One Fateful Bite • Flight of Resilience • Chance Encounters Let it Shine: Storyteller

Everett Marshburn

A fresh new WPR is coming Learn more at wpr.org/new WPR was created for those who seek out... new voices new chords new inspiration

Left: WPR’s “Uprooted: Cuban in Wisconsin” podcast, Center: members of the Wisconsin Youth Symphony Orchestra performing live on “The Midday,” Right: Wisconsin high school football players Hannah Peters and Ava Matz on WPR news.

WISCONSIN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, ARTS & LETTERS

WISCONSIN ACADEMY STAFF

Madison Buening • External Relations Coordinator

Jody Clowes • Director, James Watrous Gallery

Elisabeth Condon • Director of Science and Climate Programs

Lulu Fregoso • Climate & Energy Intern

Jennifer Graham • Exhibitions and Outreach Coordinator

Jessica James • Climate & Energy Program Manager

Erika Monroe-Kane • Executive Director

Matthew Rezin • Operations Manager

Zack Robins • Director of Development

Julie Steinert • Administrative Assistant

Yong Cheng (Yong Cha) Yang • Visitor Services Associate, James Watrous Gallery

ACADEMY BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Roberta Filicky-Peneski • President

Frank D. Byrne • President-Elect

Thomas W. Still • Secretary

Richard Donkle • Treasurer

Amy Horst • Vice President of Arts

Kimberly Blaeser • Vice President of Letters

Robert D. Mathieu • Vice President of Sciences

Tom Luljak • Immediate Past President

Mark Bradley • Foundation President

Steve Ackerman, Madison

Ruben Anthony, Madison

Lillian Brown, Ripon

Jay Handy, Madison

BJ Hollars, Eau Claire

Nyra Jordan, Madison

Michael Morgan, Milwaukee

Kevin Reilly, Verona

Brent Smith, La Crosse

Jeff Rusinow, Grafton

Julia Taylor, Milwaukee

ACADEMY FOUNDATION

Ira Baldwin (1895–1999) • Foundation Founder

Mark Bradley • Foundation President

Jack Kussmaul • Foundation Vice-President

Arjun Sanga • Foundation Secretary

Richard Donkle • Foundation Treasurer

Roberta Filicky-Peneski • Academy President

Frank Byrne • Academy President-Elect

Tom Luljak • Academy Immediate-Past President

Kristen Carreira

Betty Custer

Andrew Richards

Steve Wildeck

Editor’s Note

Last year, after almost 30 years of living in Wisconsin, I realized it was time to come home. I now reside in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, with the Blue Ridge Mountains floating along the skyline like a backdrop to a movie. As interim editor of Wisconsin People & Ideas for the last few months, I’ve frequently been reminded of why I was drawn to Wisconsin all those years ago. Travel anywhere in the state—urban or rural, north or south, Driftless or Great Lakes regions—and you experience such a diversity and richness in geography and culture. It sounds a bit corny to say it was, in fact, the “people” and the “ideas” that sustained me, not only in my career but in making a life there for myself and my family. Almost as compelling were “lakes” and “cheese.” I do miss them all, which is why it is such a delight to share some highlights of what we’ve put together for you in this month’s issue.

Our cover profile chronicles the rich journalistic life of Milwaukee TV producer Everett Marshburn. He was recently inducted into the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences 2024 Gold Circle, the first person in the state to receive this distinguished service honor. My dear friend and colleague John Motoviloff writes this issue’s “Wisconsin Table,” part memoir, part treatise on state efforts to bring game hunting to a wider audience. Similar themes of inclusion are abundant in Dexter Patterson’s essay on the joy of birding. The author also urges us to get out and enjoy spring bird migration hotspots around the state. Sarah White’s fascinating piece on artists who create their own pottery pigments and glazes will leave you with an unexpected appreciation for this unique aspect of ceramics.

The Academy is proud to feature another impressive group of 2023 fiction and poetry contest winners in this month’s issue. Susanna Daniel’s “Goddess of Illicit Choices” won 2nd place in fiction, while Emily Bowles, Adam Fell, Steven Espada Dawson, Marnie Bullock Dresser, and Kelly R. Samuels received honorable mentions in poetry.

Because this is a double issue, the content I mention here is just a sampling of a robust and satisfying collection of essays, profiles, book reviews, and more. Also featured is our usual primer on the upcoming artists exhibiting at the James Watrous Gallery in Madison’s Overture Center.

In addition to what I learned from the people and ideas featured in this magazine, I gained some insight into myself. That instinctive tug to return home recently was the same one that brought me to Wisconsin. If home is where the heart is, then Virginia holds my heart. Wisconsin, however, will always hold my soul. I hope you will enjoy reading this as much as I have enjoyed being reminded of the many things that are so very special about Wisconsin.

Brennan Nardi, Interim Editor

Brennan Nardi, Interim Editor

WINTER / SPRING 2024 1

On the cover: Milwaukee PBS producer Everett Marshburn Credit: TJ Lambert/Stages Photography

2 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS D e tx e r P a t t e r son 50 38 01 Editor’s Note 04 From the Director Wisconsin Table 08 One Fateful Bite John Motoviloff Profile 16 Let it Shine: After five decades in public television, Everett Marshburn still has stories to bring into the light James Causey Essay 25 Crafting Brilliance: Ceramic artists perform alchemy with glazes and pigments Sarah E. White Essay 32 Sustainability Inc.: Business innovation merges better worlds with bottom lines Kristine Hansen Essay 38 Flight of Resilience: A personal journey in birding plus spring migration viewing spots Dexter Patterson CONTENTS

JayneKing

Wisconsin People & Ideas is the quarterly magazine of the nonprofit Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters. Wisconsin Academy members receive an annual subscription to this magazine.

Since 1954, the Wisconsin Academy has published a magazine for people who are curious about the world and proud of Wisconsin ideas. Wisconsin People & Ideas features thoughtful stories about the state’s people and culture, original creative writing and artwork, and informative articles about Wisconsin innovation. The magazine also hosts annual fiction and poetry contests that provide opportunity and encouragement for Wisconsin writers.

WINTER / SPRING 2024 3 Ideas that move the world forward

the Wisconsin Academy and help us create a brighter future inspired by Wisconsin people and ideas. Visit wisconsinacademy.org/brighter to learn how.

Academy Offices

University Avenue • Madison,

53726

608-733-6633 • wisconsinacademy.org VOLUME 70 · NUMBER 1

• 2024

Join

Wisconsin

1922

WI

ph

WINTER/SPRING

WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS

interim

JEAN

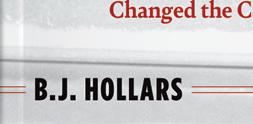

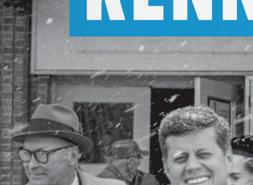

copy editor JODY CLOWES arts editor HUSTON DESIGN design & layout ISSN 1558-9633 25 facebook.com/WisconsinAcademy twitter.com/WASAL instagram.com/WatrousGallery Book Excerpt 46 “Chance Encounters,” Wisconsin for Kennedy B.J. Hollars @ Watrous Gallery 50 Playground and unearthed Fiction 54 The Goddess of Illicit Choices Susannah Daniel Poetry 64 2023 Honorable Mentions Adam Fell, Kelly R. Samuels, Marnie Bullock Dresser, Stephen Espada Dawson, Emily Bowles Book Reviews 70 Blood Diamonds by Catherine Young Reviewed by Martin Andrew 71 The Green Hour by Alison Townsend Reviewed by Jessica Becker Climate & Energy Spotlight 72 Community Science is Fueling Wisconsin EcoLatinos Lulu Fregeso

Imsland

Copyright © 2024 by the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited. Postage is paid in Madison, Wisconsin.

BRENNAN NARDI

editor

LANG

Rachel

From the Director

Spring emerges and we can’t help but have a lighter step, feel encouraged as color brightens the landscape, and enjoy moments lingering outside. I am particularly grateful to be a part of the Academy this spring.

In the midst of election intensity and divisive politics, the Academy is focused on connecting people with different perspectives through the shared exploration of timely and timeless topics.

Even with differences of opinion on important issues, Wisconsin is still a place where people have much in common. The experiences we have together can increase our understanding of one another, as well as the world we share.

