Saturna Sustainable Bond Fund ( Ticker: SEBFX)

The first global fixed-income, integrated ESG mutual fund.

Saturna Sustainable Equity Fund ( Ticker: SEEFX)

A global equity, integrated ESG mutual fund.

Learn more about our unique approach: www.saturnasustainable.com

Please consider an investment’s objectives, risks, charges and expenses carefully before investing. For this and other important information about the Saturna Sustainable Bond Fund, please obtain and carefully read a free prospectus or summary prospectus from www.saturna.com or by calling toll-free 1-800-728-8762.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. Generally, an investment that offers a higher potential return will have a higher risk of loss. Stock prices fluctuate, sometimes quickly and significantly, for a broad range of reasons that may affect individual companies, industries, or sectors. When interest rates rise, bond prices fall. When interest rates fall, bond prices go up. A bond fund’s price will typically follow the same pattern. Investments in high-yield securities can be speculative in nature. High-yield bonds may have low or no ratings, and may be considered “junk bonds.” Investing in foreign securities involves risks not typically associated directly with investing in US securities. These risks include currency and market fluctuations, and political or social instability. The risks of foreign investing are generally magnified in the smaller and more volatile securities markets of the developing world.

The Saturna Sustainable Funds limit the securities they purchase to those consistent with sustainable principles. This limits opportunities and may affect performance.

Distributor: Saturna Brokerage Services, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Saturna Capital Corporation, investment adviser to the Saturna Sustainable Funds. Saturna Capital proudly sponsors occasional events and programs at the Whatcom Museum, but is otherwise unaffiliated with the Museum and the City of Bellingham.

The Lightcatcher Building at the Whatcom Museum, located in Bellingham, WA, is the rst museum in Washington State to meet LEED Silver-Level speci cations.

The Lightcatcher Building at the Whatcom Museum, located in Bellingham, WA, is the rst museum in Washington State to meet LEED Silver-Level speci cations.

Since 1967 LFS Marine & Outdoor has served the Pacific Northwest community. Now, with several stores in Western Washington and Alaska, LFS maintains its roots in Whatcom County with our flagship store and corporate office at Squa licum Harbor in Bellingham. The secret to our 50+ year success story has been dependable and reliable service through the most challenging times. We understand that our customers rely on us to help them navigate a successful boating and outdoor experience. That is why we’re here for you, and that is why we’re here to stay.

August Allen is presently less engaged in high-latitude science support and more involved in full-time father hood.

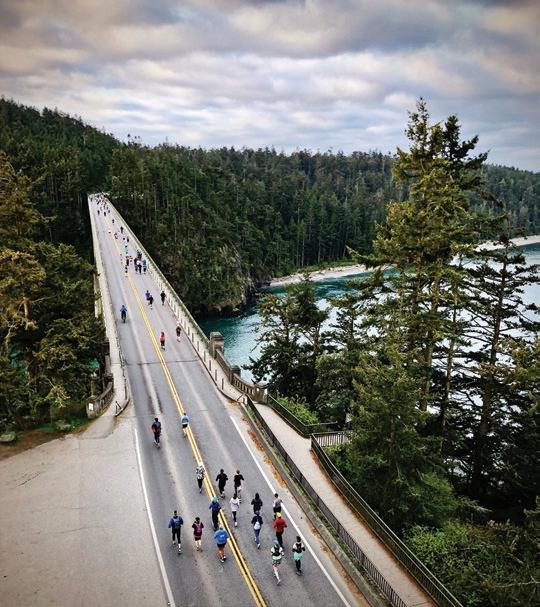

Abram Dickerson is the owner/principal at Aspire Ad venture Running. As a husband, father, and entrepreneur, he attempts to live his life with in tention and purpose. He loves mountains and the friendships that result from the suffering and satisfaction of running, ski ing, and climbing in wild places.

Jason Hummel is an outdoor adventure photographer based in Gig Harbor. He’s currently working to ski every named gla cier in Washington State. You can find his stories and imagery at Jasonhummelphotography. com

For 40 years Rand Jack has worked to conserve land. He loves animals, trees, and grand kids. He carves birds, bringing wood and animals together. He is on record as the oldest per son ever to climb a strangler fig from the inside in Costa Rica.

Rob Lyons is a free-lance adven ture journalist who divides his time between the wilderness seacoast of British Columbia, the high deserts of the Northwest, and the lakes and streams of the North Cascades. He lives with his artist wife, Pamela, in the San Juan Islands, along the coast of Washington.

Tim McNulty is a poet, essayist, and natural history writer. He is the author of three poetry collections: Ascendance, In Blue Mountain Dusk, and Pawtracks, and eleven books on natural history, including Olym pic National Park, A Natural History, which won the Washington State Book Award. Vis it him at www.timmcnultypoet.com.

Jason Griffith is a fisheries biologist who now spends more time catch ing up on emails than catching fish. Regardless, he’d actually prefer to be in the mountains with friends and family. Jason lives in Mt. Vernon with his wife and two boys.

Dawn Groves is a Bellingham writer who loves the great white north. She also kayaks during warmer months.

Bill Hoke came to the Pacific Northwest in 1970 and began a lifetime of climbing and hik ing. He’s hiked—mostly solo— more than 1,500 miles in the Olympic Mountains and is the editor of the fourth edition of the Olympic Mountains Trail Guide for Mountaineers Books.

Frank James has had the great good fortune to fly to work from Bellingham to the San Juan Islands for nearly 30 years. These flights are usually early in the morn ing and in early evening near sundown, affording copious opportunities to capture the astounding light on the mountains and water with his camera. His day job is doing re search, teaching, and practicing medicine locally and globally.

James Williamson attended fine art and graphic art classes at Northern Michigan and Western Washington University after serving as a graphic illus trator in the US Air Force. He is committed to creating memo rable images of historical and contemporary maritime subjects, as well as land scape and wildlife themes. See his work at What com Art Market and James-Williamson.pixels.com.

The heartbeat of Cascadia 9 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

The heartbeat of Cascadia 9 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

an hour sitting beside a mossy creek on a comfortable rock among the ferns and shadows of the for est, listening to the water music and the wind moving in the branches overhead. I found myself counting my blessings.

Gratitude, it seems to me, is at the heart of a happy life, but so often, we lose sight of all that we have to be grateful for amid the cacophony of bad news, stress, and a constant stream of challenges, both real and imagined. As a species, we’re wired to focus on threats, a vestigial trait dating back to our “eat or be eaten” distant past. While undeniably useful when large predators roamed through the darkness, this hypervigilance has become, for many of us, an obstacle to recognizing benevolence in the world around us.

There on that rock, I spent a few minutes considering my good fortune, making a mental list of the many things I am grateful for: family and friends, fellow travelers on this long,

strange journey around the sun, the wonderful community I am a part of, so many people engaged in making the world a better place and enjoying the process.

I’m grateful to live amid such beauty—after more than 30 years of calling Cascadia home, I remain enraptured and enthralled by the splendor of our luminous landscapes. And I’m indescribably grateful for my work organizing this magazine four times a year, collaborating with a constantly growing cadre of creative spirits—inspiring writers and visionary artists—that bring countless ex pressions of authentic joy to life in its pages.

Times may be challenging in this country (and the world), and there is no shortage of things to worry about, but while sit ting on a rock watching the clouds dance overhead on a bright, early-winter afternoon, I found myself awash in gratitude.

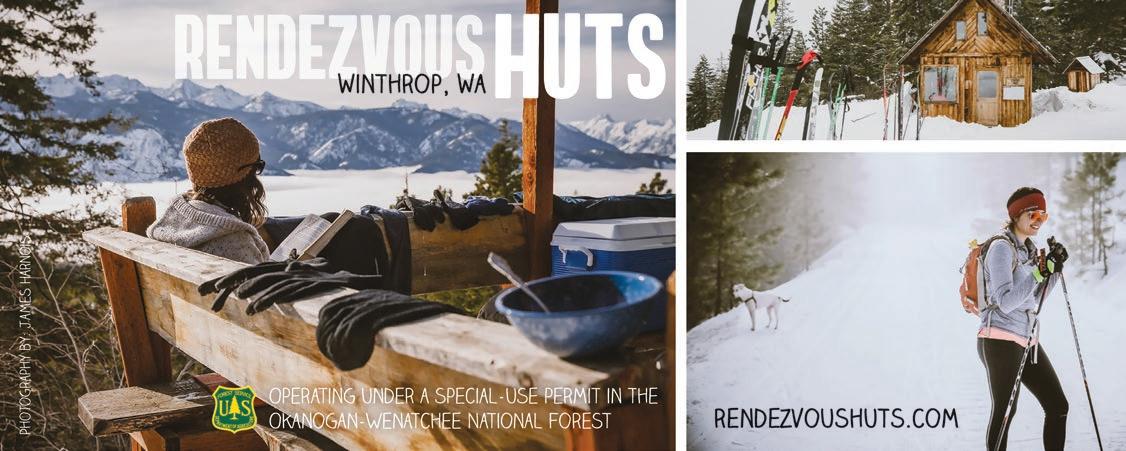

Boasting North America’s largest ski trail network, the Methow Valley is justifiably famous as a Nordic ski destination. Lots of snow and sun entice skinny ski enthusiasts from around the country (and the world) to kick and glide through winter landscapes that are ideally suited for anything from a relaxing tour along the Methow River to challenging backcountry explorations in the surrounding mountains. Now in its fifth year, the annual Ski to the Sun Marathon and Relay, held this winter on February 11, has become the centerpiece of the Valley’s ski season. Skiers climb from the tranquil banks of the river to the beautiful mountain vistas at Sun Mountain Lodge.

