Our Seattle sailing school, located at Shilshole Bay Marina on Puget Sound, offers top-notch instruction on the best fleet. With stunning views of the Olympic Mountains and quick access to open water, we provide hands-on training and personalized feedback to help you master sailing essentials.

For less than the cost of moorage at scenic Shilshole Bay Marina, a Seattle Sailing Club membership gives you full access to our sailboat fleet. Members also enjoy discounts on sailing lessons and gear, plus the chance to join exciting member programs around Puget Sound.

Seattle Sailing Club offers a toptier selection of essential sailing gear for any Puget Sound sailor. We carry trusted brands like Gill, Dubarry, Grundens, and Mustang Survival, along with a range of sailing books, charts, cruising guides, and navigation tools.

Zeus S is the next generation of chartplotter. Available in designed specifically to make sailing easier, giving you all the easy-to-interpret way. Experience enhanced sailing features, detailed C-MAP® charting for the safest, easiest navigation.

a Sailing situation. charts feature options current plotting, autorouting. tides,

With its unique Sailing Modes, Zeus S is the next generation of chartplotter. Available in three sizes (7”, 9” & 12”), it’s designed specifically to make sailing easier, giving you all the information you need in an easy-to-interpret way. Experience enhanced sailing features, a new, intuitive interface, and clear, detailed C-MAP® charting for the safest, easiest navigation.

See the data you need, when you need it in a simple and clear display. Choose from Sailing Modes for Cruising or Racing and get all the relevant information you need for that situation.

Improve your sailing with easy to interpret pointers from B&G®’s award-winning sailing features for cruising and racing, with updates to SailSteer™, Laylines, StartLine, Routes, Racing and many more. C-MAP powered Safety Alerts guard against grounding and dangerous objects.

C-MAP DISCOVER™ X and REVEAL™ X charts feature highly accurate data with simple viewing options for clear and easy navigation. Tide and current projections improve trip planning and route plotting, further supported by our fastest-ever autorouting. Plus, get quick, one-touch access to POIs, tides, channels, and more.

Zeus S makes data easy to read, and even easier to digest. The interface is designed to feel familiar – with a new Set-up Wizard to get you started, and helpful feature tips to guide you along the way. Get hassle-free software updates, on- and offthe water trip planning, and clear, accurate chart displays across your Zeus S, App and Web.

innovative B&G marine electronics please visit fisheriessupply.com/b-and-g-electronics 1900 N. Northlake Way, Seattle FisheriesSupply.com

With its unique Sailing Modes, Zeus three sizes (7”, 9” & 12”), it’s designed information you need in an easy-to-interpret a new, intuitive interface, and clear, detailed

Improve your sailing with easy to interpret pointers from B&G®’s award-winning sailing features for cruising and racing, with updates to SailSteer™, Laylines, StartLine, Routes, Racing and many more. C-MAP powered Safety Alerts guard against grounding and dangerous objects.

See the data you need, when you need it in a simple and clear display. Choose from Sailing Modes for Cruising or Racing and get all the relevant information you need for that situation.

Zeus S makes data easy to read, and even easier to digest. The interface is designed to feel familiar – with a new Set-up Wizard to get you started, and helpful feature tips to guide you along the way. Get hassle-free software updates, on- and offthe water trip planning, and clear, accurate chart displays across your Zeus S, App and Web.

Detailed C-MAP® Charts C-MAP DISCOVER™ X and REVEAL™ X charts feature highly accurate data with simple viewing options for clear and easy navigation. Tide and current projections improve trip planning and route plotting, further supported by our fastest-ever autorouting. Plus, get quick, one-touch access to POIs, tides, channels, and more.

For the complete line of innovative B&G marine electronics please visit fisheriessupply.com/b-and-g-electronics

For the complete line of innovative fisheriessupply.com/b-and-g-electronics

Michael Boyd

By Ryan Samantha Carson

Bruce Bateau

Dennis Bottemiller

Mighetto

The smell of hot dogs wafted through the cockpit from the grill on our boat’s stern, and laughter rang out from friends sitting on the side deck and perched on the cabin top after a sappy joke. We were making way, but the sails were working hard just to stay filled in the light southerly breeze.

Sailing slowly westward across Puget Sound on a pleasant October afternoon, we weren’t just out for an average day sail with friends. We were racing our house against other liveaboards, and the entertainment on each boat seemed to be equally festive. One house blared music and appeared to be throwing a dance party. Two other boats sailed in tandem, and threw cookies and cold beverages back and forth as we all neared a turning mark off Bainbridge Island’s Point Monroe.

After finally inching our way around the mark, the once fickle wind began to build, causing the racing sailor in me to perk up. I called for our asymmetrical spinnaker to be hoisted, and we sailed on a tight reach back across the Sound, towards Meadow Point, and then through the finish line off of Shilshole Bay Marina. With high fives from the crew, we celebrated and talked about what place we thought we came in. It didn’t really matter. Bragging rights are nice, but that’s not the point. It was another fun Race Your House put on by the Sloop Tavern Yacht Club, and we celebrated accordingly that evening with our fellow racers.

A few weeks later, I was back on the race course again, this time sailing around the San Juan Islands in the infamous Round the County race. As part of the crew on a well-sailed J/145, we were pushing hard to windward in a building breeze after starting in Rosario Strait. Salt spray soaked the crew on the rail and, at my position trimming the mainsheet, my hood wasn’t doing much to keep the rain from finding its way in. In quiet contemplation and focus, there was very little talking going on and certainly no laughter. We were doing well against the competition and I could sense that everyone was keen on grabbing a victory on day one. Well, that, and the reward of hot showers and cold beers at Roche Harbor.

The second day of this counterclockwise contest around the islands was completely different. Light, shifty breezes and contrary currents made it difficult for everyone. Yet, it was fun to figure out the puzzle, the weather was sunny, and the mood had more of a bounce to it and less intensity. With the bottom end of Lopez Island behind us, we snuck by a few boats near Watmough Bay, and then played the Decatur and Blakely Island side to make a strong finish. We didn’t win overall, but we made the podium and had a lot of fun doing it.

Race Your House and Round the County are two of my favorite events in the Salish Sea, and what I love is how vastly different the experiences are. That’s part of what makes sailboat racing—or just being on the water—in the Pacific Northwest so special. There are as many ways to enjoy it as there are friendly folks to share it with. Where else can you race your house one weekend, and then another weekend do an epicly demanding and competitive distance race around an amazing island chain—all with some of your best friends? So racers, remember how special those moments are when you get out there this fall, because they’re certainly priceless.

Fair winds,

Volume XLIV, Number 3, October 2024 (206) 789-7350

info@48north.com | www.48north.com

Publisher Northwest Maritime

Managing Editor Joe Cline joe@48north.com

Editor Andy Cross andy@48north.com

Associate Editor Deborah Bach

Designer Rainier Powers rainier@48north.com

Guest Designer Karen Johnson

Advertising Sales Ryan Carson ryan@48north.com

Classifieds classads48@48north.com

Photographer Jan Anderson

48° North is published as a project of Northwest Maritime in Port Townsend, WA – a 501(c)3 non-profit organization whose mission is to engage and educate people of all generations in traditional and contemporary maritime life, in a spirit of adventure and discovery.

Northwest Maritime Center: 431 Water St, Port Townsend, WA 98368 (360) 385-3628

48° North encourages letters, photographs, manuscripts, burgees, and bribes. Emailed manuscripts and high quality digital images are best!

We are not responsible for unsolicited materials. Articles express the author’s thoughts and may not reflect the opinions of the magazine. Reprinting in whole or part is expressly forbidden except by permission from the editor.

SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS FOR 2024!

$39/Year For The Magazine

$100/Year For Premium (perks!) www.48north.com/subscribe for details.

Prices vary for international or first class. 48º North

Proud members:

48° North has been published by the nonprofit Northwest Maritime since 2018. We are continually amazed and inspired by the important work of our colleagues and organization, and dedicate this page to sharing more about these activities with you.

Maritime High School (MHS), a public choice school in the Highline School District operated in partnership with Northwest Maritime, Port of Seattle, and the Duwamish River Community Coalition, recently announced the expansion of its maritimefocused curriculum with the addition of a third educational pathway, Marine Construction. This new endeavor will be made available to students entering grade 11 beginning with the 202425 school year. Other educational pathways students can explore include Marine Resources & Research, and Vessel Operations, Design, and Maintenance.

