6 TRICKY BUSINESS

The David-and-Goliath nature of big-ship medical evacuations.

12 AFTER THE FALL

Hermanus crew uses high-angle rescue techniques to assist a severely injured casualty at Gearing’s Point.

16 MEET VICTOR

How student and volunteer Victor

Mupfururi packs 48 hours into a 24-hour day.

20 TRAINEE TO TRAINER

Following in the footsteps of three NSRI Class 3 coxswains.

24 KIDS’ CLUB

Fun puzzles and safety messages for our young members.

26 THE CHANGEMAKERS

Lifeguard trainers Sam Rorwana and Sarah Sandmann share their passion for empowering people.

30 MORE THAN A BOAT

The important fleet that forms the backbone of NSRI’s operations.

35 STATION AND SPONSOR NEWS

Station and Volunteer Support Centre news, and sponsor updates.

42 SKATES AND RAYS

More about this fascinating and colourful family of fish. 46 NSRI BASE LOCATIONS

CAPE TOWN: NSRI, 4 Longclaw Drive, Milnerton, Cape Town, 7441; PO Box 154, Green Point 8051 Tel: +27 21 434 4011 Email: magazine@searescue.org.za Web: www.nsri.org.za facebook.com/SeaRescue @nsri @searescuesa youtube.com/@NSRISeaRescue

As I write this letter, I reflect on the incredible journey that has brought me to this new chapter in my Sea Rescue career, and I feel humbled to be part of such a fantastic team.

My passion for the NSRI runs deep, spanning three generations in my family. My connection to the sea was sparked by my father, a Master Mariner in the Dutch Merchant Navy. When he retired to Cape Town, he joined Station 8 (Hout Bay) as a shore controller. His stories, along with my childhood spent around water, greatly influenced my path. Whether sailing on the Vaal Dam, white-water rafting, diving along the KZN coast, or ocean sailing, water has always been my playground.

Inspired by stories of crew performing rescues in extreme conditions, my personal Sea Rescue journey started when I moved to Hout Bay in 2007 and joined Station 8. After a few years abroad, I returned to South Africa and rejoined the NSRI 13 years ago at Station 23 (Wilderness).

Moving to a surf-based station was challenging and humbling. It helped me appreciate the incredible diversity in the NSRI, as each station develops unique capabilities based on its environment and needs. Wilderness’s challenging surf tested my skills and deepened my respect for the crew. Under the guidance of station commanders and senior coxswains, I was privileged to participate in several legendary Wilderness surf courses. These experiences fuelled my love for operating our smaller rescue craft in the surf, a skill central to Station 23’s operations.

Over the years, I’ve witnessed both the

triumphs and the tragedies that come with rescue work. We’ve celebrated many successful rescues, but we’ve also faced the grief of drownings. Seeing that sorrow is a stark reminder of why we do what we do.

For us volunteers, NSRI is more than an organisation; our crew is family. The bond formed through training and a shared sense of purpose is remarkable. I also want to acknowledge my wife, Kim, and the families behind each volunteer; we couldn’t do what we do without their support.

And while our crew becomes family, our family also becomes crew. One of my proudest moments was when my sons, James and Sean, joined as crew at Station 23. James later moved to Hout Bay, and completed three generations of volunteers at Station 8. My daughter, Grace, who is 14, eagerly awaits her turn.

I also want to recognise Dr Cleeve Robertson, who leaves big shoes to fill. Cleeve’s leadership and vision have transformed the NSRI over the past decade. Under his stewardship, we have seen remarkable growth, innovation and a fundamental shift in focus towards drowning prevention.

To our donors and sponsors: your contributions equip our crew with the best safety gear and technology. Every time we launch a vessel or don a wetsuit, we are reminded that your support makes it all possible.

As we head into summer, I wish all our volunteers, lifeguards, emergency service personnel, staff and donors the best. Here’s to a safe, successful summer, doing what you do best!

MIKE VONK, CEO

THE PUBLISHING PARTNERSHIP

MANAGING EDITOR

Wendy Maritz

ART DIRECTOR Ryan Manning

COPY EDITOR

Deborah Rudman

ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Bernice Blundell

MANAGING DIRECTOR

Susan Newham-Blake

PRODUCTION DIRECTOR

John Morkel

ADDRESS

PO Box 15054, Vlaeberg 8018

TEL +27 21 424 3517

FAX +27 21 424 3612

EMAIL wmaritz@tppsa.co.za

NSRI

OFFICE +27 21 434 4011

WEB www.nsri.org.za

FUNDRAISING AND MARKETING DIRECTOR

Janine van Stolk

janine@searescue.org.za

MARKETING MANAGER

Bradley Seaton-Smith bradley@searescue.org.za

COMMUNICATIONS MANAGER

Andrew Ingram andrewi@searescue.org.za

PRODUCED FOR THE NSRI BY The Publishing Partnership (Pty) Ltd, PO Box 15054, Vlaeberg 8018.

Copyright: The Publishing Partnership (Pty) Ltd 2024/25. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without the prior permission of the editor. Opinions expressed are those of the authors and not of the NSRI. Offers are available while stocks last.

PRINTING Novus

ISSN 1812-0644

The Morgan Bay community and holidaymakers would like to extend their gratitude to Station 47 (Kei Mouth) for making themselves available to render lifeguard duties on our beach for part of the June 2024 school holidays.

This was put in place after a tragic incident that resulted in a fatality on our beach.

We as a community will endeavour to work towards solving the problem of not having lifeguards on the beach over long weekends and school holidays, and will ensure all efforts are made to have at least two NSRI personnel on the beach during these times.

A big thank you to Nadine and Viwe, who did not hesitate to volunteer to go to the beach for the day after the incident.

We would also like to extend our gratitude to lifeguards Unathi and Mfundo for their time and dedication to the NSRI as well as the general public.

Bravo Zulu to NSRI Station 47 (Kei Mouth).

MONICA MAROUN, Station 47 Station Commander

I donate monthly to the NSRI, and recently a staff member of the NSRI came to my family’s rescue! We were in an accident just outside Elands Bay. Our vehicle was disabled and we were in shock. She pulled over, gave me her cellphone to contact my insurance and she contacted the police. We had no cellphone network coverage and if she hadn’t stopped, I don’t know how we would have obtained the help we needed as the road was very quiet. Another gentleman pulled over after he saw the NSRI vehicle and recognised the driver, Nicole Anthoney. This gentleman ended up driving me and my family home to Cape Town. I would just like to honour and thank Nicole for stopping, for showing kindness and care, for making sure we were in safe hands and for answering my insurer’s and the tow truck driver’s calls as my phone network was not working. Thank you, NSRI, I am now even happier that I donate to an organisation that employs such amazing individuals like Nicole!

CINDY NEWDAY

Medical evacuations from large ships require specialised training not only from an emergency medical care point of view; they also involve manoeuvring small vessels alongside very large ones to get the process going. Cherelle Leong tells us more.

David and Goliath: coming alongside a large container is a task only skilled crew and MEX technicians are able to perform.

In recent years, Sea Rescue has been increasingly tasked with assisting injured or ill crew from large container ships and tankers. With South Africa located on one of the major global shipping routes, it’s no surprise that our major port towns of Richard’s Bay, Durban, Gqeberha, Mossel Bay and Cape Town receive frequent requests for assistance. So much so that the NSRI developed specialised maritime extrication (MEX) training to equip crew with the skills they needed to conduct these operations safely. And safety really is the operative word here. As large as our Class 1 vessels may appear, especially our 14.8m ORC, they’re tiny when seen alongside ships that are 200 to 300m in length and rise several storeys above the water line. That dozens of complex MEX rescues

have been successfully carried out is a testimony to the skill, commitment and training of our Sea Rescue volunteers.

