I don’t know of any world study about unbuilt works of architecture, or about “percentage” of unprofitable works and studies, mostly forgotten. Most probably there is none and we may eventually have to consider it as one of the conditions of the practice of architecture. The factt is that a great lot of projects rest with no sequence and lost.

We all know recognize there are often unexpected reasons that prevent or impose the change of decisions already taken. Competitions also, more and more numerous, oblige a proliferation of proposals from wich only one, at the best, will be built.

History tells, however, that many unbuilt projects became, instead, references and belong to the history of architecture, such as Boulée’s or John Soane’s.

By the twentieth century examples multiply: Loos’ project of the colums for the NY Herald Tribune competition, F.L. Wright ‘s tower for Broadacre City, the plans and projects by Speer for Berlin, to which must be added the also monumental stalinist projects, the utopist Archigram ones, the Third International monument byTatlin, or Le Corbusier’s work for the Society of Nations. Regarding this set only, there is a bit of everything, from charged and abandoned works to competition entries, even purely utopistic proposals.

Lately and largely due to the important role attributed to images, a new interest dedicated to these unbuilt works has been manifest in exhibitions as well as competitions dedicated to this specific subject.

That is not the kind of architecture we will approach here.

Actually, “who makes a project in these days never knows if it is in fact to be done. A great part of what we design, is not really done, (…) more than one half of what we project is not really built, because of this or that, or the new Mayor, or no funding… for many reasons” (2001, p.22).

However, many other times, what is not built is the result of an absence of planning of the multiple variables required for the effective achievement.

There are also infinite projects successively charged for the same places, in a procession of situations derived from pure real estate speculation, or demanded by the most elementary needs dictated by propagandistic political agendas, that makes think that “architecture doesn’t really matter” (Siza 2007, p.12).

A whole series of practices that have generalized at such a low cost that it became taken as a small investment considering its potental outcomes. These are practices that reveal the missing planning in program definitions, in low consideration of the multiple implications, as well as in scheduling, economic and social consequences of changing proposals.

These facts are the main sources of delays and costs that multiply in the uncontrolled sequence that prevent even the materialization of the proects.

Contradictory interests are, therefore, the causes of unfulfilled projects. Starting by the lack of planning, that reflects in practices lead by circumstancionalism instead of programming and prioriy valuing, until the subjection to political schedules or funding, all those issues to be considered.

Other times, the recquirements of the comission descharacterize the buildings and their memory. That happened, for instance, in the long process of the Amsterdam museum, or Matosinhos house of architecture. Also, the studies for a hotel facility inside Peniche Fortress that started in 2000 and came to an end in 2010 with Siza’s dismissal for his not agreeing with the program and exaggerated number of bedrooms imposed, (more than the doble of the initial demand), which he considered inadequate to the place. This same project was now, twenty years over, restarted with a completely different purpose and, of course, without his enrolment.

Situations came out as projects that «were already contracted and are now in stand by» . Sometimes, cases are consequence of erronean decisions, and there are many examples of them assigned to the crises of building since 2014. Álvaro Siza has no doubts that «exageration took place in Portugal, and in Spain, more!».

There are thousands of empty houses in our neighbour country, which is a problem well too visible from our side of the frontier, because «in Portugal too» , he diagnosed, «there was an exageration of the investment»

Some works seem to be on the good way to achievement, yet, unexpectedly, all changes. That happened with continuous turnabouts of the long story of Stedelijk Museum that evolved a series of three fully detailed construction projects.

Sometimes unbuilt projects progress in time and become works of expectation, to which we return, like promises unfulfilled, still unhabited. It is a reallity that demands understanding the means of production of our living space: political aspects, economical, social and cultural too, because it is where we can find the reasons that prevent much of these products to raise.

Of course, we will never know most of these projects, likewise we will never be able to know most of the unaccomplished ideas of many artists from the different artistic expressions.

Although the project allows us to have a quite precise and detailed idea, we shall never know its impact in the territory. Therefore, any unbuilt project stays inside the realm of intentions, somehow vague and imprecise, whose true dimension would only be acknowledged by building, futhermore, its inhabiting.

It’s always painful to watch the unbuilt, for the architect who’s earlier and significat works provided the knowledge achieved only through finished works. “When interruption occurs in the preliminary drawing it is easier than when you finish the construction project, ready to build and it doen’s happen. Heartbreak is not the right word. It has to do with persons, not with buildings. Annoyance and, eventually, irritation. Bad for us if we take it as disgust. All the works ready to building provoque a certain uncomfort when not accomplished, like the first project for Avenida da Ponte, or the first for fundação Cargaleiro in Lisbon, a house in Algés for a beautiful site that was ready to build” (Cruz, 2005, p.54).

In Siza’s carreer, all buildings characterize by an almost obsessive care for detailing, recognizable since his first houses in Matosinhos (1954-1957) or even more at the Casa de Chá in Leça (1958-1963). A full atention is given to the carefull and adjusted choice of materials, never avoiding an experimental effort, eventually to the limits of fragility.

The difference between built and unbuilt work in architecture is the distance between design and reality. About this, Siza clearly states the need of building as the awareness that «design is a means, what matters is the building, but this one demands the making of a project» (2001, p.20), and «the building makes us go farther».

He reminds us that «the project is not architecture, but it is needed to do architecture » . Something that is more and more complex, enrols more participants, some of them sort out of the architect’s “control“. Besides, «whatever instruments we use or will use, such as the rigorous drawing that is done today – systematically, should we say -in computers, with all the advanatges of acuracy and time ; we use hand drawing, sketch that is a very agile comunication instrument, for ourselves and for alternative ideas, both with the team and at the construction site. We use models, of volumes and interiores, of fragments of spaces developed at a convinient scale. Of all those working tools, none, nr all of them, replaces the experience of space. For instance, the visit of the building in process opens ways of ripening and perfectioning our project» (Cruz, 2005, p.151).

This reality is only truly complete with space appropriation according to Heigegger’s “the subject that dwells a house also builds it by inhabiting” (1951).

The filling of the gap between the architect’s thought, presented by his means of expression -the project- and the ultimate purpose of it – the building, raises the relevance of what was not actually built inside the creative process of the author.

We can find “un-built” matter in some works completed, when changes made on the ideas expressed were of such magnitude that the result has little to do with what was thought.

A separation of studies between built and unbuilt, under our previous observation, may also diminish the scope of the full comprehension. It is inevitable to talk about each one to understand the other because they both belong to the whole of the architect’s work and it’s complexitity, with it’s advances and returns. It is inside the continuity of all developed projects that we discover and understand the one and unique line of conduct, and not only through the built ones however only these may, in fact, been taken for architecture. Yet and even if our present writting is not dedicated to the conditions of project development, or evolution and changes through successive phases of conception, the project itself allows a closer approach to the poetic dimension of the architects work. Considered that architecture always deals with creation and qualification of a place, what is not built, by it’s not consequence or quality contribution, remains in a quite hard to analyse limbo, between what might be and another reality.

The consequence of this is, in Siza’s words, to have “a very rich portfolio of projects that were not built due to a most objective obstruction. Also, a profolio of projects that were not finished by the same reason” (1996). Unlike many other artistic demonstrations, the architect is no more than one of the agents of the long-term process of making architecture, and the possibility of project achievement does not depend on himself.

“There are many reasons behind the unachievement of any project. It’s a problem that repeats itself. Any architect has it. In my case tehre is a larger number of projects that suffers it. That may be explained in several ways, starting from funding reasons which are today more common, because most public projects are expected to receive contribution from the European Community, and it doen’t come.

Or, in case it comes, it is the govern that has no money to cover its percentage. That happens in all the fields and not only in architecture. There is money lost, because countries don’t have their dued counterpart.

Many times, there are also political reasons, when the majority changes. That happens a lot in local power. It is almost a rule of fact that covers all the parties. When majority changes, what was being done or in process by the previous party is automatically dismissed. Often you see there is not even a profit analysis for the city.” (Cruz, 2005, p.157).

This foreward of ours tries to establish some of the limits for what we understand as the unbuilt work. The following writing has a structure in four parts: The first deals with one of the most permanent features of Siza’s architecture: the architect as coordinator.

The second overviews relations between time and space, and the mode how history density is integrated in work. The third is mainly focused on the new complexities raised by the practice of architecture debate.

The text will close with an approach to the poetic dimension, always demanded by the work of art, and always presented by Alvaro Siza’s architecture.

“… For another seven years, like Jacob, the architect studied the finishings, to the north and the south, where it was difficult the delivery of what was done to what there was.

In such a way that what came out was a seaside plan, delivered and paied.

But all was useless. Eventually it was understood that the architect chose only where to step and not to go, afraid of dangers and sea rocks.

So, someone said: “anyone knows where to step, and the architect is supposed to step differently than everybody else. And so, they fired him.” (Siza, 1980)

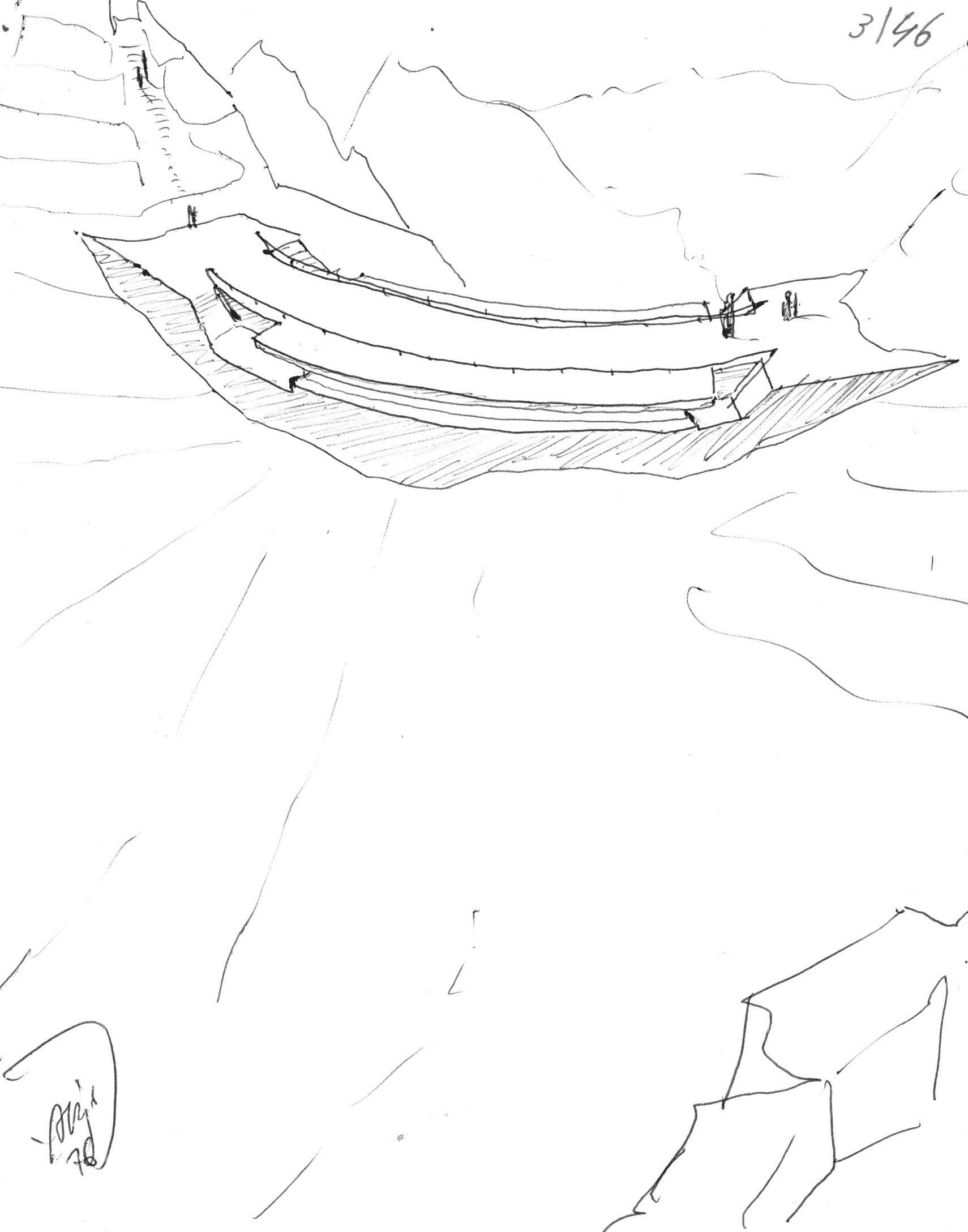

Although it was written later, this text approaches one of Siza’s works, after the construction of Casa de Chá and Piscina das Marés. In 1965 he was inveted to present the above study for the seaside road of Leça. That was a territory where, by then, nature and building were still in such an equilibrium that would soon dismantled by the real estate pressure, and “an allotment distorted the spirit of the place” (Siza, 2009a, p.25), by eroding all references as the reflex of an uniformity tendance.