Begun as a spinoff of the Methow’s iconic summer running event, The Sunflower Trail Marathon, Ski to the Sun was created as both an inclusive and a competitive event, attracting first-time Nordic ski racers as well as expert skiers. “We were thrilled to see such a wide variety of experience levels at our first Ski to the Sun and knew we were onto something good,” explains Methow Trails Program Manager/Event Director Adrienne Schaefer.

The Marathon can be skied by individuals or teams with up to five

other friends or family members, according to Schaefer. “We also have a para-Nordic category and had three sit-skiers and one visually impaired skier at last year’s event,” Racers warm up with a fast-paced ski on the valley floor and end with an exhilarating climb to the top of Sun Mountain, where 360-degree vistas and delicious, hot food await. “The marathon is a community event,” Schaefer says, “with over 150 volunteers cheering everyone along the way.” The post-race party features food from local growers, Willowbrook Farms; an Old Schoolhouse Brewery beer garden; raffle prizes donated by the event’s sponsors; and an awards ceremony.

“We’re excited to have an event that our community supports, and that appeals to a wide variety of skiers,” says Schaefer, “Olympic competitors, kiddos in tutus, sit skiers, and people who have never done a ski race before.”

More info: www.methowtrails.org

Apreviously unnamed 6,480-foot peak in the Twin Sisters Range now bears the name Kloke Peak in honor of Dallas Kloke, a renowned local climber credited with the first ascent of the peak in 1972. Kloke died in a climbing accident in 2010 on the Pleiades in the North Cascades.

Jason Griffith, a Skagit County-based climber, spearheaded the effort to name the peak in Kloke’s honor. “Dallas was an important member of the local climbing community, responsible for guidebooks and many first ascents,” Griffith explains. “We— his friends and family—figured it was the least we could do to honor his legacy.”

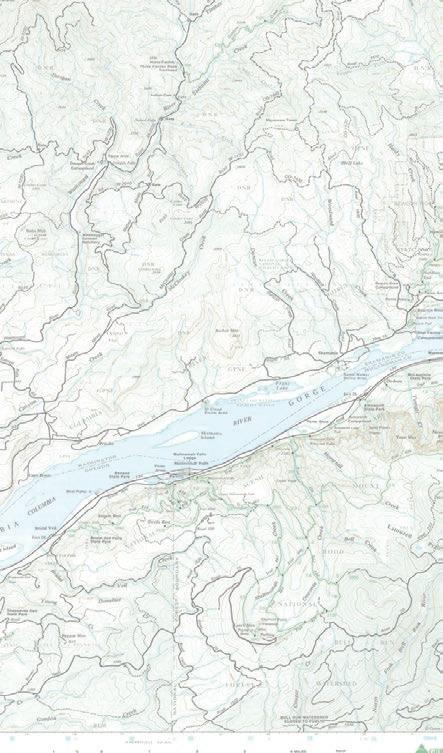

The process of naming the peak after Kloke required persistence and determination on the part of Griffith. In 2020, he filled out a Geographic Name Application Packet, gathered letters of support and other exhibits supporting the proposal, and submitted it to the Department of Natural Resources. After two hearings, the application was forwarded to the State Board on Geographic Names, where it was approved, then sent to the US Board on Geographic Names. “This is where Kloke Peak is now,” Griffith says. “State approved, awaiting federal approval. But typically, anything that passes at the state level gets Federal approval. This step means that it will show up on digital USGS maps going forward.”

Griffith explains that he and Kloke were close. “Dallas was a friend, climbing partner, and mentor to me…almost a father figure. But at the same time, he had the irrepressible energy of someone a quarter of his age. His enthusiasm for the mountains was infectious.”

Kloke was born in Burlington, WA, in 1939. In addition to climbing, he taught school in Oak Harbor for 33 years and later lived in Anacortes, where he coached cross country, wrote children’s books for friends and family, and was active in the community. Dallas and his wife Carolyn raised three children. Throughout his many years of climbing, he established numerous new routes in the North Cascades and Twin Sisters Range, where his memory will live on with the naming of Kloke Peak.

After an extended COVID-mandated closure, the trail to Shi Shi Beach is open again, and you’d be hard-pressed to find a more beautiful spot along the Olympic Coast. Passing through Makah Lands to Olympic National Park, the going is easy through the coastal rainforest (if you don’t mind mud), and the curving stretch of sand at its end is Pacific Nirvana. If possible, time your visit with a low tide and explore the magnificent Point of Arches to the south, where urchins and starfish congregate in technicolor tide pools. Campsites are found near Petroleum Creek (bring a bear can). Roundtrip to the Point of Arches is eight miles. You’ll need an NPS permit (available in Port Angeles or online) and a Makah Recreation Pass, which you can procure at various locations in Neah Bay.

Trailhead: Hobuck Road on the Makah Reservation, southwest of Neah Bay. Paid over night parking is available at private residences about a half mile before the trailhead.

Is this the snowshoe (or cross-country ski) route that deliv ers the biggest bang for your buck in North America? Head up to Huntoon Point on a clear winter’s day and answer the question yourself. Starting in the hustle and bustle of the Mt. Baker Ski Area, you’ll climb into the realm of the Mountain Gods—Shuksan and Baker—and enjoy views that rival any in the Alps. Roundtrip to this 5200-foot promontory representing the high point of Kulshan Ridge is only six miles and 1200 feet of elevation gain. Of course, a vantage point like this means you won’t be alone, but you will most certainly be captivated by the splendor of the North Cascades.

Trailhead: Mt. Baker Ski Area upper lodge parking lot, located at the end of the Mt. Baker Highway (WA-542), about 55 miles from Bellingham.

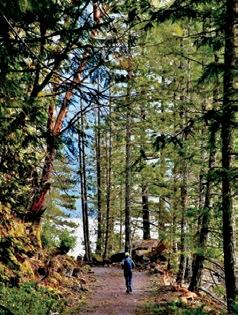

Follow an old railroad bed along the shore of sparkling Lake Whatcom for as long as you like (up to six miles roundtrip). This is an easy walk on a wide, smooth trail with almost zero eleva tion gain, an ideal choice for a mid-afternoon stroll when the benefits of the lake, old-growth trees, and an occasional water fall are just what the doctor ordered. It’s as good on a cloudy day as a sunny one, and there are numerous places where you can pause to sit at the water’s edge and contemplate how for tunate we are to have such a beautiful place to recharge one’s soul so close to town.

Trailhead: From Electric Ave. in Bellingham, take Northshore Rd. 7.2 miles east and bear left at a fork. The trailhead parking lot is .5 miles from the fork on the left.

The Mt. Baker Highway is unusual. As one of Washington’s few high mountain roads that remains (mostly) open in winter, it provides access to the alpine that otherwise just isn’t feasible in other parts of the North Cascades due to a combination of snowedin roads and the abbreviated daylight hours of winter.

The Highway, officially known as SR-542, is plowed to Mt. Baker Ski Area’s upper lodge at Heather Meadows (elevation 4300 feet), where one can find a plethora of amazing day trip options. One of the finest on offer is a mid-winter visit to Coleman Pinnacle, a volcanic crag that rises like a fang above Ptarmigan Ridge, about two and a half miles southwest of Artist Point. In recent years, Artist Point has become an extremely popular snowshoe/ ski winter destination because it is a short and relatively safe trip from the ski area. But this is just the start of the trek to Coleman Pinnacle (6,403 feet). Since it is around ten miles and several thousand-foot of elevation gain out and back, depending on the route, a visit to the Pinnacle calls for backcountry skis or a splitboard. Snowshoes would be an exercise in self-loathing (although many have done it).

But a winter trip to Ptarmigan Ridge isn’t suitable most days. The route lies mainly above treeline and is there fore exposed to storms and lacks landmarks in poor visibil ity. Traveling in blowing snow without visual cues is a recipe for a miser able and possibly unsafe day in the mountains. So, a good weather forecast is the manda tory first step (https://forecast.weather.gov/MapClick. php?zoneid=WAZ567). Also, there are concerns about avalanche conditions. What does the Northwest Avalanche

center say about hazards for the day in the Baker backcountry (https://nwac.us/

avalanche-forecast/#/west-slopes-north)? Finally, sun can be a benefit but also a curse if the snow is unstable. I’ve been out to Coleman Pinnacle

most winters for the past 15 years, and the trips share a certain pattern, even as partners and details shift. First, there is the coffee-fueled as cent on 542, catch ing up with friends, route planning, craning your neck at certain points to look at how the snow hangs in the trees, where the winds are blowing, and how perfect (or not) the snow looks. Then, the shivering prepara tions at the parking lot, bantering with kindred spirits, jumping at the booms from the ski patrol prepping the ski area with hand charges (not a good sign for backcountry snow stability). Then you’re off, gliding on the

southern edge of the ski area, always going too fast, hell-bent on getting to Artist Point as the sun illuminates Mt. Herman and Table Mountain.

On this trip, we crest the buried parking lot at Artist Point, bathed in the warm light of a winter’s morning. Kulshan domi nates the scene to the west while Shuksan’s west face and its hanging glaciers lie in shadow, wisps of snow swirling across the rocky ridgetops. A quick stop to strip skins, root around in the snow to assess stability (some avalanche training is always a good idea: https://avtraining.org/aiare-level-1/). Then some quick turns down to the south side of Table Mountain, often dodging debris from the last ava lanche cycle. We put our skins back on for the milelong traversing climb under the imposing cliffs of Table Mountain to the eastern head of Wells Creek.

Here we start to experience the freedom of a land scape transformed by the deep snows of winter. The sum mer trail hugs the top of Ptarmigan Ridge, mainly on the south side, all the way to Coleman Pinnacle. But in winter, you aren’t limited to trails, which tend to traverse and avoid elevation gain and loss. Sure, Coleman Pinnacle may be the ultimate destination, but there is skiing to be done en route! And so, we strip off our skins again for a run down into Wells Creek, followed by another ascent, another run, and another ascent, going where the snow conditions take us, zig-zagging our way to the col to the southwest of the Pinnacle.

