Designs for a Cooler Planet is an annual festival that showcases research-based bold, experimental and creative concepts to improve our lives in the future.

Welcome to visit us at the Otaniemi campus from 6 September to 6 October 2023. The festival is part of Helsinki Design Week and the European Comission’s New European Bauhaus initiative.

12

24

The invisible roles of power

Documentary dives into sources of creativity

36 The hidden secrets of Finnish clay

5 Openings Riikka Mäkikoskela is working at the edge of the invisible.

6 Now _ Bits of news, big issues.

10 Column Matti Kuittinen and unwanted construction.

OUR THEME Invisible

12 Theme Einat Amir, Astrid Huopalainen and Matti Nelimarkka speak about the invisible wield of power.

18 Who Alma Muukka-Marjovuo makes basic art education visible.

22 On science _ Tiny sensors open-up huge prospects.

24 On the go Defining radical creativity with a documentary film.

32 Dialogue Maria Joutsenvirta and Jani Romanoff recognise resilience.

35 Wow! Jesse Jalonen’s camera sees invisible people.

36 On science Finnish clay can solve the crucial problems of concrete.

40 On science _ Making the genome visible with information design.

42 On science News in brief.

44 In-house Lovegear is the new bright spot on the campus.

46 On science What do you really know about 3D printing?

48 Wow! Algae gobble up carbon dioxide in a reactor built by students.

50 Doctoral theses _ Jenna Multia and atomic layer deposition; Laura Rosenberg and the changing meaning of ownership; Anahita Farsaei and electricity markets.

52 Everyday choices Ken Dooley, what makes a building smart?

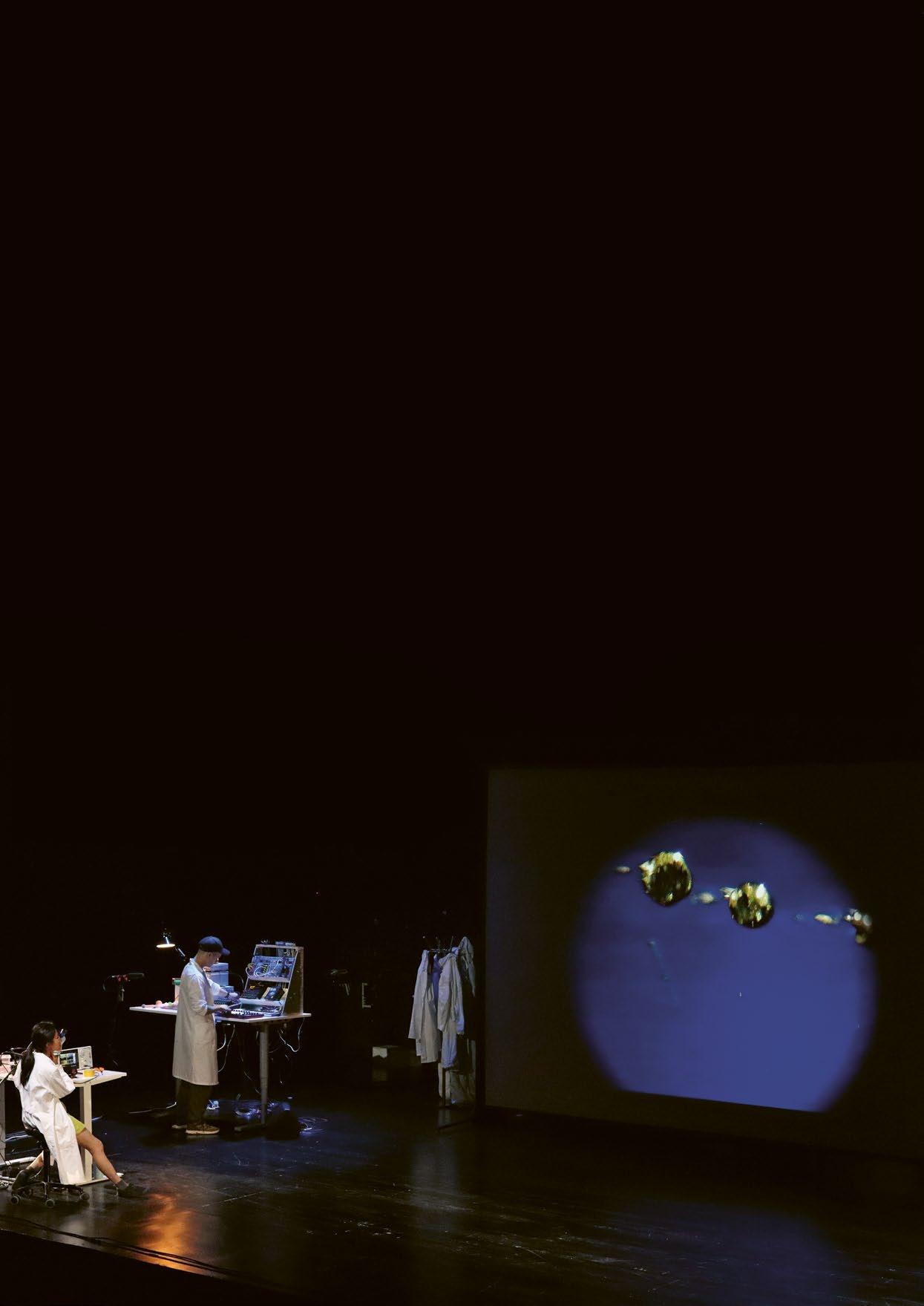

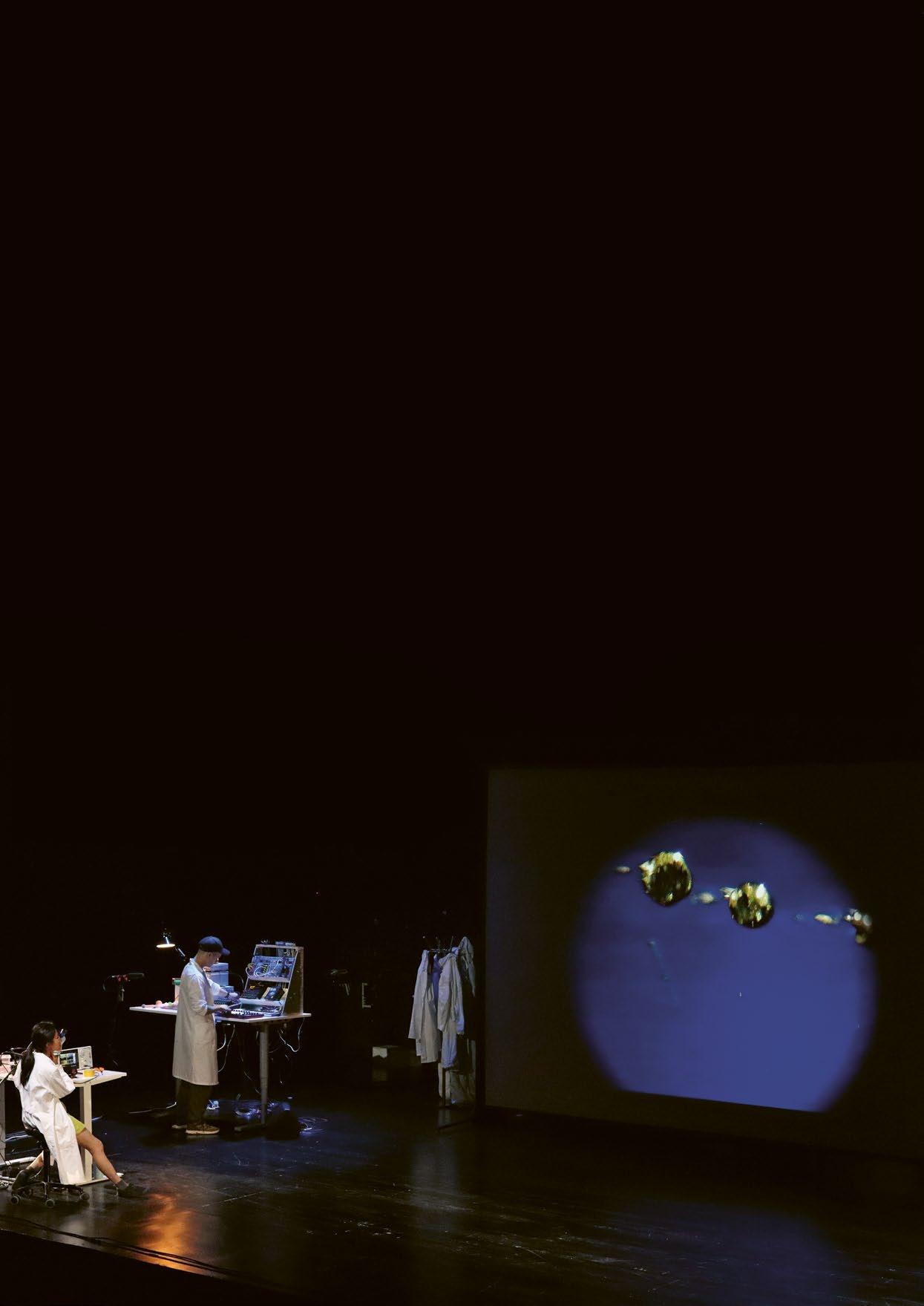

54 Collaboration Nano Steps is a micro puppet show.

33

Read more about the festival in the insert or online.

ON THE JOB

IIKKAMATTI HAURU, ILLUSTRATOR

The word ‘superpower’ usually means some unique ability to influence the world. Perhaps ‘invisible superpowers’ are more passive and quiet. Their influence is real but subtle. Such abilities include sensitivity, openness and the ability to listen. These powers enrich my life greatly, even if I might not benefit from them in a material and concrete way.

HAYLEY LÊ, PHOTOGRAPHER

There are many things I consider superpowers in everyday life. One is the ability to hyper-fixate on my hobbies and subject of interests, so deep in the flow state that I forget the world around me. It might feel silly, but that’s what I consider an invisible superpower.

PUBLISHER Aalto University, Communications

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Head of Content and Media Katrina Jurva

MANAGING EDITOR Paula Haikarainen

LAYOUT/PHOTO EDITOR Dog Design

COVER Hayley Lê

CONTRIBUTORS IN THIS ISSUE Amanda Alvarez, Richard Fisher, Tiina Forsberg, Iikkamatti Hauru, Minna Hölttä, Johannes Kaarakainen, Jaakko Kahilaniemi, Kalle Kataila, Veera Kemppainen, Anne Kinnunen, Krista Kinnunen, Milla Kokko, Hayley Lê, Annika Linna, Maarit Mäkelä, Niina Norjamäki, Samuli Ojala, Tiiu Pohjolainen, Aleksi Poutanen, Marjukka Puolakka, Jukka Pylväs, Mikko Raskinen, Zoë Robertson, Amanda Ruggeri, Meeri Saltevo, Sedeer el-Showk, Joanna Sinclair, Noora Stapleton, Tiina Toivola, Jenni Tuominen, Outi Turpeinen, Annamari Typpö, Maria Uusitalo, Helena Vannas, Nita Vera, Vertti Virasjoki, Sheung Yiu, Hanna-Mari Ylinen, Enni Äijälä

TRANSLATION Tiina Forsberg, Sedeer el-Showk, Tomi Snellman, Annamari Typpö

ADDRESS PO Box 18 000, FI-00076 Aalto TELEPHONE +358 9 470 01

ONLINE aalto.fi/magazine EMAIL magazine@aalto.fi CHANGE OF ADDRESS crm-support@aalto.fi

PRINTING PunaMusta, 2023 PAPER Maxi Offset 190 g/m2 (covers), Berga Classic Preprint 90 g/m2 (pages)

PRINT RUN 5,000 (English edition), 31,000 (Finnish edition)

SOURCE OF ADDRESSES Aalto University CRM Partnership and alumni data management

PRIVACY NOTICES aalto.fi/services/privacy-notices

ISSN 21799-9324 print ISSN 2323-4571 online

Hayley Lê Printed matter 4041-0619 NORDICSWAN ECOLABEL Printed matter 1234 5678 PEFC/02-31-151 PEFC Certified This product is from sustainably managed forests and controlled sources www.pefc.org The carbon emission of this printed matter is evaluated according to ClimateCalc. www.climatecalc.eu Cert. no. CC-000084/FI 4 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33

Creativity helps us navigate the invisible

As a teacher and researcher in the visual arts, I find the invisible difficult, even frightening. Sensing for me is strongly tied to what I see, though there are many things we as humans cannot or do not want to see. Society and the global conversation function through words, and as a university we are tied to the spoken and written word. Visuality is a different way to observe the world, and my work is to ensure that what is visual and seen is translated into words.

