SUSTAINABLE MANGROVEFRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT - MYANMAR ‘MYANMAR SUMFAD’ SEPTEMBER 2022

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The report ‘Sustainable Mangrove-Friendly Aquaculture Development’ was prepared under the oversight of Mr. Charles Selestine, Sustainable Finance Programme Manager of WWF-Myanmar, and Dr. Pyi Soe Aung, Conservation Director of WWF-Myanmar.

Lead Authors

Forest Ecology and Community Development Researcher (UQ)

Dr. Sang Phan

Juan Jose Robalino

Officer (GGGI)

Expert Reviewers

Catherine Lovelock

Aaron Russell (GGGI)

Natural

Gustavo Nicolas Paez (WWF-Myanmar)

WWF-Myanmar,

&

and GGGI express

for the

deepest

provided by

Cuong Chu, Dr. Ha Tran, Mr. Myo Myint, UQ’s local team in Myanmar, Ms. Nera Mariz Puyo (GGGI), Ms. Thinn Thinn Khaing (GGGI), and Mr. Jack Bathe (GGGI).

Supported

based

a decision of

This study received

and

Disclaimer

WWF-Myanmar does not make any warranty, either express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or any third party’s use or the results of such use of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed of the information contained herein or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR 3

–

Mr.

–

Capital

Value Chains

Dr.

(UQ) Dr.

Dr.

UQ,

its

appreciation

valuable contributions

Dr.

by:

on

the German Bundestag

principal funding from the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation

Nuclear Safety.

WWF.

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR 5 CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 2. INTRODUCTION 12 2.1 Policy Rational and Contributions to Myanmar’s NDC 12 2.2 Project Background and Objectives 13 3. METHODOLOGY 14 3.1 Valuation and Investment Analysis 14 3.2 Nature-based Solutions 15 4. EXTENSIVE AQUACULTURE - AYEYARWADY REGION 16 4.1. Geographic Distribution 16 4.2. Value Chian Analysis 18 4.3. Current Production under Extensive Aquaculture Systems 22 4.4. Cost-Benefit Analysis of Extensive Aquaculture Systems 26 4.4.1. Cost-benefit analysis for ponds without mangrove 26 4.4.2. Cost-benefit analysis for ponds with mangrove (mangrove-friendly aquaculture 26 5. MANGROVE FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE PRODUCTION 27 5.1 Site Suitability Identification 27 5.2 Investment Requirements for Mangrove Friendly Aquaculture Practices 29 5.3 Landscape Impact – Business as Usual vs. Mangrove Friendly Aquaculture 29 5.3.1. Baseline 30 5.3.2. Scenarios 30 5.3.3. Return on Investment Analysis 30 5.3.4. Sensitivity Analysis 33 5.4. Mangrove-friendly Aquaculture and NbS 34 6. SUSTAINABLE INPUT SOURCING – CRAB HATCHERIES 36 6.1. Current Situation of Crab Hatcheries in the Region 36 6.2. Site Suitability Identification 37 7. PRIVATE SECTOR ENGAGEMENT MODEL 38 8. RISKS 39 8.1. Fair Business Practices 39 8.2. Human Rights & Ethics 39 8.3. Labor Rights 40 8.4. Environment 41 9. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 42 9.1. Conclusions 42 9.2. Recommendations 43 10. REFERENCES 45 11. ANNEX 1 - Considerations and Assumptions 46 LIST OF TABLES TABLE 1. Criterion 1 - key societal challenges addressed by implementing mangrove-friendly aquaculture. 11 TABLE 2. NbS Global Standard criteria. 15 TABLE 3. Aquaculture pond area and distribution in mangrove land in the Ayeyarwady Delta. 16 TABLE 4. Types of aquaculture ponds in mangrove land in the Ayeyarwady Delta. 17 TABLE 5. Land use status on mangrove land areas in the Ayeyarwady Region. 17 TABLE 6. List of importing markets for live crabs exported by Myanmar (in USD value). 20 TABLE 7. List of importing markets for processed crabs (e.g., soft-shell) exported by Myanmar (in USD value).21 TABLE 8. Key ecosystem actors in the value chain. 22 TABLE 9. Cost-benefit analysis for extensive aquaculture ponds without mangrove. 26 TABLE 10. Cost-benefit analysis for polyculture aquaculture in ponds with mangroves. 26 TABLE 11. Cost-benefit analysis for crab aquaculture in ponds with mangroves. 26 TABLE 12. Suitable areas for mangrove-friendly aquaculture in different townships in the Ayeyarwady Delta.29 TABLE 13. Baseline valuation of pond areas on mangrove land for implementing mangrove-friendly aquaculture (2022).30 TABLE 14. Return on investment analysis 2022-2042 (million USD). 31 TABLE 15. Sensitivity analysis for the NPV for the 3 scenarios. 34 TABLE 16. Criterion 1: Key societal challenges relevant to aquaculture. 34 TABLE 17. Key considerations and assumptions for modelling the three scenarios. 46 LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 1. Net Present Value (NPV) for three scenarios and for multiple periods of time. 10 FIGURE 2. 3Returns Framework Stages. 14 FIGURE 3. Aquaculture products value chain. 18 FIGURE 4. Mangrove aquaculture pond with mangroves. 23 FIGURE 5. Brackish water pond without mangroves. 23 FIGURE 6. Concrete gate of brackish aquaculture pond. 24 FIGURE 7. Pond timber/wood gate, which is common in Myanmar. 24 FIGURE 8. Catching natural juvenile crabs for mangrove aquaculture pondsrove aquaculture ponds. 25 FIGURE 9. Catching natural shrimp fingerlings for mangrove aquaculture ponds. 25 FIGURE 10. Map of potentially suitable areas for mangrove-friendly aquaculture in the Ayeyarwady Delta. 28 FIGURE 11. Net Present Value (NPV) for the 3 scenarios and for multiple periods of time. 32 FIGURE 12. Return on Investment (ROI) for the 3 scenarios and for multiple periods of time. 33 FIGURE 13. Recommended private sector engagement model. 38

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) started its programme in Myanmar in 2014, with the strong belief in the need to collectively protect Myanmar’s forests and rivers, ensuring a future for Myanmar’s precious wildlife. WWF-Myanmar is keen to explore avenues to conserve mangroves whilst providing sustainable livelihoods. Further, WWF-Myanmar sees the need to catalyze nature positive responsible investments from the private sector, to ensure the long-term viability of any initiatives.

WWF-Myanmar is developing the Ayeyarwady River Landscape as a priority area. The need to counter the rapid deforestation of mangroves in Myanmar led the Project to explore suitable initiatives related to mangrove conservation and restoration in the Ayeyarwady Delta. In December 2020, WWF-Myanmar, together with other partners, carried out the “Scoping study on mangrove restoration and increasing resilience in the Ayeyarwady Delta”. In July 2022, a study on Community-Based Sustainable Management of Mangroves was conducted with a local NGO partner.

The main goal of this study is to support mangrove restoration and rehabilitation and to increase resilience in the Ayeyarwady Delta by providing evidence of the ecosystem services provided through the implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture, as well as to support reaching sustainability in the value chain of key aquaculture products in the region.

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR 7

METHODOLOGY

The analyses conducted in this report follows the goals of GGKP’s ‘3Returns Framework: A method for decision making towards sustainable landscapes’ and the IUCN’s report Aquaculture and Nature-based Solutions’. These guiding sources aim to promote sustainable development by mainstreaming natural capital in development planning while presenting the synergies between aquaculture and marine conservation through the emerging concept of Nature-based Solutions (NbS).

The valuation and investment analysis at the production level (i.e., mangrove-friendly aquaculture) in this report follows the 3Returns Framework. The analysis followed this Framework to facilitate decision-making, support the assessment of environmental and social impacts, identify the efficient allocation of resources, support the identification of best practices for sustainable landscape interventions, and establish clear foundations for bankability to drive project implementation.

In order to identify the synergies between aquaculture and NbS, this report has used the IUCN NbS Global Standard framework and criteria in order to assess the implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices in the Ayeyarwady Delta. The criteria has been taken into consideration during the valuation and investment analysis for mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices to frame it as a naturebased solution.

ANALYSIS & RECOMMENDATIONS

A cost-benefit analysis for extensive aquaculture without mangroves and with mangroves within the ponds provided evidence of higher monetary benefits (from USD 65 to 250 per hectare per year) from aquaculture practices with mangroves within the ponds. Furthermore, results from an investment analysis from a landscape perspective found that the greater benefits from potentially implementing mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices in mangrove land outside nationally protected areas are not only attractive in monetary terms, but also significant in terms of non-monetary benefits (i.e., carbon sequestration, green jobs, and species diversity). Implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices in suitable ponds in mangrove land will improve the status of natural capital in the Ayeyarwady Region, as well as the number of people provided with capacity development for conducting sustainable economic activities directly linked with an increase in their adaptive capacity. The analysis did not consider strategies to increase the area of conservation land, although this could also be considered as a part of the strategies to conserve mangrove cover.

Among mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices suitable for mangrove areas in the Ayeyarwady Region, including crab-culture and polyculture (shrimp and crab), crab-culture is the most ‘mangrove-friendly’ practice due to the smaller

area needed for ponds and the necessary depth of ponds. In addition, mangroves in good condition within ponds have a direct benefit on crab health and productivity overall, while for polyculture, higher ratios of closed mangrove canopy cover can lower shrimp productivity due to lower temperatures of the water under tree shade.

