Count Magazine

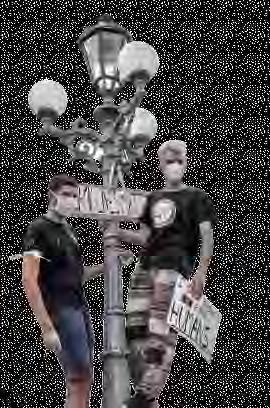

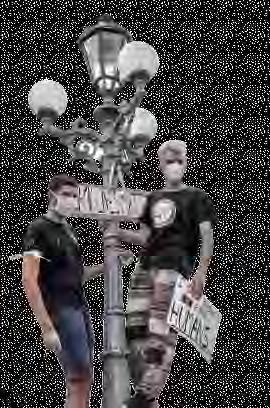

A SUMMER OF PROTEST

Youth take politics to the streets

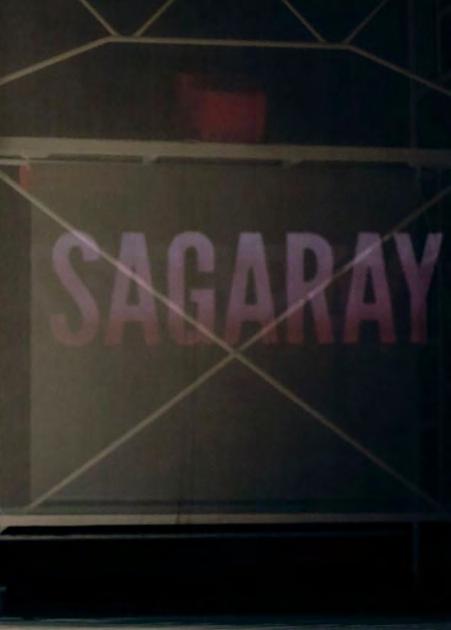

WHITHER GEORGIA?

