You once told me you felt Basquiat was a superhero. What did you mean by that? His superpower was a sensitivity, a sensitiv ity to all things that were beautiful, well done. Whether it was the way someone danced or the way someone dressed, or spoke, or other forms of art that he would experience. Of course, everyone has taste and art is subjec tive, and taste in anything is subjective, but part of his whole thing was, is that cool? Is that hip? Is that dope? If he wasn’t feeling it, he would shut down. Once, we were work ing in Nick Taylor’s apartment up in the Upper West Side and I was behind the drums and Jean was on the… sitting on the floor, he had a guitar with all the strings completely loose, just loose, beyond untunable, and he was running a metal file along the strings. That’s how he was playing the guitar, which is not how you play the guitar. But that was how we approached, all of us approached, our instru ments. So, I’m sitting at the drums and I’m banging away and, clearly, I had rubbed Jean the wrong way, musically, at that moment, with my instrument. I’ll never forget him just looking up at me and kind of wincing in pain.

Like what was that? He didn’t say it, but he just gave me that look. Instantly, I changed direction and was able to not only read from his expression that he didn’t like what I was doing, but I was also able to read from his expression where to head. That’s an amaz ing amount of information just to get from one look. He had that skill. He had that ability to communicate ideas like that with somebody, when first meeting them. A lot of the people I’ve met were superstars in the way that they were special, they were geniuses. They made the world pay attention to them in special ways. I’ve never met anyone like Basquiat.

Tell me about the first time you met, it was ’79 right?

It was interesting. April 29, 1979, the Canal Zone Party. I was in a band called the Tubes in the mid-seventies. So, I knew this English artist named Stan Peskett, who was, like, ten years older than me, or more, and came from the Royal College of Art. Anyway, I met him in California, when I came through with the Tubes, so when I came to New York, he was one of the few people that I knew.

MICHAEL HOLMAN

Interview: Mary-Dailey Desmarais

032

We come up with this idea to throw a party called the Canal Zone Party, as a way to introduce the Fabulous 5, Fab 5 Freddy’s graffiti collective, to the downtown scene. What happened was really special. This was the first time that you had the downtown art scene rubbing shoulders with what would become hip-hop culture. That’s crucial, because that relationship is what put hip-hop on the map.

So, we’re setting up the party, it’s summer time, so it’s still light out. It’s like seven o’clock, or something, the party’s gonna start at nine or so. This young kid shows up, handsome, charming, super confident. Super sure of himself.

So, we quickly give him a can of red spray-paint, we put up a big nine-foot by twelve-foot piece of photo paper and he starts to write: “WHICH OF THE FOLLOWING IS OMNIPRZNT? (A) LEE

HARVEY OSWALD (B) THE COCA-COLA LOGO (C) GENERAL MELONRY” he’s the guy who ordered the bombing of Hiroshima and “(D) SAMO©,” and we’re like, “Oh, shit, you’re SAMO©?” You know, because everyone knew about SAMO©. But had never seen him… Who it was. We found out later about Al Diaz’s role. But, at that stage we’re like, “You’re SAMO, that’s wild.” My job at the party was to interview people on camera. So, I would interview people and put a microphone in their face, asking them a question with a microphone in their face, and then before they could answer, pull it back and ask another question. It was like this totally one-sided interview.

I was being a dick. So, I go to interview Jean, and I’m doing the same stupid thing. When Jean realized I wasn’t gonna let him answer, all of a sudden, all judgement, all emotion, all expression just drained from his face, like an hourglass, like sand from an hourglass. And it just went like a Medusa. Like his face turned to stone. To stone. I found myself kind of like look ing at this stone face, and you know what I saw?

I saw myself. It was the reverse of Medusa. He just basically said “I’m a mirror. Now what do you see?” And I’m like, “I see myself acting the fool.” I started stammering and stuttering, and the interview ended. Mercifully. Five minutes I see him standing around the party kind of by himself, not talking to anybody. I took that opportunity to go up to talk to him say, “Hey man, you know, sorry about that, just goofing around.” You know what he said to me? He said, “That’s alright man. You want to

start a band?” And I went, “Yeah!” And we started Gray that moment.

How would you describe Basquiat’s role in the band?

I mean, he was clearly the leader of the band in spite of the fact that we approached our music democratically. I mean, we all did our own thing, and while we were playing it would work out. But if there ever needed to be a last word in anything, it was Jean’s.

The band went through several names like Test Pattern, and Bad Fools before settling on Gray. How did you come up with the name?

I remember after one of the rehearsals we were walking on the northern border of Washington Square Park and he just said, “I got the name of the band,” and we were like, “Really? What?” We’d been through so many names, and we knew they weren’t right. He said, “Gray,” and we all went, “Yeaaah, Gray.” It’s not black, nor is not white. It’s the colour of machines. It’s industrial sounding. I think the most we ever questioned was Gray with an “E” or an “A.” He’s like, “With an A,” and then we knew it was for Gray’s Anatomy. We didn’t have to ask him.

When you started out, did you have a very clear idea of the kind of band you wanted to be?

We knew we were going to start a group in which no one in the band can be a musi cian, everyone must approach their sound, their music, their instruments, from a point of view of innocence in terms of understand ing music, ignorance, and that cuts both ways. Ignorance in the exact definition, like not knowing the information, but also igno rance as a jazz term, which means so cool, like that is ignorant. Basically, just the same way bad was a compliment during James Brown’s time, “ignorant” was actually a com pliment during the jazz days, you know, during the loft-jazz days. It was this idea, and it’s part and parcel to, I think, Miles Davis’ philoso phy and approach to jazz, who was obviously an accomplished musician, that there were no mistakes. That when you did that loft jazz and that free jazz, or new jazz, or cool jazz, or even bebop. When someone made a mis take, you didn’t stop the production and

MichaelHolman

Seeing Loud:Basquiat and Music Interview

Prelude

033

The Urban Soundscape: A Playlist in Remix

Carlo McCormick

The artist in the studio is widely understood to be engaged in a solitary practice, but it is rarely a silent one. For all that followers and fans, critics, curators and collectors of art may fathom about the work and its process, overlooking the audio context, as if what the artist might be listening to is as incidental and irrelevant as what they had for lunch, elides a signif icant part of the picture. To hear art, we need to look at music, for each is together the synae sthesia of experience. No doubt the terms of engagement have shifted — streaming services do not engender the same curatorial familiarity as one’s own record collection, where the assembling of physical artifacts is in many ways a highly personal construction of iden tity, and the preference of many contemporary artists for audiobooks or talk radio eschews the influence of external compositional and emotive influences in favour of a background of disembodied narrative. But for a generation of artists living and working in New York during the late 1970s and early 1980s, music was a fundamental and inextricable component of the visual culture. The story of that time had lyrics; the Zeitgeist had a beat.

ALL THAT JAZZ…

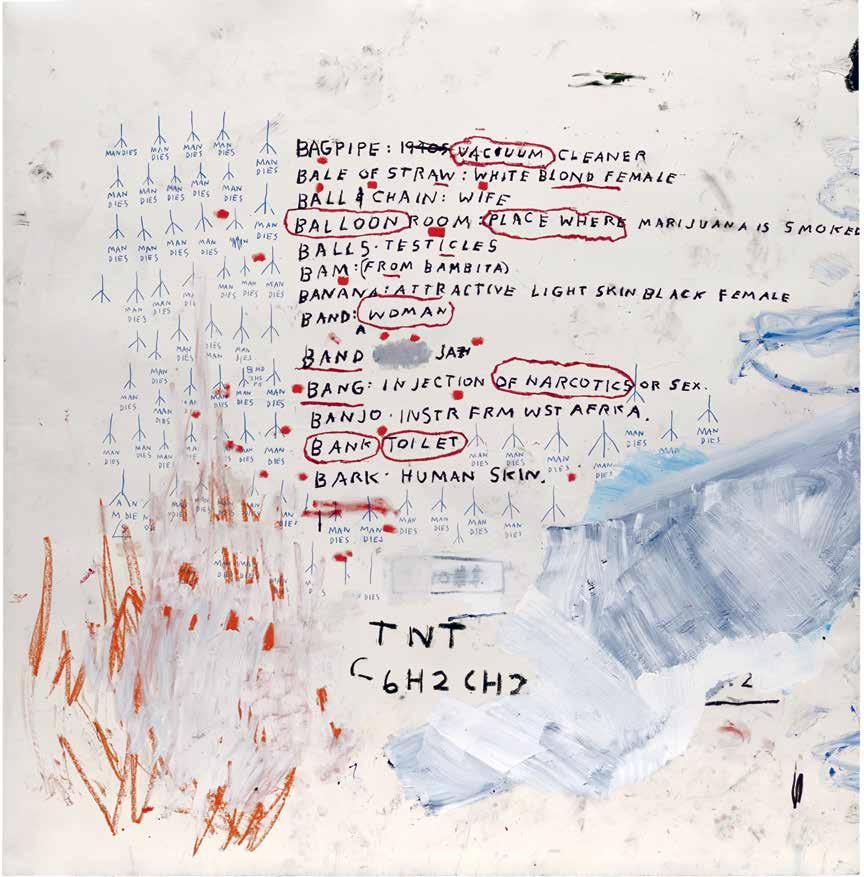

When one considers the referencing of music in Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art, jazz is inevitably what comes to mind immediately, in particular the radical arc of bebop, which gained dominance in the 1940s and evolved throughout the 1950s (via a generation influenced by rhythm and blues, or rock) into elements of cool and hard bop. Direct references to that era abound in Basquiat’s art and include citations and homages to artists like Ornette Coleman, Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach, Miles Davis and, most abun dantly, Charlie “Bird” Parker, who first emerges as a significant figure in the artist’s body of work as early as 1982, with CPRKR [085], which, by directly alluding to New York’s Stanhope Hotel (where Parker died), acts as a memorial, redolent with the tragedy of his long struggle with, and eventual succumbing to, the per sonal demons of addiction.

