56 ///

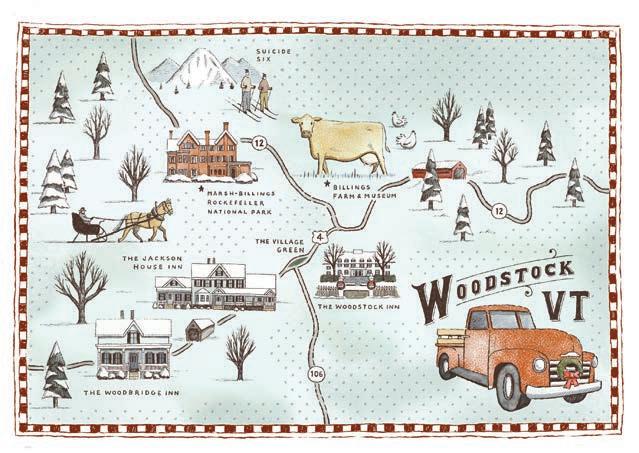

Looking for the ultimate holiday experience? Two towns in the Green Mountain State—Manchester and Woodstock—deliver Yuletide festivities for all ages. by Bill

Scheller74 /// A

Holiday traditions may vary, but one thing is universal: the joy and warmth of family and friends coming together. by Naomi Shulman

78 /// The Natural

Meet New Hampshire’s Beatrice Trum Hunter, a pioneer of America’s healthy eating and environmental advocacy movements. by Edie Clark

84 /// Angels

Yankee celebrates ordinary New Englanders who are making an extraordinary difference in others’ lives. by Ian Aldrich

88 ///

The humble oyster just may be the key to rebuilding New England’s coastal ecosystems. by Michael Sanders

The Trappist monks of Spencer, Mass., devote their lives to work and prayer in a community of kindred souls. text by Justin Shatwell, photographs by the Brothers of St. Joseph’s Abbey

p. 56).

Journey to Cuba in 2016 with Pearl Seas Cruises on an 11-day immersive people to people experience focused on the rich history, heritage, and contemporary life of the Cuban people. The brand new 210-passenger luxury

Pearl Mist allows access to more of Cuba’s ports and regions, while providing a relaxed means to interact with Cubans and explore the rich fabric of Cuban culture. These cultural voyages are subject to final approval by the U.S. and Cuban governments.

Cruising the Intracoastal Waterway with American Cruise Lines is an exploration of Southern grace. Our 8-day cruises allow you to experience Savannah, Charleston, Jekyll Island, and other locations while you delight in the comfort of our new, small ships. Request a free brochure today and begin planning your perfect cruise.

World's Leading Small Ships Cruise Line

26 /// Merry and Bright

At Christmas, designer Kristin Nicholas’s antique Cape in western Massachusetts becomes a holiday wonderland of shimmering color and sparkling light. by Julia Quinn-Szcesuil

36 /// House for Sale

Steeped in history: Yankee tours a 375-year-old house on Old King’s Highway in Barnstable, Massachusetts. by Guest Moseyer Tim Clark

44 /// Could You Live Here?

The town of your dreams: Salisbury, Connecticut, in the rolling Litchfield Hills, home to a vibrant and welcoming community spirit. by Annie Graves

50 /// The Best 5

Yuletide magic comes alive as New England towns don their finest illuminations. by Kim Knox Beckius

52 /// Local Treasure

Channel your inner Patriot and join the rebellion at the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum. by Aimee Seavey

54 /// Out & About

Yankee ’s events calendar spotlights top holiday fairs and festivals across New England. compiled by Joe Bills

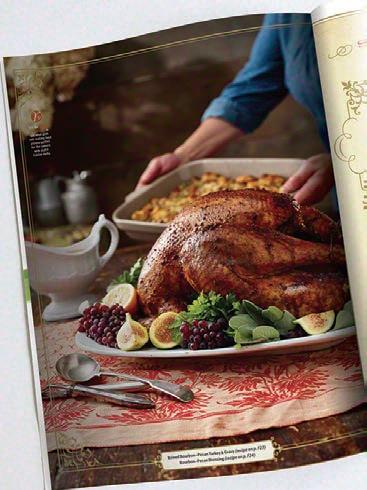

133 /// Yankee’s Special Holiday Cookbook

Flip this magazine to discover our third annual New England food awards, our 80th-anniversary holiday recipe collection, best apple pies, and more!

1121 Main St., P.O. Box 520, Dublin, NH 03444, 603-563-8111; editor@YankeeMagazine.com

EDITORIAL

EDITOR Mel Allen

ART DIRECTOR Lori Pedrick

MANAGING EDITOR Eileen T. Terrill

SENIOR LIFESTYLE EDITOR Amy Traverso

SENIOR EDITOR Ian Aldrich

PHOTO EDITOR Heather Marcus

ASSOCIATE EDITORS Joe Bills, Aimee Seavey

INTERNS Theresa Shea, Heather Tourgee

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Kim Knox Beckius, Annie Card, Edie Clark, Annie Graves, Ben Hewitt, Justin Shatwell, Ken Sheldon, Julia Shipley

CONTRIBUTING

PHOTOGRAPHERS Julie Bidwell, Kindra Clineff, Sara Gray, Corey Hendrickson, Joe Keller, Matt Kalinowski, Joel Laino, Jarrod McCabe, Michael Piazza, Heath Robbins, Kristin Teig, Carl Tremblay

PRODUCTION

PRODUCTION DIRECTORS David Ziarnowski, Susan Gross

SENIOR PRODUCTION ARTISTS Jennifer Freeman, Rachel Kipka

DIGITAL

VP NEW MEDIA & PRODUCTION Paul Belliveau Jr.

DIGITAL EDITOR Brenda Darroch

NEW MEDIA DESIGNERS Lou Eastman, Amy O’Brien

PROGRAMMING Reinvented Inc.

YANKEE PUBLISHING INC.

established 1935

PRESIDENT Jamie Trowbridge

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Judson D. Hale Sr.

VICE PRESIDENTS Paul Belliveau Jr., Jody Bugbee, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Sherin Pierce

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Ken Kraft

CORPORATE STAFF Mike Caron, Linda Clukay, Sandra Lepple, Nancy Pfuntner, Bill Price, Christine Tourgee

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

CHAIRMAN Judson D. Hale Sr.

VICE CHAIRMAN Tom Putnam

DIRECTORS Andrew Clurman, H. Hansell Germond, Daniel Hale, Judson D. Hale Jr., Joel Toner, Cor Trowbridge, Jamie Trowbridge

FOUNDERS

ROBB & BEATRIX SAGENDORPH

PUBLISHER Brook Holmberg

ADVERTISING: PRINT/DIGITAL

VICE PRESIDENT/SALES Judson D. Hale Jr.

SALES IN NEW ENGLAND

TRAVEL, NORTH

(NH North, VT, ME, NY) Kelly Moores

TRAVEL, SOUTH

(NH South, CT, RI, MA) Dean DeLuca

DIRECT RESPONSE Steven Hall

CLASSIFIED Bernie Gallagher, 203-263-7171

SALES OUTSIDE NEW ENGLAND

NATIONAL Susan Lyman, 646-221-4169, susan@selmarsolutions.com

CANADA Alex Kinninmont, Françoise Chalifour, Cynthia Jollymore, 416-363-1388

AD COORDINATOR Janet Grant

For advertising rates and information: 800-736-1100 x149 YankeeMagazine.com/adinfo

MARKETING

CONSUMER

MANAGERS Kate McPherson, Kathleen Rowe

ASSOCIATE Kirsten O’Connell

ADVERTISING

DIRECTOR Joely Fanning

ASSOCIATE Valerie Lithgow

COORDINATOR Christine Anderson

PUBLIC RELATIONS

BRAND MARKETING DIRECTOR Kate Hathaway Weeks

NEWSSTAND

VICE PRESIDENT Sherin Pierce

DIRECT SALES

MARKETING MANAGER Stacey Korpi

SALES ASSOCIATE Janice Edson

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICES

To subscribe, give a gift, or change your mailing address, or for other questions, please contact our Customer Service Department: online: YankeeMagazine.com/contact phone: 800-288-4284

mail: Yankee Magazine Customer Service

P.O. Box 422446 Palm Coast, FL 32142-2446

We occasionally make our mailing list available to advertisers whose offers we think may be of interest to subscribers. If you would prefer not to receive such offers, please contact us using one of the methods listed above.

Prized

80

Dear Reader,

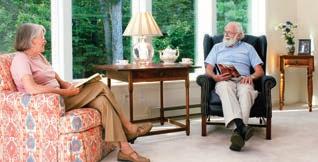

The drawing you see above is called In Our Time. I created this in honor of two of my dearest friends. After writing the poem, I worked with a quill pen and placed thousands of these dots, one at a time, to create this gift for someone who is very much part of my life.

Now, I have decided to offer In Our Time to those who share and value its sentiment. Each litho is numbered and signed by hand and precisely captures the detail of the drawing. As a wedding, anniversary or Christmas gift for your husband or wife or a particularly dear friend, I believe you will find it most appropriate.