In grade 11, students at MHS are encouraged to select one of the three educational pathways, each of which yield college credits. In selecting Marine Construction, students will participate in a two-year program dedicated to mastering marine welding and shipyard skills. This will provide them with the opportunity to receive hands-on shipyard training and earn a maritime shipyard welding certificate. Teachers, mentors, and industry professionals will provide a well-rounded education, plus the industry certifications necessary to jumpstart future career paths.

Students enrolled in the Marine Construction pathway will spend part of each day at a training center located at Seattle’s Harbor Island Shipyard and Training Center, which is jointly operated by Vigor Industrial Shipyards and South Seattle College. This pathway is funded through Running Start and funds raised by Northwest Maritime.

The Marine Construction program aims to bolster Seattle’s maritime industry by preparing graduates who are well-equipped to meet the demands of this thriving field. The new program marks the third pathway now being offered to MHS students, following the success of the Marine Resources & Research, and Vessel Operations, Design, and Maintenance learning pathways.

The two-year Marine Resources & Research pathway integrates math, English, and marine science, with mentorship and work experiences through Highline College.

The Vessel Operations pathway allows 11th and 12th graders to complete Seattle Maritime Academy’s Marine Engineering Technology Program, earning college credits and industry recognized credentials.

When not participating in off-campus training and learning experiences, juniors and seniors in all three pathways work with MHS instructors on complementary projects, with a blend of academic and hands-on learning opportunities. MHS prepares its graduates for maritime careers or postsecondary education opportunities. Students graduating from MHS will have the knowledge and credentials to enter the maritime industry earning an initial annual salary between $60,000 to $80,000.

“At Maritime High School, we are dedicated to providing our students with the skills and knowledge they need to excel in maritime careers. Our expanded curriculum, including the new Marine Construction pathway, ensures that our graduates are well-prepared to meet the growing industry demand for skilled professionals,” said Maritime High School Principal Jamila Gordon. “We are committed to shaping the future of the maritime workforce and providing our students with unparalleled opportunities for success.” Maritime High School is currently accepting students entering grades 9-11. The school is open to any student who is interested in maritime studies, whether they live within Highline Public Schools boundaries or not. To learn more or apply to attend Maritime High School, visit » maritime.highlineschools.org

But you need it beneath you, as the wind lets you fly across the horizon, to beat the others across the finish line.

WarpSpeed® 3 SD will help you go even faster. When every ounce counts, from the core to the cover, pSpeed 3 SD with SamsonDry® Technology will prevent water absorption, keeping your ropes light and fast.

SamsonRope.com

Cruisers College, the boat-ownerspecific marine technical education offered through Skagit Valley College, is gearing up for another great season of hands-on learning. Are you interested in acquiring the skills to maintain your vessel effectively? How about gaining the confidence to identify and address potential problems on your boat, making you more self-reliant and assured while on the water?

Cruisers College was created in 2016 to provide high-quality marine courses for boat owners to do just that. It is run as a part of Skagit Valley College’s (SVC) Marine Technology Center in Anacortes. Cruisers College spun off from SVC’s professional technical program, which offers extensive training for new marine technicians and would be great material for boat owners, but the 12-week course

schedule proved challenging for the average recreational owner. This month, Cruisers College is excited to announce its course schedule for the rest of 2024.

Cruisers College courses take place on weekends and are led by industry professionals who are passionate about sharing their extensive knowledge and experience. Offered in a world-class marine training facility, there’s ample opportunity for demonstrations and hands-on activities. It is fitting to seek out this kind of education in Anacortes, a town with a rich maritime industry history that is even more vibrant today.

Cruisers College’s schedule for 2024 includes a variety of hands-on courses that allow you to apply your newfound knowledge in practical labs. This season’s first courses kick off October 19-20, and run through November and December.

• Marine Canvas for Cruisers, October 19-20

• Outboard Motor Service, Repair, and Maintenance, October 26

• All About Plumbing, Marine Sanitation, and Water Makers, October 27

• Cruising Boat Electrical Basics Workshop, November 2

• Making Your Own Upholstery, November 9

• Marine Canvas “Makers Space” by Mike Reese, November 10

• DIY Diesel Engine Maintenance and Troubleshooting, November 16

• Women’s Only Marine Electrical Basics Workshop, November 17

• Canvas: All About Covers, December 7

• Marine Canvas “Makers Space” by Mike Reese, December 8

• Marine Diesel Engines Weekend for Women, December 14-15 » www.cruiserscollege.org

October is here, which means avid sailboat racers in the Pacific Northwest have a jam-packed schedule of events to look forward to. Here are some of the highlights to get your boat and crew out on the water for some friendly competition:

CYC Edmonds Foulweather Bluff Race, October 5: Hosted in partnership with Kingston Cove Yacht Club. Mid-distance race with three condition-dependent course options of approximately 24, 14, or 10 miles. Start/finish at Apple Cove Point at Kingston. » cycedmonds.org (48° North Top 25 qualifying event)

South Sound Sailing Society Eagle Island Race, October 12: Join fellow South Sound racers for this out and back race starting at Olympia Shoal. Long course and short course options available. » ssssclub.com

CYC Seattle Puget Sound Sailing Championship (Big Boats), October 12-13: A weekend of buoy competition and fun for PHRF, ORC, and one design classes on the waters near Shilshole Bay. » cycseattle.org (48° North Top 25 qualifying event)

Sloop Tavern Yacht Club Race Your House, October 19: Bring your boat and race for bragging rights of Puget Sound liveaboards! A seriously varied fleet that is always a good time. » styc.org

Sloop Tavern Yacht Club Great Pumpkin Race, October 20: Great fall racing action with a reverse start, long and short courses, and classes for non-flying and flying sails. » styc.org

Seattle Yacht Club Grand Prix Regatta, October 25-27: An autumn tradition on Puget Sound, not to be missed. Open to PHRF, ORC, and one design classes. A mix of buoy and middistance racing over three days makes this one of the best regattas of the year. » seattleyachtclub.org (48° North Top 25 qualifying event)

Designing and building Bluewater Cruising Sails for adventure since 1978. Whether you are heading to northern latitudes, the South Pacific, the Caribbean, or in between we design a custom sail inventory for your vessel, and then work with you and your cruising kitty to help your dreams manifest. Give us a call.

Port Townsend Sails Hasse & Co. 919 Haines Place PT, WA 360-385-1640 www.porttownsendsails.com contact@ptsails.com

By Laurence Holt

There’s almost no better activity on a starlit night than to lay on the foredeck learning about stars, constellations, and planets. If you’ve ever looked up at the night sky and wanted to point out a constellation to family and friends, tried to find the Milky Way, wondered how to navigate by the stars, or just wished you knew more about what’s out there, then Stikky Night Skies is for you. It uses a unique learning method, honed through hundreds of hours working with test readers, to bring a fascinating topic to anyone with a little time. In just an hour, you’ll know six constellations, four stars, a planet, and a galaxy, and how to navigate at night. You’ll be able to step outside when the sun sets and apply what you’ve learned—right away.

» www.stikky.com Laurence Holt Books, Inc, Price: $12.00

By Syd Stapleton

Marine West (Distributor) 400 Harbor Dr, Sausalito, CA 94965 415-332-3507

Set against the backdrop of the San Juan Islands and Anacortes, Troubled Waters follows a marine surveyor, Frank Tomasini, who lives comfortably on his 1937 salmon troller, the Molly B. When Frank is asked to unofficially survey the damage to a boat found adrift and abandoned near San Juan Island, he learns the owner, Arthur Middleton, a rich and holier-than-thou environmental warrior, has disappeared. His boat, the Sound Avenger, may have been sabotaged. Ironically, the only thing that kept it from sinking was a bit of floating trash, which blocked enough water from getting in to keep it afloat. A cast of island characters follows a trail that winds through a dive bar full of salty locals, a dying fish farm, a wreck-filled marina, and more to solve the mystery. Locals will recognize old haunts such as Marine Hardware and The Brown Lantern as they follow this page-turner. Troubled Waters is currently available for purchase on Amazon.