For analyzing the potential impact of implementing mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices in suitable ponds in mangrove areas, three scenarios were defined and modelled for the period 2022-2042. The first scenario, a Business as Usual (BAU) scenario, reflects what would happen if no mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices are implemented and mangrove areas continue to be used as in the current situation. The two Green Growth Scenarios consider the potential implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices for polyculture and crabculture in suitable ‘pond areas on mangrove land’ – 38,269 ha identified. However, Green Growth Scenario 2 also considers the potential monetary impact of prioritizing crab culture due to its more ‘mangrove-friendly’ characteristic and from monetizing carbon sequestration through carbon credits.

From a landscape perspective, the investment needed to implement mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices in suitable ponds in

mangrove land in the Delta (38,269 ha) has been estimated at USD 50.83 million to USD 61.92 million, considering a period of 20 years (2022 – 2042) and depending on the relative emphasis on carbon sequestration potential and crab culture vs. polyculture. It is estimated that around 50% of the total investment needed for mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices needs to be allocated for planting and rehabilitating mangroves within aquaculture ponds.

An analysis of the Net Present Value and the Return on Investment during multiple periods of time for current practices versus the implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices showcases the profitability of current and mangrove-friendly practices from 2027 to 2042. Under mangrovefriendly aquaculture practices profitability is higher than current practices but at the same time, the investment needed is significantly higher. The slow and minimum adoption and implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices despite their greater benefits can be explained by the socioeconomic conditions of the Region and the lack of resources for investment. The shift from economic activities dependent on extractive actions to sustainable production models that require significant investment for their implementation is constrained by the high opportunity cost in the short-term.

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR 9

The results provide evidence that any efforts for monetizing ecosystem services, for instance carbon sequestration through the sale of carbon credits, can increase the returns from implementing mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices, thereby decreasing the opportunity cost of moving

from current practices to improved production practices. In addition, following the IUCN NbS Global Standard framework, key positive impacts on societal challenges have been estimated as presented in the following page.

Societal Challenges Mangrove land areas suitable for shrimp and polyculture (ha)

Climate change mitigation and adaptation

Disaster risk reduction

Economic and social development

Mitigation: total carbon sequestration 2022-2042: 3,340,416 MtCO2e Adaptation: number of people supported to cope with the effects of climate change : 8,265

Increase in value of coastal protection: USD 177.54 million

Net Present Value (2022-2042, disc. Rate – 7%): USD 552.98 million

Return on Investment: 14.49 (ratio) Benefit-Cost ratio: 3.16 (ratio)

Green Jobs: 2,667 (FTE green jobs created and maintained)

Human healthAnticipated health benefits from improved nutrition (protein consumption)

Food securityIncrease in aquaculture production (value in PV – 2022-2042): USD 75.51 million

Water security No impacts in water quality if following Good Aquaculture Practices (GAqP)

Ecosystem degradation and biodiversity loss Improvement in biodiversity (Shannon index): 0.25

An assessment of the production inputs needed to support a sustainable aquaculture industry highlighted that there are currently no operational hatcheries in the Ayeyarwady Region that can sustainably supply the stocks needed for a responsible production system, even after implementing mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices. Challenges to sustainable supply include the low availability of natural stocks and multiple barriers to establishing a hatchery. For the latter, two of the most challenging obstacles to ensuring a successful implementation and operation of hatcheries in the Ayeyarwady Region are access to adequate saline water and access to electricity. Considering these challenges, the study suggests two solutions for establishing a hatchery for crab production in the Ayeyarwady Delta in Myanmar:

1. Build a crab hatchery in Chaung Thar town area, in the west of the Ayeyarwady Region, far from the mouth of the Ayeyarwady River and its freshwater influence. This will facilitate access to water with salinity > 20 ppt year round. This town has access to the national electricity grid, which makes it convenient for operating a crab hatchery. In addition, Pathein University has a fishery and mangrove experimental station near the town of Chaung Thar, which is a suitable place to set up a medium to large-scale crab hatchery. The disadvantage of this location is that it is far from the crab farming area on mangrove land in the townships of Pyapon, Bogale and Labutta, so transportation costs are high. The survival rate of the crabs may be jeopardized as they are easily shocked by the sudden change in the environment when moving from the hatchery to ponds.

2. The second option proposed is to build crab hatcheries in the following locations: Labutta town, Labutta township, and in Myogon village, Pyapon township. These two locations have access to an electricity grid and are easily accessible by road and by river streams. Based on the results of the survey conducted these two locations are close to salt fields from which farmers can buy and transport water with high salinity. High salinity brine can be mixed with low salinity river water to achieve the required salinity for hatchery production. In addition, these two locations are close to the main mangrove aquaculture areas in the Ayeyarwady Delta, making it possible to transport crab larvae to the ponds quickly and conveniently.

To conclude, and considering the potential institutional, social, and environmental risks that the implementation of hatcheries and mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices could face in the Ayeyarwady Region, it is strongly emphasized that local communities and private companies should be involved in the transformation of degraded mangrove land toward more productive and sustainable uses. In terms of leveraging financial resources, access to loans with low interest rates and grace periods could be components of mechanisms to mobilize the resources needed for moving toward mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices in the region. Incentives or accessible resources could be provided by international development assistance that could support the transformation of degraded mangroves into more productive systems with sustainable practices in the Ayeyarwady Delta. Yet, increasing and promoting investment in aquaculture should be done in a way that protects and expands mangroves for the provision of ecosystem services.

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR 11

Figure 1. Net Present Value (NPV) for three scenarios and for multiple periods of time.

Table 1. Criterion 1 - key societal challenges addressed by implementing mangrove-friendly aquaculture.

INTRODUCTION

The mangrove forests of the Ayeyarwady Delta have sustained one of the highest deforestation rates in Myanmar and among mangroves globally. This loss has been primarily anthropogenic in nature, including the expansion of agriculture and aquaculture land uses, and the harvesting of wood for fuel and construction purposes. Mangrove deforestation has negatively affected the stock of natural resources (particularly forests and fisheries) in the Delta, which represent the main income source for a significant proportion of the population. Deforestation and mangrove degradation has also reduced the capacity of coastal mangrove forests to act as a barrier against waves and storm surges contributing to the loss of 135,000 lives during Cyclone Nargis (2008) (WB, 2020).

Mangrove conservation efforts in Myanmar face significant barriers such as weak governance, lack of technical capacity, and lack of financial resources or incentives for their maintenance (GGKP, 2020). An analysis of satellite data conducted by GGGI and UQ, funded by the World Bank (WB) estimated that a total of 178,961 ha of degraded mangroves remain in the Ayeyarwady Region, of which roughly 88,902 ha are managed directly by private sector landowners (WB, 2020). This study and the analysis of individual value chains highlighted the potential for private sector aquaculture pond owners (WAVES, 2020a) and other agroforestry system stakeholders (WAVES, 2020b) to reverse some of the key drivers of mangrove degradation, while enhancing economic and livelihood returns.

2.1. Policy Rational and Contributions to Myanmar’s NDC

Myanmar has been engaged in designing and implementing the required policies, governance, and programming instruments to address socio-economic development and play its part in mitigating global climate change as well as adapting to it. Myanmar’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) shows the nation’s commitment to climate change mitigation and adaptation by pursuing a balance between socioeconomic development and environmental sustainability.

In Myanmar’s 2021 (Updated Submission) NDC to the UNFCCC , the Forestry Department has set a conditional GHG emission reduction of 256.5 million tCO2e by 2030, by committing to implement, among other projects, the Myanmar Reforestation and Forest Rehabilitation Programme (MRRP) to its full extent. The MRRP (until 2026) aims to restore around 1 million ha of degraded and deforested land through a combination of plantation establishment (including mangrove forest) on both state-owned and private land, Community Forestry (CF), agroforestry, natural forest regeneration, and enrichment planting. Additionally, the projects prioritizing the conservation of important forest areas such as intact forests, mangroves, and unique habitats, are recognized as forestry projects that would contribute to the fulfillment of the NDC.

These national commitments are implemented through several key sectoral policy actors, in particular by the Environmental Conservation Department (ECD) and Forestry Department (FD), both of which are housed within the Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Natural Resources (MONREC), and by the Department of Agriculture (DoA) and Department of Fisheries (DoF), which are housed within the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MOALI).

The ECD is the national focal agency for developing and mainstreaming the implementation of Myanmar’s Climate Change Master Plan (2018–2030) across other sectors. The Master Plan recognizes that climate-smart agriculture technologies and practices in aquaculture (i.e., mangrovefriendly aquaculture) play a critical role in supporting the long-term goal of achieving climate-resilience and pursuing a low-carbon pathway for inclusive and sustainable development.