Measuring 14" by 16", it is available either fully framed in a subtle copper tone with hand-cut mats: outside mat is medium beige and the inside mat is burgundy, at $135, or in the mats alone at $95. Please add $14.50 for insured shipping and packaging. Either way, your satisfaction is completely guaranteed.

My best wishes are with you.

The Art of Robert Sexton • P.O. Box 581 • Rutherford, CA 94573

All major credit cards are welcomed through our website. Visa or Mastercard for phone orders.

Phone (415) 989-1630 between 10 a.m.-6 P M PST, Monday through Saturday. Checks are welcomed; please include the title of the piece and a contact phone number on check. Or fax your order to 707-968-9000. Please allow up to 2 weeks for delivery.

*California residents- please include 8.0% tax

Please visit my Web site at www.robertsexton.com

“...And when we grow old I will find two chairs and set them close each sun-lit day, that you and I — in quiet joy— may rock the world away.”

nce I believed that the holidays meant rituals of obligation: a Thanksgiv ing feast, and then with barely a breath in between, an almost obsessive need to bestow gifts. When my sons were young, I filled secret places with toys and gadgets, even making one final sweep on Christmas Eve for that “needed” stocking surprise. I thought that that’s where the magic happened, with their eyes wide in the bedtime dark (you might even hear Santa’s sleigh gliding beneath the stars), then the quivering excitement at daybreak when they found the living room transformed by prettily wrapped presents. Presents that a few weeks later mostly waited askew in corners of the playroom, their shiny newness already worn off. On to other things.

Nigel Manley’s Christmas unfolds across hundreds of acres of balsam fir trees that he oversees at The Rocks Estate in Bethlehem, New Hampshire (“A Tree Grows in Bethlehem,” p. 18). He sees children bending low to harvest their special tree—the tree that soon will suffuse their home with the scent of a northern forest. Christmas arrives, too, in the sacred quiet of St. Joseph’s Abbey, in Spencer, Massachusetts, where Trappist monks live in contemplation, work, and worship ( “A Life That Is ‘Ordinary, Obscure, and Laborious,’” p. 66). While their famous jams have been joined now by their ales, their lives are still as distant from the box-store frenzy as if they existed on a separate earth.

This Yankee issue understands that the magic has always been about the gathering—and that the gathering happens around food. This is where we find the heart of the holidays, no matter which ones we celebrate, or when, as long as we’re with people we care about, passing around the platters. And it’s not about filling bellies—there are a lot of ways to do that—but about keeping our loved ones close. A student of mine in Bay Path University’s MFA writing program, Kathleen Bourque,

wrote recently about a memory: “My kitchen will not rid itself of the stench of boiled cabbage. But if I listen closely, I can again hear the Clancy Brothers singing as we celebrate St. Patrick’s Day in my childhood home, while Dad carves the corned beef …”

Inside these pages—from a bourbon-brined turkey to apple pie to the best homemade foods in New England— the real story lies in the making of memories: the desserts cooling, the turkey browning, the table aglow with anticipation. Now with the shortening days, until it seems that daylight is merely an inter mission, we turn inward, to hearth and home, for sustenance. You can’t ever overindulge at this table. Years from now that sliver of pie, the sharp scent of balsam, the bite of crisp turkey skin, the aroma of rolls hot and buttery, will mingle with the laughter of friends and family, and you’ll return to a time when the magic was never hidden, just always there.

Mel Allen, Editor editor@YankeeMagazine.com

With winter coming, there was one more short drive to take.

utting the truck away for the winter is a ritual, just as is getting it out in the spring. I don’t use the truck in the winter, one way to extend its already long life. The truck is a 1997 Ford Ranger, white with no rust. I bought it used, with a tender transmission and no gas gauge, to replace my husband’s truck, which had lasted 18 years after his death. I’ve grown to love this truck for its many uses. When I put it away in the late fall and roll the barn door shut, I know that I won’t see it again till warm weather comes. Keeping it out till the last minute is like stealing time. I like to use the truck until storm clouds carrying snow come over the hill and the first flakes start to fly.

Last November, I waited as usual, and when I felt the snow coming, I went out and started the engine. One other thing I do before I tuck it away: I take it on what I call a “victory lap” around the back field. It’s my way of saying goodbye to the field and the trees that surround it, before they take on their winter guise. And it’s also a way of celebrating one more year in the life of the truck. So I started off around the field. By this time, the ground is normally frozen or on its way to being so. But we’d just had a strange stretch of warm weather; as I approached the back of the field, the rear tires suddenly sank in and spun wildly. I put the truck in reverse and tried backing it up out of its self-dug hole. In my rear-view mirror, I could see a great spray of mud flying into the air. I went forward, which produced another fountain of mud. I did that, back and forth, mud flying, until I finally accepted that I was completely stuck, as far away from my barn as I could get. I got out to look: The truck was sunk to its axles.

Back at the house, I started making phone calls. I finally reached Brian, who plows my driveway and does many other important things for me. I sometimes call him Saint Brian. At that moment, he was busy putting his plow on for the coming storm, but said he would try to get over as soon as he could. A fine dusting had already come down, and the forecast was for a considerable accumulation. I imagined the truck stuck in the back field all winter, covered in snow and sunk in the frozen earth. That field can stay mushy sometimes into July. I felt a sadness at the thought.

I had to go to an appointment, so I held some faith that Brian could somehow liberate the truck and get it into the barn before the storm. I knew he had many things to tend to before snowfall, and many people who depend on him to keep their driveways clear. I felt stupid for taking that victory lap, for disturbing Brian from his work.

When I returned two hours later, the snow was about three inches deep and falling steadily. I didn’t see any sign of Brian and felt that he’d probably run out of time. I’d left my gloves in the truck and started to walk back through the snow to get them. As I walked past the barn, I suddenly saw faint tire tracks, now almost completely covered with new snow, leading into the barn. I peeked into the window and saw the truck safely inside, a shroud of mud weighing it down. Victory lap complete.

Edie Clark is the author of As Simple As That: Collected Essays

Order your copy, as well as Edie’s other works, at: edieclark.com

he third of November brings us the first morning this season that’s truly cold, and with it, the understanding that the truth of what’s coming can no longer be denied. It’s 23 degrees and the wind is gusting as I head into the thin, uncertain light of chore time. I’m dressed in long underwear, gloves, and the butt-ugly hat I got at the secondhand store for a quarter. Penny tells me it’s not flattering, and she’s right, but I wear it anyway, if only because it serves as an emblem of my thrift.

The ice on the cows’ water trough is a half-inch thick, and I break it with a booted foot. I pull two bales of first-cut hay from the barn, wriggling my hands under the strands of twine that contain them and serve as built-in handles. I heave the bound bales over the fence, then duck between the top and bottom fence wires, shoo the cows away from the bales, and cut the twine to release the hay. I can hear Penny in the barn—first her footsteps, then the metal-on-wood sound of her milking bucket against the frame of the stanchion, where she leaves it while she collects Pip. The sun is rising over our neighbor Melvin’s field, but not having cleared the horizon, it looks as though it’s emerging from the ground itself, a crop that was sown and is now blossoming.

Walking back toward the house while Penny milks, I watch the sunlight slowly unfold across our woodlot. With the exception of a handful of stubborn holdouts,

the deciduous trees are leafless, and the roads are clear of even the late-season discounted-tour-bus leaf peepers. Two weeks ago, you could still see the buses pulled over at the scenic overlooks, discharging their camera-wielding passengers, and you couldn’t help feeling a little sorry for those folks, because peak was at least 10 days prior, and it was really something to behold. Best foliage season in years, actually.

Around here, people call this “stick season,” that post-foliage, pre-winter period that lasts from mid-October to the first sticking snow. I used to think of it as a bleak, bereft time of year, but I’ve learned to recognize a particular beauty in the leaf-bare landscape. I see the bone-colored birches and the wrinkled-bark sugar maples and the poplars with their greenish tint. The forest floor is covered in rusty leaves; the sky is ever-shifting among the infinite shades spanning white and black. The sun is rare this time of year, but that only makes us appreciate its infrequent appearances all the more.

Not long after the first truly cold morning of the season comes the first snow, and with it, the opening of Vermont’s rifle hunting season, which begins with a weekend reserved for hunters under the age of 16. Fin and Rye have been awaiting youth hunting weekend with something close to feverish anticipation: Guns have been cleaned, sighted in, and cleaned again. Ammo has been sorted, and debates have erupted over precisely how much ammo one should carry on a hunt. “I think five shells is enough, don’t you, Papa?” Rye asks, and I agree that five shells is probably enough. “I think I’ll take six,” Fin says, and that seems fine to me, too.