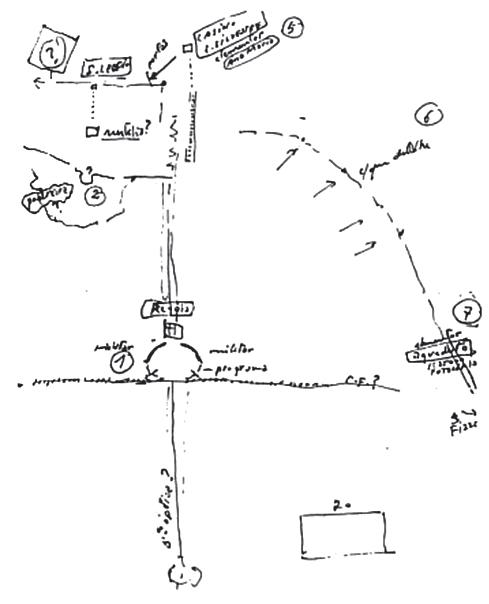

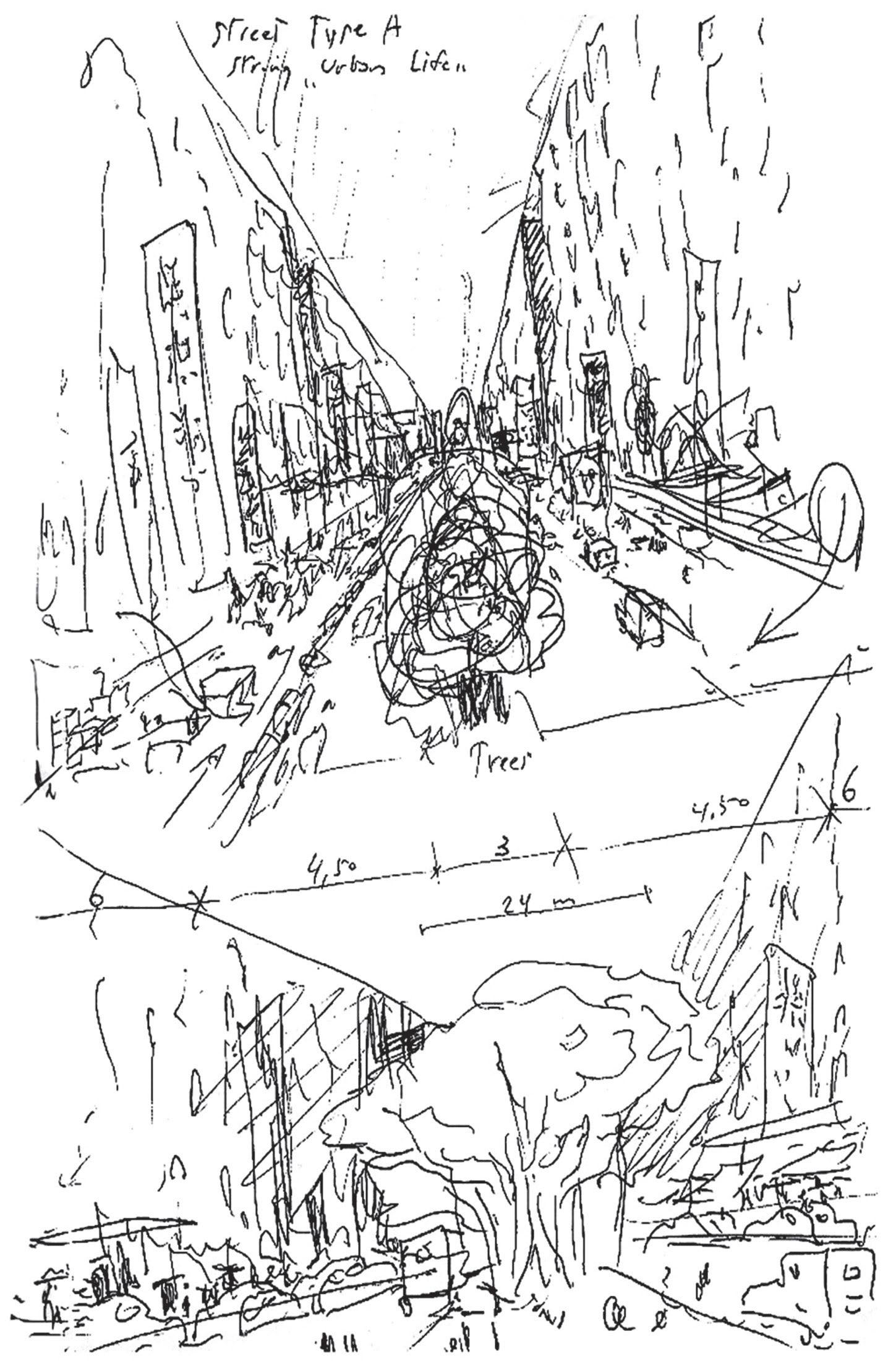

By the same time, he faced another challenge, a large and complex project: that was Avenida da Ponte (1968-1974), the connection between D. Luis I bridge and downtown of Porto. “The cursed avenue that, for one hundred years, searches how to honourly enter the city” (Siza, 2019,p.45). It is a project that happened when relashionships between planning and urban design started to atrack a growing attention.

What was in question, here, was not so much nature and building confrontation, instead, there were two distinct urban environments, where an enormous rock mass presented a dramatic condition. The project for the building had a glazed façade that covered the rock but allowed its envisioning. Just like Leça project, this one would never see its development, although a second one was made, thirty years later, of wich we’ll talk further. So, it remains.

Either cases show that territory is not and end by itself. It serves certain purposes, and the changes that occur are well revealing of the need for the particular role of the architect as a coordinator. He coordinates diferente realities, such as these, as well as other professions that intervene directly or undirectly in architecture, for a long-time process where different phases may be assumed by other specialists. Diverse surounding realities emerge too.

We are talking of a vision of entireness that Umberto Eco attributes to the architect by the same time, as “the only and last humanistic figure of contemporary society” (1968, p.389), since it is the architect’s role to organize all the remaining actors of the building process.

That role is finaly questioned by the “recently approved normative that leaves the architects in an unbearable situation.

According to the new law, the architect can only do buildings, so public space is out of our competence and in the hands of landscapers or other specialists. It is forgotten that the basis for architecture quality relies on the interdisciplary work and the sum of knowledges that is organized by architects whose work consists precisely in the specialists’ work”.

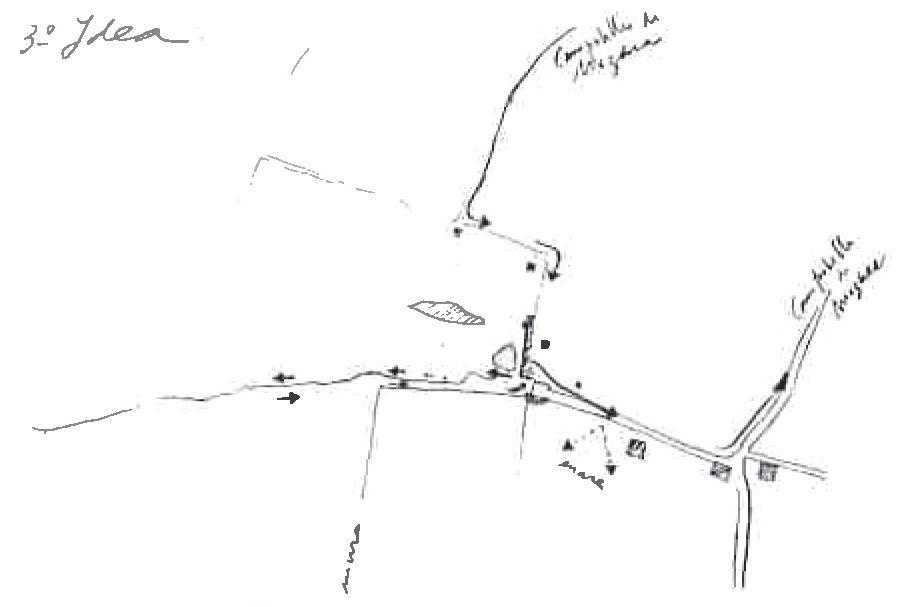

It was the awareness of the coordinator role, between very diverse realities, that conducted the above mentioned sudty for Leça seaside (1965-1974). Inside the urban conversion plan of Matosinhos, the search was of compatibility between the immense sea front, where nature kept its strength, with an urban fabric that still reflected the natural grouth of the city, but real estate advances could already be guessed as well as its fast effects and changes of pre-existant relations. The development was based on a road to serve the beaches mainly. However, it evolved into the leading north access to the city, with parking problems to be solved and, altogether, pipeline needs between the port and the oil refinery.

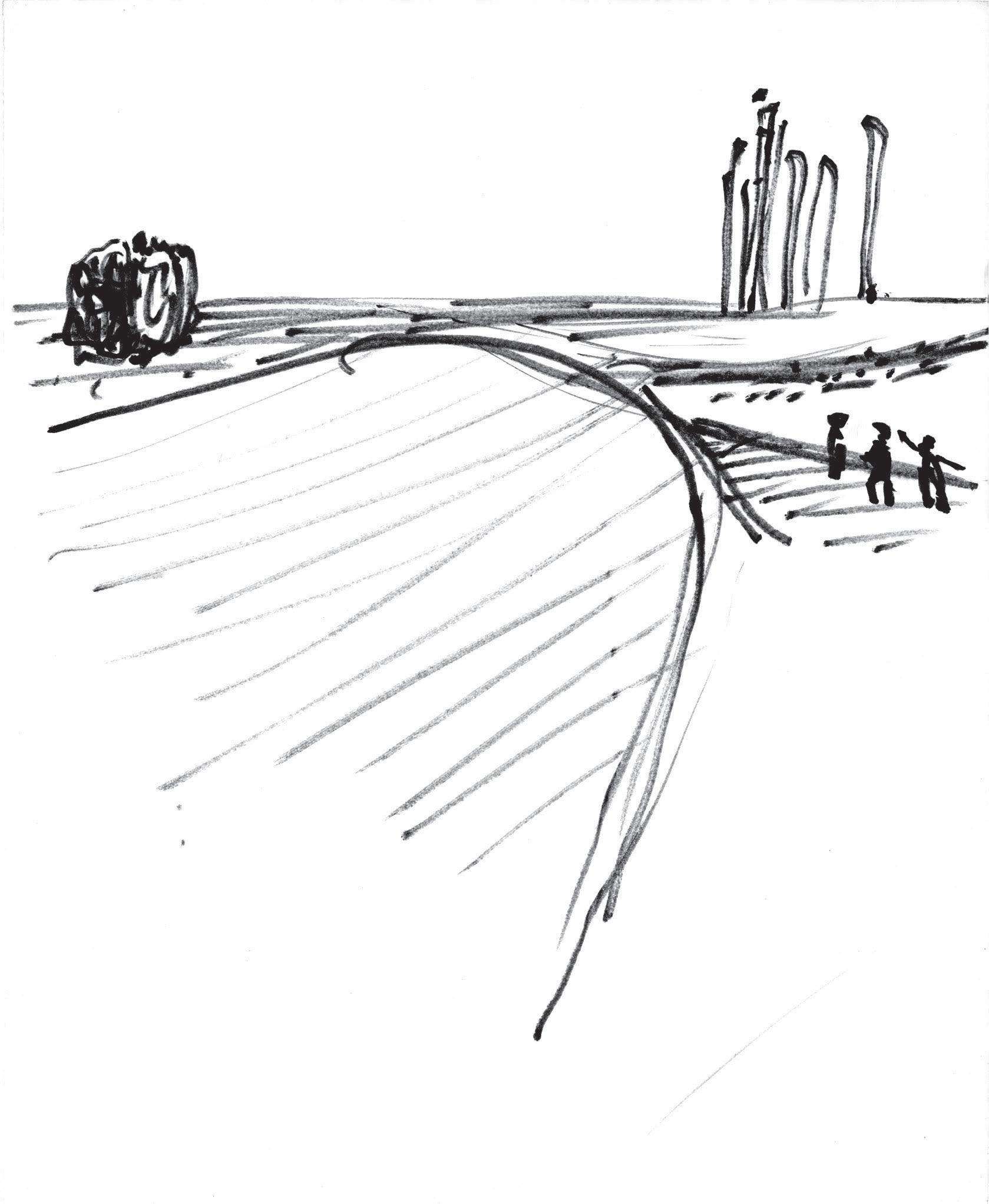

Siza’s main concern was the safeguard of nature and building connection on the frontier zone of almost 2 Km stretching out to Boa Nova. It was a plan where the monument to António Nobre monument had place, whose urbanistic design was never concluded, nor was landscape continuity preserved.

