16 minute read

Tips on Resolving Pre-Purchase Inspection Disputes

How are pre-buy inspection disputes in pre-owned business aircraft deals resolved? Better still, how are they avoided? Chris Kjelgaard receives insights from an aviation legal counsel, a technical inspection expert, and an aircraft broker and buyer’s agent...

Buying a pre-owned business aircraft is an expensive and complex proposition, as you would expect when the purchase of such a sophisticated and valuable asset is involved. For the seller and buyer alike, various pitfalls and technical issues found during the prepurchase inspection can add substantially to the cost and time needed to close the deal.

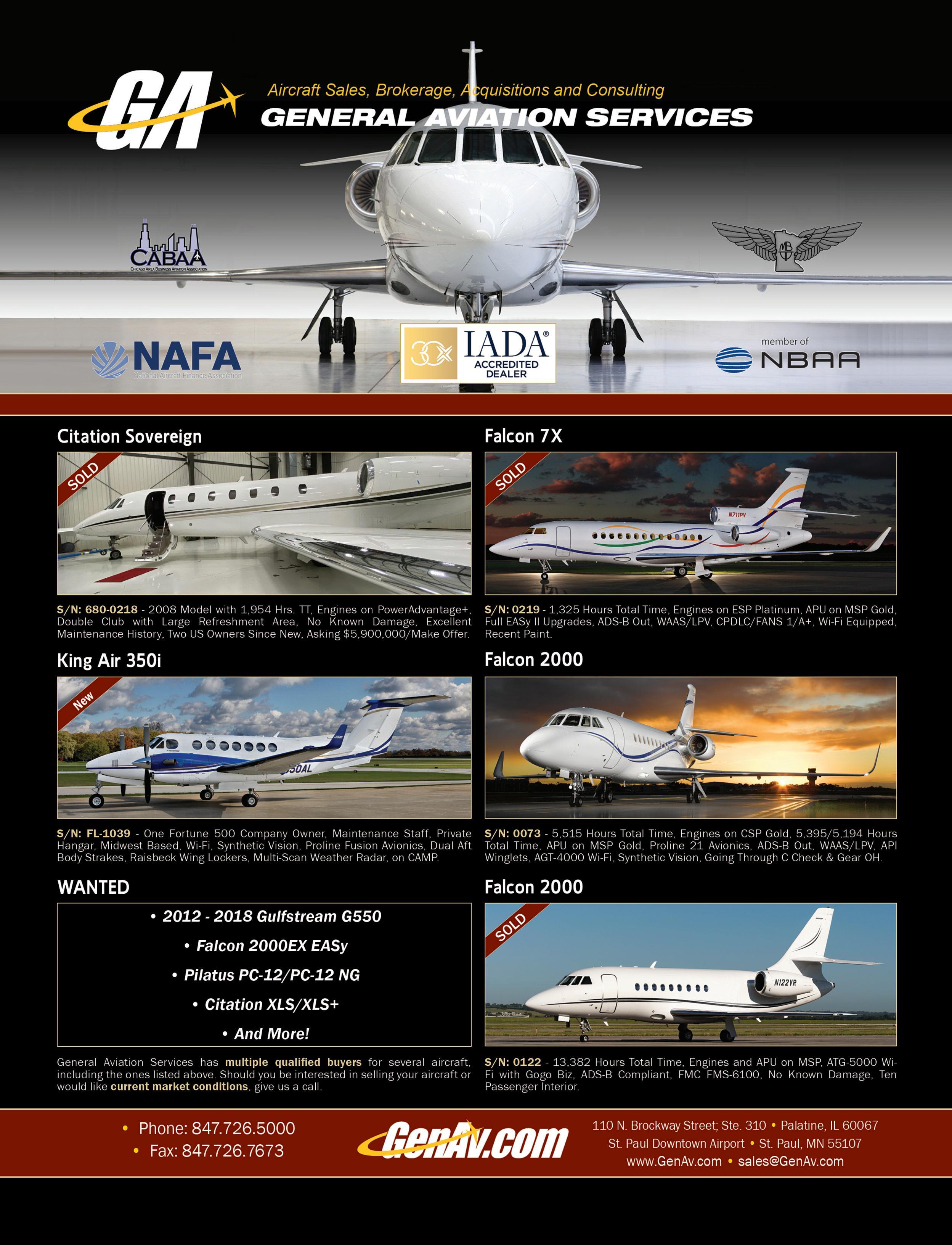

Advertisement

In some (though not many) cases, differences of opinion between the two parties or unexpected condition problems can cause the desired transfer of ownership to derail completely.

It is in the interests of both the seller of the aircraft and its putative buyer — and their respective intermediaries — to do their utmost to minimize the chances of a critical dispute arising between the two principals when the pre-buy inspection is performed. If such a dispute does arise during the inspection, it is equally incumbent upon the parties to do as much as they can to resolve the dispute amicably, or at least successfully.

The simplest way to ensure that a pre-purchase inspection dispute is resolved is to take steps to prevent it from arising at all. That’s best accomplished when the transaction principals and their representatives make sure that the purchase agreement is very comprehensive, detailing the agreed specifics of every facet of the deal.

These will include the identity of the inspection facility that will perform the pre-buy inspection; what the parties will accept as evidence the aircraft is fully airworthy; the expected duration of the transaction; and the remedies the seller and buyer can seek if the other principal defaults.

The contract will also include a host of other terms and conditions which will all bear on the deal being able to close successfully.

The Letter of Intent Stage

Negotiation of the basic terms of the purchase agreement should begin even at the initial Letter of Intent (LOI) stage of the deal, before the principals agree upon the definitive purchase contract between them, says Scott Burgess, Founder of Fort Lauderdale-based Aviation Legal Group.

One critically important point which must be specified in the contract is the identity of the facility which will carry out the pre-purchase inspection.

