Safe and Fun Adventures for All Ages!

Bioluminescent Kayak Trips

Kayak Camping Tours Day Kayak Tours and Rentals

Sea Quest combines 30 Years of experience guiding in the San Juans with the best pricing and the best routes for whale and wildlife watching in all of North America! Enjoy a great diversity of trip options including women only trips. Navigate along stunning sea cliffs and lighthouses in the wilder western San Juan Islands with camping opportunities on remote islands with eagles, otters and seals.

Rollover your old 401(k) or retirement plan assets into a Saturna Trust IRA.

It’s easier than you think. We can help.

• Take control of your retirement assets

• Sustainable investment options

• Most rollovers are tax-free

• No account or transfer fees

• Flexible beneficiary assignment

To learn more about how Saturna can help rollover your retirement assets, visit www.saturna.com/rollover

Investing involves risk, including the risk that you could lose money.

While there are no account or transfer fees for IRA accounts invested in Saturna’s affiliated mutual funds, ongoing investments in mutual funds are subject to expenses. See a fund’s prospectus for further details. Trades in a brokerage account are subject to a commission schedule. Wire transfers out of the account and expedited shipping of proceed checks may incur fees when these services are used.

IRA distributions before age 59½ may be subject to a 10% penalty. IRA distributions may be taxable. Rollovers are not right for everyone and other options may be available. Some retirement plans allow you to hold your assets in the account until you need them. You should check with your previous plan administrator about any fees they may charge. It is important to carefully consider your available options, including any fees you might incur, before choosing an IRA rollover.

Brokerage products are offered through Saturna Brokerage Services, Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary of Saturna Capital Corporation and member FINRA/SIPC. Saturna Trust Company is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Saturna Capital.

Since 1967 LFS Marine & Outdoor has served the Pacific Northwest community from its flagship store on Squalicum Harbor in Bellingham. The secret to our 50+ year success story has been dependable service that our customers have relied on through the most challenging times. We understand that our customers count on us to help them navigate a successful boating and outdoor experience. That is why we’re here for you, and that is why we’re here to stay.

“They have so much stuff!! Its a great place for any outdoors person or even DIY people. They have good prices too.”

- Google Review

Nick Belcaster is an adventure journalist who may be based in Bellingham but calls the ancient ice and spires of the North Cascades home. He contributes to local and national publications, focusing on the intersection of recreation, energy, and the environment.

Abram Dickerson is the owner/ principal at Aspire Adventure Running. As a husband, a father, and an entrepreneur, he attempts to live his life with intention and purpose. He loves mountains and the friendships that result from the suffering and satisfaction of running, skiing, and climbing in wild places.

The poet Roger Gilman lives in Bellingham and can be found around the Northwest along Cascade Mountain streams and in Puget Sound salt marshes fly fishing and birding for poems. Formerly the poetry editor of The Chicago Review, he is a philosopher of evolutionary ecology and restoration biology and served as Dean of Fairhaven College at Western Washington University. Roger currently serves as Poetry Editor of Adventures Northwest

Stephen Grace has authored many books, including Dam Nation: How Water Shaped the West and Will Determine Its Future and Grow: Stories from the Urban Food Movement; winner of the Colorado Book Award for Creative Nonfiction. He explores the Northwest’s natural history by snorkeling, paddleboarding, skiing, trail running, and backpacking.

Jason Griffith is a fisheries biologist who now spends more time catching up on emails than catching fish. Regardless, he’d actually prefer to be in the mountains with friends and family. Jason lives in Mt. Vernon with his wife and two boys.

After a successful career composing music for TV & Film in Hollywood, Ken Harrison moved his family to the PNW in 1992, searching for a better quality of life. The mountains became his refuge. He skis, snowshoes, camps, and hikes hundreds of miles on adventures from BC to the Olympics with Boomer’s Hiking Club, a group he founded. With photography as his hobby, Ken captures magic moments all along the way.

Rand Jack is a tree hugger of the first order. He likes to look at trees, think about trees, plant trees, and carve birds out of former trees. He opens each new piece of wood in reverent anticipation for what will be inside – the color, patterns, and perfect imperfections. Rand remembers the first time he saw a robin sitting in a tree he had planted.

Cindi Landreth enjoys exploring the western half of the U.S. with binoculars over her shoulder and a camera handy. Cindi retired from co-ownership of A-1 Builders and Adaptations Design Studio. She has dabbled in pottery, scrimshaw, felting, drum and rattle making, and jewelry and is currently enjoying photography and basket weaving.

Alan Majchrowicz is a landscape and nature photographer living with his family in Bellingham, WA. His images have appeared in advertising campaigns, product design, tourism brochures, books, magazines, and calendars. Learn more at alanmajchrowicz.com.

Ross Schram von Haupt is a landscape photographer based primarily in the Pacific Northwest, but he’ll go anywhere where there are mountains! Born and raised in the PNW, he spent his childhood exploring the outdoors and now is known for his dramatic landscape images and milky way photography. See his work at rosssvhphoto.com.

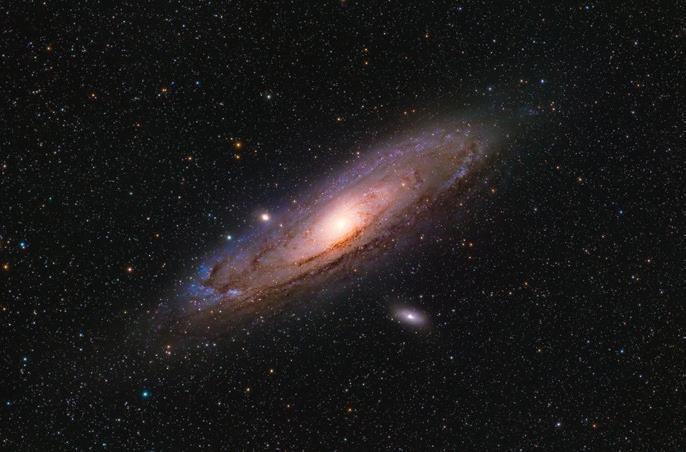

Damian Vines is a professional commercial photographer based in the Pacific Northwest. However, his astrophotography hobby truly inspires him and is what he’s most passionate about. Photographing and learning about the wonders of our universe are never-ending and ever-challenging pursuits. Visit him at: damianvinesphotography.com

Aftera recent dinner at one of downtown Bellingham’s fashionable bistros, my wife and I drove home through an urban landscape that was – for all intents and purposes – unrecognizable when compared to the downtown of yore: new multi-story buildings lined the streets, open spaces that we took for granted vanished beneath concrete and security gates. The downtown core, beginning to look like an inner city, had a locus of suffering: the unhoused wrapped in their ragged sleeping bags, a vivid testament to the current dysfunctionality of what used to be called “the social compact.”

It’s been a tough stretch for humanity these last years, and the weight of the pandemic, the wars, the psycho-political turmoil, and the looming ecological threats have cast a vast shadow. Times that try one’s soul? An argument could be made.

As I drove the familiar streets of the City of Subdued Excitement, I also felt the sadness that so often accompanies change on a personal level: the backdrop of memories transmogrified and our once-halcyon expectations unmet.