We chatted to Class 1 coxswain

Jacques Kruger from Station 5 (Durban) and Station Commander Justin Erasmus from Station 6 (Gqeberha) to find out exactly what goes into a MEX operation and what makes them so complex.

Every part of the operation is methodical from the moment the call first comes in. There are authorisations to obtain and administration to conduct to ensure that all the paperwork from a shipping perspective has been properly processed. Of primary importance is knowing what is medically wrong with the casualty. Has there been an accident, have they fallen ill, and how critical are their injuries?

Typically, while the station commander and Class 1 coxswains are gathering information, crew will be placed on standby for a possible callout. Often ships are still very far from the harbour, and it can take several hours, if not days, for them to get close enough for a medical evacuation. The preference is to operate during daylight hours because these rescues are so technical in nature. Usually this means launching at first light and requires a very early start for crew.

Once at the base, the two MEX technicians set up a staging area to sort and check equipment, and to decide on what’s needed. Simultaneously, crew prepare the rescue vessel for launching and then everyone gathers for a detailed briefing of the operation. The NSRI works closely with local ambulance and medic services. The medics assigned to these calls are typically

familiar with both the boats and crew. It makes for an effective working relationship – vital in these complex rescues.

Before the rescue vessel launches, extensive communications are carried out with the ship. With the experience that comes from conducting many medivac operations, crew have identified the best rendezvous point as being about 2-3 nautical miles (around 4-5km) from shore with plenty of room to steam ahead. This is important because medivacs are conducted while both vessels are in motion. The slow forward movement at approximately 5-6 knots (between 9 and 11km/h) provides a more stable platform to work on compared with a situation in which vessels are stationary.

Of critical importance are the weather conditions. If it is too rough, the safety of both the crew and casualty will be compromised. The final call is made once the rescue vessels are alongside the ship. They’ll pace in the lee created by the ship to judge the rise and fall of the swell and determine the best place to come alongside. The extraction point is also

determined by the status of the patient. If they’re able to walk, the pilot’s ladder may be used. If they need to be stretchered, the clearest line of operation between the ship and rescue vessel needs to be found.

Once the coxswain deems it safe to proceed, the crew get ready to deploy.

The bosun manages the deck area, communicating with the helmsman the position and proximity of the vessels to each other and making the final call about when it’s safe to step onto the ladder. On the aft deck, a rescue swimmer stands fully kitted and ready to deploy in the unlikely event that someone falls into the water.

The first person to board the ship will be one of the MEX technicians. Once they’re on board the ship, they set up a staging area, ready to receive the MEX equipment and medic’s bag. The second MEX technician and medic soon follow.

The priority is getting to the casualty so that the medic can conduct an assess-

ment and determine the best method to extract them. This can be complicated by their location on the ship. If the casualty fell below deck, it can be very difficult to navigate the narrow passageways and stairwells with the casualty now placed in a stretcher.

A critical part of any operation is ongoing communication between the rescue vessel and the ship, between the MEX technicians and the rescue vessel, and keeping the Maritime Rescue Coordination Center (MRCC) updated on the progress of the operation. Sometimes these communications can be challenging, especially when it’s a foreign ship and there’s a language barrier.

Once the decision is made to extract the patient, communications have to be clear and concise, as this is the critical part of the operation. There’s no rushing the process; everything is calculated and methodical, ensuring that safety remains the top priority.

A MEX-trained crew member boards the container vessel.

If the patient is to be lowered in a stretcher, the MEX technicians set up a rope system with pulleys while the medic confirms that the patient is properly secured into the stokes basket. Two additional lines attached to the stretcher will be thrown down to the rescue vessel once it’s pacing alongside. These lines are managed by crew on the deck of the rescue vessel, to help steer the stretcher safely as it’s lowered. Timing is critical. The minute the stretcher is on deck, lines are released. This is to avoid the casualty being lifted up again if there is a sudden swell.

The casualty is then taken into the cabin of the rescue vessel (the ORC has an area specially designed to secure the stretcher). Here the medic will continue to monitor the casualty until they’re safely back at the base and transferred to an ambulance.

Meanwhile the MEX technicians recover all ropes and equipment and lower them down to the rescue vessel before climbing back down the ship’s ladder and onto the rescue vessel. With some final communications to the ship confirming all crew and the casualty are back on board, the rescue vessel breaks away and returns to base.

Depending on the conditions and the casualty, these extractions can take as little as 30 minutes or several hours. It’s always rewarding returning to base, seeing the proficiency of crew in action and knowing another rescue has been successfully concluded.

In August this year, Station 17 in Hermanus put their high-angle training to the test in a challenging rescue operation to retrieve a casualty who had fallen down the cliff at Gearing’s Point in the town centre. By Wendy Maritz

Gearing’s Point is something of a heritage site in Hermanus. It offers magnificent views of the coastline and bay, is popular for whale watching during winter, and features a permanent sculpture collection. There’s plenty of parking, benches and grass patches for

chilling out, artists display their works, and it’s just a short walk from shops and restaurants. The area bustles with people, especially over the weekends during whale season. It has, unfortunately, also been the scene of several falls, some of which have been fatal.

‘The last one was about two years ago,’ says NSRI Hermanus Station Commander Willem de Bruyn. ‘There is a wall there, about waist high, but people still fall. They lean over it, sit or stand on it, and it’s a long, dangerous sheer drop down.’

‘When we got the call that someone had fallen, one of our crew members, Jade Schnettler, happened to be in the area, so I asked her to go and assess the situation,

while I placed several crew members on standby. In cases like this, we need to investigate before we activate so we know what equipment we’ll need and whether we need to launch our JetRIB for a sea-based rescue. Jade came back to me quickly saying that trying to reach the casualty from the sea would be impossible. So, we took our high-angle equipment, Stokes basket, harnesses and splints, and responded to the scene in our rescue vehicle.’

It was Friday, 31 August, and there were plenty of people around. And naturally, curiosity began to draw more onlookers as the rescue unfolded.

‘When we got there, we saw a member of SAPS with the casualty, trying to comfort him. He was in terrible pain. He had fallen on a flat platform surrounded by rocks, about two metres from the sea. The surge was quite big, so we knew we would

need to keep an eye on that, although once we got down there, we realised the tide was receding,’ Willem says.

Senior coxswain Jean le Roux had attended a similar rescue two years earlier and knew of a rocky pathway down to where the casualty had fallen. ‘He was lying in a very awkward position,’ Willem says. ‘He was in and out of consciousness and wasn’t making sense. He was saying something about picking up litter and bottles, and I can only assume that maybe he leaned too far over the wall to collect a piece of rubbish, and fell.’

Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and Critical Medical Care (CMC) paramedics were on scene and took the lead with pain management and primary care, while the NSRI crew began devising a plan to get the injured man back up to Gearing’s Point to the waiting ambulance.

‘We knew we couldn’t haul him up to the same place he had fallen from. There were no anchor points to use, and the wall face was somewhat concave. We’d have to take him back the way we had come down, along the pathway, although that’s a euphemistic way to describe it,’ Willem says. ‘More like steep steps carved out of the rocks.’

In the meantime, Overberg Fire and Rescue Services had also responded, bringing with them ladders, which would prove to be vital in the crew’s rescue efforts. The casualty was given the necessary primary care from the paramedics, while the NSRI crew assisted with getting him splinted and into the Stokes basket. Up above, the area immediately around the rescue had been cordoned off by SAPS. ‘People were leaning over to take photographs, putting themselves and us in danger if they were to fall,’ Willem says.

Thanks to a group effort, the casualty is carried safely the rest of the way to the waiting ambulance.