In agreeing which facility that will be, the deal’s principals must ensure that the facility is fully certificated to perform the inspection and to carry out any repair work required to render the aircraft airworthy under the terms of the agreement, Burgess adds.

This is all the more important when the acquisition involves the aircraft being deregistered from one country’s registry, and then put on another nation’s register. For instance, if the aircraft is on the Mexican registry prior to its sale, but will be placed on the FAA registry in the US by its new owner, and the seller and buyer agree that the pre-purchase inspection is to be performed by a facility in the US, then both must ensure the facility is certified by the Mexican airworthiness authority to perform that inspection, and render the aircraft airworthy before it can be deregistered from the Mexican registry.

If the parties fail to ensure the facility is properly certified, later finding that it isn’t, then following the inspection the aircraft would be unable to return to service, since the Mexican authority would no longer consider it airworthy, Burgess warns. This would require the aircraft to be completely re-certified, at considerable cost and time to the seller.

However, in most cases, transaction principals make sure the facilities they select to perform prepurchase inspections are properly certified by having OEM-authorized service centers carry out the work, says Jim Mitchell, an Executive Sales Director for Elliott Jets. And in many other cases, transaction principals choose large, highly reputable MRO shops to handle their pre-buy inspections.

With that said, it is still vital for transaction principals to confirm for themselves the suitability of the inspection facility they want to use. “They need to do due diligence, in terms of obtaining references regarding the quality of the work [the facility performs], even if it is certified by the FAA,” Mitchell adds.

The Scope of the Inspection

Another fundamentally important item the purchase agreement must cover is the agreed scope of the pre-buy inspection. This can vary, and the primary implication of the agreed scope of the inspection is the consequent cost it will involve — and repairing any airworthiness discrepancies it finds — to the buyer and the seller, notes Burgess.

The buyer is responsible for the cost of the prepurchase inspection — the buyer always has to pay the facility in advance of it being performed — and the seller is responsible for the cost of repairing any discrepancies found which need to be fixed in order to make the aircraft airworthy.

