26 minute read

CONVERSATIONS ON THE FUTURE WE WANT WITH SAEED AL DHAHERI

This year is being called the year of reset or the year of transition. The UN sustainable development goals, SDGs, were adopted in 2015 as a universal call to action to end poverty and hunger, protect the planet and ensure inclusion, peace and prosperity for all by 2030. Many people believe that the COVID global pandemic now makes these goals unreachable and unreasonable. However, there are those who believe that this crisis provides the opportunity to reset the pathways to achieving these global goals in new and previously unimaginable ways. What is certain, is that without active involvement across all borders and boundaries and at all levels of society, UN agenda 2030 is not capable of delivering wide-scale impact. Understanding of the SDGs and actions towards achieving them should be integrated into the everyday lives of leaders, as well as into the lives of ordinary people. We need to reach people in ways that allow them to engage.

In this conversation, we meet with Saeed Al Dhaheri, Director of the Centre for Futures Studies (CFS) at the University of Dubai in the United Arab Emirates, founded in February 2020. And also, of importance to this conversation, Saeed also serves as Chairman of the board of Smartworld LLC, a leading UAE company which provides digital solutions for airports and smart cities, including the world coming Expo2020. So we will be hearing from someone working in the private sector, as well as in academia. Let's jump right in.

Claire Nelson: What is the vision and mission of the Centre for Future Studies and how is it shaped by UN global agenda 2030?

Saeed Al Dhaheri: The Centre for Future Studies at the University of Dubai was established with a vision to be a Centre of Excellence in foresight and future studies in the Gulf and the MENA region in shaping a better future for all. Our mission is to serve and

help our customers from government and businesses to build capabilities in futures thinking and scenario planning through offering different programs and services. For example, we have launched professional diploma courses in foresight, systems thinking, social change and alternative perspectives. We also conduct future studies to address global challenges such as the futures of Education, Energy, and Healthcare and so forth. We recently wrote an article about the future of virtual learning in the GCC and the Arab region and was published in Harvard Business Review Arabia. Finally, we provide consulting services in foresight and scenario planning to our clients in different domains.