‘We placed two ladders side by side against the steepest part of the path, one at the lowest angle we could manage. We anchored our high-angle gear at the top, then connected the ropes to the Stokes basket. The casualty was pulled up vertically along one ladder, while a crew member climbed the adjacent ladder to keep the

basket stable and talk to the casualty. We decided to pull him up vertically for this section of the path, as we wouldn’t have had much control over the basket if it was horizontal.

‘When we got him to the next platform, the paramedics assessed him again, and then we were able to carry him the rest of the way, and carefully transfer him over the wall, where a CMC ambulance was waiting.’

Willem estimates the casualty had fallen about 10m, the equivalent of between two and three storeys. ‘When we were with him, he kept saying, “Please, please, save me, I have two beautiful children…” Words Willem won’t forget in a hurry.

THANKS TO THE CREW INVOLVED: Jade Schnettler (our eyes and ears), James Janse van Rensburg (Deputy Station Commander), Edrich Kotze (our MEX specialist), Jean le Roux (who knew the way down), Niel de Vries, Garth Els and Johann Koekemoer.

Our thanks to Ingo Winckelmann for sharing the photographs he took. Ingo and his wife are NSRI supporters and were spending the weekend in Hermanus when the rescue unfolded.

Smart, hard-working and dedicated, Table Bay crewman Victor Mupfururi is a shining example of a volunteer who puts his hands up as often as he can: to learn, to grow and to serve.

By Wendy Maritz

Most of us do our business in a 24-hour day. After chatting to 23-year-old Victor Mupfururi, one could almost believe his day contains 48 hours. Aside from his NSRI duties at Station 3 (Table Bay), Victor studies and works, but is quick to add that he is good at multitasking. ‘I work, I study. I’ve been juggling things for most of my life so it’s not too difficult really. And when I have exams, I inform the crew, and they understand.’ Victor, 23, works part-time as a floor-plan auditor at a major South African bank, and is an assistant tutor at university, where he is in his third year of computer science studies. His multiple commitments have taught him ‘how to make those horses you’ve taken to the water drink’, he says, smiling.

Victor joined Table Bay in 2019, and admits he knew nothing about the sea, and had no seafaring experience. His father is a regular and loyal NSRI donor, and Victor happened to meet a few of the organisation’s promoters, whom he describes as ‘fabulous’ people. They made such an

impression on him that, together with a gentle nudge from his dad, it prompted him to join as a trainee crew member.

Being a trainee can be a little unsettling and Victor credits Lourens de Villiers with helping him stay the course. ‘I had some great help and motivation from Lourens, who has since moved abroad, but without him, I would not have been able to push myself as hard as I did. I would probably have quit if he was not there.’ But Victor is quick to acknowledge the whole base and his fellow volunteers. ‘As with most things in life, at the NSRI it’s a group effort, and I owe everyone at Station 3 my thanks,’ he says.

new day begins with an early morning callout – the calm before the action.

This togetherness is not uncommon at NSRI rescue bases. Volunteers have a common goal and purpose; they spend a lot of time together, training, going on callouts and attending debriefs. Each crew member brings something to that group dynamic. Volunteers know that rescues can have positive or negative outcomes; this is the nature of what they do. ‘There is a good support structure here,’ Victor says. ‘When things go wrong, we have a debrief and we talk about it. We also use the time to discuss how we can be better. We practise repeatedly until we are comfortable and confident with a scenario, until we can do it in our sleep. This helps to get past all the stuff going on in your head.’

While Victor has experienced some dramatic rescues, he recalls one of the first he went on, which got him into a spot of trouble. ‘It was December,’ he says, ‘and a

yacht had lost engine power and we went out to assist with a tow to the Royal Cape Yacht Club. It was a scorcher of a day. I remember this callout because I had a date, which I missed because duty called. The tow went well, and I even took a dip in the ocean to cool down. But my date was not happy.’

The NSRI has invested much time and many resources into developing drowning prevention strategies and Victor is onboard with that too.

If Lourens was the driving force behind Victor’s staying power as a rescue volunteer, Survival Swimming instructor Alison Cope was the reason he was inspired to join the Survival Swimming squad.

‘I’ve seen children transform in front of my eyes. Once they can float, their body language changes, there is a light that goes on in their eyes, and that smile…’

Alison Cope, Survival Swimming instructor

‘The reason I originally joined was the same reason I learnt to swim: a kind lady just wanted to see me smile. That is the reason I enjoy teaching survival swimming to the kids. I am passing on that smile that I was given. She was patient and kind, and dedicated her time to helping me improve my, at the time, dismal swimming skills. Her name is Alison. There are no words I can use to describe her and Lourens’s contribution to my life at Sea Rescue. Words aren’t enough – that’s a cliché, but that doesn’t mean it’s not true. Coming from a background where I was not exactly familiar with the water and,

dare I say, I feared it, and taking me to being able to confidently swim in the open water and participate in rescue exercises with the Air Force was amazing. I guess, simply put, I will never forget them, they will forever be in my heart.’

Aside from being a crewman and Survival Swimming instructor, Victor is also involved in the Coastwatchers. ‘People with a good view of various spots around Table Bay and the general coastline are recruited and they typically serve as our first line of communication, as they live nearby and closely monitor the area, helping us assess potential callouts and determine the risk factors involved.’

His future plans? ‘I would love to be a coxswain; it would complete the circle of having a car licence, a pilot’s licence, and a coxwain’s ticket! It would be quite the achievement, a trifecta of sorts,’ he says smiling. ‘If the opportunity to become a coxswain is presented to me, I will welcome it with both arms.’

His trifecta wish is his guiding light, particularly the flying part. ‘I would still love to complete my pilot’s training – funding pending – and do that for a living,’ he says candidly. ‘If not that, I would love to be a lecturer (teaching runs in the family) or a data scientist after completing my studies.’ He pauses. ‘Those are good options, both equally appealing… But being a pilot is still my top choice.’

If success is measured by heart and soul, a willingness to try something new and stay the distance, to overcome the fear and find the smile (and teach others to smile too), while aiming for wings to fly, then Victor Mupfururi is well on his way.

Performance

Following in the footsteps of three NSRI Class 3 coxswains. By

Cherelle Leong

The Class 3 coxswain assessment starts on a Thursday and the intensity doesn’t stop for the next 72 hours. It involves theory exams, ongoing practical boat-handling skills assessments, and 2am rescue scenarios. There’s little time for sleep and zero time for relaxation, and the trainee coxswains are always wondering what form the next challenge will take. But when the weekend’s done and they receive a pass, there’s not much that matches that sense of accomplishment.

I chatted to three of NSRI’s Class 3 coxswains who have recently qualified and they shared their feelings of achievement. For all of them the journey to get there

Station 44’s (St Helena Bay) Devon Wild qualified as a Class 3 coxswain after extensive training with Station 4 (Mykonos).

was intense. It required many hours of training, learning their weaknesses and building on their strengths. What’s interesting is that everyone has had a different learning journey and each of them has benefited from cross-station training.

Devon Wild is a Class 3 coxswain at Station 44 (St Helena Bay) – a satellite station of Station 4 (Mykonos). He qualified in September 2023 after extensive training with Station 4. His approach was not to try and rush the process but rather to take time to understand both the theory

and the practical elements of becoming a coxswain. This involved training as often as possible with different coxswains, learning from their different points of view and accepting constructive feedback. While the same standard operating procedures are used, each coxswain has their own style of operating and communicating with crew. The more coxswains you train with, the more it helps you develop your own leadership style.

In fact, this is one of the most important aspects of training. Becoming a coxswain requires proficiency in three primary areas: boat-handling and technical skills, theory with a strong focus on naviga-

Becoming

a coxswain requires proficiency in three primary areas: boathandling and technical skills, theory with a strong focus on navigation and collision regulations, and crew command and decision-making.

tion and collision regulations, and crew command and decision-making. Typically, most trainees will show potential in one or two of these areas, but few have all three. Acknowledging areas that need work, accepting feedback and learning are all essential parts of the process.

