Experiencing the Essence of a Thread:

Textile Artist Nirmal Raja

Now you can stream more of your favorite PBS shows including Nature, NOVA, Masterpiece, Finding Your Roots, Ken Burns documentaries and many more – online and in the PBS app with PBS Wisconsin Passport.

Learn how to sign up or activate your membership at pbswisconsin.org/passport.

Grizzly 399: Queen of the Tetons | Nature

WISCONSIN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, ARTS & LETTERS

WISCONSIN ACADEMY STAFF

Sandra K. Barnidge • Editor

Madison Buening • External Relations Coordinator

Jody Clowes • Director, James Watrous Gallery

Elisabeth Condon • Director of Science and Climate Programs

Jennifer Graham • Exhibitions and Outreach Coordinator

Megan Link • Climate & Energy Program Manager

Erika Monroe-Kane • Executive Director

Matthew Rezin • Operations Manager

Zack Robins • Director of Development

Julie Steinert • Administrative Assistant

Yong Cheng (Yong Cha) Yang • Visitor Services Associate, James Watrous Gallery

ACADEMY BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Roberta Filicky-Peneski • President

Frank D. Byrne • President-Elect

Thomas W. Still • Secretary

Richard Donkle • Treasurer

Amy Horst • Vice President of Arts

Kimberly Blaeser • Vice President of Letters

Robert D. Mathieu • Vice President of Sciences

Tom Luljak • Immediate Past President

Mark Bradley • Foundation President

Steve Ackerman, Madison

Ruben Anthony, Madison

Lillian Brown, Ripon

Jay Handy, Madison

BJ Hollars, Eau Claire

Nyra Jordan, Madison

Michael Morgan, Milwaukee

Kevin Reilly, Verona

Brent Smith, La Crosse

Jeff Rusinow, Grafton

Julia Taylor, Milwaukee

ACADEMY FOUNDATION

Ira Baldwin (1895–1999) • Foundation Founder

Mark Bradley • Foundation President

Jack Kussmaul • Foundation Vice-President

Arjun Sanga • Foundation Secretary

Richard Donkle • Foundation Treasurer

Roberta Filicky-Peneski • Academy President

Frank D. Byrne • Academy President-Elect

Tom Luljak • Academy Immediate-Past President

Kristen Carreira

Betty Custer

Andrew Richards

Steve Wildeck

Editor’s Note

I’m honored to be the new editor of Wisconsin People & Ideas. I’ve been writing about scientists, artists, community leaders, and historical figures connected to our state for almost 20 years, since my freshman year as a journalism student at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Back then, you’d be just as likely to find me in a dusty historical archive as a cutting-edge research laboratory in pursuit of a story, and that dual interest in looking forward to the future while also rediscovering valuable pieces of the past will inform my editorial approach to this magazine. To that end, while crafting this letter, I ventured into the basement of the Academy offices to dig up the oldest publications I could find.

Here’s what I discovered: In 1953, Academy leadership voted to begin producing a quarterly science and letters journal, and the first issue of the new Wisconsin Academy Review appeared in winter 1954. While those yellowing pages aren’t the most scintillating read of all time, I was struck by the opening letter penned by UW President Edwin Broun Fred:

“The most difficult problems confronting us and future generations lie in the field of the humanities and the social sciences … These problems have resulted largely from the changes forced upon us by our sciences and technology, changes we fail to understand completely. We need a better insight into the meanings and implications of science and technology.”

Seventy years later, Fred’s words could easily describe the technological and societal challenges we face now in terms of climate change, the rise of AI, and social-media misinformation, among other issues. We live in a complicated world, just like the postwar intellectuals who edited the first issue of this magazine. Now, as then, it’s clear that our path forward will require bridging a wide range of knowledge-ways to chart a healthier and more sustainable future for Wisconsin—and beyond. I believe these bridges can be built with stories, and there is no better platform for doing so than Wisconsin People & Ideas

On my first day as editor, I attended the Academy’s 2024 Fellows Induction Gala at Promega’s stunning Kornberg Center in Fitchburg. It was immediately clear to me that the Academy’s network is comprised of exceptional, diverse, and inspiring people who are making profound contributions to the present and future of Wisconsin. My aim as editor is to amplify their work and also to put them in conversation with each other—and with you.

This particular issue of the magazine is, in large part, the product of interim editor Brennan Nardi’s vision, and I am also especially thankful for support from Executive Director Erika Monroe-Kane and graphic designer Katherine Thompson at Huston Design in helping us navigate this transition.

I’m thrilled to be here, and I’m very grateful you are, too.

On the cover: Artist Nirmal Raja Credit: Sammy Reed; Courtesy of John Michael Kohler Art Center and Kohler Company

Sandra K. Barnidge, Editor

Ben Jones

VOLUME 70 · NUMBER 3

FALL • 2024

Wisconsin People & Ideas is the quarterly magazine of the nonprofit Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters. Wisconsin Academy members receive an annual subscription to this magazine.

Since 1954, the Wisconsin Academy has published a magazine for people who are curious about the world and proud of Wisconsin ideas. Wisconsin People & Ideas features thoughtful stories about the state’s people and culture, original creative writing and artwork, and informative articles about Wisconsin innovation. The magazine also hosts annual fiction and poetry contests that provide opportunity and encouragement for Wisconsin writers.

Copyright © 2024 by the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited. Postage is paid in Madison, Wisconsin.

WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS

BRENNAN NARDI interim editor

SANDRA BARNIDGE editor

TJ LAMBERT copy editor

JODY CLOWES arts editor

HUSTON DESIGN design & layout

ISSN 1558-9633

Ideas that move the world forward

Join the Wisconsin Academy and help us create a brighter future inspired by Wisconsin people and ideas. Visit wisconsinacademy.org/brighter to learn how.

Wisconsin Academy Offices 1922

Avenue • Madison, WI 53726 ph 608-733-6633 • wisconsinacademy.org

Blue Roof Orchard

From the Director

I recall when I moved to Wisconsin, having been raised as a city girl, I knew no one who hunted. I was completely unfamiliar with hunting culture. At the time, Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) was spreading through deer populations in nearby counties, and the topic dominated news coverage and water-cooler conversations. Listening to reports and voices from around the region, I began to understand the heritage, the hunter’s code, and the practical role of hunting.

This was a lesson not in hunting, but in understanding.

Amid the election cacophony, the Academy has been steadfastly connecting people all around the state and increasing the understanding we have of one another—and the world we share. We are standing on the Academy’s long history of civil discourse to reinforce the common ground and shared values in Wisconsin.

Exploring timeless topics, such as astronomy and how birds navigate via the night sky, feeds curious minds and replenishes wonder. Collaboration on timely issues, such as the changing climate in Wisconsin, raises personal stories from across the state and keeps us cooperating on a path forward. Enjoying work by writers and poets in Wisconsin reinforces our shared humanity. These opportunities are more than a reprieve from this hostile election climate: they are an answer to it.

In November, the Academy will hold the Climate Fast Forward conference in Rothschild, near Wausau. This is a powerful and practical act of hope by a statewide community, and we expect more than 400 people to come together during the event to address climate change in our state. Whether they are farmers speaking the language of soil health and erosion, civil servants fluent in federal funding and policy opportunities, private businesses pursuing sustainability, environmental justice activists, or dedicated nonprofit leaders—all these people care about Wisconsin’s natural world and our shared future.

At this conference, and through all we do at the Academy, we respect one another and know that we need each other to fulfill a better, brighter Wisconsin. I am grateful to you, all the members, supporters, and partners. I’m excited for what is ahead.

Erika Monroe-Kane, Executive Director

Sharon Vanorny

News for Members

MAPPING OUR MEMBERS

While most of our Academy members come from major metropolitan areas, in total they hail from 52 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties, as well as 26 other states and two Canadian provinces. On the map below, shaded counties indicate those with Academy members—the darker the shade the more Academy members there are that reside in that county. The “N=#s” indicate the number of households that are members in that county.

3. SAUK N = 29

1. DANE N = 473

5. SHEBOYGAN N = 20

4. WAUKESHA N = 24

2. MILWAUKEE N = 80

10 PERCENT MEMBER DISCOUNT

Climate Fast Forward is the only climate change action conference in Wisconsin that covers a wide range of climate change impacts and solutions. At this two-day conference, attendees will be able to experience skills-based workshops, participate in collaborative spaces, and hear from engaging plenary speakers.