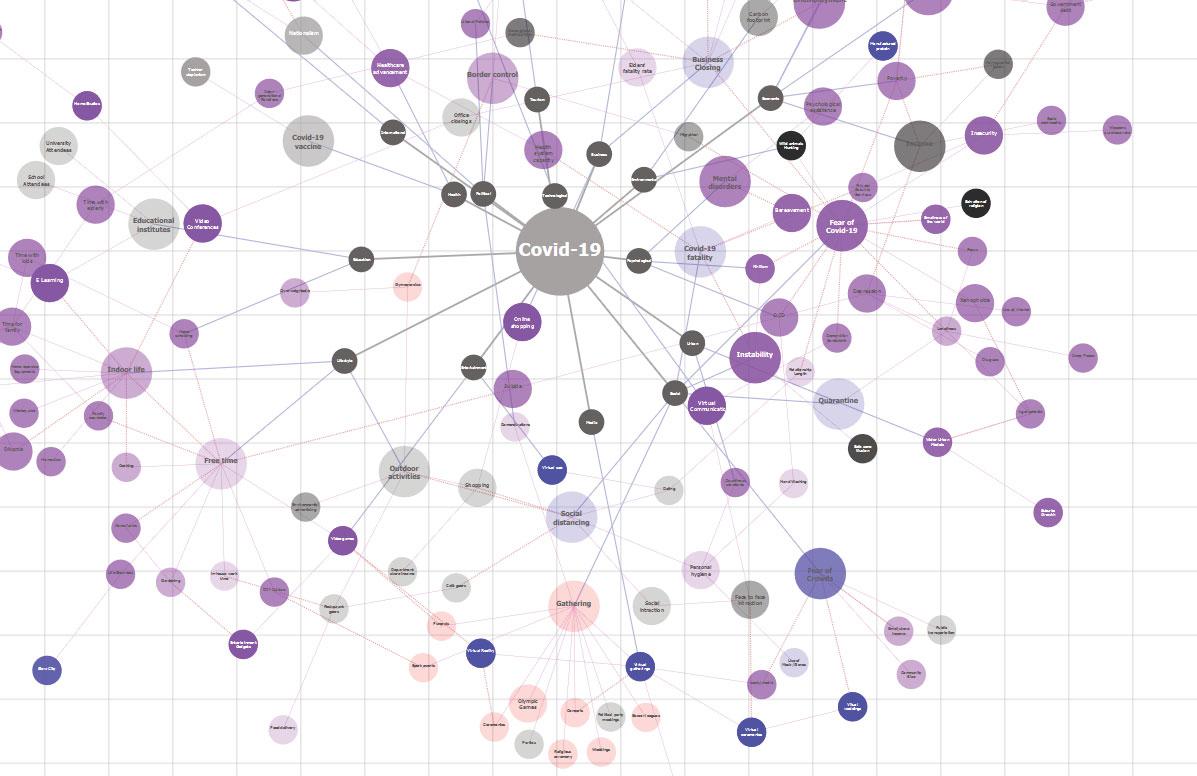

Global agenda is at the heart of our future studies. As part of our foresight methodology, we do horizon scanning – either; short-term 5 to 10 years, or longerterm 15 years and beyond, to look at trends and signals of change and how they might impact our future, or a/the future of a certain domain or industry. Then we conduct scenario planning to envision alternative futures and the desired future. We recently published a report about the world post COVID-19: plausible scenarios and paradigm shift. We have looked at this pandemic and then we analyzed what are the factors that might have contributed to this situation from different perspectives: from human values, ethics and behavior, economic activities, and from society and culture points of view -- and then we have asked how or what should change, as an individual or on a societal level to prevent future pandemics. And what values and ethics we need to live by.

Claire Nelson: I'm an engineer, and so are you. I believe that engineers have a different perspective on the world and they really should be more at the construction of the future. And one of the things that I have been trying to push for is to have foresight and future studies be part of engineering schools, right? Do you think that by creating the Centre, you are beginning to make this change, so engineers have more role in the conversation on the future in policy circles. What are your thoughts on that?

Saeed Al Dhaheri: I believe so. Foresight is a science that can be taught to Engineers and to people from other disciplines. Engineers who use foresight as part of their work can envision better designs for the future. For example, COVID-19 has raised an important issue about re-thinking urban planning and design of future cities. This requires Engineers and city planners to conduct foresight work to re-imagine the future of our cities in order to tackle many challenges such as increasing population, pandemics, sustainability and other issues. This can help provide valuable insight to policymakers to make better informed decisions. That is one of the reasons for establishing the Center for Futures Studies within the college of engineering at the University of Dubai. I think this COVID-19 pandemic has proved that governments around the world need to be vigilant to disruptions, whether it might be a crisis, or a disaster, or a technology disruption. And the best way to do this is to use futures thinking to look at trends and weak signals and assess their impact on society, the economy, and the environment and then establish futureproof strategies.

Claire Nelson: I am of the belief that a systems mindset is critical to achieving a balanced future, a smart future. And when I talk about smart futures in my own philosophy, I am talking about sustainable systems and prepping people to see that (all) of the things we work at ----- energy, water, ICT, space, and of course healthcare, are systems of systems. How do you ensure that your Center is able to reach leaders and policymakers who are already working at the nexus of policy and engineering and politics in the service of creating the sustainable systems and futures? And how do you think we as a futures community can make people

become more aware and wanting to get these skills?

