HEADQUARTERS

Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust Slimbridge, Gloucestershire GL2 7BT wwt.org.uk membership@wwt.org.uk

Registered Charity No. 1030884 and SC039410

CENTRES

For full location, address and contact details, visit the individual centre pages on our website – wwt.org.uk/visit

WWT Arundel 01903 883355

WWT Caerlaverock 01387 770200

WWT Castle Espie 028 9187 4146

WWT Llanelli 01554 741087

WWT London 020 8409 4400

WWT Martin Mere 01704 895181

WWT Slimbridge 01453 891900

WWT Steart Marshes 01278 651090

WWT Washington 0191 416 5454

WWT Welney 01353 860711

WATERLIFE

The magazine of WWT For WWT

Managing editor: Emma Faure, waterlife@wwt.org.uk

Editorial board: Tomos Avent, Jon Boardman, Helen Deavin, Andrew Foot, Geo Hilton, Peter Lee, Elliot Cassley, Chris Harris For Sunday Consultant editor Sophie Sta ord Head of content Lucy Ryan Chief sub-editor Emma Johnston Lead creative Rob Hearn Senior designer Emily Black Group account director Emma Franklin Content and creative director Richard Robinson

Contributors: Amy-Jane Beer, Paul Bloomfield, Mark Cocker, Dominic Couzens, Barney Jeffries, Derek Niemann

Front cover: nixic/istock; © and TM Aardman Animations Ltd 2024

Waterlife is printed by Acorn Web O set Ltd on Leipa ultraMag Gloss, an FSC® certified paper containing 100% recycled content.

THE OTHER DAY I WAS sitting in a hide at Slimbridge, watching two of our volunteers work their magic. They had a telescope trained on a bird in the distance. As visitors came in, they encouraged them to look through the eyepiece. Seeing a beautiful spoonbill “up close” made the day for all those visitors.

Those volunteers demonstrated how each of us can speak up for wetlands in our own way – whether it’s by showing people something amazing to inspire them, making a mini-pond in a garden (see page 40), or signing our campaign to get toxic lead shot banned (page 11).

So far, over 12,000 supporters have called on the Secretary of State to #BanLead – we’re getting noticed. Thank you, your continued membership support is vital to achieve our mission to restore wetlands and unlock their power. We can’t do it alone – we need you!

And your support is taking our work into exciting new areas. We recently announced plans to create a new saltmarsh nature reserve on the Awre peninsula on the Severn Estuary. Saltmarshes are a haven for threatened wildlife, slow down flood water and store vast amounts of carbon that can help counter the e ects of climate change. Don’t miss Mark Cocker’s lyrical spotlight on this crucial habitat on page 14.

We’re also working with partners to explore the feasibility of reintroducing the magnificent white-tailed eagle back into Wales and the Severn Estuary – see page 13.

Spring is an exciting time to visit your local WWT centre. Nature awakens and bursts into colour and wildlife spurs into action for the breeding season. Discover what you can see and do in our wetland worlds on page 4, and plan your next visit. Dive in to find out more…

Views expressed in the magazine do not necessarily reflect those of WWT.

ISSN: 1752-7392

Sarah Fowler, Chief Executive

09 Spring fun

Aardman presents Lloyd of the Flies Wetland Bug Hunt. 35 Open access

WWT Director Anita Eade on prioritising wetlands for all

42 Life force

How

wonderful ways support so much life.

shots

See stunning images by our photography competition winners. 40 Joint action Come together to take action for wetlands.

Dive into unforgettable wetland experiences at your local centre this spring and summer. See new life emerge, wildflowers bloom and dragonflies dart, and dip beneath the surface for minibeasts. The more you look, the more you’ll see…

Kingfisher

Marvel at the river king Kingfishers can be a glimpsed blue flash or a blur by the water if you’re lucky. But your chances of observing them in more detail are much higher around the nesting banks at many WWT centres this spring and summer. During the breeding season between late March and July, the area around a kingfisher’s nest hole is consistently busy. These birds have five to seven chicks to feed, so a pair could be catching and bringing back around 100 fishy meals every day between them. That’s a lot of coming and going, and they’ll o en announce their presence by calling to each other as they head for the nest with a beakful of food. You might see one parent perching on a nearby branch showing its ice-lolly orange front as it waits for its mate to finish a feeding drop, before it enters the nest itself. Discover the locations of our nesting banks before you visit. See your local WWT centre’s website for details.

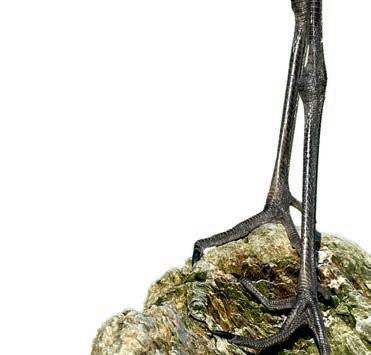

Don’t be fooled by its name – the grass snake is a true water serpent, a sinuous swimmer on the hunt for fish, frogs, newts and toads. Sometimes it stays below the surface, but if you’re very lucky you might spot one at our reserves holding its head up, tasting the air for amphibians. Seeing one of these metre-long reptiles, with its distinctive yellow and black collar, takes both luck and stealth. Be very quiet, for this gorgeous snake will glide away at the slightest disturbance.

See what’s on

Explore all our events and activities wwt.org.uk/ member-visit

Discover mini-beasts in our ponds

Who needs mythical monsters when dragonfly larvae are waiting in our ponds? Discovering one of these mini-beasts is the highlight of any pond-dipping experience. Its extendable mouth parts alone are the stu of fantasy fiction. And as for those big, beady eyes… Pond dipping is open to visitors across all sites (dates and times vary, check online) and experts are on hand to help you turn your nets into tools for exploring the world within water.

All of our WWT sites grow a rainbow of blooms in the summer, as spectacular and pretty plants burst into flower. On ditches and in margins, bright-yellow marsh marigolds look like supersized buttercups, while flag irises add to the sunshiny colour of spring. Surrounding wet meadows o er up the bright pinks and purples of marsh and common spotted orchids.

Enjoy the riot of flowers on display at our sites, changing by the season, with self-guided or expert-led walks. Check your local centre’s website for details.

Mother mallards are like sheepducks trying to round up their young and keep them safe. To see one guarding flu y ducklings little bigger than your fist is as cute as it gets. She swims slowly, calls so ly, and her gaggle peep in answer and attempt to stay close. You can see many di erent waterbirds raising families on our reserves. As the days go by, their young learn how to feed and fend for themselves.

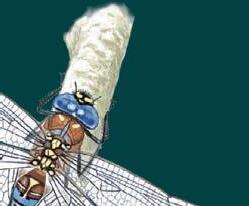

A hunter in pursuit of hunters, there is one elegant falcon whose arrival causes a stir among wildlife and people alike. Kestrel-sized, with a shorter tail and creamy cheeks, the hobby’s long, narrow, pointed wings o en result in it being taken for a giant swi . This summer visitor from Africa relies on remarkable aerobatics to catch prey, and is even able to outmanoeuvre dragonflies, the most agile of insects. What a thrill to witness a mid-air snatch and grab, as the bird speeds towards its prey, locks talons around the hapless dragonfly and proceeds to eat it on the wing. Flying ants, beetles and moths are also on the hobby’s mid-air menu and, once the young hatch, the parents switch to birds such as young and inexperienced martins, starlings and finches.

Breeding pairs need healthy wetlands for their steady supplies of insect food. Our sites in southern Britain give you an increased chance of seeing hobbies, as they’re rarer breeders further north. Check your local site’s Latest Sightings page online for updates.

Our wetlands always attract rare visitors in spring and summer. Last May, WWT Steart Marshes was treated to four days of the scarce woodchat shrike, while WWT Welney hosted the rare Savi’s warbler for eight days in June. WWT Llanelli also had a thrilling four days the same month hosting not one but two Caspian terns. What will this season bring?