What we see can be vague and subject to interpretation. Even words are not always exact. As a university our job is to observe and interpret different perspectives. Researchers bring to light things we don’t see in everyday life, transforming findings from the microscope into words. From words we must advance to interacting with publics, making visible, conversational and understandable that which we create, innovate and give back to society.

That is one purpose of the radical creativity documentary (read more starting on p. 24). It’s a new communications medium and a way to appeal emotionally and visually, not just through words. Researchers have traditionally aimed for objective knowledge, but in a changing world we see that researchers are humans, too, with personalities and histories, in a place and time. There’s more there than just rational reasoning – could we make use of that in research? Emotional intelligence is an invisible resource that could be employed in teaching and research. In the arts, we use emotions and meanings as tools. Aalto University was founded to combine technology, business, science and art. I believe we can reach something new, creative and radical by bringing emotions into the mix.

In a turbulent and chaotic world, it’s hard to imagine new futures or realities. But there’s lots of potential in the invisible, and as we make choices, a direction and result emerges, becomes visible. This applies to making art and to the research process.

Doing or making with a low bar and at a fast pace is central to the idea of radical creativity. Iterative experimenting can dispel the invisible: when we enter the mode of active doing, it fosters hope. Experimentation inevitably leads to disappointments, which must be accepted and learned from, even amidst uncertainty.

At the university, we are constantly at the edge of the invisible. New knowledge is created by probing, interrogating, investigating this invisibility. Relating to the invisible and the unknown in new ways requires courage – and even silly or dumb ideas –and a beginner’s approach. Creativity requires letting go in order to birth something new.

Riikka Mäkikoskela

The author is Doctor of Arts and Head of Radical Creativity at Aalto University. Radical creativity is one of Aalto’s three cross-cutting theme areas.

Kalle Kataila

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33 \ 5 OPENINGS

Doing or making with a low bar and at a fast pace is central to the idea of radical creativity.

Would you like to update the knowledge and skills you need for your work, but you’re not ready to commit to long courses or degree-oriented education? No worries – the university also offers other types of options.

Continuous or lifewide learning takes into account the changing needs of individual life situations and different ways of learning. One of the key focuses of Aalto University’s lifewide learning is small learning modules that include various elements, such as microlearning or degree courses.

Microlearning is characterised by its short duration and focus on one idea at a time. It is at its best captivating and can easily be integrated into everyday routines, for example, by listening to podcasts.

All the offered education is based on the latest research and degree education. You can study either online or on campus, selfpaced or intensively with a group. The individual courses, modules, lectures and micro-credentials serve an acute need for information, whereas more extensive continuous professional development and degrees are suitable for updating knowledge in the long term. You can complete study modules even without being enrolled in an educational institution.

There are over 400 courses and programmes available, ranging from small learning modules to continuing education programmes and complete degrees.

Aalto also offers tailored study packages for companies’ needs. The first example of this is the collaboration that started in January with Murata Electronics. A website was created for the company with the selected courses on topics such as artificial intelligence, robotics, machine learning, big data, production technology, electronics, and management and communications.

lifewidelearning.aalto.fi

Microlearning and other tricks for studying

in the world Aalto University in QS World University Rankings 109th

Studio

Jenni & Jukka

6 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33 NOW

Workshop honours

Vaisala founder

Electrical engineering students get hands-on experience right from their first year of studies. The bachelor’s programme includes an electrical workshop course, where student groups get the opportunity to design and develop a functional electrical device. Participants do not need prior experience in design or coding, as everything is taught on-site. The course is for many one of the most enjoyable experiences during their study time. In addition to electrical engineering students, more and more enthusiastic participants from all Aalto University schools join in year after year.

The space for the course, the electrical workshop located at Maarintie 8 on the Otaniemi campus, was given a new name when it was inaugurated as Vilho Väisälä’s workshop in September. Vilho Väisälä (1889–1969) was a Finnish intellectual, inventor, and founder of Vaisala Oyj. He is one of the pioneers of Finnish high technology, whose curiosity and experimental approach combined with a scientific mindset led to unparalleled inventions. Now his work inspires students in renewed and larger workshop facilities.

‘In addition to the electrical workshop course held twice a year, the space is efficiently used for other courses as well. The workshop has great significance in our teaching; it allows students to put their learning into practice,’ says Dean Jussi Ryynänen.

‘The creative and humorous electronics projects carried out by students in the workshop teach important skills in problemsolving and teamwork. The workshop’s activities also encourage Vaisala’s personnel to continue Vilho’s legacy,’ says Ville Voipio, Chairman of the Vaisala Board.

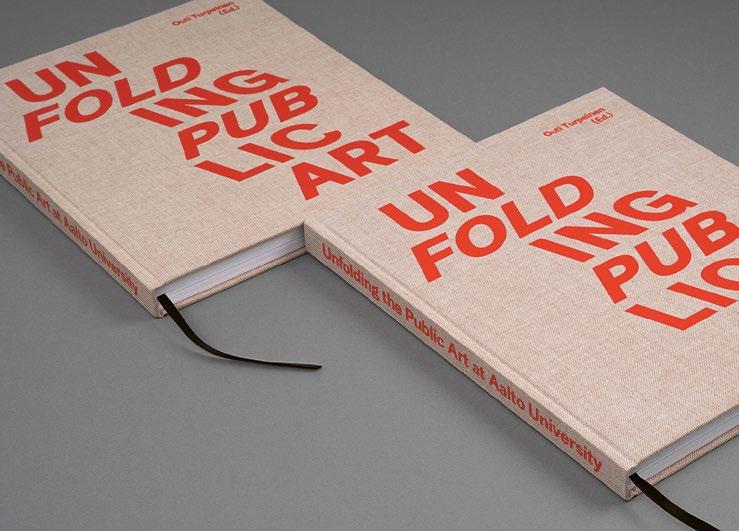

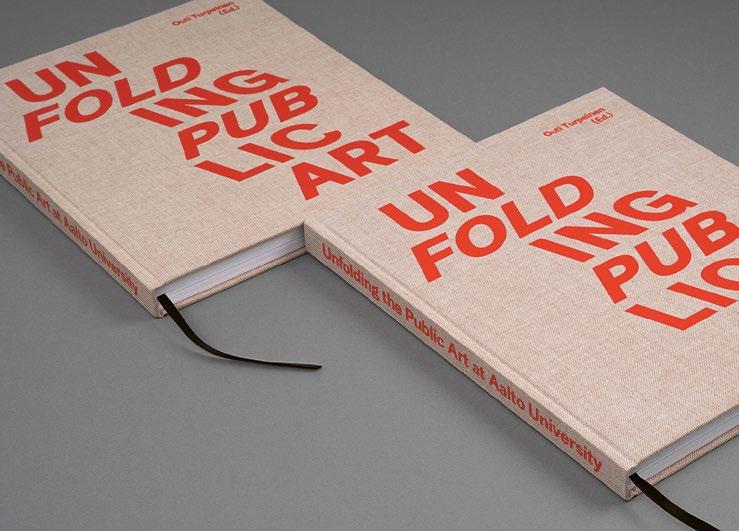

Exploring the role of public art

Why does a university acquire art? What is the role of art collections on campus?

Published in May, the book Unfolding Public Art delves into the principles, acquisition, challenges, and opportunities of public art collections at the university. The book is edited by Outi Turpeinen, Manager of Art and Exhibitions at Aalto University.

‘In the university’s experimental environment, we can test works that do not yet exist elsewhere, because nothing new could happen without experimentation,’ says Turpeinen.

The book comprises nine thematic articles that examine public art from the perspectives of well-being, economy, design, aesthetics, and curation.

Since 2017, Aalto University has followed the one percent art principle in its construction projects, allocating about one percent of the project budget to art acquisitions.

The book is published by Aalto ARTS Books and is available in print and as an e-book from the Aalto University Shop.

The visual design of the book is by Ilona Ilottu, Dog Design.

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33 \ 7

Petri Salmela / Dog Design

NOW

THE EXHIBITION KUROTUKSIA –HIGHER POWERS plays with geometry, symmetry, and organic forms. The artworks were created during an interdisciplinary course titled Crystal Flowers in Halls of Mirrors: Mathematics Meets Art and Architecture. The eight pieces in the exhibition were displayed from June to August, suspended from the ceiling at Heureka Science Centre, approximately three metres above the ground.

The artwork Ocean’s Curtain draws inspiration from looking at the water’s surface from underwater. The creators of the piece are students Helena Hartman, Seyed Alireza Fatemi Jahromi, Meri Aho, Xiao Mou, and Irmuun Tuguldur.

NÄYTÖS23 took place in May on the Otaniemi campus. The annual fashion show by Aalto students is one of Finland's most important fashion events and part of Helsinki Fashion Week.

The main award of the show was given to Master’s student Ruusa Vuori's collection. According to Vuori, clothes can expand or narrow the wearer's personal space, set boundaries, or break them. Conflicting materials and handmade work are an essential part of her approach.

All collections and the show online: aalto.fashion

Mikko Raskinen

Mikko Raskinen

Mikko Raskinen

Mikko Raskinen

8 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33

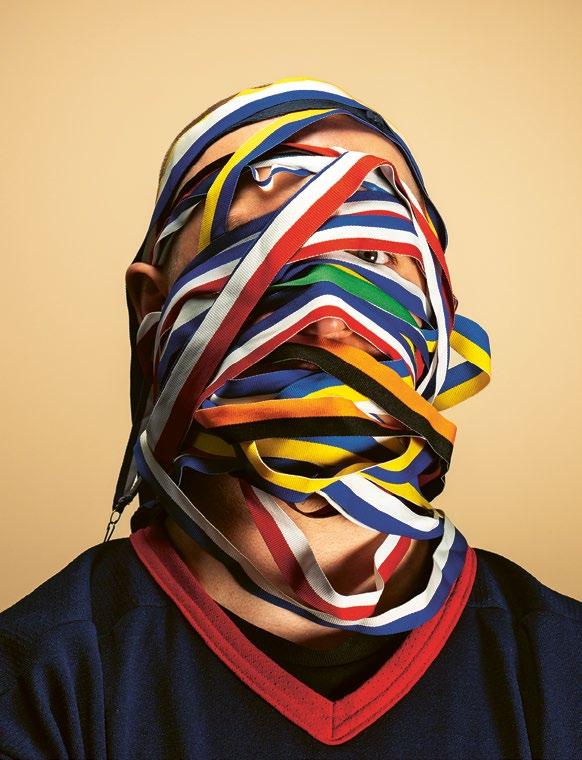

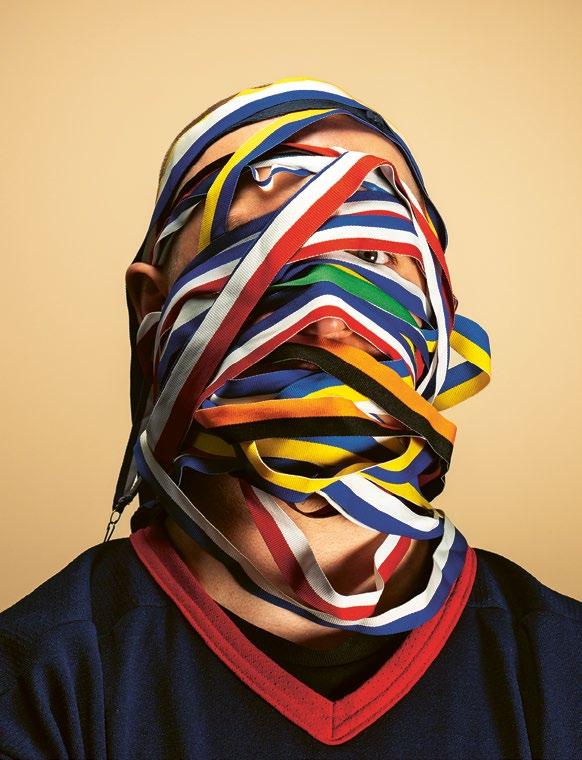

THE ARTEFAKTI EXHIBITION showcases works related to the MA Programme in Contemporary Design from 14 students. The image is part of Vertti Virasjoki’s series, in which he examines masculinity and manhood through the lens of sports, especially ice hockey.

