CLM

COMMERCE, LAW AND MANAGEMENT

FACULTY OF COMMERCE, LAW & MANAGEMENT

EMAIL: kim.jurgensen@wits.ac.za

WEB: www.wits.ac.za

FACULTY OF COMMERCE, LAW & MANAGEMENT

EMAIL: kim.jurgensen@wits.ac.za

WEB: www.wits.ac.za

Professor Jason Cohen, Dean of the Faculty of Commerce, Law and Management at Wits, gives an introduction to the Faculty and all its Schools, Chairs, Institutes and Centres

WATCH NOW Full message:

It bears reminding that the preamble of this important document says:

We, the people of South Africa, Recognise the injustices of our past;

Honour those who suffered for justice and freedom in our land;

Respect those who have worked to build and develop our country; and

Believe that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity.

We therefore, through our freely elected representatives, adopt this Constitution as the supreme law of the Republic so as to -

At the end of 2023 we presented our communications strategy to the Faculty executive – our focus would be on 1) highlighting academic work under the four strategic areas of climate change, inequality and the economy, democracy and digital transformation (see here); 2) showcasing academic work on the 30 Years of Democracy and 3) encouraging staff to be more active in the media as a way of taking research into the public domain. As is the wont of all good plans, we soon found ourselves taking on a number of additional projects which included profiling female academics during Women’s Month, tracking students who have made an impact in the world, and recording some of the Faculty’s Research Chairs

Our Dean recently reminded us to come back to the question of why we do this work. For us it is about the mandate of the university, as a public institution, to be working towards building a better society and to addressing the myriad of challenges our world is suffering under. We believe in the importance of good communication to share this valuable knowledge and

the insights that come from intense research in particular areas. We want to influence the public discourse, and to allow policy makers and people in power to have access to the evidence that is produced in our Faculty.

Our journey to collate some of this work has been both informative and at times surprising. You will see in the video below an introduction to the CLM Faculty by our Dean. This will give you an idea of how complex and broad the Faculty is, which is what makes it such an interesting space to work in. It is these committed academics who have a profound impact on their students, influencing our curious, committed young people who go out into the world armed with excellent degrees which form the basis of their work in the world. Read for example how some of our alumni are thinking about the 30 Years of Democracy.

We have been excited to see how the work across our Faculty influences the national democratic project, how academics are thinking about 30 years of democracy in our country and connecting their research to the ideals laid out in our Constitution.

Heal the divisions of the past and establish a society based on democratic values, social justice and fundamental human rights;

Lay the foundations for a democratic and open society in which government is based on the will of the people and every citizen is equally protected by law;

Improve the quality of life of all citizens and free the potential of each person; and

Build a united and democratic South Africa able to take its rightful place as a sovereign state in the family of nations.

We felt strongly that, given the depth and quality of work being undertaken, it would be a good idea to collate some of what we have done into a magazine, where everyone can get a good idea of what is being done in the Faculty. Although this is only a snapshot of the work of the Faculty, it will give you a good idea of the interesting research, and the impact possibilities across our Schools and institutes. Although we are largely showcasing the work of our academic colleagues here, we continue to recognise the important work being done by the professional and administrative staff, which is more difficult to showcase. We realise that without the

work of PAS colleagues, the academics could not flourish as they do. We are hoping to showcase the “behind the scenes” work of PAS colleagues in future publications.

We hope you enjoy reading this magazine as much as we enjoyed producing it. We will continue to share the valuable work being done in our Faculty in the future.

Kim Jurgensen and Tholoana Phoshodi CLM Faculty Communications

The Mandela Institute was established in 2000 as a unit in the School of Law. The aim of the institute is to support the democratic project. It was recognised that, while 1994 marked the country’s political transition, economic transformation would be necessary to achieve socio-economic rights laid out in the Constitution’s Bill of Rights, and this requires a strong economy. The Mandela Institute strives to be a leading research institute in 1) Innovative law and policy research 2) Continuous professional development and capacity building and 3) Creating a space for public policy engagement.

We spoke to MI director, Professor Firoz Cachalia, about the work of the institute, and his own work in the anti-corruption council.

Q: What does the MI do?

A: We run about 30 short courses per semester, together with the Law School. We also have a research centre where we focus both on research and publishing in the legal field. But we also do a lot of interdisciplinary work. For example, we’ve been looking at platform companies and the issues they raise for democracy and competition policy. We’ve also started doing some work in the corruption space. In addition to that we have been working with the Electoral Commission of South Africa (IEC) to develop courses in electoral law that will support, electoral integrity. We are looking at expanding these courses to support other jurisdictions in our continent.

Q: What makes the MI important now, as we celebrate 30 years of democracy?

A: When the Mandela Institute was set up we wanted to ensure that black students were given the opportunity to develop their knowledge and skills in a number of areas of law, including commercial competition and trade law. The World Trade Organisation (WHO) had recently been established and we wanted to ensure that previously disadvantaged students could practice that kind of law, and do research in that area. It was a more optimistic time. Mandela wanted to support the response to globalisation, and there was a hope that this new world order would produce prosperity for everyone. We’re in a different time now – inequality is growing, there are greater geopolitical tensions and there is a lot of skepticism about trade liberalisation and globalisation. Democracies across the world appear more fragile now.

So the Mandela Institute can play a role in responding to this new situation through quality research, thinking about the rule of law in a rapidly changing world, and the role that law, lawyers and legal institutions play to address the concerns that have now emerged on climate change, inequality and so forth.

Q: Can you give us an example of how this is being done?

A: Recently were part of a law and economy workshop with a mixed group of people including academics and people from the public sector, to talk about the constitutional project. We were looking at questions about the relationship between the Constitution and the economic structure of the country, something that was not examined 30 years ago. This is where research becomes valuable, it can give insights into what mechanisms are necessary to realise the original intentions of the Constitution and to better understand why, 30 years later, we still have so many deep societal challenges.

Q: Does the MI do any work in the social justice area?

A: Yes! We are currently doing some research for the legal team that is before the International Court of Justice (on the issue of the war in Palestine). This is a very exciting project for us. International law has emerged as an important field of research for South Africa and global community as it raises issues about justice, the rule of law and the worlds response to an unfolding genocide. All of these questions relate to the role both of lawyers and of legal research institutions.

Q: You are also doing work in the anticorruption space. Can you tell us more about that?

A: chair the Anti-Corruption Advisory Council which was established by the President. The Council is looking at ways to implement the anti-corruption strategy which was adopted by Cabinet in about 2022. This is an “allgovernment-all-society” approach. The fight against corruption is currently focused on law enforcement and the role of the NPA and other investigative bodies. But I believe there are broader societal and institutional questions to be addressed. We have to look at how to prevent corruption as much as we have to deal with the corruption we already have. This includes all spheres of society. For example, we need to start educating our children from a young age about being moral corruptionfree citizens. This is something the Department of Education, schools, teachers and parents all need to work on.

Q: Is the Council dealing with the recommendations from the Zondo Commission report?

A: Yes, we are advising the President on how to implement the recommendations. This is a very big and complex task. So far we have submitted four advisories. We have looked at issues from political party funding to procurement legislation. We conducted a lot of research on the issue of Procurement – how it is structured and how it is legislated. I think the last ten years has shown us that this is one of the main areas we have to deal with.

Q: What other work has the Council been doing?

A: In our mid-term report earlier this year, we recommended that a new constitutional body be established, which we are calling the Office of Public Integrity. This body should have an ongoing role in dealing not just with corruption issues (such as improved law enforcement) but also in the prevention of systemic corruption. This body will have the powers to go into institutions like government departments, local authorities and hospitals, to look at their systems and audit their procedures (including their procurement systems) to identify proactively if there is a corruption risk, and where risks are identified, the Office will make proposals for corrective action. The idea is that this body will have both preventative auditing functions, but also investigative functions and will work under the supervision of the National Prosecuting Authority.

Q: Is the Council drawing on the work of other similar bodies across the world?

A: We believe it is important to look at the specific conditions of our own country and how corruption has manifested here. This allows us to design solutions which are both appropriate and specific to South Africa, so they are responding to our unique challenges. We have not taken a “copy and paste” approach or done a best practice analysis of other jurisdictions, because we believe each country has specific and unique characteristics which require tailor-made solutions. We’ve looked carefully at the South African situation: how corruption manifests itself here, what the resource possibilities and constraints are, what interventions already exist, and then determined how this new institution would fit into the arrangements that are already in place. We are very proud that this is a South African solution to a South African problem.