The DoF is the primary agency mandated to enable aquaculture practices in Myanmar2. The DoF launched the “National Aquaculture Development Plan” (NADP) in early 2020, which has targeted the following by 2022:

• Developing and promoting 6,000 ha of mangrove-friendly farming systems. (Baseline 2018 – 4,000 ha of mangrove friendly farming systems)

• Access to adequate finance is improved, allowing 100 farmers and enterprises to have access to adequate financing options. (Baseline 2018 – None)

According to Myanmar’s 2021 NDC, international assistance will be required to meet several aspects of the target, including but not limited to the development and implementation of sectoral and national plans that support mainstreaming activities within existing programs, including the Good Aquaculture Practices (GAqP). The GAqP is a key component of the NADP, which also recommends mangrove-friendly aquaculture and highlights the importance of taking measures to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

2.2. Project Background and Objectives

WWF started its programme in Myanmar in 2014 with a strong belief in the need to collectively protect Myanmar’s forests and rivers, ensuring a future for Myanmar’s precious wildlife. Currently, and within the context of its Sustainable Finance Programme, WWF Myanmar manages a project titled “Taking Deforestation out of Banks Portfolios in Emerging Markets”. The Project is funded through the International Climate Initiative (IKI) by the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU), Germany.

Under this Project, WWF Myanmar is developing the Ayeyarwady River Landscape as a priority area. The need to counter the rapid deforestation of mangroves in Myanmar led the Project to explore suitable initiatives related to mangroves in the Ayeyarwady Delta. In December 2020, WWF Myanmar, together with other partners, carried out the “Scoping study on mangrove restoration and increasing resilience in the Ayeyarwady Delta”. In July 2022, a study on Community-Based Sustainable Management of Mangroves was conducted with a local NGO partner.

Based on this proposal and WWF’s New Deal for Nature, which seeks to protect and restore nature for the benefits of the people and the planet, WWF-Myanmar is keen to explore avenues to conserve mangroves whilst providing sustainable livelihoods. Further, WWF-Myanmar sees the need to catalyze nature positive responsible investments from the private sector, to ensure the long-term viability of any initiatives.

In response to this, the University of Queensland (UQ) and the Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI) have prepared the following study presenting a detailed assessment of the ecosystem services enabled through the implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture with a scope in the production and input stages in the value chain.

The main goal of this study is to support mangrove restoration and increasing resilience in the Ayeyarwady Delta by providing evidence of the ecosystem services provided through implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture, as well as to support reaching sustainability in the value chain of key aquaculture products in the region. Under this overall goal, the specific objectives are:

• Objective 1: Identifying suitable sites for implementing mangrovefriendly aquaculture practices in the Ayeyarwady Delta;

• Objective 2: Comparing the impacts of BAU aquaculture pond management with mangrove-friendly pond management through a valuation and impact investment analysis that recognizes ecosystem service returns for coastal protection, carbon sequestration, and biodiversity improvement; and

• Objective 3: Identifying suitable sites for implementing crab hatcheries that can support a sustainable aquaculture production system in the Delta.

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR 13 2.

2 The primary legislation regulating aquaculture in Myanmar is the Law relating to Aquaculture 24/1989 (Aquaculture Law revised in 2019). It requires that any individual wishing to engage in aquaculture has to obtain a license from the DoF, except where the pond covers a surface area of less than 25’ x 50’ and is operated by a family for its personal consumption (DoF, 2020). 1 https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/NDCStaging/Pages/All.aspx.

3. METHODOLOGY

The analyses conducted in this report follows the goals of the ‘3Returns Framework: A method for decision making towards sustainable landscapes’ and the report Aquaculture and Naturebased Solutions’. These guiding sources aim to promote sustainable development by mainstreaming natural capital in development planning while presenting the synergies between aquaculture and marine conservation through the emerging concept of NbS.

3.1. Valuation and Investment Analysis

The valuation and investment analysis at the production level (i.e., mangrovefriendly aquaculture) in this report follows the 3Returns Framework3. The analysis followed this Framework to facilitate decision-making, support the assessment of environmental and social impacts, identify the efficient allocation of resources, support the identification of best practices for sustainable landscape interventions, and establish clear foundations for bankability to drive project implementation.

The assessment of mangrove-friendly aquaculture implementation followed the 3Returns Framework considering ‘green’ interventions in a landscape as:

• Investments in Natural Capital: resources allocated to increase the stocks of natural assets;

• Investments in Social & Human Capital: resources allocated to increase cooperation within and among groups, individual and collective knowledge, skills, and competencies; while building/strengthening institutions for resource management, decision making, and social integration; and

• Investment in Financial Capital4: resources allocated to acquire or increase the assets needed in order to provide goods or services.

Figure

Framework Stages

The 3Returns Framework also contrasts a BAU scenario against green growth scenarios to understand changes in key capital indicators (natural, social & human, and financial capital) and the benefits derived from them. In this report, the development of a range of green growth scenarios was based on literature review, expert consultation, and a baseline survey in the study sites. The BAU scenario assumes continued mangrove degradation with limited mangrove restoration projects. The green growth scenarios are based on the implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices. One of the green growth scenarios also assesses the impact of monetizing carbon sequestration through the sale of carbon credits.

3.2. Nature-based Solutions

The report ‘Aquaculture and Nature-based Solutions – Identifying synergies between sustainable development of coastal communities, aquaculture, and marine and coastal conservation’5 examines the emerging concept of NbS and the IUCN Global Standard when applied to social-ecological systems that include aquaculture production.

According to IUCN, “Nature-based Solutions are actions to protect, sustainably manage and restore natural and modified ecosystems in ways that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, to provide both human well-being and biodiversity benefits” [(IUCN, 2020) cited in (Gouvello, Brugere, & Simard, 2022)].

To design, evaluate and monitor NbS in the near future, the IUCN NbS Global Standard provides a defined framework with eight criteria to be met:

Table

NbS Global Standard Criterion

Criteria

Criteria

Criteria

Criteria

Criteria

Criteria

Criteria

Criteria

Source:

Design

address

In this report, the eight criteria have been taken into consideration during the valuation and investment analysis for mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices to frame it as a NbS. This report begins by understanding ‘mangrove aquaculture’ as a possible intervention for coastal erosion regulation (NbS) as defined by European Commission (2015) example No. 99 ‘Encourage increased use of mangroves within and around existing extensive tropical aquaculture ponds’ (European Commission, 2015). More extensive mangroves provide greater level of coastal protection. The report presents enough evidence to consider mangrove-friendly aquaculture in the Ayeyarwady Delta as a NbS.

3 The 3Returns Framework methodological description is publicly available and can be found in the Green Growth Knowledge Platform under the Expert Group on Natural Capital featured resources - https://www. greengrowthknowledge.org/working-group/ natural-capital.

4 Financial capital, or produced capital, is part of economic capital.

5 The report is available online through IUCN library - https://portals.iucn.org/ library/efiles/documents/2022-005-En.pdf

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR 15

2.3 Returns

1 NbS effectively

societal challenges.

2

of NbS is informed by scale.

3 NbS result in a net gain to biodiversity and ecosystem integrity.

4 NbS are economically viable.

5 NbS are based on inclusive, transparent and empowering governance processes.

6 NbS equitably balance trade-offs between achievement of its primary goal(s) and the continued provision of multiple benefits.

7 NbS are managed adaptively, based on evidence.

8 NbS are sustainable and mainstreamed with an appropriate jurisdictional context.

[(IUCN, 2020) cited in (Gouvello, Brugere, & Simard, 2022)]

2. NbS Global Standard criteria.

4. EXTENSIVE AQUACULTUREAYEYARWADY REGION

4.1. Geographic Distribution

Following a semi-supervised satellite image (Planet Earth images) classification, validated with Google Earth and Spot 5 images, the World Bank (WB), GGGI, and UQ estimated that by 2019 (WB, 2020) the total area of aquaculture ponds on mangrove land in the Ayeyarwady Delta was 38,296 ha. From this total, it was estimated that 20,751 ha of aquaculture ponds were located on ‘private land’6 and 17,545 ha were located in areas under government management7 (See Table 3).

Table 3. Aquaculture pond area and distribution in mangrove land in the Ayeyarwady Delta

Type of Ponds

Ponds with degraded mangrove

Ponds with regrowth mangrove

Ponds without

Aquaculture Pond Area on Mangrove Land (ha) BogaleLabutta NgapudawPatheinPyapon

below.

use status of mangrove land in the Ayeyarwady Delta has

Table 5. Land use status on mangrove land areas in the Ayeyarwady Region.

Mangrove land status (outside National Parks*) Area (ha)Ratio to total mangrove land (%)

Mangrove land (excluding National Parks) 80,166 49.1%

Degraded mangroves 20,217 12.4%

Secondary & regenerating mangroves 48,906 29.9%

Aquaculture ponds46421,065 15295 16,521 38,296

Aquaculture ponds on ‘private land’ 20,751 Aquaculture ponds in areas under government control 17,545

Source (WB, 2020).

Aquaculture ponds in mangrove land in the Ayeyarwady Delta can be divided in three main types, aquaculture ponds with degraded mangrove, aquaculture ponds with regrowth mangrove, and aquaculture ponds without mangrove (WB, 2020). These three types of ponds have been built on mangrove land by digging ditches and creating earthen banks that limit water flows. Some of them include flood gates (i.e., wood-based and/or concrete) that support manipulating water level within the pond. The different types of aquaculture ponds on mangrove land are differentiated by the state of the mangroves in them. Most often mangroves are located in the central shallower parts of the pond. Aquaculture ponds can include degraded mangrove, which have been continuously logged (cut) for fuelwood and timber purposes and that may be stressed due to limited tidal flows. Aquaculture ponds can also include regrowth mangrove, which are characterized by multispecies mangrove plantations and natural regeneration of mangroves that have been protected. These mangrove areas have a standing wood volume of 50 to 200 m3/ha and are the highest quality mangrove areas in the region. Finally, there are aquaculture ponds in mangrove land with no mangroves within or surrounding the ponds (WB, 2020). Table 4 present the distribution of these type of ponds on mangrove land in the Ayeyarwady Delta in 2019.