Truth is, at 12 and 10, my boys are already far more experienced hunters than I am. In fact, neither Penny nor I was raised with a working knowledge of firearms. Oh sure, early in my life, when my parents lived on a 165-acre homestead in Enosburg, Vermont, there was a .22 rifle, but my sole recollection of it is limited to an episode involving a raccoon, chickens, and, as family lore has it, my buck-naked father, sprinting in late-night darkness

toward the coop, where a triple chickicide was under way. I’m pretty sure the raccoon escaped injury.

Of course, having been raised in rural Vermont, I didn’t find the concept of hunting exactly foreign. My parents had settled on a remote, rarely trafficked gravel road; every November, the population of gun-rack-bearing pickup trucks passing our house would soar. We’d pass them along the roadside, often leaning precipitously over an embankment, or straddling a ditch halffull of fallen leaves and almost-frozen rainwater. As non-hunters, we felt an unspoken anxiety inherent in the sight of all those trucks, because with the trucks came the knowledge that dozens of hunters—some of them our neighbors, but many of them strangers— were stalking the forest surrounding our home, loaded rifles slung over their backs. Did my parents post their land? I can’t remember, but even if they had, it wouldn’t have alleviated our anxiety, because few of our neighbors did, and although we didn’t know much about guns, we knew that bullets travel too fast to make sense of “No Hunting” signs.

Having been reared primarily in suburban New Jersey, Penny’s upbringing was even further removed from hunting and firearms. Her parents didn’t own a gun, nor, to her knowledge, did the parents of any of her friends. Of course, given that her childhood coincided with a household gun-ownership rate of approximately 50 percent (it has since dropped to about 32 percent), there’s a high likelihood that some of them were gun owners; she just wasn’t aware of it. But whether or not there was proximity to firearms, there was no exposure to guns and therefore no familiarity.

It was against this backdrop that about five years ago Fin developed a keen interest in hunting. In hindsight, it shouldn’t have surprised us: After all, the slaughter of livestock for meat has been part of our children’s experience almost since they were born. And our boys have always seemed most contented when immersed in wilderness.

Indeed, one of our intentions for raising them in rural northern Vermont was precisely to instill in them an appreciation of the natural world, and it’s one of our greatest satisfactions to witness their obvious love of—and connection to— the flora and fauna around our home. But somehow, either out of naïveté or simple willed ignorance, we never imagined them or ourselves as hunters.

Fin and Rye stalked our land with homemade bows for more than a year, bringing home the occasional squirrel or chipmunk before we purchased their first gun. We’d seen where all this was leading: the bows and arrows, the squirrels, the endless questions about all things hunting, the drawn-out games of fantasy they played together, involving deer rifles fashioned from sticks and convoluted, ever-changing rules about whose land they were hunting on, how many deer they could harvest, and so on. And so we’d had plenty of time to get used to the idea of our boys’ owning a gun.

We never imagined that we’d be gun owners. It never occurred to us that our sons’ relationship with nature would be mediated by deadly force.

Our boys began hunting with homemade bows and arrows; the first animal that Fin killed was a red squirrel, brought down with a bow he’d made. We didn’t need to explain to him that any animal he killed would be utilized for food; that dictum had already been instilled in him through books and mentors. Still, when it came to hunting for food, my imagination ran toward grilled venison steaks and small roasted game birds, perhaps with a side of mashed potatoes or a pile of buttered rice. What I most definitely didn’t imagine, and yet felt compelled to experience if only to support my young son, was a scrawny haunch of fried red squirrel. (For the record, it was tough and chewy and did not taste just like chicken.)

Used to it, maybe, but still not entirely comfortable with it. “I can’t believe we’re even talking about this,” Penny remarked one night, in the midst of one of our many discussions regarding guns and hunting and how they fit into our preconceived notions of what sort of family we were. But the more we talked about it, and the more we observed the boys’ commitment, evidenced by hour upon hour of bow-and-arrow practice (along with their undiminished enthusiasm for the flesh of small rodents), the closer to comfortable we got.

And that, in short, is how I found myself rising at 4:35 a.m. (I’d promised Fin I’d set the alarm for 4:30, but five minutes seemed an acceptable cheat) on the opening day of Vermont’s youth hunting weekend, so Fin and I could be deep into the woods by legal shoot time. To thwart the potential complication of who would shoot first should a deer present itself, the boys had decided to split the weekend, even if it meant less time in the woods for each of them. I rose sluggishly, envious of Penny, free to slumber for another hour or more. And not just any hour, but that sweet, deep sleep of early morning, the one that grants you the luxury of arising fully refreshed. Or at least that’s how it seemed to me as I pulled myself out from under the cocoon of covers. “Good luck,” Penny mumbled, before rolling over to face the wall and descend back into the downy folds of her subconscious.

We’d gotten used to the idea of our boys’ owning a gun. Used to it, but not entirely comfortable with it. “I can’t believe we’re even talking about this,” Penny said.

We didn’t have good luck, at least according to the common under standing of “luck” during deer sea son. Although Fin and I had the good fortune of seeing two deer, neither presented a reasonable shot. Rye and I saw nothing but tracks, perhaps because we couldn’t bring ourselves to remain motionless for more than 12 minutes at a time. “I think I’d rather walk around and have less chance of getting a deer,” Rye replied when I mentioned that we might be better served by still hunting.

I understood what he meant. It was an amazing time to be in the woods: The light was creeping into the sky, and everything seemed caught in the suspension between night and day. It was nice to sit for a few minutes, sure, but it was also nice to move on, to feel the blood quickening in our veins, to practice the inward-rolling footsteps that, once perfected, would let us move silently through the trees.

The boys and I hunted regularly through the remainder of rifle season, but we never saw another deer. But no one seemed to mind, and besides, our freezers were already nearly full with the beef, pork, and chickens we’d raised over the summer months. As with most of our fellow hunters in 21st-century Vermont, the meat wasn’t essential to our survival, and we knew that this fact itself was deserving of our gratitude.

But the early mornings in the woods? The whispered conversations with my sons as night succumbed to day? The return home to the breakfasts of fresh eggs and fried potatoes that Penny had made in our absence? The warmth of the house as we stood by the woodstove with our chilled fingers outstretched? I suppose it could be argued that even these things weren’t essential to our survival. But it sure didn’t feel that way.

Ben Hewitt’s fourth book, The Nourishing Homestead: One Back-to-the-Land Family’s Plan for Cultivating Soil, Skills, and Spirit, was published this year by Chelsea Green. benhewitt.net

Forty

At The Rocks Estate, it’s as though a rural Downton Abbey has merged with Kris Kringle’s tree farm.

BY ANNIE GRAVES

BY ANNIE GRAVES

wintry morning sun begins its climb on this early December day. All around, ridges streaked with snow remind us that we’re in the heart of the White Mountains, with New Hampshire’s highest peaks dominating the horizon. As pale light strikes the dark, perfectly pointed evergreens striping the hillsides below, with views of the Presidential Range beyond, there’s nothing in the quiet scene to hint at the liveliness to come. A landscape draped in dreams. Sixty acres of Christmas trees spread across the fields at The Rocks Estate in Bethlehem, New Hampshire. The promise of new snow hangs in the air. It’s the ideal spot for a movie-version Christmas-tree farm. At 4 Christmas Tree Lane, no less …

The Rocks Estate feels like a world apart anyway. Maybe because it dates back to the Gilded Age, when wealthy entrepreneurs like

John Jacob Glessner, who co-founded International Harvester, could assemble a couple thousand acres of property and build an estate so that his young son, George, who suffered from hay fever, could escape the Chicago summers with his family. In fact, the low pollen count and high-altitude air around Bethlehem were so celebrated at the time that it quickly became a turn-of-the-century resort destination.

So possibly it’s something in the air that accounts for the robust vigor of these trees, raying out in precise rows of spruce, balsam, and Frasier and Canaan fir, here at the beloved Rocks Christmas Tree Farm. Certainly the setting is extraordinary: an estate set in the midst of a Christmas grove. Fields of trees are offset by the beautiful European-style stone barn, a child’s playhouse, and the snowy outline of formal gardens, plus a gift shop (one of two) housed in the shingled 1903 Tool Building, where you can find tree ornaments, pet toys, and local crafts. Although the two original mansions

no longer stand, 22 other buildings still dot the estate. A rural Downton Abbey meets Kris Kringle’s tree farm.

More probably, though, the trees’ good health can be traced to their guardian, estate manager Nigel Manley, a genial Brit from gritty Birmingham who has kept things growing at The Rocks since 1986. “I was originally hired to rake leaves and split wood,” he grins. “No one knew I had an agricultural degree.”

Lucky for him, when John Glessner’s heirs left the now-1,400-acre estate to the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests in 1978, one of the stipulations was that the farm must always produce a crop—which up till that point the Society had accomplished by leasing the land to a farmer. But a year after Nigel came onboard, the farmer left, and the Society suddenly found itself scrambling for ideas.

“I learned everything on the job—I knew nothing about Christmas-tree

farms! We were planting 7,000 trees a year and we were out in the middle of nowhere. Who would come?” Nigel asks, still sounding bewildered. “We sold 12 trees that first year.”

