Mastering the Art of Compression in Healing Venous Wounds

Editorial Summary

The

burden of

is significant to healthcare systems around the world. In this article,

is provided, identifying areas of challenge to the wound care clinician.

consideration and other challenges are considered. The mechanism of

compliance, as well as

compression is detailed, with consideration for comfort and consistency. A detailed look at the mechanism of establishing compression is included; finally a conversion of data into real practice is presented.

Introduction

This article will discuss the burden of caring for patients with venous leg ulcers. We know just how expensive and costly the impact for treating venous leg ulcers is, not just for the patients but also for the payers. It’s at least 1 bn dollars annually to treat these patients. For those of us that treat the patients, we know that they miss a ton of work every year. My patients are employed in areas such as retail, and the physical nature of this type of work can exacerbate the problems with their venous disease. These patients miss on average 14 days of work per year. The cost itself for the patients can be about $18,000 a year; many of my patients simply cannot afford this.

Compression

Looking at the actual incidence rate for Medicare itself, it affects about 2.2% of the population, and around 0.5% have private insurance. Reflecting on my own practice, many of my patients who have venous leg ulcers are not even on Medicare, and are on the Medicaids. I am seeing more and more patients who are in their 30s, 40s and 50s, so the actual incidence is much higher than 2.2%, and is going to be rising in the Medicare population as the burden increases as patients age into the Medicare age range.

Let us consider the objective truth. Looking at the source of truth for all of our evidence, we go to the gold standard. This is using the Cochrane database, which has all the meta-analyses for the evidence. We also look to resources like those provided by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

Mr Evan Call

We know that compression increases ulcer healing rates when compared to no compression. We also know that all of the data tells us that multi-component systems are more effective than single-component systems. Similarly, multi-component systems containing an elastic bandage appear to more effective than those containing a mainly inelastic consistence. So, two-component bandage systems appear to perform as well as the four layer systems, as long as the two-bandage system components have

Mastering the Art of Compression in Healing Venous Wounds

“With these factors, we as clinicians have many challenges to overcome. We need to apply both long-stretch and short-stretch, we need to consider the comfort of the patient, and we need to ensure that the therapy is working whether the patient is at rest or active. In short, we need to tailor therapy to the patient’s lifestyle so that they can continue as normal.”

at least an elastic bandage. Patients who do receive the four-layer bandage heal faster than those who have the short-stretch bandage in and of itself. The inelastic bandage and the short-stretch bandage are more commonly known as the Unna’s boot, the more traditional, or as I call it the ‘old-school’ methodology of applying compression.

The Unna’s Boot

So, what are the present challenges that the application of compression can present? The stretch is the key issue here. The Unna’s boot has been widely used in, for instance, vascular surgery because this methodology has been passed down for decades.

An Unna’s boot is a paste bandage that does not have much give or stretch, hence the term ‘short-stretch’. It is applied wet and hardens into cast or a stiff bandage, and essentially requires the patient’s calf muscle to compress against the stiff bandage, giving the ‘squeeze’ of the veins in the cast, forcing the venous return back up to the heart. This implies that the patient would have to be an active patient; in a patient who is non-ambulatory and more sedentary, this is simply not a good option. These patients need more of an elastic component which is going to provide more of a continuous squeeze on the leg, if the calf muscle pump simply is not working. We must match the stretch to the patient’s lifestyle and activity level.

The next issue is compliance. We should consider some of the most common aspects that patients dislike about wearing bandage systems on the lower leg.

They are hot. I work in Washington DC; it is known as ‘the swamp’, not just for political reasons but because it’s around 110 degrees here in August. It can be very humid and uncomfortable. In conditions such as these, the last thing a patient will want is to do is wear a

multi-component bandage system that has lots of layers in padding. Due to the discomfort, the patient is likely to scratch the area and push or shift the bandage down, possibly leading to the point where the patient decides to take it off, compromising their treatment.

