the Chairman, who was often described as “the red sun” or “the sun in the hearts of the Chinese people.” Moreover, the use of red, while not only auspicious in traditional Chinese culture, was also the color of revolution and the Chinese Communist Party.

53

53

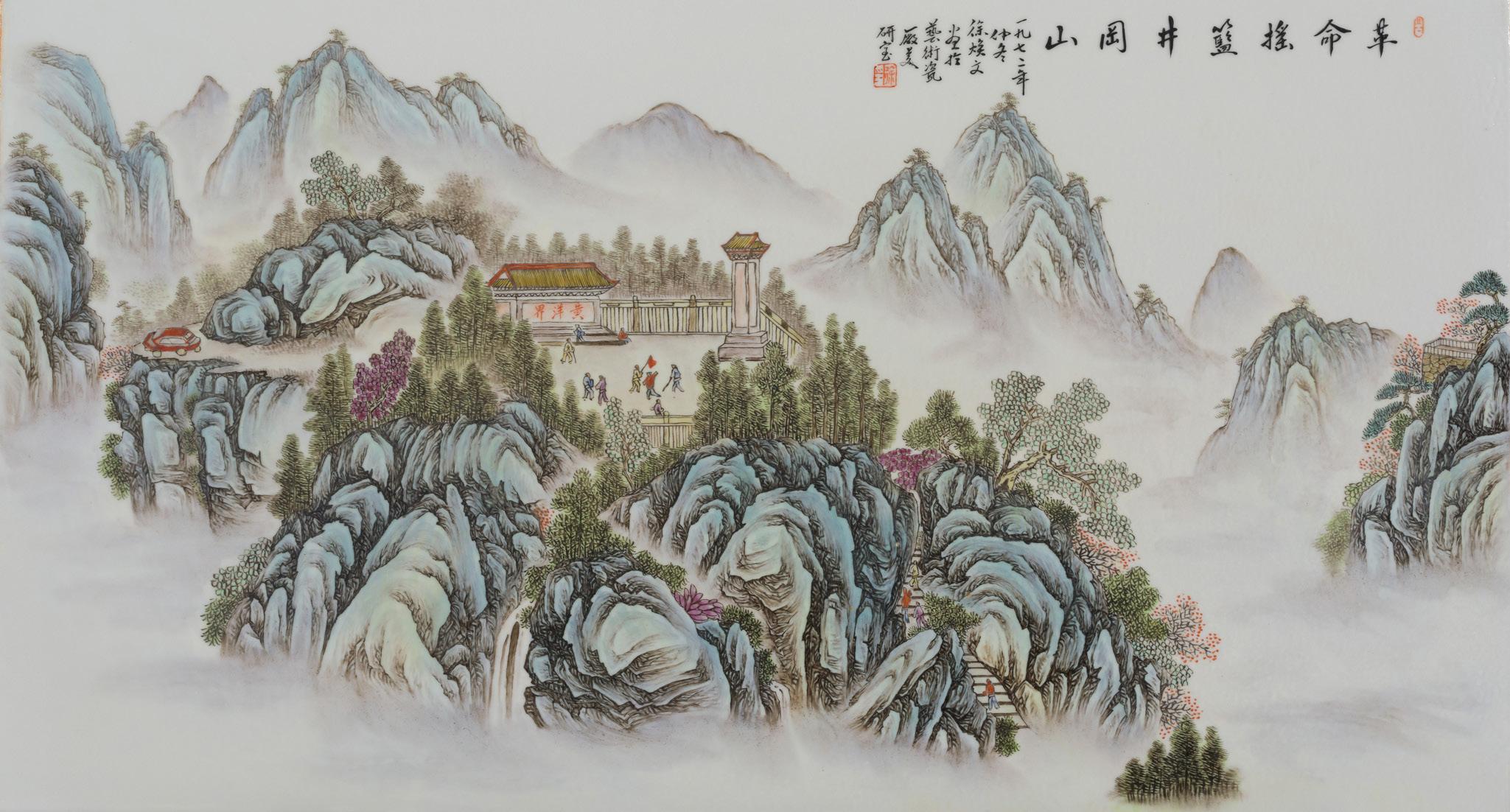

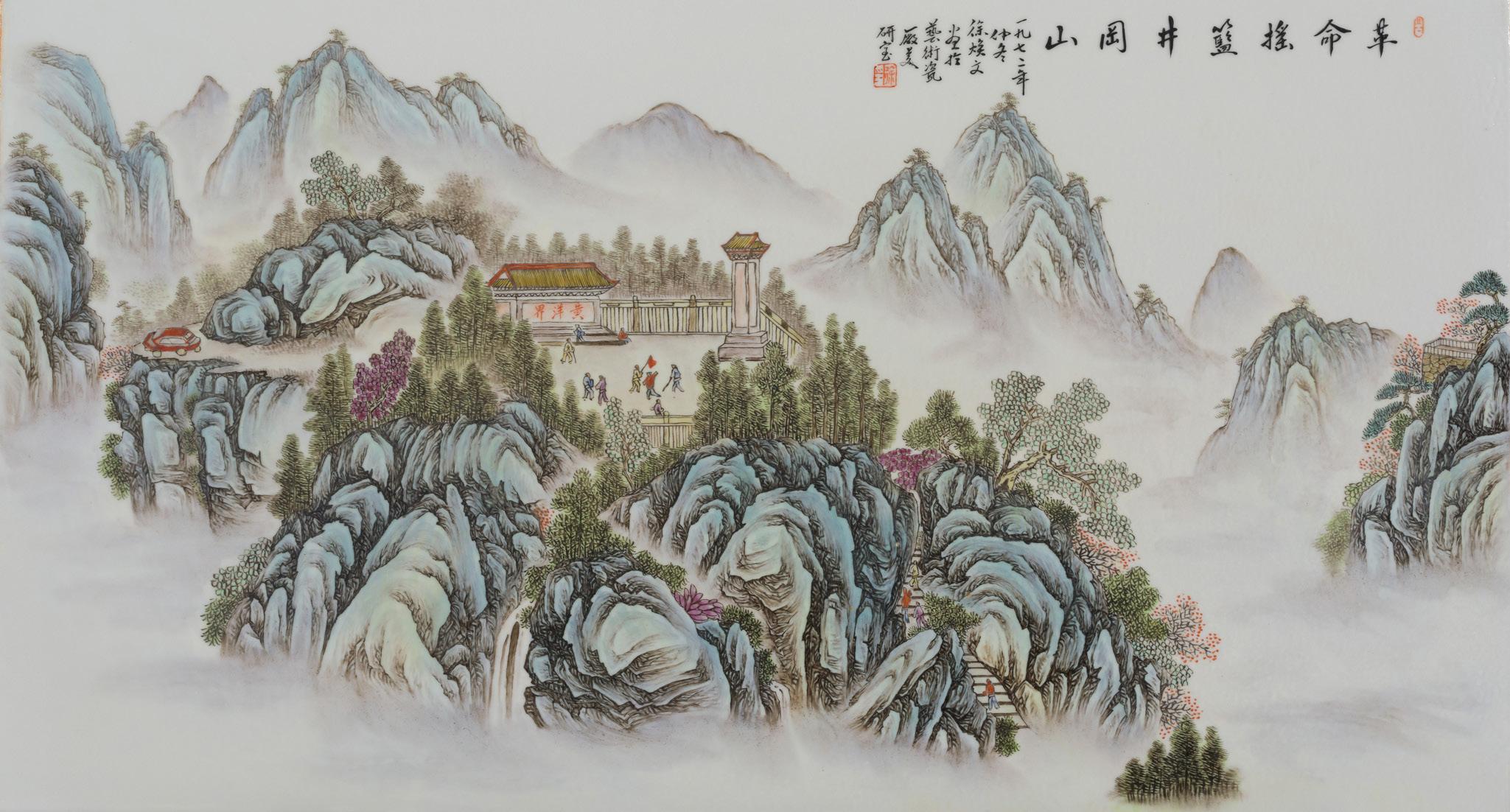

Xu Huanwen 徐焕文

Jinggangshan Is the Cradle of the Revolution 革命摇篮井冈山