This year’s conference takes place in Rothschild, Wisconsin, on November 14 and 15 and will bring together changemakers, including seasoned professionals, new voices, and diverse audiences who continue to be most impacted by the effects of climate change. Offerings include workshops, plenary sessions, keynote speakers, and ample time for connecting with fellow attendees. Learn more about the conference and purchase tickets, with the 10-percent member discount, at wisconsinacademy.org/climate-fast-forward-2024.

USE OUR ONLINE ARCHIVES

Enjoy and benefit from a variety of past programming, such as Science on Ice: Why Winter is the New Frontier for Freshwater Sciences and Poetry as a Visual Art, a reading by Madeline Grace Martin. Visit wisconsinacademy.org/publications/video.

BIRDS IN ART

The annual Birds in Art exhibition at the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wausau opened September 7 and will run through December 1. Two- and three-dimensional pieces by 107 international artists working across a range of mediums and subjects are on display. The exhibit includes paintings by Swedish artist Gunnar Tryggmo, who was named the Woodson’s 2024 Master Wildlife Artist. More information is available at https://www.lywam.org/birds-in-art/.

WISCONSIN ART SHOWCASE

The Miller Art Museum in Sturgeon Bay is hosting its 49th Juried Annual Exhibition, which highlights contemporary work by visual artists who live or work in Wisconsin. The exhibition includes artists at all career levels and invites a range of media and artistic practices from traditional to abstract. It’s open to the public through November 9. Full details are available at https://millerartmuseum.org/.

HOT TICKET

The Driftless Film Festival is a celebration of independent cinema hosted at the restored Mineral Point Opera House. The annual festival showcases both award-winning independent films and Wisconsin-based productions, along with meet-and-greets with the filmmakers. The festival will run November 2-9. Learn more at https://driftlessfilmfestival.com/.

LOST AND FOUND

On November 8, the Fox Cities Performing Arts Center in Appleton will host a talk by modern-day explorer Albert Lin, the host of Lost Cities Revealed with Albert Lin. A research scientist and amputee, Lin unearths lost cultural stories and ancient wisdom from Mongolia to the Mayan jungle by using the latest archeological technologies. Purchase tickets to this and other Center events at https://foxcitiespac.com/events-tickets/events/.

HOLIDAY HERITAGE

The Holiday Folk Fair International is one of the country’s longest-running multicultural festivals. A program of the International Institute of Wisconsin, the Folk Fair celebrates the diverse cultural heritages of those who call southeastern Wisconsin home via music, food, dance, and art. The Folk Fair will run November 22-24 at the Exposition Center in the Wisconsin State Fair Park in West Allis. Learn more at https://folkfair.org/.

Picking apples at Blue Roof Orchard in Belmont, Wisconsin.

ONE BEAUTIFUL THING

BY MICHELLE WILDGEN

We are fruit eaters in my house. Fresh, cooked, savory, or sweet— we eat it by the bushel, which is why I signed up for Blue Roof Orchard’s Apple CSA (Community-Supported Agriculture) as soon as I became aware of its existence.

All photos: Blue Roof Orchard

The Apple CSA is exactly what it sounds like: for 12 wonderful weeks, the Blue Roof Orchard fills their trucks with certified organic apples from its Belmont farm near the Iowa border and drops them at roughly 30 sites in and around Madison, Platteville, Paoli, Viroqua, and Dodgeville. Depending on the specific box size, each week CSA subscribers take home as few as three or as much as 20 pounds of local apples, divided into paper bags, which are labeled by varietal and a line or two of description: Sir Prize: Tart, delicate and flavorful, or Initial: Sweet, juicy and aromatic. Eat fresh. You might receive a handful of one type, a hefty bag of another. Either way, my refrigerator has become a kind of Jenga landscape of apple bags, a sight I find gratifying every time I open the doors.

Apples are so ubiquitous in American life that it’d be easy to forget they aren’t native to North America. Jennifer A. Jordan, a professor of sociology and urban studies at UW–Milwaukee and author of several books on food, history, and culture, says they originated in Kazakhstan before proliferating in the United States, where the fruit is now so entrenched that apple types are linked to

particular places, such as Wolf River apples from, well, the shores of the Wolf River. Apples, Jordan says, are just one agrarian link between town and country—like orchards luring city dwellers with music and beer gardens, or a CSA that brings the country to town— but they’re a meaningful one.

“It’s about economic benefit going both ways, and supporting stewardship of the land through consumption,” she says.

In early August, my first apple deliveries arrived and I decided to try a mini apple deep-dive. I labeled six apples by varietal names and left them out in the kitchen for my family to enjoy. Then I eavesdropped.

It’s trying to be Williams Pride and doesn’t quite make it.

Akane tastes like cider.

Redfree made me want to be a bee and just live in it, in my new, juicy home.

Much of this conversation is, of course, totally unhinged, but the ardent intensity is justified. What the first few Blue Roof deliveries

have revealed are the delights of a particular type of abundance. I love the variety and surprise of a vegetable CSA, but there is an inverse, almost meditative quality to trying out many versions of one beautiful thing. The minor variations become amplified: the gradation from pale green to blush to full crimson; the difference from a snappy, puckeringly tart apple you might want to cook with meat versus a sweet, delicately textured apple you want to leave alone. In a world of products with utilitarian or purely marketdriven names, whoever named an heirloom apple gave us something more poetic and evocative (I’m especially excited to get my hands on Pixie Crunch and Winecrisp). To me, these varietal monikers somehow communicate not what you will be if you buy the fruit, but what this fruit is, in and of itself, and some hint of the experience of creating and growing it.

Chris McGuire, who owns Blue Roof with his wife Juli, agrees. The couple grew up in New York City and Hungary, respectively, before settling in Wisconsin. They started the farm—then named Two Onion—in 2003, growing vegetables for markets and then

a CSA. They added apple trees to their 12 acres in 2012, before shifting entirely to apples in 2019, and McGuire finds satisfaction in this tight focus. Farming apples is hardly easy work, but growing a variety of vegetables is even more exhausting, both mentally and technically. After 15 years, there were few surprises left for him, and with the vegetable CSA market declining from its peak, he was ready to narrow his focus.

There are practical advantages to an apple-only farm: the harvest period is 12 weeks instead of 25, and the sloping farmland is less prone to erosion when planted with trees than it was with vegetable crops. A head of broccoli, McGuire points out, is pretty much the same whatever the variety and whenever you harvest it, but apples contain endless variation. There is an ongoing pleasure for him in the simple acts of eating, touching, looking at, and sharing an apple.

“We just started the CSA season,” he says, “and getting a few emails back puts a whole different perspective on what you were doing [before harvest season]. You go through this long period with

Chris and Juli McGuire (upper right, center) and their children grow a wide assortment of organic apples using regenerative agriculture techniques.

no tangible product and no feedback and support, so it’s kind of a relief and a nice feeling when you finally start to get it.”

Even if you are an apple lover, it’s worth asking why a purely apple-focused CSA is worth it. McGuire believes the best reasons for the consumer are simple: flavor and texture. These apples don’t have to make the journey most organic supermarket apples make from Washington State. An apple isn’t like a tomato or peach, which can be picked underripe and keep ripening in transit. There is a “constant dilemma” to when to pick an apple; if you pick earlier, it stores longer without softening, but it will never reach peak flavor. “There is only so much apple in the apple,” says McGuire. Under the CSA model, the McGuires can spread their harvest out over the course of the season and pick only when the time is right, delivering a lot or a few of any variety at its peak. They also have the advantage of knowing exactly when they’ll put apples in the buyer’s hands; there are no rainy farmers market days when you truck home a pile of apples to hold in the cooler for another week. He is philosophical about what we do with them after that.

“We can’t control how long people keep them on their counter,” he says, but “our life centers around the apples; everyone else’s doesn’t.”

I was tempted to start ordering my own life around apples after a visit to Blue Roof, where the McGuires’ land is orderly and calming, with a tall yellow farmhouse surrounded by flower gardens and a few outbuildings with blue metal roofs. Apple trees blanket the slopes in neat rows, small and laden with fruit in various stages of ripeness. McGuire showed me around the farm, along with one skeptical dog and a different kitten every time I glanced down. I counted three; McGuire laughed and said there were currently eleven.