After qualifying as a Class 3 coxswain, the realisation of his new responsibility was a wake-up call for Devon. Throughout his training, there had always been

Hout Bay Class 3 coxswain Renier Combrinck was elected training officer for the station shortly after qualifying.

another coxswain on board; now he alone would be responsible for making decisions and ensuring the safety of his crew. He needed to be confident in his skills and his ability to make the right decisions. More than that, he would now also be involved in training the Class 3 and 4 coxswains and helping prepare them for their assessments. With a chuckle, he readily admits that there’s nothing like having to train others to sharpen your own skills.

This sentiment was echoed by Renier Combrinck of Station 8 (Hout Bay). No sooner had he qualified as a Class 3 coxswain than he was given the responsibility of being the training officer at the base.

For someone who is quite reserved by nature, it was a challenge: he had to learn not only to trust his skills and decisionmaking, but also to command with more confidence. He has been instrumental in working with trainee coxswains from Stations 2, 3, 16 and 8 to help them prepare for their assessments.

Renier participated in the coxswain’s development course at the start of his journey and it highlighted specific areas that he had to work on. For him, it was all about putting in the hours and focusing on developing technical skills first. He didn’t want to be worrying about how to manoeuvre the rescue vessel alongside a casualty while having to make decisions as the rescue situation unfolded. When that happens, it’s easy to get overwhelmed and make mistakes.

Renier participated in the coxswain’s development course at the start of his journey and it highlighted specific areas that he had to work on. For him, it was all about putting in the hours and focusing on developing technical skills first.

What really tests this is scenario training: simulating rescue situations where trainee coxswains have to identify priorities and make decisions under pressure. It’s also the ideal way to hone technical and communication skills. Renier continually came up with new scenarios to

challenge the trainees, letting the situations play out so that they could make decisions independently. Then at the debrief, feedback would be provided on what could be improved on.

Simphiwe ‘Sam’ Rorwana from Station 16 (Strandfontein) participated in several of these scenarios at Station 8. He needed to become familiar with the larger 7.3m RIB for his assessment. In addition, Strandfontein is a surf-launching station with a 5.5m RIB and several JetRIBs. For the Class 3 assessment, coxswains need to be able to pace and come alongside larger vessels, as well as tow and raft up alongside them. Exercising with Station 8 (Hout Bay) and Station 10 (Simon’s Town) gave him an opportunity to practise and gain a level of confidence in these skills.

The highlight for Sam on these training exercises was discovering how to work

with crew he wasn’t familiar with. It helped him prepare for the coxswain assessment where he knew he’d be operating in challenging circumstances, particularly during the night scenarios when everyone would be cold and tired and under pressure.

On the theoretical side, Sam’s approach to preparing for his assessment was to leverage every resource available to him. He studied the theory on NSRI’s e-learning platform and joined the Monday Masterclasses. He would then work through questions, answering as much as he could and highlighting what he didn’t know. Then, to fill in the gaps, he’d approach Station 16’s training officer and together they’d set up a training module for the crew. Sam didn’t just want to know the answers or

learn them, parrot fashion, he wanted to understand the process well enough to be able to explain it to others.

When asked what advice they’d give to trainee coxswains just starting out on their training, there was one recommendation that stood out: No matter what your level of knowledge or skill, be open to learning and be receptive to feedback.

It’s the blind spots that can trip you up, and no-one knows everything. There’s always room for learning and improvement, and most of that starts once you’ve qualified as a coxswain.

OPPOSITE Renier Combrinck. BELOW

Coming from a surf-based rescue station, Sam Rorwana trained with Stations 8 and 10 to hone his boat-handling skills.

We’ve put together a guide for parents and children so we can all be safe, and still enjoy summer-time fun.

● Only swim where there are lifeguards on duty. It is safest to swim between their flags.

● Parents, always accompany small children in or near the shallow surf.

● Consider others and the environment, and don’t leave bottles or plastic on the beach.

● Take an umbrella, enough water and put on sunscreen if you’re going to the beach for a couple of hours.

● Don’t use pool inflatables at the beach: these are very light and can be blown out to sea very easily and quickly.

● Call 112 in the event of an emergency.

● Don’t climb over fences to get to the swimming pool.

● Even if you’re a strong swimmer, never swim alone.

● Parents, install taut swimming-pool covers over your swimming pool and keep these on when the pool is not in use. Pools must be fenced and remain locked, making them inaccessible to children.

● Portable swimming pools (mini pools) pose as much risk to small children. Ensure these are covered when not

Don’t leave water in buckets or tubs outside, or in the bath in the home.

For the last three years, Simphiwe Rorwana and Sarah Sandmann have been involved in training lifeguards along the Wild Coast, West Coast and Agulhas and, more recently, at inland venues. These endeavours have been richly rewarding for both of them. We chatted to them about their deep love for the ocean and its conservation, and their passion for empowering people so they can pass the baton to others in their communities. By Wendy Maritz

Simphiwe ‘Sam’ Rorwana’s relationship with the ocean started long before he joined Station 16 (Strandfontein) as a trainee crew member about eight years ago. He grew up on the Wild Coast in the Eastern Cape, where his father, ‘Rock’ Rorwana, worked in the former Transkei Defence Force’s uMkhosi Wamanzi diving unit. ‘You could say I was

indoctrinated from childhood,’ Sam says smiling. ‘I always looked at my dad’s gear, the wetsuit, the fins, all the stuff I wanted to try on, but couldn’t fit into yet. But I did swim every chance I got.’ The family moved to Cape Town when Sam was 12, and because they lived close enough to the ocean, he was able to enjoy what he loved most, having been taught the skills

by his dad, whose passion, it seems, runs as deep as Sam’s.

Sam, who loved the idea of flying as a child, realised that swimming, and more especially free diving, gave him the same feeling of freedom he’d imagined flying would. ‘The ocean is my sky,’ he says. And when you love something this much, when it’s your life, it seems inevitable that you’d not only want to share it with others, but also want to contribute to them doing it safely. While serving as an active crew member at Strandfontein has taught him the ins and outs of rescue work (he recently qualified as a Class 3 coxswain), his work with I am Water has allowed him to share his love for the ocean and ocean conservation with children. ‘We teach children how to be comfortable in water and show them the magic of the sea.’

Working and volunteering mainly on the False Bay side of Cape Town allowed Sam to get to know pockets of the community, but it also taught him the value of empowering people. He loves to tell people to ‘get out of the box’, try something new. But he also realises, to do so, people need encouragement, and a patient and relatable teacher. It’s not unsurprising that he was asked to join the NSRI’s Survival Swimming and Water Safety teams, so in addition to his crew work, Sam has also taught these life-saving skills at schools in and around the False Bay coastline. When you do a job well, you’re going to get more jobs to do. And it helps, of course, when people like you. A lot. Sam is much-loved and respected in the NSRI family and community at large. He is fit, a natural leader and motivator, and ‘meets

OPPOSITE Coffee Bay lifeguards. ABOVE Lifeguards take a steady run down to Mdumbi lagoon for training.

people where they are’ in everything he does. ‘He really is for people,’ commented one of Sam’s trainees. Because Sam hails from Mthatha, NSRI Operations Manager Bruce Sandmann identified him as the ideal person to call on to help roll out the lifeguard training in underserviced areas along the Wild Coast, from Kei Mouth to Port St Johns. For Sam, it would be a chance to go ‘home’ and ‘brush up on his Xhosa’, a way to come full circle.