» Marline Publishing, Price: $18.99

Emerald Marine Anacortes, WA • 360-293-4161 www.emeraldmarine.com

Oregon Marine Industries Portland, OR • 503-702-0123

info@betamarineoregon.com

Access Marine

Seattle, WA • 206-819-2439

info@betamarineengines.com www.betamarineengines.com

Sea Marine Port Townsend, WA • 360-385-4000

info@betamarinepnw.com www.betamarinepnw.com

Deer Harbor Boatworks Deer Harbor, WA • 844-792-2382

customersupport@betamarinenw.com www.betamarinenw.com

Auxiliary Engine 6701 Seaview Ave NW, Seattle WA 98117 206-789-8496

auxiliaryeng@gmail.com

Boatbuilding & woodworking classes for all skill levels at the Northwest Maritime Center.

Boatbuilding & woodworking classes for all skill levels at the Northwest Maritime Center.

Learn more at nwmaritime.org Water Street, Port Townsend, WA 360.385.3628 | info@nwmaritime.org

Learn more at nwmaritime.org 431 Water Street, Port Townsend, WA 360.385.3628 | info@nwmaritime.org

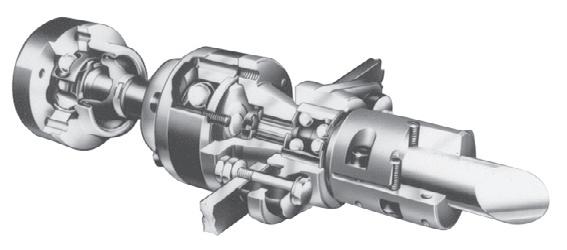

Business or Pleasure, AquaDrive will make your boat smoother, quieter and vibration free.

The AquaDrive system solves a problem nearly a century old; the fact that marine engines are installed on soft engine mounts and attached almost rigidly to the propeller shaft.

The very logic of AquaDrive is inescapable. An engine that is vibrating

on soft mounts needs total freedom of movement from its propshaft if noise and vibration are not to be transmitted to the hull. The AquaDrive provides just this freedom of movement. Tests proved that the AquaDrive with its softer engine mountings can reduce vibration by 95% and structure borne noise by 50% or more. For information, call Drivelines NW today.

by Bryan Henry

An unnamed mountain lying in the Pacific Ocean in a trench between Samoa and New Zealand is the world’s tallest completely submerged mountain. It’s 28,500 feet high, but its peak is 1,200 feet short of the surface.

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a mountain range stretching 10,000 miles under the Atlantic Ocean, is longer than the Himalaya, the Andes, and the Rockies combined.

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge wasn’t directly seen or explored until 1973, four years after astronauts first walked on the moon.

A water molecule is only one eighteen-billionth of an inch in diameter.

Salinity of the oceans averages about one-half ounce of salt per pound of seawater.

1 Christopher Cross song

6 Closing device

9 Fishing equipment

10 They support sails and rigging

11 Light rope

12 Length of a cable extended when a ship rides at anchor

15 Fine dining expert

16 Row boat need

17 “I’m so glad!”

19 Compass point, abbr.

20 Principal banner or flag flown by a ship

23 West coast port, for short

24 Man cave, maybe

26 Deck covering the hold

28 Type of barometer

30 Crack, so to speak

32 Slang term for autopilot, 2 words

34 Location indicating word

35 Edwardian, e.g.

37 Beach

38 Lighting’s discharge

» See solution on page 51

1 Vertical post used to fasten the anchor cable or mooring warps

2 Blowing from the sea to the land

3 Allow

4 The “I” of T.G.I.F.

5 Areas on ships used for cooking or preparing food

6 Part of a dock

7 “Tempest in a ___ ___” - 2 words

8 Concealed

13 Preserve, in a way

14 Closed loop at the end of a line, rope or cable, 2 words

18 “Go on”

21 Charged particle

22 Hawaiian wreath

24 Moored

25 Bismarck’s state, abbr.

27 Bring a vessel into the wind and hold her stationary, 2 words

28 Change the course of a ship by tacking

29 Wood used for furniture

31 Cheerleader’s cry

33 Before, in poetry

36 Rogers’ state, abbr.

The oldest rocks found on the ocean floor are 180 million years old, young compared with the oldest continental rocks, dating from 3.8 billion years.

If you dropped a heavy rock into the ocean over the world’s deepest spot, the Mariana Trench in the Pacific Ocean, it would take more than an hour to reach bottom.

Oysters are the most profitable mollusks that are farmed.

A female oyster can produce more than 100 million eggs at a single spawning.

As many as 1,000 different fish produce light in the deep oceans.

Some deep-sea shrimp emit light from their mouths to blind or distract predators, allowing the shrimp to escape into darker water.

The longest bony fish in the ocean is the 25-foot-long rare oarfish that can weigh more than 600 pounds.

Flounders and rays are the only fishes to have both eyes on one side of their bodies.

There are about 55,000 species of sea snails found worldwide.

Some sea anemones can live as long as people—up to 70 years or more.

Whether it’s sailing, kayaking, or rowing, having a quality dry suit for the cold waters of the Pacific Northwest can be a must-have for staying dry, comfortable, and safe. In that vein, Mustang Survival recently launched its Quadra Dry Suit. This brand-new minimalist, multipurpose dry suit is designed for those who enjoy shorter-duration water activities and is available in men’s and women’s versions. The Quadra Dry Suit features the same tough and durable threelayer Marine Spec BP fabric used in Mustang Survival’s other dry suits, with a design inspired by the gear the company has innovated for military and public safety agencies, and subjected to the same comprehensive testing. The Quadra’s waterproof and abrasion-resistant fabric holds up in challenging saltwater environments, and the trimmable latex neck and wrist seals provide maximum protection and comfort. A waterproof YKK® AQUASEAL® zipper makes for easy donning and doffing, and every suit undergoes comprehensive leak testing to ensure superior performance and reliability.

Price: $849.99 » www.mustangsurvival.com

For many types of isolated fires, including on boats, smothering is an effective suppression technique—except if a lithiumion battery is burning. The LiCELL SB Series Fire Blanket from Sea-Fire Marine is specifically engineered to withstand extremely high temperatures for prolonged periods, as well as contain expelled debris and shrapnel commonly encountered with lithium-ion battery fires. The LiCELL SB Series Fire Blanket is incapable of igniting, and is independently tested and verified for prolonged direct flame contact and use at temperatures up to 2,552° F. Reusable, it's ideal for refractory flame deflection and suppressing multiple lithium-ion battery fires. Foldable and easy to store, the LiCELL SB Series Fire Blanket is manufactured using a fully oxidized woven fabric with a high silica glass fiber content and includes a storage bag. Integrated handling loops make the device simple to deploy. Sea-Fire's LiCELL SB Series Fire Blanket comes in four sizes: 6-foot by 6-foot, 9-foot by 9-foot, 12-foot by 12-foot, and 19-foot by 26-foot.

Price: $1,199.99 to $3,999.99 » www.sea-fire.com

Solar panel shading is a major issue on almost every cruising boat, and can reduce a standard panel’s performance by over 60%. Custom Marine Products has developed a series of semi-flexible, shade-tolerant solar panels that have superior performance when partially shaded by boat equipment or nearby objects. These solar panels use high performance SunPower Maxeon 3 A+ cells, and the new design enables the panel to have four quadrants of solar cells linked in series and isolated with diodes. If one or two quadrants are shaded, the other quadrants perform at normal output. The result is a panel that will provide up to three times the output of a standard panel when shaded. These shade tolerant panels are ideal for bimini and dodger mounting where there is boom, mast, and instrument pole shading.

Price: $639 to $1,049 » www.custommarineproducts.com

By Bruce Bateau

“Didn’t you get lost?” a visitor asked me at the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival, after I told him that I navigate only with paper charts. He’d been in the audience at my presentation about a journey through the Inside Passage in an 18-foot sail and oar boat.

“Well, I had the goal of always knowing where I was,” I replied, hoping I sounded confident, rather than cocky. “So, I looked around all the time, triangulating and observing the landscape.”

He looked me over carefully. I wondered if he was evaluating my sanity, but in the end, I didn’t care what he thought. Not only was I still here to tell the tale, but my decision to navigate the old-fashioned way was based on sound reasoning—and it worked.