DR THOMAS COGGIN School of Law

Have you ever noticed the recyclers on your street sorting through material in your garbage bin? According to a report published in 2016 by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (Godfrey, Strydom & Phukubye, 2016), it was estimated that there were between 60,000 and 90,000 recyclers in South Africa (Id: 2). The study concluded that informal recyclers have saved municipalities between R310-million and R748-million in budgetary expenditure (Id: 5).

Clearly, recyclers are an integral component of South Africa’s recycling system, but it is not entirely clear whether recyclers are compensated as fully as they should be considering their contribution to the sustainability of the urban and spatial environment.

Recyclers are one category of informal workers canvassed in the recently published Mapping Legalities:

Law, Urbanisation and Informal Work (2024). The edited volume brought together over 28 authors covering 25 cities across the world. The preface to the project was that informal workers are key enablers in urban growth, but the benefits of urban growth do not necessarily transfer to informal workers, as they are often invisible to lawmakers.

As such, informal workers tend to remain at the policy and legal margins of urban society, constantly struggling to gain social benefits and legal protections. This is all the more difficult because, unlike within the more private legal domain between an employer and employee, there is a far more public element here: collectively, informal workers serve the broader needs of urban societies, and so it is important to unpack the developmental responsibility of both local law and policy to support and protect workers in the informal economy – which is, in essence, a core component of an urban economy.

What might this approach like? At a minimum, the approach would require an enabling legislative and policy environment, one that is cognisant of the type of work people do, the conditions under which it takes place, and how this work is discerned ‘on the ground’ by local agents

of the law. For example, Bamu & Marchiori (2024: 46-72) note in their chapter on laws affecting street vendor livelihoods in Accra and Dakar that the disconnect between ‘lawon-the-books’ and ‘law-on-the-ground’ means vendors are left to interpret their legal reality. This obtuse status quo means vendors begin to perceive their work as inherently contrary to legal and social norms – even if this is not the case.

But even progressive laws may suffer from ad hoc implementation. In the context of the contemporary, global city, informal workers are often presented as inimical to the modernisation of the city. Singh & Yadav (2024: 85-106) in their chapter on the implementation of the Street Vendor Act in Delhi, note that the anesthetization of cities and the hosting of big events, such as the Commonwealth Games, bring about a complete deprivation and disruption of entire economic livelihoods in favour of an aesthetically modern city. This occurs despite the presence of an affirming law.

A ’clean’ image of the city impacts other informal works too. Neethi P & Kamath (2024: 141-158) focus on sex worker livelihoods in Bangalore. They argued that through efforts to push the city as a ‘world-class city’, an erosion and modification of distinct worksites occurred, corroding the livelihoods of sex workers in addition to criminalising them. In the process, law and policy treats sex workers as ‘pseudo-invisibles’, a state of being in which access to physical space is made tenuous by the ‘cleaning’ of this space by both the state and ‘decent/respectable’ citizenry.

This invisibility is present also in the instance of off-grid sanitation workers, such as manual latrine emptiers, whose work requires them to remove faecal sludge from deep latrines. This is a key function of urban life in many cities around the world. The experiences of offgrid sanitation workers in Beira, Freetown, and Mwanza formed the backdrop of a chapter by Walker, Allen and the OVERDUE team (2024: 205-228). Their analysis highlights how formal law-based rules reveal a bias towards ‘modern’ sanitation systems, even when these systems may not prevalent in reality. Consequently, these rules serve to over-regulate and exclude off-grid paid sanitation workers, making their livelihoods both ‘undecent’ and reinforcing their invisibility and lack of protection.

The book also examined other categories of informal workers, such as domestic workers and gig-economy workers. It became evident from the chapters that while informal workers meet the needs of the city and its residents, laws and policies, along with their enforcement, often marginalise them and fail to provide decent work benefits. However, the chapters also highlighted how informal workers use the law to assert their right to the city and its spaces, affirming their presence within urban society. Informal workers deserve recognition as key contributors to the vitality, sustainability, and functioning of the urban environment, and enabling laws and policies— along with proper implementation—are essential to this recognition.

Godfrey, L, W Strydom, & R Phukubye ‘Integrating the Informal Sector into the South African Waste and Recycling Economy in the Context of Extended Producer Responsibility’ (20215) CSIR Briefing Note 1

Marchiori, T & P Bamu ‘Power dynamics and the regulation of street vending in the urban space: The law on the books and the law on the ground in Accra and Dakar’ in Coggin & Madhav (eds.) Mapping Legalities: Law, Urbanisation and Informal Work (2024) 46-72.

Singh, A. & R Yadav ‘Local government regulations and the dispossession of urban informal vendors in Delhi, India’ in Coggin & Madhav (eds.) Mapping Legalities: Law, Urbanisation and Informal Work (2024) 85-106

Neethi P & Kamath, A ‘Turbulent transformations and urban undesirables: Revanchist urban transition and street-based sex work in Bangalore’ in Coggin & Madhav (eds.) Mapping Legalities: Law, Urbanisation and Informal Work (2024) 141-158.

Walker, J, A Allen, IB Bangura, P Hofmann, W Kombe, N Leblond, T Limbumba, CSM Magaia, C Vouhe & J Wesely ‘Pursuing aspirations for decent sanitation work: How informal workers navigate the universe of rules that shape sanitation practices in urban Africa’ in Coggin & Madhav (eds.) Mapping Legalities: Law, Urbanisation and Informal Work (2024) 205-228.

As South Africa marks three decades of democracy in 2024, it is fitting to reflect on the transformative journey our nation has undergone since the fall of apartheid. The book I recently co-authored with Professor Roxan Laubscher, “Landmark Constitutional Cases that Changed South Africa”, serves as both a celebration of this milestone and a critical examination of the constitutional bedrock upon which our democracy stands.

Our work encapsulates the spirit of South Africa’s democratic transition by delving into ten landmark cases that have shaped the country’s legal and social landscape. These cases, carefully selected for their profound impact and enduring significance, represent the living, breathing manifestation of our Constitution—a document that has been hailed as one of the most progressive in the world.

The inspiration for our book stemmed from a desire to illuminate the transformative power of constitutional law in reshaping South African society. By examining these landmark cases, we sought to craft a compelling narrative that illustrates how the Constitutional Court has given life to the values enshrined in our post-apartheid Constitution. This approach not only allows us to analyse legal principles but also to trace the ripple effects of these judgments on the fabric of South African life.

Our selection criteria for the cases balanced legal significance with broader societal impact. We considered factors such as the novelty of legal reasoning, the clarity of the Court’s articulation, and the enduring influence of each decision. In doing so, we aimed to curate a collection that truly represents the pillars of South African constitutional jurisprudence—cases that not only set new legal precedents but also resonate deeply with public consciousness.

One of the key objectives in writing this book was to make the often-complex world of constitutional law accessible to a broader audience. We achieved this by providing historical context, explaining legal principles in relatable terms, and highlighting the real-world implications of each judgment. This approach opens up the world of constitutional law to general readers, allowing them to appreciate the profound impact these decisions have had on their daily lives and the overall trajectory of our nation.

As we celebrate 30 years of democracy, it is crucial to recognise the role that the Constitutional Court has played in upholding and advancing the values enshrined in our Constitution. The Court has been instrumental in addressing the injustices of the past, protecting individual rights, and promoting equality and human dignity. Through our analysis of these landmark cases, we demonstrate how the Court has consistently risen to the challenge of interpreting and applying the Constitution in a manner that promotes social justice and strengthens democratic institutions.

Looking ahead to the next decade, we anticipate that the role of the Constitutional Court will continue to evolve in response to emerging challenges and opportunities. The Court will need to navigate the delicate balance between judicial restraint and its transformative mandate, particularly when addressing systemic inequality and socio-economic rights. Additionally, it will likely play a pivotal role in addressing issues such as corruption, state capture, the rise of Artificial Intelligence, and environmental sustainability.

We recognise that there are areas of constitutional law that require further attention and reform. The ongoing challenge of realising socio-economic rights, the need to refine approaches to equality and unfair discrimination, and emerging issues like data privacy rights all present opportunities for further development of our constitutional jurisprudence.

In light of this, we are excited about the prospect of a second edition of our book. We have invited scholars specialising in mercantile law and private law to contribute, emphasising the far-reaching effects of the South African Constitution on the country’s law and society at large. New themes to be explored include freedom of religion and aspects of corporate and private law, further broadening the scope of our analysis and reflection on the impact of our Constitution.