1972

Porcelain Private Collection

Xu Huanwen 徐焕文

The Rising Sun Shines on the Green Mountain 旭日照翠岗

1966

Porcelain Private Collection

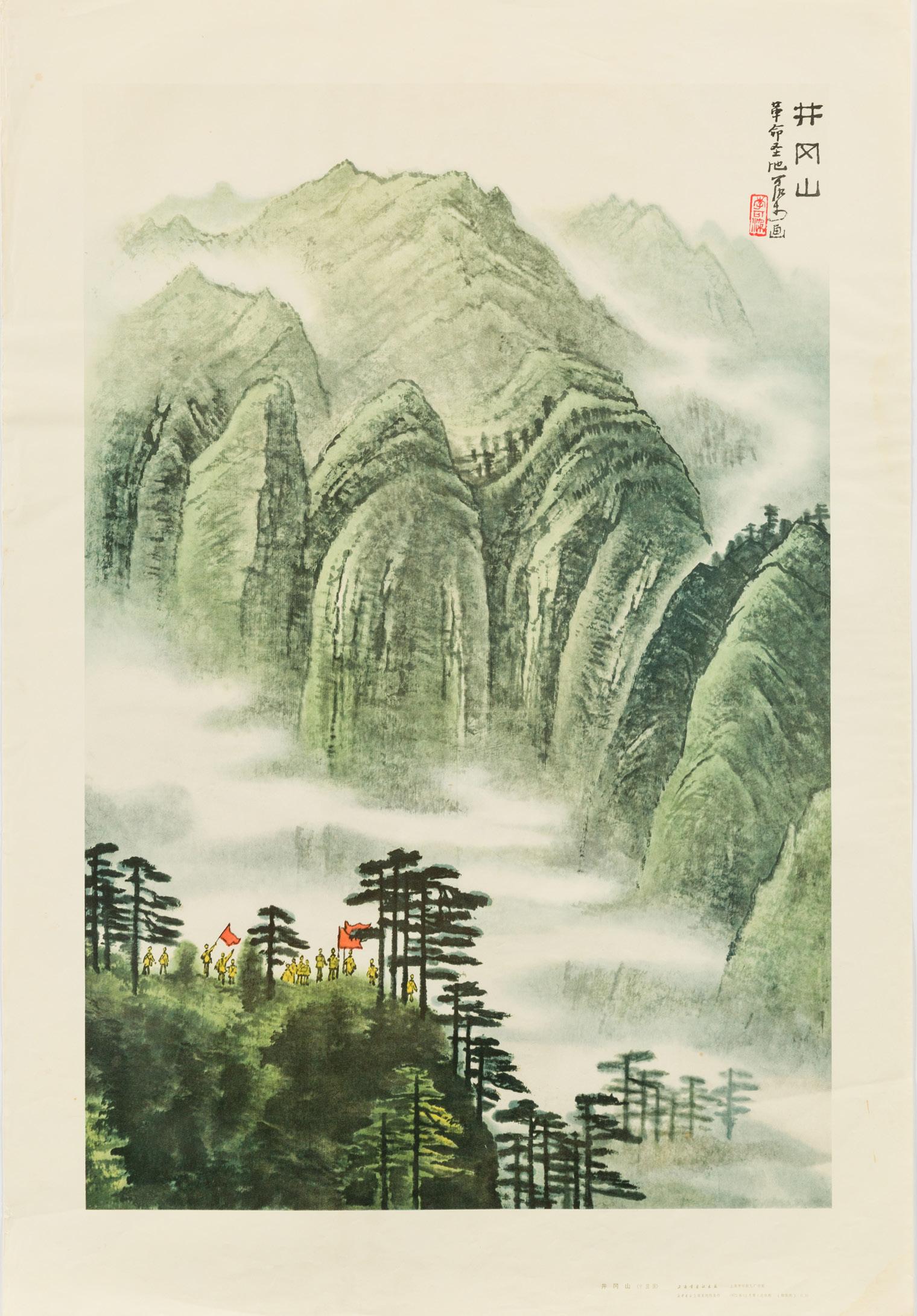

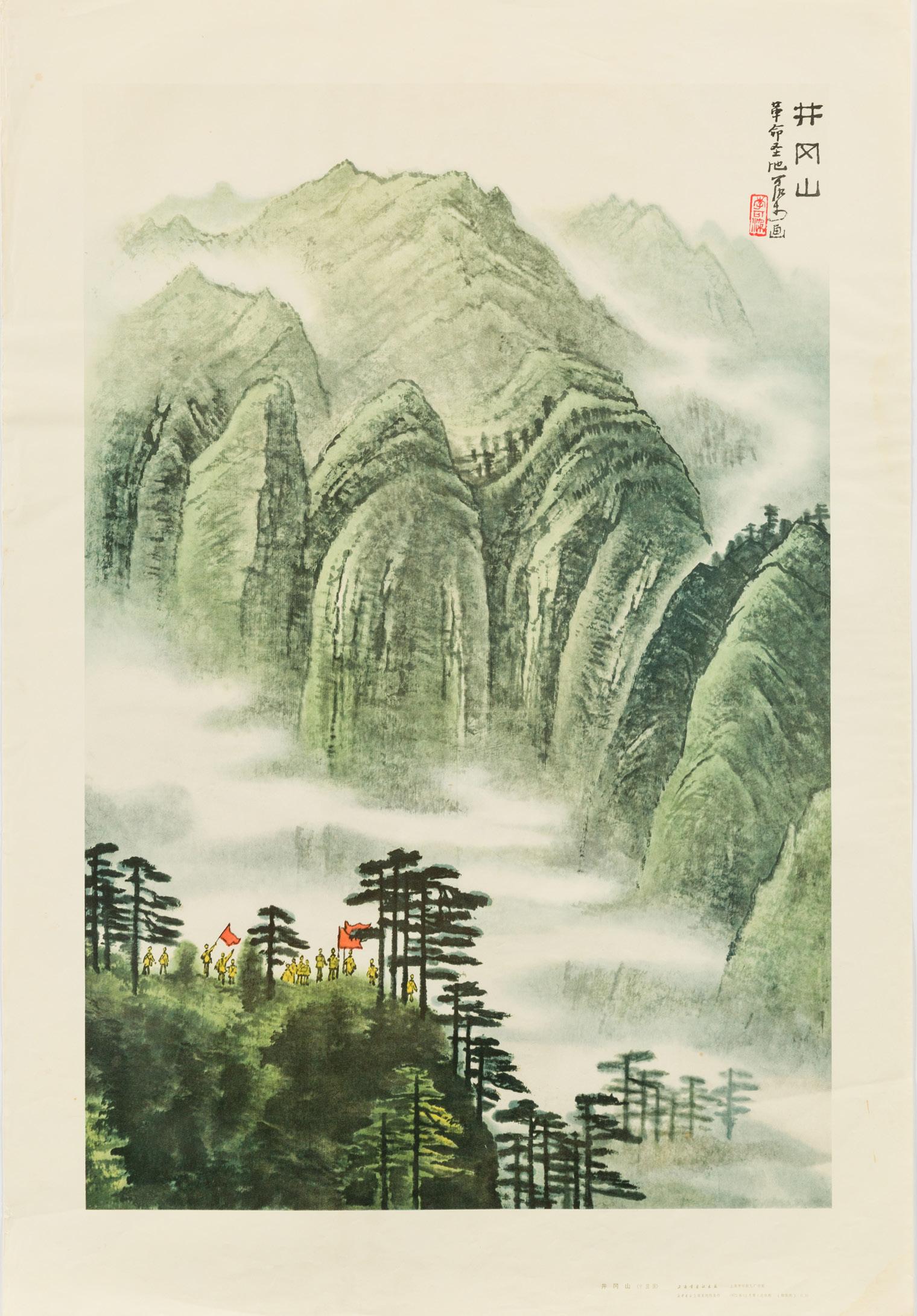

These two plaques depict traditional Chinese landscapes with craggy, misty mountains and lush greenery. At first glance, they seem to lack Socialist content such as the machinery, power lines, or agricultural work typical of Cultural Revolution landscapes. However, one plaque depicts Jinggangshan in Southeastern China, the site of the Communist Party’s first soviet, or elected governmental council. The location, which was deep in the mountains, is marked by a pavilion and tower. During the Cultural Revolution, Jinggangshan became an important place of pilgrimage for Red Guards. The second plaque makes an even more subtle allusion to revolutionary history. While the painting itself seems to purely depict a traditional landscape, the inscription, “The Red Sun Shines on the Green Mountain” gives the work its political content: Mao was often referred to as the “red sun,” or the “sun in the hearts of the Chinese people,” while the green mountain refers to the lush mountains of the Jinggang region.

