Re-peopling Bonegilla Online

Bruce Pennay OAM

Bruce Pennay OAM

A Research Guide for exploring the digitised Bonegilla Cards and Administration Records at the National Archives of Australia

Bruce Pennay is an Adjunct Associate Professor working from the School of Agricultural, Environmental and Veterinary Sciences at Charles Sturt University. He is a volunteer at the Bonegilla Migrant Experience.

Designed and published by Wodonga Council 104 Hovell St, Wodonga, VIC 3690

Printed by Active Print

ISBN: 978-0-646-84667-5

© Bruce Pennay 2022

The views expressed in this research guide are those of the author and not necessarily those of Wodonga Council. All reasonable efforts have been made to obtain permission to reproduce materials included in the guide.

The author and the Bonegilla Migrant Experience welcome contact with regard to copyright or privacy. bonegilla@wodonga.vic.gov.au www.bonegilla.org.au

INTRODUCTION

During 2019 and 2020 the National Archives of Australia digitised two sets of records emanating from Bonegilla when it was Australia’s largest and longest-lasting post-war migrant reception centre, between 1947 and 1971. www.naa.gov.au/explore-collection/immigration-and-citizenship/migrant-accommodation/bonegillamigrant-reception-and-training-centre

This guide is intended to help novice and experienced researchers to:

• access the newly digitised material;

• explore and search within each of the three digitised Series;

• unravel some of the reception centre bureaucracy; and,

• locate related sources.

There are four main parts in the guide, one for each of the Series which have digitised. Each part is studded with reference items selected from the records as illustrations which help find and situate individuals or groups and advance understandings of reception processes and practices. The reference items cited will make the curious even more curious. A final fourth part provides a guide for finding our more.

PART 1

Re-peopling Bonegilla with Bonegilla Cards (Series A2571)...........p.2

PART 2

Re-peopling Bonegilla with Bonegilla Cards (Series A2572)........p.10

The name index or registration cards of the 310,000 non-British Europeans who arrived at Bonegilla are now online. New and experienced family historians welcome this ready access to two sets of records which help them track the arrival experiences of family or friends. They find on the Bonegilla Cards snippets of personal information and, on at least half of all the cards, a passport type identity photograph. The cards re-people the National Heritage Site with the migrants and refugees who were temporarily there as residents.

PART 3

Re-peopling Bonegilla with Centre Administration Records (Series A2567).............................................................................................p.18

The centre administration records were retrieved from the migrant camp when it closed in 1971. These records help family historians to contextualise arrival experiences at different times. More generally they reveal not only different aspects of migrant camp life, but also contemporary mind sets about the reception of non-British newcomers in the period from which they are drawn, that is from 1956 to 1971. These records re-people Bonegilla with some of the people who managed and worked at the centre.

PART 4 Finding our more.........................................................................................p.26

The final part of the guide helps with frequently asked questions about the Bonegilla Cards and suggests other places to explore further.

Research guide Introduction 1

Re-peopling Bonegilla with Bonegilla Cards

The Bonegilla Cards

The newly digitised records include many of the Name Index or Registration Cards (known as the Bonegilla Cards) compiled for each new arrival at Bonegilla. Each of the Bonegilla Cards contains, almost invariably, name, nationality, age, marital state, religion, ship, date of arrival, date of departure, work destination and/or destination address. About half of the Bonegilla Cards prepared for all 310,000 arrivals at Bonegilla include a passport-type photograph and personal identification details. The cards were used primarily as employment records. As such, they were part of the control mechanisms which government used to reassure itself and the Australian public that it was closely managing the reception and work placement arrangements made to cope with the arrival of the huge number of aliens it had helped come to Australia.

The Bonegilla Cards are arranged physically in two Series, each with two parts. The big divides between/within the Series is chronological: Series A2571 covers 1947 to 1956; and Series A2572 covers 1957 to 1971. Series A2571 is arranged alphabetically in two parts, with Greek new arrivals separate from all others. Series A2572 is also arranged alphabetically, but again in two parts: first from 1957 to 1960 and then from 1961 to 1971.

Assisted migrants from Germany and Austria queue for identity card registration after their arrival at Bonegilla. Within two to three weeks, they would have a one-on-one interview with an employment officer, who would assess and record each person’s occupational potential. They were then directed to a workplace where they were required to work for two years. →

Re-peopling Bonegilla Online 2 PART 1

The Border Morning Mail, October 22, 1959

In retrospect, the Bonegilla Cards have taken on additional roles as a demonstration of administrative efficiency and as memory pieces. In 1971, when the reception centre was about to close, ABC-TV recorded a This Day Tonight program in which Mario Giselli, a former migrant, revisited Bonegilla to help viewers make sense of what the place had been about. In one scene, a neatly dressed filing clerk was shown working on the Bonegilla Card files. The voice-over credited the clerk, John Yeomans, as being the person who created and then maintained the card archive. With what must have been admirable diligence, Yeomans had ensured that the large loose-leaf, manually operated card system remained intact. For the camera he impressively plucked out Mario Giselli’s card, which bore his photo. Giselli used it to ponder on his earlier self and the moment of his arrival. The well-kept archive bore witness to the Immigration Department’s efficient record keeping. But, what is more, the cards were no longer just a record of ‘them’, but a memory prompt for ‘you’ and ‘yours’. (The TV show is accessible at https://about.csu.edu.au/community/initiatives/bonegilla/bonegillas-end.)

Research Guide Part 1 3

‘Children from the War’, Hela Salwe, 2018

↑ Photographer Helga Salwe has shaped public memory of post-war immigration with a triptych of three unnamed children who arrived as displaced persons.

Exploring Series A2571: Bonegilla Cards, 1947-1956

Series A2571 covers arrivals between 1947 and 1956. The cards supply personal identification, arrival and departure details. A card was prepared for each person, whereas family members are often clustered on a breadwinner’s card in Series A2572. The online presentation of this series makes it easy to search directly by surname. Each individual card is indexed separately. The form headings are self-explanatory.