It was this goal that inspired Bloom: a season of poetry, a series of events unfolding over the next couple months across the state. A showcase of poets and their works, Bloom will explore and illuminate both individual perspectives and shared themes. These events will culminate with a reading and book signing by U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón. Find more details on the back cover of this month’s issue and at www.wisconsinacademy.org/events.

I’ve been reading works by Ms. Limón and as an exuberant star gazer, I sought out In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa. In collaboration with NASA, this poem will be engraved on the Europa Clipper spacecraft and travel 1.8 billion miles to the Jupiter system. In the poem, we are reminded that, it is not darkness that unites us, but our shared existence on earth and our shared humanity.

Erika Monroe-Kane, Executive Director

Erika Monroe-Kane, Executive Director

In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa

Arching under the night sky inky with black expansiveness, we point to the planets we know, we pin quick wishes on stars. From earth, we read the sky as if it is an unerring book of the universe, expert and evident.

Still, there are mysteries below our sky: the whale song, the songbird singing its call in the bough of a wind-shaken tree.

We are creatures of constant awe, curious at beauty, at leaf and blossom, at grief and pleasure, sun and shadow.

And it is not darkness that unites us, not the cold distance of space, but the offering of water, each drop of rain, each rivulet, each pulse, each vein. O second moon, we, too, are made of water, of vast and beckoning seas.

We, too, are made of wonders, of great and ordinary loves, of small invisible worlds, of a need to call out through the dark.

4 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS

Sharon Vanorny

News for Members

MEMBERSHIP DRIVE

In just the last year, the Wisconsin Academy’s programs have engaged audiences from ages 9 to 91 years old, from 63 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties. Many were inspired to become new members and support the Academy’s mission. We are grateful for their support. Now we are asking for your help to reach even broader audiences. If you value the Wisconsin Academy, the Wisconsin People & Ideas magazine, and our programs, please consider sharing the gift of a Wisconsin Academy membership with someone in your life.

VISUAL ARTS ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS

Every two years, the Academy partners with Wisconsin Visual Artists and the Museum of Wisconsin Art to present the Wisconsin Visual Arts Achievement Awards. These awards recognize educators, writers, visual artists, exhibition teams, and community advocates whose contributions significantly enrich life in our state. Join us April 14, 2024, at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend for the awards ceremony. Learn more at wisconsinart.org/wvaaa-24.

BLOOM POETRY INITIATIVE

Please join the Wisconsin Academy this spring for Bloom: a season of poetry. This series features events such as Poetry and the Natural World, a talk and book signing by the U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón on the evening of Thursday, May 23, 2024, at the Overture Center for the Arts. We hope you or an organization that you represent will consider partnering or sponsoring one, or perhaps all, of these engaging events.

SPONSORSHIPS

If you are interested in sponsorships, contact Director of Development Zack Robbins at zrobbins@wisconsinacademy.org or via phone at (608) 733-6633 x16. If you are interested in partnering with the Academy on Bloom , contact Executive Director Erika MonroeKane at emonroekane@wisconsinacademy.org. If you want to attend one or more of these exciting events, visit our website at www.wisconsinacademy.org/bloom-season-poetry.

THANK YOU NEW ACADEMY MEMBERS!

Mary Sue Adey

Lisette and Darrell Aldrich

Brian L. Anderson

Wendy Anderson

Irmgard Andrew

Jennifer Angus

Jennifer Anne

Elizabeth Babette Wainwright

Lisa Marie Barber

Adriana Barrios

Al and Shirley Beaver

Robert N. Beck

Mary Bero

Mr. Michael R Betlach

Doug and Pam Bradley

Mary Kohl

Ann Brusky

John Bates and Mary Burns

Debra Byars

Ms. Cindy A. Carter

Matthew Cashion

Yeonhee Cheong

Portia Cobb

Dr. Clifton Conrad

Trent Miller and JL Conrad

Angelica Contreras

Sarah Crittenden

Susanna Daniel

Terry Daulton

Tara Daun

Katherine de Shazer

The Dickinsons

Jane Doughty and David Wood

Elizabeth Feder and Mark Johnson

Jason Fletcher

Anwar Floyd-Pruitt

Dick Folse

Jennifer Garner

Lilada Gee

Samer Ghani

David and Anne Giroux

Melody Hanson

Allyson K. Hanz

Holly Hilliard

Karen Ann Hoffman

Ann Huntoon

Wilson Irigoyen Quiroz

Jill Renee Iverson

Dennis James

Mahanth Joishy

Frank Juarez

Mary Juba and Charles Wiesen

Ms. Edwina Kavanaugh

Jodi Kiffmeyer

Sara Kiiru

Jayne King

Taylor Kirby

Jackie and Doug Kruse

Joel Kuennen

Madeline Grace Martin

Mandi McAlister

Bill McBeth and Heidi

Dyas-McBeth

Linda McCarty

Katherine E. McCoy

Gerard and

Alice McKenna

Christine C. Melgaard

Emily Merisalo

Jill Metcoff

Don and Mary Miech

Betsy Morgan

Rhianon Morgan

Jeffrey Morin

John Mulvihill

Tim A. Murphy

Kimberly A. Nash

Doug Nelson

Linda Nelson

Donna Neuwirth

Debra Nichols

Michael Notaro

Louise Nutter

Rebecca Oettinger

Jill Olm

Judy Olson and Richard Stollberg

Kurt Olsson

Ann Orlowski

Maria Otto

Nancy Peterson

Diane Pflugrad Foley

Yvette M. Pino

Carolyn Pittman

Jo Preston

Chuck Pruitt

Gary Puta

Jane Radue

Kathleen Rasmussen

Fred and Janice Redford

Adriana Reilly

Darvin Reilly

Liam Reilly

Angela Richardson

Dan Rosati

Katherine Steichen

Rosing and Mike Rosing

Thomas Loeser and Bird Ross

Mr. Jeff Rusinow

Ms. Juanita Schadde

Nancy Schraufnagel

Rita Sears

Rae Senarighi

Bret Shaw PhD

Kristin Sherfinski

The Sinskys

Wendy Skinner

Isa Small

Kristin Solander

Dale and Deborah

Sproule

Robert Alan Steffen

Dee Sweet

Julie Swenson

Scott Terry

Kathy Thome

Alice Traore

Nicholas A. Tseffos

Peggy Turnbull

Marijo and John

Van Der Vaart

Leslie Walfish

David and Nancy Walsh

Robert Whitcomb Fulton

Ally Wilber

Susan Wirka

WINTER / SPRING 2024 5

HUMANITY UNLOCKED

While in prison, Mark Español received his first college credits from University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Odyssey Behind Bar’s English class.

“It made me feel human again,” Español says of his experience crafting and reading his personal narrative to the Odyssey class.

The powerful insight that often comes from such important moments is explored in a new season of the Human Powered podcast from Wisconsin Humanities. The new series, called Humanity Unlocked, offers a unique opportunity to hear from people who have been incarcerated about how creative writing and humanities education can transform understanding of oneself and the world.

Episodes of the new podcast will explore the impacts of art exhibits, storytelling, and poetry workshops on prisoners; what happens in classrooms where college students learn alongside incarcerated students; and the benefits of prison newspapers for people inside and outside.

Today, more than 35,000 residents of Wisconsin are serving time in prisons and jails. Human Powered offers the uncommon opportunity to hear directly from current or formerly incarcerated citizens, as well as advocates working to make the experience of incarceration less de-humanizing.

“I got to interview people about how they think about their own humanity, and how they keep their curiosity and creativity alive in a space that is not designed with their humanity as a priority,” says Adam Carr, a public historian and co-host of the podcast. The six-part series is also co-hosted by Dasha Kelly Hamilton, the former Wisconsin Poet Laureate, who ran Prose & Cons workshops in Racine Correctional Institution and founded A Line Meant, a poetry exchange for people living in Wisconsin prisons and around the state.

Listeners can find the Human Powered podcast in any listening app and at wisconsinhumanities.org/podcast.

—Jessica Becker

SHORT STORY NIGHT AT THE PUB

It’s a Monday evening but the inside of Lion’s Tail Brewing Co. in Neenah, Wisconsin, is packed with so many people, it feels like a Friday evening fish fry. It’s Short Story Night, and an equal mix of men and women, from college students to retired folks, are discussing Erin Somers’ short story, Ten Year Affair, from the 2022 Best American Short Stories collection. After a conversation that touches on everything from the mundanity of marriage and child rearing to a debate about the ending of the story, the host, Richie Zaborowske, a librarian from the Neenah Public Library, connects with the author via Zoom for an interview plus audience questions. The interview is lighthearted and covers a broad range of subjects, from writing advice to the symbolism of a character’s toothpick habit. To finish the evening, Zaborowske hands out copies of stories for the next session of Short Story Night and just about everyone, plus a few newcomers, will attend again next month.