The other challenge here are unique patient factors. Not all legs are shaped the same, and not always shaped the same on the same person. We may have one person who has a primary lymphedema, or post-thrombotic syndrome, on one limb but not the other; or the limbs may simply be different sizes. It can be very challenging when wrapping both legs to achieve a consistent application on both sizes.

With these factors, we as clinicians have many challenges to overcome. We need to apply both long-stretch and short-stretch, we need to consider the comfort of the patient, and we need to ensure that the therapy is working whether the patient is at rest or active. In short, we need to tailor therapy to the patient’s lifestyle so that they can continue as normal.

One of the most important questions I ask my patients is “What do you want out of this experience? What is your goal?” Not all patients will respond that they want to be healed, but they may want to, for instance, go to church. Their goal may be to be able to attend a family function. The patient’s preference should not be optional, we do need to understand what is important to them.

If the bandage system is uncomfortable, itchy or painful the patient is simply not going to wear it. We could see this not necessarily as non-compliance, but rather that we have not fully considered the patient. We also need to address the unique patient factors, making sure that we are wrapping the leg shape correctly, we are considering ankle sizes, that we are not having slippage, and that the nurses are able to apply the bandage systems accurately and

Mastering the Art of Compression in Healing Venous Wounds

consistently no matter what the ankle size, or unique leg shape.

How Can We Overcome This Burden and Address the Need for Better?

What does ‘better’ look like? Firstly, we need to keep things simple. We need a system that features all elasticities, in that it has shortstretch and long-stretch; it works both at rest and during activity; and the same kit needs to work for all different ankle sizes.

Again, we need to consider patient compliance. The system should be as comfortable as possible, breathable, and tolerable night and day.

Also, we must eliminate the variables to ensure that everything is applied consistently, the first time, every time.

Three Principles for Good Compression

This leads us to consider the three principles of good compression:

We need to apply continuous pressure 24/7

We need to ensure consistent pressure application

We need to ensure that compression is comfortable and patients can wear it

Continuous Pressure

What is it that gives us this continuous pressure through the course of use? The short-stretch inner bandage confers rigidity and contributes to comfort; it also absorbs exudates, while contributing to the pressure overall. The outer, long-stretch bandage maintains pressure at rest, it holds the system in place and creates a ‘scaffolding effect’, that holds the whole structure in place on the leg. This continuous

compression effect works up to seven days, and it maintains that therapeutic pressure in all positions, whether lying, sitting, standing, walking or working.

After seven days we see this pressure maintaining the compression where we want it. We had a minimal reduction in that maximum working pressure as time goes on. That means that we achieve a smaller reduction in working pressure over time maintaining that therapeutic compression through the whole wrap cycle. Why do we see this continuous compression?

With the URGO K2 and not with a two-layer system we have a unique kind of ‘work’ that occurs the energy that is put into the tissue when you apply a compression wrap.

The padded short-stretch layer provides 80% of the compression, but because it is padded it also provides excellent force redistribution. This provides the work of compression without the edge effect the reactive hyperemia demonstrating shear that is imparted to the tissue. We want to distribute that force without inducing shear and this is why the padded inner layer becomes so valuable.

The work of compression done by a padded layer dramatically reduces point loads. High loads at the malleolus or at the calcaneus that could potentially injure the tissue if misapplied, are dramatically reduced and we have a much better wrap and force distribution because of this padded layer.

These combine to provide compression without pressure peaks, or the edge effect that creates pain and shear. This improved comfort is all together in place while we have this rigidity of the combination of the short-stretch inner with this outer layer.

The outer layer provides 20% of the compression, it ‘traps’ the first layer and holds it in place in a scaffold relationship. The structure

“What does ‘better’ look like? Firstly, we need to keep things simple. We need a system that features all elasticities, in that it has short-stretch and long-stretch; it works both at rest and during activity; and the same kit needs to work for all different ankle sizes.”