I try not to over-romanticize farm life. But the landscape, the kittens, and my suspicion that an apple pie was in the offing at any given time, made it difficult. For now, I head over every Thursday to pick up a fresh batch of apples, and see which varieties are new that week. It’s not a complicated ritual—Chris and Juli have handled the complicated part for me—but it is a simple, perfect pleasure, a little different every time.

Michelle Wildgen is the author of four novels, most recently Wine People (Aug. 2023), and the cofounder of the Madison Writers’ Studio. Her work has appeared in Best American Food Writing, the New York Times Book Review and Modern Love column, O, the Oprah Magazine, and elsewhere.

APPLE IDEATIONS

My thirteen year old loves to layer thin slices on toast with chili flakes and sharp cheddar browned on top; I like the same treatment with a little fresh thyme and Gruyere.

I spent minutes trying to think of a cheese that would not go well with fresh apple and couldn’t come up with any.

An apple crisp is one of those throw-together ideas that probably could not fail even if you try, but please don’t. A mix of varieties in crisps and pies are always more interesting, and if you mix firm and softer types, you get a lovely melding of the two. I add almonds, pecans, walnuts, or oats to the topping to keep it interesting.

A sweet galette is never a bad idea, but neither is a savory one with a touch of whole wheat and aged cheese. And maybe a scattering of sage leaves crisped in butter over the top?

Faced with a bag of second-tier apples, I make apple sauce in the laziest manner possible: I core them, throw the chunks in a slow cooker with a spoonful of cinnamon, and cook for a few hours on low. I don’t even skin them, and they sometimes fall apart so well I don’t even have to run an immersion blender through them.

Pork and apples are a classic combination for a reason. I’m not a huge porkchop fan, but I’d do tenderloin—though dark-meat chicken seems like a good bet, too. I’d still add some thick-cut bacon, just to bridge the gaps, and a few more of those butter-crisped sage leaves, for good measure.

—Michele Wildgen

Delta Rae Photography

Sara Smith, the Midwest Tribal Climate Resilience liaison at the College of Menominee Nation.

A TWO-EYED PERSPECTIVE ON ADAPTING TO CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE MIDWEST

BY SARAH WHITE

Across the country, Tribes have become key voices in discussions and initiatives related to climate change and sustainability. Wisconsin is home to several leaders in this growing movement, including Sara Smith, who has emerged as not only a bridge between Tribal partners, but also as a crucial catalyst for bringing more attention, resources, and urgency to the challenge of building climate resilience across the Midwest.

As the Midwest Tribal Climate Resilience liaison at the College of Menominee Nation’s Sustainable Development Institute, Smith helps Tribal Nations partners access research and expertise at the Climate Adaptation Science Centers. Smith has become a go-to source on culturally informed climate science for a wide range of coalitions, organizations, university partners, and government entities.

Smith’s role is to incorporate Indigenous Knowledges into sustainability and climate adaptation efforts in the region, and her work is deeply informed by her Oneida heritage. “My family jokes that they had to keep an extra pair of shoes in the car when I was a kid because I was always running around barefoot,” she says of her upbringing in Appleton. Her Nana was the first to inspire her to explore the natural world, and Smith recalls bringing home “smelly” collections from the Door County beaches her family visited regularly.

“We were always camping, up in Door County or down at Devil’s Lake,” Smith says. “I have always had a profound love for the outdoors.”

That early interest in the natural sciences rekindled into a passion during her college years at the University of Wisconsin–Green Bay, where Smith pursued a dual degree in biology and First Nation Studies. Though Smith’s interdisciplinary focus puzzled her friends at the time, she sensed early on that the connection between these fields was significant.

As graduation neared, advisors encouraged Smith to apply for a fellowship at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF). The program’s faculty included Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, the botanist-turned-author whose bestselling Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants was published the same year Smith was accepted to her fellowship. The book, which to date

Smith’s graduate fieldwork involved studying fungi in the Menominee Forest. Top right: Smith’s Nana. Bottom right: Smith canoeing the waterways of Wisconsin.

has sold more than 2 million copies, is a unique compilation of personal memoir, Western plant science, and Indigenous Knowledge rooted in Kimmerer’s Potawatomi upbringing.

Like Smith, Kimmerer forged her own path as a scientist whose work is grounded in Indigenous Knowledge. Also like Smith, Kimmerer has a close connection to Wisconsin: she completed her advanced degrees at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the early 1980s, and it was during her time as the caretaker of the UW Arboretum that Kimmerer first realized she wanted to build a career that braided Western and Indigenous understandings of the living world, a perspective she terms “two-eyed seeing.”

“I had no idea who [Kimmerer] was when I applied, but I called her, we had a good chat, and she said, ‘you’re coming here,’” Smith says. She began her fellowship at SUNY-ESF that fall. Under Kimmerer’s guidance, Smith conducted research on the sustain-

ably managed forests of the Menominee Nation in Wisconsin, and her thesis incorporated traditional Menominee knowledge into her studies on ectomycorrhizal succession (the relationship between fungi and plant root systems) in White Pine stands on the Menominee Reservation.

“One of the protocols from the elders was that they have reverence for the underground community in the forest, so they don’t want to disturb them,” Smith says. “Out of respect, I only looked at things that were fruiting above the ground.

Smith quickly evolved from student to teacher during the project, and she led a team of interns into the Menominee forest to show them techniques for designating plots, finding mushrooms, collecting and identifying samples, and dehydrating them for her research. Their days began before dawn to maximize work before the day’s heat and often stretched into late evenings. Crawling

Team of nine interns who worked with Smith, along with CMN President Chris Caldwell, graduate student Raymond Gutteriez, and SUNY-ESF Professor Colin Beier. Interns included Haley Witt, Emily Badway, Ryan Scheel, Kristiana (Oowee) Ferguson, Pete Iacono, Eric Nacotee, Ella Keenan, Keith Kinepoway, and Rhonda Rae Tucker.

Above: The cohort from the Menominee Nation that attended the Climate Change, Indigenous Knowledge, and Planetary Health Summit in New Zealand. Left to right: Frances Turner, Jennifer Gauthier, Sara Smith, Toni Caldwell, President of the College of Menominee Nation Chris Caldwell, Otāēciah Besaw.

through pine duff, covered in tick and mosquito repellant, they photographed each find in situ before processing it.

After completing her ecology program, Smith quickly found a position as a natural resource technician with the Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians in northeastern Wisconsin. She began to focus more specifically on climate science, which eventually led to her transition to the climate liaison position at the College of the Menominee Nation in 2017. She serves all thirty-five federally recognized Tribal Nations in the Midwest region, including eleven federally recognized tribes in what is now known as Wisconsin.

Smith now helps to document and articulate how the impacts of climate change are directly affecting Tribes in Wisconsin and across the Midwest. For example, rising winter temperatures have substantially decreased frost, snow pack, and ice cover on the Great Lakes as compared to past decades. Various fish and mammal species are facing pressure as a result, and the changing water systems are also prone to larger and more frequent floods that strain roads, bridges, and other infrastructure not designed for these events. Yet Tribes are typically reservation-bound, meaning Indigenous communities can’t simply migrate elsewhere along with their plant and animal relatives.

One of Smith’s first assignments as climate liaison was to help develop Dibaginjigaadeg Anishinaabe Ezhitwaad: A Tribal Climate Adaptation Menu (TAM), a project under the aegis of the Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science (NIACS). The first of its kind and regional in scope, the TAM was published in 2019 with funds from the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, and a collaborative team of authors represented Tribal, academic, inter-Tribal, and governmental organizations across Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan.“Working on that project helped me learn what was going on already—which was not a lot when it came to incorporating Indigenous Knowledges into Western science, or into planning or tools,” says Smith. “I was grateful to be part of that team because, without that, I wouldn’t be as good of a liaison as I am right now.”