Celebrated writers have included Bobbie Ann Mason, National Book Award Finalist Deesha Philyaw, and National Book Award Winner Phil Klay. While the group occasionally dips into classic stories (Hemingway, Carver, Ferber), contemporary stories are preferred since they allow the group to discuss present-day topics.

The group meets the second Monday of each month at 7 pm. Visit www.neenahlibrary.org for a copy of the short story and complete details. On April 8, the evening will feature Wisconsin author and former Wisconsin Academy communications director Christopher Chambers.

—Richie Zaborowske

6 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS HAPPENINGS

Nicole Acosta

Richie Zaborowske

HONORING ACADEMY FELLOW RICHARD DAVIS

The world lost jazz great and social justice champion Richard Davis last fall at age 93. A true Renaissance man, Davis lived every decade of his life in earnest, sharing his gift as a premier bassist with some of the finest musical artists in the world, and then bestowing his gifts as an educator and activist to generations of students and citizens at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

As a musician, Davis honed his craft in his hometown Chicago before heading to New York, where his live music career flourished in the 1960s followed by a string of recording successes in the 1970s. In the Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll published in 1991, his work with Van Morrison on the album Astral Weeks, was revered as “the greatest bass ever heard on a rock album.”

Davis explored bass in a wide range of musical genres—from his first-love jazz to rock, pop, and classical. At the peak of his 23-year career, he was sought after by the greatest artists of the times: singers Sarah Vaughan and Frank Sinatra; singer/songwriters Bonnie Raitt and Bruce Springsteen; and maestros Igor Stravinsky and Leonard Bernstein.

In 1977, he was recruited by UW—Madison’s Mead Witter School of Music, where he taught string bass, jazz history, and improvisation. In 1993, he co-founded the Richard Davis Foundation for Young Bassists to give emerging musicians who attend an annual conference the opportunity to learn from and perform with professionals from across the country.

In 1998, Davis founded the Retention Action Project at UW–Madison to address the multicultural climate and graduation rates for students of color. Two years later, this grassroots approach to social justice led him to found the Madison chapter of the Institutes for the Healing of Racism, and to host the group’s meetings at his home for more than 15 years.

In 2004, Davis was inducted as a Wisconsin Academy Fellow. He was honored as a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master in 2014.

An extraordinary man, Davis will perhaps best be remembered for so generously sharing his countless gifts with Wisconsin and the world.

—Brennan Nardi

WINTER / SPRING 2024 7 HAPPENINGS

Bryce Richter / University of Wisconsin–Madison

8 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS W ISCONSIN TABLE

Anne Motoviloff

The author on a recent duck hunt to the Prairie Pothole region of North Dakota.

ONE FATEFUL BITE ON THE CONSEQUENCES OF EATING WILD GAME

BY JOHN MOTOVILOFF

It’s been three decades since I took my first bite of wild game. It was the fall of 1992, and, fresh out of graduate school, I had just begun my first real job—production manager for scholarly journals at the University of Wisconsin Press. At lunch time one day, my size 13 Doc Martens clambered down the oak stair treads. The Journals Division was one of three Craftsman style houses that—along with a warehouse once belonging to the defunct Fauerbach Brewery and still smelling of must and grain—made up the Press’s quarters at the time. Opening the refrigerator and realizing my leftover pot roast was at home, I was hit by a blend of low blood sugar and sadness.

WINTER / SPRING 2024 9 W ISCONSIN TABLE

10 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS W ISCONSIN TABLE

Hunt for Food students clean their harvest at the Beaver Dam Conservationists facility in Dodge County.

John Motoviloff

The one block to Fraboni’s Deli—with its spicy olives and cured meats—felt miles away and, anyway, I didn’t have money for a sandwich. I stared out the window at the leaden sky and the railroad tracks beyond the Press buildings. Just then, I heard the ding of the microwave door . A commingling of meat and citrus filled the air. My supervisor and Journals Manager, Steve Miller, divided the contents of the Tupperware he’d heated onto two plates and slid one down the counter to me. I grabbed hold of a bird leg cased in crisp brown skin and flecked with sauerkraut. Dark, tender meat fell from the bone. The taste stirred something primal in me. It was at once rich and lean, steak and poultry—unlike anything I’d eaten and magically satisfying. I asked the bluntest and—it would turn out—most transformative question I could muster: What is this and how do I get more?

RATHSKELLERS AND SMOKING BARRELS

Steve told me the meat was wild duck that he’d shot on the Mississippi River the previous weekend. Moreover, he invited me hunting and we were often joined by his friend and Associate Press Director, the late Ezra “Sam” Diman. My interest caught like brushfire, and the two of them were just the kind of mentors a young hunter needs—wool-clad and dependable, tempered by a gallows humor that salved the sting of shots and outings gone awry. We hunted far and near. The Lucey Farm and the overgrown right-of-way behind the School for Girls. French’s Creek and Grand River and Hog Island. Rugby and Aberdeen, Jamestown and Gackle. There were mustard yellow duck skiffs and decoys made from cork salvaged from a refrigeration plant. Dusty rathskellers turning out great racks of pork ribs atop crispy potatoes. There was the smell of cordite, sharp in the cold air, as we crouched between prairie potholes, the barrels of our Wingmasters smoking, the sun bleeding out into the Western sky.

Sam and Steve gave me heaps of encouragement and guidance as I learned to hunt: first squirrels and rabbits, then birds, and ultimately deer. They were the “social support” one hears about in outdoor skills research. Their steadfast company notwithstanding, they were not, per se, the reason I decided to try and—ultimately to embrace—hunting. This was something I’d uncovered, as one might find an ancestral portrait or coat of arms deep within a fieldstone basement. This inner wildness was about pursuing—and eating—wild game. Or, more accurately, connecting with something that had long been part of human existence and only recently had faded from view. As I progressed as a hunter, I also grew as a chef, beginning with simple sears over glowing coals and black skillets and then progressing to savory stews like Squirrel Burgoo or Rabbit Cacciatore and sharing them with loved ones. While I vaguely sensed that I was on a path, I would never have guessed that, decades later, its arc would have been so profound and circular.

With my first steady paychecks, I began to acquire the material trappings one needs to become a hunter. I bought a used Remington Wingmaster, a few burlap sacks of decoys, a Karsten’s duck skiff. My wife Kerry and I used the money we received from our wedding as a downpayment for a cabin on the banks of the Kickapoo River. I hunted feverishly into my 30s, accompanied by

Pheasant with Dried Apricots

This recipe is adapted from the cookbook Wild Rice Goose and Other Dishes of the Upper Midwest by John Motoviloff. It is a low-and-slow dish that gives a nod to ingredients such as dried fruit and cinnamon that evoke Central Asia, where pheasants originated.

INGREDIENTS

2 Pheasants, cut into serving pieces and seasoned with salt and pepper (or equivalent weight in thighs and drumsticks)

Flour for dredging

¼ C olive oil plus 2 Tbsp butter (more as needed)

2 C chicken or pheasant stock, heated to just below boiling.

I C dried apricots

1 C yellow raisins

1 cinnamon stick

3 Tbsp honey, or more to taste

Additional salt and pepper to taste

Cornstarch for thickening if needed

Preheat oven to 275 degrees. Place shallow baking pan in the oven.

Dredge pheasant pieces in flour and shake off excess.

Heat a large Dutch oven, Le Creuset, or similar lidded, ovenproof vessel on the stovetop. Add oil and butter and heat until it sizzles. Brown pheasant pieces in batches, being careful not to crowd the pan. Place browned pieces in the baking pan as you work.

When all pieces are browned, scrape up any remaining bits with a spatula or wooden spoon. Deglaze the pan with stock. Replace the pheasant pieces. Add the dried fruit plus the cinnamon stick and honey.

Bake, covered, until pheasant is fall-off-the bone tender. Taste the liquid to see if it needs more salt, pepper, or honey.

If the sauce is too thick, add broth or water. If it is too thin, add cornstarch dissolved into a few tablespoons water.

Serve over saffron rice.