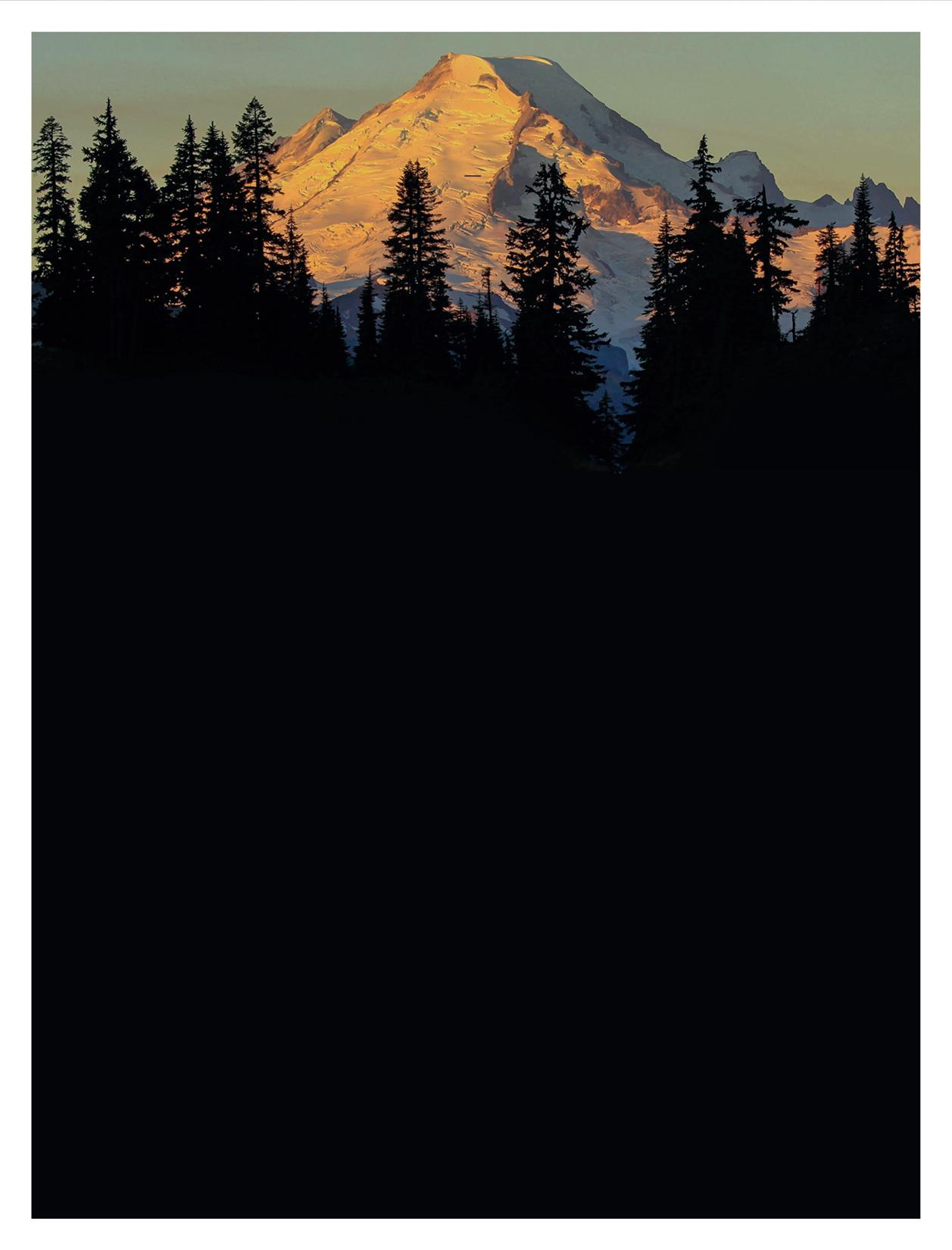

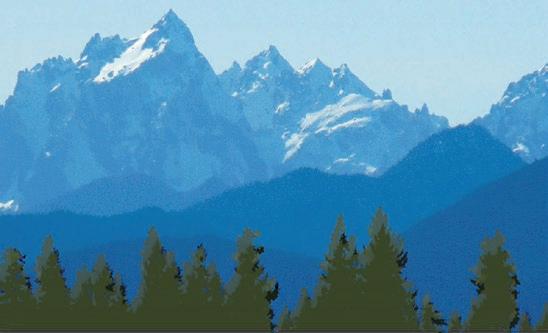

But then Mt. Baker came into view as I turned up Alabama Street: its great radiant cone gleaming like the heyday of Hollywood, burnished with a golden luster by the last lingering rays of the sun.

Suddenly my memories shifted to a sparkling autumn morning, back in 1998 when I first walked across the summit plateau of that great mountain with my son Ethan. We called it Koma Kulshan, then.

Still do.

Change: The Destroyer of What Was. Inevitable and never-

ending. What matters is our response. We waste/expend our energy attempting to vanquish uncertainty, which after all, is the calling card of change. But here’s the thing. In a fundamental, rock-solid way, some things offer us constancy, a reliable continuity of grace and beauty. Koma Kulshan, as I’ve already said, is a great example. Not that it’s unchanged. Of course, the glaciers are shrinking, and Lord knows, there are throngs of supplicants these days instead of just me, you, and your friends. But, by God, when I saw that mountain gleaming in the radiant light of an earlysummer evening, I was transported and grateful.

The future is uncertain, true enough, but it’s a beautiful world, and we’re lucky to be here. Summer in Cascadia is a gift that is rarer than we might think. Therefore, it behooves us to grasp it with both hands, with gratitude, and with unapologetic passion.

Happy Summer!

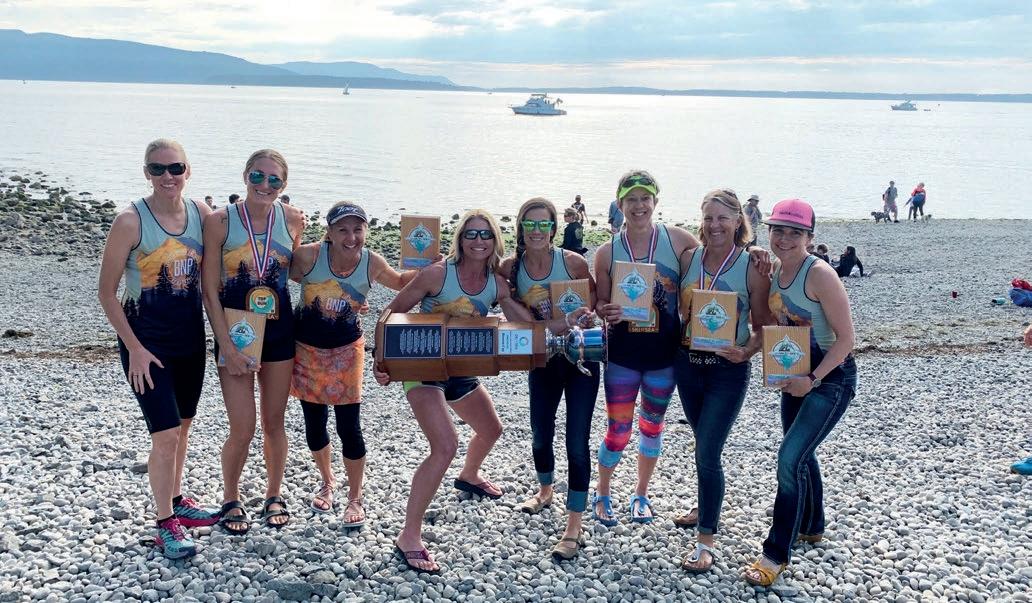

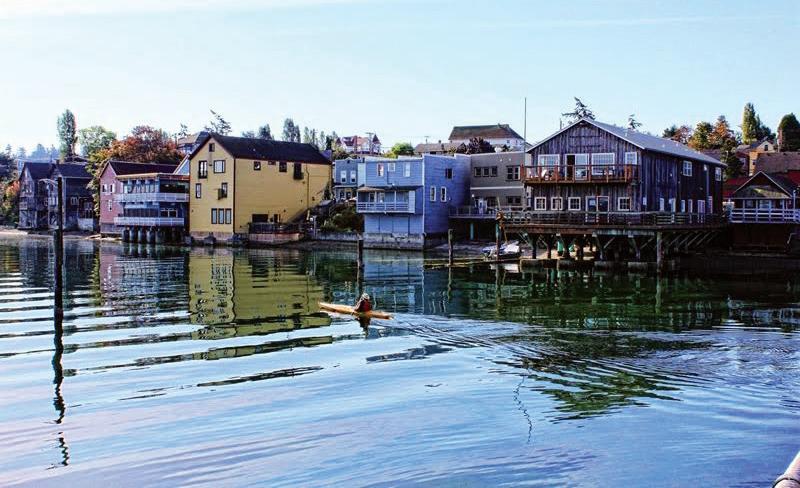

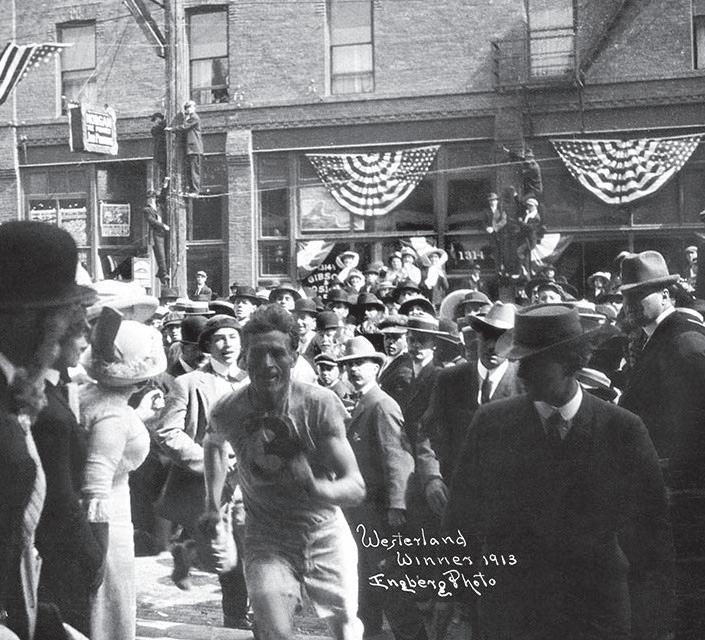

To describe Yachting Magazine as the journal of record for those who ply our coastal waters (and mid-oceans) in artfully engineered sailboats is not hyperbole. Publisher Oswald Garrison Villard published the magazine’s first issue on New Year’s Day, 1907. Over the years, the magazine began putting on seminal ‘Race Week’ events across the U.S., yacht races that possessed both towering prestige and a rollicking good time. Race Week debuted on Whidbey Island at Oak Harbor in the early 1980s, joining such premier yachting destinations as Key West, Catalina, and Solomon Island. Supported by sponsors like IBM and Audi, the Whidbey Island Race Week prospered and became a jewel in the crown of the American yachting scene.

For nearly four decades, Race Week called Whidbey Island home. With its reliable afternoon westerlies, Penn Cove drew sailors from hither and yon to race, party, and play; the week was often described as “adult summer camp.”

But by 2015, after maintenance issues in Oak Harbor—primarily a lack of dredging—Race Week was looking for a new home. In 2020, Point Roberts was chosen, due to its easy access for

Canadian boats, deep-water harbor, and “remote island feel,” according to Race Week Event Producer Schelleen Rathkopf, who purchased the event in 2014. The move was scheduled for 2020, but…then the pandemic hit, and the US/Canada border shut down. So it was back to the drawing board for Rathkopf.

was perfect. An excellent race area off the Northeast shores of Guemes Island sealed the deal.