In an age when virtually everything is available via smartphone, chart plotter, or home computer, sometimes it can feel unnecessary even to leave the house (or the nav station). After all, someone else has not only already discovered your

destination, but they’ve captured it for you in a photo, video, or map. I like computers. I think they’re one of humanity’s most useful inventions (even when I’m using mine to watch cat videos). But one of the reasons I got excited about small craft was the ability to get away from it all and leave the electronics behind.

When I first started boating, I daysailed and rowed on rivers. It was pretty hard to get lost, since I never went too far from where I started, and I never moved very fast. Returning to the boat ramp was as easy: just follow obvious landmarks along the shore.

When I started going farther afield for overnight trips, beginning in the south portion of the Salish Sea, navigating became more complex. Now it was no longer a question of up or down the river, so I began to buy maps. Yes, maps. In the time before smartphones, my local kayak shop sold “Fish-nMaps.” These protocharts were advertised as waterproof and tearproof, and they folded down to a 4-inch by 9-inch rectangle. Using one, it was easy to navigate from Olympia to Seattle. All for just $7.95.

A convenient size for a small boat, Fish-n-Maps showed landmarks, boat ramps, depths, all major landforms, and tidal areas. True, on the Fish-n-Map scale, one inch equaled about a nautical mile (1:66,700). But in a boat that could float in only a few inches of water, the maps provided a guideline for true

adventure and discovery; using one, you could explore the edge without falling off it. I found that they actually worked for my needs and that I liked navigating with a map and compass.

As I ventured farther north into the less familiar, and more rocky, unforgiving waters of the San Juans and Gulf islands, I read books about navigation and, through a lot of practice, I learned how to identify the edges of landforms from afar. I also acquired more sophisticated NOAA- or Canadian Hydrographic Service-authorized charts printed on thick, waterproof paper. Larger in scale, more detailed, and beautifully illustrated, they were awkward to handle in a boat with a 5-foot beam. I sometimes imagined that, in a pinch, they would be lashed to my spars and used as a storm sail. Still, I found ways to fold them into useful accordion-like shapes and sizes, enabling me to flip them as I moved through days of cruising. I loved how the islands revealed themselves as I progressed, transforming the shapes on each chart from flat drawings into familiar landscapes.

My navigation station consisted of a direct read, portable compass that could be moved when rowing or sailing, my proper nautical charts, and a pair of water-resistant binoculars. Aided by paper tide and current tables, a digital watch, a Rite in the Rain log book, and a pencil, I had the tools I needed to navigate a small boat through typical spring and summer conditions.

Along with these charts, I began carrying a GPS unit that I strenuously avoided using. Historic mariners, I told myself, had far less to go by, and even small craft users as recently as the 1990s did what I was doing, and they mostly survived, right? Nevertheless, I continuously made mental notes of my speed, of how long I’d been on the water, my current compass bearing, and what landmarks were in view. Out sailing, I felt fully immersed. Between adjusting sails, looking for marine traffic, identifying floating hazards, and what I now know as dead reckoning, I consistently made it where I wanted to go.

Did I ever get lost? Sure. But these were mostly minor incidents, when I mistook one headland or bay for another. In my years of voyaging over thousands of miles, I’ve only used the GPS unit three times. It’s convenient, close at hand, and

Good planning with a chart and guidebooks is important to successful navigation.

impressively accurate; but I resist its use because it’s too easy to reach for it. GPS in hand, the game is over; all the learning of the coastline is gone, all the attention to detail is slackened, the focus on the seascape shifts to a tiny triangle on a glowing screen. I try to think of the location button not as a last resort, but as a consultation with a trusted professor.

On one of the few occasions that I used my GPS, I was engulfed in fog after crossing from the United States into British Columbia. “I believe I am north of Gooch Island, approaching Fairfax Point on Moresby Island,” I whispered to myself before peeking at the screen. Sure enough, that’s pretty much where I was—thankfully not in the shipping lanes. An external source of validation calmed the captain and crew, even as we continued blindly until we could see the shore. On the other two occasions, I used the locate feature out of desperation, late in the day while winding through clusters of islands farther north, where my margin of safety to find an anchorage was running too thin.

The author using binoculars to pick out a familiar object ashore.

These incidents reinforced my feeling that it’s one thing to play a game, to build a skill; it’s another to risk one’s life, or worse, to put others in danger through foolish resistance to using a tool. Still, for the vast majority of the time, my paper charts work for me, allowing me to learn from observation, and to be engaged and fully involved in sailing and the landscape around me. My methods may be old-school, but they’re satisfying—and isn’t that what we’re all looking for on the water?

Author’s note: Each boater needs to choose their own level of risk and reward, along with the tools that bring them satisfaction and safety on the water. I sail small boats, where grounding or getting lost is often of little consequence. Since I usually sail solo, there’s a lesser chance of involving others, should a problem occur. In a deeper draft and/or a faster vessel with crew, my approach might be very different.

Bruce Bateau sails and rows traditional boats with a modern twist in Portland, Oregon. His stories and adventures can be found at www.terrapintales.wordpress.com.

By Dennis Bottemiller

We arrived at Latimer’s Landing near the Harstine Island Bridge right at high tide. Our C-Dory 22, Sea Lab, was in tow to begin this summer’s boat vacation in the South Sound. This was only the second time we have put the boat in here, and launching a boat from a trailer still isn’t my forte.

At high tide, the distance between the launch ramp and the float at Latimer’s Landing is long, and the gangway down to the float is very high off the water, so pushing the boat off the trailer and getting it to the float is difficult. Plus, there is current from Pickering Passage to contend with, not to mention the rocky shoreline looming just off the ramp. We stood on the gangway and watched several other launches and retrievals, and the common method seemed to have a person in the boat start the engine and drive off the trailer and dock the boat while the trailer driver pulled out to park.

There were a couple of problems that arose for us using this launch method: One, my wife, Tekla, had never docked any of our boats, neither sail nor power; and two, Tekla had never driven the truck with a trailer attached. So, we tied two lines together and she held onto it as I backed the boat down, unhooked the bow strap, and pushed Sea Lab into the water. Though not very

graceful, it worked okay. Sea Lab did a 180-degree spin in the current while Tekla clung to a piling. Fortunately, there were no spectators, and she was able to get our lightweight little cruiser under control and tied up while I put the trailer up in the lot.

Everything was ready to go, but before we shoved off, I had to address the inspiration brought on by our launching challenge. I asked Tekla what she thought about making this cruise all about her learning to run the boat. She gave me a sideways look and reluctantly agreed with a, “Maybe.”

We stayed at the float while we discussed the merits of this idea, and we agreed that her getting experience at skippering Sea Lab would be exceptionally valuable for our time on the water, and an important safety measure. So, we set off with Tekla at the helm, and me untying and stepping aboard as she gave the word and shifted into gear. We were away!

Tekla and I have been boating together since our first little sailboat 23 years ago, and for some reason we have never come to this point. We have thought about it. We’ve read stories in which the skipper becomes incapacitated and another person on board doesn’t know what to do. I even know someone who fell off his boat untangling fishing gear and watched it motor

away with his father, who had no idea how to run his boat. What a feeling that would be! Miraculously, he was spotted in the water and rescued by the crew of a B.C. ferry, and everything turned out all right.

I suppose there had always been some reluctance on Tekla’s part to run the boat for fear of what might happen in scary situations. There might have been some reluctance on my part in giving up some responsibility and manly authority. Silly me. We both felt good about this decision and Tekla turned Sea Lab’s bow up Pickering Passage toward the destination for our first night on board—Jarrell Cove State Park.

It was a short 3-and-a-half mile run to the cove, and we left no wake through the mooring buoys and anchored boats pulling up to the state park dock. There were only two other boats tied up, which left plenty of room for a first-time docking

maneuver, and high tide meant the channel between dock and shore was plenty wide. Tekla swung wide, pointed up to the dock, and made a perfect landing as I stepped off and tied the midship cleat. She turned the motor off, powered down the electronics, and logged the time, then we shared a big high-five in celebration of her first landing. Before long, our friends Rob and Tracy on the Blue Pearl joined us to have a collaborative dinner and while away the evening in the environment we love best—boating in the Pacific Northwest.