WINTER / SPRING 2024 11 W ISCONSIN TABLE

a lithe black Labrador retriever named Tasha, and worked at various editorial jobs. The more game I ate, the more I wanted to learn about cooking it. Books from LL Bean, Remington Arms, Ducks Unlimited— as well as spiral bound cast-offs and jottings on scrap paper—were my bedtime reading. In my 40s, narrowing the gap between my personal and professional worlds, I became a full-time freelance outdoor writer. Scores of articles in the conservation press and then publication of Driftless Stories and Fly Fishers Guide to Wisconsin and Iowa followed. Then came invitations to run game cooking seminars at the Journal-Sentinel Sports Show, the Wisconsin Writers Festival, and DNR facilities. By 2008, I had collected enough recipes to pen my first cookbook, Wisconsin Wildfoods Wild Rice Goose and Other Dishes of the Upper Midwest followed in 2013.

In 2014, I took the position of Shooting Sports Assistant at the Wisconsin DNR. A central job duty was helping to design and implement a course called “Learn to Hunt for Food,” a brainchild of then Hunting and Shooting Sports Program Specialist Keith Warnke. The goal here was to reproduce for novices just the kind of experience—and support—that I had gotten. Following five years of work at WDNR, I’ve been fortunate enough to continue this rewarding career on the nonprofit side as the Wisconsin Recruitment, Retention, and Reactivation (R3) Coordinator for the National Wild Turkey Federation (from 2017 to 2022) and since then as the Wisconsin R3 and Outreach Coordinator for Pheasants Forever.

DIVING INTO DEMOGRAPHICS

Hunt for Food classes (WDNR adopted the term Learn to Hunt for these classes in 2023) didn’t just happen. This, like all stories, is backed by other stories. To begin this one, hunting license sales in the United States and Wisconsin peaked in the 1980s and 1990s. Since that time, the demographic “bubble” representing Baby Boomers (those born between 1948 and 1964) continues to advance across the age spectrum. In fact, the average age is closing in on 70, which is when most people stop hunting. Of course, one can point to many Baby Boomers who do hunt—and avidly—but those cases tend to prove the general rule that this age cohort is becoming and ultimately will be too old to engage in the tasks associated with hunting: climbing tree stands, dragging deer from the woods, following bird dogs over rough terrain.

This is important because conservation funding comes from hunting licenses sold, and even more comes from the 11 percent Pittman-Robertson federal tax placed on firearms and ammunition. In other words, declining hunter numbers spell serious economic and relevance problems for the conservation community. Historically, creating new hunters to backfill those who aged out has taken care of itself. A high density of hunters, who in turn taught their children to hunt, kept the pool of license buyers robust. But as America has grown more urban, as average family size decreases, and as more pastimes (like digital media and team sports) compete for the family calendar, fewer hunters are being produced. This decrease is expected to become more pronounced as the Baby Boomer cohort continues to age.

At the same time—and this can perhaps be viewed as a happy coincidence—Americans in general and millennials in particular are becoming increasingly concerned about their food sources and food sovereignty—for meat in particular. It’s not difficult to see how

John Motoviloff

a ready-made sales pitch (secure your own ethically sourced meat through hunting) and an audience (millennials and others who eat meat but dislike factory farming) seem to suggest themselves. This line of thinking wasn’t lost on natural resources professionals like Warnke, who pioneered the first WDNR Hunt for Food class in 2012.

Warnke, who is now the Midwest R3 and Relevance Coordinator, put it this way: “This strong interest in food sources easily carries over to hunting. Killing meat themselves from a wild, sustainable resource is very attractive. It builds on their values of conservation, land ethic, and animal use.”

Not surprisingly, given the urban and suburban demographic of Hunt for Food participants and the students’ lack of exposure to firearms and animal processing, Hunt for Food classes are long courses rather than short ones. The many skills necessary to hunt— marksmanship and gun safety, field dressing and butchering, basic biology and regulations—are taught over something like 10 hours in the classroom and field. To get a sense of the class experience, readers can google the term “Hipster Hunter.” Alternatively, a literature search will reveal a wide range of publications covering similar stories over the last five years. A short list includes the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, National Public Radio, Slate.com, Outdoor Life, Field Stream, and MacLeans

Just as WDNR was among the first state agencies to offer courses like Hunt for Food, it now continues to lead the way in the realm of R3. As of fall 2023, four distinct conservation organizations have partnered with WDNR to create partner R3 coordinators: Pheasants Forever, the National Deer Association, Raised at Full Draw, and Pass It On Outdoors. While these nonprofits each have their own point of view, all four partner R3 coordinators share the aim of creating new hunters and are financed through Pittman-Robertson revenues.

According to WDNR R3 Supervisor Bob Nack, “Wisconsin DNR was one of the early leaders in recognizing the importance of outdoor experiences that occur when hunting, fishing, and trapping. We are excited to continue as a national leader in providing programs.”

12 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS W ISCONSIN TABLE

Women are the fastest growing demographic in hunting. Still, men make up the vast majority (88%) of hunters.

STUDENTS SPEAK

Because I was so affected by hunting, I have been keenly interested in how it affects others. Statistics are one way to prove a point, and one study of Hunt for Food students in Wisconsin shows that 40 percent of them became regular license-buying hunters. My own records suggest that this number may be closer to 50 percent. Further, all students were shown to hold a favorable view of hunting after completing Hunt for Food classes. These statistics may seem underwhelming and self-validating. If only half the students in a course on basket weaving go on to weave baskets, wouldn’t we question the worth of that class? And, if someone is considering taking a class, doesn’t this imply approval?

Considering the degree of behavioral change involved in going from being a nonhunter (someone who does not take the life of animals for food) to becoming a hunter (someone who takes the life of animals for sustenance within a strict code of regulations), one realizes that the bar is very high here. In fact, it is difficult to envision a change that is weightier than taking the life of another being. That said, if roughly half the sample set chose to undergo this change, the agent of change— Hunt for Food classes—can be viewed as a powerful catalyst. That students enroll in courses on which their point of view is already established tends to put the cart before the horse. While one can certainly take a course on a subject in which he or she is already interested and disposed to view positively. Just as often, one can enroll in a course about which he or she is undecided, ambivalent, or just plain curious. So, unless all students were unanimously positive about hunting prior to enrolling in Hunt for Food, it’s fair to say at least some underwent a change of opinion. Bolstering this are my observations as an instructor with more than a decade of teaching such classes: I’ve observed most entering students exhibit some degree of fear about using a firearm and taking an animal life. A unanimously positive subsequent view of hunting here suggests that this fear is allayed or overcome.

According to the current WDNR Hunting and Shooting Sports Program Specialist Emily Iehl, whose master’s thesis is cited above, “There appears to be lots of interest in Hunt for Food among people who didn’t grow up hunting. If we can offer relatable resources, experiences, and instructors, people are likely to take advantage of this.”

A brief scan of comments from Hunt for Food students shows similar sentiments. One student says, “I took a series of these classes, and now hunting and fishing for my own protein are an integral part of my life.” Another adds, “Without this class, I would not have felt prepared to join a group of seasoned hunters. The programs were a gift to help me carve out time for being outdoors, learning new skills, and navigating the ethics and emotions of hunting with a friendly and welcoming group.”

Still another says, “My family gathered and we feasted upon the wild turkey meat. As we digested, we could feel the meat nourishing our bodies and spirits, slowly becoming and building our life-filled molecules. The impact of this turkey hunt and the subsequent memories and nourishment it provided are simply intangible. Hunting and eating locally

Duck à l’Orange

There are many versions of this classic dish, and it’s served in both high-end restaurants and at the homes of humble duck hunters. The sharp taste of citrus contrasts nicely with the rich and meaty fowl, making it a winning combination. Take care not to overcook wild duck, as it becomes livery and tough. Interestingly, the author’s first bite of wild game was a version of Duck a l’Orange complimented with sauerkraut and caraway seeds.

INGREDIENTS

Breast fillets of prime-quality ducks (such as mallard, wood duck, pintail with skin left on). Substitute domestic duck breast, which will require slightly longer cooking, if wild duck isn’t available.

Salt and pepper

Flour

4 Tbsp clarified butter (butter with dairy solids removed)

1 C sherry or port

2 oz currant jelly

1 Tbsp grated orange rind

1 tsp of fresh grated ginger

1 C fresh squeezed orange juice

Water or broth as needed

1 Tbsp sugar (more as needed)

1 Tbsp cornstarch dissolved in a bit of cold water

Preheat oven to 200 degrees.

Salt and pepper duck breasts. Dredge them in flour and shake off the excess.