Sam’s training partner would be Sarah Sandmann, a former competitive swimmer,

current swimming specialist and freediving instructor. (Sarah has a history as a lifeguard and was instrumental in the NSRI’s successful introduction of the first NSRI Lifeguard Unit in Melkbos in 2018.) She shares Sam’s love for the ocean and its preservation and feels the same way he does about the sea as a medium for healing and therapy. Importantly, they are compassionate and understand that people learn at their own pace. ‘Seeing each of our trainees as individuals is important,’ she says. ‘We always remember our purpose of “creating futures”.’ This isn’t just about saving lives; it’s about giving people skills that they can pass on to others. ‘We say, “each one teach one”,’ adds Sam. And so, Sarah and Sam joined forces about three years ago, starting in one of the most underserviced areas of the Eastern Cape, the Wild Coast. Their target was to set up lifeguard units in Hole in the

Wall, Coffee Bay, Mdumbi and Kei Mouth. Later, the team also trained lifeguards at Lambert’s Bay on the West Coast and at Agulhas, which services the small coastal towns of Arniston and Struisbaai.

One of the most important aspects of setting up the lifeguard units is to convince communities that the NSRI is there to serve them, and that they’re serious about equipping community members with the necessary skills to form a competent group of lifeguards who can take care of beachgoers and swimmers, and who know what to do when people get into difficulty. Buy-in from the community and its leaders is vital for success. ‘We go in representing the NSRI,’ says Sarah. ‘If we say we’re going to provide them with torpedo buoys, we deliver them. If we say we’ll do training on particular days, then we’re there on those days.’ Sticking to Sea Rescue principles and training protocols lends the gravitas necessary for everyone to take each other seriously. ‘In that way, we want to be indispensable,’ Sarah says, ‘but we’re also not going in there saying we can solve your problems. We’re saying let’s figure out how you can solve them. We want to leave them as self-sufficient as possible.’

The idea is to have a core group of people who can deal with emergencies on the ground. And everyone can play a role, says Sarah. ‘The beach patroller is just as important as the person going out into the water to rescue someone. We teach them CPR and first aid, tell them how to identify rip currents, and in turn, they can tell the children when it’s not safe to swim.’

‘There is a perception that the rescue swimmer is the person doing all the work,’

Sam adds. ‘But the buddy system is very important. When the rescue swimmer comes out of the water with a casualty, the beach patroller can administer first aid, and knows who to call for further help.’

Initially there was a lot of travelling involved for the duo. Training was conducted over two-week periods in each area, after which the team would arrange to return every five weeks to two months for further training and/or assessments. There has been less heavy travelling this year because the Wild Coast units have been doing well. ‘They’re practically self-sufficient, they’ve got the equipment they need and send reports regularly,’ says Sam. Arniston crew are up and running, and community members have expressed their gratitude. They feel safe on the beach, but people are also being employed. One trainee shared his interest in working on the cruise ships and he feels the skills he has learned will give

him a chance to fulfil this dream. Another said that she wanted to be a doctor, but wasn’t able to finish school. But she can still help people because she’s learned first aid and can look out for people in her role as a beach patroller.

While Sam and Sarah quietly go about their business, managing their respective water and ocean-related businesses and offering their skills to the NSRI as needed, there are people out there whose lives have changed forever because of them. The knock-on effect is a huge and long-lasting one.

The NSRI’s fleet of vessels ranges from 4.5m JetRIBs to 14.8m Offshore Rescue Craft (ORCs). We chatted to Brett Ayres, NSRI’s Executive Director: Rescue Services, about these important assets and their capabilities, what they mean to the crew, and how the organisation’s rollout of new vessels is progressing.

By Wendy Maritz

On 19 May 2024, NSRI Gqeberha crew bade farewell to their beloved 10.6m Spirit of Toft, which had been in service since 1998. Described as the ‘backbone of the station’ by Station Commander Justin Erasmus, the rescue vessel had reached the end of her career at sea, but during her time had been instrumental in saving countless lives. The 10m

Brede was built in 1984, and began her service with the Royal National Lifeboat Institute (RNLI) in the UK. Fourteen years later, thanks to the fundraising efforts of the late Tommy Toft, after whom she was renamed, she joined the crew of Gqeberha whom she served faithfully for 26 years. She received a complete refit in 2011, but earlier this year began showing signs of her age. She was retired from the fleet and is now looking for a new owner.

Justin commented: ‘I believe many of the coxswains and crew who served on her for a decent number of calls developed an emotional relationship with her. I’ve heard coxswains begging and pleading with her when the chips were down – “just a little further” or “we’re almost there” – to unmentionable profanities when approaching 28 knots down the face of an 8m swell… But she always brought us home safely. She will be sorely missed.’

For crew to develop an emotional relationship with a boat is not uncommon, explains Brett Ayres, NSRI’s Executive Director: Rescue Services. ‘The volunteers really regard their boats as part of the crew. And it’s always interesting to me how the older boats are spoken about as legends, the way one would speak about people, past crew who made impacts years ago and whose stories and deeds echo in the stations,’ he says. ‘Of course, it’s always exciting when a new boat arrives but saying goodbye to our faithful servants of

the sea is not without sadness. That vessel has taken you out and brought you back safely, often in impossible conditions.’

Brett adds that there is also an incredible sense of passion and pride among crew for their boats. ‘We held a workshop examining the pros and cons of various vessels, and it was fascinating for me to hear how passionately crew spoke about various boat-related topics, like design, propeller pitch and engine size,’ he smiles. ‘Engaging with our volunteers in this way has become part of the culture of the NSRI.

Yes, the boats are important, but just as important are the people, the ones who have to drive the vessels. ‘Crew safety is top of mind but, in addition to that, we also always need to consider the area in which a station is operating, and what boats are appropriate for that stretch of coastline, and how best that boat can serve the community,’ Brett adds.

From a purely functional point of view, NSRI’s RIBs are workhorses, and are purpose built for various rescue scenarios.

‘Take a 5.5m RIB, for example,’ Brett says. ‘What’s different about an NSRI 5.5m and a leisure 5.5? The hull consists of stronger fibreglass, it’s thicker and has more internal bulkheads and stringers [stringers form a grid that holds up the boat’s decks and stiffens its hull] inside to ensure hull integrity.

If you were to try to tow a vessel through the surf using a leisure RIB, the transom [the rear section of a boat that seals off the hull] would probably be ripped off.’

Leisure RIBs have PVC tubes, ours are constructed from hypalon sheet rubber, which is more heat and tear resistant. ‘This is necessary for the types of applications we put the boats through,’ Brett explains.

‘In addition, the hull is deeper and eggshaped for better landing in pounding sea, while leisure vessels have shallower hulls.

The bigger, deeper V-shape of our vessels means they require bigger engines and fuel tanks (made from aluminium) that are situated below deck – this actually gives the boat more weight and therefore stability due to a lower centre of gravity. Leisure vessels typically feature plastic fuel tanks above deck.

‘Our RIBS are self-righting, have hydraulic steering for better manoeuvrability – leisure RIBS don’t, so the steering is stiffer. In fact, there are dozens of touchpoints that make the vessels different and, indeed, more expensive to produce. But they are built for purpose. Our Gemini RIBs are among the best, if not the best, in the world.’

Offshore rescue craft (ORC) After Station 6 (Gqeberha) recently bade farewell to Spirit of Toft, they welcomed their ORC to the station. Built in South Africa by Two Oceans Marine, it is the sixth offshore rescue craft to be deployed to the NSRI’s fleet. At 14.8m long and 4.8m wide, she can be used on rescue missions as far as 50nm offshore, and has an expected lifespan of at least 40 years.

‘In 2019, we began with the rollout of replacing our largest class of vessel, the Class 1 Brede fleet. Most of these boats were built in the ’80s, and many of them would have undergone some kind of refitting between the time they were purchased until now. But there is only so much of that that one can do. Like a beloved car from the ’80s,’ Brett smiles.