Stylistically, if we may venture into a direct comparison of fine art with popular music, there is a relative similarity between the pictorial imagination of Basquiat’s paintings and the compositional strat egies of bebop. Let us say that this is something we do not always see, so much as hear, in Basquiat, but bebop’s most salient qualities of vertiginous, rapid up-tempo dynamics, freestyle improvisation and complex harmonically structured decomposition of well-known standards is somehow echoed in the appropriative, fractured and frenetic style and sub stance of Basquiat’s work. The obviousness of this connection, which has attracted so much of the best ongoing scholarship on the artist, makes, however, something of a false equivalency, obviating a far broader and richer tapestry of musical inspirations he registered along the way and belying his personal rela tions with numerous artists and musicians of his time.

Musically, much was in the air during the early 1980s downtown scene, but contemporary jazz like many historical genres that suddenly seemed patently passé and lifeless in the tumult of the new — was not

really what people were listening to. As we begin to consider the rapid and often mercurial developments on New York’s music scene, following in the wake of punk and disco — to think of it less as a definitive discography than a seamless mix of often contradictory, but discretely overlapping textures and attitudes we might come to understand Basquiat’s bebop as a kind of signifying, in the sense of a boastful dissing contest. Such a position denies neither his love of this music nor affinity with its historical imperative; it simply seeks to place it as a cultural centre of intellectual and (dare we say) spiritual signification around whose gravitational meaning Basquiat would discover and define his identity as a black man in a remarkably white art world.

In the context of the postmodernist tendencies endemic to that time, there would be nothing fake or put-on about such a retro impersonation. To this manner of appropriation in which the past can be a highly personal and contemporary language of the self, we need look no further than the jazz-inflected band of the downtown Manhattan no wave movement, the Lounge Lizards, whose leader, John Lurie, was a close friend of Basquiat. At the time of the release of their first, eponymous album in 1981, featuring a now legendary line-up including Lurie on saxophone [009], his brother, the pianist and composer Evan Lurie [010], and Arto Lindsay [011], the no wave guitar assassin all of whom were in Basquiat’s friend/family circle the band was widely misconstrued as a piss-take on jazz, a misconception in part based on the iconoclastic tenor of no wave, but also, no doubt, attributable to the fact that a lounge lizard was a term for neither the aficionados nor virtuosos of jazz, but rather for the well-dressed men who would frequent nightclubs with the primary purpose of seducing wealthy women.

(BAS.0946)

(BAS.1033, BAS.0264) (BAS.0704)

The Lounge Lizards were in fact a jazz band, as their subsequent recordings would more clearly articulate or even their choice of two Thelonious Monk covers on their first album, as well as their obvious affinity to the musical explorations of free jazz saxophonist and downtown stalwart Ornette Coleman and astral Afrofuturist bandleader Sun Ra, who by 1979 would lead the house band at the experimental downtown avant-garde venue Squat Theatre, where Basquiat would perform with his friend Rammellzee [013, 167]. However, the Lounge Lizards [163] were also a down town, tongue-in-cheek intimation of the artifact that delivered its soul truth with deconstructive degrees of irony, mediation, pastiche and critical distance; they were like tricksters in caricature expressing our collective urban ennui in noir soundtracks of enigmatically sexy dissonance and dissolution. Like jazz itself, which by the 1980s was more often a form of self-indulgent easy listening that we might as well call jizz, it is recon stituted downtown as signifier and surface, a container for African American experience and expression as it was rewritten within the white, Eurocentric language of composition, an integration and disintegration of the most profound order.

CONTORT YOURSELF

As the period of rampant experimentation that was the great sonic freak-out of the 1960s ossified into the middle-of-the-road (MOR) virtuosities of the mid-1970s,

CarloMcCormick

New

YorkBeats

The

UrbanSoundscape

Seeing Loud:

Basquiat

and Music

041

(BAS.0007)

050

035

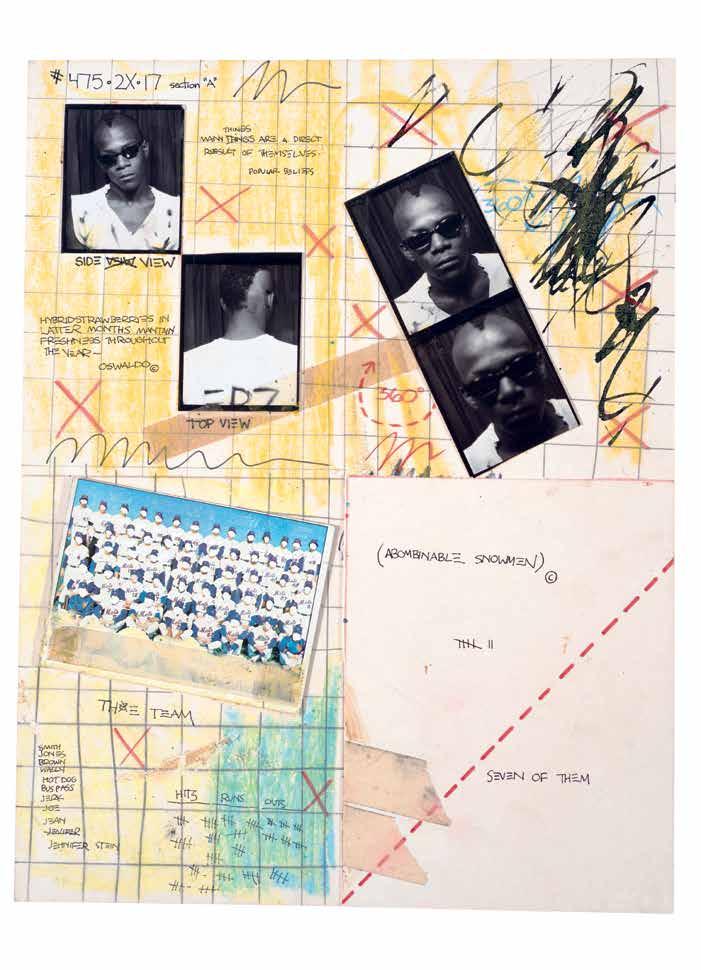

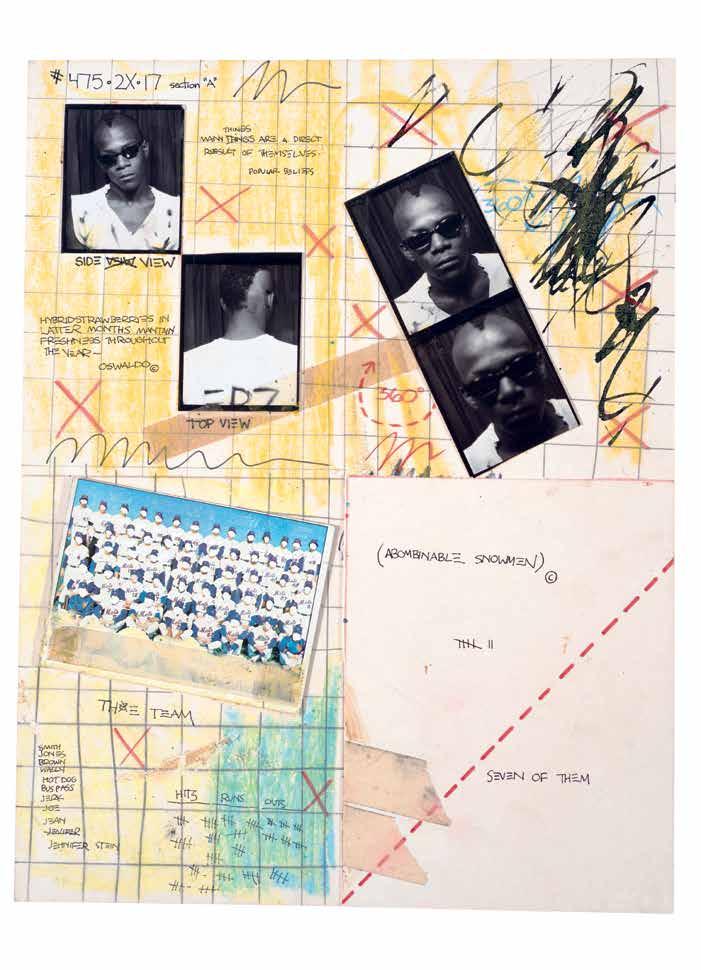

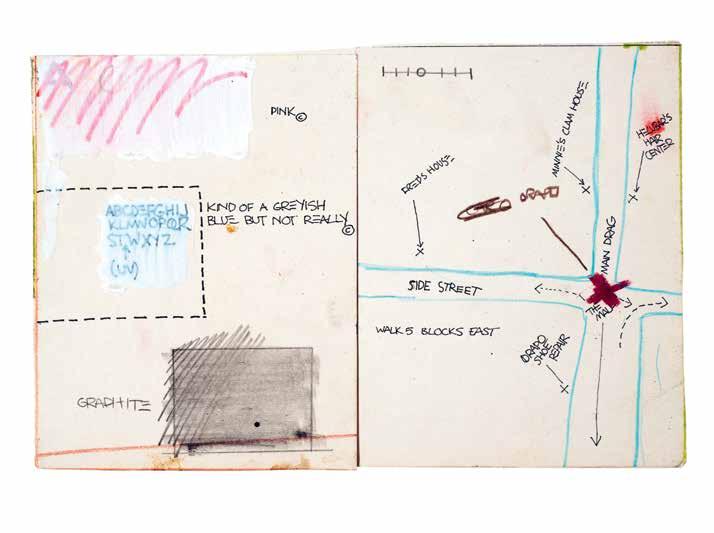

Collaboration between Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jennifer Stein, (Anti-) Product Baseball Card, 1979, mixed media on cardboard, 21.6 × 13.9 cm

036

Collaboration between Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jennifer Stein, (Anti-) Product Baseball Card, 1979, mixed media on cardboard, 21.6 × 13.9 cm

051

The Sound of Basquiat

CHARLIE PARKER A TRUE LEADER OF A NEW BREED OF LOOSENED DISILLUSIONED REBELS TOOK THIS EXISTING FORM STRIPPED IT DOWN STOLE THE MELODIES FROM THREE DIFFERENT SONGS SPLICE THEM AND PLAY THEM SIDEWAYS THRICE THE ORIGINAL TEMPO.