54

54

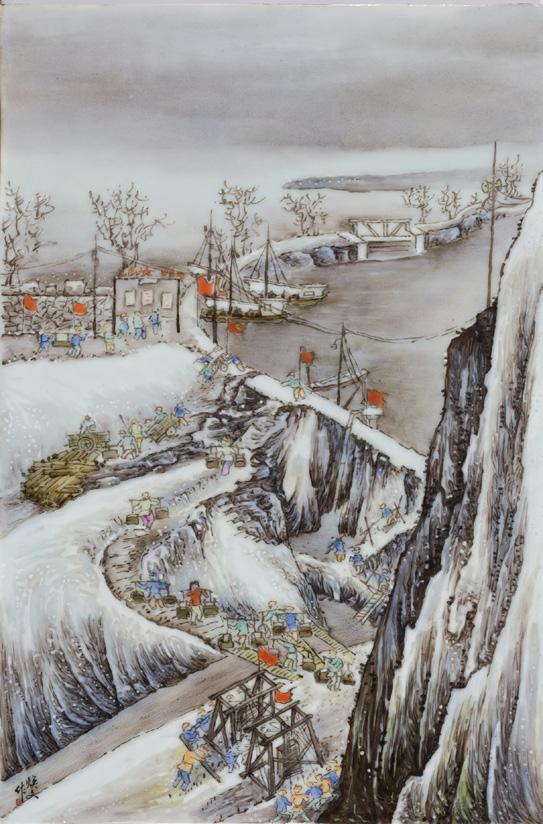

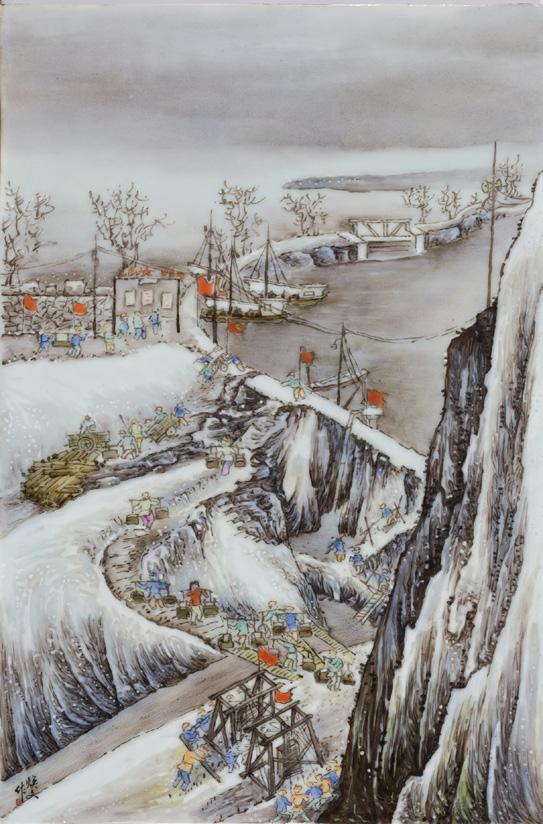

Xu Huanwen

徐焕文

Bring Construction to a New Climax 建设掀高潮

1975 Porcelain Private Collection

In this set of four plaques depicting scenes from the countryside in the different seasons, Xu Huanwen has rendered the texture of the craggy boulders and rocks, as well as the texture of the various tree branches and foliage, in a manner closely resembling traditional ink painting. The poetic representation of the landscape is paired with scenes of construction that serve to illustrate the nation’s industrial and agricultural progress in the countryside. Many small figures busily haul buckets, dig into the ground, or drive carts across the fields; the red flags dotting the landscape create an almost celebratory atmosphere.

