Protecting Human Capital through shocks and crises

Jamele Rigolini • Sarah Coll-Black • Rafael De Hoyos Navarro • Ha Thi Hong Nguyen

Jamele Rigolini • Sarah Coll-Black • Rafael De Hoyos Navarro • Ha Thi Hong Nguyen

Protecting Human Capital through shocks and crises

How lessons learned from the COVID-19 response across Eastern Europe and the South Caucasus can be used to build better and more resilient human development systems

1

Jamele Rigolini • Sarah Coll-Black • Rafael De Hoyos Navarro • Ha Thi Hong Nguyen

ECA – A shaky trajectory towards prosperity

Growth and poverty reduction have stagnated following the 2008 financial crisis

Turkey

New EU Member States

South Caucasus

Russian Federation

Eastern Europe

Western Balkans

Source: Authors’ calculations from World Development Indicators (left) and World Bank PIP Database (right). Note: Non-EU ECA excludes HIC but includes Russia.

crisis Post-financial crisis 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% % Population below $6.85 / Day Poverty reduction EAP LAC MENA EU non-EU ECA

Post-financial

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% Percentage

per

GDP

capita (PPP) with respect to EU

Non-EU ECA EAP

2

ECA – A shaky trajectory towards prosperity

Crises, conflicts and shocks are on the rise

Financial Crisis

Invasion of Ukraine COVID

Inflation and Energy Crisis

Regional conflicts and tensions

Natural disasters (Earthquakes, Floods and Droughts)

Higher within-country polarization and instability

3

Human Capital - a foundation for prosperity – is often a victim of crises

School closures affect learning outcomes and students’ lifetime labor income – especially among the poor and vulnerable

Lockdowns and disruptions in health services affect nutrition, mental health, child development and the health of people with NCDs and pre-existing conditions

Crises and shocks also affect labor markets, with disproportionate impacts on youth (an the vulnerable) and leaving long-term scars

Human capital is a long-term investment, and frequent emergencies take away the focus on the need to nurture and invest in it

4

This Report: Learning from the COVID-19 response to better prepare and protect Human Capital from shocks and crises

• The report focuses on the COVID-19 response in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine

• It covers the health, social protection and education sectors

• It takes a forward-looking approach – lessons learned can improve response to many future crises in the region and beyond