Between Russia and Europe

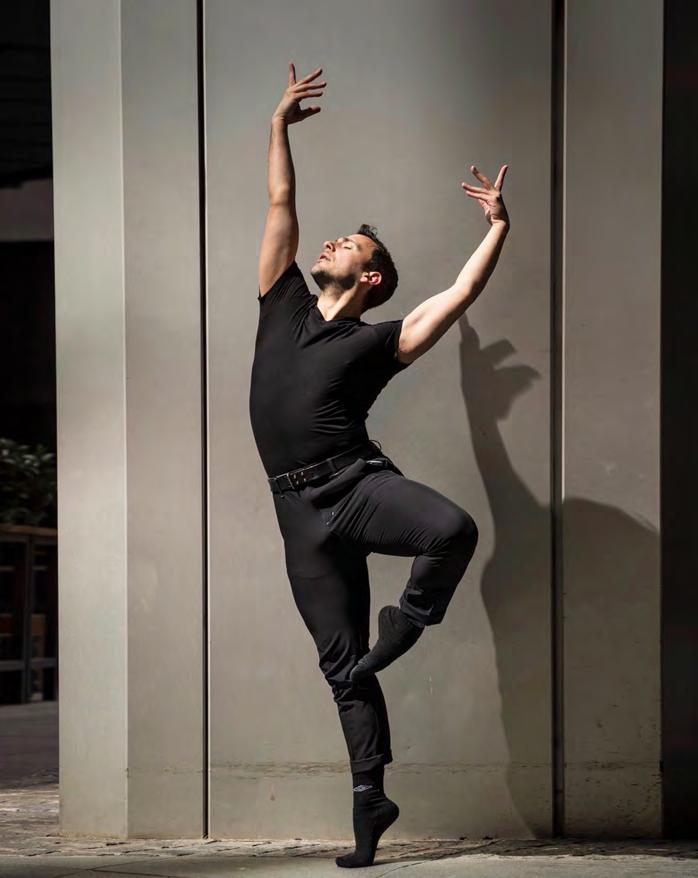

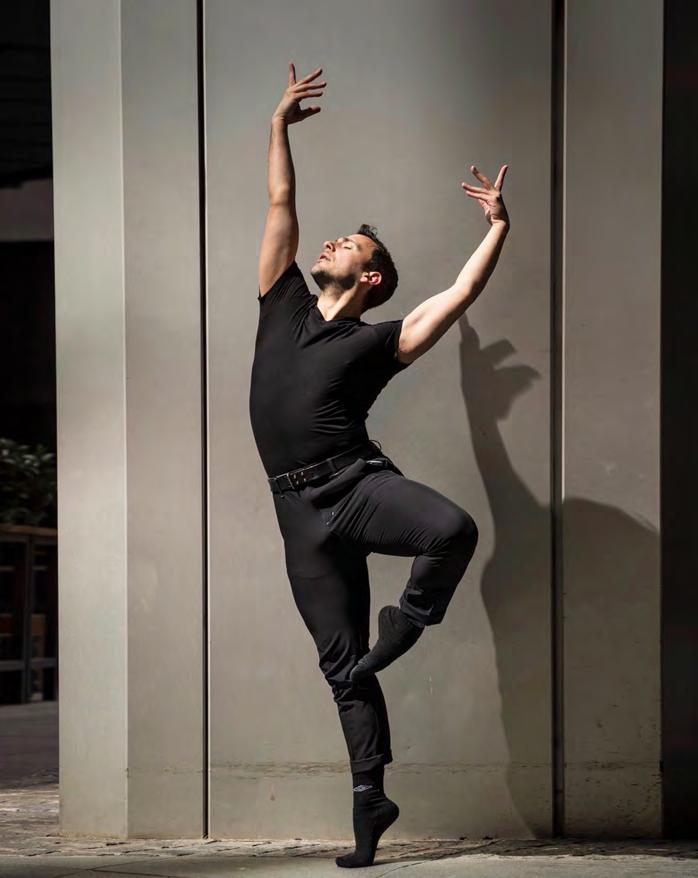

BREAKING THROUGH WALLS

An Israeli activist for Palestinian equality

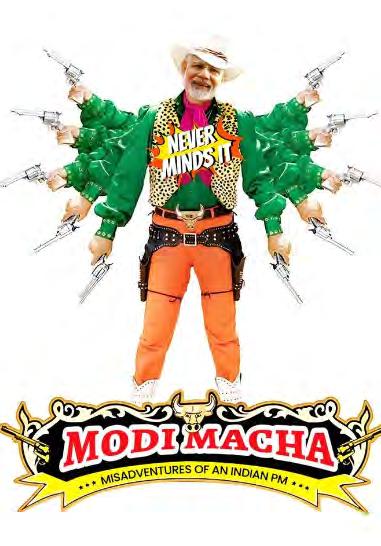

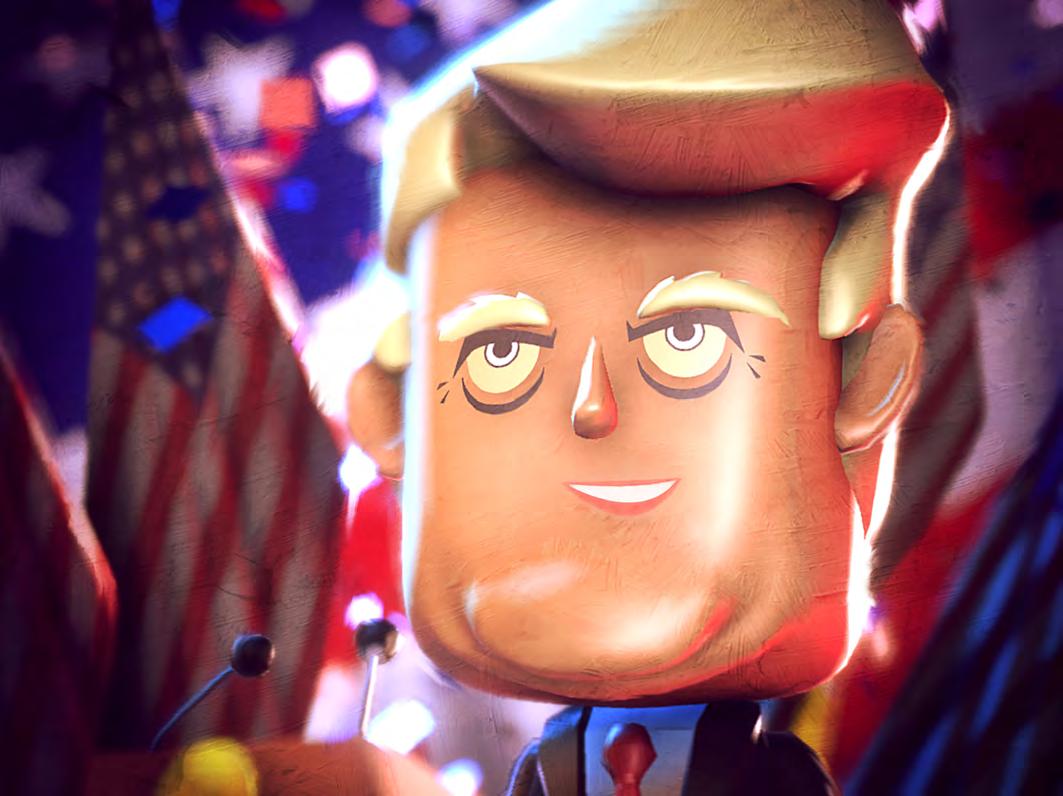

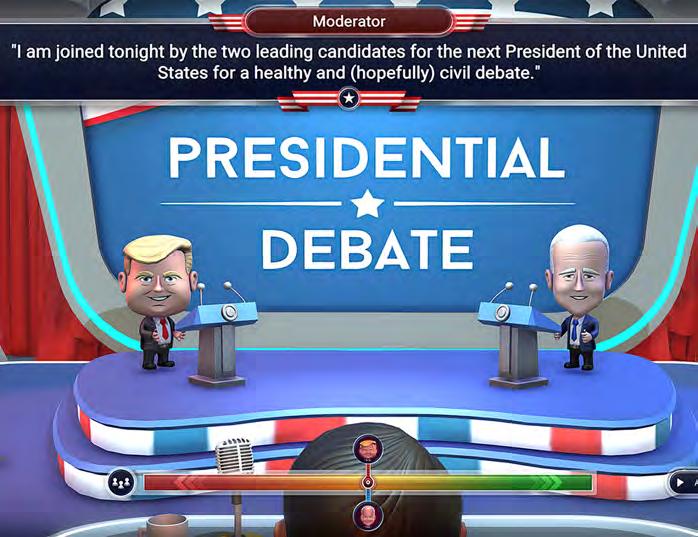

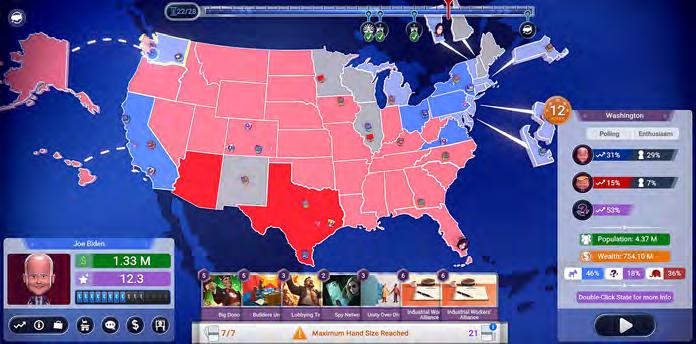

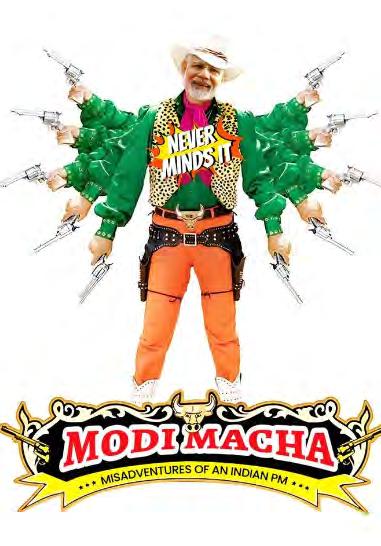

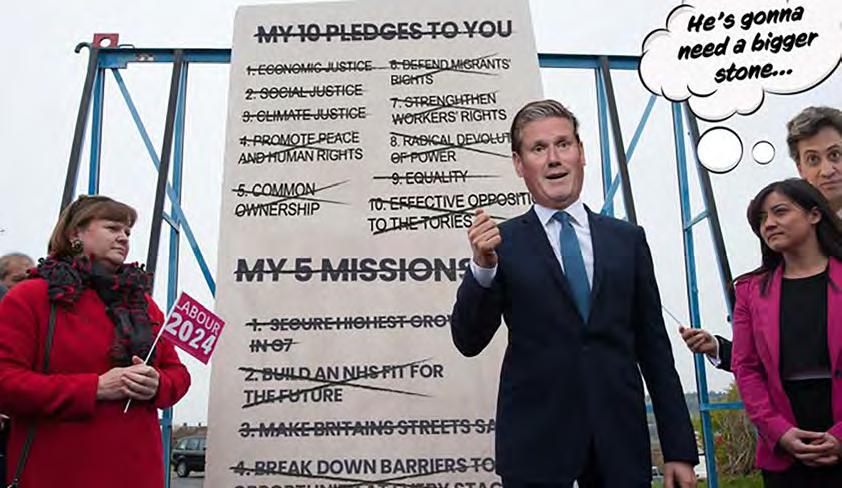

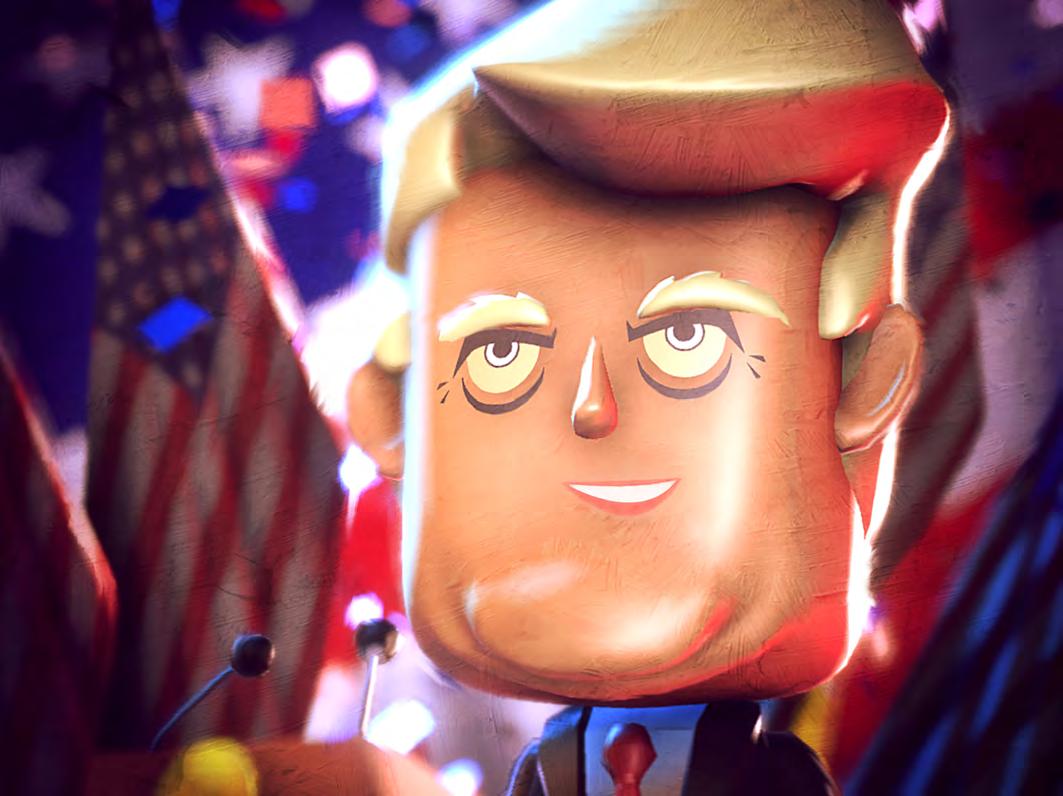

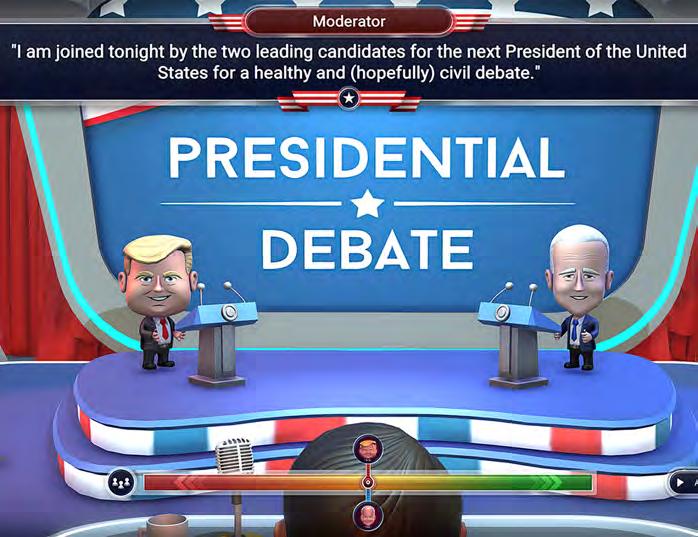

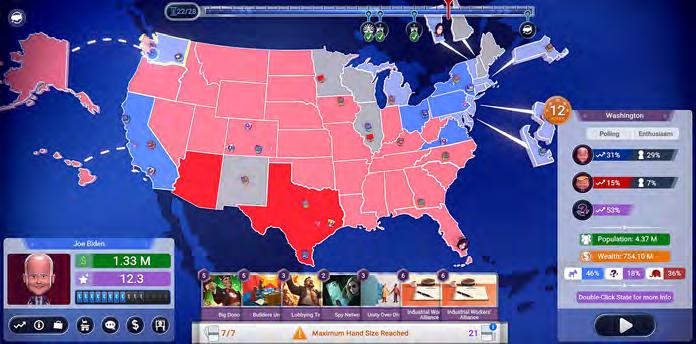

HOUSE OF MEMELORDS

Political satire to grab voters

Justine Noble Deputy Editor-in-Chief

Eliana Nunes International Editor

Jamie Onslow Sub-editor

Cahal McAuley Production Editor

Vasiliki Tsekoura Art Director

Kai Kong Photo Editor

Roberta Spada Social Media Editor

Alex Daud Briggs Digital Editor

Heleena Panicker Digital Editor

Jasper Goddard Podcast Editor

Dara Zheleva Reporter

Anastasiia Udesiani Reporter

Abdi Abdalla Sub-editor

Spenser Surerus Art Director

Dom Plaskota Civic Action Editor

Lilian Crastan Culture Editor

Mia Jeronimus Chief Sub-editor

Lara Lovric Deputy Editor-in-Chief

Calum Taylor Voices Editor

Ana Garcia Sancho News Editor

Justine Noble Deputy Editor-in-Chief

Eliana Nunes International Editor

Jamie Onslow Sub-editor

Cahal McAuley Production Editor

Vasiliki Tsekoura Art Director

Kai Kong Photo Editor

Roberta Spada Social Media Editor

Alex Daud Briggs Digital Editor

Heleena Panicker Digital Editor

Jasper Goddard Podcast Editor

Dara Zheleva Reporter

Anastasiia Udesiani Reporter

Abdi Abdalla Sub-editor

Spenser Surerus Art Director

Dom Plaskota Civic Action Editor

Lilian Crastan Culture Editor

Mia Jeronimus Chief Sub-editor

Lara Lovric Deputy Editor-in-Chief

Calum Taylor Voices Editor

Ana Garcia Sancho News Editor

Alice de Souza Editor-in-Chief

Alice de Souza Editor-in-Chief

Letter from the Editor

Dear Reader,

This is a monumental year for global democracy. Over 2 billion people, including the citizens of eight out of ten of the world’s most populous countries, have gone or are headed to the polls. Almost a quarter of the world’s population is choosing their representatives, many are advocating for their beliefs and defending democratic values.

Count is a magazine about the future of democracy, its transformations, and its challenges. We spotlight people and groups engaged in – and thinking of new ways to do – democratic politics. We at Count understand that politics doesn’t just take place at the polling station but also on the streets through individual and collective action. We believe in a future in which everyone has the right to vote and express themselves freely.

These pages contain stories about this super-election year on four continents. We hope our articles can show hope for finding new ways to promote democratic values.

Count Magazine was created as part of the 2023-2024 International Journalism postgraduate course at City, University of London.

Count Magazine Department of Journalism City University Northampton Square London

EC1V 0HB

TEL: 020 7040 8221

Email: countmagazine24@gmail.com journalism@city.com

Website: www.countmag.com

Printed by Rapidity

Count is produced by a team from 13 countries. We hope our diverse experiences and perspectives can help us illustrate our world’s growing anxieties; how authoritarian and populist leaders are achieving power through the ballot box in Indonesia and El Salvador, how the right to protest is at risk in the UK and how civil society in Georgia and Tunisia are struggling to survive.

We also show how politics is playfully and sharply expressed outside of formal spaces, through various media such as memes, theatre, cinema, music, and even video games. These stories should show that the fight to save democracy is alive and well. It’s championed by people young and old from all walks of life, from a transgender councillor who is working for local change in the UK, to an Israeli activist who is fighting for Palestinian rights, and a young Italian who is putting the climate crisis at the centre of his activism.

With democracy at risk globally, we hope these pages leave you with the understanding that your voice and vote count!