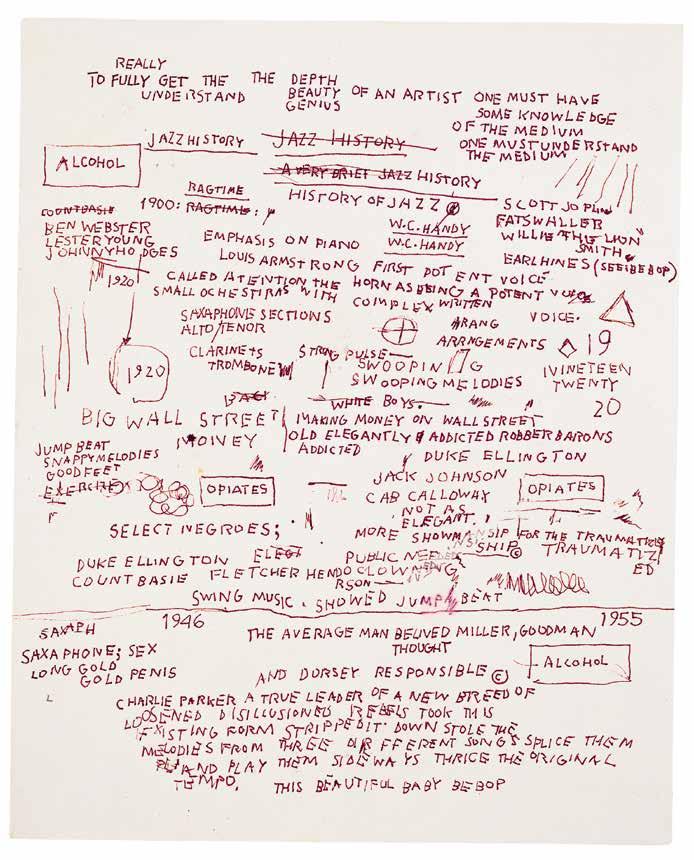

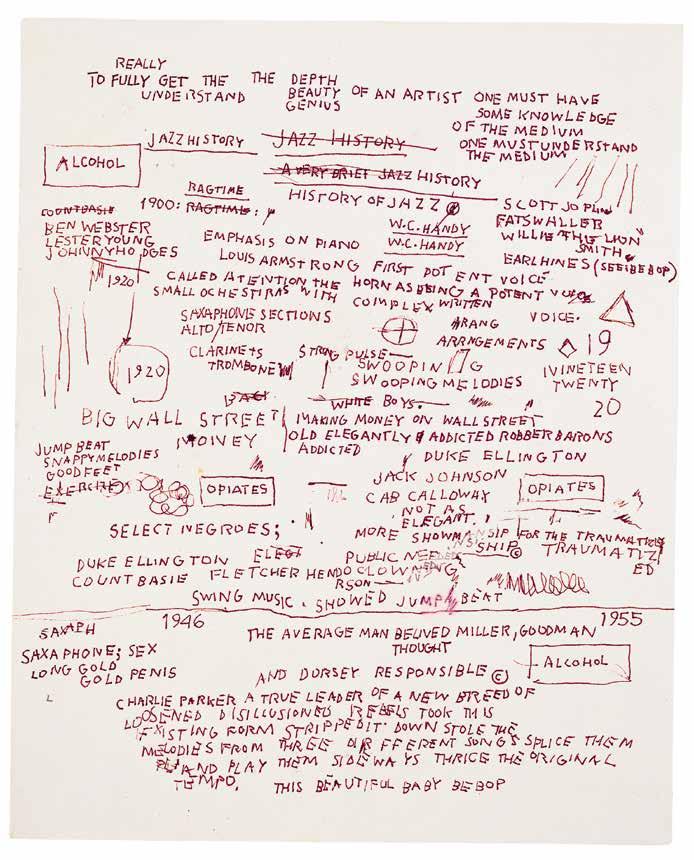

THIS BEAUTIFUL BABY BEBOP [See 092] (BAS.0399)

Dieter Buchhart

When Lisa Licitra Ponti asked Jean-Michel Basquiat about his favourite music, the artist’s concise response was “Miles Davis.”1 “Miles Davis” was also the condi tion for his taking part in André Heller’s theme park Luna Luna in 1986.2 After Davis had agreed to the use of his music, Basquiat designed a Ferris wheel [065], whose slow movement was to be accompanied by the sounds of the album Tutu (1986). Music was always the focal point of Basquiat’s life and his art. Glenn O’Brien remarked that Basquiat “knew about Miles Davis and John Coltrane and Charlie Parker the same way he knew about Picasso and Duchamp and Pollock.”3 Heller also remembers Basquiat’s wide-ranging inter est in music: “We spoke a great deal about music…. for example, something he didn’t know about,… the Ballets Russes. Those collaborations between Satie, Cocteau, and Picasso — so difficult. That interested him in an extraordinary way. He then designed a curtain for a show entitled Body and Soul”4 [066].