Personal identification details

The Bonegilla Cards almost invariably include a passport-type photograph for each arrival until July 1954. The photographs were generally supplied by people applying to migrate to Australia. Some photographers allowed smiles and/ or supplied a photograph with scalloped edges. After July 1954, the personal identification details and the space for a photograph are left blank. That form of surveillance was deemed no longer necessary. The cards were re-designed so as not to include that close identification material, hence the need for a second series of records. Department officers completing the cards anticipated the need to record less information. As a result, for some time after July 1954 the cards have little more than details of arrival and a destination code, which relates to the type of work the migrant would undertake.

Back of card records

The second screen page in Series A2571 has frequently been over stamped with a list of items of clothing issued to those in need. Initially army disposal clothing was issued and this listing kept track of how those resources were used. Subsequently charity organisations, mainly the Red Cross, helped supply clothing, and departmental officers had no need to keep track of how those items were dispersed. Consequently, the listing was eliminated in the redesign of the card. The listings indicate how impoverished the new arrivals were. A blank list meant no items were issued.

‘By Design’. Visual artist Pia Larsen has reworked one of the list of items on the back of the cards. She saw the card as impersonally uniforming a newly arrived person as an object. She has insisted on inserting the body of the new arrival.

Re-peopling

Online 4 PART 1

Bonegilla

Pia Larsen, By Design, 2019, relief print 75.4 x 57cm, unique state.

→

Famous, infamous and ordinary [heading]

Some cards are of people who became famous or infamous. Most cards are of ordinary people undertaking what was for them and their families the extraordinary task of migrating from one country to another.

→

Dr Karl Kruselnicki, the popular science communicator, has traced his family’s migration story. The information on the Bonegilla Cards refines the story he tells. A visit to the site awakens deeply felt family memories of employment indignities involved in migrating and the hurt of family separation. https://education.abc.net.au/ home#!/media/3027884/dr-karlsexperience-at-bonegilla

→

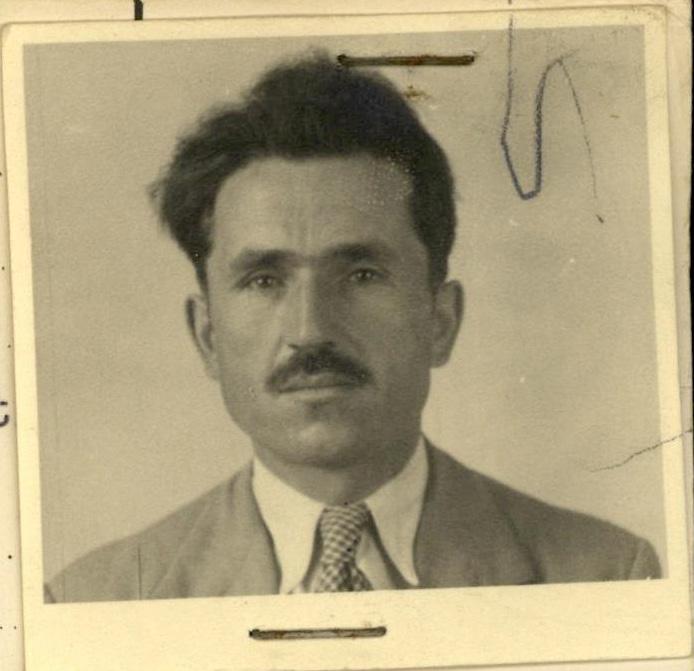

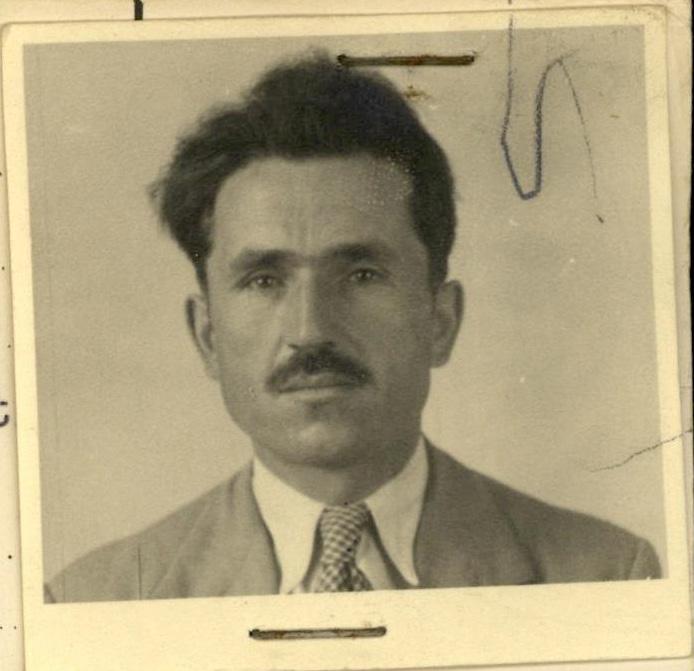

Bronius (Bob) Sredersas served as an intelligence officer in the Nazi security service and was a collaborator during the German occupation of Lithuania 19411945. He Germanised his name to Bronislaus Schroeder in June 1941 on the eve of the German invasion. At the end of the war, he concealed and renounced his German citizenship and reassumed his Lithuanian name. Sredersas qualified as a Displaced Person and was accepted into Australia.

NAA A2571, KRUSELNICKI LUDWIK Item ID 203622409

NAA A2571 SREDERSAS BRONIUS Item ID 203695584.

From Bonegilla he went to Wollongong. He was to amass a huge art collection which he gave to Wollongong Art Gallery before he died in 1982. A room at the gallery was named after him. After a recent investigation into Sredersas’ past, Wollongong City Council has revised the way it acknowledges his gift. Australian 20 June 2022.

Research Guide Part 1 5

Accessing the Bonegilla Cards in Series A2571 and A2572

The easiest way to access digitised items in the two Bonegilla Card series is to:

• Go to the National Archives website: “naa.gov.au”

• Click on: “Explore the collection”

• Click on: “Go to RecordSearch” in blue

• Select ‘Name Search’ from the blue menu bar at the top of the page

• Enter details

• Family name and given name

• Category of records use drop down menu to select “All records”

• Untick box ‘Use exact spelling’

• Hint: Keep date field empty to see all results

• Click on: “Search”

• Look for a search result with Series no. A2571 or A2572. The search results can be sorted within the results table by clicking on the blue titles along the top of the table ie ‘Series no.’, ‘Control title‘ etc.