Established plantations 5,072 3.1%

Unvegetated saline land 5,970 3.7%

Pond areas on mangrove land (outside National Parks) 38,269 23.4%

Pond with degraded mangroves 2,678 1.6%

Pond with secondary and regrowth mangroves 10,479 6.4%

Pond without mangroves 25,112 15.4%

Nipa palm 44,930 27.5%

Group by mangrove status

Degraded mangroves 22,894 14.0%

Secondary & regenerating mangroves 59,386 36.4%

Established plantations 5,072 3.1%

Unvegetated saline land 31,082 19.0%

Nipa palm mixed with other mangrove species 44,930 27.5%

Total mangrove land 163,364 100.0%

Total mangrove land area within Reserve Forests (RFs) 73,370

Total pond areas in mangrove land within RFs 17,545

6 The Myanmar state is the ultimate owner of all lands and resources in Myanmar. Land under Form 7 allows the farmer to have selling and inheritance rights of the land, as well as the rights over the land for a loan deposit.

7 Reserve Forests (RF) and National Parks (NP) are areas under direct government control. In RF areas, two type of community-based resource management are allowed: Community Forestry User Groups (CFUG) represent a group of community members that are allocated a certain amount of forest land (mangroves), which is collectively managed by the members; and Village Fuelwood Plantations (VFP), which are rehabilitated forest plantations (mangroves) established by the regional forestry department officials and of which all members of the village are granted with equal rights and responsibilities for its management.

Total mixed nipa palm areas within RFs 8,876

Nipa palm mixed with other mangrove species outside RFs36,054

Mixed nipa palm area suitable for shrimp 7,090

Mixed nipa palm area suitable for crab 19,282

*Note: National Parks in Myanmar are places that have been assigned to protect biodiversity and natural resources, as well as to protect historical and cultural values. The exploitation and use of resources in these areas is prohibited.

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR 17

Aquaculture Pond Area on Mangrove Land (ha) BogaleLabutta NgapudawPatheinPyapon Total

Total

353 19 2,323 2,695

1755,108 152 465,009 10,490

mangrove 289 15,604 30 9,189 25,112 Total 46421,0651529516,52138,297 Table 4. Types of aquaculture ponds in mangrove land in the Ayeyarwady Delta. Source (WB, 2020). For 2022, and following the same methodological approach, the land

been assessed and the results are displayed in the table

Value Chain Analysis

Aquaculture and capture fisheries are a key pillar of the Myanmar’s economy, contributing to around 2% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), 50% of animal protein consumption, and up to 56% of state/regional government revenue in 2019 (Fodor & Ling, 2019). While capture fisheries have dominated for decades, sustainability concerns related to the over exploitation of fish stocks have led to a shifting focus on the development of aquaculture production (USAID, 2021). Prior to 2021, the government emphasized the development of aquaculture as a driver of economic growth, job creation, and inclusive and sustainable development. This emphasis was expressed through the Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan (2018-2030), the Agricultural Development Strategy and Investment Plan (2018-2023), the National Aquaculture Development Plan (2020-2022) and the National Export Strategy (2020-2025).

According to the NADP, the land area utilized for aquaculture was estimated at 197,299 ha in 2018-2019. Approximately 94% of aquaculture ponds in Myanmar are located in Yangon, Bago, Rakhine, and Ayeyarwady Regions. The greatest concentration of ponds (72%) are located in the Ayeyarwady Region and Rakhine State (DoF, 2020).

Aquaculture products in the Ayeyarwady Region and in Myanmar are important for domestic food security as they are the lead providers of animal protein and micronutrients relevant for the development of children. Nationally, the amount spent on fish products (14%) is almost as much as

Figure3. Aquaculture products value chain.

the amount spent on rice (19%) (WAVES, 2020a). Despite the importance of aquaculture products, there are significant concerns regarding the unsustainable exploitation of natural aquatic resources and the destruction of their natural habit.

To this, the non-recognition of aquaculture as a form of agriculture by local institutions and the onerous process to conduct aquaculture practices negatively impacts the growth and sustainable development of the value chain (WAVES, 2020a).

The value chain of aquaculture products in the Ayeyarwady Region is complex and involves multiple stakeholders in the input supply, production, and processing and distribution stages, as well as in markets. Among the main actors in the value chain, most roles are male-dominated. The importance of encouraging the participation of women within the value chain as a direct method for improving household nutrition and decision making has been highlighted. Female involvement provides women with the ability to obtain greater financial independence which leads to greater female involvement in household decision-making (WAVES, 2020a).

According to Fitzsimmons & Romatzki (2019), within the value chain of aquaculture products in the Ayeyarwady Region and Yangon, crabs (soft-shell and hard-shell) and shrimp (freshwater prawns) were the most valuable products. Figure 3 presents the value chain for aquaculture products in the Ayeyarwady Region. A brief explanation of each stage, as well as the main challenges faced by the main actors in each stage, are presented below.

Inputs

The main input suppliers include feed suppliers and larvae stock suppliers. Fishers use locally designed and manufactured tools to collect and catch larval stock from mangrove creeks and channels. The naturally available harvest is either sold to village-level traders and collectors, or to aquaculture farmers (WAVES, 2020a). In Myanmar there are 70 hatcheries8 in total, of which 27 are state-owned and operated by the DoF (USAID, 2021). Of these 27 hatcheries, only five are located within the Ayeyarwady Region (WAVES, 2020a). Challenges faced by suppliers include low availability of natural stock (from fishers) and operational difficulties (for hatcheries) including insufficient and unstable electricity supply, poor quality feed, and high energy requirements that translate to high production costs (WAVES, 2020a).

There are 17 feed suppliers in Myanmar according to the Myanmar Aqua-Feed Association (USAID, 2021). Unfortunately, all the feed mills are in and around Yangon with limited distribution in rural areas which represents a challenge for producers in the Ayeyarwady Region. The lack of access to feed (i.e., cost and distance) leads producers to use natural fish stocks and trash fish to feed stock in aquaculture ponds (WAVES, 2020a).

Production

There are two main types of aquaculture production: intensive and extensive farm production. Extensive aquaculture, practiced mainly by small-scale farmers, depends mostly on natural seed and feed supply. Products managed by small-scale farmers include mud-crab (Scylla spp.), tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon), and sea bass (Lates sp.) (WAVES, 2020a). Intensive aquaculture has a specific focus, depending on the expertise of farmers (shrimp, crab, or fish). Regularly, intensive farms operate as enterprises and have integrated input supply operations, as well as post-harvest operations, depending on their target market (USAID, 2021).

After harvest, farmers that sell to domestic markets practice limited value-addition. Farmers targeting international markets, pre-process (clean, weigh, package) and send the products to cold storage facilities (USAID, 2021). Challenges faced by farmers at this stage depend on their production scale:

For small-scale farmers, the main challenges include (GGGI, 2019) (WAVES, 2020a) (USAID, 2021):

• Difficulty in obtaining land and necessary permits for operating their business;

• Limited access to formal finance;

• Financial constraints, meaning farmers are only able to pay hatcheries following the harvest which places financial strain on the hatcheries;

• Poor quality of products linked to poor access to supplies and equipment; and

• Prevalence of diseases due to a lack of effective pond and water management.

• For small and medium enterprises, the main challenges include (GGGI, 2019) (WAVES, 2020a) (USAID, 2021):

• Difficulty in obtaining land and necessary permits for operating their business;

• High operational costs decreasing their comparative advantage;

• Difficulty in finding available finance with banks as many banks do not accept land as security for loans; and

• Government hatchery programs being unable to meet demand.

Intermediary, Processing, and Markets

Village and township traders commercialize aquaculture products through local markets or through well-established wholesale markets located in Yangon and Labutta. Exporters, hotels, restaurants, and local retailers are the buyers at wholesale markets (WAVES, 2020a). Most of the time, aquaculture products arrive to wholesale markets packed only with ice, and are transported either using in-house trucks or by middlemen. Transportation from farms often takes place by multiple means, including by trailers, motorcycles, and boats. Cold chain logistic providers are limited in the region. Furthermore, to save fuel costs, no proper refrigeration is used, only ice layering (USAID, 2021) (WAVES, 2020a).

Processing in Myanmar includes basic processing within facilities that lack the technical and financial capacity to produce high-value processed items. Aquaculture products are exported in raw or semi-processed forms. Exporters take the products after they enter cold storage facilities and sell them directly to importers in end markets for further processing, distribution, and consumption (USAID, 2021

For traders, processors, and distributors, the main challenges include (USAID, 2021):

• Long term supply contracts and formal contracting are not common in Myanmar, jeopardizing the regular supply of raw materials;

• Inability to provide consistent quality in supplied products with a negative impact on their relationships with customers;

• Inadequate supply of potable fresh water at landing sites and ice production facilities which leads to contamination and the inability to meet international market requirements.