5

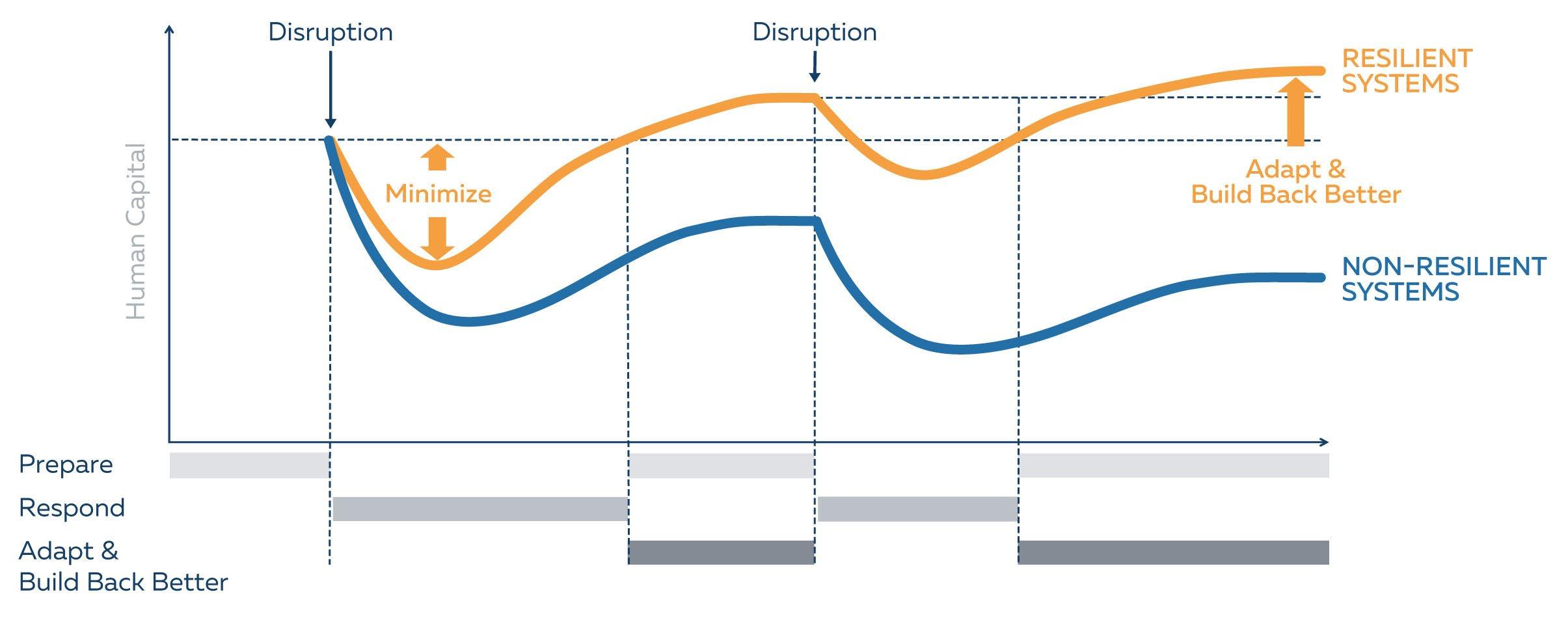

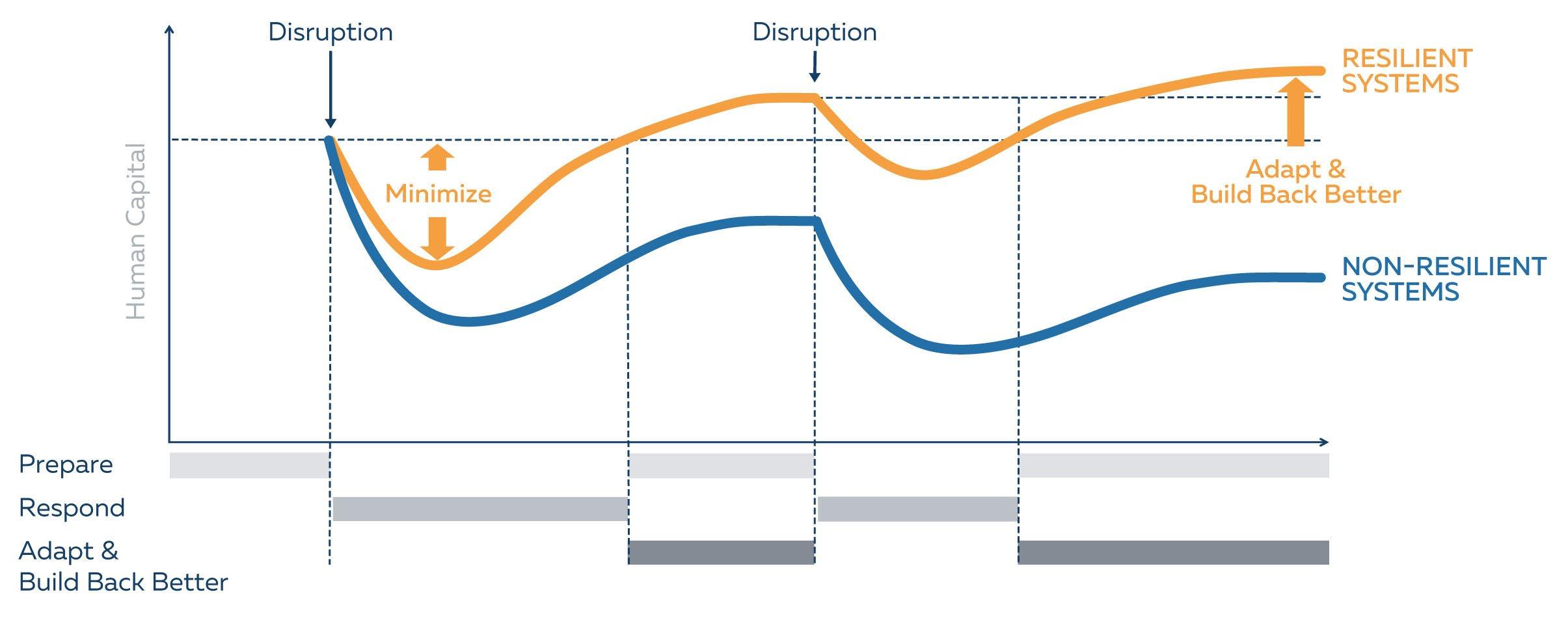

What is resilience?

For the purposes of the report:

6

The ability to protect human capital and the livelihoods of poor, vulnerable and middle-class households during shocks and crises

What drives people’s resilience?

7

What drives people’s resilience?

Resilience of services and systems

This report

8

Resilient vs non-resilient systems

9

The pillars of resilient systems

Delivery Data

Financing Governance & Design

& Information

Prepare Respond Adapt & Build Back Better 10

What do resilient systems look like?