• To access the ID card click the digitised item icon on the listing you would like to view.

▄ Note some results will appear more than once in Series A2571 or A2572. You may prefer to click on the result with a capitalised name.

▄ Note children are listed on parents’ cards from 1957 onwards. To find a listing of a child search the parents’ cards. If arrivals come as a family, children are normally listed on the mother’s card.

▄ Some cards may not have all fields complete, such as departure date, record of the block number where they lived or destination.

▄ Having trouble finding an ID card? Try common misspellings or type at least the first three letters of the family name or given name followed by * (a wild card symbol).

▄ Also available are passenger arrival records, passenger departure records and internment or alien registration records. .

▄ Note photographs and identity descriptions are not included for new arrivals after June 1954.

▄ Right click the image to find how you might save or copy it.

▄ Note item IDs are included in this guide, They can be used to go directly to that item by typing them into ‘Item ID’ in an Advanced Search

For more general help go to https://www. naa.gov.au/explore-collection/search-people/ researching-your-family or go the other research assistance links at the end of this guide.

Re-peopling

Online 6 PART 1

Bonegilla

Selected Search Items, Series A2571

The first three selected items show something of how the card system worked. The last three indicate a variety of migrant experiences for the work able, the young and the old.

The registration system was new when Kasys Adickas arrived in the first contingent to occupy Bonegilla in November 1947. The card is filled in very carefully and even includes comments on his level of English. The sharp eyed will notice the photographs on all the people in the first contingent were taken by the immigration authorities and numbered in a once only sequence.

→

Friedrich Ade arrived in October 1954. As for all arrivals after July 1954, there is no photograph or personal identification details on his card or those of his family.

→

A2571, ADICKAS, KASYS, Item ID 203672415.

A2571, ADE FRIEDRICH, Item ID 203672390.

Jan Adamowicz received an issue of some items of clothing.

→

A2571, 2/2, Item ID 203002002

Research Guide Part 1 7

Josef Adler did not report to the workplace he was allocated. His card and those of his wife and four children are marked REFUSED TO DEPART. The family left when he and his eldest daughter took up work at Ardmona Canneries in Victoria. Assisted migrants had the right to refuse a work placement but ran the risk of losing unemployment benefits and access to free hospital care at the centre if they exercised this right more than once.

→

A2571, ADLER JOZEF, Item ID 203672425.

Giovanni Addabbo arrived shortly after unemployed Italians protested vigorously in July 1952 about not being allocated work. To ease tensions in the centre, ‘emergency’ work was found in defence force establishments. His card shows him working at Puckapunyal, Williamstown and Bandiana before he was allocated work on the hydroelectric scheme in Tasmania. While he worked

A2571, ADDABBO GIOVANNI, Item ID 203672425. at Bandiana he lived at Bonegilla and was classified as an ‘out-worker’ with the address CIC (Commonwealth Immigration Centre) Bonegilla.

→

Re-peopling Bonegilla Online 8 PART 1

Anna Adamowicz was a prettily dressed 3-yearold. Her father, Josef, was allocated a workplace and went to it two days after arriving. A month later he found accommodation for her mother, Zofia, near where he worked. Zofia joined him after Anna was discharged from a nine-day stay in Bonegilla Hospital. Anna was sent to a Salvation Army orphanage where she stayed for three months. When Zofia was 7 months pregnant she took Anna from the orphanage and they both returned to Bonegilla for a week before they went to the Uranquinty Holding Centre.

→

A2571, ADAMOWICZ ANNA, Item ID 203672348.

Tatjana Afanassieff was 50 years old when she arrived. Australia was after the work-ready young who would boost its workforce and women of childbearing age who might help increase its population. Tatjana did not fit either of those categories. Selection officers overseas accepted her application because she was to be supported in Australia by her son Alexander. She arrived with Alexander and his wife, Helene, who had probably made her acceptance a condition on which they agreed to migrate. Tatjana was sent to temporary accommodation at the Scheyville Holding Centre, because the employer could only supply accommodation for the worker and his wife.

→

A2571, AFANASSIEFF TATJANA, Item ID 203672533.

Research Guide Part 1 9

Re-Peopling Bonegilla with Bonegilla Cards

Exploring Series A2572: Bonegilla Cards 1957-1971

Series A2572

Series A2572 contains the official individual records of approximately 128 000 individuals who arrived at the Bonegilla Reception Centre as non-British assisted migrants and refugees between 1957 and 1971.

▄ Note again that the cards in this series do not have photographs or personal descriptions.

▄ Note that there is not a card for each arrival. Dependants are often included on a breadwinner’s card.

The cards

Each card contains, almost invariably, name, nationality, age, marital state, religion, ship, date of arrival, date of departure, work destination and/or destination address. The line for ‘Address of next of kin’ is most frequently used to list the names of a man’s wife and children. The space beneath marital state is used to add the names and ages of children of women. Trade is only sometimes listed, as if the interviewers were not prepared to accept unverified self-descriptions. The designation ‘ship’ is overwritten by flight when, by the mid-1960s over half the new arrivals came by plane.

The cards are arranged in alphabetical order by surname, with the breadwinner preceding dependants. There are no photographs or personal identification details in this series. Often a written departure destination appears on the back of the card.

The Bonegilla Cards were used primarily as employment records, noting carefully initial work placements, but they also included movement details, which were used by the finance department to calculate the tariff which each person was obliged to pay for food and lodgings. Periods of absence or hospitalisation, often refined to hours, are noted, as they affected messing charges. There is more than one destination where the work was initially temporary.

Re-peopling Bonegilla Online 10 PART 2

An unnamed husband and wife attend a work placement interview with an employment officer and interpreter at Bonegilla. At the interview, the employment officer would note the ‘occupational potential’ of each arrival. He would try to align that potential with the list of vacancies he had to fill, mindful of his duty to place all workers as soon as possible. He recorded his assessment of potential in coded form and/or his work placement decision on each card.