• Lack of reliable electricity supply making it difficult to ensure quality consistency along the supply chain; and

• Limited access to finance which constraints further investment to improve the supply chain.

8

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR 19 4.2.

Hatcheries focus on breeding, hatching, and rearing through the early stages of fish and crustaceans (USAID, 2021).

In terms of end markets, according to USAID (2021), 50-60% of total fresh and 80% of total processed fishery products are sold in domestic markets. As identified above, wholesalers represent the most important sales channel for aquaculture products in the country. At wholesale markets, there is no price standardization, as well as no diligent application of food safety protocols9. Overall, statistics on domestic demand and the volume of sales of fish products at wholesale markets are unavailable. In addition, the lack of market information makes it difficult for producers to study and understand demand and price trends; the availability of which could lead them to make informed decisions in terms of production planning, harvest scheduling, and logistics planning, and which could ensure that production and operation activities are aligned with market demand (USAID, 2021).

In terms of international markets, Myanmar’s exports are dominated by selected species that have traditionally been produced, including mud-crabs. International

buyer requirements vary by country, but generally buyers require Good Aquaculture Practices (GAqP) certification for producers and Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) certification for cold chain and processing facilities. Compared to neighboring countries, Myanmar’s competitiveness is relatively low with a limited percentage of produce meeting buyer requirements. Unfortunately, farmers have limited understanding and knowledge of how to qualify for GAqP certification and require hands-on guidance (USAID, 2021). Tables 6 and 7 present the countries importing aquaculture products from Myanmar and the value of the import markets for live and processed crabs (e.g., soft-shell) for the period of 2017-2021. It is important to highlight that most soft-shell crabs go to export markets, as domestic consumption is low compared to live crabs (USAID, 2021). Export potential for soft-shell crab is growing, with increasing demand and interest from countries like Thailand and Australia.

Importers

United States of America 8,407,00010,717,000 16,695,00015,984,000 14,738,000

Thailand 8,567,000 2,956,0003,180,0005,286,000 7,497,000

Hong Kong, China 2,265,0003,008,0004,392,000 2,728,000 4,199,000

China 19,019,0004,452,0001,616,000 2,867,000 3,926,000

Australia 956,000949,0002,046,0001,569,0002,559,000

Korea, Republic of 757,000 813,0001,335,0002,912,0001,924,000

Taipei, Chinese 1,746,000 1,588,000 3,766,0003,047,000 1,414,000

Japan 1,556,000 1,271,000 2,316,0001,852,000 967,000

United Kingdom 0 0 67,000 134,000 720,000

Singapore 1,014,000586,000942,000459,000641,000

Netherlands 0 0 042,000453,000

Malaysia 988,000 1,387,000 1,195,000463,000381,000

Viet Nam 632,000469,000636,000192,000295,000

United Arab Emirates 135,000220,000 475,000 164,000264,000

Norfolk Island

Belgium

Denmark

0 0 0 237,000

0 090,000132,000

0 099,000

New Zealand 87,000 140,000101,000145,000 78,000

Germany

Qatar

Sweden

Brunei

South

Türkiye

115,00064,000228,000

0114,00041,000

03,00015,000

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR

9 The Food and Drug Administration Department (FDA) of the Ministry of Health and Sports is the responsible entity for overseeing the quality of food, drugs, medical devices, and cosmetics in Myanmar. Importers (Value in USD) Exported value in 2017 Exported value in 2018 Exported value in 2019 Exported value in 2020 Exported value in 2021 World 10,336,00037,551,00040,230,00030,226,00046,405,000 China 9,972,000 32,800,00034,456,00028,103,00044,483,000 Thailand 364,000 4,576,000 5,268,0002,003,0001,645,000 Viet Nam 0 0 0 0201,000 Hong Kong, China 0 74,000487,000 120,00068,000 Singapore 06,000 0 08,000 Korea, Republic of 056,000 17,000 0 0 Australia 028,000 0 0 0 Japan 0 7,000 0 0 0 Taipei, Chinese 04,0002,000 0 0 Table 6. List of importing markets for live crabs exported by Myanmar (in USD value). Source (ITC, 2022).

Exported value in 2017 Exported value in 2018 Exported value in 2019 Exported value in 2020 Exported value in 2021 World 46,324,00028,802,00039,285,00038,057,00040,579,000

0

0

0 0

0 0

0 0

0 0 0 01,000 Austria 0169,000 0 0 0 Brazil 30,000 0 0 0 0

Darussalam 0 0 01,000 0 Chile 0 0284,000 0 0 Kuwait 5,00013,0003,0003,000 0 Philippines

0 0 India 0 06,000 0 0

Africa 45,000 0 0 0 0

0 03,000 0 0 Table 7. List of importing markets for processed crabs (e.g., soft-shell) exported by Myanmar (in USD value). Source (ITC, 2022). 21

Value Chain Ecosystem

Outside the value chain, key ecosystem actors play a crucial role in the functioning and development of the value chain. Government institutions (See Table 8) regulate the business activities in the sector by drafting and enforcing relevant regulatory frameworks. Government institutions support the value chain by operating state-owned facilities (e.g., hatcheries, laboratories, research centers) and by coordinating across agencies to promote the sector. In parallel, sectoral associations act as the businesses’ voices enabling public-private sector coordination and collaboration (See Table 8) (USAID, 2021).

Regarding service providers, in Myanmar there are no dedicated professional players providing business services and helping aquaculture players with support services. Training and capacity building in the sector is regularly provided by the DoF, NGOs and INGOs, and by foreign government experts. There are financial institutions (See Table 8) providing micro-finance and financial assistance to micro, small, and medium sized farms and enterprises. However, due to the limited reach of established institutions and the limited range of formal instruments, informal lending is the common source of finance in the sector (GGGI, 2019) (USAID, 2021).

Table 8. Key ecosystem actors in the value chain.

CategoryEcosystem Actors

Department of Fisheries (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation)

Livestock Breeding and Veterinary Department (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation)

juvenile crabs into the ponds to increase productivity. The farmers do not use fish feed in their operational practices. Crabs, shrimp and fish depend on natural food arriving in river water and from adjacent mangroves (GGKP, 2020).

Government

Food and Drug Administration Department (FDA) of the Ministry of Health and Sports

Department of Trade (Ministry of Commerce)

Fisheries and Aquaculture Department (Yangon University)

Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI)

Myanmar Fisheries Federation

Myanmar Shrimp Association

Myanmar Aqua-Feed Association

Associations

Myanmar Fish Farmers Association

Myanmar Crab Entrepreneurs Association

Myanmar Fisheries Producers Processors and Exporters Association

Myanmar Fish Paste, Dried Fish, Fish Sauce Entrepreneurs Association

BRAC Microfinance Institute

Financial Service Providers

Ar Yone Oo Microfinance Institute

Global Treasure Bank

Adapted from (USAID, 2021).

Since 2020 and throughout 2021, Myanmar and the aquaculture value chain have been affected by COVID-19 and political turmoil issues. COVID-19 has affected all stages of the value chain across the aquaculture sector (USAID, 2021). Especially at the beginning of the pandemic, the sudden drop in demand reduced sales in domestic markets (WAVES, 2020a); aquaculture exports started to get rejected and several orders were cancelled; the government enforced strict travel restrictions disrupting the supply chain; and storage costs increased due to reduced domestic and export demand (USAID, 2021). Operational challenges were faced by farms and processing plants, forcing them to cease operations. These operational challenges were further aggravated after February 2021, when political instability in the country resulted in almost all business and commercial operations being suspended (USDA, 2021).

New military-led authorities appointed the former Director General of the Ministry of Agriculture and advisor to a private company and the Myanmar Rice Federation as the new Minister of Agriculture, Livestock, and Irrigation. This provided assurance that major and unwanted changes will not occur (USDA, 2021). However, it is difficult to predict the policy changes and economic shifts of the current situation in the country, as well as the main impacts in the

development direction of the aquaculture sector. According to Reuters (2022), the United States has warned about the risks associated with doing business in Myanmar at this time and that utilizing supply chains could bring illicit finance, reputational, and legal risks (Reuters, 2022).

4.3. Current Production under Extensive Aquaculture Systems

Extensive mangrove aquaculture practices in Myanmar are similar to those in other Southeast Asian countries (e.g., Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Viet Nam). Farmers typically build low earthen walls around their mangrove area. The walls are constructed in the processes of digging ditches in the mangroves, which make shallow ponds for aquaculture. The farmers tend to keep mangroves on the remaining platform area within the pond walls, although the mangroves are often degraded or die due to the altered hydrology, as water levels are maintained at higher-than-normal levels for shrimp/fish, which reduces mangrove growth and can cause mortality. The ponds are periodically flushed with tidal water, which provides wild shrimp, crab, and fish larvae into the ponds. Many of the farmers also add shrimp fingerlings and

Extensive mangrove aquaculture systems provide multiple valuable products. In the typical mangrove aquaculture system, farmers use polyculture systems that include crab, shrimp, and other fish cultured together. Fuelwood collected from mangroves is the major energy source for domestic cooking in mangrove areas and buffer zones in the Delta. Mangrove fuelwood is also the main energy source used for drying fish on bamboo racks on the shore in the Pyapon township.