Saeed Al Dhaheri: Indeed, global problems and challenges are systemic problems and need systems thinking mindset to handle them. They must be approached as a system set which is interconnected and interdependent. I think that foresight is now the most important leadership skill of the 21st century. I'm saying this because the ability to effectively manage and harness and leverage the constant change around us is best dealt with through foresight. We live today in a highly uncertain volatile, complex and ambiguous world that is characterized as a VUCA world, which demands getting the proper insight, and acting upon that insight in order to navigate the world effectively. So, therefore, I believe that leaders and policymakers today need to acquire foresight skills. I can see that governments are investing to build capacity and capability by establishing foresight programs and training their staff and administrators in foresight. For example, in 2016 the UAE government has launched its future strategy with an aim of seizing opportunities and anticipating challenges, and so far, has trained more than 120 of its senior and mid managers in a one-year training program in foresight conducted by Oxford University. The goal is to have more than 500 Emarati futurists working in the government in different ministries and authorities to be able to explore the futures of health, education, water and energy, transportation, security and space. The government of the UAE has announced the year 2020 as the year for preparing “towards the next 50”. That means a lot need to be done using foresight to prepare the country for the next 50 years. Our Centennial plan 2071 is a very ambitious vision. Our leadership wants the UAE to be the best country in the world by the next centennial in 2071. We at the Center for futures studies are looking to be part of this transformation and play an important role in this journey and engage with the government in some of these initiatives.

I think we, the futurists community, need to create more awareness about futures thinking and to reach to a wider audience from the public and private sectors to educate and train people in this area through different means and mechanisms. It is sure along way, but the journey of a thousand mile must begin with a single step.

Claire Nelson: I am assuming that because this Centre for Future Studies is at the University, the government is able to mandate that all its offi cials and leaders do this training, and they don't have a choice. So what you have accomplished so far, what role do you see the Centre playing in shaping the SDG 2030 process in Dubai, which has obviously begun, but also in the region, and then of course, in the wider world?

Saeed Al Dhaheri: The Centre plays a leading role in educating, training and creating awareness about foresight. So, building capacity and capability in foresight in the government and the private sector organizations is one of our services. We are looking to start our professional diploma program in foresight from this September. We also conduct webinars and write special reports about the current and future pressing issues, such as “the world post COVID-19 report”, which I have mentioned earlier in this interview. We have received good feedback from the foresight community about this report and we getting requests from futurists from other governments who want to translate the report into other languages and post it on their offi cial websites. We also have established an executive board of well-known futurists and we engage them in some of the projects we undertake. We are looking to play a role regionally since there is a gap in this area that exists in the region which we feel we can address. With the expertise and skills that we have at the Centre, we have started to tackle issues such as the future post COVID-19, and we're looking to address more global issues such as climate change, poverty, education, water and energy, space, and bridging the digital divide between the rich and poor nations.

Claire Nelson: How could your Centre and others, which you personally have infl uence over, create a global community of practice around this challenge, because I fi nd a lot of the futurists who are in academia are not focused on actually addressing the current sustainability challenges of the world right now. So, the academicians ----- and they're doing great work, but not many of them are advocate or activist inclined. How do you believe this Centre that you are the Director of could help create the global community of practice around the challenge of meeting UN agenda 2030?

Saeed Al Dhaheri: We strive to do so. I was recently nominated as president of the digital engineering chapter within the UAE Society of Engineers. We want to promote foresight as a science and promote the use of digital

technologies and sustainable materials in the design and construction of ecological future buildings in the UAE and the region. Foresight can play a big role in engineering when it comes to using new technologies and materials, not just only in the construction industry, but also in other engineering areas as we enter the fourth industrial revolution, connecting the physical, the digital and the biological world in new unimaginable ways to create value and effi ciency in our world. I hope to succeed, to raise awareness and establish a community of practice in this new endeavor. I believe that through my role at the Center for Futures Studies we can spread awareness and create the interest in foresight locally and regionally.

Claire Nelson: When you think about success in the year 2030 in news coming out of Dubai or Paris or Finland or Singapore, what are you seeing for 2030 headlines and stories about what success has happened?