The first Race Week in Anacortes was held in 2021, but the pandemic curtailed much of the social aspects of the event. This year’s Race Week (June 26-30) marks a milestone as the post-race parties are returning after the COVIDcaused hiatus. “Covid was tough to navigate,” Rathkopf says, “and everyone is relieved that 2023 marks a step towards ‘normal’ again!”

She discovered the perfect location in Anacortes, where the City and Port, as well as the Anacortes Yacht Club, “made the choice very easy.” The wealth of transient moorage at Cap Sante Marina, combined with the adjacent RV Park and excellent shoreside amenities, including motels, hotels, and restaurants within walking distance of the marina,

Race Week attracts the region’s most competitive sailboat racers and their crews to test themselves on the Salish Sea. There are awards to be won and lots of fun to be had. Rathkopf lives, eats, and breathes Race Week. She’s participated in one form or another since the early 2000s, nearly a quarter century now, and served for a time as editor of Yachting Magazine. It’s in her blood. And her family’s.

“I have two children who have grown up with Race Week on the Race Committee boat, who are now ages 14 and 17, who could not imagine a summer without Race Week.” More info: www.raceweekpnw.com

Bellingham’s Recreation Northwest, long a proponent for outdoor education and experience, celebrated the opening of their Outdoor Classroom Native Plant Garden in the Hundred Acre Wood on May 4. This project, located at the entrance to the 112-acre park on Bellingham’s southside is the result of a partnership between Recreation Northwest and the City of Bellingham.

Amenities include wooden benches and a stone stage, as well as native plant and invasive species identification signs. “Having dedicated places for people to connect with one another and with nature is core to an outdoor education program approach,” says Recreation Northwest Executive Director Todd Elsworth. “The use of our Rock Bench & Native Plant Garden area as meeting spaces demonstrates the community need and interest in dedicated space for small groups to gather in our parks.”

The organization’s connections with the area run deep: in 2014, they led the effort to build the Fairhaven Park Trail and Wetland Boardwalk that now leads south into the Hundred Acre Wood.

Once an event-oriented enterprise (they launched both the Bellingham Traverse and Recreation Northwest Expo), the organization has become more focused on education and stewardship in recent years, partnering with both governmental agencies and private benefactors to create a plethora of opportunities for the public to interact with nature. More info: www.recreationnorthwest.org

As of this April, you’ll need to pay closer attention to storing your food in the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest. Human-bear interactions have been on the rise and in response, the Forest Service has issued new restrictions designed to minimize these unwelcome interactions and ultimately, to avoid killing bears that become habituated to human food.

For backpackers, this means using a bear-resistant container (approved bear can) or hanging your food at least 10 feet high in a tree (or bear pole) and four feet from the trunk (or pole) while in the backcountry. For car campers, this means storing your food in the trunk of your car, not in the backseat—unless the food is in a bearresistant container. Hint: a cooler is not a bear-resistant container.

More Info: www.fs.usda.gov/alerts/mbs/alerts-notices/?aid=79673

A delightful walk through ancient forest will transport you from the hustle and bustle of the North Cascades Highway to the silence of Fourth of July Pass, an early-season favorite. After two rapturous, mostly flat miles beside Thunder creek (they would call this a river in a lot of places), cross a bridge, and in .25 miles, hang a left on the Fourth of July Trail. Begin climbing, and 2.5 miles and 2000 feet of elevation gain will elevate you to the pass and views of the surrounding mountains, including Colonial and Snowfield Peaks.

Trailhead: From the west, turn right off the North Cascades Highway (WA-20) into the Colonial Creek Campground, just past MP130, and follow signs to the trailhead near the campground’s amphitheater. NPS Backcountry Camping Permit required for overnight stays.

The North Cascades are home to some of North America’s most spectacularly located fire lookout cabins. The Park Butte Lookout, with its front-row seat beside the spectacular south face of Mt. Baker, is undoubtedly on that list. The trail (7.2 miles roundtrip) is delightful, beginning in lovely Schreiber’s Meadows, crossing the tumult of Rocky Creek on a seasonal suspension bridge, and climbing well-orchestrated switchbacks through the forest to Morovitz Meadows, a lush alpine garden. Turn left at a junction in 2.3 miles and climb past a series of beguiling tarns to the venerable lookout cabin. The total elevation gain is 2100 feet.

Trailhead: From the North Cascades Highway (WA-20) near MP82, take the Grandy-Baker Lake Road for 12.5 miles. Take a sharp left on FR-12, an unpaved but generally good gravel road. At 3.5 miles, turn right on FS-13. You’ll reach the obvious trailhead in 5 miles. USFS Northwest Forest Pass required.

Who needs a Stairmaster when the trail to Trappers Peak is just up the road? After a more-or-less flat two-mile walk, this epic route climbs some 3800 feet in a scant three miles, requiring some seriously vociferous grunting. But oh, the view from the top! If there’s a better trail-accessible vantage point for the magnificent Picket Range, I haven’t been there. Below the treeline (after the first two miles of smooth sailing on an old roadbed), the trail is a rooty mess, and above it, a rocky obstacle course. In 4.2 miles, you’ll reach a junction where the left fork drops like a greased stone to the remote and lonely Thornton Lakes. If you make that choice, you’ll lose 600 feet of elevation in less than half a mile. The right fork continues upward over rugged rockscapes toward the summit of 5960-foot-high Trappers Peak. In places, you’ll be using your hands. The views are stupendous. Towering Mt. Triumph is close at hand, but the mythic, fearsome, toothy Picket Range is the star of the show.

Trailhead: From the west, turn left on Thornton Lakes Road between mileposts 117 and 118 on the North Cascades Highway (WA-20). Follow this often-rough road for five miles to the road-end trailhead. USFS Northwest Forest Pass required. NPS Backcountry Camping Permit required for overnight stays.

I felt like I was metamorphosing along with these amphibians–transitioning into a more interesting version of myself, regaining a childlike curiosity I had lost long ago.

Near the High Divide of Olympic National Park, I entered the sapphire waters of Hoh Lake and snorkeled with thousands of pollywogs.

These tadpoles were all squiggling in the same direction: clockwise. I matched my swimming pace to their movement, and together we traveled through the shallows along the shore. Being part of this mass migration was as thrilling as paddleboarding with orcas, which I’d experienced a few months earlier when a pod of Bigg’s killer whales visited my backyard waters at Discovery Bay.

When I emerged from Hoh Lake, I saw the shore piled deep with what I thought were froglets. Later naturalist Dennis Paulson set me straight—I had been swimming with western toad pollywogs, and the hordes of what I thought were froglets were toadlets. Dennis explained that the black pigmentation of these western toad pollywogs is warning coloration, as opposed to the cryptic coloration of other pollywogs that camouflages them from predators. Frog pollywogs tend to disperse and hide, while toads rely on the poison in their skin to protect them. Western toad pollywogs may swim synchronously and pile together on the shore to warn predators that they are not a palatable meal. Scientists are still trying to make sense of this strategy. Had I learned this before I swam in Hoh Lake, I would have found it interesting; after

joining a living cloud of toad pollywogs in motion, it struck me as fascinating. I began snorkeling in the Salish Sea a few years ago when I was given a sec-

ondhand wetsuit. It fit me poorly; water flooded the suit each time I moved my arms. But I wanted to take my tide pooling explorations to another level, so I tentatively entered the Strait of Juan de Fuca. I gasped and then hyperventilated—what is called “cold shock.” I worried that what

I was doing was weird, maybe dangerous. My doubts dissolved, however, when I watched a moon jellyfish pulse with a hypnotic rhythm underwater—more relaxing than any meditation technique I’ve tried. Silver herring swam in unison, circling like a mirrored disco ball as they were chased by seals and seabirds. After I saw a little fish with an oversized head and a beguiling snout hop across a barnacle shell on its fins as if they were feet—a grunt sculpin, perhaps the cutest and most charismatic fish on the planet—I became a committed convert to cold-water snorkeling.

I was fascinated by the life I saw in the Salish Sea’s kelp forests and eelgrass meadows. But after spending several months sheathed in uncomfortable neoprene, schlepping diving gear in a backpack while hiking shorelines, and haul-

ing the gear on my paddleboard when looking for whales, I decided I wanted a more minimalist approach. The freedom to slip beneath the water’s surface whenever I craved a glimpse of life below was alluring. One day, I decided to ditch my wetsuit and train my body and mind to adapt to the cold.

I made mistakes during my early training attempts. Determined to swim across both Flapjack Lakes one October day after a snowstorm frosted the ground in the Olympics, I lingered too long in the water. When I got out, the violence of my shivering seemed like a seizure, and my jaws chattered so forcefully that I bit down on my sleeping bag to keep my teeth from cracking. I was mad at myself for ignoring my limits and being cavalier. But not for a moment did I consider quitting. I was hooked.

The benefits of cold-water immersion to physical and mental health are profound: improved cardiovascular fitness, a boosted immune system, and an

enhanced ability to cope with stress. Cold shock provokes an immediate shift in neurochemistry. A fight-or-flight flood of chemicals alters how we think and feel, preparing our bodies and brains for action as we cope with the cold. Noradrenaline and cortisol are released in our nervous system, sharpening perception and speeding up the workings of the brain—an amphetamine-like reaction. Endorphins flood the system, producing an opioidlike alleviation of pain and a general feeling of well-being. Dopamine kicks off a powerful psychological reward, similar to the effects of cocaine. Serotonin boosts mood, akin to the therapeutic benefits of antidepressants.

The altered neurochemistry produced by cold water immersion delivers a powerful sense of bliss that I wouldn’t have believed possible if someone had tried to talk me into putting my bare body in a 50-degree sea—a ludicrous proposition! I slithered into this situation by happenstance and got hooked.