The coastal plain of the Ayeyarwady River is of relatively high elevation compared to the mean sea level (> 1.5 m – data determined from the Digital Elevation Model - CoastalDEM of Climate Central (Kulp & Strauss, 2019). Thus, the main farming season for extensive aquaculture farms in mangrove forests in the Region occurs from April to November every year, the period when there is significant rain and high tides to bring river water to the ponds. Most of the aquaculture ponds within mangrove areas are drained from January to March for cleaning and repairing the gates and pond walls for the next farming season. A few pond owners have dug deep ditches, which allows them to keep water all year round. However, from January to March aquaculture is not possible as river water cannot enter the ponds due to low tide levels and limited rainfall.

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR

Figure 4. Mangrove aquaculture pond with mangroves.

Figure 5. Brackish water pond without mangroves.

23

Pond owners in neighboring countries, where economic conditions and infrastructure are better, often build inlet and outlet gates made of cement and steel to keep pond water levels stable and to retain water for longer periods. Pond owners in Myanmar, on the other hand, usually make

simple water gates using soil and wood. Therefore, ditches, and pond walls are prone to leaks and breaks, requiring major maintenance or annual repair. This has increased annual pond maintenance costs and reduced aquaculture productivity.

A major limitation for aquaculture in mangrove saltwater and brackish water areas in Myanmar is the lack of affordable and good quality shrimp and crab larvae. Mangrove aquaculture farms in Myanmar are completely dependent on wild larvae that enters the pond along with water, or are wild caught. According to data from the European Union and the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development-funded

Myanmar Sustainable Aquaculture Programme (MYSAP), more than 134 million crabs are collected annually from the wild, with natural supply becoming limited over time (USAID, 2021).

Myanmar is a developing country with very limited infrastructure. Most of the coastal areas of the country do not have access to national electricity gridlines. Domestic cooking,

Figure 6. Concrete gate of brackish aquaculture pond.

Figure 7. Pond timber/wood gate, which is common in Myanmar.

Figure 8. Catching natural juvenile crabs for mangrove aquaculture ponds.

Figure 9. Catching natural shrimp fingerlings for mangrove aquaculture ponds.

Figure 6. Concrete gate of brackish aquaculture pond.

Figure 7. Pond timber/wood gate, which is common in Myanmar.

Figure 8. Catching natural juvenile crabs for mangrove aquaculture ponds.

Figure 9. Catching natural shrimp fingerlings for mangrove aquaculture ponds.

25SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR

especially in mangrove areas, mainly relies on fuelwood harvested from mangroves. Some fishing and seafood processing activities also use mangrove fuelwood as raw material for cooking, steaming, and drying. In addition, the construction of houses and coastal structures uses mangrove timber as the main raw material. As a result, the timber resources of mangrove forests have been depleted, while the demand for timber and firewood remains large.

In the Ayeyarwady Region, income from thinning and harvesting trees in mangrove ponds is an important source of income for pond owners. Survey results for the present analysis show that the average income from firewood is MMK 29,000 per acre per year (USD 13.76 per acre per year10). Despite their importance, mangroves in most of the aquaculture ponds are severely degraded, with scarce timber and firewood available for use. In the future, if the mangroves in these farms improve, the revenue from mangrove timber and firewood could increase significantly.

Results from the field survey also show that, in addition to extensive aquaculture systems (which are quite common in Pyapon), aquaculture households in the Labutta township have increased their farming in the direction of semiintensive farming. Typically, these households buy juvenile crabs to release them into their ponds, thereby exploiting a large number of wild and natural crabs continuously throughout the year. This practice is a common form of ‘natural crab fattening’. The following section presents the economic performance of multiple extensive aquaculture production models popular in the Region.

4.4. Cost-Benefit Analysis of Extensive Aquaculture Systems

4.4.1. Cost-benefit analysis for ponds without mangrove

The table below shows the benefits, operational costs, and capital expenditures for aquaculture practices in ponds without mangroves. Survey data on 133 aquaculture households in two townships, Labutta and Pyapon, shows that only eight households practice extensive aquaculture on ponds without mangroves (‘natural crab fattening’). For this type of aquaculture, the average area of aquaculture ponds was over 10 acres (4 ha) per household. For comparison purposes with other types of extensive aquaculture practices, the cost-benefit results are presented for 1 ha.

Table 9. Cost-benefit analysis for extensive aquaculture ponds without mangrove.

Item Value (USD/hectare/year)

Income 1,107.11

Operational Costs 649.13

Net Income 457.97

Capital Expenditures 982.79

Payback Period (years) 2.15 years

Note: Exchange rate applied: 1 USD = 2,107 MMK.

4.4.2. Cost-benefit analysis for ponds without mangrove (mangrove-friendly aquaculture)

Regarding extensive aquaculture ponds with mangroves, two main farming methods were identified based on the culture of aquatic species in ponds. The first type is polyculture, which is suitable for ponds with low altitude allowing to obtain and keep water at high level. The second type is crab-culture, which is suitable for both mangroves and crabs. The second type is usually conducted in areas of higher elevation, which makes land suitable only for crab farming and not for other species.

Of the 133 surveyed and interviewed households, 87 households practice crab-culture in ponds with mangroves. The remaining 56 households culture both shrimp and crabs in ponds with mangroves. The benefits, operational costs, and capital expenditures for the two types of farming are presented in the tables below.

Table 10. Cost-benefit analysis for polyculture aquaculture in ponds with mangroves.

Item Value (USD/hectare/year)

Income 1,079.83

Operational Costs 554.35

Net Income 525.48

Capital Expenditures 729.70

Payback Period (years) 1.39 years

Note: Exchange rate applied: 1 USD = 2,107 MMK.

Table 11. Cost-benefit analysis for crab aquaculture in ponds with mangroves.

Item Value (USD/hectare/year)

Income 1,415.10

Operational Costs 707.84

Net Income 707.27

Capital Expenditures 938.81

Payback Period (years) 1.33 years

Note: Exchange rate applied: 1 USD = 2,107 MMK.

Based on the economic performance of ponds without and with mangroves (Tables 9, 10 and 11), extensive aquaculture in ponds with mangroves provides greater monetary benefits than farming in ponds without mangroves. Considering that this cost-benefit analysis has not considered or presented additional information in terms of additional ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration and biodiversity benefits, among others, the recommendation of mangrovefriendly aquaculture practices at this point is based on its monetary benefits. In addition, it is also highlighted that crab aquaculture in ponds with mangroves is more ‘mangrovefriendly’, as there is no need to dig a deep pond and make ponds larger in proportion of the landscape (in comparative terms).

5. MANGROVE FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE PRODUCTION

5.1. Site Suitability Identification

This study has used three variables for determining suitable areas for mangrove-friendly aquaculture: 1) the land must be mangrove land; 2) the height above sea level must be suitable for the pond to be supplied with necessary water; and 3) the farming site must be located outside national parks and/or protected areas (natural reserves).

Regarding variable 1) ‘mangrove habitat’, maps of mangrove land, including nipa palm, were used and updated with the current mangrove status according to recent satellite images of mangrove land in the Ayeyarwady Delta (2022).

Regarding variable 3), national parks in Myanmar are places that have been assigned to protect biodiversity and natural resources, as well as to protect historical and cultural values. The exploitation and use of resources in these areas is prohibited. Consequently, national parks have been excluded for identifying suitable areas for mangrove-friendly aquaculture.

Finally, regarding variable 2) ‘elevation above sea level’, extensive aquaculture on mangrove land is completely dependent on tidal water. Therefore, elevation is one of the most important parameters in determining suitability for aquaculture on mangrove land. Tides, combined with increased river discharge due to rainfall, can enter the pond if the tidal height is greater than the height of the floor of the aquaculture pond. For this study, Climate Central’s Digital Elevation Model (DEM) CoastalDEM (Kulp &

Strauss, 2019) was used to determine the elevation of mangrove land in the Ayeyarwady Region, Myanmar. This model provides an accurate digital elevation model for coastal areas (mean vertical error is less than -0.03 m). The DEM limited version of the model has a resolution of 90 x 90 m (0.81 ha). Therefore, the study set a limit of minimum 1 ha for determining suitable areas in addition to the other selected criteria.

To determine suitable mangrove-based aquaculture farm’s using elevation above sea level, the study relied on tidal patterns in the coastal area of the Ayeyarwady Region. A suitable mangrove aquaculture zone should be an area where, for several months of the year, high tides can bring water into the pond. This selection of suitable aquaculture areas is consistent with the fact that the existing mangrove aquaculture ponds are located in this area. The tidal range in the Ayeyarwady estuary is 2-4 m (Ramaswamy & et al., 2004). The mean tidal range is 2.7 m at the Ayeyarwady River mouth (Kravtosa & et al., 2009). As a result, the study chose to assess land in three elevation classes: <2 m, <2.5 m, and <3 m above sea level for extensive shrimp and crab ponds (polyculture). The results of the analysis show that land <2.5 m above sea level is the most suitable land for shrimp/polyculture areas plus crab farming. The existing mangrove-based aquaculture ponds are also located within the suitability zone determined having an elevation of <2.5 m above sea level.

Unlike shrimp/polyculture farming, which needs ponds with extensive water surface and depth, mud crabs can develop in ponds with shallow trenches and limited cover of open water.