Saeed Al Dhaheri: Success in 2030 depends on how successful we are in ensuring that governments worldwide can work collectively and make progress to achieve the targets of SDGs in terms of ending poverty, protecting the planet, and ensuring prosperity for everyone. I think that foresight will help us to transition from a position of reactive disruption to (one of) proactive transformation. I believe that the SDGs are both part of our legacy here in the United Arab Emirates, and of our plans for the future. Our leadership is very serious about this, and I refer here to His Highness, Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi who fi rst has established the prestigious Zayed sustainability prize in 2008. In his recent address during the last virtual G20 summit, held in Saudi Arabia in February 2020 that was chaired by Saudi Arabia King Salman bin Abdulaziz, he recalled a statement posted by King Salman calling for global unity in fi nding a response to the coronavirus pandemic. We see also his visible leadership drive in advancing renewable energy. Also, during the COVID-19, UAE played the role of donor to many countries. We see this as part of our [UAE] legacy to create a better world that we can all live in happily.

Claire Nelson: One more question. If you would wager a guess, how close are we to achieving the SDGs especially in healthcare in 2030? 50 percent? 75 percent?

Saeed Al Dhaheri: Futurists does not make predictions because often predictions are wrong, but rather anticipate the future. We are far from achieving the SDGs by 2030. There are two views about this. There is a view which says that the pandemic is going to delay progress towards achieving the SDG. And there is the optimistic view for those, including myself, who see COVID-19 as a chance for us to reset and to reboot our societies and accelerate progress towards achieving the SDGs. I hope that by 2030, if we can achieve 60-70% of the SDGs, I think that would be great. But that would require unity from leaders around the world. Unity from governments to work collectively to achieve those goals. Another of my goals is to start teaching the principles of futures thinking in our schools ---- in high school, and even in elementary schools in a very simple way, to be able to infl uence our children, to think about the world they will live in, in the future. If the leaders today cannot agree on climate change and binding SDGs, then I hope that our youth and our children, the future leaders, will feel more compelled to agree on those issues.

Felipe Arocena EPPUR NON SI MUOVE

he world has stopped. For the fi rst time in our lives we see a planet that has come to a standstill. There are no fl ights between the United States and Europe, the two most infl uential areas for decades. China closed its borders to the outside world and immobilized 1.2 billion people. The Asian giant paralyzed the world economy and left a fl eet of ships adrift, many of which had set sail from South America, some from Montevideo transporting wood and meat that were left without destination. Today, half of the species is confi ned to their homes. There are no tourists on the Taj Mahal. Since February Mecca does not receive any more crowds of Muslim pilgrims. The pyramids of Egypt are at rest. The Rue Mouffetard no longer sells crepes and its cobblestones shine polished by the soles of other shoes that today do not walk it. Nobody pisses on the Place de Saint Sulpice anymore. Broadway is deserted and the lights on its canopies look like lux tubes left on in a night kitchen without a cook and with the family asleep. The 9 de Julio in Buenos Aires, the widest avenue of the world, doesn't have the swarm of Renaults or taxis zipping around the hundred and forty meters of asphalt surrounding the obelisk. In El Alto, the Aymara do not sell cheap tools, diapers and trinkets at the fair. I look at the sky and I don't see any white lines from the jet planes, as we used to say in childhood. I go out to the balcony and Richard, the unfailing and vocal valet, is not there. Noon arrives and the noise of the teenagers in the high school is not heard. The world has come to a halt. I never thought it possible. If they had told me a year ago that this was going to happen I wouldn't have believed it. I mean, not the new fl u pandemic for which we have no vaccine, that was very likely to happen. It had been anticipated and was part of the collective imagination. What I would never have envisioned possible is the world coming to a halt. That countries could convince citizens to isolate themselves in their homes. That they would close borders in Europe not for African immigrants, but for the Spaniards, Italians or English themselves. All restaurants have low metal curtains. Hollywood hibernates. Messi, Suarez, Neymar and thousands of footballers train alone in their homes. The greatest show on earth has sent its players to safety. Billions of dollars frozen. The Olympic Games are postponed. Wimbledon is cancelled for the fi rst time since World War II. Teachers give virtual classes to students locked inside four walls. Brothel beds are cold. The wars have died down and the ineffable Colombian ELN proposed a unilateral truce. Tesla offered to derive his career from automotive automation to manufacture mechanical respirators. What paradox is this that we are experiencing? In the century of the greatest technological and social acceleration, the world has come to a standstill. We have been able to stop it! This time in response to the terror of a deadly contagion and in defence of the humanist values of preserving the lives of the weakest. On this occasion the cause was an urgent reaction provoked by fear and that is why so many are suffering the consequences of a hard economic crisis marked by growing unemployment, the collapse of companies, the fall into poverty, or the tedium of quarantine. But perhaps, when this pandemic passes, now that we know we can put the brakes on the system, we can think of other causes to slow it down. For example, easing the pressure on the planetary ecosystem could be one good reason, improving the quality of life could be another. Braking does not necessarily have to be synonymous with economic crisis, as it is now. The accelerated capitalist world seemed unstoppable and yet (at least for a short time, because it will be readjusted) today it is not moving. For a skeptic like me this has been a singular discovery.