But my primary motivator to swim through rapids or hike thousands of vertical feet to an alpine lake and then snorkel in chilly water is the opportunity to enter an alternate world and have a memorable natural history experience. I spent years fly-fishing—yanking struggling trout with a rod and line from their world into mine. I’m done with that. Now I love swimming with salmonids, especially in rivers. Several times this past summer, I swam with coho salmon in the Dosewallips River as they battled their way upstream. I watched male chum salmon, canine teeth protruding from their savagely hooked jaws, guarding their spawning nests or redds. The male chum look as ferocious as alligators. When they approach within a few feet of my mask, lightning bolts of terror travel my spine. But I’m also stunned by their beauty: the vertical striping of purple and green on their sides, the hydrodynamic shape of their bodies, and the ink-black pupils centered in the golden discs of their eyes.

I’ve watched anglers who are casting to coho salmon kick at chum salmon on their redds and deride this species as a “trash fish.” I’m sure the perspective of these misguided souls would change if they spent time with these extraordinary creatures underwater and entered their world. All salmon are marvels.

When I swim the same routes salmon do, working my way upstream against the current, I tire easily, even while wearing kick fins for an extra boost. The fact that these fish have returned from the ocean, transiting thousands of

miles as they sniff their way back to their natal rivers, astonishes me. I appreciate spawning salmon now in a way I never did while standing on shore or running a trail alongside a river and climbing waterfalls to see anadromous fish spawn, a favorite pastime when I lived on the Oregon coast. To truly celebrate salmon, I had to get into the water with them and visit their realm with no wetsuit or special gear, just a snorkel and mask. Snorkeling with Chinook, or king salmon, has been transformative. This past September, as maples on the banks of the Elwha River showed the first yel-

low leaves of autumn, I entered the river one crisp morning to witness the return of the kings. I emerged from the water shivering from the cold but also shaking with emotion, stirred by the majesty of these beasts and by humanity’s efforts to save them by restoring their spawning habitat. Swimming with kings in the mighty Elwha, a rejuvenated river again flowing free between breached dams, a river regaining its ecological health, is a powerful experience. Yet, when you are an arm’s-length away from the toothy jaws of a forty-pound Chinook, its body slabbed with muscle, its brain ferocious with instinct, this salmon seems less like a fish and more like a living dinosaur, a primordial being that has somehow managed to persist on this Earth.

My cold-water snorkeling addiction has deepened through watching amphibians in mountain lakes. The first time I floated in an alpine tarn so clear that the water was perfectly transparent, salamanders in various stages of metamorphosis hovered above boulders of pillow basalt

formed ages ago when lava cooled in the sea long before the mountains rose, creating what looked like an otherworldly waterscape from another planet. There were no fish in this lake to prey on the salamanders as they turned from eggs to larvae to adults, and these creatures didn’t seem to view me as a threat. I floated among them, remaining motionless for several minutes at a time. As my body temperature dropped, I thought about an ancient sea creature, finned, gilled, scaly, and cold-blooded, that had given rise to tetrapods, back-boned creatures with four limbs. From a tetrapod that crawled onto land and pioneered a new world came amphibians. Then, after evolution’s invention of shelled eggs with amniotic sacs freed creatures from breeding in water; reptiles, dinosaurs, birds, and mammals evolved, including us. Through the clear water of this mountain lake, I extended a finger toward a larval salamander wearing a frill of feathery gills. It had sprouted front

legs with toes, but its back legs were mere buds. This tiny being, in the middle of transitioning, settled onto my outstretched finger. Enchanted, I felt like I was getting away with something—immersing myself in a world that humans have no business entering, or maybe returning to a world not as alien as we assume, revisiting our tetrapod ancestry in a watery womb.

Often I’m asked why I’m willing to shiver for a glimpse of what lies beneath the surface of Cascadia’s rivers and lakes. If the person asking seems unimpressed by my stories of salmon, toads and salamanders, I mention bears. Several times I’ve seen black bears swimming in lakes, and I’ve also been snorkeling in highcountry waters when a bear approached. Once, during a snorkeling session in Lunch Lake, where the water has an almost tropical green-glass clarity, after being mesmerized by brook trout for ten minutes, I looked up to get my bearings— and saw a bear on the bank. Blueberries

Finally, I quit hiking to the little lake in Heather Meadows to crouch peering in its alpine depth regarding my own mindfulness. Today

I sit on a boulder higher up the mountain eating a sandwich and tracking a hawk search Ptarmigan Ridge for baby food. I loosen my boots and embrace the ecology of raptors: a different kind of faith. Then the fog rolls in. But it no longer bewilders me, if it ever had.

were on the menu; the bear seemed less interested in watching a naked ape in the lake than in browsing on berry bushes along the shore. But I suspect I will add

“swam with bear” to my list of snorkeling experiences sooner or later. I imagine that one day while watching salamanders or fish, I will see paws paddling in front of my mask. Encountering the bubbling commotion of a swimming bear in a lake is a scenario that toggles back and forth in my mind between cartoon cute and utterly terrifying.

This past October, I took advantage of a spell of warm weather to make a solo backpacking trip in Olympic National Park from Sol Duc through Seven Lakes Basin, a place where bears abound. Tally of lakes snorkeled: nine. Number of bears encountered: zero. While snorkeling in Mirror Lake, where I had seen a bear swimming a month earlier from a vantage point atop Bogachiel Peak on the High Divide, I had an extraordinary encounter of a different kind; myriad brown specks were suspended in the water. I assumed these bits were some sort of debris, maybe pieces of sediment or algae, but when I reached toward the little dots, they moved

en masse. By waving my hands through the water in front of me, I caused millions of tiny organisms to move in slow swirls as I swam. I felt like a sorcerer lording over a microscopic realm. I stayed in the water right up until the twenty-minute cutoff time I had promised my wife I would adhere to when snorkeling solo and sans wetsuit. Then, just before I crawled onto shore, the sun slipped toward the horizon. Low-angled light rays strobed through the clear shallows, probing the blue depths, setting an infinity of living specks aglow. Maybe the cold and the exertion of my adventure were affecting my middle-aged brain, but swimming in Mirror Lake that afternoon seemed an awful lot like flying through the cosmos.

Add “psychedelic perceptual effects” to the list of reasons to swim beneath the surface of mountain lakes. No magic mushrooms necessary.

Though I sound like a proselytizer for cold-water snorkeling, I haven’t been able to convince my wife to try it, and

thus far, I have precisely zero converts to my credit—though a herpetologist friend of mine tells me he might try it.

I told him about watching gravid newts swimming among the lily pads of Lake Margaret on the Low Divide in the Olympics. You could tell the female newts by their bulging bellies—they looked like they might at any moment burst with eggs. Gelatinous masses of newt eggs clung to branches underwater. Close inspection provided a glimpse of something beyond my imagination. Every clear jelly globe contained a newt tadpole in miniature, and each of these embryonic beasts was fringed with a little feather boa of external gills. Alien life! But when I gazed upon these transparent eggs, I also thought of human embryos and marveled at how strange and wondrous all life is. I felt like I was metamorphosing along with these amphibians—transitioning into a more interesting version of myself, regaining a childlike curiosity I had lost long ago.

I was being reborn in the fluid cradle of nature’s imagination.

Wild swimming seems more common across the pond, where Roger Deakin’s book Waterlog: A Swimmer’s Journey Through Britain is a cult classic. Although, a friend of mine from college in England just told me that a scandal about pollution clandestinely dumped into the rivers and lakes of the UK has tamped down people’s enthusiasm for swimming in wild waters. I’m grateful

for the relatively pristine rivers and lakes of the Pacific Northwest.

As long as my aging knees cooperate and carry me to streams and highcountry lakes, I will immerse myself in wild waters, where salmon, pollywogs, and salamanders will lead me through a world so much larger than my landbound brain ever thought possible. And I will send dispatches to my fellow humans from the crystalline cold beneath the currents and waves.

As the snow begins to retreat in the North Cascades, and the color scheme ever so slowly shifts from white to green, I get the itch.

Of course, having plied these North Cascades for numerous happy decades, I am used to waiting: there’s a lot of snow up there, and it melts out slowly, unveiling the vibrant greenery in its own sweet time. The hiking season will come. We must have faith.

It is during this time (when the itch has become almost unbearable) that Sauk Mountain calls my name. Located in Skagit County, near Rockport, the Sauk Mountain Trail climbs in gentle switchbacks up a south-facing slope that is among the first to emerge from the snow in these northern mountains, accessible some years as early as late June.

Virtually every step up the trail offers a feast for the senses: the views out over

the Skagit River Valley are constantly mesmerizing and the trail itself climbs through a lush, intensely green, pitched meadow. The scent of renewal fills one’s nostrils. After the long months of winter’s

pand to include waves of snow-covered peaks stretching to the horizon. To the southeast, Glacier Peak floats above the range. On a clear day, you can see Mount Rainier, like a fata morgana in the distance.

The flower show starts early with trillium and glacier lilies, and becomes an alpine Monet’s garden as the summer unfolds, one of the most prolific wildflower displays in these mountains: a riot of columbine, tiger lily, phlox, Indian paintbrush, penstemon, mountain hellebore, arnica, asters, and dozens more.

muted greys, the vibrant green of the slope—if not the uphill grade—will take your breath away.