As we commemorate 30 years of democracy, our book serves as a testament to the progress we have made as a nation. It highlights how the Constitutional Court has been a beacon of hope, consistently upholding the values of human dignity, equality, and freedom that form the cornerstone of our democracy. Through our analysis of these landmark cases, we demonstrate how constitutional law has been a powerful tool for social change, addressing the injustices of the past and paving the way for a more equitable future.

In conclusion, “Landmark Constitutional Cases that Changed South Africa” is more than just a legal text; it is a celebration of our nation’s journey towards justice and equality. It serves as a reminder of the power of law to effect positive change and the importance of upholding constitutional values in the face of ongoing challenges. As we look to the future, we hope that our work will inspire continued engagement with constitutional principles and foster a deeper appreciation for the role of the law in shaping a just and democratic society. In this way, our book not only commemorates 30 years of democracy but also contributes to the ongoing dialogue about the future of our nation and the enduring relevance of our Constitution.

DR CHRISTINE HOBDEN

Wits School of Governance

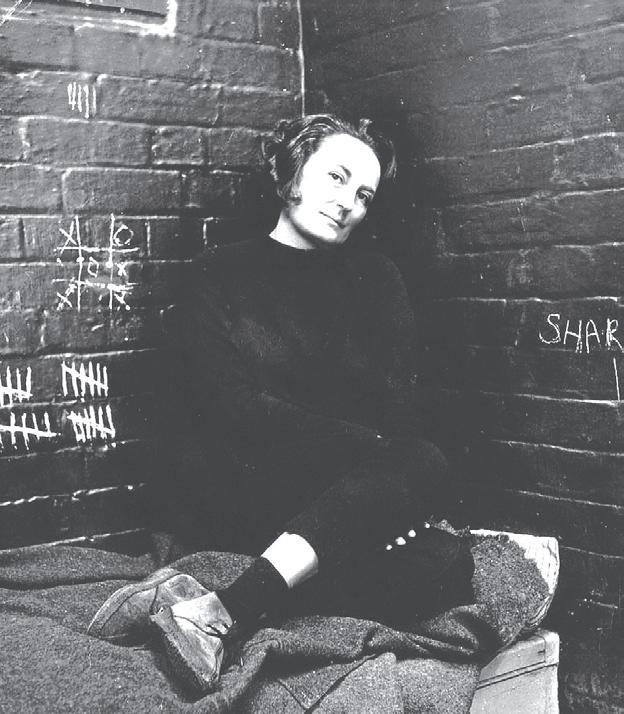

Linked to publication of “Rick Turner’s Politics as the Art of the Impossible” (Wits University Press, 2024), Chapter 11 Rick Turner and the Vision of Engaged Political Philosophy