Check your local WWT centre’s Latest Sightings page regularly to see what species are on the reserve.

Courtship and competition are written in the sky when lapwings begin their strictly bird dancing display flights. We get giddy just watching from the ground!

Embrace feathered finery

Spring is the time to see our waterbirds in their finest feathers. For many species, the brighter and more striking the plumage, the more appealing it is to the opposite sex. From changing colour to sprouting extravagant plumes, crests and ru s, our waterbirds put on their best. Don’t miss the feathered fashion show!

Even before they rise into the air, the birds exude grace, tiptoeing like ballet dancers up to the barre, striking poses, dainty crests up.

Once airborne, a bird turns to show its alternately patterned upper and lower parts, flashing light-dark-light-dark in a zigzag

flight pattern. The wingbeats slow, so that it flickers like a butterfly. Then it climbs, rolls onto its back and stalls, plunging towards the ground, before pulling up and away at the very last minute.

For much of this performance, the display is accompanied by song, the bird giving its strange whooping “peewit” call. What is this show for? In most cases it’s a territorial dispute between males – you may see one bird chasing the other. Song flights happen throughout the breeding season at nearly all WWT centres. Crossed fingers, you’re in for a treat!

See more breeding colours by scanning the QR code above.

Explore incredible insect worlds with Aardman

Dive into the wonderful world of wetland insects with Lloyd and his new friend Dart the dragonfly (WWT’s enthusiastic tour guide). Find characters from Aardman’s animated comedy series Lloyd of the Flies including houseflies Lloyd and his little sister PB, and his best friend Abacus the woodlouse. You can also enjoy familyfriendly pond dipping, mini-beast hunting, and other insect activities during weekends and holidays.

Download a special augmented reality app to shrink down to fly size and see the world through insect eyes! You will be prompted to input a location code. This will be available in the centre when you visit.

Sat 5 April - Sun 1 June at Arundel, Castle Espie, Llanelli, London, Martin Mere, Slimbridge and Washington.

Before you visit, download the app for free on Google Play or App Store. Search for Bug Hunt.

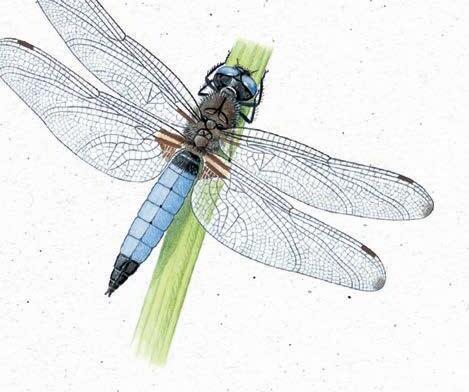

Join us for a Summer of Dragonflies!

Visit all summer long from 21 June and be transported to the fascinating world of dragonflies at your local centre. We’ll have wondrous experiences and activities to dart between that are fun for all ages. Put a date in your diary to meet flying-world royalty this summer.

“We want to bring our wetlands to life with unique and fun experiences for all ages. So, we’re delighted to partner with Academy Award-winning animation studio Aardman to help you explore our extraordinary insect life. Be the first to see Dart the dragonfly and start to spot all these creatures at our sites, at school and outside. By connecting you to these creatures, we hope you’ll learn all about them and be inspired to seek out more.”

Anita Eade, WWT Director

Plan your next visit

Find out what’s on and dive headfirst into new adventures at your local WWT centre. Explore our inspiring activities and events and discover a world of head-turning wildlife with every visit.

Go to wwt.org.uk/ member-visit or scan the QR code.

Godwit appeal update: a huge thank you!

WWT and partners have begun a new 10-year plan, which includes Godwit Futures, to secure the survival of the black-tailed godwit in the UK through the world’s first conservation breeding programme for the species.

This new phase builds on the success of Project Godwit, a collaboration between WWT and the RSPB, funded by EU LIFE, which released 206 hand-reared chicks in the Fens of East Anglia as part of the UK’s first wader headstarting trial, boosting the Ouse Washes population by 800%.

Godwit Futures was kickstarted

through a major grant of £400,000 from Natural England.

Godwit Futures aims to increase the UK population to 80 breeding pairs across multiple sites around the UK by 2033, in line with the National Action Plan. As part of the National Working Group, chaired by Natural England, WWT will help identi , restore, create and protect a range of suitable wetland sites to host newly created godwit populations.

In 2024, we collected eggs from sites in the Ouse and Nene Washes that were under threat from flooding and predation. These then hatched at WWT Welney, with 29 birds released into the wild to boost populations and 20 taken to WWT Slimbridge to establish the conservation breeding population. The captive birds will be managed and their o spring released across the UK to bolster small godwit populations and create new ones. Under current plans, up to 25 captive-bred birds will be released per year with 20 staying at the centre for breeding.

“WWT is a conservation organisation of doers, and that’s exciting,” says WWT Project Manager and Lead Aviculturist William Costa.

Thank you to everyone who has donated to our winter appeal. The appeal focused on the plight of the black-tailed godwit – which is red-listed in the UK – and our vital work to boost its numbers here. Your generosity never fails to amaze us and we’re delighted to report that so far you have raised over £150,000

(including Gi Aid), which will help us manage the world’s first conservation programme for black-tailed godwits at our Slimbridge site (see details above) and will help us with projects in their breeding grounds and along their flyway down to west Africa.

“With species recovery projects like this, we take action to reverse decline. Black-tailed godwits are charismatic wading birds that can live for more than 20 years. It is fascinating following the individuals as they migrate to west Africa and return to our Welney centre to breed each year, and to see the populations in the Fens stabilising and increasing. We hope this project continues this positive news story.”

Godwit Futures is a partnership between WWT, the RSPB and Natural England.

Join our campaign to ban lead ammunition in the UK. WWT Senior Campaigns Manager Mark Robinson explains why we must take action

Lead ammunition – what’s the problem?

Every year, 7,000 tonnes of toxic lead ammunition is shot and scattered into the environment. Here, it poisons people, wildlife and wetlands, climbing up the food chain and contaminating the soil for generations to come.

Up to 100,000 waterbirds lose their lives annually in the UK from ingesting poisonous lead shot, and a million in Europe. As game birds are shot with lead ammunition, this toxic substance finds its way onto our dinner plates and into our pet bowls, posing a risk to humans – particularly children –and companion animals.

There are no safe levels of lead exposure. But, in 2025, this dangerous substance is still being pumped into our environment.

What’s WWT doing about it?

Lead ammunition poisoning is a scandal WWT has campaigned about for decades. Now we have a chance to help end the era of lead for good.

7,000 tonnes of lead ammunition is discharged into the environment every year – the weight of the Eiffel Tower.

93% of pheasants destined for human consumption were killed using lead ammunition during the last hunting season.

100,000

waterbirds in the UK die every year from consuming poisonous lead shot, mistaking it for grit or seeds.

Join our call for a ban Scan the QR code above for our simple tool to ask the government to ban lead ammunition.

With recommendations from a UK Health and Safety Executive review on lead ammunition now published, the new Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural A airs, Steve Reed, has an opportunity to consign this toxic substance to history. Evidence shows that voluntary e orts to move away from lead ammunition and the current, partial regulations have failed. It took policy to remove lead from petrol, paint and pipes, and it will take policy to remove it from ammunition. That’s why we’re calling on Steve Reed to take the right call and ban lead ammunition for good.

How you can help

Now is the time to end this scandal –but we need to show Steve Reed that the public backs a ban. Use the QR code above to make your voice heard.