As the switchbacks convey you to the top of the ridge, the views ex-

Achieving the top of the ridge after approximately one mile, the trail swings around to the peak’s north side, which will undoubtedly be covered with snow in the early season. Generally, the snow is not a problem as the route now traverses the ridge crest across gently undulating terrain. A new world of wild peaks opens to

Sauk Mountain is a popular destination, so expect company. Come on a weekday if you can. ‘Leave No Trace’ principles are mandatory, and it is essential to exercise care when hiking on the switchbacks to avoid dislodging rocks that could tumble downslope onto hikers below. This is not a place for unattended children.

the north, including a stupendous view of the dramatic Picket Range. Take a moment to drink it in.

A side trail descends to the right, leading down to Sauk Lake, far, far below. I must admit that although I’ve climbed Sauk at least a dozen times, I’ve never visited the lake. I have a well-established aversion to immediately losing elevation after having just gained it.

The ridge crest is marmot paradise—it’s common to see these critters scurrying across the meadows and rocks. I swear I once saw a pair of them boxing like old-time pugilists, the only thing missing were handle-bar mustaches.

In the early season, you should expect the rest of the route to the summit proper (where once a fire lookout cabin—occupied for a time in 1953 by Beat poet Philip Whalen—stood) to be snowbound. If there is snow here, take pause. If you don’t have an ice axe (and the requisite knowledge to wield it), think twice about going farther. There are many places on this precipitous slope where a slide would be extremely unpleasant. The emergency room is no place to spend an early summer afternoon.

If this is the case, find a comfortable place along the ridge (there are many) to sit back and watch the clouds caress the North Cascades for an hour or three. There is much to see: Baker, Shuksan, White Chuck, White Horse, Hidden Lake Peaks, and hundreds more. The Twin Sisters Range is close at hand. Beyond them, far to the west, the Salish Sea, crowded with islands, gleams like burnished steel as evening approaches. I like to hang around until the sunset paints the peaks pastel pink and magenta and then

hike down by headlamp, but that’s just me. In early summer, Sauk Mountain is a touchstone, a profoundly satisfying prelude to the season of alpine splendor in the North Cascades that waits in the wings. The minimal elevation gain (only 1190 feet to the old fire lookout site) and gentle grade provide a perfect reintroduction to mountain hiking for knees and psyche. The greenery is intoxicating, and the opportunity to gaze out upon a vast landscape of icy peaks is welcome indeed, a balm for the summer-hungry soul. At this time of year, I can think of few places better suited to sitting on a rock and counting one’s blessings. FOLLOW

Comfortable Tap Room featuring a unique collection of vintage beer bottles and memorabilia.

1900 Grant Street Bellingham 360.224.2088

10-Tap Custom Draft System featuring your favorite Barrel-aged North Fork Sours, Ales, and Lagers as well as our Famous ‘Collaboration’ Brews.

Follow the North Cascades Highway (WA-20) east for 35 miles from I-5, and turn left on Sauk Mountain Road (FS-1030) near milepost 96. Follow this usually bumpy unpaved road (highclearance vehicle recommended) for 7.9 miles until the road turns sharply right and climbs steeply uphill to the trailhead. This last short section is very rough, and some hikers elect to park along the road at the base of this section and walk the short distance to the trailhead. The views from the trailhead parking lot are better than many hiking destinations.

Open Monday, Tuesday & Thursday 3:00 - 9:00 pm Friday - Sunday 1:00 - 9:00 pm Freshly-Brewed Small-Batch

Open Monday - Friday 1:00-9:00 pm

Any way you slice it, a consistent running practice requires a huge amount of effort. The daily/tri-weekly/bi-weekly ritual of overcoming one’s own lethargy and lacing up for miles requires cultivating a wellspring of mental fortitude and resilience. Just about any reason to get off the couch and out the door is a good one. But sustaining the practice beyond a few weeks or months and embracing movement as a lifestyle requires honing in on deeper currents of motivation and inspiration.

Volumes have been written on how to create motivation. Visualization, goals, mentors, checklists, systems, and incentives all circulate about how to effectively manifest the possibility of future rewards and events into the reality of present actions. So whether that’s carefully crafting the perfect race calendar (or a moment of alcohol-induced inspiration) resulting in signing up for some epic race in the way-too-near future, we all benefit from stepping out of our comfort zone.

In this respect, running is an act of rebellion. At some fundamental level, our collective socio-economic strivings are an effort to contain and constrain the uncertainty of life. Not that we don’t need food, shelter, and gainful employment to operate in this world, but all too easily, the currents of consumption can swallow the life out of living. It’s easy to fall into the trappings of dedicating an exorbitant amount of effort and resources to create a life that avoids the inevitable

mysteries, uncertainties, and curiosities of living. Which begs the question, what are we left with?

I participate in the “system.” I shop on Amazon, burn fossil fuels, pay a mortgage, and look up dinner recipes online. But I also run to remember that all of this is fleeting. I run to play with the edges of the map, to test the limits of my endurance, and to explore the world in its raw, rugged, relentless reality. I am alive when I am intentional about exploring what lies beyond what I know. In this practice, running is about being curious and embracing uncertainty. It’s a process of cultivating tools and techniques to transgress culturally-imposed limitations and to be comfortable in spaces that are uncomfortable and unconventional. In contrast to a world where answers are found online, to disconnect is to reconnect with an internal awareness of ‘Self’ and to give that ‘Self’ space to unfold and reveal itself to itself.

After a long winter of grinding out miles on trails close to home, I’m eagerly anticipating the approaching summer and thinking of all the trails, summits, link-ups, and unfinished projects that will take me into uncharted territory. I’m curious about what lies in the hills, anxious to find myself somewhere new, and motivated to get out the door today, so that tomorrow I can find myself lost all over again.

RACE! PARTY! PLAY!

June 26-30, 2023 l RaceWeekPNW.com

THE PARTIES ARE BACK!

"Race Week in Anacortes exceeded our expectations in every way."

Spencer Kunath, Navigator TP52 GloryPhotos by Jan Anderson

Iused to feel so small when I looked at the night sky. When I was young, my father and I watched Cosmos, the Carl Sagan show on PBS. Watching that show and seeing the imagery of those otherworldly celestial bodies gave me my first real sense of wonder. It’s the first time I remember wanting to learn more about something. Fast forward 40 years; Now I can take the types of photographs that gave me such wonder as a child, to experience a closer connection to the universe. I don’t feel so small anymore.

See more of Damian Vine’s photography at: damianvinesphotography.com

Visit AdventuresNW.com to view an extended gallery of Damian’s astrophotography.

In the long-ago summer of 1995, I visited the “community forest to be” in the foothills of the North Cascades with my 14-yearold daughter Kelsey.

She sat leaning against an old tree in the ancient forest. “No one would ever dream of tearing down the ancient cathedrals in Europe,” she observed. “How could anyone even think about cutting down this ancient forest?”

State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) with the idea of a land exchange that would move these lands from private

The story of saving Canyon Lake Community Forest began a few years earlier, in 1993. Shirley Van Zanten, Whatcom County’s County Executive, had compiled a list of privately owned Whatcom County lands that she felt should be publicly owned. She approached the Whatcom Land Trust (WLT) to find a way to move the lands to public ownership. The view and waterfront property on Van Zanten’s list, prime for development and recreation, was far too expensive for Whatcom County to buy. Trillium, a local company, owned most of that property and also held extensive timberlands in Whatcom County. WLT approached the

to public ownership.

To make the exchange supportive of DNR’s central mission of revenue

production from forest management, DNR engaged Trillium and expanded the exchange to focus on consolidating or “blocking up” DNR and Trillium’s respective ownership of forest parcels. Meanwhile, DNR was folding some 10,000 acres of property on Van Zanten’s list into the trade. DNR and Trillium were motivated to improve forest management efficiency; Whatcom County and WLT were motivated to move key parcels from private to public ownership. Working together, DNR and Trillium enlarged the complex land exchange to encompass some 27,000 acres. It came to be known as the Great Land Exchange of 1993. Meanwhile, two local hikers, who liked to prowl the off-the-beaten-path woods of Whatcom County, found some large stumps on DNR property on the ridge near Canyon Creek’s headwaters, high above the Middle Fork of the Nooksack River. The stumps were next to what appeared to be an old-growth forest owned in part by DNR. Counting the stump’s growth rings was difficult because they were so fine, but it was clear that the trees had been very old. The friends reported their discovery to WLT.

Though WLT had been the land exchange cheerleader for months, when it came time to sign off on the deal in a room full of stakeholders and computer jockeys, the Land Trust hesitated. I told the Trillium representatives that WLT could not support the exchange because a substantial old-growth forest property on the ridge above Canyon Creek moving from public DNR ownership to private Trillium ownership was going in the wrong direction. After receiving dagger glances from Trillium representatives, WLT and Trillium agreed to conduct a professional forest assessment. Given its altitude and orientation, Trillium would commit to making a good-faith effort to conserve the forest if it were deemed an unusual forest. If not, WLT would back off.

We each nominated someone to do the assessment. Trillium came up with Beak, Inc., and representing the Land Trust, I contacted forest ecologist James Agee at the University of Washington School of Forestry. With a little poking around, I learned that the principal at Beak Inc. was Agee’s former student. So I told Trillium, “Why hire the student when you can hire the professor for the same price.” And that was that.

Starting on the ridge above the 750-acre old forest, Canyon Creek eventually empties into the Middle Fork of the Nooksack River just south of where the North and Middle Forks merge. A landslide dammed the creek some 200 years ago to form the 45-acre Canyon Lake. In the Mountain Hemlock Zone, Mountain Hemlock, Alaska yellow cedar, and Pacific silver fir characterize the forest. It ranges in elevation from 3400 to 4360 feet and stands on north-facing slopes. The forest catches the moist air from the Pacific, causing frequent fog, heavy rainfall, and extremely deep snowpack that melts slowly due to the forest’s north-facing slopes. These critical ingredients have enabled the forest to escape the fires that have historically swept the Cascades every 300 to 400 years.