From the base of the Pinnacle, the final 200 feet rear up at an angle that most would find a bit challenging to ski. Add to this steepness the flutings that come from snow blasting around rocks and stunted mountain hemlock, and the easy decision is to leave the skis at the col to boot the final stretch, lightweight ice axe in hand. It is always more work than it seems, post-holing into voids around hidden trees and rocks, trying to avoid the cornice that often overhangs the north side, legs heavy from the bonus vertical that gliding on skis so often encourages.

But the view! The weariness fades as we eat a late lunch, marveling at how the warm light of winter accentuates the

curves of heavy snow over the glacially sculpted landscape. Kulshan and its beautiful Park Glacier Headwall—only five miles away—dominates the western view, much more impressive than the view from the ski area. Steam can often be seen thinly rising out of the crater, a reminder that maybe the town of Glacier, located in the valley below, wasn’t built in the best location. Even with a down jacket, a chill creeps in, and a realization that winter isn’t the season

to linger. Movement is life.

Rarely, but sometimes around the windswept summit of Coleman Pinnacle, I’ve caught movement out of the corner of my eye and stood amazed at ptarmigan quietly foraging in their brilliant winter plumage. Somehow, they are able to survive in the harshest winter months at the same elevation they inhabit in the summer. How?

Contemplating a question like this is an important way of turning the mind away from the toil ahead after that first exhilarating run down the north side of the Pinnacle. Now the real work begins: to climb out of the hole of Wells creek, picking your poison based on the en ergy left in the legs, the snow conditions, time remaining before sunset, and how

psyched (or not) the party remains.

There are options for various routes back to Bagley Basin, which is one of the most attractive aspects of winter trips. In the summer, the most efficient route is typically preferred, usually a trail or the path of least resistance when in trackless terrain. But on skis, options are plentiful in winter, and the exact route is subject to a hundred variations, offering the added pleasures of minor discoveries, often enjoyable enough to negate (some of) the pain of the inevitable climbing that follows a long descent. And so, over the years, some times I’ve found myself taking a long way back to the parking lot, descend ing from the top of Table Mountain in the last rays of the sun.

There is something extraordinary about seeing both the sunrise and sunset across a gloriously sunny winter’s day. In constant movement, covering many miles of untracked snow with good friends, sometimes it all comes together in a way that is difficult to put into words. Nevertheless, there you stand in the gloaming at the bottom of Bagley Basin, the last party out, watching the sunset fade from Goat Mountain as you slowly make your way to a mostly empty park ing lot. At times like this, you can’t wait for the next time it all lines up again. It’s like a drug.

For a long time, I hated running. It held no joy. It was an exercise to do, a chore to perform. It was work, and it hurt. The best moment of a run tended to be when it was over. The value of running was a means to an end: enhanced fitness, which meant increased performance in the mountains or at least better health. But as an end unto itself, as something to be done for hours on end, no.

Enter life, a.k.a, marriage, work, children, a mortgage. All freely chosen. Each a source of joy. Each a constraint on the hours spent in the hills. Gone were the endless summer road trips; fading was the perpetual weekend warrior. Gradually the gym replaced the crag, and the dirtbag was swapped out for the diaper bag.

Unwilling to relinquish my time in the mountains, running found me. It came as an invitation: 34 miles on the Copper Ridge Loop in the North Cascades. My response: sure, how hard could it be? Turns out it was pretty hard. But it was also beautiful, freeing, invigorating, and pivotal. It changed the physical and psychological map of what moving in the mountains could be. What was once a multi-day backpacking trip became an afternoon crush. A vest replaced a heavy pack. And a couple of hours getting lost on cold, wet, dark scrappy trails satiated a fix for adventure. Running gifted me the fitness to go further and faster and saturated me with the serotonin I needed to show up as a better father and partner.

Thousands of miles later, is running still work? Yes. Is it always fun? No. The best moment of any run may still be when it’s over but running as a practice has transformed my life. The ritual, the trails, the seasons, the discipline, the pain, the suffering, the friendships, all of it is in me and flows through me as I move my body, fill my lungs, and listen to my heartbeat. Some days it’s a shuffle, sometimes a sprint, and often it’s a power hike up a long hill. Whatever form the run takes, wherever it takes me, it’s all a process and a journey, an invitation to break out of the grind and claim the time and space to be fully in control, fully in the moment, and fully in the flow. So, the next time the universe invites you to go for a run, the only answer is yes.

In the winter of 1952, when I was a little boy of five, my family sailed across the North Atlantic from Europe on a small troop ship. The storm we endured, the moun tainous seas and howling winds, and the mélange of fear and awe it generated, will forever be etched in my soul. It may have been less than the perfect storm for the captain, but for me, it was mighty impressive and the first time I realized there was a power greater than my parent’s ability to protect.

Fast forward half a century to the San Juan Islands when my wife Pamela (then girlfriend) introduced me to ocean

kayaking. For many years before she met me, she paddled the open coast of British Columbia, and had even built her own Hooper Bay sealing kayak. While I’d had years of white-water experience running McKenzie dories on the Deschutes, I was new to ocean kayaking. The summer I met her, Pamela invited me to join her and some friends for a month of kayak ing, and I said yes.

After nearly a week of paddling out a deep inlet and heading north along the open coast of Vancouver Island, we settled on a long, white beach beside a creek that tumbled out of the rain for est. We paddled out to catch our supper each day, played baseball on the beach, and dove in the sea to cool off. Around a

big fire at night, the sound of mbira and drumming kept the wild animals at bay. Gradually, we created a small neo-native village with a 30-foot longhouse made of driftwood poles and plastic tarps, plus a seaweed-chinked driftwood smokehouse to cure all the salmon we caught. It was bliss.

After a week of this I was ready to explore paradise. The urge to go off and trek along the open coast alone was compelling. By the time we made it back to our rigs at the end of the month and were driving back to civilization over the coastal mountain range, I’d made the decision. Next summer, I would set off from home and paddle around the island alone. Pamela—thankfully!—was will

ing to support me in the attempt.

On the inaugural trip with Pamela, I paddled a battle-scarred Orca kayak. I was uncomfortable in it because I was unclear on self-rescue protocol. Being fully aware of that fact, I decided that for the long and lonely kayak touring I had in mind and the little expertise I was starting with, something foolproof in the self-rescue department would be the smart move.

As a Southern California migrant with surfing experience, I could appreciate the concept: your ride was your life preserver. Just coming to the paddling scene, I could see the same logic apply ing to the sit-on-top kayak. No selfrescue tech required, other than what I would pick up from sea lions along the way, namely, how to slither back aboard should I get bucked.

I found a 20-foot Tsunami Ranger that would be perfect for the trip, a big water fiberglass ‘sit-on-top’ boat with plenty of storage. Over the winter months and into spring, I rustled up gear and or ganized supplies. A friend of mine, Craig Petersen, had paddled around Vancouver Island four years prior. His insights (and a copy of his route penciled on a chart) were invaluable.

I accumulated a dozen charts, one for each section of the coast. I had tide tables and current charts for the straits and channels. I had Ince and Kotner’s A Paddler’s Guide to the West Coast, Washburne’s A Coastal Kayaker’s Manual, and a copy of Mists of Avalon that read like ambrosia in stormy weather.

One windy afternoon in July, every thing was spread on a beach on Lopez Island. I fielded questions from local news folks and accepted good-byes from friends. The boat was stuffed to the gills. While saying farewell, Pamela promised to mail forty-pound packages of supplies to post offices at Campbell River, Port Hardy, Winter Harbour, and Tofino. An hour later, I was gone.

I watched as three gray whales steamed right at me, performing a whale ballet as they pirouetted through the water so close I could have touched them.

My plan was “learn while you earn.” I figured I’d get my sea legs paddling up the inside of the island, and by the time I reached the open sea at Cape Scott, I would be up to speed. The more challeng ing paddling was on the outside of the island with capes, wave-lashed beaches, and long rocky stretches where you could not safely get ashore.

It was high summer, and Georgia Strait was full of pleasure boats, fishing boats, military boats (conducting naval exercises), barges, cruise ships, and the ubiquitous ferries, including the big super ferries powering over to Vancouver and back.

But as I paddled north that first month my imagination soared ahead. Fifty miles to the west, to be precise, to the freedom of open water and deserted

white sand beaches. Until then, I found precious little public shore where I could take out, let alone pitch a tent, and gue rilla tactics became necessary. Finally, after Campbell River, the busyness of humanity was reduced to logging and fishing, then through congested narrows and Johnstone Strait, eventually arriving at Sayward, Port McNeill, and Alert Bay. The fishing fleet was anchored along the way, awaiting the salmon season’s opening. They were a pretty friendly bunch. One guy named Sam, who reminded me of a healthy old tree, waved me over and gave me a fish. Norwegian fishermen invited me aboard their boat, where I sat in the galley with the crew to eat enormous plates of delicious fried fish fillets and a big salad (the best part, at that point). In retrospect, these were great mid-summer, small boating adventures, but I was Jonesin’ for the outside at the time.

In Port Hardy, I spent the night sleeping on the government wharf tucked discreetly under the sliding dock ramp. After the bars shut down in the wee hours, the loud voices of a cacophony of drunken fishermen trooping down the noisy planks just above my head jolted me awake. Several equally drunk women screaming curses at the top of their lungs followed. I was happy to get underway early the next day.

Within sight of Cape Scott, I encoun tered a pod of gray whales feeding close to shore: the fifteenth of August, a little over a month since I left Lopez Island. I camped in a little bay. At dusk, a fog bank

stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

The heartbeat of Cascadiarolled in that was so thick I could only see my hand in front of my face. Sounds were dampened; the haunting tremolo of loons mixed with the fluted respiration of whales and the cadent bleating of a fog horn down at the cape made a mourn ful symphony. I crawled outside my tent to pee several times that night, having trouble sleeping, feeling both excited and anxious. Rounding the top of the island on the morrow would undoubtedly create new wrinkles in my game. The guidebook I brought billed this stretch of coast as: “. . . a challenge to even the most advanced sea kayaker.” which I certainly was not (a reality-check made on more than one sketchy occasion).