Thank you, dear members

Your continued membership helps to protect and restore our wetlands and the incredible wildlife they support – and when they thrive, so do we. We simply couldn’t do our work without you, and we can’t thank you enough. Remember, membership o ers great value with unlimited, free entry to all 10 of our sites across the UK. With so many wetland worlds to explore and natural wonders to marvel at, get ready for adventure on your next visit.

Book a bus to Slimbridge

We’re big fans of car-free travel – but we know getting to our centres on public transport isn’t always easy. So, we’re delighted that visitors can now reach WWT Slimbridge via the Robin bus service.

Run by Gloucestershire County Council, the Robin is a low-cost pre-booked bus service – think of it as being like Uber’s big brother! Using an app or phone number, you can book a ride to Slimbridge from anywhere in the Berkeley Vale area, including the nearest railway stations.

Lucy Smith, WWT’s Head of Sustainability, says: “The Robin bus increases access to our wonderful wild spaces and also promotes sustainable travel. We can’t wait to welcome you to Slimbridge.”

Sign up to our emails for all the latest wetland news Keep up to date, by email, with what’s happening at all of our sites, wondrous wildlife, super science, amazing wetland experiences and how your support is helping wetlands. To sign up, simply scan the QR code or visit wwt.org.uk/ stay-tuned for the latest news.

Thanks to a £21 million donation from Aviva towards restoring 250 hectares of saltmarsh on the Severn Estuary, WWT is creating a new 148-hectare saltmarsh nature reserve on the Awre peninsula in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire. The sale of land for the project was agreed at the end of last year a er two years of research and negotiation with landowners.

Awre peninsula, Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire

Drawing upon the success of WWT Steart Marshes, WWT’s ambitious plan for the new saltmarsh reserve will see an engineered breach in the sea wall to allow saltwater from the estuary onto the land to create a mosaic of wetland features and habitats supporting a huge variety of plants and animals. As well as being a haven for wildlife and a nature reserve for the

local community, the area will act as a hub for new research into the superpowers of saltmarsh to store carbon, boost biodiversity and improve flood resilience in an area of low-lying farmland that is prone to flooding. “This is the best site on the Severn Estuary for saltmarsh restoration,” says WWT Deputy Chief Executive Kevin Peberdy. “Our intention is that this new reserve will be an asset for the community, bringing a wealth of wetland wildlife and a new way to connect with nature – as well as an upgraded flood defence.”

Britain’s largest bird of prey could soon be returning to Wales if a new species reintroduction plan takes o .

White-tailed eagles, also called sea eagles, were persecuted to extinction in the UK more than 150 years ago. But populations have been reestablished in Scotland, Northern Ireland and southern England – and now we’re planning to bring these magnificent birds, with their 2.4-metre wingspan, back to Wales.

In partnership with Eagle Reintroduction Wales, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and Gwent Wildlife Trust, WWT is working to reestablish a viable

breeding population of whitetailed eagles on the Severn Estuary. WWT will provide its expertise in species reintroduction, as well as supporting workshops to address people’s questions and concerns.

“Reintroduction projects take time and extensive planning,” says WWT Senior Project Manager Eric Heath. “WWT is excited to be involved at this early stage of the journey to restore the iconic white-tailed eagle back to our skies and waterscapes.”

More than 150 pairs now breed in Scotland, and white-tailed eagles reintroduced to the Isle of Wight were spotted last year at WWT Arundel.

Our wetland conservation work with communities in Madagascar received a big boost thanks to a £197,000 grant from the Global EbA Fund that supports ecosystem-based adaptation. For people on the frontline of the climate crisis, wetlands are vital allies, helping to protect against droughts, flooding and extreme weather. The grant will provide communities with the funding to build resilience and adapt to climate change by managing their wetlands.

WWT has been present in Madagascar since 2009, working with local people to protect important wetlands and the unique species they support.

As our sites celebrate big anniversaries, we take stock

WWT Washington, 50 years: Since it opened in 1975, close to three million visitors have enjoyed a blue-green space that boasts one of the region’s most diverse habitats. Avocets, curlews and willow tits are among the species attracted to the site. “We’re incredibly proud of this milestone and what it means for the area. It’s an inclusive haven for wildlife and people,” says Centre Manager Gill Pipes.

WWT London, 25 years: Opened by Sir David Attenborough in 2000, the reserve is a natural haven for wildlife and people in the heart of the capital.

Centre Manager Alexia Hollinshead is proud that the centre has welcomed thousands of people who wouldn’t normally get the chance to experience nature thanks to inclusive initiatives with schools, the Inspiring Generations scheme, the Generation Wild programme and last year’s Universal Tax Credit ticket. “In a time when urbanisation o en distances people from nature, WWT London is as a beacon of hope,” says Alexia.

WWT Martin Mere, 50 years: Martin Mere has much to celebrate: the highest count of pink-footed geese (45,800) in October 2014; the creation of reedbeds for guests to walk through in 2017; and bittern breeding success.

“We’ve restored a lost lake into a thriving wildlife sanctuary and helped connect people to nature. We can’t wait to see what the future holds,” says Centre Manager Nick Brooks.

Saltmarshes are among our rarest habitats and they teem with wildlife all year round. Now, WWT is on a mission to unlock their carbon-storing, flood-busting superpowers

JMark Cocker is a multi-awardwinning author and naturalist who writes and broadcasts on wildlife in a variety of national media

ust imagine the scene. On leisurely wingbeats, a hen harrier quarters the grey-green vegetation that stretches to the sea. From nowhere, a flock of panicking waders and wigeon rises into the air, flushed by its approach. The ducks instantly swerve away in a tight globe of anxious, whistling calls, but the waders – redshanks, dunlins, godwits, plovers – steeple higher above the skyline.

They jink and twist across the blue – the whole flock winking dark then light as the sun gleams alternately on the upper and undersides of 200 outstretched wings. Just as suddenly as it materialised, the flock plumps back down to the ground and vanishes. Completely.

That trick is part of the magic of saltmarsh, but it also graphically illustrates the duality at the heart of this remarkable landform. Saltmarsh is both land and sea. It may look level, and even rather featureless, but much of the drama takes place below the horizon where deep creeks incise and wriggle through the body of the place, creating an elaborate sub-surface

“

Like a system of arteries, the silt-filled channels pulse with tidal seawater.

network that is essential to saltmarsh health. Like a system of arteries, the silt-filled channels pulse with the lifeblood of the estuary, tidal seawater, twice a day.

Saltmarsh is a rich and dynamic habitat, but it’s also rare. There are only 50,000 hectares in Britain, much of it found in some of our most important estuaries – in Essex, on the Wash, along the north Norfolk coast, on the Ribble, Morecambe Bay and around the Humber, Severn and Solway. Furthermore, less than two thirds of these areas are judged to be in a healthy condition. Despite this, they are crucial for wildlife.

The saltmarsh lying closest to the land is beyond the reach of all but the very highest tides. Some birds, such as the amber-listed redshank, routinely nest in this zone. Yet other wetland species – geese, ducks, herons, waders, gulls and rails, as well as wintering predators including hen harriers and short-eared owls – flock to these drier areas to feed, and to roost during high tides.

The areas closest to the tide edge are routinely inundated with seawater. This zone is enormously rich in marine invertebrates, so it’s no surprise that it serves as a feeding area for fish including herring and sea bass.

At a slightly higher elevation is the heart of the habitat. It’s home to a suite of remarkable plants that

are tolerant of being submerged in saltwater, yet equally capable of thriving on dry land. They are, in many ways, the architects and creators of saltmarsh.

They include sprawling bushy species such as shrubby seablite or the more delicate, mud-loving samphire, which is fleshy, succulent and relished as a delicacy akin to a brine-bursting tenderstem broccoli.

Squeezed by flood defences that may appear to be a greenish-grey at first glance, healthy saltmarsh in fact becomes a riot of colour and variety in spring and summer, most notably. Green, white, yellow, orange, red, purple and pink blooms carpet the landscape thanks to saltmarsh’s rich and diverse vegetation.