The issue, here, is a search for balance between the object and the city or the territory, only achieved through the domain of proportions as the alternate way to contemporary obsessions for the new images, the fears and monotony. Conscience is insured through the sense of unity and consistency of place manipulation, always employing unpredictable shapes for environment connections, according to a most humanist vision where nature and work are always seen as parts of the whole.

This approach will be underlined, years latter, by the committee for Wolf Prize in Arts, in 2001. Unanimously it referred to the outstanding critical answer of Siza for the continuous featuring either of landscape or urban fabric, starting from modest interventions whose architectonic power had cathalizing effects for their surroundings’ qualification.

In fact, those “first works germed an unrepressible and obstinate sensation of an architecture that has no end, that goes from object to space, therefore to relations between spaces, finally meets nature” (Siza, 2000, p.31).

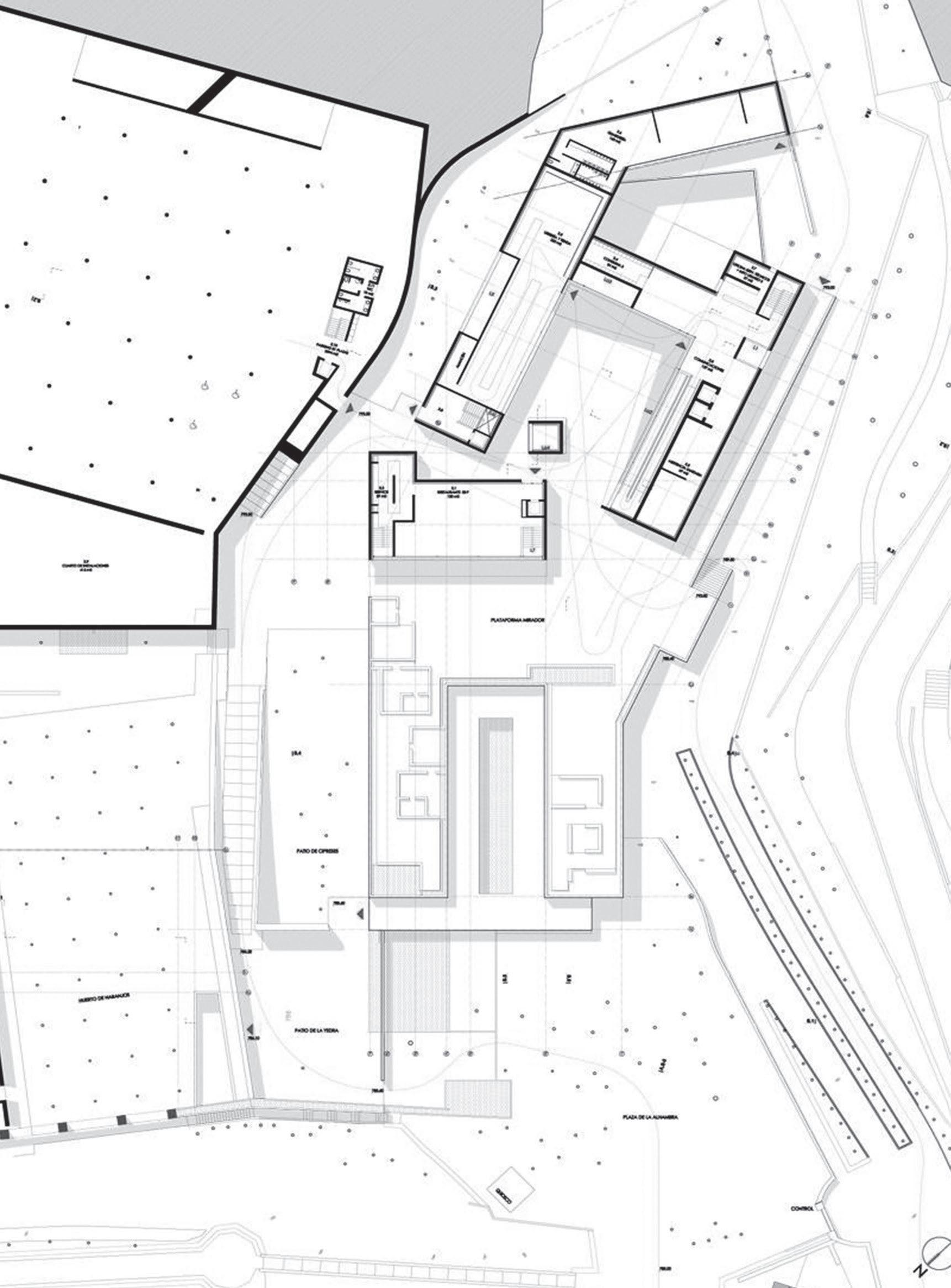

The same awareness is notorious is such diverse projects as the Cava de Cusa (1980), the urban park ok Salemi (1986), both in Scicily, or in the Granell museum of Santiago de Compostela (1994), all unbuilt. Also, in the ways how existent water lines organize and systematise the new Alhambra, Porta Nuova, the San Domingo gardens in Santiago de Compostela, as well as in the urban park of Lecce at the south of Italy.

References may be diverse : a tree ( in Santiago and FAUP); a water line (in Santiago and Alhambra); a rock (Lecce, but much earlier in Boa Nova); and so on.

The hotel presented in 1997 for Gata Cape in Almeria, Spain, by its insertion in the landscape, recalls the layout for another hotel designed thirty years back for Vale de Canas (1967-70) in Coimbra surroundings. Located on a site next to the salt pans, a natural Park and protected zone assigned for touristic use, the project integrated topography and respected the limits imposed by the Natural Resources Plan and a most strict legislation. Even so, under polemics raised by the extreme interpretation of legislation, the project was refused, stopped and abandoned into the burocratic inertia.

009

In all these projects, the confrontation between natural elements and built ones acquires an extraordinary dramatism that belongs to the concept, insuring continuity among several forms of expression and multiple scales mixing for a full environment organization that is not due to architecture only, but takes it as the leading factor.

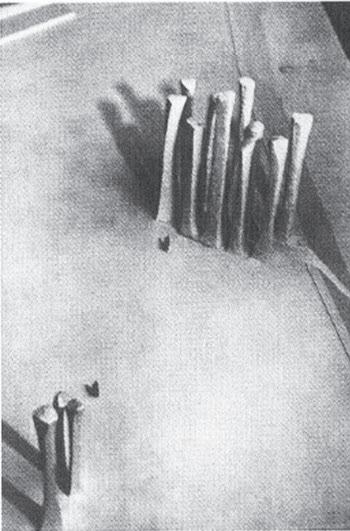

There is a physical continuity in Cusa, Sicily, that stretches into historical continuity. It deals with an ancient extraction stone zone, for ‘pre-fabricated’ pieces applied in the construction of Selinunte temples.

The land was used between the fourth century BC and the year 409 BC, then abandoned and so remaining till today, natural rocks mixing with capitels and pieces for future columns that remain differently finished.

As a most attractive tourist place, the project intended to qualify it, but was abruptively interrupted. “Cava de Cusa represent a condensation of transformation and continuity: the stones pieces are the parts of a building, that is a truth, however they are also the geography of that landscape” (Testa, p.136).

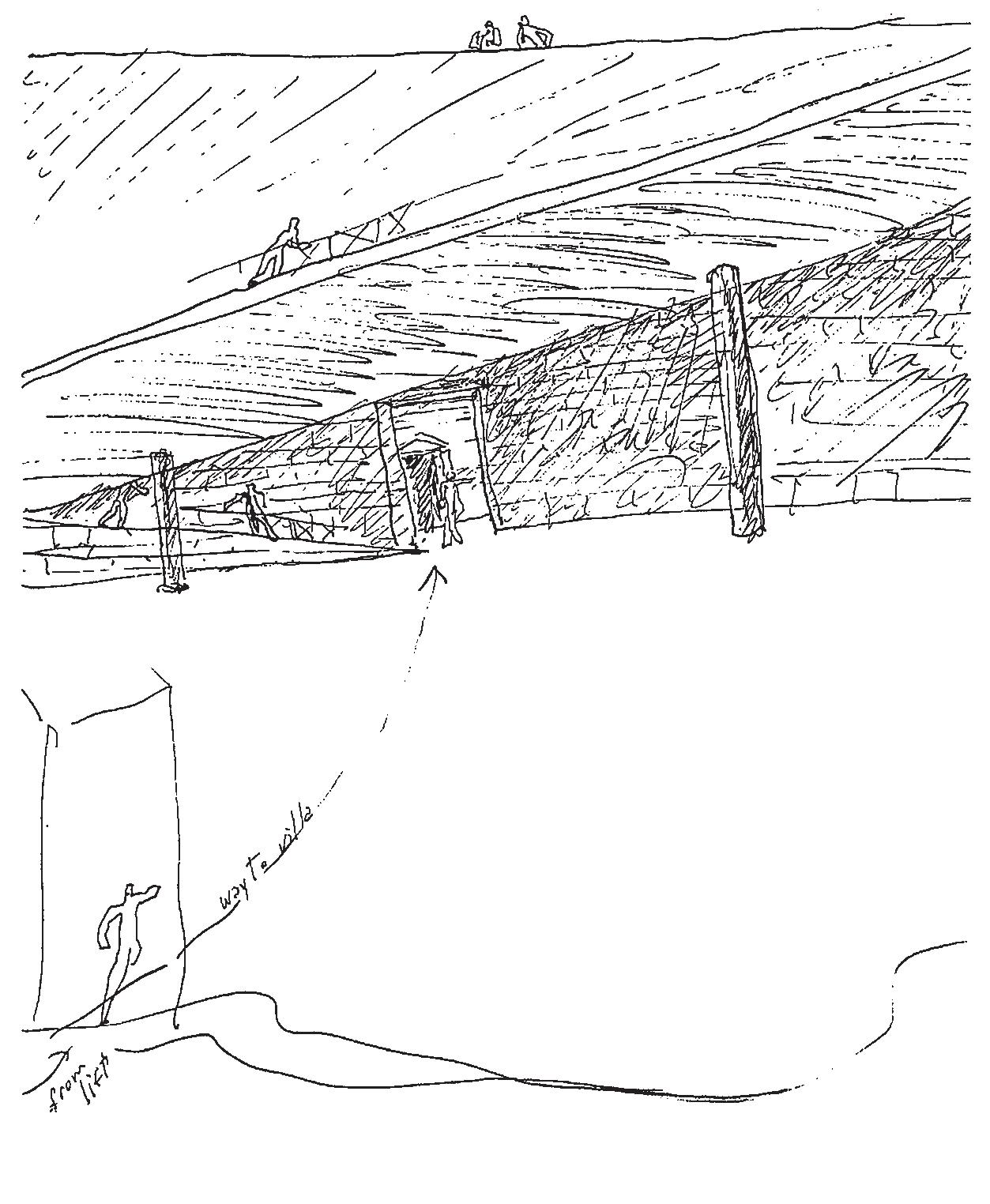

For the urban park of Lecce (2010 competition) project, the site was peripheric, close to the railroad station and apart from the built urban fabric, just like Leça. The challenge was to respect these references and establish a connection between the two plans. An almost vertical wall, several meters high, would emply the product of stone extraction that served the building of the city, therefore connecting and reconverting this part of it.