I glanced to my left as I ap proached the breakers off the rocky cape, and did a double take upon seeing a man and a woman sitting on a rocky shelf eat ing lunch. No doubt they’d hiked out to the point over Provincial Park trails. They waved, and I—an otherwise friendly, outgoing, and quick-witted per son—was too stunned to reply!

Another hundred yards and the hik ers were forgotten.

A turbulent, wave-lashed reef lay ahead where deep green swells rose to crash over rocks, tossing plumes of

bone-white foam skyward. My heart was in my mouth as I threaded through the tumult. Not realizing it at the time,

I know now that the greater part of my fear stemmed from the irrational belief that the white-water madness in front of me was chaotic and that the waves might just as well rise up to crash wher ever they wanted or even chase after me!

Dungeness crab that night.

Over the course of the journey, I ate a lot of fish. Salmon were ubiquitous, augmented by ling cod, black rock bass, quillback, and calico rockfish; all were plentiful. I trolled a fly for salmon while I traveled, and if I had no luck by the time I was ready to go ashore, I tied a lead jig on the end of my fly line and pulled up din ner. Stuck ashore in bad weather, I ate horseshoe barnacles. Unfortunately, the threat of red tide prevented me from harvesting mussels, clams, and oysters, but the “Dungies” were deli cious compensation.

I paddled into Hansen Lagoon later that day, relieved to have passed the ini tial challenge of the outer coast. At the mouth of the lagoon, I pulled out my fly fishing rod, tossed a fly along the edge of a kelp bed, and had a tremendous strike. Slamming my rod against the boat’s hull, an enormous salmon took one massive surge of line and leaped into the air, flashing silver and white, then dove into the tangle of kelp and broke my line. Ashore, I set out my breakdown crab trap and feasted on succulent

Whenever possible, I camped by creeks and st reams for fresh water. Unfortunately, it was a historically dry summer, and I occasionally had to filter water gathered from funky rock pools above the tidal zone. I carried a hand-held spinnaker sail that offered a change of pace when the winds were right. My 3-person/4-season North Face tent was reliable in the storms, even the hurricane-force winds I en countered, and it had sufficient room to provide comfort when I was forced to hunker down for two or three days in bad weather—a huge plus for my spirit. I had three fly rods and as many reels, as well as a fair bit of photographic equip ment to keep me occupied and happy. The big swell off the island’s

northern part was legendary among kayakers. Riding those twenty-foot roller coasters was quite the thrill. The most challenging conditions, though, were the reefy shoals with sunken seamounts or rocks, and I had to keep an eye out for boomers that broke from the biggest wave sets.

At Winter Harbor, I collected a box of supplies at the tiny post office. I posted dispatches for various magazines and the local newspaper. From there, it was about ten miles to Brooks Bay at the northern side of the great cape.

The British explorer Captain James Cook called Brooks Peninsula the “Cape of Storms.” The cape itself is about three miles wide and six miles long. Wind and water accelerate like crazy off the tip when conditions are right, which is most of the time. Slack is when you want to make your move.

What’s most challenging for kayakers about Brooks is Clerke Point, at the southern corner, where a reef runs a mile out to sea and makes for rapidly changing conditions. In the five circuits I’ve made of this cape to date, I’ve seen it flat calm, with elegant combers that would do Redondo Beach proud, and once, sporting some of the nastiest stuff I’ve ever seen: gnarly over-falls and rips. Twice I’ve surfed ashore at Amos Creek to wait out conditions. And once (I will never forget), while mak ing a tight dash around the reef, I watched three gray whales

The heartbeat of Cascadia 25 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

steam right at me, performing a whale ballet as they pirouetted through the wa ter so close, I could have touched them.

I made a smooth and uneventful passage this time, accompanied by a pair of orcas; it was a powerful, thrilling place to be. Once past Clerke, I made for a particular beach at the base, where I found Pamela and fifteen of her friends.

Suffice it to say; it was an enjoyable week. When it came time for them to return, I paddled with them to the Bunsbys, then Spring Island. Then it was just me again, alone with the sea.

This was an emotional nadir for me. After a serious girlfriend refresh, I came to miss Pamela very much over the weeks ahead. While the north coast had held me in thrall, I was now approaching civi lization again. I picked up my last food drop in Tofino and continued on to Barkley Sound and Cape Beal, and paddled just out past the surf along the famous West Coast Trail. I had hiked the trail once ten years earlier, slogging through mud and gazing out from under a fifty-pound pack to the water, think ing (presciently) how a little boat would be the ticket, something I could pull up on shore for the night.

With a big sou’easter moving in, I stopped at the Carmanah Lighthouse, where the gracious keeper-family of Jerry,

Janet, Jake, and Justine invited me to a Canadian Thanksgiving dinner. I was billeted in the coast guard cabin and taught the kids ‘Horse’ and ‘Around the World’ on their helipad-cum-basketball court in a bit of enjoyable international détente. It was cause for celebration for me as well—the Carmanah Light marks the entrance proper to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the broad channel that leads into Puget Sound.

After a long and exciting crossing of wind-swept Haro Strait, I surfed ashore in a nasty four-foot chop onto the spit along Fisherman’s Bay, landing on the beach that I had left precisely one hun dred and two days earlier; I would never have guessed it would take me this long!

Coming down the east coast of San

Juan Island, I could not make radio con tact with a marine operator, so Pamela had no precise idea when I would arrive. There was no one out on the beach that evening, but there was one last beer in the kayak (I never missed beer-thirty the entire time in

the field, perhaps the greatest accomplish ment of the trip), and I dug around to find it. Still in my stinking, torn wetsuit, and nearly out of food with rain clouds scudding overhead and darkness about to descend, I collapsed on the beach, leaned back against a driftwood log, and drank. Not long after, an older couple out for a stroll spotted me and called in the calvary.

Ironically, for such a solo journey, people played a big part in my experience. I was something of a curiosity, I suppose, and fishermen and lighthouse keepers made my day on more than one occasion. But, of course, I spent most of my time alone. The famil iar sense of hearth and home had been conspicuously absent. In its place were brisk winds dancing in the treetops at the forest’s edge, the boom, cough, hiss, and crack of waves, the raucous cry of gulls, and the familiar tok-tok of ravens. At night in my tent, the wind

rattled the nylon fly. In the morning, the clank of metal spoon on metal cup was the melody that filled the air as I stirred my instant coffee. And perhaps the leitmotif at the end of the long arm of

waves rise and fall when it occurred to me how a wave is really the ocean doing a wave thing. Not the form I typically take it to be. A moment later, as the other shoe dropped—the Aha —that every thing, every form, every stitch of mankind, myself included—is just like that wave.

That may sound obtuse, but for me, that simple insight, car ried forward into my zazen prac tice today, might be the ultimate takeaway.

civilization was the robotic voice on my VHF radio that I listened to many times each day to catch the latest weather intel from Environment Canada. And finally, the metaphor.

I was on the water one day watching

As I look back, the prime motivation of this trip may have been to slay demons—my deep fear of the relentless power of the sea—but I might never have done it without the accompany ing awe. I trimmed some fat off the beast, reducing it to moments where I could see fear was clearly justified—but no more imagined maleficence, at least, like the rogue waves in hot pursuit at Cape Scott. ANW

The heartbeat of Cascadia 27 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

The heartbeat of Cascadia 27 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

