CORDOVA HOOKS BIG DATA

SAM ENOKA Founder & CEO Greensparc

CLAY KOPLIN CEO Cordova Electric Cooperative

Jamey Bradbury

Tracy Barbour

Thank you, Alaska, for voting First National Bank Alaska as the Best Place to Work for the ninth year in a row, the Best Bank for the fourth year in a row, and Best in Customer Service. We’re thrilled with your confidence in our mission to provide a work environment where employees and customers feel appreciated and respected. We’ll do our best to keep earning your trust.

CONTENTS SPECIAL SECTION: ENERGY

12 GIRDING UP THE GRID

Investments in Railbelt electricity transmission

22 STEADY AS SHE FLOWS

Government money pours into run-ofriver hydro projects

28 COLD WATER, WARM CITY

The Seward Heat Loop Project

By Rachael Kvapil

36 SEEING THE LIGHT

Solar power under the midnight sun

By Vanessa Orr

32 VOLCANIC RUMBLINGS

Geothermal grid power seems closer than ever

CORRECTION: In the July 2024 Table of Contents and on page 58 of that issue, we misspelled the first name of one of our freelance writers: the author’s name is Mikel Insalaco, not Mike.

16 VIRTUOUS CIRCUIT

Cordova data center sparks renewable energy demand

ABOUT THE COVER

Cordova has an enviable problem. On the edge of the Chugach Range rainforest, the coastal town of fewer than 3,000 people has access to abundant hydropower. Its run-of-river facilities generate, at times, more electricity than the community needs. Clay Koplin, CEO of Cordova Electric Cooperative, needed an “anchor tenant” to soak up surplus power that nobody else was buying.

Enter Sam Enoka. Raised in North Pole, Enoka is the founder of California-based Greensparc, a company that developed modular, scalable computing centers. As told in this month’s article “Virtuous Circuit,” siting a distributed data server in Cordova solves Koplin’s electricity surplus problem while putting advanced cloud-based technology microseconds away from Alaskan users.

Photography by Chelsea Haisman

By Alex Appel

By Dan Kreilkamp

By Rindi White and Scott Rhode

By Joseph Jackson

Paul Craig

| GeoAlaska

Chelsea Haisman

FROM THE EDITOR

The big news for Alaska as I write this in early July is the Record of Decision of No-Action for the Ambler Access Road, and thus the Ambler projects. While on its face this news is about mining and transportation, to me it is closely tied to the legal and energy themes of this issue.

On the energy front, every major remote project in Alaska has at least two major obstacles in common: how to get power in and how to get the resource out. Both require the development of infrastructure, which is expensive to build and maintain.

On the legal side, the Ambler projects (and projects like them) are a magnet for lawsuits. While some stakeholders in the region are relieved that this road has reached an apparent dead end, others are incensed that the federal government has once again put halt to a project that does have some local support and despite the fact that access to this area is addressed in the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. Some say denying access is a violation of federal law, and I’m sure lawsuits will follow asserting that belief. Then again, had any version of the access road been approved, there also would have been lawsuits in the project’s future. If anyone were to go mining for lawsuits, Alaska is the place to do it.

Interestingly, the project’s ties to energy and legal/policy stretch further. The Ambler projects would potentially produce rare earth elements, copper, and gold, all of which are critical minerals for renewable energy projects. In addition to solar panels or turbines, renewable energy projects generally require battery storage solutions to be effective, as wind, sun, and currents all— unforgivably—operate on their own schedule.

Nationally, the Biden administration is pushing for the development of critical minerals domestically, though apparently its definition of domestic is “within the country, but not in Alaska.” Part of this push is so that the country can transition to an energy future that relies less on fossil fuels.

The Ambler projects, which could provide materials to build a renewable energy future, have been halted by an administration advocating for that future.

Don’t take that as myself or this publication advocating specifically for the Ambler projects; rather, I’m highlighting the frustrating loop Alaska is caught in year after year. We want economic development; we want community buy-in for that development. We want to develop our resources, and we want to protect them. These are not opposing ideas, for Alaskans, and if this decision-making were placed in our hands, I’m confident we’d see not every project—but the right projects—move forward.

On the bright side, energy projects in Alaska, many of which are covered in this issue, are constantly under development, to the benefit of communities large and small. And the legal industry? There’s more than enough work available to keep those professionals busy.

Tasha Anderson Managing Editor, Alaska Business

EDITORIAL

Managing Editor Tasha Anderson 907-257-2907

tanderson@akbizmag.com

Editor/Staff Writer

Scott Rhode srhode@akbizmag.com

Associate Editor

Rindi White rindi@akbizmag.com

Editorial Assistant

Emily Olsen emily@akbizmag.com

PRODUCTION

Art Director

Monica Sterchi-Lowman 907-257-2916 design@akbizmag.com

Design & Art Production

Fulvia Caldei Lowe production@akbizmag.com

Web Manager

Patricia Morales patricia@akbizmag.com

SALES

VP Sales & Marketing

Charles Bell 907-257-2909

cbell@akbizmag.com

Senior Account Manager

Janis J. Plume 907-257-2917 janis@akbizmag.com

Senior Account Manager

Christine Merki 907-257-2911 cmerki@akbizmag.com

Marketing Assistant

Tiffany Whited 907-257-2910 tiffany@akbizmag.com

BUSINESS

President

Billie Martin

VP & General Manager

Jason Martin 907-257-2905

jason@akbizmag.com

Accounting Manager

James Barnhill 907-257-2901 accounts@akbizmag.com

CONTACT

Press releases: press@akbizmag.com

Postmaster:

Send address changes to Alaska Business 501 W. Northern Lights Blvd. #100 Anchorage, AK 99503

This year, TOTE Maritime Alaska celebrates 49 years in the 49th State! TOTE is proud to have served Alaska since 1975, connecting communities with dedicated, reliable service from Tacoma, WA to Anchorage, Alaska. With our “built for Alaska” vessels and roll-on/roll-off operations, our service and operations were designed to meet the unique needs of the customers and communities of Alaska. Join us in commemorating nearly half a century of excellence in shipping to the Last Frontier.

IN THE 49TH

Energy Special Section

Al aska is bursting with more energy than it can handle, yet accessing it remains a challenge. A community may sit at the foot of a volcano without being able to tap its heat or watch the raw power of a river just flow by. High energy costs stand in the way not just of small communities but major projects that would pencil out easily in any other part of the world yet teeter in the balance in remote Alaska. Alaskans address these challenges head on to unlock the state’s vast energy potential. When the people of this state are fully powered, who knows what they might accomplish next.

Girding

Up the Grid Investments in Railbelt electricity transmission

By Alex Appel

The Railbelt has no redundancy.

“If we have a power problem in Anchorage and the line to Fairbanks goes down, we don’t have a Plan B,” says Curtis W. Thayer, executive director of the Alaska Energy Authority (AEA).

In the past, natural disasters have forced parts of the electricity transmission grid from the Kenai Peninsula to Fairbanks, a 700-mile corridor known as the Railbelt, to close.

In 2019, a wildfire near Cooper Landing shut down part of the Sterling to Quartz Creek transmission line for four months in the summer. Not only were Chugach Electric Association (CEA) and Matanuska Electric Association (MEA) cut off from the Bradley Lake

Hydroelectric Project near Homer, forcing them to purchase more natural gas, but the water level at the dam overflowed, wasting energy. The ordeal cost Alaskan ratepayers more than $10 million.

Last November, another section of that line was closed for around a week because of a snowstorm. It was fixed quickly, but the incident was a warning sign.

“What happens if it was down for a month in the middle of winter? That would be very bad. This last winter we had this very bad cold snap, and we were using all the natural gas we can and using Bradley power as much as we can,” says Thayer, “but if that line was down, we would have had

major problems; that’s 10 percent of our power needs.”

The Railbelt grid also supplies power to five military bases, adding to the urgency for more reliability. Another problem is inefficiency due to the distance involved. Around 17 percent of power from Bradley Lake, the largest hydroelectric dam in the state, is reserved for Fairbanks. The miles of wire in between result in unavoidable “line loss.” Thayer says there are times of the year when one-fifth of the energy sent from Bradley Lake to Fairbanks just bleeds away into the air.

These vulnerabilities have driven efforts to fortify the Railbelt grid, just as funding arrives to pay for the longawaited improvements.

James Pendleton

| US Department of Agriculture

Transmission Limits

The Railbelt is the heart of Alaska’s energy grid. Feeding power to threefourths of the state’s population, it is managed by AEA in cooperation with five regional power utilities: CEA, MEA, Golden Valley Electric Association (GVEA), Homer Electric Association, and City of Seward electric department. Although each entity is responsible for its own region, the Railbelt grid makes it easier to improve power generation, lower energy costs, and increase transmission capacity.

But things are not perfect.

“The transmission systems that make up the Railbelt were designed to meet the needs within each service area but have limited capacity to transmit power in several locations,” says Julie Hasquet, senior manager of corporate communications for CEA. “The result is congestion at these interties, which limits the transmission of power throughout the Railbelt.”

Many of the transmission lines in the Railbelt are more than forty years old and need to be upgraded to meet current demand, according to Thayer.

Also, a shortage of natural gas looms in the future. Historically, the Railbelt has relied on natural gas from Cook Inlet. In 2022, that fuel provided two-thirds of the energy used in the grid, according to a recent report from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. However, that resource is declining, so utilities are looking for other resources.

Railbelt Innovation Resiliency Project

To address these issues, the Railbelt Innovation Resiliency project was devised as a multi-pronged strategy.

One part aims to integrate highvoltage direct current (HVDC) submarine cables into the grid, parallel to existing lines carrying alternating current. These cables will run from the Kenai Peninsula, across Cook Inlet, and to the Beluga Power Plant, which services Anchorage and the Matanuska-Susitna Borough. As AEA explained to state legislators in April, HVDC across Cook Inlet will act as a redundant transmission system.

AEA also wants to build one or two battery energy storage stations, one

“A lot of wins for everyone involved in this, but at the end of the day, the ratepayers and the citizens on the Railbelt are going to benefit the most.”

Curtis W. Thayer Executive Director Alas ka Energy Authority

“The transmission systems that make up the Railbelt were designed to meet the needs within each service area but have limited capacity to transmit power in several locations… The result is congestion at these interties, which limits the transmission of power throughout the Railbelt.”

Julie Hasquet Senior Manager of Corp orate Communications

Chugach Electric Association

in Anchorage and one in Fairbanks. GVEA has pioneered utility-scale battery storage in Fairbanks, and a more modern technology is being tested in Soldotna. In June, the US Department of Agriculture awarded GVEA a $100 million loan for a lithium-ion system. Thanks to GVEA’s partnership with Doyon, Limited, the Alaska Native corporation for the Interior region, up to $60 million of the loan qualifies for forgiveness.

Enhanced transmission and storage capacity outlined in the resiliency project would increase redundancy and security of the electric grid. As a bonus, upgrades would also simplify the integration of renewable energy into the Railbelt.

“Expanding the capacity of these interties will allow for the lower-cost generation resources to be available to all customers on the Railbelt and will enable new utility-scale wind, solar, and hydroelectric renewable projects to be more cost effective for customers,” Hasquet says. “Renewable projects are built where the resources are located, and transmission must be built to bring that additional clean energy to consumers.”

In addition to furthering longterm sustainability goals, Alaskans will see immediate benefits once the upgrade is complete.

“The best part about that is if there’s an earthquake or a natural disaster or something, and that one line goes down, we’ve got that secondary line; we’ve still got power on,” Thayer says.

Getting a GRIP

If all that new energy infrastructure sounds expensive, it is. Luckily, the cost is being spread over a decade of installation, and some federal support is on the way.

Last October, the US Department of Energy (DOE) distributed $3 billion across the country for the Grid Resilience and Innovation Partnership (GRIP). Alaska’s share is $206 million, to be administered by AEA for the Railbelt Innovation Resiliency Project.

“This is going to transform the Railbelt in Alaska,” says Thayer.

The state would need to match that funding. While $206 million has not yet been set aside, the Railbelt

upgrades will take around eight years to complete. And in the short term , the legislature set aside nearly $33 million for the Railbelt upgrades.

“I’m optimistic that the State will match the grant funding,” says Representative Mary Peltola. “I’ve spoken to many legislators about this project, and they understand the gravity of affordable, reliable energy in the state. I understand our legislature has a lot of tough decisions about funding, but I’m going to continue to advocate for cheaper and more reliable ener gy on the Railbelt.”

In its April presentation to the House Finance Committee, AEA projected that it will complete an environmental impact assessment and find a contractor by the end of 2027. That’s when the big spending will begin, according to Thayer.

Energy Boost

The actual construction of the upgrades is expected to start in 2030.

Although the specific costs for each part of the Railbelt Innovation Resiliency Project have not been hammered out, Thayer is confident that all parties involved will come to an agreement.

“Considering we only got the award in October, and the legislation and the utilities were able to work together and bring almost $33 million to the table, I think you’ll see some sort of plan this year and next year to do that,” he says. “There’s a lot of support for it. Everybody understan ds the need for it.”

Since DOE is matching what the state puts forward, Alaska should secure around $66 million when the grant agreement is done in the fall. Thayer believes that amount is more than enough to get started in the first year.

The state expects 650 “highly paid jobs” while also establishing apprenticeship and internship programs during construction.

“A lot of wins for everyone involved in this, but at the end of the day, the ratepayers and the citizens on the Railbelt are going to benefit the most,” Thayer says.

For the one-quarter of Alaskans not plugged into the Railbelt grid, the project represents a statewide

economic boost. “Whether you’re on the Railbelt or not, more energy supply means we all get more for less,” says Peltola. “For engineers, truckers, and workers, it means more jobs constructing an energy grid of the future.”

Completing the Circuit

Strengthening the backbone of the Railbelt grid opens opportunities for its constituent utilities. MEA Chief Strategy Officer Julie Estey is already envisioning the possibilities.

“We sit right in the center,” says Estey, “so we can buy and sell power between MEA and Chugach Electric pretty easily; we have some redundant transmission among us. But if we want to look at any projects on the Kenai or in the Interior, or if we want to do anything collaborative with Homer Electric or Golden Valley, we’re really limited in the current system in a couple different ways.”

Those limits are primarily technological and administrative, according to Estey.

The limitations include insufficient energy storage and transmission lines that are too small to move large amounts of electricity. “Right now, we have low transmission and storage capacity, meaning it’s not practical to build more energy production here,” says Peltola. “If a power plant makes more power than their surrounding area is consuming, that power can’t be stored, and it’s expensive to send it to the next community over. Those logistical challenges are stopping projects throughout the Railbelt.”

The Railbelt grid was not built with interconnection in mind. Originally, the five different power utilities evolved to serve their local populations. “Because we all own our own small segment of the transmission line. It's not necessarily operated as a whole,” Estey says.

Over time, the regions grew bigger, and the populations became closer. A major step toward integration occurred in the ‘80s with the construction of the Alaska Intertie, a 170-mile transmission line betwe en Willow and Healy.

The more interconnected the grid is, and the more efficiently utilities can move electricity around, the less

energy costs. In Mat-Su, energy costs $0.20 per kWh, and around $0.08, or 40 percent of that, is the cost of generating energy, according to Estey. As the grid becomes more integrated, and it is easier to access energy from other regions, that cost will decrease.

Recognizing the advantages of cooperation, the utilities formed the Railbelt Reliability Council in 2022. The nonprofit gives each participant a voice in developing reliability and interconnection

standards. The council is also a forum for joint planning, guiding the implementation of the Railbelt Innovation Resiliency Project.

The unified front helped convince DOE to award GRIP funding fo r the work to come.

“The first and most important are the technical challenges, and that’s really what this GRIP is about,” Estey says. “That gets us a long way toward providing options as we look at our uncertai n energy future.”

Tu cked into a corner of the Cordova Electric Cooperative’s Humpback Creek Hydroelectric facility are two metal cabinets, each about 2 feet by 2 feet by 6 feet in size, that could contain the future of cloud computing.

Virtuous Circuit

Cordova data center sparks renewable energy demand

By Rindi White and Scott Rhode

The cabinets house a virtual mountain of data and computing capability. A few years ago, the amount of data housed in the two cabinets would have taken forty server racks, all humming loudly and putting off considerable heat. The small but mighty data center represents the next step in cloud computing in two ways: a combination of advances in technology—the ever-present drive to shrink the space needed for computing capacity—and the symbiotic location with the hydroelectric facility, which not only provides power to run the data center’s logic circuits but also cools the processors via fingers of copper pipe circulating water and glycol, keeping the electronics at an ideal temperature.

The data center is owned by Greensparc, an edge computing company led by Sam Enoka, who grew up in North Pole before he relocated to California. Enoka maintains his roots through years of involvement with Alaska Center for Energy and Power, a microgrid research group linked to UAF. By partnering with Hewlett Packard Enterprise, his company established the small but powerful-data center in November 2023, co-located with Cordova Electric Cooperative’s Humpback Creek plant.

Chelsea Haisman

An Ever-Growing Cloud

Edge computing, the basis of Greensparc’s business model, brings distributed computation and data storage closer to sources of data. Ten years ago, many Alaska companies had local servers on which their data was housed. Lured by the convenience and relatively low cost of cloud computing, many slimmed down or eliminated their server banks, instead housing that data remotely. The cloud, however, is generally thousands of miles away. For some companies that means a hesitation of a few milliseconds or even a few seconds when accessing data; a price to pay, yes, but less costly over time than maintaining server banks locally.

However, as data is more centralized, the cumulative costs through higher electricity prices—because more power must be generated to meet the data processing demand, along with potential security risks of housing data at a single, large location—add up.

At a panel in May entitled “AI, Grid Integration, and the Energy Transition” at the Alaska Sustainable Energy Conference in Anchorage, Amogh Bhonde, vice president of digital solutions for Siemens Energy, shared concerns about the evergrowing demand for places to house and process data.

“Data centers are expected to be almost one-third of the US electricity consumption in the next four to five years,” Bhonde told the audience. He cited an example of Georgia Power, the primary power producer in that southern state. The company boosted its demand projections by a factor of sixteen due to the added load to its grid from data centers, advanced manufacturing, and artificial intelligence (AI) firms setting up shop in Georgia.

Enoka, attending the same conference panel, noted that the problem is getting larger. Amazon Web Services, Google, Meta (Facebook’s parent company), Azure (Microsoft’s cloud platform), and other companies are demanding—and building—more and more data storage space. “The tier-one markets in the Lower 48 are out of power; that is now the binding constraint. You can’t build those hyper-scale data centers in those markets,” Enoka said.

The commute to the data center involves a fifteen minute boat ride from Cordova Harbor to the Humpback Creek Hydroelectric Project.

Chelsea Haisman

Located about 6 miles northeast of Cordova Harbor, Humpback Creek is one of the only hydroelectric plants in the country that is unfenced and open to the public (for anyone with a boat).

Chelsea Haisman

But the drive to digitize everything, from manuals for a 1995 treadmill to an app for a local sandwich shop, isn’t going away. If anything, the drive toward incorporating AI into more basic functions is moving society toward more data crunching.

“While there is no silver bullet, I firmly believe that software can help,” Bhonde said. “It’s ironic how the problem that we’re trying to solve was created primarily by AI—namely data centers—and we’re using AI to actually fix that problem.”

Bhonde noted that AI, while requiring more data processing, can also analyze weather patterns to manage energy grids over a four- or eight-hour horizon; predict system failures, saving costs on preventive maintenance; and protect energy infrastructure by detecting cyberattacks in anomalous behavior patterns. It can collect valuable institutional knowledge from a longtime employee, interviewed before retirement, to create an AI co-pilot who

can assist a new employee with the complex job of running a power plant.

A plant that powers the AI that helps run the plant that powers the AI that helps run the plant that powers the AI, and on and on.

The Draw of Regional Data Centers

To break the cycle, Enoka believes edge computing is part of the answer.

Instead of making huge data centers in mid-sized cities and requiring power providers to build larger plants to meet those demands, edge computing could create a network of smaller, powerful data centers in smaller towns. Those would provide more reliable data storage and processing to rural areas while also making use of power margins—the unsold and sometimes renewable power that small power providers make that, because of their small consumer base, is “spilled” or unused.

“When I explained our concept to Amazon, for instance, they understood what we’re trying to do. When you order an Amazon package, a truck with an Amazon logo shows up a few days later, and a person with an Amazon uniform gets out of that truck and delivers that Amazon package to your door,” Enoka explains. However, “That’s not Amazon; that’s a local distribution company that [it] contracts with. That employee is not an Amazon employee; they just d o the distribution.”

By analogy, Enoka says Greensparc is seeking to be the data center distributor to local markets, providing users with better, closer data infrastructure so they get better service. Users don’t choose where the data is coming from; the backend process is invisible. But using a local data center would support more responsive and reliable cloud-based services.

Chelsea Haisman

Cordova Embraces Innovation

Clay Koplin, CEO of Cordova Electric Cooperative (CEC) quickly understood the potential of having a local data center.

“It’s the intersection of energy, data, and telecommunications,” Koplin says. “The more data you store and process locally, the less you have to shift over telecom networks. The more renewable energy is available, the more you can fluctuate your data services. There’s a lot of opportunity.”

Koplin also grew up in Alaska, on his family’s farm in Soldotna. His father was an electrician, traveling all over the state to maintain airports. Koplin got an engineering degree and was hired in Cordova when CEC transitioned its power lines underground. The community’s grid has, since 2011, been completely underground, resulting in minimal power outages, which is vital to its

biggest industrial customers: seafood processors, for whom power outages can spell hours of interrupted work time.

Koplin notes that CEC in 2023 generated about 75 percent of its power through two run-of-river hydroelectric plants—the Humpback Creek plant, installed in 1991, which provides about 10 percent of the community’s power, and Power Creek, installed in 2002, which provides about 65 percent of its power. The remaining power is provided by the Orca diesel plant, which is about forty years old. CEC is in the process of upgrading the Orca plant, going from one large, inefficient generator to two smaller and more efficient ones. Three-quarters of CEC’s diesel generated power is used in winter, when the community can’t tap the hydroelectric power; the remaining 25 percent of the diesel power generated is used for peak usage in summer, when seafood

processors place more demand than the hydro plants can supply.

CEC has a state-of-the-art battery storage system as a spinning reserve and cushion for the power load swings. Using creative management, Koplin says it has been able to coax more than 7 MW out of its 6 MW plant. CEC hopes to create a 70-foot dam at Humpback Creek to enable year-round hydroelectric capability, dramatically reducing its reliance on diesel.

Reliable and competitive electricity rates in Cordova have motivated some seafood processors to move processing facilities onshore there, Koplin says. It’s not gone unnoticed: CEC was the only electric cooperative in the United States featured in a thirty-film documentarystyle series the British Broadcasting Company created called “Humanising Energy,” which showcased innovations from across the energy ecosystem.

Koplin says, “Outsiders look at Cordova and they get excited by the

Greensparc uses power from Cordova Electric Cooperative, and in exchange the utility is the data center's first customer, hosting its cloud-based administrative software locally instead of in Seattle.

Chelsea Haisman

Below, Sam Enoka points to the cooling system on top of the cabinets. About 40 percent of power consumption for a typical data center goes toward keeping the electronics at a stable temperature.

Chelsea Haisman

renewable energy and the technology that we use and the innovation. The exciting thing is, we have been able to deliver some of the most reliable energy—we have very few outages— and still support the seafood industry. Our seafood industry has moved onshore to take advantage of our reliable and relatively low-cost energy.”

Soaking Up the Surplus

Aside from peak summer power, Koplin says CEC frequently generates more renewable electricity than the community can use. That’s where Greensparc comes in.

“We spill excess hydropower a lot of the time. We’re now, as we talk, spilling over a megawatt of excess power. We’d rather sell that to someone,” he said in June. “[Greensparc] can manage their use of the energy in concert with our ability to produce it.”

Greensparc’s servers, if CEC were powering them all the time, would require about 5 percent of the cooperative’s energy sales. Koplin told the panel at the Sustainable Energy Conference, “This is a market for us to sell and generate more revenue against fixed costs, keeping rates for the rest of our customers down while bringing these new tools into the economy.”

He compared Greensparc, and distributed data centers generally,

Enoka (left) and Koplin (right) stand in front of the spigot that returns water from the data center cooling system back into Humpback Creek.

Chelsea Haisman

Koplin (left) and Enoka (right) stand on the walkway from the Humpback Creek generator to the run-of-river dam. A string of cables was added last fall when the data center was installed.

Chelsea Haisman

to an anchor tenant that props up other investments. As Koplin put it, “I mean, if you can’t quite get over the hump with a solar farm, maybe having a data server that can take that extra load helps you monetize that, lets you overbuild your solar. Then you get to decide as a community: do we need the energy more, the data more, or some optimal mix?”

Don’t Forget the Data

While the decentralized data center is a focal point, and marketing its capacity to data consuming giants might allow Greensparc to expand around the country, the advantage of a local data system should not be left out of the picture.

CEC is a Greensparc customer because Koplin saw the benefit to having the utility’s highly automated system function locally, not subject to potential outages at an Outside data center or vulnerable to cyberattacks. He can see a range of other local computing possibilities, he says, such as a dashboard for Alaska Department

of Fish and Game managers to track res ources in real time.

“The opportunity to sell more excess energy was enough to get us there,” Koplin says of partnering with Greensparc. “But the other opportunities are so much more valuable. This is attracting partnerships and attention, and we’re part of it, here in Cordova, Alaska.”

At a Greensparc demonstration in Anchorage last year, Enoka found a lot of interest from a variety of users. Those discussions have continued as Greensparc has continued to move forward.

Enoka says he hopes to have deployments in Fairbanks, Anchorage, Juneau, and even some Alaska military bases. A data center on the North Slope would make sense, he notes, as it would add reliability to oil field technology. At the Sustainable Energy Conference panel, he suggested co-locating data servers with village airports might make sense too.

“Then, when you get to that village, what else is there? A school? Great. A clinic? Great. Is there some other

industry that could use maybe not AI but basic computing? That asset could be managed at a micro-level, down to kilowatts,” he noted.

“Enterprises are going to be the low-hanging fruit right now. As we tap in and get more exposure to the [US] Department of Defense and those folks, we can demonstrate how we’ll be in the best position to help them out. Not just in places like Alaska, but it translates well to Hawaii or Guam, markets that are difficult to reach and hard to serve,” Enoka adds.

Enoka sees plenty of good business reasons why distributed data centers tapping remote renewables makes sense. “We want to be a self-sustaining business, but the community benefit, the social impact, of setting this kind of business up to serve users in these communities, I think it will be transformative,” he says. “The results will bear out in the coming months and years, but a lot of us—not just us on the business side of this, but folks on the business side and on the user community—are embracing the opportunity.”

Steady as She Flows

Government money pours into run-of-river hydro projects

By Dan Kreilkamp

Earlier this summer, the Southeast community of Angoon came together to celebrate the arrival of new jobs, clean power, stable electricity rates, and a government award of $26.9 million.

The “Thayer Celebration” was an opportunity to recognize the considerable efforts that led to the 850 kW Thayer Creek Hydroelectric Project, now slated for construction on Admiralty Island.

Attendees included representatives from US Senator Lisa Murkowski’s office and the US Forest Service, among other influential parties involved in the project’s conception.

“The community has rallied around this project,” says Jon Wunrow, project manager for Angoon’s village corporation, Kootznoowoo.

“It’s a great example of a federally

recognized tribe, a rural Alaska community, a village corporation, and the federal government working really well together.”

With a $34 million price tag, Thayer Creek is just one (albeit glistening) example of many energy infrastructure improvement projects across Alaska that are receiving a pivotal source of funding, some of which have been decades in the making.

In terms of government funding, Alaska finds itself in a modern gold rush. Key programs from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 have created a generational opportunity for energy improvements—particularly for rural or remote communities. And those tasked with guiding the state to a more stable, sustainable energy future aren’t taking the flow of funds for granted (so to speak).

Tall Order

Identifying viable energy improvement projects is the easy part; Alaska has long been touted for its massive renewable energy potential. But realizing these projects—from writing the grants to obtaining the necessary permits and then securing the millions of dollars in matching funds—is a far cry from a straightforward process.

Just look at the Susitna-Watana Hydro Project, says Jacob Pomeranz, a senior electrical engineer with Anchorage consulting firm Electric Power Systems (EPS). He’s been orchestrating energy infrastructure projects across the state for the better part of twenty years, and the Susitna dam has been on the drawing board the whole time.

Indeed, the 600 MW Susitna-Watana hydroelectric dam has been a dream since the ‘60s. If built, it would be the

John Pennell

second-tallest dam in the United States. In the midst of federal prelicensing studies in 2016, state funding for Susitna-Watana was vetoed, partly due to the oil price crash and partly for environmental reasons. Had the $5 billion project remained funded, proponents anticipated enough power to satisfy more than half of the Railbelt’s energy demand alone.

“This is something that has been tossed around for a while but never received funding,” says Pomeranz. “The state was teetering on it, everyone would get fired up and go back and forth, but ultimately it never happened.”

Which is unfortunate, he explains, because hydropower projects typically possess a 100-year project life, whereas other plants—like natural gas, for example—are closer to twenty or tnirty years.

“So the hydro plant would pay for itself in the first thirty years, and then you’d have another seventy of making money,” he says, pointing to the Bradley Lake Hydroelectric Plant near Homer as a good example of a hydroelectric project that paid off its debt and now serves as an economic driver.

In many ways, the Susitna-Watana project can be seen as a microcosm of Alaska’s complicated relationship with renewable energy projects: financially, politically, and in technical execution.

The private investment matching requirements in government grants often prove to be a stumbling block, or in some cases an outright barrier.

Pomeranz recalls a recent grant that his team were encouraged to apply for, but the private investment match totaling a cool $100 million proved too costly.

Access Infrastructure

While there’s ample opportunity to tap into Alaska’s renewable energy resources, the infrastructure is lacking.

“The biggest thing for Alaska in terms of our available renewable energy sources is that we don’t have the infrastructure there to connect them,” says Pomeranz. He points to the Rural Electrification Act of the ‘30s as an example of what government measures could be taken to address this. “As part of Roosevelt’s New Deal,

“I think we’re getting caught up, and a lot of people around the state are putting in a lot of hours to make sure that the state and its communities receive maximum funding.”

Jacob Pomeranz, Senior Electrical Engineer, El ectric Power Systems

CROWLEY FUELS ALASKA

With terminals and delivery services spanning the state, and a full range of quality fuels, Crowley is the trusted fuel partner to carry Alaska’s resource development industry forward.

Unlike conventional hydroelectric dams, run-ofriver designs impede the stream flow as little as possible. By siting the project at natural change in elevation, usually at a bend in the river, the artificial detour taps the energy without creating an upstream reservoir or a barrier to fish passage.

US Department of Energy

they pumped tons of money into making sure that everybody in the United States had power. I mean, they had distribution lines in the Lower 48 that ran miles just to a single guy in a farm.”

The Thayer Creek project reflects this reality all too well. A large portion of its funding will be allocated to the complex engineering and construction involved in accessing the creek situated seven miles from town and then transmitting electricity back to Angoon.

“That’s why this is a $34 million project,” Wunrow says. “If it was just putting in the hydro, it would probably be closer to a $6 million project. Getting to the water and getting the power back to the community—that is the expense.”

The fact that such a massive sum is being allocated to a town with a population smaller than your average American high school isn’t lost on Wunrow. However, he’s careful to note that Thayer Creek’s power production will far exceed Angoon’s current needs—by more than three times, according to DOE estimates— providing ample opportunity for

future economic development and infrastructure upgrades.

Shortcut to Energy

One of the reasons SusitnaWatana was never executed, apart from its daunting scope, was concern about environmental damage from interrupting the flow of the fourthlongest undammed river in the country. Thayer Creek avoids that obstacle (almost literally), which helps explain why its construction is a cause for celebration.

When Thayer Creek wraps construction in 2028, it’s expected to supply 99 percent of Angoon’s energy needs, displacing an estimated 120,000 gallons of diesel annually and providing its 400 residents with clean power and stable rates for years to come. That’s one environmental benefit, common to most hydropower.

Better yet, unlike many other hydroelectric dams, Thayer Creek’s run-of-river design takes advantage of the creek’s natural elevation—often referred to as “head”—ensuring minimal

impacts to Admiralty Island’s natural ecology. Instead of artificially elevating the creek level and harnessing power as gravity pulls the water downhill, the generator is placed at a bend in the river, where a shortcut channel taps part of the downstream flow.

“Run-of-river is a really, really great way to generate hydro because the water gets diverted but it still flows,” Wunrow says. “And there’s all kinds of things that are engineered in to make sure that it doesn’t have an adverse effect on fish or marine life.”

Wunrow says there were other creeks that may have been in contention, but none quite had that perfect combination of head, flow volume, and reflection of Kootznoowoo’s values as Thayer Creek. “It’s no coincidence that they [Angoon] decided on run-of-river. It’s part of a bigger stewardship mentality.”

A Promise to Keep

Thayer Creek’s journey to funding has been particularly unique, Wunrow admits.

Back when the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) was being enacted, elders and community leaders from Angoon traveled to Washington, DC, to meet with congressional members and thenPresident Jimmy Carter.

“Leaders of Angoon went to DC and said, ‘We love the idea of preserving the land we’ve been using for 10,000 years—but we want a couple of things in return,’” says Wunrow.

One of those things, eventually included in ANILCA, was a single sentence that read: Kootznoowoo is granted the right to develop

hydro power in the Admiralty Island National Monument.

“And that’s all it says,” Wunrow says with a laugh. “There’s nothing about exactly where, or what that means. But the truth is that the leaders of Angoon at the time had enough foresight back then to say one of the things we want is low-cost, sustainable energy.”

Fast forward a few decades, and it looks like Angoon’s leaders may finally have their wish.

With combined financial outlays from the DOE Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED), the Alaska Energy Authority, the US

Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Inside Passage Electric Cooperative, and two separate contributions from the Denali Commission—Thayer Creek has its green light.

“This is a four-year project. There’s nothing that’s going to stop us from moving forward now,” says Wunrow, who is also the corporation’s tourism and natural resources director.

Wunrow stressed the, in some instances, unlikely partnerships that Kootznoowoo cultivated along the way.

“Historically, the Angoon Community Association have had a challenging relationship with the federal

“Run-of-river is a really, really great way to generate hydro because the water gets diverted but it still flows… And there’s all kinds of things that are engineered in to make sure that it doesn’t have an adverse effect on fish or marine life.”

Jon Wunrow, Director of Tourism and Natural Re sources, Kootznoowoo

Your business solutions start here

• Bill Pay to automate regular payments

• Merchant Services to accept debit or credit cards

• Positive Pay to help prevent check fraud

• Business Remote Deposit to save you time

Call 877-646-6670 or visit globalcu.org/business to talk to a specialist today!

Kootznoowoo

government in general, and the Forest Service specifically,” he explains. “The village is now surrounded by land that they no longer have any control over, and that’s been a challenge for the community to grapple with.”

In this case, though, less so. “I say this to everybody I have a chance to: the US Forest Service have been 100 percent behind Thayer [Creek], and they have literally moved mountains to help us through the permitting process,” says an energized Wunrow, revealing how the US Forest Service helped save the project millions of dollars in timber cutting fees and other costs.

Federal Spread

Wunrow also recognizes the strategic legislative efforts from Senator Murkowski’s office. In the past, the Thayer Creek project couldn’t pursue other DOE funding opportunities because they explicitly prohibited hydro dams. “We couldn’t get around it. Even though we kept saying, ‘Runof-river is different; it’s not what you think!’” he recalls.

That situation changed thanks to the 2021 infrastructure law. Wunrow says, “This OCED funding that we got, I think there’s a couple of sentences written into that legislation that specifically targets run-of-river, remote rural Alaska—and that has everything to do with Senator Murkowski’s office.”

The same announcement in March that Thayer Creek had been selected for DOE rural infrastructure money also spread some more around Alaska. Five projects split $125 million. The

largest share, $54.8 million, goes to the Northwest Arctic region for solar, battery storage, and heat pumps, and $26.1 million goes to seven Interior villages for a similar setup.

Two other run-of-river hydroelectric projects received funding as well.

The Alutiiq Tribe of Old Harbor was allocated $10 million, and the Lake and Peninsula Borough was given $7.3 million for run-of-river hydro at Chignik Bay.

Meanwhile, last year a study by Dillingham-based utility Nushagak Cooperative completed initial field studies for run-of-river hydro on the Nuyakak River, a tributary of the Nushagak in the world’s largest red salmon watershed. Work on that project continued this year with a public survey, to be published in December.

Learning Quickly

As Alaska continues to navigate its energy transition, it’s important to consider the broader context in which projects like these operate.

Introduced in 1984, Power Cost Equalization (PCE) plays a major role in making energy affordable for rural Alaska communities. Historically, this state-funded program has subsidized the high cost of electricity by covering the difference between local energy costs and the average cost in urban centers. This subsidy is vital for economic viability of remote communities.

However, integrating renewable projects such as Thayer Creek introduces a new dynamic. PCE

subsidies are traditionally based on fuel usage, Pomeranz explains. Thus, as communities shift to renewable energy and reduce their reliance on diesel, the amount of PCE they receive would theoretically decrease.

Independent power producers (IPPs) are a workaround solution. By creating IPPs, communities can sell power back to utilities at a reduced cost, effectively leveraging the benefits of renewable energy without reducing their PCE subsidies. IPPs ensure that the economic advantages of PCE are preserved while communities transition to more sustainable energy practices.

Pomeranz stresses the importance of these partnerships, along with the creative measures Alaska’s energy leaders are taking to ensure its rural communities don’t get left behind.

“Right now, if you want funding for a project, you need a group or partnership with multiple entities,” he says. “And what the government is really looking at is putting together projects that are a consortium of community members—including tribes, nonprofits, and utilities—to come together to create a sustainable energy future.”

As with any landmark legislation— what US Representative Mary Peltola called a “once in a lifetime” opportunity for energy infrastructure—there’s always a learning curve. When asked about the time it took for the state to understand what was available and who was eligible, Pomeranz says, “I think we’re getting caught up, and a lot of people around the state are putting in a lot of hours to make sure that the state and its communities receive maximum funding.”

Pomeranz and EPS have not yet played a role in the Thayer Creek project, but that may change when the engineering and construction aspects go out for bid in 2025. And if Wunrow’s experience is anything to go by, it’s not the worst way to put in the extra hours.

“There are so many things I do with Kootznoowoo that are not as fun,” Wunrow says with a laugh. “But with this one, I know I can get on the phone— with the Forest Service or OCED or the mayor or whomever—[and] we’re all talking about the same thing and heading in the same direction. And that’s just rare.”

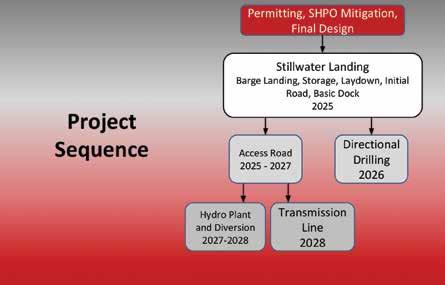

Once construction commences on the Thayer Creek Hydroelectric Project, the expensive parts come first: access to the site.

At Santos, we are proud to develop the world-class Pikka Project on the North Slope. Phase 1 will develop about 400 million barrels from a single drill site with first oil expected in 2026. And we are even prouder that our interest in Pikka will be net-zero on Scope 1 & 2 emissions!

Cold Water, Warm City

The Seward Heat Loop Project

By Rachael Kvapil

Th e Seward Heat Loop Project is a unique alternative energy system firmly rooted in geothermal science, a concept that may sound like something out of science fiction. This innovative project, which has been in development for nearly a decade, combines tidal energy, gravel deposits, and thermal gradients to heat entire buildings. If successful, this demonstration project has the potential to revolutionize energy systems in other communities with similar natural resources.

Go with the Flow

In a nutshell, the Seward Heat Loop Project reduces the reliance on heating oil and electric heat in four city buildings by using a ground-source carbon dioxide (CO2) heat pump. Groundsource loops derive heat from a closed loop of vertical boreholes at Waterfront Park adjacent to Resurrection Bay. Tidal movements are key to providing an initial heat source: an influx of warm seawater from the Alaska Coastal Current flows into the bay each fall, then the North Pacific Gyre heats this

current during a three-year circuit along the equator. Due to this influx, Resurrection Bay remains ice-free year-round. During winter months water temperatures can reach 50°F in November while the air temperature is 22°F, frequently causing steam.

Andy Baker, founder and owner of YourCleanEnergy (YCE), is the designer who conceptualized the unique combination of heated water from Resurrection Bay with heat pump technology to heat an entire building. In 2012, Baker designed and installed

Sam McDavid

a heat pump system using a synthetic refrigerant known as R-134a; however, Baker quickly replaced R-134a with CO2 to eliminate the synthetic refrigerant’s environmental impact.

“Synthetic refrigerants contain PFAS [per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances] fluorination compounds that eventually leak from the heat pump circuit into the atmosphere,” says Baker. “By using CO2, we are preventing super greenhouse gases from rising into the air and ending up in the water.”

Resurrection Bay already heats one building complex in Seward: the Alaska SeaLife Center. However, the Seward Heat Loop Project proposes a different configuration. The center pumps seawater directly from Resurrection Bay into a heat exchanger, but the Seward Heat Loop Project relies on the thermal mass of the seabed. Vertical loops will be inserted into 200 feet of gravel that is saturated by Resurrection Bay, resulting in a consistent temperatures of 45°F. A mixture of water and propylene glycol will be piped down the hole and back up to the surface, collecting tidal and groundwater heat

along the way. The mixture is then piped to the heat pumps, which turn CO2 from a liquid into vapor. The vapor is then compressed to nearly 2,000 pounds per square inch, adding significantly more heat. The hot vapor circulates through a gas cooler that transfers much of its heat into a 100°F hydronic loop that is heated up to 194°F. The 194°F hydronic water leaving the heat pumps is blended into a large building loop that is kept at 140°F to 160°F and further distributed to Seward’s library, city hall, the city annex, and the fire hall.

“Pumping seawater directly into the heat exchanger is high maintenance because saltwater is corrosive,” says Baker. “Using the tidal flush in deep gravel is a novel approach to heating buildings in coastal Alaska.”

They Said Yes

When first proposed in 2015, the Seward Heat Loop Project acquired $725,000 in grant funding from the Alaska Energy Authority. The design process continued through 2019, when the project stalled due to COVID-19, multiple changes in city

managers, budgetary constraints, and necessary adjustments to the project's concept and scope. In 2022, the City of Seward formed an ad hoc committee under the Port and Commerce Advisory Board (PACAB) composed of community volunteers to help find funding and develop a shovelready design. The PACAB Heat Loop Committee is one of five organizations that make up the Community Coalition Team involved with the development of this project. Additional members include the City of Seward, YCE, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, and the Alaska Vocational Technical Center (AVTEC), a state-run industrial training school in Seward.

Within six months of its formation, the Community Coalition Team won a highly competitive US Department of Energy (DOE) grant for $315,000. Out of fifty applicants, DOE selected only eleven projects for Phase 1 funding, which takes a project from concept to the point that it’s ready for construction. In September, the team will apply for $3.8 million in Phase 2 DOE funding for construction. In this round, the Seward

Heat Loop Project will compete with ten other projects, of which three to six will be selected.

“We are dedicated to bringing renewable energy to Seward,” says Mary Tougas of the PACAB Heat Loop Committee. “Andy’s design is such a genius idea. It’s such a simple concept that it makes you smack your head and ask, ‘Why didn’t we think of it sooner?’”

The decision to heat only four cityowned buildings is mainly for funding purposes. Projects that benefit the public have a better chance to meet the grant criteria, so the team chose four public buildings in close proximity to one another with the most usage.

Baker says making this project 100 percent public avoids inequities that could arise from creating a conventional heating district project.

“This is a demonstration project that could be expanded at some point in the future if we are successful,” says Baker.

The construction cost was estimated at $4.5 million when initially proposed in 2015. In 2022, the committee increased the cost estimate to $4.7 million for the DOE grant application. There are several reasons for the increase. Costs for materials and labor have gone up since the project started. Several addons, like heated sidewalks in front of the library, weren’t in the original proposal

but are features community members would like included in the final project. Given all the factors, Baker hesitates to speculate on the construction cost without the final review of an estimator.

“For DOE, it’s not just about the cost,” says Baker. “This is a new process, so installing it is more costly at first. It becomes more affordable as more people adopt it and we find ways to make it more scalable.”

A Penny Saved...

As the founder of YCE, Baker’s primary focus is developing alternative energy processes that decrease environmental impact. However, he is business savvy enough to know that a project isn’t going to succeed if it isn’t economically viable. According to the final design memorandum, heat pumps at the Alaska SeaLife Center have already proved beneficial. Even though the original heat pumps used the synthetic R-134a refrigerant, the system still reduced the center’s use of heating oil by 48,104 gallons, with a net CO2 emission reduction of 420,000 pounds and produced a financial net savings of $120,000. Since replacing the synthetic refrigerant with CO2, the SeaLife Center has produced net energy savings of $135,000 and reduced CO2 emissions by 1.3 million pounds.

The memorandum also outlines the increasing cost of heating oil for the four buildings chosen for the Seward Heat Loop Project. In FY13, after the library was built, the total cost for heating all four buildings jumped to $67,605. In FY14, the price dropped slightly to $57,031 due to a global oil price crash. The library currently has an electric boiler installed as an alternative heating method; however, the oil-fired boiler is still a more cost-effective heating source. By using a ground-source CO2 heat pump system, the city estimates a 62 percent reduction in heating costs for the library compared to the existing electric boiler. For all four buildings, the reduced heating costs are estimated at around 52 percent compared to using existing heating boilers, at heating oil prices of $3.99 per gallon.

“We have few cost-effective, environmentally friendly options to heat our buildings here in Seward,” says Tougas. “Other than heating fuel, we have electricity, firewood,

YourCleanEnergy founder Andy Baker (left), who designed the Seward Heat Loop Project, crunches the numbers with geothermal HVAC researcher Saqib Javed (right) of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Sam McDavid

Saqid Javed (left) and Karlin Swearingen (right) from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory visited Seward in May to collect data to model the heat loop system for the final design.

Sam McDavid

and a small amount of propane. We don’t have natural gas.”

Electricity from the primary grid still powers the heat pump system; however, the committee has identified solar panels as a clean energy source for this purpose. This addon is not in the original proposal and depends on what DOE approves in the upcoming grant submission.

Future Workforce for Future Technology

Among a list of requirements, the Phase 1 DOE grant includes an allocation for workforce development. The PACAB committee used grant funds to purchase a SanCO2 residential heat pump, which employs the same carbon dioxide heat pump technology as the ones used in the proposed heat loop, for training purposes. Instructors from AVTEC are crafting a curriculum based on a recent intensive training and certification course with the system’s codesigner earlier this year.

In a committee press release, AVTEC Director Cathy LeCompte expressed her excitement about the opportunity to

weave this new training curriculum into the center ’s existing program.

AVTEC is a division of the Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development that provides postsecondary workforce training that is flexible, accessible, affordable, and responsive to the dynamic needs of business and industry and serves Alaska’s diverse communities. AVTEC delivers training statewide in refrigeration, plumbing and heating, information technology, industrial electricity, construction technology, business and office technology, and more. A course in operating and maintaining the heat loop in Seward and future deployments will fit perfectly into AVTEC’s structure.

As the Community Coalition Team works on the final requirements of the Phase 1 DOE grant, there is much optimism going into the Phase 2 application process.

“The design system used in this demonstration project has the potential to benefit all coastal communities in Alaska,” says Tougas. “We look forward to the next stage and beyond.”

“We have few cost-effective, environmentally friendly options to heat our buildings here in Seward… Other than heating fuel, we have electricity, firewood, and a small amount of propane. We don't have natural gas.”

Mary Tougas Recorder

PACAB Heat Loop Committee

Volcanic Rumblings

Geothermal grid power seems closer than ever

By Joseph Jackson

Geothermal energy exploration is picking up steam in Alaska—literally.

In the last three years, the Alaska Department of Natural Resources (DNR) has issued several geothermal exploration permits for use in the Aleutian Arc. One of these applies to the previously untapped Augustine Volcano in Lower Cook Inlet. Meanwhile, the Makushin Geothermal Project near the city of Unalaska is restructuring.

Taryn

Neither the DNR exploration permits nor the Makushin project are new endeavors; lease sales have been held in the Aleutian Arc, particularly on the stratovolcano Mount Spurr, since 1983, and the Makushin project has been in the works since 2020. However, there’s reason to believe that these more recent developments are better poised for success.

The federal Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 provides new incentives for geothermal development, such as tax credits up to 30 percent through 2032. In May, the Alaska Legislature passed House Bill 50, which mainly relates to storing carbon dioxide deep underground on state lands, but it was amended to include language specific to geothermal exploration. Governor Mike Dunleavy had requested legislation to extend the length of geothermal exploration permits from two years to five.

The US Department of Energy estimates that 8.5 percent of the country’s electricity could be generated by geothermal power by 2050, and more than 28 million homes could be heated and/or cooled by geothermal heat pumps. Alaska, given its location in the geologically active Ring of Fire, remains a focal point for advancing such technology.

Bubbling Up

The premise of geothermal energy is to use the Earth’s inner heat—usually by producing and moving steam— to generate electricity. Paul Craig, president and CEO of Anchorage-based GeoAlaska, jokes that geothermal is one of the only industries in which “the goal is to get into hot water.”

A compelling virtue of geothermal is that it’s considered a baseload energy source, says Craig. Unlike other renewables such as wind or solar, which are intermittent, geothermal can continually meet the minimum necessary demand for an electrical grid

Heat’s not the only concern, though. According to Guy Oliver, director of geoscience and exploration at Ignis Energy (a sister company to Geolog, one of the largest geothermal development companies in the world), an exploitable geothermal resource must meet a few other requirements

in order to be successful: sufficient flow rates to extract the resource to the surface (for power production) and proximity to an accessible market.

Currently, two volcanoes in the Aleutian Arc may fit the bill.

The first is, of course, Mount Spurr, an 11,070-foot stratovolcano approximately 80 miles west of Anchorage; and the second is Mount Augustine, another stratovolcano 4,134 feet tall, occupying an island roughly 60 miles southwest of Homer.

Both resources are close to the Railbelt grid, the area between the Kenai Peninsula and Fairbanks that supplies about 75 percent of Alaskans with electricity. Declines in other Railbelt energy resources—such as Cook Inlet natural gas, which is expected to face a serious decline by 2030 according to a 2023 study by the Alaska Division of Oil and Gas—could make geothermal attractive as both an alternative source and a carbon offset.

Spurring Development

Mount Spurr has long been a prospect for supplying a portion of the Railbelt’s power needs. Since 1983, DNR has held four lease sales, each giving developers an opportunity to probe Mount Spurr’s subsurface potential.

In 2008, Nevada-based Ormat Technologies was awarded leases to explore more than 35,000 acres of Mount Spurr’s flanks. Several years of testing proved fruitless, and in 2015 Ormat abandoned its efforts. Currently there are two companies still combing Mount Spurr: GeoAlaska and Cyrq Energy out of Salt Lake City.

GeoAlaska is also exploring Augustine, a resource previously untapped for its geothermal potential. John Eichelberger, a professor emeritus at the UAF Geophysical Institute and pioneer of both the Alaska Volcano Observatory and the Krafla Magma Testbed in northern Iceland, believes that Augustine presents a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. “It’s one of the hottest volcanoes in the Pacific,” Eichelberger says.

GeoAlaska has been gathering geophysical data on Augustine since the summer of 2023. Initial tests suggest that it is worth further study. In March 2023, GeoAlaska partnered with Houston-based Ignis Energy to

Volcano is one

monitored volcanoes in the world, according to the Alaska Volcano Observatory. This makes it much safer to explore for geothermal resources on the island. GeoAlaska has been using magnetotelluric data—a means of measuring subsurface electrical resistivity—to seek out potential geothermal reservoirs.

plan more expansive data collection on Augustine this year.

GeoAlaska has also been proactive in figuring out how to deliver geothermal power, should its exploration prove successful. According to Craig, GeoAlaska entered into an agreement with the Homer Electric Association (HEA) in 2022. While details are confidential, the agreement spurred HEA to apply for and receive grants from the Alaska Energy Authority (AEA) to study electricity transmission from both Mount Spurr and Augustine.

In the case of Augustine, the proposed plan is to transmit power via a submarine cable across Cook Inlet to a power inverter near Anchor Point, which would, in turn, plug into the Railbelt grid. GeoAlaska estimates that Augustine could produce between 50 MW and 100 MW using traditional geothermal methods.

Far-Out Venture

Supplying the grid with clean, baseload energy isn’t the only application for geothermal in Alaska. Small-scale and/or remote geothermal development also has massive potential. Imagine it: off-grid settlements run entirely by endless geothermal energy. No more diesel generators. No more power shortages. Complete energy independence.

One of the most notable examples of this is the Makushin project near Unalaska. The city became interested in the nearby Makushin Volcano as a potential energy source in the ‘80s. Developing the necessary infrastructure, though, proved easier said than done. Fast-forward to 2019, when Bernie Karl stepped in. Karl is credited with not only building the now world-famous Chena Hot Springs Resort from the ground up but with introducing the first geothermal power generator to the state of Alaska in 2006.

In 2020, Karl’s Fairbanks-based Chena Power teamed up with Unalaska’s Native corporation, the Ounalashka Corporation, with the lofty goal of designing, building, and operating a 30 MW power plant to harness Makushin’s energy. The project carried an estimated price tag of $250 million and was expected to be completed in 2024.

As a joint venture, Ounalashka Corporation/Chena Power (OCCP)

Augustine

of the best

Esther Babcock | Logic Geophysics & Analytics

GeoAlaska believes that Augustine Volcano harbors major potential for Alaska geothermal energy.

M.L. Coombs | Alaska Volcano Observatory | UAF Geophysical Institute

GeoAlaska began conducting geophysical surveys on the south side of Augustine Island in 2023.

Paul Craig | GeoAlaska

made good headway: it entered into a thirty-year Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) with the City of Unalaska in 2020, signed an intent to award the engineering construction contract to Ormat in 2021, and secured $2.5 million in federal funding in 2022, along with a $5 million funding commitment from AEA in 2023.

Shaking and Quaking

Unfortunately, progress slowed due to supply chain issues and funding difficulties. To combat rising project costs, OCCP sought an increase in the PPA prices from $0.16 to $0.22 per kWh. As of December 2023, the PPA expired, and on March 8, 2024, the City of Unalaska announced that it did not intend to extend or renegotiate the agreement.

But the announcement did not end the Makushin geothermal project. In the same news release, the City stated plans to resuscitate the project in partnership with the Qawalangin Tribe of Unalaska and Ounalashka. It remains unclear how Ounalashka plans to dissolve its former partnership with Chena Power.

On February 1, 2024, the City of Unalaska submitted a letter of intent to apply for a Climate Pollution Reduction Grant from the US Environmental Protection Agency, with the goal of developing Makushin geothermal. The Environmental Protection Agency’s Climate Pollution Reduction Grant program has $5 billion set aside for ambitious projects that seek to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, up to $500 million per project with no local grant match requirement. The Unalaska City Council submitted an application before the April 1 deadline, according to City Manager William Homka. Grant awards will be announced in October.

Homka hopes the Makushin project will be selected. Unalaska is striving to cut out diesel and the costs associated with it, seeking viable alternatives to provide reliable, baseload electricity for all stakeholders— from individual households to Dutch Harbor seafood processors.

Makushin could blaze a trail for other communities to follow, not just to tap geothermal resources but to strive for true sustainability.

“The power is here,” says Homka, and though he refers specifically to Unalaska, his words ring true for the entire state.

Imagine it: off-grid settlements run entirely by endless geothermal energy. No more diesel generators. No more power shortages. Complete energy independence.

Seeing the Light

Solar power under the midnight sun

By Vanessa Orr

Pu tting the role of solar energy into terms Alaskans can understand, Chris Rose draws an analogy. “It’s like fishing in the summer or hunting in the spring and fall,” says Rose. “While you can’t do these things year-round, you harvest what you can when you can so that you have it available when you need it.”

Rose, founder and executive director of Renewable Energy Alaska Project, notes that half of the state’s electricity comes from natural gas, which is becoming a problem. Communities in Cook Inlet are already paying three times more than residents in the Lower 48 are paying for natural gas, and that amount is about to go up. Due to dwindling supplies, Alaska utilities are

looking at importing liquified natural gas from Outside, which is expected to raise costs by 50 percent or more in the next five years.

“Even though natural gas is a local resource, it’s not a cheap resource,” says Rose. “Fossil fuels are expensive and getting more expensive, so if we can generate local power with no fuel costs, there are a lot of advantages to that.”

By using renewable energy most of the year, natural gas can be conserved for use during the winter. To this end, several projects—both at the state and community levels—are underway to harness the midnight sun. Federal funding is also supporting more projects, especially in rural areas, that

could help the state become even more energy independent.

Direct Currency

In April 2024, the US Environmental Protection Agency awarded $125 million to Alaska to build and expand solar energy projects as part of its Solar for All program. Part of a $7 billion program that funds community energy nationwide, Solar for All projects typically enable a group of people (like residents of an apartment block) to invest in solar projects and get credits on their utility bills when those projects deliver power to the electric grid.

The $125 million splits between two projects: $62.5 million was awarded to a partnership between the Alaska Energy

Authority and the Alaska Housing Finance Corporation (AHFC) to fund solar energy infrastructure around the state. Alaska Energy Authority will use the grant for communities seeking to develop solar arrays, including battery storage, and AHFC will administer a program to subsidize residential rooftop solar installations for low-income households.

The remaining $62.5 million was awarded to the Tanana Chiefs Conference, in partnership with the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium and AHFC, to invest in solar energy for thirteen tribal communities along the Railbelt, including Nenana and Chickaloon.

In addition, the US Department of Energy recently funded five Alaska projects through the Energy Improvement in Rural or Remote Areas program, two of which are solar.

The first provides $54.8 million to ensure reliable access to energy and heating for eleven Alaska Native villages in the Northwest Arctic Borough through the planned installation of solar, battery storage, and heat

pump systems. The borough will use this money to install 850 residential heat pumps, or almost one for every home in Ambler, Buckland, Deering, Kiana, Kivalina, Kobuk, Noatak, Noorvik, Selawik, and Shungnak. NANA Regional Corporation is matching $5 million for this project, which builds on previous energy diversification efforts in the region.

The second award, an Alaskan Tribal Energy Sovereignty project, provides $26 million to Tanana Chiefs Conference to expand solar projects in eight tribal communities including Minto, Huslia, Nulato, Kaltag, Grayling, Anvik, Shageluk, and Holy Cross. Instead of relying on diesel generators, solar panels and battery storage would be integrated into each community’s microgrid, a process that is expected to take approximately five years.

The US Department of Agriculture’s Rural Energy for America program provided a $460,000 federal grant in March 2024 to expand a solar power system at Whistle Hill in Soldotna. The final phase of the two-stage project is

expected to be completed this summer by Peninsula Solar, which is installing a 200 kW solar system with 500 kW of battery storage that will have the ability to generate and sell electricity to commercial indoor herb garden fresh365 and three other businesses on site. The annual production of the completed system is estimated to produce enough electricity to power nineteen homes.

Solar by Subscription

In January 2024, Chugach Electric Association (CEA), Alaska’s largest electric utility, filed a plan with regulators to create a 500 kW community solar project in Anchorage. Ratepayers would subscribe and pay the costs to build and maintain the panels, while the cost of solargenerated power would be subtracted from their bills. The 500 kW array, with 1,280 panels, would be built at the CEA substation south of the Dimond Center mall. In February, the Regulatory Commission of Alaska approved the utility’s request for an initial three-year pilot period.

The First Choice to the Last Frontier

Span Alaska connects the world to all of Alaska with a weather-tested network of highway, vessel, barge, rail, and air transportation.

Our non-stop services and 1st-day delivery schedule expedite your products directly from the Lower 48 to one of our six service centers or air cargo terminal for final-mile delivery—without rehandling and costly delays.

• Twice weekly ocean transit—all year in all conditions

• LTL, FTL, Chill/Freeze, and Keep From Freezing protection options

• Specialized equipment for project, oversized, and hazardous materials shipments

• Customized solutions for commercial and industrial sectors, including construction, oil and gas, consumer goods, and retail/tourism

“Renewable energy is becoming increasingly important, particularly with the decline in natural gas production in Cook Inlet… Every kilowatt provided by renewable energy uses one less kilowatt from gas, which can be put into storage for a later time.”

Alaska Senat or Bill Wielechowski

The utility’s first attempt to create a small community solar farm in Anchorage was rejected in 2019.

The CEA program would allow members without their own rooftop solar array, such as renters, to benefit from renewable energy by subscribing to buy power from the solar farm. Under the plan, a member could subscribe to receive power from one panel or up to twenty panels, paying a monthly fee.

The community solar project would generate electricity equivalent to an average of 0.02 percent of CEA’s retail energy sales annually. CEA would own the project, estimated to cost about $2.8 million.

Member applications will be accepted beginning October 1, and construction is expected to be completed by the end of 2024, with the program going live by March 1, 2025.

CEA is also planning to put solar panels on its two major power plants, the Southcentral Power Project near its headquarters along Minnesota Drive and the George M. Sullivan Plant along the Glenn Highway. The projects, which are anticipated to be roughly 100 kW each, will increase the efficiency of the plants and offset the use of natural gas. Solar panels will also be installed as part of a remodel of the operations building on CEA’s South Campus, which will add an additional estimated 165 kW of solar capacity to the system.

Plugged In and Charging

Two recently completed projects are already generating power for communities as well as contributing to the electric grid.

The $2.2 million solar farm at Shungnak, completed last fall, is now generating power for Shungnak and Kobuk. An electrical intertie connects the two villages, located about 10 miles apart on the Kobuk River. The farm on which the 225 kW project sits is owned by the two tribal governments, which enables them to sell the power to the Alaska Village Electric Cooperative, the largest electric utility in rural Alaska. This spring, the solar farm produced so much power that the diesel-fed power plant shut down for several hours a day.

Alaska’s largest solar farm, located in Houston, began operating in September 2023 and is now feeding power to Matanuska Electric Association. The

45 acre, 8.5 MW farm can provide about 5 percent of the utility’s output, powering about 1,400 homes at peak production, for roughly the same cost as gas-fired generation.

Community Action

The Alaska Legislature passed two bills this spring aimed at helping Alaskans access renewable energy.

Senate Bill 152 (SB152) creates a streamlined framework to establish community energy projects in Alaska, including those powered by solar, hydroelectric, and wind. The bill, titled “Saving Alaskans Money with Voluntary Community Energy (SAVE) Act,” enables Alaskans to subscribe to communityowned solar arrays not located on their home or property.