Alice de Souza Editor-in-Chief

Alice de Souza Editor-in-Chief

Action News

Contents Civic

2 4 Overwhelming odds of Labour victory force bookies to adapt 4

candidates

of

politics 5

two-year delay 5

complicated and restrictive first

Senate election leaves citizens confused 6 ¡SORPRESA!: London’s Mexicans surprise at reelection of migrant congressman 6 Electronic voting under scrutiny in Brazil and India 7 Ignoring climate will deter young from voting, campaigners warn 10 Rights restricted 11 Citizens assemble! 12 Who will speak for Speaker’s Corner? 14 The elephant in the room 16 A summer of protest 18 Young, bold, and breaking the mold 19 An end to the two-horse race? 20 An election in the fog of war 22 Votes for kids

It’s no joke – UK’s satirical

make serious work

putting humour into

Kurdistan to hold elections after

Thailand’s

post-coup

Culture

3 28 Bodies on the ballot 30 Queer Texans and the race to the White House 32 To vote or not to vote? 33 Don’t blame the pollsters 34 House of memelords 36 Social media rebrand of Asia’s strongmen 38 Leading with an iron fist 40 Barriers at the ballot box 41 An unrecognised democracy 42 Black women resist Tunisia’s backslide 44 Georgia at the crossroads 46 Ukraine’s election dilemma 52 Passing the baton 54 Folk the system 55 A view from West Jerusalem 56 Radical hope 57 Called to climate action 58 Parklife 60 Making politics ‘sexy’ 62 Hit the notes, get the votes 64 Pop the vote! 66 Playing president 68 Fear and loathing in dystopian films

International Voices

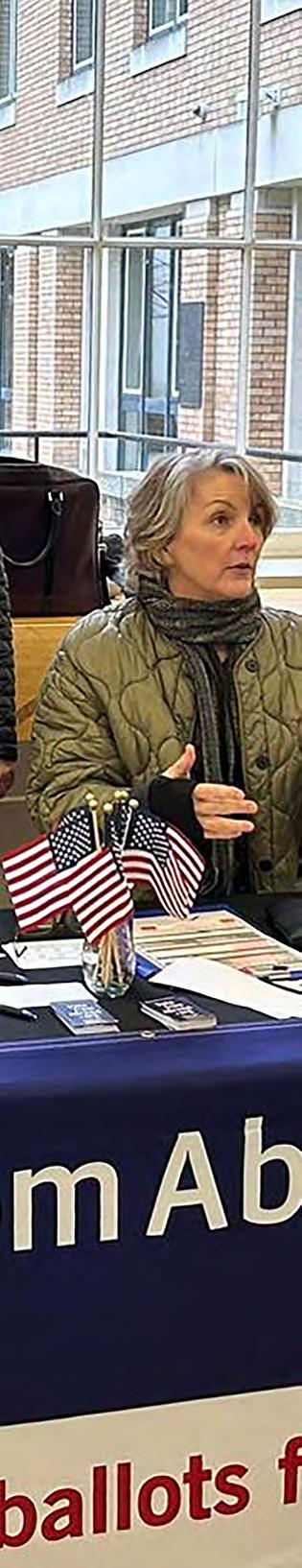

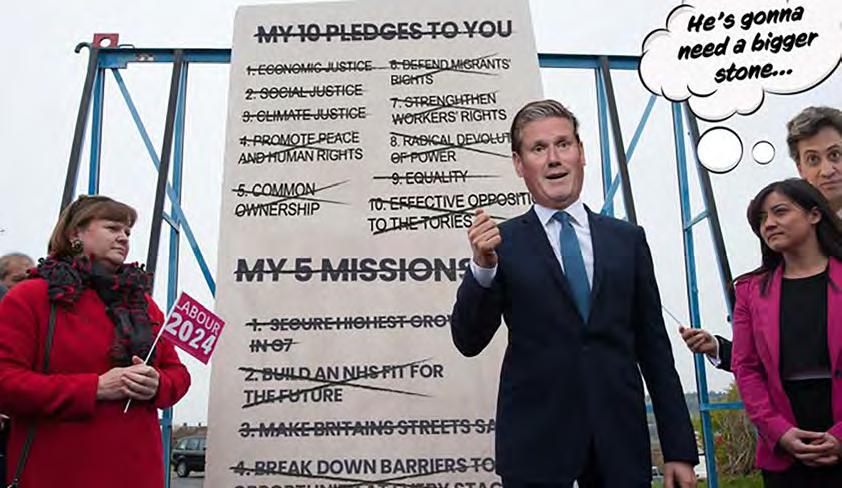

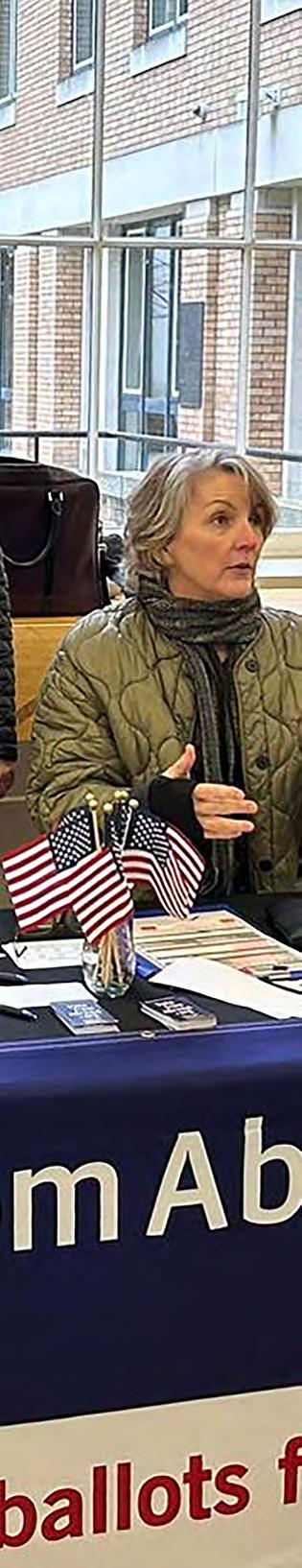

Overwhelming odds of Labour victory force bookies to adapt

Calum Taylor

The general election campaign has now passed its halfway mark, but the Labour Party remain odds on to topple the incumbent Conservatives, according to both the bookies and opinion polls.

With three weeks left until polling day, the betting comparison site OddsChecker shows the odds are skewed towards a solid Labour victory, suggesting around a 97 per cent probability that the party wins the most seats at 1/41. This means a punter would win £1 for every £41 bet on a Labour win.

This aligns with widespread polling trends that predict a similar outcome, making the current election different to some more closely fought political contests in recent years such as the 2016 EU referendum and the 2020 US election.

Leighton Vaughan Williams, professor of economics at Nottingham Trent University, said: “2024 does present certain challenges for betting companies.” He added that when the outcome looks highly predictable, “the odds can become heavily skewed, reducing the incentive for bettors to participate and limiting the profitability for bookmakers.”

While some punters are deterred by this, many bookmakers remain optimistic.

“The prospect of a UK General Election in 2024 is particularly exciting for us,” said Kayley Cornelius, Political Specialist at bookmaker Betfred – “regardless of the polls and odds on the main outcomes.”

“Having a short favourite can be advantageous, attracting high-stake punters who bet on heavy odds favourites. For instance, we have had customers willing to stake £100,000 on a 1/10 shot to win £10,000, confident in their research and the polling data.”

But no bet is safe, and election campaigns can be volatile. For instance, when Prime Minister Theresa May called a snap general election in 2017, the odds for a Conservative majority were immensely favourable (2/11, or an 85 per cent likelihood). She later lost her majority.

Since the mid-2010s, betting on politics has boomed in popularity, fuelled partly by smartphones making it easier to access gambling platforms.

For Williams, the consequences for democracy are two-sided. Although betting can “enhance political engagement and provide additional data”, it can also “contribute to the commodification of democratic processes” and “potentially influence the behaviour of politicians and voters”.

If you have concerns about gambling, help is available at the National Gambling Helpline. Call 808 8020 133 for free information, support and counselling, available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

No joke: Satirical candidates make serious work of using humour

Roberta Spada

With at least 28 satirical candidates set to run in the upcoming general election, scholars say this very British phenomenon helps make politics more accessible.

“They are potentially a gateway drug into politics,” said Nicholas Holm, associate professor of media studies at Massey University in New Zealand. “These kinds of candidates often speak to people that have felt like they have been left out. It’s especially working class and impoverished youth, especially racialised youth.”

Howling Laud Hope, leader of the Monster Raving Looney Party, who is standing to represent northeast Hampshire, said: “We are the only party that’s on everybody’s side. We are the people’s party really.”

The Monster Raving Looney party was established in 1982 and is part of a tradition of satirical candidates, political figures and parties that use satire to shed light on sociopolitical issues.

“We have a laugh and joke but underneath it has many, many serious things,” said Howling Laud Hope. “The others are the joke,” he added.

Holm said these candidates’ approach helps people to emotionally connect to a political discourse that has become overly serious. “The use of humour makes it more attractive and amenable to a population who might not be as open to the critique if it were

expressed in non-humorous terms,” he explained.

For instance, one prominent satirical candidate, Count Binface, has called for a cap on the price of croissants, as well as building “at least one affordable house” in his latest manifesto. He is both mocking but also higlighting the current UK cost-of-living-crisis.

Satirical candidates have been livening up debates, creating chaos, and pushing for new policies in UK politics for decades.

Some of their achievements include campaigns for pet passports and lowering the voting age from 21 to 18. They don’t want to stop there – the Monster Raving Looney Party wants to give 5-year-olds the vote, to match what, according to them, is the behaviour of MPs in Parliament.

“If you don’t usually vote, then vote unusually,” said Hope.

4

Howling Laud Hope, the Monster Raving Looney Party

Monster Raving Looney Party

Members of the Monster Raving Looney Party

Monster

Raving Looney

Iraqi Kurdistan to hold elections after two-year delay

Eliana Nunes

Iraq’s Independent High Electoral Commission has proposed that long-overdue parliamentary elections in the semiautonomous region of Kurdistan will be held on 5 September.

The nearly two-year delay in holding the elections highlights the challenges of maintaining democracy in Kurdistan, which is home to over 6.5 million people.

“The central Iraqi government and the Kurdistan Regional Government [KRG] usually disagree on various issues including power-sharing,” Mehdi Dehnavi, a Middle Eastern affairs analyst, explained.

Their most recent disagreement was over the Kurdistan parliament’s electoral system. The ruling Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) boycotted elections that were scheduled for this month, after accusing the Federal Supreme Court of Iraq of making “unconstitutional” changes to the make-up of the parliament.

In February, the Iraqi court, established as an arbiter between the governments of Iraq and Kurdistan, eliminated the Kurdish parliament’s 11 quota seats for minorities –

five of which have since been restored. These minority seats typically support the KDP and enabled the party to achieve its majority in 2018.

Michael Rubin, an author on Kurdistan and senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, said the recent election delay had nothing to do with democracy, but was in fact a strategy to benefit the KDP government led by President Nechirvan Barzani and his cousin, Prime Minister Masrour Barzani.