Mastering the Art of Compression in

“With this system, patients had a reduction of reported pain of 28%, together with reductions of pain intensity, and sensations of heat and itchiness. 95% of patients considered K2 to be more comfortable compared with their previous system, and 92% felt it was more comfortable at night. “

holds the wrap up on the leg, so that it is not able to slip down. The friction which interacts between the two layers tie it together and create a compression layer and a scaffold layer that protects the tissue and keeps the wrap in position. It reduces the tendency to slide, or bundle up.

The friction between the two layers creates an effect which achieves what a four-layer system is designed for, with a two-layer system; binding and performance is very similar to that of a fourlayer system.

Consistency

Studies on the pressure consistency of K2 have shown that between 85% and 87% of nurses achieve the therapeutic pressure from the first application, with no prior experience. This is significantly more impressive than other kinds of wraps currently on the market, such as the four-layer bandage systems or Unna’s boot.

Comfort

With this system, patients had a reduction of reported pain of 28%, together with reductions of pain intensity, and sensations of heat and itchiness. 95% of patients considered K2 to be more comfortable compared with their previous system, and 92% felt it was more comfortable at night.

A study conducted into patient compliance with K2, which compared patient compliance in winter and summer, found that 96% of patients returned for follow up visits in winter, and 92% of patients did so in summer. In my own practice, I have also found this to be true. Once the patients are wearing it, they wear it consistently; they are not taking it down, and it is not sliding down. This provides continuous pressure, 24/7, at all different levels of activity. It is possible that 87% of all nurses are achieving therapeutic compression at their first application and then

consistently matching that throughout. The wrap is comfortable, and can be worn regardless of the climate.

Evidence for Performance of the K2 Dual Layer Compression System

Let us look at two studies we conducted to measure the performance of the K2 dual layer compression system, one human subject study and one bench study.

The important starting point for this discussion is understanding the construction of the compression wraps/ bandages studied. The K2 dual-layer compression system consists of two active compression layers; a soft-padded shortstretch inner layer, KTech, that is absorbent and provides a comfortable interface with the body, conferring 80% of the compression pressure; and And a long-stretch outer layer, KPress, which is intended to apply 20% of the compression and maintain the system in place.

Additionally, one of the benefits of the K2 compression system is that both layers include reference points to guide the operator during the application process. The reference points are ovals that convert into circles as the bandage is stretched; this indicates how much the bandage should be stretched and overlapped to provide the desired pressure.

The compression mechanism consists of the interaction of the inner wrap/ layer with the outer layer to provide structure. This occurs particularly well when the inner layer is tied with the outer layer, which maintains pressure at rest and holds the combined system in place. I like to think of this structure as functioning as a scaffold, holding up a temporary structure underneath it, creating rigidity in something like fabric that wouldn’t normally be rigid . This combination makes the assembly even better by the fact that the two layers are elastically contracting into each other.

Mastering the Art of Compression in Healing Venous Wounds

The warp and the weft of the fabric create an interface that reaches into each other’s surfaces like your fingers would when you lay your hands together and your fingers fit between each other. Together, these structures provide continuous pressure and strong structural performance. The strength of this relationship between the two layers is that it provides longterm performance compression. The K2 system is designed to reach 40 millimeters of mercury as the target pressure and stay in place without sliding down or bunching up over seven days. During the seven days, it continues to provide therapeutic compression while lying down, while sitting, and then an appropriate maximal working pressure when a person is up and ambulating.

Bench Study

We set out a bench test study to understand why this continuous compression occurs with the K2 and compared it with a traditional twolayer compression system. Note that in the graph of the load-deflection curves (Figure 1), you see the force at a given deflection/ stretch. The shapes of these curves predict the product’s performance over various levels of stretch. These curves show the amount of energy as the product is stretched. This gives us the understanding that the K2’s performance, at the manufacturer’s instructed stretch indicated by the circle, provides high energy delivery. This shows highly consistent performance of the compression system from application to 7-day use. Looking at the second graph, the outer or second layer applies less compression because there is more deflection with a lower load. This lower force required to deflect (stretch) the wrap applies less of the compression to the tissue, ties the two layers together, and provides a high-level wrap performance. This also creates a unique energy delivery process. The elastic, padded, and absorbent KTech stretch layer provides 80% of the compression. This means that 80% of the

Figure 1: We looked at the engineering of UrgoK2 compared to a traditional 2LB to understand why UrgoK2 provides continuous pressure.