Pre-purchase inspection scopes can vary from a Level 1 inspection — costing the buyer about $15,000 and the seller potentially $20,000 in correcting discrepancies found — to a Level 4 inspection, says Burgess.

The much more detailed and comprehensive Level 4 inspection will cost the buyer about $110,000 (which again the buyer must pay for upfront) and could result in the seller facing repair costs as high as

$300,000-$500,000, especially if the inspection finds substantial corrosion in any part of the airframe.

Most inspections typically run in the $25,000$50,000 range, according to Mitchell. Owing to their potential exposure to high repair costs, sellers tend to prefer the scope of the inspection to be limited. On the other hand, if buyers can afford the extra cost, they prefer the scope of the inspection to be more comprehensive, unearthing repairs which are hard to find, but are necessary to remedy to ensure airworthiness.

Both parties must ultimately agree to a given inspection scope, but are aided by the fact that most business aircraft OEMs have developed standard recommended pre-purchase inspection tasks, according to Lee Rohde, President and CEO of Essex Aviation Group, and an experienced aircraft technical inspector.

Rohde strongly recommends that each purchase agreement should include an exhibit in the form of a written, detailed proposal from the facility that will perform the pre-purchase inspection as to exactly what inspection work it plans to carry out. He says it is also important for the contract to include agreed definitions of the scheduled maintenance work that has been performed and/or needs to be carried out on the aircraft in order for the sale to close — a condition that requires negotiation by the principals and their intermediaries.

In addition to specifying the scope of the pre-buy

inspection to be performed (and covering the need for maintenance document inspection too, according to Mitchell), the contract must also identify any damage history attached to the aircraft, Rohde says. It must detail any specific work the parties agree to have performed to inspect the previously-damaged areas, along with the associated repairs completed on those areas in order to make the aircraft airworthy previously.

While the terms and conditions specifying what must be inspected and repaired to ensure airworthiness can leave “gray areas”, Rohde says that if an issue arises over the scope of the inspection, the inspection facility will, in any case, have required both parties to execute the proposal containing the

2004 Citation CJ2

5,800 Hours, Engines enrolled on Tap Elite Blue, Airframe enrolled on Proparts, Winglets, WiFi, 2015 Paint, 2017 Interior, Make Offer

2000 Challenger 604 S/N 5447

15,286 Hours, Engines Enrolled on GE On Point,APU Enrolled on MSP Gold,Airframe Enrolled on Smart Parts, GoGoATG-5000 WIFI, Make Offer

work scope the principals specifically agreed and the facility followed.

Once the inspection has been performed and the facility reports its findings, disagreements can arise between buyer and seller as to what constitutes a discrepancy that must be repaired, notes Burgess. If the parties remain unable to agree on the point, then the purchase agreement may default and the entire transaction unravel.

However, in most transactions, the parties agree for the inspection facility to be the deciding party in ruling on what is and is not an airworthiness-related discrepancy, says Rohde. This can help avoid potentially deal-compromising disagreements between buyer and seller on what the seller needs to

have fixed in order to meet the airworthiness and delivery condition requirements of the transaction.

Other Important Contractual Areas

Purchase agreements also need to cover several other important contractual areas — so it’s important that they are well defined in the initial LOI as well as in the formal contract itself, says Mitchell.

According to Mitchell, Elliott Jets is finding that the parties to proposed aircraft sale transactions are increasingly specifying at the LOI stage what rights each principal has to reject the deal, and defining the circumstances that create those rights.

Probably the most important area of all, however — even at the LOI stage — is the definition of aircraft and engine internal corrosion and material damage, which, if found by inspection to be substantial as defined by the terms of the contract, can cause the entire transaction to unwind, according to Rohde.

If the buyer and seller don’t reach agreement on the definition of material corrosion and/or damage the transaction will allow for before triggering default, this forms another hurdle the deal may fail to clear.