He surveys the undulating acres of fields that today grow 50,000 trees, and shakes his head. “I can remember selling 100 trees and being so excited, thinking to myself, Where can we go from here? We can do 400 trees in a day now. It takes us all summer, with seven people working every day, to prune them.”

Flakes drift down as we walk the snow-covered road, past trees stacked and bundled like giant smudge sticks, waiting to be picked up. A snow-globe vista, as the falling flakes begin settling on the trees. The fields are crawling with candy colors—bright parkas and snow pants—and families are spreading out through crowds of fir and spruce, trying to decide which tree will hold their ornaments, shelter their gifts. On the weekends before Christmas, there might be 1,200 people combing these hills for the perfect match.

Here and there, a standing tree grabs the eye, already trimmed with glittery gold bows or ribbons, popping like the crowd extrovert. “Some customers like to decorate their tree in the field weeks before, to mark it and keep anyone else from taking it,” Nigel explains. As families wield the saws provided, trucks are circling, ready to pick up the cut trees. Most often, they’ll be loading a seven-foot balsam

On the weekends before Christmas, there might be 1,200 people combing these hills for the perfect tree.

fir, the tree farm’s equivalent of a #1 bestseller. “That’s the Christmas smell,” Nigel says. “That’s the New England scent.”

It is also, of course, the provoker of memories, this wild smell of the green outdoors that we bring into our homes at the darkest time of year. A scent that conjures indelible moments: of unwrapping a family ornament; of stringing cranberries and popcorn (one impossible to pierce, the other guaranteed to crumble); of lying under the tree and looking up through its branches at lights like tiny stars. And of the mysteriousness of wrapped presents, never as magical once they’re unwrapped.

All of this, too, awaits in the field. “It’s impossible not to get swept up into the joy of the season when you’re here,” Nigel says, for he and The Rocks’ welcoming crew are also busy crafting memories. There are horse-drawn wagon rides, roasting pits for s’mores, and 2,000 one-of-a-kind wreaths decorated by the staff’s five “Merry Wreath Makers.” The local kindergarteners plant trees that they nurture until they cut their own as sixthgraders. Yearly The Rocks joins forces with FedEx in the “Trees for Troops” program, providing free Christmas trees to American bases. At local inns, visitors can even choose holiday packages that include a Christmas tree and wreath from The Rocks.

Yes, Virginia, it is a long way from those first 12 trees, sold almost 30 years ago. But some things stay true. Out in the fields, on this cold December day, you can still see your breath hanging like a cloud. And although The Rocks sells 4,000 to 5,000 trees a year now, it still feels like a family farm, and everyone’s in a supremely good mood, which is one reason, Nigel says, why generations of families keep coming back.

In the crisp, clean cold, a steaming cup of cocoa warms the hands and mingles with the scent of fresh balsam. And a thousand Christmases are about to unfold around perfect trees cut from a hillside in Bethlehem.

More information at: therocks.org/harvest.php

Here’s the scoop on a few of our B-list forefathers and mothers.

BY KEN SHELDON ILLUSTRATION BY MARK BREWERThe original wheeler-dealer, Allerton was among those responsible for repaying the Pilgrims’ debt to the investors who had financed their trip. Instead, he embezzled from those funds and was banished from the colony. A true survivor, Allerton nevertheless succeeded in business and ended up with houses in both New Haven and lower Manhattan, near where Wall Street stands today—which figures.

While the Mayflower was still in Plymouth Harbor, young Francis—an “active” child if ever there was one—got hold of his father’s musket and fired it off, showering sparks near an open barrel of gunpowder, which could easily have blown up the ship. Later, members of the Billington family were found guilty of sedition, scandal, slander, and even murder. They were the family you didn’t want to live next door to.

Wife of William Brewster, the Pilgrims’ religious leader, Mary was one of only five adult women to survive the first winter at Plymouth and make it to the first Thanksgiving—which she had to help cook, of course. No big sur-

prise that one of Mary’s many descendants was Julia Child.

The Mayflower voyage was Hopkins’s second trip to the New World. His first ship, headed to Jamestown, Virginia, was wrecked off Bermuda. There Hopkins mutinied and narrowly escaped being hanged. He eventually returned to England and came back to the Americas aboard the Mayflower. In Plymouth, he established the first tavern, where he was fined several times for serving liquor on the Lord’s Day, overcharging for spirits, and allowing drunkenness in his establishment. The local Chamber of Commerce at the time voted him “Most Likely to End Up in the Stocks.”

The “honor” of fighting the first duel in the New World goes to Edward Doty and Edward Leister, servants of Stephen Hopkins. No one knows what the dueling Eds were arguing about, but their punishment was to be tied together hand and foot for 24 hours. Doty spent the rest of his life in Plymouth, where he was known for his quick temper, appearing in court numerous times and managing to avoid public service of any kind—which is probably just as well.

Working in the woods one day, John Goodman and Peter Browne took a lunch break and went for a walk with their dogs. The dogs saw a deer and chased it, so the men went after them. They got lost in the process and spent the night pacing beneath a tree—and ready to climb it—because they heard what they thought were “two lions roaring exceedingly.” No truth to the rumor that descendants of Browne and Goodman founded AAA.

This unsung heroine was married to shoemaker William Mullins, who brought 250 shoes and 13 pairs of boots with him on the Mayflower. (“But did you remember the sunscreen? No.”) Sadly, Alice died soon after arriving at Plymouth, but she nevertheless had a vast number of descendants, one of whom was Marilyn Monroe, who also had a lot of shoes.

A fortunate survivor of that first winter, Susanna had some notable firsts to her credit: first baby born in the new colony (while the ship was still in the harbor); first bride, a few months after her first husband died; and first person to say of Plymouth Rock, “That’s it?”

t’s a mix of shadow play and cookie making … “It” is hand-cookie making, which can be as creative as you are and as traditional as you make it. Hand cookies in their simplest form are cut out around an outspread hand—and a child’s hand is the most convenient size for a cookie. But hand cookies can be much more than that: A butter knife can trace around thumbs and forefingers to make swans … and signs of peace and angels with beautiful wings …

Roll the dough out to about an eighth of an inch thick, and cut around your hand, or a child’s hand, with a butter knife … We make geese by closing our fingers and adding a neck and head coming out at the wrist. You can make a dog by tracing around the hand in the position for a dog-shadow picture.

The fingers of both hands can form the skirt and wings of an angel; put a round head where the palm ends at the wrist. Or you can make people by using your right thumb and two fingers for one arm and two legs and tracing your left thumb for the other arm. Use sunflower seeds, nuts, and currants for buttons and eyes and for fingernails and jewelry on the hands.

—“Cookies Made by Hands,” by Robin Hansen, December 1983

—Hubert Prior Vallee (1901–1986). Born in Vermont and raised in Maine, and known around the world as Rudy Vallee, he was a mix of Sinatra with a dash of Justin Bieber—America’s first pop star. His soft “crooning” style is said to have influenced Bing Crosby, Sinatra, and Perry Como. He toured the country with “Rudy Vallee and the Connecticut Yankees,” and in time his talents brought him to Hollywood. He died in California at age 85 and is buried in Westbrook, Maine.

“The kids of today have taken over the music business—most of them very young. Simply because they write and jot down a few notes, they have the idea that they can write songs.”

birth order of Louisa M ay Alcott among her four sisters

1832

year Louisa M ay Alcott was born

0

initial level of interest when a B oston publisher proposed to Alcott that she write a book “for girls”

1000 approx. number of copies of Little Women currently sold every month (it’s never been out of print)

22+ times the Alcott family moved in 30 years owing to financial constraints

70 days it took to write Little Women

147 years since Little Women was first published

OVER 50 translations of Little Women worldwide

$945

amount paid by Louisa’s father, Amos Bronson Alcott, for O rchard House in C oncord, M ass., where she wrote Little Women

30,000-50,000

number of visitors O rchard House museum receives annually

Enjoy priceless memories with your family at Cape Arundel Cottage Preserve, minutes from the famed beaches of southern Maine and Dock Square, the heart of Kennebunkport.

Tours available Thursday through Monday, 10am-4pm; other times by appointment.

Call 207-451-0218 or visit capearundelcottages.com

• 200 wooded acres: cozy cottage clusters, 65 acre preserve

• Direct access to the Eastern Trail

• 850 to 1350 square foot cottages

• 7 models and many optional upgrades

• Clubhouse, pools and many other amenities

• 9 minutes to Dock Square, Kennebunkport

• Waterfalls, ponds, fountains, gardens, and more

• Special pre-clubhouse pricing starting at $209,500

THIS PAGE : The stairway in Kristin Nicholas’s home is festooned with her art, from the hand-painted walls to the knitted mittens to the embroidered pillow. OPPOSITE : Kristin loves to juxtapose rich colors, such as chartreuse with shades of red and turquoise.