• 2LB comprised of a foam comfort layer (Layer 1) and a shortstretch compression bandage (Layer 2)

• At recommended stretch, UrgoK2 obtained more load and work than 2LB higher work is better for maintaining sustained compression, especially after limb volume is reduced

•

This shows why traditional 2-layer compression is NOT Dual Compression

“Together, these structures provide continuous pressure and strong structural performance. The strength of this relationship between the two layers is that it provides long-term performance compression. “

Mastering the Art of Compression in Healing Venous Wounds

work or energy going into that tissue to reduce the edema comes from this soft, absorbent, cushioning structure. This allows for reduced point loads, evidenced by the observation of reactive hyperemia lines pressed into the tissue when care providers remove a compression wrap. These lines make it obvious that there is an edge of the wrap pressing into the tissue. This creates a potential area of concern for the tissue and the patient’s comfort. The highly cushioned yet compressing inner KTech wrap avoids that point load at the edge of the wrap, and provides compression free of potential injury. This highly compressing inner layer combinedwith the lower compression but retaining outer layer, together combines to provide greater energy application to the tissue. However, with this greater compression, we don’t see the same edge impact; there are fewer pressure peaks and less shear-based pain. Remember, the shear of something twisting on the tissue is what generates pain in compression, so delivery of compression without that twisting shear provides effective compression while maintaining greater comfort for the patient.The high stretch outer line layer provides 20% of the compression and holds the inner layer in a scaffold relationship that keeps it in place, reducing the tendency to slide down. This stability and the relationship between inner and outer stretch layers allow it to respond to limb volume reduction without the tendency to bunch up or move. These two layers, applied together, one cushioning and compressing on the inside and the other compressing and stabilizing on the outside, further reduce the effect of the ridges created by each layer interacting with the skin. This reduces the wrap edge pressure effect responsible for redness, skin irritation, and pain.

The overlap between the two layers creates a structural binding that strengthens the scaffold effect holding the K2 in place, allowing for four-layer type performance with a two-layer compression wrap.

Looking at the theoretical pressures that compression wraps apply, using Laplace’s law to convert tensile stretch into compression pressure, it becomes evident that at the ranges of therapeutic compression, the amount of energy or work that can be applied to the edematous tissue is much greater when both layers provide compressive energy. Notice that in the total load of the K2 in Newtons of the KTech outer layer and the KPress inner layer, there is a significant difference in total compressive work. When comparing the inner wrap of K2 and the traditional two-layer wrap, in the first layer, there is an 11 to 0 compression difference for the K2, when looking at the Newtons at the stretch recommended by the manufacturers. Applied by the second layer, there is a 2.5 to 10 compression ratio favoring the traditional 2-layer wrap. Most importantly, if we consider the sum of the inner and outer for the K2 vs the sum of the inner and outer for the traditional 2-layer wrap, the K2 is providing 13.5 Newtons of compression while the traditional two-layer wrap is only applying 10 Newtons.

This amounts to 35% more work being applied to the tissue by the K2 over the traditional two-layer wrap. This construction allows higher-energy to be applied to the tissue all while maintaining a lower pain level, fewer high-pressure points, and more comfortable compression.

Human Subject Study

The understanding that comes from the bench study of the total energy applied to the tissue by the K2 raises the question,“How do we then apply this product consistently to gain the best possible compression for the patient?” We conducted a human subject study where three nurses were trained to apply the K2 and the traditional two-layer wrap. Each nurse wrapped six people, five times with both of the two compression wraps, K2 and the traditional twolayer system.

“This construction allows higher-energy to be applied to the tissue all while maintaining a lower pain level, fewer high-pressure points, and more comfortable compression.”

