XCITY

‘I WAS HELD AT GUNPOINT ON LIVE TV’ Gangs in Ecuador

‘I WAS HELD AT GUNPOINT ON LIVE TV’ Gangs in Ecuador

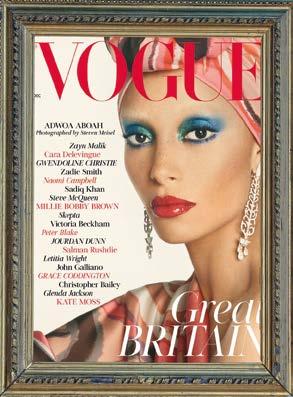

Vogue’s new editor talks

school zines, club scenes and the cover star of her dreams

+

Krishnan Guru-Murthy

Elizabeth Day

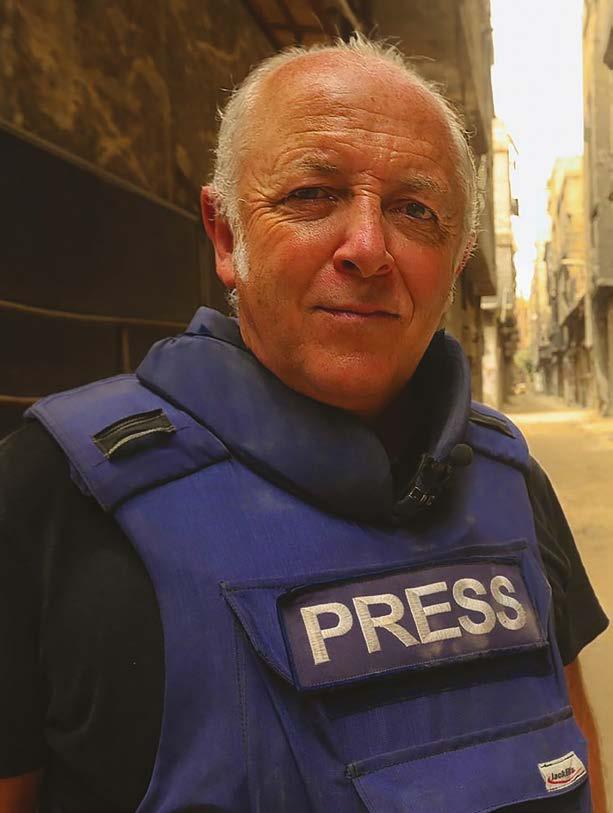

Jeremy Bowen

BYLINES TO BASSLINES

Journos

by day Rock gods by night

x.com / cit yalumni Join us on ww w city ac uk/ alumni-linkedin

For far too long, the journalism industry has been clouded in negativity, from a lack of trust to crippling financial pressures. But it’s not just the external. The job is tough. It’s about building trust while maintaining boundaries, painstakingly pursuing leads while working under demanding time pressures and finding the words to accurately and fairly tell people’s stories.

But in spite of the myriad adversities, truly incredible journalism persists –a reminder that it is still an integral profession, full of intelligent and tenacious people.

Chioma Nnadi, our cover star and the new British Vogue editor, agrees. She talks of the importance of cutting through online noise by choosing writers who have honed their craft and bring authority voices to stories (p.64). Nnadi has inherited a magazine with a legacy (p.59), but is poised to drive it forward, taking risks as she goes.

Risks can be essential in the pursuit of truth. Ros Urwin proved as much with her investigation into sexual abuse allegations against Russell Brand (p.21). Elsewhere, Rianna Croxford exposed the Mike Jeffries sex scandal (p.55) and journalists at B2Bs have had some of the biggest scoops in recent history (p.100).

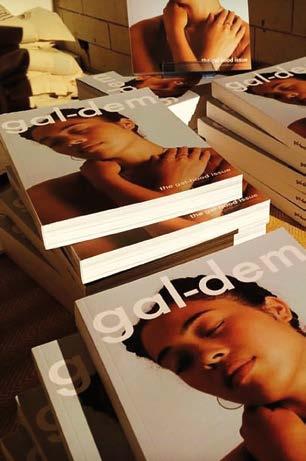

Others have taken risks within the media landscape, carving out space for more people to be represented in

CONTRIBUTORS

mainstream media. Queer press has big anniversaries this year (p.79). The sorely-missed gal-dem has left behind a powerful legacy (p.118), and female F1 reporters tell XCity about changing up the male-dominated motorsport broadcasting space (p.121).

The podcast industry has long had men at the top too which Elizabeth Day is seeking to change with the launch of her new production company (p.84).

Journalists have also endured relentless challenges to their work. Jeremy Bowen tells us how he’s used decades of experience to report on the conflict in Gaza (p.41). An Ecuadorian journalist held hostage on live TV shares his story with XCity (p.75) and Tibetan journalists talk about producing stories despite state surveillance (p.88).

These examples are all testament to why there is so much hope for the future of journalism. As are the cohort of talented writers behind this issue of XCity who understand the privilege of poring over words and taking risks to get to the heart of stories.

But for too many this year, that privilege ended too soon. In what has been a particularly deadly period for journalists across the world, we would like to pay tribute to all those who have lost their lives in the pursuit of truth.

Imogen Williams, Editor

Mariam Aziz, Camille Bavera, Ottilie Blackhall, Ceci Browning, Nasia Colebrooke, Faye Curran, Sydney Evans, Tommy Gilhooly, Maya Glantz, Millie Jackson, Ben Jureidini, Jaheim Karim, Nana Okosi, Marina Rabin, Hannah Rashbass, Hamza Shehryar, Yasmin Vince

With special thanks to Malvin Van Gelderen (www.idesigntraining.co.uk), our cartoonist, Ian Baker, and our printers, Tony and the team at Solopress (www.solopress. com)

EDITOR

Imogen Williams

DEPUTY EDITOR

Josh Osman

ART DIRECTOR

Maria Papakleanthous

DEPUTY ART DIRECTOR

Scarlett Coughlan

FEATURES EDITOR

Katie Baxter

DEPUTY FEATURES EDITORS

Caitlin Barr

Lizzy O’Riordan

Maria Sarabi

NEWS EDITOR

Luke Bradley

DEPUTY NEWS EDITOR

Dorjee Wangmo

LISTINGS EDITOR

Sarah Kennelly

DEPUTY LISTINGS EDITOR

Emily Moss

PRODUCTION EDITOR

Lotte Brundle

DEPUTY PRODUCTION EDITORS

Olivia Vaile

Francesca Ionescu

PICTURES EDITOR

Sophie Holloway

DEPUTY PICTURES EDITOR

Aniqa Lasker

CHIEF SUB-EDITOR

Niamh Kelly

DEPUTY SUB-EDITORS

Erin Dearlove

Nivedita Nayak

Devangi Sharma

MANAGING EDITOR

Emily Manock

ADVERTISING MANAGER

Alexandra Parren

SOCIAL MEDIA EDITOR

Urmi Pandit

DEPUTY SOCIAL MEDIA EDITORS

Mariam Amini

Sudrisha Goswami

Claudia Cox

PUBLISHERS

Jason Bennetto

Ben Falk

For any queries, please email Ben Falk at ben.falk@city.ac.uk @xcitymagazine

4-19 NEWS

21 Ros Urwin Q&A

22 Journalist musicians

23 Krishnan GuruMurthy

28 In memory of: myself

29 Journalists outside London

32 A night in the life

33 Tales from the typewriter 36 The maternal dilemma

39 Reporting from the Oscars

Jeremy Bowen

Election photography

50 Stories from behind bars

52 Kamal Ahmed Q&A

53 It’s all about TikTok

55 Rianna Croxford

59 Inside the archive of British Vogue

64 Chioma Nnadi 70 Impact of Zines

72 Writer’s block

75 Media and warfare in Ecuador

77 The presenter held at gunpoint

Evolution of queer magazines

82 Voices at the 2024 Olympics

Elizabeth Day

Reporting from Tibet

Behind the scenes of beauty journalism

Neurodiversity in the profession

Department goes dating

B2Bs breaking major stories

Drinking culture in the industry

The rise of WhatsApp

from

City, University of London and St George’s have agreed to merge, forming one of the largest higher education destinations for students in London. The medical school’s union with City is set to be a “health powerhouse” for students, researchers and the NHS, according to St George’s Vice-Chancellor Professor Jenny Higham.