THIS PAGE : The stairway in Kristin Nicholas’s home is festooned with her art, from the hand-painted walls to the knitted mittens to the embroidered pillow. OPPOSITE : Kristin loves to juxtapose rich colors, such as chartreuse with shades of red and turquoise.

by Julia Quinn-Szcesuil

by Julia Quinn-Szcesuil

he traditional white-clapboard exterior of Kristin Nicholas’s 1751 farmhouse, nestled in the rolling hills of western Massachusetts’ Pioneer Valley, betrays no sense of the boisterous visual party within. Outside, there are stone walls, weathered sheds, and pastures. But inside is a happy riot of color, with brightly painted walls, jewel-tone furniture, kaleidoscopic kilim rugs. It’s a fanciful place, an adaptation to the stark and stony winter landscape where Kristin and her family manage a flock of 300 sheep on their farm. “In western Massachusetts, from the end of November really until the end of April, there’s just gray everywhere,” she says. “For all those months you have to do something to make it joyful and happy.”

And so the center-chimney Cape in Leyden that she shares with husband

Mark Duprey, daughter Julia, and a bevy of animals isn’t just the heart of Leyden Glen Farm (whose atmosphere she lovingly calls a “circus”)—it’s a beacon banishing the early-winter darkness.

Color is Kristin’s signature statement, saturating all her creations: textile designs, oil paintings, pottery, knitwear, the hand-painted dining-room walls. When the holidays come around, her exuberant spirit is reflected in every corner, as is her decorating motto: handmade, colorful, cozy, and very, very sparkly.

“My holidays are about color and texture and making things,” says Kristin, whose latest book, Crafting a Colorful Home (Roost Books), was released early this year. “To me, that’s home—having a lot of handmade things around you.”

(text continued on p. 32)

Kristin’s husband, Mark Duprey, tends to their flock of 300 Romney sheep, raised for meat and wool.

Kristin’s husband, Mark Duprey, tends to their flock of 300 Romney sheep, raised for meat and wool.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT : Lanterns and a birchbark Christmas village further brighten the lively living room; vintage linens and Sherwin-Williams

“Tomato Red” paint jazz up an antique baker’s cabinet; Kristin uses leftover yarn to make festive holiday pom-pom decorations (go to YankeeMagazine.com/garland for instructions); a display of pottery combines Kristin’s own work with vintage pieces.

Our model is open: Mon-Fri 8-4:30, Sat 9-3

The holidays are also a breather for the family after the summer farmers’ markets and the autumn harvest. It’s a chance to savor time with friends in this tightly knit farming community, to recharge before winter lambing begins. Kristin sets an easygoing tone at Christmas, using armloads of greens from the yard, favorite sheepthemed decorations, hand-knitted stockings, and strings of twinkling lights (which stay up until April). Stacks of thick woolen afghans invite a put-your-feet-up mood. Nothing is fussy or hands-off—Kristin wants her guests to relax.

Her love of craft has deep roots. Smitten with fabric as a young girl in New Jersey, she loved the details in her German-born grandmother’s hand-embroidered sheets and afghans. At 13, she spent 50 precious cents at auction for a quilt so filthy her mother wouldn’t let her bring it into the house. With determined cleanings, the quilt was restored; it remains a treasure. Later, in college, she signed up for some textile classes and “the world opened up to me,” she says. Now she designs knitting and embroidery patterns, wallpaper, pottery, fabric, and a line of yarns. Living in a remote corner of New England, she’s had to adapt her business, welcoming students to the farm for classes and retreats, and teaching classes online through the site Craftsy. “I like to teach people that they can do this, too,” she says.

“I like to teach people that they can do this, too. It’s all easy. I have no patience for anything too fiddly.”Models on Display Discover the charm of early New england homes O ur 1750s style cape home building system boasts beautiful timbered ceilings, a center chimney, wide board floors and custom, handmade features in the convenience and efficiency of a new home.

Using items found almost entirely in the woods (except glue, glitter, and cardboard), Kristin fashions whimsical holiday houses that she likes to give as gifts or keep for herself.

MATERIALS

n repurposed cardboard from cereal, butter, or cracker boxes

n natural materials: birchbark (from fallen trees, not live), acorns, acorn caps, moss, dried flowers

n multipurpose or wood glue

n glitter

1. From the cardboard boxes, cut a matching pair of square pieces for the front and back. Now cut 2 matching pentagon shapes for the sides of the house. Cut a length of cardboard for the roof and fold it in half.

2. Assemble a small four-walled house by attaching the cardboard at the seams with glue. Glue on the roof piece.

3. When the walls are dry, layer strips of birchbark siding onto the walls and roof, acorn caps stuffed with a bit of moss for a wreath, moss on the roof, and acorns for a footpath. Apply glitter for sparkle.

“It’s all easy. I have no patience for anything too fiddly.”

Every year, Kristin and her four sisters hold a post-Thanksgiving crafting party on Black Friday. Gathering materials in the woods, they invent fanciful creations, such as the tiny houses crafted from birchbark and recycled boxes that they still make every year. Using acorn “wreaths,” bits of evergreen adornment, and sparkly glitter, the homes would suit any woodland fairy.

It’s one festive way of staying connected to the land, even in winter. Kristin has always felt that pull. She loved her dad’s tales of childhood summers spent on his grandparents’ farm. “I thought it sounded fascinating,” she said. “I was sucked into the romanticism of it.” But it was Mark who enchanted her with tales of his country hometown. “In our first conversation he said, ‘I come from the most beautiful place in the world,’” she says. “So I knew it was pretty around here, but the first time I came, I fell in love.”

And so she has made a home here, where comfort and joy reside long past holiday season. A soft plaid blanket embellished with one of Kristin’s wool flowers waits to be draped on a lap; piles of pillows made from patterned remnants invite serious nesting; brightly painted lampshades reflect muted light. “It all adds another layer of warmth,” she says. “Color is really enveloping. It makes you feel safe and cozy and warm.”

To learn more about Kristin and to read her musings on design and farming, visit: kristinnicholas.com. More festive holiday decorating ideas at: YankeeMagazine.com/Décor

Stairlifts. Aren’t they all the same? Getting people up and down the stairs? At Stannah we don’t agree. For example, we’ve designed chairs that fold up neatly at the push of a button, and recharge themselves constantly for reliable service. For stairs that turn we custom-make your stairlift to hug the stairs. Our outdoor model has proven itself in the toughest climates, and we have a range of options that’s second-to-none.

Providing you with good value

You can choose to buy or rent new or expertly reconditioned stairlifts, for both curved or straight staircases, with a sevenday money-back guarantee.

The leading stairlift supplier We’ve made over 600,000 stairlifts - more than any other manufacturer - and have the experience to help you make a wise decision, so take the next step - call us today!

Mortise & tenon red cedar. Moveable & fixed louvers, raised panels, board & battens, cutouts, arches & more. Full painting service & hardware. Interior styles also available. Family owned ~ Made in USA

203-245-2608

shuttercraft.com

We will custom design a braided rug to meet your needs in any size and over 100 colors. Stop by our retail store and factory at: 4 Great Western Rd. Harwich, MA 03645

888-784-4581

capecodbraidedrug.com

Not all stairlifts are the same. This one certainly isn’t.

Yankee likes to mosey around and see, out of editorial curiosity, what you can turn up when you go house hunting. We have no stake in the sale whatsoever and would decline it if offered.

BY GUEST MOSEYER TIM CLARKdrove to Cape Cod, hardly thinking about the fact that it was July 2, the last workday before the long Independence Day weekend. However, traffic was surprisingly light, and I crossed the Sagamore Bridge at about 11:30 a.m., in plenty of time to meet Bobbi Cox, owner and broker for Mulberry Cottage in Barnstable, at noon.

“It’s close to the road,” she warned me ahead of time. And why not? It was built around 1640, when the only traffic to be concerned about was the occasional war party of Wampanoags investigating the tall-hatted strangers who had shown up 20 years earlier in Plymouth, robbing Native burial sites of grain to keep from starving. Eventually the Pilgrims, as we’ve come to know them, and the local tribes made peace over a big meal. But that’s another story.

The road, now Route 6A, is also called Main Street, or Old King’s Highway, which gave its name to the National Historic District that was declared in 1973. It’s the largest in the nation, encompassing more than 1,000 acres and nearly 500 buildings.

Living in a National Historic District is a mixed blessing. On one hand, the owner of a property must get the approval of the local board for any changes to the exteriors of buildings and structures (including paint colors), fences and signs, and new construction or demolition.

On the other hand, it’s beautiful. And who wants to buy a 375-year-old house on Cape Cod in order to change it?

The house was built for Samuel Hinckley, one of the earliest settlers. Somehow he and his wife managed to stuff 13 children into a two-room halfCape (“They must have hung them on hooks,” Bobbi remarked), and until the early 1900s, it was called the Hinckley House. (I read that Samuel Hinckley is said to be an ancestor of three presidents: Obama and father and son Bush.)

That changed when the Beale family moved in and planted a mulberry tree in the front yard. It has been Mulberry Cottage ever since, even though the tree blew down in a storm decades ago.