→

NAA A12111, 1/1956/22/55

Widening the net of donor countries

Into and through the 1960s Bonegilla became more diverse. From 1959 and through the 1960s the most numerous new arrivals were Greeks, Germans, Dutch and people from Yugoslavia, (especially, Croatians). Recruiting officers cast a wider net, taking in migrants from a greater diversity of countries, including for example, Ireland, Sweden, Finland, France, South Africa, Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Armenia and Cuba. In 1966 the Australian government looked even wider. It announced that applications for immigration would be considered on the basis of whether the applicants were suitable as settlers – that is people who were able ‘to integrate readily’, and who ‘possessed skills or qualifications useful to Australia’. Provision was made for families of mixed race to be sent to Bonegilla, rather than directly to worker hostels after the minister exercised his discretion to accept non-Europeans according to their ‘general suitability’ and ability to be integrated.

The Border Morning Mail periodically advised its readers about some of the new sets of arrivals. It observed that the first Finns had come ‘from Arctic wastes to century heat at Bonegilla’ (November 27, 1959). It anticipated the first arrivals from Spain would have Bonegilla ringing with ‘clicking castanets and fancy fandangos’ (June 13, 1959). It depicted families from the USA becoming accustomed to the ‘simple and frugal life at Bonegilla’ (October 15, 1960). Norwegians were ‘in search of steady employment and, above all, sunshine’ (August 1963). The first sole arrival from Chile was welcomed (December 18, 1965). The first guest workers arriving under the new Special Assisted Passage Scheme were photographed (July 21, 1967). Refugees fleeing Soviet repression in Czechoslovakia were ‘beautiful’ and ‘young intellectuals’ (October 15, 1968).

Research Guide Part 2 11

NAA, A2567, 1969/86, Item id 7525426, screen page 15

↑ In April 1970, the Centre Director sent a clipping to the Director of Publicity from The Border Morning Mail, April 18, 1970 illustrating ‘a polyglot of nationalities’ with a photograph of twelve new arrivals, each from a different nation.

There was a sharp influx of refugees from Hungary in 1957 and from Czechoslovakia in 1968. Both sets of refugees included people who were well qualified. They included single females, who had not been directed to Bonegilla since the Displaced Persons scheme ended in 1952. They also included Jewish people, who had rarely been directed to Bonegilla. Normally Jewish welfare organisations met Jews on arrival and provided them with hostel accommodation in a capital city.

The observant will detect among the cards an occasional British migrant, misdirected to Bonegilla and quickly moved away. Maltese migrants insisted they were British and demanded to be moved from Bonegilla.

There are comments on some cards that explain reception practices incidentally. So, for example, an application for readmission was denied, because of ‘our long-standing practice not to readmit people who have voluntarily left the work which they were allocated’. So, too, a female worker at the centre lost her job, when her husband refused to go as directed to outside work. This meant he had become unemployed, and ‘no woman was to be employed if her husband was unemployed’. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s the prevailing view was that the breadwinner was usually male.

Re-peopling Bonegilla Online 12 PART 2

Departures

Collectively the cards indicate a steady demand for unskilled migrant labour, particularly for harvest work and in the new manufacturing industries. Migrants were directed all over Australia to workplaces. If assisted migrants arrived before 1959 they were under contract to work as directed. If they arrived after 1959 that requirement was eased and they were obliged to live in Australia for two years or repay their passage. Refugees were regarded as ‘migrant refugees’ and were helped to find jobs but were not directed to a workplace.

• Some new arrivals were directed to worker hostels where they would be accommodated while they worked or where they were more likely to find work.

• Many migrants, especially those who were able to muster support from already established ethnic groups, were able to arrange private accommodation. The option to move direct to private accommodation was used more frequently through the 1960s, when the post-war housing shortage eased and when assisted migrants were not under contract to work as directed.

• Some were directed to Benalla, the only surviving Commonwealth Holding Centre after 1957. Benalla served as a worker hostel for migrants employed in the district. Its special function was to care for fractured families, especially supporting mothers with children. The mothers were expected to take up work in nearby factories.

▄ Note that further research may reveal that Middle Eastern arrivals were usually sent to Sydney destinations. There may be similar dispatch patterns.

Research Guide Part 2 13

Selected search items, Series A2572

The increasing diversity of Bonegilla residents

The first group of selected reference items indicate something of the growing ethnic diversity of assisted migrant and refugee arrivals. It notes a special group which endured a major misfortune. It also notes criminal behaviour and the strange instance of a person arriving allegedly as a stowaway.

• A survey of the first thirty items in one box in the series indicates arrivals from Finland, Denmark, Norway, Spain, Egypt and United Arab Republic.

• White Russian refugees with the surname Malishev arrived at different times on different ships or planes from China. A2572 MALISHEV. They were frequently dispatched to work at International Harvester Company and to be accommodated at the Norlane hostel in Geelong. That arrangement may have been facilitated by the World Council of Churches which sponsored their arrival.

The Melbourne Sun pictured the arrival of White Russian refugees.

→

• Klara Hedwig and her daughter, Katalina were Jewish, A2572 HEDWIG KLARA Item ID 203534985. Jewish Welfare Organisations missed the Hedwigs and several weeks passed before they located them and arranged alternative accommodation.

• Sven Andersen and his family were aboard the migrant ship Skaubryn when in 1958 it caught fire and sank, A2572 ANDERSEN SVEN, Item ID 203601388. Special attention was given to the survivors at Bonegilla. Local church and community groups donated clothing and goods for those who had lost all their possessions, A2567, 1958/54.

• Alois Albrecht’s card shows him released from gaol and makes reference to the violence for which he had been convicted, A2572 ALBRECHT ALOIS Item ID 203601162.

Sun Bonegilla Photograph Exhibition, 1987

Re-peopling

Online 14 PART 2

Bonegilla

• Johann Annuschitsch arrived allegedly as a stowaway. A newspaper clipping added to his card shows that he was charged with abducting and carnally knowing a 14-year-old girl, A2571 ANNUSCHITSCH, item ID 203601478. No details are given of his stay in Bonegilla, which may have preceded his deportation. It was unusual for Bonegilla to be used for such a purpose, it was strictly a reception centre intended only for new arrivals.