The joint institution will be called City St George’s, University of London, and is scheduled to start operating from August 2024.

With the formation of the combined university, St George’s will bring the expertise of medicine, pharmacology, and biomedical science to City’s offerings of nursing, counselling, and psychology among others.

Professor Elisabeth Hill, Deputy President of City,

University of London said: “The more strength and power we have, the more multidisciplinary fertilisation there will be across the combined institution.”

The coming together of the two universities will broaden the opportunities for engagement between different disciplines. For example, journalism students may be able to undertake electives in Medical Journalism.

Professor Hill also assured that the cost of the merger will not impact the functioning of other schools in City. “The financial impacts or restrictions that City currently has, they are to do with City’s financial position irrespective of the merger,” said Professor Hill.

“We are obviously paying attention to our financial position. The recent financial decisions have not been driven by the merger

but by programs of work and activity that we already have underway and we will continue to deliver, with or without the merger.”

The work to merge City and St George’s had been underway since 2022 in a bid to enhance the scale and impact of the two establishments. The process involved performing due diligence on financials, health and safety, and contracts with the NHS and other stakeholders.

The union is expected to make City St George’s one of the very few institutions to offer such a wide variety of educational offerings in the health field as well as become one of the largest

suppliers of the health workforce in London.

Professor Sir Anthony Finkelstein, President of City, University of London, who will lead the combined institution said: “City St George’s will assume a role as one of the major London centres for higher education and research, distinctively different from the other member institutions of the University of London.

“We will be uniquely placed to play a key role in resolving one of the greatest societal issues of the day – training and developing the workers and leaders for the NHS and healthcare professions that are so desperately needed.”

It’s not just journalism students that have been running riot in the department building this academic year. In November 2023, students and staff were informed about a serious pest control problem: mice.

Professor Mel Bunce, Head of the Journalism department, in an email to students and staff said: “We are lucky to be based in a beautiful Victorian building. But unfortunately, this can make us attractive to mice, and they can eat through cables and damage

computers and equipment.”

Despite claiming that the problem was being addressed promptly, complaints were still persisting in January of this year, leading many to believe the mice infestation is far from over in City’s Journalism department.

“I saw three mice moving around,” an anony-mouse student posted on Unitu (the university’s new online complaints forum). “I hope the university could spend some more time on solving this issue because I was extremely scared and I

believe a lot of people have the same phobia as me.”

A representative from the Properties and Facilities department responded: “Like many large buildings with high volumes of occupancy and potential food sources, our campus does sometimes attract mice.”

They added: “We have designed our pest control measures to control the mouse population, although such is the issue, common to many organisations, that it is very difficult to entirely eradicate mice.”

Lotte Brundle

Professor Mel Bunce, Head of Journalism department

By Dorjee Wangmo and Luke Bradley

Professor Mel Bunce, Head of Journalism department

By Dorjee Wangmo and Luke Bradley

Students can soon study a journalism MA entirely online as part of a drive to recruit more international candidates, Journalism department Head Mel Bunce has revealed.

The department is also expanding its short courses programme, which will continue this summer.

The online journalism MA could launch as soon as September 2025, and will run for a full academic year.

Commenting on the push to attract more international students, Prof Bunce said: “We are hoping to reach people far beyond the UK. We have an amazing reputation as the country’s top journalism school, but we are not as well-known internationally and I think we should be.”

The online MA is also aimed at helping applicants

from lower economic backgrounds. Prof Bunce said: “We are conscious that journalism is overwhelmingly an elite profession. It’s hard to crack into if you don’t have money.”

“We want to do everything we can to make it more feasible. I think the fact you can do it part-time, and that it’s not in London, will make it radically more accessible.”

The summer courses will provisionally include podcasting, newsletter strategy and data journalism. The day-long courses are aimed at both the general public as well as working journalists who “want to continue developing their skills”. There will also be a discounted fee available to City alumni.

Prof Bunce said: “This is a chance for working journalists who might want to learn, for instance, the

basics of data journalism or podcasting or other skills that might have developed significantly with technology since they have studied.”

Prof Bunce said that the decision came from a desire to utilise available resources during the quieter summer months. “We have got amazing facilities, teachers and a lot of time. Especially in summer, we are not doing anything with them. We are even talking about doing true crime journalism or other things that might be interesting and keep people thinking and learning.”

She added: “Hopefully [the short courses] will be a taster for someone who might be interested in studying journalism but doesn’t want to make a big commitment like an MA. So, they can see what it’s like and maybe they will end up doing the full-time MA.”

Professor Mel Bunce will step down as Head of the Journalism department on 31 July, marking the end of her three-year contract at City.

Ms Bunce will then go on sabbatical for a year, in which she will take on a range of projects, including developing a centre for journalism and democracy in the department.

A new interim head, who will start on 1 August, will only lead the department for a year. A permanent head will then be appointed for a fiveyear contract.

Luke BradleyAmajor expansion of short courses at City has enabled more than 300 students from all nine MA journalism pathways to do a specialism module for the first time.

Certain pathways, such as the Magazine MA, can opt for two of the 13 modules on offer, which include Arts and Culture, Investigative Reporting, Crime, Sport, Humanitarian Reporting, Reporting the Middle East, and Lifestyle. This is due to the reduction of the Journalism Ethics module from 30 to 15 credits.

The department has also launched two new intensive courses which are Narrative and First Person Journalism, and Photography.

The department has

introduced three new visiting lecturers to support the expansion of specialisms.

Emma Youle is running an additional Investigative specialism module and has previously spearheaded investigative reports on issues such as the coronavirus pandemic and the recent contaminated blood scandal. She received the Paul Foot Award in 2017 for a report into homelessness in Hackney.

Lizzie Dearden is the new tutor heading the Security and Crime specialism, who was previously The Independent’s home affairs editor and is now freelance. Her book Plotters: The UK Terrorists Who Failed was published last year.

Faris Couri is the interim head of the Reporting the

Middle East specialism. He was previously the Arabic editor at BBC World Service and now works as a media consultant.

Last year, the Health and Science specialism did not run due to insufficient interest. This year, all 13 specialism modules have gone ahead. Sports, Humanitarian Reporting, Political Reporting and

Lifestyle were especially popular, with two separate classes running concurrently for each.

Jason Bennetto, the director of specialism modules at City, said: “It is hugely encouraging to see how many students want to do the specialism options. So far, all the feedback has been positive.

“We see the specialism modules as a USP for City because it is a great way for students to either build on existing skills or learn a whole new set of skills. Nowhere else offers this choice, and the new breadth of 13 options is excellent.”

A new specialism, called Reporting Underrepresented Communities and Identities, is currently being considered for next year.

The bestselling author behind the new Amazon Prime documentary Dead In the Water has criticised the media for its tendency to “glamorise” serial killers and make them “sound sexy”.

Following the recent documentary adaptation of her popular true crime book, City alumna Penny Farmer said it was shocking that murderers are portrayed on screen in ways which glorify them, and suggested that viewers should take more seriously the horrifying nature of these criminals’ most grievous offences.

Created by Raw TV, the production company behind smash hit Netflix documentary The Tinder Swindler, Ms Farmer’s new limited series unravels the story of her brother Chris and his girlfriend Peta Frampton, who were tortured and murdered on a boat trip in Guatemala during the summer of 1978.

A slew of similar crime series have hit streaming platforms in recent years, such as Monster: The

Jeffrey Dahmer Story and Conversations With A Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, many of which have received criticism for their sensationalised takes on terrifying criminals.

After a 2022 survey of true crime fans by OnePoll revealed that 44 per cent of respondents had a ‘favourite’ serial killer, Ms Farmer was keen that Dead in the Water refused to glorify her brother’s murderer. She said: “It’s weird how serial killers are glamorised. They’re made to sound sexy, and I think it’s terrible actually. But I suppose it’s inevitable, isn’t it? They [streaming platforms] want to attract big audiences.”

Failed by law enforcement both at home and across the Atlantic, Ms Farmer took the investigation of her brother’s tragic death into her own hands. In 2015, she found the killer’s Facebook profile, a discovery which would solve the decades-old case.

Asked whether she thinks the true crime genre can meet usual journalistic

standards of objectivity, especially when involved parties are so invested in the outcomes, Ms Farmer said: “I wanted answers. Obviously I was approaching it as the injured party because my brother died, but actually I worked really hard to see it from

both sides. I think I’ve been very impartial, very open, and non-judgmental.