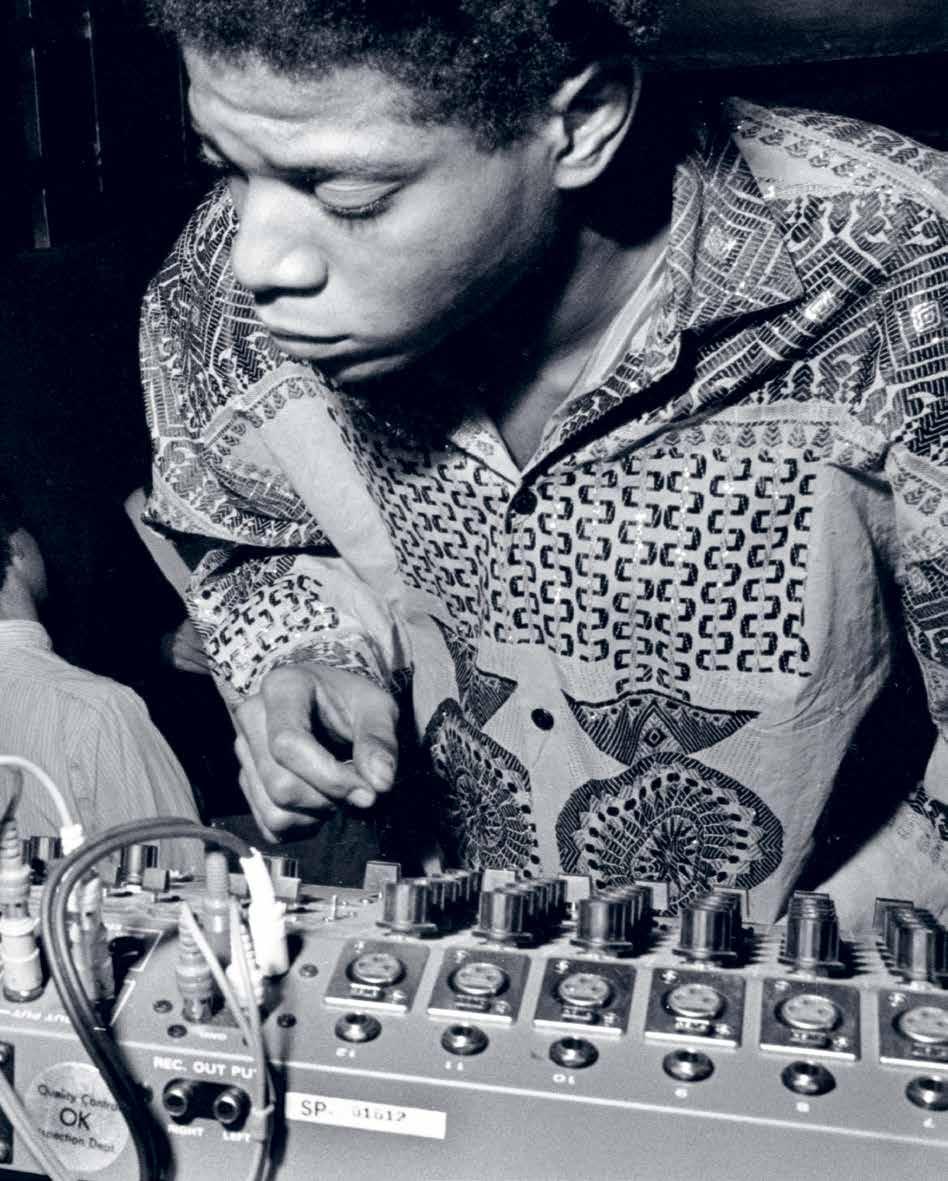

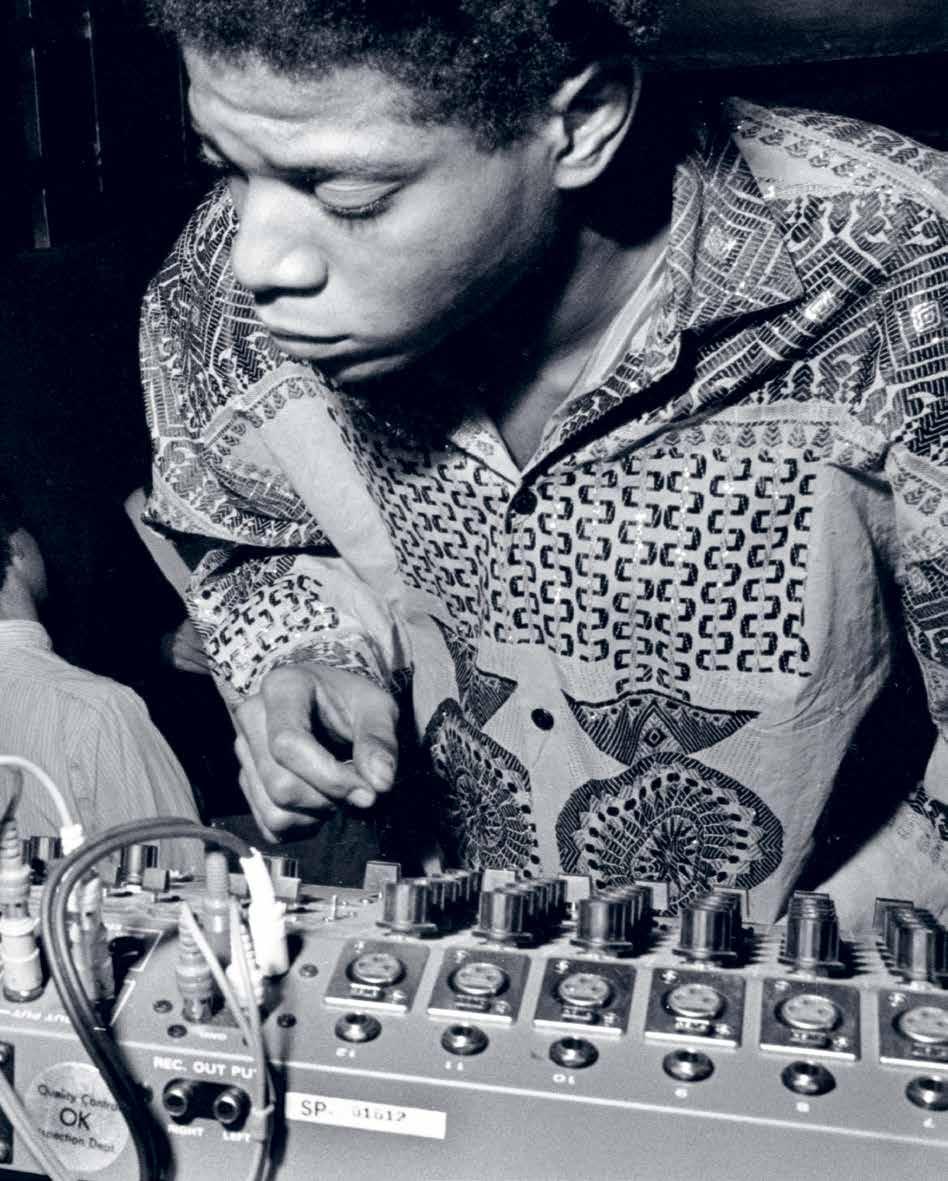

As early as his childhood, his father, Gerard, had familiarized him with several musical styles, espe cially jazz.5 Later, Basquiat repeatedly treated various artistic disciplines in his oeuvre: he was both a drafts man and a painter as well as a performer, actor, poet, musician, DJ and active participant in the framework of collective artistic work. This was fundamentally rooted in the general openness to all media that pre vailed in New York’s downtown art world in the late 1970s. Of course, we should keep in mind that Andy Warhol had been working with various techniques and media already since the 1960s, constantly expanding his repertoire and overstepping and overcoming traditional boundaries separating individual disciplines and cultural fields: from painting, printmaking, drawing, photography and sculpture to film, fashion, television, performance, theatre, music, literature and digital art. With such an open framework, switching between various disciplines was a virtually self-evident undertaking, thus anticipating the interdisciplinary works of many artistic approaches of the 1990s. The extent to which the intersection of music and art inspired Basquiat is reflected in the analogy he draws between his own works and the sound of Davis’ trumpet: “I don’t know how to describe my work, ’cause it’s not always the same thing…. It’s like asking somebody, asking Miles, ‘How does your horn sound?’ I don’t think he could really tell you why he played you know, why he plays this at this point in the music. You know you’re just, you’re sort of on automatic.”6 Ultimately, everything in Basquiat’s life and work was associated with music; it is structurally linked to his drawings and paintings. For example, Annina Nosei recalls that when Basquiat began working at the studio in the basement of her gallery in 1981, he was listening to music “all the time. It drove me crazy! He knew a lot about music, from his family, especially his father. A lot of jazz, as you can see in the paintings. Not only with references to the major artists of jazz, but also in the structure of the paintings…. And he must have liked Maurice Ravel, over and over the same music…. There was a lot of music there. He painted with the music.”7

From the very beginning of his artistic practice, Basquiat let the ordinary flow into his work, similarly to John Cage.8 His “source material,” everything that surrounded him, what he heard, saw and perceived,9

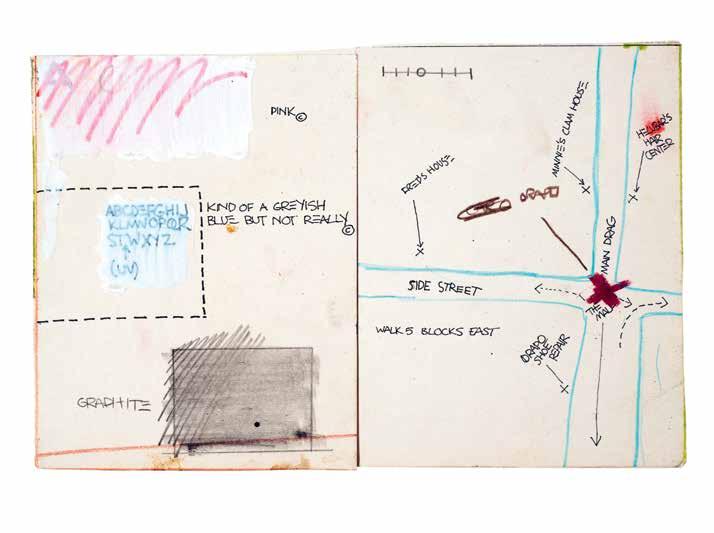

formed the foundation from which he created his spaces of knowledge.10 The noise music that he pro duced with Nicholas Taylor and Michael Holman in the band Gray formed part of this artistic world: “It was a noise band. I played a guitar with a file, and a synthesizer. I was inspired by John Cage at the time music that isn’t really music. We were trying to be incom plete, abrasive, oddly beautiful.”11 With this mention of Cage, Basquiat was referring to the former’s con certs and performance practices from the 1940s and 1950s, for example, the coincidental sounds coming from the audience and musicians, as well as the background noise outside the concert hall became the piece of music itself in Cage’s composition 4' 33" (1952). Accordingly, Gray’s primary rule was, as explained by Michael Holman: “You couldn’t be a musician.”12 This is entirely in keeping with Cage, who spoke about “hearing each sound just as it is, not as a phenomenon more or less approximating a preconception.”13 Basquiat’s music production was clearly “not unlike his art,”14 as Cathleen McGuigan described, especially in terms of the integration of the everyday, that which directly sur rounded him, the things he came upon by chance, that literally lay before him. The artist painted and drew on the walls around him, on discarded windows and doors, mirrors, cigar boxes, foam mattresses, wooden planks, old boards,15 and other commonplace things. “By way of his ‘hand,’ they were transformed and gain a new signif icance, they become art,”16 as Demosthenes Davvetas remarked. Influenced by Cage’s methods of composi tion and call to uphold chance and the unpredictable in art, Basquiat literally reworked his immediate surroundings far beyond a mere “activity.”17

Basquiat also came across one of his “trade mark phrases,”18 “Boom for Real,” by chance.19 This phrase was more a spoken or performative slogan than a drawn one.20 “Boom for real” was, above all, an expression, an artistic strategy and a general attitude, as was also underscored by Diego Cortez: “He [Basquiat] had the expression ‘Boom for Real’ explo sion and then you end up with fragments rather than the cubist and post-cubist way of building sections, hatching things together, a quilt work. Jean-Michel’s work was not about a quilt, it was about a galaxy of reality that has been again exploded. So everything is equal.”21 All disciplines, all influences, all knowl edge seem to be materials of equal value used as the basis for Basquiat’s artistic practice. According to Nicholas Taylor, Basquiat took the phrase from a television interview with a homeless person during a snowstorm: “One evening Michael Holman and I went up to Wayne’s loft where Wayne and Jean-Michel were taking vocal samples from the television news. Wayne pushed the record button while a homeless person was commenting on the icy conditions in New York City. The man said to the reporter: ‘Fell on my ass, boom, for real!’ Since the tape was at the beginning, Wayne could push ‘play’ and then ‘rewind’ quickly, and the audio was ‘ignorantly’ looped to sounds like: ‘Fell on my ass, boom, boom, boom, for real, fell on my ass, boom.’”22 This work with sound reflected Basquiat’s playful approach to words, sound and Sprechgesang [spoken singing], his interest in rhythm and repetition, his sampling and scratching. A “boom” applied to the “real,” inspiration and explosion.