In 2019, the federal government doubled funding for regional climate adaptation science centers, and a new Midwest-specific center was established. By 2021, Smith’s work had expanded substantially, and in 2022, she received an award from the Minnesota Climate Adaptation Partnership in recognition of her growing contributions to climate adaptation planning across the Midwest. Smith’s influence in the field is especially evident in the latest edition of the National Climate Assessment, a comprehensive report produced by the U.S. Global Change Research Program that assesses the impacts of climate change on the United States. Smith co-authored the chapter covering the Midwest. “[Smith] worked very hard to make sure that in that Midwest chapter, Indigenous worldviews and language were incorporated throughout,” says Allison Scott, Deputy Midwest Tribal Liaison at the College of Menominee Nation. This included shifting language in the text of the report to refer to entities in nature as relatives or living beings, rather than describing them as “resources.”

Smith, with her colleague Scott, are also tasked with creating in-person forums for information exchange, and they regularly produce workshops for Tribal partners to help them better under-

stand, communicate, and meet the needs of Tribes. Bringing diverse stakeholders together to discuss contentious topics related to climate change can be challenging, but Smith has developed a reputation for creating effective and informative sessions.

“I admire her willingness to share her knowledge and expertise with others, so that they can also do a good job of recognizing, honoring and engaging with different ways of knowing, in the work we do in climate adaptation,” says Olivia LeDee, the deputy director of the Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center.

“[Smith] has a high level of emotional intelligence that’s a huge asset on work that depends on relationships and reciprocity,” says Scott.

As 2024 draws to a close, Smith and her colleagues are most focused on continuing to build Tribal capacity to implement and manage their own climate-adaptation projects, which has become more possible in recent years due to increased financial support from agencies including the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Environmental Protection Agency. “The additional funding increases Tribal staff’s ability to engage with what we offer and implement what we suggest,” says Scott.

One of Smith’s main areas of focus is the Shifting Season Summit. Held in October, the summit is a multi-day meeting that brings together Tribal communities, scientists, and other stakeholders to share knowledge and resources to benefit climate change adaptation efforts. Participants engage in hands-on workshops, field trips, and interactive sessions, and Smith’s agenda also includes interactive components to help participants connect personally to the outdoors. For example, they prepare and eat Indigenous foods and go on a field trip to gather corn and make art with the husks they bring back.

Smith is also beginning to expand her work internationally. With support from the Waverley Street Foundation, Smith is actively building relationships with Indigenous communities in New Zealand, Norway, and Finland. In March, Smith traveled to New Zealand for a knowledge exchange with Indigenous Maori people to talk about the impacts of climate change on sustainable forestry practices. To solidify the new partnership, Smith received a traditional Maori tattoo on her forearm.

“The work of adaptation is not just about the environment—it’s also about health, about land and sovereignty, it’s about our institutions,” Smith says. “Technology, economics, and human behaviors are all part of it. Thinking about this as a whole and how we go forward is really important.”

Sarah E. White is a freelance writer and personal historian. She helps people write about their lives and works from her home base in Madison.

Thanks to an extraordinary gift of animal and archeological specimens by prominent ornithologist Carl Richter in 1974, which included over 10,000 sets of bird eggs, the Richter Museum now holds one of the largest egg collections in North America.

NATURE’S HIDDEN GEMS

BY DANIEL MEINHARDT

The behind-the-scenes team of curators at the Richter Museum of Natural History in Green Bay serve as keepers of fundamental knowledge about the diversity of life on Earth in order to educate and inspire scientists, artists, and students.

Daniel Meinhardt

“In the end, we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught.”

Baba Dioum Senegalese forestry engineer

When most of us visualize a natural history museum, we imagine towering dinosaur skeletons and the skins of large mammals mounted in ferocious poses standing in massive exhibit halls. What we don’t picture, because most of the general public never see them, are the hundreds of thousands (even millions) of scientific specimens stored and studied behind closed doors. In fact, some natural history museums have no space at all to exhibit their collection, and function entirely as research facilities.

With the exception of a few display cases throughout Mary Ann Cofrin Hall, the Richter Museum of Natural History at the University of Wisconsin–Green Bay, founded 50 years ago, is one of these museums. As a result, the museum’s significant contributions to the university and the greater community were not always obvious.

In 2018, a portion of my faculty position as Associate Professor of Human Biology was reassigned so I could replace the museum’s retiring full-time curator. Since then, we have strengthened and forged new connections and collaborations to promote the important work at the Richter, and natural history museums in general. We’re working to expand its reach to a wider and more diverse audience, and increase its impact on research, education, and scientific advancement.

The Richter Museum is housed in a purpose-built facility in Mary Ann Cofrin Hall, in the heart of the picturesque UW–Green Bay campus, and is part of the Cofrin Center for Biodiversity. The center, a program of the College of Science, Engineering, and Technology, manages the museum and its plant counterpart, the Fewless Herbarium, as well as six natural areas in northeastern Wisconsin.

The Richter Museum was established in the 1970s thanks to a generous donation by the late Carl Richter, a native of Oconto, Wisconsin. One of the state’s most prominent ornithologists, Richter spent a great deal of his life assembling a remarkable personal collection of animal and archaeological specimens. Most of his specimens were collected in the western Great Lakes region, though he also obtained specimens from around the world, including Canada, Mexico, Central and South Americas, and Europe.

The museum’s website gives a great overview of Richter’s gift and the museum’s significance:

“Richter’s 1974 donation included over 10,000 sets of bird eggs, and the museum now houses over 11,000 sets, making it one of the largest egg collections in North America. The museum also contains tens of thousands of animal specimens, mostly in the form of study skins, skeletons, and alcohol-preserved specimens, and representing all major branches on the tree of life. With a focus on the Great Lakes fauna, all bird species that breed in the area are represented, as well as most of the fish, mammal, reptile, and amphibian species that call the great lakes area home. The collection of non-vertebrate animals is notable for containing significant numbers of local insect, mollusk, and spider species.”

Significant among Richter’s collection is a mounted male Passenger Pigeon, a species that famously was driven to extinction by commercial hunting for food in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The last living individual died in captivity in 1914, and the adult male specimen at UW–Green Bay is one of only about 1,200 birds

Above: The Passenger Pigeon is a species that famously was driven to extinction by commercial hunting for food in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The last living individual died in captivity in 1914, and the adult male specimen at UW–Green Bay is one of only about 1,200 birds (either mounted or stuffed as study skins) in existence worldwide. Left: A growing number of youth camps that incorporate the museum’s collections are conducted every year.

ALL ABOUT ACCESS

Fascinated by the workings of archives and museum collections, and knowing the goal was for these collections to be accessible, I took an internship at the Richter Museum as a graduate student in Library and Information Studies at UW–Green Bay. My job that academic school year was to standardize the existing digital catalog and upgrade it to a permanent collection management system. This included confirming the spellings of the names of the donors, as well as the items’ scientific names, and creating a controlled vocabulary list (such as “dead on road” instead of “roadkill”).

None of this was easy, but it pushed me to make the catalog simple and straightforward for all users—and set a course for my career goals and ambitions. I am currently working with the metadata remediation team at the Wisconsin Historical Society to prepare for their own migration to a new management system for their digitized collections. Creating access to archival materials and museum collections is my passion, and I appreciate the ability to apply my knowledge and experiences from the Richter Museum, as well as other opportunities, to make this possible for students, scientists, citizens, and more.

Beth Siltala, Archives Assistant, Wisconsin Historical Society

(either mounted or stuffed as study skins) in existence, worldwide. Even more noteworthy, Richter’s egg collection includes five specimens from the extinct bird, and we now know these specimens contain DNA from the embryos collected long before anyone knew what DNA is or why it’s so important to our understanding of all living things.

Since Richter’s donation, the museum’s collection has continued to grow, and now forms one of the most significant collections in the state. Most of the animals that end up in the collection today were killed in collisions with windows (birds) or cars (birds and other vertebrates), and the museum has federal and state salvage permits to possess these specimens.

A RESOURCE FOR SCIENTISTS AND ARTISTS, A TRAINING GROUND FOR STUDENTS

Natural history museums are the keepers of our most basic information about the diversity of life on earth, serving as unique and invaluable storehouses of information, as well as the source of valuable new knowledge. Studying preserved specimens and the crucial data that is archived with them informs much of what we know about the diet, behavior, and ecology of living animals. Biologists who work with understudied groups like insects, and even better-known species such as frogs, are often overwhelmed by the number of species that have yet to be formally described and named. Untold new species sit in museum collections for years, awaiting a scientist with the right expertise and time to do the tedious work needed to assign them a Latin name. For example, in 1996, while I was a graduate student at the University of Kansas Natural History Museum, I described an unnamed species of frog based on specimens that had already been in their collection for more than 20 years.