“Law enforcement screwed up badly and I think I made that point. I presented it as a fact. I’ve tried to write as a journalist rather than the sister of a murder victim.”

The Guardian’s former editor-at-large, Gary Younge, has said newsrooms have “structural, representational issues including class, race, gender and religion” which need “strategic intervention”.

Mr Younge was addressing journalism staff and students in a talk at City on 27 February in honour of Rosemary Hollis, the late professor of Middle East Policy Studies.

According to Mr Younge: “A necessary strategic intervention has to be made to go from where we are to where we want to be.

“BBC TV newsrooms are so much more diverse than BBC Radio because you can’t see them,” he said. He discussed the importance of re-evaluating the culture in newsrooms, saying it is only possible through meaningful change in the hiring process.

Mr Younge added that

was totally surprised and

Dani Clarke was the winner of the prestigious Student Journalist of the Year prize at the PPA’s Next Generation Awards last October.

Each year, the award celebrates a student journalist who has “showcased exceptional work during their studies, and display[s] promise to be the talent of tomorrow.”

Ms Clarke, who is currently a sub-editor at Hearst, said: “I did not expect to win or even really believe I’d won. I was totally surprised but also completely delighted.”

She added: “It was a nice finishing touch on the year and made it seem even more

special. It has inspired me to become a multi-award winning journalist!”

Amongst the other Next Generation winners were fellow Magazine alumnae Kelly-Anne Taylor (Editor, Radio Times Podcast), Jess Hacker (Senior Reporter, Pulse and Healthcare Leader), and Isabella McRae (Reporter, The Big Issue).

The ceremony was held at the Mondrian Hotel in Shoreditch. Featured guest speakers included Nina Wright, CEO of Harmsworth Media, and Greg Williams, editor-in-chief at WIRED Caitlin Barr

even if representational issues in the media landscape were fixed, journalists would still need “courage” to write things that might prompt a backlash.

“If you write something, a group of people will come for you and very few people will back you up. The likelihood of you writing becomes less probable,” he said. “But nobody has to tell you what to write, you will know once you get in trouble. If I write

‘Let’s have an open and honest conversation about white people’ that could get me in trouble.”

On the flip side, he said that if all we have is courage then “you’ll be the soldier who goes over the top in the field and gets shot”.

“I wouldn’t be standing here, having spent 26 years in journalism, if I had run my mouth a lot. I made calculations about what I thought mattered.”

Ablind MA Podcasting student was enlisted by Chelsea Football Club to provide advice on reforming their disabled supporters association.

Tim Utzig’s involvement with Chelsea began as a fan, but his connection grew after starting at City in September last year.

Mr Utzig started the Podcasting MA course in September 2023 to pursue his interest in sports coverage. Through senior lecturer Brett Spencer, he got in touch with the director of Chelsea FC, Daniel Finkelstein, brother of City’s president Anthony Finkelstein. From there, he attended a match as part of his coursework, and produced a story on Chelsea’s win over Sheffield United.

The Chelsea Disabled Supporters Association (CDSA) later contacted him to hear his thoughts on the matchday experience for disabled supporters. Mr Utzig, who has Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON), was eager to get involved.

The CDSA is grappling with accessibility issues at the club’s stadium, Stamford Bridge, which was last renovated in 1998.

Mr Utzig said: “They are reforming this group to make supporting Chelsea as inclusive as possible, which is a great effort.”

One key issue that he has flagged is the accessibility of disabled toilets. “Stamford Bridge is an old stadium, and the disabled toilets are in inconvenient spots. Trying to get access to them is really difficult.”

Another issue he has raised is the protocol for

returning commentary radios to reception after the match. “Trying to walk through [the reception area] is such a bottleneck. It’s not very accessible. It’s not safe, there needs to another place to drop off the radio.”

He added: “The people who need the radio are blind or visually impaired. It’s things like that, things you don’t necessarily think of, that can really help.”

Chelsea FC have had prolonged plans to either redevelop Stamford Bridge or relocate the club entirely. When and if these plans materialise, the CDSA is working to ensure their voice is heard and is informed by the people they’re representing.

“You’ve got to think about everyone involved,” Mr Utzig said. “It takes having a disabled supporters group to get that perspective. Setting up groups without having people with disabilities in mind sets you back.

“Keeping those voices in while you’re setting things up, which is what they’re planning to do at the start of the new stadium, is always a key way to make things inclusive.”

As Chelsea’s tumultuous season continues, perhaps the club needs Mr Utzig’s help in more ways than one. “I don’t know what in the world has happened, but every time I’ve gone to Stamford Bridge, they’ve won,” he smiled.

Know your history to prevent future conflict, say economic experts

Journalists need to know history in order to prevent future wars, according to Ruben Andersson (International Journalism MA, 2005) and David Keen (Print Journalism PGDip, 1982), authors of Wreckonomics: Why It’s Time to End the War on Everything

The book explores why wars on migration, terror, drugs and crime continue to endure and expand even when it’s clear they are ineffective. Prof Keen explains that one of the biggest issues Wreckonomics raises is how journalists need to be extra cautious on not getting caught up in the “latest drama of a high-profile political response”.

Prof Keen said: “The temptation to forget ‘then’ and revel in the ‘now’ is enduring - and it is something politicians have frequently exploited in launching their spectacular fights against migration or wars on terror.”

The authors are university professors at the London School of Economics (LSE) and the University of Oxford, respectively. When the pair met at LSE, they understood that they shared views on war policies and set out to write Wreckonomics together. They wanted to start a discussion that can bring out positive change.

Prof Andersson says: “I think [journalism] both gave us the nose for unearthing a big political story and for asking critical questions.”

By

By

A£25,000 scholarship funded by Spotify will be available to one student studying the Podcasting MA at City.

The scholarship will cover the tuition fees and living expenses of one UK student with a place on the 2024/25 course. The application process will include a 600word essay outlining why they wish to pursue a career in podcasting.

Jon Mounsor, Podcast Content partner at Spotify, said: “The creative industries only stand to benefit from different perspectives, viewpoints, and backgrounds, so it’s a privilege to be able to support City on the creation of a scholarship like this.”

He added: “Huge credit to the team here for recognising the need for something like this, then doing the work to create it.”

Brett Spencer, director of the Centre of Podcasting Excellence at City, said: “We are trying to attract

somebody who has lots of ideas, passion, and excitement for podcasting, but would not have the funds to pursue a master’s at City. This could help set them on the road to a bright career.”

City launched the UK’s first dedicated MA in Podcasting last year.

According to the 2023 Q3 results from Radio Joint Audience Research Ltd (RAJAR), nearly one-third of the UK’s population aged 15 and above listen to podcasts on a monthly basis.

Mark Sandell, lecturer on the programme’s “Pitch to Product” module, said: “In 2023, we saw huge growth in daily news podcasts and in 2024 - a big election year around the globe - there’s been a proliferation of politics podcasts.”

Mr Spencer said that the podcasting industry is facing challenges with finding versatile producers who are adept in all aspects of the job, a problem the course aims to resolve.

“Making a podcast is more than audio production,” he said. “It requires expertise in media law, marketing, SEO, podcast discovery, understanding platforms and monetisation, writing host reads, and more.”

With the programme heading into its second year, the senior lecturer added that the first cohort heard from “some of the biggest names in podcasting every week”. Students also undertook work experience at numerous successful companies, including Goalhanger, Persephonica, and Message Heard.

Mr Spencer added: “We hope from that, they will be able to hire a range of wellrounded employees.”

Charlie Brown, a student on the Podcasting MA, praised the “holistic approach” taken to learning, as well as the “excellent contacts” that the tutors have in the industry. “It’s been an incredibly beneficial time so far.”

The Nick Lewis Memorial Trust increased its funding for the Nick Lewis Scholarship from £10,820 to £15,000 for the coming year. Some £14,500 from the scholarship will go to fully fund the home tuition fees of one MA International Journalism student and the remainder will be given to the student as a bursary.

Suzanne Franks, professor of journalism at City said: “This is to keep pace with the rise in fees and the rise in costs of living in London.”

St Bride’s Church also extended the £4000 Guild of St Bride’s bursary for the next academic year. “The church has always been very generous and willing to help youngsters entering the profession,” said Prof Franks.