Not only can the finding of significant corrosion cost the seller $200,000-$300,000 to repair, but the repair will also take up to six months to perform, Mitchell says. Just as important, the entry in the aircraft’s logbook covering the repair will be so extensive that it will appear to any future buyer that

the aircraft previously sustained significant damage, making it harder to sell.

Airframe and engine corrosion is one of the very few causes — and is probably the leading one — of used-aircraft sale transactions failing to close, he says. Fortunately it is “fairly rare” for the pre-buy inspection to find an amount of airframe or engine corrosion so significant that it can cause the deal to unwind, he assures.

There are three major causes of corrosion in business aircraft. One is leaking of fluid from the aircraft’s lavatory. The second is frequent or prolonged operation in climatic environments containing high levels of salt and water (e.g. intercontinental, over-ocean flying). And the

third is inadequate sealing of aircraft surfaces, which can cause corrosion in critical structural parts such as the vertical stabilizer spar.

Burgess says the purchase agreement should also cover whether or not the pre-purchase inspection will include borescope inspections of the aircraft’s engines and — if it has one — it’s Auxiliary Power Unit (APU).

If the engines and APU are subject to an hourly maintenance program, the program’s administrator usually will not cover the cost of unscheduled borescope inspections, and probably also will not cover the cost of any repairs found during such inspections, Burgess says.

Borescope inspections allowed by hourly maintenance plans typically are limited to inspections of the front sections of the engine and its exhaust nozzle, and are intended to rule out the presence of foreign object damage, he explains.

Another important area the principals need to agree, and include in the purchase contract — and which Mitchell says crops up fairly commonly in situations where pre-buy inspections have identified repairs that need to be made — is whether any replacement parts required must be new or if the buyer will allow replacement with used, properly documented parts.

Allowing replacement parts at all, rather than specifying repairs be made to existing parts, is also a contract detail that can become a point of contention between seller and buyer, notes Rohde.

Approving the use of used, fully documented, serviceable parts as replacements can create massive repair-cost savings for the seller — more than half a million dollars in one recent case with which Mitchell was personally acquainted — but can prolong the duration of the transaction fairly significantly, given the time it can take to find suitable used parts.

Inspection Slots and Final Steps

In today’s overheated pre-owned aircraft market, all three experts interviewed for this article agree that one of the most important details of the deal — whether or not it is covered in the purchase agreement — is trying to obtain a slot in the near term for a certified facility to perform the pre-buy inspection of the aircraft.

No matter which facility is chosen, in today’s market it is very difficult — bar the unexpected cancellation of another inspection making a near-term slot suddenly available — to obtain an inspection slot within 60 days.

Mitchell notes that in the business-aircraft sales arena, a long-held maxim is that “time kills deals” — so being unable to find a near-term slot for a pre-buy inspection could potentially prejudice a deal being closed.

Last but not least, the contract should detail the final steps of the transaction after the pre-purchase inspection has been completed, after any required repairs have been made, and after the principals have agreed that the aircraft condition terms of the sale have been met, says Rohde.

These last steps should specifically cover whether or not a post-inspection final test flight is required, and if any other positioning flights — other than the final delivery flight — are allowable, he says. If the aircraft has to be flown to another state or national jurisdiction for sales-tax reasons, the buyer usually bears the cost of that flight.

“The bigger theme is that, the more you lay out the specifics of what can and can’t happen, the better,” he says.

It is the buyer’s responsibility — usually handled by the technical inspector the buyer hires — to perform the technical acceptance of the aircraft, and approve acceptance following the pre-purchase inspection and remedial repair process, according to Rohde. However, “the larger percentage of sellers will be actively approving [required repairs] during the inspection,” he says, even though the seller isn’t legally required to approve anything until after the inspection ends.