“While the Barzanis control enough of the mechanism to win any election,” Rubin said, “Masrour Barzani is afraid that losing votes – a near certainty – would show him to be weak.”

But the KRG spokesperson, Peshawa Hawramani, told Count: “The Kurdistan Regional Government will do anything to ensure the elections take place.” Hawramani added that consistent election delays – the result of “disagreements between parties” –have caused “huge problems for Kurdistan’s legislative institutions”.

According to analyst Dehnavi, before September’s elections: “It is first necessary to strengthen non-partisan institutions

such as [Iraq’s] Independent High Electoral Commission to manage electoral processes transparently and fairly, free from party influence.”

Dehnavi said that if these issues are not resolved, another election delay could “have significantly negative impacts on issues of regional legitimacy”.

Thailand’s complicated and restrictive first post-coup Senate election leaves citizens confused

Alex Daud Briggs

Voting has begun in Thailand’s first post-coup Senate elections on 9 June, with the second of three rounds taking place on 16 June. But most Thais won’t be able to vote.

This is because the franchise is restricted to the 46,206 people who have been approved to stand in the race, to choose 200 senators in what some commentators have described as the most complicated elections in the world.

The candidates, who have been ‘self-voting’, must not belong to any political party or have held any prior political office. They also

need to belong to 20 occupational groups and categories, including “arts” “tech” and “women”.

Critics argue that the system is undemocratic. Content creator Norrachai Anansakdakul said “It doesn’t reflect democracy. To apply and vote, you need to pay a high fee of 2,500 baht (£53).

Candidates must be above 40 and have ten years of work experience, meaning many people won’t participate.”

Information about the election has also been scarce, with limited publicity and candidates barred from campaigning

beyond posting a profile on the Electoral Commission website.

A student, who wished to be identified under the alias Pond, said she only learned about the elections a few weeks ago through a podcast. She noted that many of her peers also learned about it recently and found the voting system difficult to understand.

“There is one group for health and another for all elderly and minorities together,” Pond said. “They claim it keeps the election clean, but what stops people in different groups from making deals with each other to get voted?”

The new senate will replace one that was appointed by the military junta after the 2014 coup and is supposed to transition authority to regular citizens.

Nanyang University political professor Duncan McCargo said the complex system is being used because the junta and conservative elites who support the monarchy believe elected politicians are easily corrupted and see the senate as “wise elders”, who can keep them in check without being “tempted” themselves.

“This self-selected senate is supposed to be a force above politics,” McCargo said. “Critics, however, argue it’s to ensure the senate is composed of individuals who will not rock the boat, following their [the junta’s] influence.”

McCargo noted that information around the elections is “vague, and most people just can’t even get their heads around it”.

NEWS

5 Supanut Arunoprayote

Levi Meir Clancy

Sappaya-Sapasathan, the Thai Senate and parliament building in Bangkok.

¡SORPRESA!: London’s Mexicans surprise at reelection of migrant congressman

Ana Garcia Sancho

Mexicans abroad have had a mixed reaction to news that Raul Torres was elected earlier this month to represent them as the migrant congressman for Mexico City.

Torres was elected in what were the largest elections in Mexico’s history, with polls at national, state and local levels, and which saw Claudia Sheinbaum win the race to become the country’s first female president.

The role of migrant congressman was created by the Mexico City Congress in 2021. An advisor to the city’s Electoral Institute said at the time that “the person would be a connection of the capital-dwellers away from their home”.

Three years on, Mexican voters in London were surprised to learn there was such a representative. “I didn’t know there was such a thing as a migrant congressman. I was a bit disappointed as I didn’t have time to research them. I would like to know their proposals, but I find it amazing that there is someone to speak for those of us that are away,” said Mariana, a student.

There are 12.27 million Mexicans living

abroad, the majority of them in the US. However, according to the National Electoral Institute only 100,156 Mexicans overseas registered to vote. Still fewer were eligible to vote for the migrant congressman as Mexico City is the only area in Mexico to have one – 24,036 former residents of the city were qualified to vote for the position.

“I am especially concerned that only Mexico City is represented. It feels exclusionary,” said Sofia, a Mexican studying engineering in the UK.

This is Torres’s second term. He represents the opposition coalition to the current government, and his campaign literature stated that he had enacted positive changes for Mexicans living overseas over the past three years. For example, he established a procedure for processing and sending drivers’ licences for overseas residents of the capital.

One former Mexico City resident and former campaigner for the Mexican Institutional Revolutionary Party, said he knew about the role and was familiar with the candidates before

casting his vote. “I was disappointed in the Zoom meetings that the candidates organised for the Mexicans in London,” said Manuel. “There was no proposal focused on us. They only cared about Mexicans in the United States. They don’t realise that at least half of us are not in the USA.”

Just 68,898 Mexican citizens in the US were registered to vote, meaning 30 per cent of overseas voters lived elsewhere.

Electronic voting under scrutiny in Brazil and India

Alice de Souza

Brazilians will be voting in municipal elections in October, the first polls to be held since former president Jair Bolsonaro was banned from holding office for eight years after judges ruled he had spread disinformation about Brazil’s electronic ballot boxes. Observers see the upcoming elections as a test of voters’ trust in electronic voting machines (EVMs).

Questions about and criticisms of electronic voting have been voiced in other countries, such as India and the US, two of the ten countries that will be using

electronic ballot boxes in elections this year, according to the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

In Brazil, around 153 million voters will cast their ballots through EVMs, with counts expected to be ready three hours after polling stations close. Despite their efficiency in providing results, the system has been subject to disinformation, including from the former president who claimed the elections in 2022 were rigged against him.

Although Brazil’s Supreme Electoral Court (TSE) censured Bolsonaro for making false claims, a survey published by the Genial/Quaest Institute last May found that 35 per cent of Brazilians still believe the machines were rigged.

“The critics want to disqualify the electronic ballot box to disqualify the democratic process. No single fraud case has been proven in the 28 years they have been used. Independent institutions analyse all complaints,” said Giuseppe Janino, former secretary of information technology at the TSE and one of the Brazilian electronic ballot box creators.

The Brazilian machine’s security scheme includes digital signatures and cryptography. In addition, the software is open a year before the elections for auditing by 15 institutions, including political parties and the Federal Police.

Meanwhile, in India, there were also disputes about ‘e-voting’ in this year’s elections. Although EVMs have been used in the country since 1982, a research institute published the Lokniti study ahead of the election that revealed concerns about the reliability of EVMs. The country’s Supreme Court rejected a petition against using the machines.

An Indian human rights lawyer, Rohit Sharma said he was confident about the integrity of the results overall, but added there were “some polling booths and rooms where EVMs are malfunctioning”.

Connie Sanchez

Electronic voting machines in Brazil

Luiz Roberto/Secom/TSE

6

Voting poll in Mexico City

Ignoring climate

will deter young people from voting, campaigners warn

Dom Plaskota

Green activists have cautioned that the lack of climate policy discussion by the Labour and Conservative parties ahead of the general election will increase apathy among young voters.

An organiser for climate protest group Extinction Rebellion Mack, who is in his twenties, blamed the UK’s first-past-the-post electoral system. “It’s a broken system. It’s in the interest of the main parties not to talk about it,” he said.

He spoke to Count at an Extinction

Rebellion protest outside the annual general meeting of oil and gas giant Shell in London the day before Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced the election would be held on 4 July.

Joe, another young protester, said: “I don’t think parliamentary politics is what it’s made out to be. I don’t think it’s driving people away from the two main parties. I think it means they won’t vote.”

A poll published by ITV and Savanta in April found over half of 18-25-year-olds

feel politicians don’t care about them. The respondents named the environment in their top five election issues alongside issues like housing and mental health.

Last year Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak backtracked on the UK’s net zero commitments and delayed the introduction of key climate policies, most notably a ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars which was postponed from 2030 to 2035.

In February, Labour Party leader Keir Starmer reduced the amount of green investment Labour pledged to spend if they win the election from £28bn to £4.7bn.

Liberal Democrat Councillor and Lead Member for Climate Change at Guildford Borough Council George Potter said young people would feel disillusioned because “the Conservatives have backtracked to appease the hard-right, and Labour have scrapped their climate plans because they want to appeal to Conservative voters and are assuming that progressive voters have nowhere else to go”.

However, green transition expert Dr Leanne Wilson from the Labour-controlled North East Combined Authority in northeast England stressed the need for pragmatism.

In a virtual panel organised by climate policy think tank Centre for Progressive Policy, she said: “There’s a huge amount of work being done. Sometimes I think there is a risk of making the perfect the enemy of the good.”

Extinction Rebellion Youth’s Joe being carried out of Shell’s annual general meeting

Dom Plaskota

NEWS Protest outside Shell’s annual general meeting 7

Dom Plaskota

Civic Action

Rights restricted

How the UK government pushed back against protesting

Roberta Spada

Anoisy crowd was marching through Oxford Street wearing keffiyehs and waving Palestinian flags, when Jacob, who for safety reasons does not want to disclose his real name, felt a tap on his shoulder. A police officer started asking questions about his placard reading “intifada till victory” – one of the many slogans the people around him were chanting. Under the slogan was an explanation of what intifada (“resistance” in Arabic) meant to him.

After answering several questions from the police officer, he walked away. Soon enough he felt a hand on his arm. Police dragged him to the other side of the road and started questioning him again.

An officer explained to Jacob that he was being arrested under the Public Order Act 2023 for displaying the word intifada.

Jacob says he remains under police investigation. His case is not unique. Arrests for similar reasons have become a reality in UK protests. The Public Order Act 2023 was the last step in a series of new laws passed by the Conservative government to crackdown on protests.

The law has granted the police greater

powers, lowering the threshold for what is considered “serious disruption”.

“Essentially you have to accept the fact that there’s a very good chance that you’re going to prison if you want to do a protest that is heard by anyone,” says Gabriella Ditton, an organiser from the climate activist group Just Stop Oil. “I don’t think most people understand that in order for a protest to be effective some people are going to be inconvenienced.”

The new laws allow the police to impose a start and finish time for protests and set noise limits. They also criminalise locking-on, where protesters attach themselves to a target, and any act which interferes with the use of key national infrastructure. The restrictions are now extended not only to protest marches but also to static demonstrations.

According to Katy Watts, a lawyer at the human rights association Liberty, these new offences target specific actions which have been a signature part of climate and racial justice activism’s strategy.

“It’s clear that the government is explicitly targeting people protesting about racial justice and the climate crisis,” Watts says.

“The government was determined not to

deal with [these issues]. It instead turned to criminalising people who are making their voices heard.”

While the government has targeted certain causes, the police have targeted certain people.

“I do think there was an element of racial profiling,” says Jacob, who is a brown man, about his own arrest. He says he was the only person arrested of those displaying the word intifada.

A May 2024 report by Netpol, a police monitoring network, on the policing of pro-Palestinian protests in Britain, found that “there has been a pattern of racial profiling at demonstrations that has included not only the targeting of Palestinians or Arabic-speaking protesters but also Black and brown children and young people.”