The target compression was 40 millimeters of mercury. We measured the sub-bandage pressure achieved with each system using a PicoPress pressure measurement device. Pressures were measured with the volunteer in the supine (sitting with legs extended), and standing positions. The pressures were used to measure consistency and proximity to the target pressure. The difference between the nurse’s performance in reaching that target pressure with the K2 and the traditional twolayer compression wraps was reported.

In Figure 2, you see that when we plot the pressures achieved by each of the nurses with each device in the resting (supine) position, compression for both wraps is centered around 40 millimeters of mercury, with two very interesting observations; Nurses B and C both achieved an average pressure closer to the target pressure using the K2 over the traditional two-layer wrap; second, despite the fact that Nurse A was further away from the target with K2 than the traditional 2-layer wrap, the pressures observed were high. The observed pressure in Nurse A’s wraps was dramatically different, and in some cases

approached the risk of tissue injury; because of this videos and photographs of the process were reviewed.

These reviewed observations showed that Nurse A applied the wrap overlapping more than was required when using the K2; because the wrap application technique is essential to achieving therapeutic compression, training was repeated, and Nurse A repeated the wrapping process. It should be noted that Nurse A is a highly skilled nurse who applies 15 - 20 wraps per day and is very experienced in using the traditional two-layer compression system without a pressure guide.

Now looking at the data (Figure 3) following the second training, the graphs on the left (Nurse B and Nurse C) are the same as the data from the previous trial. The graph on the right demonstrates that when Nurse A properly applied the pressure guide, the average pressure was almost perfectly centered on the target pressure of 40 millimeters of mercury. Again, Nurse B and Nurse C moved towards the target pressure by using the K2 versus the traditional two-layer compression system.

Mastering the Art of Compression in Healing Venous

This application study using nurses and human volunteers shows that the training was most critical for the nurse that was skilled with the use of the traditional two-layer system. This difference is likely because of the difference in dynamic compression created by the K2, where both layers provide compression. With this training and using the Pressure Guide in compliance with the instructions, the K2 provides excellent consistency in reaching the target pressure. Overall, the K2 pressure guide allowed the nurses to obtain the target pressure consistently.

What does this mean for your patients? The K2 provides continuous therapeutic compression throughout the day or night, supine, ambulating, or sitting. The higher level of energy delivered by K2 and the scaffolding effect, allow it to continuously apply the target compression over a greater range of limb circumference and volume, and it is able to respond to the volume changes more effectively. This provides for an accurate and consistent therapeutic compression through the course of the use of the wrap for up to 7 days by the patient.

Translation of Data Into Practice

From a clinical perspective it is extremely important to have a treatment method that is continuous and effective. Continuous therapeutic compression means that the patient

will receive treatment day and night, regardless of ambulation status or limb size, and will move towards positive goals and especially the desired wound healing outcome.

The engineering of DCS padded short stretch layer with the overlying long stretch outer layer creates a mechanical averaging that reduces peak pressures and sheer forces at the edge of each layer, thus improving patient comfort.

Besides continuity and comfort, the consistency of therapeutic applications on every patient, regardless of limb circumference, has a synergistic affect towards positive outcomes. The visual aid printed on the wrap has a major contribution to the consistency of the application and allows verification of the correct application in the desired therapeutic range. A study conducted by Hanna shows 85% of nurses were able to apply a DCS wrap correctly on the first application.8 By comparison, the same target therapeutic range was achieved to 69%, using a standard of care four layer wrap, and to only 25% using a classic standard of care short stretch wrap. In a similar study Pilati reports that 87% of nurses hit the therapeutic range in the first application.9 DCS was far superior and easier to apply and was more comfortable compared to standard of care. To summarize, from a clinical practice perspective, this treatment approach removes the guesswork in applying accurate, therapeutic and consistent compression by

Mastering the Art of Compression in Healing Venous Wounds

reducing the risk for undercompression, which can prolong healing time, and overcompression, which can cause harm.