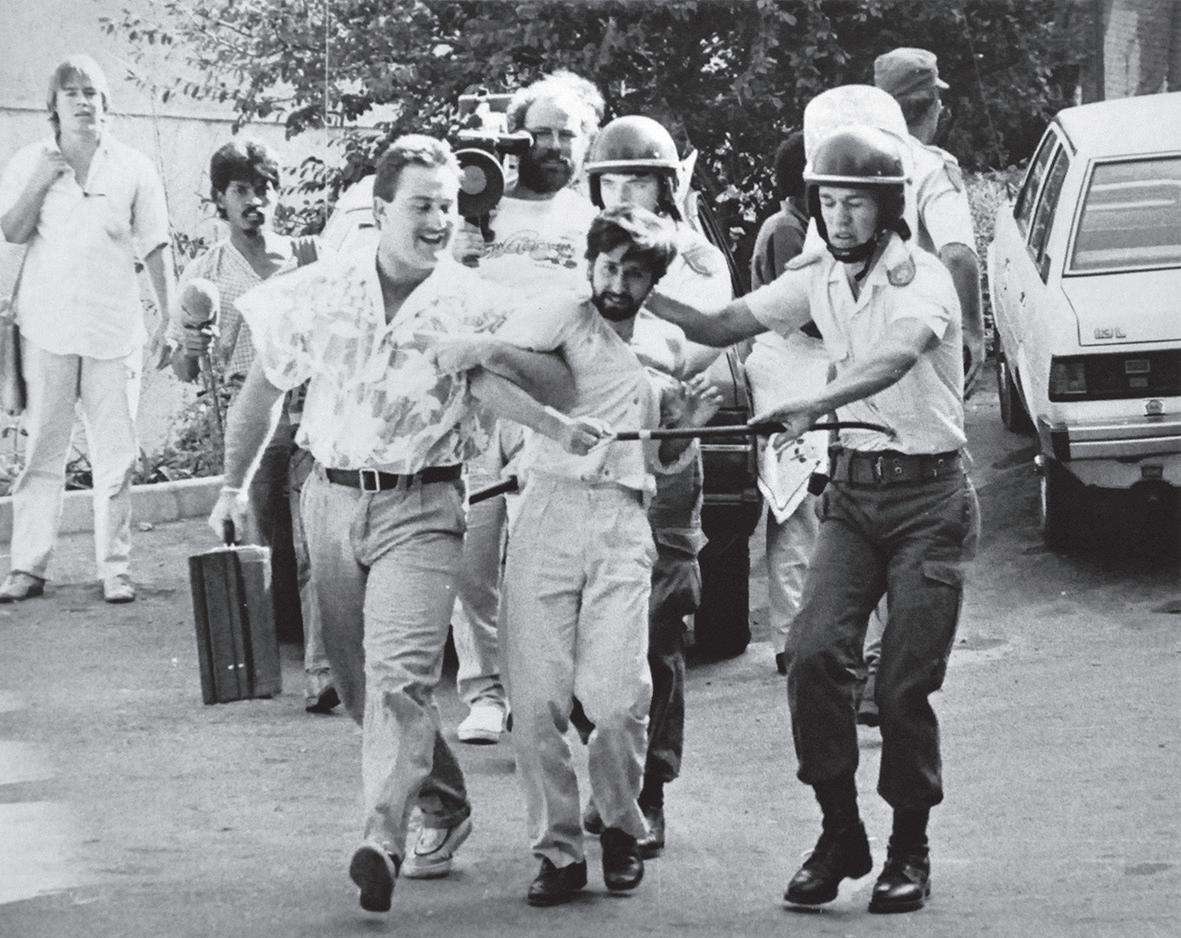

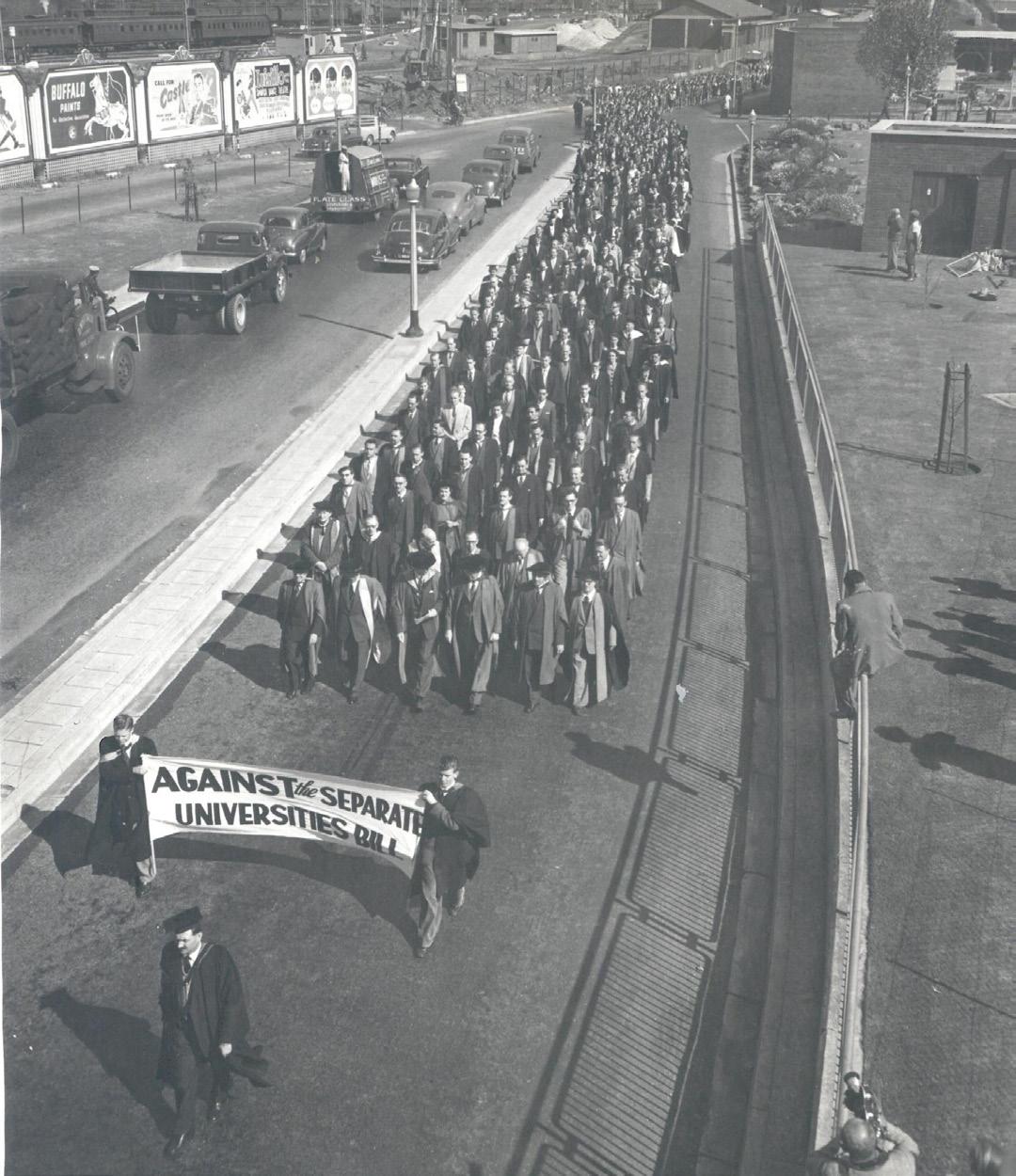

Ifirst encountered Rick Turner as a name on a building, the University of KwaZulu-Natal Student Union building I visited for practice as a high school debater, some many years ago. Long after this I returned to his work as a lecturer at Fort Hare thinking through the pressing question of the time: in what ways, if at all, is political philosophy relevant to the students sitting in my class? Most recently, I have contributed a chapter, “Rick Turner and the Vision of Engaged Political Philosophy” to the newly published “Rick Turner’s Politics as the Art of the Impossible” (Wits University Press). What is it about the life and ideas of Rick Turner that, 30 years into democracy, still challenge and inspire me?

Turner was a political philosopher and anti-apartheid activist, most active from the late 1960s when he returned to South Africa after completing a PhD at the Sorbornne, until his assassination in early 1978. In 1972 Turner published “The Eye of the Needle: Towards Participatory Democracy in South Africa” (SPRO-CAS). The opening chapter of this book was titled, “The Necessity of Utopian Thinking”. It is these few pages, written in a context of a deeply oppressive and unjust Apartheid regime, that are a great resource to ground critical conversations with students grappling with the relevance of theoretical ideas. What is the value of engaging with ideas of how we ought to live justly together in society, if one’s deeply experienced sense is that these ideas are out of reach?

In my contribution to the collective volume, I deepen my exploration of this chapter alongside another article, “What is Political Philosophy?” (1968) and develop a Turner-inspired method of ‘engaged political philosophy’. This approach to theorising is both rooted deeply in context and ambitious in what society it imagines. Foundational to this approach is Turner’s argument for the value, and even necessity, of utopian thought, an argument that can resonate beyond the confines of our shared discipline of political philosophy and that animates the range of critical engagements in “Rick Turner’s Politics as the Art of the Impossible”.

Turner invites us to notice that we all too often fail to distinguish between absolute impossibility and other-things-being-equal impossibility. It is absolutely impossible for a lion to become a vegetarian, but, he argued in 1972, it is not absolutely impossible for a black person to become the Prime Minister of South Africa; it is other-things-being-equal impossible. A key question that we often fail to ask is do other things have to remain equal? Turner argues that we treat our social and political institutions as if they are naturally occurring mountains around which we have to maneuver, rather than a set of behavioural patterns that we (at least potentially) have the power to change: in other words, we implicitly assume the answer to the question is that other things remain equal.

Turner argues that while institutions might have some material features like writtendown rules or buildings that house them, ultimately, our institutions are formed and maintained in the way we collectively behave toward one another, and ultimately our collective behaviour is changeable.

For Turner, the value of utopian thinking is that it allows us to examine our institutions in comparison to other possible versions and so begin to truly evaluate our social and political arrangements. In doing this comparison we have the tools to identify the assumptions underpinning our society and to identify what about our society really is unchangeable and what is, upon closer examination, possible to change. In this way, we also step back and notice that the ‘present is history’; while change often doesn’t feel possible within our own experience of society, over the course of history significant change has happened. Consciously situating our society within this wider history encourages us to be much bolder in our vision and demands for change. Political philosophy that develops normative visions of the ideal society is not just about defining the end goal, nor is it chiefly about developing a detailed map towards that goal – for Turner it is a consciousness-raising activity, and the product, our vision of an ideal society, serves as a tool to critically engage in the present.

In The Eye of the Needle, Turner was addressing white liberals at the time, and his choice of example is confronting to us in how accurate he turned out to be; 30 years into democracy, it can be hard to imagine that even some of those who committedly resisted the Apartheid regime did not see a black Prime Minister as a viable political goal. Particularly to those in positions of privilege, Turner challenges us to not confine our imaginations or activism to the small wins that seem possible in the short term, but to notice that imagining a radically different future has power in itself. Not only can it be a powerful source of collective hope, but it can also lay the foundations for those surprising moments when after long, slow and incremental change, a more radical opportunity for change emerges.

MATLALA SETLHALOGILE Wits School of Governance

As South Africa marks thirty years of democracy, the quest for liberation still rages on. The democratic project has failed to satisfy the aspirations of many a South African. While there may have never been any set timelines for the liberation of the historically disadvantaged, there is little doubt that the pace with which the attempts to reconcile democratic governance with socioeconomic transformation has been lacklustre.

Thirty years into democracy, South Africa remains a country marked by an eclectic array of fault-lines – with the most glaring of these being the ones rooted in the economic realities of many South Africans. While some strides have been made, multidimensional inequality, high rates of poverty and alarming rates of employment continue to be ineliminable features of the democratic South Africa.

More than two decades later, Thabo Mbeki’s 2003 idea of South Africa being a country of two economies or a country with parallel economies still aptly captures the essence of South. Whilst this may be the case, the value of that idea lies more in its emblematic nature rather than its academic usefulness. This is because the idea was based on feeble academic assumptions about the existence of disjuncture between the formal and informal economies.

Be that is it may, these remarks served as a stark reminder of the varied lived experiences of South Africans. There is no single state of the nation, but a multitude of disaggregated experiences. With this comes the disintegration of interests as typified by the pervasive political fragmentation that has seemingly entrenched itself since the 2016 Local Government Elections.

Concomitant to the emergent political fragmentation has been grievance politics that have reshaped South Africa’s political landscape post the 2024 General Elections. These two phenomena are two sides of the same coin as they tend to be mutually reinforcing. Moreover, these have been underpinned by the brewing disillusionment with the democratic order and its institutions - exemplified by several studies detailing the decline in trust in public institutions.

These developments, it could be argued, are rooted in the inability of democracy to address the pressing socioeconomic challenges confronting many South Africans. With rampant inequalities, the unemployment rate sitting comfortably above 30 per cent and more than half of South Africans living below the upper

bound poverty line, democracy is beginning to seem not to be synonymous with favourable socioeconomic transformation – at least to may South Africans.

As a result, satisfaction with democracy has been on a steady decline over the past two decades – with more than of South Africa being dissatisfied with democracy. A survey conducted by Afrobarometer in August 2021 found that at least 67 per cent of South Africans were willing to forego elections if an alternative non-elected government could deliver on the provision of jobs, housing and security. This intimates that democracy has become a secondary concern to many – at least in its current form.

This could be, in part, credited to the skewed focus on proceduralising democracy – like in many parts across the globe. What this means is that the concept of democracy has been narrowly characterised around the electoral sphere. Democracy has simply been reduced to multiparty politics, processes, procedures and decisions around elections. This has unfortunately been at the expense of the substance of democracy.

This has mostly been by default rather than by design in the South African context. This is so because it could be argued that this calamity is as a result of a combination of factors such as subpar policy thinking and the dismal capabilities of the democratic state. Even though this might be the case, the inability of democratic state to address the substantive problems remains.