During the evening, we worked on our itinerary for the week, and settled on heading for Swantown Marina in Olympia the next day. None of us had ever been there and Olympia Harbor Days, with the tugboat races, was happening downtown. Tekla called the marina in the morning and, sure enough, there were three slips open on the guest dock with our names on them when we arrived; one for Sea Lab, one for Kingfisher who was to join us there, and one for Rob and Tracy’s “Blue Curl” as the name was entertainingly misheard over the phone. Alan in Kingfisher arrived first, with Tekla and I arriving an hour or so later. Skipper Tek navigated an unfamiliar marina entrance with me looking through binoculars for the way in. Again, a perfect landing and with Alan to catch our lines, we were tied up in no time, boosting confidence in our boat handling skills.

It turns out we had been missing out on a great destination. Swantown is a beautiful and well-run marina, and the whole downtown area of Olympia is accessible on foot, including the impressive farmers market, numerous parks, and restaurants galore. Our group’s plans for the near future include returning for a weekend cruise at Swantown to more fully explore the delights of this town.

Again, our destination planning occurred over dinner and drinks on the dock. Rob had been extolling the virtues of a tiny bay named Carlson Bay on the chart, on the southwest side of Anderson Island, just below Treble Point. “The most beautiful

beach in the South Sound,” he said. I looked for it in Waggoner guide … nothing. So, I pulled out the trusty old gunkholing book (one of my favorite books of all time!) and found a twosentence description beginning with the phrase, “Tiny, drying and not suitable as an anchorage.”

But the following entry says, “Anchoring is possible outside the little bay if it is calm,” and so our next destination was set. The weather was forecast to be calm with a light breeze from the north, so it seemed like the perfect time to try it.

After a leisurely morning, we checked out of our slip. I manned the dockline duties, and Tekla backed out and turned easily into the fairway to wend our way to the fuel dock to practice landing

and launching one more time before leaving Swantown. Well, and to get gas and ice, of course.

We all left at our own pace and set our rendezvous for “late afternoon,” and we headed off for Dana Passage and Nisqually Reach. Lollygagging our way past Johnson Point, we turned our motor off and drifted on the current for a while, and had a bit of lunch. Drifting on the current is something we never did in the sailboat, but we do it often aboard Sea Lab when the water is calm. There is something special about watching the water and all the life that depends on it while we just float by, enjoying the calm weather and not having to do anything.

Tekla and I arrived first at Carlson Bay and Rob was correct: it is a fabulous beach. It also happens to be public land. The nearby water is shallow, and we dropped anchor and waited for the other two boats to arrive. Kingfisher was next, and he pulled alongside and I hopped on board to help Alan get his anchor set away from ours. We backed down and were well set, rafted to Sea Lab, and cracked a cold one. In a short while, Blue Pearl showed up and rafted with us, and we broke out the dinner supplies and whipped up another fine meal.

After dinner, we hopped in the dinghies and went to shore to see the bay behind the gravel bar. The high water was flowing out the entrance of the bay with such force that we could not row against it, so we had to land on the outside beach instead. It was a perfect evening, and the western sunset glow lit up the madrona-forested bluffs. This really is a wonderful spot, and it feels remote even though it is very close to civilization. The anchorage felt exposed, so we decided to split up the raft and anchor individually for the night in case any weather blew in unexpectedly. It didn’t, and we had a peaceful, quiet night. There weren’t even any boat wakes to interrupt our sleep, and no ferry traffic.

Tekla and I only had one more night to be out and we all decided to spend it in the bay to the north of McMicken Island, which is one of our favorite spots. Again, we all split up and went at our own pace. We made a stop at Joemma Beach State Park on our way to give Tim Tim, the sailor dog, a little break and Tekla some more docking practice before proceeding on. When we arrived, Kingfisher had procured a multiboat buoy, so we pulled alongside and fendered up for the night, and soon Blue Pearl followed suit. We dined, swam, drank beer, and were flabbergasted by spotting a Starlink deployment in the western sky at twilight. It was yet another wonderful night aboard with our raft of friends.

On our way down Pickering Passage, heading back to Latimer’s Landing and our pullout the next day, I reflected on what a valuable trip this had been. Not only had we visited places we had never been before and added a few new pages to our story of shared adventures with friends, but Tekla and I had really strengthened our boating experience with learning new skills. It made our little vessel safer and more capable, and deepened our relationship with new trust in each other. All of that is priceless.

Dennis, Tekla, and their sailor dog Tim Tim have recently changed their home cruising waters from Tacoma to Case Inlet at Grapeview, and are excited to explore the South Sound in greater detail.

Recently I met a boater who cruised a 32-foot Sea Ray from Seattle to Cortes Island, British Columbia, and back in one day.

“Did you stop for dinner in Roche Harbor?” I joked. “How about cocktails in Nanaimo? Did you harvest any oysters?”

Speed was the point of his 400-plus mile trip, and as a boater who once spent an entire day going through customs in B.C. with my vessel, I was amazed at his navigational and logistical skills. My experience boating at Cortes Island last summer was very different, requiring a lengthy border crossing by car at the Peace Arch, three ferries (Tsawwassen, Campbell River, and Heriot Bay), and a road trip up the coast of Vancouver Island.

by Lisa Mighetto

Located at the entrance of Desolation Sound in the northern reaches of the Salish Sea, Cortes Island is a destination requiring patience and persistence, especially when leaving from Seattle or Vancouver. It took me two full days to drive there. And the three small inflatable boats my husband, Frank, and I brought ensured that we were going nowhere fast, at least on the water.

Over the years we have ventured to Desolation Sound in a 26foot sailboat, a 42-foot trawler, and various commercial vessels. Yet, last summer when we stayed in a cabin in the woods with our inflatables, I felt like I was seeing it for the first time.

“Dammit! Please Slow Down,” read the sign at the entrance to Cortes Bay, located on the southeastern side of the island. Referring to boat wakes, the message nonetheless seemed like words to live by. As we puttered, rowed, and paddled along the shoreline, Frank and I quickly fell under the island’s spell, appreciating the relaxed pace and noticeable quiet that our small boats provided. I thought about Carl Honoré’s book, In Praise of Slowness: How a Worldwide Movement is Challenging the Cult of Speed (2004), which recommends quality over quantity and the joy of living in the moment. The slow movement is a global initiative stemming from the slow food movement, which calls for mindful preparation with simple, locally sourced ingredients.

“Why not slow boating?” I asked Frank.

Speed has its place when you’re trying to reach a destination during limited vacation time or trying to outrun a storm. It’s also great fun to fly across the water, especially in a race. It’s essential if you’re waterskiing. But there’s something to be said for an unhurried and thorough exploration of an area in a small vessel.

Before this trip, Frank and I had logged many hours in our dinghies, traveling to shore or visiting another anchored boat, occasionally stopping to admire a beach or point of interest. When the only boat available is a small inflatable, however, your perspective changes.

No one understood the value of small and slow better than Muriel Wylie “Capi” Blanchet, author of the beloved memoir The Curve of Time (published in 1961). During the 1920s and 1930s, she cruised Desolation Sound on a 25-foot boat with five children and a dog. The definition of “small” can be debated, but it seems Blanchet’s vessel Caprice qualified. The family meandered through coves and inlets for months, getting “lost somewhere down the centuries.” The “winding channels lured and beckoned,” she explained. “That was what we had been doing … just letting our little boat carry us where she pleased.”

For our first tour of Cortes Island, Frank and I chose our rollup inflatable equipped with a 1.7-horsepower EP Carry electric outboard. We launched from Cortes Bay on a calm, sunny morning, following the shoreline and turning south at the entrance. At one point we stopped along a cliff that dropped straight down into the clear water. Maneuvering up to the wall, we admired the bright purple hues of the ochre sea stars clinging to the side while multiple sea anemones waved their tentacles in the current and a sculpin scurried across the boat’s shadow. There was a whole world of activity going on below the surface, and we had front-row seats.