I got Dr. Agee’s report in November 1993, just as I was about to board a plane for Chile. When I began to read, a smile spread across my face. Agee had taken core samples only from mountain hemlocks, the largest but not the oldest trees. On a 20 x 20-meter plot, Agee found five mountain hemlocks that were more than 800 years old. Extrapolation of the data indicated the likelihood of 50 such trees per acre. His conclusion was clear. “The CLOG [Canyon Lake Old Growth] parcel is one of the oldest forest stands in the Pacific Northwest.”

According to the Seattle Times (11/10/97), when Agee first set foot in the old forest, “he quickly sized up the tall stands of mountain hemlock and Alaska yellow cedar as 300 to 500 years old. A nice old-growth forest, he thought. Not an extraordinary one.” But a very different picture emerged when he took mountain hemlock core samples back to his lab for processing. “When I sanded them down and counted the rings, I thought, Oh, my God, these are very old trees... what I’m seeing is rare because they are so old,” he said. The article in The Times amplified the importance of the forest beyond Whatcom County.

In 1997, Trillium granted an option to purchase the 350-acre holding in the ancient forest it had received from DNR in the Great Land Exchange. WLT formed a partnership with the Trust for Public Land, a national conservation organization, to pursue the purchase of the forest. That same year, Trillium sold its holding in the Canyon Creek Valley to Portland-based Crown Pacific, which owned the remainder of the forest. So now WLT had a cooperative and an enthusiastic partner personified by Crown Pacific’s timberland manager, Russ Paul. Russ quickly agreed to honor and expand the purchase option to include the entire 750 acres of old-growth forests and the adjoining naturally reproduced younger forest that closely matches the old forest in conifer diversity. But there was a deadline. The

Your Perfect Day: Hike, Bike, Golf.

Then a Thrilling Concert

July 1—18, 2023

Five Guest Conductors, Five World Famous Guest Soloists, Beer & Wine Garden + Food Trucks

option expired at the end of November 1998.

The sale price—$3,690,000 ($6,810,047 in today’s dollars), was more money than WLT had ever even dreamed of raising. But then, we had never had a cathedral of ancient trees within reach.

Our big break came when the Trust for Public Land put WLT in contact with the Seattle-based Paul Allen Foundation. I took the Foundation’s representative, Bill Pope, to see the forest. As we sat on a big rock at the forest edge, looking down at Canyon Lake and the Canyon Creek Valley, Bill asked, “What exactly do you want to purchase?” I

pointed to the adjacent forest and replied, “The stand of old-growth trees.” He said, “You’re thinking too small. You need to

ancient forest, the 45-acre lake, 1,460 acres of young, mixed conifer forests (today ranging from 30+ to 70 years old), numerous streams, and 50-million-year-old palm fossils.

Recognizing the impact of the $1,846,000 vote of confidence from the Allen Foundation, I contacted WLT’s most persistent and generous supporter. She agreed to anonymously donate one million dollars. The project now seemed possible.

buy the whole valley, and we’ll give you half of the money.” And that is what the Paul Allen Foundation and WLT did. The project now included the 750-acre

To celebrate and build on these amazing gifts, WLT scheduled a press conference in the forest for July 8, 1998, and invited preeminent forest ecologist Dr. Jerry Franklin, Professor of Ecosystem Analysis at the University of

Whale Watching & Lunch Cruises

Chuckanut Bay Crab Dinners

Friday Harbor Sightseeing

Sucia Island Picnics

Bird Watching Cruises

Bellingham Bay Brewers Cruises

UnWINEd on the Bay

Washington School of Forestry, to speak in the forest about the forest. Franklin is often referred to as the “Father of Old-Growth Forests” because of his pioneering scientific work with colleagues to show that old-growth forests are complex, unique ecosystems and his tireless advocacy for protecting these forests. Here is some of what he told us as we listened among the ancient trees:

“If you want to see the oldest representatives of our species, you come to a place like this where it’s cool and moist, and the tempo of the life processes is relatively slow. So here, because of their ‘I’ll grow slowly, but I’ll last a lot longer’ kind of philosophy, you have trees that exhibit their maxi-

mum lifespans. The mountain hemlocks here are 800 years or older, the oldest of any mountain hemlocks, and the silver

another 2000 years. So one of the neat things about this particular forest and place, if left to its own devices, it’ll probably persist as it is for the next 1000 years, 2000 years because it’s not a place where fire comes frequently, but a place where all of the species are quite capable of perpetuating themselves in essentially this form forever.”

furs are probably…650 to 700 years old, again one of the oldest tree species on the site. Some of the Alaska cedar are over 1000 years old. In fact, they may live for

Newly-elected Whatcom County Executive Pete Kremen was at the press conference, as was Crown Pacific’s Russ Paul. Kremen said at the time that he thought WLT “could expect to see a substantial amount of money from Whatcom County,” sourced from the voter-approved tax

levy Conservation Futures Fund. “This is exactly the kind of project the Conservation Futures Fund was made for,” he declared. His words were just what we needed to hear. Pete later told me that his work to help acquire the community forest was probably the most important thing he did in his tenure as county executive.

Ominously, as we left the press conference, a huge, two-prop helicopter flew across the valley from a nearby logging operation with a giant log dangling from a cable as if to say, “Don’t let this happen to you.”

Smaller donations also began to flow in. For instance, Derek Franklin, age 10, contributed a portion of his allowance to help save an old-growth forest. Derek wrote: “I’m donating because I recently received a Super Nintendo system, and I wanted to donate money to help balance the world between electronics and nature.”

With the deadline looming, Crown Pacific reduced the sale price by $146,000, leaving us exactly $700,000 short.

WLT marshaled endorsements from an unusual coalition of environmental, business, timber, and real estate groups.

In response, the County Council unanimously voted on September 29, 1998, to allocate $700,000 from the Conservation Futures Fund to “seal the deal.” As an added bonus, Crown Pacific donated to

that the company had removed from the forest site. While preparing to close the purchase, I told Russ Paul, “There is one more thing.” Russ looked at me quizzically. “You need to return the fossil to where it belongs.” Russ smiled and said, “OK.”

The transaction closed on December 1, 1998. WLT donated the entire Canyon Lake Community Forest jointly to Whatcom County and Western Washington University and retained a restrictive conservation easement protecting the property in perpetuity.

WLT a 98-acre riparian conservation easement 2.5 miles long and 200 feet wide on both sides of Canyon Creek below the purchased property.

In front of the Crown Pacific office in Hamilton, WA, I had noticed an intact 50-million-year-old palm frond fossil

On June 3, 2002, I saw a cloud of dust moving up Canyon Creek Road. The dust was following a flatbed truck with a giant, 6-ton slab of rock strapped to it. This was no ordinary rock. It contained the 50-million-year-old fossil. True to his word, Russ Paul was sending the fossil home. Moved up the trail 150 feet from the parking lot by a massive excavator, the fossil now sits ready to receive visitors.

Forest benefits from the handiwork of master trail and bridge builder Russ Pfeiffer-Hoyt. Combining technical expertise and a relentless aesthetic eye, Russ builds trails not just to get from one place to another but to enhance the experience of the natural world by those who walk those trails. His expertise is evident in the Russ-built trail that wanders through the ancient forest and emerges on a ridge with an all-of-a-sudden expansive view of Mt. Baker. With help from Eric Carrabba, Russ also built a 50-foot bridge spanning Canyon Creek, where it enters the lake.

WLT conservation plans for the Community Forest called for the road leading from Canyon Lake up to and along the ridge above the old-growth forest to be converted into a foot trail. The project meant the removal of culverts from seven stream crossings and replacing them with bridges. To cover the expense of removal and construction, in October 1999, the Land Trust put out a call to business and individual supporters

with an opportunity to “buy a bridge.” The response was quick and enthusiastic. In short order, REI, Morse Distribution Company, Tasco Refinery, Brett & Daugert Law Firm, The Bellingham Herald, and two individual supporters bought bridges. Russ Pfeiffer-Hoyt and Eric Carrabba built them, aided by Russ’s daughter Karen.

I had dreamed about protecting the ancient forest for five years when someone finally asked me, “Why in your heart do you really want to preserve this forest?”

I knew and believed all the right answers–biodiversity, endangered species, natural heritage, future generations, water quality–but these are not the reasons that convinced my heart. Instead, as I reflected, two reasons took shape. The first had to do with awe and humility. When we stand in the presence of thousandyear-old yellow cedar trees and eighthundred-year-old mountain hemlocks, we know that there is something more significant, enduring, whole, and harmo-

nious than we are. We can experience a new understanding of our relationship to other living things, of our place in the scheme of things.

As expressed by my young daughter, the Community Forest reminds one of the ancient cathedrals of Europe—the soaring space, the mottled light, the smell of antiquity, the connection to the past, the promise of the future, the shared experience across generations looking for something greater than ourselves. We use the same word: Sanctuary for the cathedral and the nature reserve. A space inviolate.

Having an ethical relationship with someone means having a special respect for them and a special obligation of care. We see this most readily in our relationships with family and friends. As Aldo Leopold observed, ethical relationships can also extend to other living things. From the moment we walk into the ancient forest, we can feel an intense respect and an obligation, not just to refrain from

“The whole package was fantastic. Whales...glorious wilder ness areas, glacier s, bear s, rainbows and water falls!”