Workers accommodated at Bonegilla

A large number of newcomers were directed to jobs at the Bonegilla Reception Centre. Indeed, the Department of Immigration boasted that almost from the beginning of the mass migration program as many as 90 per cent of its employees at migrant accommodation camps were new arrivals. The cards in this series have a new arrival working as a crèche worker, labourer, hygiene man (toilet and ablution block cleaner), woodman, barber and patrolman. There was a big turnover of kitchen hands and cooks. Those who became interpreters worked for the Commonwealth Employment Service, so like all the other ‘out-workers’ there address is given as CIC (Commonwealth Immigration Centre) Bonegilla.

Department of Immigration publicists photographed Maria Alvarez from Spain in 1967 working in the kitchens. →

NAA A12111, 1/1966/22/16

Research Guide Part 2 15

Migrant workers employed for expanding Hume Weir into Hume Dam, were classified similarly. So were well qualified people who found jobs locally before they found accommodation outside the Centre. By catering for out-workers, Bonegilla was functioning as a worker hostel as well as a reception centre. There were, too, several people living and working at Bonegilla who were neither migrants nor refugees, but Bonegilla in its last days had the capacity to accommodate them.

• Helvi Savolainen arrived with her husband Olavi and four children from Finland in 1963, A2572 SAVOLAINEN HELVI Item ID 12876368. Olavi was first given work at Bonegilla. After about 18 months he moved back and forth from the centre pursuing work opportunities and leaving his family at Bonegilla. Helvi had another two children while at Bonegilla. She was allocated different jobs at the centre and, indeed, a second card was required to list them all. The family left in 1967. In the meantime, Helvi was the prime child carer. By accommodating the Salvonainen family while the male breadwinner sought work and accommodation, Bonegilla operated as a holding centre as well as a reception centre. This family’s stay was a long one, explained in part by Helvi’s ill health.

Re-peopling

Online 16 PART 2

Bonegilla

Albury LibraryMuseum Bonegilla Collection

• There was an official record of the arrangements made for the family to leave the centre (A2567/109, Item ID 7538200). Helvi’s staff record is online in Series A2570. Her family have donated family photographs to the Albury Library Museum.

▄ Note how her son Tuomo (Tom) was deleted from her card and issued with a separate card once he turned 16, A2572 SAVOLAINEN TUOMO Item ID 203516660. All cards distinguished children over 16. They were expected to take up work as directed. They paid a higher tariff for their accommodation.

• Arthur Potter was not a migrant or a refugee, but an Australian teacher living with his family at Bonegilla, A2572 POTTER ARTHUR H, Item ID 203519187. Several young single Australian men worked at one of the other of several banks established at the centre. They were usually there for a short term. The cards were used to track their mess charges. Similar arrangements were made for Shipboard Education Officers who were lodged at Bonegilla when they were not on board the migrant ships instructing newcomers.

• Jiri Poupa, a Czechoslovakian refugee in 1968, was a medical practitioner whose qualifications were recognised. He was assigned to out-work at the Commonwealth Health Laboratory and lived at Bonegilla until he found accommodation A2572 POUPA JIRI, Item ID 203519212.

NAA A12111, 1/1961/22/7

↑ Laurentinu Alduca was a kitchen employee who eventually became head cook and acting catering supervisor, A2572 ALDUCA LAURENTINU, Item ID 203601195. He was one of a large number of migrants who became longterm employees and Bonegilla residents.

Research Guide Part 2 17

Re-Peopling Bonegia with Centre Administration Records

Most of the miscellaneous administration items in Series A2567 were retrieved from the reception centre when it closed in 1971. Almost all relate to the period from 1956 to 1971. They show that the business of managing a reception centre was complex, even though its prime function was simply to receive, accommodate and care for newly arrived workers and their dependants while the Commonwealth Employment Service arranged for the employable to find workplaces where they were most needed. This series of administrative items includes, among other things, regular reports on the disposition of national groups throughout the camp; reports from the centre’s adult education facility, its state school, its staff club and its cinema; and files on distinct cohorts of arrivals - including Hungarians, Czechoslovakians, White Russians, Maltese, Dutch, Armenians from Egypt and Europeans in Ethiopia.

The items show the Department of Immigration acted as a ‘landlord’ for government and nongovernment agencies using the facility. Among those who had official representatives residing at the centre were Commonwealth public service departments, such as the Department of Labour and National Service (Commonwealth Employment Service), the Department of Health and Department of Social Welfare. State Government teachers and police resided on site. Non-government bodies such as the Lutheran, Catholic and Presbyterian churches and the Young Women’s Christian Association also had representative residents. Each of these bodies kept the Director of the Centre informed of their activities.

▄

Note that these are working files not neat summaries. Documents are sometimes repeated or appear in draft form. The first document in the file is now at the last screen page. For a chronological sequence, it may be advisable to read a file from the last screen page.

▄ Note again the control system year prefix may indicate the date beginnings of files in each item. Some are from 1956, but they are mostly from the 1960s.

▄ Note that most of the files compiled after 1965, when there was a new director, have an index, which may help family historians looking for a mention of specific individuals. However, they might expect little more than a mention of a name in a list.

Re-peopling Bonegilla Online 18 PART 3

Introductory notes on selected items, Series A2567

Buildings

There are many items relating to building construction and maintenance work. Most related to the consolidation of the centre into a few key blocks. In 1958 the centre had the capacity to accommodate 14,500 but occupancy was usually about 7000. In 1960 it had capacity to accommodate 3750, including up to 2000 transients. There had been attempts to make Bonegilla more ‘family friendly’ with new furnishing in 1956, but there were greater opportunities to improve the accommodation with the consolidation of the centre into fewer blocks initiated by the Minister, Alexander Downer in 1958. The department boasted in 1965 that the centre has lost ‘the stark outlines of its military camp beginnings’. A12111, 2/1966/22A/11, Item id 7454739

Two huts could be joined to accommodate a family of four. During the 1960s hut usage was calculated on 2.0 persons per hut and most huts were used by a single person. During the 1950s the average occupancy of each hut was 2.4 persons.