The exhibition is part of the Helsinki Design Week programme and on display at Merikortteli (Pursimiehenkatu 29, Helsinki) until 13 September.

HUHTA is an artwork designed by Master’s student Sesilia Pirttimaa, composed of 870 handcrafted glass elements. The artwork symbolises a cleared coniferous forest that yields a bountiful harvest.

Huhta and another glass artwork, Bread for the Coming, designed by Master’s student Liv Telivuo, are donor artworks and located in the main lobby of the Väre building at the School of Arts, Design and Architecture (Otaniementie 14, Espoo). With these artworks, the university aims to express gratitude to its donors. The names of the contributing supporters are engraved on the accompanying plaque by the artworks.

Anne Kinnunen

Vertti Virasjoki

Anne Kinnunen

Vertti Virasjoki

Hey, take a break at the construction site!

“What is the use of a house if you haven’t got a tolerable planet to put it on?”* American philosopher Henry Thoreau’s question is more relevant today than ever before. The environmental impacts of construction threaten the Paris Agreement on climate change and our efforts to stop the sixth mass extinction.

Half of the world’s annual consumption of raw materials and about 40 percent of energy consumption go towards the built environment. The construction industry also generates over one-third of all greenhouse gas emissions, and 90 percent of biodiversity loss results from raw material extraction.

As our planet’s population continues to grow and more people can afford to live more comfortably, construction will consume more energy and materials. By the 2050s, the increased production of cement, steel, aluminium and plastics alone is expected to produce nearly double the emissions budget we have left if we’re to keep global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Our planet cannot sustain current construction practices – a change in direction is urgently needed. Fortunately, the laws of nature do not prevent limiting emissions. Accomplishing that is largely a question of how we practise and profit from construction.

Laws and agreements are needed to correct the situation, but their effect is too slow to successfully limit emissions. We also need a change in values. That would guide our actions more quickly than regulations, which take years to come into effect.

In developed countries with stable population growth, non-essential new construction should be postponed until we find sustainable construction solutions. In the meantime, we should focus on reusing existing buildings and renovating old ones.

Developing countries and areas recovering from wars or natural disasters should have the right to build their way out of poverty and misery. But even in these cases, construction has to fit within our shrinking global emissions budget.

These principles may be difficult to accept. Why shouldn’t we enjoy a high standard of living and build new shopping centres? What would happen to employment, industry, and tax revenues if we started genuinely downshifting construction? And surely Finland doesn’t have to come up with solutions to the global problems of construction, right?

These questions are challenging. There are no easy answers, but answers must be found – and quickly. In the meantime, let’s pause construction wherever possible.

* From Thoreau’s Familiar Letters.

The Time Out! exhibit at Cooler Planet addresses construction reduction. Check it out at Väre (Otaniementie 14, Espoo) at Designs for a Cooler Planet until 6 October 2023.

Matti Kuittinen

The author is an architect and Professor of Sustainable Construction at Aalto University. He previously worked at the Finnish Ministry of Environment, where he was responsible for the climate aspects of the construction law reform and developed a method for assessing the carbon footprint of buildings in Finland. Kuittinen is active in climate work in the construction sector in Europe and the Nordic countries.

COLUMN

12

18

22

24 On the go Defining radical creativity with a documentary film.

32

35

36 On science Finnish clay can solve the crucial problems of concrete.

MAKING THE INVISIBLE VISIBLE

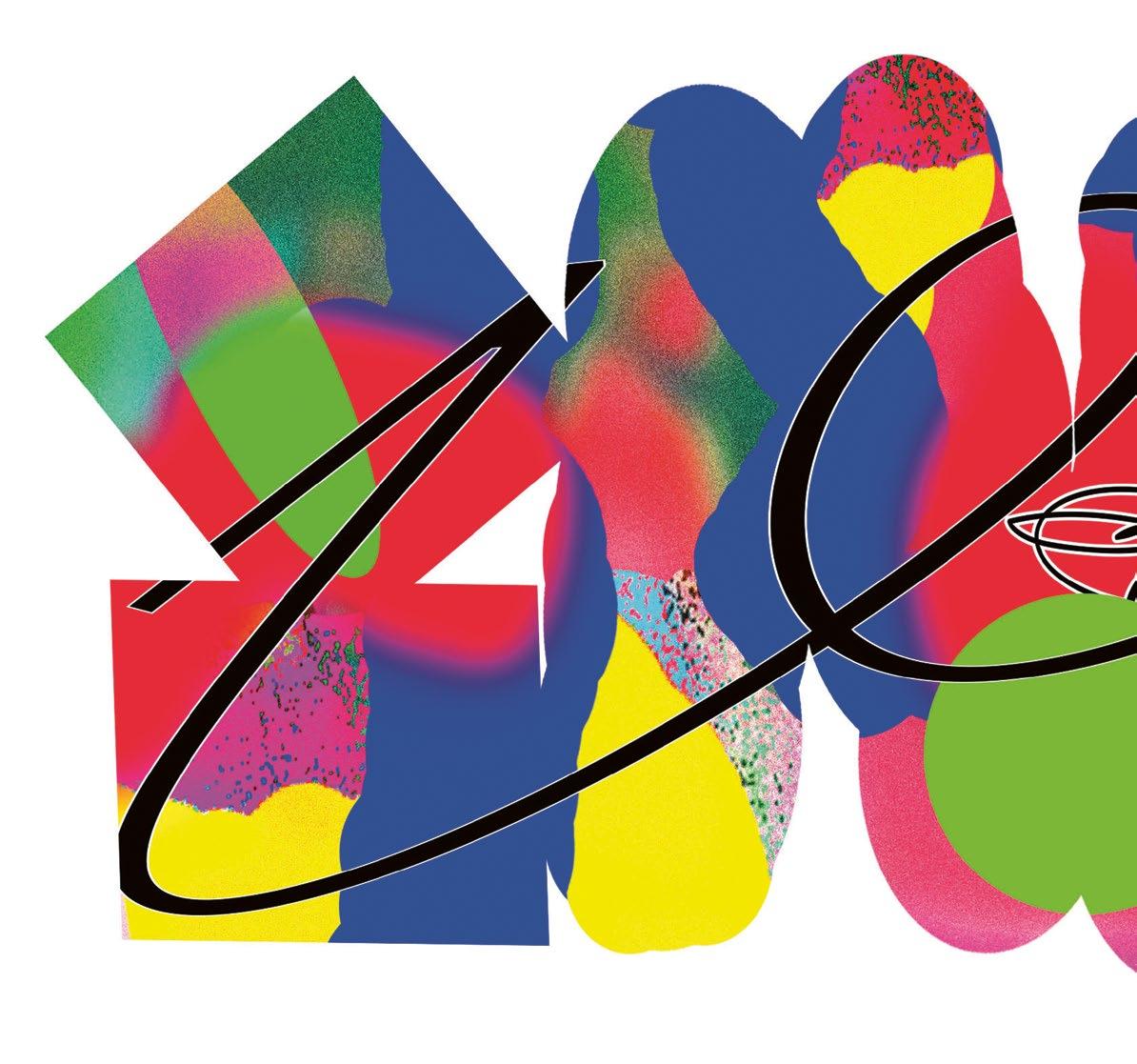

Iikkamatti Hauru

THEME

Theme _ Einat Amir, Astrid Huopalainen and Matti Nelimarkka speak about the invisible wield of power.

Who _ Alma Muukka-Marjovuo makes the basic art education visible.

On science _ Tiny sensors open-up huge prospects.

Dialogue Maria Joutsenvirta and Jani Romanoff recognise resilience.

Wow! Jesse Jalonen’s camera sees invisible people.

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33 \ 11

If we could see under the surface, would we make different decisions?

Whenever humans interact –with other humans, animals or technology – there are always power dynamics at play. Three researchers from different disciplines explain how they bring to light the hidden ways power is used in human interactions.

REVEALING THE DYNAMICS OF POWER

Getting rid of egos and assumptions

Einat Amir tackles big issues as an artist who collaborates with scientists. In her PhD, which combines art and neuroscience, she explores how people working together can make a real change in the world. Specifically, she looks at ways to unlock the invisible dynamics of interactions, and one way is for people to let go of their assumptions, status, and ego.

‘The key to dismantling power structures and power dynamics is to face the other person without prejudice and with an open mind: to genuinely listen to what they have to say and to try to understand who they are and where they come from. At the same time, you have to be generous, share information and your views, and create a common language you both understand.’

THEME Invisible

Text Tiina Forsberg

12 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33

Illustration Iikkamatti Hauru

Amir previously explored the dynamics of power in her art, such as a combined experiment and with performance art she did in Chicago in 2018 with social psychologist and empathy researcher Yossi Hasson. In the experiment, 108 people went through an experience similar to an immigration interview. The idea behind the experiment was that by making people believe that empathy is not limited resource, they will extend empathy to more people, even if they are from other groups. The interviews were conducted by African American actresses, and though some of the questions were funny (for example, ‘Are you lonesome tonight?’), empathy levels were explored through real stories of Syrian refugees.

‘Many people assume that their empathy is somehow limited. In the performance, we kind of played with this assumption to see if we could make the participants more empathetic towards people outside their own social group. It was astounding that a simple manipulation of framing really worked, and people left with more empathy towards the “others”.’

Amir, who prefers to call herself a ‘science enthusiast’ instead of a scientist, is now in the final stages of her doctoral studies. While she has collaborated with different scientific communities, she’s often been the only one with an artistic background. For Amir, being

Einat Amir

WHO performance artist, doctoral researcher, Department of Art and Media, and Department of Neuroscience and Biomedical Engineering at Aalto University

WHY

‘Around 2015, I approached a social psychology lab that deals with intergroup conflicts, conflicts between different groups in different societies, and I expressed an interest in understanding more about the dynamics of power.

Professor Eran Halperin from the Hebrew University just basically opened the door for me and said, “You’re welcome to be part of this lab.” I ended up being the only artist member there for several years.’

NOW

‘I’m currently working on my PhD article on a new generation of art-science collaboration. The subject is how scientists and artists could work together better for societal and environmental change.’

the ‘other’ has provided tools to dismantle the hidden power dynamics in human interactions.

‘The “other” always has the potential to be looked down upon or ignored. There are a lot of stereotypes and assumptions about what it means to be an artist or a scientist. Instead, you could just be two people who are creative in your own ways and are able to share this creativity and create something together that hopefully has a real social and environmental impact.’