Xu Huanwen

徐焕文

Fighting for Steel 为钢而战

1975 Porcelain Private Collection

The composition of this detailed and finely painted plaque combines traditional landscape elements with a scene of modern industry; it shows a large steel plant, with fiery chimneys and furnaces against a picturesque setting featuring a large lake and green mountains. Painted slogans and posters within the scene urge viewers to work hard and to build the nation’s resources, while the inscription on the top left of the plaque reads, “Anybody who works hard will succeed, look at the Four Modernizations through the work of making steel.” The Four Modernizations were areas of development designated by the Chinese Communist Party—agriculture, industry, science and technology, and defense—that the nation sought to modernize by the end of the twentieth century.

55

55

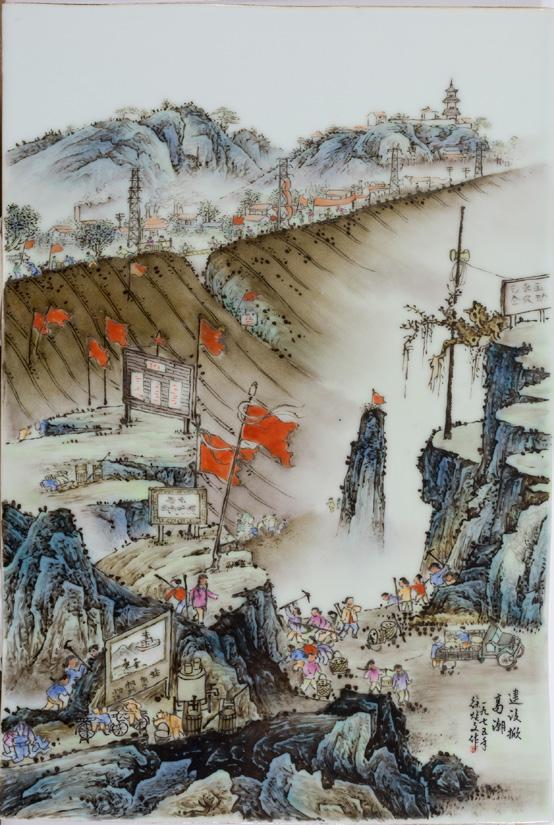

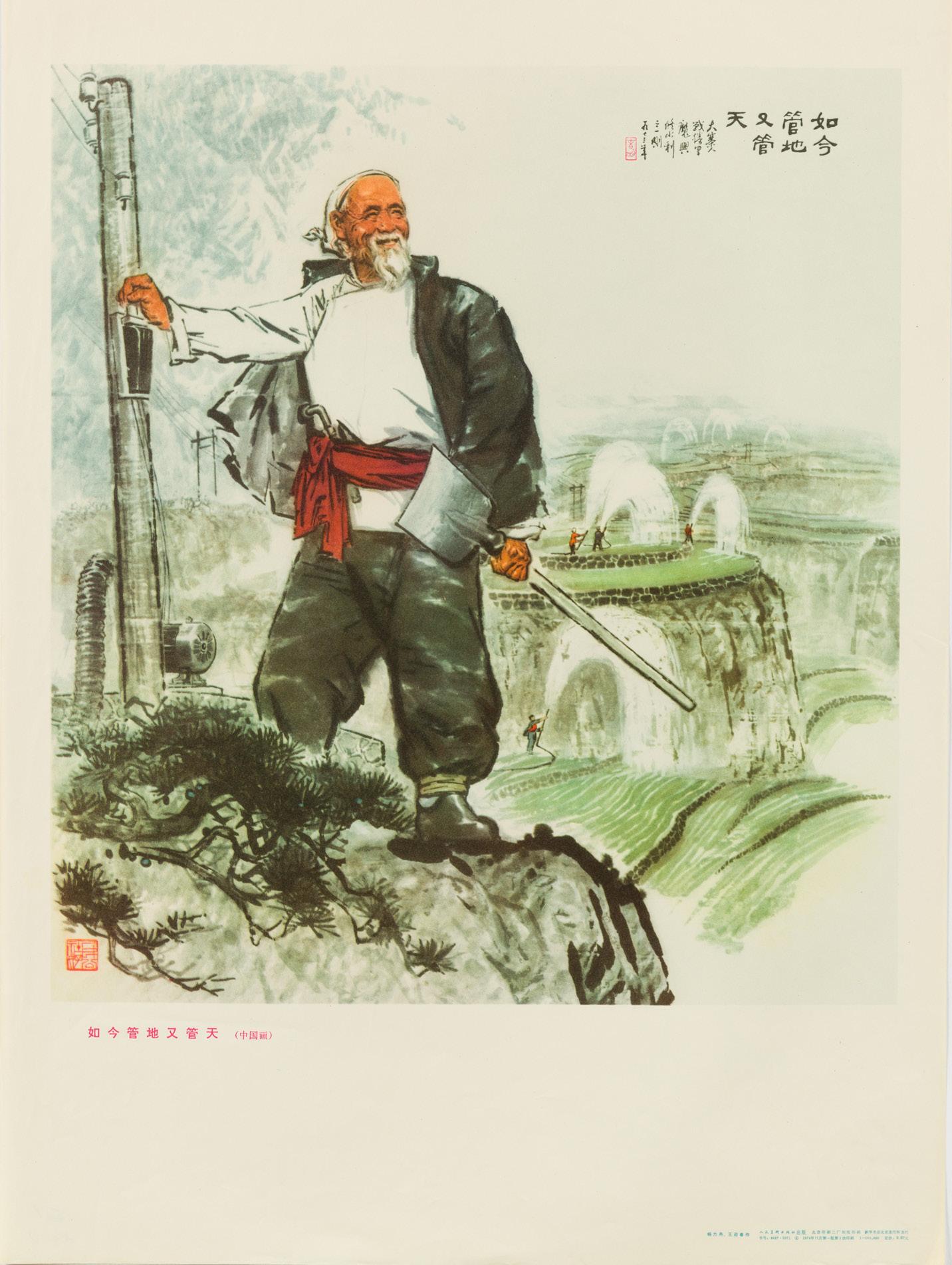

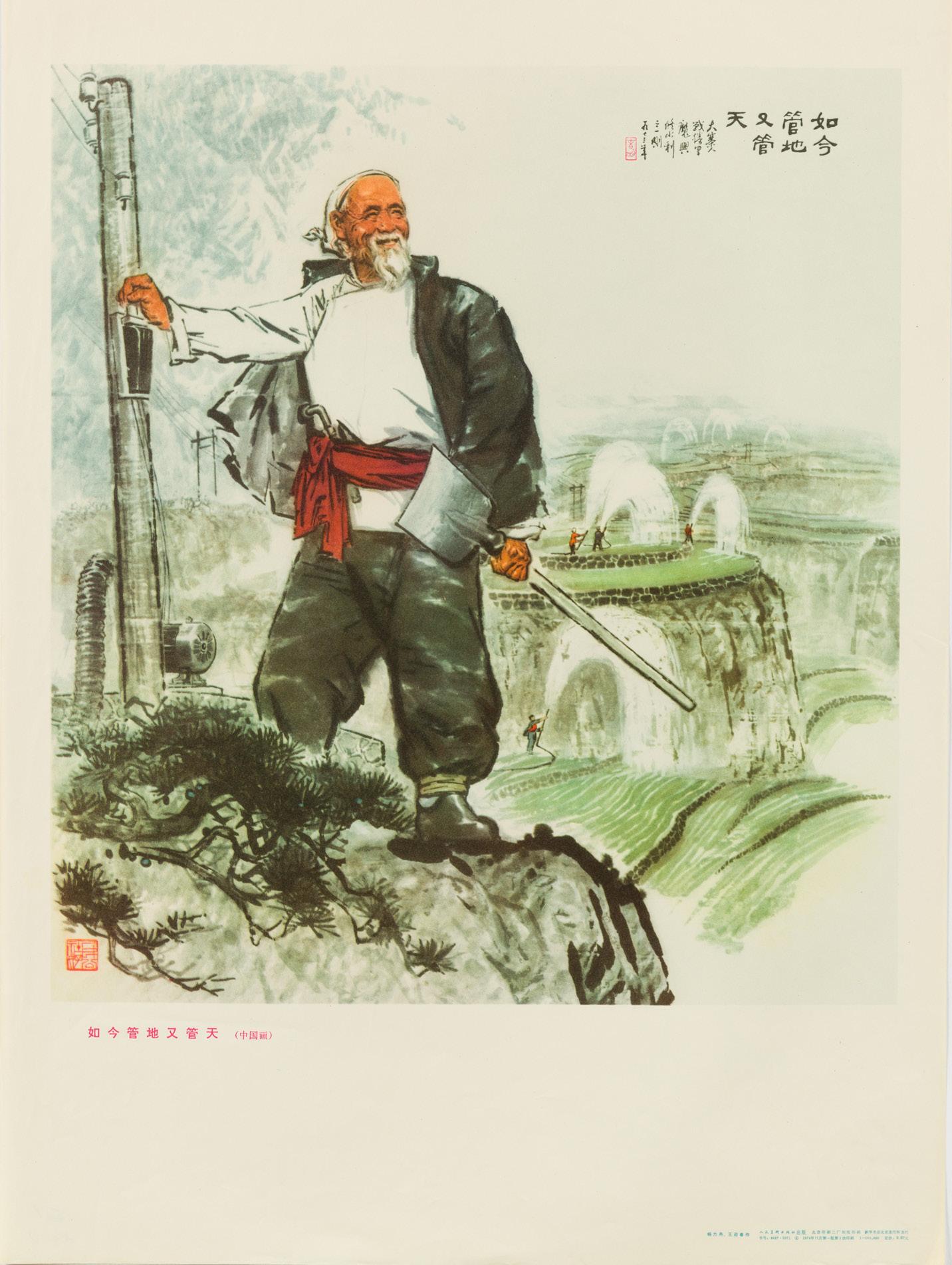

Yang Lizhou and Wang Yingchun

杨力舟和王迎春

Now in Charge of the Earth and Sky 如今管地又管天

1974

Poster Collection Wende Museum, donated by David E. James

This poster, designed by the husband-and-wife team Yang Lizhou and Wang Yingchun, depicts a burly, smiling peasant, who holds a large shovel in one hand and flips an electrical