Dr Hannah Mossman, who has worked with WWT’s research team at Steart Marshes in Somerset, has helped make important discoveries that she believes will convince any saltmarsh sceptics.

At the current rate of rising sea levels, all current saltmarshes could disappear from south-east England by 2040 and the whole of the UK by 2100 unless we give them space.

“Saltmarsh is such a cool landform,” says Hannah. “Not only is it great for nature, it’s brilliant for people, too.” This is because saltmarsh can store vast quantities of blue carbon, so called because of the role the sea plays in its production. She explains: “As saltmarsh plants grow, they photosynthesise, extracting carbon from the atmosphere. In autumn, the plants die back and are buried beneath silt and debris washed up on the high tide.

it’s because beneath silt and debris washed up

In spring, vibrant green plants grow from seeds and sediment left by the previous year’s tides. Their photosynthesis turns CO2 from the atmosphere into more plant matter.

The UK’s coastal saltmarshes are incredible habitats that do different things throughout the seasons. Because they’re so dynamic, they’re valuable for a huge range of wildlife – and people. Crucially, they help us combat climate change by storing CO2 as blue carbon. Here’s how…

On a saltmarsh, the tides change conditions daily. Spring and autumn bring the most extreme high and low tides.

Cross-section layers of a coastal ecosystem, and how a saltmarsh landscape buries blue carbon

Come autumn, saltmarsh plants release their seeds, feeding ducks such as teal and shelduck. Carbon is stored as higher tides inundate the saltmarsh, bringing in fresh sediment that buries decaying plants in the mudflats. This traps the carbon, preventing it from being released back into the atmosphere.

In summer, the saltmarsh is full of life with blooms of colourful pink sea aster, golden samphire and purple sea lavender. CO2 continues to be absorbed. Thick green grasses provide nesting space for redshanks and skylarks.

By winter, rich silt covers many plants, burying carbon for thousands of years. Huge flocks of wading birds seek out these unusually reliable foraging grounds – because the salt in the mud stops saltmarsh from freezing, they can find invertebrate prey year-round.

“The waterlogged conditions prevent the plants from decomposing and lock their carbon content underground, e ectively storing it in deep vaults of buried mud. Saltmarsh is far more e ective – 40 times faster –at capturing atmospheric carbon than forest. Our research shows that it can bury organic carbon at a rate of up to 70 tonnes per hectare every year – the same as planting a million new trees or taking 32,900 cars o the road.”

WWT has launched a major wetland restoration campaign to improve and create saltmarsh, partly for its carboncapturing ability but also because of all the other benefits it provides. The slow-ascending gradient and the vegetation created in a saltmarsh act

“

Our goal is to show that working with nature is the best way to help ourselves.

Saltmarsh is far more effective – up to 40 times faster – at capturing atmospheric carbon than forests.

as an important so defence against the sea, absorbing wave energy and protecting coasts and human communities from the e ects of sea-level rise. With its vast open skies, it also helps support people’s physical and mental health by giving them access to green-blue space.

But saltmarsh is under threat. It’s being lost at a rate of about 100 hectares a year in the UK, mostly due to storm surges. So, WWT is demonstrating how precious this

habitat is. “Our goal is to show that working with nature is the best way to help ourselves,” explains Dave Paynter, Reserve Manager at WWT Slimbridge. “Saltmarsh is a fantastic counterbalancing force when tackling climate change, but it’s more than that. It’s a self-regulating, self-creating habitat that is as close to wilderness as any landform in Britain.”

Dave amplifies this holistic vision: “At Slimbridge and on the upper Severn Estuary, WWT’s long-term goal is to restore and develop new saltmarshes to make our area more resilient.

“As I look out and see the estuary crisscrossed by huge flocks of birds –thousands of gulls going to roost or geese coming in to feed – I remind myself that I’m witnessing a scene that King Alfred might have known, or even Paleolithic hunters walking along this shoreline.

Saltmarsh is part of our deepest past in Britain, but we now recognise that it has to be a key part of our future.”

Britain, but we now recognise that of

The wild landscapes and unique habitat of saltmarsh are home to myriad species and rare plants.

Its joyous, flowing song seems almost an analogue of the wide-open horizons in our coastal landscapes. Skylarks might have declined in farmed arable areas but saltmarsh remains an important stronghold for the species.

This beautiful insect has a yellow-striped and fuzzy ginger-haired body. The adults emerge in August to coincide with the flowering of their main foodplant, sea aster, a pink-bloomed specialist of saltmarsh. emerge in of

nutrient-rich waters of saltmarsh creeks. These predatory fish eat crustaceans, small fish and squid. They migrate inshore in the summer and offshore during the winter.

These glorious stripy-backed amphibians were once found across much of Britain. They are now largely confined to coastal spots, such as WWT Caerlaverock, where the saltmarsh retains the shallow seasonal splashes and pools essential to breeding natterjacks.

One of the earliest waders to start breeding, come March the lapwings’ cartwheeling song-anddance display brings colour and drama to the saltmarsh scene. Their preferred habitat is saltmarsh, wet grassland and upland moors.

This strap-leaved, grey-green plant is often lost in the wider low-growing coastal vegetation. Yet come high summer, it suddenly bursts into flower, often turning saltmarshes into stunning panoramas of purple-blue.

As WWT Martin Mere celebrates its first breeding bitterns, find

out what it takes to create the perfect habitat for this rare bird

Words by Dominic Couzens

“WE NEVER EXPECTED TO BE successful so soon,” says Louise Greenwood, Reserve Manager at Martin Mere. “We wanted to create the right conditions for bitterns to breed here, but we thought it would take them time to come. The birds were ahead of us.”

Over the past few years, male bitterns had been heard booming in the reedbeds at WWT Martin Mere, but there were no signs of breeding. So, in 2023, Louise called in some experts to help improve the habitat. “On their advice, we removed any scrub that was encroaching into the reedbeds as this dries out the habitat. We also began maintaining reedbed areas at di erent ages, heights and densities to create the perfect nesting site for the birds,” says Louise.

The results were immediate. Last year there were two bittern nests at Martin Mere, the first ever recorded at the reserve.

“A male and two females settled in almost immediately,” says Louise. Bitterns are o en polygamous, so it’s normal for a male to mate with two or more females.

The most famous characteristic of male bitterns is their strange, far-carrying call. The ‘booming’ resembles the sound made by blowing over the top of a bottle and is made by the bird expelling air through its oesophagus.

Bitterns feed mostly on fish, together with the odd amphibian or small mammal. They often stand by the waterside, or walk slowly next to a channel or pool, before making a grab with the bill.

From the two nests hatched an impressive seven chicks. Of these, at least two young are known to have survived to fledging. It’s an extraordinary and unexpected success story.

The news is particularly welcome because the bittern is an extremely rare bird in Britain, on the Amber List of Conservation Concern. Indeed, at the beginning of the 20th century, following extensive marshland drainage, it e ectively became extinct here. And as recently as 1997 there was a depressingly low population of only 11 booming males. It has recovered, but even in 2022 there were only 228 males. The WWT Martin Mere birds represent a new colonisation.

The bittern is one of Britain’s most specialised species. It occurs only in larger stands of reeds.

The bittern’s camouflage is uncanny. The bird stands still among the reeds, often with its head pointing upwards like a stalk, relying on its pattern of brown streaks and speckles to remain concealed.

The bittern’s splayed toes and long legs are ideal for standing by water, walking in shallow water and keeping its balance in the debris and stems of reedbeds. It climbs well, holding on to several reed stems at once.

Loud calls enable bitterns to meet and mate (they then move on and live separate lives). The most exciting encounters are between males, who sometimes fly in chasing spirals, stabbing at each other.