010

That was a proposal that joined natural spaces design and new pedestrian ways that were in construction. One of them was a bridge that would join together the accesses to a building whose construction has been successively postponed, for what was named “city of the art and music”

Once the Park refurbishing is almost complete, there is the house of music to be built, a six-storey building, three of them are above the pedestrian bridge level, the whole becoming an integrated public space for urban attraction and convertion of the full area.

Siza’s decision was always opposed to the frequent escape to understand marginal spaces.

He never pretended to unknow or ignore them, instead he chooses to confront and solve them. That became notorious in Caxinas (1970-1972), soon followed by Bouça (started in 1973) and S. Victor (1974).

These projects are underlyed by the kind of complexity, that James Gleik describes as the theory of caos. However, through the reflexes of the chosen technology we see that it relates mostly with the ideas for its response.

Furthermore, either we talk about small or large scale, not referring to the physical measure or scale but to the complexity evolved in each project, this option of his, becomes very clear in the numerous projects of Álvaro Siza dedicated to limit zones, frontier places or of transition between realities.

Many of these buildings give the limit-frontier concept the most determinant value for the solution presented.

That happened in the Salsburg Casino extension, in the project for La Defensa in Madrid and for Casa da Arquitectura in Matosinhos, all for terrains of strongly rugged topography, that shaped frontiers between distint urban structures.

017

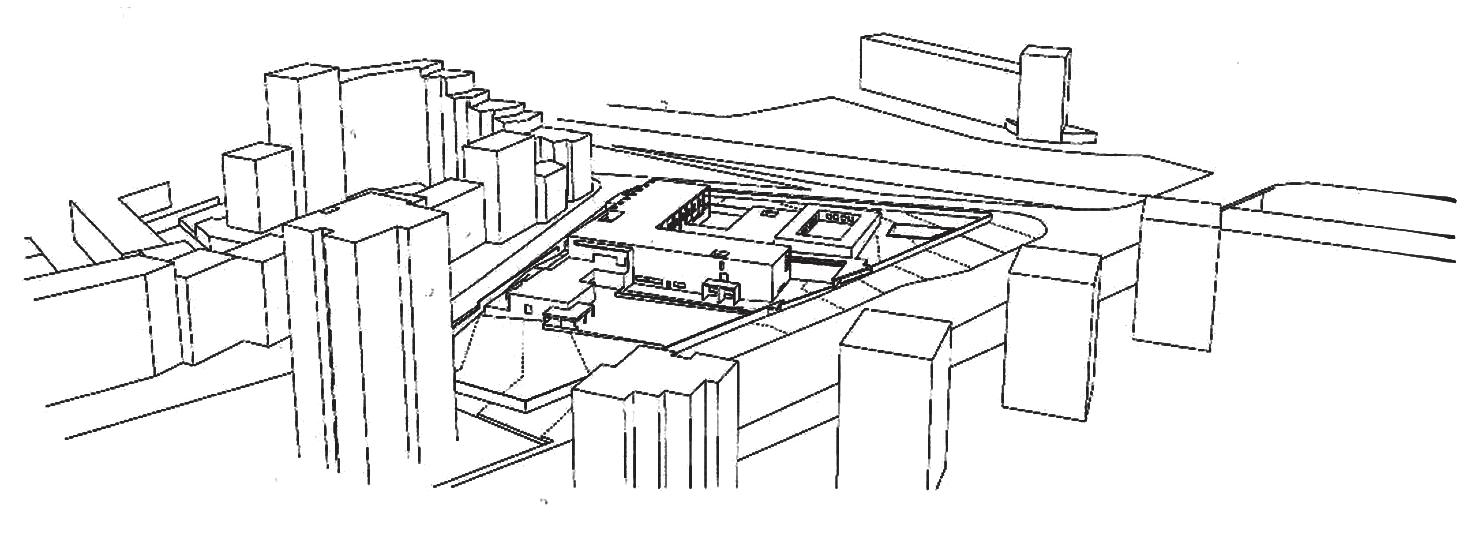

The competition project presented in 1995 for the ismaelita center in Lisbon, was also designed for a limit place, an uncomplete urban área, surounded by fast traffic roads.

The proposal turned its back to the roads and opened towards the inside, following a very simple and clear distribution scheme that established the connection to the city through a lower traffic street and a most urban layout.

018

Most similar is the solution for the assemblage of very constrasting buildings and volumes in the surroundings, that was faced in the competition for Helsinky museum in 1992. 3

Here, the main issue was the play of those disparate volumes together with respect for the old plan by Alvar Aalto for the area, which was, by its turn, a zone of hinge and border between urban fabric and a mostly natural environment. Aalto’s proposals in his plan have been more and more altered4 , but the great auditorium that was one of his last built works, still stood up.

021

The winning project for the Winkel Casino and Café (1986) was surprising by its urban setting.

022 | Winkel Casino extension, Salzburg, Austria, 1986

024 | Casa da arquitectura, Matosinhos, Portugal, 2007

023 | Winkel Casino extension, Salzburg, Austria, 1986

025 | Casa da arquitectura, Matosinhos, Portugal, 2007

022 | Winkel Casino extension, Salzburg, Austria, 1986

024 | Casa da arquitectura, Matosinhos, Portugal, 2007

023 | Winkel Casino extension, Salzburg, Austria, 1986

025 | Casa da arquitectura, Matosinhos, Portugal, 2007

Located in the upper part of Salsburg, besides the enlargement of the little café, the building was a cantilevered extension over the escarpment. The access system included a vertical connection which was an elevator detached from the escarpment5 that allowed the connection between the two city areas separated by a 45 metres difference in level.

022 | 023

The project for Casa da Arquitectura in Matosinhos (2007) presented a building located in a border area between the port and the city, to establish a built front next to the slope. Once again, it was an abandoned project, due to the ambitious program requested, whose cost made it impractible. Its solution would come latter through an old building refurbishing somewhere else in the city.

024 | 025

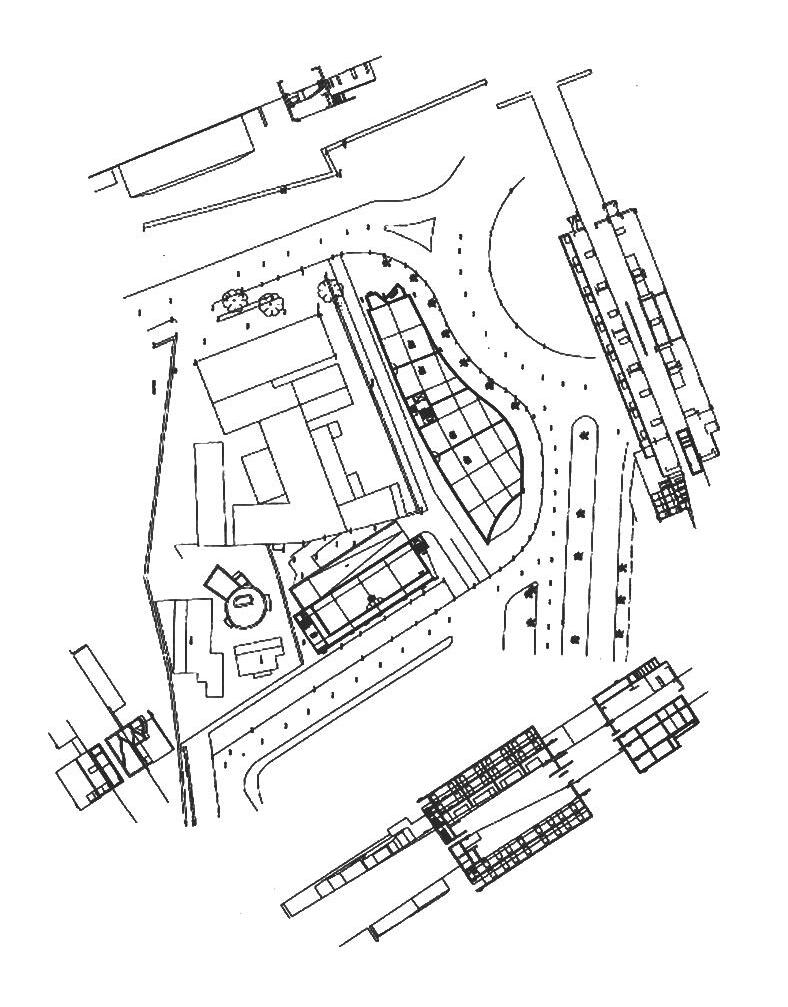

In 1989 Álvaro Siza was the winner of an important competion by invitation, for the Centro cultural de La Defensa in Madrid6. In this case, it was a building where there would be a cohabitation of a study center, a museum, a library and documentation center. Its big dimension and urban impact, more than 18 000 sqare meters, would make the transition between the urban fabric and the green áreas of the Parque Oeste of the city.

After a second phase selection whe he was the only foreigner remaining, and two years of deliberation by the town concelors, the project was cancelled again.

026 | 027 | 028

The same year, in a similar procedure as Madrid’s, occurred the competition proposal for the new Biblioteque de France. That was the library that François Mitterrand wanted “of a completely new type”, “and may have into account all the data of all disciplines knowledge and, above all, may communicate that wisdom to all those who search for it” 7

When “everything is taken for practical, ergonomic, hygienic, codified by Neufert, all bright, lined up – shelters like the wagons of an abandoned train, washable and comfortable”, the proposal structured around two yards, one open and the other closed, with a clear division in two areas of diferent functions, one confining the offices and the other the cultural space. Spaces had a most geometric structure because that is also the structure of the city.

029 | 030 | 031 | 032 | 033

What is common in these works is the border situation. So were the libraries for Salamanca and Valência that we shall see ahead. In times where the importance of the role of the architect as a coordinator is increasingly marked by beaureacratic work, and by increasing complexity or dimension of many projects, the time that mediates beginning and conclusion of the building is longer.

The project for the competition by invitation, for Caserta (1984)13 was sponsored by Fiat and Benetton, who were interested in reuse ideas for diverse industrial areas, that might go further than mere musealizing proposals. Another reality was faced here, shaped by a complex net of 18th century industrial structures. For such territory, “composed by traces and memories of its own history” (Gregotti, 1993, p.340), saturated by architecture, where the Palazzo Reale di Caserta stands, Siza’s project, as well as F. Venezia’s, present the most realistic solutions for the site complexity and the large number of abandoned buildings.

By applying the experiences and ideas developed for IBA, Siza’s proposal for the immense territory was a series of small and specific interventions, that we may consider as a modern functionality of a profoundly fractures territory.

046 | 047 | 048 | 049

Facing Macau, a city where Auge´s words “the eternal present where buildings can be replaced by others full of singularities to attract visitors from all the world” (2003, p.108), Siza authored one of the last great projects under Portuguese administration. The project, started in 1983, was a neighbourhood for NAPE14. It was a new landfills area, the kind of no place site, where space seems worthless, “the main concern (…) was to avoid that the new development might conflict eith the landscape or the city skyline”.

The project started by an analysis of the city growth, with successive landfills; the purpose was to preserve the coastal line through a canal that would keep a natural drainage taking adventadge of tidal movement. Meanwhile, a series of changes was produced in the project, a most regular feature of Macau’s dinamics, that completely and irreversibly modified the concept.

In the beginning, buildings would respond to the traditional proportion of the city’s public spaces; then, the number was increased as well as their relashion with the city, therefore what was built has little to do with what was thought. What we can find there now is but a grotesque caricature of the project, buildings raised to doble hight, and the whole relation to the environment changed.

050 | 051 | 052 | 053

Even if the place is taken as one of the permanent concerns of Álvaro Siza, if we want to understand what was not built, we must anlyse it in a different way.