Health (Governance & Design). UK and Italy were severely affected during first wave – but learned and boosted resilience by:

Strengthening monitoring systems

Using / establishing of scientific advisory groups

Providing sufficient and stable funding

Implementing innovative approaches to health workforce management (i.e. skill-mixing)

Implementing efficient vaccination programs (UK: 75% of adults with 2 COVID doses within 8-9 months)

11

What do resilient systems look like?

Social protection (Delivery). Adaptiveness of legislation and delivery tools helped effective and rapid response:

Ukraine: online applications and case management through Diya platform

Chile: effective use of Household Social Registry to rapidly identify and pay benefits to 73% of population in a few months

Australia: use of a pre-existing single delivery structure, Service Australia, to enroll beneficiaries and deliver different benefits

12

What do resilient systems look like?

Education (Data & Information). Denmark and France made effective use of data to guide policy decisions:

Denmark: regular, online assessments of student learning informed returning dates to schools and partial openings

France: use of learning assessments and demographic data to identify learning gaps; reduction of class size in selected schools; use of surveys to assess mental health and home situation during confinement

In both countries, monitoring helped design support measures for students lagging behind

13

Learning from the COVID-19 response in Eastern Europe and the South Caucasus

14

COVID-19 significantly affected the region

Between 300 and 400 thousands excess deaths by January 2023

GDP dropped by more than 5 percentage points in 2020, and remittances by up to 40 percent

With the exception of Ukraine, poverty estimates increased between 1.4 and 5 percentage points in 2020

Impacts were mitigated by fast and ambitious responses…

…generating an opportunity to learn and better prepare for future crises (this report)

Economic activity bounced back quite significantly in 2021 but…

15

Human capital impacts are not over

Full school closures ranged from 63 to 205 days - with some students even forgetting what they had learned

Impacts have been particularly heavy on poor students with inadequate learning environment at home

Limited measures have been taken to close crisis-induced learning gaps

Authors’ imputations based on actual school closures and learning loss studies compiled by Patrinos, Vegas and Carter-Rau (2022).

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 1.2 Croatia Armenia Kazakhstan Uzbekistan Albania Kyrgyzstan Moldova Ukraine Bosnia and… Bulgaria Montenegro Georgia North Macedonia Romania Serbia Turkey Poland Azerbaijan Learning loss (Years) Estimated learning losses from full school closures

16

Human capital impacts are not over

Essential health service disruptions (18 months into the pandemic)

Deferred treatments have been substantial, at times with longlasting impacts

Impacts on children (reduced vaccinations / antenatal visits; nutrition) remain to be assessed

Hospital Inpatient Services

Appointments with Specialists

Emergency, Critical and Operative Care

Community Care

Rehabilitative and Palliative Care

Deferred treatments are both a result of Government policies and fear of being infected

Primary Care

0% 50% 100%

Percentage of ECA Countries

Source: Global pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic, Round 3, 17 ECA countries.

17

Learning from the COVID-19 response: Health

18

Country responses

Reduction of social mobility and communication campaigns

Establishment of intersectoral steering groups

Expansion of testing and contact tracing capacity; use of health information systems to monitor the spread of the pandemic

Optimization of hospital care and expansion of the healthcare workforce

Acquisition/production of medical equipment and vaccines / pharmaceuticals

Financial measures to alleviate the cost of COVID-related care

19

Many hospital beds but not enough equipment

Weak primary care networks with scarce human and financial resources

Crisis planning and pandemic preparedness varied substantially; not all countries conducted regular health sector drills

Severe staff shortages, worsened by the pandemic

High levels of mistrust / vaccine hesitancy

Challenges

20

Learning from the COVID-19 response: Social Protection

21

Country responses

Use of social assistance, social insurance and employment programs to support people who lost income or were seen to be vulnerable

o Horizontal/vertical expansion of last resort income support; payments to vulnerable children, disabled, and pregnant women

o Expansion of unemployment insurance, wage subsidies and pensions

Use of subsidies to cover utility bills, food purchases and tuition Expansion of public works

Expansion of social services (e.g. bringing food to isolated elderly)

22

Country responses

The spending level and composition of the response varied substantially across countries – but the social assistance response remained modest overall

Social Assistance (other than Utility)

Unemployment Benefits

ALMPs (other than WS) + Tax Rebates

Wage Subsidies (WS)

Utility Subsidies

0.0% 0.5% 1.0% 1.5% 2.0% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% Armenia Azerbaijan Georgia Ukraine Level of spending (% GDP) Composition of spending

Pensions

23

Limited preparation affected the effectiveness of the response

o Some countries had to establish new, ad hoc institutional structures to manage their overall COVID-19 response

o Emergency funding was often channeled to pensioners / formal sector because of greater voice and limitations of social assistance