Due to its location in Fleet Street, the birthplace of the publishing industry in the UK and heart of the British newspaper industry, the church has had a longstanding relationship with journalism. St Bride’s Church has continued to offer the bursary each year to one MA Digital and Social Journalism or MA Newspaper Journalism student at City University for the past 12 years.

Sudrisha Goswami

City journalism lecturer Lara Whyte gave birth to her baby boy Ezra on 16 January 2024. Weighing 8lbs 5oz, she said he is “healthy and happy.”

Particularly pleased with the new addition to their family is four-year-old Leah, who is embracing her new role as a big sister. “She is adjusting to no longer being a lonely child, but is loving having a baby brother,” said Ms Whyte.

Ms Whyte said she is missing City, but is enjoying spending time with her family. Whilst the department is yet to meet the six-week-old Ezra, Ms Whyte has shared photos of him wearing the bib gifted by her colleagues for them to gush over until they do.

Putting aside the Mum blogs this time, Ms Whyte said: “I’ve been able to read more than I did the first time round, although I am doing so at a snail’s pace”. She is enjoying reading the fiction stories in New Yorker magazine that have been sitting on her desk for years, adding they’re “good to read over several days, or weeks.”

Ms Whyte assures her maternity leave has been anything but leisurely, adding she is “enjoying the labour of mothering but it is like a job.” Though Ezra is making a night owl of her with his 4am feedings, the former ITV writer owes her nocturnal resilience to journalism: “My many night shifts at ITV prepared me!”

‘Like

Jane Martinson, the Professor of Financial Journalism at City, has revealed the challenges she faced researching her new book on Sirs David and Frederick Barclay, controversial owners of The Telegraph.

Jane Martinson, the Professor Financial Journalism at City, has revealed the stress and anxiety she suffered in having to fight legal threats for her new book on David and Frederick Barclay, the previous owners of The Telegraph.

You May Never See Us Again: The Barclay Dynasty: A Story of Survival, Secrecy and Succession was published in October.

You May Never See Us Again: The Barclay Dynasty: A Story of Survival, Secrecy and Succession was published in October after the notoriously litigious Barclay family took her required she go to court.

As part of her research for the book, she took part in a legal challenge in court after lawyers for Frederick Barclay’s nephews attempted to stop reporting of his divorce proceedings.

In 2022, Prof Martinson was investigating how Frederick Barclay had not paid his ex-wife any of her £100m divorce settlement. David Barclay’s sons, Aidan

and Howard, objected to the case being held in open court. The Barclays’ case named Prof Martinson as a journalist digging for private information on the family. The High Court opened with lawyers for Prof Martinson arguing for open justice in July 2022.

“It was astonishing and like nothing I’d ever experienced in many decades as a journalist,” Prof Martinson said.

She added: “It was all very stressful.”

The Guardian paid for two barristers to support Prof Martinson, supported by letters from the Financial Times, Bloomberg and PA, and the judge later denied the case for privacy. During the proceedings, Prof Martinson gained access to digital communications and

letters from family members and trustees which “helped enormously” with her research.

Prof Martinson had to piece together their story from documents in the National Archives, Guernsey Press articles, company accounts. She visited Sark, which neighbours Brecqhou, the private island they bought, to meet with people who knew them.

“I called everybody that had ever met or worked with them,” she said. “The value of digging into something that takes time can’t be emphasised enough. Stories that matter take time.”

The book was included in the Financial Times’ Best Books of 2023 list.

She hopes her book will encourage other journalists to delve into the stories on

media publications and the proprietors behind them.

“The media industry doesn’t like washing its dirty linen in public.” Prof Martinson said. “Journalists need to ask more questions and be aware that the influence that is wielded by owners is huge.”

Claudia Cox

Former Labour leader Neil Kinnock has warned journalism students that the Labour party cannot afford to be complacent, despite an 18-point lead.

Addressing the students on the Political Reporting specialism in February, Mr Kinnock said that, in the run up to the general election, “complacency in the Labour Party must not be allowed”.

He argued that, however politically divided the Conservatives may seem,

Question

the Labour party’s opinion poll lead does not guarantee them election success.

He said: “Fortunately, Mr Starmer has got ‘complacency is forbidden’ across the inside of his eyelids and he’s managed to secure that condition for quite a lot of his colleagues.”

However, he added: “These are human beings, and this is a political party. You can try to safeguard against complacency as much as you like, but when you have an 18-point lead,

there will be people who knock on the door once a week instead of the three times that is required.”

He said that MPs are liable to do and say rash things, citing the example of Labour’s withdrawn Rochdale by-election candidate Azhar Ali, who said that Israel knowingly allowed the 7 October attacks to go ahead.

Mr Kinnock said: “There was no justification for what he said in any circumstances, but he did

say it. And the party is now, instead of being on the front foot, dealing with the alienation of Muslim voters.”

He added that while the party seemed to be avoiding a repeat of their narrow election loss to the Conservatives in 1992, when Mr Kinnock was leading the opposition, they “could avoid it a bit more.”

“I still think they should make further disclosures about tax and spend in the months they’ve got left until 14 November.”

human-led reporting:

‘It will always be central to what we do’

Esme Wren, City alumna and editor of Channel 4 News, advised City students to attach value to human reporting as “AI is going to change the shape of journalism”.

James Ball, City alumnus and Pulitzer prize winner, hosted the Question Time panel on 4 March 2024. The guests included Esme Wren, editor for Channel 4 News, Rosie Wright, presenter of Times Radio’s Early Morning Breakfast, and Kamal Ahmed, co-founder and editor of The News Movement.

With the recent rise of AI in journalism, Ms Wren encouraged students to

remain consistent in the way they report news.

She said: “There are so many competing issues like AI which are going to change the shape of journalism. But you hope that people want that eyewitness reporting and there is some value attached to that.”

She added: “What you want to ensure is that the news you see is gathered by humans that have been physically there to witness it rather than creating that content artificially. It’s tough, but I still have hope for it.”

The other panellists were also optimistic about the future of journalism. Ms

Wright emphasised the need for trusted humans to tell stories. She added: “Human connection, and a person telling you what they know and how they found out about it, will always be central to what we do.”

AI being used in journalism has led to growing concerns about core values of accuracy and validity, as well as job security. In a recent report by JournalismAI, 73 per cent of news organisations surveyed believed generative AI such as ChatGPT presents new opportunities in this field.

While AI has its benefits such as removing human

error and helping to analyse data, there is also a dark side of machine-led help. The ethical implications of using AI such as algorithmic biases and surveillance are becoming more prevalent in the age of misinformation and fake news.

However, Ms Wren highlighted that this is being discussed by all organisations in hopes of protecting democracy. She said: “There are a lot of roundtables at ITN about the future of AI and fake news and how the government has to take it seriously. But the way we report news –that shouldn’t change.”

Mariam Aziz Ahmed

Aformer red carpet presenter and a BBC podcast editor are among the new members of staff joining City’s journalism department this academic year.

Brett Spencer is a senior lecturer on the new MA Podcasting course and director of the university’s Centre of Podcasting Excellence. His previous work includes being the digital content director at Bauer Media Group, and over 15 years at the BBC.

He said: “I created some very early podcasts that are still popular, and I’m really proud of that.” Mr Spencer helped develop the Kermode & Mayo’s Film Review podcast, which featured critics Mark Kermode and Simon Mayo and ran from 2001-2022.

Another highlight of Spencer’s career was 6 Music Live, a project which broadcasted live performances of

up and coming bands and musicians via The Guardian’s website. “When we started,” Mr Spencer said, “we were really scrapping around for people to play, because no one knew what it was. And then, in our last season, we had Paul McCartney.”

Joe Michalczuk has also joined City’s journalism department as the new programme director of MA Broadcast and MA Television. Previously the journalism programme leader at the University of Winchester – a teaching role is not new ground for Mr Michalczuk. However, he said: “There’s definitely an extra sense of trepidation stepping into City, because it’s just so renowned for its journalism training.”

From Robert De Niro to Daniel Radcliffe, Mr Michalczuk has interviewed the stars of Hollywood releases for vast audiences of The Saturday Show,

The Wright Stuff, and BBC Radio London, among others, as well as for freelance purposes. But the confidence needed to question celebrities has somewhat prepared him for teaching at City. “There was a sense of nerves but also excitement,” Mr Michalczuk said. “Being given the ability to run two prestigious courses is a great opportunity.”