The Beales were local landmarks. Louise Darwin Miller (Mrs. Arthur Beale), a poet and dedicated bicyclist, was famous for her daily 16-mile round trip from Barnstable to the South Shore and back, which she celebrated in verse:

No gas, no oil

Do I need!

No traffic cops to fear!

My pedal’s license covers all,

As across the Cape I speed!

OPPOSITE: Mulberry Cottage owners Bobbi Cox and John Powlovich. THIS PAGE, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: The house and property offer a tasteful blend of old and new. A modern kitchen features worn brick walls; a spacious addition was built on the footprint of the original barn; the library and staircase retain many historic features, including wide floorboards.

Cottage residents at Piper Shores enjoy spacious, private homes while realizing all the benefits of Maine’s first and only lifecare retirement community. Our active, engaged community combines affordable independent living with guaranteed priority access to higher levels of on-site care—all for a predictable monthly fee. Call today for a complimentary luncheon cottage tour.

Discover the promise of lifecare.

Maine’s first CARF-CCAC accredited community

(207) 883-8700 • Toll Free (888) 333-8711

15 Piper Road • Scarborough, ME 04074

www.pipershores.org

Bobbi Cox and her first husband, Bill, bought Mulberry Cottage in 1984, and Bobbi has made it a showpiece, preserving historic features (Indian shutters, wide-board floors, corner closets, a narrow staircase that winds around a massive central chimney) while adding modern conveniences such as a stateof-the-art kitchen, walk-in closets, and built-in bookshelves everywhere. In addition to 3,700 square feet of living space (five bedrooms, three and a half baths), there’s a spacious barn in back— a 1997 replica of the original barn—all on a landscaped lot of just under half an acre. It’s offered for $725,000.

There are too many treasures inside to describe, but I have to mention the museum-quality collection of wooden duck decoys belonging to Bobbi’s second husband, John Powlovich. John is the kind of collector who prefaces all his comments with “I’m no expert” and then demonstrates his expertise.

I could have spent all day at Mulberry Cottage, but Bobbi had other commitments, and I needed to get off the Cape against the inflowing tide of Independence Day tourists. But she generously gave me a brief auto tour of Barnstable, which seems to have the Nation’s Oldest This or the First American That on every corner. And of course there are heart-lifting glimpses of the ocean and the dunes of Sandy Neck a short walk from the house. Little wonder that Mrs. Beale wrote of the house:

The mulberry tree has grown so huge, The house was hard to find, But when we found the key-hole, And opened wide the door, All the rooms were smiling at us: The house that we adore.

For details, contact Bobbi Cox, Kinlin Grover Real Estate, Osterville, Mass. 508-420-1130 (office), 508-737-3763 (cell); bcox@kinlingrover.com. Read classic HFS stories from our archives at: YankeeMagazine.com/house-for-sale

“Oldest Summer Resort in America” Now a Four-Season Destination! Year-Round Shopping, Dining & Lodging. Downhill and Cross-Country Skiing. Visits to Santa’s Hut. Snowmobiling. Ice-Fishing. Art Galleries. Skating. Cozy Fireplaces. Festival of Trees. Snow-shoeing. Concerts. Fireworks. First Night® New Year’s Eve Events. Ask for a FRee Brochure! at wolfeborochamber.com 603-569-2200 • 800-516-5324

“Work and Live Where You Love to Play” wolfeboronh.us redjacketresorts.com/holiday

nce in a while, the past rises up unexpectedly. It can happen in a flash—a taste, a smell, a look— to rattle our equilibrium and spark long-buried memories. It can even trigger a strange nostalgia for something we’ve never known. And it can happen on a hillside, deep in the woods.

The vertigo-inducing ski jump at Satre Hill, in Salisbury, Connecticut, does that. It’s a dizzying, 30-meter-long slope that has launched (literally) junior jumpers and Olympic hopefuls for more than 80 years. It brings shivers just standing at the bottom. Exhilaration, too. A reminder of days gone by, when thrills required actual skills—not the bungeejumping zipline variety.

Satre Hill says something about Salisbury, too—because the ski jump isn’t simply a daredevil dinosaur or a quaint village attraction, buffed up for tourists. The all-volunteer Salisbury Winter Sports Association (SWSA) keeps the hill’s tradition alive. It’s a source of tremendous community pride, and more than 600 locals have donated funds to spruce it up. Parents volunteer, families forge bonds, and kids learn to fly. That it also happens to be tucked down an impossibly picturesque Robert Frost–snowy road, not far from Salisbury’s Main Street, is just one more point for nostalgia.

Tucked away in Connecticut’s Litchfield Hills is a lovely town where it’s possible to take flight.Spectators gather at the foot of the Satre Hill ski jump, with the town at their back, hidden through the woods not far behind.

Salisbury is pretty, the way you’d expect a historic town in the Litchfield Hills to be. Preserved farmland and expansive fields surround the township, incorporated in 1741, which includes the artistpacked village of Lakeville. The Appalachian Trail snakes along its borders, and in summer hikers pushing toward Maine to finish the entire 2,168-mile trail are a frequent (aromatic, some say) presence. The streets are filled with plenty of broad, beamy antique homes, just the right number of shops to supply the essentials, and a handful of restaurants and bakeries to feed the weekenders. Plus a fine dusting of low-key celebrities to remind you that we’re only 100 miles from New York City.

“It’s a little too far to be a real commuter town,” says Richard Boyle, former director of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, who has co-owned the Earl Grey B&B with his wife, Patricia, for the past 21 years. But it’s certainly convenient when you crave a city fix—or if you’re Meryl (Streep) Gummer, who chose this laid-back yet sophisticated town as the place to raise her family. “Salisbury is everybody’s little secret,” Boyle says.

Scoville Memorial Library anchors the south end of town; The White Hart, a 19th-century inn, secures the north. Both are nourishing places where you can dip a toe into village life.

Native stone lends weight to the nation’s first free public library—with museum curators, writers, and photographers popping in to give weekly talks. The White Hart sees its share of lively chatter in the Tap Room, lit by a crackling fire; the inn’s more-formal dining room was recently listed among Bon Appétit ’s 50 nominees for 2015’s “Hot 10” roster of best new restaurants. Neighbors gather for the holidays in front of the inn to light the Christmas tree and sing carols on the village green.

Scratch a little deeper, and you’ll find dramatic possibilities at Aglet Theatre Company—named for the doohickey on a shoelace—founded in Salisbury in 2005 to perform staged readings on “less than a shoestring” (so successfully that they needed a larger space in nearby Sheffield, Mass.). Plus, The Hotchkiss School, a renowned co-ed boarding school in Lakeville, opens its golf course, two Olympic-size pools, track, and skating rink to locals.

With dozens of books about gardening and cooking under her belt, Jacqui Heriteau brings a flavorful expertise

and “French ethos” to Country Bistro, the intimate café she runs with her daughter Holly, just off Main Street. A few blocks away, at the other end of town, Mary O’Brien’s homey Chai

walla Tea Room steams up the windows with endless pots of tea and earns raves for “Mary’s Tomato Pie.”

Side-by-side bakeries swell the village midsection: Sweet William’s, for early-morning cappuccinos and croissants, and Salisbury Breads, where rustic loaves warmed by rosy walls make a strong argument for gluten. Off the beaten path (but make a reservation), The Woodland in Lakeville is a favorite sushi-chic hotspot—the chef’s tuna crudo on a delicate whip of arugula is like a taste of summer in January.

You really can get almost everything downtown, thanks to LaBonne’s Market (a mini Whole Foods) and the attractively old-fashioned Salisbury General Store & Pharmacy (from cold remedies to dish towels).

After that, it’s all fun and games: Peter Becks Village Store for sporty Patagonia clothing, or Prime Finds for upscale used home furnishings at bargain prices. You can pick up a first edition at Johnnycake Books, an antiquarian bookseller housed in a 19thcentury farmer’s cottage. “Salisbury has

been a destination for book collectors for almost 100 years,” says owner Dan Dwyer, who’s lived here since 1985; in the past he worked for CBS and wrote speeches for presidents.

“People start as weekenders, fall in love, and find a way to retire here,” notes innkeeper Patricia Boyle. In fact, weekenders make up 50 to 60 percent of Salisbury’s current population, depending on whom you ask. It wasn’t always that way. “It was the most affordable, accessible, and prettiest town [in the ’80s],” says Dwyer, who’s been active in town affairs, sold real estate, and even run for the state senate. “The real estate here is driven by the Wall Street economy. But you can still find places, if you look.” With its rural properties and well-off owners, Salisbury boasts the lowest property tax rate in Connecticut.

At Satre Hill, the SWSA teaches ages 6 and up, with a Winter Ski Jump Camp during Christmas break and training from December to March. The Eastern National Ski Jumping Championships are an annual inspiration to all, and the February Jumpfest Weekend offers plenty of competitive fun in the 20- and 30-meter categories, plus ice carving and a Snow Ball Dance.

The White Hart offers airy in-town rooms; the Earl Grey B&B, Richard and Patricia Boyle’s stately 1850s Italianate mansion, overlooks the center of the village, with the largest documented Norway spruce in the country in their back yard.