Social assistance responses often provided more aid to existing beneficiaries, but limited the expansion to those made poor(er) by the pandemic

Social Assistance application rules were not always eased, and communication campaigns were limited (in contract with employment programs)

Challenges

24

Learning from the COVID-19 response: Education

25

Country responses

Schools were fully closed for 64 to 205 days

26

Country responses

School closures substantially affect learning – especially of the poor and vulnerable

27

Country responses

Remote learning based on a combination of online platforms and media broadcasts, synchronous and asynchronous instruction

Subsidized / free internet access, online textbooks, (devices), and access to distance learning applications and platforms

Development / expansion of online teacher training and support

Some psychosocial and mental health support

28

Countries failed to learn from emerging evidence to adjust policies and minimize learning disruptions

o Schools were closed for excessively long

o Limited efforts to address pandemic-related learning gaps

Limited support to teachers in terms of connectivity, equipment and training

Poor connectivity and learning environment at home & learning fatigue

Remote learning, even if effectively implemented, is a poor substitute to face-to-face learning

Challenges

29

Learning from the COVID-19 response: Preparing for

the next crisis

30

Prepare, prepare, prepare

The importance of preparing for future crises cannot be stressed enough

Most countries have disaster risk management policies, but they neglect the human development sectors:

o The health sector should have effective preparedness plans, monitoring systems, crisis-specific legislation/financing, and hospitals should conduct regular emergency drills

o In social protection, legislation should enable programs to be rapidly scaled up, with relevant changes to both eligibility and benefit rules set out in advance

o In education, alternative learning modalities should be designed and piloted regularly, and student performance should be more closely monitored

31

Respond with an eye to the future…

Systems that can deliver quality services in normal times tend to respond better to crises:

Effective public health systems are better equipped to monitor the spread of a pandemic, and a trained and qualified health workforce needs less additional support during stressful times

Social protection systems that have invested in administrative tools to identify people in need of support were able to identify and enroll new beneficiaries more rapidly

Education systems with many students with poor learning outcomes faced a higher risk of students falling further behind during school closures

Let’s not lose sight of the need to strengthen human development systems by protecting, financing, and improving delivery

32

…and continue responding after the crisis is over

While a crisis may be over, crisis-induced human capital gaps are often not

o Learning losses are massive, deferred medical treatment has affected the health of many people, and precarious employment may leave long-term scars

Proper crisis responses must support people in the medium to long term

It is essential to invest in remedial education, catching up on the provision of medical care, and favor youth insertion in the labor market

33

Explore further the potential of digitalization

Digitalization enabled more effective responses

Health information systems, social registries, online learning and training platforms, integrated M&E systems, and payment and learning/training platforms improved substantially crisis responses

Further Digitalization can support more effective delivery in both normal and crisis times

However, digitalization is sustainable only if systems are properly maintained and updated, and if people are digitally literate

Digitalization needs to be gradual and accompanied by training and governance / legislative reforms

34

Protect Human Development financing

Human capital spending in the region was (mostly) low to begin with – and the COVID-19 pandemic has put further strain on public finances

With recurrent crises hitting the region, it is vital to protect as well as improve fragile human capital endowments to support greater productivity and prosperity

One should not lose attention to the long term - it is not the moment to let spending fall even further

35

Improve governance and response designs

In SP, level and length of support should be tailored to needs and vulnerabilities

o Across SP choose which program to expand, within programs choose how to expand

In Education, policy responses (i.e. school closure policies) should change over time to incorporate emerging evidence

The use of behavioral approaches could help improving the population’s following of public health policies

Poorly designed responses – even if delivered effectively – can substantially limit impacts

36

Develop cross-sectoral, household-centered approaches

Putting the household at the center requires however a solid intersectoral governance and M&E structure

o E.g., Lockdowns require not only income support measures but also measures to support parents, children, and teachers with distance learning and remote working

Maximizing response impacts also requires considering tradeoffs across sectors and programs

Disaster response is about helping people cope with crises and shocks

37

Boost data, information, and evidence-based responses

During a crisis there may be little time for evaluations – but monitoring systems should be already in place to support evidence-based response decisions

o Some crises (COVID-19) can also last for a long time – reinforcing the need for evidencebased decisions

COVID-19 responses could have been more effective if regularly evaluated and improved

o Large-scale student assessments would have enabled the design of more effective responses

o The design of social programs changed little over time

38

Investing in digitalization, monitoring and evaluation can – again –support both long-term system strengthening and resilience

Thank you

Jamele Rigolini • Sarah Coll-Black • Rafael De Hoyos Navarro • Ha Thi Hong Nguyen

Jamele Rigolini • Sarah Coll-Black • Rafael De Hoyos Navarro • Ha Thi Hong Nguyen