Research Guide Part 3 19

→

• The building records show that the huts in Blocks one to nine and Block 11 were not occupied or maintained after 1952. By 1958 those huts were beyond rehabilitation and stood abandoned, like ghost towns in a western movie.

• In this series there is an item ‘Blocks Opening and Closing’ (A2567, 1956/104, Item id 7612260). A report at the beginning of ‘Centre Inspection’ (A2567, 1963/15, Item id 7612189) details the arrangement of the Centre in 1963. A map showing the layout of the Centre in the 1960s is at AA1971/666 PLAN 2, Item id 214704).

• There are several items reporting on the transfer of blocks to the Army from 1965, which indicate how the site would be shared by migrants and military personnel. The Director wanted to draw clear lines between the Centre and the Army Camp and voiced concerns about letting Army personnel worship at the churches in Centre (A2567, 1965/99A, Item id 7612250, screen page 29).

• Health Inspector Reports gave close attention to food preparation places, ablution blocks and the hospital as well as overall hygiene.

• ‘Accommodation Disposition’ items show the number or residents in each block but were primarily focused on the number of residents of each nationality. There were regular reports on the number of longterm unemployed by nationality.

Support services

• The item headed ‘Young Women’s Christian Association of Australia’ has a report summarising the support services and facilities at the centre, screen pages 50 to 76. The YWCA hut offered ‘recreational and assimilation activities’ particularly aimed at transients, that is a friendly meeting place, music, table tennis, tea and coffee.

• Creative Leisure Centre items detail the activities provided for children. The ‘State School’ items include a history of the Bonegilla School. It has a list of 44 different nationalities attending the school (which given the subsequent dissolution of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia would now total 50). There are items with reports on how the pre-school crèche functioned and how only children of hospitalised women were allowed to attend.

• Reports from the cinema on film attendances and programmes show there was a lot of interest in action films (e.g. Tarzan, westerns and war films) and musicals. Hence attendance was high at ‘Tarzan’s Three Challenges’, ‘Gunfight at O.K. Corral’, ‘The Great Escape’ and ‘The Singing Nun’, probably because they did not require much English to be understood and enjoyed.

• The Amenities Centre Committee reports show how the committee used a proportion of cinema takings to buy books, newspapers/magazines for the library, and equipment for sporting teams as well as the school.

• The Hume Public Service Club was for staff employed at the centre. Its reports detail changes to the club rooms including, for example, the addition of another hut to serve as a dance floor.

• ‘Clubs’ deals with the centre’s principal sporting facilities and shows the share arrangements made with the Army and the community.

Re-peopling Bonegilla Online 20 PART 3

• There are items with files of reports relating to the Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Presbyterian chaplains at Bonegilla.

• Film and Study Centre was the adult education centre. Items in this series contain reports on the evening classes all centre staff had to attend until they could demonstrate their competence with English. They also report on the arrangement for migrant ship language instructors who were accommodated at Bonegilla when not on ship duty.

An English language class in the Film and Study Centre, The Film and Study Centre boasted that it offered more of an introduction to Australia as well as instruction in English.

A12111, 2/1966/22A/20, Item id 74547418

→• ‘Training Documents’ include a lengthy list of variant names used by European migrants (A2567, 1966/175/1, Item id 7525484, screen pages 6 to 15). So the Hungarian Erzesbet becomes Elizabeth or Lizzy; the Dutch Hendrika becomes Hetty; the Yugoslav Stanimir becomes Stan; the German Klaus becomes Nicholas or Nick; the Italian Giuseppe becomes Joseph or Joe. The document includes guidance on using prefixes such as ‘van’ or ‘van der’ and on patronyms and double surnames.

• There are several reports dealing with the medical services and facilities at the centre. The services were free of charge but only available to migrants who qualified for the services. ‘Deaths’ (A2567, 1956/93, Item id 7527777) records 25 deaths for which official reports were required. ‘Mental Cases’ (A2567, 1956/92 Item id 7526448) is heavily redacted to protect privacy.

• To help attract and support skilled migrants by 1958 the Commonwealth Employment Service arranged for Trade Tests in carpentry and joinery (A2567, 1957/151, Item id 7612277). Other records point to the way it arranged similar tests for electricians.

• The ‘Red Cross’ kept track of the support its state and district members gave a succession of refugee groups from 1957 to 1970. It helped assisted migrants, for example, by creating foreign language phrase books for hospitalised Hungarians, Greeks, Italians and Yugoslavs. It kept detailed records of the clothing it supplied, including layettes for the new-born and footwear for the adults at Bonegilla and Benalla. It supplied escorts on trains bringing new arrivals from Melbourne to Bonegilla.

Research Guide Part 3 21

• An item simply headed ‘Assimilation’ shows local community group interest in helping new arrivals. Football clubs and music groups wrote seeking new recruits. Church organisations, service clubs and ethnic organisations offered newcomer welcomes. The Director declared that the aim of the centre was ‘to assist our newcomers to settle happily in the community’.

Migrant women board the centre bus for a CWA welcome meeting at the local CWA hall.

→

A12111, 1/1965/22/3, Item id 745465

Problems

• A report on unemployment disturbances in 1961 begins with records related to complaints by German migrants about the lack of jobs and about the cleanliness of the ablution areas. There is a lengthy petition from migrants complaining about not getting jobs in April 1961, well ahead of a riot in July. The item contains the Director’s accounts of the July disturbances which, he insisted, were instigated outside the centre. It goes on to detail later disturbances by Yugoslav (principally Croatians) and Spanish migrants that were hidden from public view. (A2567, 1961/168, Item id 2017896).

• Supervisors were in charge of each Block. Their reports detail problems with property damage, theft and noise among other things. Stocktakes listed huge amounts of missing material. Pilfering was common. Patrolmen manned an entry gate principally to try to prevent unauthorised removals.

• Problem case reports are sometimes heavily redacted. They show something of the work done by social workers who detailed the difficulties migrant clients encountered in attempting to restructure their lives in Australia (for example A2567, 1963/20, Item id 4029973).