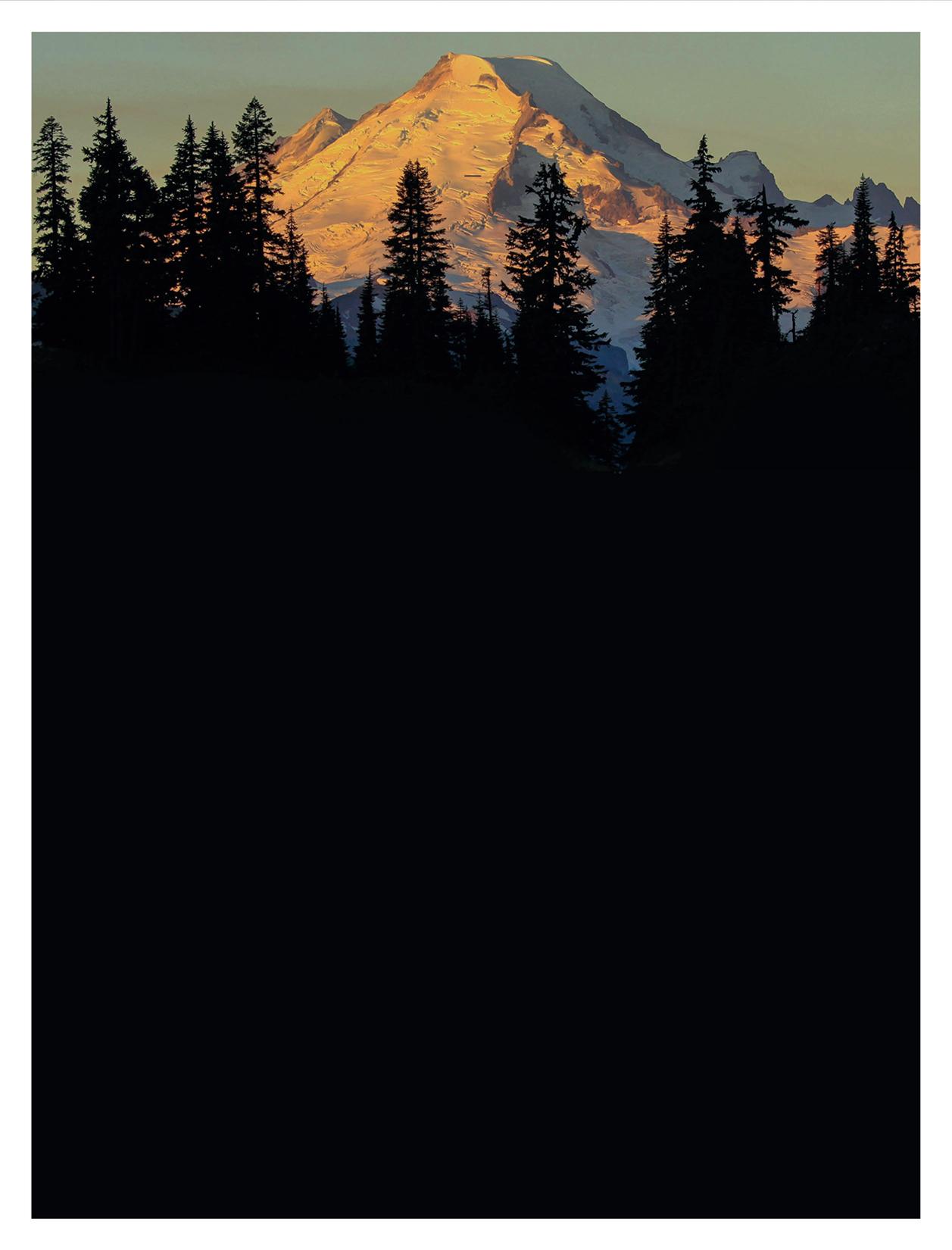

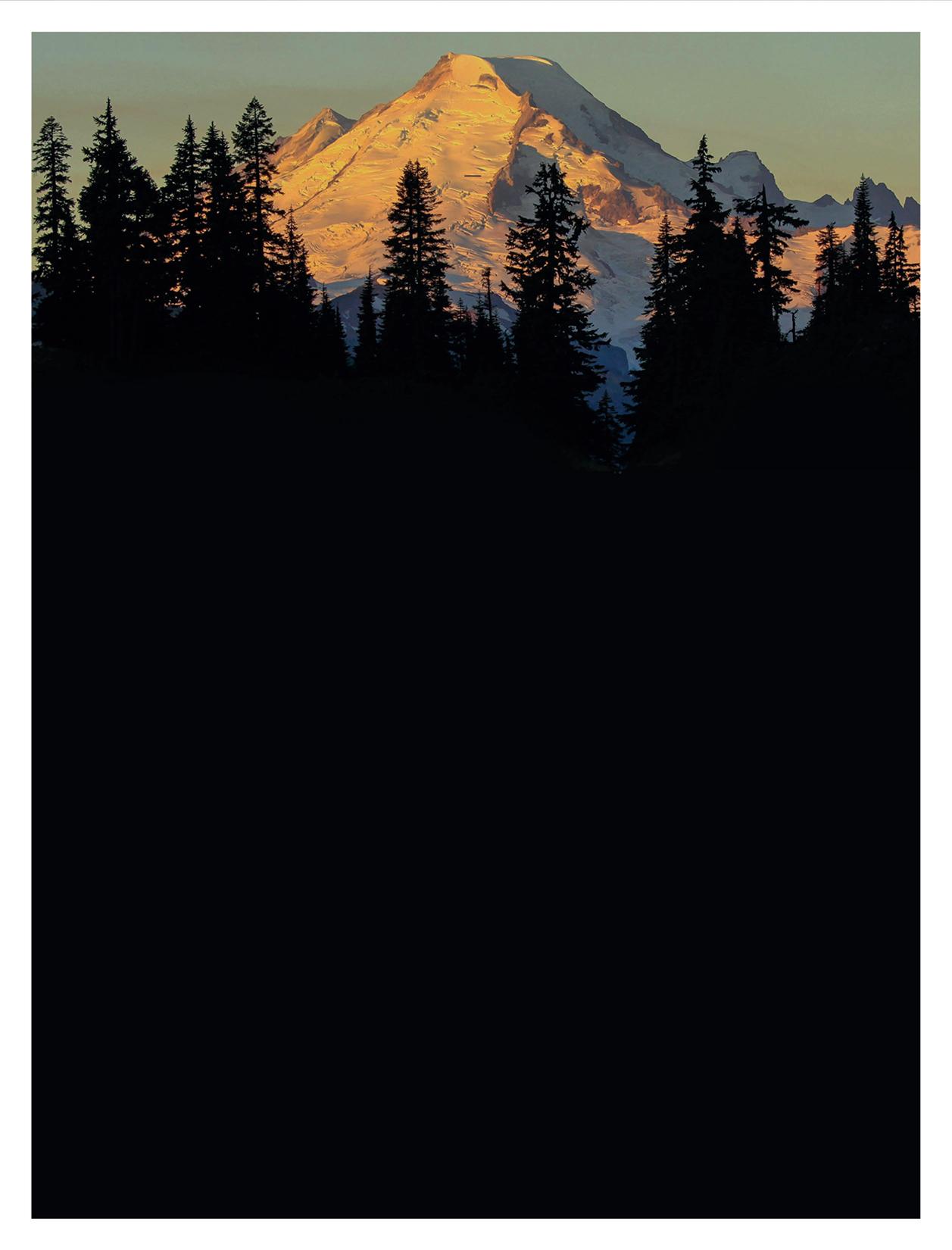

Ipush forward through days spread out over decades. Days that have taken me into nearly every corner of the Cascade Mountains where snow weighs heavy on my shoulders, just as it does on the boughs of the evergreens that groan with each additional snowflake. Days where clouds open up and my place in the world is defined. Days spent amid glaciers, waterfalls, ridges, forests, and more. Days compressed into photographs, more than a million images in my adventures to date, each of them a treasured memory found along winter’s path.

See more of Jason Hummel’s photography at jasonhummelphotography.com. Visit AdventuresNW.com to view an extended gallery of Jason Hummel’s remarkable mountain photography.

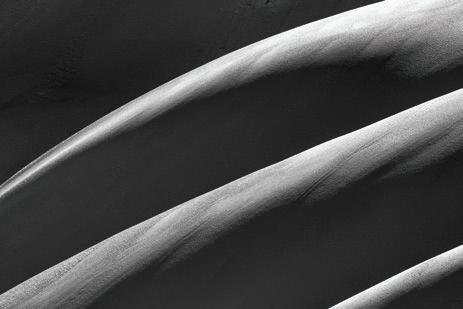

This Page (top to bottom): Sculpted slopes of light and shadow, Beams of light in the southern Cascade foot hills, The Enchantments in Mid-Winter

Next Page (clockwise from top left): Slumbering winter clouds, Howling winds on Mt. Shuksan’s North Face, Larches exposed above winter’s snow, Hanging cornices along ridgelines in the North Cascades, Devils Digit and wind-scoured trees, Mt. Baker as seen from Table Mountain

The heartbeat of Cascadia 31 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

The heartbeat of Cascadia 31 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

Alot goes through your mind while lying on the floor of a sushi restaurant in downtown Anchorage. Stuff like, “somebody needs to clean the underside of this table,” and, “why doesn’t anyone ask what I’m doing on the floor?” and, of course, “this is gonna make a great story if I live.”

Five days prior, I had flown into Anchorage, Alaska, to experience firsthand the most famous dog sled race in the world, the Iditarod. Two previ ous trips to the Yukon had fueled the desire. On the first trip, I drove a dog sled in the dead of winter (ANW Winter ‘19) and loved it. On the second trip, I helped pack 1000 pairs of dog booties and 500 pounds of frozen fish, beef, and pork into plastic drop bags for musher Michelle Philips and her upcoming

Story and Photos by Dawn GrovesIditarod effort (ANW Winter ‘21). Since being a participant was out of the question (Iditarod mushers and their dogs are on par with elite Olympians), I decided to serve as one of the countless volunteers who make it possible.

When we moved past the gate and into the race chute, thousands of cheering fans waved and shouted, a wild vortex of adulation.

I left Vancouver, BC, on February 28th to spend seven days in Anchorage, near the town of Willow, where the Iditarod officially starts. Known as the Last Great Race on Earth, the Iditarod stretches between Anchorage and Nome, over 1000 miles of backcountry wilder ness impassable during spring, summer,

and fall. It can take up to 14 days to complete the trek with mandatory safety, and health stops at up to 27 checkpoints boasting colorful names like Finger, Ophir, Cripple, Ruby, Nulato, Kaltag, Shaktoolik, Koyuk, and Elim.

As my flight descended into Anchorage, I saw the city sitting on a broad swath of white and green flatland edged by miles of exposed tideland. An escarpment rising into coastal mountains made the whole area look like a giant bowl of wilderness, spectacular and com pelling to anyone with a taste for nature in the raw.

I stayed at one of the Iditarod’s main sponsor hotels, the Lakefront Convention Center. For 30 years, the Lakefront has been ground zero for race registration, logistics, and communications. The fro zen lake behind the hotel conveniently provides a landing strip for bush planes to carry people, dogs, and supplies in and

out of checkpoints. This year, the hotel’s shocking decision to pull sponsorship for the foreseeable future created quite a stir, with people whispering about how the owner had caved to pressure from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), the Iditarod’s archnemesis.

The lobby décor resem bled a deserted hunting lodge, complete with enormous ani mal heads mounted on every wall and full-sized taxidermal displays around every corner. Caribou, moose, arctic fox, lynx, bear, birds, and fish stared blankly into space, complimented by a variety of antlers and pelts. Yet, as empty as it was when I arrived, within 24 hours, it felt like the Superbowl was in town. People filled the lobby, spilling out of the volunteer registration offices, lining up to purchase swag, and hanging around waiting for

transport to downtown Anchorage’s Fur Rendezvous Winter Festival. By evening, everyone was getting blotto in the hotel bar.

teer work, this was a paid contract with Dr. Stuart (Stu) Nelson, the Iditarod’s Chief Veterinarian for the last 26 years. Ensuring dog health, safety, and comfort was of primary importance at the Iditarod, and Stu was the ideal man to lead that charge. He made certain all volunteer vets and vet techs understood the unique needs and concerns of sled dog athletes.