DieterBuchhart

SeeingSound

The Sound of Basquiat

Seeing Loud:Basquiat and Music

099

(fig.006) (fig.007)

108070 Dog Bite / Ax to Grind, 1983, acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 152.5 × 305 cm

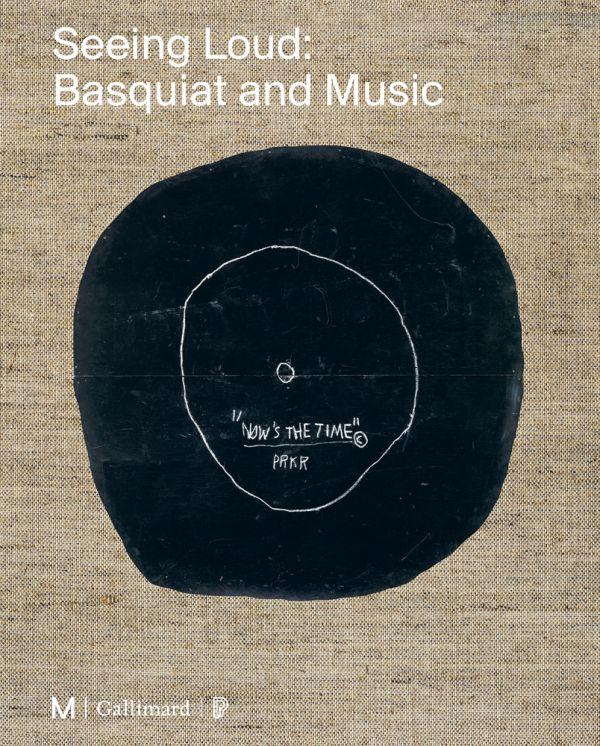

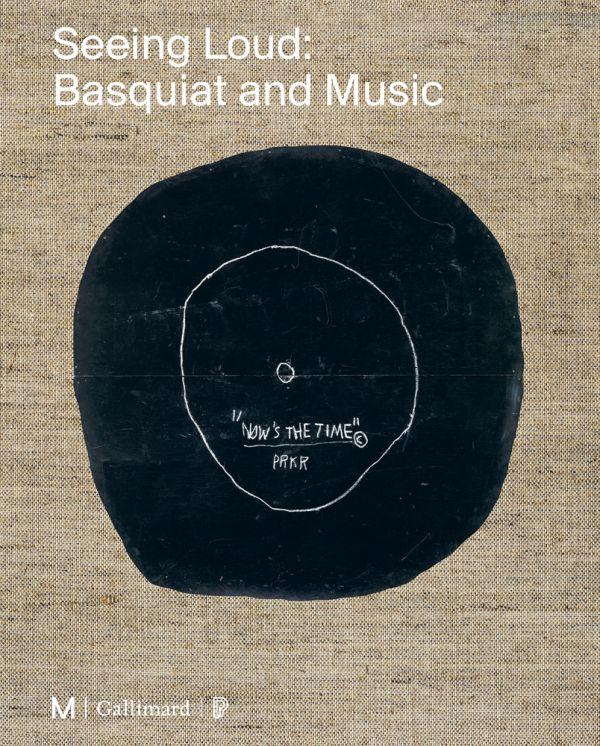

NOW’S THE TIME

Now’s the Time is one of the most powerful works JeanMichel Basquiat created using minimal means. It is also one of those whose seeming spareness overlies a density of interpretation showing his command of the use of sym bolic elements and the semiotic potency of his constructions.

Now’s the Time is also clearly one of the works con ceived as tributes to Charlie Parker. Like CPRKR [085] or With Strings (1983), it combines greatness with tragedy, and can be viewed as both monument and epitaph. “Now’s the Time” is a composition by Parker that he first recorded on November 26, 1945, in New York for the Savoy record label. Its title resounds like a decree for the modernity specific to bebop, of which Parker was a leading light, but also like an expression of the urgency, in the wake of World War II, of putting an end to seg regation. Dating from the same year as Now’s the Time, a drawing spattered with coffee stains depicts the same record, speaking to the place the piece held in Basquiat’s everyday. Executed from life, it faithfully reproduces the information contained on the label of the 78, from the logo to the title, matrix number and credits.

In contrast, Now’s the Time’s big plain black disc elevates Parker’s modernity by removing all commercial references, thus glorifying the object standing upright like a stela, its huge size effecting its derealization. The work’s unu sual proportions raise the record to the status of an object of worship, and sanctify its creator. The consonants “PRKR” are the clue through which Basquiat establishes the link with the musician, while reserving the key to his work for those able to decipher its meaning. From one figure to another, from “PRKR” to “MLK,” they also connect the jazz musician’s incan tation with another milestone in the history of the struggle for civil rights: “I Have a Dream,” the speech Martin Luther King gave in 1963, one of whose paragraphs was based on an anaphora of the phrase “Now is the time.”

For all that, Now’s the Time is more than an accolade for the genius of modern jazz. Its irregular shape, as well as its blackness, is a sign of the unease pervading most of the artist’s works. The concentric circles in white oil stick draw a dead star if not a black hole as much as a record. Through its emptiness and opacity, the work irradiates as a “black sun of melancholy,”1 a symbol of depression, loss and anxiety, a negative space, an abyss of antimatter in which the misunderstood genius foundered.

Like the tar and carbon that taint many of his works, the black material of the 78, in Basquiat’s eyes, was additionally a symbol not only of jazz artists’ alienation from the record industry (the sole guarantor of the dissemination of their music), but also, more broadly, of the dependence (his included) on the part of the whole of consumer society on oil a view inspired by his conversations with Duncan Smith,2 who, in 1980, wrote:

Without oil there would be no art. In art, there’s the word tar, an anagram. Tar is derived from oil. Painters, of course, use oil to make their art…. Artists/musicians need tar/oil, the same kind of oil that’s involved in the manufacture of records. Painters and musicians employ different art forms or they use different tar forms. Some of them can become a star after becom ing successful with their art made of tar, such tar allowing them to go far. The anagrams arts/ stars/tars are crucial to the symbols that deter mine an identification in our culture.3

In a move as minimal as spectacular — something both an eclipse and a revelation in the layering of symbolic circles one on top of another Basquiat (who named his own label the Tartown Record Co.), with Now’s the Time not only gave a multifaceted salute to one of his great predecessors, but also examined the place of the artist in American society and raised, indirectly, the same turbulent issue the rap group Public Enemy did in 1990, barely two years after his death: Fear of a Black Planet VB

1. Thisoxymoronisdrawnfromthe1854 poem “El Desdichado” by Gérard de Nerval, and discussed in the book by psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva in Soleil noir : dépression et mélancolie (Paris, Gallimard, 1989).

2. My thanks to Seth Tillett for having drawn my attention to Basquiat’s friendship and conversations with Duncan Smith.

3. Duncan Smith, “On the Current Symbolic Status of Oil,” in The Age of Oil, Duncan Smith (New York: Slate, 1987), p. 61.

Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music Jazz 150

1985

151 084 Now’s

the Time, 1985, acrylic and oil stick on plywood, Diam. 235 cm

092

Untitled (History of Jazz), 1983, ink on paper, 26.7 × 21.6 cm

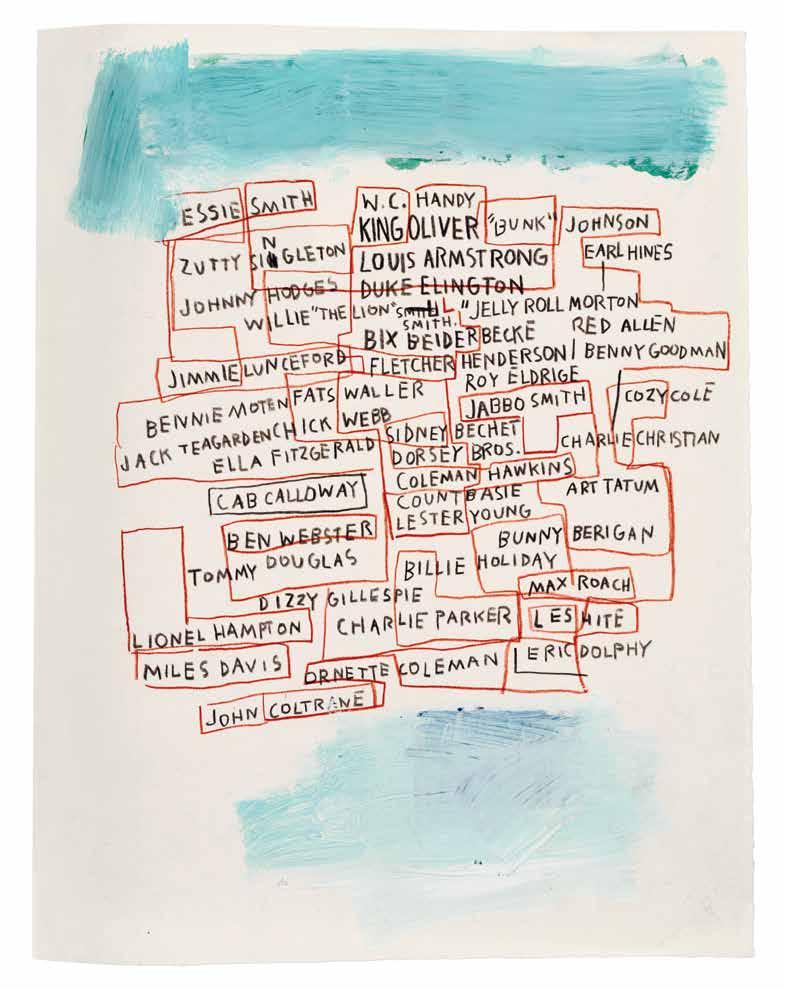

093

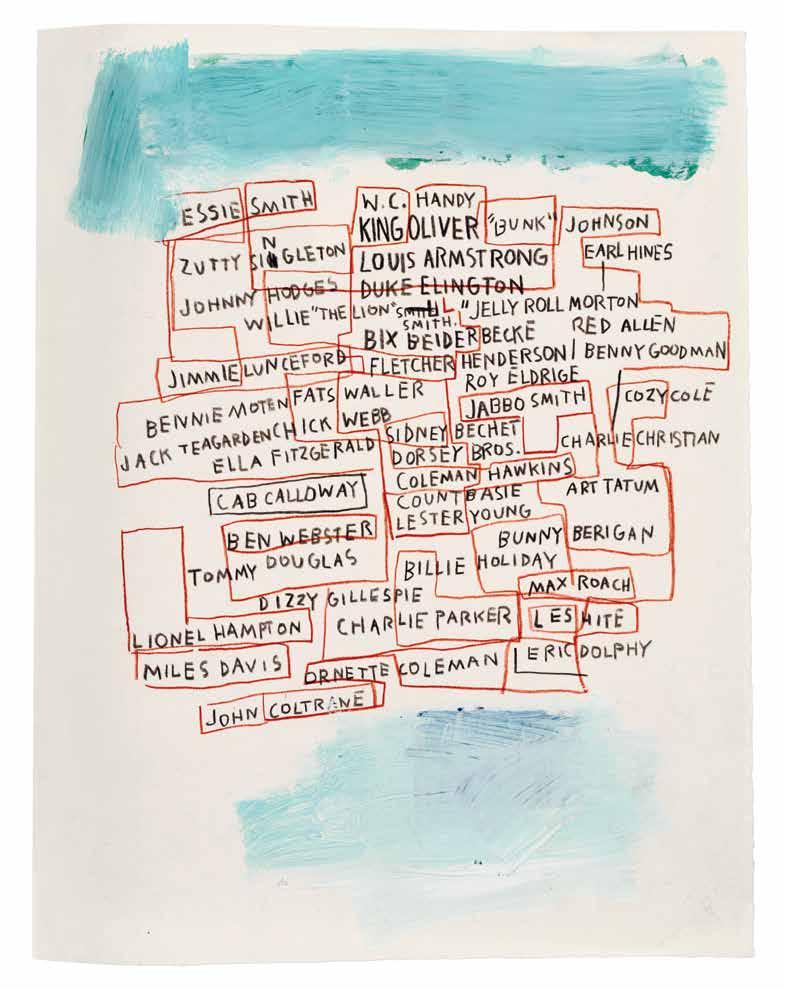

Untitled (Jazz Musicians, Guestbook of Chesa Lodia No. 1), 1986, mixed media on paper, 30 × 23.7 cm