According to Amir, true collaboration isn’t about a combination of different statuses or disciplines, but of people. ‘And trust is essential –it’s the basis for all good relationships.’

Building empathy through animals

When you live as a human in a humancentred world, you rarely consider that animals interact with, and work for and with humans in various roles.

In her research, Associate Professor Astrid Huopalainen explores the conscious and unconscious uses of power in human-animal interactions. Even something as trivial and endearing as walking a dog reveals the inequality between humans and animals – something Huopalainen also recognises in her everyday life. ‘When I walk my Labrador retrievers Saga and Selma in the morning, I try to pay attention to how they see the world differently than I do, sensing and smelling different things. That urges me to stop and reflect and perhaps try to see things differently, activating my senses and seeing these positions of power from their point of view,’ says Huopalainen.

She points out that hundreds of millions of humans work with animals daily, and the economic impact of human-animal interaction worldwide exceeds the gross domestic product of many countries. Yet the multiple roles, wellbeing and agency of animals have been overlooked not only in her field, organisational research, but also in society at large.

‘Many people assume that their empathy is somehow limited.’

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33 \ 15

THEME Invisible

There’s very little awareness of the power relations between humans and animals.

Humans relate very differently and sometimes also paradoxically to different animals, says Huopalainen. For example, big mammals are easily admired, but there are many small animals that we barely notice.

We have companion animals or animals we share our homes with, and farmed animals whose existence we rarely want to think about. There are customs and police dogs who help in occupational roles, as well as animals that many people fear and avoid, such as insects or snakes. According to Huopalainen, recognising the agency of these different animals is essential, especially because we live in a world of crises.

‘We have the climate crisis, biodiversity loss and numerous other problems, such as pandemics, caused by humans. We need to understand that we have caused these problems by putting ourselves at the top of the power pyramid, by exploiting and using nature and animals.’

Huopalainen feels that the survival of humanity and the planet depend on recognising the agency of these invisible ‘others’ and on treating animals ethically, whether cute fluffy pets or farmed animals.

‘By dismantling these power structures, we can act as individuals and consumers for a better multispecies planet and a more sustainable future. Awareness and knowledge don’t just increase empathy towards animals but also between people.’

Behind every algorithm are human choices

Matti Nelimarkka holds a PhD in computer science, but he also has background in political science.

In his research, he’s particularly interested in the relationship between human and machine, or politics and technology, and in the invisible use of power through algorithms – a topic which he says hasn’t yet been fully explored.

‘The study of human-computer interaction often leaves out things that are obvious to political scientists, such as certain aspects of decision-making and democracy.

Nelimarkka isn’t entirely comfortable with the term algorithm. ‘Personally, I like to talk about “algorithmic systems”, because that focuses attention on the role of people and organisations as the drivers behind an algorithm.’

An algorithm or algorithmic system isn’t formed from nothing; a human being is always behind it – probably on several different levels. The ideas, wishes or demands behind the code can come from the developer or

Astrid Huopalainen

WHO

assistant professor (tenure track), Department of Management Studies, and Department of Art and Media at Aalto University

WHY

‘I started here at Aalto in January in this exciting position called Leadership for Creativity, which belongs to two departments. I believe this is really a place where you can do very exciting multidisciplinary work.’

NOW

‘I’m part of a cross- and multidisciplinary collaboration with veterinary and healthcare scholars, and the Academy of Finland just granted funding for our PAWWS project. We study human-dog working relations in organisations, such as therapy-, pain- and cancer-dogs at work in hospitals.’

from further along the decision chain, such as from a client or consumers.

‘Software is never neutral. There are always decisions and choices made based on someone’s values or ideologies.’

Whose conscious or unconscious opinions drive an algorithmic system? Is it the human or the machine who holds the power?

Nelimarkka points out that technology is always produced by humans and reflects their values. This remains true in the age of artificial intelligence.

‘For example, in the development of OpenAI’s software, a lot of time was spent removing content that was deemed politically incorrect. In this way, the technology is socially shaped to fit the existing political reality. Even with AI, humans ultimately decide how much autonomy it has in different situations and how it interacts with the rest of the system.’

Nelimarkka also points out that the invisible power of algorithms isn’t always bad. ‘I'm not saying that technology is neutral, but I would like to say that the same technology that is really bad in one sense also does a lot of good in another.’

He cites Facebook as an example: while extremists can use it to find each other, people with a rare disease can also find the few others with the same condition and form a support group.

16 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33

Nelimarkka says that countless issues have been handled badly in societies for hundreds or even thousands of years, and those same issues are re-emerging in the age of digitalisation and being discussed in a totally different light.

‘What amuses me most about the current debate on algorithms is that there is a lot of concern about, for example, inequality in decision-making. Humans everywhere have made terrible decisions throughout history – and we still do. But, somehow, it's supposed to be totally different now that artificial intelligence is involved.’

And Nelimarkka points out that even as algorithmic systems are gaining more and more power over our lives, humans are learning to cheat the systems. ‘People’s competence to see behind these systems is improving all the time. That being said, many still give too much credit to technology rather than to human agency.’

Matti Nelimarkka

WHO researcher, Helsinki Institute for Information Technology (University of Helsinki and Aalto University)

WHY

‘During my studies, I spent a lot of time wondering where I should position myself between political and computer science. In Finland, I had been the one political scientist who coded, but when I attended the University of California in Berkeley, there were several political and social scientists who coded. That’s when I realised that this is really important, because by combining these you can do things that might otherwise be too difficult and might remain in the shadows.’

NOW

‘In our research project, we are trying to highlight how the ideologies and values of software developers influence the design of information systems. We are writing an article and perhaps even a book on the subject.’

‘The same tech that is really bad in one sense does a lot of good in another.’

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33 \ 17

Echoing a kindred spirit from a century past

Counsellor of Education Alma Muukka-Marjovuo grew up surrounded by art. Now she works to ensure that all children and young people in Finland have access to top-notch art education.

When Alma Muukka-Marjovuo was working on her dissertation about Lilli Törnudd, she had no inkling that her career would align so closely with her research subject’s. By chance or destiny, that is exactly what came to be.

Törnudd was Chief Inspector for the Finnish National Agency for Education from 1918 to 1927, when it was called the National Board of General Education. Muukka-Marjovuo, in turn, was appointed as a Counsellor of Education to the Finnish National Agency for Education in 2020. She is responsible for basic education in the arts – after-school arts education provided by local art schools – and for dance and music in basic and general upper secondary education.

The foundation for her career was laid in the playgrounds of her childhood. Muukka-Marjovuo, who practices various forms of art, recalls with particular gratitude the long summer holidays, which now appear to her as a kind of lost paradise. As a child of two teachers, she got to spend summers at the cottage, free from any obligation.

‘We ran around naked, drew, painted and played music. If we happened to find some clay, we made wonderful art out of it.’

Second qualification helped career take off

It was her love for music that set Muukka-Marjovuo on the road to becoming an art professional. She started learning piano at age five and pursued it with determination, and she also played the flute.

After completing basic education, she attended Sibelius-lukio, an upper secondary school in Helsinki specialised in music and dance. From there, she went on to study music education at the Sibelius Academy,

one of the largest music academies in Europe. A second-hand white grand piano followed her from one student apartment to another, and teaching at a music institute provided her with valuable work experience.

After graduating in 1993, Muukka-Marjovuo became a substitute teacher at her old secondary school, teaching music history, piano and chamber music. She enjoyed the school’s ethos and loved her job, but the Finnish recession in the 1990s cast a shadow of uncertainty over her future. A couple of years later, she decided to get a second qualification in visual arts education to improve her chances of getting a permanent position.

Being accepted into the University of Art and Design Helsinki (now Aalto University) was a stroke of luck for Muukka-Marjovuo. It helped her clinch the permanent position she wanted and, over time, culminated in her doctoral dissertation and a compelling career in administration.

A fortuitous find

After twenty years of teaching, Muukka-Marjovuo wanted to delve deeper into the heart of her profession. She found the subject for her research by accident when she stumbled upon a teaching methodology textbook by Törnudd, published in 1926, in the school attic.

Törnudd, a pioneer in drawing and crafts education, believed that ‘art should not be a subject but an educational principle.’ She aspired to position art and science as equals in the realm of education.

Initially, Muukka-Marjovuo planned to explore contemporary interdisciplinary teaching

WHO Invisible

Text Annamari Typpö

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33 \ 19

Photos Aleksi Poutanen

materials, but finding Törnudd made her reformulate her research question. She had discovered a kindred spirit from a hundred years ago; both were interested in the integration of different art disciplines.

‘Lilli wrote about interdisciplinarity in art during the early 1900s, a concept that is now considered a new trend. It was very avant-garde,’ she says.

Avant-garde approaches were also part of MuukkaMarjovuo’s dissertation process. She wanted to understand Törnudd’s era, personality, and methods by immersing herself in that world. She portrayed Törnudd on stage, experimented with Törnudd’s techniques with Aalto University art students, and even wore her grandmother’s black teaching gown from the 1920s.

‘I wanted to see how these more intuition-based, non-cognitive methods could be used in academia. From my current administrative perspective, that feels quite audacious,’ she says. ‘It was also interesting to notice how certain doctrines and areas of interest have a tendency to reappear in different historical periods.’

Making basic education in the arts visible Muukka-Marjovuo completed her dissertation in 2014. After returning to her work at Sibelius-lukio and teaching history of art education at Aalto University for some years, it was time to embark on a new journey.

‘I’d been teaching for a long time and had also tried my hand at research, but the compensation from that isn’t sufficient to support a family. In life, thankfully, one thing leads to another – or perhaps it was Lilli’s ghost who snatched me onto this path,’ she says. Now, as Counsellor of Education, she spends her workdays offering guidance and dealing with developmental initiatives and administrative chores.

‘For a couple of years now, we’ve focused on strategy and quality management and developed metrics and data collection processes for basic education in the arts,’ she explains. ‘There’s an overwhelming amount of data collected from basic and secondary education, but basic education in the arts remains relatively unexplored.’

The first step is to get a full picture of the current situation. State-funded educational institutions are well documented, but not privately and municipally funded institutions. Now, Statistics Finland will start collecting data on institutions outside the state funding system. ‘Having a comprehensive understanding of the entire ecosystem is essential when making decisions about the development of this form of education as a whole.’

National strategic indicators to guide the quality of basic education in the arts will be published in 2023. By December, the Finnish National Agency for Education will also publish a new, user-oriented model so education providers can assess the quality of their services.

Several areas for improvement have been identified, including accreditation and registration of basic arts studies. From the beginning of 2023, these studies have been recorded in a centralised register, just like other academic achievements.

‘Now, the skills gained through extensive studies across diverse art disciplines are more visible when a student applies to upper secondary education or enters the job market,’ says Muukka-Marjovuo.

‘It’s a significant step.’

Local elements missing from curricula

The primary task of the Finnish National Agency for Education is to draft the national core curriculum. The next round of reforms will be the first in which Muukka-Marjovuo is involved right from the start.

She gained practical experience and insight into curriculum work through teaching and by contributing to Helsinki’s most recent municipal curriculum. Muukka-Marjovuo advocates for more local focus in municipal curricula, stressing the need to acknowledge a region’s strengths, natural and historical attributes, and socioeconomic and cultural context.

She offers Lemi, where some of her family roots lie, as an example. ‘In their curriculum, they should include things like four-part singing as well as sustainable sheep farming and the Särä tradition,’ a traditional South Karelian lamb roast prepared using a thousand-year old recipe.

The most rewarding aspect of her work as Counsellor of Education is making things better through administrative changes, such as successfully campaigning for the equal recognition of different art disciplines. Muukka-Marjovuo is deeply invested in supporting people who need help and maintaining the abilities of people who are already doing well. She also enjoys on-site visits, networking and collaborative efforts.