My first job was to serve as a tech nical host for the International Sled Dog Veterinary Medical Association (ISDVMA) training, two full days of streaming presentations, and hands-on training for volunteer trail veterinarians and vet techs. Unlike my other volun

I also signed up for dog handler training despite the list of physical requirements designed to discourage most people. Dog handlers help mushers move their teams to the race start line. The role involves run ning through snow, stopping and starting on ice, and preventing dogs from moving the sled too quickly.

At least 30 people participated in the dog handler training I attended. We stood in a circle around our trainer, Jake,

The heartbeat of Cascadia 35 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

The heartbeat of Cascadia 35 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

hugging ourselves against the cold. Jake was a stocky man in jeans and a plaid shirt with a tan face lined by years of ex posure to the elements. He demonstrated

the basics of the job, then moved us into position along both sides of a team (one person per dog), and then began barking commands.

“GEE! Go right! Outside move faster! Inside slow down!”

“HAW! Go left! Keep up with the dogs! No lagging!”

We practiced holding leads (ropes attached to guidelines running the length of the dog team), following commands, and keeping our feet steady alongside our four-legged counterparts. The job was more challenging than I first thought because the weight and length of the sled made it clumsy to turn and extremely dif ficult to slow down.

You can’t wear cleats or anything that could possibly hurt a dog,” Jake warned. “If you slip and fall, you must immedi ately drop the lead and roll away from the team. Don’t wait for someone to help you. Get outta the way!”

It snowed heavily on Saturday, chris tening the ceremonial start with a fresh coat of white. Big soft flakes filled the air, piling in drifts throughout downtown Anchorage. Thousands of bystanders trudged along the slippery sidewalks, www.bellinghamcosmosbistro.com

“Conditions are gonna be very icy.

queueing in front of vendors peddling art, hot drinks, elk hotdogs, and bison burg ers; everyone bundled in coats, anoraks, hats, and gloves. Many sported animal heads mounted on their hats. I saw a lot of silver foxes sticking up from the crowd.

The side streets were blocked off into huge staging areas for the sled teams. Over 50 teams had registered with up to 14 dogs per team. By the time I arrived, barking and yelling drowned out all other sounds. I strolled the route, watching dog teams move into a long, slow procession toward the start chute marked with banners and blaring music. It looked like a cross between a parade and a military action. Crowds filled every bit of free space. Sports commentators bantered over loudspeakers about the mushers, the dogs, and the sponsors and periodi cally implored visitors to stand against PETA. People cheered, mushers waved, and everybody was having a good time. Except me.

I’d skipped breakfast and was feel ing quite hungry and tired. I scanned the street for a restaurant, but the few that were open had lines of people waiting. My brain fogged up as I lurched toward a corner table in a sushi restau rant. I chucked my backpack to the floor and dropped into a chair with my head between my knees. The room started

Alaska is Mecca for sled dog racing, with over a dozen yearly events, the 1000-mile Iditarod being its crown jewel. Known as The Last Great Race on Earth, the Iditarod combines athleticism, endurance, strategic decision-making, and backcountry smarts with an almost preternatural relationship between participating mushers and their dog teams.

Over the years, the Iditarod has built an extensive, active fan base spread across two dozen countries. Hundreds of volunteers apply annually for the privilege of helping run the event. They work in positions of communications, security, admin, transport, logistics, publicity, outreach, dog handling, and checkpoint support. In addition, volunteer veterinarians and vet techs travel from all over to work with Chief Veterinarian Dr. Stuart Nelson and the International Sled Dog Veterinary Medical Association (ISDVMA). The event also boasts an expansive educational mission (Iditarod EDU) with Teacher on the Trail™ video feeds and articles serving educators who make the Iditarod part of their curriculum.

What began in 1973 as a macho test of endurance has evolved into a world event that celebrates not just the unique characteristics of sled dogs and their rapidly diminishing arctic environment but also the dedicated mushers who struggle to keep this proud indigenous tradition alive and healthy.

The heartbeat of Cascadia

37 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

The heartbeat of Cascadia

37 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

turning sideways. Uh oh. I smoothed my hair, leaned toward the table of people next to me, and said in the calmest voice possible,

“Uhm, excuse me, but I’m just gon na slide down to the floor because I’m a little dizzy. It’s nothing, really.”

Then I was on my back under the table, and there I remained, eyes closed, for about 15 minutes. The restaurant was packed, but nobody said a thing. Later I realized I probably looked like I was drunk.

A server finally walked over and said, “If you stay, you’ve gotta sit on a chair.”

I looked up from the floor and blink ed. “I’m about to lose consciousness, you see. That’s why I’m down here.”

“Fine, but sit on a chair and do it. Not on the floor. Or leave.”

I took a few deep breaths, pulled my self into a standing position, hoisted the backpack, and walked stiffly out of the building with as much dignity as I could muster. Then I leaned against a brick

wall and slid back down to the cold, wet sidewalk. After a failed call for a taxi and another 10 minutes of freezing my butt off, the dizziness finally began to abate. Eventually, I caught a bus back to the ho tel, where I ate a full meal, drank a gallon of water, and slept like the dead.

Sunday morning, I boarded a bus full of volunteers heading for the race start in Willow. Unnerved from that ugly blood sugar drop the previous day, I ate a good breakfast and felt much better. Besides, it was my day to handle dogs.

The race start (known as the restart) was similar to the ceremonial start in that there was an enormous staging area, a clearly marked start chute, lots of elk hotdogs and bison burgers, and a ton of security. But yesterday felt like a party. Today was all business. The restart is the beginning of the actual race.

Nobody was allowed into the staging areas except for dog handlers, where we gathered to receive assignments. Instructed, in no uncertain terms, to shut

up and wait for instructions and not to bug the mushers or the dogs, I waited next to my team, watching the musher calmly leash and unleash his dogs, then squat down at eye level and talk quietly with them. Despite the overwhelming noise and chaos in every direction, the connection I witnessed was calm, loving, and very personal.

Teams all around us were busy harnessing up and those in charge communicated by hand signals because of the noise level. The dogs radiated heat and joy. These were experienced athletes, clearly familiar with what was about to happen. They knew the trail, knew their musher, and they were ready to go.

Dog attitude is critical. Sled dogs have minds of their own,

Nordic Ultratune is dedicated to helping you get the most out of your skis - and yourself - through the most up-to-date precision stone grinding and waxing techniques available

Compared with most professional sports organizations, the Iditarod is small and regional. Sponsorships for the race are hard-won. Participants vie for purses that barely make a dent in their annual budgets. The event itself is run almost entirely by volunteers and feels more like a community project than an organized sport.

Unfortunately, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) has labeled it a “deeply disturbing, despicably cruel dog race.” Over fourteen major Iditarod sponsors (Jack Daniels, Coca-Cola, etc.) have pulled their support due to PETA’s misinformation campaign and political clout. PETA has also successfully demonized the relatively small cadre of professional mushers who build their lives around racing in partnership with sled dogs. Sure, mushing has a checkered past. If PETA were protesting the Iditarod of old, I’d probably agree. But 50 years later, things have changed. Instead of glorifying an unwholesome win-at-any-cost mentality, the race now champions mushers who put their dogs first, even before winning. In addition, anyone who treats their dogs poorly will find themselves vilified by the community and booted from the race.

The Iditarod’s Chief Veterinarian, Dr. Stuart Nelson, trains and deploys a sizeable pool of volunteer veterinarians and vet technicians who monitor every dog at each of the (up to) 27 checkpoints along the route. They keep detailed records and reserve the right to pull any dog from a team if it is determined to be in the dog’s best interest. The mushers themselves welcome the increased medical support, often soliciting input regarding concerns they’ve noticed on the trail. Dogs who show signs of illness or injury are immediately flown back to Anchorage, where veterinarians tend to their needs and send updates to anxious mushers who worry like parents.

C’mon, PETA. I’m sure there are other places where you can better focus your energy. It’s time to lay off the Iditarod.

so if they don’t feel like racing, they won’t. Many mushers have been stuck at check points because their dogs decided they were done. That’s why a big part of sled dog training includes ensuring the dogs always have a good time. I talked with a rookie Iditarod musher (very experienced, but his first time at the Iditarod) whose job wasn’t to win but rather to run a team of “pups” down the trail, making sure their tails were wagging the whole time.

I found myself leashed to a gang line between two dogs yanking at their harnesses in excite ment. As they lunged forward, I instinc tively pulled to the side and leaned back to keep them in check. Their power was astounding. As a team, we trotted a short distance, then waited, then trotted, then waited again, then trotted again, all the while flanked by a security crew who sig naled and guided us as if we were airliners on the tarmac. The ice was wet and slip pery, and I often slid as the dogs pulled.

When we moved past the gate and into the race chute, thousands of cheer ing fans waved and shouted, a wild

vortex of adulation. I was sweating from the stress and exertion but kept tightly focused until my right foot slid out. “NOYOUDONT!” I shouted, throwing my weight sideways, dancing and flailing toward the fence. Somehow, I managed to regain purchase and grab the lead again. After a few sheepish steps, I glanced back at the fans. Many of them

were cheering, giving me a thumbs up. It was a delightful show of support. I broke into a smile; my anxiety vanished.