switch, attached to power lines and a generator, in the other. He looks out over terraced fields where other farmers use hoses to water the crops. The painting mixes politically correct subject matter—the taming of nature and modernization of the countryside with the introduction of running water and electricity—with traditional ink painting styles and motifs, including the gnarled pine branches at the bottom left and loose application of colored wash to render the rocks and fields.

56

56

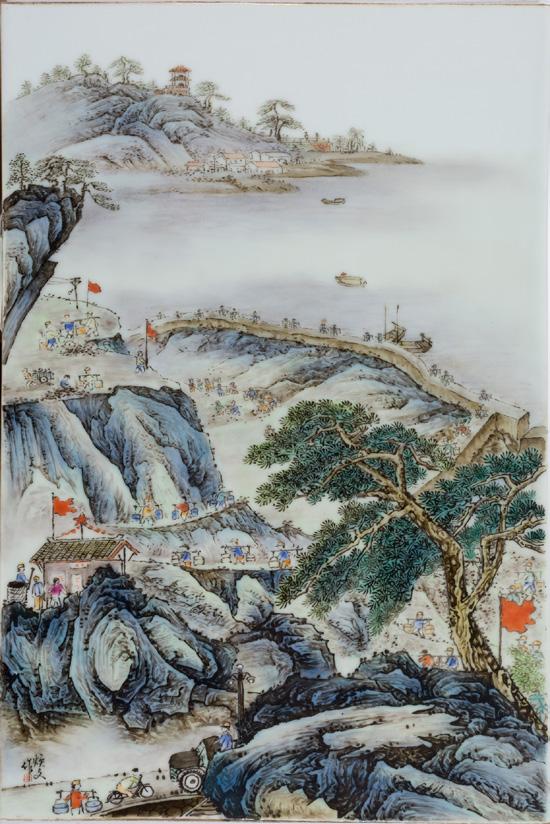

Zhao Huasheng 赵华胜

Striving for Steel at the Front Line 夺钢前哨

1972

Poster Collection Wende Museum, donated by David E. James