Dr Hugo Partsch is one of the world’s best known experts in compression therapy. Dr Partsch recognized that compression therapy is under used, and realized provider education can and should be improved. Writing in an editorial a few years ago, he explains; “The main problem concerning compression therapy is the lack of adequately trained staff. Some new compression devices which do not require special bandaging skills may replace conventional compression materials in the future.“ Indeed, it seems we may have arrived at that future, as the technology of this treatment achieves these desired goals.

In my practice, one of the issues I encountered a few years ago when using different compression wraps and short stretch wraps, was patients requesting specific staff members to apply their compression wrap because of the inter-staff variability. These requests posed difficulty to clinical flow and created hard feelings. However, since the adoption of DCS in our clinic this problem has been eliminated, attesting to the consistency it brought.

Of recent increased clinical interest has been the application of compression wraps as an additional treatment for diabetic lower extremity chronic wounds. Diabetes continues to show an increasing trend along with obesity.1

It has been estimated that approximately 1/4 of patients with venous leg also have diabetes as a comorbidity, and almost 50% of diabetic foot ulcers have lymphedema diagnosed as a complication.2,3

There is an increasing awareness that all

diabetic wounds on lower extremities, including feet, include an element of lymphedema. Hypoglycemia leads to micro-angiopathy, which in turn leads to degradation of the glycocalyx vascular barrier, increasing capillary filtration and distance to fluid buildup in the intracellular tissues, thus impairing the lymphatic pumps and allowing fluid buildup in the intracellular space, which compromises cellular function and delays healing of chronic wounds.4

A concern regarding application of compression on lower extremity for patients with diabetes is arterial impairment and compromised perfusion. Autonomic neuropathy creates microcircuitry changes of the skin including itching, venous prominence, callus formation, loss of nails and sweating anomalies, and can make it difficult to recognize skin perfusion changes due to arterial disease. Furthermore, sensory neuropathy could contribute to under reporting of pain or other ischemic symptoms.5

However, this concern can be addressed with a thorough arterial perfusion assessment. Arterial brachial index is an initial screening tool for arterial perfusion. This test involves having the patient lie flat for about 10 minutes so that their ankle is at the same height with the arm, to eliminate hydrostatic pressure differences. Subsequently, we obtain brachial pressure and ankle pressure and, for a normal patient, that should be an arterial breaker index ABI equal to 1.

A great number of guidelines have been published for interpretation of ABI and recommendations for compression application. A summary of these guidelines from many countries has been published by the European Wound Management Association in 2017.7 See Table 1.

Mastering the Art of Compression in

Arterial calcifications can cause limitations for obtaining adequate ABI’s calcified arteries. Higher pressure readings can allow overestimation of perfusion, or can even show normal perfusion, and patients that have significant arterial disease.