Heat a large cast iron or nonstick skillet on the stovetop. Add butter.

Brown each breast fillet well on either side. Do not cook the duck fully at this point; it should still be cool and pink at the center. Remove to oven.

Deglaze the pan with sherry. Add the currant jelly, orange rind, ginger, and orange juice. Simmer and reduce to half the original volume.

If too little liquid remains, add broth or water. Stir in the corn starch-water mixture. Taste the sauce. If it seems right to you, leave as is. IF you find it too tart, add sugar a little bit at a time. Check for salt and pepper and add as desired.

Replace the duck breast in the sauce, making sure to coat on both sides. Cook until just-done. Serve on the side of wild rice or mashed potatoes. A robust Côtes du Rhône or Bordeaux will round out the meal.

WINTER / SPRING 2024 13 W ISCONSIN TABLE

is a way of life that is as natural as the seasons.” Finally, another expressed that “these programs were my guide into the unknown ... without them, I’m certain this would still be a distant dream.”

DEEP BONDS AND WALKING SHADOWS

Novice or veteran, mentor or mentee, we live lives that are brief and bound by work and family. And yet, in this sojourn we undertake without mile markers, in this theater where we’re given no playbills, we find ourselves connected to others. We share a common experience. As I had the good fortune to learn, I am compelled to teach. The people I’ve met through hunting—male and female, gay and straight, Black, brown, and white—have become an extended family. We’ve logged in what feels like a lifetime on duck marshes and uplands, trout streams and lakes, backyard barbeques and game dinners. A particular day in the grouse woods with one friend comes to mind. We decided to take a break from hunting in a field of blackberry and milkweed. We picked up the milkweed pods, and, whimsically, let the floss fly out into the autumn breeze, watching it slip away toward the Minnesota line and then finally fade into nothing. We laughed together, and then laughed some more. In addition to the humor, I also felt something else which I can only put into words after the fact. No matter how hard we strive, no matter how much we want to pass something along, we’re still just small specks in a vast and existential enormity. “Out, out, brief candle,” Shakespeare’s Macbeth tells us. “Life is but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more.”

John Motoviloff is the Wisconsin R3 and Outreach Coordinator for Pheasants Forever. He earned his Master’s degree in Philosophy from the University of Wisconsin—Madison in 1992. He has worked for the University of Wisconsin Press, the Wisconsin Historical Society, and the Wisconsin DNR. In addition, he is the author of several books about the outdoors including Wild Rice Goose and Other Dishes of the Upper Midwest. He has written for the Wisconsin Academy Review, Grays Sporting Journal, a wide variety of conservation publications as well as in Fodors Travel Guides and National Geographic. He lives in Madison, Wisconsin, with his wife Kerry and Labrador retriever Gypsy. He is an avid hunter, angler, forager, and cook.

14 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS W ISCONSIN TABLE

Emily Lehl

A quiet moment during a mentored squirrel hunt in Sauk County.

WINTER / SPRING 2024 15 VISITSHEBOYGAN.COM FdùÉv HIKE IT BIKE IT LIKE IT

16 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS P ROFILE

TJ Everett/Stages Photography

Milwaukee PBS Producer Everett Marshburn with Clayborn Benson, founder and curator of the Wisconsin Black Historical Society and Museum

LET IT SHINE

AFTER FIVE DECADES IN PUBLIC TELEVISION, EVERETT MARSHBURN STILL HAS STORIES TO BRING INTO THE LIGHT

BY JAMES E. CAUSEY

Ask anyone who’s worked with award-winning television producer Everett Marshburn to describe him, and the consensus is clear.

“Great storyteller.”

“He’s committed to telling the untold stories of the Black community and the Black condition.”

“Great listener and ultimate professional.”

“Whatever he puts his stamp on, you know it’s going to be great.”

“He is a great researcher who understands how to showcase a story.”

“Incredible eye and a man loaded with an encyclopedia of journalistic knowledge.”

WINTER / SPRING 2024 17 P ROFILE

18 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS P ROFILE

Top: Friends and colleagues Everett Marshburn and James Causey. Left: Torean Smith, a student in the Milwaukee Area Technical College’s TV Production Course, had the opportunity to be part of the studio crew. Right: Milwaukee PBS Multimedia Producer/Journalist Alexandria Mack with her daughter, Gia.

TJ Everett/Stages

Photography

I, too, have nothing but praise for Marshburn. For nearly a decade, I’ve worked with him as a news reporter at Black Nouveau, one of the country’s longest-running series on public television and an Emmy-winning program of Milwaukee PBS. Marshburn has produced the show, now in its 32nd season, since his arrival in Milwaukee in 2006.

As a reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, I was a frequent guest on Black Nouveau, discussing a variety of topics. After several appearances, Marshburn saw enough in me to put me on the other side of the camera, interviewing people who were having a positive impact in the community. The switch was not easy, but Marshburn took his time mentoring me, and I started to see the improvements.

His advice was simple: “You know what you’re doing. Just relax and be yourself.”

Marshburn has accomplished much and received many honors in his nearly 60 years in public television. He’s won five Emmy Awards, 14 National Association of Black Journalists Salute to Excellence Awards, and two Milwaukee Press Club Awards. He was the 2014 recipient of the Bayard Rustin Leadership Award from Diverse and Resilient in Milwaukee, the 2012 Black Excellence Awardee in the field of Media from The Milwaukee Times, and a was a 2013 Inductee into Maryland Public Television’s Alumni Wall of Honor. In November, it was announced that Marshburn would receive one of the highest honors in television when he was inducted into the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences 2024 Gold Circle, the first person in the state to be bestowed with this honor.

Marshburn’s award goes beyond his five decades in the business, honoring his lifelong commitment to storytelling and shedding light on issues important to the African American community.

BREAKING INTO THE BUSINESS

Marshburn’s love of media began as a teenager with his passion for spoken word, poetry, music, Broadway, theater, and, of course, film and TV. The Baltimore, Maryland, native wrote plays for his church and continued to write several plays as a student at Morgan State University. When Marshburn switched his major from education to history, he became friends with Thomas Cripps, a professor at Morgan State, who wrote and lectured about the history of African-American cinema. Marshburn helped Cripps with research and editing, and in 1968, Cripps introduced him to Ken Resnick, a film director and producer. Resnick had been hired to head what was to become the film department at the Maryland Center of Public Broadcasting. Maryland was starting to build a public television system to serve its 23 counties and the city of Baltimore. In April of 1968, Marshburn received a call from Resnik to come in and talk.

“I was looking for a summer job so I could go back to school to work on my degree, and he offered me a full-time position as a production assistant that started that summer,” says Marshburn.

By the late 1960s, the nation was in steady conflict. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. Protests and riots erupted in Washington, D.C., Chicago, Baltimore, Milwaukee, and Cleveland, and the Kerner Commission Report warned: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one Black, one White – separate and unequal.” The Commission criticized newspapers and television for failing to report on African-American life adequately or to employ

more than a token number of Blacks. The bottom line was that Blacks wanted a kind of journalism that spoke to them and provided them with news and information they could use. At the young age of 20, Marshburn would become part of this change.

“I always said I didn’t choose television; television chose me,” says Marshburn. “I’ve just been lucky enough to meet the right people and be able to make some impact.”

The entry-level position got Marshburn in the door and within a year he was a film cameraman. One of the shows he shot was called Strategy for Action, an urban affairs program that featured people and organizations finding solutions to the problems of urban America. In 1974 Marshburn created a series for the show called “Burglar Proofing,” documenting how easy it was to break into homes, using three ex-burglars as sources. Viewers could call in to request informational packets on how to prevent home invasions. The program earned him his first Emmy.

NABJ HOSTED A PANEL ON AIDS

For Marshburn, public television was an effective and influential vehicle to tell stories about African Americans through a more authentic lens. In the late 1980s, as the AIDS epidemic was sweeping the country, Marshburn again used public TV as a platform to raise awareness. Marshburn understood that AIDS was not just a gay, white man’s disease but a public health emergency that the African American community had yet to fully comprehend. This became apparent in 1988 when he attended a National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) convention, which hosted its first panel on AIDS.

“There were five people on the panel and three in the audience, and I was one of the three,” Marshburn says.

While the panel provided great information, the stigma and homophobia surrounding the disease kept people from attending. When Marshburn returned home, he knew he had to get information out to communities, which led to his nearly two-year project, Other Faces of AIDS

“The thing that struck me was that the time from diagnosis to death for a white person with AIDS was two years at that point, and the time for a Black person was six months,” says Marshburn. “I wanted to know why and what was going on.”