Marie D - Bellingham Alaska 2018

harming the forest but to protect and care for it. Anything that has lived for a thousand years possesses a moral imperative to be left alone. Nature has proven her abilities and wisdom here and only incredible arrogance could lead to disturbing this forest.

Landreth

Landreth

with crystal-like snowflakes and limber branches hung with lichen and mosses that catch, hold, and then slowly release the rain and rushing streams that seem to laugh as they burble by. This enchanting world is my muse. A stream always draws me close. I seek her essence and energy until I feel as if I am just beginning to find her face, her eyes, cheeks, and lips; then—with a click—we kiss.

Clockwise from upper left: Liquid Diamonds, There is No Holding Back, Birth, Primal Pleasure

A second heartfelt reason for protecting the forest has to do with community. This is a community forest. Jointly owned by Whatcom County and Western Washington University and protected by a conservation easement held by WLT, the community forest provides opportunities for public recreation, environmental education, and scientific research. It also offers an opportunity for us as a community to grow in our understanding of our stewardship responsibilities.

Like the cathedrals of Europe and the village Commons of New England, the community forest is a shared space. It can help give us a sense of shared meaning and common purpose. Moreover, a community forest growing when Leif Erikson set foot on our shores may give us a clearer focus as we look to the future.

The Canyon Lake Community Forest opened to the public in 2001. Its 2,266 acres include a 7.5-mile roundtrip trail through an ancient forest that ends on a ridge with gorgeous views of Mt. Baker and a 2-mile loop trail around a 45-acre lake sporting wild cutthroat trout. These fish make their way from the Nooksack Middle Fork three miles up Canyon Creek to the lake (and maybe beyond). Camping, fires, pets, motorized vehicles, and bikes are prohibited.

But there is one major problem. In 2017, a major slide closed the access road to the Community Forest. Clearing the slide would be very expensive, and engineers say that the area where the slide occurred is unstable, and the blockage could reoccur at any time. However, an alternative public access route crosses a half-mile stretch of a Sierra Pacific (not to be confused with Crown Pacific, now out of business) forest road. County Parks has tried unsuccessfully for

years to negotiate an easement across the Sierra Pacific Road to regain access. Recent events give some promise that the unexpected obstacle may soon be removed.

It is the 25th anniversary of our community assuming responsibility for

the Canyon Lake Community Forest. The trees—Alaska yellow cedar, mountain hemlock, and Pacific silver fir—are all a little bit older. After a five-year hiatus because of the access dispute with Sierra Pacific, we have high hopes that the public will again have access to its

I have directed county staff to prioritize engagement with Sierra Pacific Industries (SPI) to restore public access to Canyon Lake Community Forest. This is a very unique place, and it’s important that residents and visitors of Whatcom County be able to experience the magic of this ancient forest.

We are actively negotiating with SPI, and our respective legal counsels are reviewing draft easements that would allow the public to cross private logging roads to get to the trailhead and enjoy all that the park has to offer. Unfortunately, I cannot provide a more definitive timeline than “as soon as possible.”

I anticipate that there will be some costs related to the easements and associated road maintenance. This means that our timeline will need to factor in discussions with County Council regarding a budget allocation. I share the public’s frustration that this process has taken so long, but I’ve seen meaningful progress in recent months. I am committed to seeing this through and look forward to a re-opening celebration in the not-too-distant future!

Satpal Sidhu is Whatcom County Executive.

Community Forest during the coming summer through the intervention of County Executive Satpal Sidhu.

Happy Anniversary.

For more info on membership or these upcoming events:

Here in the northeastern reaches of Puget Sound—a maze of backwaters, island eddies, and tidal surges—the waves aren’t typically much to write home about. Here the Pacific’s rhythmic throb and vociferous surge are reduced to a primarily gentle undulation and the raw barreling southerlies of spring don’t amount to waves reaching much higher than your knees. If you’re lucky.

But adorned in a wetsuit, I’m wading

I’m here to learn the ropes with instructors Riley and Ethan, a pair of wing foiling pros. Like the best instructors, they combine a passionate zeal for speed with patience for newbies like me. Sure, I’ve puttered around on a paddleboard, but this is something else again. The board looks like a truncated surfboard, but below the waterline is a hydrofoil, a space-age sickle of carbon fiber that provides lift akin to an airplane wing. And once up to speed, the hydrofoil lifts the board and rider to fly over the whitecaps. Stripped down, this wind sport re-

the Bellingham Kite Paddle Surf showroom, gawking at the multipaneled canopies of kites and hulls of recreational watercraft lining the walls. Still, something about the foils catches my eye: an intriguing combination of muscle and magic.

Short for hydrofoils, foils are shallow wings suspended beneath a board to generate lift. The technology has been around for a while (amazingly, Alexander Graham Bell had a hand in developing the hydrofoil concept in the early years of the 20th century), but it truly hit its stride during the 2013 America’s Cup races when Team New Zealand debuted a hydrofoil boat that would set a new standard for speed. Since then, surfers, stand-up paddleboarders, wakeboarders, and kitesurfers have adopted—and adapted—the technology.

But in winging, the foil has achieved a “wow factor” that transcends the other applications, fulfilling our hardwrought desire to wring every ounce of

‘stoke’ from the technology. Make no mistake: wing foiling is an equipmentintensive sport, but since its move into the mainstream in the late 2010s, it has grown in popularity yearly.

The beauty of foiling lies in its ability to capitalize on tiny swells, Riley tells me. While the transition from floating to flying can be a little tricky, he says, once you cut loose, you can power around almost entirely independent of wave power, aligning yourself with the wind. As a result, even areas like Bellingham Bay that receive little in surfable waves can be wing foiled with ease.

Before we depart, I ask Riley about the new-found popularity of wing foiling. He explains that wing-

just about the bleeding edge. But even these are constantly being tweaked and fine-tuned.

While all of this tech doesn’t come cheap, wind is about as free as you can get when it comes to a power source.

balancing between the board and the wing, juggling each before losing equilibrium and taking the inevitable dunk.

I wash into shore, shake brine out of my ears, and try again. Riley suggests pivoting my hips in the direction I’m heading and holding the wing overhead at a different angle. I paddle out, mount the board, and pull the wing into power. Swaying to my feet, another gust tugs me along when the wing catches. It has the familiar taste of every sport I’ve ever fallen in love with.

Back on the beach, Riley leads me to a rocky point to get acquainted with the other half of the equation: the wing. The winds blow 20 knots, and even inflating the wing is a lesson in keeping a leash on almost everything. But once set up, the full span lofts and is easily controlled by the handles slung beneath it.

Stepping into the bay, I’m quickly flung across the board and wrestling with the wing to get it broadside to the breeze. Once on my knees, the wing pulls me along until I cut a neat wake. A few more puffs, and I’m up on my feet,

As I flounder around the shallows, Ethan catches a stiff breeze beneath his wing and pumps his board onto the foil, quickly accelerating as he breaks surface tension. Then, above the chop, he glides out into the bay, occasionally tacking and letting the wing depower entirely and flutter beside him as he rides the ankle biters back into shore. I watch with a kind of breathless reverence as he flies across the water, the embodiment of unfettered kinetic freedom.

Wing foiling harnesses the elemental forces of wind and water and combines these with finely tuned engineering and space-age materials: a marriage of extremes. This yin and yang combine to create the circumstances under which we can realize an ancient dream that has stirred in humanity for eons, a dream both primitive and transcendent. The dream to fly.

F eaturing documentaries, multimedia presentations and sportsrelated workshops, the Mountain Film Festival coincides with the Mount Baker Ultramarathon, which starts and ends in Concrete’s Historic Town Center. Attendees can enjoy films and presentations in the 100-year-old Concrete Theatre, live music, beer garden, and other activities in Concrete’s historic Town Center!

The Wind River Range of Wyoming is a destination nearly every backcountry enthusiast dreams of visiting. This spectacular section of the northern Rockies boasts 40 granitic peaks over 13,000 feet high, the largest glacier in the American Rockies, and over 1300 named lakes. While not as well-known as other destinations such as Grand Teton and Glacier National Parks, the ‘Winds’ nonetheless attract an increasing number of backpackers, climbers, hunters, and fishermen.

While popular destinations in the Winds, like Cirque of the Towers, Island Lake, and Titcomb Basin, see the bulk of the visitors, much of the Winds— spread over three wilderness areas— remain nearly deserted. An extensive network of trails and routes gives access to almost every corner of the range. And since most of the terrain is at or above timberline, crosscountry exploration is relatively straightforward. My first visit to these magical mountains was in 2002, and I’ve been returning to see more of the range ever since.

Something I’ve come to appreciate from all my trips to the Winds is the social nature of the area. Unlike hiking on crowded trails near large urban areas, hikers in the Winds are generally more friendly and open. These days it seems like pulling teeth to have someone respond to or even acknowledge a casual

hello on a trail encounter. However, in the Winds, it’s a regular thing for parties to stop along the trail and strike up a conversation.

The Winds can be divided into several sections: north, central, south, west,

part of this area is within the Wind River Reservation, the seventh-largest Indian reservation in the country. Home to the Eastern Shoshone and the Northern Arapaho tribes, it occupies more than 2.2 million acres. All visitors are required to have special permits, and access roads and trails may receive less maintenance.