Our electric motor allowed us to approach wildlife in a quiet, unobtrusive manner that we call “stealth cruising.” The oystercatchers, for example, barely looked up as we passed by, continuing to poke at the rocks with their long orange-red bills. Frank noticed that these crow-sized black birds concentrated

in an area that he later revisited at low tide. Wearing wading boots and clutching a bucket, he became something of an oystercatcher himself, harvesting his limit and bringing home dinner.

We continued exploring the shoreline of Cortes Island in a Takacat 8-foot inflatable catamaran. While it offered more space and stability, again we sat close to the water, allowing us to observe otters frolicking almost at eye level. Several seals surfaced next to the boat, peering at us with enormous liquid eyes that I had never noticed when viewing them from higher up on larger vessels.

At one point near Twin Islands, Frank and I saw three unmistakable black dorsal fins slice through the water. We had encountered orcas in Desolation Sound on several occasions, and it is typically a highly desirable, thrilling experience. Yet watching the fins rise to a height of about 6 feet, followed by a spyhop maneuver and giant splash, I felt an unexpected emotion: fear. Orcas look much larger from water level, especially when viewed from a tiny, slow vessel. I couldn’t help but think of recent stories of killer whale attacks along the Iberian Peninsula—bizarre tales of Revenge of the Cetaceans featuring deliberately destroyed rudders and sinking boats. Weirdly, the lyrics of a Jimmy Buffet song popped into my head: “Can’t you feel ‘em closing in, honey? Can’t you feel ‘em schooling around? You got fins to the left, fins to the right…” That tune is about human predators, I reassured myself, eyeing the orcas nervously.

“Let’s head back to Cortes Bay,” I suggested to Frank. We took an inflatable two-person kayak to our next destination, Hague Lake, launching from the Kw’as Regional Park Trailhead. Bald eagles soared overhead as we paddled toward an island in the lake, surrounded by groves of cedar, spruce, and alder. A pair of great blue herons drifted over us squawking, looking like pterodactyls in a primeval setting, while mergansers kept pace on both sides of our boat. We became completely immersed in the wild on our return trip, when I accidentally tipped the kayak as we approached the shore. An ear infection had affected my balance, and the awkward climb out of my seat sent us both plunging into the warm, reedy water. As I lay floating, covered in various plants like a swamp creature, the deployment device activated in my life jacket, forming a thick collar around my shoulders and adding to my embarrassment. “Well, at least it worked,” I pointed out.

Just then I heard the call of a varied thrush, my favorite bird, which seemed to be watching from the forested shoreline. It’s an ethereal series of long, flutelike notes and was a perfect reminder of why we came here. Although Frank and I did not cruise a long distance by boat on Cortes Island, we got closer to nature than we ever had in bigger boats.

Cortes Island is essentially a wild place. Wolves, bears, and cougars roam its forests, and one night Frank and I thought we heard the haunting yips of coyotes. For decades, promoters have praised this setting for being “untouched” and “unspoiled” (see, for example, Margaret Sharcott, “Tenting on

Quadra and Cortes Island,” The Daily Colonist, Sept. 2, 1973). Even so, humans have been part of the environment here for thousands of years. Desolation Sound is located in the traditional territories of the Tla’amin and Homalco people, and Squirrel Cove on the eastern side of the island continues to serve as the primary village site of the Klahoose First Nation. The waters around Desolation Sound inspired Indigenous artwork that has endured through the centuries. Observant boaters can encounter petroglyphs (images carved in stone) and pictographs (images painted on stone with natural pigments) on shorelines and cliff walls. These ancient artifacts tell the stories of the people and creatures who tapped into the powerful natural forces of this watery place hundreds of years ago. A small boat allows a close view of the images, which should be approached with respect and left undisturbed.

With the arrival of Europeans, Cortes Island continued to be shaped by human presence and activity. Its name came from a 1792 Spanish expedition which sought to honor Hernán Cortés, a conquistador who led the colonization of Mexico during the 16th century. Also in 1792, British naval explorer Captain George Vancouver named (some would say misnamed) Desolation Sound, further conferring European sensibilities on Northwest waters. Over the centuries, Cortes Island attracted whalers, commercial fishers, miners, loggers, and farmers who all relied on the sea for materials or transport.

By the 20th century, recreational boaters had arrived, lured by tales of sheltered coves and anchorages surrounded by rugged peaks, steep forested slopes, picturesque waterfalls, and easily reached freshwater lakes. As early as the 1920s, yachters sought “escape from the travails of industrial modernity,” explained one observer, spreading the word “that Desolation Sound was a paradise because of its ‘wild,’ uninhabited character” (Jonathan Clapperton, “Desolate Viewscapes,” Environment and History, 2012).

Yet Desolation Sound has never been without people, and as the 20th century progressed, the number of recreational vessels increased by thousands, prompting the creation in 1973 of the marine provincial park to protect the anchorages. One Cortes Island local viewed this trend with alarm, criticizing the “White Plague” of “high-powered speedboats that roar in and out of bays and waterways raising swells that nearly capsize smaller boats” (Maud Emery, “A Time to Dream,” The Daily Colonist, July 22, 1973). “Will the pendulum swing back, returning Cortes Island to its quiet peaceful days [of] rowboats and canoes, with time to think?” she asked. Fifty years have passed since she wrote those words, and the question remains.

In 2008, a park ranger noted an “explosion” of kayaks in Desolation Sound, prompting speculation that “they can explore places otherwise inaccessible to yachters” (Jonathan Clapperton, 2012).

Frank and I experienced the small-boat advantage on our trip to Desolation Sound last summer, and highly recommend this approach to others. Just remember to take it slow.

Lisa Mighetto is a historian and sailor residing in Seattle. She is grateful to the Cortes Island Museum & Archives for images and information.

The electric motor allowed us to get close enough to this oystercatcher to see its striking yellow eyes and orange-red bill.

By Tamara Miller

Wouldn’t it be great if anchorages were always as serene as they look in cruisers’ pictures? Alas, that’s not a reality all of the time. Anyone who’s cruised on a sailboat for an extended period will eventually find themselves anchored in high wind or even storm conditions. Wicked weather is part of the cruising life.

Some storms are predicted well in advance, allowing sailors to change their voyaging plans or to seek shelter in a wellprotected marina or anchorage. Other times, storms are a surprise. That’s exactly what happened to us on a trip to Liberty Bay, outside of Poulsbo, Washington.

We first got word that bad weather was coming from a sweet couple paddling by our Nauticat 39, Polaris. Then we heard the news again the next day and confirmed it with updated weather reports. It was mid-September, the sky was blue, and the temperature was nearing 70 degrees. But the forecast called for winds up to 35+ knots out of the south near us the next day, and up to 50 knots in other areas of the Salish Sea.

We prepared Polaris for the impending wind and hunkered down below to watch the storm roll in. Flags near homes onshore whipped in the wind and dark gusts streaked across the normally placid Liberty Bay, turning it into a steely gray chop. In the distance, we watched other boats in the anchorage ride the same waves that were jostling our boat. My husband and I took

turns going topside to check on the anchor chain and snubber, periodically adjusting it to prevent chafe. By bedtime, the wind had died off enough that Polaris was no longer spinning and surfing the waves, just rocking gently to lull me to sleep.

I’m happy to say that I have no drama to share from the event. No videos of boats dragging anchor or rocking and rolling. We rode out the storm just fine, and the experience made me think about what we did right and what we could do better in the future. Here’s what we did:

We made sure our equipment was up to the job. This step occurred long before we headed to Liberty Bay. Having the proper equipment to safely anchor in heavy wind and waves is of utmost importance. You need to have confidence in your ground tackle; the anchor, chain and/or rode, windlass, snubber, and deck cleats all need to be up to the task.

We use a 44-pound Lewmar Delta anchor on Polaris, which is considered to be oversized on Lewmar’s anchor size chart. We have 250 feet of 5/16-inch G4 chain and no nylon rode. We use a three-strand nylon line for our snubber and always use it after we drop the hook and are set. For the storm, we did make a few modifications from how we normally anchor.

We gave ourselves plenty of swing room. The biggest threat while anchoring in storm conditions is dragging. There are several ways to combat that, but the first is to take a look around

your boat. How close are you to other boats? How close are you to other obstacles like rocks, shallow water, land, and docks?