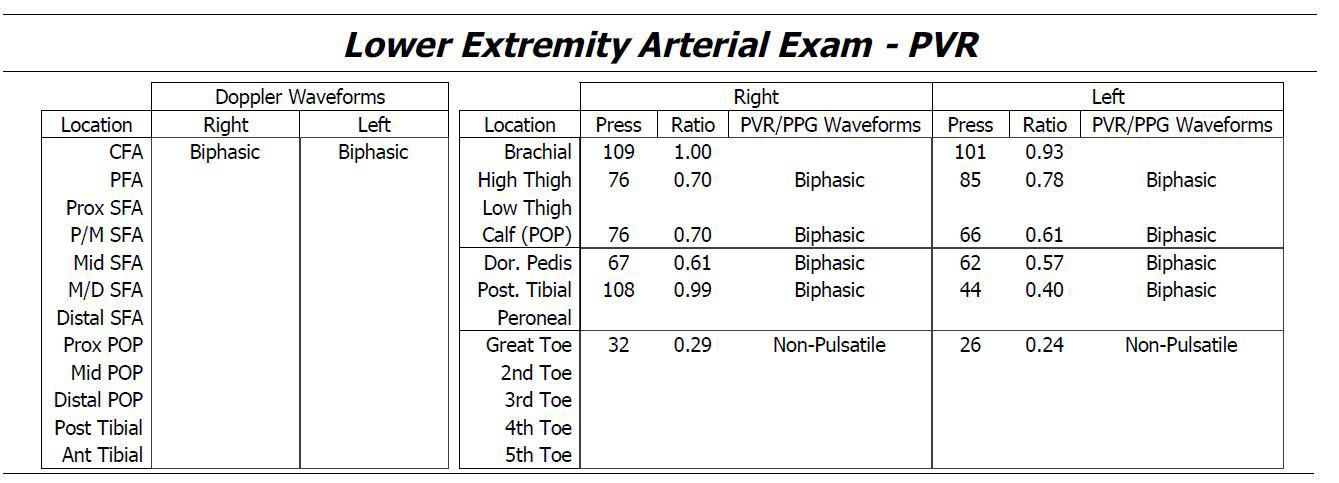

Diabetic patients are much more likely to have arterial classifications. In order to overcome this concern, additional arterial assessments such as obtaining segmental pressures, pulse volume recordings, and digital pressures can be extremely useful. These types of assessments are becoming standard of care in vascular labs equipped with better and more specialized equipment. However, with adequate training this assessment can be obtained using simple blood pressure cuff and handheld Doppler.

See Table 2. In this example, the patient presented with a diabetic toe ulcer and his ABI was 0.99, essentially normal. However, he failed to progress in spite of adequate treatment. Subsequent additional arterial evaluation showed low segmental pressures in his thigh, with biphasic waveforms and toe level pressures compromised and non-pulsatile. This prompted Vascular Surgery consultation and a revasculation procedure and limb salvage.

A large prospective study was published in May 2021 of 702 VLU patients using DCS and looking at wound healing rate, wound healing progression, assessment of edema and ankle mobility and local tolerability and acceptance.6 A post-publication analysis

of this study compared efficacy and safety of DCS, specifically non diabetic (n=492) versus diabetic (n=185) patients. Overall demographics were comparable between the two groups except for significantly higher percentage of comorbidities including hypertension, heart disease and diagnosed peripheral arterial disease. However no significant difference was seen in outcomes including one healing and edema reduction between the two groups. Local tolerance and acceptability were not significantly different.

We can conclude that compression is safe to use for patients with diabetic lower extremity alterations when they present with edema, venous stasis and lymphedema as comorbidities.

References

4. Kanapathy M, Portou M, Tsui J, Richards T. Diabetic foot ulcers in conjunction with lower limb lymphedema: pathophysiology and treatment procedures. Chronic Wound Care Management and Research. 2015;2:129-136

5. Tesfaye S, Boulton AJ, Dyck PJ, Freeman R, Horowitz M, Kempler P, Lauria G, Malik RA, Spallone V, Vinik A, Bernardi L, Valensi P; Toronto Diabetic Neuropathy Expert Group. Diabetic neuropathies: update on definitions, diagnostic criteria, estimation of severity, and treatments. Diabetes Care. 2010 Oct;33(10):2285-93. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1303. Erratum in: Diabetes Care. 2010 Dec;33(12):2725. PMID: 20876709; PMCID: PMC2945176.

6. Stücker M, Münter KC, Erfurt-Berge C, Lützkendorf S, Eder S, Möller U, Dissemond J. Multicomponent compression system use in patients with chronic venous insufficiency: a real-life prospective study. J Wound Care. 2021 May 2;30(5):400-412. doi: 10.12968/ jowc.2021.30.5.400. https:// pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33979221/

7. Andriessen A, Apelqvist J, Mosti G, Partsch H, Gonska C, Abel M. Compression therapy for venous leg ulcers: risk factors for adverse events and complications, contraindications - a review of present guidelines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017 Sep;31(9):1562-1568. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14390. Epub 2017 Jul 31. PMID: 28602045.

8. Hanna R, Bohbot S, Connolly N. A comparison of interface pressures of three compression bandage systems. Br J Nurs. 2008;17(20):S16-24.

9. Pilati, L. Do the findings in winter of a dual compression system compression bandage’s wear compliance with patients replicate if the study is repeated in the summer months?. SAWC Fall 2021.