• ‘Problems with work placements’ include complaints from both employers and from migrant employees.

Re-peopling Bonegilla Online 22 PART 3

• Crime reports cite specific instances of theft, vandalism, cruelty to animals and assault.

• Migrants wrote frequently complaining about the centre and/or the lack of employment. Their complaints are often penned in their mother tongue and a translation has been added. They appear in several different items.

• ‘Translations’ includes letters referred from the department for translation at the centre. There were frequent queries about recovering unpaid wages, retrieving baggage and claiming travel costs to their work destinations.

Migrant Refugees

• The item ‘Unaccompanied Minors’ contains lists of unaccompanied Hungarians boy and girl refugees. The Reception Centre had difficulty in coping with and supervising unaccompanied youths.

• The item on the Czechoslovakian refugees (A2567, 1968/27, Item id 7525363 lists files on individuals at screen page 12. Some files show the minister’s concern about the non-acceptance of overseas qualifications: he was displeased with the way state regulations might impede the appropriate employment of refugees who were medical practitioners and dentists. Other files contain reports from the social worker detailing the problems the Reception Centre encountered in placing un-partnered men and women supporting children and single women who had, before 1968, most often been sent to Benalla.

Migrant Accommodation Business

• Throughout there is an emphasis on the careful use of public money. The ‘Whereabouts’ items usually involve trying to track people for unpaid financial obligations.

• There are numerous reports on public service regulations and notices. The centre kept close track of staffing levels and staff duties.

• ‘Reception Orders’ shows arrangements for the routine initial ceremony for receiving new arrivals.

• Items explain the ‘Special Passage Assistance Scheme’ of 1966 which broadened intakes to include guest workers from a large variety of countries. Australia increasingly wanted skilled and experienced workers.

• Two items deal with sponsored migration by the Lutheran World Federation and the Federal Catholic Immigration Committee.

• ‘Publications’ contains reports from local and overseas newspapers, generally publicising the immigration program, but sometimes critical of it. One item has complaint by the Centre Director to a local publication referring to Bonegilla as a ‘Camp’ rather than a ‘Centre’: that wording ‘was not in keeping with our purpose or our function’ (A2567, 1957/86 Item id 7525424).

Research Guide Part 3 23

The Border Morning Mail, October, 8, 1971.

↑ The four members of the Vuksan family were pictured as the last arrivals. A2572 VUKSAN MIRKO, Item ID 20353321 and A2572 VUKSAN ELZA, Item ID 203533219

• ‘Accommodation – General’ (A2567, 1971/99, Item id 7612246) deals with the closure of Bonegilla. The ‘Minister’s Statements’ relate to immigration and citizenship generally. The Minister, Philip Lynch, in January 1970 explained how Bonegilla was to be readied for closure (A2567, 1967/86B, Item id 7525427, screen page 118). There are several items on the arrangements for closing Bonegilla at A2567 1960/63/1; 1962/9; 1967/173 1969/59C and 1971/99.

Re-peopling Bonegilla Online 24 PART 3

PAGE LEFT BLANK DELIBERATELY

Research Guide Part 3 25

Finding out more

Frequently Asked Questions about the Bonegilla Cards

The most frequently asked questions relate to the codes used on the Bonegilla Cards.

Most frequently used codes

• The number placed mid-card left gives the Block address at Bonegilla.

• ‘CIC Bonegilla’ stands for Commonwealth Immigration Centre, Bonegilla.

• ‘MAC’ is for Migrant Accommodation Centre.

• ‘T’ stands for ‘Temporary Accommodation’, usually at a holding centre.

• ‘PP’ is for ‘pending placement’ from the assigned destination, usually to a worker hostel.

• ‘MOI’ is for a movement initiated by the migrant, usually to a private address rather than to a designated employment.

• ‘AL’ and ‘AWL’ are for leave with or without permission.

• ‘REI’ indicates return from temporary employment.

• ‘SM’ is for single man; ‘MM’ is for married man; ‘SW’ is for single woman; ‘MW’ is for married woman; ‘H/F’ is for head of family’ ‘W’ is for widow, that was any woman who had dependent children and was not accompanied by a male breadwinner.

Movement details

The registration cards were used primarily as employment records, but they also included movement details which were used by the finance department to calculate the tariff which each person was obliged to pay for food and lodgings. Periods of absence or hospitalisation, often refined to hours, are noted, as they affected messing charges.

Re-peopling Bonegilla Online 26 PART 4

Occupational potential codes

Occupational potential codes appear sometimes on the cards as destinations. Most of these codes are now indecipherable. It would require diligent detective work on the records of the Commonwealth Employment Office to make sense of them. Employment officers used the codes to complete detailed report forms. An example of the statistics compiled by the officers of the Commonwealth Employment Service can be found in ‘Monthly report on the employment situation, April 1968, Department of Labour and National Service (A2567, 1962/169, screen pages 6 to 13).

Perhaps the most readily available help can be obtained online from a lengthy table of employment categories in the Commonwealth Employment Service, ‘Displaced Persons Policy and Procedures’ at A434, 1950/3/13, screen pages 357 to 395. It lists ‘occupational potential’ codes summarised in a table that indicates most common sub-categories and the numbers of males and females placed in them. By 1949 most men were unskilled manual labourers and farm labourers; most women were domestics. By the 1960s Australia was receiving more skilled migrants. The occupational potential categories would have been more refined in the 1960s than those listed for displaced persons. There is another item on occupational potential listed on RecordSearch, but it again is for displaced persons and is not online (MP1722/1, 1949/23/5630).

Amateur cryptographers might try to find other patterns in the written and coded destinations. At this stage we have not been able to determine exact meanings. We would be pleased to receive further information on such codes. To illustrate something of the unknown we note the code EL 6339 used to indicate Ludwick Kruselnicki’s placement as a labourer with the Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board. That coding does not seem to fit the categories listed here.