Bitterns are confined to large reedbeds, but conditions need to be just right for them to breed and thrive. That’s where WWT comes in with its land management skills.

“It’s vital that a reedbed has areas of open water that are the right depth for fish to thrive, and to provide food for the young,” says Louise. “That’s about 30cm.”

Bitterns do best when there’s a tapestry of reed growth of different ages – some taller, some shorter, some denser and so on. Martin Mere cuts its reedbeds in rotation.

Louise’s top tips for spotting these masters of disguise at WWT Martin Mere, WWT Slimbridge and WWT London

Our small population is augmented in winter by the arrival of birds from the continent, which hop across the North Sea or English Channel to escape excessive frost and snow. If water is frozen for too long, the birds can’t reach their favourite food – fish – and are forced to leave in search of a gentler climate and wintering grounds such as WWT London’s wetlands.

“In Britain, the habitat suitable for bitterns is tiny, and wetlands are sensitive to pollution and development,” says Louise. “So, every breeding attempt is precious, especially in a new area. It’s a fantastic bonus for us, and only possible thanks to the support of our members.”

Patience is key. Watch the edge of a reedbed (try the Ron Barker Hide at Martin Mere) or a ditch and then sit and wait!

Visit in winter when numbers are boosted by birds from the continent.

1 2 3 4

Bitterns move about in reedbeds. You’ve a good chance of seeing them flying very low, from one patch to another.

Remember to keep an eye on your local centre’s Latest Sightings page on the WWT website.

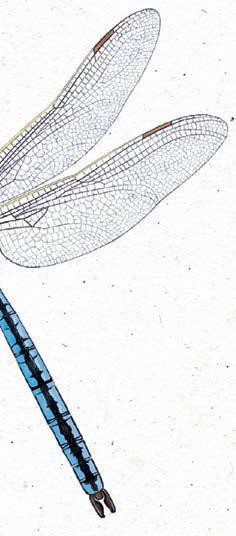

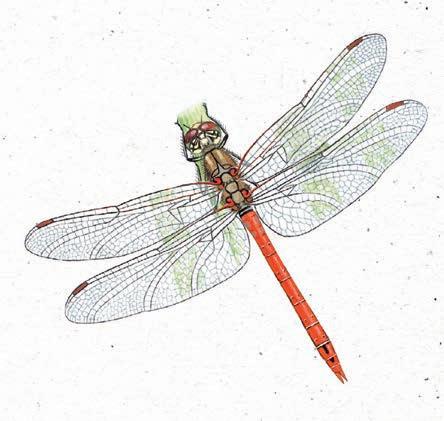

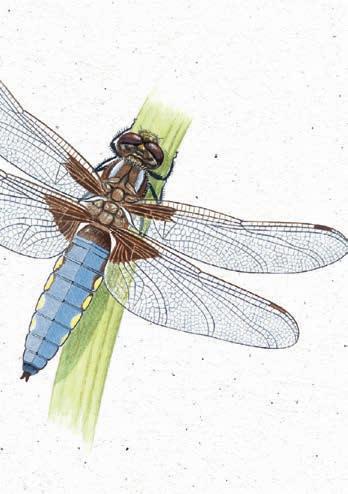

In spring and summer, our wetlands are a whirl of dragonfly activity. Spot chasers, hawkers, darters and more with our handy guide

Words by Derek Niemann

An impressively large and colourful dragonfly of ponds, lakes, canals and flooded gravel pits. It flies between June and August and even eats its prey on the wing.

HAIRY DRAGONFLY

With its distinctive hairy thorax, this small hawker is one of the first of the year to emerge. Look for it around lowland ponds, lakes and ditches from April to July.

The darkest hawker, the male’s abdomen is almost black with blue spots. Common across upland moors and sometimes acid heaths, it is on the wing from July to

and late October.

Brachytron pratense all BROAD-BODIED

A common dragonfly with a flattened body that gives it a fat,

broad look. Seen in summer, from May to August, around ponds and lakes, and even in gardens.

Emerging in May, this narrow-bodied dragonfly is on the wing between July and September – sometimes to November. It breeds in all kinds of water bodies, where it darts to catch insects.

Libellula fulva

This common dragonfly of ponds, lakes and canals near woodland is on the wing from late June to October. A fast-flying species, it is o en seen patrolling the water.

The male has a powder-blue abdomen

and the female’s is orange turning brown. A rare species found in only a few places in the south, it prefers slowflowing rivers and marshes. See it in June.

Easily recognised by the two dark spots on the leading edge of each wing (hence the name), it is active from May to September and sometimes October.

golden-brown wings. It has significantly increased its range across Britain in recent years. It hunts well away from water. and

out for our

Looks similar to the common hawker but has a yellow ‘golf-tee’ shape at the base of the abdomen. See it from July to November with numbers boosted by summer migrants.

MIGRANT HAWKER

These illustrations by Denys Ovenden are from the Collins Pocket Guide to Freshwater Life: Britain and Northern Europe published by Collins (RRP £25). Available to buy online and in WWT wetland centre shops.

With your support, we’re working with conservation partners to restore the cry that heralds summer to WWT Welney and beyond

Words by Paul Bloomfield

You might say that the mating call of the male corncrake is an acquired taste. That strident ‘crex crex’ cry – which also lent the species its scientific name – is most akin to the harsh buzz of a cheap digital alarm clock. Indeed, a century ago, many rural folk complained that it kept them awake. Today, such grumbles are a thing of the past. These once-common birds have been almost entirely lost from the British countryside.

Due to the proliferation of mechanised farming, this secretive, rarely seen rail was on the brink of extinction by the 1960s. Between roughly 1970 and about 2010, its UK breeding range contracted by nearly 75%. Even in its last British strongholds in coastal regions and islands of north-west Scotland, numbers plummeted between 2014 and 2021 by over 30%, to just 850 calling birds.

For a chance to hear that distinctive call in England this spring, head to WWT Welney in north-west Norfolk, the heart of a Natural England-funded captive breeding and reintroduction project in partnership, historically, with Pensthorpe Conservation Trust.

Chrissie Kelley, Corncrake Project Manager, explains: “We’ve been managing the captive corncrakes to breed and raise their chicks for two weeks, before they’re released into the

“ Grassland is the habitat corncrakes belong in, but they’re quite picky.

wild. We aim to release 100 youngsters each year, a goal we’ve so far mostly achieved. By the autumn, the young birds have become adults, ready to migrate to Africa for the winter, mostly in the Congo region, though some fly further south. They won’t be seen again until they return the following spring.”

Since 2021, these young corncrakes have been released at WWT Welney, where the habitat helps them thrive. “It was hard work transporting and installing the pre-release enclosures and feeding the chicks while they acclimatised and grew,” says Chrissie. “But the sta and volunteers at Welney were fantastic. It was a real collaborative e ort.”

The breeding project’s home is now on the Norfolk coast at Deepdale Conservation Trust.

The corncrake was once widespread across Britain, arriving from Africa each spring,

“We want to bring them back as a breeding species,” observes Emilie Fox-Teece, Conservation Breeding and Monitoring O cer at WWT Welney. “Grassland with tall plant cover is a habitat they belong in, but they’re quite picky – they don’t like it too dry or too wet. This is quite a hard balance to achieve on a floodplain, but they seem to like it here. We cut most of the washes for hay and graze cattle here, which ensures there’s vegetation of varying heights. This is ideal for corncrakes, which like tall plants for cover from raptors and short grass for feeding.”

Once released, the birds spread out across the reserve and ultimately beyond. This is why their future depends on improving habitat and land-management practices more widely.

“The call of a male corncrake is the sound of a healthy, wet grassland,” says Nigel Jarrett, WWT’s Conservation Breeding Manager.

“If you’ve got corncrakes singing on your land, you know you’ve also got myriad other species.”