The report also found that there were systemic abuses of power from Police Scotland throughout the COP26 conference and its associated climate protests.

“Every copper thinks that they are a good person and [so] you can trust them with more power and they won’t use it when it’s not appropriate. But that is total and utter fiction,” claims Paul Stephens, a retired policeman turned climate activist. “There will be exceptions where it will be used in the wrong way.”

The right to protest is fundamental to democracy and is a right protected by international law and by Article 11 of the UK Human Rights Act.

“The law has created an atmosphere where people are uncertain about whether or not they can take to the streets to exercise their right to protest,” says Watts. “That [has a] real chilling effect on people.”

“This government fully supports the right of individuals to engage in peaceful protest,” says the Home Office website. “However, the serious disruption caused by a small minority of protestors has highlighted that more needs to be done to protect the public and businesses from these unacceptable actions.”

Crowds continue to fill the streets of the UK, in demonstrations for climate justice, human rights, and against war. As the country heads for a general election, it is yet to be seen how the legislation will continue to affect the right to protest.

Police overlooking pro-Palestine protest 2024

Family at pro-Palestine protest 2024

Police overlooking pro-Palestine protest 2024

Family at pro-Palestine protest 2024

10

Roberta Spada

Roberta Spada

Citizens assemble!

The climate movement’s shift into deliberative democracy

Jamie Onslow

After years at the forefront of UK climate activism, Clare Farrell concluded that without any real political power, the movement would continue to be ignored by politicians.

She likens the relationship between citizens and politicians in the UK to a “parent-child dynamic; we go outside and shout and say ‘pay me attention’ [but politicians] don’t listen”.

Farrell speaks from experience when it comes to going outside and shouting – she is a founding member of Extinction Rebellion, the group that kick-started a new era of climate protest in the UK in 2019.

Five years on, she is frustrated at the government’s lack of progress on climate goals. In Farrell’s view, if the political system isn’t responding, a new way of doing politics is needed.

“We want to build up power, for people to be self-organised”

So, in 2022, alongside fellow XR founder Roger Hallam, she started Humanity Project, a movement that aims to create a national network of “popular assemblies” – or “pops” –that will leave politicians with no choice but to take notice of their demands.

The group’s activities are in the tradition of deliberative democracy, in which citizens are

empowered to make policy decisions, rather than elected politicians.

Whilst Humanity Project are currently focusing on grassroots organising, one possible vision is the replacement of the House of Lords with a “House of Citizens”, according to a Humanity Project coordinator.

So far they have convened around 50 “pops” all over the country. The organisation’s facilitators work with local community groups who spread the word through outreach efforts.

At inaugural “pops”, the focus is on listening to the needs of local communities, which are then refined into an agenda. In June, Humanity Project will hold its first national assembly, an online event at which “pop” attendees picked at random from the local meetings will work on a national agenda.

Liam Killeen is a PhD researcher at Lancaster University studying the climate movement’s political organisation. He sees this development as born out of a “feeling of powerlessness”, exacerbated by the government’s increasing intolerance of disruptive protest.

“People are scared to protest,” he says. “We’ve seen attacks on the European Court of Human Rights, [and] the 2023 Public Order Act. Liberal democratic principles are under attack.”

Killeen is a firm believer in the potential held by deliberative democracy, where citizens – not elected representatives – make decisions on policy issues.

“One thing that you witness when you go to a self-organised, deliberative democratic forum is the transformation that people in the room experience from being really

disengaged to having their voice heard and appreciated,” he contends.

Humanity Project’s activities are part of a wider trend of experimentation with forms of deliberative democracy. The UK government held a national climate assembly in 2021, and dozens more councils have held their own citizens’ assemblies, often specifically on climate issues.

Killeen is sceptical of the way citizens’ assemblies have been used so far by government bodies. “What we’ve seen [with] citizens’ assemblies around the UK is that they’ll be instrumentalised,” he insists. “People pretend to be enamoured with the idea of deliberative democracy. But when push comes to shove, councils only really want recommendations that align with their current strategy.”

Farrell similarly says that the 2021 national climate assembly was ineffective because the government set the agenda: “They retain the power, so they can have the assembly and say, ‘You’ve all had a chat and we’ve listened to you and now we can ignore it if we want to’.”

Whilst its precise contours are still being worked out, Humanity Project’s vision is more radical. It would at minimum involve deliberative bodies having independent political power. “Without any sort of material power for the assembly to assert itself into the political space, it’s just a fancy focus group,” says Farrell. “We want to build up power, for people to be self-organised,” she adds.

It remains to be seen whether Humanity Project will be able to mobilise people on the scale managed by XR, or whether the political establishment will be any more amenable to this new form of activism. The group’s emphasis on extra-parliamentary organisation leaves them open to charges that they are encouraging disengagement from electoral politics. Luke Akehurst, a member of the Labour Party’s National Executive Committee, cautions against “the urge to have non-parliamentary forms of democracy”. “I would urge people to not lose faith with the conventional democratic process,” he adds.

Killen is clear, however, that groups like Humanity Project have the potential to invigorate our political process: “[It’s not that] either you act within the current democratic institutions, and therefore you’re democratic, or you act outside, and therefore you’re not.”

CIVIC ACTION 11

Neil Marshmen

‘Pop’ in Cornwall

Who will speak for Speakers’ Corner?

Historic site is a magnet for content creators

Alice de Souza

Standing on a small green foldable bench, a man gets a rise out of onlookers by calling for the sterilisation of all men and heterosexuals. “Please do the right thing. You’ll no longer be a danger to women and society,” he says. No more than ten people are present listening to him. Some laugh at the scene. Others are annoyed and interject, raising their voices to defend straight peoples’ sexual freedom.

Despite the small size of the speaker’s live audience, around 330 people follow his speech online on a gaming platform called Kick, as it’s live-streamed by 32-year-old Shako Mako. While filming, Mako says that this is the moment her 15,000 followers are most eager to see.

Shako is one of many live-streamers who visit the Speakers’ Corner on the north-east edge of Hyde Park in London each Sunday. This historic space, known as the oldest living free speech platform in the world, is currently a hotspot for digital content creators.

Located near Marble Arch, Speakers’ Corner stands in the same place that convicts would deliver their dying speech before being taken to Tyburn Gallows, where public hangings took place between 1196 and 1783. In 1866, it became a forum for wider political discourse after people marching to support the Reform League used it as a platform to campaign for universal manhood suffrage.

“Speakers’ Corner has always been a space for people who don’t get their voices heard in the mainstream media, to go there to try and get their voices heard,” says John Roberts, professor in sociology and communications at Brunel University London. According to him, this is one reason it’s still active today. “People used to gather there to see people executed, but also turning up to see those institutions that are very critical of the government,” he explains.

The Parks Regulation Act of 1872 frmalised the existence of Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park. However, Roberts notes that while the space is regarded as a “powerful symbol of the arrival

of liberal democracy in the UK, free speech has never legally existed in that space”.

Nevertheless, every Sunday since the Act, a crowd of speakers gathers between late morning and afternoon to spread their messages and ideas to passers-by and tourists, whether they are interested in hearing them or not.

As a barometer of the last two centuries of political and social change, Speakers’ Corner has had speakers such as Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, and George Orwell. It was also the birthplace of the suffragettes’ ‘Votes for Women’ campaign.

Nowadays, in Mako’s words, it is much more of a “content corner”. “People come here to film and photograph the speakers who come to say random things. As a content creator, I feel this is my place,” she says. Others, however, still retain the original tradition of listening to the speakers in person without worrying about content.

Mako has attended Speakers’ Corner every Sunday for at least three years. A year ago, she started doing live-streams there and sometimes

12

spends up to seven hours wandering among the speakers and hecklers. She has become familiar with the regulars.

The man who defends the sterilisation of heterosexuals is her favourite. “He says absurd things, but seriously, and people believe him,” she laughs. At this point, she’s already been live-streaming on her mobile phone for over four hours. “I stay here until the battery runs out,” she says.

Next to her, a man stands next to a mobile tripod containing a live-streaming mobile phone, a GoPro camera, and a directional microphone. He refuses to state his identity and age without explaining why, and prefers to be identified by his YouTube channel, Hafez Reflects, which has 1,500 subscribers and gets around 300 views per video.

Hafez has been going to Speakers’ Corner since 2018 to watch the speeches of far-right activist Tommy Robinson, but it was the diversity of conversation that roped him in for good. “This place becomes very addictive

because it’s only one day a week,” he says. He especially enjoys how he can start a conversation with someone and return to it later. “If you don’t finish it, you return next week,” he explains.

He started doing his YouTube lives at least twice a month around a year ago, targeting viewers overseas, especially in the United States. Now, it’s a regular thing:

“I do a live because a lot of my audience loves it. This is like their Sunday thing now. They complain when I don’t come.”

As he’s being watched by 21 people, he’s even wary of stepping away from the action for an interview. “Nothing is happening, so it’s boring for them,” he says.

However, not everyone with a video camera at Speakers’ Corner is there for entertainment. Some are there to film organisations and speakers, as is the case with 34-year-old cinematographer Gary Blake who has been filming the speeches of an Islamic organisation there for eight years.

For him, even though he can’t contribute, Speakers’ Corner is simultaneously exciting and frustrating. “You learn a lot from others. But some things said are offensive, and we can’t do anything about it because this is a place of freedom of speech,” he says.

Despite this feeling, the 1872 Act establishes rules for being at Speakers’ Corner, and police officers are often seen at the crowd’s edges. When the debate heats up, they get closer.

However, those at Speakers’ Corner aren’t looking for a fight. Here, unlike in the digital world, exposure to public scrutiny directly impacts how speakers and hecklers fuel speeches and responses. They all seem to be doing their best to ensure Speakers’ Corner will survive more centuries to come.

“A social movement that’s just online will be quite limited. These spaces are important to reclaim public areas for the commons and democracy,” concludes Professor Roberts.

Sunday in May, 2024, at Speakers’ Corner

CIVIC ACTION 13

Alice de Souza

Shako Mako

Hafez Reflects

The elephant in the room

Britain’s two main parties are silent about

Brexit

as the country heads into a general election

Calum Taylor

It’s been almost eight years since the 2016 EU referendum. But for many young Brits, it’s still an unresolved issue.

Cecilia Jastrzembska, president of the Young European Movement, is trying to change this.

“We managed to get national coverage,” she says, describing her organisation’s recent campaign pushing for the UK to rejoin the EU-backed student exchange programme, Erasmus+.

“We worked with the British Council,” she explains, “who then made some recommendations to the European Commission, and then they, quite to our surprise, actually kind of accepted them. That was very exciting. We launched a petition

that got 40,000 signatures.”

Soon after, the EU proposed a youth mobility scheme with the UK. This would allow UK and EU citizens under 30 to live and work in either area without visas.

“Another civil war over membership of the EU is the last thing they want”

After all of this, however, the UK’s two main political parties gave the same response:

“They flatly shut it down,” says Jastrzembska with frustration.