Consequently, the policy incoherence and policy paralysis that underpin most of the failures of the state have betrayed the promises of the liberation struggle. After all, the liberation struggle was never merely about a hollow democracy, but also the substantive elements of democracy. This is because democracy should go beyond merely universal franchise and incorporate a favourable socioeconomic environment, economic equity and social justice among others.

Social justice is the cornerstone of any substantive democracy. Activities of any government should seek to ensure that the least advantaged in society benefit from its activities. Democracy has to be about ensuring that the activities and actions of government align with the wishes of South Africans. In essence, democracy ought to be evident between elections - and not limited to the electoral sphere and superficial freedoms.

There needs to be a shift in how democracy is conceptualised and actualised in South Africa. The constraints that hinder the transition to a more substantive democracy require immediate attention. Enhanced state capabilities, innovative policy thinking and unwavering political will need to be the order of the day lest we seek to fan the growing dissatisfaction with democracy, institutionalise the emerging grievance politics and undermine the modest democratic gains since 1994.

THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES, VICTORY IS CERTAIN.’

*Setlhalogile is a lecturer at the Wits School of Governance and a political analyst. He writes in his personal capacity.

JANE NDLOVU

School of Accountancy

South Africa’s Constitution opens with the inspiring words: “We, the people of South Africa... believe that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity.” These words reflect our nation’s deep commitment to equality, inclusivity, and community—principles that have shaped our democracy and its policies over the last 30 years. One such policy is the retirement system, which has seen significant transformation as the country seeks to provide every citizen with financial security. The journey from a single-pot system to the two-pot structure we have today represents an ongoing commitment to ensuring that all South Africans, regardless of income or employment status, can retire with dignity.

Commonly referred to as the “three-pot system,” the formal name is actually the “two-pot system,” as not everyone, especially those who are unemployed, has access to a vested pot. This exclusion highlights one of the primary challenges facing the current system—its inability to provide comprehensive coverage to all citizens. For many, informal savings mechanisms like stokvels and burial societies fill this gap. These community-driven savings options, rooted in the spirit of Ubuntu, offer a level of support that the formal system has yet to fully address.

A familiar symbol in South African culture is the potjie—a three-legged cooking pot known for its stability, endurance, and the sense of community it evokes. Similarly, the two-pot system aims to provide a more secure and structured retirement framework by building on three critical components: the savings pot, the preservation

pot, and, for those fortunate enough, the vested pot.

Much like cooking a potjie meal, the expedition to a secure retirement requires careful preparation, layering of savings, and above all, patience. However, despite the system’s potential, the issue of leakage continues to undermine the long-term financial security of many South Africans.

Leakage, which occurs when individuals withdraw their retirement savings early—typically when changing jobs or facing unemployment—remains a persistent problem. Rather than reinvesting these funds, many South Africans use them to address immediate financial needs, which ultimately diminishes their retirement prospects. This challenge is one of the key reasons why so many retirees find themselves financially vulnerable.

Reflecting on the history of retirement reform reveals the progress that has been made, but also the gaps that remain. Taxation on retirement funds, for example, underwent significant changes over the years. In 1996, the government introduced a tax on the interest and rental income of retirement funds at a rate of 17%. This rate increased to 25% in 1999 before being reduced to 9% in 2006 and ultimately abolished in 2007. These reforms, along with the transition to an EET (Exempt, Exempt, Taxed) model, aimed to incentivise savings by easing the tax burden on contributions and investment growth. The

focus was on encouraging long-term savings, especially for those previously excluded from the system.

Further reforms in 2023 expanded these efforts, increasing the tax-free amount on lump-sum payouts and offering more flexibility for retirees in managing their withdrawals. These changes aligned with South Africa’s democratic ideals by extending financial planning tools to a broader segment of the population. However, as with many reforms, their benefits have yet to reach all corners of society, particularly the informal sector.

The government’s social security system, while a vital safety net, also highlights the ongoing challenges. The old-age pension of R2 180 per month provides essential support for many elderly South Africans, but it falls short of delivering a truly dignified retirement. The reality is that for most, especially those in the informal economy, the dream of financial independence in old age remains elusive.

Ubuntu, which translates to “I am because we are,” is at the heart of South Africa’s identity. This philosophy of collective responsibility and community should be reflected in our retirement policies, yet the current system falls short. By excluding those in the informal economy or those without formal employment, it overlooks the very people who could benefit most from structured financial security. Many individuals in these sectors turn to stokvels and societies—informal, community-driven solutions that embody the spirit of Ubuntu. A truly inclusive retirement system would find ways to integrate these informal mechanisms, ensuring that no one is left behind.

Looking ahead, it is clear that the two-pot system, while promising, is still in its infancy and requires further development to address the challenges of leakage and exclusion. Policymakers need to focus on bringing informal workers into the fold, possibly by recognising contributions made through stokvels or similar savings groups. Moreover, ongoing education about the importance of long-term savings is crucial.

Many South Africans prioritise day-to-day survival over retirement planning, and without the right support and knowledge, the benefits of the two-pot system may never be fully realised.

The introduction of the two-pot system is a reminder that financial security is a cornerstone of true freedom. Our journey toward economic empowerment is not complete. By promoting a culture of savings, investing in financial education, and ensuring that these reforms reach all South Africans, we can make significant strides in the next 30 years. After all, democracy is not just about the right to vote—it is about ensuring a secure, dignified future for every citizen.

PROF WAYNE VAN ZIJL School of Accountancy

Many of us make minor financial investments without much research or continuous monitoring. But, when we need to make large and significant investments, we conduct our due diligence by researching our options so we make the best decision. Once we’ve made our investment, we also continuously monitor that investment. Isn’t democracy, and choosing who will govern the country, one of the most significant investments we make as citizens? If so, are we treating it accordingly?

At first glance, accounting and democracy may seem unrelated. However, Jacob Soll’s book, “The Reckoning”, reveals their vital connection. Reliable accounting is essential for effective governance and accountability in a healthy democracy. This is because democracy involves delegating the responsibility of governing society to elected representatives. Whenever authority is delegated, there is a risk that those representatives may act in their own interests rather than the interests of the people they serve. Additionally, they might simply underperform.

To prevent these risks from materializing into problems like corruption, greed, or incompetence, continuous monitoring of their accounts is essential. Accounting, as a discipline based on standardized rules and principles to summarise information, plays a key role in facilitating this monitoring. It provides the information necessary to assess past actions and evaluate the performance of our elected officials.

Every year, the government and its departments publish reports detailing their activities and performance across various sectors ranging from financial data to crime statistics, health services, home affairs, and defense. If citizens aren’t monitoring these reports, then how can they gauge whether democracy is functioning as it should? Moreover, if no one is scrutinizing these reports, what incentive do government departments have to ensure their reports are accurate and complete? This can lead to a dangerous downward spiral. But, can we really blame citizens for not engaging with these reports if they were never provided with the skills to access, understand and then take action based on them?

An informed citizenry is better equipped to challenge unclear or inadequate explanations when they understand both financial and non-financial reports from the government. Such understanding allows citizens to seek evidence that either supports or contradicts official claims. It also helps them make better-informed decisions about which political party’s policies align with their views based on the country’s current conditions.

Without a solid grasp of South Africa’s political and governmental systems, and the ability to critically evaluate reports, citizens may struggle to make informed choices. This lack of knowledge can lead to complacency, where voters only participate in elections out of convenience or out of loyalty to family voting traditions, rather than through active and informed engagement.

As we celebrate 30 years of democracy, now is the perfect time to consider how we want the next 30 years to unfold. I have two key suggestions.

Educate Our Youth: We must ensure that young people are formally educated about how our government and political systems function. This should include a study of key political parties, their history, performance, and possible future trajectories. Additionally, students need to develop the skills required to access, understand, and evaluate the financial and non-financial reports issued by government institutions each year.

Promote Active Participation: It’s essential to instill in our youth the importance of being active participants in our democracy. We need to teach them how to engage meaningfully in the democratic process—not just by voting but by holding elected officials accountable in between elections.

Taking these steps will help South Africa strengthen its democracy, unlock its full potential and take its place as the gateway to Africa.