By the time we reached the start chute, the dogs were going crazy. The loudspeaker countdown began, “10 – 9 – 8,” —the fans chanted along, “7 - 6 – 5,” —we unleashed our leads, “4 –3,” we stepped back from the team, “ 2 – 1 - GO!” Our dogs bounded down the icy runway as the crowd erupted into cheers, then settled back for the next team in the chute. Meanwhile, I hustled alongside the fence toward the staging area, passing teams lined up and waiting, their handlers hanging on for dear life.

in

like

Wedrove up the Baker Lake Road, each in our own car, past the gated campgrounds and shuttered ranger station. Above us the Mountain Gods —Kulshan and Shuksan—gleamed in the lu minous winter sun, fresh snow dazzling against a cobalt-blue sky.

I was sorely in need of a few days off the grid, and the weather window—a few consecutive days of winter sun shine—was too good to pass up. The pandemic was at its peak, and I hadn’t seen my old friend Joe in months. Although we had to keep our distance from each other, I looked forward to being able to spend some quality time together enthralled by beauty, something the two of us had been doing for more than 30 years, everywhere from Arizona to the Yukon. A lifetime

of shared grandeur; it made for a deep connection.

Continuing up the unpaved road, we negotiated numerous downed trees and potholes big enough to get lost in. At the end of the road, we pulled into the empty Baker River Trailhead parking lot and pitched separate tents at the edge of the mossy forest along the riverbank.

A river of mist, mirroring the river itself, drifted through the bare trees on the opposite shore. We sat on the rocky beach for an hour, watching the afternoon unfold and listening to the music of the river, a tone poem of gurgling water, restless wind in the trees, and the croaking of philosophical ravens.

The sun moved across the sky, riding the ridgeline, before dropping from view, casting the scene in indigo shadows, the

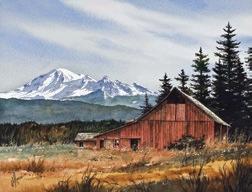

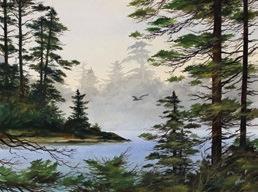

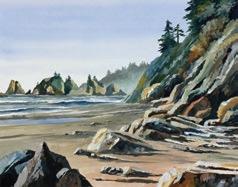

Over the years, I have created thousands of paintings of historical and contemporary maritime, landscape and wildlife themes, representing the natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest.

I have also created artwork for industrial and military clients, illustrating commercial vessels of all types, oil tankers and refineries, aircraft carriers, and submarines. Researching paintings of such diverse topics, I have become increasingly aware of the ascendency of the industrial and the military and the increasing population’s effects on our environment. Taking the time to research and study our surroundings as an artist creates a desire to bring attention to the precarious balance of the natural world and to promote an understanding of our collective relationship to the environment.

James Williamson’s paintings are displayed at Whatcom Art Market, 1103 11th St., Bellingham, WA. See more of James’s art at James-Williamson.pixels.com

Top: Whatcom County Landscape, Secluded Cove. Middle: Driftwood Glow, Olympic Coast Headlands. Bottom: Loons Misty Shore, Wetland Beauty, Realm of the Orca

surface of the water burnished with a me tallic luster. A water ouzel danced among

the rocks in the river, impervious to the chill that had descended with the onset of day’s end, just another day on the job here in the north woods.

Dinner by the fireside beneath a cavalcade of glittering stars. How many nights have Joe and I sat beside the fire? Too many to count. The comfort of an evening beneath the night sky shared with an old friend cannot be adequately expressed in words.

In the morning, we indulged ourselves with a small campfire to warm our bones, drinking coffee and admiring the early light on the river be fore heading up the Baker River Trail, past moss gardens and ferns glossed with a patina of ice. Tendrils of mist snaked downstream above the river, but the sky overhead was crystal clear.

Hanging old man’s beard, backlit by the incandescent winter sun, adorned

the Tolkienesque forest. Shadowy grot tos invited exploration. From the the middle of the suspension bridge span ning the Baker River, the ice and water below us swirled in an elegant and poetic way. The water was so clear; it was as if it didn’t exist except as movement, highlighted by the rich winter light reflected on the surface in undulating oranges and blues.

We walked back to camp through a decoup age of pressed leaves, the forest floor a botanical mosaic. Is there anything more beautiful than the filagree of frosted lichen?

Beside a small fire kindled as the last light faded, we talked late into the night under a canopy of stars. Eventually, the gaps of silence grew longer, broken only by the incantations of owls somewhere in the darkness. The moon rose, and the river whispered a reflection. ANW

Story by Rand Jack

Story by Rand Jack

Water is life. The watercourses that flow through the moun tains, hills, and valleys of Cascadia nourish the land, support terrestri al populations (human and otherwise), and sustain the salmon that have been, literally, the lifeblood of the Pacific Northwest since time immemorial. A network of spar kling tributaries feeds the branches of the Nooksack River, providing cool, clear water and offering refuge to the iconic salmon. Among these tributaries, there is one known as Skookum Creek.

The name Skookum Creek comes from “Chinook Jargon,” the ancient trade language that facilitated robust trade among indigenous peoples in the Pacific Northwest. Skookumchuck means mighty or powerful water. In both quan tity and quality, Skookum Creek is the most critical and mighty tributary of the South Fork of the Nooksack River, which provides habitat for a variety of salmon, including spring Chinook, late fall Chinook, coho, pink, chum, and sock eye, as well as summer-and winter-run steelhead, bull trout, cutthroat, rainbow, and Dolly Varden trout. Spring Chinook and bull trout (a salmonoid species) are listed as threatened under the Federal Endangered Species Act. The viability of their habitat is at risk.

Bill James, master weaver and hered itary chief of the Lummi Nation, record ed an interview in 2018 for Revitalizing Cultural Knowledge and Honoring Sacred Waters: an Oral History of Life on the Nooksack River. His words set the stage for the need to conserve Skookum Creek. Chief James, now deceased, was born in 1944 and grew up in a Lummi village on the lower Nooksack River, not far from where it enters Bellingham Bay. “I was born and raised down there and used to listen to my grandfather talk…. everybody took care of everybody…. our people took care of the river.”

Chief James reminisced about the Nooksack River of his youth. “We used to harvest 10 to 12 tons of salmon a day out of our river. We used to jump off the bridge into the

river, dive into the river, it was so deep there…. the river was clear at one time… you could see the bottom.” By restricting fishing times, “we practiced conservation for future generations to come.”

Over time, Chief James saw disturb ing changes in the Nooksack. “You look back at how the river has changed so much. Nowadays, it makes me cry to look at our river because I know why it’s the way it is. I know that the farmers are taking water. All the people … are taking the wa ter out of our river... and the water level is decreasing. All the clear-cutting is causing siltation, and the river is getting shallow.”

Chef James re called a time when the Green Giant company harvested peas and threw the waste into the river, creating a “gooey slime … thick on the bottom of the river. So, they killed a lot of salmon.”

In a 2016 Tribal Voices Archive Project interview, Lummi Elder Steve Solomon summed up the role of the river in his people’s lives: “My grandparents echoed that idea all the time that water is like that blood that runs through your veins. Water is the lifeblood of everything—the trees around you, the grass around you,

everything it touches needs to be clean. That goes through to the salmon too.”

Today, increased water temperature, sediment load, and decreased flow at critical times threaten the once bountiful aquatic habitat of the Nooksack’s South Fork, which is now identified as an im paired water body under the Federal and State Clean Water Acts. As the primary source of cool, clear water to the South Fork, Skookum Creek is well suited to help ameliorate these impairments.

While degradation of the South Fork ecosystem has a long and relentless history, last year, two traumatic events highlighted what a future in the grip of climate change holds for the South Fork without decisive intervention.

First, the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission Winter 2022 magazine, Northwest Treaty Tribes, reported a cata strophic adult Chinook salmon die-off: “After last summer’s record high tempera tures and low water flow, Lummi Natural Resources staff discovered [in September] about 2,500 dead adult Chinook in the South Fork Nooksack River…. [T]he dieoff was the result of severely degraded habitat quantity and function.” While Chinook have strug gled with degraded habitat for decades, “climate change is the straw that broke the salmon’s back and resulted in this tragic die-off,” said Lummi Indian Business Council member Lisa Wilson.

Second, the January 15, 2022, Northwest Treaty Tribes publication reported that historic late November storms “delivered a tor rent of sand and gravel [in Skookum Creek] that clogged the [Lummi] hatchery’s 36-inch intake and prevented fresh water and oxygen from reaching hatchery fish.” Lummi fishery staff said, “past logging practices have affected the amount of sediment and debris carried by the creek during storm events.” It also

The heartbeat of Cascadia 47 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

noted that “with the Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association (NSEA) and the Whatcom Land Trust (WLT), we’re looking at how to address some of these impacts to salmon.”

In response to the river deg radation, Whatcom Land Trust purchased 2147 forested acres along Skookum Creek and the adjacent Mustoe Marsh from Weyerhaeuser timber company in 2019-21 for 5.6 million dollars. Contributions came from individuals, a private foundation, WLT, state grants, and the Whatcom County Conservation Futures Fund. The acquisition relied on extensive information compiled by the Nooksack Indian Tribe Natural and Cultural Resources Department, the Lummi Nation Natural Resource Department, and WLT.

In support of the Skookum project, the Nature Conservancy wrote: “Protection and restoration of riparian forests within the Skookum Creek wa

tershed will support salmon recovery and increase freshwater and forest resilience in the face of climate change…. This purchase … has outsized significance to

sive instream habitat improvements made by the Nooksacks and Lummis. Beyond the reach of memory, this land has been home to indigenous people. A powerful interest shared by the Nooksacks, Lummis, and WLT motivated the purchase—an interest in the cold, clear creek water essential to the Nooksack’s South Fork and its salmon in the wildlife corridor con necting the upper Skookum Creek watershed to the lowland South Fork Valley, and in the effort to protect forests for carbon sequestration.

the water quality, quantity, and habitat benefits to all the living communities that rely on the South Fork Nooksack.”