A new generation of voters have come of age in the UK since 2016, having grown up in a period of British politics dominated by Brexit. The Conservatives won the 2019 general election with the slogan “Get Brexit Done” emblazoned across everything from posters to tractors.

However, in 2024 with a new election campaign underway, the B-word is barely uttered – at least not by the major political parties. A consequence of this muffled silence is that voters are unsure how their future government may handle UK-EU relations.

If current polling trends continue, the Labour Party will win power. But their

Wikimedia Commons People’s

Vote March, October 2019

14

rejection of the youth mobility scheme, and their lack of engagement on the topic of Brexit more generally, makes it hard to predict how they would approach it in government.

“It’s unsurprising to be honest,” Jastrzembska concedes. “No party in its right mind is going to put that [closer UK alignment to the EU] in its manifesto, right? No. Because obviously then the whole election would be fought on that, and it would cause so much disunity and division.”

Jonty Bloom, a journalist who has reported extensively on Europe, explains it another way: “Brexit is very boring to most of the voters who are fed up with hearing about it. They want to move on and another civil war over membership of the EU is the last thing they want. Fair enough.”

However, with the only parties likely to form a government shying away from the topic of Brexit, voters concerned about it (many of them young or first-time voters) are forced into a difficult position.

Annette Dittert, a senior German broadcaster based in the UK, is frustrated at how Labour and the UK media reacted to the youth mobility proposal.

“Labour are obviously far less ideologally bound to Brexit”

Her only advice to young people is to vote. “Apathy will not help your case. That is the biggest problem with young people. The apathy is immense and Labour does not inspire.”

For many, including Jastrzembska, Labour’s response to the youth mobility proposal highlights how little they wish to reopen Brexit discussions. The last time a general election was fought over Brexit, they lost 60 seats.

“I personally would rather they at

least entertain the idea [of the scheme],” Jastrzembska says. “But I do understand this as a strategic move rather than a complete dismissal.

“Of course, I’m not in Keir Starmer’s head, so I don’t know if he would be completely opposed to it. But from an external perspective, it wouldn’t make sense as a party that’s trying to get elected, especially after so long out of power.”

While Brexit is important for many young voters, it is not their only priority either.

“For young people,” Jastrzembska explains, “there’s a cost-of-living crisis in the UK. There’s a rental crisis and a housing crisis. There’s an energy crisis – there’s a lot of crises.”

She believes that Britain’s relationship with the EU will move up the agenda once young people have achieved career mobility and financial stability.

What is clear is that eight years on from the 2016 referendum, many first-time voters find themselves unable to use their vote to

voice their feelings about Brexit.

Bloom says that the current election campaign is forcing “the young and proEuropean majority in a bind, because neither party which might form a government is paying them any attention at all”.

“Their only solace is that Labour are obviously far less ideologically bound to Brexit, do not lie about it being a great success and have made it clear that they would do it better,” he continues. “Which makes them the far better option for pro-EU voters.”

It will be clear only after election day whether this strategy pays off.

Young pro-EU campaigners like Jastrzembska show few signs of giving up. Despite the current state of play, she remains hopeful. “Labour has said ‘We have no plans right now.’ That doesn’t mean there are no plans.

“If there is enough political appetite, which we [the Young European Movement] have demonstrated there is – because it’s a win-win – then there is a road to possible reintegration.”

Gary Kmight Wikimedia Commons People’s Vote March, October 2019 CIVIC ACTION 15

Phoebe Plummer does not look like someone found guilty in a landmark anti-protest trial, as they scutter around, dishing out snacks, hugs, and cups of tea at the weekly Just Stop Oil vegan soup night.

“As a 22-year-old, I didn't really think I'd be preparing for my third time in prison,” they say. “But I know that fundamentally, the way in which I've acted is the morally right thing to be doing.”

The anti-capitalist was convicted in May alongside two other Just Stop Oil campaigners for delaying traffic during a slow march for the climate in November. The trio, due to be sentenced in July, could spend up to a year in prison.

“As a 22-year-old, I didn’t really think I’d be preparing for my third time in prison”

“I don't want to be away from the people I love,” Plummer says. Their partner, a fellow activist, likewise faces the prospect of a prison term. “It's a very weird relationship anxiety to have, [worrying that] we're constantly going to miss each other,” they say.

Like Plummer, thousands of young people

A summer

A new protest group for young people

Abdi Abdalla

across the world are turning away from electoral politics to direct action protesting movements like Just Stop Oil. According to the group’s own records, 2,039 people have taken action with the group, and 138 have spent time in jail. Just Stop Oil’s central demand is that the British government end all oil licensing and investment.

According to David Bailey, associate professor in politics at the University of Birmingham, this upsurge in extraparliamentary politics in Britain can be traced back to the 2010 student protests against a rise in university fees. In the context of “economic insecurity, ecological crisis, war, and a growing sense of hopelessness,” Bailey says it is “unsurprising that there is a heightened level of social dissent and protest".

Just Stop Oil is now part of the “Umbrella” coalition of different protest groups whose stated aim is to “bring about a revolution”. One fellow coalition member

is Youth Demand, a group that made headlines in April when its activists daubed the Ministry of Defence in red paint.

Their campaign has two demands of the UK government: ending all new oil and gas drilling, and an arms embargo on Israel.

At a recent talk for newcomers in King's Cross, Youth Demand organisers spoke to an audience of around 40 about the need for civil disobedience, ahead of a planned campaign of direct action in the summer.

As is made clear by the speakers, a willingness to get arrested is a key trait for anyone hoping to take action with the group. Youth Demand was inspired by the Children’s March in Alabama in 1963, when hundreds of Black schoolchildren were arrested whilst demonstrating for civil rights.

In late May, the group held a session at a hall in Waterloo, where the participants were introduced to the philosophy of nonviolence. These sessions are

16

Youth Demand march on Waterloo Bridge

Abdi

Abdalla

plans a summer of mass disruption of protest

compulsory for those who sign up for arrestable actions. They are taken through a simulation of disruptive action on a busy road and taught how to de-escalate tense encounters.

One of the instructors made it clear that emergency vehicles must be allowed through blockades, and cites a Freedom of Information request disproving the accusation that Just Stop Oil has obstructed ambulances – a charge levelled at the group by critics.

Youth Demand’s politics - like Just Stop Oil’s - are decidedly international. Speakers at both groups’ weekly meetings paint a picture of a world divided into a privileged north and an exploited south, where billions face a “structural genocide” caused by the north’s fossil-fuelled mode of living.

When the wave of student rebellions in support of Gaza arrived from the United States in early May, students at University College London were among the first to occupy their campuses. Two days after the first tents were erected, Youth Demand cofounder Sam Holland spoke to the crowd gathered at the gates, pledging to shut down the capital city in solidarity with Palestine.

“The endgame is causing mass material disruption”

Horrified at the scale of the climate crisis, the 22-year-old Bristolian quit university in November 2022 to dedicate his time to activism. He has subsequently been arrested multiple times with Just Stop Oil. “There are more important things than career or income,” he says.

Holland acknowledges that governments “don’t care about symbolic action” like throwing soup at paintings – a tactic used by climate groups to gain public attention.

“The endgame is causing mass material disruption,” he says. This involves “blocking the roads, blocking infrastructure, train stations, airports– strikes and general strikes.”

Holland accepts that fear deters some young people from direct action. But he insists that “if you want to change regimes, if you want to change policy, you have to get arrested. You have to break the law. You have to cause disruption.”

Abdi

Abdalla

Police watch as protestors occupy Waterloo Bridge

Abdi

Abdalla

Police watch as protestors occupy Waterloo Bridge

CIVIC ACTION 17

Young, bold and breaking the mold

Youthful British politicians face significant challenges due to their age

Dom Plaskota

Starting out in politics at the tender age of 18 has been a baptism of fire for Liberal Democrat councillor Tom Penketh.

Penketh, a funeral director, felt that he could represent his community well after he won a seat on Shaw and Crompton Parish Council, near Manchester, last year. It wasn’t his first venture into politics. By the time he was sitting his A-Level exams and campaigning for elections, the buoyant, mop-haired youngster had already been a member of the Liberal Democrat Party for two years.

His natural optimism, however, has been tempered by his experience in his first year as an elected representative. Other councillors sometimes speak down to him and ignore what he says. When people do listen, he feels that he faces more intense scrutiny, simply because of his age.

“I had to work a lot harder and be more impressive than others”

“Opposition’s healthy,” he says. “You’re going to have disagreements. You’re not going to want the same thing or to get it done the same way. But then it gets personal.”

While some people prefer their politicians to have had plenty of life experience, the current impasse in the US, with two unpopular elderly candidates battling to be president, shows that there is a limit.

As one of the UK’s youngest councillors, Penketh is one of the country’s few young politicians. Just 3 per cent of MPs elected in the last general election in 2019 were aged between 18 to 29, even though young adults make up almost a fifth of the UK’s population.

This lack of representation contributes to low turnout among young voters, Penketh claims. At the last general election, the

18-24 and 25-34 voting groups had almost 25 per cent lower turnout than voters aged 65 and over.

Penketh also thinks young people are deterred from going into politics after seeing how young politicians are mistreated. Mhairi Black, who was the youngest MP when she was elected at 20 in 2015, has blamed Westminster’s toxic environment for her decision not to stand in the upcoming general election, although some suggest she stepped aside because of the high likelihood she could lose her seat.

Young politicians are also less likely to be financially independent than their older colleagues, so they feel the financial burdens of a political career more acutely. While MPs are paid £91,346 annually, councillors receive limited compensation.

According to the Local Government Association, the average councillor spends 22 hours a week on council business and receives around £7,000 a year.

Ria Patel, a 22-year-old Green Party Councillor from Croydon Council, finds this difficult, even as someone from a middle-class background.

“I’m quite lucky that I was able to move back home. I live with my mum, so I don’t currently have to pay rent,” they say, chuckling. “I would love to move back out, but that’s a work in progress.”

Even when young politicians progress they encounter obstacles, says Emma Roddick, a Member of Scottish Parliament (MSP) for the Scottish Nationalist Party.

Roddick was a councillor from 2019 before she was elected as MSP for the Highlands and Islands region at 23, making her the youngest MSP at that time. Two years later, she was appointed Minister for Equalities, Migration and Refugees, where she remained until last month when the First Minister’s resignation triggered a reshuffle.

“I had to work a lot harder and be more impressive than

others straight away just to be considered competent,” she says.

Despite her rapid climb, her colleagues still talk over her and answer for her, she claims.

“They seem to think they’re doing me a favour. It gets very annoying!”

Roddick also feels pressure to constantly address youth issues. While it is something that she is passionate about, it leaves less time to represent young people in other policy debates, including on housing.

“Yes, it’s great to platform young voices as young voices, but make sure they still have the time to attend their work and prepare to be around the boardroom table with their professional peers and feed into all these other discussions.”

Penketh says that despite these challenges, he’s glad to be a politician. His excitement is palpable.