*AI was used to improve the readability and flow of this article

DR NOMALANGA MASHININI School of Law

Freedom of expression lies at the heart of South Africa’s constitutional state. In this 30th year of democracy, it is apparent that the primary platform for the public to enjoy their freedom of expression is social media. Social media entails mass sharing of people’s identity traits, such as real names, faces, and likenesses, through photographs, voice and video recordings. Social networking sites have reshaped the relationship between media producers and consumers. Consumers produce media from the comfort of their homes, giving rise to influencers, memes, catfish and deepfakes generated with artificial intelligence (AI).

AI and social media industries thrive in an image-centred world. The convergence of AI and social media puts ordinary people at risk of disinformation, manipulation, and fraud through deepfakes. Deepfakes can be produced by

scraping images and audio on the internet to generate fictitious photographs, videos, and voice recordings of people without their permission. If permission is granted, deepfakes can be used positively in entertainment and digital art. However, unauthorised deepfakes perpetuate identity misappropriation and publication to manipulate and commercially exploit people’s identities. Celebrities are the most common victims of unlawful deepfakes, but the public suffers too.

Recently, fake advertisements on social media depicted celebrities endorsing a financial services provider for unrealistic returns on investments. Investors in South Africa lost millions in the deepfake scam, while the celebrities’ reputations suffered scrutiny. As such, a nuance of image rights violations has emerged, entangled with crimes and other injustices such as fraud and forgery.

The term ‘image rights’ refers to the legally protected interests in the public expression and commercial exploitation of one’s personality. Image rights protect a person’s likeness, name, photographs and voice. However, the list is not exhaustive.

There are several ways in which AI and social media collide with image rights, but three common examples are noteworthy:

1. Image-based sexual abuse (IBSA) can occur where a person’s face is superimposed on pornographic material to humiliate them. Nudist apps perpetuate IBSA by allowing users to undress people’s images digitally. IBSA can overlap with cyber extortion, where a person is blackmailed to pay a sum of money to prevent the publication of fake nude pictures of themselves. Related to IBSA is child sexual abuse material (CSAM). CSAM can also be produced through deepfakes using AI-generated images of non-existent children.

2. Manipulation of elections through false endorsement deepfakes. Deepfake videos and audio portraying public figures can be used to influence voters’ decisions. In other instances, deepfakes can be used in real-time video conferencing, where scammers can impersonate politicians and prominent figures to manipulate unsuspecting members of the public.

3. Deceased person’s deepfakes can be purchased by grieving persons to create moments with their loved ones as if they were still alive. These deepfakes are often produced in voice and video formats to simulate a video call between the mourner and the deceased. Such deepfakes can potentially delay the grieving process, although they have been viewed as therapeutic for those who use them.

The three examples above introduce new legal questions and challenge societal norms important for a democratic state founded on equality, freedom of expression, and human dignity. For instance, it is questionable whether fake revenge pornography is the correct legal term to use when describing instances of IBSA. Questions arise as to whether CSAM is truly abuse in a technical legal sense if no children were hurt in the making of that material. The possibility for post-mortem protection of the personality interests of deceased persons is increasingly becoming relevant. Lastly, election fairness and reliability face a critical threat at the heart of democracy, as the truth can be distorted to manipulate the public. It is crucial to consider the influence of image rights protection to address these emerging nuanced problems.

Image rights are protected under the right to identity in the common law of delict and personality rights under South African law. In the pre-constitutional era, the right to identity was conflated with privacy. The misappropriation of identity was treated as an injury to dignity, which comprised one’s privacy, good feelings, reputation and identity.

It was only a decade after the incoming of the Constitution when the Supreme Court of Appeal, in Grütter v Lombard [2007] 3 All SA 311 (SCA), recognised the right to identity as an independent subjective right deserving protection under the common law of delict and personality rights. Since then, South African courts have grappled with protecting image rights in the context of the unauthorised use of identity in a magazine cover, a flyer advertisement, and a newspaper caricature. All other identity misappropriations have been addressed under the right to privacy. Based on these traditional media cases, the position is clear that the right to identity is distinct from the right to privacy, although their violation sometimes overlaps. Nevertheless, we have legal certainty that image rights are violated when one’s identity is used without permission to create a false impression of them or take commercial advantage of their identity. However, the new challenge for our courts is adapting the precedent to the nuances brought by AI and social mediadriven violations.

South Africa is not the only country grappling with emerging image rights issues. The impact of AI and social media on image rights is a global problem as geographical boundaries are blurred online. Adopting an internationally harmonised, socially, economically, and technologically advanced approach to protecting image rights is necessary.

Section 27(1)(c) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 provides everyone with the right to social security. This is a fundamental right aimed at ensuring that no one in South Africa lives beyond the poverty line. One of the social security tools used to prevent poverty, particularly during old age, is access to retirement funding through contributions to retirement funds.

Formal retirement funding in South Africa started in 1882. However, it was only after the discovery of gold and other minerals that led to the establishment of various mines in South Africa, that those employed in those mines were provided access to retirement funding.

Initially, retirement funding access was only provided to white employees. This led to mass struggle by the African workforce leading to the creation of militant trade unions that advocated for the rights of African workers to be granted access to retirement funding. In 1956, the first formal legislation that regulated retirement funds in South Africa was promulgated, the Pension Funds Act 24 of 1956. However, this legislation was wholly inadequate in several respects and did not regulate the affairs of employees who provided their services in the public sector. This led to the establishment of several publicsector retirement funds for public servants and those who worked for public enterprises such as Eskom.

Most public sector retirement funds established under the Apartheid government and the governments of several homelands collapsed in

1996. The Government Employees Pension Fund was established to provide retirement funding to employees who provided their services in the public sector. This fund is regulated by its own law, the Government Employees Pension Law (Proclamation 21 of 1996). Some of the public entities were not affected by this development. They also have their own retirement funds regulated by special legislation such as the Transnet Pension Fund Act 62 of 1990. This has resulted in the fragmented regulation of retirement funds in South Africa where different rules apply to different retirement funds.

There have been various challenges relating to retirement funding in South Africa. Among others, not every formally employed person in South Africa contributes towards retirement funding. For those who contribute, there has been a constant debate regarding their failure to adequately save to ensure self-sufficiency during old age.

Some retirement funds’ members outlive their retirement savings and are forced to rely on social grants during their old age. This defeats the purpose for which retirement funds are established. The government sought to intervene by introducing various measures to ensure that members save enough for their retirement. This was done through the compulsory annuitisation and preservation of retirement benefits.

Initially, there was a clear distinction between provident funds and pension funds. Provident fund members could take their retirement benefits as cash payments in full when they exited their funds through dismissal, resignation, retrenchment, and retirement. Pension fund members were forced to commute one-third of their retirement benefits and use the remaining twothirds to purchase annuities when they retired. The legal position has changed and all members, with certain exceptions,

PROF PRUDENCE MAGEJO, PROF MIRACLE BEHURA (SEF) AND DR GIBSON MUDIRIZA (UFS) School of Economics and Finance and UFS

Race-based discrimination still haunts job seekers 30 years post-apartheid! With pragmatism our research team comprising of Professors Kwenda, Ntuli and Dr Mudiriza enthusiastically unveils that post-apartheid South Africa’s staggering spatial unemployment disparities can be traced back to the insidious racial discrimination policies of the past, which promoted white supremacy.

Originating in the colonial era, race-based spatial segregations were enforced by the apartheid system which became forceful in 1948. One of the most infamous aspects was the creation of rural Bantustans - so-called ‘homelands’ for the black majority. These regions served to marginalise black South Africans from mainstream economic and political life. The coercing repressive policies trapped them in overcrowded, poverty-stricken communities devoid of the least acceptable education, physical infrastructure, economic and job opportunities. This had dire consequences! Many black South Africans were forced into temporary labour migration for employment opportunities in ‘white’ areas. However, movement was strictly controlled by pass-laws. Black South Africans were practically aliens in ‘white’ areas but were identified as citizens of homelands. The Bantu Self-Government Act of 1959 and the Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act of 1970 allowed the homelands to be independent self-governing units. That is, blacks were marginalised from the country’s mainstream socioeconomic and political systems as they were declared homeland citizens. They also received poor quality education, public services and infrastructure

than whites under the 1953 Bantu Education Act and the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act. Local unemployment was rife in homelands owing to nonexistent formal economic opportunities.