While we can only guess at the future scientific value of such collections, the Richter Museum is engaging students and the community at all levels. In the summer of 2023, members of the university’s Lifelong Learning Institute, which offers a plethora of discovery and engagement opportunities through noncredit classes and experiences to area residents, spent two days drawing from specimens in the museum under the tutelage of a professor emerita of art. Last summer, several groups of 4th through 8th graders toured the museum to learn about “magical creatures” as part of the Wizard Academy, a two-day camp led by Humanities Associate Professor Valerie Murrenus Pilmaier. A growing number of youth camps that incorporate the museum’s collections are conducted every year.

Being part of a university campus, the museum sees the most utilization from UW–Green Bay students and faculty. The courses most obviously suited to use the collection are taxonbased and related to biological classification, such as entomology (insects) ornithology (birds), mammalogy (mammals) and ichthyology (fish). Classes in wetland ecology and marine biology also rely on the museum. Viewing specimens up close helps students learn the subtle differences between species, as well as the confounding variation within species, and thus become much more skilled at identification in the field. Our graduates have put these skills to use at government agencies such as the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and non-govern -

SPECIES 101

"The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their proper name," Confucius wrote. Yet determining that proper name is not always quite so easy. Perhaps we know which animal to conjure when we say the name mountain lion , but how about when we say panther, cougar, or puma? All of these terms are used interchangeably to name the species that scientists formally describe as the Latinized, two-part name Puma concolor . A system like this is crucial to avoid the confusion that can arise from the many different names, in some cases from multiple languages, which are used to refer to a single species.

Latin was the language of scholars in the western world when Swedish biologist and physician Carl von Linne’, who often Latinized his own name as Carolus Linnaeus, developed the system for naming and classifying living species. As such, it makes historical sense that all formal names of species, and groups of species, are written as Latin or Greek, even if the words used are from a modern language. A very detailed set of rules, the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature governs how animal species are formally named so that no two animals are ever given the same binomial (two-part) name. A similar code governs non-animal species, so it is possible for a plant and an animal species to share the same scientific name. One rule common to all species is that the first part of the name shall be capitalized, but the second part is not. Both words are always written in italics to indicate the formal status of the name, thus what most people call cougar is known by biologists as Puma concolor

Usually, the Latin used to name a species describes something about it. Back in 1771 Linnaeus himself first

assigned a name to the cougar, calling it Felis concolor. Felis is Latin for “cat,” and concolor for “of uniform color.” Although more than one species can use the same genus (the first part of the name), as more cat species were discovered, the species was assigned a new genus, Puma, about 100 years after Linnaeus first described it. Modern biologists insist on grouping species by their genealogical relationships, many of which are still being deciphered. So it's not unusual for species to be reassigned to a different group, including genus, as new information becomes available. In either case, the specific epithet (the second name) usually remains the same.

New species are often discovered even within museum collections. Many of these are very similar to other species and may have been misidentified in the collection. If the species were new to scientists, they likely would have been described long ago, so the process of finding new species among existing collections has become more cumbersome over time. The species of frog my colleague and I described in 1996 belonged to a group of about 90 closely related species, so we had to study the published descriptions of all those species, and examine specimens of dozens of them, to determine if what we had was indeed an unnamed species. And with approximately 5,000 species, frogs are a relatively small group. For instance, more than 400,000 species of beetle have been formally described to date, and there are likely more unnamed species than there are biologists qualified to describe them.

Text and illustration by Daniel Meinhardt

mental organizations like the Nature Conservancy. Those students often to collaborate with UW–Green Bay faculty, and in many cases continue to contribute specimens to the museum to document that work. In the last six years, the Richter Museum has hosted interns conducting projects in public education, collection curation, and database management, who then moved on to work in positions in outreach at the Green Bay Botanical Garden, and as archive Assistant at the Wisconsin Historical Society, and fish Biologist for the U.S. Forest Service.

Biology and environmental science students at UW–Green Bay are not the only students to benefit from the museum’s presence. For decades, art students in classes such as Two-dimensional Design, Three-dimensional Design, Introductory Drawing, and Intermediate Drawing have made studies of specimens housed in the Richter. The museum is even featured on the drawing program’s main webpage. And because part of the egg collection is available as photographs in our online database, students and instructors at other institutions regularly make use of this rich resource.

In 2021, students approached me about starting a Scientific Illustration Student Organization, and once established they hit the ground running. From the start, the meetings were very

well attended, and the group began participating in a variety of campus events such as the STEM Family Day and Biodiversity Day. When we approached the UW–Green Bay Teaching Press about publishing a coloring book based on students’ illustrations, the project grew into Wandering Toft Point, a nature journal featuring completed illustrations and poems inspired by one of the natural areas managed by the Cofrin Center for Biodiversity. Understandably, many of the illustrators who contributed to the book relied on Richter specimens to hone their skills and accurately represent the species depicted. As the organization’s advisor, I use the collection extensively to help students learn illustration techniques and understand why scientific illustration is still an important means of studying biodiversity.

As part of our efforts to promote the museum by creating more diverse opportunities for community engagement, we launched one of our most ambitious and successful projects in 2018, when the university’s Lawton Gallery of Art hosted a group show called Museum of Natural Inspiration: Artists Explore the Richter Collection. The idea came to me when I was asked to join the curatorial advisory committee for the Lawton Gallery at roughly the same time I was appointed Richter curator. Working with now-former

Photograph of the 2018 exhibit, Museum of Natural Inspiration: Artists Explore the Richter Collection, a unique and ambitious collaboration between the Richter Museum of Natural History and the Lawton Gallery, both located on the campus of University of Wisconsin–Green Bay.

The Museum of Natural Inspiration exhibit featured 27 artists who produced a total of 47 pieces. In many cases, the art work was exhibited alongside the specimen or specimens that inspired it.

Left Top: Kendra Bulgrin, All in a Dream, oil on canvas 36.5”x40.5”. Left Bottom: Michelle Zjala Winter, Egg and Skull, Trapper Creek Agate and Sterling Silver, 1.5”x1”x5”. Above: The Richter collection is used extensively to help students learn illustration techniques and understand why scientific illustration is still an important means of studying biodiversity. One such project grew into Wandering Toft Point, a nature journal published by UW–Green Bay Teaching Press featuring completed illustrations and poems inspired by one of the natural areas managed by the Cofrin Center for Biodiversity. Many of the illustrators who contributed to the book relied on Richter specimens to hone their skills and represent accurately the species depicted.

Above: Sarah Detweiler

Left: Cidne Hart, Oological Data, Cyanotype, 30”x24”

Lawton Curator Emma Hitzman, we conducted an open call for interested artists. Over the course of the next year, I hosted approximately 50 artists from as far away as Los Angeles on tours of the Richter, and tasked them with using the collection as inspiration for new work. Ultimately, 27 artists produced a total of 47 pieces that were included in the show, and in many cases the work was exhibited alongside the specimen or specimens that inspired it. Besides being immensely popular, the show forged connections to the museum throughout northeast Wisconsin and beyond. One of the participating artists has since opened a gallery in De Pere, and in 2022 hosted an exhibit featuring Richter specimens alongside nature-inspired art.

We are extremely fortunate that UW–Green Bay has made our biological collections a serious priority, as this is not always the case at other universities. Natural history collections can be viewed, even by scientists, as antiquated institutions with little to contribute to modern biology. As a result, such collections are often neglected, especially when resources are in short supply. These cases are tragic, because biological collections are not just irreplaceable, they are at the core of our understanding of biodiversity. Students at UW–Green Bay are enriched by the collection in so many different ways, from a variety of different classes in biology and art to regular research opportunities for undergraduates and graduate students funded through the Cofrin Center for Biodiversity. I relish every opportunity to share the collection with the university community and visitors alike, making the case for why we need natural history museums. Anyone with even a modest interest in nature will come away impressed by the depth and breadth of our collection and its distinctive ability to teach, engage, and inspire.

To learn more about the museum or visit the collection for research or educational purposes, contact Dr. Daniel Meinhardt, Richter Museum Curator, at (920) 465-2398 or meinhada@uwgb.edu.