The northern section contains some of the more difficult cross-country travel and the bulk of the Wind’s glaciers. The central section sees the fewest visitors but is no less interesting. The southern section includes the famous Cirque of the Towers, with some of North America’s finest and most soughtafter climbing routes. There are endless great places to visit in this range, but hikers planning their first trip can’t go wrong with either Island Lake/Titcomb Basin or Cirque of the Towers. Both destinations offer sublime landscapes where the hiker will find sparkling lakes, soaring granite peaks over 12,000 feet high, great camping, and well-maintained trails.

and east. Trails on the western side start higher and give access to some of the more popular destinations, such as Green River Lakes, Island Lake, Titcomb Basin, and Cirque of the Towers.

Trails on the eastern side start lower and are generally longer and more remote.

An important consideration for planning trips in this part of the range is that a large

Strong hikers can make a backpacking trip into Island Lake/Titcomb Basin in as little as three days. However, that leaves little time to explore this large area leisurely; better to plan for a bare minimum of four days, or ideally six. My most recent trip there lasted nine days, and I wished I had more time!

It’s about a twelve-mile hike to Island Lake from the Elkhart/Pole Creek Trailhead. Many parties use

Island Lake as a base camp and then explore Titcomb Basin and surrounding areas on day hikes. But if you have extra time, there is outstanding camping throughout Titcomb Basin and the adjacent Indian Basin. In addition, those with the requisite skills can add a non-technical climb of 13,735’ Fremont Peak to their itinerary.

The next must-see location in the Winds is the Cirque of the Towers. Set in the southern part of the range, the Cirque features monumental granite spires with a pristine lake at their feet to perfectly mirror the dramatic scene. Strong hikers can make this trip in two days, but again that leaves no time to relax and explore. Four to six days would be ideal.

The hike from the Big Sandy Trailhead to Lonesome Lake in the Cirque is about nine miles. The route is a bit deceiving since the first six miles to Big Sandy Lake are very easy with minimal elevation gain. However, from Big Sandy Lake, over Jackass Pass, and then down

into the Cirque, is a different story. It’s a stiff climb to the pass over some rough terrain which can be grueling in the heat of the day. Spending the first night at Big Sandy Lake lets you get an early start up the pass in the cool of the morning. Plus,

scale the big walls.

If you can add several extra days to your trip, head to nearby Deep Lake. Retrace your steps down to Big Sandy Lake and find the trail on the marshy east side of the lake. You’ll be rewarded with hiking over huge granite slabs and spectacular views of East Temple and Temple Peaks. Be sure you arrive early since there are few suitable spots to set up a tent.

For lovers of wild mountain country and wide-open spaces, a pilgrimage to the Wind River Range absolutely belongs on the bucket list. It’s an immense place large enough for big dreams, a truly dramatic western landscape writ large.

you’ll get the first pick of campsites near the lake.

Lonesome Lake makes an excellent base for exploring the Cirque. Don’t miss hiking into the upper basin of the cirque, where you’ll find meadows, mirror-like ponds, and a waterfall cascading over a smooth granite ledge.

It’s also a great place to watch climbers

For the hiker/backpacker planning a trip to the Winds, several important things must be considered. Firstly, the Winds are not known for day hiking. Most of the more popular destinations are multi-day backpacking trips. Nearly all the dramatic scenery lies among the

peaks straddling the Continental Divide. Often reaching those areas requires a hike of ten miles or more, which puts them out of reach for most day hikers.

The elevation change while hiking can be a bit deceiving for first-time visitors, especially those from the Pacific Northwest. For example, the trailhead to Island Lake and Titcomb Basin is at 9300’, while Island Lake sits at around 10,400’. At first glance, the hike should entail an easy and pleasant grade with minimal elevation gain along the 12-mile length of the trail. Wrong! Although the trail is very pleasant and relatively easy, when tabulating all the numerous ups and downs, a hiker will gain 2600’ and lose 1600’ along the way. Unlike the endless and straightforward switchbacks in the North Cascades, trails in the Winds are more like a roller coaster. But take heart, since you start nearly at the tree line, good views will be with you nearly all the way!

The proper timing of a trip to the Winds is another essential consideration. Despite being situated around 10,000 feet, most trails become snowfree by early to mid-July. However,

planning an early-season trip has its drawbacks. The Winds are notorious for

climbers must be conscious of their exposure factors. August and September are prime months for hiking in the Winds (although August may see the plague of mosquitoes replaced by humans). September sees more stable weather patterns and thinner crowds. However, one can expect colder temperatures and possible snow during the second half of the month.

Another consideration for the hiker is wildlife. Yes, there are bears in the Winds, including grizzlies, but most of the sightings have been in remote areas of the northern section. That said, using either bearproof canisters or hanging food is a must. Rangers regularly patrol trails and popular destinations and will ticket violators. But in the Winds, the most feared animal is the dreaded squirrel. These cute little creatures are notorious for ripping into packs and tents to get at any crumb of food you have. Hang or stow it in a canister, or they WILL get at it!

their populations of voracious mosquitoes and other flying insects, and July is their favorite month to harass hikers. July is also when severe lightning and rainstorms arrive like clockwork in the afternoon. Therefore, mountaineers and

One important thing to remember if you plan a trip to either location described above or any other popular destination is that arriving at your camping area early in the day is essential. The best (or all) the sites around Island

Lake and the Cirque will most likely be filled by early afternoon. Late-arriving hikers are forced to camp in extremely marginal spots, and some resort to illegal camping (again, the rangers are omnipresent). Everywhere in the Winds, there is a strict policy of no camping within 200 feet of lakes and trails. And no camping is allowed within 1/4 mile of Lonesome Lake in the Cirque.

Lastly, in an age where permits, lotteries, and reservations are needed

nearly everywhere, the Winds are an exception. As of 2022, no permits were required for day hikes, overnight trips, or trailhead parking (except for the Wind River Reservation), just a good old-fashioned registration kiosk at the trailheads. To help keep it this way, please exercise good judgment and practice rigorous ‘Leave No Trace’ principles on your trip.

EnjoyFairhaven.com

May 28: Fairhaven Festival

June 17: Chicken Festival

Every Saturday, June 24 – Aug 26: Summer Outdoor Movie Series

Bellingham’s Steve Avila loves being of service. The owner of two local businesses (Fitness Evolution and Overhead Door Company), Avila is not one to complain about things. He’s a born problem solver who–rather than gripe–finds a way to pitch in when help is needed. And on top of that, he’s a master at inspiring others to join him. When the Nooksack River flooded in November 2021, during the dark days of the pandemic, he decided it was time to step up. He launched an organization of volunteers entitled Whatcom CityZen, offering aid to families affected by the flooding. The new organization’s goal was to “create a culture of service and compassion,

Can you describe what Whatcom CityZen is about?

We are a group of passionate individuals dedicated to making a positive impact in our community. We believe that everyone should have the opportunity to contribute to the betterment of our community, and that’s why we provide volunteer opportunities that promote meaningful engagement and foster a sense of belonging. Our volunteer organization offers a variety of services such as crime prevention, litter pickup, graffiti removal, food drives, adopt-a-family events, and many other activities that involve helping others. We have weekly events that are structured in small time slots so that it is easy and convenient for everyone to participate. We are committed to providing quality services that improve the lives of those

where everyone is respected and valued, and where our collective efforts make a positive and lasting impact.”

Whatcom CityZen has also made its presence felt at local trailheads, where “smash and grab” car break-ins have become a problem in recent years. The group organized volunteers to take turns monitoring trailhead parking lots, drastically reducing these incidents.

Impressed by Avilla’s ethos, we wanted to know more, and what we learned in a deep-dive Q&A only inspired us further. His altruistic “can do” approach is truly a breath of fresh air at a time when we need all the fresh air we can get.

county, I figured that something needed to be done to bring people together. Helping others is always a great way to rally and make people feel good. Nothing gets people motivated more than having a purpose that makes them feel good and enhances self-value through the happiness that comes from helping others.

When did you launch this effort?

in need and create a more vibrant, safe, and healthy community.

What prompted you to start Whatcom CityZen?

During the pandemic times, when I saw the increase in crime, litter, graffiti, polarizing viewpoints, and a decrease in overall well-being in our

At the end of 2021, when the flood happened, I did a rally for the flood victims. It was amazing how many people stepped up to help the 54 families we adopted.

Any thoughts on why ‘smash and grabs’ at trailheads have become such a problem in recent years?

There are a number of possible factors that could be contributing to the increase in smash-and-grab thefts at

trailheads. One possible explanation is simply that more people are using trailheads for outdoor recreation, which means there are more potential targets for thieves. In addition, trailheads are often located in secluded areas, making them prime targets for criminals looking for easy targets with minimal risk of being caught. Another possible factor is the rise of social media, making it easier for thieves to identify popular trailheads and target vehicles parked there. Finally, the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic may have contributed to the increase in thefts, as people may be more desperate for cash or other valuables. Regardless of the reasons behind the rise in trailhead thefts, it’s clear that this problem needs to be addressed to keep community members safe and secure. The recent escalation may also result from law changes during the pandemic, reducing consequences for these actions. I think we can all learn a lesson from the events of the last few years and draw

some wisdom from them. “Acceptance” is a word that I feel compliments “purpose” in that you need to accept when you make a wrong decision and own up to it and fix it. You also need to accept that things beyond your control may happen, and you can only change what’s within your wheelhouse. The purpose behind CityZen is that although you cannot always change things from the top down, you can certainly influence the changes in your immediate neighborhood. If you focus on that simple task, then others will join, and you will start to affect the world around you in a positive way. If each neighborhood adopted these principles, the world would change.

At what trailheads is CityZen a presence?