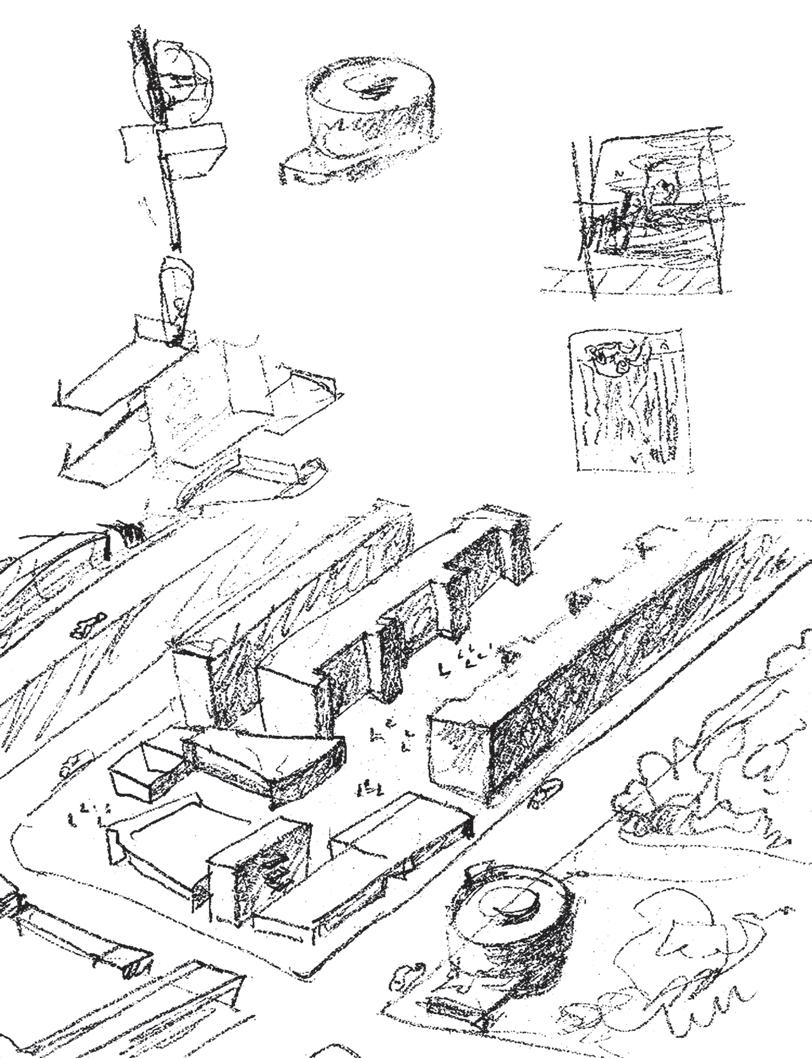

It is not a matter of acceptance that place became “a phantasmagonic thing” as Giddens calls it, but because there is a series of features that might have produced results out of those proposals. One particularly sharp situation for such no place projects, was Sevilla Expo (1986), where a proposal was made for a site without references or sequency, and a temporary program without a past or a future.

The project presented a grid with two squares, one of them around the Cartuxa convent that allowed its integration, and the other was more central to function as a reference and guiding space for all the Expo.

There is a great capability to work complex structures and domain of most different scales, sometimes unknown, searching for connections, always unstable, fragile and controversial. These are no place projects, but they never become projects of “non places”. Somehow similar, the buildings for the meteorologic station of Barcelona, or the Portuguese pavilion for Hannover fair, stand in places that differ from the ones intended.

We know that “constraints are an essential tool to make architecture” (Siza, 2007, p.12) or, as he also says, “are the number one tool of the architect” (Cruz, p. 53), and its exactly their articulation that challenges the expression of the architect.

The structure of the architect’s client endured a tremendous change in the last decades, now companies and the great financial groups becoming the leading producers of architecture. Changes came also, by large, from the ones at the political and economic structure, reflecting into a public client that always becomes an abstract entity15

When there are multiple intervining in a project, and they easily change (in rank or opinion), someone is required that endures the full process and keeps its consistency, that “specialist on not being a specialist”, which is the architect.

Since his first projects, Siza always paied a great attention to the social dimension of spaces, aware that to understand new realities it is necessary to insert the matter of space in the course of social actions and understand it in a dynamic mode. It is the passage of space as a natural fact towards space as a social process result (Wentz, 1991).

The social burden will reflect into what is going to be approached as participatory processes, that he faced I the SAAL case, when “the fight for housing, in Porto, Lisbon or Algarve, when chains were open, overpassed the limits of the house, the neighbourhood and the cooperative. It overtook the city.” (Siza, 2009a, p.28).

Participation in the process development is full of contradictions, as can be seen through facts such as the non acceptance of a ruin-wall in S. Victor (Porto) intended to safeguard privacy in the block, or the bad reception by the people in Cidade Velha of Cabo Verde of a vegetal roofing of the houses. Both proposals evolve testimonies and memories that relate to a past of poverty and isolation that people wanted to forget, when the projects came to offer that opportunity.

It is also an approach to artisanal work, a connection to the system of production, a close contact with craftsmen. When, about architecture, he says “I believe my work is based on continuity…” (1985, p.10) he is also assuming it as an artisanal work, likeTessenow did. (Grassi, 1979, p154).

Where the analysis of design pieces may help us understand his architecture best is on their expression of functionality, and the absolute need of observation as a priority of the architect. The more we observe, the clearer will show the essence of the object, and this will consolidate as a vague and instinctive khowledge. Cares with functionality may be framed by Adolf Loos’ thoughts about design, “important and current, that underline how necessity and, furthermore, art, is the primary foundation to achieve the perfect object” (2000, p.135).

Functionality is also a subject of study and thorow experimentation to find “the expression of a kind of singularity which, not betraying essence, may free design from too obvious reason” . From this search, derives na enourmous contention and a kind of banality which Siza connects to the quality of many outstanding furniture items from the past. Banality, here, has not to do with any lack of interest or quality, “but in the sense of avalilability in continuity” (2009a, p.239). That is the kind of quality that always stands in his works of architecture.

As for banality, in design and architecture too, it is the consequency of evolution of a project addressed “to a reduction to the essential and a gradual approach to substance” in a sense that for Castoriadis is the concept of insignificancy.

He also says that “you can’t do well a social neighbourhood or a museum before having a house done. Architecture is just one. The hands that draw and the hands that build, whatever they do, are always the same” (2012a, p.115).

That does not prevent him to admit the need for tests and experience (like in automobiles). “This is what must happen in the project, because only so, it is possible to catch up such a perfection in production that it reaches poetry” (Siza, 2009a, p.241).

The complexity of relations that occurs between the physical and temporal dimensions of architecture is, in its symbolic dimension, represented by the projects for monuments. These are, as symbolic objects, in a way comparable to religious buildings24, excellent examples of that same diversity and availability for primary functions and secondary ones.

For le Goff “a monument is, first of all, a drapery, a deceptive appearance, a montage. We need to start to disassemble and demolish this montage, disrupt this construction and analyse the conditions of the production conditions of the monument-document” (le Goff, p.472).

Presented by the power as a form of document, monuments are always thoughts about memory and history, mainly because we may assume that “history is what transforms documents into monuments” (Foucault, p.7).

This view has much changed in the second post-war, when another relationship with memory started to be searched for, afar from the representative monumentality that had been imposed by previous states. Now, memory should be represented in a closer human dimention, through an open and critical action, yet preserving the right to forgetfulness.

058 | 059 | 060 | 061 | 062

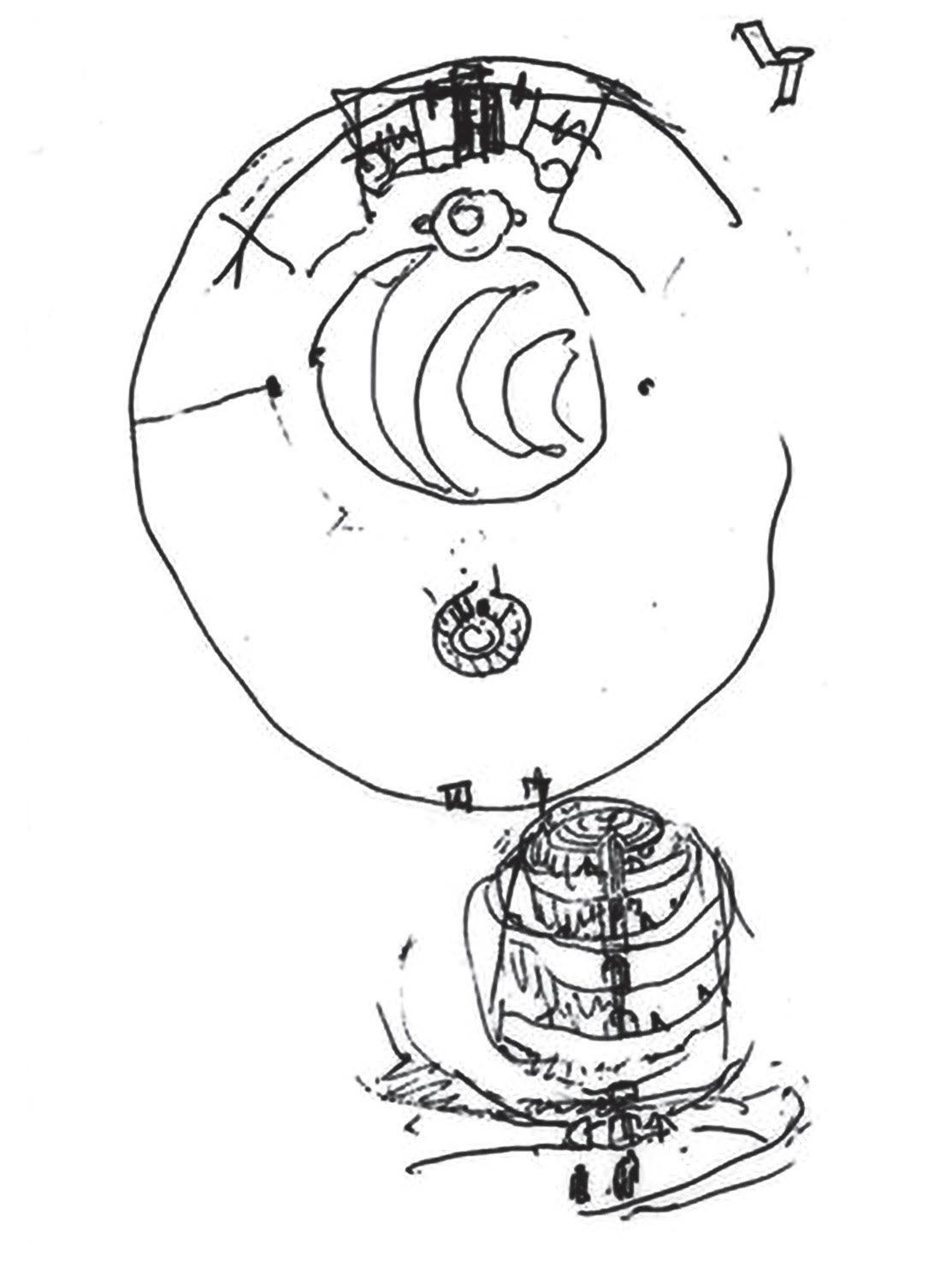

Among his many projects, Siza authored four projects of monuments, from which only one was built. Two of them are of a small dimension, namely the Calafates monument 25 presented for the river Douro mouth in 1959, and Antonio Nobre’s one in Boa Nova, Leça. By 2001, he worked on another, monument to “25 years of local power” , for Coimbra.

The fourth one, which is the closest in architecture physical size, was presented in the competition for a monument to the Gestapo victims, in Berlin (1983).

From these, both the António Nobre (started in 1967, followed to 1980 and was never entirelly built) and the Calafates one, are testimonies of the monument and monumentality debate of that time.

063 | 064

The great difference between all these monuments is that they were never treated as isolated elements, but as a part of a whole as space organizers. Either in the way how they relate and isert in the surroundings, or by profiting of their natural features, or even, the urban contexts where they inscribe themselves.

They always want to create places, by the relationship established with the sites, where they express estetic and symbolic concerns. In the Calafates place, there would be a play between several sculptural elements and the walk; in the António Nobre one, they would result from a clearing formed by two tree massifs never planted; in the victims of Gestapo monument, a kind of crater was proposed for the urban void that remains in the place where first standed the baroque palace of prince Albrecht in Berlin (Pessanha, 2003) and later hosted the nazi police headquarters.

065

Years later, Siza would be invited to make a monument to local power in Coimbra, that would stand near the Mondego river, next to the Portugal pavilion, that wouldn’t leave the paper. Such studies went on to 2005, and explore, again, the use of banal objects to build a monument, this time were several stone blocks with engravings of all the Portuguese municipalities’ names.