A new dawn? When democracy finally arrived in 1994 hopes were high as the apartheid system was abolished, and homelands were re-incorporated into South Africa’s nine provinces. This ushered South Africa into a new era of socio-economic transformation with several policies and programmes (e.g. Black Economic Empowerment, social grants, housing, education and public health policies) to reconstruct and transform the country. Was this enough? Spatial disparities in economic activities and well-being still saddle socioeconomic development in South Africa. While it is well known that Apartheid spatial policies severely underdeveloped former homeland areas, there is little evidence on the status of previously marginalised communities after their re-incorporation into the republic 25 years ago and government’s concerted efforts to redress past injustices. Our enquiry! Using cartographic data and 2011 Census community profiles, our research team strived to uncover factors underpinning the unemployment gap between former and non-former homeland areas. This sheds light into ongoing injustices faced by former-homeland areas.

Our focus on unemployment is important given the country’s high unemployment rate by global standards. In 2018, the official unemployment rate soared to a staggering 27 percent—far exceeding other African nations like Kenya (9.3%), Zambia (7.2%), Nigeria

(6%), and Egypt (11.4%). Even compared to its BRICS counterparts, South Africa’s job crisis is alarming: Brazil sits at 12.5%, while Russia (4.7%), China (4.4%), and India (2.6%) fare much better. This is not just a statistic!

The seriousness of joblessness in South Africa has situated a need for its reduction in the country’s long-term development plan - National Development Plan 2030. This is in order as unemployment has devastating effects on economic well-being of the unemployed, production and human capital. It also fuels social exclusion, crime and social instability in the country. Consequently, the persistence of these spatial inequalities is worrisome given post-apartheid policies and strategies aimed at redressing past imbalances. Is it just on the surface!

Such persistence possibly reflects a superficial erasure of former homeland areas as administrative units but not a re-configuration of their structural elements such as composition and ingrained disadvantage. This implies that official removal of former homeland areas designation per-se without commensurate interventions targeted at addressing underlying disadvantages is insufficient for socio-economic transformation. Empirical evidence shows that the past structural elements – such as low economic activity - persist despite the administrative changes. Consequently, we assess differences in unemployment rates between former and non-former homeland areas in South Africa.

Research finds a disturbing trend! The present assessment reveals stark differences in unemployment

rates between former and non-former homeland areas. Former homelands suffer from an alarming 24-percentage point higher unemployment rate than non-former homelands! Remarkably, around 80% of this difference can be traced back to characteristics inherent to the former homeland areas. Underlying factors at play! The main culprits behind this endowment effect include differences in age, gender, race, marital status, and education levels. While many of these factors are entrenched and structural, targeted interventions aimed at improving educational attainment in former homeland areas, and those that are sensitive to the challenges faced by black South African youth and women in the labour market will contribute immensely towards alleviating the spatial gap.

Hope for a better future? As South Africa continues to strive for an all-inclusive national development trajectory, addressing these systemic challenges is vital. The need for tailored programmes that understand and respond to the unique struggles of former homeland communities has never been more urgent. Hopefully, policymakers

DR AYANDA MAGIDA Wits Business School

Elevated levels of disparities pose a significant challenge to South Africa’s democracy in 2024, alongside the concurrent issues of poverty, unemployment and digital inequality. Concerns about poverty and inequality have been prevalent since the establishment of the Carnegie Inquiry. This was followed by the second Carnegie conference in 1983, which focused on poverty levels among black communities and revealed that most lived in severe conditions of deprivation and poverty-stricken.

Thirty years on, the majority of South Africans endure significant challenges related to the plight of poverty, unemployment and different levels of structural inequalities. This article reframes the triple challenge by examining digital inequalities, resulting in further structural disparities within the democratic dispensation, and how they may indirectly impact the attainment of social cohesion. In 1994, a new era emerged, associated with a new dawn, “the Rainbow Nation Era”. This period brought renewed optimism, and the country endeavoured to move beyond the dark history associated with the apartheid regime. The concept of democracy in South Africa is intrinsically linked to its social cohesion. However, the current challenges the country faces continue to undermine the ideal of social cohesion.

Over the last two decades, several parallel discussions have emerged with the advent of ‘digital’ technologies. First, significant debate and concern surround ‘the digital divide’, defined more precisely as digital inequality. The digital divide, characterised by the lack of access, usage, and benefits associated with being online, contributes to growth and development. Secondly, there is an emerging perspective that social cohesion and other social measures of well-being should be included as public and economic policy objectives. Social cohesion has been researched for decades and remains an issue, with the majority of people still confronted with poverty, unemployment and different levels of inequality.

Recent advancements in Artificial Intelligence, Robotics, the Internet of Things, Big Data, and other digital technologies have exacerbated inequalities in South Africa. Structural socio-economic challenges, such as limited digital access, uneven infrastructure, and spatial disparities, impede equitable participation in the digital economy and social cohesion. The digital divide amplifies existing inequalities, particularly in rural and underdeveloped areas, preventing numerous individuals from benefiting from technological progress. Access to digital and communication technologies continues to be hindered by spatial structural socio-economic challenges

in South Africa. A prominent example is evident in the basic education and health sector. Numerous children in underserved communities continue to be disadvantaged regarding access to digital technologies. While there have been some advancements in introducing coding and robotics, universal Internet access remains a significant barrier for many schools, particularly in underserved communities. Numerous basic education institutions still lack access to fundamental amenities such as sanitation facilities and potable water, alongside other forms of structural inequities. These deficiencies contribute to the digital divide and further exacerbate the disparity between socioeconomic groups in South Africa.

The same phenomenon is observable in the healthcare sector, where individuals utilising private care can access healthcare services digitally, while the majority of those relying on public healthcare are disadvantaged. The insufficiency of infrastructure and resources to enable public health services to operate at a level comparable to private health remains a significant challenge and exerts pressure on the already overburdened public health system.

While mobile phone penetration has arguably improved, the lack of skills and meaningful and universal access to the Internet remains a challenge. The energy crisis and the infrastructural challenges also impact universal connectivity not only in underserved and marginalised communities but also in urban areas. This is evident when there is a power outage and how it impacts speed and internet connectivity. Thus, the issue of the digital divide not only impacts those with access to ICT devices, but it also indirectly impacts those who have access.

Digital access and empowerment contribute to economic, social, and educational outcomes, thereby fostering a virtuous cycle. Conversely, the absence of digital access and disempowerment result in suboptimal economic, social, and educational outcomes, potentially leading to a downward spiral. If the issue of digital inequality remains unaddressed, it will have significant implications for the upward mobility of numerous young individuals, particularly in underserved communities. Moreover, the digital divide continues to pose a threat to the development and growth of South Africa, which may impede the attainment of social cohesion.

The dynamics and interrelationships among these challenges enabled by the emerging digital technologies are complex and necessitate a comprehensive approach to inform policy public discourse and address profound technological changes in the digital era. There is a growing recognition that the social cohesion impacts of the recent advancements in various emerging digital technologies will be both positive and negative. Notably, this revolution of digital and emerging technologies has the potential for significant positive changes in fostering social cohesion and offering prospects for a more equitable future.

PROF RENNIE NAIDOO School of Business Sciences

As we celebrate 30 years of democracy in South Africa, our faculty must also reflect on how education, as a cornerstone of democratic progress, can respond to future challenges. Amidst significant progress, there remains a persistent gap in interdisciplinary approaches in higher education. Bridging this gap is essential if we are to ensure that the next 30 years are marked by genuine inclusivity. At the heart of this journey lies the transformative potential of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), particularly in higher education, where interdisciplinary programmes can be the key to achieving a more equitable and inclusive system. The rapid pace of technological advancement and social disruption means that education cannot be limited to traditional, siloed disciplines. Our faculty should continue its commitment to blending the technical expertise from our traditional flagship disciplines with insights from the humanities, social sciences, and ethical studies.

I recently led a study with colleagues from the School of Business Sciences to understand how South African higher education institutions are responding to the challenges and opportunities posed by 4IR. What emerged was a clear need for interdisciplinary approaches that not only equip students with technical skills but also embed these within broader societal, ethical, and historical contexts. Such programs cultivate critical thinking, adaptability, and collaborative skills—core competencies that are essential in the 4IR world. One notable initiative at Wits is the Digital Arts degree, which blends creative arts with cutting-edge technology, promoting interdisciplinary collaboration and preparing students for the dynamic demands of the digital

age. This approach aligns with the growing recognition of the importance of STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics) rather than just STEM.