Research Guide Part 4 27

7000

6000

5000

4000

3000

54 M 241F

Common occupation category code With sub-category codes; numbers placed in 1949 M (male) F(female); and occupation examples 0000

2000

1000

Protective service organisations Other service organisations, not private household

Unskilled manual workers

Manual workers not classified according to skill

Skilled manual workers

8000 Rural, fishing and hunting

451 M 773 F

7000 barbers hair, placed 11 M 36 F 7200 cooks, Placed 138 M 152 F 7221 domestic service, 453 F 8,950 domestic servants, Placed 236 F

28 M

5970 M 2251 F

2,216 M 203 F

No sub- categories 6302 policeman 23 M

M 244 F

Professional and semi- professional Administrative or financial

1,362 M 313 F

1,079 M 442 F

Private domestic service organisations Placed 2475 M 44 F

Example Sub-code 595 farm labourers, placed 1,942 M

4110 building labourers, placed 484 M

3330 motor engineers, 709 M 3312 electrical mechanics, placed 315 M

2120 typists, stenographers, private secretaries, placed 296 F

1000 school teachers, placed 179 M 139 F

Adapted from ‘Occupational potential analysis displaced persons scheme, Department of Labour and National Service, August 1949, Commonwealth Employment Service, ‘Displaced Persons Policy and Procedures’ at NAA, A434, 1950/3/13, digitised screen pages 357 to 395.

Note the high numbers placed in category codes 5000, 4000 and 0000.

Re-peopling

Online 28 PART 4

Bonegilla

▄

Exploring Further

National Archives of Australia

NAA provides help with:

• researching family history https://www.naa.gov.au/explorecollection/search-people/researchingyour-family

• searching immigration records https://www.naa.gov.au/explorecollection/immigration-and-citizenship and (Fact Sheet 227) https://www.naa.gov.au/help-yourresearch/fact-sheets

• name searches https://www.naa.gov.au/help-yourresearch/getting-started/recordsearchoverview/namesearch

• finding out about migrant camps and worker hostels

https://www.naa.gov.au/explorecollection/immigration-and-citizenship/ migrant-accommodation-camps

▄ Note that the NAA provides notes on each series. So, for example, the notes on Series A2559 explain: In 1958 Australia’s immigration requirements were revised. The Migration Act 1958 revised Australia’s immigration entry requirements. The Dictation Test was abolished and a simpler system of entry permits was introduced. In 1966 the Australian government announced that applications for immigration would now be considered on the basis of whether the applicants were: suitable as settlers, able to integrate readily, and possessed skills or qualifications useful to Australia. Assisted passage schemes for non-British immigrants were provided by the Australian government. Documents for each migrant typically include: a medical report, a signed agreement between the migrant and the Commonwealth Government concerning the conditions of migration, a questionnaire concerning trade or professional qualifications, an application for assisted passage and notice of departure either by ship or plane.

NAA has published a book that traces some family histories, Family Journey Stories: Stories in the National Archives of Australia, NAA, 2008. It contains Dr Karl’s story of the Kruselnicki family.

Research Guide Part 4 29

Within RecordSearch

There are more than 20,000 records about Bonegilla available on RecordSearch. Many of them have been digitised.

There are at least four series which contain selection documents prepared before entry to Australia and one contains some staff records:

• Series A2559 contains migrant selection documents for non-British European migrants entering Australia under assisted passage schemes between 1966 and 1973.

• Series A2561 has 82 items which have been digitised and shows what the selection documents included. It relates to the Special Assisted Passage Scheme and an Agreement with the Netherlands covering both 1966 and 1967.

• Series A2560 and Series A2559 include the selection papers for the earlier Non-British European Migrant Selection Assisted Passage Scheme.

• Series A2570 has staff records of eight Department of Immigration employees at Bonegilla.

Eugenie Martek giving ‘practical advice’ to a Spanish newcomer. Martek was employed at Bonegilla from 1951 to 1970, first as a typist and clerical assistant with the Commonwealth Employment Service, and subsequently as a welfare officer with the Department of Immigration. Martek’s records in A2570, Item id 12623185 screen page 21 include a list of duties and an analysis of the kind of counselling migrants required. →

A12111, 1/1965/22/11 Item id12623185

• Name Search (instead of advanced search) may help locate selection papers. So, for example, a name search for Gaita, Romulus, Immigration, 1947-1951 will direct the reader to the family’s selection papers at A12025, 7241, item id 410507.

Another three series show changes to the built form at Bonegilla and changes in the residents.

• Series A12799 at Control Symbol 3, Item id 1110041 includes a history of the migrant accommodation division and explains how it functioned. It was prepared to inform the new Minister, Alexander Downer, in 1958. Close by A12799/8, Item id 1110108 outlines changes to the buildings proposed after the Minister visited Bonegilla in June 1958. The changes were to ‘take away the military camp appearance of the place’ so as to lift the morale of residents.

• Series A12111 contains promotional images taken by government photographers. The Department of Immigration trebled its spending on publicity between 1959 and 1967 and increased its spending on photographs and displays five-fold. Items found within A12111, 1/1965/22/* and A12111, 2/1966/22A/* show how the Department of Immigration publicised improvements made to Bonegilla. (Note the * symbol opens several items).

• Item A466, 1962/65399, Item id 1961247 has monthly reports from the Film and Study Centre which detail the arrival of national groups.

Bonegilla

Re-peopling

Online 30 PART 4

Other resources for tracking people

Bonegilla Migrant Experience: www.bonegilla.org.au

Albury Library Museum: https://www.alburycity.nsw.gov.au/leisure/museum-and-libraries/collections/local-and-social-history/ bonegilla-migration

The National Library has some oral histories: https://www.nla.gov.au/what-we-collect/oral-history-and-folklore

Bonegilla Migrant Centre was my first ‘home’ in Australia: Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/BonegillaWas1stHome

International Tracing Service has details of people in displaced persons camps in post-war Germany: https://arolsen-archives.org/en/

Karen Agutter, ‘Finding your family in the hostel’: https://arts.adelaide.edu.au/humanities/hostelstories/ua/media/39/finding-your-family-in-the-hostel.pdf

Research Guide Part 4 31

PAGE LEFT BLANK DELIBERATELY

Re-peopling Bonegilla Online 32 PART 4

PAGE LEFT BLANK DELIBERATELY

Research Guide Part 4 33

Bruce Pennay OAM

Bruce Pennay OAM