THREE FUTURES FOR COVID-19 VACCINATION: THE OK, THE BAD, AND THE UGLY

Introduction

COVID-19 vaccination is of critical importance. Many aspects of global affairs in the coming years will be determined by key questions regarding vaccination, such as development success, development actors involved, vaccine distribution patterns, and access rates across populations. Below, we present three alternative scenarios on possible outcomes regarding COVID-19 vaccine development and distribution within the context of state and institutional decision-making, with particular attention to socio-economic and geopolitical consequences. They are differentiated as follows: “The OK” (multiple vaccines developed and distributed), “The Bad” (only one vaccine developed and distributed), and “The Ugly” (no vaccines developed). Each future transpires according to parallel themes that diverge according to key policy decisions.

We remain confi dent that with careful decision-making and adequate preparation, the relevant international actors can realize the “OK” future, one which, though imperfect, is nonetheless preferable relative to the other futures that we envision. Failure to do so may realize futures closer to the “Bad” or “Ugly” futures that we describe. We advance an “OK” future, rather than a “Good” one, in light of the suboptimal decisions that have already caused suffering to befall populations worldwide and in recognition of the various interrelated epidemiological and governance crises that currently characterize the status quo. We presume the consequences of decisions to be irreversible in the short-term, such that each decision counts. We thus hope to demonstrate the consequential gravity of each phase of COVID-19 vaccination in our alternative futures.

Best Case: The OK Best Case: The OK

Multiple effective low-cost vaccines are developed in adequate supply and distribution chains are decentralized across multiple producers, easing intercountry competition for vaccine access. State procurement decisions follow pre-existing geopolitical alignments. Production of relevant products necessary for vaccines, such as medical glass, is increased.

Vaccines are covered under insurance, but still require copays. However, the untreated populations are small enough to trace. Minority populations are underrepresented in early trials, but vaccine effi cacy across demographics remains uniform. In light of vaccine scarcities, inequitable national-level distribution policies result in uneven access, further exacerbating the structural divisions responsible for such uneven access. Popular anger catalyzes protests demanding new policy or political reform.

In the months that follow, NGOs fi ll the gaps in global vaccine distribution by funding and executing vaccination campaigns in poorer countries and marginalized communities. International organizations provide coordinated leadership and effective regulatory oversight to global vaccine distribution. International bodies are held in higher regard across the international

community thereafter, inspiring renewed commitment toward multilateral collaboration.

Middle Case: The Bad Middle Case: The Bad

Only one viable vaccine is created, which protects from COVID-induced pneumonia. However, upper respiratory tract infections linger, allowing for ongoing transmission. The need for booster vaccines within a year of the fi rst dosage further complicates distribution.