Cultivating good citizenship through art education

Lilli Törnudd saw art education as a valuable catalyst to bridge societal divides, and she was involved in making art an integral part of school curricula. Compulsory courses in music and visual arts are now part of both basic and upper secondary education. ‘In Finland, the ethos of education maintains that art education is crucial to the development of a well-rounded citizen. Globally, this is a rarity,’ says Muukka-Marjovuo.

She shares Törnudd’s view that education, in all its forms, should encapsulate the spirit of investigation and questioning inherent in the realm of art. At its core, art has a unique ability to reshape thoughts and give a momentary view of life as a playful pastime that promotes well-being.

‘That vision is precisely what skilled art and music teachers pass on, alongside skills and techniques,’ she says. ‘And they preserve the connection to that childhood paradise.’

WHO Invisible

20 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33

Alma Muukka-Marjovuo

• Graduated with a Master of Music degree from Sibelius Academy in 1993 and a Master of Arts degree from the University of Art and Design Helsinki (currently Aalto University) in 1998.

• Earned a Doctor of Arts degree from the Aalto University School of Arts, Design, and Architecture in 2014.

• Works as a Counsellor of Education at the Finnish National Agency for Education, where she is responsible for basic education in the arts and for dance and music in basic and general upper secondary education.

Is also

• An avid gardener: ‘My garden in Käpylä, Helsinki, is an important part of my well-being at work.’

• Member of a vocal ensemble: ‘We performed at the Kaustinen Folk Music Festival this summer. The ensemble mostly writes its own songs.’

• Versatile and adaptable art enthusiast: ‘When my children were young and time was scarce, I painted quick watercolours and wrote poems. As a secondary school art teacher, I had the opportunity to design and implement several stage sets with my students, and I also scripted and directed some plays. Now, my husband and I dance swing together. Playing the piano has always been a significant part of my life.’

How to see trees and plants in a whole new light

When you look at a tree or a plant from a distance, how do you know if it’s healthy or not? ‘Looking at trees from the outside, you cannot necessarily tell with your eyes if the tree has been attacked,’ Mikael Westerlund says.

In Finland, foresters are reckoning with hidden invaders that infect trees: a fungus that causes rot and pests like the bark beetle are becoming more common under climate change. Such infiltrators spread from tree to tree, often hidden within the trunk and roots until it’s too late. Tens of millions of euros are lost to the damage each year.

Knowing whether or not plants are thriving is also a challenge in agriculture, Westerlund, a business developer at Aalto, explains. He asks you to imagine you’re a farmer running a commercial greenhouse: ‘Are you using too much fertiliser or too little? Do you have too much lighting or not enough? Do you have a pest problem, or are you applying too much pesticide?’

Experienced growers can find answers by examining their plants up close, but in large-scale farming it’s necessary to monitor enormous fields of crops from a distance. Keeping one plant healthy is doable, but hundreds of thousands at once? That’s a bigger challenge.

That’s where a smart new technology comes in. Hyperspectral imaging analyses light to reveal things about trees, plants, and agricultural crops. It allows foresters and farmers alike to monitor vegetation from a distance, revealing details that might otherwise go unnoticed.

But to really understand hyperspectral technology, you first need to know a bit about the nature of light and how cameras see it.

Hidden light

When you take a selfie a sensor inside your phone camera analyses the light that scatters off your face. To construct a picture, it assigns each pixel a mixture of the colours red, green and blue. This is similar to how our eyes work. But through this process, a great deal of information about the light is lost.

When light hits a hyperspectral camera, it is analysed into far more than three colours per pixel. The camera records the ‘spectral signature’ of the light from each point in a scene, taking in much more information about its wavelength and intensity than a standard camera and making measurements across a wider range of the electromagnetic spectrum. It sees things that even our eyes cannot.

Crucially, in the same way that a fingerprint can identify a person, the spectral signature reflected from objects can identify the properties of materials that would otherwise go unseen.

If you took that selfie with a hyperspectral camera, you’d be able to record the unique spectral fingerprint of the melanin, water and hemoglobin content within your skin.

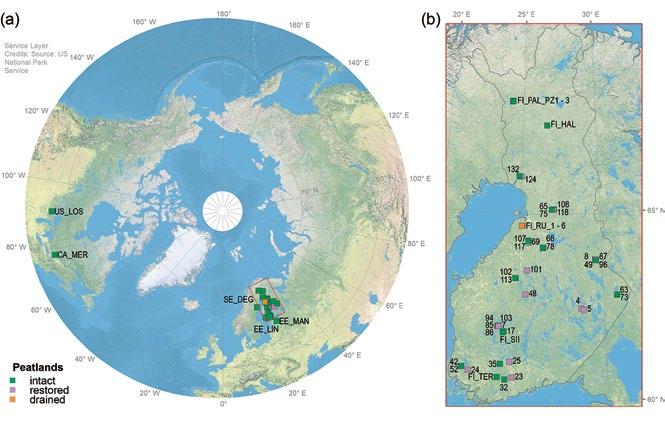

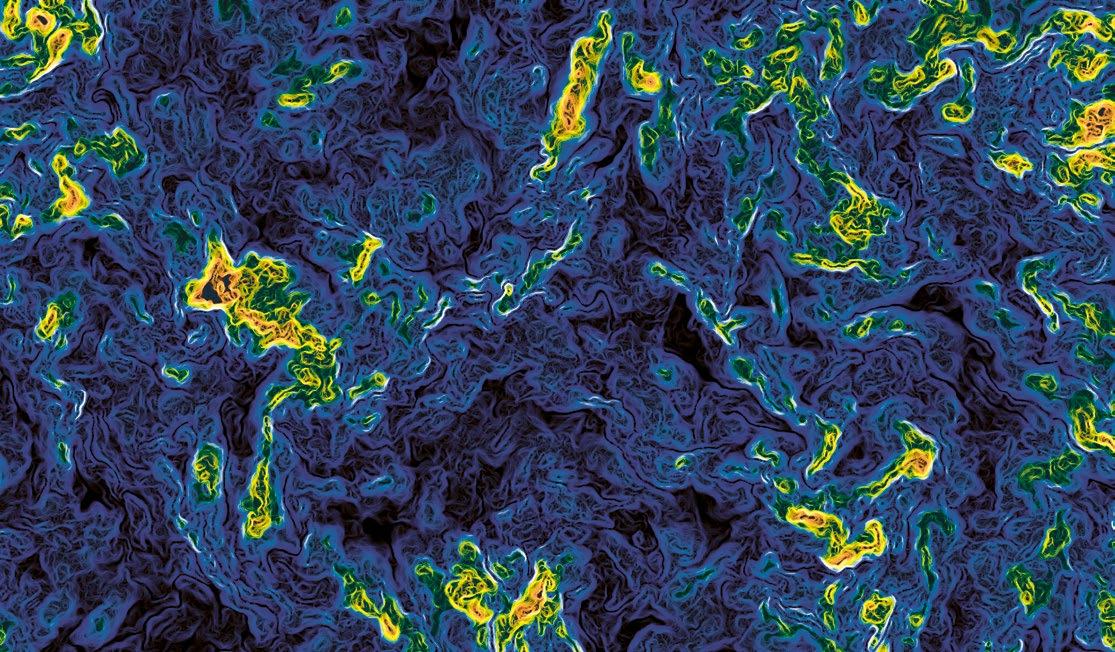

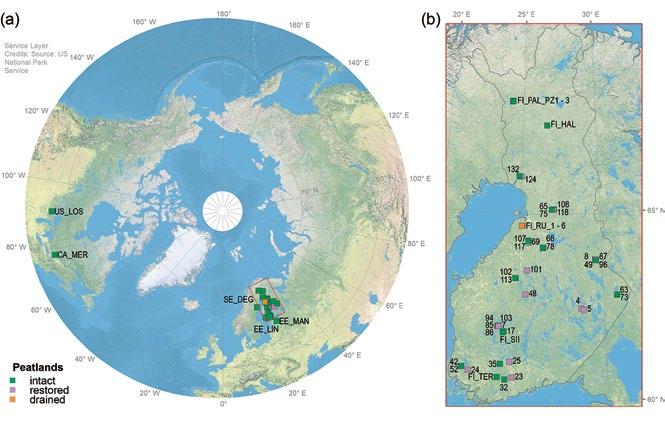

The view from above One research team at Aalto is using hyperspectral imaging as a tool to monitor and understand forests and peatlands. Miina Rautiainen and her colleagues are turning to hyperspectral cameras mounted on satellites –and occasionally planes – to help them model the character of forests and peatlands from up high.

When combined with field observations, this remotely-collated data is helping Rautiainen’s team build enhanced computational models of

the vegetation in three dimensions. In a forest, that means everything from the leaves at the treetops down to the shrubs on the forest floor – as well as how the 3D structure differs over a region.

The team’s modelling can help predict biodiversity, as well as the productivity of the vegetation and its ability to suck up carbon from the atmosphere. ‘That’s something, very interesting at the moment in terms of trying to understand climate change,’ says Rautiainen.

The three-dimensional modelling of the forest can also predict its radiation regime – essentially, how it absorbs and reflecting the sun’s radiation. ‘If we want to forecast future climate scenarios, having a realistic description of the vegetation’s shape or 3D form is important,’ she says.

What makes the hyperspectral cameras so useful is that they can reveal things about forests and peatlands that would be difficult to monitor in-person. ‘With satellite data, we get to cover areas where we don’t have observation networks or where it’s politically impossible to go for fieldwork. Or sometimes it’s just that the regions are so remote: there are no roads, no rivers that we could use to get there.’

Satellites also pass over regions regularly, providing continual updates on changes over time. ‘We can, for example, follow the growing season of vegetation in much more detail than what we would be able to do if we were on the ground doing some fieldwork,’ she says.

Shrinking down

Hyperspectral cameras do have some downsides, however. They are expensive – some cost tens of thousands of euros –and can be relatively bulky and heavy.

ON SCIENCE Invisible

Hyperspectral imaging opens the door for future foresters and farmers to monitor vegetation from a distance, revealing details that could otherwise go unnoticed.