Communication is the Key

Given all of the important required contractual details above, it may appear that transactions involving sales of used business aircraft frequently fail to close. But in reality

PHOTO COURTESY OF ELLIOTT AVIATION

it is rare for deals to fall apart, the experts interviewed for this article agree.

“Most people are so invested in the deal that they want the deal to close,” remarks Rohde. “It’s pretty rare for deals to fall apart if everything is covered in the purchase agreement.”

But while the principals’ mutual desire to complete the deal may be the most compelling underlying reasons why relatively few used aircraft sales fail to close, a successful outcome involves a great deal of hard work, coordination, and communication by the principals’ intermediaries to make sure the transaction proceeds to the close.

In every transaction there is always a need for the three major parties involved in the pre-purchase inspection process — the two principals along with their representatives, and the inspection facility — to communicate clearly and often, says Rohde.

The inspection facility should communicate its findings from the inspection as it progresses. “Having people on-site on a regular basis helps the process too — it helps things move along,” he adds.

In fact, says Mitchell, the parties should “continuously communicate” during the pre-buy inspection process — particularly the service center performing the pre-purchase inspection. But it isn’t always easy for the principals and their representatives to make sure this happens.

“From the service center’s viewpoint, they are all extremely swamped [currently] and they are struggling with communication,” he says. “They are dealing with 10 to 12 of these projects at a time, some of them massive. So, from the buyer’s and the seller’s viewpoint, they have to be patient but also persistent.”

Usually, when areas of disagreement arise between the principals, they should let their expert intermediaries reach mutual consensus first on possible solutions and then — after the intermediaries advise them on what those solutions might be — agree on a final decision, Burgess suggests. “In my experience, some things are better for us lawyers to talk about and there are some things where it’s best for the principals to talk about,” he says.

The Best and Worst Courses

In most cases, the best course is “to allow the parties’ representatives to narrow the issues and find out the cost associated, so the principals can make the decision,” Burgess suggests.

Each principal’s legal counsel and/or technical representative “will notify the client there is an issue, and will work through it and present alternative solutions. There is always more than one way to

resolve an issue, some more palatable than others.”

The least palatable option will be going to court to try to resolve a dispute, according to Burgess. “Litigation is the least effective and least efficient means of resolution,” he stresses, taking time and lots of money. The result is very rarely appreciated by either principal. While the court case continues, neither party has the use of the aircraft.

Often it is best for the representatives to remind the principals that “there is cost to both parties if the transaction doesn’t consummate,” Burgess adds. Time mounts up; the aircraft isn’t available for service; and the transaction costs increase.

While each principal would like to feel they are the “winner” of the transaction, “sometimes the best solution is compromise when neither is particularly happy — but it will be behind you, and you will have certainty.”

If the deal fails to close because of a dispute over pre-purchase inspection findings, “the seller has got to fix the aircraft anyway if the buyer walks away,” says Rohde. Unless the seller subsequently decides to keep the aircraft, the seller will have to begin the sale process all over again, incurring substantial new costs in doing so.

Transactions flow best when the seller is a “good” seller and “wants the buyer to have a good, clean airplane,” Rohde summarizes. At the same time, it also helps the deal for the buyer to demonstrate flexibility and understanding — a point a good technical representative and legal counsel will make to the buyer.

“We tell them there are costs involved in these transactions. If the seller has big [repair] costs, we ask the buyer to be sensible and fix small [nonairworthiness] discrepancies after the close,” at the buyer’s own cost, he adds.

Sellers should realize that “a ready, willing and able buyer who really wants the aircraft is a lot better than another buyer, even if that buyer is willing to pay more,” says Burgess. ❚

CHRIS KJELGAARD

has been an aviation journalist for 40 years, with a particular expertise on aircraft maintenance. He has served as editor of ten print and online titles and written extensively on many aspects of aviation. He also copyedits most major documents published by a global aviation industry trade association.

MAKE MORE INFORMED BUYING & SELLING DECISIONS with AvBUYER.com