‘Modern vessels, like the ORC, display such superiority in seakeeping, there’s really no comparison. It can take on 4m swells at 20 knots, which is impossible on the Brede. Even something as simple as the acoustics… The engines on the older boats are loud as are the rain and wind in heavy sea conditions, and inside the ORC it’s quiet. They’re fully self-righting, have shock-mitigating seating and, perhaps most important of all, can accommodate 23 casualties and six crew. It’s a true workhorse, and can manage between 50 to 100 miles offshore if required.’

There are three Class 2 vessels (Gordon’s Bay, Struisbaai [for the Agulhas area] and St Francis Bay). They are 10.6m cabin vessels with a good offshore range of 40nm, as well as travelling along the coastlines of the areas they serve. They have good seakeeping endurance and crew are well protected. It was a 10.6m that was used for the safe evacuation of more than 20 crew members from a stricken fishing vessel off Shark Point in St Francis Bay (pictured on pg. 31). These vessels can hold six crew and up to 22 casualties.

Station 36’s 7.3m displays excellent landing in pounding surf.

These are 7.3m, 7.8m and 8.8m vessels, ‘the workhorses of the fleet’. They are open (no cabins), but feature a large wraparound gun-turret console that offers some protection from exposure to wind and spray. These vessels can hold four to six crew and up to 10 casualties and can operate up to 40nm offshore. These vessels can be towed via tractor to the beach and launched into the sea from there. ‘We would like to upgrade some of the stations

that are operating with 5.5 and 6.5m RIBS to larger Class 3 vessels,’ Brett says of their future plans.

Class 3 vessels: small RIBs

These are the 5.5 and 6.5 RIBs, and the staples of the NSRI fleet, the working dogs perhaps. ‘The 5.5s came out in the late ’80s, early ’90s; then we rolled out the 6.5m. For us, the thinking behind it was that a longer boat is a better boat. And it is a good vessel,’ Brett explains. ‘The 5.5m has a sweet spot, though; it’s really good for surf rescues, and you sit neatly in the boat. While, with the 6.5m, it feels like you’re sitting on it. There are some subtle differences, but both vessels are very useful for inshore rescues and coastal duties east and west of the base of operations. Capacity: four crew and six casualties.

In 2019, the NSRI embarked on the rollout of the 4.5m JetRIBs. Manufactured by Droomers Yamaha and Admiral Powercats, these are jetski-type vessels that have

been modified with inflatable tubes to give them more stability. ‘The idea was for every station to have this smaller vessel which is purpose built for surf and inshore rescues, as well as for flooding responses inland,’ Brett says. JetRIBs are easy to launch, they handle rough surf well, and have deck space for two crew and up to four casualties. The rollout has been extremely successful, with 41 JetRIBs manufactured and delivered to date. By the end of 2025, the last three will be issued, completing the intended target of 44 JetRIBs.

In addition, the NSRI has several 4.2m inflatables, which can be transported easily, and are used mainly for inland flood response. And two Rescue Runners. ‘We’re holding onto those,’ Brett says. ‘They’re designed to withstand a launch onto a rocky coastal area, and useful for a rescuing a casualty trapped in such an area.’

‘While part of our bid is to standardise the types of vessels, standard operations procedures (SOPS) and training around the country, we have to keep in mind that every station has a unique service requirement. For instance, the Rescue Runner is ideal for Gordon’s Bay because of its rocky shoreline, while a 4.2m inflatable is handy for carrying and launching through heavily duned areas, like Wilderness. There will be idiosyncrasies, and we try to accommodate those.’

Regarding the inland stations, requirements are largely the same, says Brett.

The rollout of NSRI’s JetRIB fleet is on target, with the last three earmarked for manufacture and delivery in 2025.

‘While you’re unlikely to get 4m swells on the Vaal or Gariep dams, you can’t underestimate how rough the water can get, and the ferocity of storms that hit these bodies of water. Ocean-going yachts have sunk in the Vaal, whose circumference is about as long as the KZN coastline.

‘As with coastal bases, we need to consider the challenges faced by that inland station, and equip them with the assets that address their specific needs to serve the community of water users in their jurisdiction. These factors also inform our strategic planning. If we’re aware that infrastructure developments are on the cards in a particular area, and the number of water users will increase, we need to further equip that base,’ he says.

‘We must always be in a position to have an asset and service response that can deal with what’s required.’

In October 2024 Mike Vonk joined the NSRI as its new Chief Executive Officer, succeeding Dr Cleeve Robertson who is retiring after an 11-year tenure.

Mike is no stranger to the NSRI. He has been a dedicated volunteer for 14 years, which culminated in his election as Station Commander of Station 23 (Wilderness). He brings with him extensive leadership experience from his role as CEO of George Regional Hospital.

His passion for the NSRI runs deep, with a family legacy of three generations involved in the organisation. His handson experience and understanding of the operational challenges the NSRI faces make him an ideal candidate to lead the organisation into the future. ‘The NSRI is built on a significant team effort: the NSRI leadership of the board, Volunteer Support

We bid farewell to Dr Cleeve Robertson, who leaves behind a remarkable legacy of growth and innovation. Under his leadership, the NSRI expanded its volunteer base, increased the number of service locations, and achieved significant financial independence. He was instrumental

Centre team, station commanders, coxswains, together with all the volunteers, contribute to its tremendous success. I am looking forward to working alongside all these dedicated individuals,’ Mike says.

Welcome, Mike, may it be fair winds and following seas all the way.

in strategic shifts towards preventive measures in water safety, potentially saving countless lives. These achievements were recently recognised with the International Maritime Rescue Federation’s Lifetime Achievement Award. Thank you for everything, Dr Cleeve, we will miss you, and wish you well.

On 24 and 25 September, the NSRI’s sixth ORC embarked on her maiden voyage from Cape Town to Station 6 (Gqeberha) to begin her service with the crew. Rescue 6’s delivery crew consisted of NSRI Training Manager Graeme Harding as delivery

‘She is going to make a huge difference to our crew safety and the type of operations that we can safely perform.’

Justin Erasmus, NSRI’s Gqeberha Station Commander

coxswain, outgoing NSRI CEO Dr Cleeve Robertson, NSRI Executive Director Mark Hughes, and three Gqeberha volunteer crew members, who sailed Rescue 6 from Cape Town to Mossel Bay. After a crew swap and refuelling at Mossel Bay

on Tuesday 24 September, she arrived at her new home in Gqeberha’s Port of Port Elizabeth late on Wednesday afternoon, 25 September.

‘The crew at Station 6 is very excited about the arrival of our new rescue boat,’ says Justin Erasmus, NSRI’s Gqeberha Station Commander. ‘She is going to make a huge difference to our crew safety and the type of operations that we can safely perform. We are still looking for a naming sponsor, so at the moment, we use her call sign Rescue 6.’

If you are interested in finding out more about the naming rights of this offshore rescue craft (ORC), which will be based at the Port of Port Elizabeth in Gqeberha, please contact Alison Smith on 082 992 1191 or email alisons@searescue.org.za

Congratulations to Sean McHarry, who won a brand-new car in our Car Competition’s second draw for 2024. Sean has been a loyal supporter of the NSRI, and has entered this annual competition every year for the past 20 years. He finally struck gold this year! Two more cars are still up for grabs in 2024. Tickets are just R695, and the funds go directly towards the NSRI’s critical rescue operations.

Go to nsri.org.za/support-us/ nsri-car-2024/ to enter.