22 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33

Text Richard Fisher

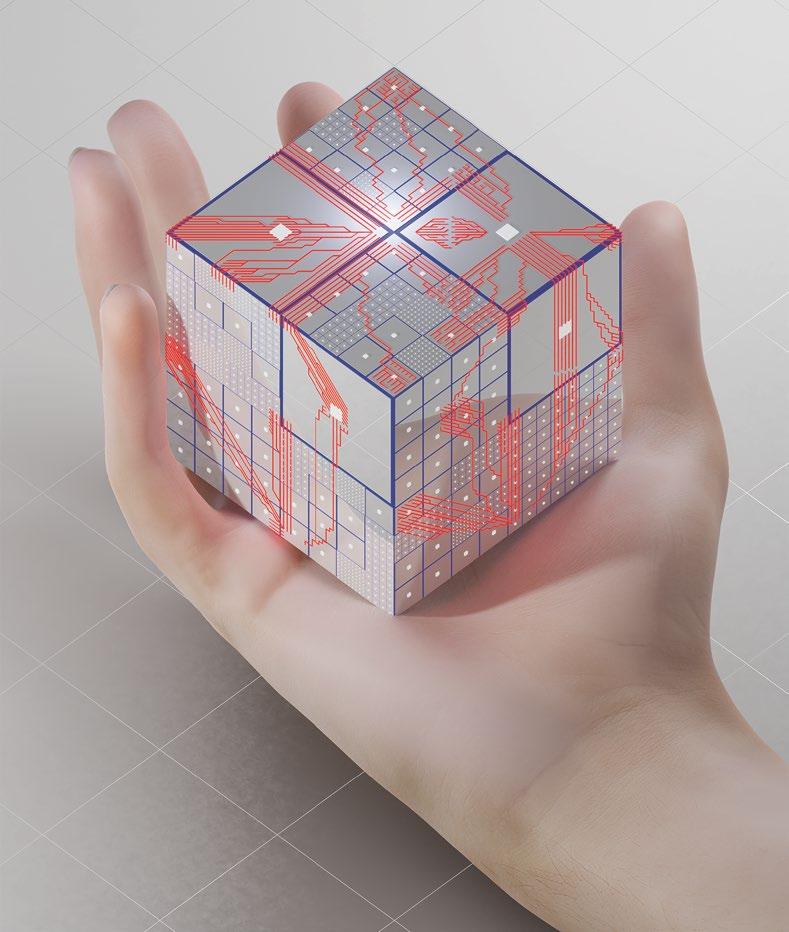

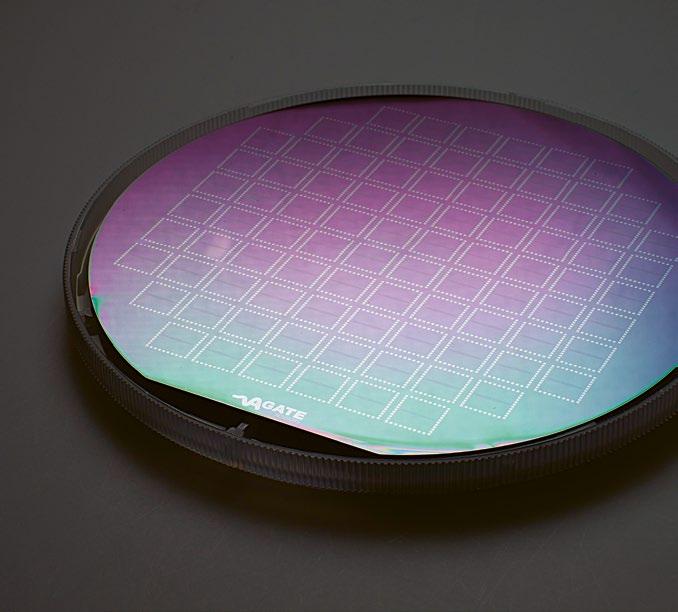

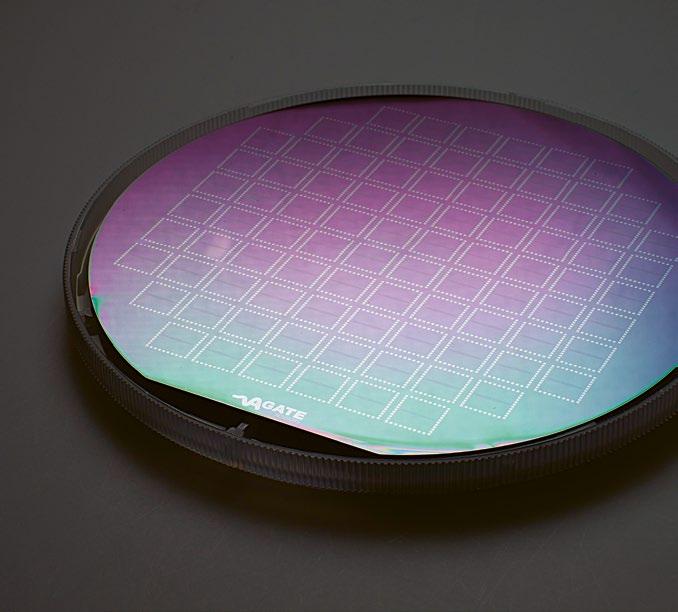

That’s why Westerlund – and a team of scientists led by photonics professor Zhipei Sun are now working to commercialise a miniature hyperspectral imaging sensor they’ve developed. It’s so small that it could one day fit inside a smartphone or a small drone flying over a crop field.

To tune light, traditional hyperspectral cameras use bulky optical and mechanical components. That means a typical hyperspectral camera is often bigger than a kitchen toaster – and quite a bit heavier.

But the team found they could replace these mechanical and optical components by fiddling with the voltage across a clever arrangement of nanoscale two-dimensional layered materials, including graphene. This allows them to control the light electrically. ‘We don’t require large bulky components. We just need to tune the voltage, and the rest is taken care of by an algorithm we built,’ they say.

To commercialise the technology, the team is preparing to form a start-up company called Agate Sensors, which will spin out from Aalto in early 2024. Down the line, they envision a whole host of applications

for their tiny camera technology, from the automotive industry to security technologies.

One area that the Agate team is looking at first is agriculture, allowing farmers to monitor crops over large scales.

Westerlund, who leads the team’s business strategy, credits the team’s successes to the international experience at Aalto, with team members from China, Pakistan, Greece and Finland. ‘I think it’s really beneficial for a project like this to be able to actually view things from different angles and consider different options.’

is as accurate as possible.

The project resulted in a book in which Sheung Yiu combines archival photos, documentary photos and experimental and artistic materials.

The photos of Agate’s sensors (above) and from the Ground Truth project are on display at Designs for a Cooler Planet.

Photographer Sheung Yiu followed the work of Professor Miina Rautiainen’s research group as part of the Ground Truth project, where the structure of trees was measured at close range. The results were combined with remote-sensing data to ensure that the modelling

Anne Kinnunen

Sheung Yiu

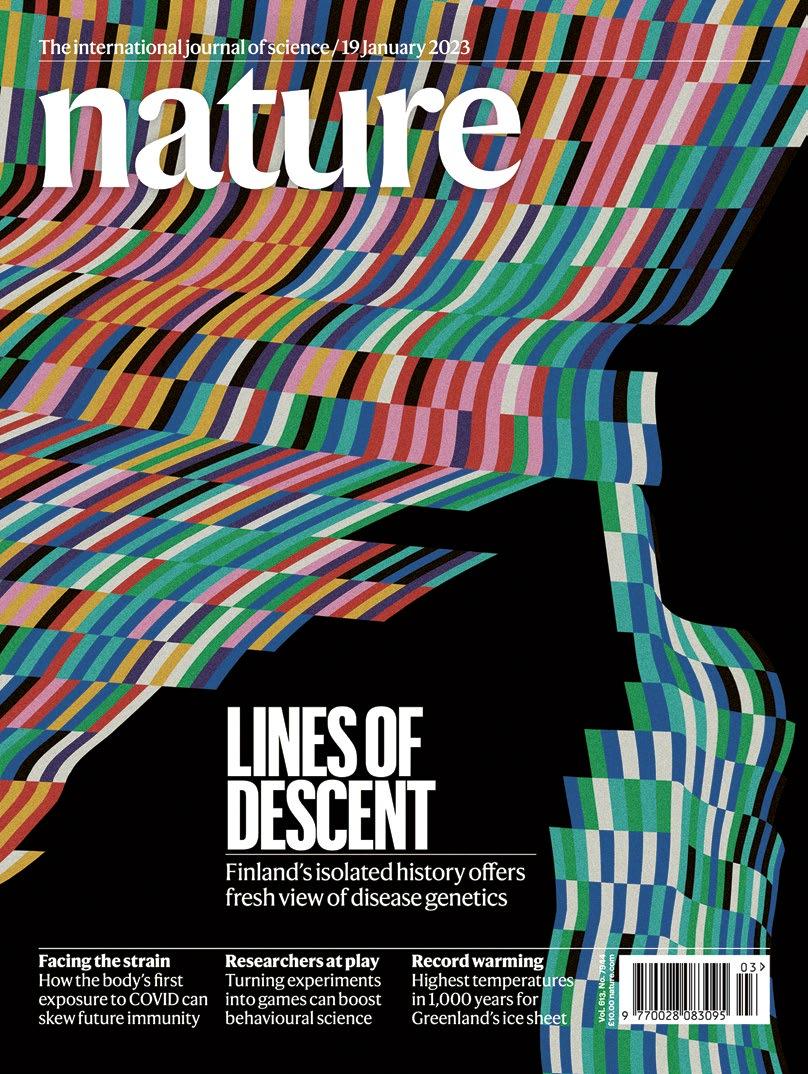

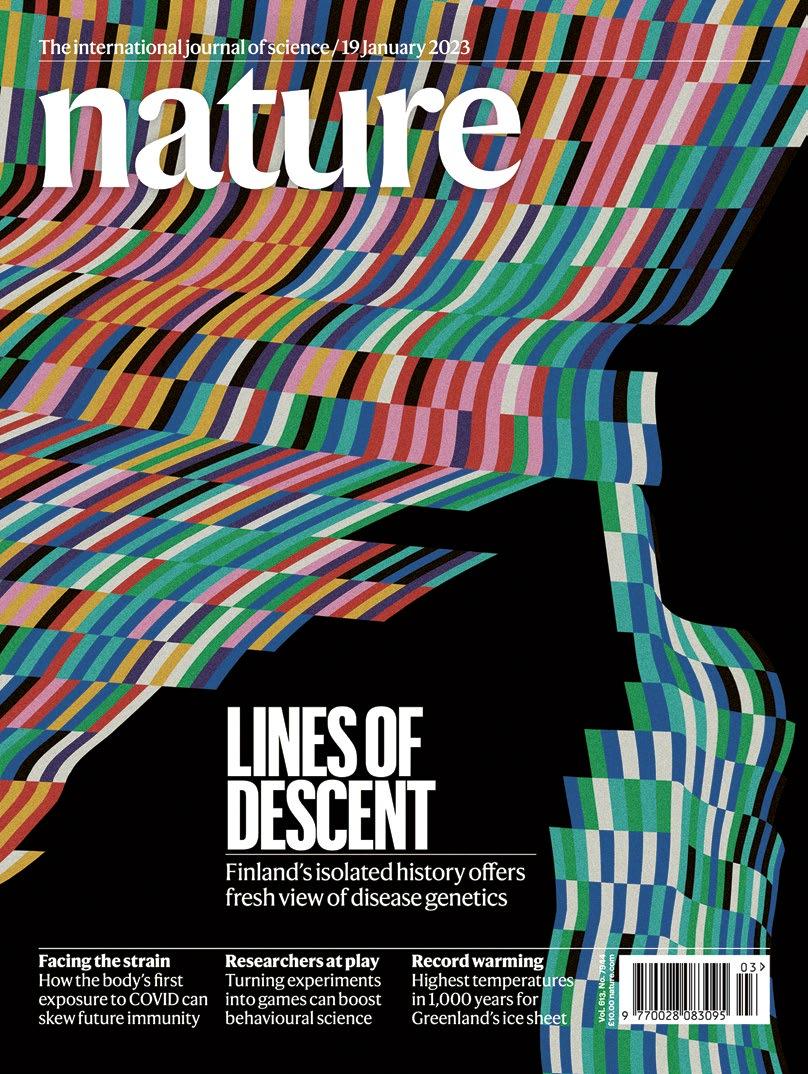

A deep dive into radical creativity

Can we make creative thinking and culture visible through cinema?

Text Tiiu Pohjolainen

Translation Tomi Snellman

Photos Hayley Lê

Clouds hang heavy over the beach at Kallahti, a neighbourhood in eastern Helsinki’s Vuosaari district. The setting is beautiful, but the scene is absurd. A group of people pose at the tip of the headland, with children dressed in peculiar fabrics, others spinning, some walking into the water. The camera seems to follow each and every one of them. Then, it starts to snow. One of the dozen-strong film crew calls out: ‘All the seasons in a single day of shooting – again.’

The people on the beach are shooting a scene for a film about radical creativity. That’s why the camera tracks art student Saban Ramadani as he walks to the shoreline again and again, wrapped in pale strips of flowing fabric. And that’s why mathematics professor Pauliina Ilmonen spins around again and again, dressed in a pink outfit dotted with flowers. Behind the camera, a crowd follows the shoot. The second the camera stops filming, and costume designer Marié Iradukunda hurries to Ramadani to wrap him in warm clothes. Make-up artist Jennifer Appleton comes over to check her work. In the background, set designer Ruut Mantila sweeps her eyes over the entire set.