Dr. Daniel Meinhardt teaches courses in human anatomy and physiology, comparative vertebrate anatomy, and evolutionary biology at the University of Wisconsin–Green Bay. Trained as an evolutionary anatomist, Dr. Meinhardt’s early research focused on miniaturization in frogs and some philosophical questions in evolutionary biology. His recent work blurs the line between art and science. In 2015 the Pride Center honored Dr. Meinhardt with the faculty Lavender Leadership Award.

Whether it’s a beloved print or family heirloom, give your piece an artful presentation that will stand the test of time.

OPEN Tues – Sat, 10am – 5pm

Schedule an appointment or drop by

Painting by Natalie Jo Wright, Instagram @nataliejowrightart

NIRMAL RAJA ASKING QUESTIONS OF A THREAD

BY JODY CLOWES

As an artist, a curator, a mentor, and a seeker, Nirmal Raja has made an indelible imprint on Milwaukee, where she has lived and worked for the last 24 years. Her humility, generosity, and the intellectual depth of her practice have enriched and inspired her many friends and collaborators across the arts community. Raja was born in India and lived in South Korea and Hong Kong before immigrating to Wisconsin, and her work consistently connects the intimate and personal with a consciously global concern. Her experimental, interdisciplinary practice often delves into difficult emotional realms. Investigating personal, social, and political conflicts, Raja seamlessly melds complex content with intriguing surfaces and materials to create beautiful and engaging works.

Nirmal Raja’s solo exhibition, Asking Questions of a Thread , was guest curated for the James Watrous Gallery by Ann Sinfield. We are honored to work with Ann, whose probing and insightful approach to Raja’s work has resulted in a powerful gallery presentation. Asking Questions of a Thread was on view through October 20, 2024.

Nirmal Raja, Breath, 2021, acrylic ink, India ink, gouache on Hanji (handmade paper)

Nirmal Raja

Jody Clowes: The title of your exhibition, Asking Questions of a Thread, is beautifully openended. How would you describe what that phrase means to you?

Nirmal Raja: This is related to the title of the video and poem in the exhibition, “Can I ask a question of a thread?” It seems to fit and connect with everything in this show. Questioning is inherent to my practice because it’s very inquiry based. It’s always about learning more, either through the practice itself or trying to understand what’s going on around me, so it needed to be evocative of that kind of a searching process. The word thread itself could refer to inquiry, metaphorically, because we think of trains of thought as threads of investigation or threads of thinking. That was the other part that seemed to fit in.

J: That makes sense. Curiosity and questioning are so central to everything that you’re doing. I just love the way that thread, as you say, is an elusive term that can lead in lots of different directions.

While you work across many media, fabric, thread, and clothing have been really central to your practice. In many cases, these textiles are freighted with cultural or personal meaning. I’d love to hear more about how the stories embedded in these kinds of textiles inspire you, or lead you to work with them in a particular way.

N: Well, since I grew up in a culture that has such a rich textile history, fabric is almost the first language that I learned. I grew up learning embroidery from my grandmother, crochet from my grandmother, and just absorbing this love for fabric. My mom used to design clothing for me and did a lot of negotiating with the local tailor to have certain clothes made. So, there’s this real passion for fabrics and the beauty that they hold. But as I get older, I think it’s also just that fabric is so intimate, so connected to the body. I almost think of it as a second skin. Used fabric, especially, is important for me because there is this belief in India that when somebody has passed, only the most important, expensive clothes that you’d really want to save would be given to family members. The rest of the clothes would be burned because a lot of cultures in Asia believe that the essence of the person gets absorbed by the clothing they wear. Used fabrics kind of take on their owner’s personality, or their DNA becomes embedded within the fibers. I can’t tell you how this belief emerged; it could be related to a concern about contamination...that’s probably how it originated. But this connection between fabric and body is very important for me because I think when I use these fabrics in my work it’s also about harnessing that essence. Whenever I work with fabric, it becomes more about the meanings that it holds rather than the techniques I employ. I’m really translating that fabric into a different way of experiencing it.

J: So, for example, for your piece Entangled, you were working with saris collected from women you had met, but didn’t necessarily have a personal relationship with. In contrast, you’ve made a series of pieces with the clothing your father left behind after his death. How is it different to work with fabrics from acquaintances versus someone close to you?

N: I think that with Entangled, using the saris was more about the aesthetics of all that color and the importance of sourcing the saris from the community. When I created this over a decade ago, the work was more about the dichotomy of the beauty and richness of the culture that I come from, and my complicated relationship with that culture. Once you leave the place you grew up in and are negotiating the two cultural geographies, you’re trying to choose what’s best from each culture or trying to examine the culture that you come from with a removed perspective and with a little more critical eye. I think migration allows you to look back at your own culture to see what other people see in your culture, too. There’s so much complexity as a South Asian woman, or any immigrant woman living in the U.S., that you’re contending with. I wanted to capture that complexity and the ‘tangle’ as a metaphor was important because I feel like I’m always trying to untangle puzzles and problems in my life.

And yeah, I think it’s very different working with my dad’s clothes. It was very much about tapping into a feeling that he is still with me, as his DNA is in me. His memories and his influences are very much part of my personality; I’m very much like my dad, actually. He’s with me in that way, but also the sudden disappearance of his physical self was very shocking. I’ve lost my grandparents, but I’ve never really lost somebody that close to me before. It’s almost like a mirror of myself passing away. I wanted to try and express that sense of his ‘being there’ and ‘not being there’ at the same time, rather than aesthetics, color, or anything like that. It was about taking that fabric, making an impression of it, and letting the fabric itself burn away, which is what happens with the burnout technique [dipping the fabric in porcelain slip and firing it in a kiln]. In the finished piece, there’s this hollowness. If you were to cut the sculpture open, you would see the little pores or spaces where the fabric was burnt away in the kiln. I feel like that helped me understand the conflicting feelings I have; to reconcile this feeling that he’s here with me, but he’s also gone and I can never really touch him.

J: I think it’s a beautiful metaphor. I really love the way the piece holds that impression of the fabric, but the substance is no longer there.

N: And also, cremation is how I got the idea because in my culture, we cremate the dead. Usually, the funerary rituals are only done by the son; the women do not go to the cremation grounds or anything. But I insisted on going with my brother. The experience is not as clinical as what people do here. You know, when you go to a funeral here, it’s an embalmed body in a casket or a closed casket, right? Everything that I experienced during my dad’s funeral was very visceral, very direct. It’s impossible to ignore the ugliness of it, but also there’s so much beauty in the ritual itself. I was a little shocked that I was actually noticing beauty when I was so sad.

J: Thank you for sharing that. Being so directly confronted with the reality of our bodies’ mortality must give you a real sense of closure, even if it’s incredibly difficult.

I want to go back to Entangled, in which these fat tubes sewn from saris become an unwieldy, snaky mass, and also reference your Contained series, in which saris are embedded in plaster and yet spill out, breaking the silhouette of the mold. There’s an element of chaos in these works; a sense of repressed energies that could shift unexpectedly. If these works made with saris are a reflection on the experience of immigrant women in that context, how would you describe that sense of coiled or latent energy?

N: I think that throughout my life I’ve resisted being put in boxes because I grew up in a very conservative, traditional home and there were certain expectations of young girls and women. I found it very suffocating and restrictive. When I came to this country, I felt like I was being put in a box again, with certain expectations of what my art should look like—that exoticism or objectifying gaze. Even with my interdisciplinary practice, I felt the art world was expecting me to make similar work with

the same medium, like, “Why are you switching gears now?” Or galleries expect you to do things a certain way. I’m always trying not to fit into anybody else’s idea of who I should be. In the Contained series, breaking out of those cubes comes from that urge to make sure I’m resisting that kind of definition.

J: Two of the pieces in this exhibition—Weight of our Past and What is Recorded, What is Remembered—document performances you’ve done. How do you feel about that translation when a performance piece is represented in a gallery space through photographs or video? Has that translation ever changed your understanding of the work, or revealed something that might not have been foregrounded in the performance itself?

N: Just like I try to find a material language that accurately expresses what I want to say, performance becomes one of those tools. I’m very aware that my performance is for the camera. I don’t think of it as documentation as such; I think of it as an inherent artwork where I’m using the lens to get to that expression. I do not perform live. I usually work with someone like Lois Bielefeld or Maeve Jackson to either collaborate with me or document the work with video or photography.