The Skookum Creek acquisition alone certainly cannot restore the health of the South Fork. Still, it is a step in the right direction—a complement to the exten

To learn about the traditional uses of Skookum Creek by indig enous peoples, I spoke with Jeremiah Johnny, a Nooksack tribal member, and employee of the Nooksack Indian Tribe Natural and Cultural Resources Department. Jeremiah had, in turn, learned from Nooksack elders. Coming from as far away as what is now Ferndale

and Lynden, the Nooksacks traditionally gathered, often with friends and relations from neighboring tribes, for a weekslong encampment on lower Skookum Creek. This gathering came to be called “Summer on the South Fork.” The people valued the cold, pure Skookum Creek water for ceremonial cleansing— “something to exhilarate.”

Men pulled canoes up lower Skookum Creek to the summer en campment where women, children, and some men stayed to gather “anything and everything they could dry and store for the following winter,” including greens, blackberries and blueberries, Camus bulbs, bracken fern roots, and other roots, and salmon. As a youth, Jeremiah’s father discovered some old drying racks along lower Skookum Creek.

Beyond the summer encampment, the rest of the men, and boys coming into manhood, continued to pull the canoes upstream as far as the base of the Twin Sisters Range to hunt deer, elk, cougar, bear, and mountain goats, highly valued for their wool. Again, the mission was to dry and prepare the meat for the following winter. The tribe also maintained a permanent vil

lage with longhouses near the mouth of Skookum Creek and took King Salmon by dip nets and spears below the fish barrier at about 2.1 miles upstream. The Nooksack name for Skookum Creek was Nuxwaynaltxw — “Slaughterhouse,

calendar online.

a place to dry, a place to prepare.”

Jeremiah related that a Nooksack elder’s grandfather told him that in the canyon about a mile above the mouth of Skookum Creek, “a giant fish lived, a fish that he believed was the mother of all salmon , and he had seen that fish go into a cave in the canyon.”

Jeremiah Johnny characterized Skookum Creek conservation as “a big

win.” As a part of that big win, the WLT board and staff intend to work with the tribes to accommodate traditional prac tices on the Skookum Creek property, consistent with the Land Trust’s conser vation and public access commitments. Whatcom Land Trust will man age the Skookum property to protect and restore the forests to old-growth conditions with mixed species and tree ages and to revitalize Skookum Creek’s natural hydraulic functions. WLT will plant and thin where necessary to promote forest health and nurture the growth of larger trees to shade the water, stabilize the banks, and provide for the recruitment of large instream wood. Logging roads on the property not needed for for est conservation stewardship have been decommissioned and will be allowed to revert to nature. Currently, WLT is working with NSEA to complete stream surveys and with the Lummi Nation to design creek restoration plans to im prove natural stream functions.

Because of its steep gradient, Skookum Creek is uniquely suited to help address problems of temperature, sediment, and flow in the South Fork. Thirty-three percent of Skookum’s wa

The heartbeat of Cascadia 49 stories & the race|play|experience

The heartbeat of Cascadia 49 stories & the race|play|experience

When a wild chinook thrashes the air above Kettle Falls the coiled spring of its body ripples with the surge of 700 river miles toward home.

The river’s story, descending through epochs of ice and stone, coalesces in the salmon’s momentary flight.

ply of the cold, clear water needed for salmon repro duction. In addition, the Lummi Nation’s Skookum Creek Hatchery, located near where Skookum Creek joins the South Fork, depends on Skookum’s water quality to pursue its mission of restoring the South Fork’s endangered spring Chinook run. Trees are the key to water quality.

The river pours its thunder between striate sea bottom rocks: a glassy tongue imploding into whiteness.

To the salmon it is a beckoning arm.

There is no human gesture so fervent —this long journey inland— no effort so seamlessly one with its element.

The salmon’s heart is the river’s heart made flesh. The salmon’s flight, a pulse.

Ours is the wisdom to see them both as one; power to power joined: one falling, one borne by a wisdom all its own in ascendance.

tershed is above the seasonal snow zone, where the average temperature is 32 degrees Fahrenheit. The melt from seasonal snowpack accumulations in the upper watershed adds signifi cantly to streamflow, providing an extended supply of cold water to the South Fork. An increase in shade due to trees left standing adds to this phenomenon. Because the upper South Fork watershed is of significantly lower elevation, this Skookum effect is critical.

During times of low river flow, Skookum Creek supplies 22% of the South Fork’s volume, ensuring a continuous sup

Commercial forestry in the Skookum Creek basin has historically increased sediment load, accelerated run off, and raised water temperature. Numerous landslides associated with logging and roads exist throughout the Skookum Creek watershed. Over a 40-year period, 263 landslides delivered sediment to streams in the Skookum Creek watershed. Of these, 75% were associated with timber harvest, landings, and roads. Recent analysis found that 33% of Skookum mass wasting events were attributable to logging roads. Allowing logging roads to return to nature will help normalize stream func tions such as sediment input, channel formation, and in-stream wood recruitment, affecting water quality and quantity locally—and in the South Fork.

Intact upland forests affect the storage and movement of sediment, water, and wood through the water shed and downstream into the South Fork. Logging adds to sediment loads by increasing slope erosion and reduc ing soil root cohesion. Clear cuts reduce soil water storage capacity and increase runoff, increasing the frequency of floods that erode and transport sediments. The health of upland forests influences the amount and retention of upland snow and soil water storage capacity affecting water temperature and streamflow.

Permanent protection of Skookum’s riparian forest will result in taller, older trees that will provide more temperaturelimiting shade, reduce bank erosion, enhance sediment filter ing, and create a dependable supply of large, stable instream wood. Substantial instream wood significantly alters stream functions by increasing “hydraulic roughness,” which dissipates the erosive energy of the creek, thus slowing the water velocity and triggering the deposition of sediments. Substantial in-stream wood also helps create habitats such as deep pools and calm refuges. The benefits of restoring and protecting Skookum Creek’s forests flow directly down to the salmon habitat of the South Fork.

A healthy Skookum forest also enhances terrestrial habitat, providing a critical link in the Cascades-to-Chuckanut Natural Area, the last relatively undevel oped corridor connecting the Salish Sea

to the Cascade Mountains. Elk, bear, cougar, deer, beaver, bobcat, and other species, increasingly likely to include wolves, inhabit the forested watershed, along with numerous smaller creatures essential to the ecosystem. Nooksack Elk utilize the corridor to move be tween winter foraging in the South Fork Valley and summer calving at the base of the Twin Sisters, as do black bears for seasonal migration.

The Skookum property shares a border with The Nature Conservancy’s 520-acre Arlecho Creek Old Growth Preserve, which has one of the highest breeding densities for marbled murre lets in Washington. These small birds, referred to by the Audubon Society as “a strange, mysterious little seabird,” are listed as threatened under the fed eral Endangered Species Act and as endangered in Washington State. Putting the Skookum property on an irrevers ible path to once again being a complex old-growth forest creates possibilities for seriously expanding Murrelet nest ing habitat. The same is true for the northern spotted owl, which, like the marbled murrelet, is federally listed as threatened and Washington State listed as endangered. Spotted owl and mar bled murrelet conservation is a longterm project. However, conserving the Skookum Forest could be a significant step toward bringing the species back.

While a seasonal wildlife migration corridor was a well-recognized attribute of the Skookum Creek acquisition, Professor Gretta Pecl of the University of Tasmania suggests a different kind of migration corridor potentially at play here, a relocation of populations from warmer to cooler habitat, a relocation driven by climate change. Dr. Pecl is a lead author of Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptability and Vulnerability, the Working Group II section of the 2022 report from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

In an email to me, she wrote: “The latest IPCC report … actually states that where species have been explored/ examined on average 50% of species have been documented to be already

shifting.” The steep gradient of the Skookum Creek drainage runs from 400 feet to approximately 3,000 feet on WLT property and beyond on un protected land to about 4,500 feet at

The

51 stories & the race|play|experience calendar online.

heartbeat of Cascadia

The Skookum Creek Project.

heartbeat of Cascadia

The Skookum Creek Project.

the base of the Twin Sisters. Perhaps the conservation of a major segment of the drainage will help a procession of species relocate to suitable habitats for decades to come.

Sequestering carbon is another sig nificant benefit of the Skookum Creek project. Dr. William Moomaw, the lead author of five reports by the IPCC, says: “[I]n order to meet our climate goals, we have to have greater seques tration by natural systems now. So that entails protecting the carbon stocks that we already have in forests, or at least a large enough fraction of them that they matter.... The most effective thing that we can do is to allow trees

that are already planted, that are al ready growing, to continue growing to reach their full ecological potential, to store carbon, and develop a forest that has its full complement of environmen tal services.” This is exactly what WLT envisions for the Skookum property.

Recent research shows that younger forests, less than 140 years old, sequester carbon at a faster rate than old-growth forests. Virtually all of Skookum Forest fits into this category. Protected, it will have many decades, and for most of the trees, a century or more, of expeditious carbon sequestering.

And yet another public benefit of reviving and protecting this property

will be a 5.3-mile trail in a splendid natural setting along an existing forest roadway with stunning views of the Twin Sisters Range.

Restoring forest health and eco logical integrity, bringing back natural stream functions, upgrading salmon habitat, enhancing and protecting wildlife habitat, sequestering carbon, enabling traditional indigenous prac tices, and providing for nature-based recreating—these are the goals of the Skookum Creek project, and much of what a sustainable future here in the Pacific Northwest is all about.

The existence of this image is a testament to not taking no for an answer. The string of events that culminated with me landing a contract tech job working four long, dark winter months at Summit Station, Greenland, is frankly too protracted and absurd to relate here fully. But, highlights include chasing a girl eight thousand miles to the bottom of the world and back again, fixing a printer for exactly the right guy at precisely the right time, and winning a bet with an engineer about the sur