Attending the Oscars and BAFTAs for Sky News as their entertainment reporter and film critic, Mr Michalczuk said his time interviewing the stars of the silver screen is a highlight of his career. “It showed how great it can be to be a journalist,” said Mr Michalczuk. “When you’re a journalist and get to be in the front row of something, it’s a great opportunity.”

Suyin Haynes is a visiting lecturer on the MA Magazine Journalism course who was the editorial head at gal-dem, and a senior

reporter on staff at Time magazine. gal-dem was an online and print media organisation dedicated to spotlight perspectives from people of colour and marginalised genders that was developed in 2015 and ran until 2023. The publication shut down in March 2023.

Ms Haynes’ work at Time magazine spanned from Hong Kong to London, firstly as an audience editor, before moving to a senior reporter role. She has also interviewed Greta Thunberg and Stormzy as a freelance journalist for various publications.

However, it is not these star-studded interviews that are Ms Haynes’ favourites. “As much as the big names or household names are fascinating or fun,” she said, “I find speaking to just ordinary people doing extraordinary things have been the most powerful interviews of my career.”

The media law exam featured an artificial intelligence (AI) question for the first time this academic year, after the department tested ChatGPT on past papers and discovered it did well enough to pass.

In the exam, postgraduate students were asked to assess the AI’s ability to critique a court report and to judge whether it was able to identify legal risks pertaining to reporting restrictions and contempt of court.

Module leader for postgraduate media law, Richard Danbury, said: “Last year we read reports that AI had passed the Solicitor’s

Qualifying Exam and a Harvard MBAs, so we put a couple of sample questions from our exam through AI. It didn’t do very well, but it did enough to pass.”

Although AI has been met with mixed feelings by the media industry, its use is becoming more widespread. Director of postgraduate journalism, Jonathan Hewett, said: “AI is not going to go away. It has great potential to both relieve journalists of tedious tasks and make some corners of journalism more accessible.”

Mr Danbury added: “We thought long and hard about what to do that was sensible. Other institutions

were going back to pen and paper exams. We realised that AI often gets it wrong, so we decided to build that into the exam by teaching people that what the AI is telling you could be rubbish.”

The hope is that AI will be used to enhance journalists’ ability to produce news reports, as opposed to replacing them. One example of this is Microsoft partnering with the Online News Association to provide training to journalists, promising to help them build the knowledge needed to adapt to the changing face of journalism.

Although learning how to understand and use

AI is a crucial tool in a modern world, feedback from students was mixed.

“Some found it interesting to start with, but it got quite repetitive,” said Mr Danbury. “Some of the seminar leaders dropped the weekly critique of AI. But it was necessary to do it, so that everyone knew what the process would be when the exam came around.”

When asked if the department will keep the AI question the same in future exams, Mr Danbury said: “It depends on the results of the exam. If a lot of people particularly struggled with that exam question, we’ll have to have a look at it.”

Muslim voices are being increasingly and disproportionately vilified in the UK media, the head of the Centre for Media Monitoring (CfMM) revealed at a City event.

During a panel discussion on navigating the British media as a Muslim journalist, Rizwana Hamid, director at CfMM, said that Muslim voices were facing heightened scrutiny and misrepresentation following Israel’s offensive into Gaza in October 2023.

The event, organised by MA Magazine Journalism student Mariam Amini, featured Mustakim Hasnath, News Editor at Sky News, Narzra Ahmed, freelance journalist, and Ms Hamid.

Broaching investigative research carried out by CfMM, Ms Hamid said: “We’ve analysed thousands of articles and broadcast clips. When it comes to online and print, 59 per cent of the stories are negative

about Muslims and Islam across the board... television is 49 per cent.”

She added: “The theme under which we are covered is predominantly terrorism and extremism.”

Amini organised the event to provide a platform for Muslim voices. “Only 0.4 per cent of journalists in the UK are Muslim, despite there being almost 4 million Muslims in the country,” Amini said. “It was this sole statistic that planted the

seed that led to this event.”

CfMM’s findings were disclosed in a 148-page report, published on 6 March. Among the publication’s findings were that the British media was 11 times more likely to refer to Israelis as ‘victims of attacks’ compared to Palestinian victims, and that TV reports cover Israeli perspectives three times more often.

The panellists also addressed a range of Muslim-centric concerns,

offering insight into personal struggles in the field, including prejudice, biases, and pressure to cover specific types of stories.

“There were times when I was brought into stories just because of my access in certain communities,” said Mr Hasnath.

He added: “I’m happy to do these stories as long as I’m not just used as a contact maker.”

Hamza Shehryar and Devangi Sharma

Sports journalist and former City lecturer Russell Hargreaves has passed away at the age of 45. A talkSPORT pundit for a wide variety of sports, Hargreaves was also a veteran member of the journalism department, having both studied and taught at City.

Known affectionately as “Russ”, Hargreaves read Classics at Cambridge University before graduating from City’s MA Broadcasting course in 2001.

After graduating, he went on to have a successful career in sports journalism that saw him cover a range of events, from the Ryder Cup to the Lions Tour.

Hargreaves was an avid fan of Harlequins rugby team, as well as National League football team, Kidderminster Harriers. He was also an Arsenal FC

supporter and provided regular commentary for their matches, which endeared him to many City alumni.

In 2021, Hargreaves returned to City as an undergraduate tutor and guest editor of the MA Broadcast programme. “When we needed another tutor on our undergraduate programme, he sprung to mind as an obvious choice,” said Sandy Warr, City’s senior lecturer who taught Hargreaves and worked with him at talkSPORT.

“Russ had a wonderful gift for helping people feel comfortable and confident, and develop their abilities. He was always very generous and spirited in helping other people discover their talent.

She added: “It was a wonderful full circle moment of him learning his craft here, going into the

industry and developing an extraordinary range of skills, becoming a good coach, and then coming in here and teaching as well.”

In talkSPORT’s online tribute, radio producer and presenter Scott Taylor said: “Not only was he the ultimate professional, who was well-researched and would tackle any show with the same amount of effort and commitment, leaving no stone unturned, he was the most genuine, kind, humble human being who would make time for everyone, and I mean everyone.”

Professor Mel Bunce, head of the journalism department at City, said: “His love for media, his passion for Arsenal and his habit of calling everyone ‘mate’ won him many friends.”

Hargreaves is survived by his wife, Rachel, and his three children.

The Foreign Press Association awarded Maya Saad ‘Student Foreign Correspondent of the Year’ at their Media Awards in November 2023.

Ms Saad, a graduate of City’s Investigative Journalism MA last year, won for her final project, a video on small boat migration in Lebanon. In her acceptance speech, she dedicated her award to Reuters’ video journalist, Issam Abdallah, who lost his life while reporting on the southern Lebanese border during the Israel-Palestine conflict.

“It was very exciting getting the award,” said Ms Saad. “I wasn’t expecting it. It was a long and challenging process making the video. It was my first experience filming alone, with my father helping me carry my equipment. It was very rewarding making the piece, speaking to people and getting to know them.”

The judges, who included City’s own senior journalism lecturer Glenda Cooper, said: “The story had excellent access to individuals and the families directly affected – which was dealt with great sensitivity. Maya is not from Lebanon but managed to get all the right interviewees to produce a well balanced and topical report which showed great humanity.”

Caitlin Barr Russell Hargreaves in the commentary box at Twickenham StadiumThieves are targeting City students and other patrons at the journalism department’s favourite watering hole - the Dame Alice Owen pub.

At least three journalism students and a journalism lecturer have had their laptops stolen from the pub on St John Street, opposite the university.

The pub has been the site of thefts in previous years, but this academic year has seen a rise in Journalism students being targeted.

In March, Professor Mel Bunce, Journalism Department Head, emailed students warning them to be “vigilant” in the pub.

Prof Bunce wrote: “One of our MA students had their laptop stolen from the Dame Alice Owen pub this week.”

She continued: “I know

lots of you are in and out of the Alice all the time –please be really vigilant with your belongings and tech equipment.”

MA Magazine students

Luke Bradley and Josh Osman had their laptops stolen on the evening of 16 November 2023, while at the Dame Alice with their coursemates.

The magazine cohort had chosen to pile into the Dame after finishing a big deadline. Despite plenty of coursemates remaining at the table, three men were able to swipe the laptops.

After picking up their bags to leave, Mr Bradley and Mr Osman realised they were suspiciously light.

While Mr Osman phoned the non-emergency police number, Mr Bradley used a tracking app on his phone

to set off after the thieves, tailing them all the way to Old Street before giving up and returning to the pub.