With these two bodies of work, there is one important difference. What is Recorded, What is Remembered is very much a collaboration that Lois and I came to together. We were walking down the Riverwalk in Milwaukee [where there is an engraved timeline of Wisconsin and American history] and thinking about history right after Trump was elected. The work emerged out of that collaborative brainstorming with Lois. But for the Weight of our Past, I commissioned her to make photographs [of Raja engaging physically with her sculpture Entangled] with the primary purpose of expressing how the meaning of that piece had changed for me. A decade after making it, it became very much about carrying a cultural burden; how I wanted to almost discard it, and yet it’s just part of me that I’m dragging along wherever I go. Since I had worked with Lois earlier, I felt comfortable and I am grateful that she agreed to document these performative actions for me.

J: I didn’t realize that Entangled existed for so long before you felt you needed to perform something with it. Has that ever happened with other pieces, where an object calls out to be shared through performance, rather than the idea of the performance coming first?

N: I have a daily studio practice, and I was making a series of bricks, experimenting with pouring fabric and plaster together into brick-shaped molds just to see how those two materials reacted together. But then I started making more and more, one every day, and eventually they found their place into a sculpture/ video performance called The Wall Within. It was made right after the Black Lives Matter movement emerged, and I wanted to make a work that spoke about witnessing social change, and all the different protests that were happening, and the sense that the power structure was changing at that time. Maeve Jackson came to my studio and filmed and edited the work with my direction.

Nirmal Raja, Contained, 2018. Fabric and collographs on plaster casts.

Nirmal Raja

J: I’m so impressed by the discipline and focus of your studio practice. You put your art education on hold until your kids were grown. But since then, you’ve been fiercely dedicated to your studio practice and curatorial work. You must have had creative outlets before you could commit to making art full time. When you were young, did you have a sense that art would become so central to your life?

N: I always wanted to be an artist, even as a child. But I grew up in a conservative home and going away for college was not an option. I did my undergraduate degree in English literature so I could stay with my parents and go to college from home. But when I came to this country, I did my first year at MIAD [Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design] in 1991 and it was amazing. I totally wanted to continue, but then life changed. We had to move for my husband’s training, and we had two children. The one way I could keep in touch with art was actually taking classes. So I took classes at Moore College of Art, and Maryland Institute College of Art. I would always take one credit course at a time, and was able to fit in childrearing and my husband’s schedule. That’s how I kept in touch. By the time we moved back to Milwaukee and I finished my MFA, 16 years had passed. But I sustained my interest in art through taking classes.

J: When you were a child in India, what was your image of an artist’s life? Did you have models around you that inspired you?

N: I was very good at drawing and painting. Being an artist meant being a painter. Little did I know that art was always around me, whether it was making a flower garland for morning worship, or sewing and mending garments. Those kinds of things were happening around me and were part of my life. At that time, of course, the formal idea of what an artist “is” was what I wanted to be. But I’ve moved away from the traditional way of making art, especially oil painting. I used to make a lot of oil paintings and I don’t do that anymore, specifically because of its very Eurocentric and colonial history. It just didn’t seem authentic to my own story.

J: I think it’s fascinating how you have circled back to these traditional forms, but are using them in such a personal, contemporary way.

You’ve been closely engaged with Milwaukee’s art community for many years, collaborating with other artists, curating exhibitions that showcase local artists and bring the work of international artists to the city, and serving as a mentor through the Milwaukee Artists Resource Network. Can you describe what it’s like to be part of a community like Milwaukee and how the support of other artists has been important to your development?

N: I think as an interdisciplinary artist, it’s almost impossible not to seek help because you’re this jack-of-all- trades, master of none. I’m always in a space where I’m wanting to learn more about a certain technique or material because it’s the perfect language for what I want to say. I’m always reaching out to people to show me how to do things, or taking a class, or doing a video tutorial, or collaborating. There are many, many different ways of connecting with people to find out how to make what I want to make. That’s just part of the production of my artwork. But

I think it also speaks to a strong belief that we are all interconnected and you cannot make art in isolation. Influences come from all around you and the people that live around you shape you in some way. I do not believe in art in isolation. I feel like we are always changing and being influenced by the surroundings. Milwaukee has been hugely transformative for my career because, although we have so little funding from the state, our wealth is in the people. I’ve found generous people —willing to help support or assist by sharing their knowledge and expertise. So grateful for that! When I mentor emerging artists and curate exhibitions—to give voice to people who don’t get seen or have the space to express themselves, it is my way of giving back. I think that supportive, reciprocal spirit really exists in Milwaukee. It was hard to say goodbye to that. Milwaukee feels like it is just the right size for that kind of thing to happen.

J: In a larger city like Chicago, there are obviously networks of support, but it’s impossible to know about everything that’s going on. Milwaukee, for better or worse, is a place where you really can get a sense of the city’s art scene as a whole pretty quickly.

N: As far as curating is concerned, during my travels back and forth to India and travels with my husband, we always make it a point to visit the museums and galleries wherever we go. I had this urge to bring some of what we saw and share it with Milwaukee. So curating art is important to me because I’m forming networks and connections in the process. For example, work made by artists in India was shown at the Union Gallery [at UW–Milwaukee]. Those artists eventually hosted some artists from Milwaukee for an exhibition in India. That kind of cross-pollination of artwork and ideas is something that’s very inspiring to me because when you see art from a different place, you begin to understand the people that made that artwork. I like to facilitate that whenever I can. That’s how my curating started. The other goal was to widen the visual culture because it’s very easy in a city like Milwaukee to keep seeing work by the same artists. I thought that to expand what you can see would be really exciting.

J: I think your curatorial projects have been a real gift to the community. As a curator and as an artist, I know you are very sensitive to how the arrangement of an exhibition affects the visitors’ experience, and you’ve typically been closely involved in the presentation of your own work. What has it been like to have Ann Sinfield, Curatorial Lead at the Harley-Davidson Museum, curating your solo exhibition for the Watrous Gallery? Have you been surprised by any of the selections she has made or the questions she’s asked?

N: I was very excited about this exhibition because you get so involved in your practice that you don’t often get an insight into what other people see in it. I almost want to be there as a fly on the wall to see what other people say about the work or how they interact with the work—which way they walk or what catches their eye first. I want that removed perspective, especially because working with so many different media gets me lost in a maze sometimes. To have someone decode and connect the