With what was considered a meager $25,000 budget, Marshburn and his team told stories from the frontlines in Miami, Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, New Jersey, New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. In Los Angeles, he met Bishop Carl Bean, who led a congregation that served as a haven for the Black LGBTQ community, and also founded an organization that brought care and attention to poor people of color living with HIV and AIDS in South L.A., when most of those efforts were being funded by white communities.

The one-hour segment aired in 1989 and featured then-U.S. Surgeon General Charles Everett Kopp, who cautioned against the stigma associated with AIDS and HIV: “We are fighting a disease, not people. Those already affected are sick and need our care, as do all sick patients. The country must face this epidemic as a unified society.”

Marshburn remembers the AIDS story as one of the most difficult projects he encountered in his career. Sources would go on the

WINTER / SPRING 2024 19 P ROFILE

“I just really wanted to speak up,” said 5th grader Zaida Smith on why she entered the citywide student speechwriting contest on the topic of “What Affects One … Affects All,” the central theme from Dr. King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Smith (pictured here with Marshburn) had the opportunity to give her speech on the Black Nouveau program.

record and then back out. Interview subjects feared how the story would be told–how they might be portrayed in a negative or stereotypical light. Yet, he persevered, knowing that the Black community was on the edge of a life-threatening catastrophe unless people were made aware of the dangers of HIV and AIDS.

WELCOME TO MILWAUKEE

After a string of layoffs in Maryland, Marshburn would make his way to Milwaukee after seeing an opening for a producer job at Milwaukee PBS on the NABJ listserv. He had visited Milwaukee during NABJ’s national convention and saw similarities between Baltimore and Milwaukee in terms of their proximity to even larger metropolitan areas and similar demographics for African Americans. Joe Savage, co-creator and former producer of Black Nouveau , was familiar with Marshburn’s work—they often competed against one another for NABJ awards—and felt confident Marshburn would take the show to the next level.

“I first met Marshburn 25 years ago,” recalls Savage. “We met in different cities, and over time, we became friends. His journalism integrity is unmatched. I had no doubt he would be excellent. I’ve never questioned his ability, and he’s never questioned mine. We have mutual respect, so when he came to Milwaukee, there was nothing I taught him that he didn’t already know. He’s a good storyteller, and we need someone to tell our stories.”

Liddie Collins, Emmy-winning co-creator, producer, and host of Black Nouveau, says Marshburn’s focus on positive change and impact has been one of his greatest contributions to Milwaukee and beyond.

“What I love the most about Marshburn is that he’s never been afraid to tackle tough issues,” says Collins. “What he does and stands on is what we will do about it to improve our conditions.”

Over the years, Black Nouveau has changed and evolved with the times. Once a weekly, the show now airs once a month. Personalities have come and gone. What has remained, though, is the quality of and commitment to the genre of storytelling. In six-minute segments, the program offers its viewers a slice of Black life that often goes untold.

In many ways, Marshburn’s work is its own form of activism as evidenced in two of his best-known documentaries: Freedom Walkers for Milwaukee , which aired on PBS Milwaukee in 2011, followed the city’s historical importance in the Civil Rights struggle of the mid-1900s, leading to its nickname, “The Selma of the North.” In 2017, a Black Nouveau special, Crossing the Bridge, depicted the tumultuous protest marches that pushed for the Fair Housing Act in 1968. The piece, for which Marshburn earned an Emmy Award, brilliantly forged a connection between the veteran marchers and the activism of today’s youth, who express themselves through spoken word and social justice movements, tackling the challenges that remain these 50 years later.

20 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS P ROFILE

TJ Everett/Stages Photography

Veteran broadcast documentary producer Greg Morrison calls Marshburn a “complete journalist.” In characterizing Marshburn, Morrison reflects on an old saying that the job of the media is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.

“Marshburn truly comforts the afflicted,” says Morrison. “He listens to them, and he gives them a voice. You can see it in everything he does.”

Morrison and Marshburn met in Chicago in 1997 while working with young journalists at the NABJ convention, and discovered they shared many of the same acquaintances in Baltimore. Morrison considers Marshburn a great friend, who loves great food, like Baltimore-style yakamein, the Baltimore Ravens, and a competitive game of pinochle.

I asked Marshburn, 75, if he was ready to slow down—maybe watch more football and play more pinochle: “Well, I still think I have something to offer because there are still stories out there that need to be told.”

He left me with a quote by civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, who organized the 1963 March on Washington but was nearly written out of history because he was openly gay.

“God does not require us to achieve any of the good tasks that humanity must pursue. What God requires of us is that we not stop trying.”

“This is what I live my life by,” says Marshburn.

James E. Causey is an award-winning special projects reporter and columnist for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel . He has spent over 30 years as a professional journalist after becoming the first African-American high school intern at the Milwaukee Sentinel at age 15. He worked for the paper every summer through high school. He worked as a night cops’ reporter, earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism at Marquette University, followed by an M.B.A. from Cardinal Stritch University. In 2008, he was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard University, where he studied the effects of hip-hop music on urban youth.

WINTER / SPRING 2024 21 P ROFILE

Michael Ware, Blue Anti-Oxygens 2, 14” x 17” x 14”, Colored Porcelain, Silica Sand, Claze, and Glaze, 2022

Michael Ware, Blue Anti-Oxygens 2, 14” x 17” x 14”, Colored Porcelain, Silica Sand, Claze, and Glaze, 2022

CRAFTING BRILLIANCE

CERAMIC ARTISTS PERFORM ALCHEMY WITH GLAZES AND PIGMENTS

BY SARAH E. WHITE

In the world of pottery, where creativity and craftsmanship converge, some artists are not just molding and glazing their clay, but creating their own unique surface treatments. Experiments with glazes lead these artists down rabbit holes to places where earthy elements transform into never-before-seen hues and textures.

WINTER / SPRING 2024 23 ESSAY

At the Center for the Visual Arts in Wausau, the studio produces 35 custom glazes. "It's like cooking," says potter Ron Hay. "There are thousands of recipes."

The Center for the Visual Arts in Wausau (CVA-Wausau) is spreading the joys of glaze-craft in central Wisconsin. Opened in 1976 and now located in a historic arts block in Wausau’s downtown, CVA-Wausau is a dynamic and inclusive space for both emerging and established artists. The Center takes pride in its education program, which offers workshops, classes, and lectures for both aspiring and seasoned artists.

Mara Mullen, Director of Education, finds that students in CVA-Wausau’s pottery classes come in “focused on the clay body— making a mug, a bowl, a vase—rather than thinking about how it might be glazed. They’ve never been exposed to this aspect of ceramics,” she said. “They look at our glaze board and they can be a little overwhelmed.” The studio, where potter Ron Hay has been artist-in-residence since the 1990s, currently produces 35 custom glazes. “It’s like cooking,” Hay said. “There are thousands of recipes. Potters share them, and there are books full of them.” But he noted that outcomes can still be unpredictable. “A lot of times, a recipe doesn’t work when you mix it up, because your chemicals came from a different part of the country than the than the other ceramicists.” A slightly different molecular composition can yield a quite different result. But, said Hay, “You don’t have to be a chemist— you learn to adjust recipes through trial and error.” Because most students want to make functional ware, almost all of Hay’s housemade glazes are designed to be food-safe.

THE SCIENCE BEHIND THE SURFACE

People unfamiliar with ceramics may have admired the colorful surfaces of pottery without giving a thought to the “how” and “why” of their glazes. Glaze is a coating applied for both aesthetic and practical purposes, designed to adhere to a fired ceramic object. Glaze attributes vary widely, from glossy to matte, translucent to opaque, glassy-smooth to textural. Its main components are silica, which forms the glassy surface; flux that lowers the melting point to improve adherence; and alumina to stabilize the glaze. Silica comes from quartz, flux is often feldspar or boron compounds, and alumina is an element derived from clay. Additionally, pigments play a crucial role in ceramics, contributing to the rich palette of colors seen in glazed pieces. These finely ground substances are added to the glaze mixture or to the clay itself, to introduce hues and variations. Part of ceramic art’s appeal is the earth-bound nature of the materials involved.

Glaze components react in a kiln during the firing process. As the temperature rises, the glaze transforms from a powder into a molten, glassy substance. The right balance of silica, flux, and alumina, along with additional elements for color and texture, determines the final appearance of the glaze. Understanding this basic chemistry provides a practical foundation for ceramicists to experiment with different formulations to achieve specific effects on their pottery.