164

165

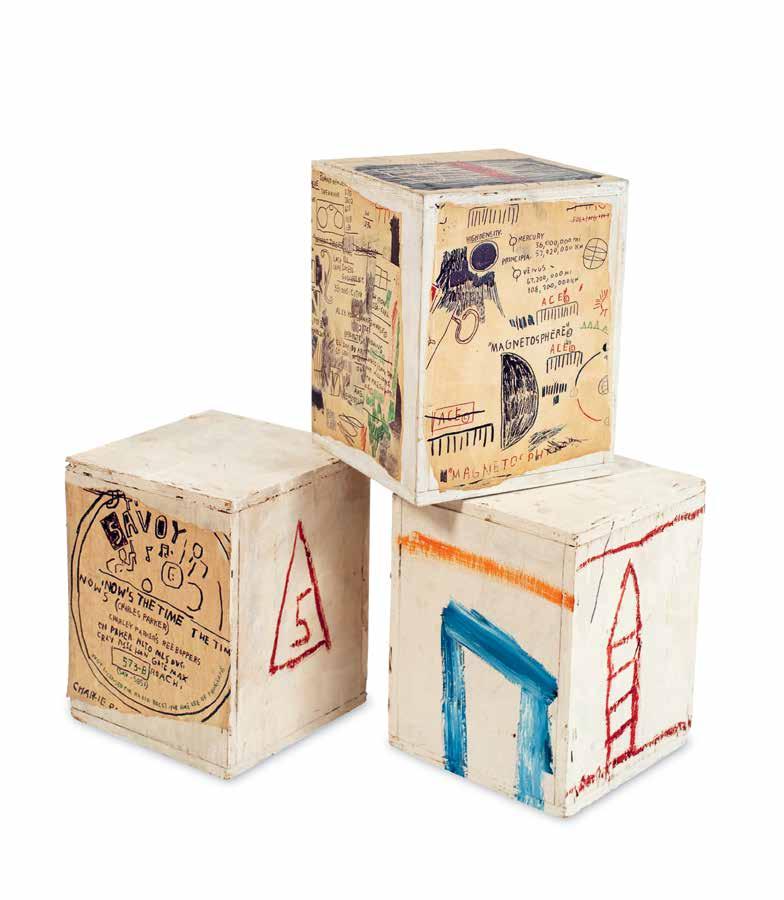

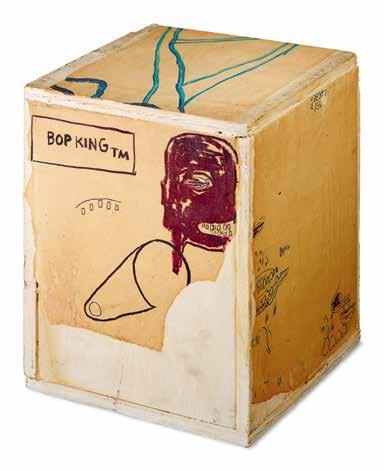

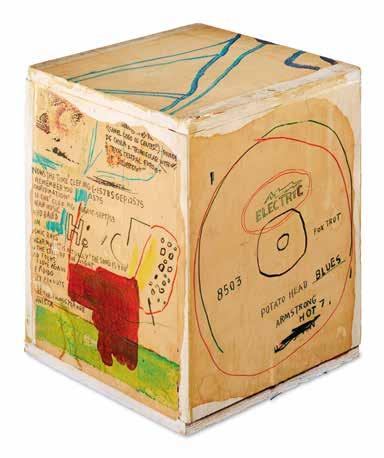

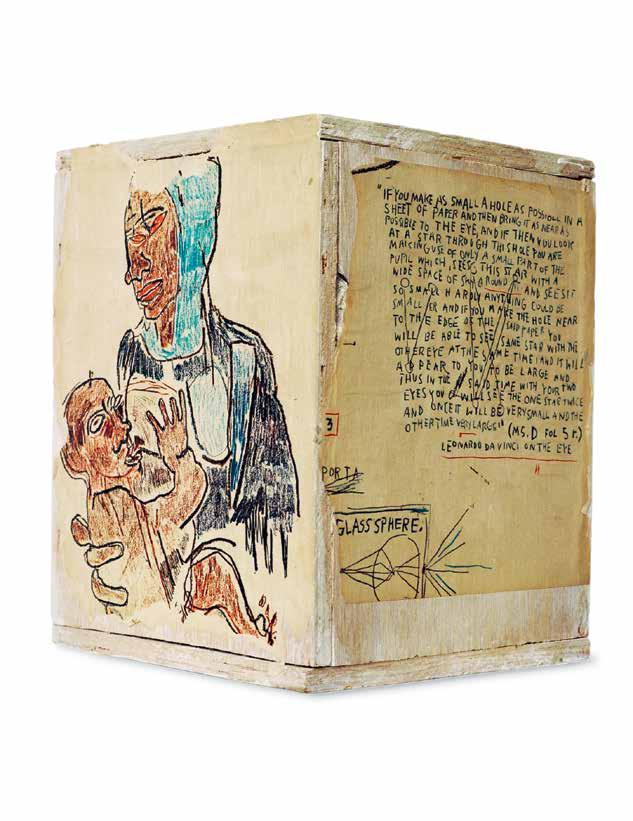

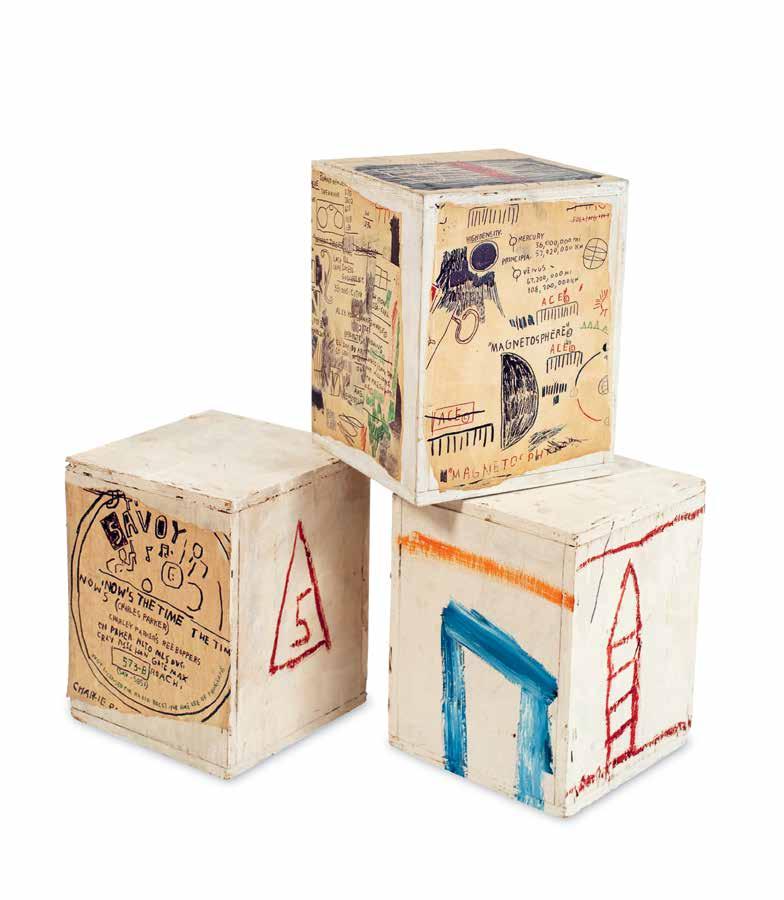

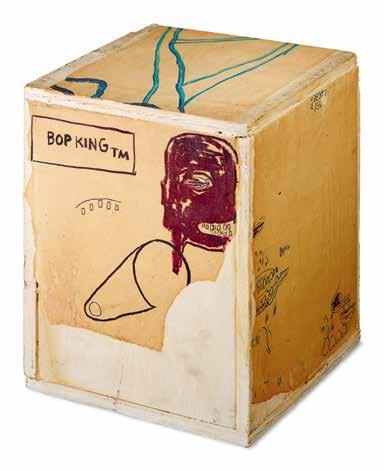

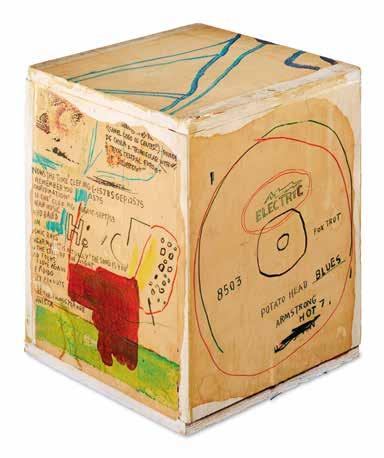

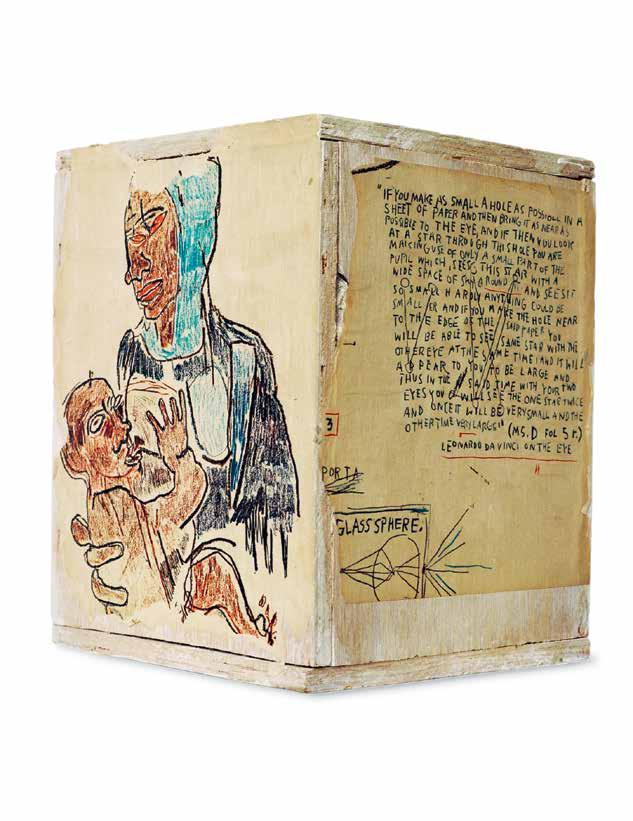

BASQUIAT’S BOXES

On May 8, 1985, along with some twenty other artists, JeanMichel Basquiat took part in a group exhibition on the theme of “Art” held at Area. Executed in situ, as numerous photos show, and set up in display window no. 2 in the corridor of the club, his contribution took the name Klaunstance, after a Charlie Parker composition recorded in 1947. Designed to form an ensemble, his installation juxtaposed different components that would later be dispersed. In this instance, Basquiat used various techniques and supports, in particular handmade wooden parallelepipeds, which stand alone in his body of object works. In the centre of Klaunstance, therefore, twenty-seven boxes were stacked in five columns and coupled with a shoeshine stand on which Basquiat had printed and then struck through the word “BRAIN©.”

These boxes were one of the trademarks of the artist who, from 1985 to 1986, produced several dozen of them, incorporating some in major works to which they lent an unexpected, three- dimensional depth. Painted in white once they were assembled, the boxes were covered with pieces of photocopied drawings that borrowed from various areas of Basquiat’s world of referents, a good part of them pointing to jazz. Besides the handwritten reproductions of 78 record labels (“Potato Head Blues” by Louis Armstrong, “Now’s the Time” by Charlie Parker and “Afternoon of a Basieite” by Lester Young), the photocopies displayed included discographical information, names of music artists (Sarah Vaughan, Lester Young, Dodo Marmarosa, and others), the words “BOP KING” and a bit of the index from the 1973 book Bird Lives! by Ross Russell. All such mentions were coupled with stars and planets, antennas and satellite dishes, lists of animals and raw materials, excerpts from a bestiary, names of Mississippi riverboats taken from Mark Twain, anatomi cal leitmotifs and a quote from the Bible. All that referential “noise” is displayed in a diffracted manner, from one side to the other, forming a huge puzzle of widespread knowledge the human mind never tires to want both to piece together and figure out, taking viewers on an infinite search for mean ing and compelling them to consider the plurality of the work, as per Basquiat’s combinatorial strategy.