Mr Bradley said: “I had only just settled into London and I bought my MacBook right before I left. I shouldn’t have chased after them, my mates were worried about me until I made it back.”

Mr Bradley continued: “The staff were sympathetic, there’s not much they can do to prevent theft. The police were no use.”

Vinnie Baker, assistant manager of the Dame, said: “We got our cameras upgraded, and we’re putting up posters asking people to be vigilant of their belongings. We’ve also got a neighbourhood-watch-style group chat with the other pubs in the local area.”

Mr Osman said of the situation: “It came as such a shock. It’s a popular pub and we all go there so often that it really caught me off guard.”

We’re now offering the chance to opt out of receiving XCity magazine to save the environment

Scan the QR code below to make the change and receive only the digital copy of XCity next year

City alumni Kate Samuelson (MA Magazine Journalism 2014) and Tom Brada (MA Broadcast Journalism 2014) are due to be married on 1 April in a Jewish ceremony in Oxfordshire.

The couple met in an English tutorial at Bristol University on Shakespeare, bonded by an eccentric professor whose lectures on Titus Andronicus went over their heads. A year of friendship followed before the relationship developed.

The couple also did journalism courses at City in the same year, but their paths rarely crossed except

when revising Media Law. Mr Brada said: “My friend and I came out of the exam and thought we had done unbelievably well, we were cheering each other, just so cocky. Then we got the results. Kate had absolutely smashed it and we had almost failed!”

In a twist on tradition, Ms Samuelson proposed on Brighton Beach. She said: “We went to Brighton to see a Sugababes concert and I proposed the next day. I’d been planning it for a while, but he was shocked.”

The groom will wear a forest green suit and the bride will be in an ivory-

coloured dress from Brides do Good, an ethical and sustainable bridal brand that donates a third of profits to charity projects working to end child marriage. The dress is silk and will be paired with a veil.

“We’re getting married beneath a chuppah, which is a structure that symbolises the home.” said Ms Samuelson. “Traditionally, the seven blessings would be read in Hebrew, but we’ve asked seven people to do interpretations of those blessings. We’ll definitely do some dancing on chairs.”

Ms Samuelson’s mother and father are giving her

away, and the evening’s festivities will start with a surprise performance of ABBA’s Gimme, Gimme, Gimme by a tribute band.

Of the upcoming nuptials, Ms Samuelson said: “We’re a bit overwhelmed by how much admin there is, but definitely excited.”

Mr Brada is senior broadcast journalist at the BBC and Ms Samuelson is a senior journalist in newsletters at the BBC. She was previously editorin-chief at The Know and has a newsletter called ‘Cheapskate’, which makes London’s culture finanically accessible to all.

It’s third time lucky for long-form journalist Tom Lamont, whose debut novel Going Home will be published in June. The 41-year-old wrote the book within a year after failing to get two earlier drafts accepted. Set in the suburban north London Jewish community where he grew up, this successful attempt marks his first step into the world of fiction.

“I am delighted and super relieved because even though I gained a lot mentally and spiritually from writing it, you can’t help but add up the time you spent,” Mr Lamont said. “I wonder, if the third manuscript hadn’t found a home, whether I would have been able to sit down and carry on.”

Going Home tells the story of Téo Erskine, a road safety instructor who returns home to visit his ageing father, Vic. When a former classmate dies suddenly, he and his childhood pal Ben

find themselves responsible for taking care of her tricky two-year-old son.

Speaking on the transition from true stories of journalism to the imagined worlds of fiction, Mr Lamont said: “Embarrassingly, I’ve always done both. I just haven’t ever been published before. Fiction has been this thing I’ve done in secret.

“For the last 15 years, more or less, I’ve started every day by doing a bit of fiction in the morning. Then I turn myself to journalism, my public-facing job. I see it as quite a nice, enlivening, almost caffeinating beginning to each day.”

While celebrated by The Observer as one of the best emerging novelists of 2024, Mr Lamont already has a huge portfolio of pieces for national newspapers. Books scratch a different itch.

“The deeper satisfaction of writing is having a body of work and not just individual pieces,” he said. “I love

Above: Tom Lamont

Right: Going Home cover

having a good chunk of the road behind me, full of old, interesting jobs. And I want to try and replicate that with books. I want to fill a shelf if I can. If I have time. And if publishers keep wanting it.”

What comes next?

Mr Lamont has already set to work on a second book: “The day I finished the one that’s coming out, I started the next one.”

A new fellowship for aspiring journalists from workingclass backgrounds has been praised by City alumni as “a remarkable thing to do”.

Independent publication Polyester opened applications in February for a programme to support creatives from less privileged backgrounds. It was founded to commemorate Polyester’s managing editor, Eden Young, who passed away last year aged 29.

The feminist arts and culture magazine explained

that the recipient will get a “fully paid, full-time, yearlong position” at Polyester The fellowship will pay the London Living Wage and provide mentorship directly from the editors. This was described as the same training that Young undertook at the start of her career, without industry connections or experience.

Lilith Hudson, graduate of City’s MA Magazine Journalism course in 2022, said the fellowship is an opportunity she would have been grateful to have had

at the beginning of her career. “It’s such a nepotistic world in journalism, unless you know somebody who knows somebody, unless you have a way in,” said Ms Hudson, who attended a comprehensive school. “There needs to be more bursaries like this.”

Ione Gamble, editor-inchief at Polyester, said in a press release: “Eden had so many wonderful attributes, and chief among them was being a proud workingclass woman - a rarity in an industry wherein over 80

per cent of journalists come from professional and upper class backgrounds.”

Rhys Thomas, a 2019 MA Magazine graduate from a working-class background, said it is a touching and ambitious initiative to help improve class diversity.

“I would hope that it acts as a catalyst to help better the industry,” he said. “The effort levels that are involved for a small publication like Polyester to do this kind of embarrass many major media companies.”

Urmi Pandit By Caitlin Barr

By Caitlin Barr

Here’s your starter for ten. How many City journalism alumni featured in the Christmas University Challenge? For a bonus point, did they lose? The answer is three, and sadly, yes. But not by much.

The team, composed of journalists Zing Tsjeng, Joe Crowley, and Sebastian Payne, as well as lawyer and campaigner Martha Spurrier, went up against Kings College for the programme which aired on 18 December 2023.

They lost with 120 points to Kings’ 155, with BBC host Amol Rajan suggesting to the City team that it was “more of a Christmas conversation than a quiz from your point of view”.

Team captain Mr Crowley, a 2007 alumnus of the Broadcast MA, who now reports for One Show, and has presented several Panorama programmes, said: “We had all sorts of fear going into it, but it was so fun, and we came out absolutely buzzing.

“We knew going in that as three journalists and a lawyer, we didn’t have the greatest depth of knowledge, but we did pretty well. We got enough points to be respectable.”

The team answered questions on a wide range of topics, including French dishes, UK plays from 2023, and scientific anniversaries.

The show marked the first Christmas special with journalist and broadcaster Mr Rajan at the helm, following his succession to

the role in July 2023, taking over from Jeremy Paxman.

Ms Tsjeng, who graduated from the Magazine MA in 2012, and was most recently editor-in-chief of Vice, said: “Amol was a delight to film with, cracking jokes while the cameras were off. He made us all feel very comfortable.”

She added: “I hit up a former University Challenge champion I knew for advice. His words of wisdom were: ‘Press hard on the buzzer, it is surprisingly sticky!’”

Two City journalism graduates have been recognised for their survivorinformed reporting at the 2023 Write to End Violence Against Women Awards.

Newspaper MA alumna Connie Dimsdale, who graduated in 2021, and is now a reporter at The i, won in the ‘Best News’ category for her piece titled: “‘I was groomed on Facebook’: Child abuse victims demand action to tackle targeting of girls online”.

“It was such an honour to win,” she said, “particularly

given how much amazing work was in the category.”

The piece featured a sensitive interview with a child sexual abuse survivor urging Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to bolster protection for women and girls in the Online Safety Bill.

Ms Dimsdale added: “Frida was very brave to share her personal experience of being groomed on Facebook by a 30-year-old man when she was 13, and the piece would not have been the same without her testimony.”