Our thanks to Kränzle for the sponsorship of 10 Pink Rescue Buoys. Two were used in a harrowing rescue on Saturday, 5 October. The incident occurred at Bloubergstrand. A beachgoer noticed a woman floating offshore who did not seem to be reacting to the waves sweeping over her. He realised she was in trouble and prepared to assist. At the same time, another beachgoer went into the water with the Kränzlesponsored Pink Rescue Buoy stationed in front of Pakalolo. Unfortunately he did not put the harness around him, so the buoy was swept away from him. The man, now without flotation, nevertheless continued towards the woman. Brandon reached the pink buoy and managed to get it back to where the pair were struggling in the water and used it to keep them both afloat until they could get closer to shore. Without the

pink buoys, this incident could have had a very different outcome. Thank you again, Kränzle, for your kind donation and for helping to save these lives!

To date 195 lives have been saved through the use of these buoys.

To sponsor a Pink Rescue Buoy, go to nsri.org.za/support-us/donate

Survival Swimming Centre (SSC) sponsor, Fluidra delivered gifts of thanks to our SSC instructors around the country. Pictured here are Nkazimulo Nyawose and Moses Mbuthuma from SSC3 at Duduzile Junior Secondary School. The cost per child for a Survival Swimming lesson is R56, and it takes about eight lessons to impart basic water safety skills.

If you would like to contribute, please go to nsri.org.za/support-us/

At the NSRI, we’re constantly inspired by the dedication and creativity of our supporters – especially when that support comes from young people with big hearts. Recently, a few remarkable youngsters took it upon themselves to raise funds for NSRI Wilderness, showing that anyone can make a difference, no matter their age. First, meet 12-year-old Jordan Blaauw. Jordan set his sights on conquering George Peak, using the challenge as an opportunity to raise funds for his local rescue base. Rising before dawn, Jordan completed his climb in just over five hours and raised R4 000. During a special visit to the rescue base (picture above), he handed over the funds to the crew, who were deeply moved by his effort. ‘Climbing George Peak was tough, but I’m proud I didn’t give up,’ Jor-

dan said. ‘The view was amazing, and it felt great to support the NSRI.’

Two more young champions, Mirka Bekker and Imke Swanepoel, both Grade 6 learners from Glenwood House, took part in the Dictus Challenge, raising R3 000 for NSRI Wilderness. Mirka’s passion didn’t stop there – she continued fundraising with her brand, Coffee Cow, selling homemade cookies with help from the Outeniqua Clay Club. Mirka raised R1 270 with this effort.

These young fundraisers, backed by their communities, exemplify the spirit of giving. We’re incredibly proud of Jordan, Mirka and Imke – and grateful to all who supported their incredible efforts to help us save lives.

The 26th Rotary Wine Auction was held at The Westin Cape Town on Thursday, 17 October, signifying another successful milestone in the two organisations’ enduring relationship. Since its inception in 1998, the Rotary Wine Auction has funded several NSRI vessels, vehicles, base buildings and water safety lessons.

The NSRI welcomed 170 guests who enthusiastically participated in the auction, bidding on exquisite wines and exclusive experiences.

Funds raised from this year combined with last year’s event have covered the purchase of a JetRIB for NSRI Strandfontein (Station 16).

This prestigious event relies on the generosity of vineyards, winemakers and wine estates, whose donations are gathered by the hardworking Rotarians from the Rotary Clubs of Newlands and Table Bay.

We welcomed 170 guests who enthusiastically participated in the auction, bidding on exquisite wines and exclusive experiences.

A sum of R391 800 was raised, with an additional R25 000 contribution from The Wine Cellar. Our grateful thanks to Rotary, The Westin Cape Town, The Wine Cellar and the sponsors for their support, and to everyone who attended the event for their generosity. We look forward to seeing you again next year.

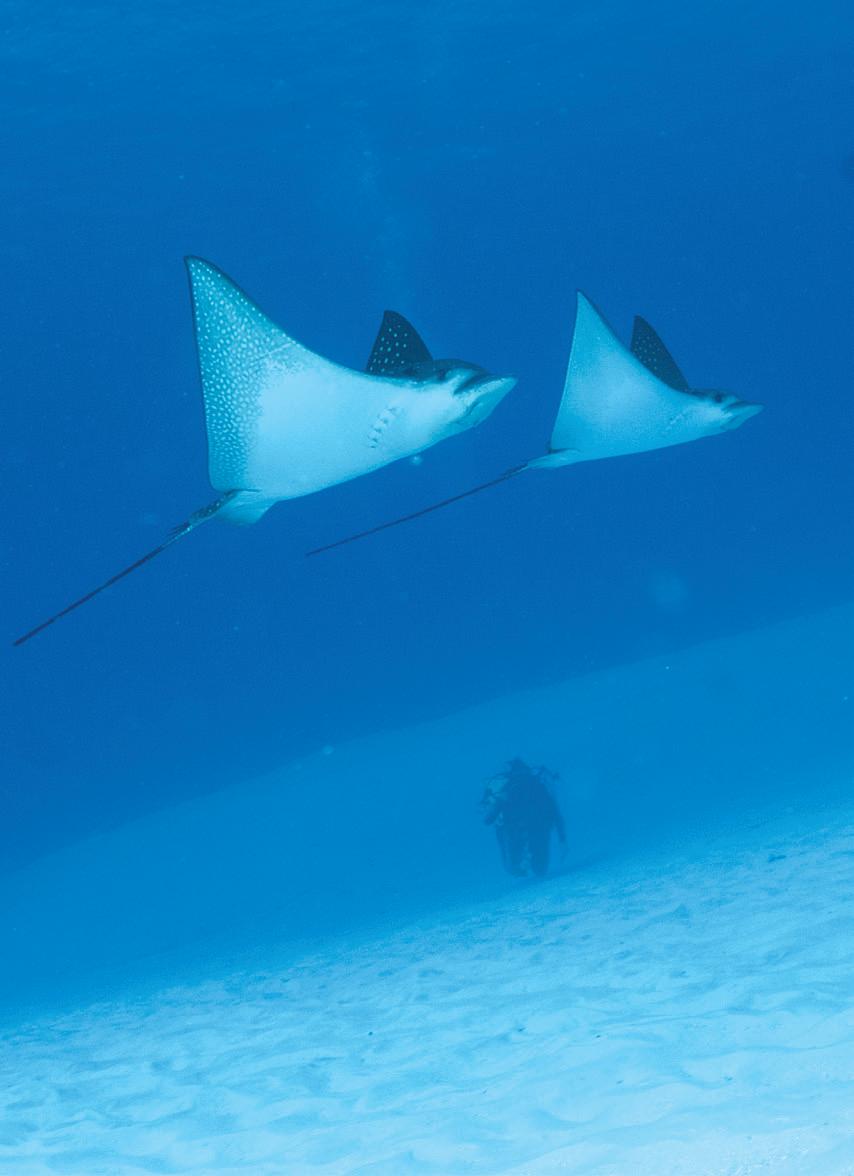

We take a dive to the ocean floor to discover more about flat sharks whose extensive family includes stingrays and guitarfishes. Naturalist Georgina Jones leads the way.

Rays and skates are a group of over 600 species of cartilaginous fishes closely related to sharks. They diverged from sharks 200 million years ago, probably from adapting to the shallow muddy coastal slopes in Jurassic oceans. They have flattened bodies and enlarged wing-like pectoral fins that merge smoothly with their heads. Unlike sharks that have gills on their sides, skates and rays have

gills on their undersides and dedicated openings on their uppersides, called spiracles, through which they take in water for breathing. This adaptation means the bottom-dwelling rays can lie on the sand or submerge under it and still be able to breathe.

This is useful for the ambush predators in the group, such as the electric rays. These species submerge themselves just

Bluespotted ribbontail rays hunt for crustaceans, worms and small bottom-dwelling fishes.

BELOW A onefin electric ray can deliver a shock powerful enough to affect a video screen. BOTTOM Spotted eagle rays swoop through a tropical sea.

underneath the sand and then stun prey with an electric discharge that can be from 8 to 220 volts depending on the species.