Vaccine effi cacy is suboptimal for disproportionately affected populations underrepresented in trials. Private developers have little incentive to develop another vaccine for non-consuming poor populations, and international organizations and states with weak safety nets fail to underwrite the costs. New social stratifi cations based on treatment are formed, affecting mobility, employment, and access to services. Steroid treatments mitigate mortality rates, but public spending fails to guarantee access. Extensive campaigns by NGOs and philanthropic organizations, along with the development of economies of scale guaranteeing cheap vaccine production, are needed before marginalized communities receive adequate access.

The nation that successfully develops the vaccine acquires greater political leverage, which it uses to extract concessions from other countries in exchange for expedited access following prioritized local distribution. Geopolitical tensions worsen and international cooperation on COVID unravels as states choose to bandwagon with and/or build coalitions against the vaccine-producing country.

Bidding wars infl ate the price for vaccines under development, restricting affordability to a small number of nations. Recipient countries that suffer from endemic corruption and political patronage experience elite capture of distributions. States successful in executing distribution policies provide doses to healthcare workers, the elderly, and at-risk patients. Middle-income states face diffi culties in securing suffi cient international loan fi nancing to afford the vaccine. Low-income states, many already indebted, face less-publicized recurring seasonal bouts of COVID, and take on additional loans that pandemic conditions make even harder to amortize or indemnify.

Organized crime and militant groups fi ll the power vacuum in weak states with minimal state provisions by offering black market vaccines, informal treatment, and other basic services to citizens, gaining local support that translates into enhanced political legitimacy. With ineffective international oversight, hazardous counterfeits proliferate among the world’s disparate vaccine and treatment supply networks. Media conspiracies and internet disinformation campaigns accuse the producing country and company of foul play, generating widespread suspicion, lowering vaccine demand, and hampering progress towards herd immunity. Mass emigration increases, exacerbating global refugee crises and immigration issues, as well as fomenting further ethno-nationalist trends in nations receiving migrants.

Worst Case: The Ugly

Pre-existing geopolitical rivalries and Worst Case: The Ugly tensions prompt states to politicize cooperation on vaccine development, testing, and/or production. Mutual gains are forfeited as states insist on zero-sum policies of fi rst access. Resulting research deadlocks and supply chain impasses prevent the development of a vaccine that is effective and consistent across demographics. The US, EU, and China each launch unilateral vaccine projects, but with timelines extended by years.

COVID mutates from droplet to airborne transmission, causing increased infection rates with pronounced peaks in dense and low-income urban centers. Waves of COVID outbreaks recur around the world, fl uctuating with the fl u, cyclical lockdown orders, and inconsistent social distancing.

AUTHOR AFFILIATIONS:

Hans Khoe, James Boyd, Megan Cansfi eld, Kelsey Weimer - The Millennium Project - Washington, D.C. Hans Khoe - Westmont College - Santa Barbara, CA James Boyd - The New School - New York City Megan Cansfi eld - Peking University - Beijing, China Kelsey Weimer - Dartmouth College - Hanover, NH *Author note: Special thanks to Jerome Glenn at The Millennium Project for his encouragement, feedback, and edits.

As the global depression from indefi nitely interrupted economic activity deepens, global trade falls due to eroding buying power worldwide, and consumer spending staggers to a halt. Commodity prices plummet, causing sharp contraction in the economies of top exporters and particularly in exportdependent economies and fi nancial commodity markets. Small business failure threatens to burst collateralized loan obligation bubbles. Unemployment spikes worldwide, and civil unrest becomes widespread.

As appetites for diplomacy and compromise dissipate, armed confl icts fl are up over long-standing political and social tensions – sometimes in urban areas – and over control of resources in contested regions. Opportunistic political leaders exploit the smokescreen of the crisis to extend emergency power and advance controversial domestic or foreign policy agendas. Targeted misinformation campaigns invoke rhetoric of genetic impurity to blame populations unresponsive to the vaccine, stoking violence. Bioweapon risks grow as state power reshuffl es, population surveillance increases, and eugenic disinformation foments domestic polarization.