For more information, visit: salisburyct.us; litchfieldhills.com; and nwctchamberofcommerce .org. For more photos, go to: YankeeMagazine .com/Sal

If an authentic Vermont holiday experience is on your bucket list, look no further than Billings Farm & Museum. Discover how Thanksgiving was traditionally observed in their 1890 Farm House; from preparations, to the menu, to entertainment. Learn how Christmas was celebrated in the late 19th century and linger in the cozy kitchen as treats are baked in the woodstove. Try your hand at making historic ornaments. And don’t miss the wagon and horse-drawn sleigh rides (weather permitting). 802-457-2355.

BillingsFarm.org

“Casual Elegance” has been used to describe Jackson House Inn. Located just outside the perfect Vermont village of Woodstock, the Inn offers a balance of antique furnishings and

present day amenities. One of the most noted guest highlights is their locally sourced, farm-to-table breakfast. Served in a “chef’s table” approach, Rick describes each dish he prepares along with its local connections. After you’ve fueled up, hit Killington’s Skyeship gondola, just minutes down the road, or enjoy the area’s cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, dog sledding, snowmobile tours, and ice skating. 802-457-2065. JacksonHouse.com.

Picture this perfect Vermont getawaywake up at the cozy Woodbridge Inn, located minutes from Woodstock’s famous village green. Grab a tasty breakfast and fresh roasted coffee before driving 10 minutes to the Skyeship Gondola at the base of Bear Mountain/Killington. At the end of the day, ski back to your car and head to the Inn for their Soup Supper in front of the woodstove. Got a large group or family? Take over the Inn

with a “whole house” rental. Custom packages available. 802-396-0077.

Familyfriendly slopes, 30 km of groomed Nordic trails, and on-site

The Woodstock Inn & Resort is a true outdoor winter wonderland. Once you’ve had enough mountain air, come inside for some farm-fresh cuisine at one of the Inn’s restaurants. Or, delight your senses at The Spa, featuring a four-season courtyard, outdoor fireplace, and even a Japanese lilac meditation tree. If that’s not enough, check out their new Falconry Center, where professional falconers provide a hands-on encounter with these magnificent birds of prey. 802-332-6853. WoodstockInn.com

When You Go: Take time to meander through the town’s 30+ independently owned shops and galleries. Among the mix, you’ll find Vermont’s oldest book store, The Yankee Bookshop (Est. 1935) and the historic FH Gillingham & Sons General Store (Est. 1886).

ew England’s darkest season is filled with light. The coolest illuminations shine not only with electrical sparkle but with gigawatts of community energy and pride. Bundle up and take part in one or all of these five magical spectacles, and you’ll be able to check both “merry” and “bright” off your holiday dreaming list.

As for any parade, spectators bring their chairs, they line either side of the route, they buy food and beverages, they cheer and applaud. But the looks on kids’ faces are the giveaway that this is no ordinary procession. For the 13th year, following the 6:00 p.m. tree lighting at Mystic River Park in Mystic, Connecticut, nearly two dozen wildly decorated dinghies, sailboats, and powerboats will cruise down the river from Mystic Seaport, their festive lights amplified by the water’s reflection. Reserve a room at The Steamboat Inn or a table at S&P Oyster Company or Red 36 far in

Yuletide magic comes alive as towns and cities all across New England don their finest illuminated displays. |

advance: These ultimate viewing spots are warm. November 28, 2015. mystic chamber.org/events/holiday-events

Stone Zoo in Stoneham, Massachusetts, will continue a 20-year tradition when it twinkles with more than 200,000 lights from 5:00 to 9:00 p.m. nightly. Animated displays, brisk carousel rides, and the chance to whisper wishes to the head elf himself at Santa’s Castle add to the enchantment. But nothing outshines the zoo’s prime attraction: animals. Snowy-white Arctic foxes, Canada lynx, North American porcupines, silvery barn owls … You won’t see reindeer fly (they’re resting up for their big night), but you can have your photo snapped with one of Rudolph’s sidekicks for a small fee. November 27–December 31, 2015. zoonew england.org/engage/zoolights

Vocalists harmonize. A firetruck delivers Santa. Volunteers serve 60 gallons of hot chocolate and 6,000 home-baked cookies—all donated, all free. Divers surface, raising the underwater Christmas tree. But for everyone gathered at Sohier Park in York, Maine, the mostanticipated moment arrives at 6:00 p.m. on the Saturday after Thanksgiving. The countdown leads to a resounding “Ahhh!” as Cape Neddick Light, a.k.a. “the Nubble,” is outlined in razorsharp beams. A beacon of hope, it radiates into the new year. Can’t be there? A second chance to see the Nubble illuminated occurs during York Days in July. Or watch via webcam for the first time this year. November 28, 2015–January 2, 2016. nubblelight.org

When UK-born artist Gowri Savoor searched for a community to host a lantern parade in her adopted home state of Vermont, she found an ally in

Waterbury art teacher MK Monley. After coaxing 400 elementary kids to craft LED-illuminated paper lanterns in 2010, Monley says, “I swore I’d never do it again.” But after Tropical Storm Irene’s devastation in 2011, the community needed this whimsical parade, and today it’s a beloved tradition that’s grown into an even more festive celebration, with live band music and more than 500 glowing lanterns created by everyone from preschoolers to professional artists. You can make one and you can march, too. The 5:00 p.m. procession along Main Street concludes

La Salette Shrine Christmas Festival of Lights

“We want to be a place of welcome for people from all walks of life, all religions,” says Rev. Cyriac Mattathilanickal, director of the Retreat Center at La Salette Shrine in Attleboro, Massachusetts. And so began a tradition that’s now 62 years old: a free display of 450,000 lights—most now energy-efficient LEDs—drawing as many as 15,000 visitors between 5:00 and 9:00 p.m. on peak evenings. With concerts, Masses, a public cafeteria, a Chapel of Light flickering with 3,000 candles, and a crèche museum featuring 2,500 nativities from around the world, the La Salette community preserves the spirit of Christmas for generations of families. November 26, 2015–January 3, 2016. lasalette-shrine

.org/index.php/christmas

Check out our picks for best holiday festivities at: YankeeMagazine.com/ Celebrations

everythingnewengland.com

n the morning of December 17, 1773, a Boston teenager named John Robinson spotted a wooden tea chest half-buried in the sand. Along with more than 300 others, it had been dumped into Boston Harbor the night before by rebel colonists protesting “taxation without representation.” Destroying more than 90,000 pounds of East India Company Tea, this treasonous act in defiance of the British Crown became a battle cry of the Patriot cause. Knowing the risk should he be caught with it, John carried the chest home anyway, securing a rare memento of what we now call the Boston Tea Party.

Of the 340 chests tossed overboard that night, only two survived. (The other is at the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum in Washington, D.C.) Preserved within the Robinson family for generations, where it became a home for dolls, dress-up clothes, and even a litter of kittens, the chest’s story endured thanks to family pride and countless diligent retellings. Since 2012, the chest has served as the centerpiece of the reopened Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum. Backed by generations of oral and documented history, plus forensic analysis confirming the existence of not just the same saltwater found in Boston Harbor but periodaccurate wood and nails, the Robinson Half Chest (as it’s now known) is a

compelling piece of American history.

Today, the box, measuring just 10 by 13 inches, rotates slowly within a glass cylinder over the same body of water into which it was thrown nearly 250 years ago. To see it is to experience a unique thrill. “It’s a very significant object,” says museum executive director and vice-president Shawn Ford, “because it’s the tool, the symbol, on which the Patriots put

their hands and cracked open, and then poured the tea into Boston Harbor.”

And when you stand aboard a floating replica of one of those tea-bearing ships, you can’t help but hear the echoes of that act. The museum touches both the imagination and the senses. Its state-of-the-art graphics tell of the tensions leading up to December 16, and visitors are encouraged to incite their own rebellion by throwing floating, retractable “crates” of tea overboard with a hearty “Huzzah!”

helps tell the story of a nation’s birth. |

BY AIMEE SEAVEY

But it’s the tea chest that packs the biggest historical punch (although the concluding film reenactment of the Battles of Lexington and Concord comes bullet-whizzingly close). Adding valuable color and shape to a familiar tale, Robinson’s chest gives new voice not just to the events of the Boston Tea Party but to the larger story as well—the story of the New England colonists who rebelled against the most powerful nation in the world, and won.

“I want people to leave here knowing that this indeed was the single most important event that led to the American Revolution,” Ford says. “Ninety percent of all the action, all the battles, all the bloodshed, happened here in Boston and New England.

“Philadelphia gets a lot of historic credit, but let’s face it,” he says with a smile, “Philadelphia did the paperwork.”

And it’s that sacrifice that Ford hopes visitors will remember most when they leave. “We gave up our lives here, and I think that’s the story that people leave here in awe of,” he notes. “Who of us today would throw away our livelihood, our savings, our wealth, our property, even tear apart our families, with no guarantee of success—in fact, with every guarantee of failure—just based on an idea? Now that’s an incredible story.”