Charlotte Wace, a 2015 Newspaper MA graduate, shared the ‘Best Investigation’ award with colleagues at The Times for their reporting of the Russell Brand sexual assault allegations. “I can definitely say that awards never even crossed our minds while we were working on it,” she said. “We just wanted to get it over the line and tell those stories - but it’s obviously really nice that the work that went into it has been recognised.”

Caitlin Barr

The investigative journalist who broke the Russell Brand scandal, alongside Charlotte Wace, speaks to Sarah Kennelly about justice, collaboration and the libel laws that protect the rich

You once applied for the MI6; were you always driven to chase a career in investigative journalism?

To be honest, I became a journalist by accident. It was the only industry that would have me in the end. I was never one of those people who had a plan. And then I suddenly thought, I’ve got to apply to something. So, I applied for the MI6 because I discovered I love telling people things they don’t know, it’s just a glorified form of passing on gossip. But I didn’t get through, they rightly rooted me out.

Do you think that journalists can help to deliver justice in the #MeToo movement?

I’m not a judge or a jury. But it’s a difficult balancing line because we have a system that doesn’t deliver justice to people very often. I think we’ve got to take our responsibility seriously as journalists but with the caveat that we are not the police, the jury, or a judge. So, we’re not delivering justice in that sense but I think we can help in productive ways. Sometimes you’re in a difficult position where you feel like you’re taking on a lot of somebody’s emotional load and I’m not trained to do that. I want to be sensitive to their needs but, at the same time, I don’t have any formal training in counselling and I don’t want to overstep the mark by saying something that’s wrong.

You gave birth to a son shortly before you broke the Russell Brand story. Do you think there’s an unfair standard placed on women in journalism to work outside of their maternity leave?

That was a personal choice, work wasn’t putting pressure on me to continue. But I felt like I owed it to the women to finish it. I don’t think other people should do what I did if they didn’t want to. The industry is contracting. And there isn’t enough time to do long-term investigations. So, you end up doing them in your own time. For most of us, we’re also doing a day job but then doing investigations on the side. But if you have young children, you don’t have that time around the edges because you’re trying to keep childcare down to fewer hours to keep the price down.

You have a WhatsApp group with other #MeToo journalists – is there a greater sense of collaboration with these stories compared to others?

How do you maintain boundaries to protect your mental health when writing about such difficult topics?

I think it’s very hard not to become emotionally invested but ultimately you’re a professional doing a job and you always have to have that in the back of your mind. But of course, you end up caring about people, I don’t think that’s intrinsically a bad thing. Otherwise, you’d be using them and that would be a terrible thing. And with my own mental health, I’m not going to say there’s no trauma in covering this stuff because there is. But I always remind myself these things did not happen to me and I’m lucky in that regard. I want to help women to speak out. You have to compartmentalise it a bit but it bleeds into your life. I can do this work but it’s not for everyone and that’s fine.

It’s not as though we’re constantly messaging each other but I wanted it to be there because this is emotionally draining work and knowing other people that do it might give you some support. But I also felt like there could be greater collaboration across publications because we get better journalism with knowledge. There’s always going to be competition between outlets. But I think there’s great potential to be a bit more collaborative. You can’t possibly do all these investigations yourself and sometimes it feels like the right thing to do. If there was a bit more willingness to work together in this industry, that could result in very good journalism.

Have the United Kingdom’s strict libel laws stunted the #MeToo movement here?

Definitely. I am a critic of our stringent libel laws. We don’t have libel laws, we have privacy laws. It’s a system that protects rich people. We have a system where these rich people can control the truth too much. And journalism is there to challenge that. I think it’s very important we do that. We’ve got to push back against that because it’s not conducive to free speech.

They say every journalist has a novel in them, meet the ones with a chart-topper.By Camille Bavera and Yasmin Vince

There are some reviews that tear musicians to shreds. They are brutal, unforgiving and souldestroying. Those being reviewed might be left wondering, “If the journalist knows so much, why don’t they get onstage themselves?”

Some have. There are a select few who know what it’s like to be both a journalist and a musician. They’ve written articles and songs, toured as musicians and press and been on both sides of a review. Five, both veterans and newcomers, tell XCity what that is like.

Naomi Larsson Piñeda is a musician and multimedia journalist of British-Chilean heritage, who was Political Editor at gal-dem prior to its closure in 2023. Her band has toured globally since.

Is it easier to express yourself through journalism or songwriting?

“There are many crossovers between my work as a journalist and songwriter.

"My new EP is about a relationship. I've written about it as an anonymous long read for The Guardian and a long read for ELLE. It's basically about sex addiction. It's the same experience of what happened, but in a more critical context that incorporates expert opinions. It's a different approach."

Growing up, what did you feel more drawn to?

“I’ve played guitar for ages, and then started writing songs when I was a teenager or maybe in my early 20s, but it was always just a hobby. Later, I realised that there’s a lot more to life than a job. The journalism world is difficult. You can’t put your eggs in one basket.”

After years of songwriting and a degree in popular music, Libby Driscoll panickedly reached out to a local magazine for work experience. She has since created an online magazine, FLARE, and plays with her band Quila Dreams.

Is promoting a magazine and band similar?

“The only shared process is social media. My process with FLARE is structured due to deadlines. But for Quila Dreams, promotion is on more of a ‘as-and-when’ basis. It’s easy to put too much pressure on your art, which can completely outweigh the rawness of simply creating.”

Would you rather be known for journalism or music?

“I don’t have a preference but journalism is my job and music is more of a cathartic process, a creative outlet. I plan on being more proactive with my music in the coming year. I released a single, Paisley and her Flowers in January with Quila Dreams. But both music and journalism are fulfilling avenues.”

Naomi Larsson Piñeda Courtesy of Chris Patmore

Garry Bushell has been namechecked in three songs because he writes vicious reviews. This includes Press Darlings by Adam and the Ants, which responded to Bushell’s claims that they “wear their pretensions on their sleeve” by implying that he had no taste. Yet, Bushell has been in several bands throughout his 50-year career.

50 years is a long time. What’s your best ‘on-the-road’ story?

“Printable ones? I think singing Buy Me A Drink You Bastard and coming offstage to be greeted with four whiskies and several pints. That was at the Viper Room in Hollywood in 2017. Never happens in England. I also went to New York with The Specials. I got a lift to the gig with Debbie Harry and Chris Stein, which was unexpected. We bumped into Andy Warhol at the venue. The night ended disgracefully.”

“Disgracefully,” how?

“I’ve learnt to be cautious in interviews. A throw away line could sink a career. So I think I’ll spare you the details.”

Jerry Thackray performed as “The Legend”. The name came from Alan McGee, who founded Creation Records; he thought it was funny to introduce the dullest person he knew as “The Legendary Jerry Thackray”. Under an alias, Everett True, he became an infamous Melody Maker writer.

Did you get to interview any of the other acts McGee discovered?

“I tried not to. When I started writing, I was writing about myself. I felt that no one cared about what I did, so if I didn’t write about myself, no one else ever would. I also fell out quite badly with the Creation Records lot a long time ago. For instance, it’s been 40 years since they last saw me, but the Jesus and Mary Chain took a dig at me in The Guardian at the end of January.”

Do you find it easier to express yourself through writing music or journalism?

“Growing up, it was writing because everyone wanted you to rehearse music. I think rehearsing music is fundamentally dishonest. You write heartfelt lyrics and then practise them hundreds of times until they are not heartfelt anymore. But in 2000, I started playing with improvisational musicians. I finally found my niche and could express myself spontaneously on stage. Now, whether it’s written or performance, I can express myself easily. As long as I don’t have to rehearse it first.”

For Julianne Regan, ‘writing’ initially meant journalism at Zig Zag magazine. She was sent to interview the band Gene Loves Jezebel, after which she left the magazine, and became their bassist. From there, she went on to cofound All About Eve.

What’s it like being interviewed, and reviewed knowing what the process is on the other side?

“I had a lyric in a song that referenced ‘jewels in Elysian pools’. I know that they’re actually ‘fields’ but where’s the rhyme in that? A journalist felt they had to point this supposed error out to me in print. Clearly they had no understanding of poetic licence. I’d have liked to have seen that copy before it went out and to have torn a little strip off the journalist, but ever so gently.”

Have you interviewed one of your musical heroes?

“One night after seeing a band called Gene Loves Jezebel play, I tracked them down and asked to interview them. I then stayed (as their bassist) for about 10 months or so and left as there was quite a lot of fighting between other band members, but it was a thrilling baptism of fire. The piece I wrote was naive and awkward, but I was proud of it, even though the opening line was; ‘At last a welcome enema has been shoved up the weary backside of a stagnating scene’.”