24 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS ESSAY

CVA-Wausau

Beyond the three main components, a variety of other materials can be added depending on the artist’s vision for the piece. For example, colors and textures can be customized, and glazes can be made to move in certain ways to achieve effects such as cracking, foaming, or dripping. A glaze’s behavior and appearance depend on how it is fired—the same glaze may turn out differently with different temperature, timing, and the atmosphere in the kiln. Adding or reducing oxygen or introducing wood, salt, or other materials will also affect a glazed object’s ultimate appearance.

Beginners can get started in ceramics with just an introductory level of knowledge, or choose to advance as far as they like; the range of knowledge among working ceramic artists is broad. Some, however, who fall down the rabbit hole and discover the intriguing world of pigments and glazes, are driven to learn the chemistry behind this wonderful alchemy.

David Harper, an interdisciplinary artist living near Racine whose work is in the collections of the John Michael Kohler Art Center and The Museum of Wisconsin Art, began working with clay when he realized he was using non-clay materials to create objects that imitated ceramics. “At any point, you can choose to stop or go deeper. Knowing the basics is important, like how hot to fire certain things to achieve certain effects. Then people might get into making their own glazes, achieving effects nobody has ever seen before.”

Some artists introduce pigments into the clay itself, not just the glaze. Michael Ware creates abstract ceramic sculptures and teaches ceramics at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He began working with stains and pigments to express his interest in “this geological world,” he said. “It was disappointing whenever I broke a little bit off a sculpture and it was white inside. Glaze is just on the surface, whereas when I color the clay, it has color the whole way through—like a rock.”

But, artists advise, do not start making glazes until you know how to do so safely. Understanding material hazards and proper use of studio equipment and tools is critical. Potters need to minimize aerosol particles and exposure to toxins. That means, when mixing clay and glazes, always wear a respirator and work with good ventilation systems; never eat or drink in the studio; wear safety glasses and gloves. Wipe down work surfaces and mop floors. Some glaze ingredients, like barium and lithium, yield beautiful effects but are toxic. The toxicity can range from mild skin irritation to causal factors in cancer. Kilns have their hazards, too. Loading and unloading heavy pieces can cause injury. While firing, fumes are present. It is important to avoid the area and/or use good ventilation and a respirator. Check that no combustible materials are located near a kiln before every firing. When producing functional ware, such as plates and mugs, use only food-safe glazes. Safety guidelines are reassessed regularly— otherwise, we might still use lead in glazes! Check for current information before working with glazes.

WHY GO DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE?

Potters choose to make their own glazes for several reasons including cutting costs, developing greater skill with their medium, and controlling the environmental impact of their work. But the reason most cited for diving into glaze-making is to achieve a specific creative vision.

The cost of commercial glazes often drives beginning potters to make their glazes. Simply setting up a studio requires an initial investment that can be steep even before purchasing dozens of glazes, which frequently cost more than twenty dollars a pint. Mixing glazes requires only common kitchen tools like a scale, mixer, and measuring utensils, and the ability to follow a recipe.

The educational value of learning to formulate and test glazes is undeniable; potters deepen their understanding of materials, chemistry, and firing processes through glaze-making. Mullen said, “With beginning students, we steer them towards our most predictable glazes because they put so much effort into making these precious objects. If they fail, it can turn students away from ceramics in general.” Ceramic-making involves not only experimentation but also failure. Learning to troubleshoot the causes of failures is important to the process.

Increasingly, ceramic artists are considering the environmental sustainability of their art form. Clays and the chemicals used in glazes are mined all over the world. Materials mined in one place are frequently shipped to distant locations for processing and then shipped again to the point of sale. Ware said, “I’ve become more aware of the environmental impact of ceramics and the environmental impact of all that transport.” Historically, potters lived close to sources of clay and mined the clay themselves. Today some

WINTER / SPRING 2024 25 ESSAY CVA-Wausau

potters are working with “wild clay,” finding raw materials nearby and screening out impurities to create workable clay.

Madison-based potter and ceramics teacher Joanne Kirkland makes porcelain sculptural pieces inspired by the pottery of the southwestern United States, Mexico, and Japan. She primarily uses Grolleg, a blended china clay from England, where some Grolleg mines are now depleted. Kirkland said, “I recently started thinking I should use more local materials, what with climate change and the impact of transportation.” She has begun experimenting with wild clay herself. So has Ware, who likes using the local pale-gold clay that, made into bricks, gave Milwaukee the name Cream City. From the sustainability of the raw materials, through managing the risks of the more dangerous chemicals in glazes, to the disposal of waste materials, potters are increasingly choosing materials and processes for their environmental sustainability.

Artistic expression is the foundation of every aspect of a ceramic artist’s work and the dominant reason for making glazes. Color palettes, surface effects, and where a particular idea for a piece fits on the spectrum from functional to sculptural all factor in, driving choices about pigments and glazes. Experimentation is an integral part of that process, as artists tweak formulas, test new combinations, and push the boundaries of traditional glaze recipes to achieve unique results. Harper said, “Every ceramicist I know has libraries of test tiles where they have added grain after grain of a certain mineral to change a pigment or change how a glaze flows. Control is the draw for a lot of people.”

And yet control must be balanced with openness to serendipity. Scott Draves of Door Pottery in Madison teaches beginning and continuing students through local community programs. “I conceive of a glaze for each piece before throwing it, a process that only a small percentage of potters do. The best work comes out of the surprises and mistakes I make.”

Rachel Imsland, a potter who serves on the board of the Madison Area Potters Guild, said, “I have to remind myself to have no expectations, because when I expect a pot to look a certain way it won’t. You always need to be open and be ready for a surprise.” Imsland set up a home studio during the pandemic. She began making glazes because she missed the ones available at the Midwest Clay Project, a community clay studio in Madison, where she had worked prior to COVID. At first, Imsland saw making her own glazes as a huge hurdle. “As a beginner, you just want to think about making pots. Somebody else, please make the glaze. But with practice, you find, it’s fun!”

ARTISTS SPEAK

Custom creation of glazes and pigments is taking place across Wisconsin in schools, universities, community spaces, and artists’ studios. Some are working in traditional techniques and some are digging deeper with experiments that erase the line between the clay body and the glaze.

Scott Draves creates functional ware inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement. This international trend in the decorative arts emerged as a reaction against the industrialization of the late 19th century. Its proponents championed craftsmanship, simplicity, and a return to traditional techniques in which the maker’s hand is visible. Draves recreates that style with pigments and glazes he customizes to mimic the originals, minus

the deadly lead content used in the glazes of a century ago. Like Draves, many of today’s ceramic artists are drawing inspiration from the ethos of the Arts and Crafts Movement, finding a potent source of creativity in its rejection of mass production and celebration of the handmade.

Kirkland took a ceramics class while studying fashion design in college, where she fell in love with the physical, tactile, experience of clay. “What drew me in was learning how to throw on the wheel; learning how to center was the hardest thing,” she said. “You have to be pretty centered yourself to do it. When you learn to use your body, that is a very magical experience.” Over the decades, she has evolved from an interest in functional objects to a focus on more metaphorical sculptural vessels. Throughout, her objects’ surfaces have been decorated with geometric representations of natural phenomena. Ancient pottery fascinates her; “I enjoy residing in a continuum of thousands of years of tradition,” said Kirkland. “It’s been a constant evolution and exploration, a dialogue with clay and glazes.”

CVA-Wausau’s Mullen started out primarily sculptural in her art, but after her teaching experience she now leans toward functional ware. “It’s a joy to create things I need and would like to use. But I do still love sculpture. I love rethinking the vase, rethinking the mug— how can I bring sculptural elements to these functional works?”

Harper considers himself not a ceramicist, but an artist who uses clay as part of his vocabulary. Originally from Toronto by way of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, he spent two seasons as the Kohler Arts and Industry Artist in Residence in winter 2012 and 2014. “There is a beautiful symbiotic relationship there,” he said. “Working in this very utilitarian environment, watching the grace, the dance of these factory associates working with the same material I use—it still affects the way I work in the studio, based on their model of efficiency.” Harper’s installations are cross-disciplinary and employ both traditional and nontraditional materials. “I make these small worlds that are so bizarre but are grounded by materials I choose because of their familiarity,” he said. “I choose colors and surface textures that are nostalgic.”