The window at Area was the setting for one of the first public displays of the boxes, which were present in a number of pieces created at that time. Basquiat brought them back in a cryptic way in a short video for the MTV-produced series

Artbreak, in which Arto Lindsay, guitar in hand, bumps into them. One of the most remarkable of their uses is in the diptych formed by the assemblages Jazz and Black (1986), each of which incorporates four boxes fastened to its four corners. That Basquiat linked the form of the cube, referenc ing games, logic, construction and permutation, with works explicitly combining musical genius and blackness says a great deal about his understanding of the principles at the basis of jazz in general and bebop in particular, and about the transposition he made of that model into his own compositional processes. In its materials as in its construction, not only does Basquiat’s work avoid linearity and flatness, it also, in its delineation as in its perception, rejects static form: the box is its synecdoche. Just like jazz musicians in their improvisations constantly, chorus after chorus, rearrange the elements of their solos, Basquiat repositioned the tropes of his visual, symbolic and referential lexicon from one work to another using photocopying and assemblage. Placed under the mention of “brain” in Klaunstance, that continual reconfiguration refers to the brilliancy specific to black music and its capacity to develop endless works from lowly popular material. In associating it with the banality of a shoeshine box, Basquiat worked a scathing social commentary, reminding us that the anonymous minions shining the shoes of society’s dominant members and those who, ironically, exalted songs like “Shoe Shine Boy” (as Lester Young had done in 1936, in a solo so perfect that Charlie Parker learned it by heart) were sometimes the same — the sole difference being their stages in life. VB

Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music Jazz 196

1985–86

Untitled, 1986, acrylic and photocopy collage on wood box, 28 × 22 × 22 cm (each box)

197 113

114

Untitled (Wood Box), 1985, photocopy col lage on wood box, 27.4 × 21.5 × 21.5 cm

115 a–b

Two views of Untitled (Xerox Box), 1986, photocopy collage on wood box, 28 × 22 × 22 cm

199 115 a 115 b

116

Untitled (Box), 1985, acrylic and photocopy collage on wood box, 28 × 21.5 × 21.5 cm

117

Madonna, 1985, acrylic, oil stick and photo copy collage on wood, 106.5 × 58.5 × 7 cm