But how can habitat outside reserves be better managed for breeding corncrakes?

“Many meadows are cut from the outer edge inwards, so birds are pushed into the centre of the field, ultimately ending up in bales or chopped up,” explains Nigel. “But grassland can be managed sympathetically by harvesting a bit later in the season, and by cutting from the middle of the field to the outside, so that corncrakes can run or fly away.

“Another factor a ecting corncrakes has been the drainage of wetlands,” he adds. “So WWT is working to create and restore 100,000 hectares of wetland in the UK by 2050, with the help of all our partners.”

Habitat is not the only factor impacting the UK’s breeding population of corncrakes.

“The birds’ migration to and from Africa is challenging,” notes Emilie. “Research shows that, at most, 30% of adults return – though

“ At least nine calling males were recorded at WWT Welney in 2024.

we don’t understand exactly why it’s so few. And typically, corncrakes live for only one breeding season in the wild, so they really need to raise two clutches successfully each to keep the population stable.”

There is positive news, though. At least nine calling males were recorded at Welney in 2024, up from just three in 2021. Of these, one of the birds was un-ringed, suggesting very few young birds raised by the wild breeding birds at WWT Welney migrate to and from Africa each year. There’s still much to be done to achieve the project’s long-term goal: to create a selfsustaining population in the Ouse Washes and, ideally, further afield.

The collaborative process of hatching, rearing and releasing corncrakes involves four key steps…

1

Breeding and hatching

Captive birds of Scottish provenance breed and lay eggs in safe enclosures. After they hatch, chicks are carefully monitored to ensure the female is feeding them and they’re growing well.

are related to moorhens, coots and water rails but, uniquely in the group, they live on dry land.

“This is really the first attempt to re-establish a ground-nesting migratory rail species,” explains Chrissie. “We’ve built up a wealth of knowledge over the years, and the project has many successes, but we’re yet to establish a viable, self-sustaining population. So, there’s more work to do and more to learn.”

“Corncrakes are part of our heritage in this country,” says Emilie. “The sound of a male calling brings back happy childhood memories for a lot of people. This project has been a perfect example of how using conservation breeding for reintroduction and habitat management together can restore lost wonders to our wetlands.”

Health checks and transfer

At 14 or 15 days old, each chick is caught, weighed, healthchecked by a vet and given a plastic identification ring. Youngsters are then transported to an acclimatisation pen at WWT Welney, where they continue to grow.

Ring and release

After about three weeks at WWT Welney, at between 35 and 40 days old, the juvenile is removed from its pen, health-checked again and, under licence, the first plastic ring is replaced with a British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) metal ring. The bird is then released onto the reserve and disperses into the wild.

Migration time

Having grown further in this food-rich habitat, in September or October the young corncrake migrates south to Africa, mostly to the Congo region. Birds that survive that journey will return to Welney the following year – hopefully to find a mate and breed.

One of the world’s most important wetlands, the Cambodian Mekong Delta supports a treasure trove of wildlife and is incredibly productive. But the delta is drying out fast – so WWT is working hard to bring these vital wetlands back to life

Words by Derek Niemann

IN A FEW WEEKS, SARUS cranes will begin to head back to their breeding grounds in the northern and eastern plains of Cambodia, having spent the past few months at two WWT sites in the wetlands of the Cambodian Mekong Delta – and WWT project coordinator Bunthary Srun will be there to see them leave. She supports WWT’s work to protect and restore these two key sites – Boeung Prek Lapouv and Anlung Pring. “I’m lucky to work in a place of such beauty. This intricate maze of rivers, swamps, islands and shimmering emerald rice paddies is full of wonder and wildlife,” says Bunthary. Cambodia is one of the most wetland-dependent countries in the world, supporting some of the rarest and most endangered species. The wetlands are also home to millions of people, providing livelihoods and dietary staples of fish and rice. But climate change and irrigation for agriculture threatens the delta.

Changing monsoon patterns mean sites are drier for longer, and rising sea levels are increasing salinity and soil erosion. And as large areas of wetland are destroyed to support a fast-growing economy, a third of the population no longer has access to clean water.

Our project is helping growers in the delta to produce climate-resilient crops – and is also working to make sure water is held where it’s beneficial. We’re encouraging farmers to switch to red jasmine rice. This uses less water and, thanks to investment in a rice-drying machine, we’re helping make the rice more profitable for

“ Our project is helping growers to produce climate-resilient crops.

3,750

metres of dyke built to retain water in 97 hectares of grassland.

rangers trained in SMART patrol system, allowing them to track patrols. 5

27,758

tree seedlings planted in the fledgling flooded forest in July 2024.

150

rice farmers persuaded to use organic fertiliser and less pesticide.

16

hectares of ephemeral pools created to help regrowth of the water chestnut.

farmers. Growing nitrogen-fixing black-eyed peas on the land once the rice is harvested reduces the need for chemical fertilisers and boosts income.

We’re supporting farmers to reach new markets with their red jasmine rice to improve their income security – they’re already reporting greater profits and a huge reduction in the use of chemicals. That, and a shi away from using pesticides, will have a positive impact on water quality.

Irrigation has dried out the land –fish pools and nurseries that were once year-round are now empty by the end of the dry season. We’ve dug new water-retaining dykes and blocked up ditches to prevent localised droughts. The grassland will benefit from the creation of ephemeral pools.

We’re planting tree seedlings to establish a flooded forest. Forests play a vital role in floodplain systems, providing a nursery and spawning habitat for fish.

7

Bunthary says: “The forest benefits local communities in so many ways. It helps store water for agriculture and drinking, and provides natural resources such as fish, firewood and plants.”

rangers part-funded to work on law enforcement, a sarus crane survey, environmental education, and a hydrological survey at Anlung Pring and Boeung Prek Lapouv Protected Landscapes.

A team of rangers protects the wetlands by preventing illegal fish traps and bomb fishing, monitoring water quality and ensuring farming and fishing communities are engaged. In the Khmer culture of Cambodia, sarus cranes are symbols of fidelity. Bunthary and her team are showing their loyalty to the cranes, yellowbreasted buntings, spot-billed pelicans and other species by reviving these precious wetlands and creating better lives for people and wildlife.

We want people to love wetlands as much as we do and to see their enriching beauty with fresh eyes. That’s why we’re delighted to work with award-winning young wildlife photographer Jamie Smart to show you how our reserves are great for nature lovers of all ages. Take it away, Jamie…

Eleven-year-old Jamie Smart is passionate about nature. From as early as she can remember, she’s been fascinated by creatures of all kinds. Regular visits to WWT Llanelli’s wetlands with her parents Eleri and James have deepened her sense of connection to nature – and provided plenty of opportunities to hone her skills as a wildlife photographer.

“WWT Llanelli is special because there’s so much to see and do,” says Jamie. “You’ve got the duck ponds that are full of all sorts of ducks (I love the colourful mandarins), the hides where you can watch all the wild wetland species, and there’s loads to see and photograph in between. I just love coming here because it’s a very fun place and it’s di erent every time. I like spotting species I’ve never seen here before, such as little grebes –if you love nature, it’s very exciting.”

Whatever the season, come rain or shine, Jamie loves to wander Llanelli’s

trails, looking for wildlife and exploring.

“Even if it’s raining, it’s a great place to come. The hides are always nice and dry, and you get to see and appreciate di erent things, such as the rain bouncing o the lakes or the water droplets on a duck’s back.

“Nature matters to me because it makes me so happy. With my photos, I like to show people animals they might not be able to go out and see. I really like doing macro photography of bugs, and I love photographing reptiles. When I share my photos, I hope people will be inspired to love and protect nature because it’s very precious. The world is a delicate balance. We need to look a er it and all the animals in it.

“Nature is amazing in every single way – sometimes all you need to do is put down your phone, camera or binoculars and just look out and enjoy it.”