The highlight given to the coordinator role of the architect, in times of progressive specialization, stands up as a raising need of connections between very diverse knowledge areas, that go from humanities to the most technological sciences. The second post world war posed the debate of knowledge areas in the center of architect’s concerns, while facing the growing complexity and urgengy of responses.

Some tried to answer that knowledge diversity by a multiple parcelization of specialized ignorants (Santos, 1987, p.46), others searched, through the coordination of them, ways of keeping the necessary consistence of the discipline.

For Siza, the specifics of this activity involve such a large variety of areas that make it incompatible with a primary idea of specialization, as if it was admissible to think of “an architect competent for little houses, (…) for museums, or for sky-scrappers”.

In a way, the mode how knowledge has been excessively fragmented makes it incompatible with the need for successive analysis, because human mind does not work in a linear way, but in a syncretic one instead, in curves or zig-zags. Siza takes this nonlinearity of thinking and its openness to eventualities, as what allows the production of nonexistant information. They are memories, where times and dimensions of the present can be of variable duration, for ones or the others, and that means a greaty variety of interpretations. The will to search for difference in experimentation and learning, through the variety of works, leads him to accept small commissions, even when overloaded by large ones, because those are the ones that allow him tests that, in some way, are restricted at the others. He is quite clear by saying “I am against the idea of specializing. I like to diversify my work” (Siza, 2012a, p.117).

So, the references to Alvar Aalto, go futher beyond the non specialization, in the search of a global performance of the architect’s figure and its presence in the history and culture of each country.

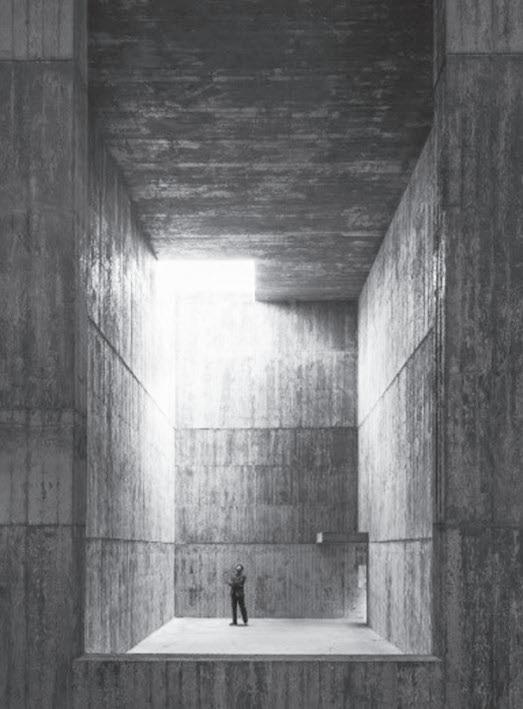

“To think of a space for the Rondanini Pietà is a small and passionate work. There was an international competition to create an environment for that wonderful sculpture of Michelangelo that has a most extraordinay story. Each of the invited architects studied the museum and the walks it offers.

(…)

The unfinished back of the Pietà is, however, an extraordinary document, related to its history. It is a marble bock offered to Michelangelo. He starts the sculpture, searching for something like the Vaticano Pietà, its most perfect polished marble, skin feeling. He died before finishing it, more than eighty years old. However, for unknown reason, the artist broke it, and started another sculpture, completely different.

The proposal was to subdivide the present room, organizing a square space plan to place only the Rondanini Pietà, not exactly on the center, but away from the walls of the room, to get around it. Besides, it was previewed to place the bonze mortuary mask of Micelangelo on the wall, as well as a head that appeared and is said to be of the first Christ. All is very touching, mainly because the Pietà was missing for a long time. I was chosen for the execution project and for the extension of another part of the museum, by the director of the Milan Museums. A stormy controversy, raised, then… Finito. But the experience of one full day alone with the Rondanini Pietà, that, is not gone.” (Siza, 2005)

(1999 – Competition study Pietà Room – Sforzesque Castle –Milan) The above description of the project for the pietà setting is a good example of how to work and make architecture with a minimum of elements. In this case, it is the structure of a walk by one or two pieces that must be in a pre-delimited space.

The only instruments for that work were the time to enter, to go through a space, to approach and for contemplation. That is often the essence in the museum function, as well as of our relashionship with time and space. Siza says that all has to do with the ’mode’ to expose, where “there must be possible to be aware of the position and the time that allowed “that” perspective, to understand the conditions and the net of relations between observer and observed. In the mode there is, for sure, the duration, the time. In the mode, the subject and and the object interact inside their ontological irrectibility.”

As Baumann would say, the more liquid the world becomes, the less space and time are the undetermined references of identity, where different times coexist. References to time and space lead us to the fields of history and geography, where architecture expresses the changes and conflicts that are social, politic and economical. She makes us understand the continuity of history times.

This understanding and consistency are also expressed when Siza explains what it means, for himself, “beginning” while thinking of work materialization 26

Such reasons may have led him to opt for construction courses in teaching, aware that there would be where to fing the connections between architecture, project and history. The same issues stand for Gregotti as the material of architecture. They reflect a comprehension of times and spaces, as well as relations in ‘density’ of a wider structure that translates temporal space, social and economic, therefore cultural and historic.

The kind of history whose study “has indirect routes to influence action” (Tafuri, 2011), taken as a product of experience and not as a memory warehouse, seen as a continuum between past, present and future, as van Eyck liked to say. For Siza “things flow. Even when a project may relate to some historical model, connection is never a direct one. There is a kind of metamorphosis” (2007).

When Siza began his work, in the 50’s, it was largely overpassed by the first generation of the modern architects, the need for a break with past and history. Such rupture with the past meant, “what all avanguard groups wanted to liquidate was not exactly the past but the passadism instead, the attitude that is based on a devaluation of the present in favour of a supposed immutability of the past” (Hatherly, 1979, p.61).

It was about ‘tempering’ the reading of the facts with the new features, taking them away from any paternalistic or moralistic thoughts. So, it is abandoned the idea of unterstanding them as a known and planed becoming, that released human beeings from de duties of choice and personal responsibility, once things would be made without us; ‘living up to’ was enough.

This situation was, by 1928, acknowledged by Fernando Pessoa as the “portuguese provincialism” , and Bauman calls it an “intellectual provincialism”, or folk-pop (Bauman, 2002). It was mainly a racional, cognitive and temporal decision. Social issues are understood as the results from a wide analysis of history, recovering the idea of historic continuity, not as the expression of conservatism but of rupture both in planning and project.

Much of the second post war debate locates in the epistemologic aspects and the continuity of time and history. That was the outcome of reality awareness before the need of answers for the massive destruction caused by the war. It was also the fruit from human sciences development, such as history, where antropology and sociology play an essential role for the attention payed to man, to his individuality and his social relationships.

After the first experiments on façade restoration in som e cities, it was quickly observed that “urbanity is much more than the form of the city, it is a way of life, a civic culture that may, eventually, develop in another setting and that, most likely, will only be achieved in another setting” (Innerarity, 2010, p.138).

The second post war relocated the concept of place in the center of atentions as well as in architecture, because, as an “activity of practices” she must “observe” and “overpass” the “functional data, the daily elements, the rooted habits and legitimate expectations, the learned shapes, the ones that may be trasformed and others that seem definitive, (…) all this is called the idea of architecture” (Grassi, 1979, p.191).

This was the cultural background of all artistic manifestations debate, all over the world. It was also where the problem of regionalism was placed, and ‘a necessary initiative’ was defended, materialized in Portugal, by the Inquérito à Arquitectura Popular27. This survey was a source of many misunderstandings: by the regime, it was taken for a way to commit architects with models from folklore to be extended to all artistic fields; by the architects it was “an effort to understand the relations between a way of life and architecture, not as source for proposals of spatial organization but in order to understand the concrete problems of society” (Siza in Testa, p.172).

The purpose was to show the great diversity in the multiple models of architecture, all born from their intimate relation with each site’s reality. It was an approach led by shared international concerns, addressed to the variety of housing forms, of the use of material and their relation to each territory. All these matters would latter consolidate in such studies as Norberg-Schulz’s and Edward T. Hall’ s, whose books circulated in ESBAP.

Along the 60’s, a series of initiatives took place, from the great media impact ‘architecture without architects’ display in MOMA, 1964-6528, to the studies from Amos Rapoport to Claude Lévi-Strauss. Analysis of built spaces focused on the importance of social and cultural features, where meaning and context were more relevant than content and objectivity.

This whole new setting of the world’s second post-war was already present inside the proposals of Team X that started to meet by 1954, preparing for the X and last CIAM congress, where it took place and was underlined the value of setting and the cultural understanding of architecture work.

The seething of these ideas, easily, arrives to the Portuguese architect’s knowledge through travelling and a few magazines. Of relevance were several writtings by Orlando Ribeiro, that influenced the (Popular Architecture) Survey. Contemporaries of the first works in Leça by Siza, were the portuguese survey and another, conducted by Lucio Costa, in Brasil.

The influence of the survey, whose works he followed attentively although without a direct participation, seems evident in some of those first works, even when he clarifies that “the vernacular was never the way” (Siza, 2000 p.90). The simultaneous enterprise of the survey and the beginning of Siza’s practice makes that some features of his works are, sometimes, mistaken as his approach to the context. For him, this approach is never an end by itself, it is, instead, the expression of other concerns.

Contextualization can be seen in his first works as well as in latter ones, that deliberately turn their back to the street, freeing from territory dependency, because “the site is never a fixed and closed thing”. The survey was the record and testimony of changes where the place is no longer the main scenery of life, and we assisted to community freedom from their traditional dependency of territory.

Siza acknowledges such influence, but he always demarcated by considering that a great importance attributed to the context serves for surpassing it. It is a process of observation and transposition, far from the immediate inspiration, it is a necessity that needs overpassing, because “physical context is very important, but it is not exclusive or prioritary”.

Attention payed to the places allows the conclusion that a building is always the transformation of what exists, a change of the site. Sometimes transformation is misunderstood as framing into regional or vernacular models, but it is a search for identifying, or for a concept that bases on the need to saveguard the long time of strategy, of waiting or destined to think and reflect.

The explanation for this is perhaps found in Pier Luigi Nicolin’s definition of context, understood as a demonstration of the need for synthetic work, the search for a setting in the surroundings, and “only” one more among the issues to be considered in the practice of architecture 29

Siza talks about a kind of time that allows finding a synthesis in “the relashionship between all the elements of construction in such a way that all the parts influence each other. That is syncretism and not formal assumptions” (Siza, 2009a, p.64).

Along that process we understand how things belong to reality: the functional data and daily life elements, the ingrained habits and legitimate hopes, of learned forms and the aspects induced by them, of the forms that may be transformed and those that seem definitive to us, etc.

In fact, the interpretation and debate of all these matters was, for a time, a most dear subject of almost all the post-war historiography, bet on understanding and framing the multiple references, often assotiating them to vernacular architecture, not forgetting to take into account thoughts on regionalism and its relations to internationalism and modernism. Even between the old nationalisms and the new regionalisms, because, as well as the notions of space and time, they were different ways of the need for ‘identification’(Herrle, 2008, p.291).

In the 80’s, the interpretation of all these experiences centers on the critical regionalism30, a term that Kenneth Frampton will latter disseminate and where he integrates Álvaro Siza’s work31

Siza refers to it as the “study od place’s conditions, a kind of realism, of pre-linguistic conditions” 32, and according to Montaner, is a quite confuse concept, because “it doesn’t offer any relevant clue about the position from where architecture is produced” and works as a form of “consolation for marginalized cultures and architectures” (2007, p.136).

The ”critical refionalism term, whose suspitious connotations (in fact historically circumstantial), must be taken as unsuficient or is ambiguous the adjective that comes with it, (…) evident influence translated into an internationalism of small and few tics” (Siza, 2009a, p.106).

066 | 067

It is Siza himself who refers to it when talking about the Tea House, where the natural context and its references to the “survey” are eventually, more present. Also, the Leça swimming pool, of the same time, has little to do with that, or even the swimming pool of Quinta da Conceição, almost of the same time, which has to do with both of them.

This is a fundamental theme to understand the path of Portuguese architecture from the late 60’s, with the survey publication, in 1961.In William Curtis opinion, Siza “was never a regionalist”.

It’s also “not worth trying to frame him into any historical or critical limitations” , or into those cathegories of the contemporary overmodern society and culture that globalizes and tries to uniform everything, and where the regional and the typical have their roles too.