Christina West is an Associate Professor in Ceramics in the Art Department of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. While teaching an introductory ceramics class, West found herself growing enthusiastic about what glaze can do that other materials can’t. “In trying to get the students excited about it, I sold myself on it,” she said. “You can change the qualities of an individual glaze, but when you put two or three glazes on top of each other, they do unpredictable things.” She explores the push-pull between unpredictability and replicability. “I’ve found a sweet spot where I know in general what’s going to happen, but I can’t predict exactly.” Her work is sculptural and frequently multi-media; her installations have explored fragmenting human forms and creating surface textures that contemplate mortality. “I feel very much like a painter when I’m glazing,” West said. “I’m thinking about marble, but I want a fleshiness to show through so it’s more humanistic.”

AT THE DRIPPING EDGE OF EXPERIMENTAL TECHNIQUE: GLOOPS AND CLAZES

Ceramic artists are embracing the expressive and organic nature of their materials and processes, part of a movement sometimes called “action claying” that exploits the alchemy inside the kiln. Some are

26 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS ESSAY

WINTER / SPRING 2024 27 ESSAY

Toni Hafkenschied

David Harper, A Fear of Unknown Origin, 96” x 108”, Ceramic, glaze, 2012, Collection of the Museum of Wisconsin Art

28 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS ESSAY

Left: Scott Draves, 18”h x 8”w. Right: Scott Draves, three fainence cone 03 blend, 12”h x 5.5”w. Scott Draves

WINTER / SPRING 2024 29 ESSAY

Christina West, Untitled, 12”h x 20”w x 16”d, glazed porcelain, 2021.

Jason Houge

30 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS ESSAY

Morgan Baldinelli

Morgan Baldinelli, Giving In, 22” x 11” x 10”, Ceramic, 2022

WHERE WILL TOMORROW’S GLAZE-MAKERS LEARN THEIR CRAFT?

A journey down the rabbit hole of custom-made pigments and glazes leads to something akin to the extremes at the earth’s core, where intense heat applied to earth elements produces a magic array of rocks and minerals. One wonders what tomorrow’s ceramic artists will produce, and how they will learn their craft.

Draves, who teaches pottery through Madison School-Community Recreation (MSCR) and at Madison College, observed, “Everything used in ceramics is essentially broken-down rock. The first time students get their hands on that, they just love the feel of the material. Nine out of ten will want to try another class.” But will there be classes for them to enroll in?

using “gloop” glazes, a term coined to describe thick, viscous, unpredictable surface treatments, which represent a departure from the traditional, more controlled glazing techniques. Heat determines whether clay and glazes behave like solids, liquids, or even gasses. Gloop work is characterized by drips, dynamic textures, and vibrant colors. Artists are drawn to the serendipity inherent in a process that leaves so much to the kiln’s environment to complete.

One of West’s graduate students, Morgan Baldinelli, is part of this trend, creating clay bodies with voids that she fills with gloop, then suspends in the kiln so that drips pour from inside the pieces when the kiln reaches its highest temperature. “I’m personally fascinated with glazes and how surface texture occurs,” she said.

“The only thing connecting the two gray pieces is the gloop material. It took a bit to figure out how to suspend it in the kiln so that it would flow as I wanted.”

Ware was drawn to ceramics once he discovered the parallels between the ceramic process and certain geologic processes; in both, materials combine through heat, pressure, and time. Bringing that into his vision for his pieces, he said, “I’m not so much trying to replicate what forms look like but more so to bring out their energy.” Seeking to express energy with color, he began adding pigments to clay when he noticed the colors were even more vibrant than glazes.

Recently Ware has begun experimenting with the sculptural qualities of glazes. “I call it “claze” because it’s kind of a mixture of clay and glaze,” he said. “I play a lot with that boundary between the two. I try to create some parameters to then experiment within and solve problems.” In some of Ware’s work, he uses claze—and the kiln’s heat—to fuse in the kiln small individual elements built of clay to make larger sculptural pieces. In others, he buries claze in boxes filled with sand, and then excavates the resulting pieces after firing. “That came from my interest in geology,” he observed.

This trend in ceramic arts embraces spontaneity and the imperfections that arise in the creative process. It celebrates the unplanned and the unrestrained. It is only natural that counter-trends will emerge as they always have, pushing the boundaries in different directions. We may next see a deliberate move away from the exuberance of gloop glazes toward minimalist and refined aesthetics, where artists opt for cleaner lines and precise glazing techniques.

While teachers report that classes fill immediately, some schools and universities under pressure from tight finances have closed pottery teaching studios and even ended arts instruction entirely. At CVA-Wausau, Mullen said, “We’re lucky because we have wonderful arts educators within our school system. But I know that access to ceramics equipment and facilities isn’t the case elsewhere, especially in more rural areas. We try to spread what we do here as far into the state as we can.” Rural schools in central Wisconsin bring their students into Wausau for immersion days offered at the Center’s pottery studio.

The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction’s data indicates that student enrollment in ceramic arts programs declined from 32 percent in 2019 to 28 percent in 2021, while overall arts enrollment dropped by 10.7 percent in that timeframe. To lose more arts programs, especially in ceramics, would be a blow.

Ware observed, “Ceramics inherently creates communities because it’s hard to do alone. Filling and firing a kiln can be very laborious. Also, potters work long hours in a space shared with other people.” At a time when social isolation has been identified as a national health threat and young people are experiencing worsening mental health, arts programs offer a counter-balance. Kirkland said, “When I started teaching at Madison College, so many students told me, ‘This is like therapy.’”

But perhaps the most important reason to call for the continuation of arts education programs is the least tangible. “When students ask me what they can do with a ceramics degree,” Ware said, “I tell them, you’re qualified for everything and nothing. You are learning problem-solving skills, and those are invaluable throughout your life.”

WINTER / SPRING 2024 31 ESSAY

Sarah E. White is a freelance writer and personal historian. She helps people write about their lives and work from her home base in Madison.

Joanne Kirkland, 4”h x 3.5” w. The black glaze overlapping the tan glaze which has rutile in it causes tiny crystals to form and creates a visual texture or mottling.

Joanne Kirkland

32 WISCONSIN PEOPLE & IDEAS E SSAY

TruStage Financial Group’s new building on its west Madison campus earned LEED Gold certification, the second-highest designation from the U.S. Green Building Council.

SUSTAINABILITY INC.

WHEN FOR-PROFIT COMPANIES ADOPT SUSTAINABILITY AS A BUSINESS STRATEGY, INNOVATION CAN LEAD TO BETTER WORLDS AND BETTER BOTTOM LINES

BY KRISTINE HANSEN

Wisconsin’s long been a national leader in sustainability.

After all, former Gov. Gaylord Nelson founded Earth Day in 1970. And, in 1968, Madison became the first community in the country to offer curbside recycling. Today, the state ranks number two—only behind California—in its number of organic farms, and has pledged to generate 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2050. But even before this, Wisconsin’s landscape

birthed

many environmentalists, including Aldo Leopold, the author of “A Sand County Almanac,” who taught wildlife management at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the 1930s; and John Muir, who lived on a farm near Portage with his family as a child in the 1850s.

WINTER / SPRING 2024 33 E SSAY

“We have a long history of conservation and outdoor recreation in the state that supports employees and business leaders valuing our natural resources," says Jessy Servi Ortiz, managing director of Wisconsin Sustainable Business Council.

In recent years this sustainability mantra has expanded into the Wisconsin business sector, inching into industries as small and niche as a dental office and a coffee roaster, but also into a major hospital system, a clothing and lifestyle brand, and a manufacturer of boat parts. Whether it’s about adopting renewable energy, offsetting greenhouse gasses, recycling, or using post-consumer recycled materials, earth-friendly innovators are attracting the attention of both their employees and customers.

Organizations like the Wisconsin Sustainable Business Council foster community and conversation within the business sector so that there is a process for sharing both the positives and the pitfalls. One example is the Council’s Green Masters Program®, a virtual tool open to any business wanting to improve its sustainability. Businesses first measure their own performance and then benchmark themselves against the maturing field.

“The tool helps companies define, prioritize, measure and improve their sustainability performance through systems development, best practices and performance improvement,” says Jessy Servi Ortiz, managing director of Wisconsin Sustainable Business Council (WSBC).

Participating in the program entitles them to use the Green Masters Program logo in their marketing. At the Council’s annual conference, businesses convene to continue to learn and share best practices around mitigating risk around climate and improving their environmental and social performance.