For a Jamie’s-eye-view of WWT Llanelli’s wetlands and wildlife, read on…

I really enjoy pond dipping to see what mini-beasts I can catch. The dipping ponds at Llanelli are home to loads of aquatic insects that you can’t see in ponds that are overgrown with grass and weeds. I like looking at stickleback fish and the water spiders that can go underwater. I also always look for tiny damselfly nymphs, little pea clams and giant pond snails like the ramshorn – it’s very cool.

Kingfishers are really tricky to photograph in the countryside because they’re so hard to see. The kingfisher bank at WWT Llanelli is a great place to spot them – especially in summer when you know they’ll be nesting here.

Identify their favourite perch as they go back and forth from their nest when breeding in summer. Predicting where they are likely to land will help you get the shot. Wait and be patient but be ready to shoot when the kingfisher comes.

Be as still as possible The kingfisher will be gone at the slightest movement.

Bring up the shutter speed on a bright day if you want to get the bird in flight. To get a crisper shot you’ll need a shutter speed of 2,000 to 2,500, and an f-stop of around 6.7.

Go for a low shutter speed of 800 to 400 on a dull day for a shot of a kingfisher on a perch – the lowest your lens can go on the f-stop. Practice panning (tracking at the same speed as the bird) on a slower species, such as a swan landing on water, then build up to a kingfisher. To get a shot of a kingfisher in flight on a dull day, pan with a shutter speed of at least 160 and a similarly low f-stop.

There are lots of homes for mini-beasts at all WWT sites. In summer, the bug hotel is amazing with lots of bees and other insects flying around. It’s interesting to see the different nest sites for insects and how different species can all live in one habitat.

The dragonflies are really good here. I love taking photos of them. They’re the hardest creatures to photograph in flight – they’re so fast! I just about managed to pull off one frame for my winning entry in the 2023 WWT Waterlife Photography competition, but it was very tricky.

Know your dragonflies?

See page 22 for our guide to the species.

I love the amazing nature play areas at WWT sites. Water Vole City has different tunnels you can go in and out of. It’s fun to see what life in a burrow is like for animals.

There’s a very good variety of hides here for photographers, people with binoculars and birders. I love the Peter Scott Hide because you can see loads of different birds from there: herons, mallards, coots. It’s a good place for young people to learn about different species because there are so many different waterbirds in one place. I also like the Heron Wing Hide. It’s all glass so children, birders, people with wheelchairs… everyone can have access and look out at the beautiful view.

The duck ponds are always fun because you can get up close and personal with the birds without spooking them. You can interact with nature and connect with it. It’s a good place for taking photos, too. For a start, you know the wigeons, mandarins and wood ducks are actually going to be there.

WWT Director Anita Eade is determined to make wetland spaces more accessible so that everyone can enjoy the benefits

I WAS A TEACHER AND youth worker first. I worked with kids in Brighton who’d never been to the beach nor seen the South Downs. That a ected me. Once you’ve seen inequity in access, you can’t unsee it. It’s what drives me.

Access and inclusion is about giving all people the chance to benefit from things that society holds in trust. I’ve currently got a disability,

welcoming and helpful. But we need to broaden our reach. To do that, we’re looking at removing barriers to becoming members and increasing partnerships with community and disability groups. We are proud of our tickets for people on Universal Credit at London and Martin Mere, and the success of Generation Wild in targeting schools and giving young people and diverse demographics access to wetlands. Our initiatives will bring wetlands to more people – in the UK and overseas, virtually and in real life.

Change is about talking to people. We are keen to hear from members and to encourage more people to become trustees and ambassadors. We’ll also listen to those who are not currently WWT members or supporters of our work – how can we bring wetlands to more people? Nature is broken. Do we need some di erent viewpoints to fix it?

I’ve got a deep connection to WWT Arundel. We’d o en go there as a family and my four children felt so safe and happy there. One of my sons has high stress and Tourette’s tics. Being quiet and close to nature is a big deal for people who are neurodivergent or who su er from anxiety. For me, just walking the boardwalks in the reeds always feels magical.

I identi as queer, I’m from a working-class background and I’m a woman. I’ve felt excluded from or threatened in public spaces so it matters to me personally and it’s vital to what we do as a charity. Access to our sites, our knowledge and our jobs is key to our strategy.

AT WWT, we’re really good at getting people closer to nature in terms of physical access. Sta are so

I love spending time with my animals. We have a smallholding and I could sit and watch the chickens, ducks and turkeys forever. But my happy place is Brighton. It’s where I’m from. I’ve always been a swimmer and a canoeist. Being in or by water always li s my mood.

I am planning my first stand-up show, Diary of an Overly Ambitious Woman, a light-hearted take on the challenges of aiming for access for all. It can be di cult to open up a charity, but the benefits for WWT, for wetlands and for nature are too important not to try.

Our Waterlifephotography competition never ceases to amaze us. Your talent, patience and eye for detail bring our glorious wetlands to life in ways that surprise and delight us. Thank you to everyone who took part and for celebrating the nature we all love

Photo by Robert Singleton at WWT Martin Mere.

Robert says: “Last November, I spent some time photographing the godwits and ru from the Discovery Hide. The birds were quite territorial. Though they tolerated other species, if one of their own approached, a fight o en erupted. Some of their clashes were quite violent, though thankfully no lasting injuries were incurred.”

The judges say: “Robert proves there’s something to see at a WWT wetland at any time of year by capturing the moment these warring waders hit a perfect pose. Bright-orange feet outstretched like rapiers, wings flung back with beautiful feather detail, this image has energy, drama and grace. The shimmering winter-grey water backdrop is the perfect foil for the duellers. The judges unanimously named it the winner.”

Our centres are ideal for practising your photography. For top tips visit wwt.org.uk/ wildlife-photography a pair of Swarovski Optik binoculars.

This year’s entries showcased exceptional technical skills, creativity and passion – and have revealed rare and surprising moments, shy wildlife and extraordinary behaviour of the wetland species we cherish. Congratulations to all our finalists, featured here in Waterlife and online at wwt.org.uk/waterlifephoto. Particular mention goes to our adult winner, Robert Singleton, who wins a pair of Viking Optical Osprey 8x42 binoculars And the winner of our youth category (under 16), Katrina Vidaseva, receives a pair of Swarovski Optik binoculars.Our special thanks to Viking Optical and Swarovski Optik for supporting our competition and, again, to our members for sharing their stunning photography with the Waterlife community.

Photo by Jonathan Lewis at WWT Llanelli. Jonathan says: “I found this angle shades moth around the path to the ponds at Llanelli. I used a camera with a macro lens, flash and di user. To get the whole moth in sharp focus, I adopted a technique called focus stacking. I took 30–50 frames that were then combined in Photoshop to give this amazing depth of field.”

The judges say: “This otherworldly image blew us away. A species that hides in plain view by looking like a leaf is revealed in all its mysterious and wonderful beauty due to Jonathan’s mastery of macro-photography and stacking. The arresting eyes, exquisite texture, flamboyantly shaped legs and delicately scalloped thorax are rendered visible –something we’d never otherwise have seen. Bravo!”

by Katrina

Katrina says: “Bu ehead are so striking with their black-and-white plumage and iridescent head feathers. I sat down at the water’s edge in the hope of capturing one of these unusual ducks at eye level. The water was perfectly still, allowing me to capture this reflection.”

The judges say: “Katrina has created a painterly portrait of this small and energetic sea duck. The simple but dramatic composition focuses the eye on the bird’s remarkable rainbow head feathers, crowned by water droplets from a recent dive. Creative post-processing has maximised the monochrome e ect, turning a dull day into a stunning still life. Well done.”