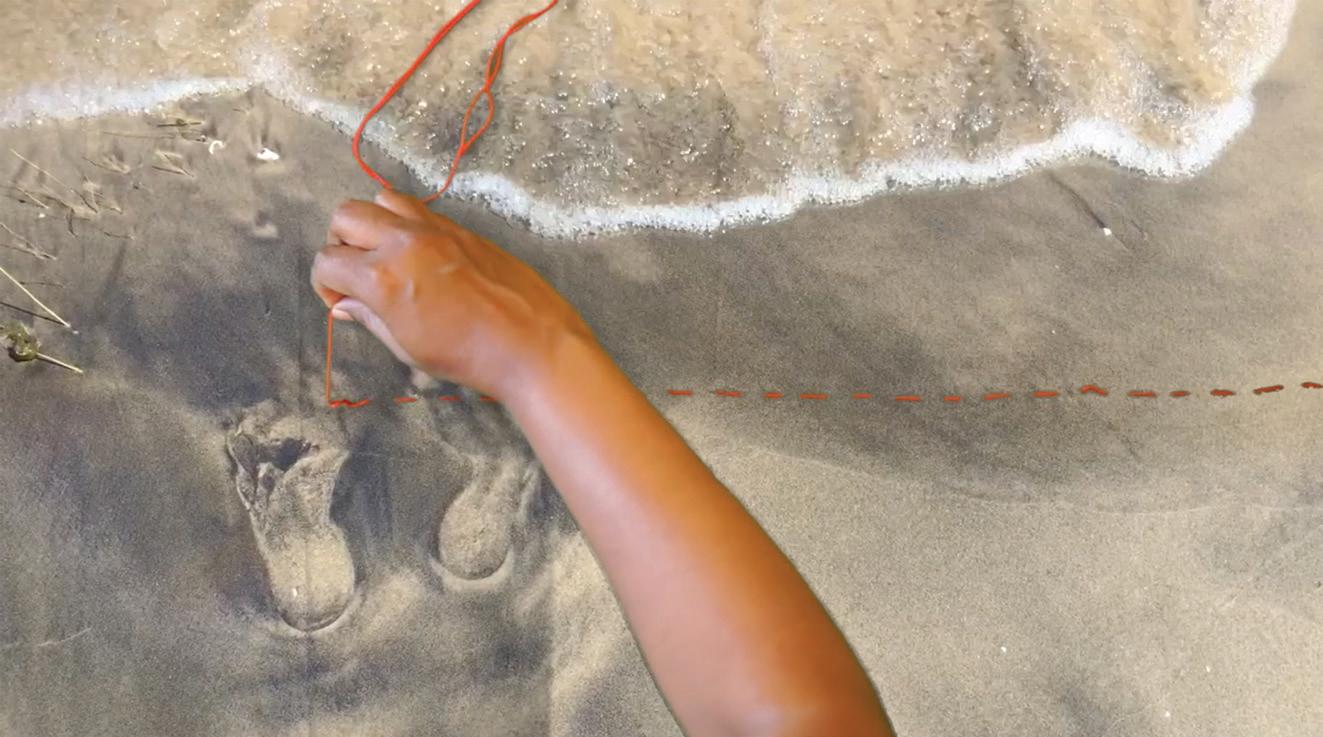

Top: Nirmal Raja, Thread in Open Waters, 2018, Video still. Bottom: Nirmal Raja, What is recorded | What is remembered, 2018, Lois Bielefeld and Nirmal Raja.

Lois Bielefeld

Nirmal

Raja

Lois Bielefeld

Nirmal Raja, Entangled / The Weight of Our Past, 2022.

dots is illuminating for me, so I’m eager to see what happens in the space itself. I trust Ann and I’m curious to walk through the exhibition as if it was not my own work.

J: I’m also curious to see your response, because it is an act of trust to hand it over in that way. And speaking of an act of trust, you’re still creating some of the pieces that will be in the exhibition—the Accretions series of fabric pieces. I think it’s wonderful that Ann was open to including things that are still in process in the exhibition. Tell me about how those pieces have evolved.

N: Ann did see the first layer of the Accretions series, so she could have a sense about what they would look like. I think the move [to Massachusetts] was a very big part of that work because I began to discover little things I have held onto over the years that eventually found their way into those pieces. Those works are very much about attachment to material things for sentimental reasons or because things are gifted to you. I ask myself “why I hold on to this particular bead that was part of a garment I wore as a 12-year-old?” for example —things that just linger with you. Initially, the titles of the pieces were Fly Papers because they are passive surfaces—where things just accidentally end up on.. I discovered things in nooks and crannies when the furniture got moved. All kinds of things have been going onto these surfaces. The challenge is trying to keep it aesthetically pleasing. I’m trying to pause the work at a place where I think it’s okay to be viewed in a professional setting, but I’m imagining these pieces as durational works that would only end when I pass. They would just gradually get more unwieldy, heavy, and layered.

J: I love the idea that we’re seeing these works in the gallery at a certain point in time, but they’ll never be the same again. Maybe this will become a documentation project for you along the way.

How did Ann approach you to curate the exhibition?

N: Ann has been following my work for almost a decade now. She usually comes to my exhibitions, and she has written about my work for her blog. I did an exhibition during the pandemic called Feeble Barriers, including embroidered masks with quotes from health care workers, and she wrote a beautiful essay about that exhibition. We eventually started conversing, and she came for studio visits and wanted to submit something to the Watrous open call.

J: It’s exciting to work with the two of you. We have worked with guest curators a few times in the past, but your show is the first guest-curated exhibition to come out of our recent call for artists process.

I wanted to end with two questions from our intern Suchita Hothur, who is a very thoughtful young woman. She’s from Bangalore, and she suggested two questions connected to your cross-cultural experience that would never have occurred to me. The first one is about the cast iron braids you made during your Arts/Industry residency at Kohler Company. In India, hair and braiding hold an important cultural significance. How are cultural expectations and values reinforced through unspoken rules, as here, with hair? Can such practices simultaneously hold beauty and pain?

N: Yes, it’s very connected to the work that I’m making. I’m actually thinking about the braid being a form of patriarchal control. When I was growing up, I was not allowed to cut my hair because the ideal form of feminine beauty is to wear long, oiled and braided hair. It wasn’t until I came to this country that I cut my hair almost as an act of rebellion. At the same time, I was noticing that the lives of my aunt, my mom, and my grandmothers in the traditional setting are viewed as weak or dismissed to the domestic realm. But women in the domestic realm in cultures like these also wield a lot of power. There is a certain kind of strength, or forbearance, that I witness in my own family and a lot of Indian American women around me. I wanted to kind of reverse that patriarchal understanding of the braid by using a material such as iron, which is an extremely heavy material— considered strong, but actually it’s not, it’s brittle. It’s about how strength and grace can be combined as I witness them in women in my family- who did follow all of these traditional norms and lived their whole lives in this patriarchal framework but at the same time were strong and had gravitas. So that’s what I was trying to explore.

J: Suchita also suggested that the patterns in some of your work reminded her of rangolis. Is that something that seems true to you?

N: Yes, I have made previous work using rangoli powder. Every morning [in most households in India] women wash the threshold and then make beautiful patterns with powder—

Nirmal Raja, Can I ask a question of a thread?, 2020, Video still; filmed with an ophthalmology camera.

either rice flour or a chalk grit. I love this act because it’s about creating everyday beauty, but also the work gets worn out, blown away, or walked over in just a few hours—not even a few, just an hour or so. I’m very drawn to the transience, the disappearance of that labor, and the momentary beauty that you’re walking over. Also, I love this determination to make your surroundings beautiful and to honor that doorway, which kind of defines the insider and the outsider. When you create a path—a design in front of the house—the meaning is to welcome your guest. You are giving whoever is passing through that threshold something beautiful to look at and welcoming them into your home. So, I did make two works, five feet by five feet on black canvas placed a few inches of the floor horizontally, where I used the chalk grit that’s used in rangoli, but not using traditional patterns, but DNA patterns. One work depicts mitochondrial DNA, the particular kind of DNA that gets transferred from mother to girl child. I wanted to make that because rangoli is practiced only by women and I wanted to speak about lineage that’s passed on through ritual and through these practices. The other is just a DNA strand. It’s loose powder and at the end of the exhibition it just gets shaken out.

J: That’s beautiful. It’s kind of a perfect metaphor for an exhibition as well. You’re creating this beauty, welcoming people in to experience it and it’s very personal, almost like inviting somebody into your home. But temporary—exhibitions are so ephemeral. Thank you so much. I greatly appreciate your candor and your thoughtfulness.

Note to the reader: Images of almost all of Rajal’s earlier work can be viewed at nirmalraja.net, including those pieces made with chalk grit, which are titled The Never Ending Line.

Jody Clowes is the director of the Academy’s James Watrous Gallery and arts editor for Wisconsin People & Ideas magazine. She has years of experience developing and curating exhibits, designing public programs, and writing about art, including senior positions at Milwaukee Art Museum, Detroit’s Pewabic Pottery, and the UW–Madison’s Design Gallery.

On view at the James Watrous Gallery in Overture Center for the Arts 201 State St., Madison

NOVEMBER 1, 2024–JANUARY 12, 2025

FEBRUARY 1–APRIL 13, 2025 WHEREVER HOME IS Guest curated by Fanana Banana (Amal Azzam & Nayfa Naji)

MAY 2–JULY 13, 2025

Visit wisconsinacademy.org/gallery to learn more!

Thanks to Wisconsin Academy donors, members, and the following sponsors:

MENDING RUTH

BY BOB WAKE

Saukfield in late August gives up the ghost of summer with abrupt abandon. End of day temperatures drop with sudden coolness like an American Spirit extinguished in a leaf-clogged swimming pool. Not much of a swimming pool. An inflatable vinyl ring that holds the twins and their beach toys, but not without severe overcrowding. The fact that it takes forever to fill the pool from a garden hose suggests to my children watery depths that never materialize. “When’s Mom?” says Lucy, sitting in pool water up to the belly button dent in her swimsuit.

Lucy is shivering.

“When’s Mom?” says Jon.

Ruth’s return from Mudstone is delayed.

“It’s tricky,” I say.