As inter-state cooperation diminishes, the capacity of international organizations to enforce multilateral treaties and maintain norms weakens further. An ever-greater number adopt isolationist approaches and ethno-nationalist policies, pushing the conclusion of the crisis indefi nitely into the future.

As we have endeavored to communicate, policy makers involved in vaccine trials, medical research, trade policy, health policy, supply chain management, NGOs, international organizations, law enforcement, private fi rms, ambassadors, watchdogs, banking, fi nance, media, intelligence, migration policy, defense policy, and data analysis – amongst other responsibilities – all have a

role to play in shaping COVID-19 vaccine outcomes. Inter-institutional initiatives for accountability, cooperation, and foresight will be necessary in order to coordinate decision-making, collectively monitor and anticipate decision consequences, and minimize negative externalities. As such, planning and execution of organization must occur at local, federal, and international levels to ensure a suffi ciently vaccinated population. In place of blind optimism, we recommend a broadened scope of responsibility and heightened

Conclusion Conclusion

attention to interrelated actions.

Charlotte Bernard MY IMAGINED FUTURE AS A GEN Z

am Charlotte Bernard, a Gen Z. As you may all know, my generation’s going to live in a world in which climate change and actions against all type of pollution will be part of our everyday life. Thus, I wanted to know more about the impact I could have on my future. I wouldn’t want to spend my childhood hearing about climate change and pessimistic futures without knowing all the possible futures, whether they are great or not. This is why I joined WFSF; to actually understand how futurists work, how they try to write alternative plausible futures we may possibly live and how we escape to the most terrible ones.

Actually, one of the reasons I am delighted to be a member of WFSF is that it gives me exposure to futures thinking. Futurists can envision what potential futures might look like, letting us choose what is our preferred future. And, as a Gen Z, I have a preferred future. First, I wish everyone could change their eating habits. Since many years, one eats meat – and by meat, I mean fi sh and meat - once a day, or sometimes twice a day. Nowadays, many people become vegan, vegetarian or pesco-vegetarian. But I don’t think one needs to change our diet so drastically. If everyone only eats meat two or three times each week, and eats local, the future of our world would change really fast. Second, I wish we could travel less. I don’t mean to stop travelling really far, because I still want to visit different countries in my life, but maybe once every two years instead of every year.

One of the ways to make the world more aware is activism. This has often taken the shape of not going to school, demonstrate, debate, visit countries. Last year, demonstrations where happening in Paris as I was at school. Many schoolmates of my sister’s went to them and missed school. I was happy my school allowed its students to demonstrate.

But with the pandemic of COVID-19, we, I hope for less than 24 months, will have to adapt. We won’t be able to act as before. Great actions were happening all around the world: some endangered species were reappearing in few locations, laws reduced massive utilization of plastic in some countries. Even if we still had a lot to call into question, we were going in a good direction. But, since COVID-19, for health reasons, we use a lot more plastic everyday than before, to avoid the spread of the virus. Without a vaccine, we’ll need to continue this production of plastic. I am worried about what my future will look like and how things will end up if several natural disasters like COVID-19 occur to happen.

In the future, I don’t want to have a lifestyle that is extreme and completely different from what I’m living now. But I know our world will change, and maybe I won’t have the same opportunities than today. This is why everyone should make an effort. It is time for us to change our everyday life, not only because some want to, but because we need to. For our children, for us, for new generations. We need to change our habits to live in a better world.

I was born in France, in 2004. I am a Gen Z. I am currently a high school student, and majors include math, history and English for my “baccalauréat”. I also practice several sports such as dance, jujitsu and play the piano. I am interested in ecology, thinking about and protecting our future, which is why after a visit to Silicon Valley, I joined WFSF (as the 3rd Junior member).