Water in its different forms plays a unifying role in this documentary. It appears as ice, snow, clouds, streams, and the sea. Some interviewees are also portrayed near water or in the water. Student Saban Ramadani and director Emilia Hernesniemi are preparing for an underwater shoot.

ON THE GO Invisible

24 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33

ON THE GO Invisible

I thought I had come to watch the filming of a dry documentary. I never expected to find myself on a beach in freezing weather, nor had I thought the director would arrive on set wearing sequin pants.

I had assumed that a film produced by a university would focus on innovation and feature talking heads in suits – even one on radical creativity.

Trust and something else

What, then, is radical creativity, the subject of the feature-length documentary?

We can say, at least, that it’s not an asset earmarked for some specific industries, nor is it a skill-set reserved for professionals in art, culture or marketing.

To pinpoint the core of radical creativity, you can start by pairing the power of imagination and play with innovation and problem solving. Don’t forget to add a dash of sisu, the spirit of fortitude or spunk commonly said to have led to the post-war economic boom in Finland.

Radical creativity is about breaking free from the compulsion to succeed; you must let the creative process guide you. In a university setting, that can translate into active – or even foolhardy – efforts, where students not just attend lectures but also head out to go do something and experiment. Radical creativity also produces things that don’t always hit the bullseye.

Risk-taking is an inherent part of the process.

I thought I had come to watch the filming of a dry documentary and assumed it would feature talking heads in suits.

26 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33

Warm gear was needed for the beach scenes filmed in the spring. The chilly weather didn’t hinder mathematics professor Pauliina Ilmonen, draped in pink.

Hour-long documentary

Aalto University has produced the film to highlight its creative culture, and the projects is mainly in the hands of film department alumni. This is no student project or corporate video; it’s rather an independent hour-long piece created by professionals, led by Emilia Hernesniemi, who wrote and directed the documentary.

For Hernesniemi, radical creativity is actually the film’s main character.

‘Instead of a person who I’d correspond with before filming – to get to know them and build trust – the protagonist in this project is an abstract concept.’

Hernesniemi admits that the subject of the film is difficult. That’s what makes it so interesting to film.

‘This is a test for us all. Everyone involved has had to think about how to address radical creativity.’

The schedule is exceptionally tight for the film industry: the premiere is set for less than a year after project launched. The work will, however, pay off; in addition to the documentary, the footage will eventually be used in teaching, including a globally accessible, free online course on radical creativity.

Surface chemistry and street dance

It’s obvious that radical creativity can mean very different things, depending on the context, whether business or chemistry or visual arts. Radically creative thinking is not exclusive to some specific field or context: it can be seen in research, social thinking, business, education, art or design.

In Hernesniemi’s film, people from all kinds of backgrounds speak about the concept from all kinds of angles. One challenge in casting was, in fact, an excess of candidates. With its students, teachers, researchers, artists, stakeholders and start-up founders, the university was faced with a far greater number of compelling interviewees and projects than could be included in an hour-long film.

‘We have 50 hours of beautiful and brainy footage that will be edited into a sixty-minute film,’ says Hernesniemi.

Her challenge in the editing room will be to say goodbye to an endless amount of rich and cherished footage.

Chemistry student Imose Iduozee dances on the steep stairs of the amphitheatre on campus. The choreography is her own, performed to a song called Joro by Afrobeat artist Wizkid. On the quiet Friday night when the scene is filmed, a few passers-by in Alvar Aalto Square turn their heads as they take in the solo performance, which merges street dance with other genres.

Iduozee dances in the documentary, although at times it can be difficult to manage both studies and dance.

‘School is quite demanding, so it’s not easy to juggle my studies with an intensive hobby,’ she says. Iduozee, 22, has hurried through her second-year studies in chemical engineering in order to start her thesis early.

She felt shy about doing the dance scene, even nervous. A choreographer and dancer, Iduozee rarely performs solo in front of an audience. She is more at home as a backup dancer at gigs, such as the one where she was spotted by Nita Rehtonen, the film’s creative producer.

Iduozee has thought a lot about radical creativity as a concept. It is something that recognises no limits. During her studies at Aalto, Iduozee’s own approach has been particularly influenced by

The screenwriter and director of the film is Emilia Hernesniemi (on the right), and the cinematographer is Iiris Sjöblad. Their previous collaborative film, Hei hei Tornio, was awarded the Best Short Film Jussi Award in 2021.

Human rights activist Ujuni Ahmed is one of the interviewees.

a course on academic thinking, which was a complete departure from what she was used to as a chemistry student.

For example, a question in the course might be about how many drops hit the ground if it rains for two hours. There was only the question, with no further information, and in truth no real answer either.

‘You just had to start thinking about the size of a drop of rain,’ recalls Iduozee. ‘For me, the course was really about creative problem solving.’

Nothing new without risk

Aalto University aims for all students to be trained in radically creative thinking and practices as part of their studies.

You could say the idea was pioneered by students in a course on space technology back in 2010, when they told teacher Jaan Praks that they wanted to build a satellite and send it into space.

That spring, development of the Aalto-1 satellite began as a student project.

‘It was a case of radical creativity in that we went all-out on a project with no guarantee of an outcome,’ says Praks, who is now an assistant professor.

When the students started to build the first satellite, no one seemed to believe in Jaan Praks or his team.

‘They just smiled politely at us and our enthusiasm.’

Back in 2010, the young teacher was quite aware of the risks. ‘I must admit I was scared at times. After all, I was risking my own career in the process,’ he says today with a laugh.

The risk paid off: today Praks is known as the man who led the construction of Finland’s first-ever satellite. He is also an educator who has trained a new generation of space technology experts. One of the first trainees, Rafal Modrzewski, appears in the documentary with Praks. Today, Modrzewski is the CEO of ICEYE, a company born out of the satellite project. On camera, the men present a satellite only slightly larger than a milk carton.

A day of shooting in front of a hot-dog stand in Otaniemi finally makes both men shiver from the cold. Before Modrzewski rushes off to his next appointment, Praks has time to ask what prompted the respected scientist to find time in his calendar to shoot the scene.

‘I want to promote awareness of space technology in Finland,’ Modrzewski says. He has talked about mini-satellites and space in nurseries, businesses and podcasts, so why not on film as well?

‘At its core, radical creativity is all about breaking boundaries,’ says Praks. ‘And when you’re there, you don’t think about what your actions look like to outsiders – you’re working for a cause you feel is important.’

ON THE GO Invisible

28 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33

Imose Iduozee is involved in the film as a dancer, choreographer, and a student of chemical engineering.

In addition to the water elements, natural light and various outdoor and working spaces play a central role in the film. The filming has taken place in the fells and on the campus, in lecture halls, libraries, and on the street.

‘We have 50 hours of beautiful and brainy footage that will be edited into a sixty-minute film.’

Professor Julia Lohmann creates large-scale artworks from seaweed.

Film is a craft, too

So why is a professor eating a hot dog with a former student in a documentary about the university? Why is Saban Ramadani diving underwater, and why are children playing on a beach in Kallahti?

I ask writer-director Hernesniemi.

‘I never use reportage as a format for a documentary. My work reflects my background and education.’

Many people, in fact, know Hernesniemi from the world of fashion.

‘Fashion is all about searching for new things by investigating visual material at a dizzying pace,’ she says. ‘My films are not fashionable at all, but their visual aspect, the need to explore visual material, comes from my background in fashion design.’

She enrolled in the Fashion Design programme at the University of Art and Design when she was 19. A year after earning her master’s degree, she had already founded the fashion label R/H with Hanna Riiheläinen

ON THE GO Invisible

The visual aspect of the film stems from the director’s background in fashion design.

30 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33

A satellite just slightly larger than a milk carton, situated between Jaan Praks (on the left) and Rafal Modrzewski, is part of the shoot at a hot-dog stand in Otaniemi. The clapperboard is held by the film’s creative producer, Nita Rehtonen.

Years went by as Hernesniemi worked with clothing, fashion and visual conceptualisation. She even taught fashion marketing at Aalto University and elsewhere.

Then in 2018, she applied and was admitted to study at her alma mater for a second time.

‘As an 18-year-old girl from a suburb of Oulu, I was interested in fashion and design. Growing up, I wanted to study to be a documentary film director.’

Cinematographer Iiris Sjöblad, who shot the documentary, started her studies the same year. ‘We have worked together a great deal and very intensely, Iiris and I.’

Emilia Hernesniemi believes that there is a strong link between visual industries: after all, she herself spent more than a decade creating both films and photographs for the fashion industry.

Fashion design was a good beginning for a film director, starting with project management. And film is a craft, too. Whatever the material, it’s cut and fitted to purpose, be it in fashion or filmmaking.

‘I think it’s cool to be part of the generation that’s building the Finnish culture of today. Visual culture is strong in Finland,’ Hernesniemi says. ‘Visual arts, graffiti, fashion, film, design – they all bring people closer together. We can develop our cultural capital by going to the cinema, taking an interest in local fashion or enjoying Finnish contemporary art.’

Hernesniemi’s documentary reinforces cultural capital by telling the story of a university that holds dear a culture of free experimentation and practice.

During the casting, the university with its students, teachers, researchers, artists, and stakeholders posed a challenge due to an abundance of options. However, the engineering students with their overalls, caps, and ceremonial rods are such an integral part of Aalto University that the story couldn’t be told without them.

Strategic creativity

Aalto University’s strategy has three overarching themes – sustainable solutions, radical creativity and an entrepreneurial mindset – that are embedded in everything the university does.

‘Radically creative thinking and doing can be seen in how Aalto University was founded: it was an atypical combination of excellence in different fields. For us, creativity is a broad subject that touches all of society, one that deserves to be explored artistically through an independent work. We want the topic of the film to touch and inspire ideas in as many viewers as possible,’ Aalto University President Ilkka Niemelä explains.

The film’s executive producers are Milla Kokko from Aalto University and Kimmo Syväri from the production company Koski Syväri.

It's quite unusual, even globally, for a university to choose radical creativity as a strategic theme, Milla Kokko says. ‘In everyday creativity, small steps are taken and familiar things are done creatively. Radical creativity challenges – and shifts – the paradigm, like in the way cars once revolutionised transportation.’

At the time of writing, the film was at the editing stage. The name and the premiere of the documentary will be confirmed later.

Let’s make resilience a community resource – not an individual obligation

Maria Joutsenvirta and Jani Romanoff know resilience – that trendy workplace buzzword – both in theory and through practical experience. The term is often used to refer to tenacity or the ability to recover psychologically, but they also see it as an important professional skill that anyone can learn. But it goes beyond being just a handy skill to pick up. In fact, both Joutsenvirta and Romanoff believe that resilience should be seen as a part of the work community rather than approached as something each of us needs to learn individually.

‘It makes no sense for individuals to try to learn to be more resilient on their own in order to meet the demands of today’s world. Work communities should create conditions where everyone has the space, time, and opportunities to recover – not burn out,’ says Joutsenvirta, a visiting scholar at Aalto University.

‘Many people feel the need to appear strong and confident at work, suppressing their emotions. We beat ourselves up for not being good enough, and we expect the same from others. We rarely tell a colleague that they are doing too much and should slow down,’ points out Romanoff, professor of marine technology and vice dean at the School of Engineering.

A more communal approach

One of the challenges? Joutsenvirta and Romanoff say that most of us have a limited understanding of the scope of our colleagues’ work. In many jobs, people are constantly bombarded with requests from a variety of sources, and work performance is measured with rather narrow metrics.

We can foster a more collaborative approach to resilience by, for example, increasing the transparency of everyone’s workloads and ensuring backup personnel are available for crucial tasks in case of illness.