Incorporating the arts into STEM education, as in the STEAM model, enhances creativity, empathy, and ethical reasoning—skills that are indispensable for navigating the societal impacts of technology and ensuring responsible innovation. For example, the BA in Digital Arts not only equips students with technical skills but also encourages creative problem-solving and artistic expression, which are essential in developing user-friendly and aesthetically appealing technological solutions. Similarly, integrating the economic sciences with AI teaches students to consider the socio-economic impacts of technological advancements, ensuring they can develop solutions that are both economically viable and socially responsible.

For South Africa, 4IR is not simply about automation or artificial intelligence, but about how these technologies can be harnessed to address our country’s specific challenges. From high unemployment rates to disparities in access to quality education, 4IR technologies offer potential solutions. However, to unlock this potential, we must embrace more interdisciplinary programmes that equip individuals with the skills required to thrive in the rapidly evolving world of work. Collaboration across fields is critical if we are to develop graduates who can navigate the complexities of both technology and society, ensuring they are agile, adaptable, and ready to meet the demands of modern workplaces.

At CLM, we are uniquely positioned to lead the charge. With our diverse research expertise, strong industry connections, and commitment to social justice, we have the tools needed to shape the future of interdisciplinary education.

As we reflect on three decades of democracy, it is also a time to think forward: how can we ensure that the next generation of graduates is ready for the jobs of tomorrow and the ethical and societal challenges that come with them?

4IR offers an unparalleled opportunity to create new fields of study that combine the insights of different disciplines. For instance, by blending data science with human rights law or artificial intelligence with public policy, we can create programmes that address the technological advances of our time and contribute to the broader goals of social justice and democratic governance. Ultimately, the future of higher education in South Africa lies in creating an ecosystem where students from all backgrounds have access to cutting-edge, relevant education that prepares them to thrive in a 4IR-driven world. Interdisciplinary programmes are crucial to this transformation, as they offer a holistic approach to education, ensuring that

students are not just technically proficient but also socially aware and ethically grounded.

CLM has also recently launched programmes that integrate technological, legal, and economic insights, preparing students for leadership roles in the digital economy. As we look to the future, it is imperative that the CLM faculty continues to champion innovation in education, pushing for programmes that cross traditional disciplinary boundaries and equip students with the skills they need to navigate a complex, interconnected world. The next 30 years of democracy depend on our ability to create educational opportunities that are as diverse, dynamic, and inclusive as the society we aspire to build. By fully embracing the transformative potential of 4IR, we can ensure that South African higher education is a force for economic empowerment, social justice, and sustainable development.

Let us seize this opportunity to lead and innovate. By forming strategic partnerships with industry and government to expand interdisciplinary curricula, CLM can drive the transformation needed to prepare our students for the challenges and opportunities of 4IR.

What is the role of philanthropy in a democracy, especially given its rise in the last century and the rise in big foundations?

In Just Giving-Why Philanthropy is failing Democracy and how it can do better (2018), Rob Reich delves into several arguments and justifications for studying philanthropy and its role. Other than the fact that philanthropy is an exercise of power, Reich introduces a political theory of philanthropy where he presents a framework through which the role of philanthropy in a liberal democracy can be evaluated. He asks the question, ‘can philanthropy, in current or alternative forms, support a flourishing democratic society? This is one of the questions among many that our Centre on African Philanthropy and Social Investment is focusing on. The year 2024 marks 30 years of democracy in South Africa. Many philanthropies contributed to the achievement of a democratic culture in South Africa, with several foundations supporting initiatives that led to the dismantling of the apartheid state and ushering in of democracy. As a pan African Centre, CAPSI looks at the many functions of philanthropy in Africa, with a particular emphasis on South Africa where we are based. As the country celebrates 30 years of democracy, CAPSI has taken the opportunity to critically engage with the questions of philanthropy through research, teaching and community engagement.

The Wits Fintech Hub (hereafter, the Hub) is a unique space where academia meets industry, bringing together the best of both worlds to drive innovation and advancement in the financial technology space. Our community comprises students, faculty, alumni, and industry experts, all working together to create the future of finance. With innovative technology and a deep understanding of the financial industry, our Hub is at the forefront of the fintech revolution. The Hub has partnered with Liberty Group Ltd to cooperate strategically on Fintech related projects. Where individuals can solve real-world problems with a focus on fostering an entrepreneurial spirit and the delivery of tangible commercial or societal benefits. The Hub, in collaboration with the School of Economics and Finance host a Professorial Chair Position in Financial Data Science, funded by the FirstRand Foundation, to pursue leading scholarship in Financial Data Science.

In the context of 30 years of democracy in South Africa, the Hub’s role is especially significant. The democratic era has been marked by efforts to reduce inequality and create opportunities for all citizens, and the fintech industry can contribute to these goals by promoting financial inclusion. It plays a pivotal role in the country’s digital transformation, which is critical for South Africa’s competitiveness in the global economy. Moreover, it promotes the creation of a skilled workforce that is ready to engage with emerging technologies. By offering a platform for training and development, it prepares students and professionals to thrive in the evolving financial services landscape. In this way, it supports both the immediate needs of the market and the longterm objectives of a more equitable and inclusive financial system, aligning with South Africa’s democratic values of fairness, opportunity, and progress.

Equality is often said to be the organizing principle of South Africa’s Constitution and central to its aspirations to build a democratic, free and egalitarian society. The achievement of equality is, in other words, a central measure of the success of our democracy. The work of the South Africa Research Chair on Equality, Law and Social Justice focuses on the role of the Constitution, human rights and law in achieving social and economic justice and advancing substantive equality. The various research projects of the Chair consider how the law, as developed by Parliament and the courts, and as implemented and enforced by different institutions, can frame and produce different kinds of equality and inequality, justice and injustice, amongst different sectors of society. It further explores how the law and rights might be better developed and implemented to ensure a more equitable distribution of political, social and economic opportunities, power and resources across all social groups.

The right to health is enshrined in South Africa’s constitution and as such the economics around the delivery and financing of health care as well as the developmental consequences of success in this regard features centrally on the Chair’s research agenda. Central to this agenda is research around health inequalities and the achievement of universal health coverage in our country, particularly insofar as our research has illustrated that discrimination against the poor is prevalence across the continuum of health care access. Also, with the content of the impending National Health Insurance reform, we are looking into whether transitions in healthcare financing impact positively on the progress towards universal health coverage.

Many aspects of human freedom are shaped over the life course. At each life stage the context plays a critical role. In early childhood the context children live in influences their developmental ceiling, i.e. the maximum level of cognitive and physical development they can achieve. The context throughout childhood influences the extent to which they can reach that ceiling, through shaping their access to quality schooling, appropriate healthcare and other opportunities to learn and develop free from debilitating experiences. Then in adulthood the context shapes people’s ability to utilise the potential they have realised. It is this utilisation which dramatically improved in 1994 - the context changed, opening up opportunities, political, economic and social, for greater enjoyment of potential and human freedom. But human freedom in our country is still very constrained: environments in early childhood are often harmful to children’s potential, opportunities to realise potential are constrained, by among other things, poor schooling, and while the context for utilisation has improved, poverty, unemployment and high levels of violence remain as massive obstacles. It is then 30 years since we took a big step towards freedom, but we are not in a position to claim that we are celebrating 30 years of freedom.

The Wits Entrepreneurship Clinic (WEC), launched in May 2022, plays a significant role in advancing South Africa’s socioeconomic objectives as the country reflects on 30 years of democracy. Since the end of apartheid, South Africa has focused on inclusive economic development, with entrepreneurship seen as a key driver of both economic empowerment and social justice. The WEC’s mission to accelerate economic participation and promote innovation is deeply intertwined with these democratic ideals.

The connection between the WEC and democracy showcases a dynamic synergy that fosters economic empowerment and civic engagement. The clinic provides aspiring business owners with critical resources, including mentorship, legal advice, and funding opportunities, equipping them with the tools necessary to launch and sustain their ventures. In doing so, WEC not only stimulates local economies but also promotes the principles of democratic participation. As citizens gain the ability to create their businesses, they enhance their economic independence, strengthening their capacity to engage in civic activities.

In a democratic society, entrepreneurship serves as a vehicle for social mobility and innovation, allowing diverse voices to contribute to the economy. WEC prioritises underserved communities, helping to bridge gaps in access to resources and fostering inclusivity. By empowering marginalised groups, WEC contributes to the democratic fabric of South Africa, ensuring that entrepreneurship becomes an inclusive force for change. As these entrepreneurs succeed, they become role models and advocates, demonstrating the power of individual initiative within a collective framework.