Acctually, his creative process, that departs always from the observation and analysis of local pre-existances , is not directly deduced from them, but it is always done in the surch of poetics as a way to better understand and culturally interpret what they express.

For Alvaro Siza it was always clear the demarcation between context and what is the posterior creative activity that goes through a natural process of assimitation, interpretation and creation of all those references in order to and based on which, but not necessarily from them, work new propositions.

This attitude is quite well expressed in 1971, in the Alcino Cardoso project, which is an extension of a rural house, where the reviewing of the vernacular allows him to integrate a new language and volumetry inside a context that is saturared with traditional referencies.

We live today inside a context where communities have not desapeared, but liberated themselves from territory dependency, fact that, although not leading to the disappearance of places, has not freeded us completely from them also, what originates what might be called as “an individualized deal with the territory” (Innerarity, 2009, p.114).

For the city center of Montreuil, next to Paris 46, a project that was only partially built, the focuses were the olf farming walls from XVII and XVIII centuries, and the old urban structures that served to establish the references to that memenory of the city. Siza wrote in 1980 that “to build, it is not necessary to destroy. To transform, it is necessary and indispensable not to destroy the city” . The same idea is expressed in 2005, “It is necessary not to violate the walls well founded, or the soil that moulded them or that they molded – for an obsessive anxiety of a modernity that often, disintegrates construction and its setting, gardens and squeres, inner block gardens, terraces, slopes and outlines (…); mainly not to build more than the necessary.” (2009a, p.324).

Fusco says “architecture is not only the interpretation of space, it is charactering time in the space” (p.145) because the values of space are not enough without their immediate relation to the time ones.The recovery plan of Chiado shows this principle, where, keeping or improving the quality of urban tissue is much more that restore the looks or to search for new cenarios.

References are an important thing, but they can not be used in decontextualized sense or form. They make part of a whole, because meeting with the environment has to do with impression and emotions. As for the discontinuities of forms, they are inevitable, because they follow the analysis of the surrounding diversity that each project faces and constitutes its own reality. The way how old and new can be together in a unique work is present in many of Siza’s works, as is the arrangement of the church ruins and square of Salemi (1983-97). They are exercises of a continuous exploration on limit dilution, thoughts on discontinuities that we know for long,to be the ones of the city, where time and space dimensions, as a common good, are particularly inscribed, mainly in the public spaces. Urban projects, for their larger extent, are often confused with a number of timeless presents, but Siza always approached them as a construction that is consistently foreseen.

Submitted to countless interruptions between phases, it is necessary to keep a certain indeterminacy, because “the functioning of a complex system does not recquire the dissolution of its contradictions, it needs a continuous elaboration, for instance, under a form of transformation into other contradictions” (Willke 1993, p.99).

Complexity that has nothing to do with complication.

Siza says: “one of the things that impresses me a lot, in architecture and in the city of today, is the rush to finish everythink quickly. This tension for a definitive solution prevents complementary between the several scales, between the urban tissue and the monument, between open space and construction.” (2009a, p.227).

So, we risk to become submitted to what we may call the “tyranny of the little decisions”, that is, to go on summing up decisions that finally lead us to a situation that, initially, we didi not want…

About Bahia House (1983-1993)

“I presented the project for Bahia house in diferente places. There was always laughter.

Not for displeasure, I kink; the way how I presented it may have been interpreted as ironic, or demagogic.

But it was not so.

The project was defined after analysis of what, very directly, conditioned it.

Finished, I couldn’t imagine it differently; although I recognize that it might take a thousand shapes, less weird, eventually less controlled.

1.What makes it apparently capricious, scarcelly depends from the drawing moment or moods of the time; what makes it understandable has to do with centuries of elaboration, from which each of us knows – still – but a tiny part.

2. The unbridable search for originality impresses me; anxiety does’t bring but banality, a monotonous accumulate of «variations».

What amazes me is the frequent complex of «lack of imagination», or, the opposite to affirmation. As if imagination was something outside reason – overpassing it – something to introduce in the act of project as an autonomous process; or as if it might be one more instrument, to use in this or that moment, according to methods or intutions; or, as if it might be a rare aptitude.

What floats pre-consciently is not a disease or (something else). Frontier between conscient and unconscient depends on the ways of the reason, on its energy and requirement.

To live in liberty – to learn to live – goes through breaking that frontier line.

3. A brief explanation of the project:

a) A house was to be built on the right border of the river Douro, next to the city of Porto, between the marginal road and the water, in a narrow and large slope terrain controlled by supporting walls of loose stones: the terraces of wine cultivation that build the Douro landscape from east to west.

b) The road profile of the national road does’t allow parking outside the terrain and the Building Regulation for the place obliges a 15-metre clearance from the road. The terrain slope (from level 28,88 m to 9,20 m) makes impossible the hypothesys of an access ramp to the only terrace that has enough size for the deployment of the house (9,20).

The solution for the parking of a car is the construction of a garage at the road level, through a pontoon, if we want to

keep the landscape continuity not accepting an enormous landfill.

c) The acess to the house terrace may only offer the necessary comfort if it includes an elevator, to be complemented by ladder – a diagonal that allows continuity between the volumes of the house and the garage, together with structural an image consistency.

d) Ladder and elevator lead to an atrium and, from it, to the several previewed spaces, distributed around a yard. The whole floor is raised from the terrace level and stands on an existing wall and two pillar supports. You get, so, the convenient interiority when landscape is of an asphixiant beauty.

e) So, there is no caprice in the form that results from such pressing conditioning; and the comments I heard of «imagination at last» were not opportune.

e) What reason produces may become mostruous. Architecture - cosa mentale – survives through a control that overpasses subjectivism: through the codes that become universal, by agreement on the «good proportions» that have been tested through experience, where a me-who-design is not enough. A system of control, a safe code – universal – for space and form organization has been always the «responsible» purpose of architecture: « The Orders».

But how many achept, today, the Orders, even when they are desperately or happily unburied? Orders are the bridge between Man and Nature; they establish the necessary relationship. Through them Man places himself, not to become a body strange to the Nature where he emerges.

When a code goes into crisis, when only a few accept its references, or they are not enough anymore, it remains but to find the direct sources: landscape, cloud passing by, clearance, body, dance, immobility, stability. Particularities that make the Universe, things that turn around one man and of the gestures of men when they meet.

g) The design of this house stands naturally on what, of very old, lyes «sous la lumiere». Sudenly it got a neck and a head and wings; its paws descended to the last terrage and plunged.

A shiver must have gone through its riscs.” (Siza, 2005)

House Bahia is the explanation of haw a form, apparently complex an almos weird in design, can be a natural consequence of a simple solution.

This description of one the unbuilt works of Álvaro Siza reflects what his project process is, by finding amidst site contraditions and programa needs, the complex reasons for project development.

Bahia House

Complexity is here highlighted in the program of one family house and a small terrain. The kind of situation that may belong to what Bauman, referring to relations between complexity and liquid modernity, calls “contexts that depend on their initial conditions” (2007, p.65).

This is one of the paramounts, if not the greatest, transformation we assisted through the second half of the XX century, rapidly accelarating but more aware after the 70’s, that is globalization. Its origins have different and diverse causes, acting on a space that is strongly compressed and extraterritorial, where economic structures hold a determinant role, by altering ways of life, social structures, politique and cultural which, as Virilio says, does not deport people anymore but their spaces of subsistence and life.

Maybe, before, we thought that “more or less everything could be solved by the simple operation of externalizing the problem, by its transference to an out of sight “outscape”, to a far away place or another time, the ‘future’” (Inerarity, 2009, p.124), and, now, we became aware of a need to face our own time and space.

It was exactly to underline the role of architects and architecture, as reflexes of the richness and diversity of expression, as well as unifying of a common European culture, that the European Union instituted the Mies van der Rohe Prize for Architecture.

This prize assumption is that architecture is a slow process that adapts to social, political and economic changes. Among its goals is the promotion of understanding and meaning of the European culture quality, where the complexity of the meaning itself reflects together with its achievements in technological, constructive, social, economic, cultural and esthetic terms 53 Quality is referred to the universal values of current buildings, independent of their programs, highlighting the essential of things and not only their formal value.

In this social and economical framework, Álvaro Siza’s options about the need to understanding the architect as coordinator, and his enduring search for a unitity of time and space inside architecture, highlight his way of working.

Mainly after the late 80’s and great complexity programs, of diverse scale articulations, projects such as Haia (1983-88) or Giudecca in Veneza (1985), confirmed what was foreseen in Malagueira (started in 1977).

Complexity is not so much to do with formal experimentation, or (physical) scale of the buidings, but with program intricacy and environment connections. A full succession of experiencies had place, where the urban dimension of architecture acquired a raising presence and where, more and more “it is not the quality that we need, but a certain amount of that quality” (van Eyck, 1975, p.50).

Caxinas project results from a municipal program trying to control an existent core of clandestine constructions, but it would never be accomplished, remaining incomplete and, further, most altered.

The foreseen solution for this complex problem was a construction, formally very simple by using local technology and making use of all sorts of pre-existancies “a square that opens to the North, connecting the inside street to the sea, an another one that integrates an existing café” . From that set of small interventions, only both ends were built, mostly modified, partly due to a conflit with the contractor who wanted a denser solution.

Already in previous projects it is notorious the attention given to the complexity of spaces, as was the house Alcino Cardoso, or relations between inside and outside spaces, visible in several projects of the 70’s.

For an architect like Siza, always associated to the materialization of his works, and with the opportunity to build from the beginnings of his carrer, with rare quality, the unbuilt means an impossibility of allowing us to appreciate the essentially tectonic dimension of architecture.

Many of those works coincide with an increasing proliferation of charges, scattered around the world and demanding adaptation to this process. To start, there was the need to find coordination mechanisms that allowed the development of a multitude of projects and keep a most reduced team of colaborators. At a time when many offices grew and depersonalized, he could give response to the development of a growing number of works whose rithms, and regulations too, were different from each other.

Thinking about how to work in such disparate sites, he clears that “There are different contact processes. There is the understanding of a city atmosphere, specific problems, human aspects, personal contacts. I think that attention, perception and understanding capabilities are heightened because the stimulus is great. There is the natural curiosity of seeing a new environment, a kind of enchantment. All cituies are beautifull, even the ugly ones. All cities are my city.” (Siza, 2001b).

The solution that was found was to establish a collaborative relation with local colleagues 55 to develop the projects at each site, keeping what he always priviledged the most, that was team work in an office of restrict and controlled size. So he guaranteed attention to each of the projects, safeguarding his coordinator role, even when facing teams that grew, for programs and intervention scales each time more complex.

Dimension would be controlled through an isolation necessity that he describes as not “an escape from the meeting table, or from interdisciplinarity, or the phone, or the regulations files, catalogues of pre-fabricated or any simplifying tool, the computer or the residents assembly.

It is about conquering -that is the word -a baseis to work with all those things and for all of them. (how many café I went to; I change when I notice a special attention, mixing with tea and toasts)” (2009a, p.28).

Many of the proposals from the 80’s on, specially the Berlin projects, more tthan buildings are exercises of place creation. The kind of places that Heidegger says are not extisting before they are there, because they are what creates them 56 In his first works, around the 60’s, almost all Siza’s projects were small, and those that were not built are variations of the other ones. Exceptions were Leça marginal and Avenida da Ponte, analysed elsewhere.

For the most part they are in Matosinhos, small individual houses or not so innovative buildings, for little stimulus programs or highly conditioned. It will be in a second period, marked by the involvement in inumerous contests, eventually with no sequence, that we will find most significative works. Contests allowed dissemination of his works abroad, through countless magazines and books attracted by this different and clearly ‘marginal’ architecture, even when the world’s architect work became a process of growing legislative complexity, that reveals often, blocking of the most innovative solutions.

However expectant the proposals and unable to create places, as we saw, unbuilt projects become a kind of archives where to find references, ideas and memories that he will use as resources for future developments. It is because he believes, in line with many others, that the architect invents nothing, just copies what others have done. Siza copies himself sometimes, because “from my point of view, many of my works never got to be completely finished. The live with me, making a part of my continuous search” (2007).