200

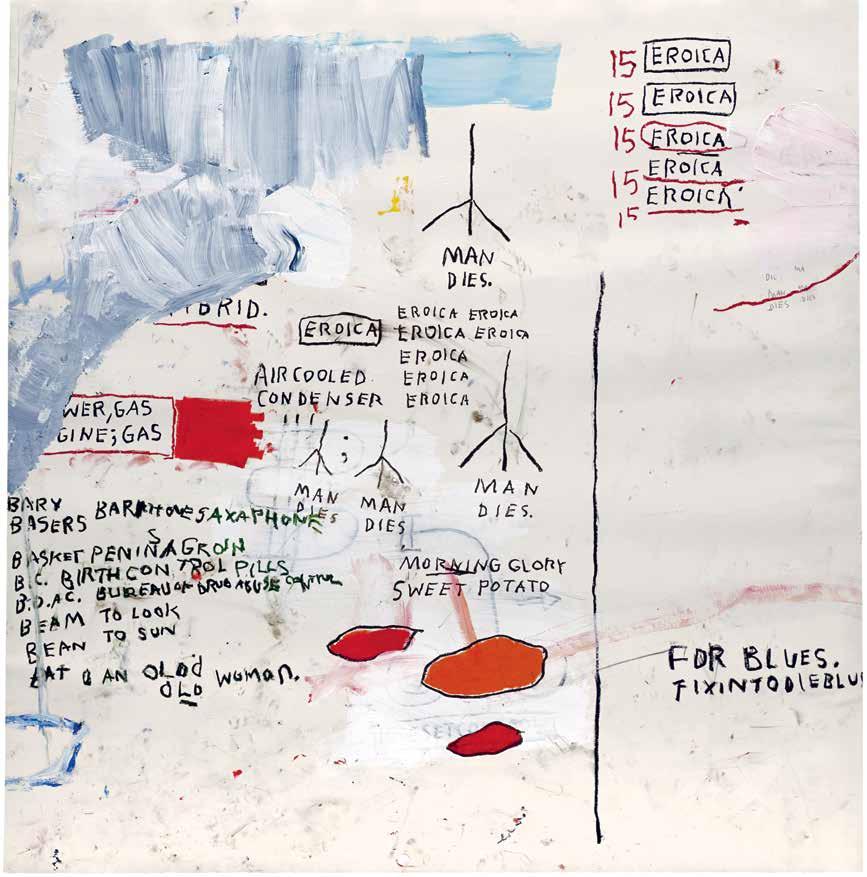

132

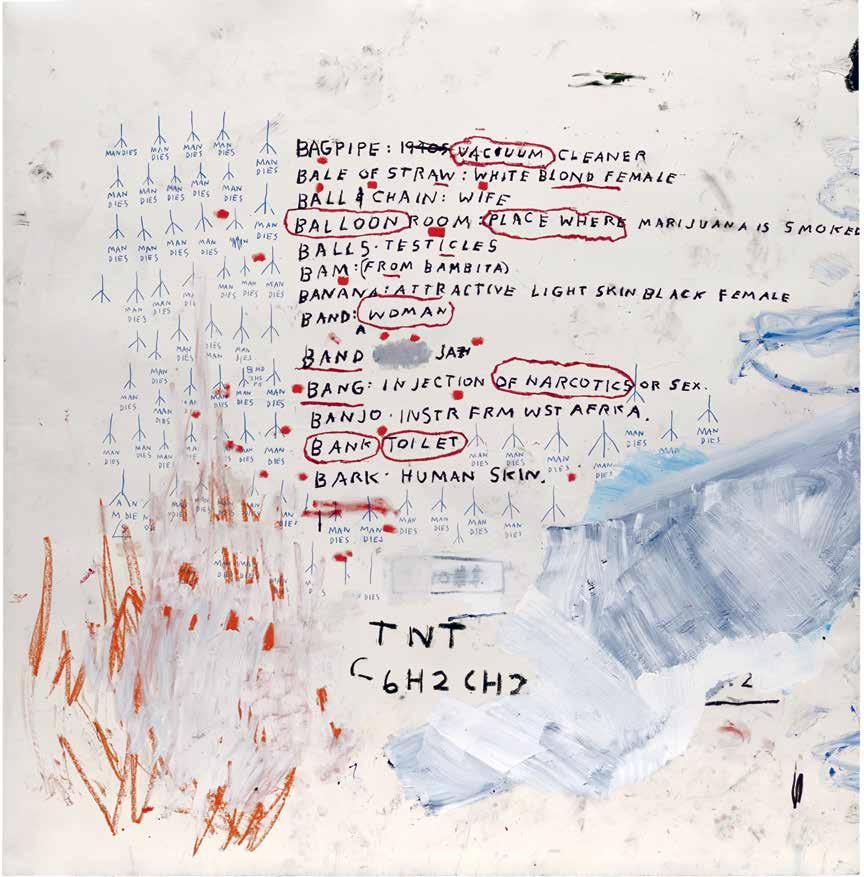

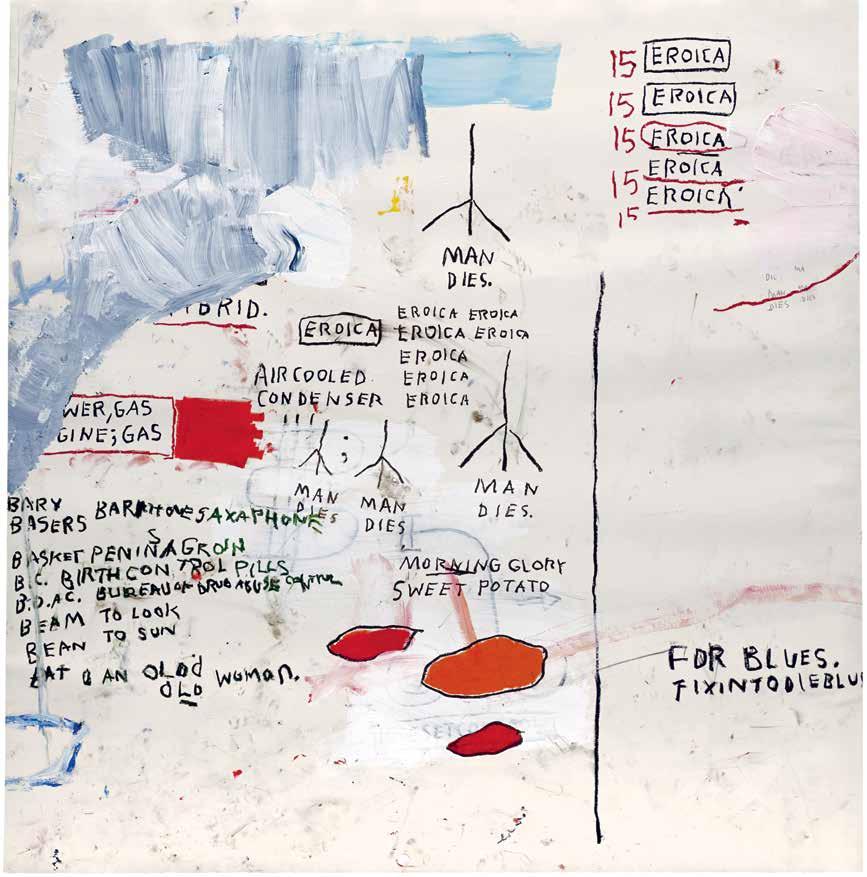

Eroica II, 1988, acrylic and oil stick on paper mounted on canvas, 230 × 225.5 cm

133

Eroica I, 1988, acrylic, oil stick and graphite on paper mounted on canvas, 230 × 225.5 cm

229

From Hip-hop to Blues and Beyond Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music 244

From Hip-hop to Blues

and Beyond

Seeing Loud:Basquiat and Music

From Hip-hop to Blues

and Beyond

Seeing Loud:Basquiat and Music

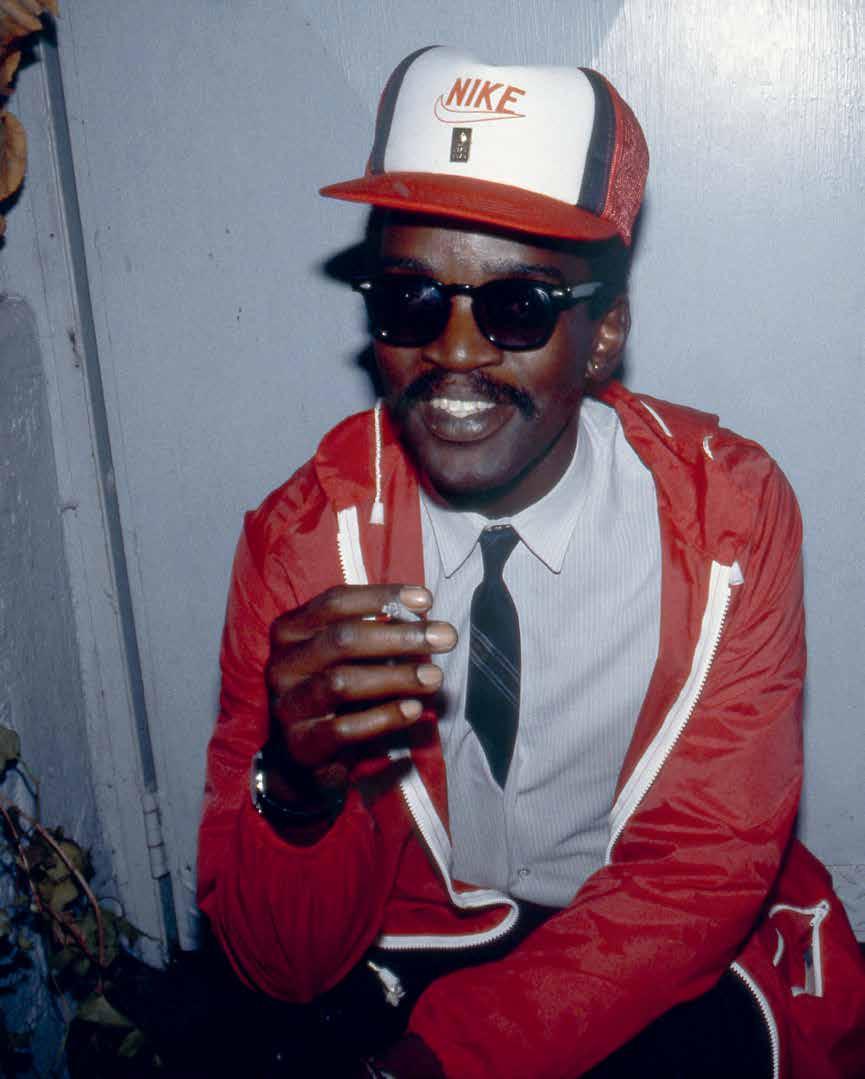

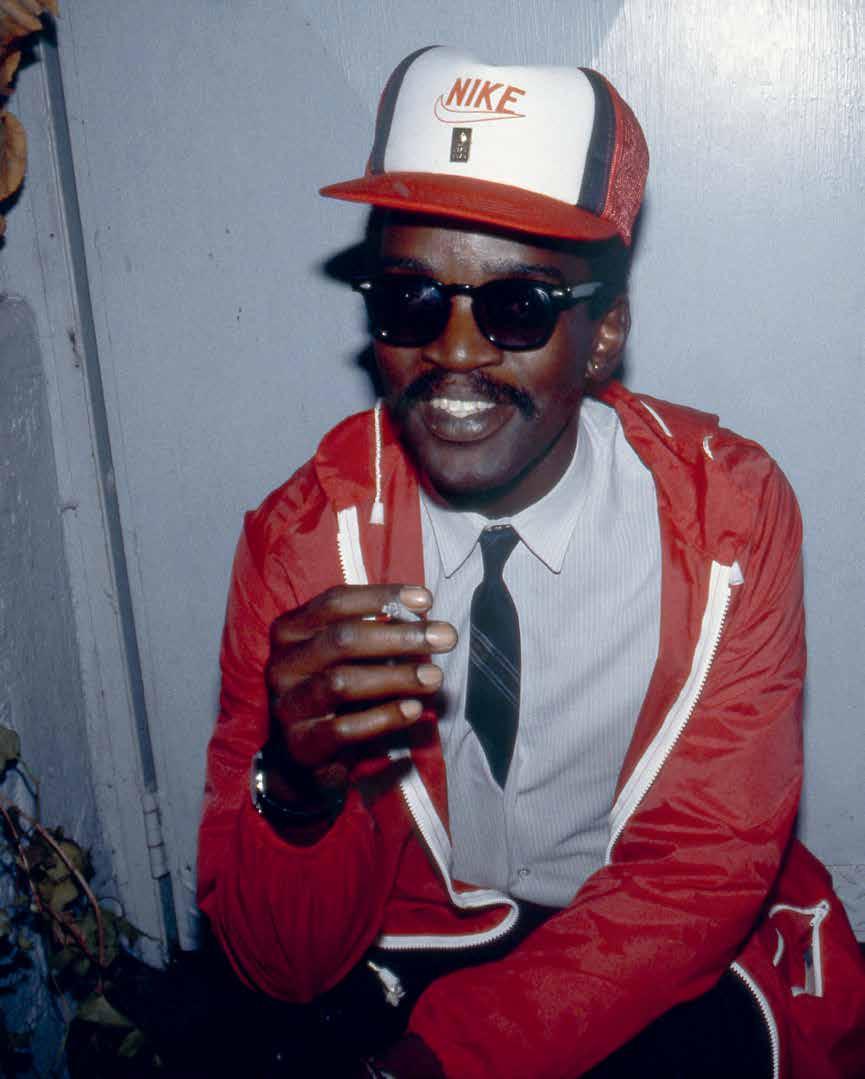

245 140 Fab

5 Freddy and Basquiat, New York, 1982.

Photo

Nan Goldin

Discover Basquiat’s musical world

This Stingray Music channel includes all of the tracks on this book’s Playlists and more.

From Hip-hop to Blues

and Beyond

Seeing Loud:Basquiat and Music

From Hip-hop to Blues

and Beyond

Seeing Loud:Basquiat and Music