10 Exchange rate applied: 1 USD = 2,107 MMK. SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR 27

It is important to note that crab food mainly comes from mangroves. This ecological feature of mud crabs allows crab ponds to be located in mangrove land with less frequent tidal inflows than required for shrimp/polyculture aquaculture.

As a result, the elevation of land for crab ponds was higher by 0.5 m above sea level compared to land suitable for aquaculture of other species. Land suitable for extensive polyculture aquaculture should be less than 2.5 m above sea

level. On the other hand, suitable extensive crab aquaculture area can be from 2.5 m - 3.0 m above sea level.

A map of potentially suitable mangrove-friendly aquaculture areas is presented below. Table 12 presents detailed information about suitable areas for mangrove-friendly aquaculture for polyculture and crab-culture in the coastal delta of the Ayeyarwady River.

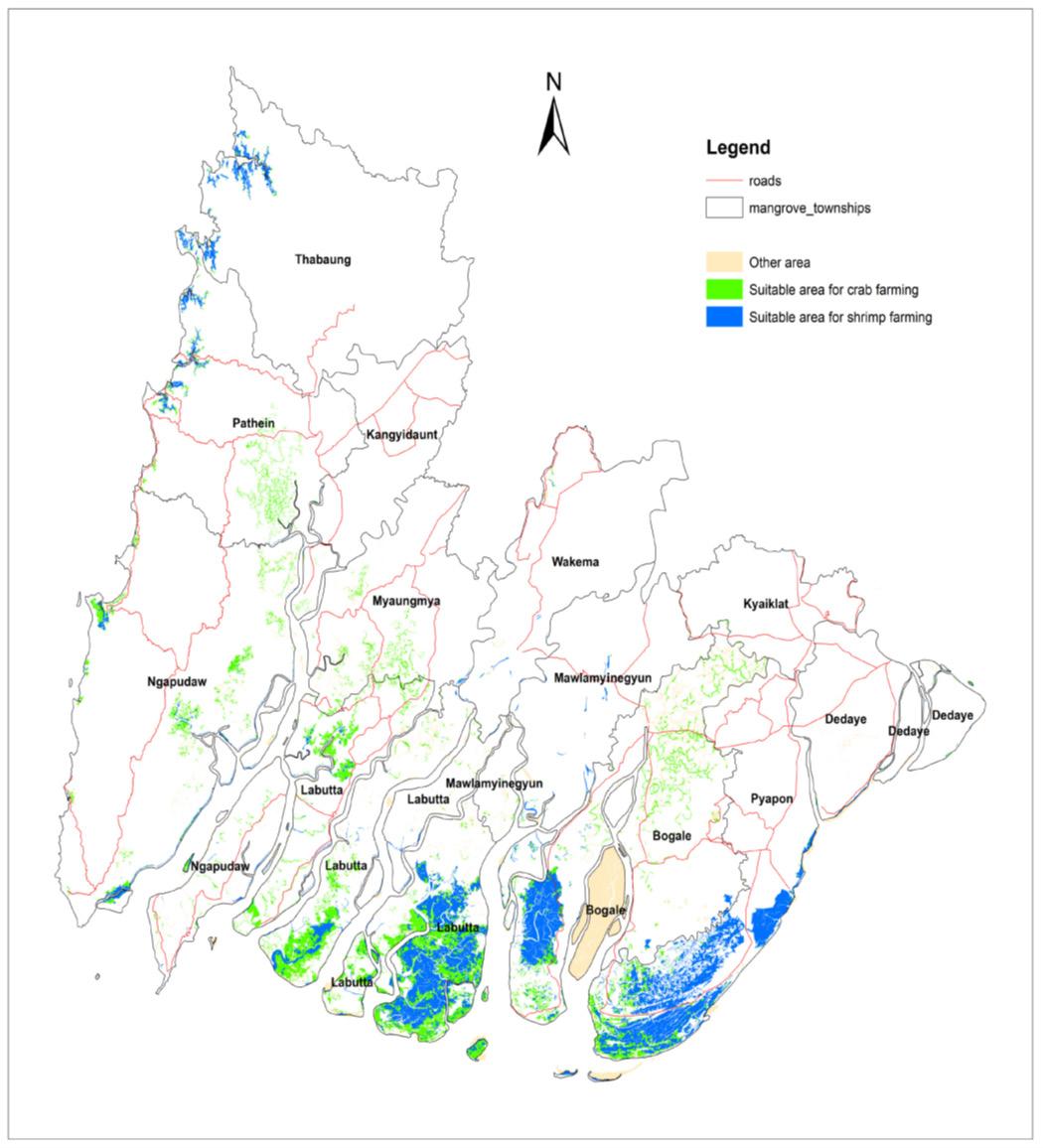

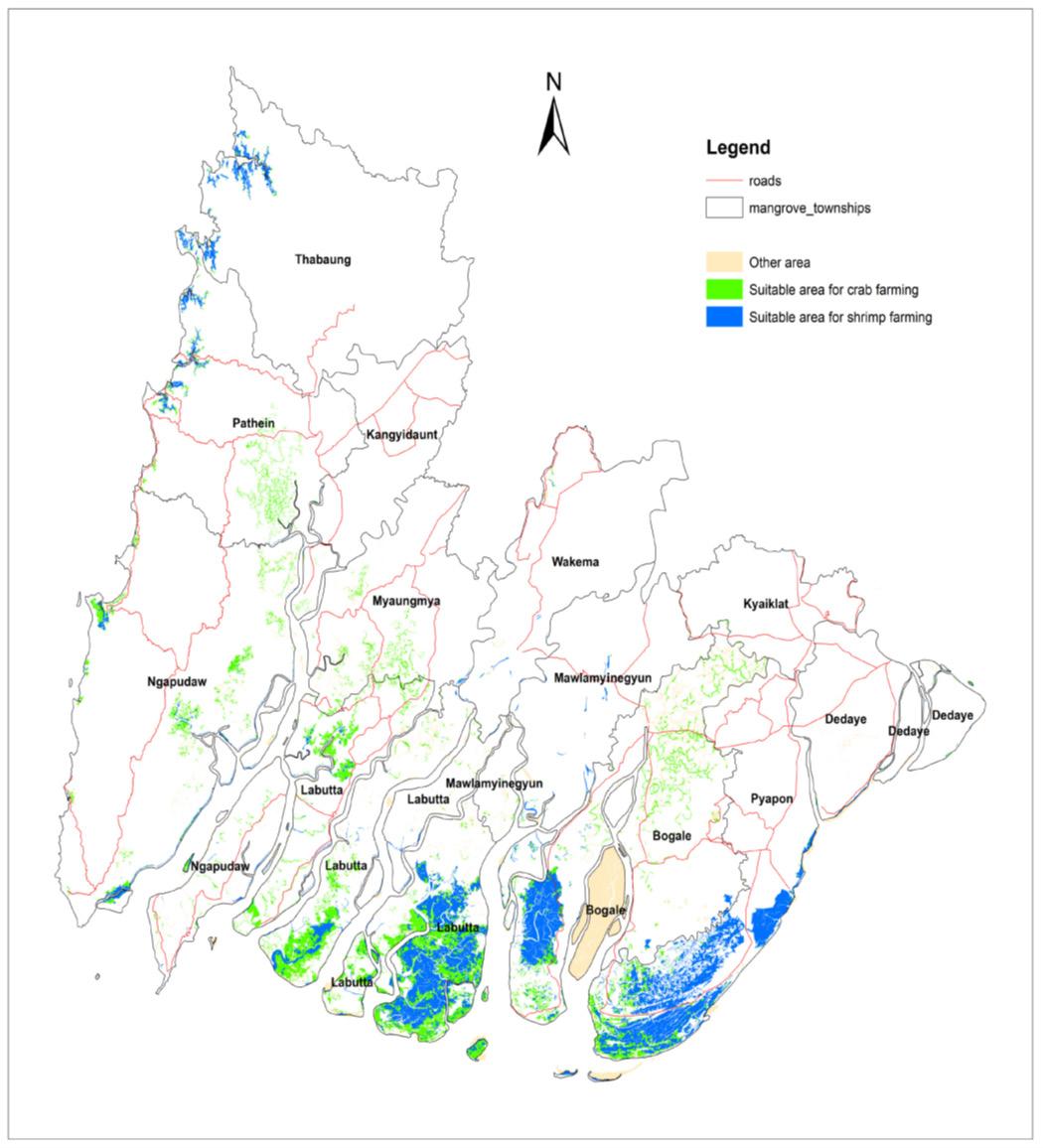

Figure 10. Map of potentially suitable areas for mangrove-friendly aquaculture in the Ayeyarwady Delta.

Township Mangrove land areas suitable for crab-culture (ha) Mangrove land areas suitable for shrimp and polyculture (ha)

Bogale 8,263 11,770

Dedaye 116 351

Labutta 31,719 26,277

Mawlamyinegyun 230 716

Myaungmya 2,107 101

Ngapudaw 5,718 2,283

Pathein 3,581 2,318

Pyapon 6,110 28,624

Thabaung 470 3,213

Wakema 89 283

Sum (ha) 58,403 75,935

Total area (ha) 134,338

The results of the table above show that suitable mangrovefriendly aquaculture areas on mangrove land are mainly concentrated in Labutta, Pyapon, and Bogale. Mangrove land, which is mostly concentrated in these three townships, falls, mostly, under ‘degraded mangrove’ type which correspond to mangrove areas that have been continuously exploited for fuelwood and timber.