Thankfully, there weren’t very many boats in the anchorage during this storm. Still, because Liberty Bay is such a big anchorage and connects to a long waterway that winds around Bainbridge Island, it gets a lot of fetch in certain wind directions. The resulting waves can lead to a pretty uncomfortable night on the hook. We opted to move Polaris so that we were upwind of all the other boats, and behind a headland so we were better protected from wind and waves.

We put out more chain than usual. The general rule for most cruisers is to put out a length of chain at least three or four times the depth where you are anchoring. We usually put out enough chain for a 5:1 scope; the only time we put out less is on a completely windless day in a crowded anchorage, like Port Blakely in the height of summer.

For the storm, we used about a 7:1 scope. The depth at high tide where we were anchoring was about 25 feet, so we put out about 175 feet of chain. The reason? If the wind picked up, there would be more room to stretch when the boat was blown back. Of course, chain doesn’t stretch, which is why…

We put out more snubber line. Having a snubber as part of your ground tackle setup is a must, especially when the wind kicks up. It’s also important for your snubber to be long enough to be let out when needed. For the snubber on Polaris, we attach it to the anchor chain using a rolling clove hitch with two half hitches, and then let out enough chain that the snubber line will take the initial load when the boat is pushed backwards.

For the storm in Liberty Bay, we put out enough snubber line that the chain fell slack from the anchoring platform of the boat, and tied the boat end of the snubber to both the starboard and port bow cleats. We also backed down on the anchor at 2000 RPMs for several minutes to ensure the anchor was well set and that the snubber was taking the load, and that’s exactly what we saw.

Luckily, our snubber held up in the wind storm, but there are several weak points to any snubber. The biggest problem is chafe. All the pressure of the boat moving back and forth at anchor could chafe the snubber line to the point that it frays and even breaks. It’s prudent to consider adding a chafe sleeve or even a length of garden hose to protect the snubber in places where it is rubbing.

We’re happy with how we rode out this storm and know that there is a potential for nasty weather in the Pacific Northwest for almost 9 months of the year. Because we intend to cruise and anchor in the area for most of the year, we will definitely get the opportunity to test the strength of our anchoring system again. We've also learned to check the extended forecast before leaving the marina for a multi-day trip, and have made it a point to select anchorages that are oriented in such a way that we will be protected from the wind. A little extra planning goes a long way.

Tamara Miller and her husband, Charlie, live, work and cruise the Salish Sea on Polaris. Miller writes about her family’s experiences on and off the water at www.fouleduplife.com.

With the snubber set and secured to the bow cleats, Polaris is ready to weather the storm.

Because a strong southerly was predicted, the author and her husband moved Polaris to the southern end of Liberty Bay where there was less fetch.

A rolling clove hitch works well to attach a snubber to the chain.

by Michael Boyd

Our boating has been filled with memorable moments. There was that first, and thankfully only, moment I forgot to shorten the dinghy towline before setting the anchor—then spent the rest of the day disengaging the line from the prop.

There was the time the engine stopped in the Duwamish Waterway as we were leaving the marina, because I had forgotten to turn the fuel valve back on after changing the Racor filter. And the moment we entered a major rapids when it was still moving quickly, because I hadn’t correctly read the current table.

“It could happen to anyone,” I said to myself.

And of course, there were the multiple times we realized the waves in front of us were much bigger than they appeared from a distance.

These moments are remembered for the sheer terror they engendered at the time. But along with those times when

cruising was stressful or unenjoyable, there are many more instances of magical discovery and wonder that only a cruiser can encounter. And there’s no better place to experience these awe-inspiring moments than in the waters of the Pacific Northwest. Here are a few of my favorites.

Early in our boating career, long before we actually owned a boat, we went on our first sailboat charter. We were beginners. It was pretty daring, actually, flying to Desolation Sound in a charter float plane and trading places with the boat’s owner in Tenedos Bay to spend the next three weeks cruising the area and bringing the boat back to Seattle.

One night we were anchored all alone in tiny Isabel Bay when I got up in the dark for a trip to the head. As I pumped, I was totally mesmerized by the flow of bright, blue-green phosphorescent water. I woke Karen and we both pumped and watched until the holding tank would hold no more. It was, for us, a truly magical moment, something we had never seen before—and could only have seen from a boat. So this was what cruising was about. We were hooked.

Another time, we were visiting a fellow cruising boat after dark and had to row back to our boat. The dinghy’s wake was afire, and each dip of the oars produced a circle of light with a trail of dots as the water dripped off the oars when they were raised. Dipping our hands in the water created its own pool of green fire. Even though we were in Mystery Bay off Marrowstone Island, with plenty of light along the shore, we had never seen

phosphorescence so bright.

Through all the years, we have looked for the glowing water every time we go out. When we get up at night, we always check for any phosphorescence. Sometimes it is very faint and it takes a quick swirl with the boat hook to reveal it; other times it is so strong that natural movement in the water will trigger the glow. We have seen the water sparkle from the flashes of small fish and watched the glowing trail of a seal swimming below the boat. These are magical moments.

While the days of bays filled so thickly with salmon you could practically walk across their backs are long gone, there are still sea creatures that occasionally fill the waters of some of our bays—moon jellies. These small jellyfish, up to 6 inches in diameter and harmless to humans, are just one of the types that sometimes migrate to spawn in the bays we anchor in. We have seen them many times in locations up and down the coast. They seem to rise out of the deeper water as the sun sets—perhaps they don’t like the light—and fill the water column from the surface as far down as you can see.

While some may think it creepy to see so many jellyfish in one place, we find it amazing that these simple creatures with limited locomotion can come together in such large numbers, and that they come to the very places to which we also flock. The final bit of magic is they are so well behaved; by day, they largely vanish into the depths, and we have luckily never had one clog our raw water strainers.

The cruising grounds of the Pacific Northwest were largely formed by glaciers in the fairly recent geological past. They carved out great valleys that filled with water, leaving the inlets and passages through which we cruise today. We recognize them immediately—deep water, sometimes really deep, with steep sides. And like Puget Sound, mostly large, but not always. Occasionally they are narrow, with particularly steep sides and deep water, like slot canyons for boaters. These are very special. Every time we go to Princess Louisa Inlet, we are awed by the snow-covered mountains and numerous waterfalls on the way to Malibu Rapids. But once through, a different world opens up. The inlet narrows and the side slopes steepen, showing more rock; many cliffs plunge dramatically into the deep water. The wind dies, the water calms to almost glassy smoothness, and the slopes seem to block most of the sunlight.

At the inlet’s head a huge rock bowl emerges, with many waterfalls feeding massive Chatterbox Falls, which drop almost directly into the salt water of the inlet. This 5-mile cruise to the head of the inlet is truly magical, and as much as we like being at the head, we are always astounded by the journey of discovery in getting there. It is so unusual that we can see why Captain Vancouver thought it was a river valley and not a saltwater inlet.

While many think Princess Louisa Inlet is the best of the best, it does have company. Several times we have passed

through Nakwakto Rapids and headed up Belize Inlet to the small opening that marks the beginning of Alison Sound. The entrance is narrow, but after the first bend the passage widens and the walls grow higher and steeper. Small river valleys briefly interrupt the otherwise near vertical terrain. Native

art in red ochre from long ago still remains on the walls. The passage continues through more bends until it opens up to the head. The water is calm, the air is still, and the silence is broken only by the sounds of birds and the engine. It’s made even more magical by the fact that we are likely to be completely alone.

Farther north, on the B.C. central coast just north of Bella Bella, is Roscoe Inlet. Once past its narrow entrance, the inlet is wider than Princess Louisa but far longer; it winds 20 miles through mainland mountains before reaching the head. The cliffs aren’t as intimate, but the feeling of isolation is much greater. Roscoe Inlet, like Alison Sound, gets some of its magic from the feeling that you have stepped back in time to an earlier age of exploration.

Not all canyon passages are narrow inlets. Again, north of Bella Bella, the main route for commercial traffic passes through Graham Reach, Fraser Reach, and Grenville Channel. These are mostly straight, deep passages about 1 mile wide—plenty of room to get out of the way of the odd ferry or cruise ship. The surrounding mountains are steep but wooded to the waterline. The magic here is the waterfalls. Everywhere you look there is water falling, white streaks through a green world. I tried counting them once but quickly gave up. There are just too many.