The stingrays have one or more spines on their tails that they use for defence.

The spines have a venom associated with them, so accidentally stepping on these animals can be a painful affair. Mantas are pelagic rays with mouths at the front of their bodies, that have adapted to filter feed. The bulk of the rays have mouths on their undersides with rounded teeth for crushing hardshelled prey.

Guitarfishes look like rays but with shark-like tails and are usually bottom-dwelling in tropical to warm temperate waters worldwide.

Skates are by far the largest group of rays and are generally distinguished from other rays by having pelvic fins in two lobes as well as their hardened, usually pointed snouts. All skates and some rays are egg laying, producing rectangular egg cases known as mermaids’ purses.

The females have two uteruses and can produce several sets of eggs in a breeding season. The egg cases vary in size and texture and are specific to each species. They have four protruding horns or tendrils and serve to attach the egg cases to the preferred substrate for the period of development of the embryo. In some species, the mermaids’ purses have

specialised slits for oxygen intake for the developing embryo that are first masked by a protective jelly that disperses as the embryo develops and needs more oxygen. Some rays are ovoviviparous, and the embryo develops by feeding off a yolk within the mother’s uterus. In guitarfishes, the yolk feeds the embryo throughout its development. In most species of stingrays, the yolk only has enough nutrition for about half of the gestation. So when the yolk has been used up, tendrils grow from the uterus lining and extend into the embryo’s mouth and gills, supplying the developing baby with a kind of milk. In a rather ghastly side note, one researcher decided to investigate further and concluded that the milk tastes like sweetened condensed milk, with a fishy aftertaste. Perhaps that might be considered as taking dedication to work a little too far.

All rays have internal fertilisation, so it is essential to maintain contact while mating. This is not easy for animals with slippery disc-shaped bodies and rounded teeth. To ensure mating contact, the adult males in some species develop pointed ends to some of their teeth so that they can bite onto and thus maintain contact with the female. Some species

A biscuit skate, semi-covered with sand, lies in wait for unsuspecting fishes.

completely change their tooth morphology during mating season and then change their teeth back to the rounded crushing shape during non-mating seasons.

In skates, the mating males develop thorny patches on their pectoral fins. These are made up of many low spikes that grow up and then inwards towards the centre of the skates’ bodies. The spikes are up to a centimetre long and help maintain contact during mating. Unwary handlers have learned to treat these thorny patches with caution.

From their early beginnings in those shallow muddy Jurassic seas, skates and rays have spread and diversified, and these days the flat sharks can be found from warm equatorial seas to the chilly depths of the polar oceans and from the surface of the oceans and inshore coastal waters down to over 3 000m in the deeps. It turns out that being flat-bodied is a versatile and evolutionarily successful body plan.

Southern African Sea Slugs is the definitive guide to the 868 known species of sea slugs in Southern Africa as documented by a dedicated group of researchers and naturalists. Photographs and illustrations identify the species, their known variants and egg ribbons. The text gives details of size, distribution, external anatomy, identifying characteristics and natural history. On sale to NSRI supporters at a discounted rate of R700 until 15 January 2025 on www.surg.co.za. Part of the sale proceeds will go to NSRI.

Have some fun and colour the skate in your favourite colours!

Skates and rays are amazing creatures of the sea and can be found in icy polar as well as warm tropical water. Test your knowledge and see how many of the questions you can get right. Don’t peek at the answers.

1. If a dog is a canine, and a cat is feline, what is a fish?

2. What is another name for rays and skates?

3. What do skates and rays use to breathe with?

4. What are their egg pouches called?

5. At up to what depths can they be found?

6. How are the little embryos fed?

7. How do rays ambush their prey?

8. How do electric rays disable their prey?

See if you can find the following words: Spiracle Spines Skate Electric Shock Horn Ambush Horn Yolk

The NSRI is manned by more than 1 369 volunteers at 131 service locations including rescue bases, satellite or auxiliary stations, inland dams and seasonal lifeguard units around the country.

Strandfontein (West Coast)

Kommetjie Simon’s Town Strandfontein

Survival Swimming Centres

SSC 1: Meiring Primary School

SSC 2: Noah Christian Academy

SSC 3: Duduzile Junior Secondary School

SSC 4: Sponsored on show in Spain

SSC 5: Steilhoogte Primary School

POP Pool 1: Portable pool at Pineview Primary School, Grabouw

› Data projectors and speakers or flatscreen TVs for training

› GoPros or similar waterproof devices to film training sessions

› Good-quality waterproof binoculars

› Prizes for golf days and fundraising events

› Towels for casualties

› Groceries such as tea, coffee, sugar and cleaning materials

› Long-life energy bars

› Wet and dry vacuum cleaners

› Dehumidifiers

› Small generators

› Good-quality toolkits

› Top-up supplies for medical kits

› Waterproof pouches for cellphones

› Tea cups/coffee mugs/glasses for events

NORTHERN CAPE

43 063 698 8971 Port Nolloth

WESTERN CAPE

45 066 586 7992 Strandfontein (Matzikama)

24 060 960 3027 Lambert’s Bay

44 082 990 5966 St Helena Bay

04 082 990 5966 Mykonos

34 082 990 5974 Yzerfontein

18 082 990 5958 Melkbosstrand

03 082 990 5963 Table Bay

02 082 990 5962 Bakoven

08 082 990 5964 Hout Bay

26 082 990 5979 Kommetjie

29 082 990 5980 Air Sea Rescue

10 082 990 5965 Simon’s Town

16 082 990 6753 Strandfontein

09 072 448 8482 Gordon’s Bay

42 063 699 2765 Kleinmond

17 082 990 5967 Hermanus

30 082 990 5952 Agulhas

33 082 990 5957 Witsand

31 082 990 5978 Still Bay

15 082 990 5954 Mossel Bay

23 082 990 5955 Wilderness

12 082 990 5956 Knysna

14 082 990 5975 Plettenberg Bay

EASTERN CAPE

46 076 100 2829 Storms River

36 082 990 5968 Oyster Bay

21 082 990 5969 St Francis Bay

37 079 916 0390 Jeffreys Bay

06 082 990 0828 Gqeberha

11 082 990 5971 Port Alfred

49 087 094 9774 Mdumbi (Aux)

47 076 092 2465 Kei Mouth (Aux)

07 082 990 5972 East London

28 082 550 5430 Port St Johns

KZN

32 082 990 5951 Port Edward

20 082 990 5950 Shelly Beach

39 072 652 5158 Rocky Bay

41 063 699 2687 Ballito

05 082 990 5948 Durban

50 082 990 5948 Umhlanga

19 082 990 5949 Richards Bay

40 063 699 2722 St Lucia

MPUMALANGA

35 060 962 2620 Witbank Dam

GAUTENG

27 060 991 9301 Gauteng

NORTH WEST

25 082 990 5961 Hartbeespoort Dam

FREE STATE

22 072 903 9572 Vaal Dam

51 082 757 2206 Gariep Dam

FOR DEPOSITS AND EFTS

ABSA Heerengracht

Branch code: 506 009

Account number: 1382480607

Account holder: National Sea Rescue Institute

Swift code: ABSA-ZA-JJ

PAY ONLINE: nsri.org.za/support-us/ donate

If you choose to do an EFT, please use your telephone number as a unique reference so that we are able to acknowledge receipt, or email your proof of payment to info@searescue.org.za.

Scan this QR code or visit the link below to pay using SnapScan. https://pos.snapscan.io/qr/ STB4C055

Please use your cellphone number as base/project reference so we can acknowledge your donation.

Scan this QR code or visit the link below to pay using Zapper. https://www.zapper.com/ url/KU1oB

Please use your cellphone number as base/project reference so we can acknowledge your donation.