JANI ROMANOFF IS A PROFESSOR OF MARINE TECHNOLOGY and the vice dean responsible for teaching at the School of Engineering. His research and teaching focus on the development of lightweight structures used in ships. Romanoff has made significant contributions as a teacher and educational developer. He has received awards such as the Aalto University Teaching Impact Award, which is granted for groundbreaking educational work that develops expertise in key sectors of Finnish society.

32 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33 DIALOGUE Invisible

In Romanoff’s research group, everyone creates an annual plan for themselves, which they share with others. This way, the entire team knows when a colleague has a particularly heavy workload.

‘Supervisors can also serve as an important counterforce to an excessively performance-driven mindset. They can question the necessity of unproductive meetings and tasks that contribute very little to the work community,’ Joutsenvirta explains.

‘Absolutely. The wisest advice I have received from a supervisor was to allocate 80 per cent of my working time to actual work. I was scandalised; how could I do that when I get paid for 100 per cent? My supervisor said, “Jani, surprises always account for 20 per cent – and if by chance they don’t, then use that time for strategic thinking,”’ recalls Romanoff.

Embodied Practices with MIT Insights

Put your phone away. Close your computer. Exercise. Jani Romanoff often shares these tips to students who want to improve their resilience.

‘The harder the problem I’m dealing with, the more I prioritise exercise. When I return to my workstation after training, my mind has already solved the problem. I’ve recommended the same approach to many people,’ says Romanoff.

‘I’ve only recently realised that simply urging people to exercise is not enough. Yes, everyone should work out, but resilience can be cultivated in

DOCTOR OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION MARIA JOUTSENVIRTA

is a learning designer specialised in sustainable development. As an independent researcher, author, and facilitator of transformative learning processes, Joutsenvirta works at the intersection of various disciplines and the interface between science and society. She has contributed to the writing of several books.

Text Joanna Sinclair

Photo Jaakko Kahilaniemi

Is there any skill more important in today’s work world than the ability to cope during challenging times and bounce back quickly?

work communities with other methods as well. For example, with collective embodied practices,’ he adds.

Romanoff has served as academic leader in Aalto University’s Oasis of Radical Wellbeing project, which aims at creating holistic wellbeing. Joutsenvirta, in turn, was involved in creating the university’s strategic experiment, Capacity Building of Creative Radicals (CBCR). Both projects have piloted methods for enhancing wellbeing.

Embodied practices, which were explored in the CBCR project, are exercises designed to foster a shared sense of a safe space and self-awareness among individuals, enhancing their ability to tolerate uncertainty. These exercises are based on the systemic change leadership model, U-Theory, developed by researcher Otto Scharmer from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the related methodology of Social Presencing Theater.

‘Embodied exercises help calm the mind, focus on the present, and engage with the emerging reality with brave curiosity. Ideas and insights start to surface that would otherwise remain unrealised,’ explains Joutsenvirta.

‘In the project’s workshops, I clearly noticed how intellectual reasoning provides only one channel for understanding the complexity of the world.’

More emphasis on intuition

Joutsenvirta and Romanoff say that listening more to intuition and the body’s signals can help develop communal resilience within work communities.

‘I am a very kinesthetic person. Often, my body tells me that something is wrong before my mind even realizes it,’ says Joutsenvirta.

‘In a safe work environment, people can share their feelings. They can openly express that not everything feels right,’ she adds.

‘Especially in systemic-level problems, you may first get a gut feeling that something is not okay. But very few of us dare say that hey, I have bad vibes about this, even though I can’t explain it or back it up with solid facts,’ says Romanoff.

He adds that intuition has much less credibility in the workplace compared to facts, even though we also do a lot of work in our subconscious.

‘If you don’t react to the warning signs from the subconscious, you often act against your own values – and usually feel bad.’

Joutsenvirta emphasises that in a crisis-ridden world, work communities need people with both a strong sense of self-knowledge and the ability to take others into account.

‘When we recognise intuitive and emotional messages as important, we gain access to new ways to improve our wellbeing and the overall creativity of the work community,’ explains Joutsenvirta. ‘Unlike artificial intelligence, we can pay attention to more than facts. We have many kinds of intelligence, and the world is opening to exploring things that machines cannot do.’

‘I agree,’ responds Romanoff. ‘All creative work would benefit from reducing stress levels and making more room for emotions. Now that artificial intelligence is already being used to assist us in tedious tasks, I hope we’ll have more time and courage to focus on everyone’s wellbeing and resilience as a community resource.’

Read more about the embodied practices used in the Capacity Building of Creative Radicals project: aalto.fi/en/embodied-practices

Check out the Oasis of Radical Wellbeing project website for research-based information on how we can take care of ourselves and each other: aalto.fi/fi/oasis-of-radical-wellbeing

34 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33 DIALOGUE Invisible

‘If you don’t react to the warning signs from the subconscious, you often act against your own values.’

A camera that sees the invisible

Director

There are invisible people living among us, who can only be seen through the camera, and it’s Jesse Jalonen’s film Nobody Meets Your Eyes that tells their story. Shot on an old Nokia mobile phone, the film is Jalonen’s final project in his film directing major at Aalto University.

The story follows a single father, Tuomas, who gets into trouble with child protective services because of his invisibility, and Ninni, as she meets her internet lover for the first time in real life, but even then there is a camera between them.

The film received international attention after its world premiere as the only Finnish film at the 2022 Rotterdam Film Festival, which described it as ‘a sensitive story about fundamental loneliness and the comfort of connection.’ A combination of documentary and fiction, it was also awarded Best Film at the Filmadrid Festival in Madrid in 2022. It was distributed in Finnish cinemas last spring.

The invisible loners

The old Nokia C5 phone used to shoot came about somewhat by chance. Jalonen had saved his old phone, which he used to take individual shots here and there.

‘What was important to me was that the camera exposed the world as something marvellous and enchanting. The act of shooting reinvigorated my relationship with the world. I became aware of things, places and people that I had previously not noticed,’ says Jalonen.

The jaggedness of the mobile phone picture fits the subject – it was also almost necessary for the subject.

‘Usually in film, the viewer takes what’s on the screen as “straight” reality. Here, the grittiness of the cell phone image underlines the fact that there is a camera between the viewer and the characters in the film. It justifies why we see invisible people. If the images were of better quality, that frame would be missing.’

One recurring sight that the director encountered were people who seemed lonely even in the most public of spaces, despite being surrounded by other people.

‘A kid at the airport, people waiting for the bus, a runaway bride sobbing on the sidewalk. I realised that these were the real “people living only in images”, now rendered visible, for the first time, by my camera. These were the ones I should write about. And so I did,’ says the director.

The fact that we see each other more and more in, or as, images does not so much create our separateness as it exposes it. Jalonen sees our current situation mainly as a symptom of, or a metaphor for, our fundamental loneliness – not the cause of it.

He hopes that the film would not just expose our loneliness but also offer us consolation.

WOW!

Text Krista Kinnunen

Photos Jesse Jalonen

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33 \ 35

Jesse Jalonen’s film makes use of a classic phone.

The concrete alternatives that could change the world

ON SCIENCE Invisible 36 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 33

Text Amanda Ruggeri

Photos Maarit Mäkelä, Johannes Kaarakainen

One day in early 2023, doctoral researcher Ville Repo was in his laboratory testing clay from the region of Kainuu, eastern Finland. His goal: to see if, after being heated to 750° C and appropriately processed, it could become as strong as concrete.

Half of the Finnish clay was kaolinite – a common, soft mineral, often white, that originates from the chemical weathering of certain minerals over millions of years. Kaolin has been researched, and occasionally used, as a cement alternative around the world. Even so, the results of the strength test shocked him. Once treated, the Finnish clay reached a strength of up to 74 megapascals. Regular concrete measures around 30 to 50.

The potential for a kaolinite mix to outperform concrete was exciting. The concrete industry is the second largest source of carbon emissions, accounting for 8% of the world’s total – a ‘horrendous amount of CO2’, says Repo, who studies mineral-based materials and mechanics at Aalto University. Most of the greenhouse gases are emitted when the limestone is processed and heated to around 1,450° C, and there are also emissions from transporting limestone and other materials over long distances for production.

Meanwhile, the world’s desire for concrete – or a material like it – is only growing. In 2020, about four billion tons of cement were used globally. That’s more than double the amount used just twenty years ago.

As a result, researchers like Repo are trying to find cement alternatives that can be produced using less energy and, ideally, local materials. Rocks rich in kaolinite, known as kaolin, are common in most of the world, making kaolinite an ideal candidate. So for most researchers, those test results would have been a big win. But not for Repo.

That’s partly because kaolin isn’t widely deposited in Finland, so Repo wants to find something more local. But there’s more to it than that.

‘We could have taken the easy way out and done cool stuff with just the kaolin,’ he says.

‘But we’re trying to find something new, go a bit further.’

A radical approach

Founded in 2022, the Radical Ceramic Research Group brings together researchers from very different disciplines – from arts to materials science, design to civil engineering – to share ideas, techniques, and even soil and clay samples.

Their goal? To investigate how natural substances like clays could be used as geopolymers and alkaliactivated materials. Geopolymers are polymers made of minerals that could be used in place of limestone-based cements. They offer a greener alternative for everything from construction concrete to studio ceramics, both because they require less heat to produce and they can be made from local materials, meaning less transportation.

Maarit Mäkelä, a professor of design in the group, is excited about the progress they’ve made so far. ‘We've already been able to make small-scale geopolymers that are the perfect, perfect shape – mainly cubes,’ she says.

In June, her team presented the research group’s first official paper, highlighting their initial finding that geopolymers can be a lower-energy alternative to ceramics, which often need to be fired at temperatures of up to 1,300° C. The geopolymer mixes that her team used – which included mixes with raw Finnish clay, volcanic rock and even porcelain waste – didn't need to be fired at all. Instead, they were cured at just 80° C.

But geopolymers don’t just take less energy to make, the researchers say. They can also be made by re-using waste material which would otherwise go into landfills.

In Finland, clays tend to be too soft to directly build on, says Repo. ‘So when we are building, we usually need to deal with the clays,’ he says. ‘We have vast amounts of waste clays that are just dug out from the construction site and dumped in landfills. That also consumes quite a lot of energy because of how far the soils are transported.’ For example, in Helsinki alone, about 800,000 cubic meters of uncontaminated waste soils are transported an average 50km or more to landfills each year.

The researchers in the Radical Ceramic Research Group envision a different kind of future, one in which the clay dug out at a building site is mixed with cast-off shards of ceramics from a local factory, treated on-site, and used for construction right there.

Surprisingly simple

According to Luis Huaman, a doctoral researcher in civil engineering, that vision isn’t as far-fetched as it might seem. Like others in the research group,

Concrete is the world’s second highestproducing source of emissions – and our appetite for it is only growing. Aalto University’s Radical Ceramic Research Group is pioneering some potentially transformative alternatives.

he was pulled into the world of geopolymers from a different background: in his case, geology.

In his native Peru, Huaman worked with Professor Joseph Davidovits, the world-leading pioneer of modern geopolymers. Huaman was especially interested because of the many ways the technique could be used in Peru. Mining is common in the country, and separating out the ore typically results in by-products – usually toxic – that are stored in earth-filled dams called tailings dams. Tailings dams are not only environmentally disruptive but can also be unsafe, with failures relatively common and sometimes deadly.

With the right materials, the process to make a geopolymer, Huaman says, is actually ‘very simple’. First, sodium, potassium silicate, or sodium hydroxide are mixed with a material like kaolin or fly ash. Then fillers – such as sand, or the leftover silicates from mine tailings – are added to the mixture. The material is left to dry at room temperature, or cured in an oven. After a day, the mix is hard enough to be used.