The suitable areas for mangrove-friendly polyculture aquaculture in Labutta, Bogale, and Pyapon totals 26,277 ha, 11,770 ha, and 28,624 ha respectively. For crab-culture, the area in the three townships is as follows: Labutta –31,719 ha, Pyapon – 6,110 ha, and Bogale – 8,263 ha. The selection of suitable areas correspond to the criteria mentioned above; however, when selecting potential areas for the implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture, local social, economic, and political conditions should be carefully assessed as well as the value of intact mangroves for wild caught fisheries, biodiversity and coastal protection. Tradeoffs among aquaculture and the ecosystem services provided by extensive mangroves (in good condition) should be assessed and appropriate landscape planning, particularly for coastal protection and the maintenance of wild caught fisheries, should be implemented.

5.2. Investment Requirements for Mangrove Friendly Aquaculture Practices

The key investment needed for implementing mangrovefriendly aquaculture practices in the Ayeyarwady Region falls under three main categories:

1. Pond establishment: investment is needed for building ponds (digging and making pond walls) and concrete gates. The ponds should be designed and built to secure long-term (at least 5 years of useful life) and stable pond conditions for aquaculture. For this, it is also necessary to invest in fencing, as well

as acquiring proper tools and supplies for product management (e.g., baskets).

2. Mangrove plantations: mangrove rehabilitation is needed when establishing mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices. For maintaining mangrove cover in pond landscapes, environmental conditions need to be similar to that of natural mangrove habitats, which are dependent on intermittent inundation (rather than extended floodings). Mixed plantings could enhance diversity and productivity by keeping multiple species and canopy layers in ponds.

3. Capacity development: for implementing mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices in the Ayeyarwady Region, it is essential to teach, train, and support local farmers with technical requirements, design, and management of proper aquaculture and mangrove maintenance practices. Besides managing the pond from a technical perspective, farmers can increase their knowledge of value chains, finance and new technologies (e.g., solar drying of products) which can increase the sustainability of their businesses (GGGI, 2019).

5.3. Landscape Impact – Business as Usual vs. Mangrove Friendly Aquaculture

Mangrove-friendly aquaculture provides multiple landscape benefits, such as contributing to increasing mangrove health, biodiversity, the creation of green jobs, and livelihood improvement. In addition, healthy mangroves can play a significant role in coastal landscapes by mitigating climatic and environmental pressures such as storms, tsunamis, and sea level rise, while at the same time acting as powerful carbon sinks.

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR 29

Table 12. Suitable areas for mangrove-friendly aquaculture in different townships in the Ayeyarwady Delta.

Baseline

To determine the landscape impact of mangrove-friendly aquaculture in the Ayeyarwady Delta, this study has followed the 3Returns Framework. Following this framework, to assess the impacts of implementing mangrove-friendly practices (green growth interventions), it is necessary to clearly define a starting point, or benchmark, that will allow to analyze the potential changes in capitals based on the investment requirements defined above. Table 13 presents the results of the baseline valuation, upon which the implementation

of mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices in ‘pond areas on mangrove land’ (See Table 5) have been modeled. It is important to notice that for the baseline, some non-monetary benefits and capitals’ output indicators are valued as ‘zero’. This does not mean that there are no existing benefits or already existing stock in place. Instead, they have been valued at ‘zero’ to analyze the changes in capitals and benefits attributed to these categories based on the implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices. The baseline was built considering the current land use areas within the boundaries of mangrove land in the Ayeyarwady Region.

Aquaculture

Relevant Actions BAU Green Growth Scenario 1 Green Growth Scenario 2

Remain in the same condition

Implementation of mangrovefriendly aquaculture practices in suitable mangrove areas

Implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices in suitable mangrove areas and monetization of carbon sequestration

Benefit (monetary) (million USD)

Value of aquaculture

mangrove*)

Value of fuelwood cutting in degraded mangrove

Value

Operational expenditure (OPEX)

Non-Monetary Benefits (Unit)

5.3.2. Scenarios

To assess the impacts of implementing mangrove-friendly aquaculture in suitable mangrove areas and in ‘pond areas on mangrove land’ in the Ayeyarwady Delta, three scenarios have been analyzed.

The first scenario is a BAU scenario, which reflects what would happen if no mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices are implemented and mangrove areas continue to be used as in the current situation. In addition to this, two green growth scenarios are analyzed. The two green growth scenarios (Green Growth Scenario 1 and Green Growth Scenario 2) consider the implementation of mangrove-friendly aquaculture practices for polyculture and crab-culture in suitable ‘pond areas on mangrove land’ – 38,269 ha identified. Green Growth Scenario 2 also considers the potential monetary impact of prioritizing more ‘mangrove friendly’ aquaculture (crab culture) and from monetizing carbon sequestration through carbon credits. Key considerations and assumptions for modelling the three scenarios are presented in Annex 1.

5.3.3. Return on Investment Analysis

Following the 3Returns Framework and considering the key investment requirements described in subsection 5.2., investment for ‘pond establishment’ has been analyzed as investment in ‘Financial Capital’ for the three scenarios. For the two green growth scenarios, investment in ‘mangrove plantations’ was analyzed as investment in ‘Natural Capital’ while investment in ‘capacity development’ was analyzed as investment in ‘Social & Human Capital’. Benefits from these investments were modeled and are reflected through the monetary benefits and operational costs, as well as through non-monetary benefits (i.e., carbon sequestration, green jobs, and species diversity), and capital output indicators (i.e., area of mangrove-friendly aquaculture, people provided with training, and the value of production assets). Changes in capitals and benefits have been modelled for each scenario based on the conditions, considerations, and assumptions described in Annex 1. To be conservative, the analysis has considered an analytical period of 20 years 2022-2042. Table 14 presents the investment analysis results in USD.

Financial Analysis

Benefit (monetary - PV) (million USD)

BAUGGS1 GGS2

Value of aquaculture (unimproved mangrove) 477.47 0.00 0.00

Value of aquaculture in mangrove-friendly ponds (polyculture) 0.00 354.10 151.76

Value of aquaculture in mangrove-friendly ponds (crab-culture) 0.00 198.88 464.06

Value of fuelwood cutting 32.27 38.94 42.99

Value of biomass carbon sequestration 0.00 0.00 32.12

Value of coastal protection 242.17 419.71 588.79

Operational expenditure (OPEX - PV) (million USD)

Aquaculture pond operational costs (non-mangrove) 326.66 0.00 0.00

Aquaculture pond operational costs (polyculture) 0.00 181.40 77.74

Aquaculture pond operational costs (crab culture) 0.00 82.00 191.34

Fuelwood cutting operational costs 5.16 6.23 6.88

Operational costs for carbon credits 0.00 0.00 1.61

Capital expenditure (CAPEX - PV) (million USD)

Mangrove plantations 11.11 22.22 33.33

Capacity development (training - mangrove-friendly practices) 0.00 1.54 1.54

Aquaculture pond establishment 3.93 27.09 27.04

Net Benefits (monetary - NPV) (million USD) 405.04 691.15 940.23

Financial Analysis (indicators)

Benefit-Cost Ratio (BCR) 2.17 3.16 3.77

Return on Investment (ROI) 27.92 14.59 16.19

Non-Monetary Benefits (Unit)

Total carbon sequestration (MtCO2e) 2,779,439 3,340,416 3,887,804

Number of 'green jobs' (# of FTE people by 2042) 1,233 2,667 4,000

Species diversity (Shannon index for mangrove-friendly ponds) 0.195 0.250 0.250

Status of Capitals (Output Indicators - Unit)

Natural Capital (total mangrove-friendly aquaculture area - ha) 33,997 50,169 50,169

Social & Human Capital (number of people provided with training) 0 8,265 8,265

Financial Capital (production assets - PV million USD 2022) 3.93 27.09 27.04

Note: PC – Present Value. NPV – Net Present Value. FTE – Full-Time Equivalent. Ha – hectare Avg. – average. *Monetary results presented in the table have considered a discount rate of 7% -interbank interest rate (Central Bank of Myanmar, 2022). *Exchange rate applied: 1 USD = 2,107 MMK.

SUSTAINABLE MANGROVE-FRIENDLY AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT – MYANMAR 31 5.3.1.

Value

(unimproved

46.06

2.77

of coastal protection 7.53

(million USD) Aquaculture pond operational costs 24.84 Fuelwood cutting operational costs 0.44 Net Income (million USD) 31,08

Total carbon sequestration (annual MtCO2e) 99,737 Number of 'green jobs' (# of FTE people) 0 Species diversity (Shannon index for mangrove-friendly ponds) 0.195 Status of Capitals (Output Indicators - Unit) Natural Capital (total mangrove-friendly aquaculture area - ha) 0 Social & Human Capital (number of people provided with training) 0 Table 13. Baseline valuation of pond areas on mangrove land for implementing mangrove-friendly aquaculture (2022). *Note: Aquaculture ponds with ‘unimproved mangrove’ include ponds with degraded mangroves, secondary and regrowth mangroves, nipa palm, and without mangroves. Exchange rate applied: 1 USD = 2,107 MMK.

Table 14. Return on investment analysis 2022-2042 (million USD).