“I want to do it more than ever,” he says. “When I get on to the Borough Council, I’ll have a louder voice for a bigger area. Maybe I’ll even be an MP one day.”

Courtesy of Tom Penketh

Courtesy of Tom Penketh

18

Tom Penketh, young councillor

An end to the two-horse race?

How proportional representation could get more voters to the polls

Lilian Crastan

Ella Eagle Davis, 22, is unimpressed by the recent direction of UK politics.

“Watching it devolve into something which I think is the furthest away from representing me or my interests was really disheartening,” she says.

With a general election called for 4 July, she felt unrepresented by all of the parties that stood a chance of holding office. “It scared me, and it angered me and I thought, okay, right, I need to do something about this.” She became a volunteer researcher for Make Votes Matter, an organisation that advocates for replacing the UK’s first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system with proportional representation (PR).

Because of the way FPTP advantages larger parties, British politics has been dominated by the Conservative and Labour parties for the past century. Under FPTP, the candidate who wins the most votes in a constituency is awarded the seat, irrespective of whether they achieve a majority. This tends to

penalise smaller parties, often resulting in a distribution of seats in Parliament that does not necessarily reflect the national vote share.

Robert Johns, professor of politics at the University of Southampton, thinks the current electoral system does not accurately represent the country’s preferences. “It did a pretty good job about 60 years ago,” he says.

According to a 2022 study by the National Centre for Social Research, Britons’ support for electoral reform has grown. 51 per cent now favour introducing PR for elections to the House of Commons, which would fundamentally change how votes translate into seats in Parliament. Under PR, seats are allocated based on the percentage of votes each party receives, more accurately reflecting the vote share.

According to a 2019 YouGov survey, nearly 40 per cent of people aged 18 to 24 believe their vote does not significantly impact the general election results. Other polling has shown that in 2019, voter turnout ranged from 47 per cent among 18- to 24-year-olds to 74 per cent among those over 65.

Johns attributes the higher turnout of the older generation to a sense of duty that is lacking in younger voters. When deciding whether to vote, according to Johns, young people are more likely to ask themselves questions, such as “‘how likely is my vote to make a difference?’ We know that when they

answer that question about first-past-the-post, they’d give a more negative response.”

If the youngest don’t feel represented by the parties that are likely to win the elections under FPTP, they might decide not to vote at all, as Eagle explains:

“Young people are looking to what should be role models for them. And they see [politicians] don’t speak like them, they don’t act like them. They don’t have any sort of life experiences that resonate with them and so what’s the point in voting, when those are the sort of people that are going to get in?”

“It angered me and I thought, okay, right, I need to do something about this”

It may however be a while before the UK changes its electoral system. As Johns points out, “political culture takes a long time to change”.

But both Johns and Eagle think PR could make the Parliament more representative and Britons more eager to go to the ballot.

“Under PR,” explains Eagle, “you will have a system in which compromise takes centre stage, which will work to find a solution for the people that are represented by it, which hopefully under proportional representation is the majority.”

Yong

Yaopey

CIVIC ACTION 19

UK Parliament

Votes for kids

How giving children the vote could

reinvigorate democracy

Eliana Nunes

Until recently, there was a myth that young people were apathetic,” says Daniel Meister, communications manager at The National Youth Council of Ireland (NYCI), “[but] the independence referendum in Scotland and the marriage equality referendum in Ireland scotched that”.

This June, Belgian and German 16- and 17-year-olds cast their ballots in the European parliamentary elections for the first time, joining Austrian, Scottish, and Maltese teens. But whilst campaigns advocating for a lower voting age have been gaining momentum since the 1990s, 16-year-olds in 22 EU member states, including Ireland, still lack voting rights.

“People start their lives out being given the idea that their voices count”

In 2022, a bill to lower the voting age in Ireland failed to make it past the country’s senate. Meister points out that had it been passed, around 130,000 Irish 16- and 17-yearolds would have been able to participate in this year’s European elections. “This was a missed opportunity to strengthen Irish democracy,” he says.

Campaigners argue that lowering the voting age could help shore up support for the idea of democracy. Polls, including a recent Ipsos KnowledgePanel survey, consistently show that support for democracy across European countries is at an all-time low.

DO KIDS WANT TO BE COUNTED IN?

“Secondary school kids deserve to be taken more seriously by society,” says Eva, a 12-yearold from Greece. “Plus, being able to vote about the causes we care deeply about would teach us the importance of actively participating in our communities.”

Eva is especially keen to vote for Greece’s next prime minister but will miss the chance in the 2027 national elections, as Greece’s minimum voting age is 17. She will likely vote for the first time in the 2029 European elections, when

she will be 19.

Yet by 2029, national and international policies impacting Eva’s future will have already been determined by decision-makers significantly older than her. Greece stands out as having one of Europe’s largest ageing populations: over-65s make up 23 per cent of the population, according to a recent Eurostat report.

Athena, 13, takes a more cautious stance than Eva. “Since voting is a huge responsibility, 15 should be the minimum age to be able to vote,” she says, concerned that younger children are

“too easily influenced by parents and teachers”.

COUNT KIDS IN

Advocates for lowering the voting age to 16, including Meister from the NYCI, say that doing so is a matter of consistency. In most EU member states, 16-year-olds are given the responsibilities of entering the workforce, paying taxes, and leaving school, so their inclusion in political life makes sense.

But whilst some European countries are considering giving 16-year-olds the vote, some

20

Kids playing in the park

Eliana Nunes

want to go even further: extending voting rights to young teens, children, and even babies.

For Professor John Wall, a childhood studies scholar at Rutgers University Camden and author of Give Children the Vote: On Democratizing Democracy, it makes the most sense for voting to be an ageless birth-right.

“People would start their lives out being given the idea that their voices count whoever they are,” Wall argues.

“At the moment, we tell people for the first quarter of their lives that their voices don’t count, that they’re not capable of exercising decision-making,” he says, explaining that under 18s, who amount to around one quarter of the global population, are the largest disenfranchised group in the world.

In the absence of surveys asking kids what they think about voting – an irony not lost on Wall – there is some evidence to suggest that 16- and 17-year-olds are enthusiastic voters when given the chance.

In Austria, where the voting age has been 16 since 2007, national electoral lists consistently indicate a higher voter turnout among 16- and 17-year-olds than among 18- and 21-year-olds.

Broadening the franchise would revive democracy, Wall believes.

“Voting always changes whenever a new group gains the franchise. It looked very different when it was only white or landowning men who had the vote,” he says.

Europe’s children might prioritise voting on environmental and social justice issues, much

like child activists and young adult Europeans. In a recent survey by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), European under29s named the climate crisis as their biggest concern, whereas older generations said they were more concerned about immigration.

LEAVE KIDS OUT OF IT

While the idea of 16-year-olds voting may be controversial, it’s hardly radical. But many might find the idea of young kids having a say in politics ludicrous. Images of a two-year-old scribbling on a ballot card spring to mind.

To address these challenges, Wall proposes a proxy voting system where parents or guardians cast votes on behalf of young children and babies. Meanwhile, Cambridge University politics professor David Runciman suggests the age of six as a tentative threshold.

But Tatiana Gorney, a child psychologist for almost two decades, is adamant that children under 16 are not equipped with the competence and life experiences needed for voting.

“To participate in voting processes, I believe a person needs to have a level of cognitive and emotional development,” Gorney argues.

“Governments should be obliged to include children’s opinions in their policies, but this does not mean children should vote,” she says. “Children under 16 have not yet developed mature ‘hot cognition’; reasoning that is emotionally

regulated. This means that their decisions may be influenced by peer pressure.”

Wall has heard such arguments countless times. Sighing, he reiterates that as adult voters, we are not tested for competence and that, in this post-truth era, we are often swayed by emotions rather than thorough political analysis.

The rise of authoritarianism is a threat to the EU: in the run-up to elections, EU campaigning stressed younger generations’ responsibility to vote “to protect democracy”.

For youth suffrage campaigners, lowering the voting age – whether to 16 or 0 – could be the solution.

CIVIC ACTION 21

Belga

Global Climate Strike, 2019 Gary Knight

Courtesy of Professor John

An election in the fog of war

How the Israel-Hamas war will sway Muslim and Jewish voters this July

Justine Noble

Sumaya, a 26-year old technology sector employee, has always voted Labour. At the forthcoming general election next month, however, she might abstain for the first time, because of the party’s attitude towards the war in Gaza.

For Sumaya, things changed after the October 7 Hamas attack when Labour leader Keir Starmer repeatedly stated that Israel has the right to defend itself regarding its military operations in the Gaza Strip. Since then, she believes the party hasn’t done nearly enough to hold Israel accountable for the suffering it has inflicted on Palestinian civilians over the past seven months. Her views, she says, are far from unique in her Muslim community in west London.

“I think the Labour party has completely alienated its Muslim voters,” she says.

According to national polls, the key issues in the UK’s general election are the economy, immigration, and the struggling National

Health Service. For many British Muslims and Jews, though, the way Labour and the Conservatives have responded to the ongoing Israel-Hamas war will ultimately dictate for whom they decide to vote.

In February, a poll by Survation and the Labour Muslim Network found that 86 per cent of Muslims voters backed Labour in the previous election. Only 43 per cent said they would vote for them again, and 23 per cent were undecided.

This drop in Muslim support for Labour has swung recent electoral outcomes. In Rochdale, a historically Labour-leaning town where about 30 per cent of inhabitants are Muslim, George Galloway from the British Workers’ Party won a by-election held in February.

The campaign of the divisive politician was dominated by a strong pro-Palestine stance and unsparing criticism of Labour’s position on Gaza. Two weeks prior to the election, when Labour proposed an amendment to a motion

calling for an immediate ceasefire, Galloway remarked that the names of the party’s MPs were “dripping in blood”.

In neighbouring Oldham, where around 24 per cent of people are Muslim, Labour lost control of the council in the May local elections after ceding six seats to independents. While local Labour leader Arooj Shah denied that Starmer’s position on the crisis in Gaza was to blame, the party’s national campaign coordinator acknowledged that the party’s response to the war was “a factor”.

Ahead of the general election, campaign group The Muslim Vote is urging Muslims to keep Gaza in mind, especially in constituencies where they could shake up results, such as Bethnal Green and Bow, Birmingham Ladywood, and Leicester South. They are set to release a list of candidates they endorse on foreign policy, the NHS, and education.

According to Dr Andrew Barclay, a research associate in the Department of Social Policy at the University of Oxford, the political relevance

22

Wikimedia Commons

of overseas conflicts to British Muslims is nothing new.

“The Labour party has completely alienated its Muslim voters”

“The only real sort of wavering that we’ve seen historically in Muslim support for the Labour party was related to foreign policy,” he says. “So following the Iraq War, and following the war in Afghanistan, there was a fairly measurable dip in how well candidates did in constituencies with large Muslim populations, but that seemed to revert back to tide pretty quickly after that, as recently as 2010.”