We can find a good example from that epoch in some of the first studies for Bouça (dated 1973); they show great resemblances with the volumetries that would be presented for S.Victor (end of 1974); or in the façade of the rectorate library of Valencia University, that recalls the built solution of Boavista appartments, both in 1990. Again, in several sports facilities as Berlin swimming pool and the multipurpose pavilion of Vigo (1997) neither built but very similar to what would be done further in Gondomar (opened in 2007), or in Barcelona sports complex; oval spaces under unitarian domes, where the variety of programs fit, and the supporting areas organize peripherally. Other formally similar solutions, to overcome level diferences, can be found in Ribeira Barredo, house Bahia and Salsburg Casino, all using the vertical accesses as the main distributors and space structurers; regular structures are opposed to slopes irregularities and to the dominant horizontality of the constructions.

What makes it a particularly interesting solution, in the Salzburg casino enlargement, is the design of a horizontal platform that is slightly ramp, cantilevered over the passage leading to the vertical elevator box.

See, for instance, what happens with the ideas for the church in Rome, just “pointed” in the first phase of the project, how similar they are to the ones in Marco; we may guess that, in a next phase, surely they would derive into a dinstinct solution to be detailed and solved later; see also, the references we can find in the volumetries of both and the chapel for Gondomar (1973).

Besides the formal aspects, references have to do with the project methodology, as happened in Giudecca, where the intervention of several architects was previewed, and the same would be applied in the Chiado.

In such a creative work history, more than recalled solutions we find a natural tendency to propose others that, for other reasons, have not yet been tested, what makes them the kind of future archives. “Achives” wich are, naturally open to the other architects exercises of copy and reference, as an ordinary practice.

As already talked, along his carrer there were many references in the mechanisms that produce architecture and reflect on the size or complexity of the whole process and derive into unbuilding. Mostly there is the multiplicity of entities and contradictory interests, often are the changes of circumstances or programs, but in a specially way, there is the dependency of funding because it escapes from control. Clarity implied in paths and circulation of architecture is equaly invested into urban intervention. Here too, paths are always an essential element of the projects, such as the proposal for the reconvertion of Barredo in 1976 57. This proposal searched to improve the life conditions of the population through a series of collective equipments together with housing, based on the recover of ancient ways that connected the higher and lower parts of the city. Siza would do the same in Montreuil, in Malagueira (Évora) and in Chiado.

115 | 116

An identical option was followed for the swimming pool of Berlim, in a terrain of complex referencies where the architect intends to establish connection between all the surrounding elements: a church, the urban structure, the railway and, farther away, a canal, in such a way that the building would integrate into the whole setting.

Integration was, once again, produced by circulations, here solved through a ramp that links the church walk to the railway station, tearing the whole building and crossing underneath the pool itself.

Alvaro Siza highlights the need to acknowledge and imagine the walks and space sequencies to be capable of making decisions. “I only feel able to decide about details in the moment I can walk, mentally, inside the building”.

Only after imagining “the effect it would produce on the diverse characters, the fact of visiting those spaces, you are capable of making architecture.” (2010).

It may be a minimal intervention, and an entirely different context, as the arrangement of Getty Museum Villa58. A “typical american museum, because, in the end, is the reproduction of a roman house, under whose courtyard exists the car parking”.

The walks, again, are what structures “the way how to enter and how rooms are used, lightening and relation with external spaces; the café, the anphiteater and other equipments are located out of the house.” (Siza, 2005)

117

These projects are harder to read, because refrences are more tenuous, or even nonexistant, so you need to search them in aspects that are almost ‘marginal’ to the project, like archives and others.

The same is true about things corrected during construction, that can improve it. This is something that has become impossible by the architect, these days, but other intervining on the construction process have a significative capability to impose changes. However detailed and specified the project may be, something always recquires corrections and adapting to imponderable, but this option is always subject to economicista decisions that distort some of those aspects.

Given the complexity and costs envolved in great public projects, it is perfectly understandable the concernes of public powers to find costs and scheduling mecahnisms. What becomes less reasonable, however, is that control not having, as its ultimate purpose, the quality of the work, closing itself inside an almost autophagic logic whose goal is no longer the project, but the control itself.

Naturally, large projects are the most frustrating for being stopped, considering the larger investment of time and work, but they are also those where that happens.

The so-called Avenida da Ponte 59 is the place of one of Siza’s most stricking projects, initiated in 1968, immediately after studies by Robert Auzelle, who invited him. That project was remade, with another program, in the final ‘90s.

This second project “has nothing to do with that one from the sixties… The concept is completely different. Now it assumes one thing that, by that time, I don’t know if I did it only calculatively, to have it approved, because I was not at the point of seeing the balance between urban fabric and monument was essential in terms of city environment.” (…) “The gret controversy was moved when the wonderfull project of architect Fernando Távora for Casa dos 24 was built. But it is stuck (…) That is an evidently controversy project. For its quality, courage and vision. When I made Avenida da Ponte, Fernando Távora showed me his project. I found it brilliant.

“…The hardest thing in a project is to begin it. It is like catching the end of tissue mesh and start to undo it little by little. For me, one of the main ends is the function. To do it we need a fantastic functional program. The project development is its to break free from the respect for functions.

Breaking free in the sense of not respecting, is proposing something that may follow very diverse paths.” (Siza, 2008)

One of the first monographic studies of Siza’s work, published in 1986, with writtings from K. Frampton, B. Huet, O. Bohigas and V. Gregotti, has justly the title: “poetic profession”. It is a title that expresses also the understanding of poetics by Muntañola, that can and must be used as an instrument for the critical analysis of a work.

Long before, however, Heidegger stated that “all art is essentially poetry” , a thought that relates people’s experience and spaces “in harmony with the environment, the earth, the sky and the divine”

Gregotti, in 1972, called it “a kind of autonomous archaeology made from strata from previous trials and error corrections that in anyway introduce in the final proposal, which is built by accumulation and purification of successive discoveries that become the data of the posterior ones” , that is an “archaeological foundation, only known to himself”

Alves Costa calls it the task of architecture “to find out what exists already” (2015, p.121).

This kind of poetics exists in any scale works, since architectonic space must go farther the three physical dimensions, to include time and go beyond its boundaries. Poetic quality must be articulated with the immense technological availabilities and the growing complexity of cultural demands (Muntañola, 2000, p.23).

If focusing the architect’s performance and his production helps us restrain any thoughts about the theoretical limits and the disciplinary practice of architecture, the analysis of its complexity allows to establish an approach to his exercise, yet neither of these aspects or the whole make any sense without the poetical dimension. It is such that, by inerence to any artistic manifestation, tends in architectural specificity and its functionalism, to be often forgotten.

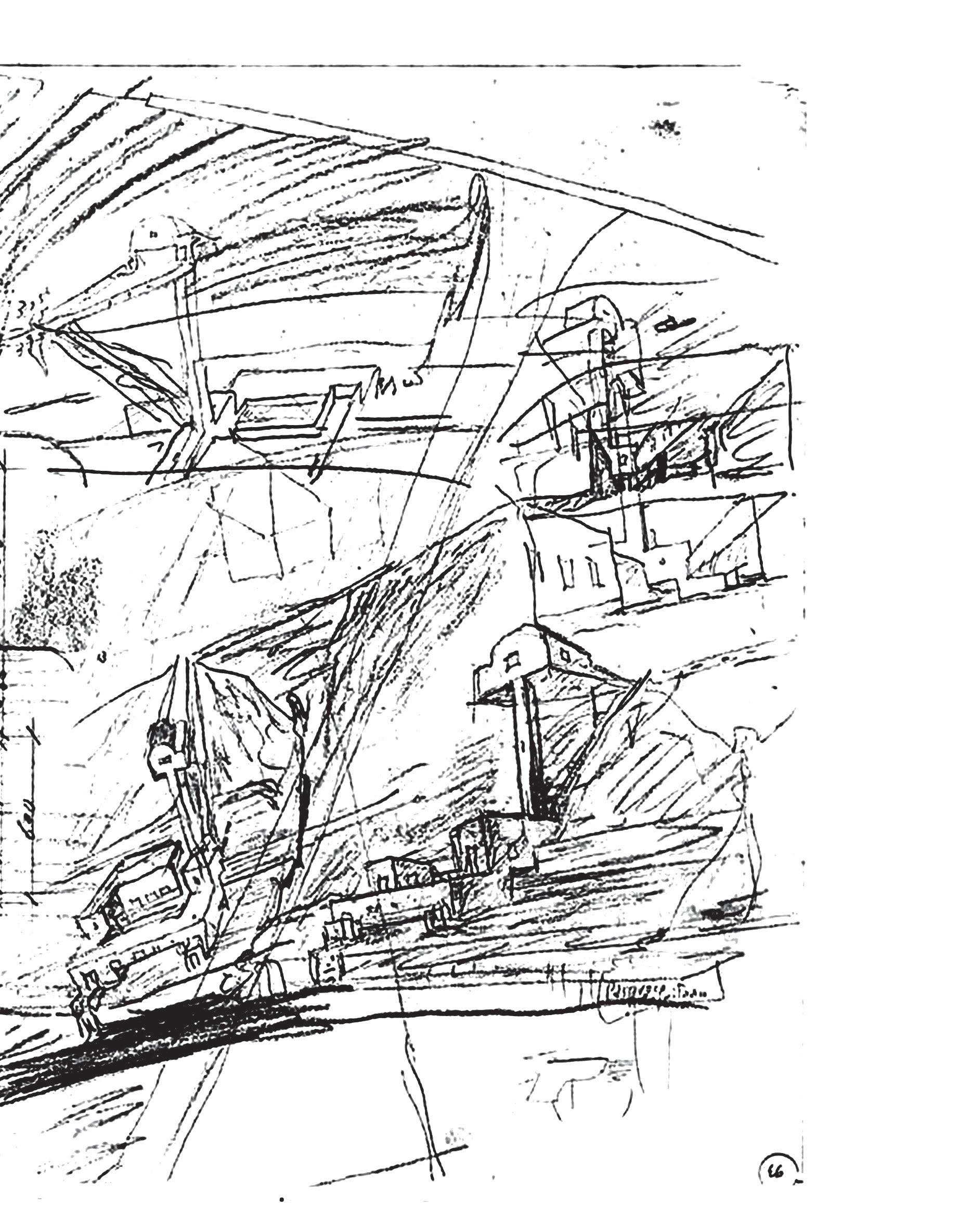

To search for the poetic expression presupposes understang the way how projects are approached and developed, according to Siza “architectonic creation is born from an emotion provocqued by a moment and a place” (2009a, p.79).

Differently from Távora, his master, who made thoughts over the blank page, as the place and material of all creation anguish, Siza sees uncertainties always related to a building approach that starts at the need to anlyse the place and make a drawing before beginning to calculate the square meters of the construction (Costa, 1990, p.13).

So, they are placed in the multiplicity of paths open by the permanent demand, without certainties, expressed by his words, “I don’t dare put my hands on the helm, watching only the polar star. And I don’t point a clear path. Paths are not clear”. (Siza1983, 2009a, p.28-29)

Clarification is found in Tafuri when referring to the “fundamental difference between beginning and origine? And why a beginning? Wouln’t it be more productive to multiply beginnings, where everything comes together so that I may recognize the transparency of an unitarian cicle that grows from interwined phenomena that want to be recognized as such?” (1980, p.6)

In such beginnings may be found “the expression of any singularity that, not betraing the essence, may free design from too obvious reasons. It achieves, so, a touch of authenticity that attracts in a not aggressive way, but, at the same time and partly, emerges as banal. To start with an originality obsession is an uneducated and primary process.” (Siza, 2009a, p.241).

Actually, “to the moment before we start (…) we have the world to our disposition – what, for each of us, constitutes the world, a um of informations, experiences, values” (Calvino, 1990, p.149).

It is after this multiplicity of beginnings that work develops because “when I am called to project a building for a that place I don’t know, or have a vague idea, sometimes the first drawings help to desnchain a series of thoughts that materialize later” (Siza, 2009a,p. 47).

The same difficulty places itself to decide the moment when a work must be finished, even because, for Siza, a job never ends. It doen’s matter him, so, the imposition of perfection or style before the construction of a support for urban life and its changes.

Just like Borges who said “we publish not to spend life correcting drafts” , so he feels the need to get free from projects, even when refers to ‘end’ as “an imprecise word, a kind of translation error, to replace by the word start” (Siza, 2009a, p.366).