We spend a great deal of time at anchor and are always on the lookout for an extra special place. When we first started cruising, any place we could set the anchor and swing without hitting something or someone was special. Over time we have come to discover that some places are more than that.

The head of Alison Sound opens into a large river delta. As you would expect, anchoring can be challenging since the water rapidly goes from too deep to too shallow. We like to anchor in 90 feet on a short scope here. But unlike the typical mainland inlets such as Toba Inlet or Knight Inlet, the normal upslope and downslope winds are completely killed by the winding sound, and the head is totally calm. A little fog in the morning adds to the magic of this place.

Unusually, Roscoe Inlet ends in a small cove under high mountains but has reasonable anchoring depths. The inevitable river delta comes into the inlet a short distance away, making for great bear viewing from the boat or dinghy exploring. As with Alison Sound, inlet winds are dampened and the head is totally calm. Morning fog is also common here, but the day we were there the rising sun quickly burned it off, exposing pristine mountain views for the return journey out the inlet. It was another enchanting night at anchor.

One anchorage a bit closer to home has been magical for us for a completely different reason. Wahkana Bay is in the northeast corner of Gilford Island in the Broughtons. A short, deep entrance channel leads into a small and almost round bay. On the chart it doesn’t look promising; its bottom is almost flat, somewhat rocky and 115 feet deep. And in one corner there is low land leading through the island’s interior to Viner Sound, surely resulting in breezy conditions.

We first came here out of desperation—it was getting late and we needed a place to stay. After several attempts, we finally got a reasonable set on the anchor and settled in. With the calm of sunset came the clicks and puffs; a pod of dolphins decided to spend the night in our bay. We listened to their breathing and their clicking all night long. When we finally came back many years later, a pod of harbor porpoises swam around our boat in the evening and again the next morning.

For us, Wahkana Bay is truly a magical place, not because of its beauty but because of the extraordinary experience we had there. I’m sure every cruiser has their own list of places or events that have touched their heartstrings in some way or another, providing their own magical moments.

Michael and Karen have been cruising the Salish Sea and beyond for more than 20 years. Read more at https://mvmischief.com.

by Ryan Samantha Carson

As the golden days of summer gradually yield to the cool embrace of autumn, the Pacific Northwest undergoes a transformation that is as subtle as it is profound. The air sharpens with a crispness that hints at the coming winter, daylight hours grow ever shorter, and many boaters begin the familiar ritual of preparing their vessels for winter storage, signaling the end of their cruising season.

But what if the end of summer didn’t have to mean the end of your time on the water? What if, instead of winterizing your boat and packing it in for the year, you chose to embrace the offseason and discover the unique magic of winter cruising?

For some, the idea of winter cruising might seem counterintuitive. After all, isn’t boating synonymous with warm weather, sunny skies, and bustling marinas and anchorages? While summer cruising certainly has its charms, the waters of the Salish Sea offer an equally, if not more, rewarding experience during the cooler months. In fact, offseason cruising might just be the best-kept secret of boating in this region. Whether you’re seeking solitude, an opportunity to hone your skills, or simply more time on the water, winter cruising in the Pacific Northwest has it all.

One of the most compelling reasons to consider offseason cruising is the unparalleled tranquility it offers. During the peak summer months, popular anchorages and marinas are often lively with activity, filled with fellow boaters eager to make the most of the short-lived warm weather. While there’s a certain camaraderie in sharing the water with others, it can sometimes detract from the peaceful, intimate experience that many mariners crave.

In contrast, winter cruising offers a rare opportunity to experience the Pacific Northwest’s most beloved spots in peaceful solitude. Once-crowded anchorages and bustling marinas transform into havens of tranquility, where you can truly connect with nature and appreciate the beauty of your surroundings without the distractions of summer crowds. Imagine dropping anchor in a picturesque cove and being the only boat in sight, or tying up in a serene marina with an empty guest dock. The stillness of a winter evening on the water, punctuated only by the distant call of a loon or the gentle rustling of wind through the trees, can be a profoundly satisfying experience.

As the seasons change, so too does the landscape. The area’s flora and fauna undergo a remarkable transformation as autumn transitions into winter, offering a new perspective on familiar destinations. Snow begins to blanket the mountains

and hills, creating a stunning contrast with the deep greens of the evergreen forests. Migratory wildlife descends upon the Salish Sea, adding a layer of wonder to the environment. The air becomes crisp and clear, and the angle of the sunlight shifts, casting a soft, golden hue over the landscape. This seasonal change brings a quietude to the region as the hustle and bustle of summer tourism fades away, leaving behind an authentic and captivating atmosphere.

With this shift in season also comes a change in weather, a factor that often deters boaters from venturing out in the colder months. One of the most common misconceptions about winter cruising, however, is the notion that it inevitably involves battling harsh storms and rough seas. While it’s true that the Pacific Northwest experiences larger storm systems and greater amounts of precipitation during the cooler months, winter cruising doesn’t necessarily mean enduring miserable conditions. In fact, with proper planning and a keen eye on the weather forecast, winter cruising can offer some of the most stable and predictable conditions of the year.

While summer weather in the Pacific Northwest is often marked by less predictable shifts in wind direction and strength, winter patterns tend to be more consistent. Wind directions stabilize, and the speed and trajectory of storm systems can be forecasted with greater accuracy. This predictability allows mariners to plan their voyages with confidence, knowing they can either avoid the worst of the weather or use it to their advantage. Either way, the key to successful winter cruising is flexibility. Sometimes, this might mean hunkering down in a sheltered anchorage for a day or two, waiting for a storm to pass. But the reward for your patience is the opportunity to experience the raw, untamed beauty of the Pacific Northwest in a way that few others do. And when the wind is in your favor,

there’s nothing quite like hoisting your sails and harnessing the power of a winter storm to propel you through the water.

On a similar note, cruising during the offseason also offers a unique opportunity to sharpen your skills as a mariner. The challenges presented by winter conditions require you to be more mindful and deliberate in your planning and execution, ultimately making you a better boater. Navigating in shorter daylight hours, working around storm systems, and preparing your vessel for colder temperatures all demand a higher level of skill and awareness. These conditions challenge you to think critically about your decisions, anticipate potential issues, and adapt to changing circumstances. Whether you’re perfecting your docking techniques in heavier winds, learning to handle your vessel in different sea states, or improving your ability to read and interpret weather forecasts, offseason cruising provides a valuable opportunity for growth.

This growth extends beyond technical skills, of course. Offseason cruising fosters a greater sense of self-reliance and resilience. With fewer resources and less immediate assistance available than during the summer, you’re pushed to rely more on your own abilities and problem-solving skills. This increased self-sufficiency builds confidence, both in yourself and in your vessel, preparing you for even greater adventures in the future.

In addition to fostering confidence in yourself and your crew, winter cruising also allows for deeper connections with the communities you visit. With fewer visitors around, you have the chance to engage more meaningfully with locals, learning about the history, culture, and traditions of the areas you explore. The slower pace of life during the winter months nurtures a greater sense of connection and hospitality, as locals are often more relaxed and eager to share their stories with those who venture off the beaten path.

Beyond these experiential rewards, winter cruising offers practical benefits as well, particularly when it comes to financial savings. During the peak summer months, marinas and coastal communities are in high demand, and prices reflect

this. Moorage fees, fuel prices, and even the costs of dining and entertainment can be significantly higher during the summer, making it an expensive time to be on the water. In contrast, the offseason offers a more budget-friendly alternative for

mariners looking to stretch their cruising dollars. Many marinas reduce their fees during the winter months, offering substantial savings on moorage. Fuel prices can also be lower as demand decreases with the drop in boat traffic. Additionally, coastal communities that rely heavily on summer tourism often offer discounts and promotions during the quieter months, making it more affordable to explore new destinations and support local businesses.

All in all, perhaps the most straightforward benefit of offseason cruising is simply the joy of spending more time on the water. For many mariners, the thought of packing it in for the winter can be disheartening. The long months of waiting for the return of spring can feel like an eternity when all you want is to be back on your boat, feeling the wind in your hair and the salt spray glistening on your face. By embracing offseason cruising, however, you can continue to experience the thrill of boating, the beauty of the Pacific Northwest, and the satisfaction of adventure all year long.