Dr Barclay believes this pattern is probably due to “a feeling that major political parties

Pro-Palestine protest in London, 2024

and the British government are happy to not support Muslims around the world”.

The support for Labour is not waning only in the Muslim community, but in the Jewish diaspora too.

For 22-year-old Hannah Silverman from Elstree in Hertfordshire, where around 36 per cent of residents share her Jewish identity, circumstances at home are influencing how she’s planning to vote.

In 2023, the Community Security Trust, a charity that offers security advice to the UK’s Jewish Community, documented a record number of antisemitic incidents, up 147 per cent from the year before. Approximately twothirds of the total occurred after the Hamas-led attack on Israel on 7 October.

In October 2020, a report by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) concluded that Labour was responsible for “unlawful” acts of discrimination over antisemitism under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. The watchdog highlighted three

violations of the Equality Act: political interference in antisemitism complaints, failure to provide sufficient training to those handling these complaints, and harassment.

While Silverman has been wary of the Labour party’s reputation for antisemitism since the EHRC’s report, rising anti-Jewish hate since 7 October has made voting for the party a no-go:

“As a person who’s more left-leaning, I won’t be voting Labour sadly because I just can’t for my own safety.”

Silverman isn’t alone. Dr Barclay explains that “evidence suggests that most British Jews feel levels of this kind of threat of hostility from the political left, whereas previously they probably would have felt it more from the political right”.

“You do see big spikes in domestic antisemitism [against] some Jewish diaspora whenever Israel is involved in some sort of conflict, so it raises this salience of antisemitism in Britain whenever these things happen,” he adds.

However, how Muslim and Jewish communities relate the Israel-Hamas war to domestic politics is not clear-cut. A decline in support for the Tories in Silverman’s home borough of Hertsmere in the May 2023 local elections indicated that Starmer’s pledges to eradicate antisemitism in his party may have struck a chord with Jewish voters.

“I won’t be voting Labour sadly because I just can’t for my own safety”

Haris, a 22-year-old software engineer from Small Heath; an overwhelmingly Muslim area of Birmingham, is also unconvinced that Labour has fully lost its Muslim support base:

“They know what’s on the other side, and they know the other people that probably win are the Tories, and they don’t want a Tory government.”

Courtesy of Sumaya

Pro-Palestine graffiti

CIVIC ACTION 23

Courtesy of Sumaya

People vs power

Jamie Onslow

29 25

Protesters in Peckham, south London blocked a coach that was attempting to transfer asylum seekers to the Bibby Stockholm barge, Dorset on 2 May. They clashed with the police, with 45 arrested. The protest came as the Home Office prepared to deport 5,700 asylum seekers to Rwanda this year.

International

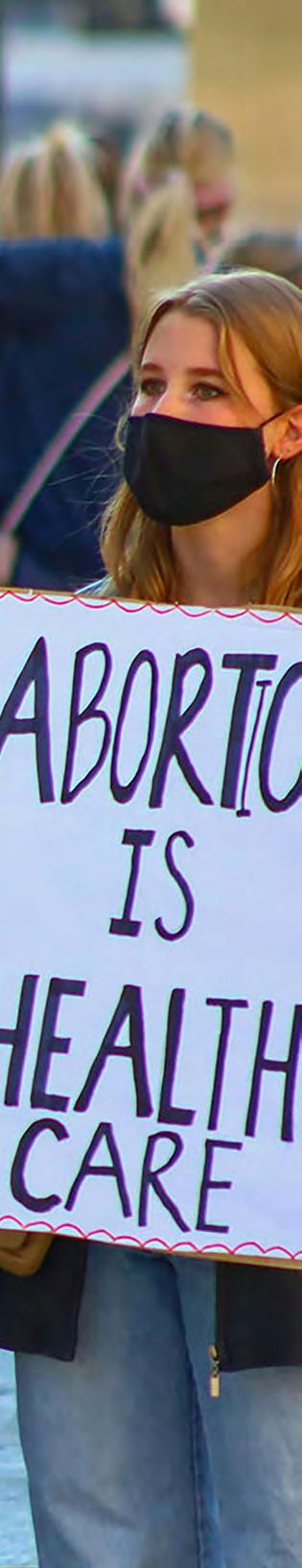

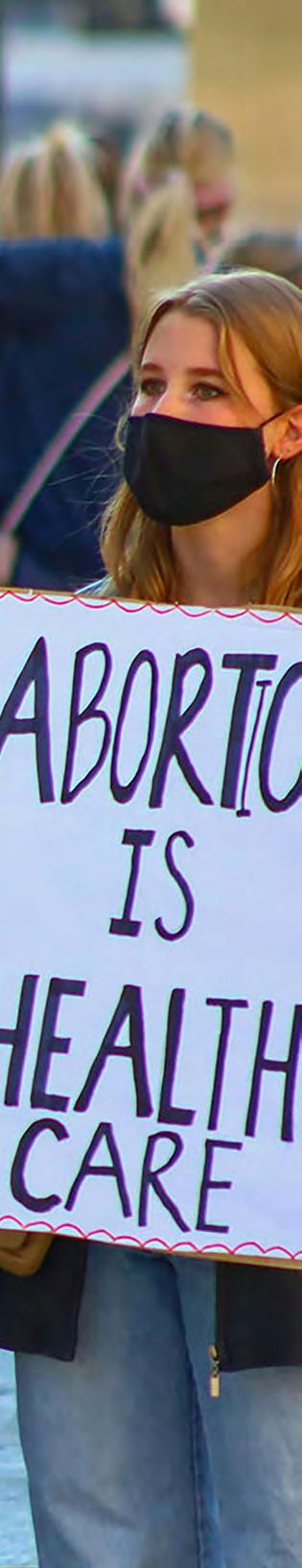

At anti-abortion protests in the US, protestors brandish placards with slogans like “As a former foetus, I oppose abortion,” “Equally human = born and preborn” and “I vote pro-life first”. As emotive expressions of deeply-rooted opinions, these calls to action show that abortion is one of the key issues ahead of the presidential election in November.

In 2022 the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, ending the constitutional right to abortion. Following the decision, 21 out of America’s 50 states have banned or restricted abortion before the 12-week standard set by the landmark 1973 case.

Nevertheless, polling shows that support for increased access to abortion has broadly increased in recent years – to the disappointment of Michel Dykstra, a prolife advocate and volunteer at PRC Grand Rapids, a clinic for unplanned pregnancy support in Michigan.

“Abortion does concern someone. He/she just doesn’t have a voice yet”

“It’s deeply sad, actually. We have become self-centred: ‘I do what I want, and it doesn’t concern you.’ But abortion does concern someone else. He or she just doesn’t have a voice yet,” says Dyktsra.

Claire McKinney, an assistant professor at the College of William & Mary who studies the politics of reproduction, sees a pragmatic reason for the switch in public opinion following the overturning of Roe v. Wade in 2022.

She explains that since the ruling and subsequent abortion bans, even women who weren’t pregnant have been unable to access certain medicine that could create foetal harm, leading some to rethink their support for anti-abortion laws.

As this support wanes, pro-life advocates are looking to America’s history for assistance.

They have called on the federal government to fully implement the Comstock

How abortion is shaping Bodies on

Lara Lovric

Act, an 1873 law that whilst still on the statute books, is not enforced by authorities. The act prohibits sending or receiving any materials designed for “the prevention of conception or procuring of abortion”. If enforced, it would sharply restrict access to abortion nationally.

“If you really believe that abortion is murder, then if there was a good law on the books, you bring it back. It’s a kind of moral absolutism where it just overrides

all other considerations,” says Paul Goren, a professor of political science at the University of Minnesota.

In response, pro-choice Democrat activists are gathering signatures to ensure that their party’s nominees have pledged to protect abortion rights. Activists have also managed to get abortion rights put on election ballots in several states. In Florida, for example, voters will decide whether the

Women protesting for women’s health protection act 28

Manny Becerra

the ballot

the US election

right to abortion should be enshrined in the state constitution.

In the 2022 midterm elections, that seemed to work. Abortion turned out to be an important voting motivator and an effective blocker of the forecasted “red wave” in which Republicans were set to gain a significant number of seats.

“It’s a moral absolutism where it overrides all other considerations”

According to KFF’s midterm exit polls analysis, 38 per cent of voters said that the overturning of Roe v. Wade had a major impact on their decision to vote in the midterms, while 47 per cent said that it had a major impact on which candidates

they supported.

This election season, the Democrats will be playing the pro-choice card heavily.

“They know they can [appeal] to the liberals who think conservatives are trying to take away a woman’s rights over her own body,” says Dykstra.

The Republicans will have to be more tactical about how they frame an issue that has become a liability. Even though legal access to abortion is not a priority for the electorate, as it falls behind concerns about economy, healthcare, illegal immigration, and gun violence, it could cost the Republican Party votes.

“When Trump is signalling that he might be open to reviving laws like the Comstock Act, that’s a wink to his base that he’s on the side of the religious right. If he makes that a prominent part of his general election campaign, he’s going to face a lot of pushback,” concludes Goren.

The two candidates in the election will likely take different approaches to abortion rights if elected.

“If Biden is re-elected, he’ll do everything within his power to make sure that the government is rhetorically committed to increasing access to reproductive technologies for women,” says Goren.

The right approach for Donald Trump, on the other hand, is less clear. Although he declared himself “the most pro-life president” and has boasted of playing a central role in the overturning of Roe v. Wade, he has been downplaying the divisiveness of the issue of abortion in his campaign and will likely keep diverting attention to other matters.

“I can see [Trump and the Republicans] saying: ‘Well, the Supreme Court decided and it’s up to the states, let’s now change the subject to immigration or some other issue on which most of us agree,’” Goren chuckles.

INTERNATIONAL 29

Gayatri Malhotra

Women’s March for Abortion Rights in Arizona, USA

Women’s March for Abortion Rights in Washington D.C.

Aubrey Thrower

Queer Texans and the race to the White House

Despite increasingly restrictive state legislation, changing demographics inspire hope

Cahal McAuley

The race for the presidency between Joe Biden and Donald Trump is the rematch that few Americans wished to see.

Their combined age of 158-years-old and a slide towards gerontocracy in the United States has left many young voters disillusioned, but perhaps none more so than queer and trans youth in Republican-led states like Texas. These individuals have seen a huge increase in laws targeting their rights at state level, despite the

fact that a Democrat sits in the Oval Office.

“Regardless of who wins, people will always have something to say about trans people because our identities are constantly politicised,” said Rowan Hawke, a trans man from Houston, Texas.

The frustrations of Hawke, sitting with a pride flag hung behind him, are shared by many queer and trans Texans following the adjournment of the 88th state legislature which

passed a raft of LGBTQIA+ laws last year.

“As much as Texas wants to pretend that queer and trans kids don’t exist, they do,” he says.

“When you have bills that are specifically targeting disenfranchised groups of people, particularly the youth who already don’t have a lot of legal autonomy, [those people are] being shown by the government that they’re not welcome,” he adds.

Protestors outside the US Supreme Court

30

Ted Eytan