Garry Bushell Courtesy of Garry BushellStrictly, social media, and the unique buzz of live broadcasting. Ceci Browning and Lotte Brundle get the low down

Exhausted, Krishnan Guru-Murthy is slouched on a sofa wearing a dark green sweatshirt, which is somewhat disappointing considering that over the last six months most of his days have involved sparkles, sequins, spandex, or all three at once.

First, on Strictly Come Dancing, and more recently as part of the Strictly Come Dancing Live Tour. He’s 24 performances down – only six to go – and seems visibly relieved.

“It’s weird because it’s not the same as the TV show,” he explains. “Most of the celebrities sign up to the tour because they’re bereft that they’re out of the show and want to carry on the journey, but you very quickly realise that you basically signed up to a pantomime.

“It’s good fun, but it’s totally different. And it goes on forever. Your mind is totally scrambled. You have no idea what day it is or where you are or what city you’re in, because you do a show and then you jump on a bus and go somewhere else. We’re all sort of broken.”

Before the Saturday prime-time show threw him under a different kind of spotlight, Guru-Murthy was best known as the lead presenter of Channel 4 News. Over the course of an almost three-decade career, the 53-year-old has reported on almost every major story, including 9/11, the Mumbai attacks, and conflicts in Syria, Yemen, and Gaza.

“I definitely get an adrenaline buzz from doing the news every night,” he admits. “I’m on a high when I come off air, and it takes me an hour and a half or so to decompress. The Strictly nerves were different because I was totally out of my comfort zone. The likelihood of making a complete fool of myself was really quite high.”

Along with fellow journalist Angela Rippon, Guru-Murthy was a firm fan favourite on the show. Audiences were both shocked and impressed that he’d dropped over two stone in preparation for the competition. He was booted out in Week Eight, but not before scoring 30 points from the judges for his Cabaret-themed Charleston. “I felt nerves I haven’t felt since I was a kid. I had wobbly legs while waiting to go on. It’s really interesting that I don’t feel that at all on tour.”

“I don’t get the same buzz dancing as I do covering breaking news”

Despite the pre-performance jitters, Guru-Murthy was surprised to discover that nothing could match the rush that broadcast journalism brings him. “I don’t get the same buzz dancing in these massive arenas full of thousands of people as I do covering a breaking news story or doing a good interview,” he says. “That’s been quite revealing to me.”

Live television is what invigorates Guru-Murthy the most, but this is not without its downsides. While mostly supportive, some viewers have been quick to criticise him online for his unforgiving interviewing style.

“We all know that social media isn’t the same as real life. What you’re doing can very easily become the focus of a particular group of quite active users, and it might be supportive of what you’re doing or it might be critical of what you’re doing, but either way, you’ve got to be very wary of it.”

It’s easy to wonder whether Guru-Murthy is referring to one of his many viral moments, such as when he mistakenly called a Tory MP a “c***” live on air, unaware that his microphone had been left on, or when director Quentin Tarantino angrily told him “I’m shutting your butt down” after a particularly vigorous round of questioning. More recently, he was caught using his mobile phone at the wheel of his

Tesla in rush hour traffic. Despite this, it seems that he remains largely unbothered.

According to the presenter, platforms like X and Instagram can become echo chambers that tend not to reflect wider public sentiment: “It’s a particular self-selecting audience. Before, you had to be really engaged with something to be bothered to write a letter and put a stamp on it and post it. Now, people will just fire off any old thing.”

That’s not to say he doesn’t use these apps, though. He has over 700,000 followers on X and posts almost daily, with diverse updates ranging from family snaps to clips of chats with world leaders.

Some positives have come with the internet age too, Guru-Murthy admits. When he started out at the BBC, working on the discussion programme Open to Questions as a fresh-faced University of Oxford student, the landscape looked very different – any story worth breaking required a huge amount of effort.

“We can’t cover current wars the way that we traditionally have”

“It was very hard to set anything up,” he says. “If you were filming in the developing world, a lot of people didn’t have telephones. If you were trying to plan something in Pakistan or India or wherever in the late 80s, the chances are that you wouldn’t be able to. You had to fly somewhere, go there, and do it on the ground.”

Now, digital communication tools are integral for all kinds of journalism, not just broadcast. They are both where information comes from and how it is spread.

“We can’t cover current wars the way we traditionally have,” he explains. “I was in Gaza the last time there was a war, but we can’t go there now, so we are totally reliant on people we can hire remotely to work for us, and on imagery and video that has been shot by anybody with a mobile phone or a camera and uploaded to the Internet. Without that kind of technology none of us would be seeing anything. We wouldn’t know what was going on.”

Comfortable as he is between the four purple walls of the Channel 4 studio, Guru-Murthy seems to miss being on the ground. “As soon as we can get into Gaza, we will. Everyone’s desperate to go. But we can’t at the moment because we’re not allowed in by Israel.”

His main criticism of the state of journalism, however, is not this threat to press access. Rather, what frustrates him is the tendency of reporters to wear blinkers – to become obsessed with whatever story they’re pursuing at a particular time to the detriment of other, equally important scoops.

“I think from Covid onwards we’ve been in this environment in which the news is totally dominated by one story,” he confesses. “That might be the Ukraine war or the Middle East or whatever it is. We’re not very good at having a balance of news.

“On the internet, algorithms learn what you’re watching and you end up in a hole of a particular topic. Broadcast journalism is mimicking that in terms of what it serves people. If you look at mainstream programmes, they’re spending a lot more on a single topic than they used to. We need to return to a broader news agenda.”

To Guru-Murthy, this boils down to dwindling resources. In an international arena of crisis after crisis, there’s simply not enough money, equipment, or people to go around. But he’s quick to take some accountability on behalf of the industry.

“There seems to be a lot more repetition on the BBC than there used to be. The challenge is being comprehensive, making genuine programmes that serve domestic and international stories. It’s entirely our responsibility, the media, in terms of what we are delivering.”

With a general election approaching, fair coverage is a task set to get even trickier. Not only are there legal requirements during a campaign, demanding the inclusion of all relevant voices, but even interviewers like Guru-Murthy find themselves grappling with the slippery tentacles of public relations managers.

“You’ve got to be careful to not be hoodwinked into covering things that aren’t really news,” he clarifies, frowning through his glasses. “Pretty much every political story is part of an election campaign. There’s no end of ‘political announcements’ now by people who just want to get their face on the telly. They will all stick to the agendas that they’re comfortable with, ad nauseam. Reporting requires a bit more thought. I have to be extra vigilant because I’m in an election campaign and I’m influencing the way people are going to vote.”

the public outcry, and promises from Silicon Valley that they would reform their platforms, Guru-Murthy isn’t convinced that this year will be any different.

“There’s lots of talk about how this is going to be the dirtiest election ever, but I’ve heard that a million times before,” he asserts. “There have always been dirty tricks in elections, some questionable political advertising. We’ve got to work out where it’s happening and what they’re doing. Like all elections, this one will be decided by a relatively small bunch of people who haven’t quite made up their minds yet. They become very important for parties to reach.”

“The media landscape has changed this election. We have partisan channels now”

No stranger to political reporting, the Channel 4 regular has covered five general elections and hosted political discussion shows such as Ask the Chancellors, a key debate between the chancellor of the exchequer and his opponents in 2010. After a string of unelected prime ministers – May, Truss, Sunak – does he think anything will be different this time around?

Ahead of the 2016 election, consulting firm Cambridge Analytica collected the personal data of millions of Facebook users without their consent, then used it to encourage swing voters across the country to vote in favour of Brexit. Despite

“The media landscape has changed this election,” he responds. “We effectively have partisan channels now. Recently, I saw a video of Rishi Sunak on GB News doing a TV promo for a discussion programme he’s doing with them. Politicians can choose channels and interviewers that they think favour them more easily.”

Courtesy of Channel 4

Guru-Murthy thinks that the Conservative Party could decide to channel their messaging to a core support base through GB News, which is where a growing number of their loyal voters get their news from. “That’s one thing we gotta keep an eye on, you know?”

While it’s important to him that he keeps up with the broadcast output of other channels, he is belligerent when it comes to suggestions that he’d ever leave Channel 4. He makes it clear that the BBC could never get him on the Six O’Clock News