And thanks to John Robinson’s boldness on that cold December morning, and the proud generations of Robinsons who followed, it’s a story being told more clearly and colorfully in Boston today than ever before.

Each year the museum, in collaboration with the Old South Meeting House, hosts a lively reenactment of the Boston Tea Party that we highly recommend. This year’s event is scheduled for Wednesday, December 16, 2015.

RHODE ISLAND

CHRISTMAS AT THE MANSIONS

NOVEMBER 21–JANUARY 3

Three magnificent Newport homes—The Breakers, The Elms, and Marble House—are filled with thousands of poinsettias, fresh flowers, evergreens, and wreaths. Trees are decorated, tables are elegantly set, and white candles flicker in the windows, all to create a magical holiday setting. Newport, Rhode Island. 401-847-1000; newportmansions.org

NOVEMBER 27–DECEMBER 30

Ride the rails at the Connecticut Trolley Museum, either in a closed car or, for those hardy enough to brave the cold, in an open “electric sleigh.” Join the motormen in singing traditional carols as the trolley traverses the “Tunnel of Lights,” and later, warm up in the Visitor Center while sipping a steaming cup of hot chocolate and admiring the many model trains and displays. Check the website for the full schedule. East Windsor, Connecticut. 860-627-6540; ceraonline.org

DECEMBER 12–13

The Opera House plays host to this delightfully competitive gingerbread-house contest, featuring castles, cabins, and everything in between, all constructed of gingerbread and assorted other confections. You’ll be serenaded by live music as you stroll past the magical creations and shop at the holiday bake sale. Boothbay Harbor, Maine. 207-6336855; boothbayoperahouse.com

DECEMBER 11–13

Featuring 175 exhibitors, CraftBoston Holiday at the Hynes Convention Center is a must-attend event for artists, collectors, and craft enthusiasts. Conveniently located in the fashionable, concentrated shopping district of Back Bay, this annual show is the place to find one-of-a-kind gifts, while meeting and supporting the artisans who made them and learning about fine contemporary crafts and craftspeople. Boston, Massachusetts. 617-266-1810; societyofcrafts.org

DECEMBER 1–31

Celebrate the winter, the warmth, the light, and our collective memories of holidays past. Created by The Music Hall in partnership with Strawbery Banke Museum, this month-long, citywide program celebrates its 10th year with a diverse lineup of events, including readings, presentations, candlelight strolls, gingerbread houses, skating— and a taste of Broadway, as the Ogunquit Playhouse brings Irving Berlin’s White Christmas: The Musical to The Music Hall. See the website for the full calendar of events. Portsmouth, New Hampshire. vintagechristmasnh.org

NOVEMBER 27–29

Discover how Thanksgiving was observed at the 1890 Farm House at Billings Farm & Museum. Visit the parlor for the “History of Thanksgiving” program, plus don’t miss the cider pressing, horse-drawn wagon rides, and harvest and food-preservation activities for all ages. It’s also the last weekend of the season to see Billings’ farm-life exhibits. Woodstock, Vermont. 802-457-2355; billingsfarm.org

he table was splendidly set for Christmas Eve dinner. Red candles flanked a centerpiece of evergreens and flowers; napkins were tied with ribbons and holly. A cheery fire blazed on the hearth. But no dinner would be served, since this was Christmas 1912, preserved as if in amber. I was at Hildene, home of presidential son Robert Todd Lincoln and his family, tucked between the Green and Taconic mountains outside Manchester, Vermont. Although Hildene was the Lincolns’ summer retreat, they spent at least three Christmases here, and each December, Hildene’s curators deck the house in the style of a century ago. “We learn more every year about how people like the Lincolns decorated,” docent Melissa Smith told me. “We’re always striving for accuracy in portraying Hildene as it was at Christmas in their day.”

That portrayal even extends to the tree, a Vermont white spruce like the one that the Lincolns would have had cut. “In those days they preferred trees with big, open branches,” Smith explained, “so that they could hang ornaments within the tree instead of just on the outside.” Many of Hildene’s ornaments are period antiques; others, including strings of popcorn and cranberries, are old-time homemade baubles.

It was Christmas Eve throughout the house, where it seemed as though the family had just gone out. Cards lined a bookshelf; red velvet stockings hung over the parlor hearth. I ducked into a servant’s room and saw a tabletop tree. The butler had been wrapping presents in his bedroom. But Mrs. Lincoln must have been at home; carols, and a Bach toccata, floated from the thousand pipes of her Aeolian organ.

many vermont communities put on a show for the holidays, but two of those towns — manchester and woodstock — make an especially festive effort.

Built in 1905 in Manchester, Vermont, for Robert Todd Lincoln and his family, Hildene is decked for the holidays in Gilded Age splendor. The light-filled dining room features Georgian Revival architectural details and original family furnishings.

Built in 1905 in Manchester, Vermont, for Robert Todd Lincoln and his family, Hildene is decked for the holidays in Gilded Age splendor. The light-filled dining room features Georgian Revival architectural details and original family furnishings.

I was wishing that I could stay for

Many Vermont communities put on a show for the holidays, but I’ve discovered two—Manchester and Woodstock—that make an especially festive effort. Turning back the Christmas clock at Hildene is only one part of a celebration that ranges over several weeks throughout the twin villages of Manchester and Manchester Center. Woodstock’s festivities culminate in a mid-December weekend of music, firelight, and a horse-drawn parade.

Manchester Merriment and the area’s Christmas hospitality are the places where hospitality is the stock in trade. Fifteen area hostelries participate in two weekends of inn tours, each out to top the other in cookies and evergreens, cocoa and holly. My own base , where, as I sat in the charmingly decorated parlor, I learned just how popular Manchester has become in the weeks before Christmas. “We’re here for the second time,” said one guest to another in a decidedly Appalachian accent as the two sat by the fire, “but it seems that everyone we meet here is on their 12th or 13th visit.”

The man was from Kentucky, and his observation was seconded by innkeeper Frank Hanes. “People book way in advance,” he said, “and come here every year at this time.” No one at the inn was a skier, so the draw must be Manchester’s Christmas cheer.

I inn-toured my way between Manchester Center and Manchester, with a notable stop at the sprawling and spa(best snacks, with smoked salmon breaking in on the endless march of cookies), and finally Wilburton

. Here I discovered a Christmas tradition that started as something entirely spontaneous—something so gloriously loony that it never could have been planned or put on a program.

Because nobody could have come up

I was standing in the Wilburton’s great baronial salon, toasting myself by the fire (and, yes, munching cookies) and admiring a Christmas tree that looked as though a cadre of stylists had descended

on the inn after finishing with the White House. The truth, I soon learned, was even more remarkable.

“Do you like our tree? I’ll tell you how it gets decorated every year.” Melissa Levis, who, with her father and brother, Albert and Max Levis, runs the Wilburton, was standing with me alongside the cookie table, keeping an eye on her Cavalier King Charles spaniel (who, in turn, had his eye on the cookies). “Three women from New York State stay with us on ‘girls’ weekend’ trips a couple of times a year. Back in 2005, a few weeks before Christmas, they were sitting by the fire after a cocktail or two. The power was out, the tree was up, and the ornaments were still in boxes. One of them said, ‘Let’s decorate the tree.’ They did—and they’ve done it ever since.”

A sampling of Yuletide shopping destinations in Manchester and Woodstock, where you’ll find treasures big and small for everyone on your list … For more suggestions, visit Manchester & the Mountains Regional Chamber of Commerce (visitmanchester vt.com) and the Woodstock Area Chamber of Commerce (woodstockvt.com).

MANCHESTER

Manchester Designer Outlets

More than 40 stores, from Ann Taylor and Armani couture to Yankee Candle home fragrances and Yves Delorme linens—plus fine art, apparel, footwear, cosmetics, birdhouses, and everything in between, all in a series of authentically restored buildings. 800-9557467; manchester designeroutlets.com

Mother Myrick’s Confectionery

Everything to make your holidays merry and bright: chocolates, caramels, cookies, cakes, pies, hot-fudge sauce, pastries, and signature buttercrunch. 802-362-1560; mothermyricks.com

Northshire Bookstore

A favorite New England destination for book lovers, housed in a 19thcentury former inn, with

a café, kids’ floor, gifts, and stationery. 802-3622200; northshire.com

Orvis Company

Flagship store featuring the company’s renowned fly-fishing department, plus clothing, travel equipment, and more. 802-362-3750; orvis.com

Village Shops at the Equinox Neat white-clapboard houses, located across the village green from the Equinox Resort & Spa (195 rooms in 5 buildings, plus 5 dining options), featuring distinctive Vermont clothing, crafts, antiques, and fine sporting apparel.

WOODSTOCK

Collective: The Art of Craft Gallery featuring handwrought home décor, clothing, jewelry, and fine art in a variety of media, including glass, fiber, pottery, metal, wood, and paper. Housed in a