Photo by Eden Tanner at WWT Slimbridge. Eden says: “One bright March morning, I was in the Rushy Pen Hide with my camera focused on a spot over the water, waiting for birds to fly past. Suddenly, this redshank came into view, gliding low over the lake. I instinctively fired o a few frames before it landed. Luckily the autofocus managed to keep up!”

The judges say: “With excellent forward planning and lightning reactions, Eden has captured the magical moment this redshank comes in to land. In this gorgeous spacious composition, every detail of the bird’s plumage is illuminated, from the glowing-orange legs to the catchlight in its eye. The e ect is doubled by the mirror-like reflection. The trailing wing caressing the still water makes it a winner!”

The best of the rest

See more of our favourite shots from this year’s competition at wwt.org.uk/ waterlifephoto

Photo by Rachel Jones at WWT Slimbridge. Rachel says: “I spotted this oystercatcher on the roof of the Discovery Centre on a sunny day in April. It’s the only time I’ve seen a bird on the roof right above the door and I realised it o ered a great angle for a shot. The wader wasn’t bothered by people going in and out, even when they saw my camera and stopped to look up. This is my favourite encounter with an oystercatcher.”

The judges say: “Congratulations, Rachel, for spotting this brilliant photo opportunity. The low angle, looking up through the ribwort plantain flowers on the centre’s green roof, grabs the attention with its unusual and interesting perspective. And the oystercatcher’s bright-red eye, framed perfectly in the middle, is compelling – you just can’t look away.”

Whether it’s through membership, visiting, volunteering, creating mini-wetlands, campaigning, or simply reading this magazine, you’re one of thousands of members helping to make a difference. Here are a few more ideas…

If you do one thing for wetlands…

Check out our mini-wetland how-to guides: wwt.org.uk/ mini-wetlands

In an hour Your continued WWT membership makes a massive di erence to our ongoing work to protect our precious wetlands. Got a special occasion coming up? Why not make the most of your membership and put a date in your diary to visit one of our wetlands sites around the UK? Membership makes a great gi for friends and family, too, and helps connect more people with our wondrous wetlands. Visit wwt.org.uk/gi -membership

Whether you go large in your garden or get creative with a bucket on your balcony, all blue spaces make a big di erence. Choose one that suits you: Barrel pond – ideal for a balcony or patio, quick and easy (no digging). Drainpipe rain garden – if you’ve got an outside drainpipe, it’s easy to make a rain garden (no digging). Tiny pond – embed a container in a small patch of earth with planting and a platform for wildlife.

Bog garden – watch as wildlife thrives in a patch of untamed watery wonder. Wildlife pond – with a larger diggable area you can create a magnet for water-loving creatures of all kinds.

Les McCallum’s shot of the water vole reminded us that you don’t need expensive kit to catch the action, winning this issue’s £30 WWT gi card. Les recalls: “Seeing a water vole at WWT Arundel, I slowly bent my knees, carefully moved my tiny pocket camera to ground level in front of the vole and clicked the button. What a result!”

“

In a morning Your actions make a huge di erence. Why not volunteer at one of our reserves or get involved with one of our projects?

Though tiny, our pond has increased the wildlife in our garden. I’m going to turn more old and broken containers into tiny wetlands.

Fran, WWT member

Did you know?

Water voles can have up to five pups per litter and can breed five to eight times a year. Scan to learn more:

“I like being a part of something important, learning new skills, being mentally stimulated and connecting with like-minded people who share a common goal,” says WWT volunteer Sue. For more on volunteering, visit wwt.org.uk/volunteer

In a weekend We need more people to know about wetlands and why we need them. On your next visit, take a friend or loved one who’s never been. Spring is a joyous time for a first visit.

“I was inspired to join having visited before as a non-member. It’s very accessible for people with disabilities,” says WWT member Lynn.

Plan your next wetland away-day at wwt.org.uk/member-visit

Take Action for Wetlands and you could win a £30 WWT gift card to spend in our shops! We want to see the wondrous things you’ve been doing –from your mini-wetlands to nature snaps from a visit. For a chance to win, send your story to waterlife@ wwt.org.uk

Scan for more top tips on wetlandfriendly living.

Create a ‘mini-wetland’ (see le ) to support bird and insect life through the seasons.

Collect rainwater in water butts, barrels, old sinks or baths to water plants and top up ponds.

Plant wisely. Pick native, drought-resistant or mesic (moisture-loving) plants that can cope with our changing weather.

Recycle grey water from baths and washing-up bowls to water the garden or clean muddy boots or bikes. 5 6 7 1

Mulch plants with homemade compost or bark to retain moisture, improve drainage and to reduce competition for water. 2 3 4

Build a rain garden to soak up surplus run-o by diverting water from your downpipes into planters or a specially planted area.

Water plants at the roots in the early morning or evening, and water thoroughly to encourage deeper rooting.

Let the lawn go brown in hot weather – it will quickly recover when it rains again. 8 9 10 11

Plant with an ‘oya’ or ‘olla’. An ancient watering method using porous clay pots filled with water and planted at root level, it slowly waters nearby plants.

Use a watering can rather than a hosepipe, and banish the sprinkler, which can use 1,000L of water per hour.

Let grass grow longer to keep moisture in the soil.

“ My spring challenge to you is to notice and quietly celebrate the wonder of wet

Dr Amy-Jane Beer is a biologist, writer, editor, outdoor enthusiast and mum from North Yorkshire

Water is the only substance that routinely and naturally exists as solid, liquid and vapour close to the surface of the Earth. This, and its high capacity for absorbing heat energy, form the basis of global weather and climate. At a molecular level, the slightly positive charge of hydrogen ions and the negativity of oxygen give each little dihydrogen-oxide threesome a polarity, with profound implications for the way they interact.

THE ABUNDANCE OF WATER makes it familiar. And that familiarity can breed, if not contempt, then certainly complacency, disregard and indi erence. O en, it’s only when water becomes scarce that we remember our fundamental reliance on it. Water is life. By weight, humans are up to 75% water, and it accounts for almost 99% of molecules in your body. But why?

The fact is, this tiny, mundane molecule is not only super abundant, but also super strange. On our not-too-hot-and-nottoo-cold Goldilocks planet, its oddness means that, against crazy odds, there exist such wonders as eel migration and starling murmuration, sphagnums and sundews, lichens and limpets, mosses and mud, otters and ostracods, willows and wild swimmers.

In the liquid phase, water molecules ‘hold hands’. This creates the surface tension that dictates the shape of raindrops, allows pond skaters and ra spiders to walk on water, and makes possible the capillary action plants and animals use to draw water upwards or circulate it around their bodies. The mixed charge of water also means it can associate readily with other charged or polar molecules and thus dissolve more compounds than any other solvent, including a majority of biomolecules. Perhaps weirdest of all is the crystal-lattice structure of regular ice that means it’s less dense than liquid water – especially water at about 4°C. In conventional compounds the solid will sink in the liquid. Were this the case for water, rivers, lakes, pools and seas would freeze from the bottom up. The fact that ice floats, combined with the insulative properties associated with high heat capacity, means that large water bodies remain unfrozen below a surface layer of ice. Thus, they can sustain life. My challenge to you is to notice all of this. Not just when you bathe or drink it, or set out to visit wetlands, but also when you eat, excrete, flush; when you wash or cook; when you sweat, weep, wipe your nose; when water carries flavour to your tastebuds; smoulders in your exhalations on a cold day; freezes on spiders’ webs and window panes; when it gushes from a tap or spring, squelches underfoot, pools in puddles, ruts, or the curve of a leaf. Notice, and quietly celebrate the wonder of wet.

Listen to our podcast

our wetland

If you love nature like Amy-Jane, immerse yourself in Waterlands, our wetland nature podcast. Scan the QR code or visit: wwt.org.uk/waterlands

Hone in on the action with our high-quality optics range, suited to your interests and budget. Every purchase supports our vital wetland charity work.

Explore the collection: