SIGNALS quarterly

FROZEN IN TIME

Conserving Antarctica’s heroic-era huts

WHALING IN AUSTRALIA

The end of a controversial era

TIMBER SHIPBUILDING

A thriving colonial trade

Conserving Antarctica’s heroic-era huts

The end of a controversial era

A thriving colonial trade

AUSTRALIA’S MARITIME HISTORY is intertwined with that of many nations both near and far, and we often work in creative as well as research collaborations with museums from around the world.

One such project, our exhibition On Their Own: Britain’s Child Migrants, will travel to England in October this year, going on show at the National Museums Liverpool before moving in 2015 to the V&A Museum of Childhood in London. On Their Own, which has already travelled to regional venues throughout Australia, explores the shared child-migrant history of this country, the United Kingdom and Canada.

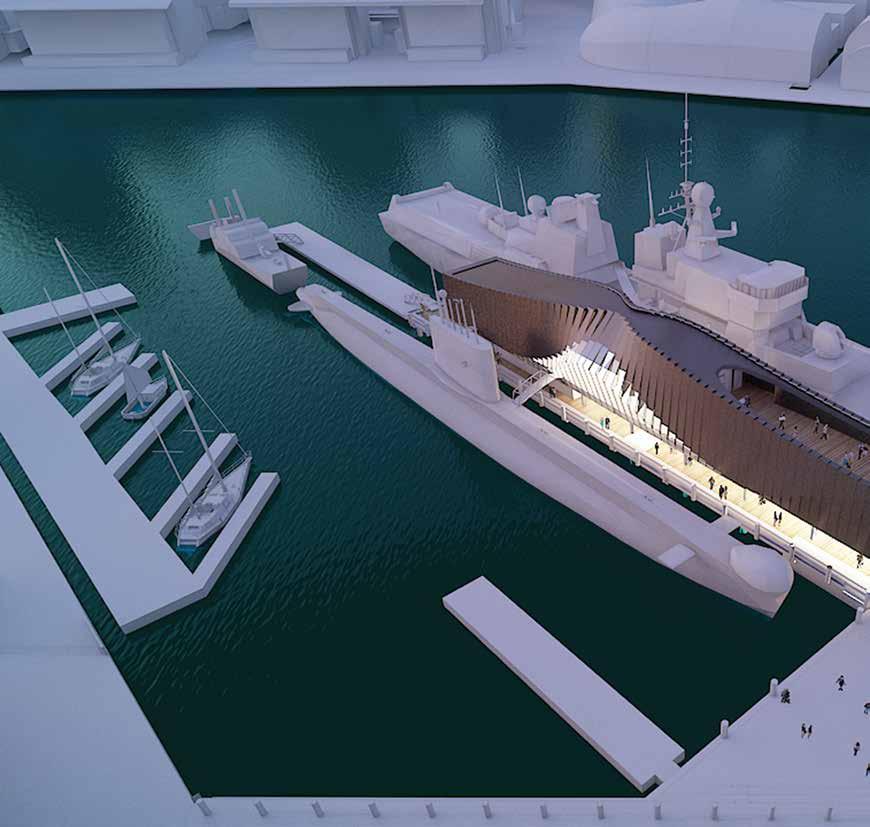

The history of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is another that has been played out all around the globe, in various theatres of war. So the Australian National Maritime Museum has started a new program working closely with the RAN and Department of Veterans’ Affairs, to protect important sites and wrecks overseas. One of these is the wreck off the Turkish coast of the RAN submarine AE2, the only RAN vessel lost to enemy action in World War I.

In June this year the AE2 project team will attempt to deploy two ROVs (Remote Operated Vehicles) inside the submarine to capture video footage, revealing the vessel’s interior for the first time since it was scuttled on 30 April 1915 in the Sea of Marmara, after its pressure hull was pierced by a Turkish gunboat. The project is the result of many years’ work, including the construction of a full-scale replica of AE2 ’s conning tower and part of the hull, which was lowered into Corio Bay in Victoria to test divers and equipment. The museum is working closely with the project and will take responsibility for its archives and its conservation work in 2015, when the project completes its final phase.

Another international collaboration involves arguably Australia’s most famous ship – Lieutenant James Cook’s HM Bark Endeavour. While many of us know about Cook’s work charting the east coast of Australia in 1770, what happened to HM Bark Endeavour following her return to England was, until recently, a mystery.

After Cook’s first Pacific voyage, Endeavour was discharged from the Royal Navy and sold. US archaeologist and historian Dr Kathy Abbass of the Rhode Island Marine Archaeological Project (RIMAP) established that Endeavour (under a new name, Lord Sandwich) was one of 12 vessels scuttled by the British military in Newport Harbour, Rhode Island, in 1778 to protect the port from the French during the American War of Independence.

RIMAP, headed by Dr Abbass, has been diving and surveying this fleet over the last 20 years. The Australian National Maritime Museum’s maritime archaeologists have been actively involved in the hunt for Endeavour ’s remains and have dived on the site five times, most recently in 2007. I travelled to Rhode Island in March this year to meet with Dr Abbass and her team to agree on the next steps in renewing our partnership.

As the museum develops its plans for new galleries, visitors will be able to see the tangible results of these international collaborations. Our new Warships Pavilion will tell the story of both AE1 and AE2, and in 2020, on the occasion of the 250th anniversary of HM Bark Endeavour ’s arrival off the east coast of Australia, we plan to open a major new Pacific exploration gallery.

Kevin Sumption

Museum Director Kevin Sumption with the museum’s HMB Endeavour replica. Photograph Sam Mooy/Newspix. Reproduced with permission

Cover: Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s expedition base from the British Antarctic ( Terra Nova) Expedition of 1910–13. The hut stands at Cape Evans, Ross Island, below Mt Erebus, the world’s southernmost active volcano. Today, the hut contains more than 10,500 artefacts, most of which have now been conserved. The Antarctic Heritage Trust’s on-ice conservation team is treating the final 800 of those artefacts this winter (see story on page 64).

From commerce to conservation: changing views on whales and whaling

War in miniature, depicted in a vivid diorama of Suvla Bay

The rich history of Western Australia’s seagoers and their craft

The thriving trade of timber shipbuilding in colonial New South Wales

Personal tales shed light on Australia’s post-World War II immigration policies

An ambitious building project gets under way at the museum

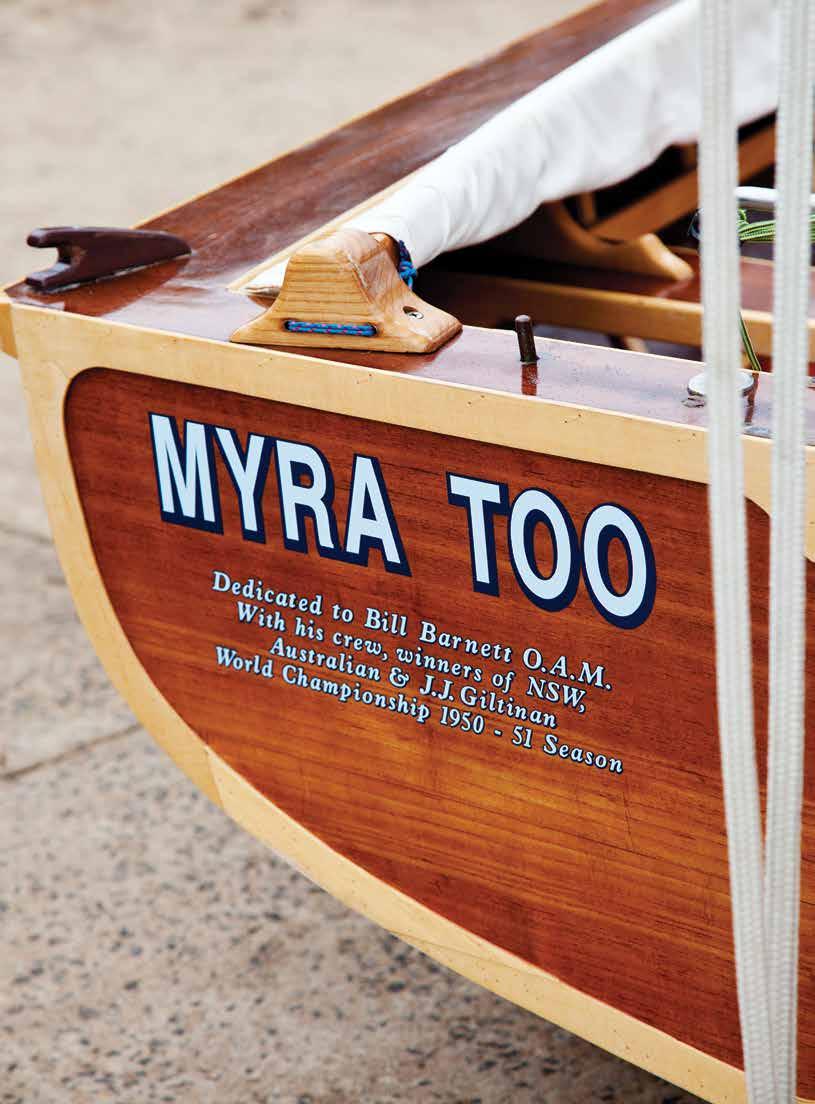

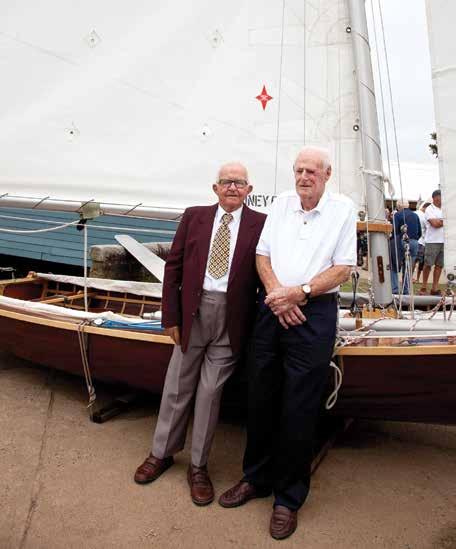

Building a replica of a champion skiff

A new exhibition reimagines the first meetings between Europeans and Indigenous Australians

The museum develops a versatile new waterside venue

The latest exhibitions in our galleries this season

Discovery Bay’s Historic Whaling Station, Western Australia

The master of our Endeavour replica describes what it takes to maintain this unique ship

Conserving century-old huts from the heroic era of polar exploration

Whaleboats, sailboats, Indigenous canoes and a Cold-War submarine

Filipino merchant mariners remembered; a wartime mystery solved; a visit from our poster girl

Arthur Phillip by Michael Pembroke; Natural Curiosity by Louise Anemaat

A famous skiff goes back on the water, and old crewmates reconnect via the internet

A Cheynes Beach Whaling Station vessel, the Cheynes II, as seen from a Zodiac in September 1977, its whale cannon mounted on the bow. Norwegian sealer and whaler Svend Foyn invented the explosive harpoon in the 1860s, leading to the near-extinction of many species of whale that had previously been relatively safe from whalers. ANMM Collection. Photograph Jonny Lewis

Whale oil, and whale bone, remained Australia’s number one export until 1835, when wool took over

When the early settlement of Australia is discussed, the usual focus is our agricultural beginnings and our intrepid explorers of the land. Much less emphasised is our history of whaling and its contribution both to the early economy of the colonies and to the growth of fledgling coastal settlements. Curatorial assistant Myffanwy Bryant looks into this once lucrative and now controversial industry.

AS CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIANS, we embrace our immigrant and convict roots, but seem less inclined to acknowledge our whaling forefathers, those brave and resilient hunters who, in the early days, chased down whales with little other than small wooden boats and a very stout heart. It seems we would rather not see ourselves as one of the great whaling countries of the 19th century. And yet we were. Indeed, Australia had the last operating whaling station in the English-speaking world. It was not until 1978, only 36 years ago, that the Cheynes Beach Whaling Station at Albany in Western Australia closed.

Whaling began in the west of Australia even before there was any substantial settlement. The land in the west was arid and unforgiving, but the sea was rich in marine life, particularly whales. In a century that virtually ran on whale oil, these southern oceans were akin to goldfields, abundant in natural resources that were owned

by no one and ready for the taking. Whale oil powered the great machines of industry during the booming industrial age and lit the lamps of the grand houses and businesses of Europe and America.

The whaling industry literally fuelled the world. So before Australia was ready to export any other goods, whale oil and whale bone provided economic viability. Whaling’s potential for profit led to the establishment of a military outpost at Albany in 1826, needed to protect British interests in the region. Indeed, the governor of New South Wales, Ralph Darling, ordered that if the French were found to be settled there already, they should be told to leave, as Britain now owned the entire continent of New Holland, as Australia was then known. What had begun as sea harvesting by small bands of rogue sealers and passing whalers now grew to include hundreds of local and international whaling ships arriving at onshore whaling stations to feed

the insatiable international market, and so helping to found the economy of Australia’s west. Whale oil, and whale bone, remained Australia’s number one export until 1835, when wool took over – although even with wool leading the exports, there were still some 300 American whaling ships operating off Australia’s west coast.

Inevitably, however, the world began to change; whale numbers were decreasing, and new alternatives such as camphene oil were being more widely used. Across the seas in England and America, attention became focused on something quite different, something that would change the world forever: petroleum. However, the whale industry was not yet at an end. Despite the cheaper and more accessible alternatives available, the high quality and various properties of whale oil were not so easily replaced and the west-coast whaling industry struggled

Tourists visited the Cheynes Beach Whaling Station to watch the flensing of a carcass

01 Flakes of spermaceti, a white waxy substance found in the head of the sperm whale and used for candles and ointments. ANMM Collection

02 A large crowd of tourists watches a whale carcass being flensed at Cheynes Beach Whaling Station in the 1970s. Photograph by Ed Smidt. Reproduced courtesy Ingrid Smidt

03 A sperm whale alongside the whaling ship Cheynes III. Photograph by Ed Smidt. Reproduced courtesy Ingrid Smidt

04 A whale chaser off Albany, Western Australia. Photograph by Ed Smidt. Reproduced courtesy Ingrid Smidt

on even after its east-coast counterpart had given up. Whale oil still had many important uses in the modern world – even into the 1960s whale oil was used in the garment and leather industries and as a lubricant for high-altitude instruments, and some musicians can still recall the superiority of recording tape lubricated by whale oil.

With a market still existing for whale oil, the Cheynes Beach Whaling Station was established in 1952 by some local fishermen. It became an important employer in Albany, and the whalers, despite modern technological advances, were still seen by many as tough, hard-working men. It took great commitment to establish and maintain the station in those early years. The location was isolated and the conditions under which the whalers lived and worked were difficult. The camaraderie, resilience and seamanship involved in whaling had not lessened over the years.

The 20th-century whalers, like their predecessors, had no great love for killing and processing whales. It was, as it always had been, a harsh, labour-intensive and stomach-churning job. But it was a job, and work both before and after the whaling industry was hard to find in such remote towns as Albany. By the 1970s, towards the end of the industry’s reign, Albany had the highest unemployment rate in Western Australia and the Cheynes Beach Station not only provided much-needed work for some, it also supported the town and added to Australia’s export market. At its peak, the company took between 900 and 1100 sperm and humpback whales each year for processing. In 1963, the International Whaling Commission banned the killing of humpback whales due to their dwindling numbers, so the whalers of Cheynes Beach Station had to hunt further afield, solely for the sperm whale.

The station also became an attraction for outsiders. Accounts of touring Western Australia tell of visitors to the station watching the flensing of a carcass. It was the only place in Australia where you could see a whale so close, and despite the gruesomeness of the task, there was interest in watching whalers who were skilled at their jobs and who seemed willing to be seen by the public hard at work.

But again, developments overseas, and throughout Australia, would directly affect this small, remote community

of whalers. This time changes would be aided by a very small band of dedicated people determined to show the world that whaling was inhumane, brutal and unnecessary. This small but passionate group was known as Greenpeace. It was less than 10 years old but had already made an international name for itself by protesting against Russian whaling in the Pacific. This was a new style of activism, in which protesters physically intervened with the ships at sea and put themselves between the whale and the hunters. Greenpeace was media savvy, direct and fearless. It was exactly what local Australian anti-whaling groups, the Whale and Dolphin Coalition and Project Jonah, needed to take the fight directly to Cheynes Beach Whaling Station.

Greenpeace had developed the tactic of using Zodiacs, inflatable dinghies, to follow whaling ships to sea. It is a familiar sight to us today, but in 1977 it was unprecedented. The media attention that followed made a huge impact. It is one thing to tell the public about the brutality of whaling, but another to show the reality on televisions around the world. Protestors against the Vietnam War had realised the power of moving images, and now this new group of eco-warriors used the same technique. By the late 1970s a large proportion of Australians was against whaling and politically it was becoming a difficult industry to defend. Bans and quotas on whaling had been in place since the 1960s, and in the 1970s the Cheynes Beach Station was becoming unviable, both economically and politically. It was the last whaling station in the English-speaking world and its detractors were growing in number.

In 1977, the International Whaling Commission held a conference in Canberra as the debate on whaling in Australia continued. The conference drew further attention to the issue and to Cheynes Beach. Greenpeace and local anti-whaling groups could not have asked for better exposure. In August 1977, some of the founding members of Greenpeace and other local activists started protesting at Cheynes Beach Station. It was Greenpeace’s first protest in Australia and the residents of Albany had experienced nothing like it. For three weeks the protest raged, with the whaling ships constantly hounded by the Zodiacs and both sides defending their position. For Albany, whaling was the maritime heritage on which

A small band of dedicated people calling themselves Greenpeace was determined to show the world that whaling was inhumane, brutal and unnecessary

the town was founded. In addition it was still legal, and brought in much-needed money. It was difficult for locals to accept such interference and condemnation from outsiders, in particular activists from as far away as Canada.

While the campaign at Cheynes Beach Station did end, the argument against whaling did not. By the end of 1978, when the Australian government launched a national inquiry, the last whaling station in Australia had already decided to close. It had become the small, isolated stage where tradition had met activism head on and the new issue of conservation had been highlighted. With the last whale oil still in the enormous tanks, Cheynes Beach Station closed with a final season’s catch of 698 sperm whales. It is said that on the last day of operation, 21 November 1978, the crew spotted a bull sperm whale but decided against killing it. Australia had taken a decisive step towards being the most stringent anti-whaling nation on earth.

Cheynes Beach Station is now a renowned whale museum, Discovery Bay’s Historic Whaling Station (see story page 54), and is on the Western Australian State Heritage List. And while life was difficult for the 100-plus employees of the station when it closed, many are now involved in guiding and running the museum. Paddy Hart, master of the whaling ship that went out

on that last day of the station’s operation, is now a strong anti-whaling advocate. He travelled on behalf of Greenpeace to Japan in 2008 in an attempt to assure the Japanese whalers that there is life after whaling.

Today, ships still pursue whales off Albany, but the people aboard them are armed with cameras rather than harpoons. Whales are part of a tourist industry that brings in more than $140 million per year for the region, employs more than 1,200 people and draws more domestic and international visitors than in any other part of Western Australia. With the local whale population growing at an estimated 10 per cent per year, whale watching has become a highly popular attraction. It brings a new type of whale hunter to Albany; those who want to see these animals up close, to hear them and to admire their enormous size and grace. Like the whaling vessels of the past, out to sea the boats still go, waiting and watching for the tell-tale spray from a surfacing whale’s blowhole. And so it is that three decades after Cheynes Beach Station closed, a new whale industry has emerged in Albany.

01 A Zodiac passes in front of the Cheynes Beach Whaling Station, 28 August 1977. Photograph Jonny Lewis Collection, photographer unknown

UNFORGETTABLE EXPERIENCES

Set sail for the voyage of a lifetime aboard one of APT’s luxurious small ship cruises. You will explore the wonders of the world and life at sea when you venture off the main tourist trail. Whether it’s cruising the Kimberley coastline, exploring the coast of Norway or discovering the ethereal Antarctic Peninsula, you will get up close and intimate with the ocean’s magnificent marine mammal; the whale. From humpbacks to orcas, whale watching aboard your luxury small ship cruise is bound to be a truly breathtaking experience, a memory which will stay with you always.

ü INCLUDED – Luxury small group journeys aboard the MS Caledonia Sky, MS Island Sky or Sea Explorer

ü INCLUDED – All shore excursions, sightseeing, tipping, airport transfers and port charges

ü INCLUDED – Exquisite onboard dining as well as wine, beer and soft drink with lunch and dinner on cruise

ü INCLUDED – Zodiac landing craft for a true exploration of remote sights

ü INCLUDED – Guest Speakers or Expedition Team

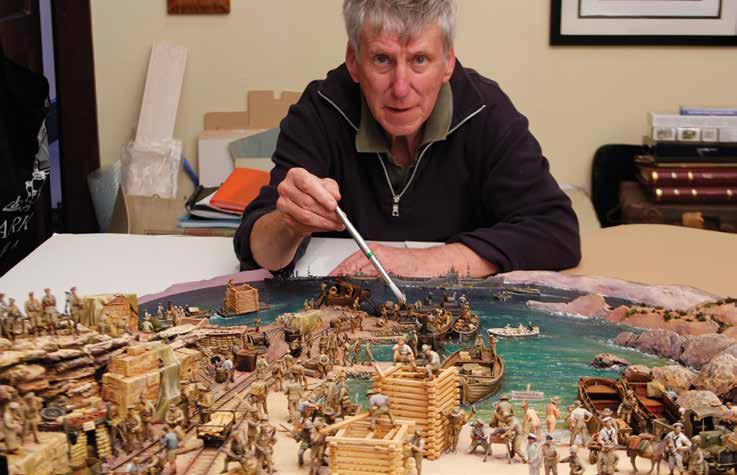

The Gallipoli campaign of World War I owed much to the efforts of the Royal Australian Navy Bridging Train – the landing of supplies and ammunition, the removal of casualties, and the eventual evacuation of all Allied troops from the Dardanelles. Curator Dr Stephen Gapps and model maker and museum volunteer Geoff Barnes describe the construction of a diorama portraying these ‘bonzer blokes from Kangaroo Beach’.

Geoff Barnes’s diorama depicts in minute detail the 1st RANBT’s work in building wharves in preparation for the Allied withdrawal from the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey in 1915. Photograph Andrew Frolows/ANMM

THE MUSEUM’S MAJOR EXHIBITION

War at Sea – The Navy in WWI opens in September, in time for the anniversary of the first Australian casualties of the Great War: the Australian Naval and Military Expedition forces at the Battle of Bita Paka in New Guinea on 11 September 1914 and the loss, just three days later, of the submarine AE1 with all hands. Another focus of the exhibition will be the contribution and experiences of the Royal Australian Navy Bridging Train (RANBT). This was the most highly decorated Royal Australian Navy unit during World War I, with 20 awards for bravery or good service at Gallipoli and in the Sinai.

But what was a naval bridging train?

Sailors on horseback

When war broke out in Europe in August 1914 the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) had not long been formed. It had a newly built and commissioned fleet that had only arrived in October 1913, and other vessels

under construction. The RAN was still in a period of transition from the Royal Navy, and many RAN vessels included substantial numbers of Royal Navy personnel who were ‘on loan’ to the RAN. In late 1914, there were Australian sailors in the reserves, but among these only a few immigrant ex-Royal Navy and some ex-Colonial Navy personnel were deemed suitable for active service with the RAN. Most reservists – about 8,000 officers and men – did not qualify to serve on board warships. Many found themselves doing odd jobs such as guarding wharves, practising minesweeping and myriad other minor duties.

Then someone hit on a good idea. Since the reservists were able to sail small training boats, and had some technical training, they should be able to operate pontoon bridging trains. These were wagon-loads of prefabricated bridges, made up of small boats topped with planking that were assembled on the battlefield, usually to span rivers. These were needed urgently by the

Allied armies in Europe, who were short of engineers to do the work.

The 1st RANBT unit was formed in Melbourne in February 1915, and 300 volunteer reservists found themselves with a new career. Many had some maritime and labouring background, but they came from all walks of life, and included an architect, a dentist and a pearl diver. They were a lively mix of youth and experience. But there was an operational problem. Pontoon bridges were carried into action on horse-drawn vehicles, so these sailors needed crash courses in horsemanship as well as engineering and pontoon bridging. They also had to swap their naval uniforms for cavalry khaki. While there were plenty of horses available for training in Melbourne, and the men learned to ride, advanced technical training was difficult in Australia due to lack of equipment and expertise. So the RANBT was loaded onto ships in late May 1915 with the assurance that they could learn more

effectively in training camps in England. They thought they were bound for the Western Front to build bridges across European rivers. But when they got to Egypt, they found themselves conveniently available for a very different campaign and a very different task – to build pontoons in support of amphibious landings in the Dardanelles in the great invasion of Turkey. The RANBT was sent to support a new landing at Suvla Bay. This attack was designed to flank the Turkish forces and support a breakout from the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) sector, eight kilometres to the south. But the Suvla Bay attacks also failed and turned into a stalemate. By mid-1915, with the Allied forces clinging to beachheads and not in control of any Turkish ports, the RANBT was tasked with building a port.

Lieutenant-Commander Leighton

Seymour Bracegirdle was ideally suited to command the RANBT. Bracegirdle was an inner-city Sydney lad who had served

as a midshipman with the New South Wales Naval Brigade during the Boxer rebellion in China in 1900, and had ridden with the South African Irregular Horse in the Boer War. He joined the brand-new RAN in August 1914, serving as a staff officer with the Australian Naval and Military Expedition Force that captured the German colonies in New Guinea and the nearby Pacific islands, before being appointed commander of the 1st Royal Australian Navy Bridging Train.

Bracegirdle chose his volunteers carefully. Many were fellow veterans of the New Guinea campaign. Bracegirdle was to show a great capacity to adapt the RANBT’s particular skills and personalities to the situation at hand.

Early on the morning of 7 August, the RANBT landed at Suvla Bay under accurate Turkish artillery fire. The train set about building a pontoon pier to enable

Crates, sacks, sandbags, water tanks, light rail track and bogies, cables, ropes and all manner of abandoned junk littered the landscape of Suvla Bay

01 The central figures are building wooden ‘cribs’– wharf supports which, during the evacuation, would be floated out into the bay to create wharf decking. The diorama’s cribs are balsa, scaled to fit the perspective. Photograph courtesy Geoff Barnes

desperately needed supplies to be brought ashore, and casualties to be evacuated. This was their first vital contribution amid the shambles of the ill-planned and poorly led campaign. The RANBT set up their camp in a little cove that became known as Kangaroo Beach, just around from the main harbour at West Beach. This was where they worked on an incredibly diverse variety of tasks.

They built wharves and piers. They unloaded the work-boats that used them. They repaired the wharves and piers when storms tore them apart, or when the Turks blew them up, or when over-excited or careless coxswains crashed their vessels into them. They were instrumental in designing pumping and piping systems for getting vital water supplies ashore from the ill-designed lighters. Ingenuity was the key. They repaired and stockpiled engineering equipment that might otherwise have been discarded. They cobbled together whatever was needed in their open-air workshops on the beach. They did all the assorted jobs that the Royal Navy and the British Army were ill equipped or reluctant to do.

With the inevitable withdrawal from the Dardanelles in late 1915, the Allied forces faced the difficulties of safely extricating more than 100,000 men before the Turkish forces realised what was happening and wiped them out. Painstaking efforts were taken to make the Turks think that the British were building up for another offensive rather than a withdrawal.

The RANBT began to build wharves as prefabricated units on the beach, in full sight of the Turkish forces up on the hills, in the hope that the Turks would think they were being built to land more troops. Once built, the wharves were shipped to locations out of sight of Turkish positions. Certainly, by late December the Turks had not realised that the Allies were planning to abandon the Dardanelles in secret.

Most of the RANBT had evacuated under the cover of night by 17 December, but a small team remained on duty until the British rearguard and senior officers had boarded the last of the lighters. The last Australian infantry left Anzac Cove at 0410

hours on 20 December 1915. Only then did the last of the RANBT leave, at 0430 hours.

So the RANBT were instrumental in building the piers for the evacuation – a withdrawal that proved to be the most successful part of the whole tragic campaign.

The scene that Geoff Barnes has re-created in his diorama is a view of the activities of the 1st RANBT while building the wharves in preparation for the Allied withdrawal.

Geoff wanted to make the diorama as historically accurate as possible, and to get the colour and atmosphere right. His work was based on extensive research of the RANBT, as well as books on uniform details, works of contemporary artists and personal accounts. He also gathered many photographs of what the landscape and terrain were like both then and now.

His most important resource was the portfolio of photographs taken in 1915 by Lieutenant-Commander Bracegirdle to document the work of his troops at Suvla

The design of the diorama was based on extensive research of the RANBT, books on uniform details, works of contemporary artists, personal accounts, and photographs of the landscape and terrain

Bay. These candid photographs were taken with an engineer’s eye for detail. They were not official military photos – censorship forbade photography except by sanctioned cameramen. Despite this, many young officers packed a Kodak folding camera in the voluminous pockets of their tunics.

The diorama is 1.5 metres wide by 1 metre deep, and took eight months to complete. It comprises an extensive landscape piled high with military materials, a harbour sheltering 19 vessels – all built from scratch – and about 160 individual figures. Some of these are metal, but most are from plastic ‘kit figures’ that have been converted to accurate representations of the RANBT uniforms. All of these elements range in scale from 1/35th to 1/500th.

Forced perspective is the key to this diorama. If viewed from the front, the figures and landscape diminish into the distance accordingly. This led to some interesting problems and no easy solution. Geoff often had to judge by eye as he went, and keep grafting the balsa-wood hulls of vessels until they looked right.

The key component here is the light rail line that leads from the foreground to the distant wharves. Geoff used three different gradings of plastic girder, diminishing the rails and their underlying sleepers to create the impression of distance.

Much of Geoff’s materials were bits and pieces collected over 50 years of modelmaking. He used some 54-millimetre Anzac character heads from Queensland sculptor Phil Walden, plus commercially available figures from Airfix, Tamiya, Mini Art, Master Box and Sveda, and railway modelling and ship model-making supplies. He found Scale Link’s range of World War I heads with their distinctive slouch hats and sun helmets – as well as a wide range of weapons, webbing and useful accessories like water cans and wheelbarrows – to be invaluable.

Geoff began by laying out the diorama in full size on a large sheet of cartridge paper. It would change over the months to come, but on completion, was more or less as he had conceived it. He did card mock-ups of the landscape features and cut-outs of the ships’ shapes.

01 Geoff Barnes with his almost-completed diorama, which will be a centrepiece of the museum’s forthcoming exhibition War at Sea – The Navy in WWI. Photograph courtesy Geoff Barnes

02 The beach at ANZAC by Frank Crozier (1919). Geoff Barnes used this image as a colour reference for his diorama. Frank Crozier was later appointed an official war artist. He was one of the few official artists who had experienced heavy fighting, at Pozières and also at Gallipoli. Crozier often depicted the soldier’s viewpoint and painted the human dimension of warfare. Australian War Memorial ART02161

03 West Beach, Suvla Bay, Gallipoli, in 1915, photographed by Lieutenant-Commander Leighton Seymour Bracegirdle RAN, commanding officer of the 1st Royal Australian Navy Bridging Train at Gallipoli. Australian War Memorial P11165.010.001

01 The ‘black beetle’ landing craft were scratchbuilt from filing card shaped around balsa wood hulls. The vessels had to be tapered to create the impression of diminishing perspective, and figures of different scales were placed on the decks to reinforce the illusion. Photograph Andrew Frolows/ANMM

02 Varying flesh tones were applied on faces and hands, reflecting differing skin tones and degrees of suntan or sunburn, as well as bruises and injuries. The RANBT sailors used to collect fish that had been stunned by Turkish shells bursting near the docks – a vignette reproduced in the diorama.

Photograph Andrew Frolows/ANMM

The diorama started with a light but sturdy framework of pine. The landscape was then built up with 3-millimetre medium-density fibre board, which can be easily sawn or cut with heavy-duty craft knives. The distinctive rock strata were layers of pine bark from a treasure trove of useful odds and ends belonging to Geoff’s long-time modelling mate Bob Metcalfe.

The groundwork is builders’ sand, coarser than beach sand, mixed with spackle-type wall filler, PVA glue, student paint and water. Geoff has a large variety of various grades of sand and gravel stored away in jars, and these were added depending on the required texture of particular groundwork.

The 300 volunteer reservists of the 1st RANBT unit came from all walks of life, and included an architect, a dentist and a pearl diver

Groundwork colours are artist acrylics applied with heavy-duty bristle brushes made for large-scale oil painters. Shadows, and shading, are clearly identifiable in the contemporary work of war artists. Along with a paynes grey and alizarin crimson mix, a lavender colour – not familiar in European shadows – is very distinctive and reflects the harsh Turkish sunlight.

Geoff’s constant companions during the project were air-drying clay, paper clips, PVA – of which he used five large bottles – Araldite, super-glue, plastic card and cartridge paper. The household vacuum cleaner and a pensioned-off hair dryer were also most useful.

The historical photographs show piles of supplies everywhere. Crates, sacks, sandbags, water tanks, light rail track and bogies, cables, ropes and all manner of abandoned junk littered the landscape of Suvla Bay. Geoff plundered his ‘bits boxes’ for anything that could pass as military rubbish.

A laborious task was to re-create the lettering on the ration boxes. Geoff made shapes in general proportion, and then pasted box fronts on them, with labels such as those for the much-loathed bully beef made in different sizes to fit the diorama’s forced perspective.

The photographs of West Beach all showed tantalising glimpses of landing craft, but none had sufficient detail. Geoff searched for references and found that the ships’ lifeboats and barges that were towed over from the Nile River in Egypt were insufficient to keep up the massive daily consumption of water, food, ammunition and supplies. With some foresight the Admiralty had commissioned 200 landing craft (dubbed ‘black beetles’) – long, motor-driven barges with spoon-shaped bows that could be easily run up on to beaches, and which had drop-down ramps to facilitate unloading.

Most of us know World War I in monotone, from black and white photographs and film footage. So Geoff sought out soldier–artists who had done on-the-spot paintings, or war artists who had researched the campaigns with an eye to detail.

Frank Crozier was an ANZAC at Gallipoli, and had been a promising artist before joining up. While at Gallipoli, he was approached – along with other artist–soldiers – by Charles Bean and asked to help illustrate Bean’s proposed The Anzac Book, a collection of poems, short stories and illustrations by the soldiers at Gallipoli.

Crozier’s large painting of Anzac Cove, showing men, material and landscape in glowing colour, was a prime resource for the diorama. So too were the works of British sailor Norman Wilkinson, who served in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve in the Dardanelles and was an artist of note (he also invented ‘dazzle camouflage’ for ships). Wilkinson’s luminous watercolours of Suvla Bay in 1915 provided further on-the-spot colour references.

After eight months of painstaking work, Geoff’s diorama was complete. It will now be installed in a display case and form a central interactive experience in the exhibition War at Sea – The Navy in WWI The exhibition will be on display at the museum from September this year until May 2015, after which it will travel to various regional museums around Australia.

A more detailed account of the creation of the diorama can be found in Military Modelling Vol 44 Nos 2 and 3.

The official war correspondent with the Australian Imperial Force, journalist and honorary captain C E W Bean, wrote of the RANBT at Suvla Bay: There they are in charge of the landings of a great part of the stores of a British army. They are quite cut off from their own force; they scarcely come into the category of the Australian force, and scarcely into that of the British; they are scarcely army and scarcely navy. Who is it that looks after their special interests, and which is the authority that has the power of recognising any good work that they may have done, I do not know. But if you want to see that good work, you only have to go to Kangaroo beach, Suvla Bay, and look about you. They have made a harbour.

In the 1920s a series of dioramas was constructed for the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. The idea for the dioramas came from discussions between C E W Bean and a group of war artists. Bean saw the dioramas not just as battlefield models, but also as works of art and educational displays. The dioramas – once regarded as dusty remnants of an old way of viewing the past – are now among the prized treasures of the Australian War Memorial.

The Australian Register of Historic Vessels went on the national beat in November last year, with a seminar in Western Australia that canvassed the state’s historic vessels, the trades they plied and the people involved with them. Conference organiser, senior curator Daina Fletcher, relates some of the tales that emerged.

W ESTERN AUSTRALIA’S MARITIME STORY is dominated in the popular imagination by two major themes: the 17th- and 18th-century Dutch navigators shipwrecked on inhospitable shores, and the triumph of Australia II in the 1983 America’s Cup. But the many other histories woven between these events and eras are just as compelling. They also offer different perspectives on the economy of this huge state beyond what can be mined from it or grazed upon it.

The Australian Register of Historic Vessels (ARHV) seminar held in Fremantle last November was titled Fishing, pearling, sailing or trading: stories of Western Australia’s seagoers and their craft. Its aim was to explore these industries and the economics and communities that shaped and sustained them.

A deliberate strategy was the pairing of theoreticians with active participants across a range of themes. Our audience listened to first-hand accounts alongside analytical historical presentations on such topics as fishing, pearling, Aboriginal coastal culture, and sailing. In each case, the theory and practical aspects of history were woven around craft on the ARHV so that each session encompassed both the public and the personal, the general and the specific, to add depth and context.

The seminar was introduced by Moya Smith, Head of Anthropology and Archaeology, and Brett Nannup, Indigenous Collections Registrar, both from the Western Australian Museum (WAM). They explored the coastal and riverine cultures of Western Australia’s Aboriginal people from their relative perspectives – Moya as an anthropologist who has worked with saltwater peoples from the Kimberley, and Brett as an artist and member of the Pinjarra community south of Perth, who has fished and hunted in his country for much of his life.

Moya showed an engaging range of images that emphasised continuing traditions, from rock art to more recent early European documentation. These included the barrawarra – a generic term for canoes, but commonly used to describe simple dugouts; namandi, bark canoes with additions; and galwa or biyal biyal, single or double fan-shaped rafts made of kapok mangrove, examples of which are in the collections of both WAM and ANMM.

While Moya covered coastal Kimberley water-based traditions of the north-east, Brett Nannup told us of his life by the water in the south-west, especially of fishing as a source of contentment and contemplation. Brett is a printmaker who also makes artefacts such as spears using traditional techniques. His lyrical exposition featured his prints and related his family stories of fishing, and favourite childhood fishing spots along the Canning and Murray rivers.

Aboriginal fishing along rivers, estuaries and the coast has been practised for millennia, and is small in scale. Other speakers at the seminar traced the involvement of saltwater peoples in the fishing and pearling industries as these industries grew, with seals, whales, bêche de mer, fish, crays, shell and pearls becoming valuable commodities for overseas export. Aboriginal people worked as highly skilled divers, fishers, boatbuilders and crewmembers.

The development of fishing as an industry was addressed by Professor Malcolm Tull of Murdoch University, who outlined its changing scale from small beginnings as a family activity in the early years of the Swan River colony from the mid-19th century, to its growth with the construction of the Great Southern Railway between Albany and Perth in 1889 and of the ice-works in Albany in the 1900s. The ice-works enabled the industrial packing of fish for transport to markets along the rail line.

After World War II, European immigrants brought their tastes and traditions to Western Australia, and saw the huge potential in the rock lobster and prawn fisheries

01 Hauling salmon at Hopetoun on the south coast of Western Australia, in the late 1940s. J S Battye Library. Reproduced with permission

02 Beth Fitzhardinge with crayfish, c 1964. Photograph courtesy Fitzhardinge family

The industry had its challenges – the infrastructure was limited, while costs remained high and fish populations and productivity low, as fish lost out to beef on Australian dinner plates. Industries on the land offered more opportunities for wealth than those from the sea, and the small and scattered population provided limited numbers of entrepreneurs willing to enter the fishing industry. It remained small.

Innovative 3D laser surveys conducted to millimetre accuracy are a brilliant resource for rebuilding a craft, documenting its current condition and imagining its future and past configurations

Things changed after World War II, when European immigrants brought their tastes and traditions to Western Australia, and saw the huge potential in the rock lobster and prawn fisheries. This, with the adoption of new technologies in the 1960s, transformed

the fisheries into a valuable export industry. The Kailis and Lombardo families became Western Australia’s first millionaire fishers, and high-value fisheries were established in the Exmouth Gulf and Antarctica.

Fish stocks were assaulted, yet Malcom Tull asserted that the introduction of management controls in the 1960s ensured that the industry remained sustainable, and in 2000 it was the first fishery in the world to be certified as ecologically sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council. Western Australia’s share of the nation’s fishery value has dipped in response to the rise of the aquaculture industry in South Australia and Tasmania, which employs 13 per cent of Australia’s fishing workforce.

The less commercialised side of the industry was no less significant, especially to regional Western Australia. This consisted of small-scale family fishers centred around Geraldton and working the Abrolhos Islands crayfishery. They fished seasonally for months each year, forging a tight-knit community that built schools and churches on the islands for their sail-in, sail-out lifestyle – an earlier incarnation of today’s fly-in, fly-out workers.

The next speaker, John Fitzhardinge, was one of these Abrolhos Islands fishers. He started his fishing career at the Geraldton Fisherman’s co-operative in 1961, and the

next year built his own 24-foot (7.5-metre) fishing boat with his fiancée Beth. This seakindly craft had an innovative, bondwood hard-chine planing hull, which was by then a staple of the competitive industry.

John and Beth entered the industry at the end of its ‘gold rush’ period. The following season the industry was closed at 826 boats, then further restrictions were imposed on the number of pots – three – that were allowed per foot (30 centimetres) of boat length. In addition, the fishing grounds were closed from 30 June to 15 November to protect the breeding females.

The lifestyle was basic. John and Beth started their married life in a corrugated iron shed with a sandy floor, which was buffeted by any south-easterly breeze. They collected their water in tanks or carted it from Geraldton in carrier boats that also brought their stores, bait, fuel, water, building materials and mail once a week.

Before the school was built in the late 1960s, families were together only in the holidays. At other times they kept in contact by a rudimentary radio service, which relayed weather reports, telegrams and the weekly highlight of the fishermen’s request program (with dedications), sponsored by a Geraldton commercial station.

Communications improved with reliable radio, airstrip construction and eventually

television. Similarly, medical services were initially do-it-yourself in an industry which, according to John, was pretty unhygienic in the early days, and there were no freezers and inadequate protective clothing. By the 1970s most fisherman had freezers on the jetties they had built, and a weekly nursing service was established.

Fitzhardinge’s community at North Island built a school and employed teachers, allowing families to stay all season. It also built a hall, held fancy-dress and sports days and operated a bar every night. The community gradually grew to 130 people, including 25 primary school students and two teachers.

The unique sail-in, sail-out lifestyle that the Fitzhardinge family knew is disappearing, and cray numbers are falling. Malcolm Tull notes that the fishery has been influenced by environmental factors such as weather cycles, wind patterns and water temperatures – for instance the strength and temperature of the Leeuwin Current – plus the growth of recreational fishing in general.

The catch is dropping and new management regimes have reduced the Abrolhos fishing fleet and changed its operation. Many fishermen cart their own crays; only two carrier boats now operate in the island group; only one social club remains; and the last school, on Big Pigeon Island, has closed.

While the fishing industry is commercially important to Australia and represents an adventurous, unique lifestyle, perhaps the most fascinating Western Australian fishery was pearling, which had its boom period long before fishing was commercialised.

In 1913 it was the highest export earner for the state, as Michael Gregg from the Western Australian Museum pointed out in his talk about the state’s pearling history, which peeled away the romance of the industry to focus on its diversity.

The crews were famously culturally varied, comprising Indigenous divers and crews in the early years, then Indonesians, Malays, Filipinos, Japanese and Chinese. In fact the pearling port of Broome was exempted from the White Australia policy of the early 20th century because of its reliance on foreign workers.

Diversity in place, land and seascape also characterised the industry, from the Shark Bay pearl fishery to the north-west shellfishing ports of King Sound, Darwin and the Arafura Sea, and Torres Strait and North Queensland in the Gulf of Carpentaria. These different places and environments spawned different boats: shallow-draught flat-bottomed luggers of the tidal Western Australian coastline and the deeper-keeled designs of Thursday Island and the Torres

01 When Dad used to take us fishing at the Bend, by Laurel Nannup. Image courtesy Brett Nannup

02 Dugout canoe with a Culwulla Jawi crew member paddling near Bigge Island, Western Australia. NW Scientific Expedition, 1917. Photographer William Jackson. Image courtesy Western Australian Museum

03 Bardi elders Esther and Sandy Paddy, with 60 trevalley caught in Lalanan fishtrap, near One Arm Point, Western Australia, 1983. Photographer Moya Smith. Image courtesy Western Australian Museum

Strait. The boats also operated differently. In Torres Strait they stayed at sea for longer, working in deeper water, where their more yacht-like designs made them more manoeuvrable. The Broome fleet, by contrast, worked in 10-metre tides and, during the cyclone season, had to dry out on secured moorings or be purposely run aground on river beds for safety. The ARHV features 14 luggers, including several Broome luggers such as the DMcD, built in 1957 by Streeter and Male, who also built the ANMM’s John Louis

Michael outlined technological changes which affected lugger design and their raison d’etre – to provide air to divers collecting shell on the sea floor. These ranged from hand-operated, then enginedriven, air pumps on board to the combination of the propelling engine and the compressing engine, which could both drive the ship and support the diver at the same time.

Tony Larard is a former diver and small-scale pearl fisher who worked in the industry in the 1980s and 90s. He offered his personal perspective on operating such a business and the life it entailed. He entered the industry after another technological leap – the hookah diving technique, in which divers drifted in lines two or four deep, supplied with surface air, towed on outriggers from the ship.

This method – the biggest change to pearl diving since the introduction of the airsupplied hard-hat suit – was introduced to Broome in the 1970s by South Australian abalone divers.

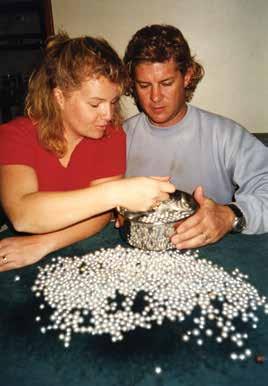

Tony’s first venture was for pearl shell in 1980, when he took his lugger Intombi, built in 1928, north to the Onslow area. Excited about the potential, he built another vessel, Willie, to enter the new pearl farming industry.

The Western Australian pearling industry had its boom period long before fishing was commercialised, and in 1913 it was the highest export earner for the state

Tony spoke in detail about the vessel and everyday life on a pearl farm – fishing, collecting shell, depositing it in the dump at sea, cleaning it and taking it to the farm to be spread on the bottom until the Japanese technician arrived to seed it. After implantation the shells were placed on the bottom and regularly turned for a six-week period, then put on surface longlines. There they remained until the pearl matured in two to three years. Before harvest, they were X-rayed; those carrying 12-millimetre pearls were opened, the pearls removed, then the shells reseeded if healthy. Shells with immature pearls would be returned to the lines for another year.

For nearly a decade, the entire family spent their lives between sea and land – living and fishing on the boat during the neap tide, and back at the farm base on West Moore Island on the spring tide. It was hard work and Tony was quick to accept an offer to sell the business. Today the cultured pearl industry is dominated by large multinational firms and the Paspaley family.

The ARHV at work

A session on the ARHV at Work gave voice to several owners whose vessels are listed on the ARHV, and highlighted the register’s

potential for enabling collaborations between owners and register staff in both sharing information and working together on methodologies and tools for historic vessel management.

Ron Lindsay outlined his passion of more than a decade: to save the 100-year-old, 40-foot (12-metre) motor launch Kiewa, which had been built by W and S Lawrence, his great-grandfather and great-uncle, for the commodore of the Royal Perth Yacht Club. Mike Beanland, owner of the double-ended Swan River ferry MV Perth, told of his often frustrated efforts to preserve and secure the 103-foot (31-metre) vessel. These ranged from spraying herbicide to unwrap weeds from the vessel to an innovative 3D laser survey conducted to millimetre accuracy. This is a brilliant resource for rebuilding a craft, documenting its current condition and imagining its future and past configuration. A 3D survey can be smoothed out, played with, changed to something different – it is a fantastic way to record historical artefacts, including buildings, and to interpret them.

ARHV council member Dr Ian MacLeod presented a beautiful exposition about conservation principles, while ARHV curator David Payne outlined Western Australian craft on the ARHV, which now total 36.

The final event of the day was the Vaughan Evans memorial lecture, jointly hosted with the Australian Association for Maritime History. Sailor and Western Australian businessman John Longley am c it wa delivered an engrossing behind-thescenes history of the America’s Cup, from Australia’s II’s historic win 30 years ago to the current contenders, and throwing further light on that landmark vessel and the people bound up in its significance.

This seminar was planned at an important time for the Australian Register of Historic Vessels (ARHV). Now in its eighth year, the register’s website arhv.gov.au is soon to have a much-needed facelift and redesign. Today the ARHV includes entries on 548 boats of all types: recreational, commercial, naval and Indigenous vessels, from all around Australia and overseas. There are also 102 reference entries, on builders, designers, types, classes, events and sites, plus more than 3,000 images, 130 plans and various multimedia entries (see Signals 105).

01 Tony Larard on the lugger Intombi in 1980 with pearl shell meat drying from the rigging.

02 Ross and Dianne Larard in 1997 with a harvest of round pearls.

03 Eve Adams and a deckhand cleaning pearl shell in 1996.

All photographs courtesy Eve and Tony Larard

04 Dugout canoe made by Robert Cunningham, Iwaidja, before 1970. Collected at Cobourg Peninsula, Northern Territory. Photographer Moya Smith. Western Australian Museum A23786

The ARHV was initially conceived as a cultural mapping program to chart Australia’s historic craft, to find out where they are and what they have meant to communities and history. Today the rich stories of the boats on the register and the opportunities offered by analysis of the industries or practices they represent, in seminars such as this, allow us to ask important questions about the comparative significance of those craft nationally. For example, how does the development of the fishing industry in Western Australia relate to that in South Australia, and how do surviving vessels reveal this? Is one more important than the other? These questions and many more will inform the next stage of the ARHV’s development, along with considerations of rarity, representativeness, original material, preservation, interpretive potential and possibly project sustainability.

The seminar was a great success, and we hope that this will be the first of many programs developed in association with museums and organisations around the country as the ARHV goes well and truly national.

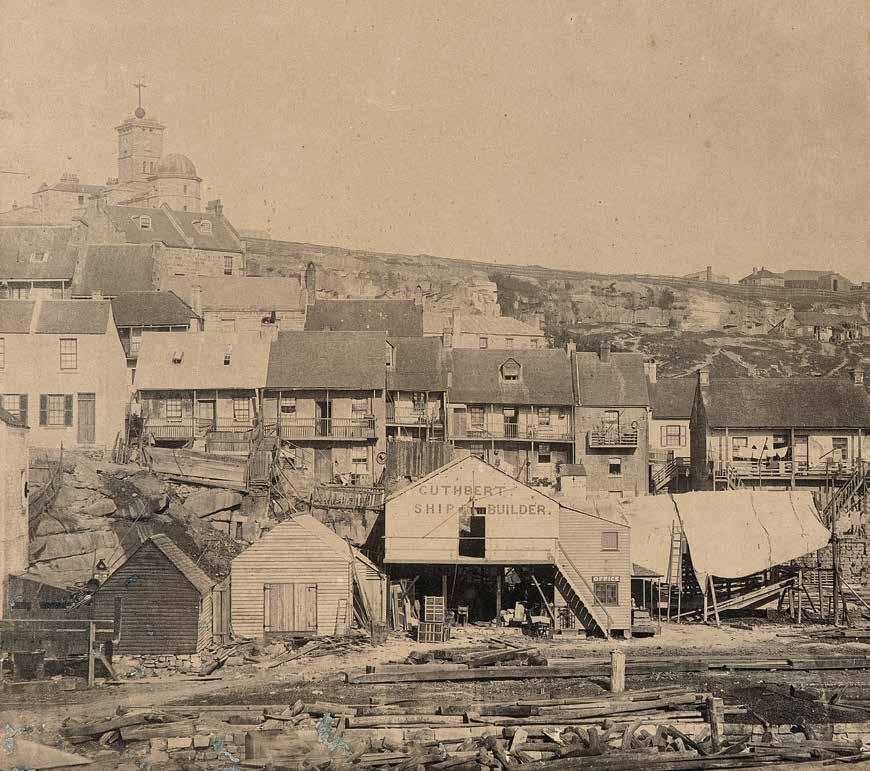

European settlers in New South Wales soon found the local timbers to be excellent for shipbuilding, and their qualities were quickly recognised in Britain also, resulting in a thriving colonial shipbuilding trade. Architectural historian and researcher Dr Roger Hobbs traces some of the earliest records of this industry, and examines the timbers that were favoured.

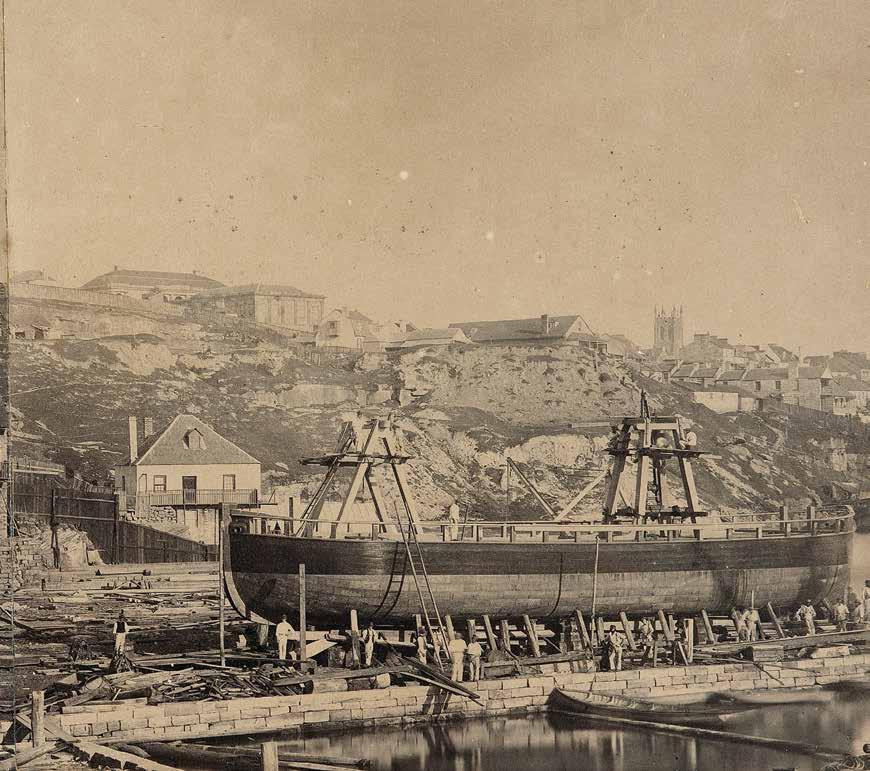

John Cuthbert’s shipbuilding yard on the western shore of Miller’s Point, Sydney, in the early 1860s. ANMM Collection

John Cuthbert’s shipbuilding yard on the western shore of Miller’s Point, Sydney, in the early 1860s. ANMM Collection

IN 1802, JOHN HUNTER, second governor of New South Wales, wrote to British Under-Secretary John King:

Dear Sir …

The crooked limbs of most of the gumtrees, when sound, are very fit for ship timbers or ribs, and are uncommonly durable … Masts have been made of it … When this wood has been used for planking a ship, it has been found of so hard a nature that a scraper would hardly touch it (Cornhill, No 40, 22 March 1802)

This complimentary assessment of Australian native timbers was made just 14 years after the colony of New South Wales was established. The selection and use of any timber was based on its strength, durability, straightness of grain and resistance to marine borers, a process which had begun with the arrival of the First Fleet in New South Wales in 1788. Shipwrights and boatbuilders, appointed by successive governors in Sydney, had, by 1803, identified mahogany, stringybark, honeysuckle, ironbark, box and red, black (blackbutt) and blue gums as suitable for shipbuilding. However, the first detailed description of the timbers used in colonial shipbuilding is that of the Australian, a whaling vessel of 270 tons burden, launched on the Hawkesbury River near Pitt Town in March 1829, written by its builder Captain Grono:

The outer planking of the Australian is 2 inches [5 centimetres] thick, each plank being from 10 to 14 inches [25 to 35 centimetres] wide. She is chunamered , or covered with a coating of oil and lime,

after the manner of the Chinese Junks, and is sheathed over all: the masts and yards are of black-butted gum, and have been already procured, though not shipped. The whole of the materials from stem to stern, and from keel to truck, consist of blue gum, black-butted gum, iron bark or apple tree ... The knees and timbers are of iron bark, and the top timbers are of apple tree, most of which were procured from Pitt Town Common (The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 2 April 1829, p 2)

The value of Australian timbers was recognised by marine insurers Lloyd’s of London by 1851

During the period 1843–1856 alone, 351 new vessels built in the colony were registered in Sydney. Almost all were for the expanding coastal and intercolonial trade out of Sydney, with the majority built in the northern coastal districts. Almost without exception, these vessels were built for and by the merchant sector, which reported the materials used in construction in the newspapers of the day, as evidence of the quality and safety of their new acquisitions. Colonial vessels such as these have left little but archaeological evidence of the timbers used in their construction. However, a case of timber samples,

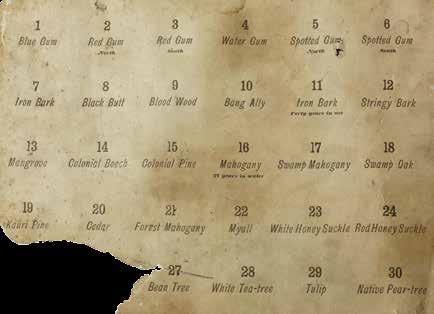

used in ship and boat building in New South Wales in the 1860s, has survived in the collection of Museum Victoria, Melbourne. Assembled by respected Sydney shipbuilder John Cuthbert for the Intercolonial Exhibition in Melbourne in 1866, the representative samples were listed as:

1 Blue Gum; 2 Red Gum North; 3 Red Gum South; 4 Water Gum; 5 Spotted Gum North; 6 Spotted Gum South; 7 Iron Bark; 8 Black Butt; 9 Blood Wood; 10 Bang Ally; 11 Iron Bark (40 years in use); 12 Stringy Bark; 13 Mangrove; 14 Colonial Beech; 15 Colonial Pine; 16 Mahogany (27 years in water); 17 Swamp Mahogany; 18 Swamp Oak; 19 Kauri Pine; 20 Cedar; 21 Forest Mahogany; 22 Myall; 23 White Honeysuckle; 24 Red Honeysuckle; [25–26 labels missing, although one may be Mountain Oak]; 27 Bean Tree; 28 White Tea-tree; 29 Tulip; 30 Native Pear Tree.

John Cuthbert (1813–1874) was born in Cork, Ireland, and apprenticed to a shipwright. He arrived in Sydney in 1844, and by 1853 had taken over Corcoran’s shipyard, later moving his business to Millers Point. Cuthbert’s business carried a stock of seasoned timber, which in 1868 included, for framing and planking, ‘the ironbark, blackbutt, and the flooded, blue, red, and spotted gums; and, for fittings, the tea tree, ironbark, blackbutt and bangalley’. The stock of timbers fits well with the timbers described in the Empire in 1857:

The durability of many kinds of Australian timber, and its superior qualities for naval purposes, have … only lately been acknowledged at Lloyd’s. A vessel framed out

Built Date

Richmond River, Coraki 1876 Beagle

Three-masted schooner, screw-steamer 170 tons, LOA 150 feet (45.7 metres): keel ironbark, frames hardwood, beams box. Top timbers cedar, planking inside and out spotted gum and blackbutt

Williams River, Hunter River catchment 1832 Unnamed Schooner, 62 tons, LOA 48 feet (14.6 metres): floor timbers ironbark, first futtocks flooded gum, top timbers flooded gum and cedar, outside planking flooded gum, decks pine (unconfirmed) to an American design

Brisbane Water 1865 Cleone Ketch, LOA 70 feet (21.3 metres): keel, keelsons, timbers of ironbark, beams of blackbutt, planking of blackbutt, decking colonial beech

Sydney 1872 Eglantine

Armed schooner, LOA 77 feet (23.5 metres): keel of ironbark, framing of blackbutt and blue gum with kauri pine for the planking (one of four in a government contract)

Jervis Bay 1867 Duke of Edinburgh Barque 358 tons: framing ironbark, planking blue gum, keelsons ironbark, decks kauri pine

Clyde River 1866 Vision Brig, LOA 105 feet (32 metres): framing ironbark and red gum, planking and ceiling spotted gum, decks kauri pine

01 A box of Australian timber samples exhibited by John Cuthbert at the 1866 Intercolonial Exhibition in Melbourne. An article in The Argus on 25 October 1866 stated, ‘an enormous fund of information is to be found in a case shown by Mr J Cuthbert, ship-builder of Sydney, which contains thirty miniature beams, which can be taken out and handled’.

02 Labels from the box of Cuthbert’s samples, identifying the timbers within.

03 An advertisement for Cuthbert’s shipyard attached to the box of timber samples. All images reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria

In newspapers, merchants reported on the materials used in construction of their new vessels as evidence of their quality and safety

of ironbark, box, red honeysuckle or tee tree, and planked and lined with flooded gum, blue gum or blackbutt; and treenailed with iron-bark, will receive the very highest class given, provided Lloyd’s rules with regard to timbering, planking, shifting and fastening be otherwise attended to.

A strong merchant-trade with Britain, coupled with shipments of Australian timbers to shipyards in both Britain and India, resulted by 1851 in recognition of the value of Australian timbers by marine insurers Lloyd’s of London. The Australian Lloyd’s Association, formed in 1864 in Melbourne, classified the timbers to be used in its Rules and Regulations, which encapsulated existing colonial shipbuilding standards. This source, coupled with newspaper reports of vessels, such as those tabled on page 24, has enabled a core group of indigenous timbers to be identified and the species and uses of Cuthbert’s samples to be explored.

The core indigenous timbers used in New South Wales in the 19th century were flooded gum Eucalyptus [E.] tereticornis, blue gum E. saligna, blackbutt E. pilularis and ironbark E. paniculata, all of which were represented in Cuthbert’s samples. Regional construction standards were influenced by the timbers available, however, including many in Cuthbert’s samples, although an ironbark keel was almost standard.

Ironbark was mainly used for the timbers, floors and keels of vessels. The common or she-ironbark E. paniculata, now known as grey ironbark, was also used for planking; timber from this tree was ‘prized by the shipwright’, and was also used for knees. The large-leaved ironbark E. siderophloia, now known as the northern grey ironbark,

indigenous

was not correctly described until 1867, but is thought to have also been used for large, sectional timbers such as keels. Cuthbert’s ironbark samples have still to be identified.

The flooded gum or red gum E. tereticornis, used for heavy deck-framing, beams and knees and planking, is now known as the forest red gum. The closely related and allied red gum or river red gum E. rostrata, now E. camaldulensis, found only in the catchment of the Hunter and Goulburn rivers in the coastal districts, was identified as a new species in 1847. In 1868, Cuthbert’s stock included both flooded gum and a ‘red gum’, suggesting that his northern red gum sample could be the red gum E. rostrata – although both red gum samples, based on current standards, may be the flooded gum E. tereticornis

The flooded gum E. tereticornis should not be confused with the flooded gum E. grandis, identified as a separate but related species to the blue gum E. saligna in 1862. The blue gum, used for framing and planking, was also known by the common names grey or flooded gum. The flooded or rose gum E. grandis, which grows in and north of the Hunter River district, was used for masts and planking. Similarly, blackbutt E. pilularis ‘grew to a great height’ and was ‘well adapted for masts’, for which it was in use by the 1820s as well as for planking. Used for many purposes, blackbutt was seen in 1885 as ‘ranking in durability next to the far-famed ironbark’.

Stringybark E. obliqua, also known as messmate, had an indifferent reputation for shipbuilding, being used for framing in protected areas and not considered suitable for outside planking. Spotted gum was used increasingly in the 1860s for

Mid-19th-century common name Other/Latin names, and year first described Modern names

Flooded gum Red gum, blue gum or grey gum Eucalyptus [E.] tereticornis 1795

Forest red gum E. tereticornis

Blue gum Grey gum or flooded gum E. saligna 1797 Sydney blue gum E. saligna

Blackbutt Black-butted gum E. pilularis 1797; ironbark E. persicifolia 1822

Ironbark Common, she or red ironbark E. paniculata 1797

Blackbutt E. pilularis

Grey ironbark E. paniculata

01 Timber getters near Yarrowitch, northern New South Wales. Courtesy State Library of New South Wales

02 Tallow-wood log on a jinker drawn by A A Teague’s bullock team at Warrell Creek, New South Wales, c1905. Reproduced courtesy Macleay River Historical Society 01

Colonial vessels have left little but archaeological evidence of the timbers used in their construction

timbers such as keels and keelsons and for planking in ships’ bottoms, due to its capacity to bend; by the end of the 19th century it was considered as good as English oak. The southern sample in Cuthbert’s selection is E. maculata, now Corymbia [C.] maculata, found throughout the central and southern coastal districts; the northern sample is the large-leafed spotted gum C. henryi, found in northern New South Wales. The related bloodwood, probably C. gummifera, was used infrequently for framing and planking.

Mahogany E. resinifera, a hard, heavy, durable timber, was used for knees and framing in vessels. Similarly, swamp mahogany E. robusta was also employed for knees. Not as durable as other timbers, it was increasingly used for heavy framing in coastal vessels. Bang ally or bangalay E. botryoides, known as bastard mahogany, was used for the ‘knees and crooked timbers of vessels’ and was considered an ‘excellent timber for the shipbuilder’.

The forest mahogany or tallowwood E. microcorys, ‘eagerly bought by the shipwright’ in the 1870s, was used increasingly for framing, planking and fitting-out by the end of the 19th century.

The white tea tree Melaleuca leucadendron (now M. leucandendra) was available throughout the coastal districts. Sought after for its hard, close-grained wood, white tea tree was used for framing, knees and fittings in all types of coastal vessel. Re-classification has limited the distribution of M. leucandendra to Queensland and other northern regions; M. quinquenervia is the revised species name in New South Wales.

Although colonial hardwoods were used for masts and spars, local and imported pine timbers were also used, as well as for decking. Kauri pine, imported from New Zealand, was commonly used for decking, although also for planking, masts and spars. The colonial pine or hoop pine Araucaria

01 A view of Sydney Cove, New South Wales, 1804. Drawn by E Dayes from a picture painted at the colony. Hand-coloured aquatint engraved by Francis Jukes, depicting a timber vessel on the stocks. National Library of Australia.

02 Spitfire, Australia’s first warship, was designed and built by John Cuthbert in 1855 from ironbark and blackbutt. A vessel believed to be Spitfire is shown here in Cooktown around 1859 or later, after leaving service with the NSW naval forces. Reproduced courtesy RAN

cunninghamii, a soft timber, was also used for spars and decking, as were the larger cypress pines. Colonial beech Gmelina leichhardtii was valued where a hard-wearing deck was required. In 1861, in the northern coastal districts, this timber was noted as also used for planking. In vessels of all sizes, cedar Cedrela toona (now Toona ciliata) was used for finishing and fitting-out, and for features such as the fiddle-head (a decorative scroll on the bow).

The mangrove Avicennia officinalis (now A. marina), a heavy, durable wood, was used for pins and sheaves in blocks, marlin spikes and for knees in boats.

Smaller boats and yachts were also built using some of the timbers utilised in larger vessels; Cuthbert built and raced his own yacht, the Enchantress, in the 1850s. Cuthbert’s samples incorporated decorative timbers, such as tulipwood and native pear tree, and framing timbers for boats and small vessels, such as myall and honeysuckle – inclusions that reflected both changing

social values, and that large vessels were also better finished.

Due to the resin content and density of many colonial timbers they appear to have had more resistance to borers than traditional timbers used in Britain, northern Europe and North America (such as native oak and pine) and also had advantages in supply and durability over teak from Burma (used in India). Colonial vessels often lasted more than 20 years without major refitting of the hull.

In 1909 it was reported that ‘it is now the age of iron, timber becomes scarcer and more scarce … you may now construct the hulls of two iron boats for as much as you might pay for one of wood’ (Sunday Times, Sydney, 12 December 1909, p 15). Although the construction of coastal and intercolonial timber vessels had ceased by the early 1900s, many of the timbers used in the 19th century remain in use today for boatbuilding.

Ship and boat builders in New South Wales could be said to have been spoiled for choice when compared to their counterparts in Britain. In addition to Cuthbert’s samples, turpentine Syncarpia glomulifera, with its great resistance to borers and the marine environment, and grey box E. moluccana were also used. The samples in Cuthbert’s collection require further research, in particular the water gum and the two unknown samples (25 and 26). These and other timbers used in ship, boat and yacht building are discussed in a scoping study, Indigenous Timbers in Ship and Boat Building in New South Wales 1820s–1870s, and in a type profile, Shipbuilding Timbers in New South Wales 1820s–1880s, on which this article is based. Copies are available from the author: rogerhobbs@grapevine.net.au

Born in 1945 in the north of England, Dr Roger Hobbs b a rch, b a pp s cience, pd trained as an architect before moving to Australia in 1974. He returned to architecture in the 1980s after working in geophysical exploration and museum and conservation-related work. For the last 25 years he has worked as an architectural historian and heritage consultant in the private and government sectors at local, state and national levels.

The White Australia policy of the early 20th century was one of the nation’s most infamous pieces of legislation. But change began after World War II, when mass migration was encouraged and immigration rules were relaxed. Curator Kim Tao relates stories from three groups of post-war migrants, which feature in new showcases in the museum’s Passengers exhibition.

If Australians have learned one lesson from the Pacific War now moving to a successful conclusion, it is surely that we cannot continue to hold our island continent for ourselves and our descendants unless we greatly increase our numbers. (Arthur Calwell, Minister for Immigration, 1945)

WORLD WAR II was without doubt a defining event of the 20th century. It also profoundly affected Australia’s immigration policy, highlighting the necessity of population growth for the nation’s defence, security and economic development.

In July 1945 Prime Minister Ben Chifley established the Federal Department of Immigration and appointed the first Minister for Immigration, Arthur Calwell, who introduced a more coordinated approach to building Australia’s population through mass migration. In the lead-up to the 70th anniversary of planned post-war immigration, three new showcases in the museum’s Passengers exhibition recall pivotal moments in the first decade after the war, which would begin transforming this country from a ‘white Australia’ into a multicultural nation.

The Australian government launched its immigration program with the catchcry ‘populate or perish’, negotiating agreements to accept more than two million migrants and displaced people from war-torn Europe. Departure from Genoa explores the stories of three European women, including renowned radio broadcaster Lena Gustin (1914–2003), who migrated to Australia through the Italian port of Genoa after World War II.

Lena, an Italian schoolteacher, married journalist Dino Gustin in 1940 and they had three children. With wartime deprivation costing the life of their elder son, the Gustin

family decided to migrate to Australia, arriving in Sydney on Aurelia in May 1956. Lena would become the highly regarded voice of the Italian community in Sydney, but she was also one of the city’s first baristas. Her daughter Rosalba remembers how Lena’s longing for a good coffee led to her first job in Australia:

My mother saw a brand new espresso machine [in a coffee shop in the suburb of Bankstown]. She walked in, and as she did not speak one word of English, gestured that she would like an espresso. The owner of the shop had absolutely no idea how to operate the machine. And so Mum showed him. And not only did she get her good espresso, she was hired on the spot to make proper espresso coffee for his customers – and wash the dishes.

Lena also taught Italian twice a week at Ashfield Evening College and worked as a columnist for the Italian Catholic newspaper La Fiamma (The Flame). In 1957 she helped to establish foreignlanguage broadcasting on Australian commercial radio by presenting Ora Italiana (Italian Hour) on Sydney Catholic station 2SM. This was followed in 1959 by a daily program on 2CH. Lena’s popular programs, produced by Dino, were one of the few media outlets through which Italian news was regularly reported, alleviating the isolation experienced by many new immigrants before the introduction of ethnic community radio and SBS (the Special Broadcasting Service, which provides multilingual and multicultural radio and television broadcasts) in the 1970s.

Departure from Genoa includes a number of items relating to Lena’s broadcasting career, such as a world clock that she relied on to give her listeners the local and Italian times, and a tape recorder that Dino

Lena Gustin became the highly regarded voice of the Italian community in Sydney, and was also one of Sydney’s first baristas

01 Lena Gustin (centre, in white top) and Dino (in striped top) with their children Rosalba and Robert (seated on camel) in Port Said, Egypt, 1956. Reproduced courtesy Mamma Lena and Dino Gustin Foundation

02 Lena Gustin interviewing the Italian singer Peppino di Capri in Sydney, 1968. Reproduced courtesy Mamma Lena and Dino Gustin Foundation

03 Portable ‘on air’ sign commissioned by Dino Gustin, 1960s. ANMM Collection Gift from Mamma Lena and Dino Gustin Foundation

01

02 Cigarette tin containing Tony Ang’s Australian and US Army badges, 1940s. Lent by Ang family

used to record the Italian news directly from RAI Italia radio in Rome. He would start his day at 4 am to listen to the news and then laboriously transcribe it for Lena to read on air the same evening. Also on display is a portable ‘on air’ sign that Dino commissioned for use during Lena’s promotional photo shoots, as a visual reminder of her connection to radio.

Lena’s pioneering radio work, combined with her support of Italian welfare organisations, earned her the affectionate nickname ‘Mamma Lena’ – Mother of the Italians. July 2014 marks the centenary of her birth and a range of commemorative events has been planned by the Mamma Lena and Dino Gustin Foundation to acknowledge her tireless social and charitable work during a very significant phase in Australia’s post-war immigration history.

Chinese seamen

At the same time that the Australian government was promoting mass migration from Britain and Europe, it was engaged in a bitter struggle to deport several hundred Asian evacuees and seamen who had assisted the Allied effort during World War II. The Chinese seamen showcase examines the little-known story of the

2,000 Chinese seafarers who were stranded in Australia following the outbreak of war in the Pacific. They were given temporary refugee status under a special exemption to the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 (colloquially referred to as the White Australia policy), which aimed to prevent the entry of non-European immigrants by making them take a dictation test; those who did not pass – which was most of them – were denied entry.

During the war Chinese seamen worked as crew on coastal ships that carried supplies to the war zone and were also deployed on large construction projects around Australia. In 1942, 1,000 men were sent to work on the construction of Warragamba Dam west of Sydney. Another 1,000 went to Bulimba, Brisbane, in 1943 to build landing barges for the US Army invasion of the Philippines.

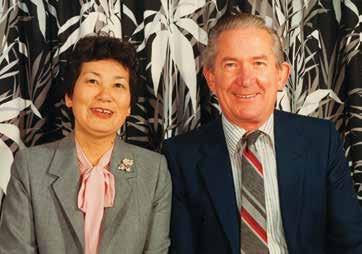

Tony Ang (1914–1964) landed at Perth in 1942 after his ship was torpedoed and, like many stranded seafarers, he enlisted in the Australian Military Forces (AMF), serving with the 7th Australian Employment Company (Chinese). After an honourable discharge from the AMF, Tony was among the seamen transferred to Bulimba.

While stationed in Bulimba, Tony met Marjorie Pettit, who lived near the army barracks on Apollo Road. The couple married in 1944. When the war ended, some 300 seamen, including Tony, sought to remain in Australia but Labor minister Calwell was determined to repatriate them. A legal battle erupted between this ‘recalcitrant minority’ and the government that challenged the basic tenets of the White Australia policy, and established that those who had been in the country for more than five years could no longer be subjected to dictation tests or declared prohibited immigrants. Calwell responded by introducing the Wartime Refugees Removal Act 1949 to deport them.

By this time Tony had lived in Australia for seven years and had three young sons. He left Australia in June 1949 and Marjorie and the children chose to go with him. The family’s departure for Hong Kong

on Changte was captured in all the newspapers, including The News, which featured a heartbreaking photograph under the headline ‘Another family deported’.

With Tony unable to find work, the family was forced to live in a crowded slum area in Kowloon and endure conditions that Marjorie described as ‘filthy and awful’. After five difficult weeks, with her sons ill, Marjorie had no choice but to return to Australia without Tony. Ahead of her arrival in August she wrote:

I will never forgive [the officials] for ruining the dearest and most precious thing in my life and Tony’s – our family. I will never forgive them every hour that our sons have lived in this filth and squalor, and every tear that we have shed.

In October Marjorie and her children moved to Hong Kong for a second time after Tony secured a job managing the canteen at Chatham English School on Victoria Peak. From Hong Kong Marjorie continued her appeals to the Department of Immigration about Tony’s case, which took a fortuitous turn when the Labor Government was defeated in the December 1949 federal election. The incoming Liberal Immigration Minister, Harold Holt, reversed Calwell’s deportation orders and granted residency to the seamen as a wartime legacy.